1. Introduction

In recent years, polymers with self-healing capabilities have attracted increasing research interest in develop various high-performance materials due to their ability to repair damage and maintain mechanical properties [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The Diels-Alder (DA) reaction, known for its excellent thermal reversibility, is widely used in the design of self-healing materials [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. The most commonly used DA reaction system is the furan-maleimide system. The DA bonds break at high temperatures, and the system releases furan and maleimide moieties. Upon cooling to lower temperatures, the furan and maleimide moieties undergo cycloaddition to form covalent bonds, which enables the material to self-heal [

11,

12].

Incorporation of nanoscale fillers in the resin matrix improves the distinctive properties of composites, such as mechanical, thermal, electromagnetic and optical behaviors [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Graphene is a two-dimensional (2D) with only single-atom-thick (0.335 nm), and the nanosheet layer has a hexagonal lattice structure of sp2 carbon atom arrangement. A large π-electron conjugate structure in the six-membered ring plane gives graphene structural stability and excellent electrical, mechanical, and thermal properties. Due to these specificities, graphene is widely used in nanocomposites [

20,

21,

22].

2D nanomaterials are widely used in self-healing materials to improve mechanical properties and add functional properties [

9,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Xiao Kuang et al. reacted furan-based multi-wall carbon nanotube furfurylamine (MWCNT-FA) and styrene-butadiene rubber with bifunctional maleimide to generate covalent bond, which can reversibly crosslink in the rubber composites [

27]. The results show that Young’s modulus and toughness of rubber nanocomposites with MWCNT-FA are increased by more than 200-300%. Yuting Zou et al. added 2D Mxene nanomaterials to prepare self-healing composite via furan-based modified bisphenol A epoxy with bismaleimide [

28]. The results show that the composites have good reparative properties with 2.80 wt% of Mxene nano self-healing layers, which increased the pencil hardness from HB to 5H and the polarization resistance from 4.3 MΩ cm

-2 to 428.3 MΩ cm

-2.

In present work, We report a self-healing nanocomposite based on the mechanical properties of modified graphene-reinforced resin with furan functional groups. A tetrafunctional furanoaniline trimer (TAFT) was synthesized and graphene (G) was modified to obtain organically modified graphene (TAFT-G). TAFT-G/self-healing conductive nanocomposites were prepared by DA reaction of furfuramine (FA) modified DGEBA (DGEBA-FA) and furfuryl functionalized graphene (TAFT-G) with bismaleimide (BMI). TAFT-G can react with BMI curing agent through furan groups in the modifier and participate in the formation of resin cross-linking network. TFAT-G plays triple role as an enhancer, repair agent, and conductive agent in the composite material.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

DGEBA epoxy resin is provided by Nantong Xingchen Synthetic Materials Co., Ltd. The bismaleimide is sourced from Honghu Bismaleimide New Materials Technology Co., Ltd. Epoxy chloropropane, furfuryl alcohol, furfurylamine, p-phenylenediamine sulfate, and aniline are purchased from Shanghai Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd. Graphene is sourced from Angxing Carbon Materials Changzhou Co., Ltd.

2.2. Preparation of Modifiers

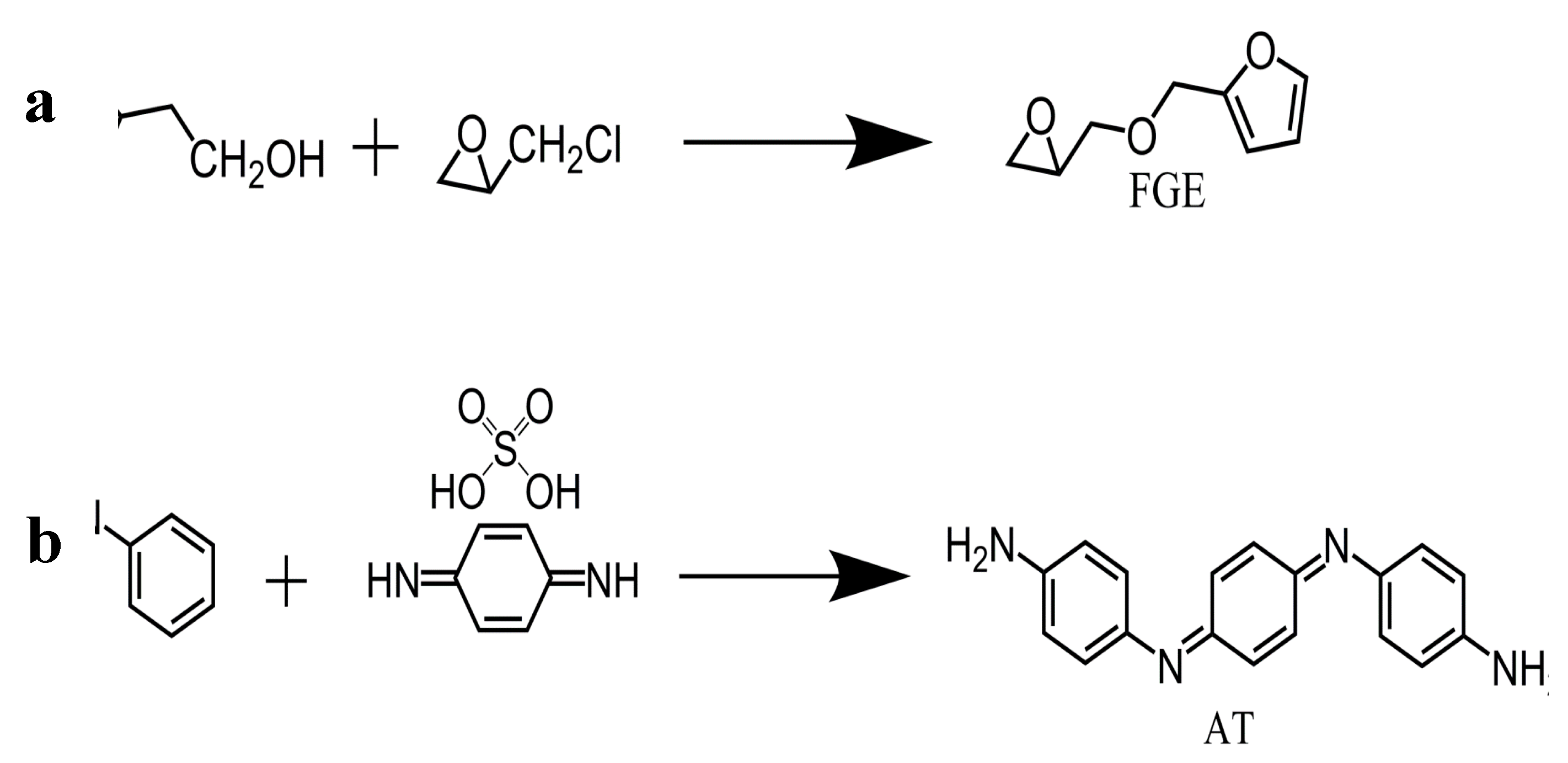

The synthesis of furfuryl glycidyl ether (FGE) is prepared as follows (

Figure 1a) : In a 750 mL three-neck round-bottom flask, add epichlorohydrin (176.30 g, 2.0 mol) and tetrabutylammonium hydrogen sulfate (6.17 g, 3.5%) while maintaining the system temperature in an ice-water bath at 0°C. Over 30 minutes, slowly add furfuryl alcohol (94.50 g, 0.96 mol) dropwise above the solution. Within 60 minutes, add a 50 wt% NaOH aqueous solution (210 mL) to the mixture while controlling the system temperature not exceed 10°C. After 3.5 hours, wash the crude product three times with water, collect the organic layer, and dry it with anhydrous magnesium sulfate for 24 hours. Remove the solvent using a rotary evaporator. Purify the product (FGE), using silica gel column chromatography with ethyl acetate/hexane (5:1) as the mixed solvent. The yield of FGE is 82% [

29].

The synthesis of benzene trimer (AT) via the route is carried out as follows (

Figure 1b): In a round-bottom flask equipped with a condenser, add p-phenylenediamine sulfate (13.30g), aniline (8.34 g), and 675 ml of 1M HCl solution. Place the flask in an ice-water bath and mix well. Dissolve ammonium persulfate (18.93g) in 225 ml of 1M HCl solution. Using a dropping funnel, add the ammonium persulfate solution dropwise to the above solution one drop per second. After the addition is complete, stir for 1 hour. Pour the reaction mixture into a Buchner funnel and wash the product thoroughly with deionized water. Transfer the product to a solution of 10 wt% NH

3·H

2O and stir overnight. Vacuum filtrate and wash the product with deionized water. Place the product in a petri dish, air dry, and then dry overnight at 40℃ under vacuum. The yield is 65% [

30].

