1. Introduction

Today, thermosetting matrix composite materials are used in countless industrial sectors and applications, including the civil and transport industries, aeronautical, aerospace, and automotive fields, the military sector, and the production of sports equipment. This class of materials are recognized to be very reliable solutions for high-performance and light-weight applications, due to their retained dimensional stability, chemical inertia and rigidity over a wide range of temperatures. However, once fully cured, they cannot be easily reshaped or reprocessed, thus leaving still unsolved the issues of recycling and the lack of technological flexibility [

1]. These properties derive from the presence of cross-links in the molecular structure of thermosets, which have the same energy level as polymerization bonds. Both are covalent bonds, conferring to thermosetting materials high thermal and mechanical stability. However, this stability makes thermosets very difficult to recycle, so current recycling technologies do not align well with modern concepts of material circularity and eco-design [

2]. The primary challenge in recycling thermosetting composites lies in the degradation of the matrix and the incomplete recovery of reinforcing fibers. The leading recycling methods for thermosetting composite materials are mechanical, thermal, and chemical recycling [

3,

4,

5]. Mechanical recycling involves several steps (crushing, grinding, milling) aimed at reducing the size of the waste composite material. These resulting fractions can be used as fillers in short fiber composites, suitable for producing sheet molding compounds. However, the equipment often suffers damage from the friction with the composite fibers, increasing the process's operating costs. Although mechanical recycling has advantages such as non-toxicity and the ability to work at room temperature, the main issue is the generation of dust, which poses health and safety risks to operators. Thermal recycling uses high-temperature treatment or fluids to degrade the thermoset matrix and recover the fibers, through processes such as pyrolysis or using a fluidized bed. Pyrolysis occurs in an inert gas atmosphere without oxygen, heating the composite to 400-600°C to recover fibers. The matrix degrades, producing gas, oil, coal tar, and dust, necessitating fiber cleaning post-process. Fluidized bed thermal recycling, still under development, poses challenges due to polluting gasses, organic solvents, and high energy requirements. Rapid heating degrades the matrix, separating it from the fibers by friction. Chemical recycling, including supercritical or subcritical solvolysis, degrades the thermoset matrix using various solvents and process variables like temperature and pressure, often with catalysts. This method yields long fibers with minimal surface residue and minor degradation in mechanical properties compared to the virgin reinforcement. For instance, solvolysis can be performed at atmospheric pressure, minimizing fiber damage and retaining up to 98% of the initial fibers' tensile strength. Although the processing temperatures involved are lower than pyrolysis, it requires expensive, corrosion-resistant equipment, and solvents can harm the environment and plant personnel. The drawback joining these recycling routes is the lack of recovering the polymer matrix [

4].

In the recent years, industry and academic research teams addressed the study on the design of thermoset systems with built-in recyclability by modifying the polymer matrix with labile linkage, which makes the materials much easier to break down while retaining their mechanical characteristics [

6,

7,

8]. Specifically, the approach is based on introducing in the polymer network degradable cross-linkers or converting permanent cross-linked structures into dynamic crosslinked ones, to achieve de-crosslink and re-crosslink by exchange reactions of cleavable bonds. Indeed, the dynamic bonds implemented into the network are stimuli-responsive to specific conditions (heat, irradiation, chemical attack, or a combination of that) but not under severe conditions, resulting in the recovery of the original monomers or simpler polymers that are readily soluble [

7,

8]. Then, thermosets containing cleavable bonds find attractive usage for the manufacturing of fiber-reinforced polymer-composites in which fibers could be easily recovered after the resin removal preserving good thermo-mechanical characteristics for new applications [

9,

10,

11]. Si et al. [

9] proposed an epoxy vitrimer with a high concentration of exchangeable aromatic disulfide crosslinks to accelerate disulfide bond exchange reactions within the networks and enhance the recycling efficiency of epoxy vitrimers and composites. The dual disulfide vitrimer was degraded by a dilute solution of dithiothreitol (DTT). Furthermore, composites were manufactured, and the carbon fibers were reused to form new carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) composites. However, these techniques require high-temperature conditions, which increase the cost and complexity of the recycling method. Liu et al. [

10] investigated a novel epoxy network cross-linked by imine bonds and hydrogen bonds. The recycling process occurred under non-aggressive conditions, at 50 °C. The fibers were recycled non-destructively and reused to prepare new composite materials, while the recoverable monomer from the matrix resin was used to cure the brittle material. Pastine [

11] highlighted a series of acetal-containing amine hardeners (Recyclamine®, patented by Connora Technologies [

6]) to cross-link commercially available epoxy resins for use in composite materials. Recyclamine® hardeners have a generic polyamine structure with an innovative feature: separable terminal groups held together by a central cleavage point with acetal bonds. These bonds degrade in mild acidic solutions at certain temperatures, allowing the recovery and reuse of the remaining linear polymers. This enables the creation of cross-links that can later be broken, converting the thermoset epoxy matrix back into a reusable thermoplastic polymer (

Figure 1). These novel hardening systems were implemented by other researchers to produce fully recyclable fiber-reinforced composites via resin transfer molding [

12]. Saitta et al. [

13] analyzed two different commercial bio-based thermoset resins to design flax fibers reinforced composites showing recycling characteristics. The authors studied the optimum process parameters to be implemented for the composite preparation as well as the recyclability yield through a specific chemical protocol, verifying the feasibility of separating and recovering both the fibers and resin from the composite samples.

Research efforts on the design, synthesis, and processing of fully recyclable thermosetting formulations are continually expanding with the major target of implementing these polymeric systems in industrial sectors of high technological value. For instance, these recyclable thermosets are considered promising directions of development in the wind energy industry for producing novel recyclable wind turbine blades [

14] providing comparable mechanical performance with respect to traditional epoxy resin composites and the recyclability characteristic of thermoplastics [

15]. To the best of the authors' knowledge, new recyclable epoxy systems are emerging to address the upcoming market demand and in-depth investigation is needed regarding processability for composite material fabrication as well as recyclability aimed at recovering fibers and matrix to reintroduce in new applications.

The present work addressed the recycling pathway of a new cleavable bio-based epoxy resin system (R-Concept, Barcelona, Spain) implemented in the fabrication of fully recyclable composites materials. These bio-epoxy systems combine double benefit towards more sustainable products: 1) incorporation of a bio-based component in the resin formulation with the aim of reducing the environmental impact associated with the use of toxic and expensive fossil sources as feedstocks and 2) implementation of a Recyclamine®-type hardener which enables the recovery of reinforcement (carbon fibers, glass fibers) and the epoxy matrix as recyclable thermoplastic both further integrable into new processes and applications. The resin formulation was first characterized by thermal analysis to evaluate the effect of different curing conditions on the matrix performance. Carbon and glass fiber-reinforced composites were then fabricated via vacuum-assisted resin transfer molding. Thermal, mechanical and microstructural characterization was performed on the obtained composite materials. Finally, an experimental chemical recycling protocol was developed for the recovery of fibers and the thermoplastic fraction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Beluga Whale epoxy resin and the Recyclamine-type hardener R*LAB 005, both supplied by R-Concept (Barcelona, Spain), were employed to produce the thermoset matrix of the composites. According to the manufacturer declaration, R*LAB 005 is an “extra slow” hardening component with a gel time of 100-130 min at 60 °C. Carbon and glass fabrics were used as reinforcement for different composites. The carbon fabric was a plain weave with an areal density of 160 g/m², while the glass fabric was a twill weave with an areal density of 290 g/m². Both fabrics were supplied by Angeloni Group S.r.l. (Venice, Italy).

2.2. Resin System Formulation

The resin-to-hardener ratio was set to 100:35 as recommended by the R-Concept resin manufacturer. Furthermore, this bio-epoxy system cures at room temperature and post-cure options are not indicated in the technical datasheet. Therefore, given the lack of studies in literature on this resin and with the aim of establishing the best processing parameters for the subsequent manufacturing of composites, three post-curing conditions were investigated: no post-curing (RT), 100°C for 3 h (PC100), and 140°C for 3 h (PC140). Similar post-curing treatments were probed by Ferrari et al [

16], who investigated R-Concept resins in the production of biocomposites incorporating waste flour. The resin was poured into a steel mold to manufacture specimens with dimensions suitable for the thermal analysis.

2.3. Composite Laminates Manufacturing

Composites laminates (200 mm

150 mm) were realized using a lab-scale vacuum-assisted resin transfer molding system (

Figure 2). The infusion layout consisted of: (a) a glass mould surface, (b) the fiber reinforcement stack (10 layers with 0/90 orientation), (c) a polyethylene perforated release film to control the resin content into the laminate, (d) a polyester fabric bleeder cloth to allow airflow throughout the vacuum bagging process as well as bleed out an excess resin in a composite part, (e) a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) film sealed to the mould by a tackifier tape to form a sealed chamber. Silicon tubes were used to let the resin enter the bag and to allow the suction of the air, and then the resin itself. The system was connected to a Divac 0.6L diaphragm pump (Leybold, Cologne, Germany) to ensure a vacuum pressure between

0.8 and

1 bar. For each type of fabric, three composite plates have been produced, one for each post-curing condition implemented for the neat resin (RT, PC100, and PC140). The obtained plates had average thickness of 2.5 mm and 2.2 mm for the glass and carbon composites, respectively. Specimens for thermal and mechanical characterization were obtained from the plates by means of a computerized numerical control (CNC) cutting machine (Falcon 1500 by Valmec, Pescara, Italy).

