1. Introduction

Cosmetic formulations, encompassing solutions, emulsions, and solids, are designed for diverse body care applications, ranging from shampoos and conditioners to face and body creams. These products must meet several critical requirements. First and foremost, they must be non-toxic and effective for their intended use. Beyond safety and efficacy, the cosmetic industry prioritizes formulations that offer a pleasant skin feel for the consumer. Furthermore, there is a growing demand for “green” and eco-friendly products, emphasizing sustainable ingredients and environmentally conscious manufacturing processes. This includes considerations like biodegradability, reduced environmental impact, and the use of renewable resources [

1,

2]. Thus the use of sustainable and eco-friendly ingredients is mandatory, but the preservation of the desired properties of the final product is challenging. One of the major concerns regards synthetic polymers, which are usually employed as thickeners and rheological modifiers, increasing the viscosity of products and improving their texture. One of the challenges of the cosmetic industries is to find natural alternatives to replace these non-eco-friendly ingredients [

3,

4], preserving the desirable sensory characteristics.

To find sustainable replacements for synthetic polymers, several strategies are being explored. One approach is using natural polymers, such as polysaccharides [

5,

6] either individually or in mixtures. While using naturally derived polymers like polysaccharides is a logical step towards sustainability, the passage points out a significant hurdle. Matching the performance characteristics, specifically the thickening and gelling properties, of well-established synthetic polymers remains a challenge. This suggests that while polysaccharides offer a bio-based solution, they may not yet be able to fully replicate the desired functionality in many applications. Further research and modification of these natural polymers are likely needed.

Another promising avenue involves small, self-assembling molecules (called low molecular weight gerlators, LMGWs) [

7,

8] that form fibrous networks capable of trapping large amounts of solvent, thus functioning as thickeners and gelling agents. This approach presents a more innovative and less explored alternative. LMWGs are small molecules that can self-assemble into three-dimensional networks within a solvent. This self-assembly is driven by non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonds, van der Waals forces, and π-π stacking. These networks can trap substantial amounts of solvent, effectively thickening the material and creating gels. LMWGs are relatively underutilized in cosmetics, suggesting a significant potential for future development and application [

9,

10].

LMWGs hold additional advantages, as they offer a high degree of flexibility. Researchers can modify their chemical structure and manipulate the external conditions (solvent, concentration, trigger) to fine-tune the gel’s properties. This control allows for the design of LMWGs tailored to specific applications and desired sensory attributes. Moreover, the design of LMWGs often focuses on incorporating specific molecular groups (moieties and functional groups) that facilitate the non-covalent interactions necessary for self-assembly and gel formation.

Finally, a critical aspect of LMWG gelation is the control of solubility. The gelator is typically designed to be partially soluble in the chosen solvent. A trigger (e.g., a change in pH) is then used to reduce the solubility, causing the LMWG molecules to aggregate and form the gel network [

11,

12]. The passage provides a specific example of a pH-change method, where a base is used to initially dissolve a carboxylic acid-containing LMWG, and then an acid is added to reduce the pH below the pK

a of the gelator, thus indicing the protonation and the self-assembly of the gelator and consequently the solution gelation [

13,

14,

15].

In essence, LMWGs represent a promising, albeit under-explored, avenue for developing sustainable alternatives to synthetic polymers in cosmetics and potentially other fields. Their tunability, self-assembly mechanism, and the ability to trigger gelation through changes in external conditions offer significant advantages for designing materials with tailored properties. The fact that they are relatively underutilized suggests a rich area for future research and development.

LMWGs can often be obtained by short amino acids sequences, even just dipeptides, or from single amino acids variously derivatized, for example with fatty acids [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. In the last case their structure resembles exactly the one of surfactants: a hydrophilic head (the amino acid moiety, often with the carboxylic acid group free and charged) and a long hydrophobic tail (the fatty acid) [

21,

22,

23]. Some examples already reported the ability of such structures to behave as gelators or at least viscosity enhancers, alone [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28] and in combination with polymers [

29,

30,

31]. Other works also show the beneficial self-assembly of surfactants with LMWGs as an approach towards the formation of complex architectures, such as micelles or vesicles embedded in a gel matrix, or even interpenetrating networks. [

32,

33,

34,

35] These compounds offer the possibility to have LMWGs which are easily synthesised, biocompatible, biodegradable, non-toxic for the environment, and sometimes already tested and used in commercially available products. In our work, the ability of ten surfactants already on the market was tested to form gels through self-assembly at a final pH of 5, as it is the physiological pH of the human skin and sculp. As most surfactants are not gelators, we added (

S)-

N-(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-3,4-bis(benzyloxy)-phenylalanine (Boc-L-Dopa(Bn)

2-OH), one of our previously reported LMWGs, to investigate the possibility of forming gels also with these ingredients. Indeed, Boc-L-Dopa(Bn)

2-OH was chosen for these trials due to its ability to self-assemble in presence of a variety of additives and species (crystals [

36], other peptides [

37], antioxidants [

38], fragrances [

39,

40]), proving to be a very robust gelator.

Since anionic surfactants are quite aggressive [

41,

42], we studied the behaviour of mixtures containing also cocamidopropyl betaine (CAPB), as this ingredient is added very often to commercial cosmetics to increase cleansing gentleness as it is mild on the skin [

43].

