1. Introduction

Epoxy resin-based carbon fiber-reinforced composites (CFRCs) are widely used in many important industrial fields such as aeronautics and astronautics, racing cars, sports apparatus and transport tools [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6] owing to their excellent thermal and mechanical stability, low coefficient of thermal expansion and good corrosion resistance. Nevertheless, the insolubility and infusibility nature of the thermosetting epoxy resins [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] results in touchy problems associated with the after-treatment of the discarded CFRC products and the recovery of the expensive carbon fibers [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. In the current disposal of CFRCs, they are often considered as non-recyclable and eventually treated by landfill and incineration, which inevitably bring serious second pollution to air and ground.

A variety of methods of recycling the waste CFRCs have been studied in the past years. In Schinner’s report, the composites were ground in a cutting mill, and the resulting grinds were reused as press-molding compounds to produce laminates [

20]. Pickering and coworkers treated fiber-reinforced thermosetting composites through fuidised bed combustion process at a bed temperature of 450

oC and the fibers with mean lengths of up to 5 mm could be recovered [

21]. Giorgini L recovered CFs by thermal pyrolysis of CFRCs at a high temperature up to 600 °C [

22]. Although the CFs can be recovered by the above-mentioned processes, most of them obtained have been seriously damaged and lost their original performance. For instance, the tensile strength of recovered fibers by fuidised bed process was reduced by up to 50% [

21].

In order to simplify the recovery process and reduce the energy-cost, the fabrication of CFRCs with an epoxy resin matrix that is capable of chemical or thermal degradation at a lower temperature is favorable. In this way, the CFs are readily recovered under a mild condition and can maintain the original performance to a large extent. To this end, various degradable epoxy resins have been synthesized by introducing chemical or thermal labile bonds into the epoxy molecules such as phosphate, phosphite, sulfite, tertiary carbon-ether and tertiary carbon-ether linkages [

12,

13,

14,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

Relative to thermal pyrolysis, the chemical degradation of epoxy resins is more energy-saving since it is carried out at a much lower temperature. Recently, Yu et al. developed a recyclable epoxy-based CFRP composite where the thermosetting epoxy resin was able to dissolve in alcohol solvents by transesterification reactions at 160–180 °C. While further heating, the polymer solution could repolymerize to reform the thermoset [

15,

16].Yamaguchi et al. prepared cresol novolak-type epoxy resin containing degradable acetal linkages, from which the obtained carbon fiber-reinforced plastics could breakdown through the treatment of hydrochloric acid at room temperature to regenerate carbon fibers [

19]. Takahashi A et al. reported chemical degradable epoxy resins through the introduction of disulfide linkages, which degraded into completely soluble fragments via disulfide exchange reaction in the presence of base [

11]. Shirai et al. synthesized a series of epoxies containing thermally cleavable sulfonate ester groups. These cross-linked polymers could become soluble in organic solvents or water after heating at 120–200 °C [

29]. Another approach is to introduce dynamic reversible covalent bonds such as imine or Diels-Alder adducts into the network that de-crosslink at an elevated temperature [

30,

31,

32].

It is worthy to point out that, to ensure a sufficient service stability, the cured products of degradable epoxy resins are required to be well resistant to modestly high temperature, organic solvents, weak basic and acidic environment for a period of time. Meanwhile, in the event of necessity, the epoxy crosslinking network can collapse rapidly under a controlled condition to allow the recovery of expensive carbon fibers from the discarded CFRC materials.

Based on the above consideration, the present work was undertaken to design and synthesize semi-cycloaliphatic epoxy resin (H-ER) with one phenyl and two epoxycyclohexyl groups linked through acetal bonds. Acetal bond is well known to be stable to bases, oxidizing and reducing agents, but not to acids [

33,

34]. However, the sensibility of acetal to acid depends on the steric hindrance and electronic effects of substituents, and the presence of large groups adjacent to acetal bond is advantageous for its resistance to acids [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. In this work, since the acetal bond in the H-ER molecule is encapsulated with bulky cycloaliphatic and phenyl groups, the cured H-ER network is therefore expected to possess sufficient stability in weak acidic environment, but is hoped to be cleaved when the acidity of solution reaches a certain degree. On the other hand, the introduction of phenyl group in cycloaliphatic epoxy resins can improve the thermal stability and mechanical properties, while cycloaliphatic epoxy resins usually display excellent processability due to their low viscosity prior to curing. [

41,

42]. These merits are especially favorable as matrixes for CFRCs. The synthesis and properties of acetal-containing cycloaliphatic H-ER and the derived H-ER/CFs composite materials as well as the recovery and reusability of CFs were studied in detail.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Cyclohex-3-enyl-1-methanol and OXONE (a monopersulfate compound: 2KHSO4·KHSO4·K2SO4) were purchased from Shanghai Regent Company and used without further purification. Commercial epoxy resin ERL-4221 (3, 4-epoxycyclohexylmethyl-3′, 4′-epoxycyclohexane carboxylate) was obtained from Xinjin Chemicals Company. Hexahydro-4-methylphthalic anhydride (HMPA) and 2-ethyl-4-methyl-imidazole (EMI) were used as a curing agent and curing accelerator, respectively. Other chemical regents including acetic acid (ACA), oxalic acid (OXA), p-toluene sulfonic acid (p-TSA) and methanesulfonic acid (MSA) were of reagent grade and used as received. Plain weave CF clothes (T300) were purchased from Jiangsu Hengshen Fiber Materials Company.

2.2. Synthesis of 1-(bis(cyclohex-3-enylmethoxy)methyl)benzene (H-OL)

Cyclohex-3-enyl-1-methanol (42 g, 375 mmol), benzaldehyde (13.265 g, 125 mmol) and p-TSA (2.375 g, 12.5 mmol), anhydrous n-hexane (187.5 mL) and 5 Å molecule sieve (25 g) were charged into a 500 mL three-necked flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer and a thermometer. The mixture was reacted at -8 oC for 6 h. After filtration, the filtrate was treated with 15% of NaOH aqueous solution (3 × 50 mL) and deionized water (3 × 50 mL). The organic phase was dried with anhydrous MgSO4 overnight and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified by vacuum distillation and finally afforded 20.78 g H-OL as a colorless liquid. Yield: 53%. FTIR (KBr): 3089 (s), 3022 (s), 2915 (s) and 2836 (s), 1652 (s), 1494 (s), 1110 (s) 1051(s) and 1027 (s). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 7.47 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.36 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H, ArH) and 7.31 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H, ArH), 5.67 (s, 4H, CH), 5.54 (s, 1H, CH).

2.3. Synthesis of 1-bis(3,4-epoxycyclohexylmethyl) benzene (H-ER)

H-OL (9.37 g, 30 mmol), dichloromethane (90 mL), acetone (90 mL) and 18-crown-6 ether (0.9 g, 3 mmol) were added in a 1000 mL four-necked flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer and two dropping funnels. The resulting mixture was vigorously stirred at -15 oC. Then the solution of OXONE (45.0 g, 75 mmol) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (0.06 g, 0.2 mmol) in 240 mL deionized water was added into the mixture while the pH value was maintained between 7.4 and 7.9. The reaction mixture was stirred at -15 oC for 7 h. Then the organic phase was isolated, washed with deionized water, and dried over anhydrous MgSO4. After filtration and concentration, the product was purified by vacuum distillation and finally obtained 8.85 g H-ER as a colorless liquid. Yield: 86%. FTIR (KBr): 3091 (s), 2985 (s), 2923 (s) and 2863 (s), 1494 (s), 1114 (s), 1045 (s), 808 (s). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 7.41(d, J = 8 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.35(d, J = 4 Hz, 2H, ArH) and 7.31 (d, J = 12 Hz, 1H, ArH), 5.46 (s, J = 6Hz, 1H, CH), 3.23–3.29, (d, J = 8Hz, 4H, CH). 13C NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, δ): 126–138 (Ar), 101 (–CH–O), 69 (–CH2–O), 51–52 (C–H on epoxide ring), 21–33 (cycloaliph, –CH2–, –CH–). ESI-MS m/z: [M + Na]+ calcd for C21H28O4Na, 367.4482; found, 367.1868.

2.4. Curing of H-ER Epoxy Resin

H-ER was mixed with HMPA at a stoichiometric ratio of 1: 0.95 at room temperature. Then 0.5 wt% of EMI was added to the mixture as a curing accelerator. After being defoamed in vacuum condition, the mixture was cured at 100 oC for 2 h, 170 oC for 2 h, and 200 oC for 2h. For comparison, the commercial epoxy resin ERL-4221 was cured under the same curing condition.