2.4. Procedure for Composites Recycling: Fiber and Polymer Recovery

After the thermal and mechanical characterization of the composite laminates, the materials were subjected to a recycling process following the experimental protocol implemented by Cicala et al. [

17]. The first step is an acid attack, where about 10-11 g of composite material is immersed in a 300 ml of acetic solution (40 vol.% of acetic acid). Acetic acid (purity level

99.8%) was purchased from Honeywell. The solution is brought up to 80°C and left to react for 2.5 hours. Once the thermoset matrix is dissolved, the fibers are filtered from the solution, then washed in distilled water and left to dry. At this point, the acid solution, remaining at a temperature of 80°C, is neutralized with 105 ml of a 2 M aqueous solution of NaOH (Carlo Erba Reagents S.A.S., Val-de-Reuil, France). By introducing the basic solution into the acid, therefore, a precipitate forms progressively. That corresponds to the thermoset matrix recovered as a thermoplastic polymer. Once all the basic solution has been introduced with a pipette, the system is left to react and cool to a temperature of 40°C. Next, the thermoplastic is filtered from the solution and washed with 150 ml of distilled water. A few drops of basic solution are added to aggregate the precipitates, always using a pipette. In the end the polymer obtained is filtered and left to dry. The workflow of the recycling procedure is illustrated in

Figure 3.

2.5. Testing Methods

2.5.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

TGA was performed on both bio-epoxy neat matrix and the recovered polymer from the recycling process using a TG 209 F1 Libra analyzer by Netzsch (Selb, Germany). The samples ( 20 mg) were tested in an inert nitrogen atmosphere from room temperature to 800 °C, employing a heating ramp of 10 °C/min.

2.5.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC was carried out with a DSC 214 Polyma by Netzsch (Selb, Germany) in a nitrogen atmosphere, temperature range from

40 °C to 170 °C, and a scanning rate of 20°C/min. The mass of the tested samples (bio-epoxy neat matrix at the different post-curing conditions and the recovered polymer) was

10.5 mg. The glass transition (T

g) values were recorded on the second heating scan to avoid interference from the endothermic peak of the polymer’s relaxation enthalpy. The relaxation enthalpy occurs in the glass transition region and corresponds to the release upon heating of degrees of freedom after the material had been cooled below its T

g [

18].

2.5.3. Mechanical Testing on Composite Laminates

Hardness and flexural tests were conducted to evaluate the influence of the type of fabric (glass and carbon) and the post-curing regime on the mechanical behavior of the manufactured laminates.

Shore D hardness measurements were performed using an analog hardness tester (Zwick/Roell GmbH, Ulm, Germany) according to ASTM D-2240 [

19]. The hardness value for each sample was calculated as the average of 10 measurements.

Three-point flexural tests were conducted on a Zwick/Roell Z010 machine (Zwick/Roell GmbH, Ulm, Germany), following the standard method ASTM D7264 [

20]. Samples (100 mm length and 10 mm width) were tested at 2 mm/min with a span of 70 mm. Strain was recorded with a displacement transducer in contact with the samples. At least three replicates were performed on each formulation.

2.5.4. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

Following the study of the mechanical properties of the composite laminates, DMA was conducted considering the optimum post-curing condition. The analysis was performed according to ISO 6721 [

21] with a DMA 242 E Artemis by Netzsch (Selb, Germany) in a three-point bending configuration from 30 °C to 140 °C using a heating ramp of 2 °C/min and a frequency of 1 Hz.

2.5.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The fiber-matrix interface in the produced composite laminates as well as the surface morphology of the fibers recovered from the recycling process were analyzed by means SEM (Tescan Mira 3, Brno, Czech Republic). Prior the investigation, the specimens (cross-section of the composite specimens and recovered fibers) were gold-coated using an Edwards S150B sputter-coater (Edwards Ltd., Burgess Hill, UK).

3. Results

3.1. TGA on Bio-Epoxy Resin Matrices

The thermogravimetry (TG) and derivative thermogravimetry (DTG) curves of the resin post-cured under different conditions (RT, PC100, and PC140) are reported in

Figure 4. The graph clearly showed that the weight loss occurs in two steps. The first degradation stage was concentrated in the 180-200°C temperature range with a mass change of about

5 wt.%. Within the temperature range of 340-350 °C the main degradation event was observed, with a massive loss in weight of about 80%. In this stage the thermal decomposition took place for the bio-epoxy resins.

Table 1 summarizes the onset temperature of the two degradative processes undergone by the resin. T

5% stands for the onset temperature related to the first weight loss whereas T

max indicates the temperature corresponding to the maximum degradation rate. TGA results highlighted that the non-post-cured resin showed superior thermal stability compared to the cured ones. Furthermore, as the post-cure temperature increases, the thermal stability of the polymer decreases. This result can be mainly explained by considering thermo-degradative effects that the resin experiences due to the presence of “bio” component in its chemical structure. Indeed, these types of polymers have a large portion of the carbon content replaced by a biomass origin that is sensitive to high temperature stress [

22]. In agreement with the study from Di Mauro et al. [

23] and considering the chemical structure of the R-Concept bio-epoxy system [

4], the first degradation step can be ascribed to the breakage of the ester linkages, while the second one with the cleavage of the products formed during the first degradative step.

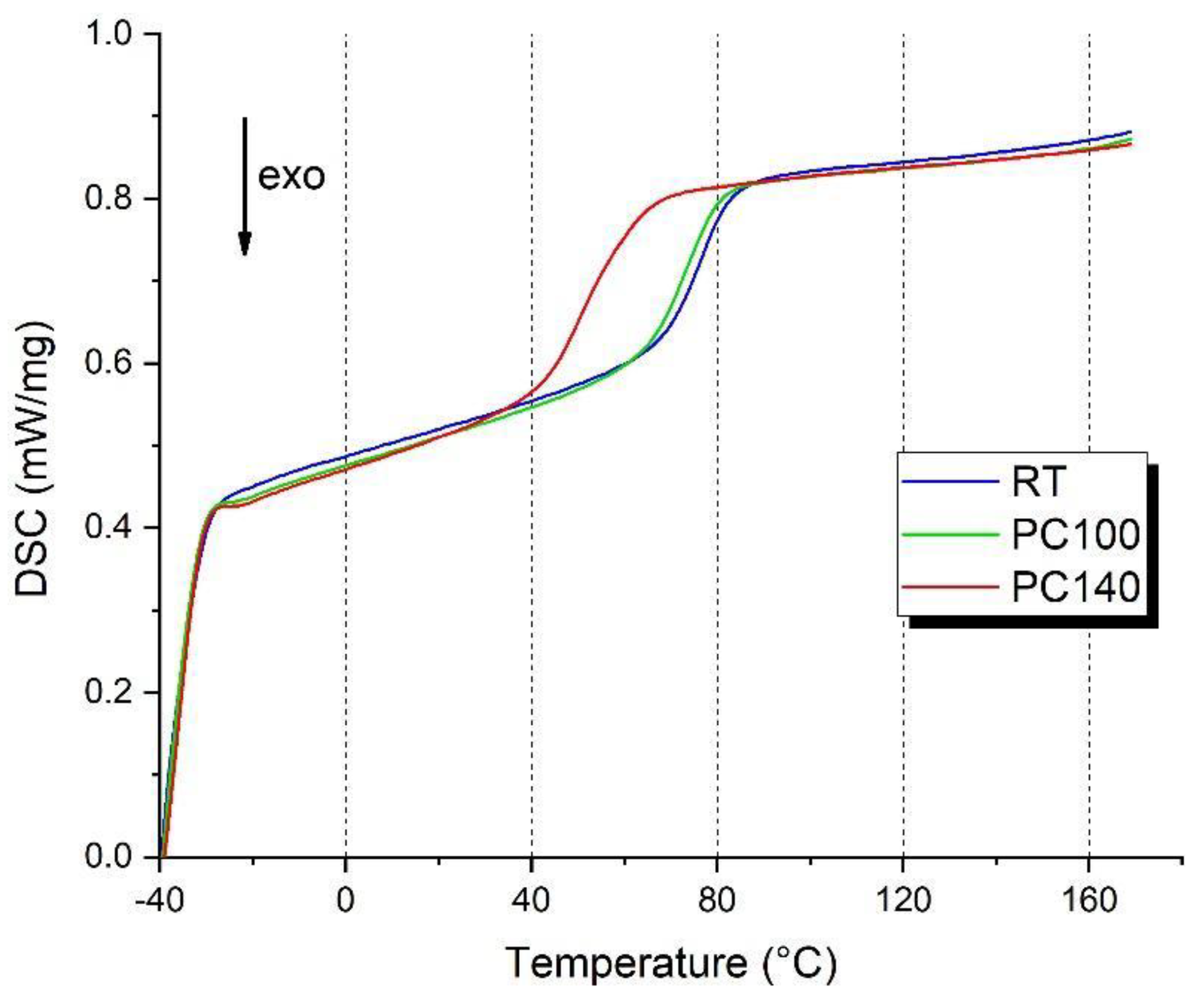

3.2. DSC on Bio-epoxy Resin Matrices

Figure 5 displays the DSC curves related to the second heating scan from which the T

g values were determined (see

Table 2). Non-post-cured resin had the highest T

g value (76.6°C). By implementing thermal post-cure treatments, the T

g was progressively reduced. The PC100 condition didn’t significantly alter the thermal characteristics of the material (approximately 4°C lower than RT condition) while at 140°C post-curing a drop of almost 25 °C compared to the RT sample was found. The results confirm the evidence highlighted by the TGA analysis, namely that thermal stress due to excessive post-curing temperature induces degradation of the biomass deriving fraction of the resin resulting in T

g decline. The influence of post-curing conditions on the thermo-mechanical properties of bio-based epoxy resins was investigated by Lascano et al. [

24]. The authors found that excessive high temperatures potentially restricted the formation of homogeneously cross-linked structures by limiting the molecular diffusion during the resin curing, resulting in a wide distribution of gaps between the cross-linked regions. As a result, reduction in T

g was detected due to the increased free volume fraction into the polymeric network. The T

g values obtained under RT and PC100 conditions are consistent with the range declared by the supplier (55 – 85 °C). This bio-resin system that achieves optimal thermal performance without special thermal curing conditions can certainly be valuable for industrial mass production reasons and to fabricate large-sized components (e.g., wind turbine blade).