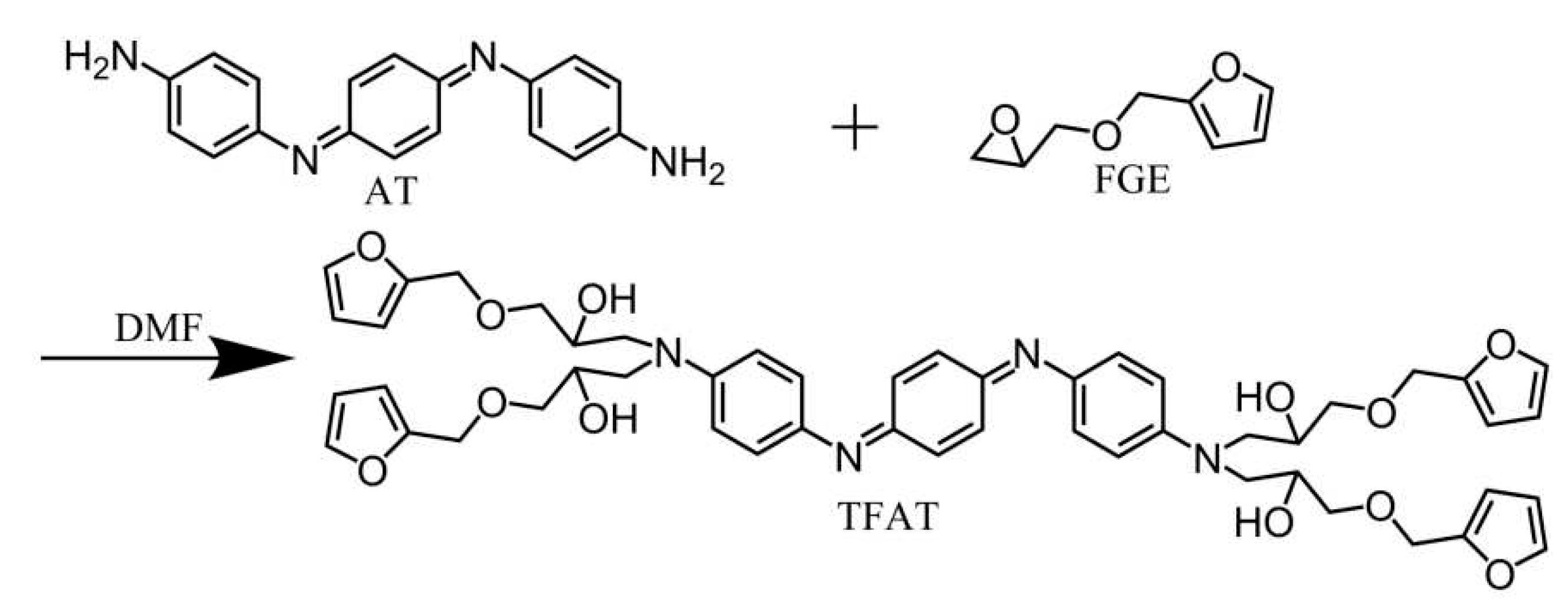

The synthesis of benzene trimer, containing TFAT, as follows (

Figure 2): Dissolve AT and furyl FGE in dry N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) with an equimolar ratio of 1:6 (with excess FGE). This results in a 20 wt% DMF solution. Carry out the reaction at approximately 150℃ for 48 hours. After the reaction, remove the solvent with a rotary evaporator. The collected viscous liquid is washed multiple times with toluene, then dried at room temperature under vacuum. The yield of TFAT (viscous liquid) is approximately 80% [

19].

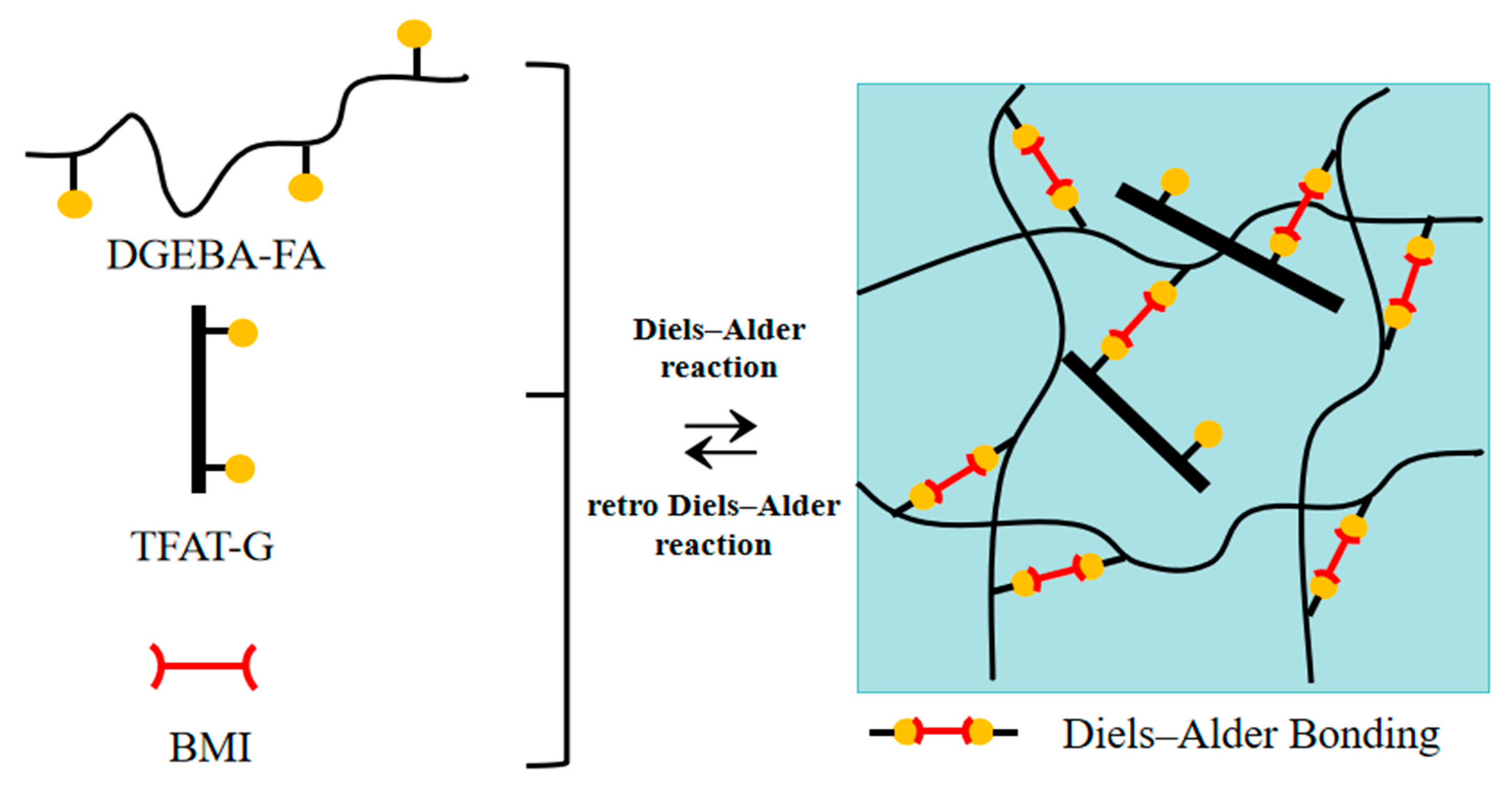

2.3. Viscosity TFAT-modified Graphene

The preparation process of TFAT-intercalated modified graphene is shown in

Figure 3. Prepare 5.31 g TFAT and dissolve it in 60 milliliters of tetrahydrofuran (THF) solvent. Sonicate the solution for 40 minutes to ensure complete dissolution of TFAT. Prepare graphene and add it to the TFAT solution in a mass ratio of 3:1 (graphene to TFAT). Continue sonication of the mixed solution for 60 minutes till TFAT reach intercalation into the graphene layers. Remove the solvent by using a rotary evaporator to evaporate the THF from the solution, leaving behind TFAT-G [

31].

2.4. The Preparation of Self-healing Nanocomposite Materials

To prepare the self-healing nanocomposites, 72 g DGEBA and 20.55 g FA are dissolved in 60 g DMF in a sealed conical flask. The solution is heated using an oil bath at 90℃. The reaction is stirred continuously for a constant 6 hours. After ensuring no precipitations come out, the DMF solution is removed. The polymer/DMF solution (10.17 g, containing 4.425 g polymer) is mixed with 0.789 g BMI. A certain amount of modified graphene (TFAT-G) is dispersed in 1mL of DMF using ultrasound for 1 hour, and then added to the mixture and vigorously stirred while degassed under vacuum. The mixture is poured into a polytetrafluoroethylene mold and cured at 60℃ for 24 hours [

18].

