1. Introduction

General Relativity (GR) and Quantum Mechanics (QM) together form the bedrock of modern physics. Yet, a consistent theoretical framework that unites them remains elusive. GR treats spacetime as a classical, dynamical manifold, whereas QM typically assumes a fixed background. Moreover, key phenomena in cosmology—the dark matter and dark energy sectors—defy straightforward explanations in both frameworks.

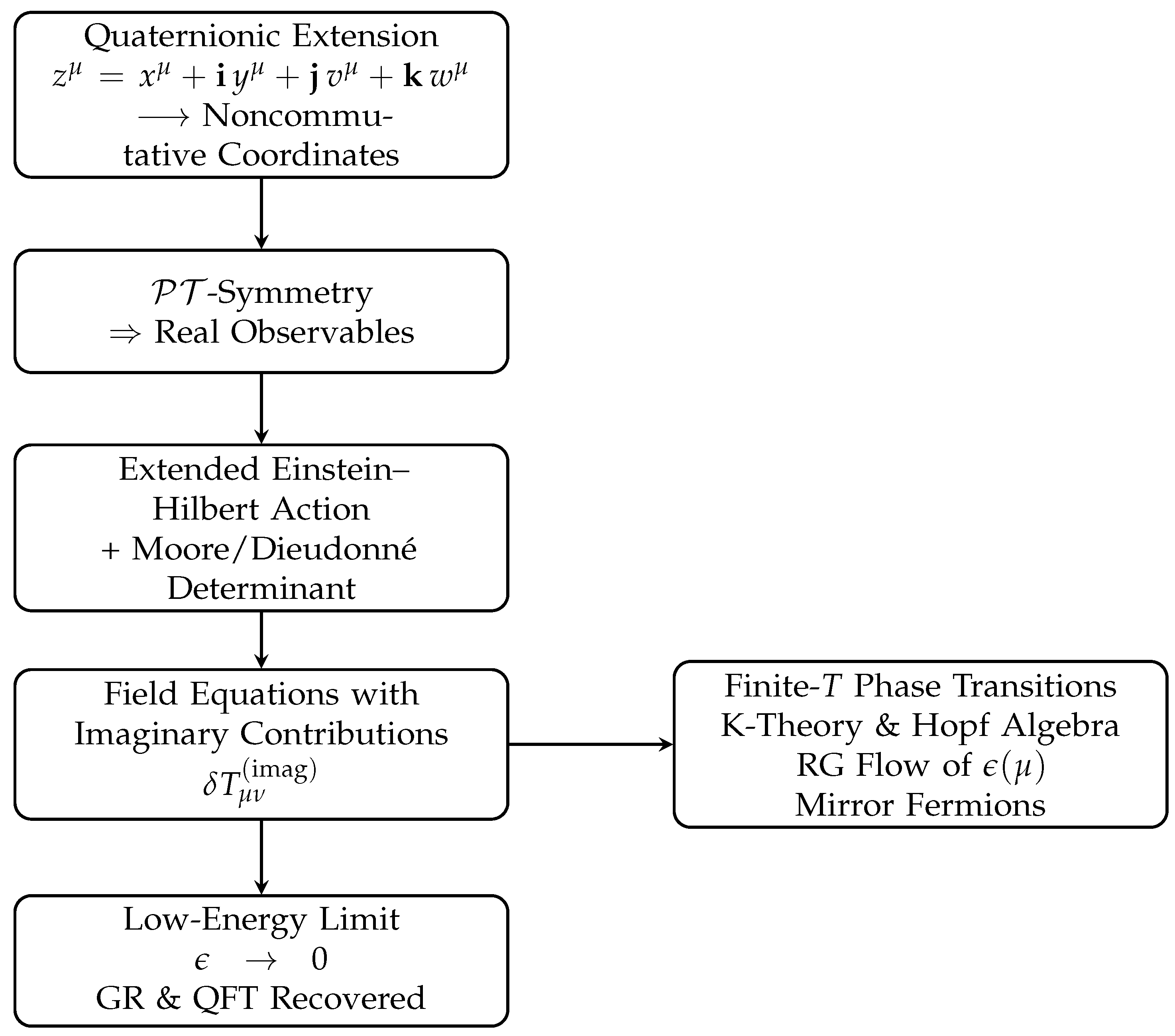

In this paper, we propose a quaternionic extension of spacetime, underpinned by combined -symmetry, that naturally embeds noncommutativity into the geometric structure of spacetime. Specifically:

Quaternionic Coordinates: Each real coordinate

is lifted to a quaternion

where the imaginary units

do not commute.