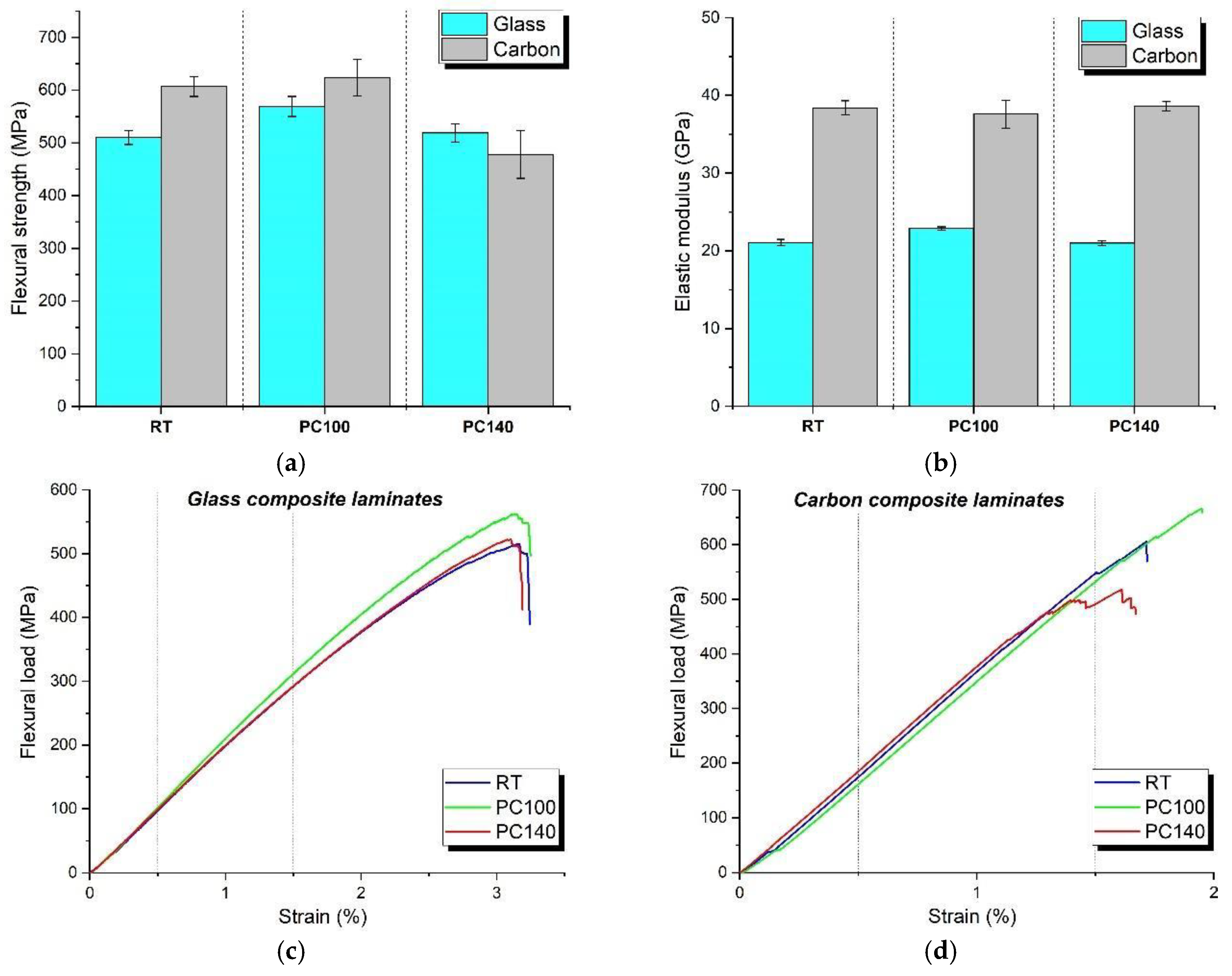

3.3. Mechanical Testing on Composite Laminates

Figure 6 displays the effect of different post-curing regime on the flexural behavior of carbon and glass composite laminates. As expected, the carbon laminates outperformed the glass-based ones. From

Figure 6a, the carbon fiber reinforced laminate showed higher flexural strength for RT and PC100 conditions (607 MPa and 624 MPa, respectively). The flexural strengths of glass fiber reinforced composite were 510 MPa and 569 MPa for RT and PC100 post-curing, respectively. Therefore, compared to the neat matrix, the post-cure treatment at 100°C on composites was effective in improving the mechanical properties. Although, the insertion of the fiber bed reduces the macromolecular mobility and the proper matrix crosslinking degree, a well-balanced post-cure treatment would assist the increment in crosslink density and interfacial bonding with the fibers [

25]. However, the post-cure treatment at 140°C was excessive, leading to a reduction in flexural strength (– 10% for glass laminate and – 23% for carbon laminate over to the composites post-cured under PC100 condition). Too high post-curing temperatures would cause excessive resin shrinkage and the development of residual stresses at the fiber-matrix interface (debonding) [

26]. PC140 treatment degraded carbon-based laminate more significantly than glass-reinforced one. It is presumably that this effect is also related to the different compaction experienced by the two types of fabrics in the same process conditions to produce the composites. The SEM investigation in the next section will clarify this aspect. As shown in

Figure 6b and on the stress-strain plots displayed in

Figure 6c-d, post-cure has a negligible effect on the laminate stiffness in their corresponding groups. This evidence agrees to the on reported in earlier works by Umarfarooq et al. [

25].

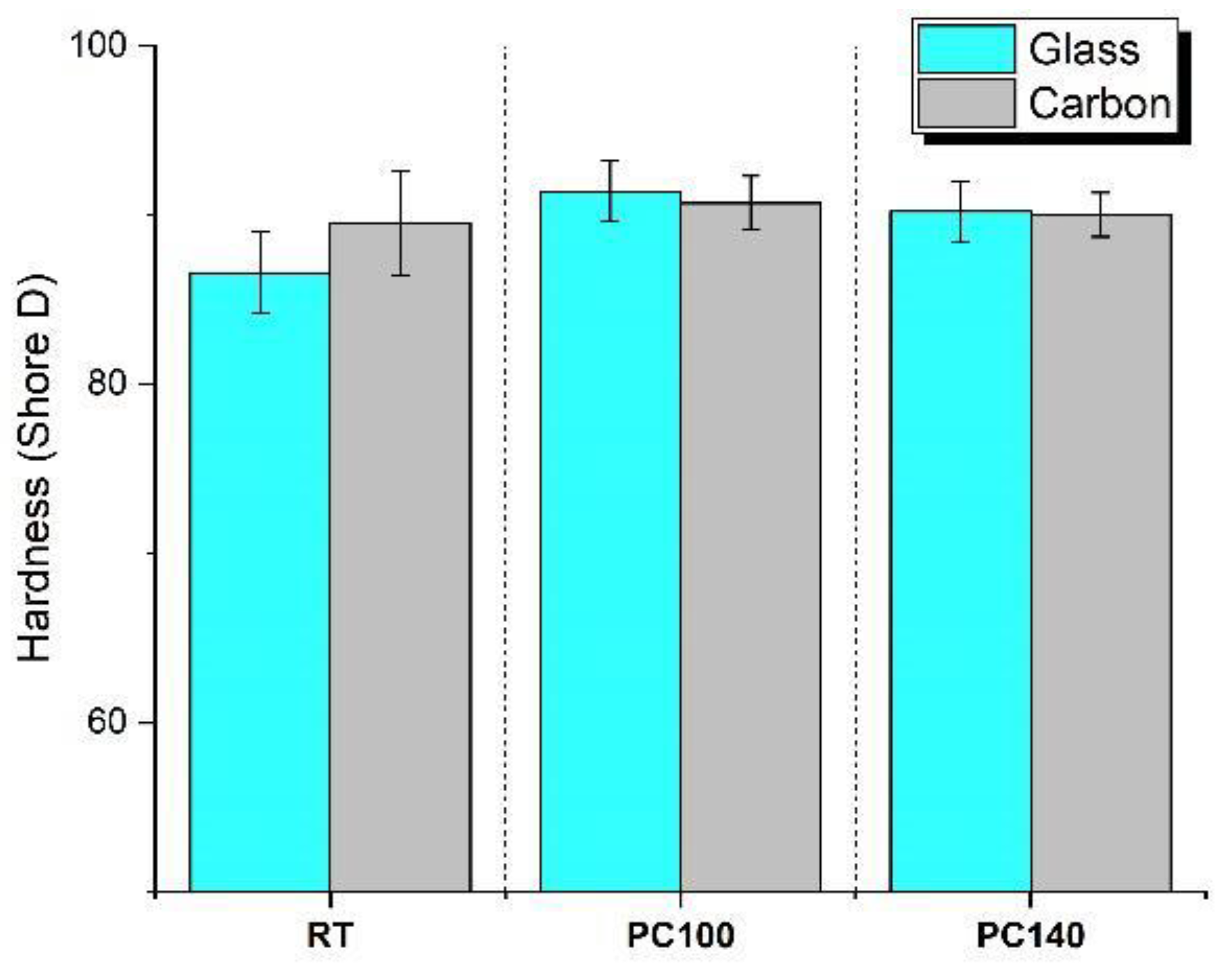

Shore D hardness of the laminates (

Figure 7) was weakly influenced by both the type of reinforcement and the post-cure treatment. However, the results show a slight improvement in hardness in the case of PC100 laminates corroborating the flexural test results. An optimal post-curing regime improves the bonding between fibers and resin, due to increase in cross-linking and stacking, which reduces the polymer chain mobility and making it to become more resistant to the penetration of indenter [

27].