2.5. Characterizations

1H-NMR spectra were recorded with a 400 MHz AVANCE III NMR spectrometer. The FTIR spectrum was recorded with a NICOLET 6700 spectrometer instrument. The scanning range for the infrared spectroscopy is from 400 cm-1 to 4000 cm-1. DSC analysis was performed using a NETZSCH 214 instrument with the flow rate of 20 mL/min. The dispersion state of graphene nanocomposites was observed by RENISHAW confocal microraman spectrometer. The wave number range of the test is 500 to 4000 cm-1, and the test frequency is 0.1Hz. The samples were carried on a 200-mesh copper net, and the TEM images were obtained by Japanese JEOL JEM-1011 transmission electron microscopy. The surfaces of samples were examined via a FEI Quanta FEG 250 scanning electron microscope. The surfaces were sputter-coated with gold before taking the scanning electron micrographs. The mechanical properties were tested on an Instron 5967 instrument. The test standards for tensile were GB/T 1040. At least five parallel samples were measured for each component and averaged. The BEST-121 resistivity tester of Beiguang Instrument and Equipment Company was used to test the resistivity of nanocomposites.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of TFAT Modifiers

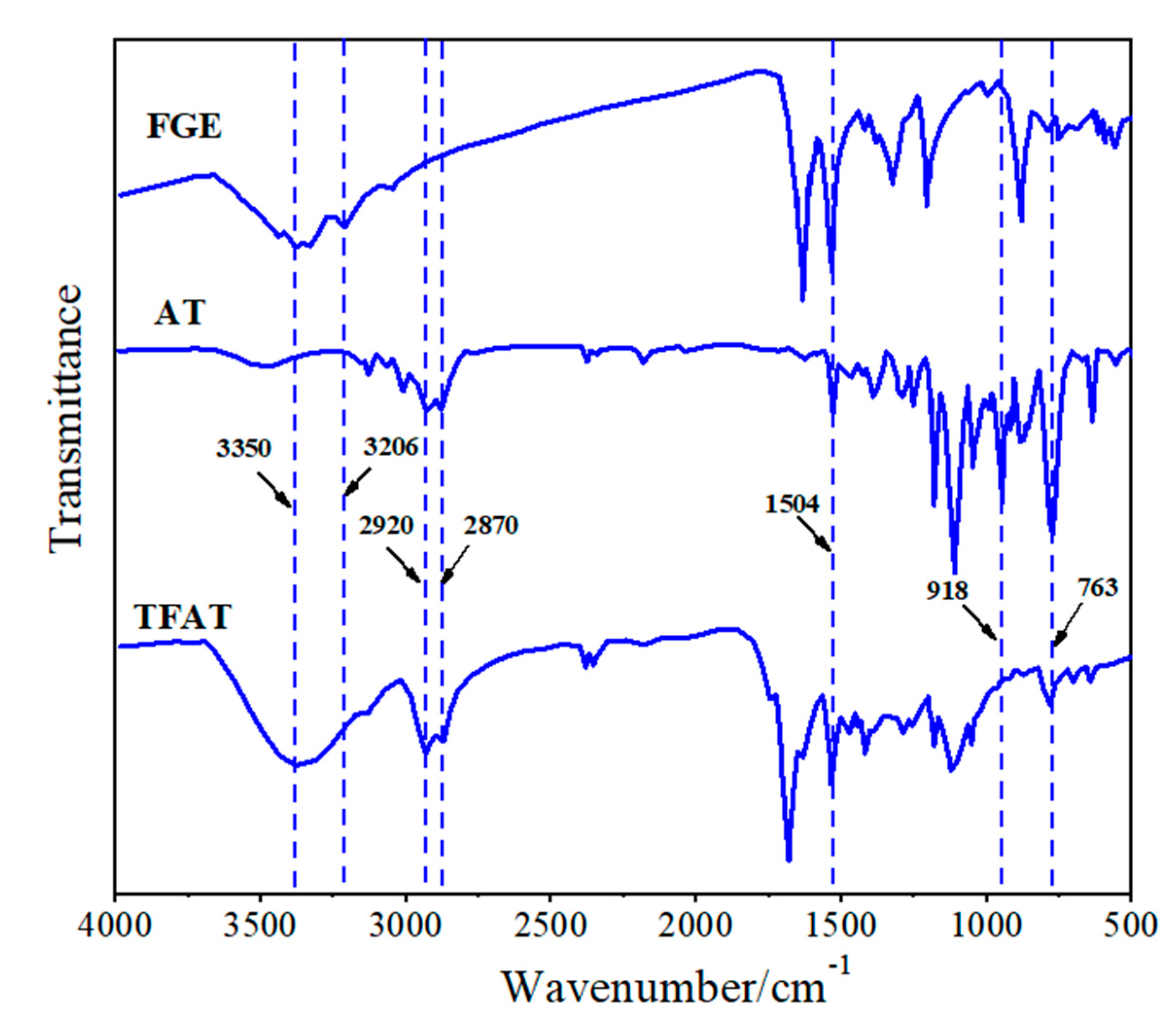

The synthesized AT, FGE, and TFAT are analyzed by FTIR (Figfure 4). The absorption peaks of FGE and TFAF at 763 cm-1 are characteristic of the furan ring. The peaks of AT and TFAT at 1504 cm-1 are characterized as the benzene ring. The peaks at 2870 cm-1 and 2920 cm-1 are the stretching vibration of methylene. The stretching vibration of the methylene groups are seen at 2870 cm-1 and 2920 cm-1. The absorption peaks at 3206 cm-1 and 918 cm-1 are amino group of AT and the epoxy group of FGE, respectively. Due to the addition reaction between the amino and epoxy groups, the absorption peaks of the amino and epoxy groups in TFAF disappeared, and the generated -OH group by the formation reaction is appeared at 3350 cm-1.