-Symmetry: Combining parity (P) and time-reversal (T) ensures that physical observables remain real.

Extended Einstein–Hilbert Action: By incorporating a symmetrized derivative and a noncommutative (Moore/Dieudonné) determinant, the imaginary components of the metric contribute an effective energy–momentum tensor that can explain dark energy and potentially dark matter.

Global Integrability and Quantization: Global consistency is enforced via hyperkähler/quaternionic-Kähler conditions and K-theory constraints. In addition, Hopf-algebra-based quantum-group methods offer a route to define a consistent noncommutative path integral.

Phenomenological Tests: A toy FLRW model shows that a perturbation reproduces dark-energy behavior. Analysis of GW170817 and SN Ia data further constrain the theory, with RG flow providing a natural suppression mechanism.

Table 1 summarizes a brief comparison between our approach and other quantum gravity frameworks. This complements string theory and LQG with a testable geometric approach.

Figure 1 presents a flow diagram summarizing our approach.

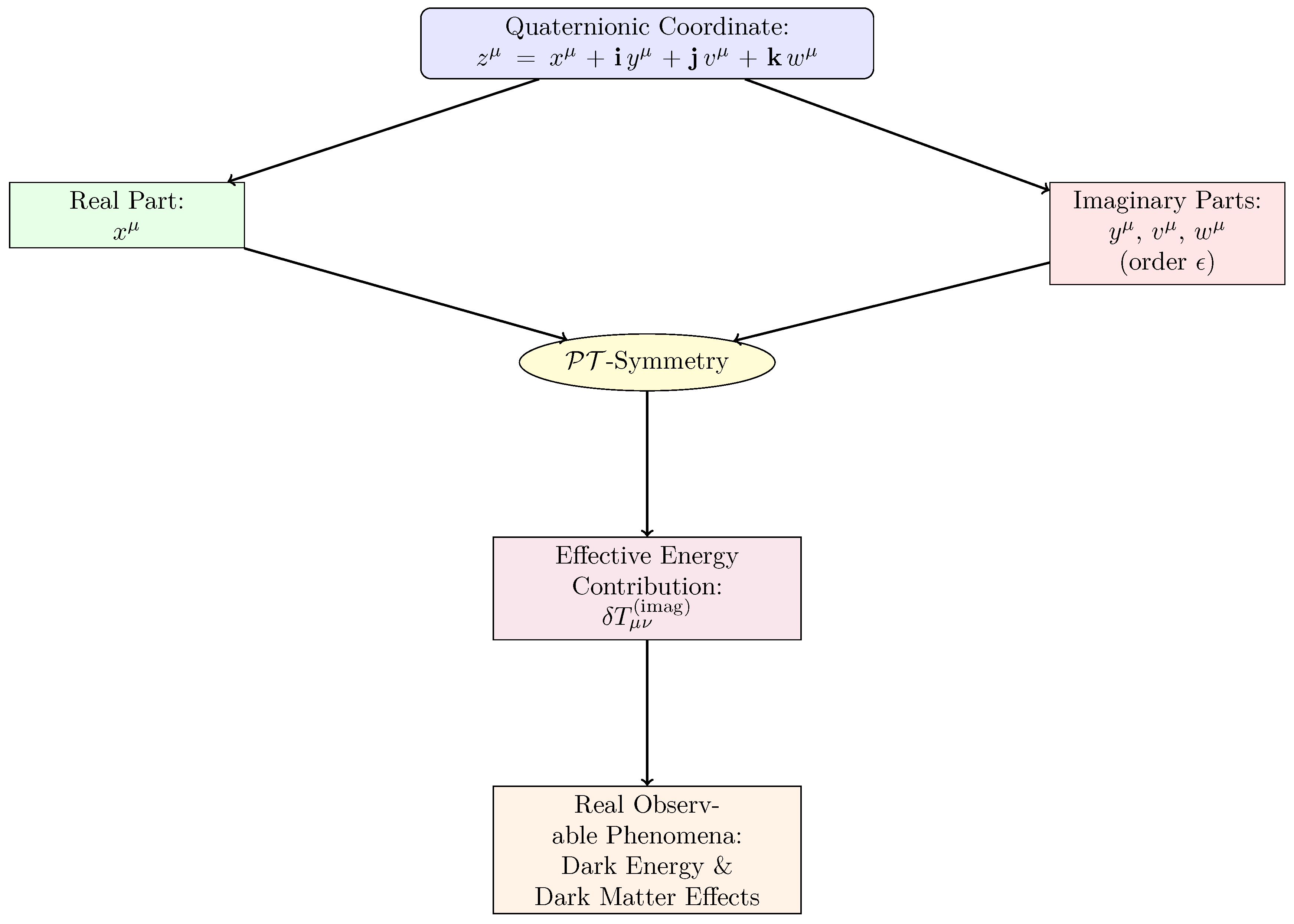

2. Physical Intuitive Interpretation

While the above sections detail the rigorous mathematical construction of the framework, it is instructive to provide an intuitive picture of the underlying physical ideas.

In our approach, each traditional spacetime coordinate

is extended to a quaternion:

Here, the additional components , , and (of order ) can be thought of as hidden or “internal” degrees of freedom at each point in spacetime. One can draw an analogy with how complex numbers extend the real line to capture rotations in the plane—in our case, quaternions extend spacetime to capture extra subtle features.

A key role is played by -symmetry. Despite the presence of these extra (imaginary) components, the symmetry ensures that any observable quantity (such as the energy density or curvature) remains real. In other words, while the additional degrees of freedom affect the dynamics (by contributing to the effective energy–momentum tensor), they do so in a way that the net effect is physically measurable and real.