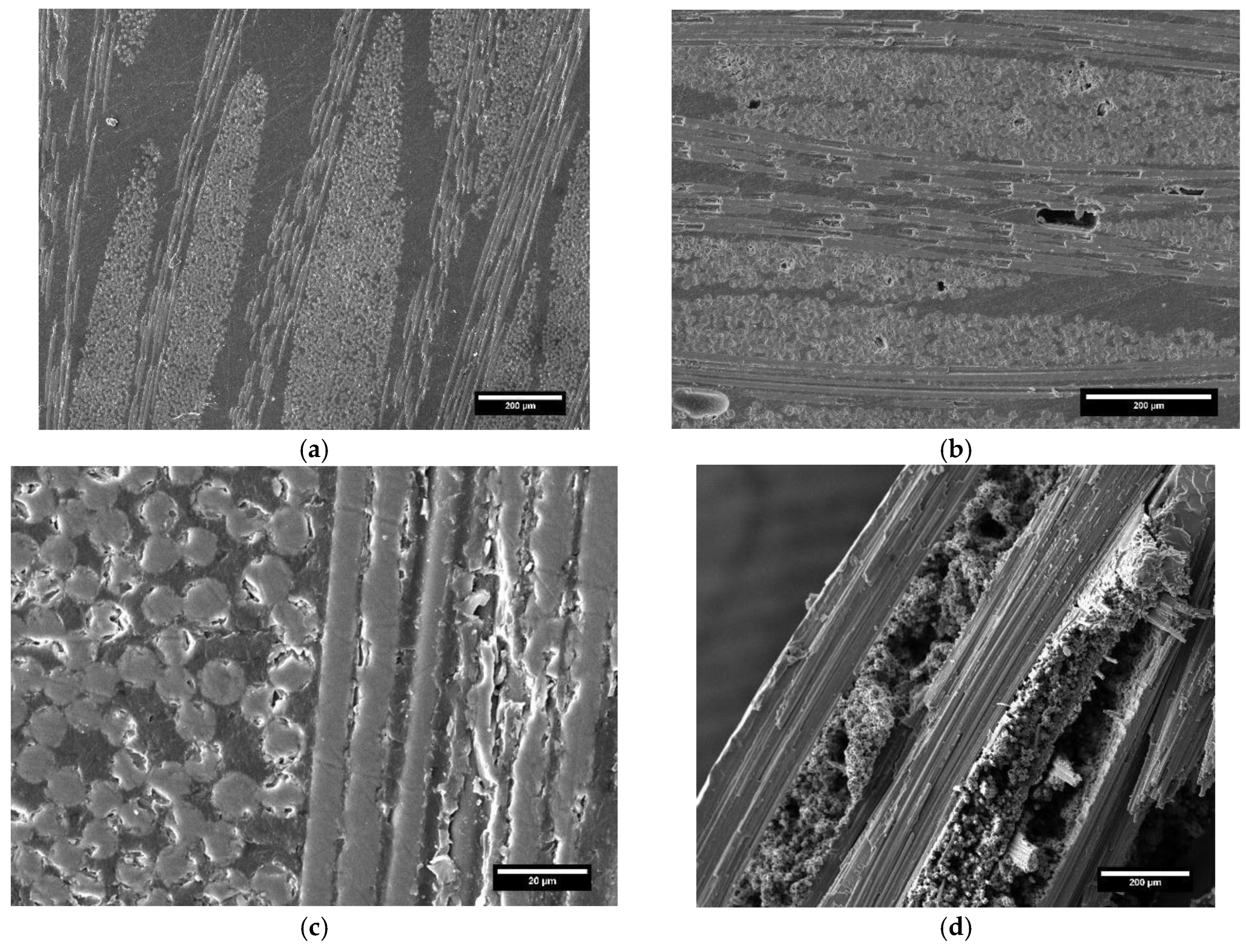

3.4. SEM Analysis on Composite Laminates

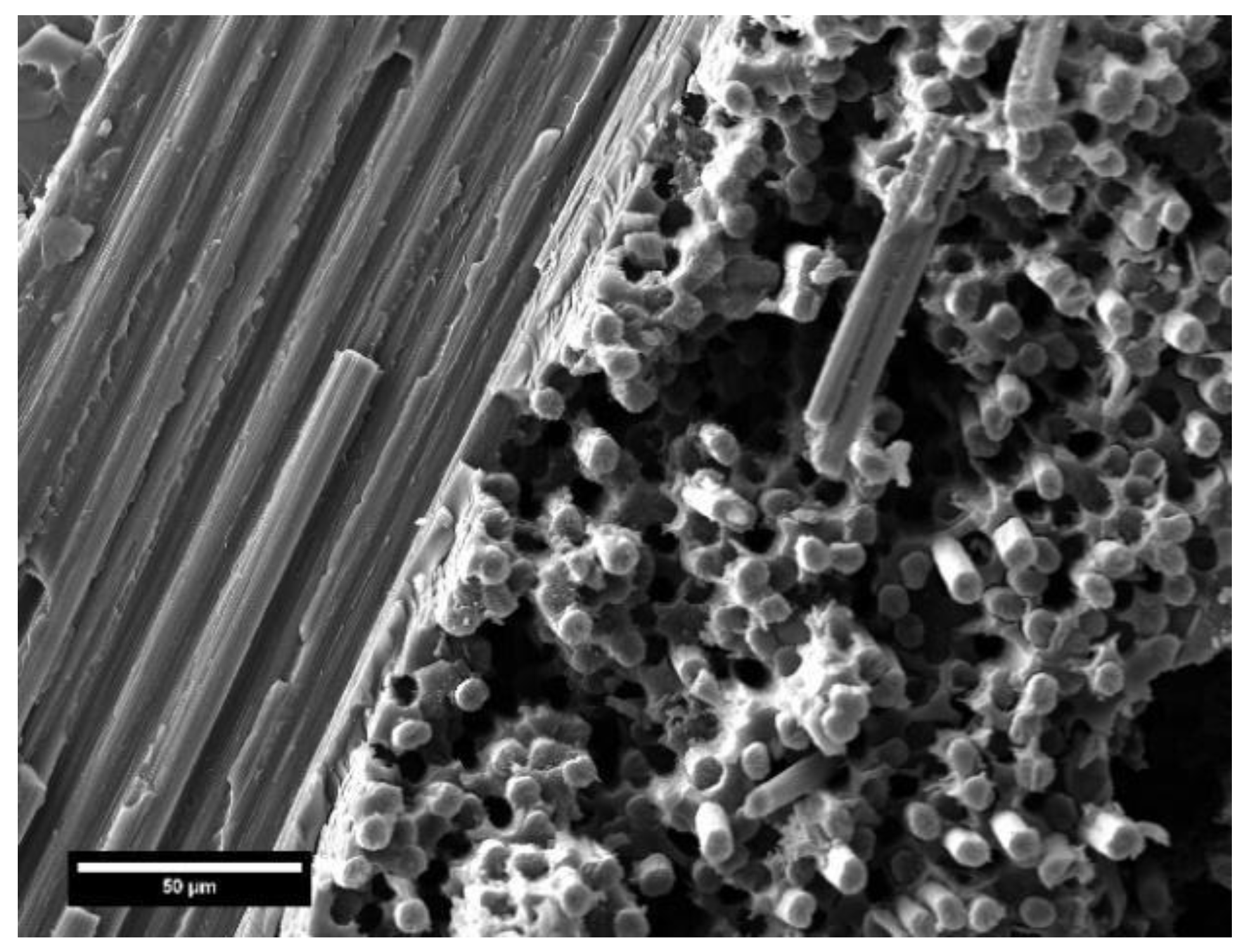

SEM micrographs in

Figure 8 illustrate the polished cross-section surface of the glass (

Figure 8a-c) and carbon (

Figure 8b-d) laminates post-cured at the best condition (PC100). At the same post-curing regime, the laminates showed marked differences in terms of microstructure. The glass-based composite displayed a non-defective cross-section free of inter-layer and inter-fiber voids. The carbon-based composite laminate, although over the PC100 post-cure conditions had superior mechanical performance compared to glass reinforced composite, showed several defects dispersed throughout the surface which limit the potential improvement of carbon fibers on the strength of the final composite.