2.5. Preparation of H-ER-Based CF-Reinforced Composite Materials

Six pieces of CF cloth with dimension of 150 × 100 mm2 were soaked in acetone for 48 h to clean the surface, and then dried at 80 oC for 6 h. The well defoamed epoxy glue with the same composition as that described in the curing of epoxy resin was spread evenly on each layer of fiber cloths, and the impregnated fiber clothes were heated in an oven at 50 °C for 6 h for pre-curing. Finally, the laminated carbon fiber clothes impregnated with pre-cured H-ER glue were transferred to a plate vulcanizer, and pressed under 1 MPa at 100 oC for 2 h, 170 oC for 2 h, and 200 oC for 2h.

2.6. Degradation of the Cured Epoxy Resin

Degradation experiments of the cured H-ER with dimension of 10 × 10 × 3 mm3 were conducted in 0.5 N MSA/THF/H2O, 0.5 N p-TSA/THF/H2O, 2.0 N OXA/THF/H2O and 2.0 N ACA/THF/H2O. In each case, the volume ratio of THF to H2O is 4: 1. At refluxing temperature, the residual weight percentages of samples at different time were recorded.

2.7. Degradation of CFRCs and Recovery of Carbon Fiber Clothes

Degradation of the H-ER based CFRCs was carried out in 0.5 N p-TSA in a THF/water (4/1 v/v) solvent for 6 h at refluxing temperature. The recovered carbon fiber clothes were washed with THF and acetone followed by drying under reduced pressure at room temperature.

2.8. Instrumentation

Fourier-transform infrared spectra (FTIR) were recorded on a Nicolet 5700 spectrometer. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were measured on an INOVA-400 NMR spectrometer (Varian) in CDCl3 using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard. Electrospray mass spectrum (ESI-MS) was obtained on an Agilent 6310 quadruple LC/MS for electrospray ionization in positive and negative modes. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) measurements were determined on an Agilent 7000B triple quadrupole GC/MS. Dynamic viscoelasticity spectra were measured on an apparatus (TA DMA Q800) at a heating rate of 2 oC min-1 and at a frequency of 1 Hz under nitrogen atmosphere in the linear viscoelastic range. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed with a NETZSCH TG 209 thermal analyzer from 25 to 800 oC at a heating rate of 10 oC min-1 and a nitrogen gas flow rate of 60 mL min-1. SEM was performed on a QUANTA 450 scanning electron microscopy at 20.0 kV accelerating voltage. Before the test, the samples were sprayed with a thin gold layer of 0.5 mm to increase its conductivity. The fracture performance was tested in the same way as the three-point bending according to GB 4161-2007. Every group of five samples were measured at 25 oC, and their average values were calculated. Critical stress intensity factor (KIC) was calculated from the equation: KIC = PCS/BW3/2·f (a/w). Shearing strength tests were performed on INSTRON-5567A according to the standard of ISO 4587-1979. The flexural performance was tested on a universal testing machine (Instron 5565) with a loading rate of 2mm/min on the sample rack with a span of 64 mm according to GB/T 9331-2008. The flexural strength (σf), flexural modulus (Ef) and strain at break (εf) were calculated from the equation: σf = 3FL/2bh2, Ef = L3k/4bh3 and εf = 6hs/L2.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of Acetal-Containing Cyloaliphatic Epoxy Resin (H-ER)

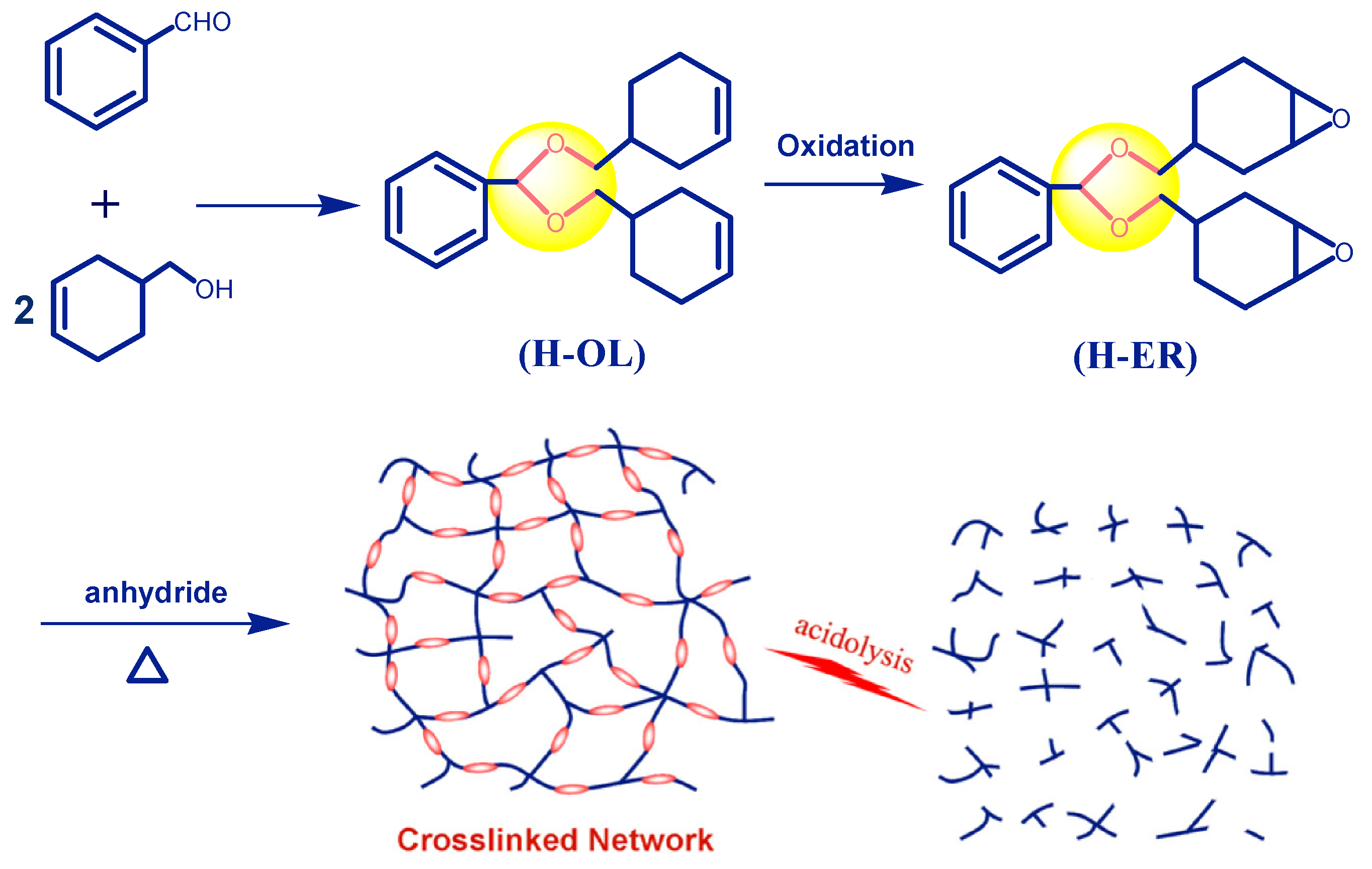

Using benzaldehyde and cyclohex-3-enyl-1-methanol as starting materials, the semi-cycloaliphatic diene precursor (H-OL) was prepared by acetalization reaction. Then the epoxy resin H-ER with two epoxycyclohexyl groups linked with phenyl through acetal bonds was obtained through the oxidation reaction of H-OL with OXONE in the presence of ethylenediamineretraacetic catalyst (

Scheme 1). Compared with the furfural-based epoxy resin [

43], the replacement of benzaldehyde with furfural can bring about two merits. Benzaldehyde is a cheaper and conveniently available raw material and therefore is more favorable from the viewpoint of future practical production and application. Moreover, the introduction of rigid benzene ring in the cross-linked network is expected to significantly improve the thermal and mechanical properties of the product, which are indeed demonstrated by the measured results as discussed in

Section 3.2.