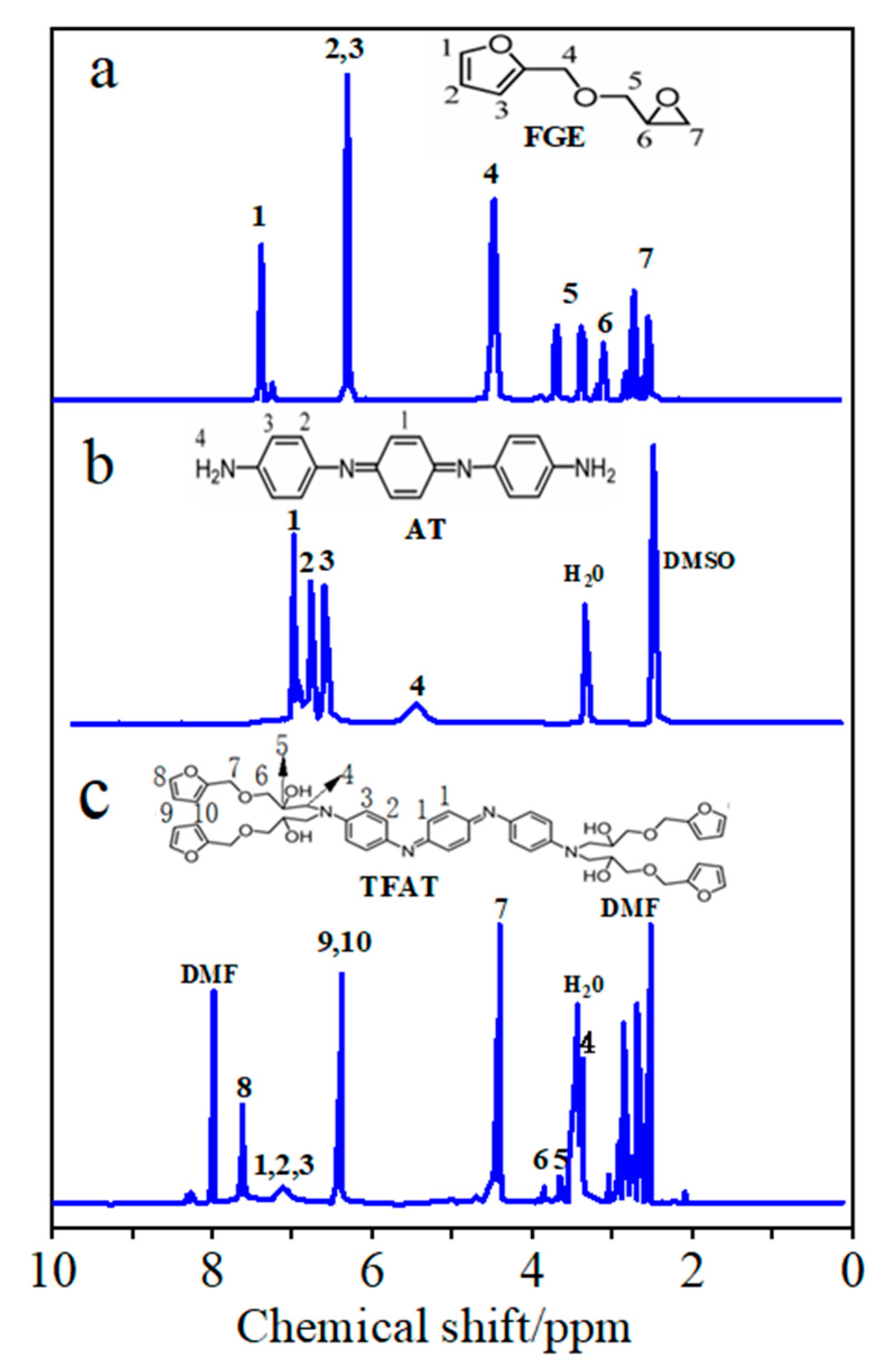

From the NMR hydrogen spectrum of FGE (

Figure 5a), the signal peaks with chemical shifts at 2.65 ppm and 2.75 ppm are characteristic peaks of protons (7) in the ethylene oxide ring, while the signal peaks with chemical shifts at 3.42 ppm and 3.85 ppm are characteristic peaks of -CH

2 (5) in the ethylene oxide ring. The signal peak with chemical shift at 3.22 ppm is the characteristic peak of the proton of -CH adjacent to the ethylene oxide ring (6). The chemical shifts at 6.2, 6.3, and 7.4 ppm correspond to protons 2, 3, and 1 in the furan ring, respectively. In addition, the signal at 4.5 ppm corresponds to the proton to -OCH

2 that is partially attached to the furan ring by the glycidyl ether (4). Under the solvent condition of CDCl

3, the signal at 7.26 ppm is the solvent peak.

In the NMR hydrogen spectrum of AT (

Figure 5b), the signal peak at 5.50 ppm is attributed to the aniline trimer-terminal amine proton hydrogen (4). The three signal peaks in the 6.5-7.2 ppm interval are the characteristic peaks of the protons on the benzene ring of the aniline trimer as well as on the quinone ring (1,2,3), and the solvent peak of DMSO is at 2.5 ppm.

As the TFAT NMR hydrogen spectrum (

Figure 5c), the chemical shift at 6.88 -7.31 ppm exhibits three signal peaks as aniline trimer benzene ring characteristic peaks (1, 2, 3). Chemical shifts at 6.42 ppm and 7.61 ppm were characteristic peaks for furan group protons (8, 9, 10). The signal peak at 4.50 ppm of chemical shift is the proton characteristic peak of -CH

2O- attached to the furan ring (7). The characteristic peak at 3.42 mm chemical shift is the proton characteristic peak of -NCH

2- (4), which has some overlap with the signal peak of water); the characteristic peak at 3.78 ppm chemical shift is the proton peak of -OCH

2CH(OH) (6), and the characteristic peak at 3.62 ppm chemical shift is the proton peak of -OCH

2CH(OH) (5).

3.2. Characterization of TFAT-modified Graphene

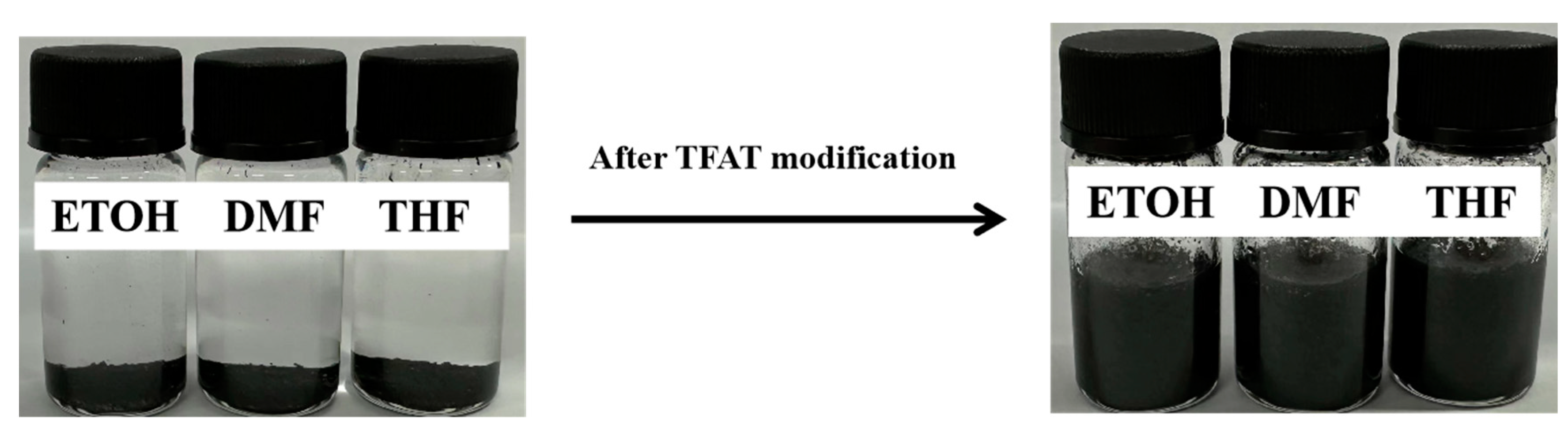

Unmodified graphene flakes is easily agglomerated and difficult dispersed in the organic solvents because of the intermolecular van der Waals forces. The modification of graphene by organics makes graphene to be efficiently dispersed in organic solvents, which likewise expand the application range of graphene. In this study, graphene is modified and dispersed by TFAF, achieving dispersing graphene via the strong π-π conjugation between graphene and TFAF. As shown in

Figure 6, unmodified graphene are precipitated in the organic solvent, and after adding aniline trimer as the dispersant, the graphene can be dispersed in the organic solvent very uniformly.

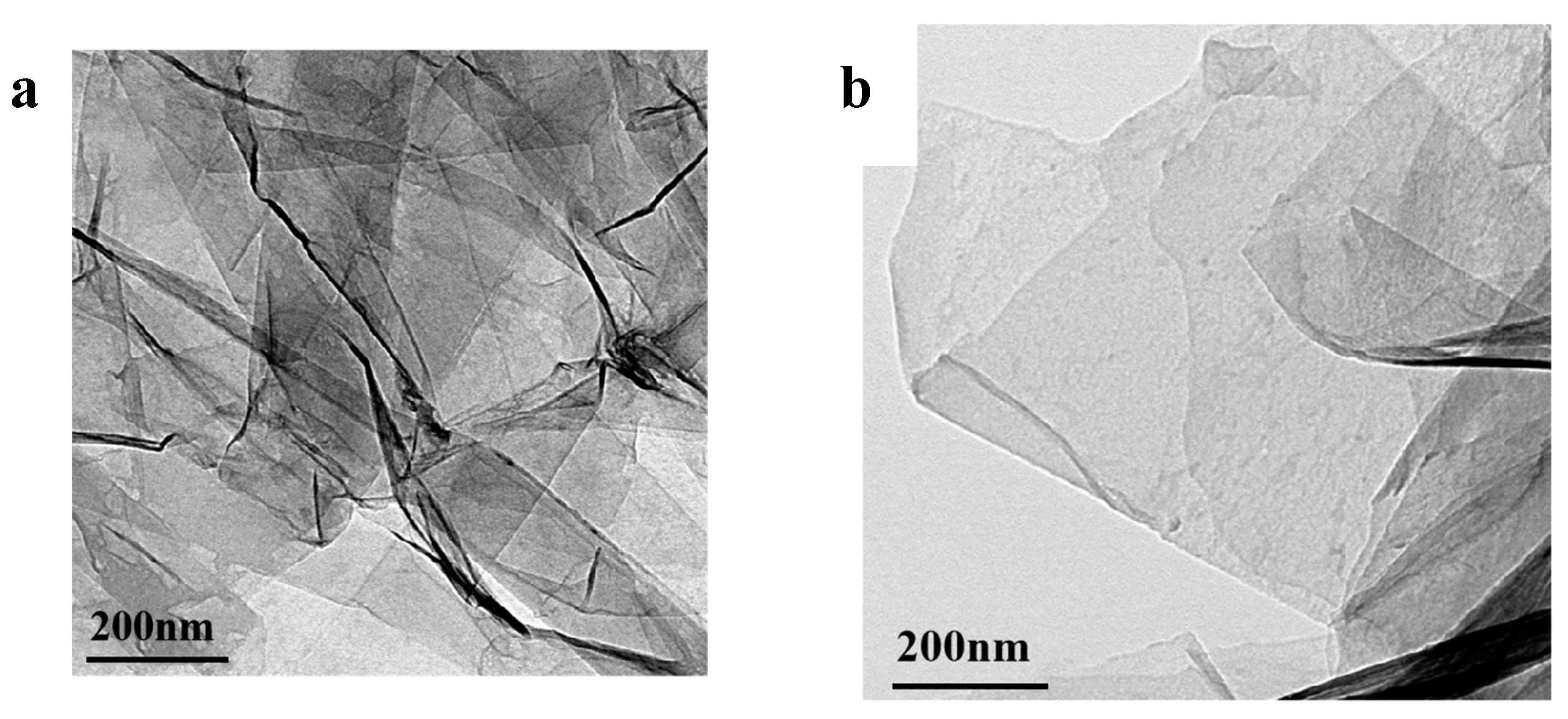

From the TEM photos of graphene before and after modification, the unmodified graphene has more lamellae stacked together (