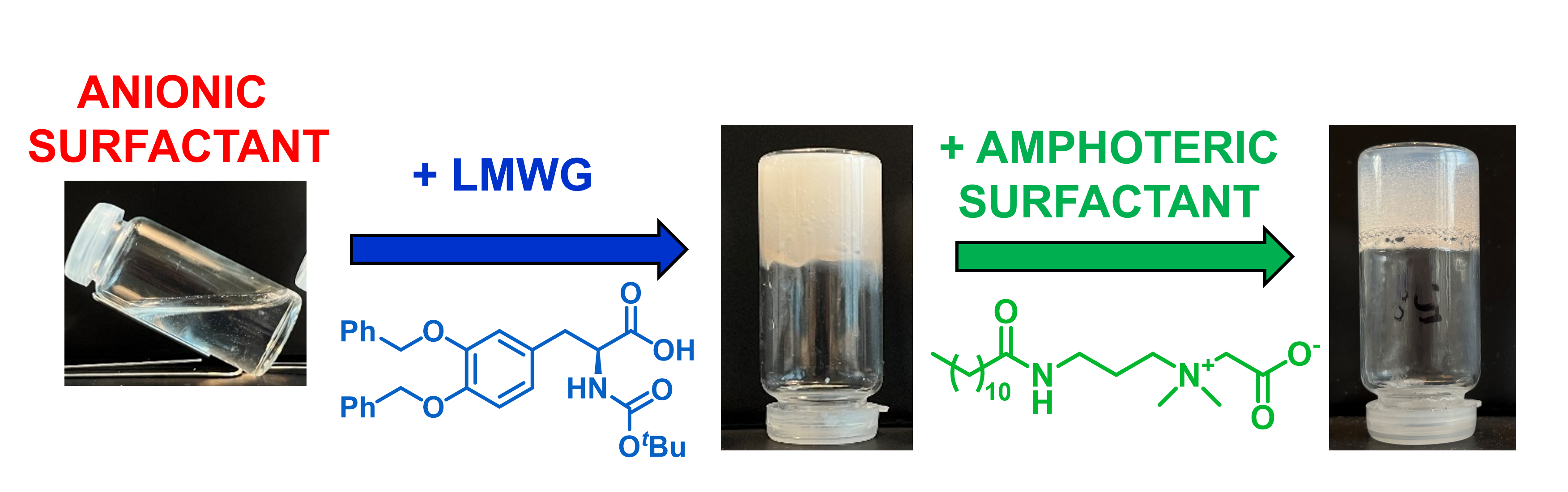

2. Results and Discussion

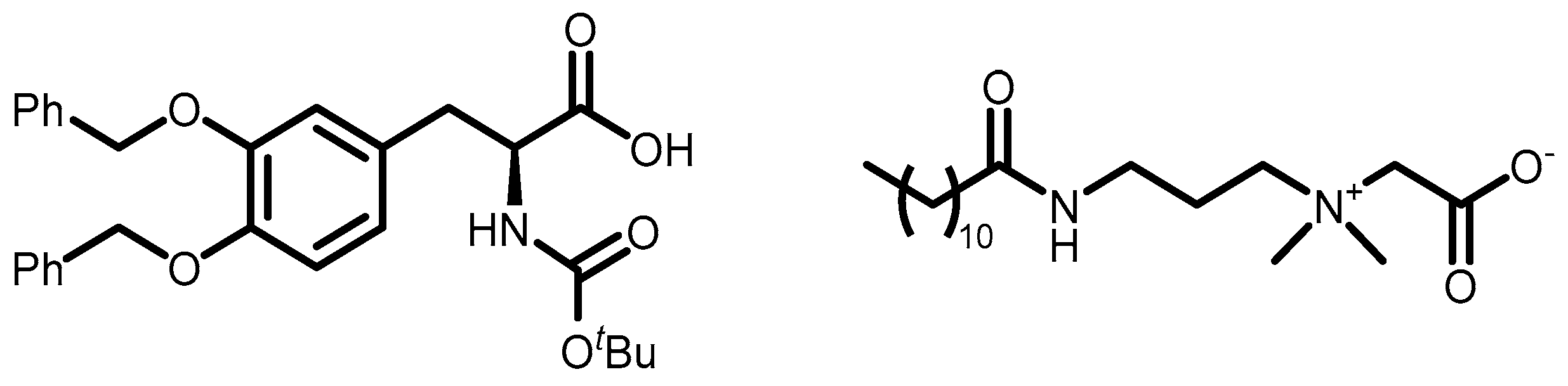

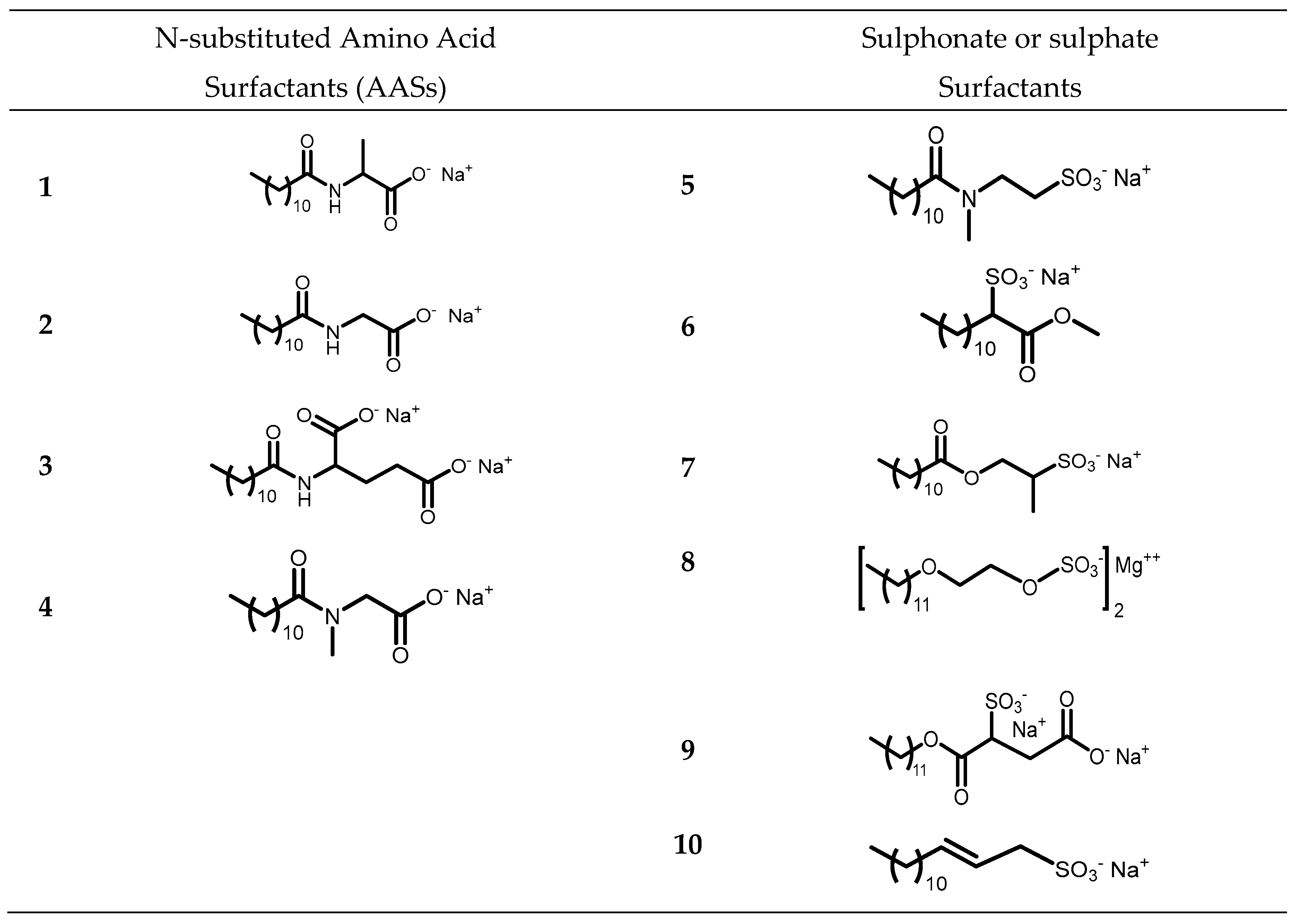

The aim of this work is to study the formation of gels from solutions containing commercial samples of surfactants listed in

Table 1, Boc-L-Dopa(Bn)

2-OH and of CABP (

Figure 1). Ten different anionic surfactants were chosen, as they represent the main classes of primary anionic surfactants often used in cosmetic formulations and allow for a relatively wide range of concentrations within their specification limits. The chemical structure of the main component of each surfactant are reported in

Table 1, as most commercial surfactants contain small amounts of other component holding fatty acids with different chain length (C12, C14, C16). Each surfactant (1-10) has a specific concentration range. For this reason, different amounts were withdrawn with a pipette or weighted in an analytical balance to achieve a 10% w/v active matter in solution in any case. The average value of the active matter and the initial pH values are reported in

Table S1.