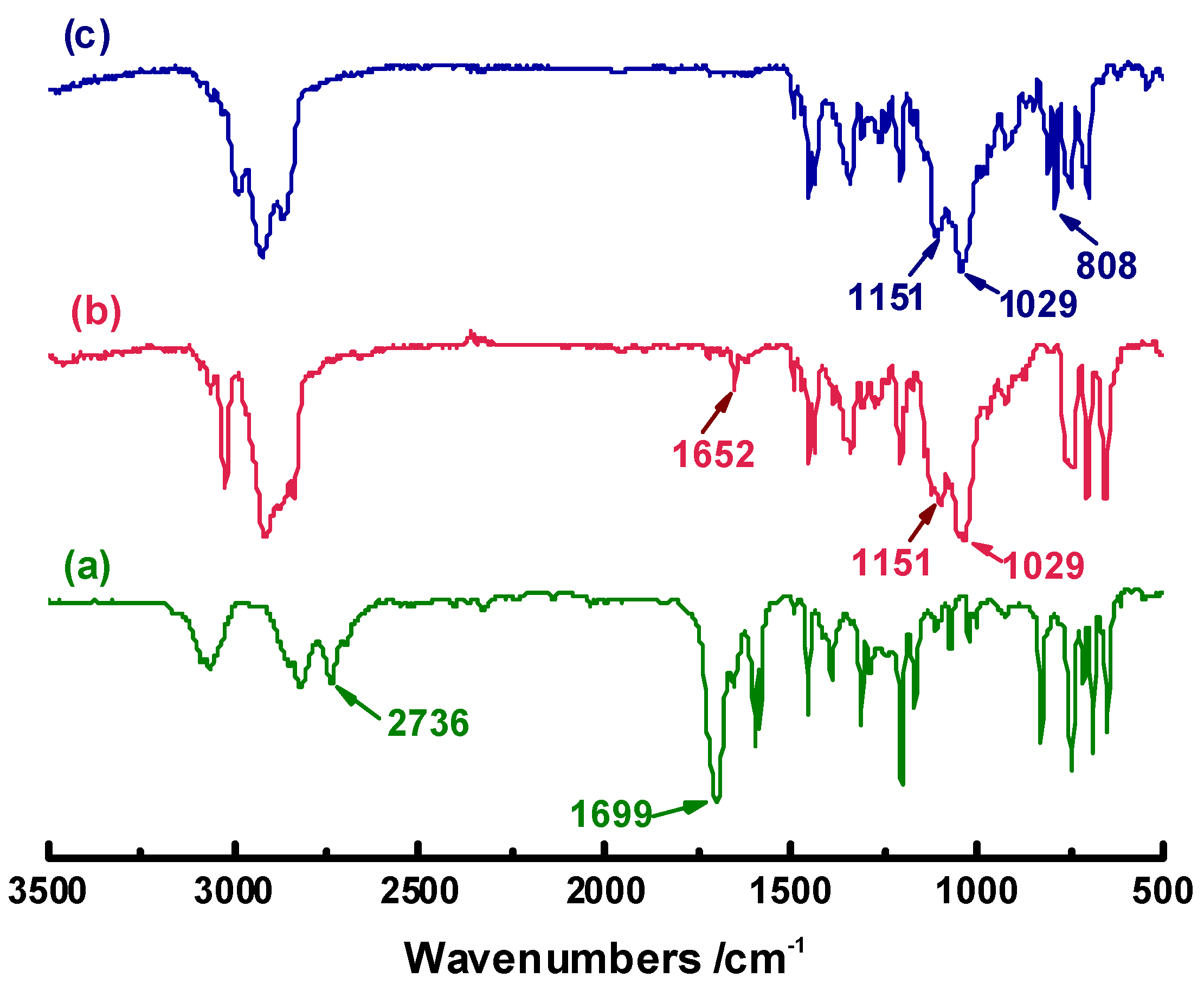

In the FTIR spectra (

Figure 1), the bands at 1029 and 1151 cm

-1 are assigned to the acetal –C–O–C–O–C– in the diene precursor H-OL, whereas the absorptions at 1699 cm

-1 and 2736 cm

-1 corresponding to the aldehyde group of benzaldehyde disappear, demonstrating that the reaction between benzaldehyde and commercial cyclohex-3-enyl-1-methanol is complete. Subsequently, the successful conversion of –C=C– double bond to epoxy group is confirmed by the newly emerged band at 808 cm

-1 and the disappearance of –C=C– band at 1652 cm

-1. In the

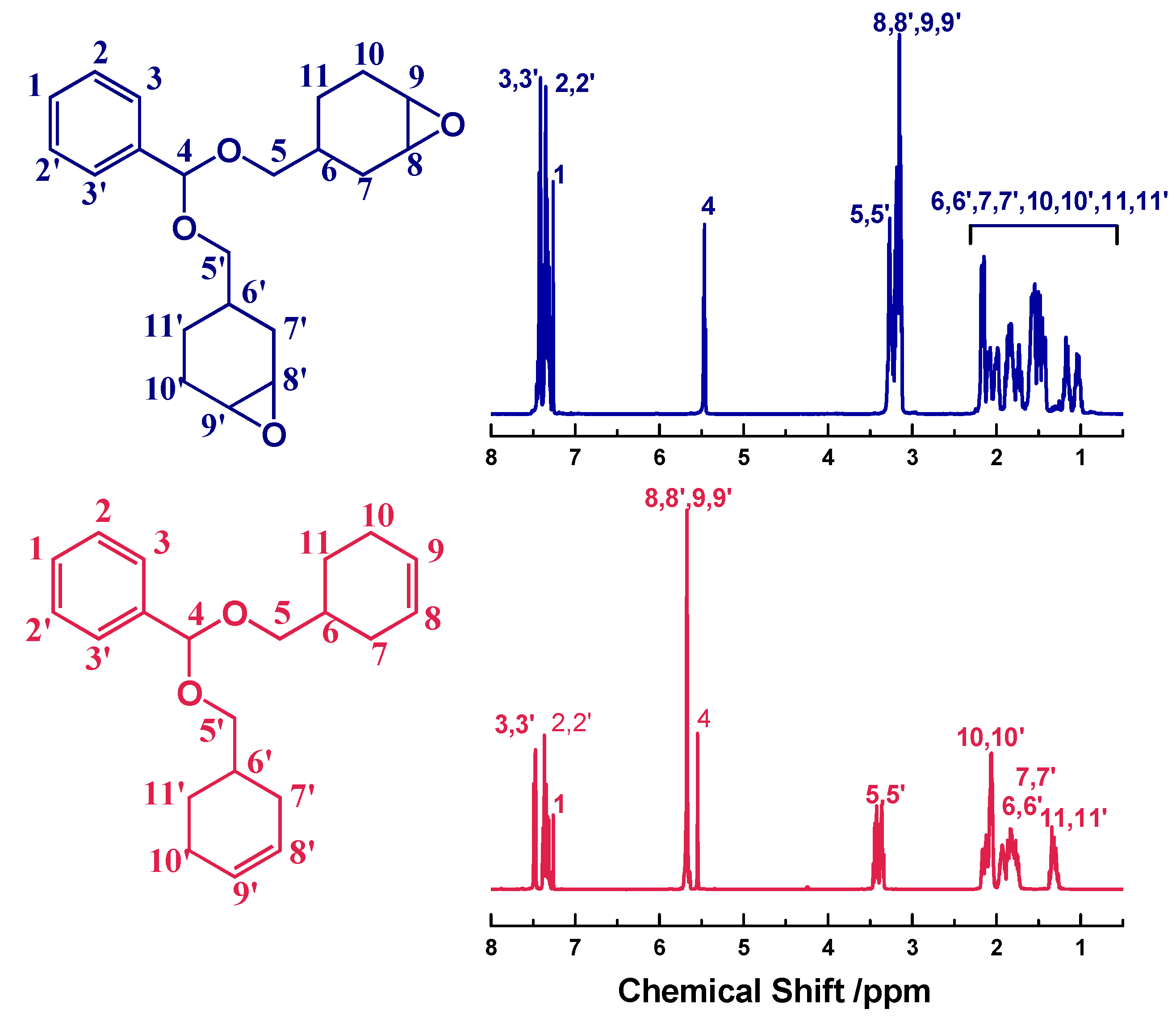

1H NMR spectra (

Figure 2), the protons in benzene ring locate at 7.47, 7.37 and 7.31 ppm, while the signals of –CH– and –CH

2– in cyclohexenyl rings are at 1.29–2.17 ppm. The protons in epoxide rings appear at 3.12–3.19 ppm. In the

13C NMR spectra (Figure S1), the carbons on benzene and epoxide rings are found at 126–138 ppm and 51–52 ppm, respectively. The other carbons of cycloaliphatic CH or CH

2 groups appear at 21–33 ppm. The ESI-MS spectrum (Figure S2) of H-ER shows that the found molecular ion peak of M + Na

+ (367.1868) is consistent with the theoretical value calculated according to the formula C

21H

28O

4Na (367.4404 g/mol).