Figure 7a). After modified, TFAF was inserted into the interlayers of graphene, and the stacked lamellae were exfoliated by ultrasonic treatment, and the lamellar stacking phenomenon was significantly improved (

Figure 7b). Meanwhile, the TFAF-modified graphene showed better compatibility with resin than unmodified graphene.

3.3. Dispersion State of Graphene in Resin Before and After Modification

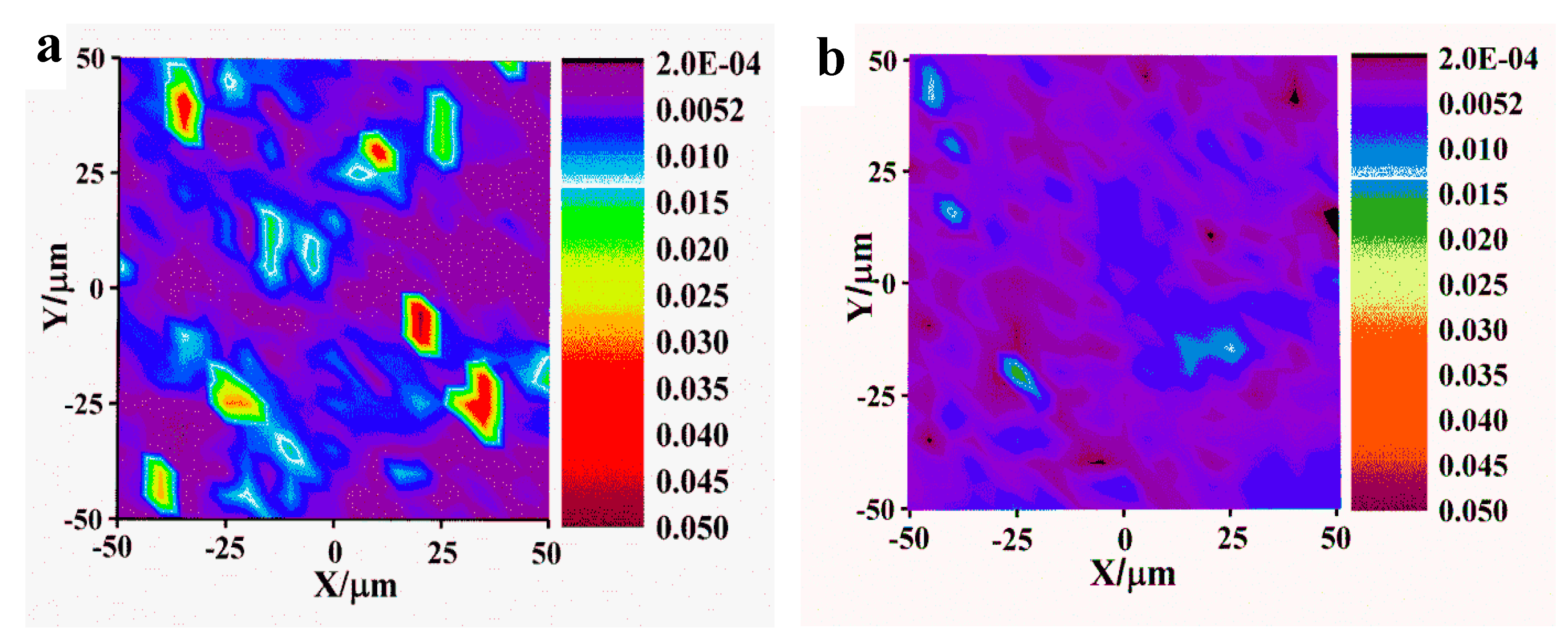

The Raman photographs of TFAT modified and unmodified graphene/ resin nanocomposites (

Figure 8). The overall dispersion of graphene in the resin matrix before modification is poor, and the phenomenon of graphene lamellae accumulation occurs. The dispersion is improved after TFAF modified graphene in the epoxy resin matrix, and the overall distribution is more uniform without graphene lamellae or agglomeration phenomenon.

3.4. Characterization of TFAT-modified Graphene

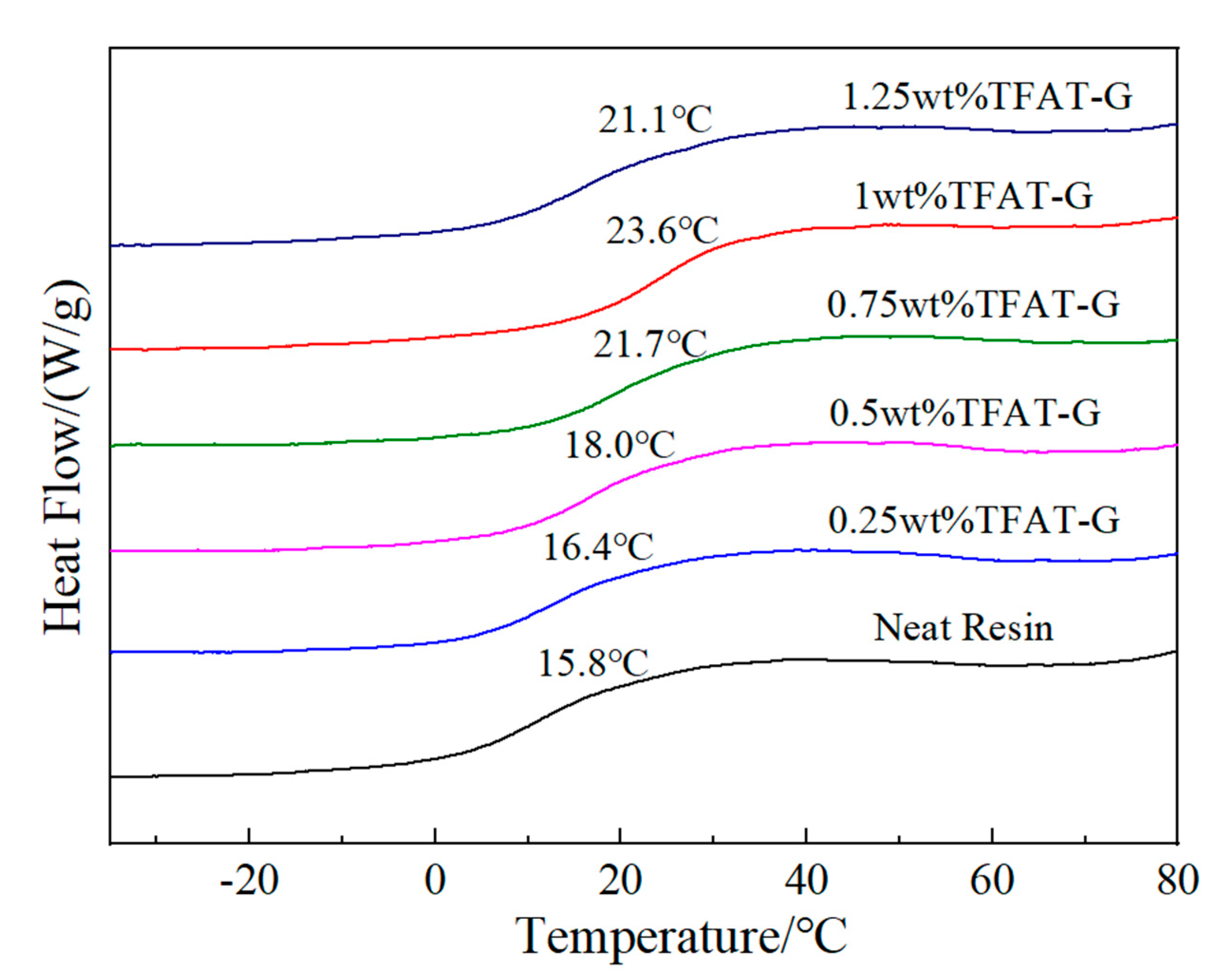

The epoxy resin graphene nanocomposites is tesed by DSC, and the Tg of the pure resin is 15.8℃ (