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the real and imaginary components of the extended coordinate cooperate under

-symmetry, ensuring that final observables (e.g., total energy density) remain real. The effective energy from the imaginary part can naturally mimic or supplement dark energy and dark matter in a purely geometric way.

3. Mathematical Foundations of Quaternionic Geometry

A quaternion

q is written as

with

Each real coordinate

is extended to

introducing three additional degrees of freedom, typically of order

with

.

Global consistency requires hyperkähler or quaternionic-Kähler conditions [

9,

10,

11]. Nonvanishing quaternionic invariants (e.g., Pfaffians) can lead to domain walls or defects. Recent advances in K-theory, such as in [

13], further constrain the global topology of quaternionic spectral triples. In our construction, we assume suitable gluing conditions so that no major topological obstruction arises at

.

4. Quaternionic Metric, Determinant, and Inverse

4.1. Metric Construction and Moore/Dieudonné Determinant

We define the quaternionic metric as

Due to the complexity of taking determinants of quaternionic matrices, we adopt a real-projected version based on the Moore/Dieudonné determinant:

4.2. Inverse Metric and Bianchi Identity

The inverse metric

satisfies

-symmetry ensures that noncommutative anomalies cancel at leading order so that the Bianchi identity holds to

:

5. Differential Geometry: Symmetrized Derivatives

5.1. Symmetrized Derivative and Product Rule

We define the symmetrized derivative as

which, for small

, recovers the classical product rule up to corrections of order

.

5.2. Connection and Curvature

The connection is defined by

and the Riemann tensor is computed from this connection. Thanks to

-symmetry, extra commutator terms cancel at

, maintaining the standard Bianchi identity structure.

6. Extended Einstein–Hilbert Action and Field Equations

6.1. Action and Variation

The extended Einstein–Hilbert action is given by

where

is defined above and

is the quaternionic Ricci scalar. Varying the action to

leads to the field equations

where

originates from the imaginary parts of the metric.