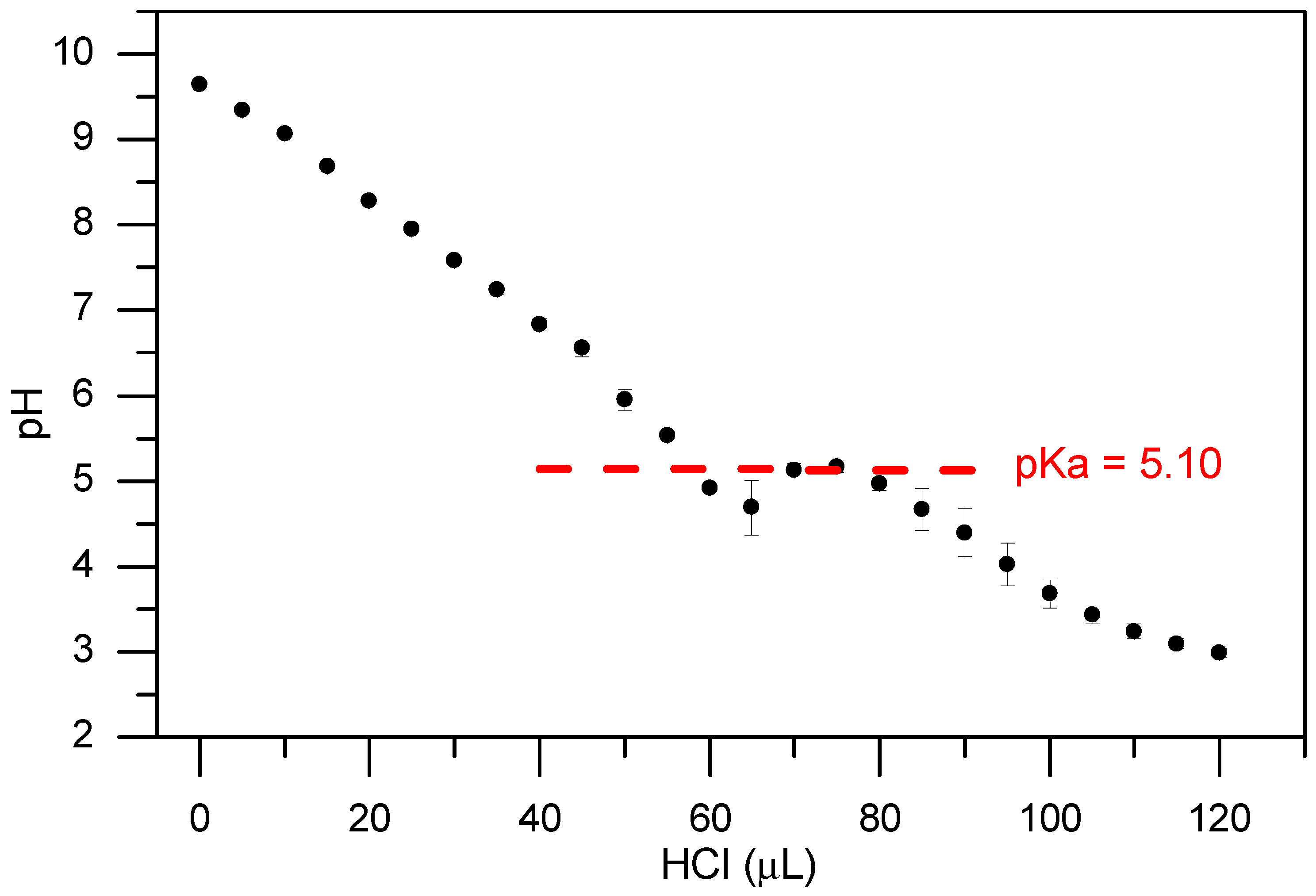

Surfactants 1-4 are N-substituted Amino Acid Surfactants (AASs). These molecules possess a carboxylate group which makes them sensitive to the pH of the formulations, as the average pK

a of carboxylic acid is around 4-5. In addition, surfactants 1-3 hold a secondary amide group that enables them to form additional hydrogen bonding. Anionic surfactants 5-10 contain a sulphonate or a sulphate group which requires more extreme pH values to be protonated, making them less affected by pH modification, as the pK

a of the corresponding acids is lower than -5. The precise analysis of the pK

a of the surfactant is affected by the fact that they are commercial mixtures in solution, so their pK

a was not measured. In contrast, we could precisely measure pK

a of Boc-L-Dopa(Bn)

2-OH as it is a single component. The analysis was performed in a 0.2% concentration, where the molecule is fully soluble giving a pK

a = 5.1. The result is reported in

Figure 2.