Figure 8d highlights a more evident delamination of the composite due to the poor compaction of the fabric The formation of voids in the composite is attributable to two main aspects, already discussed in the review work by Xueshu and Fei [

28]: vacuum pressure and resin flow. Under the pressure conditions implemented in the present study, the carbon fabric, being significantly more rigid than glass, provided greater resistance to the compaction and resin flow resulting in not-impregnated zones inside the laminates. Therefore, optimization of the process parameters of resin transfer molding (mainly, the pressure) is challenging to increase the performance of carbon-based composites by minimizing the percentage of voids.

As verified by mechanical tests, post-cure treatment at 140°C significantly degraded the performance of the carbon-based laminate. SEM images of

Figure 9 show the fracture surfaces of the PC140 carbon reinforced composite specimen. and the degradation that the matrix undergoes over too high post-curing temperature. This last aspect is also supported by fiber pull-out phenomena displayed in the micrograph. Fiber pull-outing generally occurs when composites are post-cured at elevated temperature above the glass transition of the matrix. As the polymer becomes critically softer, adhesive and cohesive failures turn out to be more dominant. This phenomenon then allows for fiber and matrix materials to be more easily debonded [

29].

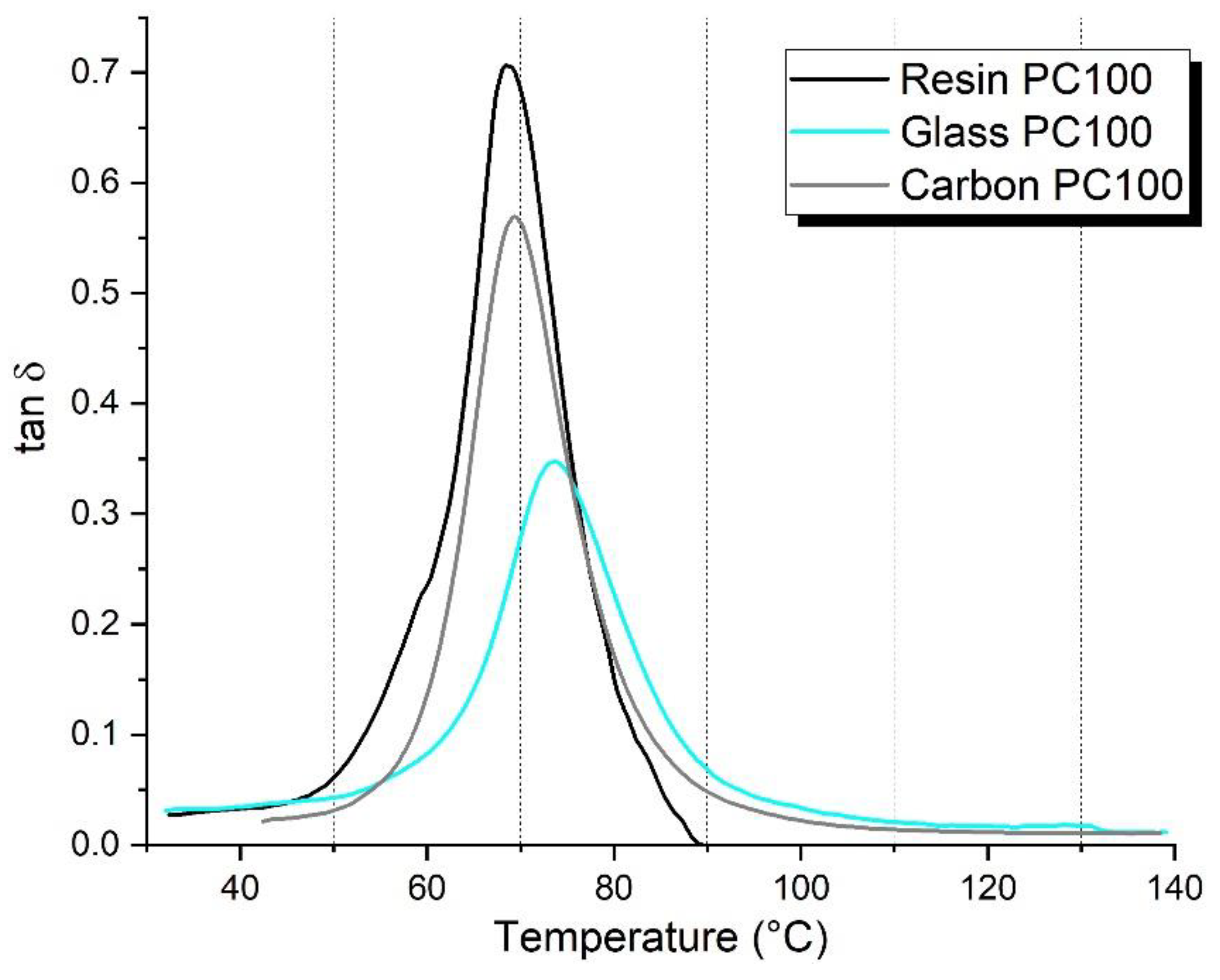

3.5. DMA on Composite Laminates

Thermo-mechanical properties of the composites were studied by DMA on the samples post-cured at 100 °C (PC100), representing the laminates with the highest mechanical strength properties. Plain resin post-cured at the same condition was taken as a reference to evaluate the change in T

g as a function of the type of reinforcing fabric and fiber-matrix interaction. Variations of the damping factor (tan δ) with respect to temperature curves are compared in

Figure 10. T

g were then evaluated as the peak temperature of the curve and the inherent values summarized in

Table 3. As might be expected, the composites lead to a shift of T

g towards higher temperature compared to pure resin, because of the lower molecular mobility of the polymer chain due to the presence of fibers [

30]. However, the extent of increase in the glass transition is very different between carbon and glass-based laminates reflecting different fiber-matrix interfacial properties experienced in the two materials. The microstructural defectiveness found in carbon-based laminates was responsible for a limited increase in T

g (about 1 °C higher than pure resin). On the other hand, glass composite showed a more marked increment (+ 4 °C) justifying the homogeneous fiber impregnation and better interfacial fiber-matrix adhesion. The different fiber-matrix bonding was also interpreted in terms of tan δ values. Damping factor is a sensitive indicator of all kinds of molecular motions that are going on in a material. Logically, in a composite the molecular motions at the interface contribute to the damping of the material. Strong cohesion of fibers and polymer matrix reduces the mobility of the molecular chains at the interface and therefore brings to a damping reduction [

31]. The lowest tan δ peak value detected in glass-based composite sample corroborated the evidence of the better interfacial cohesiveness between glass fiber and resin.

3.6. Chemical Recycling on Composite Laminates

The chemical recycling procedure implemented in the present work showed material recovery yields exceeding 95%. As detailed in

Table 4, it was feasible not only to recover clean fibers suitable to produce new fabrics from recycled feedstock (such as woven mats) for composites but is also possible to convert the thermoset matrix into a reprocessable thermoplastic polymer. Furthermore, the recycling process has a very low environmental impact both in terms of energy consumption and in terms of pollutants. In fact, the maximum temperature achieved is about 80°C and the chemical additives employed are acetic acid and sodium hydroxide. In addition, acetic acid could be recovered and used for further chemical recycling stage or used in other industrial processes involving sectors such as food, pharma, chemical, textile, polymer, medicinal, and cosmetics [

32]. Such aspect would lead to a totally eco-sustainable production and disposal of thermosetting matrix composite materials.