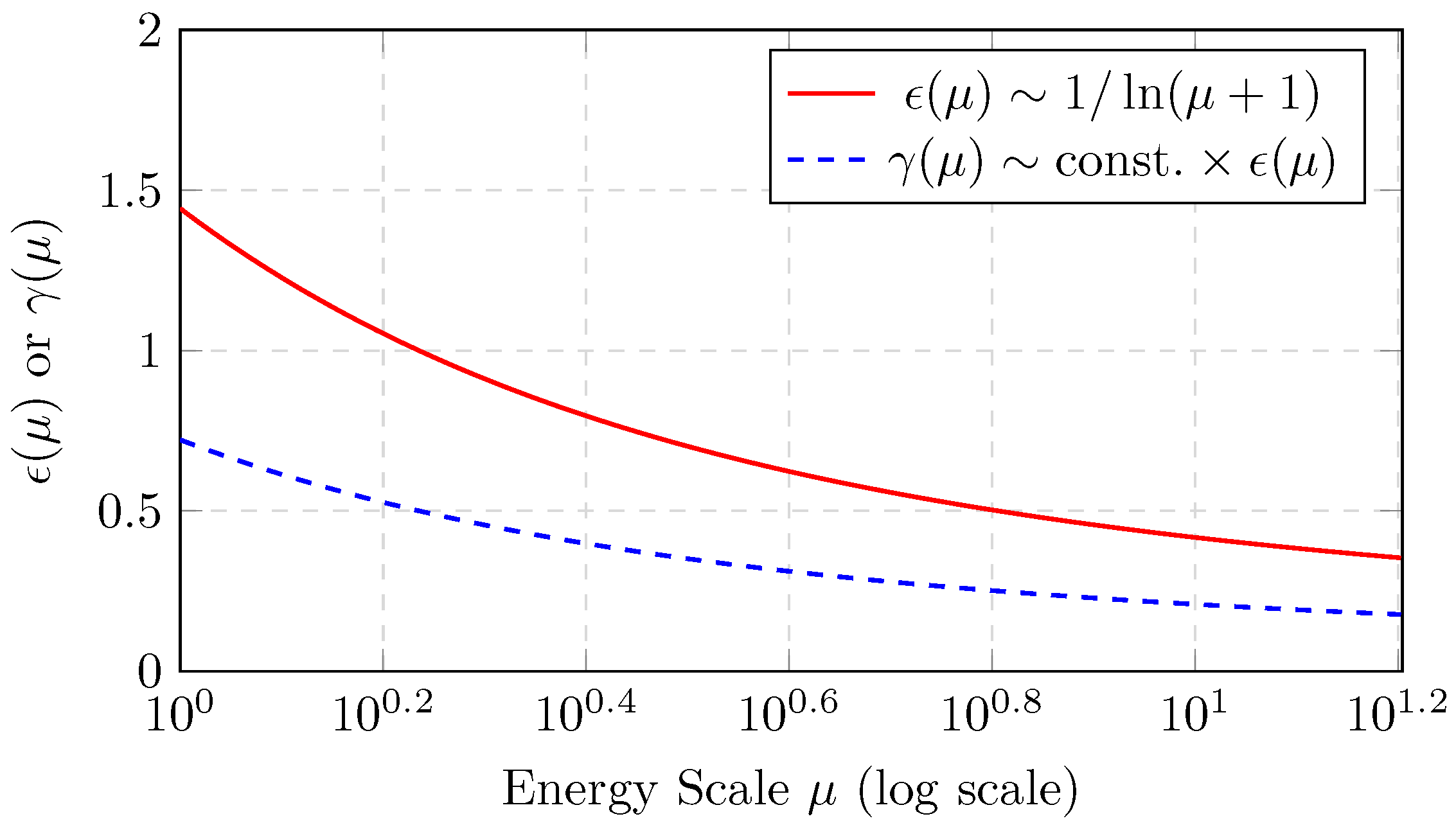

6.2. RG Flow and the Scale

A one-loop renormalization group (RG) analysis suggests

with

representing a UV cutoff (possibly near the Planck or GUT scale). As the energy scale

decreases,

diminishes, thereby naturally suppressing noncommutative corrections.

Physical Interpretation of Figure 3

Figure 3 illustrates how the imaginary metric parameter

(red line) evolves with the energy scale

. At

higher energies (right side of the log scale),

becomes

smaller, indicating that noncommutative effects in the quaternionic metric are naturally suppressed. This suppression ensures that at very high energies, the theory effectively recovers standard General Relativity (GR) and Quantum Field Theory (QFT) without large deviations.

