Submitted:

27 February 2025

Posted:

28 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

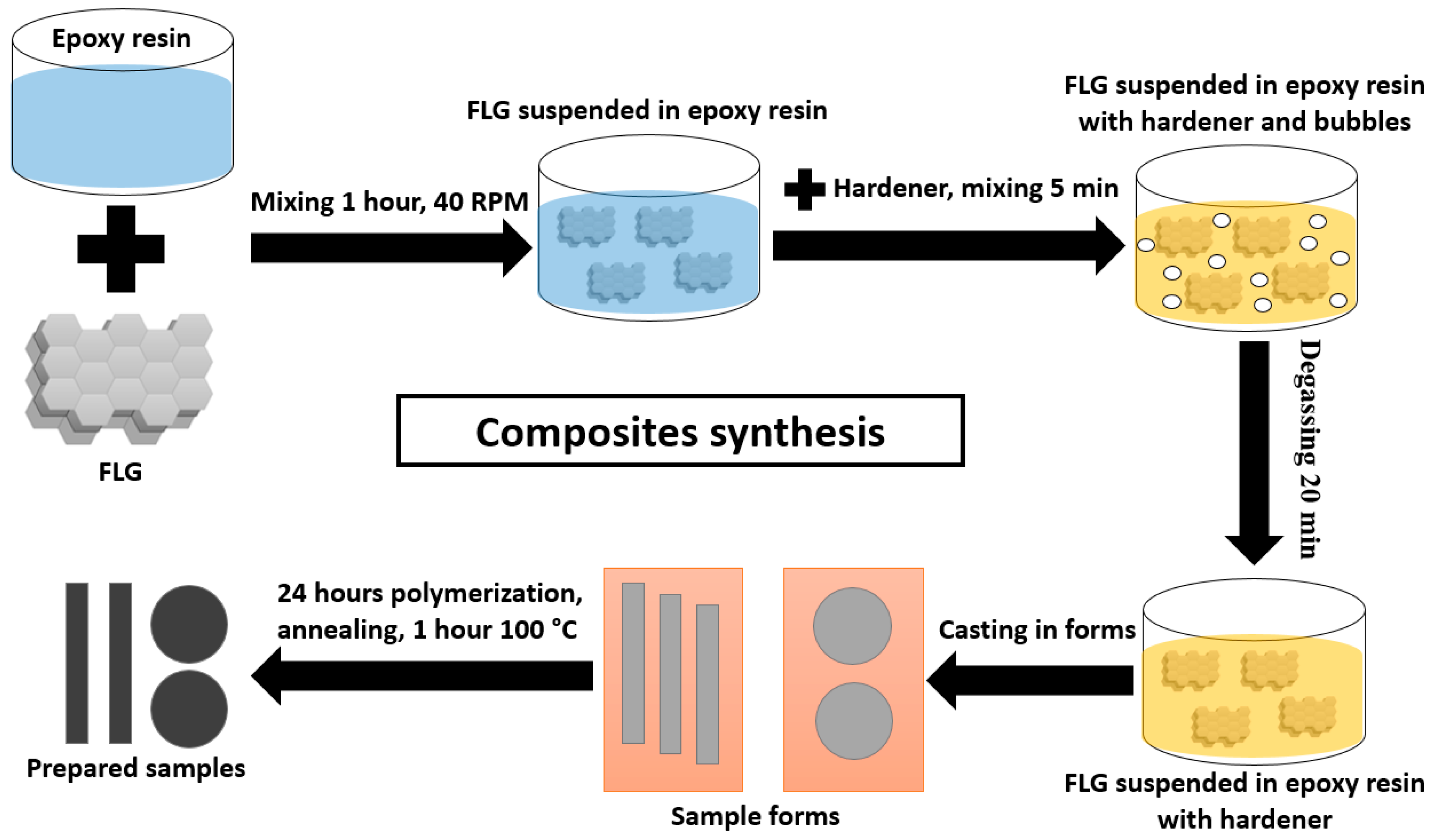

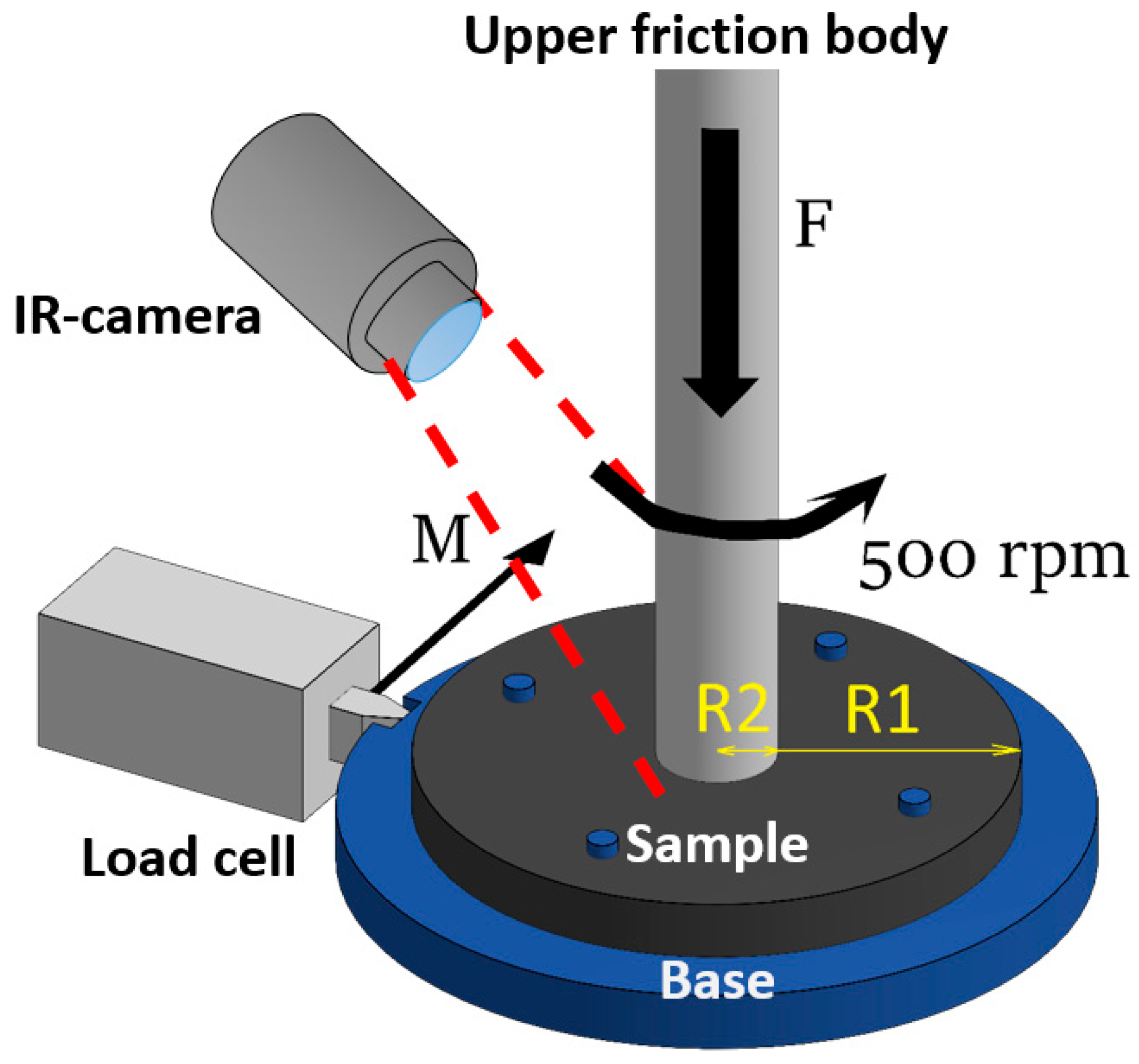

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

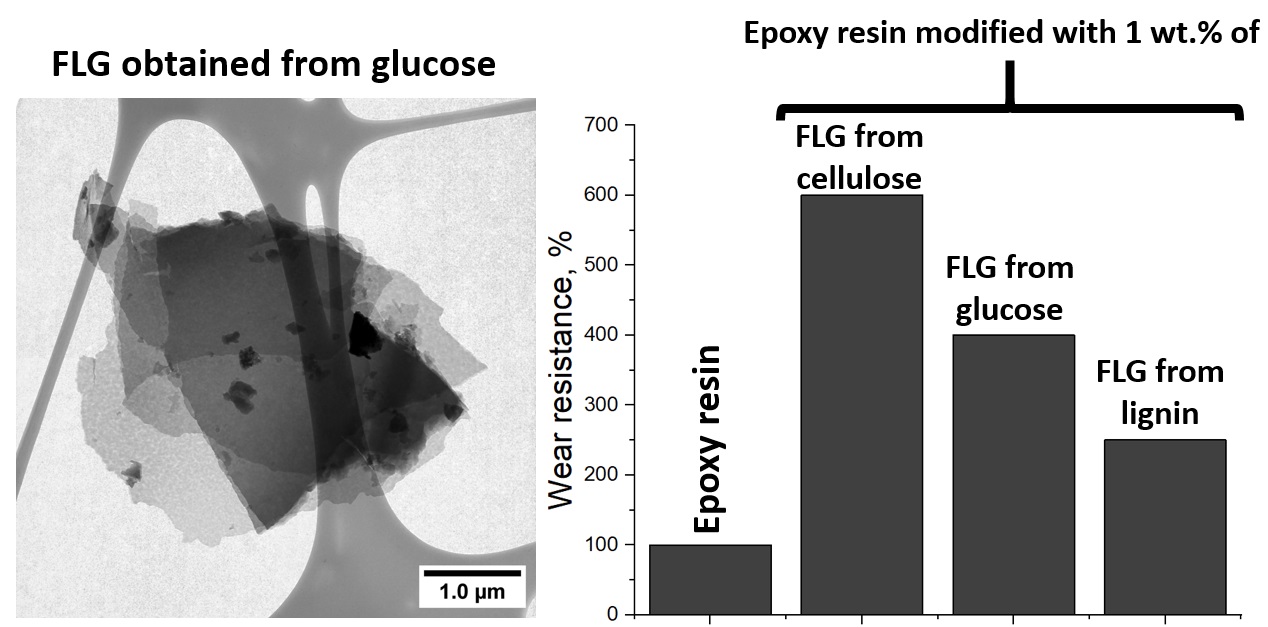

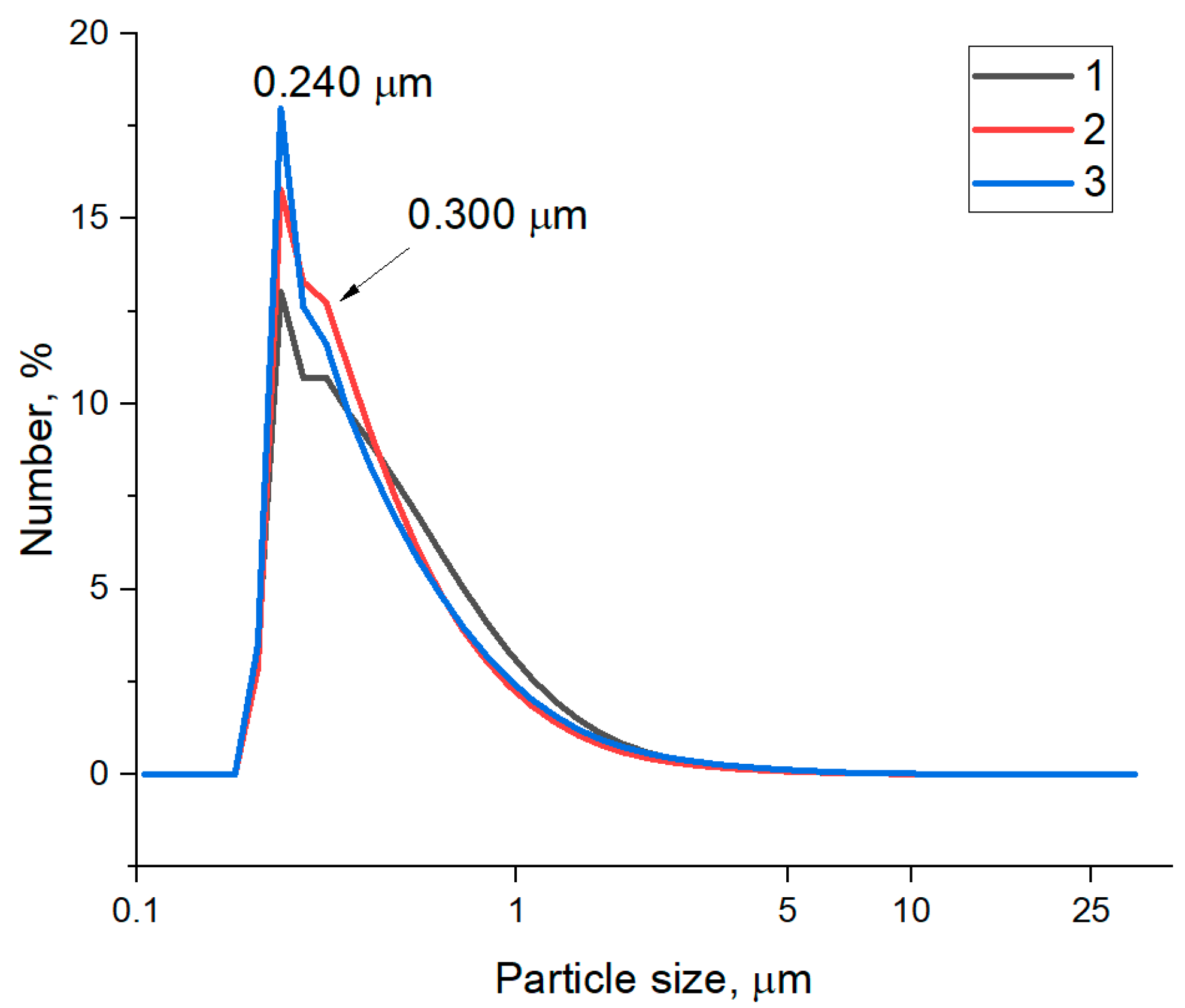

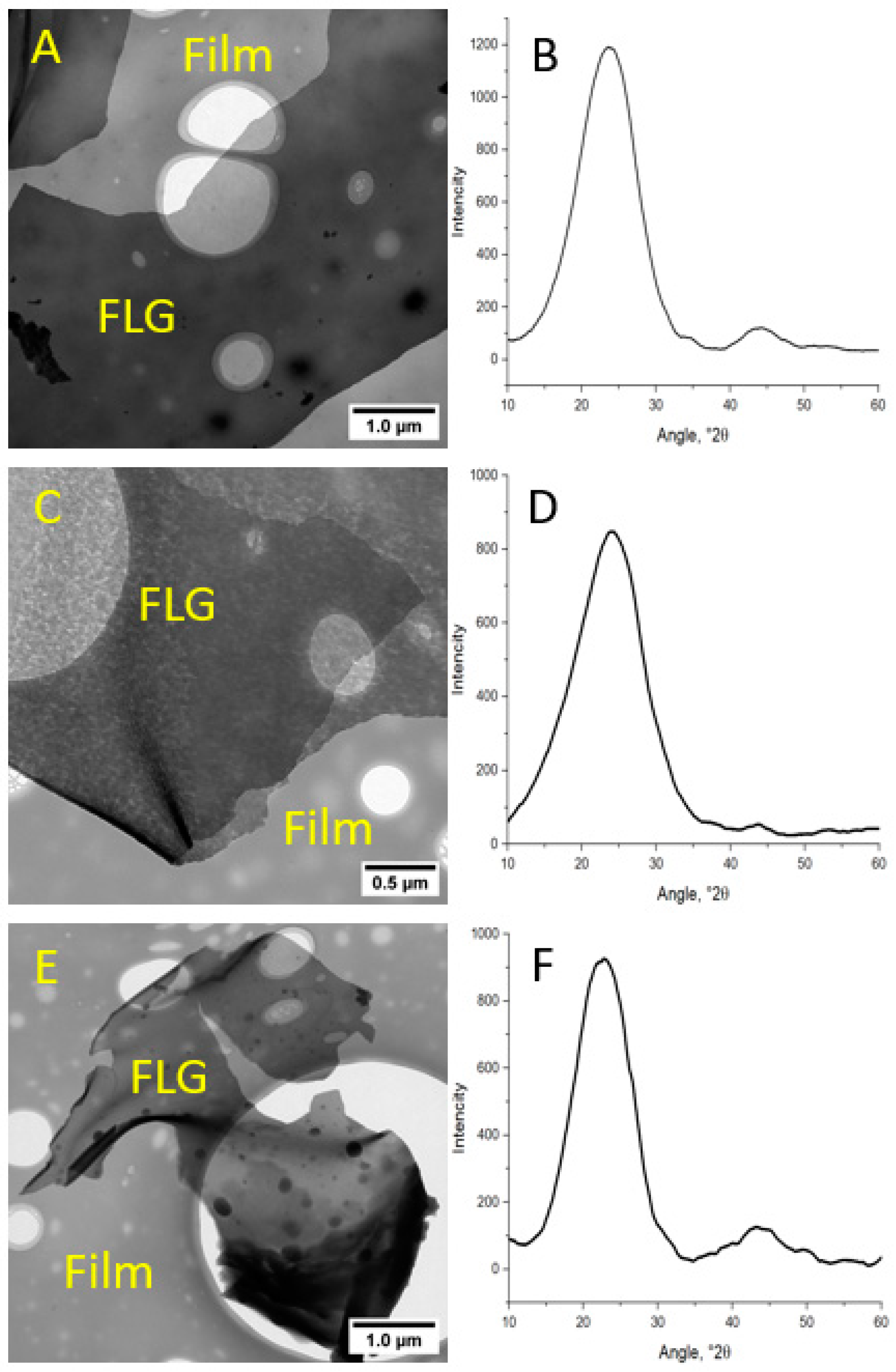

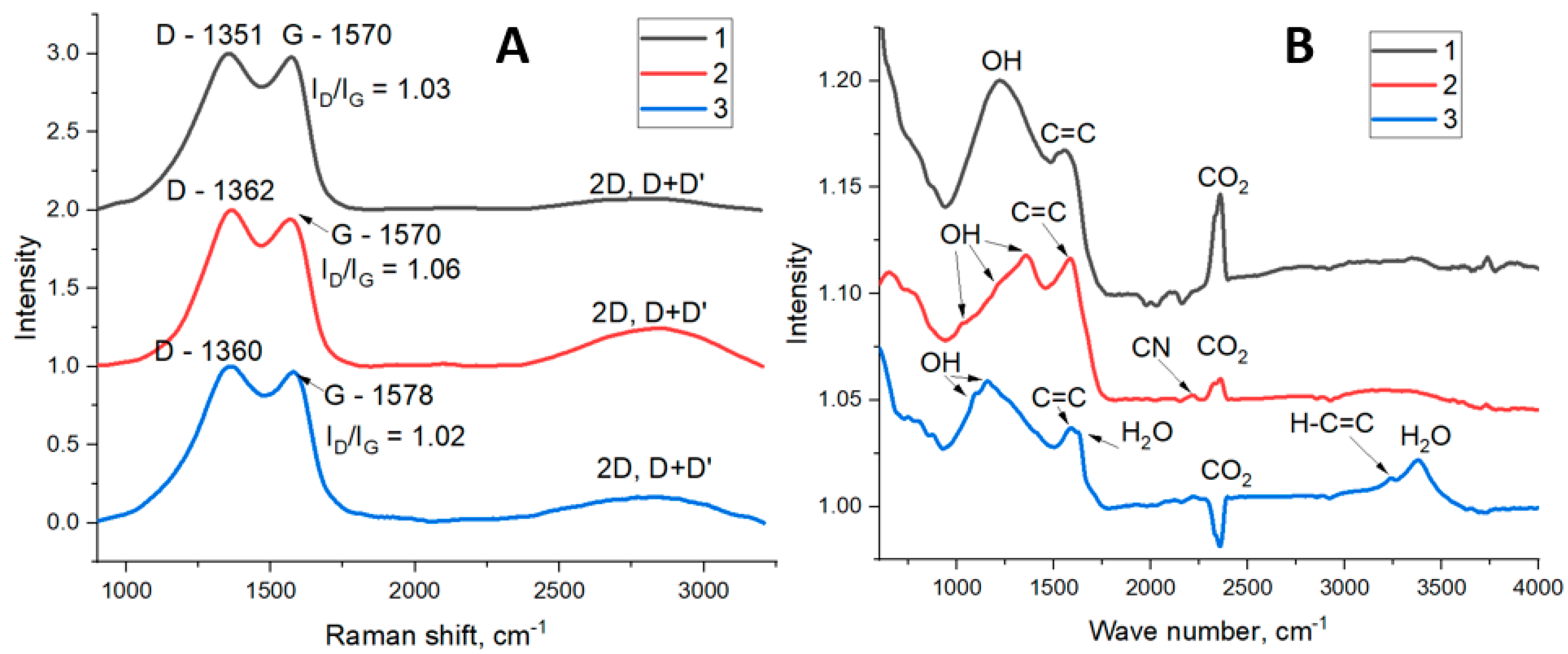

3.1. FLG from Biopolymers