3.2. Thermal and Mechanical Properties of the Cured Epoxy Resin H-ER

Figure S3 shows the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) trace of the cured H-ER measured under nitrogen atmosphere at a heating rate of 10

oC /min. Its 2% weight-loss temperature is 324 °C and the temperature at the maximum weight-loss rate is 378

oC, exceeding the values of the widely used commercial cycloaliphatic resin ERL-4221 (316 °C and 368 °C) [

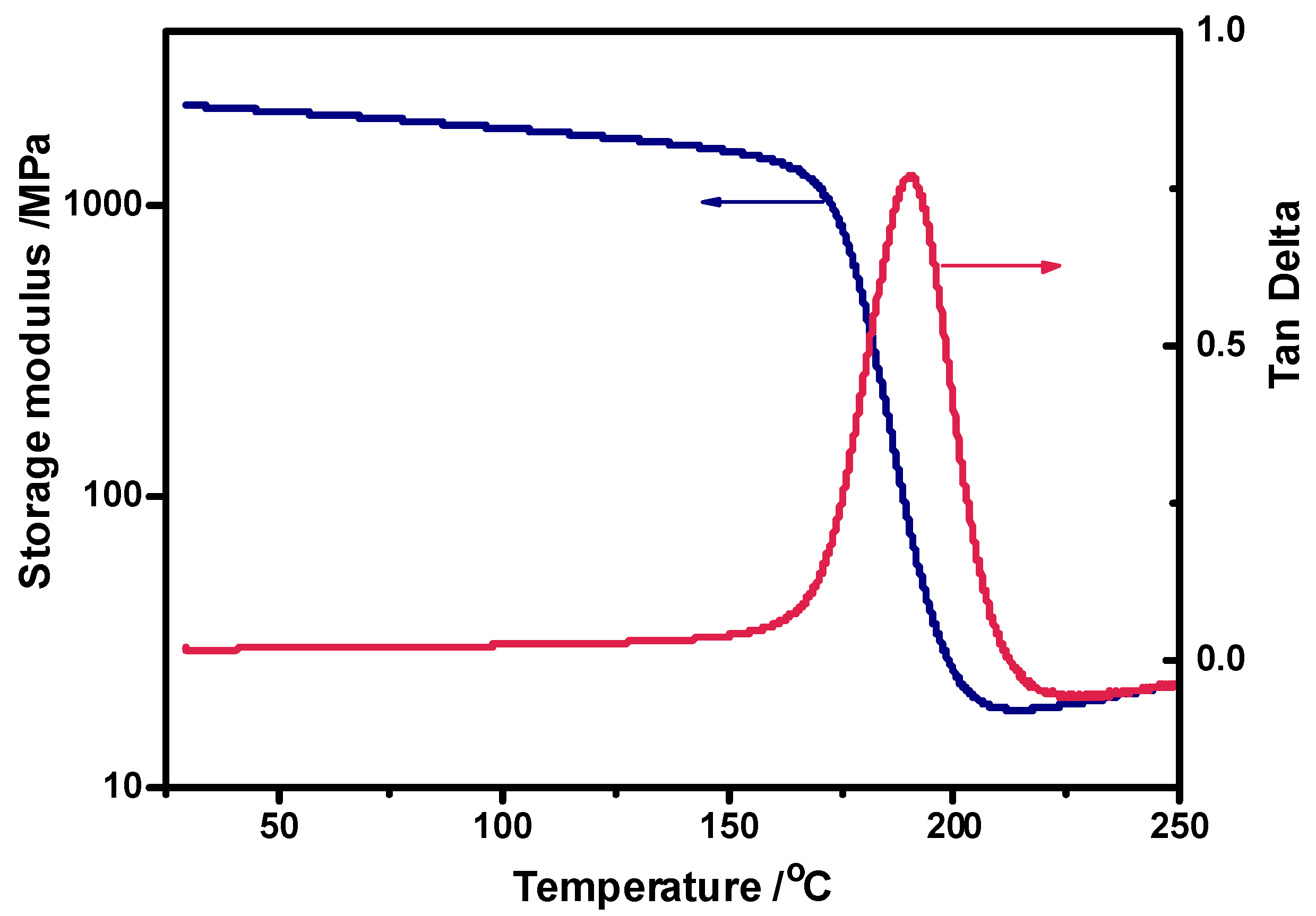

13], respectively. The excellent thermal stability ensures the durability for the H-ER-based CFRCs. In addition, the dynamic viscoelasticity of the cured H-ER was studied (

Figure 3). According to the rubber elasticity theory, its cross-linking density (ρ) was calculated from the storage modulus in the rubbery region in term of equation: ρ = E′/3RT [

44], where E′ is the storage modulus at T

g + 50 °C, R is the gas constant and T is the absolute temperature. The ρ value of the cured H-ER is 1.65 × 10

-3 mol/cm

3, much higher than that of the cured ERL-4221 (0.94 × 10

-3 mol/cm

3) [

13], which can explain why the T

g value of H-ER (194 °C) is slightly higher than that of ERL-4221 (191 °C) [

13] even though there exit flexible C–O–C–O–C acetal linkages in H-ER network. Besides, the presence of rigid benzene ring in the cured H-ER also results in increased glass transition temperature in comparison with the furfural-based epoxy resin (186

oC) [

43] measured under the same conditioned

According to the standard of ISO 4587-1979, the shearing strength of the cured H-ER was measured. The shearing strength of the cured H-ER is 7.45 MPa, which is remarkably superior to the commercial cycloaliphatic epoxy resin ERL-4221 (3.29 MPa) [

14] and the furfural-based epoxy resin (4.70 MPa) [

44], probably owing to the higher cross-linking density or the increased rigidity of the wholly aromatic H-ER. Moreover, the higher cross-linking density of H-ER also positively contributes to the mechanical toughness of the cured H-ER.

Table 1 shows that the flexural modulus (E

f) of the cured H-ER are comparable to those of ERL-4221, while the flexural strength (σ

f), strain at break (ε

f) and critical stress intensity factor (K

IC) are 53.34 MPa, 7.42% and 1.673 MN/M

3/2, increased by 26.5%, 17.0% and 29.5% compared to the values of ERL-4221, respectively. The excellent adhesion strength and mechanical toughness of H-ER is especially important as resin matrix for the CF-reinforced epoxy resin composites.