Figure 3.

Schematic RG flow of the imaginary metric parameter .

Figure 3.

Schematic RG flow of the imaginary metric parameter .

By contrast, at lower energies (left side of the log scale), increases, suggesting that the extra imaginary components of the metric could play a more significant role—potentially giving rise to new phenomena such as dark energy or corrections to gravitational dynamics on cosmological scales. The dashed blue line is another parameter proportional to , showing a similar trend but scaled by a constant factor.

In this sense, the RG flow provides a natural mechanism for scale-dependent regulation:

High energies: remains small, preserving well-tested physics.

Low energies: grows, allowing for observable deviations such as an effective cosmological constant or other dark-sector-like effects.

This picture aligns with effective field theory principles, wherein new degrees of freedom may emerge at lower energies through a dynamical enhancement of parameters that were negligible at higher energies.

7. Example: Modified FLRW Metric and Dark Energy

7.1. Metric Ansatz

We consider a FLRW metric modified by small imaginary components:

Expanding the Ricci scalar to leads to an effective contribution that can mimic a cosmological constant.

7.2. Dark-Energy-Like Behavior

For

, the imaginary contributions can reproduce an effective dark energy density corresponding to

.

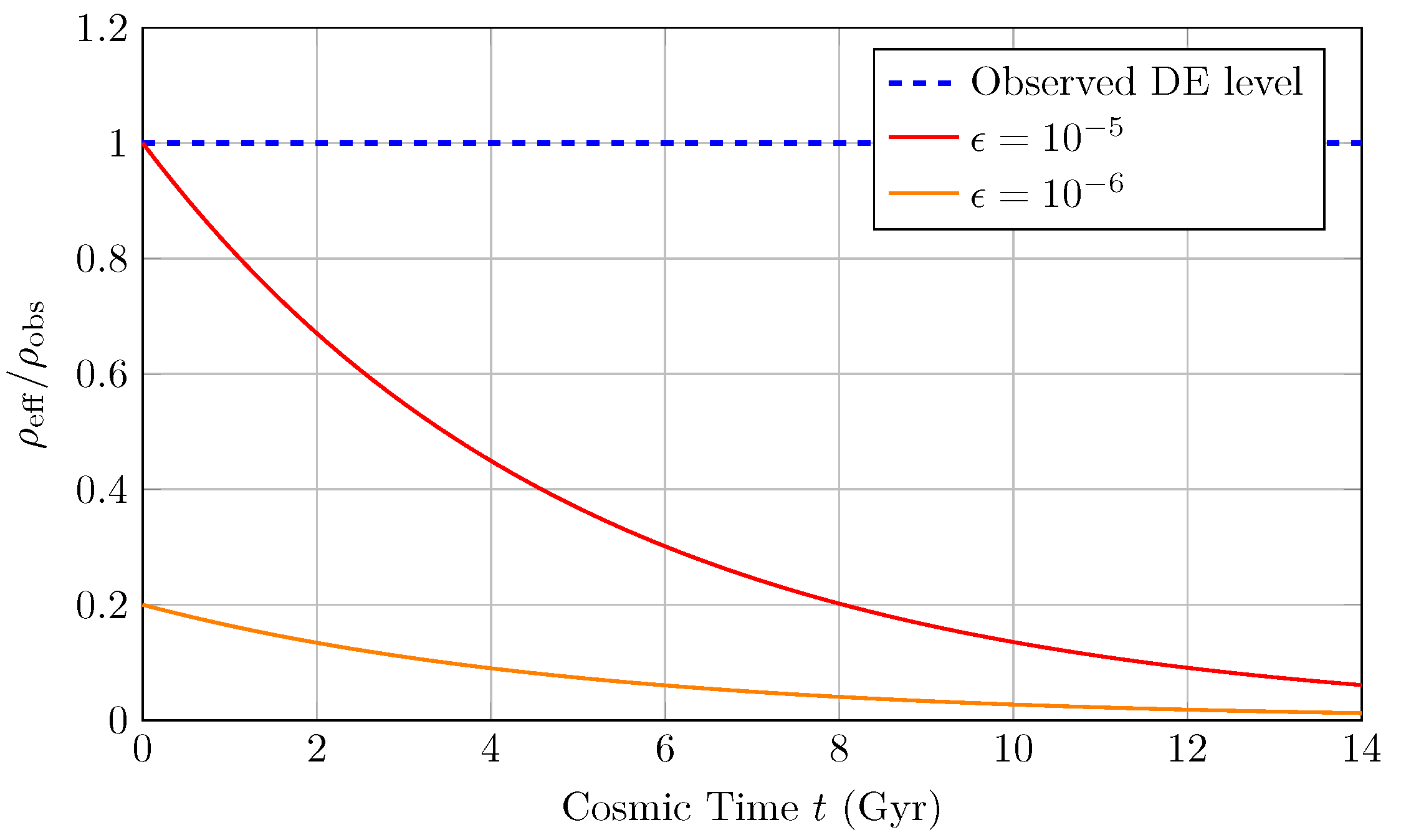

Figure 4 shows a representative evolution of

.

Physical Intuitive Interpretation of Figure 4

In

Figure 4, the curves illustrate how the effective dark energy density

evolves over cosmic time, given different values of the imaginary metric parameter

. The

blue dashed line represents the observed dark energy level, while the

red and

orange curves show the evolution for

and

, respectively.

An intuitive analogy is to think of this as a deflating balloon:

Early Universe: The imaginary metric components provide a higher effective energy density (similar to the balloon being more inflated).

As time progresses: The effective energy density gradually decreases, akin to a balloon slowly losing air.

Dependence on : Larger (red curve) leads to a slower decay, whereas smaller (orange curve) decays more rapidly.

This behavior suggests that dark energy may not be a fixed cosmological constant but rather a time-dependent phenomenon arising from small imaginary components in the spacetime metric. It is reminiscent of dynamical dark energy models such as quintessence but offers a purely geometric interpretation, wherein the imaginary directions of the quaternionic metric govern the decay rate of . Consequently, the observed dark energy density () can be naturally achieved for .