Figure 9). The addition of TFAF-G substantially increased the Tg of the epoxy resin, which reaches maximum 23.6℃ when mass fraction is 1 wt%. TFAF-G contains functional groups that can participate in the curing reaction, which makes the graphene lamellae linked to the epoxy resin matrix through chemical bonding. Also, the binding effect on the resin matrix is noticeably intensified, which cuased a significantly increase in the Tg of the epoxy resin. When the TFAT-G content was increased to 1.25 wt%, the Tg of the composites was 21.1℃, which was decreased compared with 1 wt% TFAT-G composites. The excess TFAT-G consumed too much BMI curing agent to reduct the cross-linking degree of the resin matrix, which ultimately led to the decrease of the Tg of the composites.

3.5. Characterization of tensile properties of TFAT-G/resin nanocomposites

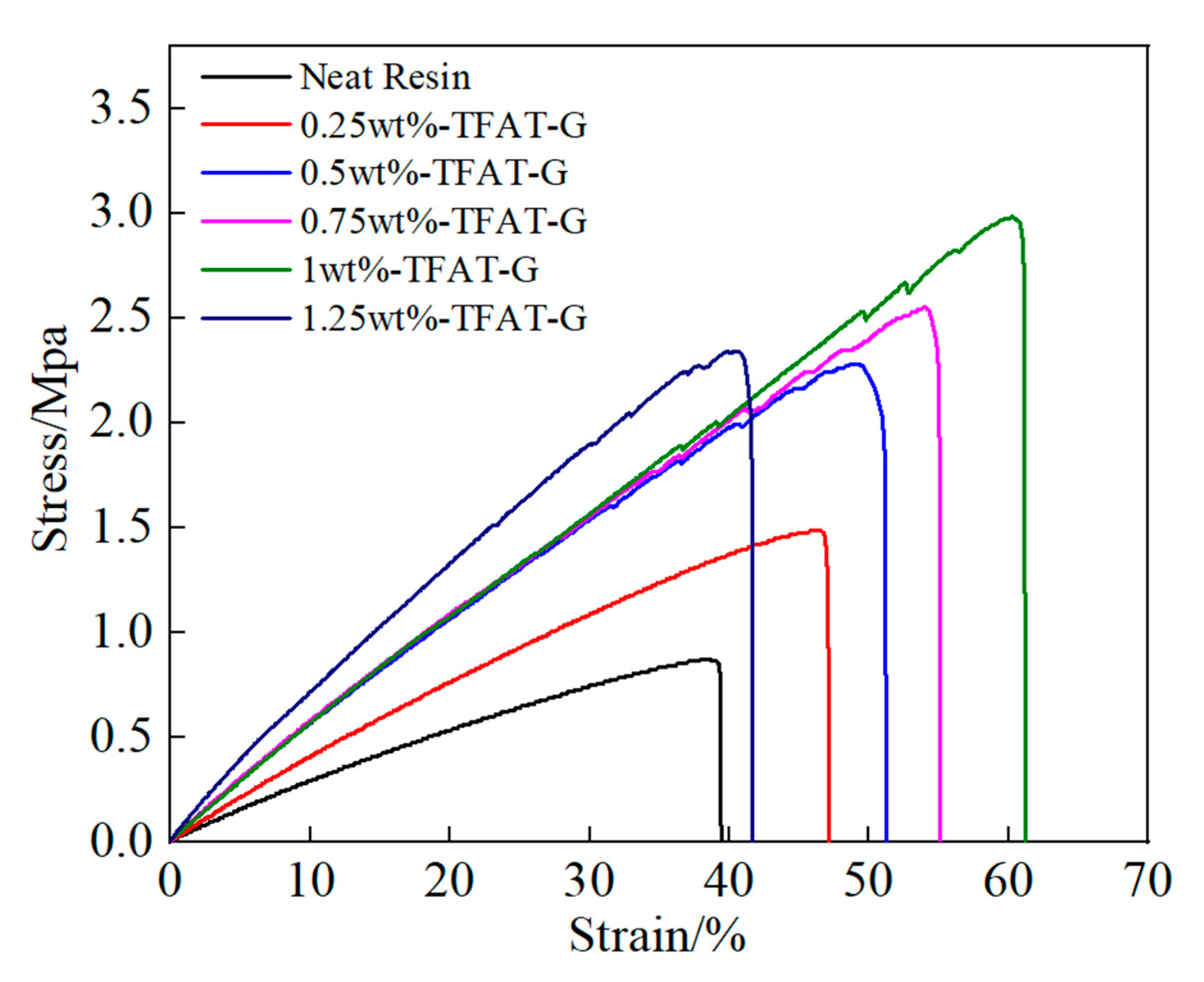

The pure epoxy resin composites and TFAT-G/resin nanocomposites are analyzied in stress-strain (

Figure 10). The tensile strength of the nanocomposites continueously increased with the higher content of TFAF-G. The maximum enhancement in tensile strength was up to 233% as 1 wt% TFAF-G added in composites. The addition of TFAF-G not only improved the tensile strength of the epoxy resin, but also resulted in a significant increase in elongation at break and modulus. The 1 wt% TFAF-G composites resulted in the maximum elongation at break of 63%, attributed to the functional groups on the TFAF molecules. They participate in the curing reaction and construct chemical bonds between the graphene lamellae and the epoxy resin matrix. The formation of strong interfacial forces allowed the stress to be effectively conducted. The composites with 1.25 wt% of TFAF-G resulted in the highest modulus improvement to 83%. It is typical to add graphene in epoxy resin for improvements of modulus since the construction of strong interfacial interaction, in which the reinforcing effect of graphene is efficiently reflected.

3.6. Characterization of conductive properties of TFAT-G/resin nanocomposites

The electrical conductivity data of TFAT-G/resin nanocomposites is shown in

Figure 11. The surface resistance, surface resistivity and volume resistivity of the pure epoxy resin were 2.38 × 10

10 Ω, 1.94 × 10

12 (Ω/cm

2) and 2.73 × 10

12 (Ω·cm), respectively. As the increasing TFAT-G concent, the electrical conductivity of the epoxy resin presented substantial enhancement. When 1.25 wt% was added, the surface resistance, surface resistivity and volume resistivity decreased to 8.31 × 10

2 Ω, 6.78 × 10

4 (Ω/cm

2) and 9.51 × 10

4 (Ω·cm), respectively. The homogeneous dispersion of graphene in the resin resin cause the reduction in the conductive threshold value. Only a small amount of graphene improved the conductive properties of the material.