3.3. Chemical Degradation Behavior of the Cured Epoxy Resin H-ER

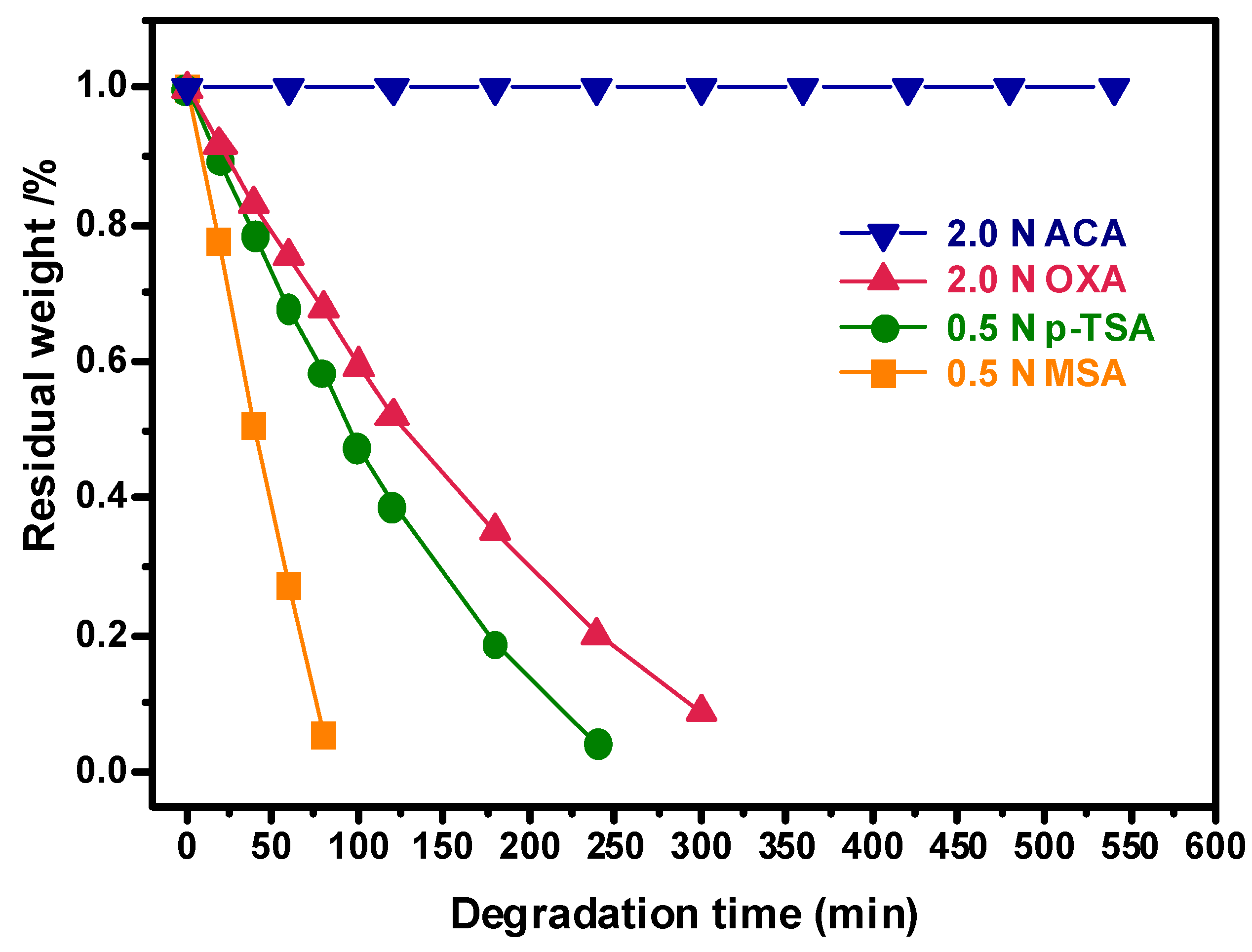

The resultant cured H-ER is completely insoluble in common organic solvents such as acetone, chloroform, tetrahydrofuran, dimethyl sulfoxide and N,N-dimethylformamide as well as 1 N aqueous sodium hydroxide and sodium carbonate solution for 24 h at room temperature. Surprisingly, as shown in

Figure 4, the sample did not exhibit degradation in 2 N acetic acid/THF/H

2O solution even though being treated at the refluxing temperature for 550 min, implying that the cured H-ER is sufficient stable under the harsh service condition such as being exposed to organic solvents, basic and weak acidic environment for a period of time.

Furthermore, the degradation of the cured H-ER was evaluated by treating the samples in the aqueous acidic solutions with the enhanced acidity such as oxalic acid (OXA),

p-toluene sulfonic acid (

p-TSA) and methanesulfonic acid (MSA). After changing ACA with OXA, the sample rapidly degraded, and the degradation rate apparently accelerated with the increased acidity in the ranking sequence of MSA >

p-TSA > OXA (

Figure 4). For example, the cured H-ER lost about 73% weight after immersing in the aqueous solution of MSA for only 60 min.

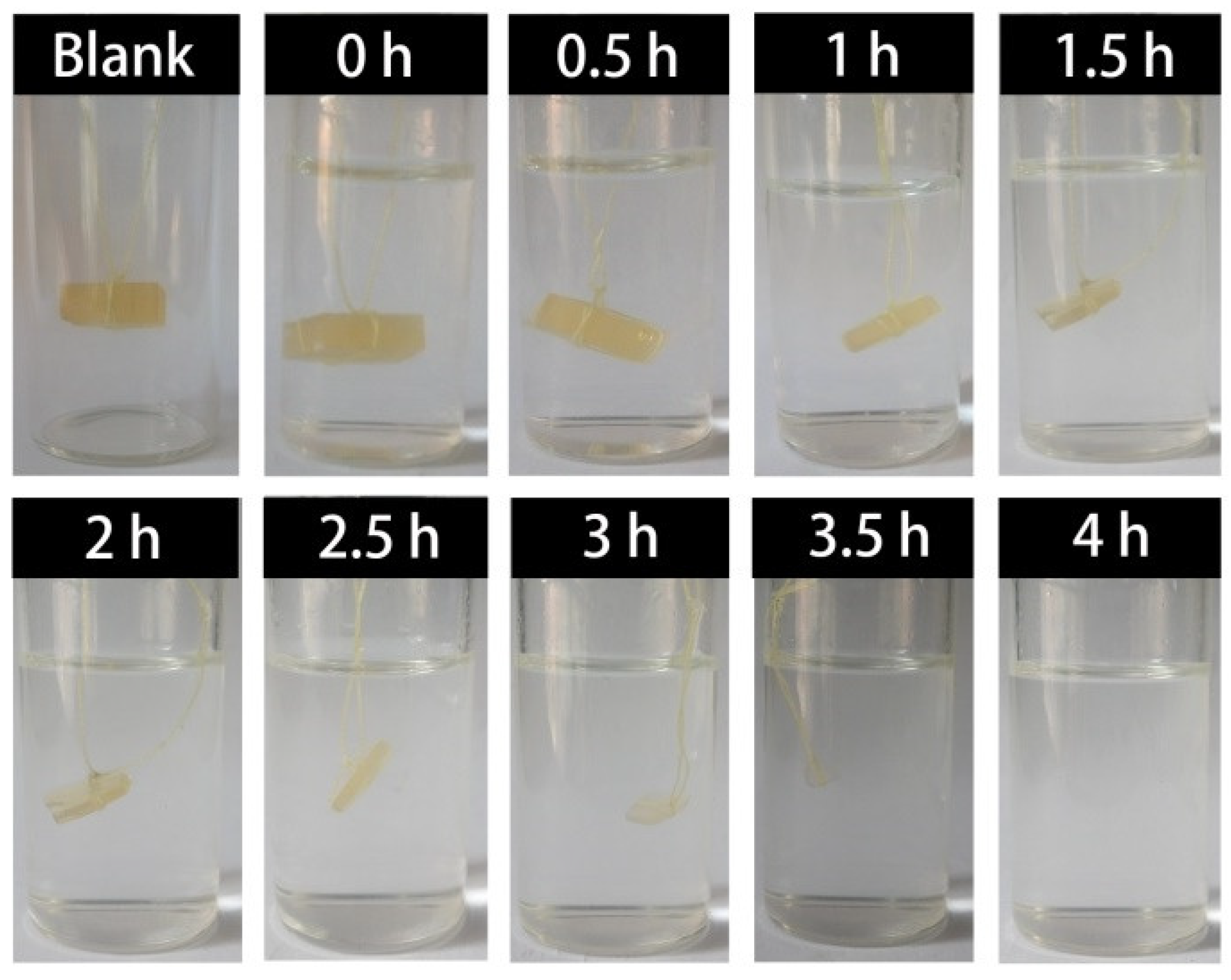

The degradation process of the cured H-ER was examined by visibly observing the change of the sample in 0.5 N MSA/THF/H

2O solution, and the photographs are illustrated in

Figure 5. The original size of the sheet sample is 12 mm in length, 10 mm in width and 4 mm in thickness. It was seen that the sample remarkably shrinked after acid-treatment for 1 h, and the degradation was very rapid in the time interval of 1 to 3 h. The sample completely disappeared after acid-treatment for 4 h.