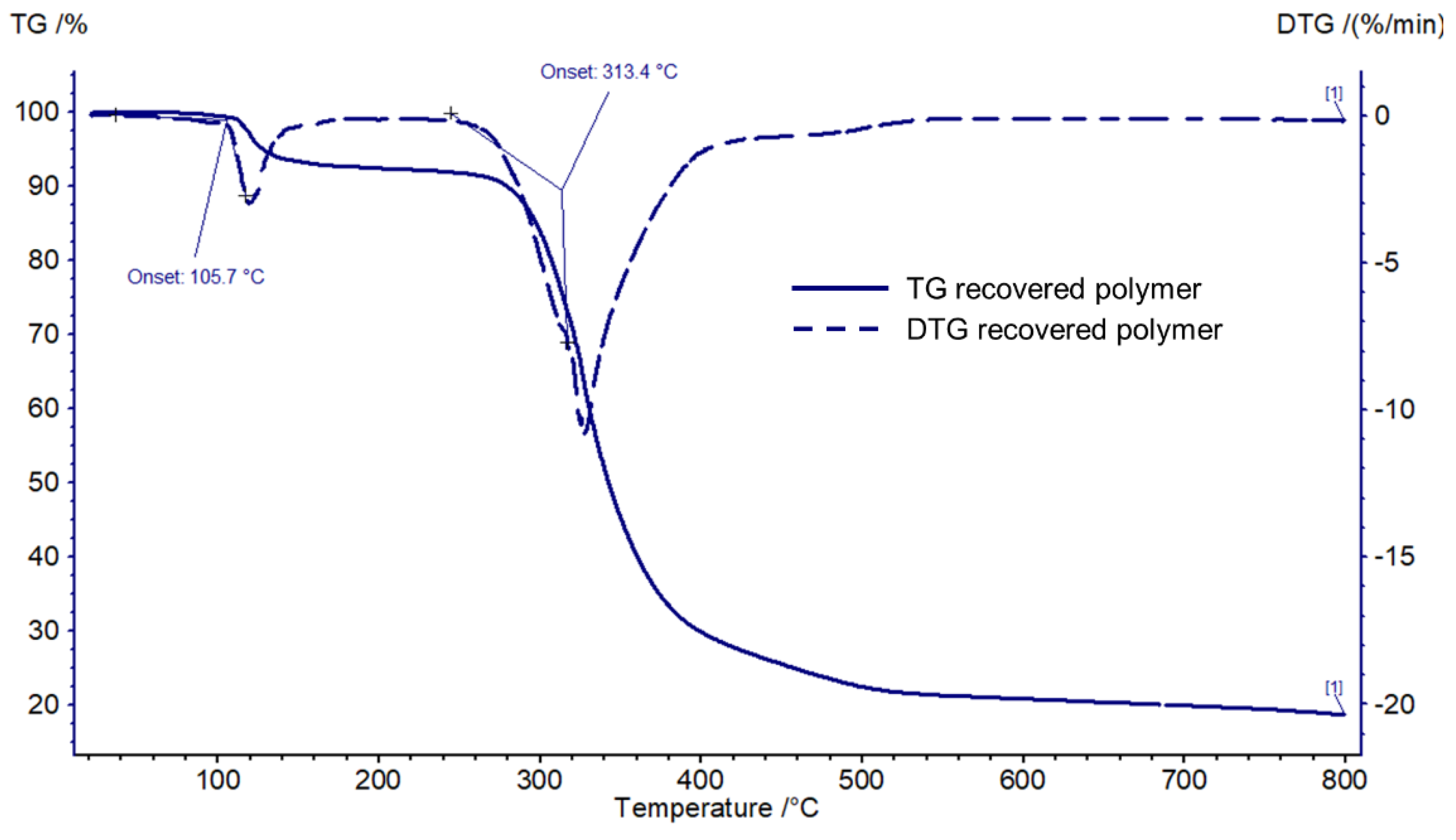

3.1.1. Thermal Characterization of the Recovered Polymer

Figure 11 reports the TGA thermogram of the recovered polymer. Thermal degradation of the polymer mainly occurred in two regions. The initial mass loss (~ 10 %) was related to the release of moisture remaining trapped into the polymer’s structure during drying after recycling treatment. The main degradation took place around 340°C (onset temperature of 313.4°C) due to the total decomposition of the recovered thermoplastic. The result agrees with those from Dattilo et al. [

33] who studied the thermomechanical properties of thermoplastic polymers deriving from R-Concept bio-based epoxy resin system (Polar Bear + R*101) recovered from similar chemical recycling protocol. The authors ascribed the degradation to the chain scission of the C–O bond. It should also be noted that for the TG curve a 20% mass remaining appears at 800°C. This value determines that some fibers passed through the solution's filtration system during the second step of the recycling process remaining embedded inside the polymer mass. It is important to underline that at an industrial scale, with an optimized filtration system, the remaining of this small portion of fibers within the polymer can be avoided obtaining “clean” matrix for new processing. However, the “contamination” of the recovered thermoplastic with the fibers can also represent an added value when the aim is to obtain fiber-filled pellets intended for injection moulding processing.

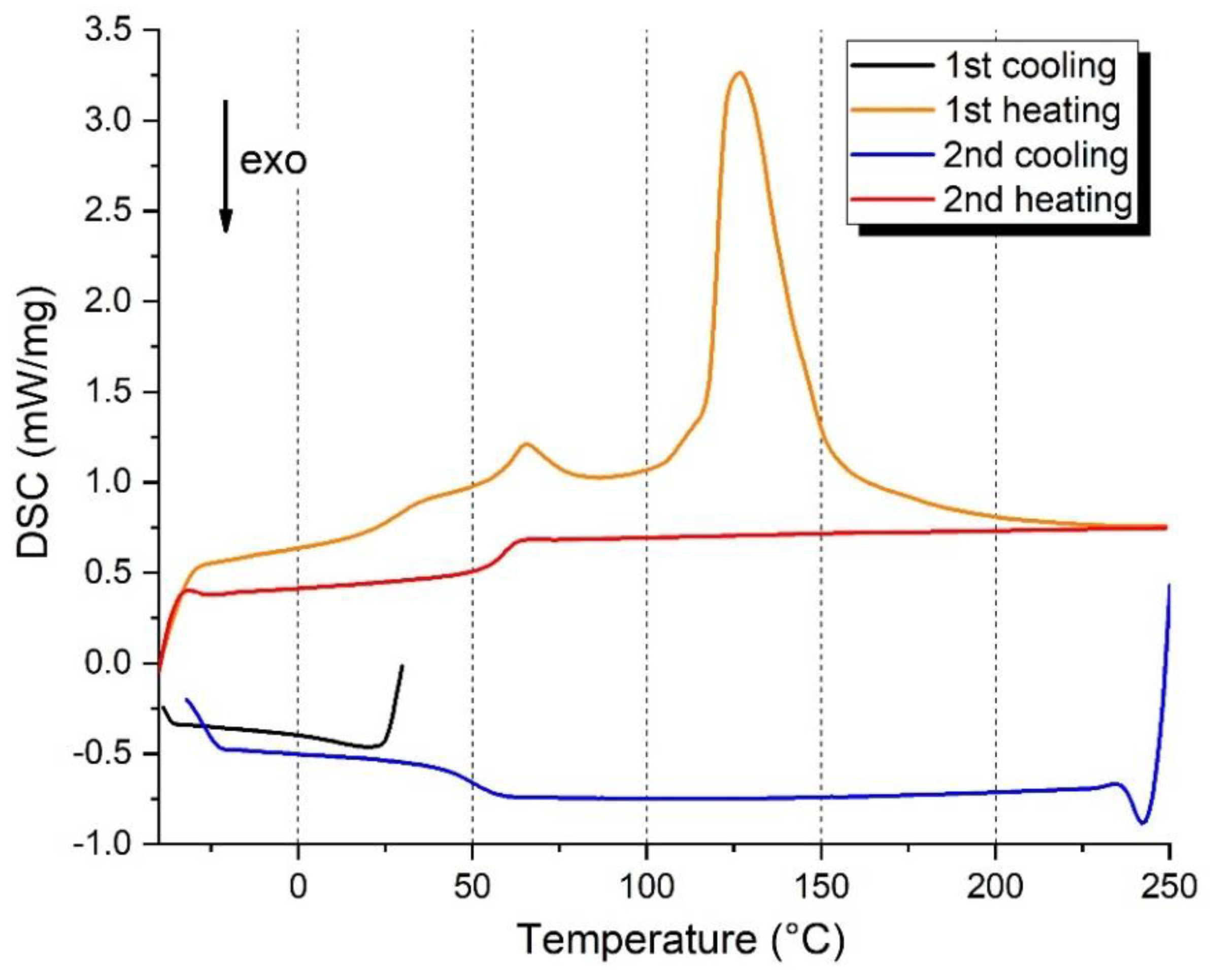

DSC thermogram of the recovered polymer is displayed in

Figure 12. As also verified from TGA, the first heating curve showed a broad endotherm around 100-150°C representing the loss of moisture from the sample. The T

g was determined from the second heating curve, obtaining a value of 59.4 °C. This value falls within the representative range of glass transition temperature of these polymer systems listed in Ref. [

34]. As expected, the achieved T

g is lower than those of bio-epoxy resins due the conversion of the network into a linear structure typical of thermoplastics. The referenced study also reported promising mechanical properties for these recovered polymers (tensile modulus of 2.4 GPa and tensile strength of 57 MPa) demonstrating good potential for new applications and competitiveness with other well-established thermoplastic polymers on the market. This will require a more extensive characterization of the polymer recovered in the present work and related study on its processing feasibility (such as by injection moulding or 3D printing).