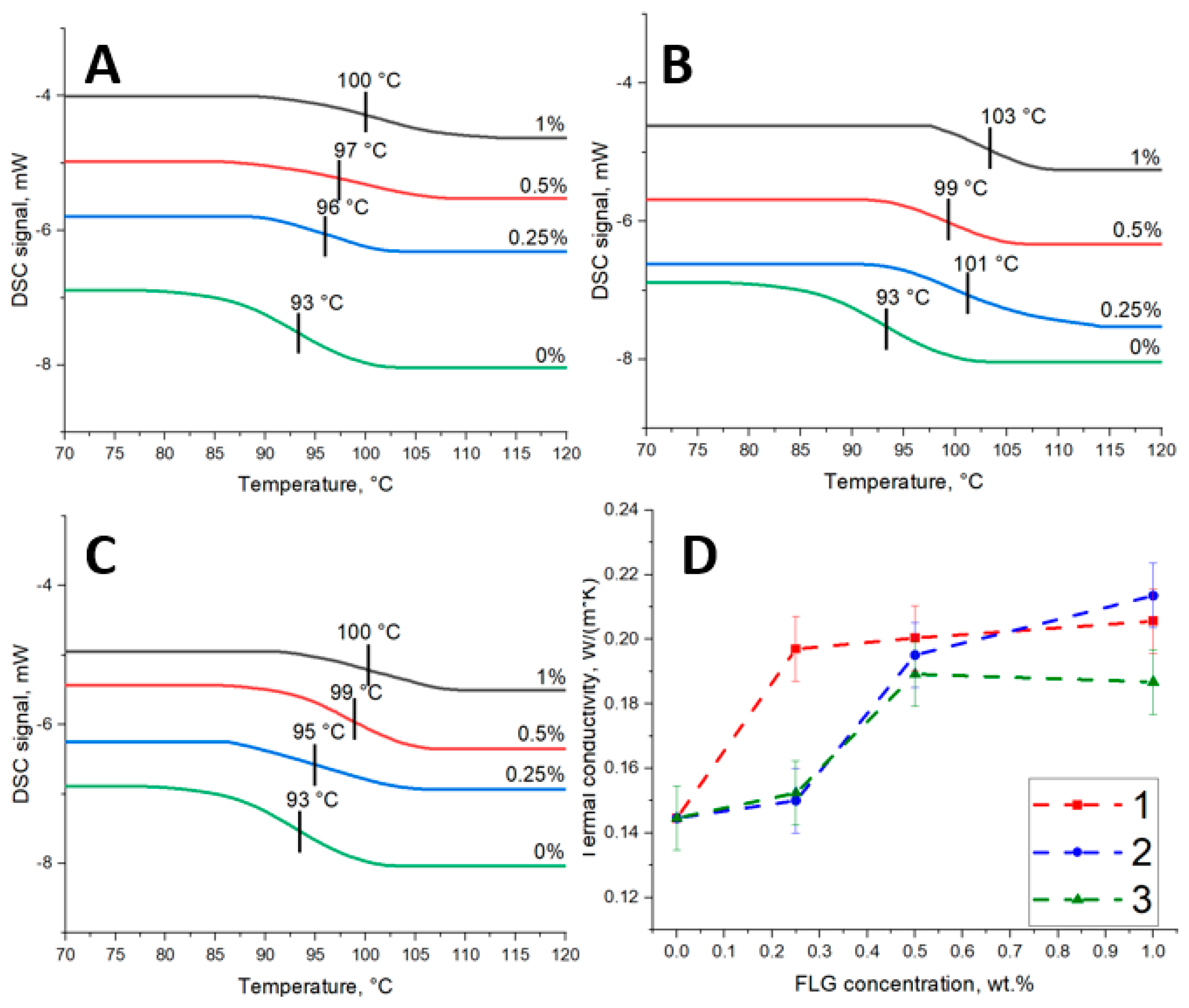

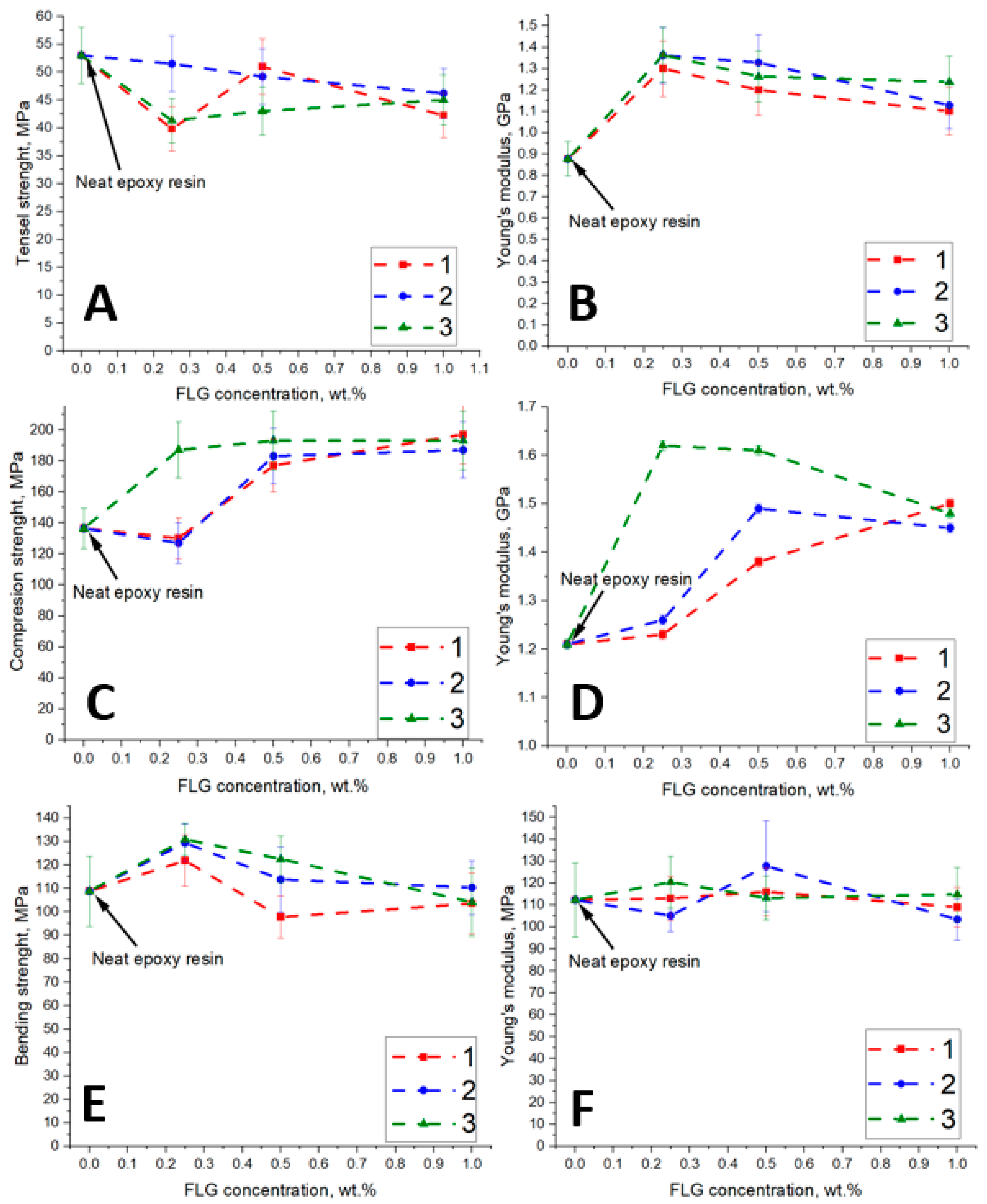

3.2. Eposy Composites

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FLG | Few layers graphene |

| GNS | Graphene nanostructure |

| GNP | Graphene nanoplates |

References

- Jin, F. L.; Li, X.; Park, S. J. Synthesis and application of epoxy resins: A review. Journal of industrial and engineering chemistry 2015, 29, 1-11.