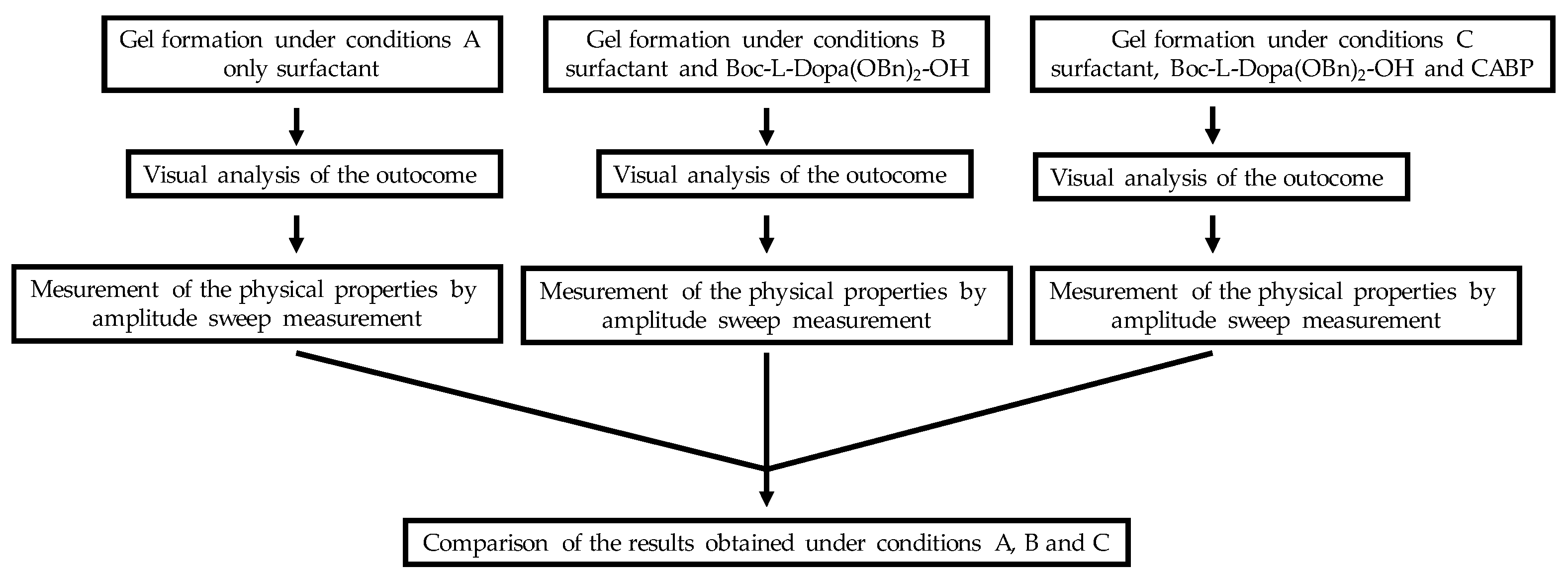

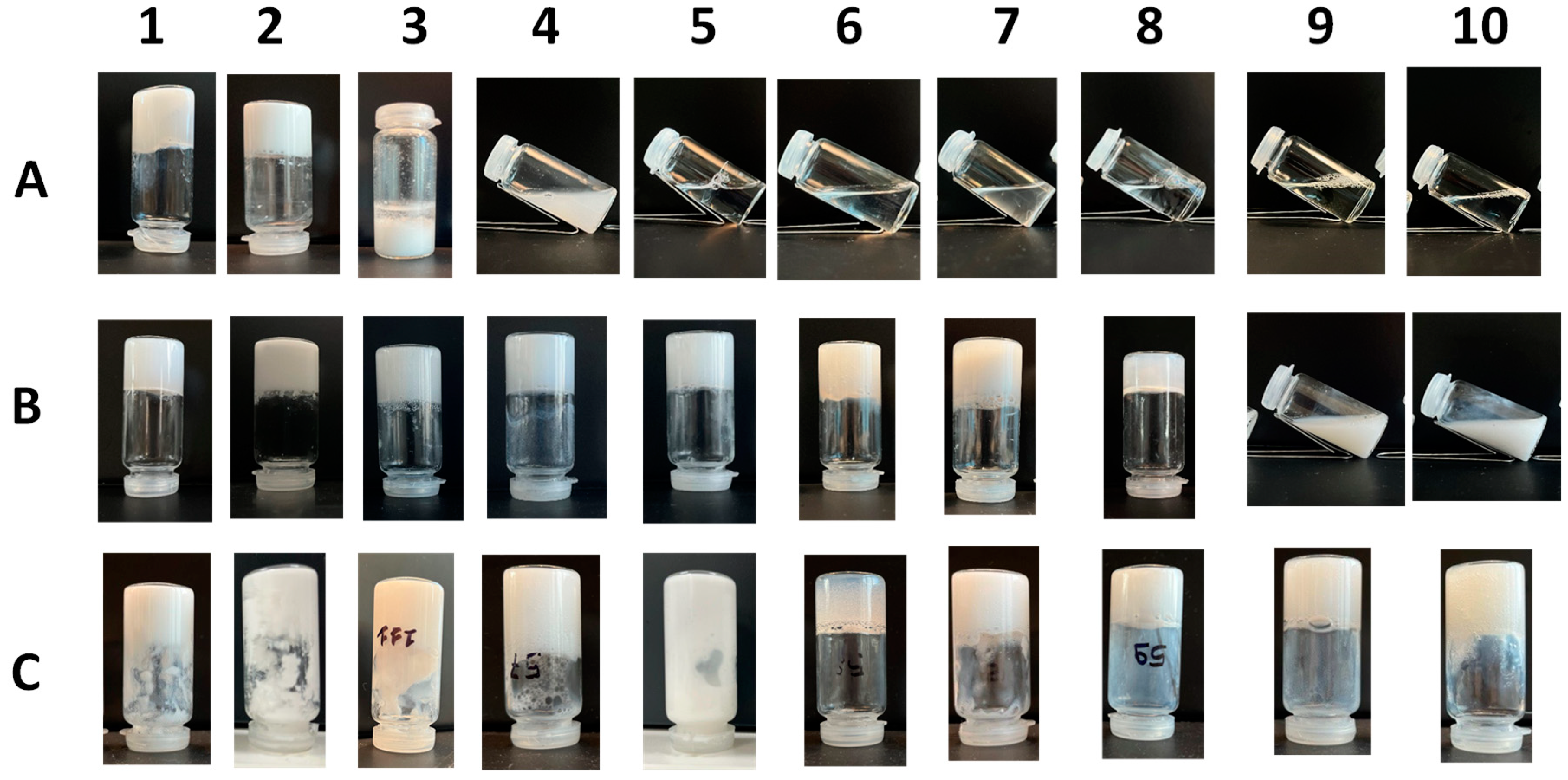

Ten different samples (1A-10A) were prepared using the ten surfactants under conditions A: the surfactant (10% w/v) and water were mixed with a magnetic stirrer for 15 minutes, then lactic acid (45% w/v) was added to reach a final pH of 5, while mixing with a magnetic stirrer. This pH was chosen because it is compatible with most cosmetic formulations and allows the protonation of carboxylic acids, thus favouring the molecules self-assembly and the consequent mixture gelation. Lactic acid was chosen because it is completely water soluble, cheap, biocompatible, and often used in cosmetic products

[44,45].

Then we prepared ten additional samples (1B-10B) under conditions B: the surfactant (10% w/v), Boc-L-Dopa(Bn)2-OH (1% w/v) and water were mixed with a magnetic stirrer for 15 minutes, then lactic acid 45% w/v was added to adjust pH to 5.

Finally, another set of tests was done following conditions C, by using 10% w/v of anionic surfactant active matter together with Boc-L-Dopa(Bn)2-OH (1% w/v) and cocamidopropyl betaine (4.5% w/v) (samples 1C-10C).