3.1.2. Morphological Characterization of the Recovered Fibers

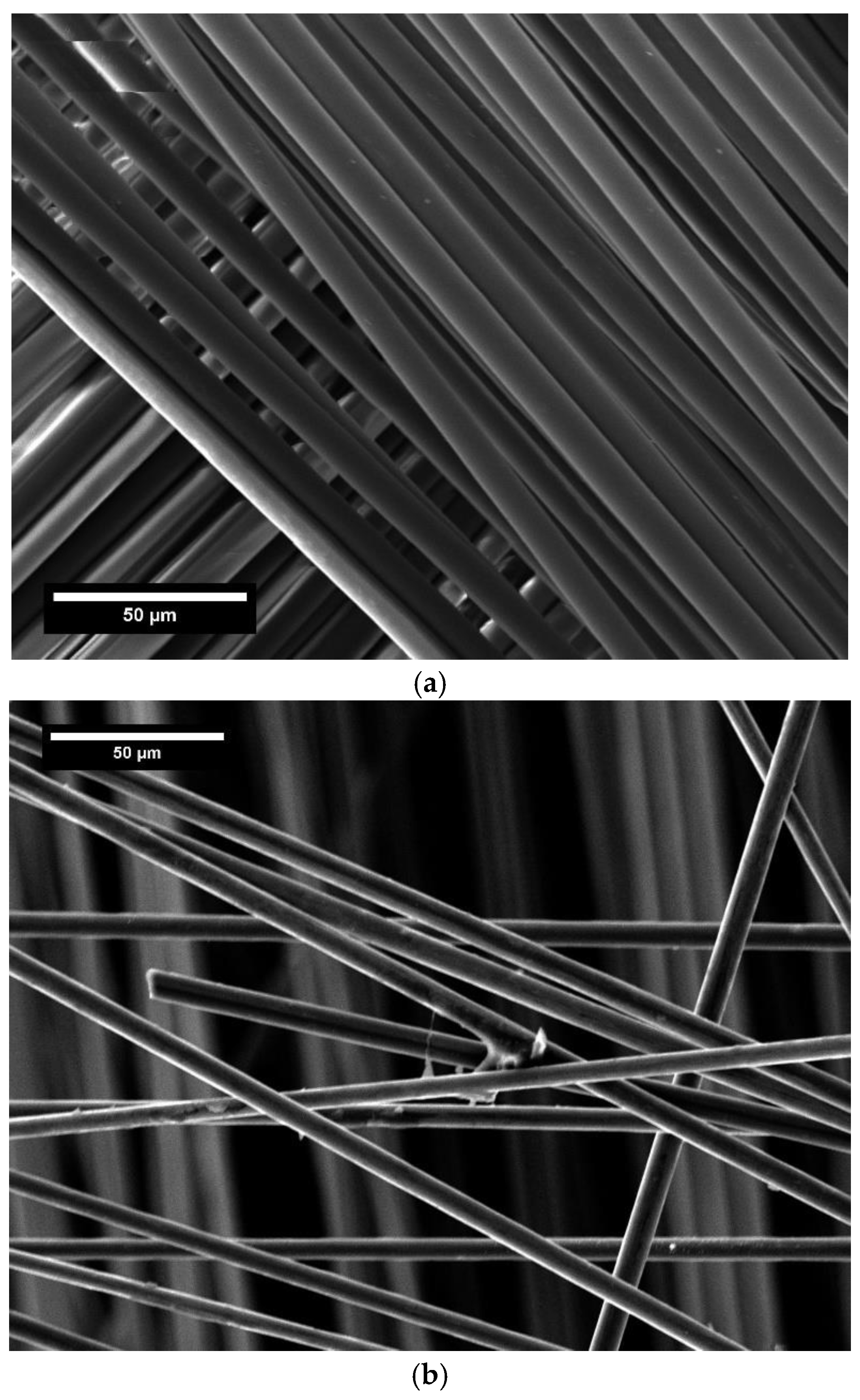

The morphology of the fibers recovered from the chemical process were observed via SEM.

Figure 13a-b show the micrographs of glass and carbon fibers, respectively. The surfaces were generally quite clean with just few polymeric residues along carbon fibers. However, by means ultrasonic bath cleaning most of the loosely attached residue on the surface ca be easily removed. In addition, the implemented chemical treatment does apparently not affect the fiber surface quality in terms of roughness and defects. Single-fiber mechanical characterization will be necessary to investigate in detail the influence of the recycling process on the structural integrity of the reclaimed fibers. This is a fundamental aspect to know also to direct the use of the recovered fibers in new engineering applications.

5. Conclusions

This paper studied the properties, processability for composite laminates manufacturing, and recyclability of a room-temperature curable and fully recyclable bio-epoxy resin system. First, the bio-based resin was thermally characterized to assess the influence of different post-curing conditions on its thermal stability and glass transition temperature. Then, glass and carbon composite laminates were produced investigating the mechanical, microstructural, and thermal properties as a function of the selected curing regimes. Finally, a recycling procedure was implemented to verify the possibility of recovering the thermoplastic—based matrix and fibers reusable for new applications.

The main results are listed below:

For the neat bio-epoxy resin the post-cure at 100°C and 140°C progressively reduced the thermal stability and the glass transition temperature due to degradation phenomena of the bio component of the resin. The best condition was the non-post-cured resin showing a glass transition temperature of 76.6 °C.

The post-curing at 100°C on the produced composite laminates positively influenced the enhancement of the crosslinking of polymer chains, which was reflected in the improvement in the mechanical strength. With respect the non-post-cured laminates, the flexural strength improved by 3% and 12% in carbon and glass-based composites, respectively. The post-curing at 140°C was instead detrimental for the mechanical performance.

Carbon laminates were more affected by structural defects due to the combined effect of the high stiffness of the fabric and the unoptimized pressure conditions of the resin transfer moulding system. This was evident from both the SEM microstructural analysis and the glass transition analysis using DMA.

A successfully chemical recycling procedure was developed accounting for recovery yields up to 98.8%. The recovered thermoplastic showed relevant thermal properties for new engineering applications (thermal stability up to 400°C and glass transition temperature of 59.4°C). The fibers were recovered cleaner and without evident damaging. This approach enables a circular economy scenario within the composite materials sectors.

These outcomes are encouraging for further research efforts. Next works will be focus on the optimization of the composites’ manufacturing procedure to achieve best performance and enable the possibility to create fully recyclable components intended for a lot of industrial sectors (automotive, energy...). Special focus will be on to the characterization and processability of the secondary raw materials recovered from the recycling process. Reclaimed polymer and fibers can represent new “circular” feedstock within the composite industry.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, M.V.; methodology, M.V.and M.S.; software, F.S and J.T.; validation, M.V., F.S., J.T.; formal analysis, M.S..; investigation, I.R. and A.B.; data curation,A.B. and I.R.; writing—original draft preparation, I.R and A.B.; writing—review and editing, M.S.and I.R.; supervision, M.V. and M.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out within the MICS (Made in Italy – Circular and Sustainable) Extended Partnership and received funding from the European Union Next-GenerationEU (PIANO NAZIONALE DI RIPRESA E RESILIENZA (PNRR) – MISSIONE 4 COMPONENTE 2, INVESTIMENTO 1.3 – D.D. 1551.11-10-2022, PE00000004). This manuscript reflects only the authors’ views and opinions, neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be considered responsible for them. The authors thank Angeloni Group S.r.l. (Venice, Italy) for the free supply of the material used for the preparation and production of the composite laminates, and R*concept of barcellona for permission in supply this particular thermosetting bioresin. The authors also acknowledge Luciano Fattore and Riccardo Martufi (Centro Saperi&Co – Sapienza University of Rome) for technical support in cutting samples with the computerized numerical control cutting machine.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alabiso, W.; Schlögl, S. The Impact of Vitrimers on the Industry of the Future: Chemistry, Properties and Sustainable Forward-Looking Applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 1660. [CrossRef]

- Utekar, S.; Suriya, V. K.; More, N.; Rao, A. Comprehensive study of recycling of thermosetting polymer composites–Driving force, challenges and methods. Composites Part B: Engineering 2021, 207, 108596. [CrossRef]

- Krauklis, A.E.; Karl, C.W.; Gagani, A.I.; Jørgensen, J.K. Composite Material Recycling Technology—State-of-the-Art and Sustainable Development for the 2020s. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 28. [CrossRef]

- Saitta, L.; Rizzo, G.; Tosto, C.; Cicala, G.; Blanco, I.; Pergolizzi, E.; Ciobanu, R.; Recca, G. Chemical Recycling of Fully Recyclable Bio-Epoxy Matrices and Reuse Strategies: A Cradle-to-Cradle Approach. Polymers 2023, 15, 2809. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chevali, V. S.; Wang, H.; Wang, C. H. Current status of carbon fibre and carbon fibre composites recycling. Composites Part B: Engineering 2020, 193, 108053. [CrossRef]

- Connora Technologies. Available online: https://gust.com/companies/connora-technologies (accessed on 21 June 2024).

- Morici, E.; Dintcheva, N.T. Recycling of Thermoset Materials and Thermoset-Based Composites: Challenge and Opportunity. Polymers 2022, 14, 4153. [CrossRef]

- Kuroyanagi, M.; Yamaguchi, A.; Hashimoto, T.; Urushisaki, M.; Sakaguchi, T.; Kawabe, K. Novel degradable acetal-linkage-containing epoxy resins with high thermal stability: synthesis and application in carbon fiber-reinforced plastics. Polymer Journal 2022, 54(3), 313-322. [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Zhou, L. ; Wu, Y. ; Song, L. ; Kang, M. ; Zhao, X. ; Chen, M. Rapidly reprocessable, degradable epoxy vitrimer and recyclable carbon fiber reinforced thermoset composites relied on high contents of exchangeable aromatic disulfide crosslinks. Composites Part B: Engineering 2020, 199, 108278. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, F.; Yang, L.; Wang, B.; Huang, Y.; Hu, Z. Closed-loop recycling of carbon fiber-reinforced composites enabled by a dual-dynamic cross-linked epoxy network. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2023, 11(4), 1527-1539. [CrossRef]

- Pastine, S. Can epoxy composites be made 100% recyclable?. Reinforced Plastics 2012, 56(5), 26-28. [CrossRef]

- Cicala, G.; Pergolizzi, E.; Piscopo, F.; Carbone, D.; Recca, G. Hybrid composites manufactured by resin infusion with a fully recyclable bioepoxy resin. Composites Part B: Engineering 2018, 132, 69-76. [CrossRef]

- Saitta, L.; Prasad, V.; Tosto, C.; Murphy, N.; Ivankovic, A.; Cicala, G.; Scarselli, G. Characterization of biobased epoxy resins to manufacture eco-composites showing recycling properties. Polymer Composites 2022, 43(12), 9179-9192. [CrossRef]

- Mishnaevsky Jr., L. How to Repair the Next Generation of Wind Turbine Blades. Energies 2023, 16, 7694. [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.; Rossitti, I.; Biblioteca, I.; Sambucci, M. Thermoplastic Composite Materials Approach for More Circular Components: From Monomer to In Situ Polymerization, a Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 132. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, F.; Esposito Corcione, C.; Striani, R.; Saitta, L.; Cicala, G.; Greco, A. Fully Recyclable Bio-Based Epoxy Formulations Using Epoxidized Precursors from Waste Flour: Thermal and Mechanical Characterization. Polymers 2021, 13, 2768. [CrossRef]

- Cicala, G., Mannino, S.; La Rosa, A. D.; Banatao, D. R.; Pastine, S. J.; Kosinski, S. T.; Scarpa, F. Hybrid biobased recyclable epoxy composites for mass production. Polymer Composites 2018, 39(S4), E2217-E2225. [CrossRef]

- Guigo, N.; Sbirrazzuoli, N. Thermal analysis of biobased polymers and composites. In Handbook of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry 2018 (Vol. 6, pp. 399-429). Elsevier Science BV. [CrossRef]

-

ASTM D-2240; Standard Test Method for Rubber Property—Durometer Hardness. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021; 2021 Book of Standards Volume 09.01. p. 13.