- Mohan, P. A. Critical review: the modification, properties, and applications of epoxy resins. Polymer-Plastics Technology and Engineering 2013, 52(2), 107-125.

- Fekiač, J.J.; Krbata, M.; Kohutiar, M.; Janík, R.; Kakošová, L.; Breznická, A.; Eckert, M.; Mikuš, P. Comprehensive Review: Optimization of Epoxy Composites, Mechanical Properties, & Technological Trends. Polymers 2025, 17, 271. [CrossRef]

- Balandin, A. A.; Ghosh, S.; Bao, W.; Calizo, I.; Teweldebrhan, D.; Miao, F.; Lau, C. N. Superior thermal conductivity of single—layer graphene. Nano letters 2008, 8(3), 902-907.

- Cao, Q.; Geng, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, P.; Liu, A.; Lan, Y.; Peng, Q. A Review of Current Development of Graphene Mechanics. Crystals 2018, 8, 357. [CrossRef]

- Akter, M.; Ozdemir, H.; Bilisik, K. Epoxy/Graphene Nanoplatelet (GNP) Nanocomposites: An Experimental Study on Tensile, Compressive, and Thermal Properties. Polymers 2024, 16(11), 1483.

- Mirzapour, M.; Cousin, P.; Robert, M.; Benmokrane, B.; Dispersion Characteristics, the Mechanical, Thermal Stability, and Durability Properties of Epoxy Nanocomposites Reinforced with Carbon Nanotubes, Graphene, or Graphene Oxide. Polymers 2024, 16, 1836. [CrossRef]

- Zafeiropoulou, K.; Kostagiannakopoulou, C.; Geitona, A.; Tsilimigkra, X.; Sotiriadis, G.; Kostopoulos, V. On the Multi-Functional Behavior of Graphene-Based Nano-Reinforced Polymers. Materials 2021, 14, 5828. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Cruz, A.; Ruiz-Hernández, A.R.; Vega-Clemente, J.F.; Daniela Guadalupe Luna-Gazcón; Jessica Campos-Delgado. A review of top-down and bottom-up synthesis methods for the production of graphene, graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide. J Mater Sci 2022, 57, 14543–14578. [CrossRef]

- Merzhanov A. G. The chemistry of self-propagating high-temperature synthesis. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2004, 14(12), 1779-1786.

- Merzhanov, A. G.; Sharivker, S. Y. Self-propagating high-temperature synthesis of carbides, nitrides, and borides. Materials Science of Carbides, Nitrides and Borides. – Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands 1999. 205-222.