The results are summarized in

Table 1 and are in agreement with the analysis of pK

a values of the surfactants.

Under condition A, samples 1A and 2A form a gel at pH 5, while 3A forms a precipitate. In any case a modification of the mixture was obtained at pH 5 due to the protonation of the carboxylate. A totally different outcome was obtained with surfactants 4-10. In all these cases, the sufactants have much lower pKa (about -5), so no protonation take places, producing no mixture modification. Indeed, as all the sample remained as a solution, with no appreciable viscosity.

The results are very different at pH 5, when Boc-L-Dopa(Bn)2-OH is added in 1% w/v concentration (condition B). Under these conditions, the gelation occurred for samples 1B-8B, while only samples 9B and 10B remained a solution. This outcome confirms the strong gelation ability of the gelator, when the carboxylate group is protonated, even in complex mixtures that in principle could interfere with the gelification process.

Then CABP at 4.5% w/v concentration was added to the mixture (condition C) and a new set of samples was prepared (1C-10C). The addition of CABP has a very low impact on the appearance of the samples, as all the samples are gels.

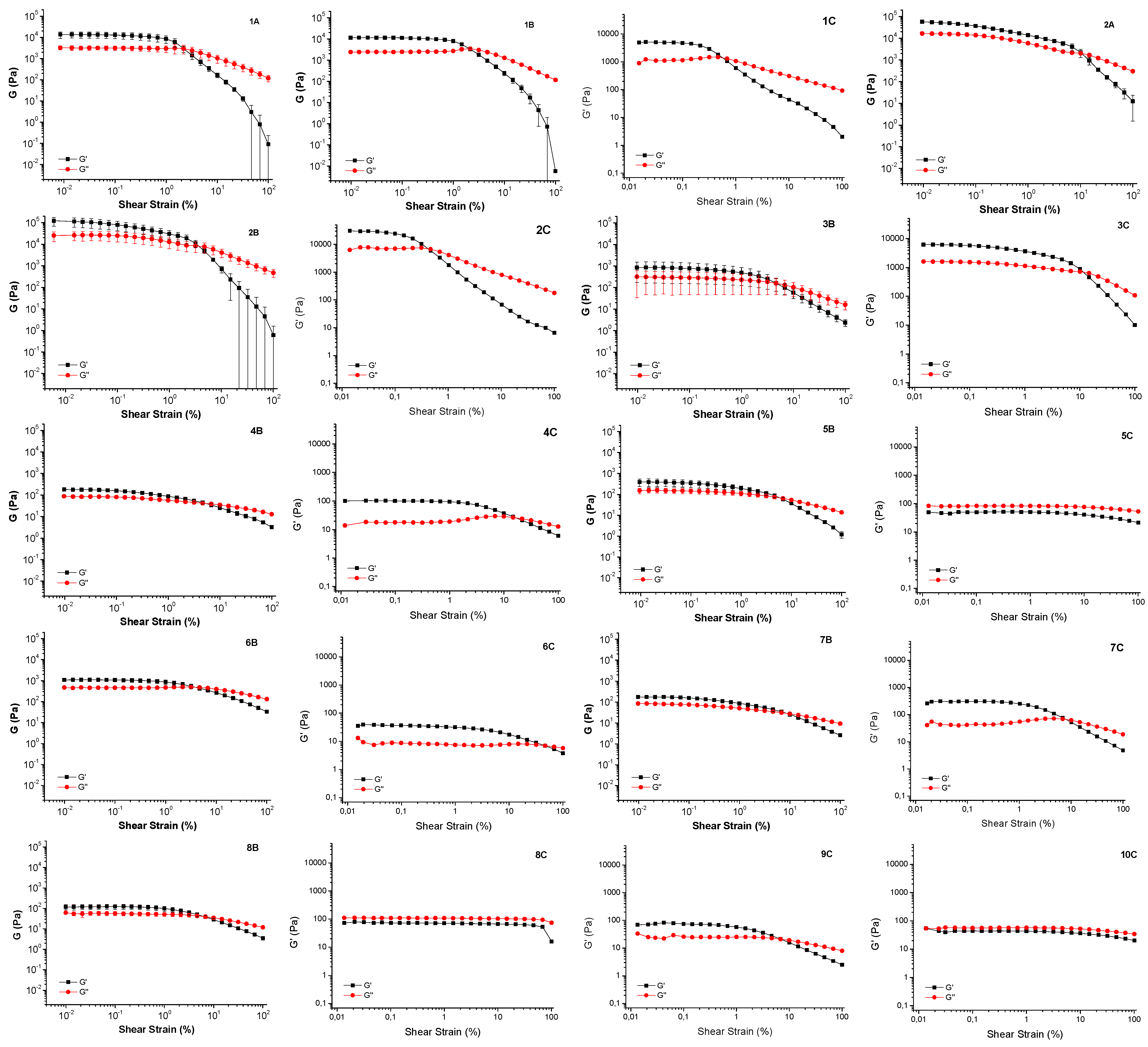

Rheological analysis provided a detailed characterization of the samples mechanical properties, confirming or refuting gel formation and offering insights into material strength and elasticity. Gel formation was determined by analyzing the amplitude sweep, measuring the storage modulus (G’) and loss modulus (G”) in Pascals. G’, representing the elastic response, and G”, representing the viscous response, were compared. A gel state is indicated when G’ exceeds G”.[

46,

47] Amplitude sweep measurements were performed on all samples exhibiting gel-like behavior, characterized by their non-flow properties and ability to support their own weight when inverted.

Results obtained with rheological analysis are shown in

Figure 4 and in

Table 2. Samples

1A and

2A are strong gels with a G’ modulus value of about 10

4 Pa. The addition of Boc-L-Dopa(Bn)

2-OH (samples

1B and

2B) does not significatively modifies the results, as

1B is slightly weaker than

1A, while

2B is slightly stronger than

2A. The results obtained with the addition of CABP are very similar, with a small decrease in the G’ value for both samples

1C and

2C. These results confirm that

N-substituted amino acid surfactants

1 and

2 may behave as good gelator alone or in mixtures at pH 5.

Moving to surfactants 3-10, the addition of only 1% of the Boc-L-Dopa(Bn)2-OH ends up into the formation of white gels in six samples out of eight, and this result is confirmed by amplitude sweep analysis, as in any case G’ is higher than G”, although often the strength of the gels is much reduced, as G’ never overtakes values of 103 Pascal. In these samples there is not a synergistic effect between the surfactant and the gelator, as previously found, because the starting surfactant solutions are completely liquid, so the gel strength is entirely due to the gelator effect, and this accounts for the reduced gel strength.