-

ASTM D 7264/D 7264M. Standard test method for flexural properties of polymer matrix composite materials. West Conshohocken, PA 19428-2959, USA.

-

International Standard ISO 6721-11:2019(E). Plastics—Determination of Dynamic Mechanical Properties—Part 11: Glass Transition Temperature; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Bertomeu, D.; García-Sanoguera, D.; Fenollar, O.; Boronat, T.; Balart, R. Use of eco-friendly epoxy resins from renewable resources as potential substitutes of petrochemical epoxy resins for ambient cured composites with flax reinforcements. Polymer Composites 2012, 33(5), 683-692. [CrossRef]

- Di Mauro, C.; Malburet, S.; Genua, A.; Graillot, A.; Mija, A. Sustainable series of new epoxidized vegetable oil-based thermosets with chemical recycling properties. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21(9), 3923-3935. [CrossRef]

- Lascano, D.; Quiles-Carrillo, L.; Torres-Giner, S.; Boronat, T.; Montanes, N. Optimization of the Curing and Post-Curing Conditions for the Manufacturing of Partially Bio-Based Epoxy Resins with Improved Toughness. Polymers 2019, 11, 1354. [CrossRef]

- Umarfarooq, M. A.; Gouda, P. S.; Banapurmath, N. R.; Kittur, M. I.; Khan, T.; Parveez, B., ... Badruddin, I. A. Post-curing and fiber hybridization effects on mode-II interlaminar fracture toughness of glass/carbon/epoxy composites. Polymer Composites 2023, 44(8), 4734-4745. [CrossRef]

- MJ, M.; Ogihara, S. Damage behaviors in cross-ply cloth CFRP laminates cured at different temperatures. Mechanical Engineering Journal 2020, 7(5), 20-00383. [CrossRef]

- Chavan, V. R.; Dinesh, K. R.; Veeresh, K.; Algur, V.; Shettar, M. Influence of post curing on GFRP hybrid composite. In MATEC Web of Conferences 2018 (Vol. 144, p. 02011). EDP Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Xueshu, L. I. U.; Fei, C. H. E. N. A review of void formation and its effects on the mechanical performance of carbon fiber reinforced plastic. Engineering Transactions 2016, 64(1), 33-51. [CrossRef]

- Andrew, J. J.; Arumugam, V.; Santulli, C. Effect of post-cure temperature and different reinforcements in adhesive bonded repair for damaged glass/epoxy composites under multiple quasi-static indentation loading. Composite Structures 2016, 143, 63-74. [CrossRef]

- Goriparthi, B. K.; Suman, K. N. S.; Rao, N. M. Effect of fiber surface treatments on mechanical and abrasive wear performance of polylactide/jute composites. Composites Part A: applied science and manufacturing 2012, 43(10), 1800-1808. [CrossRef]

- Keusch, S.; Haessler, R. Influence of surface treatment of glass fibres on the dynamic mechanical properties of epoxy resin composites. Composites Part A: Applied Science and Manufacturing 1999, 30(8), 997-1002. [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, G.; Manyar, H. Production pathways of acetic acid and its versatile applications in the food industry. In Biomass 2020. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Dattilo, S.; Cicala, G.; Riccobene, P.M.; Puglisi, C.; Saitta, L. Full Recycling and Re-Use of Bio-Based Epoxy Thermosets: Chemical and Thermomechanical Characterization of the Recycled Matrices. Polymers 2022, 14, 4828. [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, A.D.; Blanco, I.; Banatao, D.R.; Pastine, S.J.; Björklund, A.; Cicala, G. Innovative Chemical Process for Recycling Thermosets Cured with Recyclamines® by Converting Bio-Epoxy Composites in Reusable Thermoplastic—An LCA Study. Materials 2018, 11, 353. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic of the cleavage mechanism induced by Recyclamine® hardener and conversion to the thermoplastic system (authors’ own figure).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the cleavage mechanism induced by Recyclamine® hardener and conversion to the thermoplastic system (authors’ own figure).

Figure 2.

Vacuum-assisted resin transfer molding system designed for the laminates fabrication.

Figure 2.

Vacuum-assisted resin transfer molding system designed for the laminates fabrication.

Figure 3.

Schematization of the chemical recycling process.

Figure 3.

Schematization of the chemical recycling process.

Figure 4.

TGA curves of bio-epoxy resins post-cured at different conditions: RT, PC100, PC140.

Figure 4.

TGA curves of bio-epoxy resins post-cured at different conditions: RT, PC100, PC140.

Figure 5.

Second heating scan DSC curves of bio-epoxy resins post-cured at different conditions: RT, PC100, PC140.

Figure 5.

Second heating scan DSC curves of bio-epoxy resins post-cured at different conditions: RT, PC100, PC140.

Figure 6.

Flexural test results on composite laminates at different post-curing regimes: (a) flexural strength, (b) elastic modulus, (c) load-strain curve for glass-reinforced laminates, and (d) flexural stress-strain curve for carbon-reinforced laminates.

Figure 6.

Flexural test results on composite laminates at different post-curing regimes: (a) flexural strength, (b) elastic modulus, (c) load-strain curve for glass-reinforced laminates, and (d) flexural stress-strain curve for carbon-reinforced laminates.

Figure 7.

Shore D hardness test results on composite laminates at different post-curing regimes.

Figure 7.

Shore D hardness test results on composite laminates at different post-curing regimes.

Figure 8.

SEM analysis on the composite over PC100 condition: (a) glass laminate (polished surface), (b) carbon laminate (polished surface), (c) detail on glass-resin interface (polished surface), and (d) fracture surface of carbon-based laminate.

Figure 8.

SEM analysis on the composite over PC100 condition: (a) glass laminate (polished surface), (b) carbon laminate (polished surface), (c) detail on glass-resin interface (polished surface), and (d) fracture surface of carbon-based laminate.

Figure 9.

SEM analysis on the carbon-based composite laminate over PC140 condition: detail on fiber-pull-out.

Figure 9.

SEM analysis on the carbon-based composite laminate over PC140 condition: detail on fiber-pull-out.

Figure 10.

DMA test results: tan δ vs. temperature for plain resin, glass, and carbon laminates post-cured under PC100 regime.

Figure 10.

DMA test results: tan δ vs. temperature for plain resin, glass, and carbon laminates post-cured under PC100 regime.

Figure 11.

TGA on recovered polymer from chemical recycling.

Figure 11.

TGA on recovered polymer from chemical recycling.

Figure 12.

DSC on recovered polymer from chemical recycling.

Figure 12.

DSC on recovered polymer from chemical recycling.

Figure 13.

SEM analysis on recycled fibers: (a) glass and (b) carbon fibers.

Figure 13.

SEM analysis on recycled fibers: (a) glass and (b) carbon fibers.

Table 1.

T5% and Tmax values determined by TGA.

Table 1.

T5% and Tmax values determined by TGA.

| Post-curing condition |

T5% (°C) |

Tmax (°C) |

| RT |

197.4 |

349.4 |

| PC100 |

194.7 |

345.5 |

| PC140 |

178.9 |

342.5 |

Table 2.

Tg values determined by DSC analysis.

Table 2.

Tg values determined by DSC analysis.

| Post-curing condition |

Tg (°C) |

| RT |

76.6 |

| PC100 |

72.7 |

| PC140 |

50.9 |

Table 3.

DMA test results: Tg and tan δ peak-values.

Table 3.

DMA test results: Tg and tan δ peak-values.

| Sample |

Tg (°C) |

tan δ peak |

| Resin PC100 |

68.4 |

0.71 |

| Glass PC100 |

73.1 |

0.35 |

| Carbon PC100 |

69.5 |

0.57 |

Table 4.

Results of the chemical recycling process on composites.

Table 4.

Results of the chemical recycling process on composites.

| Treated sample |

Starting

mass

(g) |

Recovered fibers

(g) |

Recovered polymer

(g) |

Recovery

yield

(%) |

| Glass composite |

10.97 |

7.05 |

3.43 |

95.5 |

| Carbon composite |

10.84 |

5.85 |

4.86 |

98.8 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).