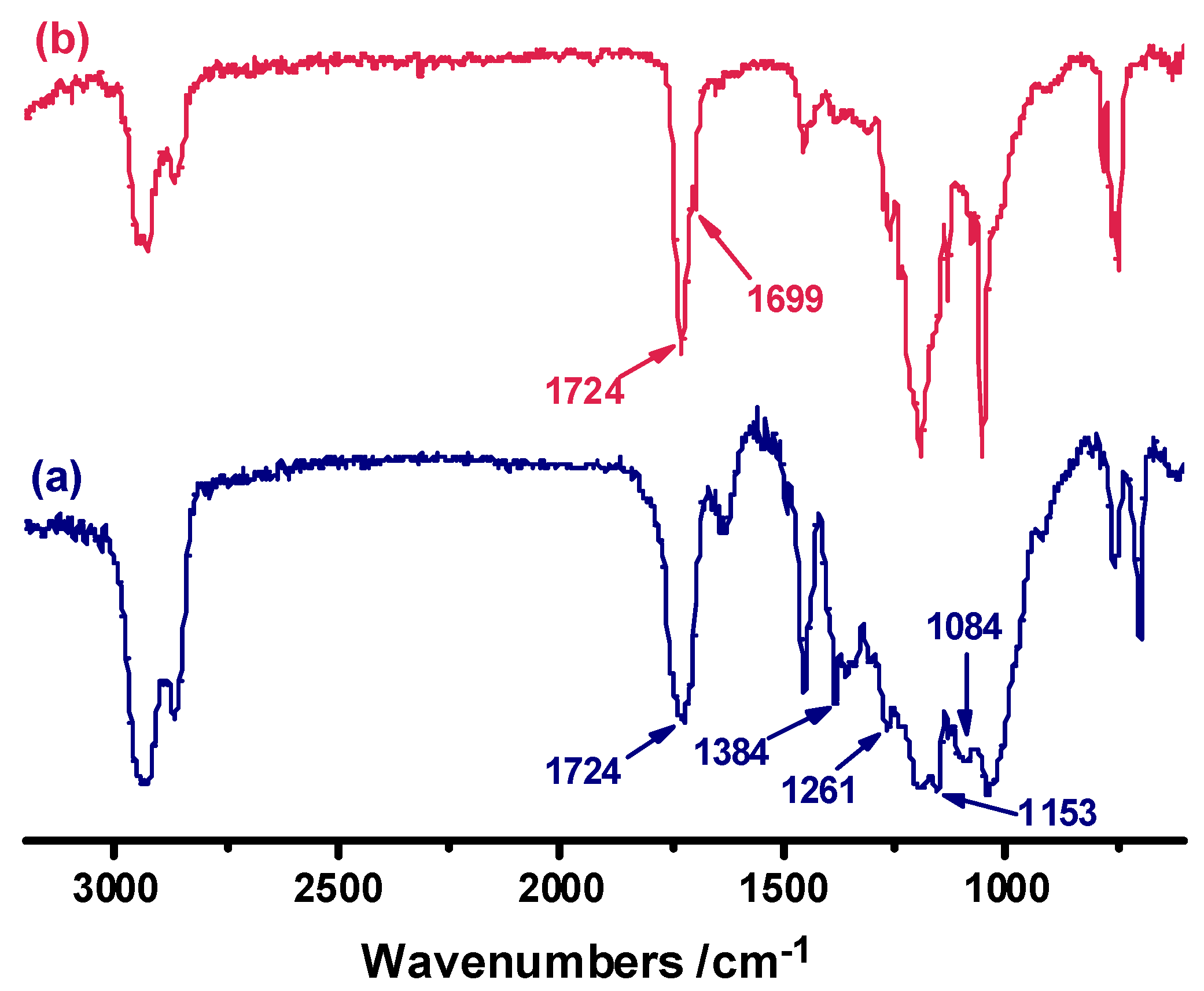

The degradation mechanism was investigated by analyzing the FTIR spectra of the cured H-ER before and after acid-treatment. As shown in

Figure 6, after acid-treatment, the adsorption at 1724 cm

-1 of the ester bond derived from the curing of H-ER with hexahydro-4-methylphthalic anhydride is almost unchanged. However, a shoulder peak at 1699 cm

-1 appears which is attributed to the stretching vibration of carbonyl in aldehyde group. Moreover, the intensities of acetal linkage C–O–C–O–C at around 1010-1250 cm

-1 apparently decrease although its characteristic bands are overlapped with C-O linkage of ester group, demonstrating that the acidolysis results from the cleavage of acetal rather than ester linkages in the network.

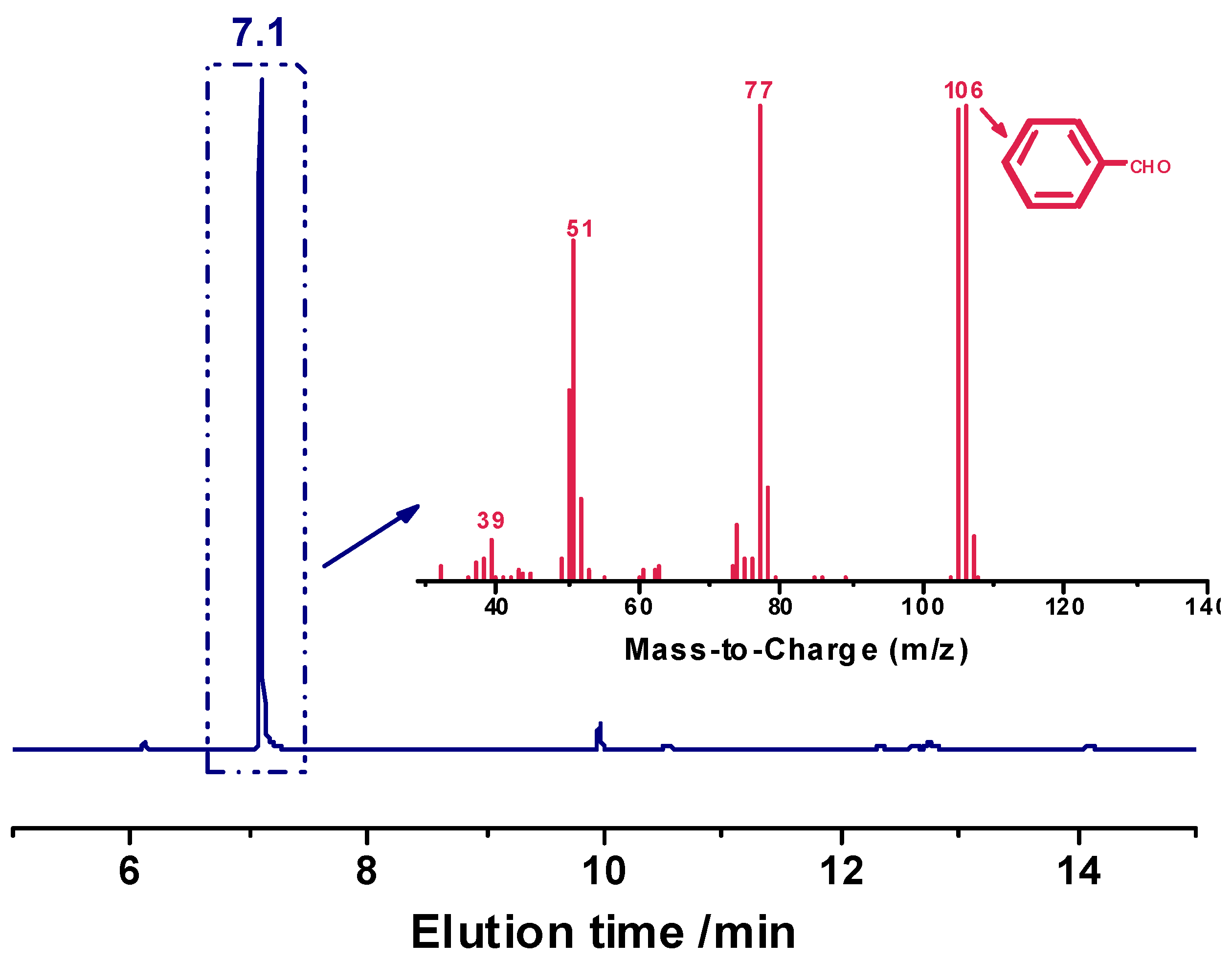

The degradation of the acetal-linked epoxy resin network was further examined by the analysis of the acid-degraded solution by means of gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy (GC/MS).

Figure 7 displays that the strong peak at the elution time of 7 min in the GC spectrum is assigned to benzaldehyde since its molecular ion peak (106) is consistent with the molecular weight of benzaldehyde (106 g/mol), which also supports that the degradation of the cured epoxy resin is indeed due to the cleavage of acetal bonds. Moreover, the degradation-generated benzaldehyde may be reused as the starting raw material for the synthesis of the H-ER resin.

3.4. Recycling of Carbon Fibers From the h-er-Based CFRCs

The recovery of carbon fibers from the CFRCs composite was carried out by treating the composite with 0.5 N MSA/THF/H

2O solution at the refluxing temperature for 30 min. The laminated CFRC composites were prepared from CF cloth and H-ER epoxy resin cured with anhydride. The sample size is 30 × 30 × 2 mm

3.