Additionally, when the same formulations are prepared adding CAPB to the mixture to better mimk a cosmetic formulation, all samples appear as gels, although generally the G’ value decreases, overtaking 102 Pascal only for samples 3C and 7C , while for several samples (5C, 6C, 8C, 9C, 10C) the elastic modulus is less than 100 Pa. Moreover, in the case of 5C, 8C, and 10C the G” value is slightly higher than G’, so these samples should be more correctly defined as viscous liquids and not gels, although their appearance is very similar and they can still be useful for a variety of cosmetic products. To explain this outcome, the complex viscosity (η*) of the three samples was also reported. In all the cases the values of the C samples is very close to the values of the B samples, thus showing that all these samples are borderline between gels (G’ > G”) and viscous liquid (G” > G’). Nonetheless, it can be stated that any case the addition of the gelator highly affects the rheology of the surfactants solutions, converting almost all of the samples from liquids to gels, and only three samples to viscous solutions, thus increasing the viscosity.

3. Conclusions

This manuscript details the preparation and analysis of thirty samples containing commercial surfactants commonly used in cosmetic formulations at pH 5 that is the physiological pH of the human skin and sculp. The study investigates the impact of adding a small percentage of an efficient low-molecular-weight gelator (LMWG) on the appearance and consistency of these surfactant mixtures, focusing on its potential as a rheological modifier and viscosity enhancer. Specifically, 1% w/V of the LMWG Boc-L-Dopa(Bn)2-OH was added to two sets of aqueous solutions: one containing ten different anionic surfactants, and the other containing the same anionic surfactants plus cocamidopropyl betaine, a zwitterionic surfactant known for its mildness, to better mimik a cosmetic formulation. In the majority of cases, the addition of just 1% of the gelator induced gelation, demonstrating its ability to self-assemble at pH 5, even within these complex mixtures. The rheological analysis (amplitude sweep tests) confirmed the gel-like behavior of most samples, with the storage modulus (G’) exceeding the loss modulus (G”) in almost all cases.

This preliminary work suggests a promising new approach for developing more sustainable cosmetic formulations by replacing synthetic polymer with versatile and biodegradable LMWGs. This substitution addresses growing concerns about the environmental impact of microplastics and non-biodegradable ingredients commonly used in cosmetics. By leveraging the unique properties of LMWGs, such as their ability to form diverse structures and their inherent biodegradability, we aim to create cosmetic products with improved sustainability profiles without compromising performance or sensory attributes. Further research will focus on optimizing the formulation and characterizing the long-term stability and efficacy of these LMWG-based cosmetic products, paving the way for a wider adoption of bio-based materials in the personal care industry.

4. Materials and Methods

The anionic surfactants Eversoft™ ACS-30S was purchased from Sino Lion USA; Galsoft SCG was purchased from Galaxy Surfactants Ltd.; Pureact WS Conc, Iselux

® and NANSA

® LSS 38/AV were purchased from Innospec Performance Chemicals; STEPAN-MILD

® PCL-BA was purchased from STEPAN EUROPE S.A.S; PROTELAN AGL 95, SETACIN 103 SPEZIAL NP and ZETESOL MG-FS were purchased from Zschimmer & Schwarz Italiana S.p.A. All the solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Boc-L-Dopa(Bn)

2-OH was synthesized following a multistep procedure in solution as reported in the literature [

48,

49] (Scheme S1).

Figure 5.

Flow chart of the experimental procedures.

Figure 5.

Flow chart of the experimental procedures.

pH meter XS pH 8 PRO Basic (XS Instruments, Carpi (MO), Italy) equipped with XS Sensor Standard T BNC was used to measure the samples pH.

The rheological analyses were performed using an Anton Paar (Graz, Austria) MCR 92 rheometer. A cone (d = 50 mm)/plane measuring system was used, setting a gap of 0.098 mm. Oscillatory amplitude sweep experiments were performed at 25 °C using a Peltier control system and the data points were collected (γ: 0.01 – 100 %) using a constant angular frequency of 1 Hz.

Gel preparation - Each surfactant in the study has a specific concentration range. For this reason, different amounts were withdrawn with a pipette or weighted in an analytical balance to achieve a 10% active matter in solution (

Table S1). Cosmetic raw materials generally allow for a relatively wide range within their specification limits. The average value of the active matter, reported below (% w/v), was selected to determine the amount of raw material to use in each test. Each surfactant was assigned a number from 1 to 10.

Samples A contained 10% surfactant

Samples B contained 10% surfactant + 1% Boc-L-DOPA(Bn)₂-OH (equivalent to 0.105 mmol for 5 mL of sample)

Samples C contained 10% surfactant + 1% Boc-L-DOPA(Bn)₂-OH and 4.5% Cocamidopropyl betaine

Details for the preparation of samples A, with surfactants 1-10 - All samples were prepared inside 10 mL glass squat vials, on a total volume of 5 mL. The surfactant (10%) and water were mixed with a magnetic stirrer for 15 minutes. Lactic acid 45%) is added to reach a final pH of 5, while mixing with a magnetic stirrer, since the simple swirling leads to non-homogeneous samples. Only in the case of Zetesol MG-FS (sample 8A) the initial pH was too low (4.5) that no acid was added, and NaOH was used instead to bring the pH to the final value of 5.

Details for the preparation of samples B, with surfactants 1-10 and Boc-L-Dopa(Bn)2-OH - All samples were prepared inside 10 mL glass squat vials, on a total volume of 5 mL. The gelator (1.0% w/v) was suspended in osmotic H2O, with the surfactant (10% w/v) and a volume of NaOH (7.5% w/v) to reach pH 10. The mixture was stirred and sonicated until the complete solubilization of the gelator. Lactic acid (45%) was added to reach a final pH of 5, while mixing with a magnetic stirrer for 1 minute, since the simple swirling leads to non-homogeneous samples.