- Lidong, W.; Bing, W.; Pei, D.; Qinghua, M.; Zheng, L.; Fubiao, X.; Jingjie, W.; Jun, L.; Robert, V.; Weidong, F. Large-scale synthesis of few-layer graphene from magnesium and different carbon sources and its application in dye-sensitized solar cells. Materials & Design 2016, 92, 462-470. [CrossRef]

- Voznyakovskii, A. P.; Vozniakovskii, A. A.; Kidalov, S. V. New Way of Synthesis of Few-Layer Graphene Nanosheets by the Self Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis Method from Biopolymers. Nanomaterials 2022, 12(4), 657. [CrossRef]

- Voznyakovskii, A. P.; Neverovskaya, A. A.; Vozniakovskii, A. A.; Kidalov, S. V.; A Quantitative Chemical Method for Determining the Surface Concentration of Stone–Wales Defects for 1D and 2D Carbon Nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2022, 12(5), 883. [CrossRef]

- Kidalov, S. V.; Voznyakovskii, A. P.; Vozniakovskii, A. P.; Titova, S. I.; Auchynnikau, Y. V. The Effect of Few-Layer Graphene on the Complex of Hardness, Strength, and Thermo Physical Properties of Polymer Composite Materials Produced by Digital Light Processing (DLP) 3D Printing. Materials 2023, 16, 1157. [CrossRef]

- X. Díez-Betriu, S.; Álvarez-García, C.; Botas, P.; Álvarez, J.; Sánchez-Marcos, C.; Prieto, R.; Menéndez, A. de Andrés. Raman spectroscopy for the study of reduction mechanisms and optimization of conductivity in graphene oxide thin films. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2013, 1(41), 6905-6912. [CrossRef]

- Andrea C. Ferrari, Denis M. Basko. Raman spectroscopy as a versatile tool for studying the properties of graphene. Nature Nanotech 2013, 8, 235–246. [CrossRef]

- Ţucureanu, V.; Matei, A.; Avram, A. M. FTIR Spectroscopy for Carbon Family Study. Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry 2016, 46(6), 502–520. [CrossRef]

- Vozniakovskii, A. A.; Voznyakovskii, A. P.; Kidalov, S. V.; Otvalko, J.; Neverovskaia, A. Yu. Characteristics and mechanical properties of composites based on nitrile butadiene rubber using graphene nanoplatelets, J. Compos. Mater 2020, 54(23), 3351-3364. [CrossRef]

- Chih-Chun, T.; Chen-Chi, M. M.; Chu-Hua, L.; Shin-Yi, Y.; Shie-Heng, L.; Min-Chien, H.; Ming-Yu, Y.; Kuo-Chan, C.; Tzong-Ming, L. Thermal conductivity and structure of non-covalent functionalized graphene/epoxy composites. Carbon 2011, 49(15), 5107-5116. [CrossRef]

- Fuzhong, W.; Lawrence, T. D.; Yan, Q.; Zhixiong, H. Mechanical properties and thermal conductivity of graphene nanoplatelet/epoxy composites. J Mater Sci 2015, 50, 1082–1093. [CrossRef]

- Yuan-Xiang, F.; Zhuo-Xian, H.; Dong-Chuan, M.; Shu-Shen, L. Thermal conductivity enhancement of epoxy adhesive using graphene sheets as additives. International Journal of Thermal Sciences 2014, 86, 276-283. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; Cheng, Y.; Pei, Q.X.; Wang, C.M.; Xiang, Y. Thermal conductivity of defective graphene. Physics Letters A 2012, 376, 3668-3672. [CrossRef]

- Long-Cheng, T.; Yan-Jun, W.; Dong, Y.; Yong-Bing, P.; Li, Z.; Yi-Bao, L.; Lian-Bin, W.; Jian-Xiong, J.; Guo-Qiao, L. The effect of graphene dispersion on the mechanical properties of graphene/epoxy composites. Carbon 2013, 60, 16-27. [CrossRef]

- Prolongo, M. G.; Salom, C.; Arribas, C.; Sánchez-Cabezudo, M.; Masegosa, R. M.; Prolongo, S. G. Influence of graphene nanoplatelets on curing and mechanical properties of graphene/epoxy nanocomposites. J Therm Anal Calorim 2016, 125, 629–636. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Fan, X.; Huang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, M. Experimental and theoretical evaluations on the parallel-aligned graphene oxide hybrid epoxy composite coating toward wear resistance. Carbon 2024, 217, 118629. [CrossRef]

- Littmann, W. E.; Widner, R. L. Propagation of Contact Fatigue from Surface and Subsurface Origins. J Basic Eng 1966, 88, 624–635. [CrossRef]

- Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Title of the chapter. In Book Title, 2nd ed.; Editor 1, A., Editor 2, B., Eds.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 154–196.

| Sample | C, at. % ± 1% | O, at. % ± 1% | N, at. % ± 1% |

|---|---|---|---|

| FLG from cellulose | 84 | 6 | 10 |

| FLG from glucose | 78 | 11 | 11 |

| FLG from lignin | 89 | 7 | 4 |

| Sample | BET sample, м2/g ± 6% | Vpore, ml/g ± 6% | Vmicro, ml/g ± 6% |

|---|---|---|---|

| FLG from cellulose | 340 | 0.225 | 0.12 |

| FLG from glucose | 75 | 0.109 | 0 |

| FLG from lignin | 238 | 0.188 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).