3.7. Characterization of the reparative properties of TFAT-G/resin nanocomposites

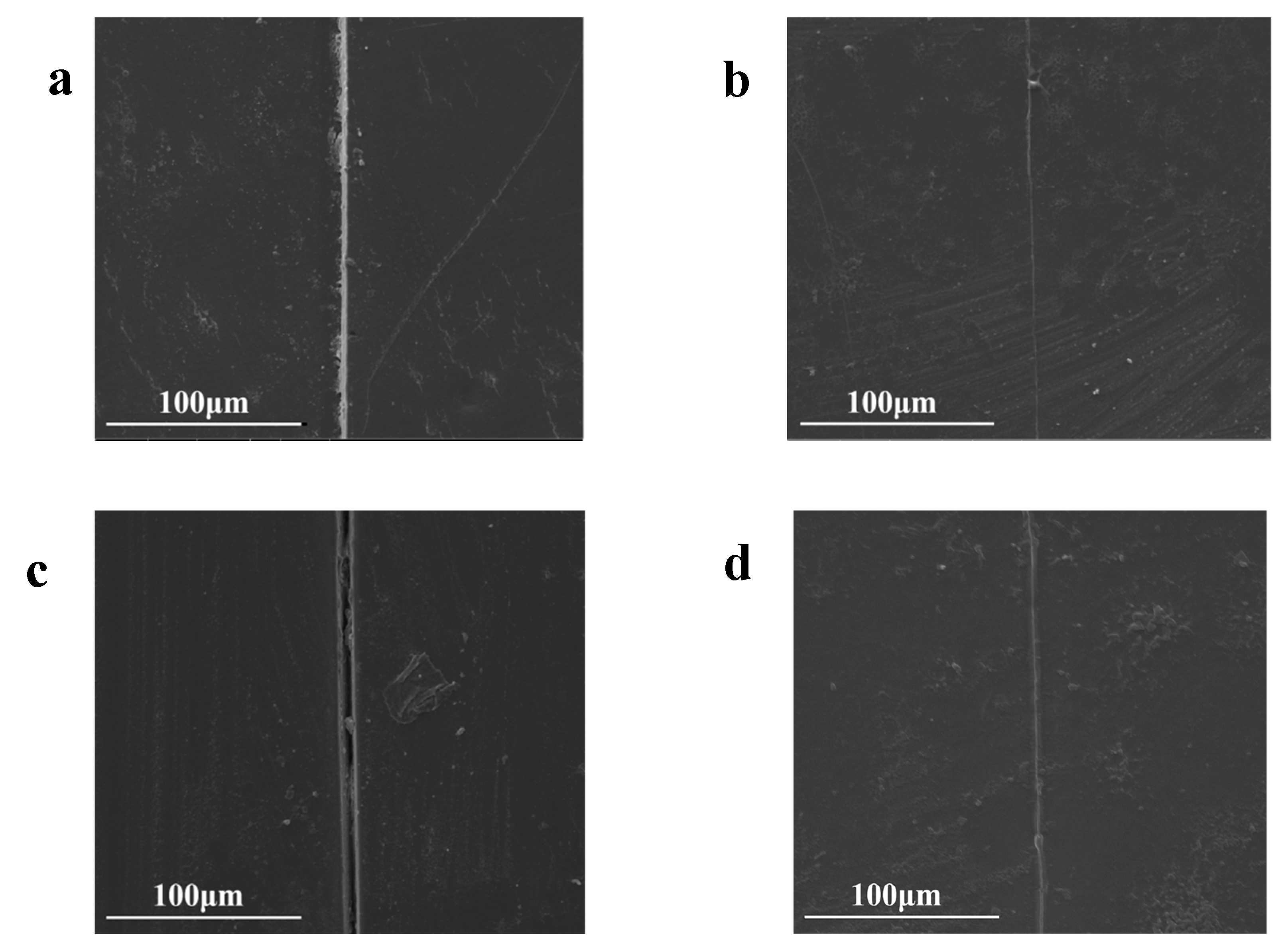

TFAT-G/resin nanocomposite section repair was observed by SEM (

Figure 12).Because of the presence of furan-bismaleimide Diels-Alder covalent bond in the resin, it has a certain ability of self-healing by heating. Both the neat resin and the nanocomposites with 1 wt% TFAT-G added were re-healed after be heated to 150℃ for 30 minutes.

To compare the remaining stress strength, both the neat resin composites and 1 wt% TFAT-G composites were tested in the method of GB/T 1050 before and after 1 repair cycle (

Figure 13). Either composites were heated for a repair cycle. 1 wt% TFAT-G composites presented double stress strength then neat resin composites. Additionally, 1 wt% TFAT-G composites maintained four times higher stress strength than neat resin composites after one repair cycle. As result, the addition of 1 wt% TFAT-G increased the stress strength of neat resin composite and maintained 80% properties after one repair cycle.

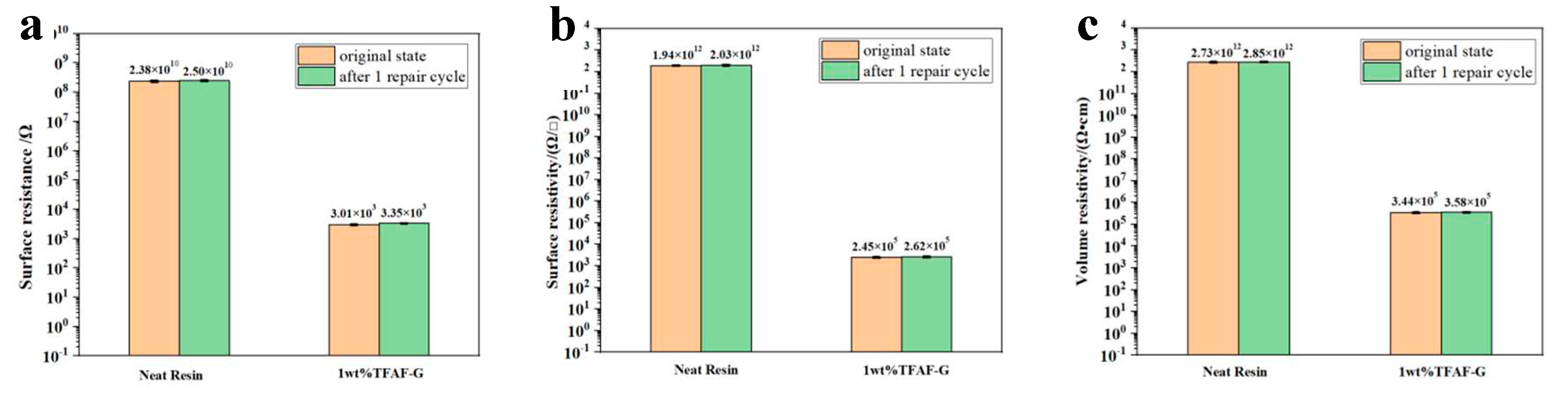

As the characterized conductivity of TFAT-G/resin composites, the remaining conductivity was tested after one repair cycle (

Figure 14). The surface resistance, surface resistivity and volume resistivity of the resin with 1 wt% TFAF-G were 3.01 × 10

3 Ω, 2.45 × 10

5 (Ω/cm

2), and 3.44 × 10

5 (Ω·cm). After one repair cycle, The surface resistance, surface resistivity and volume resistivity of the resin with 1 wt% TFAF-G were increased to 3.35× 10

3 Ω, 2.62 × 10

5 (Ω/cm

2), and 3.58 × 10

5 (Ω·cm), respectively. Either neat resin composites or 1 wt% TFAT-G composites were increased in surface resistance, surface resistivity, and volume resistivity after one repair cycle.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrated nanocomposites with enhanced mechanical, self-repairing properties and electrical conductivity based on Diels-Alder reversible crosslinking bonds. The covalently and reversibly crosslinked nanocomposites were prepared by Diels-Alder reaction, using FA, DGEBA, BMI and TFAT-G. Specifically, TFAT-modified graphene efficiently influenced on enhancement, repaiation and electrical conductivity. The conductivity of the composites became higher as more content of TFAT-G added in nanocomposites. The mechanical properties of the nanocomposites were enhanced the most when 1 wt% TFAT-G was added, with 233% increased in tensile strength, 63% increased in elongation at break, and 83% increased in Young's modulus. Either the pure resin and the nanocomposites with 1 wt% TFAT-G added retained 83% of the original strength and 90% of the electrical conductivity after one heating repair cycle. We expect that such high-performance self-healing conductive composites will provide options for smart materials and potential applications in electronic engineering.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis and writing-original draft, F.W.; Investigating in the project, Y.C.Zhang.; Reviewing and editing manuscript, H.S.; Project administration, X.Y.Zhong.; Conceptualization, J.B.Bai.; methodology, Y.Z.; Investigation, J.W.Bao. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Aliotta, L.; Gigante, V.; Acucella, O.; Signori, F.; Lazzeri, A. , Thermal, Mechanical and Micromechanical Analysis of PLA/PBAT/POE-g-GMA Extruded Ternary Blends. Frontiers in Materials 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, W.; Hao, H.; Kanwal, H.; Jiang, S. , Compressive properties of self-healing microcapsule-based cementitious composites subjected to freeze-thaw cycles using acoustic emission. Frontiers in Chemistry 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kampes, R.; Meurer, J.; Hniopek, J.; Bernt, C.; Zechel, S.; Schmitt, M.; Popp, J.; Hager, M.D.; Schubert, U.S. , Exploring the principles of self-healing polymers based on halogen bond interactions. Frontiers in Soft Matter 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladugu, S.R.M.; Sreekanth, P.S.R.; Sahu, S.K.; Naresh, K.; Karthick, S.A.; Venkateshwaran, N.; Ramoni, M.; Mensah, R.A.; Das, O.; Shanmugam, R. , A Comprehensive Review of Self-Healing Polymer, Metal, and Ceramic Matrix Composites and Their Modeling Aspects for Aerospace Applications. Materials. [CrossRef]