Details for the preparation of samples C, with surfactants 1-10, Boc-L-Dopa(Bn)2-OH and CAPB - All samples were prepared inside 10 mL glass squat vials, on a total volume of 5 mL. The gelator (1.0% w/v) was suspended in osmotic H2O, with the surfactant (10% w/v) and a volume of NaOH (7.5% w/v) to reach a starting pH of 10. The mixture was stirred and sonicated until the complete solubilization of the gelator, and after that the amphoteric surfactant CAPB (Cocamidopropyl betaine, 4.5% w/v) was added. Lactic acid (45%) was added, reaching a final pH of 4.2. Mixing was achieved by swirling for liquid samples and by using a spatula for the more viscous ones.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Scheme S1. Scheme of the Synthesis of Boc-L-DOPA(Bn)2-OH, Table S1. Commercial surfactants used, Figure S1. Photographs of gelation of samples 1A-10A, Figure S2. Photographs of gelation of samples 1B-10B, Figure S3. Comparison between samples A, B and C, Amplitude sweep of gel samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G.; methodology, S.C.; validation, S.C. and F.C.; formal analysis, S.C. and F.C.; investigation, S.C.; resources, C.T.; data curation, S.C. and F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C., C.T. and D.G.; writing—review and editing, C.T. and D.G.; visualization, D.G.; supervision, C.T.; project administration, C.T.; funding acquisition, C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its

Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgements

We thank Alessandra Mori and Paolo Goi from Davines S.p.A. (Via Don Angelo Calzolari 55/A - 43126 Parma – Italy) for valuable discussions and hints. We also thank Davines S.p.A. for providing samples of commercial surfactants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Boc-L-Dopa(Bn)2-OH |

(S)-N-(tert-butyloxycarbonyl)-3,4-bis(benzyloxy)-phenylalanine |

| LMWG |

Low molecular weight gelator |

| CABP |

Cocamidopropyl betaine |

| AAS |

N-substituted Amino Acid Surfactant |

References

- de Castro, M.; Roque, C.S.; Loureiro, A.; Guimarães, D.; Silva, C.; Ribeiro, A.; Cavaco-Paulo, A.; Noro, J. Exploring Bio-Based Alternatives to Cyclopentasiloxane: Paving the Way to Promising Silicone Substitutes. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2025, 707, 135915. [CrossRef]

- Chadha Gagan Deep and Singh, R. Circular Beauty: Sustainable Resource Recovery and Waste Management in the Cosmetic Industry. In Proceedings of the Technological Advancements in Waste Management: Challenges and Opportunities; Kumar Vipin and Dubey, B.K. and D.Y.K., Ed.; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2025; pp. 379–399.

- Reichmuth, N.; Huber, P.; Ott, R. High-Acyl Gellan Gum as a Functional Polyacrylate Substitute in Emulsions High-Acyl Gellan Gum as a Functional Polyacrylate Substitute in Emulsions. SOFW Journal 2019, 145, 36–39.

- Tafuro, G.; Costantini, A.; Baratto, G.; Francescato, S.; Semenzato, A. Evaluating Natural Alternatives to Synthetic Acrylic Polymers: Rheological and Texture Analyses of Polymeric Water Dispersions. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 15280–15289. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Cheng, N.; Fang, D.; Wang, H.; Rahman, F.-U.; Hao, H.; Zhang, Y. Recent Advances on Application of Polysaccharides in Cosmetics. Journal of Dermatologic Science and Cosmetic Technology 2024, 1, 100004. [CrossRef]

- Tafuro, G.; Costantini, A.; Baratto, G.; Francescato, S.; Busata, L.; Semenzato, A. Characterization of Polysaccharidic Associations for Cosmetic Use: Rheology and Texture Analysis. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 62. [CrossRef]

- Hirst, A.R.; Coates, I.A.; Boucheteau, T.R.; Miravet, J.F.; Escuder, B.; Castelletto, V.; Hamley, I.W.; Smith, D.K. Low-Molecular-Weight Gelators: Elucidating the Principles of Gelation Based on Gelator Solubility and a Cooperative Self-Assembly Model. J Am Chem Soc 2008, 130, 9113–9121. [CrossRef]

- Van Esch, J.H. We Can Design Molecular Gelators, but Do We Understand Them? Langmuir 2009, 25, 8392–8394. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.D.; Kershaw Cook, L.J.; Slater, A.G.; Yufit, D.S.; Steed, J.W. Scrolling in Supramolecular Gels: A Designer’s Guide. Chemistry of Materials 2024, 36, 2799–2809. [CrossRef]

- Morris, K.L.; Chen, L.; Rodger, A.; Adams, D.J.; Serpell, L.C. Structural Determinants in a Library of Low Molecular Weight Gelators. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 1174–1181. [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Smith, A.M.; Collins, R.F.; Ulijn, R. V.; Saiani, A. Fmoc-Diphenylalanine Self-ASsembly Mechanism Induces Apparent PK a Shifts. Langmuir 2009, 25, 9447–9453. [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.J.; Butler, M.F.; Frith, W.J.; Kirkland, M.; Mullen, L.; Sanderson, P. A New Method for Maintaining Homogeneity during Liquid-Hydrogel Transitions Using Low Molecular Weight Hydrogelators. Soft Matter 2009, 5, 1856–1862. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Raeburn, J.; Sutton, S.; Spiller, D.G.; Williams, J.; Sharp, J.S.; Griffiths, P.C.; Heenan, R.K.; King, S.M.; Paul, A.; et al. Tuneable Mechanical Properties in Low Molecular Weight Gels. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 9721–9727. [CrossRef]

- Okesola, B.O.; Vieira, V.M.P.; Cornwell, D.J.; Whitelaw, N.K.; Smith, D.K. 1,3:2,4-Dibenzylidene-d-Sorbitol (DBS) and Its Derivatives-Efficient, Versatile and Industrially-Relevant Low-Molecular-Weight Gelators with over 100 Years of History and a Bright Future. Soft Matter 2015, 11, 4768–4787. [CrossRef]

- Afrasiabi, R.; Kraatz, H.-B. Sonication-Induced Coiled Fibrous Architectures of Boc-L-Phe-L-Lys(Z)-OMe. Chemistry – A European Journal 2013, 19, 1769–1777. [CrossRef]

- Cenciarelli, F.; Pieraccini, S.; Masiero, S.; Falini, G.; Giuri, D.; Tomasini, C. Experimental Correlation between Apparent PKa and Gelation Propensity in Amphiphilic Hydrogelators Derived from L-Dopa. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 5058–5067. [CrossRef]

- Sunil Singh, R. Supramolecular Gels from Bolaamphiphilic Molecules. J Mol Liq 2024, 394. [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Dasgupta, A.; Roy, S.; Mitra, R.N.; Debnath, S.; Das, P.K. Water Gelation of an Amino Acid-Based Amphiphile. Chemistry - A European Journal 2006, 12, 5068–5074. [CrossRef]

- Giuri, D.; Zanna, N.; Tomasini, C. Low Molecular Weight Gelators Based on Functionalized L-Dopa Promote Organogels Formation. Gels 2019, 5, 27. [CrossRef]

- Mondal, B.; Gupta, V.K.; Hansda, B.; Bhoumik, A.; Mondal, T.; Majumder, H.K.; Edwards-Gayle, C.J.C.; Hamley, I.W.; Jaisankar, P.; Banerjee, A. Amino Acid Containing Amphiphilic Hydrogelators with Antibacterial and Antiparasitic Activities. Soft Matter 2022, 18, 7201–7216. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ménard-Moyon, C.; Bianco, A. Self-Assembly of Amphiphilic Amino Acid Derivatives for Biomedical Applications. Chem Soc Rev 2022, 51, 3535-3560. [CrossRef]