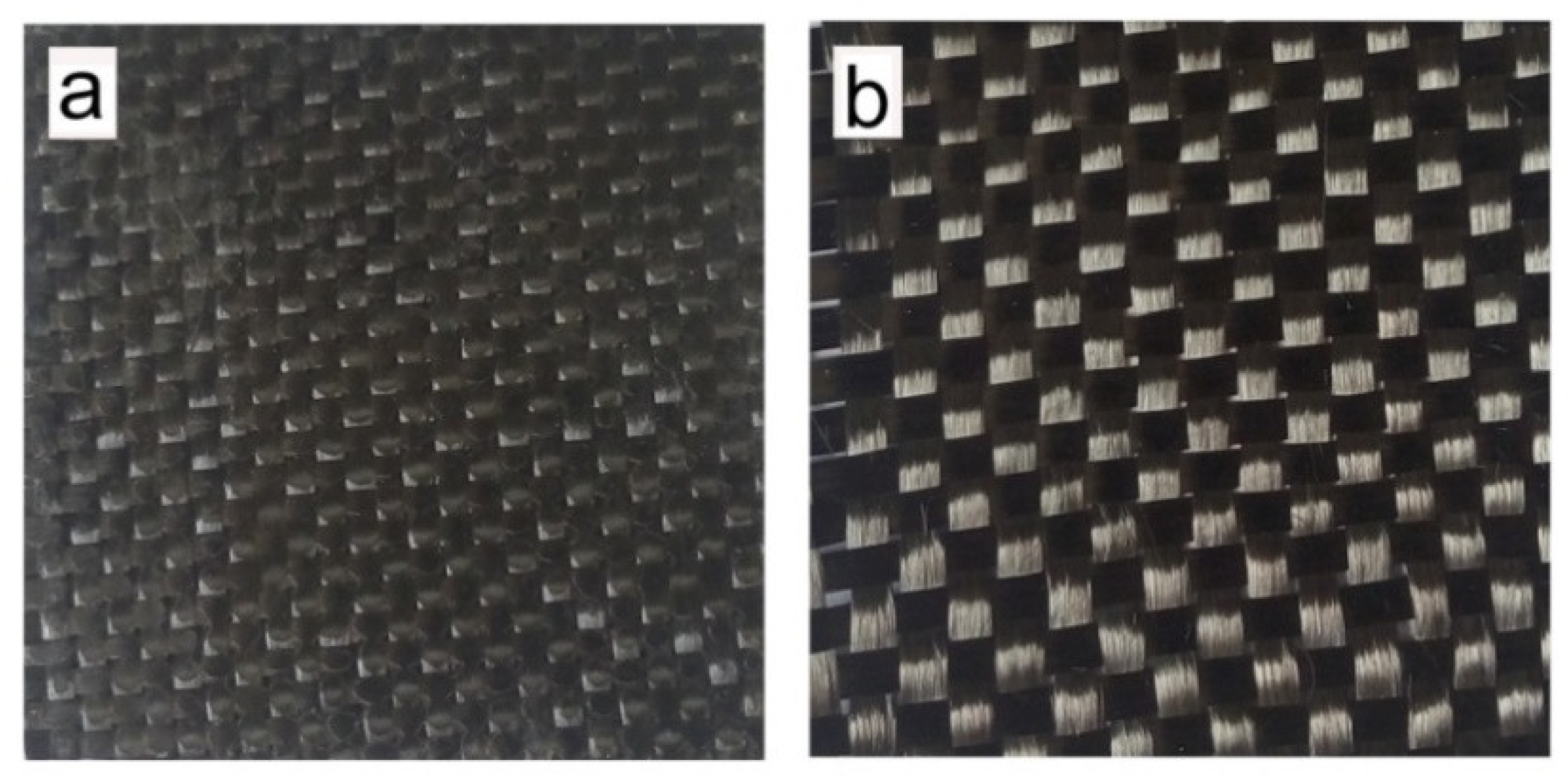

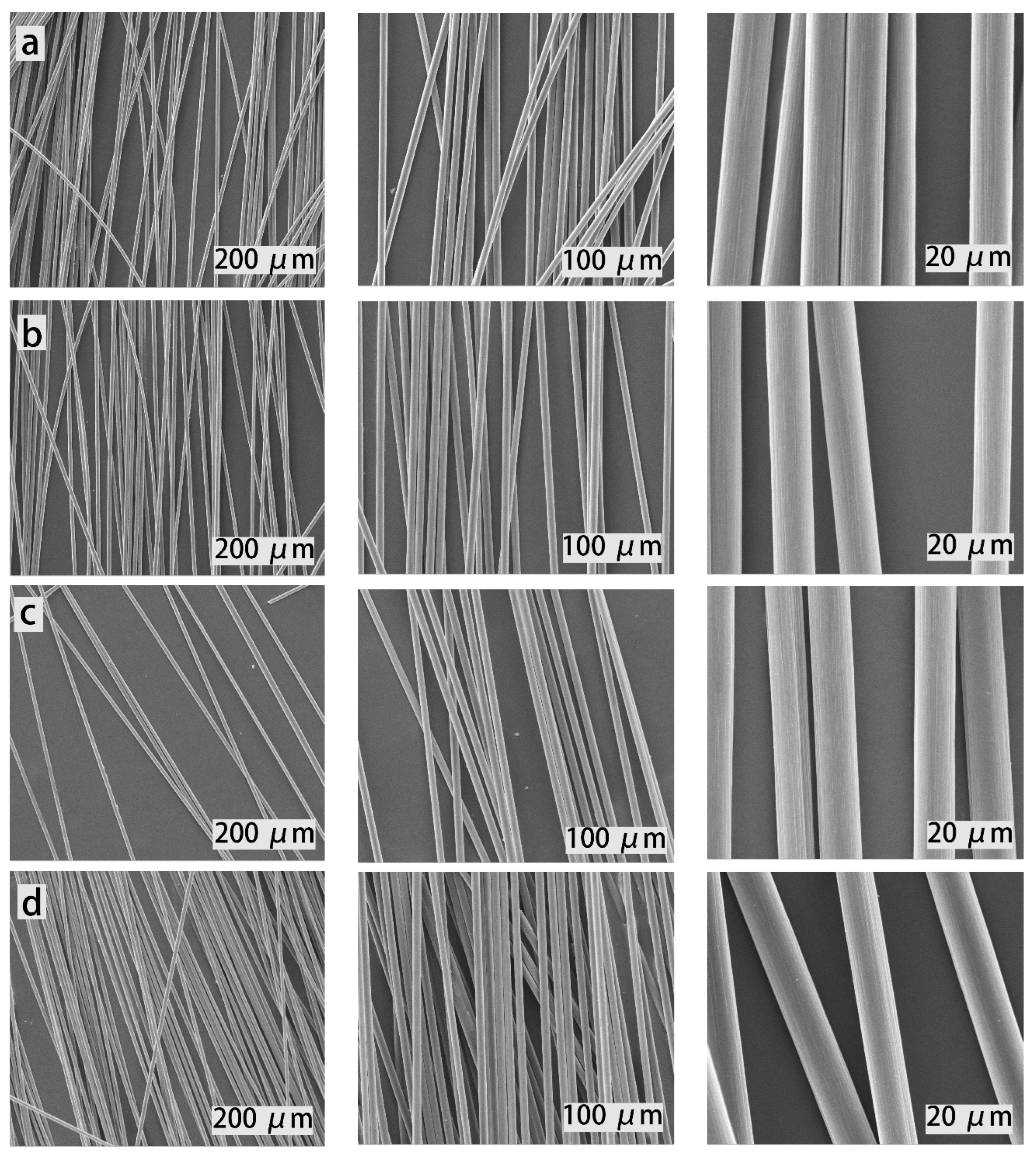

Figure 8 shows the photographs of CFRC samples with and without acidolysis. It is seen that the acid-treated CF cloth well maintains its original texture. Furthermore, the recovered CF cloth was recycled three times for the CFRC fabrication. After acid-treatment with the same procedure, the recovered carbon fibers were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). As illustrated in

Figure 9, the acid-treatment can completely remove the epoxy resin matrix from the CFs, and the surfaces of the recovered fibers are almost the same as the original ones. No any residue of epoxy resin and damage are found on the surface of the recovered carbon fibers, implying that the recycling of CFs from the CFRCs composite using degradable H-ER epoxy resin as a matrix is feasible.