- Stocker, C.W.; Lin, M.; Wong, V.N.L.; Patti, A.F.; Garnier, G. , Modulating superabsorbent polymer properties by adjusting the amphiphilicity. Frontiers in Chemistry 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Y. , Preparation of PCU/PPy composites with self-healing and UV shielding properties. Frontiers in Materials 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, S.D.W., F. , Mendable polymers. J. Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.D., M. A.; Ono, K.; Mal, A.; Shen, H.; Nutt, S.R.; Sheran, K.; Wudl, F., A thermally re-mendable cross-linked polymeric material. Science 2002, 295, 1698–16702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhetri, S.A., N. C.; Samanta, P.; Murmu, N.C.; Kuila, T., Functionalized reduced graphene oxide/epoxy composites with enhanced mechanical properties and thermal stability. Polym. Test 2017, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanka, R.V.S.P.; Krishnakumar, B.; Leterrier, Y.; Pandey, S.; Rana, S.; Michaud, V. , Soft Self-Healing Nanocomposites. Frontiers in Materials 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Rong, M.Z.; Zhang, M.Q.; Yuan, Y.C. , Synthesis and characterization of epoxy with improved thermal remendability based on Diels-Alder reaction. Polymer International 2010, 59(10), 1339–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lv, C.; Li, Z.; Zheng, J. , Facile Preparation of Polydimethylsiloxane Elastomer with Self-Healing Property and Remoldability Based on Diels–Alder Chemistry. Macromolecular Materials and Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Chuo, T.-W.; Liu, Y.-L. , Furan-functionalized aniline trimer based self-healing polymers exhibiting high efficiency of anticorrosion. Polymer 2017, 125, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhou, S. , High-Concentration Self-Cross-Linkable Graphene Dispersion. Chemistry of Materials 2018, 30(15), 4935–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaraju, S.; Prabunathan, P.; Selvi, M.; Alagar, M. , Low dielectric and low surface free energy flexible linear aliphatic alkoxy core bridged bisphenol cyanate ester based POSS nanocomposites. Frontiers in Chemistry 2013, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L.; Chen, J.; Zou, Y.; Xu, Z.; Lu, C. , Thermally-Induced Self-Healing Behaviors and Properties of Four Epoxy Coatings with Different Network Architectures. Polymers. [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.; Huang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Du, B.; Zhang, X.; Fan, Z. , Sonochemical Transformation of Epoxy–Amine Thermoset into Soluble and Reusable Polymers. Macromolecules 2015, 48(2), 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostapiuk, M. , Microcapsules in Fiber Metal Laminates for Self-Healing at the Interface between Magnesium and Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Epoxy. Materials. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Sharma, A.K.; Shukla, D.K.; Pandey, K.N. , Effect of Self-Healing by Dicyclopentadiene Microcapsules on Tensile and Fatigue Properties of Epoxy Composites. Materials. [CrossRef]

- An, F.L., X.; Min, P.; Li, H.; Dai, Z.; Yu, Z.Z. , Highly anisotropic graphene/boron nitride hybrid aerogels with long-range ordered architecture and moderate density for highly thermally conductive composites. Carbon 2018, 126, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.H.; Ye, S.; Ding, C.D.; Tan, L.H.; Fu, J.J. , Autonomous self-healing supramolecular elastomer reinforced and toughened by graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets tailored for smart anticorrosion coating applications. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2018, 6(14), 5887–5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.Y., Y.; Gan, L.; Xu, X.; Mei, C.; Han, J. , Highly stretchable and self-healing strain sensors based on nanocellulose supported graphene dispersed in electro-conductive hydrogels. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Yang, J.P.; Hao, X.L.; Tong, T. , Fabrication and Characterization of a Modified Conjugated Molecule-Based Moderate-Temperature Curing Epoxy Resin System. Frontiers in Materials 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, N.R., A.; Khosravi, H.; Tohidlou, E. , On the mechanical behavior of basalt fibre/epoxy composites filled with silanized graphene oxide nanoplatelets. Polym. Compos 2018, 39, 2472–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, X.Z., L.; Wei, F.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Xu, T. , Fabrication of halloysite nanotubes/reduced graphene oxide hybrids for epoxy composites with improved thermal and mechanical properties. Polym. Test 2019, 76, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, K.K., K. A.; Umer, R., Experimental characterization and modeling multifunctional properties of epoxy/graphene oxide nanocomposites. Polymers 2021, 13, 2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, X.; Liu, G.; Dong, X.; Wang, D. , Enhancement of Mechanical and Self-Healing Performance in Multiwall Carbon Nanotube/Rubber Composites via Diels–Alder Bonding. Macromolecular Materials and Engineering 2016, 301(5), 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Fang, L.; Chen, T.; Sun, M.; Lu, C.; Xu, Z. , Near-Infrared Light and Solar Light Activated Self-Healing Epoxy Coating having Enhanced Properties Using MXene Flakes as Multifunctional Fillers. Polymers. [CrossRef]

- Hilf, J.S.; Poon, J.; Moers, C.; Frey, H. , Aliphatic polycarbonates based on carbon dioxide, furfuryl glycidyl ether, and glycidyl methyl ether: Reversible functionalization and cross-linking. Macromol. Rapid. Commun 2014, 36, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.Y.H., T. C.; Lin, J.C., Advanced environmentally friendly coatings prepared form amine-capped aniline trimer-based waterborne electroactive polyurethane. Mater. Chem. Phys 2013, 137, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.Z., D.; Liu, T.; Liu, Z.; Pu, J.; Liu, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Wang, L. , Superior corrosion resistance and self-healable epoxy coating pigmented with silanzied trianiline-intercalated graphene. Carbon 2019, 142, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Synthesis mechanism of FGE and AT.

Figure 1.

Synthesis mechanism of FGE and AT.

Figure 2.

Synthesis mechanism of TFAT.

Figure 2.

Synthesis mechanism of TFAT.

Figure 3.

Illustration of utilizing Diels–Alder reaction to synthesize the covalently bonded and reversibly cross-linked nanocomposites.

Figure 3.

Illustration of utilizing Diels–Alder reaction to synthesize the covalently bonded and reversibly cross-linked nanocomposites.

Figure 4.

Infrared spectrum of FGE, AT and TFAF.

Figure 4.

Infrared spectrum of FGE, AT and TFAF.

Figure 5.

1H NMR spectra of (a) FGE, (b) AT ,and (c) TFAT.

Figure 5.

1H NMR spectra of (a) FGE, (b) AT ,and (c) TFAT.

Figure 6.

Dispersion state of graphene after TFAT modification in dissolution.

Figure 6.

Dispersion state of graphene after TFAT modification in dissolution.

Figure 7.

TEM photos of graphene before and after modification (a) unmodified graphene, (b) TFAT-modified graphene.

Figure 7.

TEM photos of graphene before and after modification (a) unmodified graphene, (b) TFAT-modified graphene.

Figure 8.

Graphene/epoxy Raman photo (a) unmodified graphene, (b) TFAF modified graphene.

Figure 8.

Graphene/epoxy Raman photo (a) unmodified graphene, (b) TFAF modified graphene.

Figure 9.

DSC curve of Epoxy/TFAF-G nanocomposites.

Figure 9.

DSC curve of Epoxy/TFAF-G nanocomposites.

Figure 10.

Stress-strain curve of TFAT-G/resin nanocomposites.

Figure 10.

Stress-strain curve of TFAT-G/resin nanocomposites.

Figure 11.

Conductive properties of resin nanocomposites with distinctive wt% of TFAF-G modified (a) surface resistance, (b) surface resistivity, (c) volume resistivity.

Figure 11.

Conductive properties of resin nanocomposites with distinctive wt% of TFAF-G modified (a) surface resistance, (b) surface resistivity, (c) volume resistivity.

Figure 12.

SEM pictures of TFAT-G/Resin Nanocomposite (a) neat resin, (b) neat resin after 1 repair cycle, (c) resin with 1 wt% TFAT-G, (d) resin with 1wt% TFAT-G after 1 repair cycle.

Figure 12.

SEM pictures of TFAT-G/Resin Nanocomposite (a) neat resin, (b) neat resin after 1 repair cycle, (c) resin with 1 wt% TFAT-G, (d) resin with 1wt% TFAT-G after 1 repair cycle.

Figure 13.

Stress-strain curve of TFAT-G/resin nanocomposites before and after one repair cycle.

Figure 13.

Stress-strain curve of TFAT-G/resin nanocomposites before and after one repair cycle.

Figure 14.

Resistivity of neat resin and 1 wt% TFAF-G composites before and after one repair cycle:(a) Surface resistance, (b) Surface resistivity, (c) Volume resistivity.

Figure 14.

Resistivity of neat resin and 1 wt% TFAF-G composites before and after one repair cycle:(a) Surface resistance, (b) Surface resistivity, (c) Volume resistivity.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).