- Restu, W.K.; Nishida, Y.; Kataoka, T.; Morimoto, M.; Ishida, K.; Mizuhata, M.; Maruyama, T. Palmitoylated Amino Acids as Low-Molecular-Weight Gelators for Ionic Liquids. Colloid Polym Sci 2017, 295, 1109–1116. [CrossRef]

- Veloso, S.R.S.; Rosa, M.; Diaferia, C.; Fernandes, C. A Review on the Rheological Properties of Single Amino Acids and Short Dipeptide Gels. Gels 2024, 10, 507. [CrossRef]

- Restu, W.K.; Nishida, Y.; Kataoka, T.; Morimoto, M.; Ishida, K.; Mizuhata, M.; Maruyama, T. Palmitoylated Amino Acids as Low-Molecular-Weight Gelators for Ionic Liquids. Colloid Polym Sci 2017, 295, 1109–1116. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Huang, X. A Low Molecular Weight Gel Formed by Cationic Surfactant 1-Dodecylpyridinium Bromide in Acetone/Water: Its Characterisation and Implication for Enzyme Immobilisation. Supramol Chem 2015, 27, 21–27. [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Asad Ayoubi, M.; Lu, W.; Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Wang, W. A Unique Thermo-Induced Gel-to-Gel Transition in a PH-Sensitive Small-Molecule Hydrogel. Sci Rep 2017, 7. [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, S.R. Distinct Character of Surfactant Gels: A Smooth Progression from Micelles to Fibrillar Networks. Langmuir 2009, 25, 8382–8385. [CrossRef]

- Oda, R.; Huc, I.; Candau, S.J. Gemini Surfactants as New, Low Molecular Weight Gelators of Organic Solvents and Water. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 1998, 37, 2689–2691. [CrossRef]

- Akin-Ige, F.; Amin, S. Stimuli-Responsive Bio-Based Surfactant-Polymer Gels. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2024, 703. [CrossRef]

- Leung, P.S.; Goddard, E.D. Gels from Dilute Polymer/Surfactant Solutions; 1991, 7, 608 – 609. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Concheiro, A. Effects of Surfactants on Gel Behavior. American Journal of Drug Delivery 2003, 1, 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Brizard, A.M.; Stuart, M.C.A.; van Esch, J.H. Self-Assembled Interpenetrating Networks by orthogonal Self Assembly of Surfactants And. Faraday Discuss 2009, 143, 345–357. [CrossRef]

- Heeres, A.; Van Der Pol, C.; Stuart, M.; Friggeri, A.; Feringa, B.L.; Van Esch, J. Orthogonal Self-Assembly of Low Molecular Weight Hydrogelators and Surfactants. J Am Chem Soc 2003, 125, 14252–14253. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.L.; Liu, X.Y.; Strom, C.S.; Xiong, J.Y. Engineering of Small Molecule Organogels by Design of the Nanometer Structure of Fiber Networks. Advanced Materials 2006, 18, 2574–2578. [CrossRef]

- Aramaki, K.; Koitani, S.; Takimoto, E.; Kondo, M.; Stubenrauch, C. Hydrogelation with a Water-Insoluble Organogelator-Surfactant Mediated Gelation (SMG). Soft Matter 2019, 15, 8896–8904. [CrossRef]

- Giuri, D.; Jurković, L.; Fermani, S.; Kralj, D.; Falini, G.; Tomasini, C. Supramolecular Hydrogels with Properties Tunable by Calcium Ions: A Bio-Inspired Chemical System. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2019, 2, 5819–5828. [CrossRef]

- Shariati Pour, S.R.; Oddis, S.; Barbalinardo, M.; Ravarino, P.; Cavallini, M.; Fiori, J.; Giuri, D.; Tomasini, C. Delivery of Active Peptides by Self-Healing, Biocompatible and Supramolecular Hydrogels. Molecules 2023, 28, 2528. [CrossRef]

- Toronyi, A.Á.; Giuri, D.; Martiniakova, S.; Tomasini, C. Low-Molecular-Weight Gels as Smart Materials for the Enhancement of Antioxidants Activity. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 38. [CrossRef]

- Cenciarelli, F.; Falini, G.; Giuri, D.; Tomasini, C. Controlled Lactonization of O-Coumaric Esters Mediated by Supramolecular Gels. Gels 2023, 9, 350. [CrossRef]

- Nicastro, G.; Black, L.M.; Ravarino, P.; D’Agostino, S.; Faccio, D.; Tomasini, C.; Giuri, D. Controlled Hydrolysis of Odorants Schiff Bases in Low-Molecular-Weight Gels. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 3105. [CrossRef]

- Hibbs, J. Anionic Surfactants. In Chemistry and Technology of Surfactants; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2006; pp. 91–132 ISBN 9780470988596.

- Hall-manning, T.J.; Holland, G.H.; Rennie, G.; Revell, P.; Hines, J.; Barratt, M.D.; Basketter, D.A. Skin Irritation Potential of Mixed Surfactant Systems. Food and Chemical Toxicology 1998, 36, 233–238. [CrossRef]

- Clendennen, S.K.; Boaz, N.W. Betaine Amphoteric Surfactants-Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. In Biobased Surfactants: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 447–469 ISBN 9780128127056.

- Smith, W.P. Epidermal and Dermal Effects of Topical Lactic Acid. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996, 35, 388–391. [CrossRef]

- Alsaheb, R.A.A.; Aladdin, A.; Othman, Z.; Malek, R.A.; Leng, O.M.; Aziz, R.; Enshasy, H.A. El Lactic Acid Applications in Pharmaceutical and Cosmeceutical Industries. Available online www.jocpr.com Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research 2015, 7, 729–735.

- Yu, G.; Yan, X.; Han, C.; Huang, F. Characterization of Supramolecular Gels. Chem Soc Rev 2013, 42, 6697–6722. [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Pochan, D.J. Rheological Properties of Peptide-Based Hydrogels for Biomedical and Other Applications. Chem Soc Rev 2010, 39, 3528–3540. [CrossRef]

- Gaucher, A.; Dutot, L.; Barbeau, O.; Hamchaoui, W.; Wakselman, M.; Mazaleyrat, J.P. Synthesis of Terminally Protected (S)-Β3-H-DOPA by Arndt-Eistert Homologation: An Approach to Crowned β-Peptides. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2005, 16, 857–864. [CrossRef]

- Zanna, N.; Iaculli, D.; Tomasini, C. The Effect of L-DOPA Hydroxyl Groups on the Formation of Supramolecular Hydrogels. Org Biomol Chem 2017, 15, 5797–5804. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).