4. Conclusions

In summary, a new semi-cycloaliphatic epoxy resin containing acetal linkages (H-ER) was synthesized. The cured product exhibits excellent thermal and mechanical properties. Its Tg and initial decomposition temperatures are 194 °C and 324 °C, while the shearing and flexural strengths are 7.45 and 53.34 MPa, respectively, which exceed or are comparable to the values of the commercial epoxy resin ERL-4221. The cured H-ER is sufficiently stable in organic solvents, basic and weak acidic solutions, ensuring the service reliability in the working environment. Meanwhile, at the elevated acidity, for instance in aqueous methanesulfonic acid solution, the cured H-ER network can rapidly degrade due to the cleavage of acetal linkages, and the degradation rate is controllable by adjusting the acidity of solution. The peculiar degradation property enables the recovery of carbon fibers from the composite fabricated with acetal-containing H-ER matrix resin. The results show that, after acid-treatment in aqueous acidic solution, the carbon fiber cloths are completely recoverable, and the recovered carbon fiber cloths could well maintain the original texture without detectable damage on the surface. Moreover, the regenerated CFs can be repeatedly used for the preparation of composite materials.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this article have been included as part of the Supplementary Information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, P.; Ma, S.; Wang, B.; Xu, X.; Feng, H.; Yu, Z.; Yu, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, J. Degradable benzyl cyclic acetal epoxy monomers with low viscosity: Synthesis, structure-property relationships, application in recyclable carbon fiber composite. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2022, 219, 109243. [CrossRef]

- De, B.; Bera, M.; Bhattacharjee, D.; Ray, B.C.; Mukherjee, S. A comprehensive review on fiber-reinforced polymer composites: Raw materials to applications, recycling, and waste management. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2024, 146, 101326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamar, N.T.; Drzal, L.T.; Lee, A.; Askeland, P. Nanoscale toughening of carbon fiber reinforced/epoxy polymer composites (CFRPs) using a triblock copolymer. Polymer 2017, 111, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Raman Pillai, S.K.; Che, J.; Chan-Park, M.B. High Interlaminar Shear Strength Enhancement of Carbon Fiber/Epoxy Composite through Fiber- and Matrix-Anchored Carbon Nanotube Networks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 8960–8966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Gao, X.; Jiang, J.; Xu, C.; Deng, C.; Wang, J. Comparison of carbon nanotubes and graphene oxide coated carbon fiber for improving the interfacial properties of carbon fiber/epoxy composites. Composites, Part B 2018, 132, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, E.; Liang, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Gao, C.; Wang, G.; Wei, Y.; Ji, Y. Chemical Recycling of Epoxy Thermosets: From Sources to Wastes. Ctuators, 2024, 13, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Chou, Y.C.; Shiao, W.F.; Wang, M.W. High temperature, flame-retardant, and transparent epoxy thermosets prepared from an acetovanillone-based hydroxyl poly(ether sulfone) and commercial epoxy resins. Polymer 2016, 97, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, P.; Li, Y.; Gu, X.; Han, D.; Jia, X.; Wang, M.; Zhou, T.; Wang, T. Novel phosphorus–nitrogen–silicon flame retardants and their application in cycloaliphatic epoxy systems. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 2977–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, S.; Speiser, M.; Schowner, R.; Giebel, E.; Buchmeiser, M.R. Air Stable and Latent Single-Component Curing of Epoxy/Anhydride Resins Catalyzed by Thermally Liberated N-Heterocyclic Carbenes. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 4548–4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, R.-Y.; Reddy, K.S.K.; Chen, Y.-C.; Wang, M.-W.; Chang, H.-C.; Abu-Omar, M.M.; Lin, C.H. Preparation and Degradation of Waste Polycarbonate-Derived Epoxy Thermosets and Composites. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, A.; Ohishi, T.; Goseki, R.; Otsuka, H. Degradable epoxy resins prepared from diepoxide monomer with dynamic covalent disulfide linkage. Polymer 2016, 82, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, Z. Synthesis of silicon-containing cycloaliphatic diepoxide from biomass-based α-terpineol and the decrosslinking behavior of cured network. Polymer 2017, 119, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Xiong, L.; Zhao, L. Phosphorus-containing liquid cycloaliphatic epoxy resins for reworkable environment-friendly electronic packaging materials. Polymer 2010, 51, 4776–4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Z. Synthesis of phosphite-type trifunctional cycloaliphatic epoxide and the decrosslinking behavior of its cured network. Polymer 2013, 54, 5182–5187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Shi, Q.; Dunn, M.L.; Wang, T.; Qi, H.J. Carbon Fiber Reinforced Thermoset Composite with Near 100% Recyclability. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 6098–6106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X.; Shi, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, T.; Qi, H.J. Dissolution of epoxy thermosets via mild alcoholysis: the mechanism and kinetics study. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 1493–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Ma, S.; Dai, J.; Jia, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhu, J. Hexahydro-s-triazine: A Trial for Acid-Degradable Epoxy Resins with High Performance. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 4683–4689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yan, S.; Zhao, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, X.; Jia, L. Multiply fully recyclable carbon fibre reinforced heat-resistant covalent thermosetting advanced composites. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, A.; Hashimoto, T.; Kakichi, Y.; Urushisaki, M.; Sakaguchi, T.; Kawabe, K.; Kondo, K.; Iyo, H. Recyclable carbon fiber-reinforced plastics (CFRP) containing degradable acetal linkages: Synthesis, properties, and chemical recycling. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2015, 53, 1052–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinner, G.; Brandt, J.; Richter, H.J.J.o.T.C.M. Recycling Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 1996, 9, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, S.J.; Kelly, R.M.; Kennerley, J.R.; Rudd, C.D.; Fenwick, N.J. A fluidised-bed process for the recovery of glass fibres from scrap thermoset composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2000, 60, 509–523. [CrossRef]

- Giorgini, L.; Benelli, T.; Mazzocchetti, L.; Leonardi, C.; Zattini, G.; Minak, G.; Dolcini, E.; Cavazzoni, M.; Montanari, I.; Tosi, C. Recovery of carbon fibers from cured and uncured carbon fiber reinforced composites wastes and their use as feedstock for a new composite production. Polym. Compos. 2015, 36, 1084–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Webster, D.C. Degradable thermosets based on labile bonds or linkages: A review. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2018, 76, 65–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez, R.; Fernández-Francos, X.; Salla, J.M.; Serra, A.; Mantecón, A.; Ramis, X. New degradable thermosets obtained by cationic copolymerization of DGEBA with an s(γ-butyrolactone). Polymer 2005, 46, 10637–10647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Chen, J.-S.; Körner, H.; Breiner, T.; Ober, C.K.; Poliks, M.D. Reworkable Epoxies: Thermosets with Thermally Cleavable Groups for Controlled Network Breakdown. Chem. Mater. 1998, 10, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, H.; Wong, C.P. Syntheses and characterizations of thermally reworkable epoxy resins II. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2000, 38, 3771–3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; Chen, Z. Synthesis and degradable property of novel sulfite-containing cycloaliphatic epoxy resins. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2013, 98, 2125–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xie, M.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, Y.; Fang, S. Synthesis and properties of novel liquid ester-free reworkable cycloaliphatic diepoxides for electronic packaging application. Polymer 2003, 44, 923–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, M.; Kawaue, A.; Okamura, H.; Tsunooka, M. Synthesis of novel photo-cross-linkable polymers with redissolution property. Polymer 2004, 45, 7519–7527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Yuan, Y.C.; Rong, M.Z.; Zhang, M.Q. A thermally remendable epoxy resin. J. Mater. Chem. 2009, 19, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, N.; Saito, K.; Simon, G.P. Synthesis of a diamine cross-linker containing Diels–Alder adducts to produce self-healing thermosetting epoxy polymer from a widely used epoxy monomer. Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Yu, C.; Denman, R.J.; Zhang, W. Recent advances in dynamic covalent chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6634–6654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordes, E.H.; Bull, H.G. Mechanism and catalysis for hydrolysis of acetals, ketals, and ortho esters. Chem. Rev. 1974, 74, 581–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fife, T.H. General acid catalysis of acetal, ketal, and ortho ester hydrolysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 1972, 5, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaly, N.; Yameen, B.; Wu, J.; Farokhzad, O.C. Degradable Controlled-Release Polymers and Polymeric Nanoparticles: Mechanisms of Controlling Drug Release. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2602–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielski, R.; Witczak, Z. Strategies for Coupling Molecular Units if Subsequent Decoupling Is Required. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 2205–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binauld, S.; Stenzel, M.H. Acid-degradable polymers for drug delivery: a decade of innovation. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 2082–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Chan, J.M.; Farokhzad, O.C. pH-Responsive Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2010, 7, 1913–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leriche, G.; Chisholm, L.; Wagner, A. Cleavable linkers in chemical biology. Bioorgan. Med. Chem 2011, 20, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Malhotra, S.; Molina, M.; Haag, R. Micro- and nanogels with labile crosslinks – from synthesis to biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 1948–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidil, T.; Tournilhac, F.; Musso, S.; Robisson, A.; Leibler, L. Control of reactions and network structures of epoxy thermosets. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2016, 62, 126–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.-L.; Li, X.; Park, S.-J. Synthesis and application of epoxy resins: A review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z. Synthesis and degradable properties of cycloaliphatic epoxy resin from renewable biomass-based furfural. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 95126–95132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-J.; Jin, F.-L. Thermal stabilities and dynamic mechanical properties of sulfone-containing epoxy resin cured with anhydride. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2004, 86, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).