8. Dark Matter Perspective

In addition to dark energy, spatial variations in the imaginary components of the metric could generate halo-like gravitational effects. For example, an effective density profile

resembling the NFW profile might emerge due to non-uniform contributions of

. Instead of traditional N-body simulations, which assume dark matter as particle-like entities, a modified fluid-based approach or directly solving the modified gravitational equations is required to test whether this geometric mechanism can reproduce galactic rotation curves and gravitational lensing observations.

9. Global Structure, K-Theory, and Hopf-Algebraic Quantization

9.1. K-Theory and Topological Constraints

Quaternionic manifolds require consistent transition functions across patches. In noncommutative geometry, K-theory classifies projective modules [

12,

13]. Nontrivial topological invariants may form domain walls or brane-like structures. Although a full global classification is beyond our present scope, quaternionic spectral triples provide promising tools to analyze these issues.

9.2. Hopf-Algebraic Quantization

A naive path integral

faces ordering ambiguities in a noncommutative setting. A promising approach is to embed diffeomorphisms into a Hopf algebra

with an

R-matrix that enforces braided commutation relations [

15,

16]. The measure then includes a braided determinant

that preserves gauge invariance. While the full construction is deferred to future work, this approach offers a route to unify noncommutative geometry with standard QFT renormalization.

10. Physical Interpretations and Observational Prospects

10.1. Dark Sector Interpretation

The primary effect of the imaginary metric components is to mimic dark energy. However, if these components vary spatially, they might also generate effective mass distributions that contribute to galactic dynamics and lensing, offering a unified geometric interpretation for both dark energy and dark matter.

10.2. Observational Constraints

(i) Gravitational-Wave Speed.

Data from GW170817 and GRB 170817A restrict deviations in the gravitational-wave speed to

[

17]. Our FLRW model predicts

, but with RG flow (or an explicit suppression factor

), this can be reduced below

.

(ii) Pulsar Timing and Clock Networks.

High-precision pulsar timing experiments suggest in simplified models. More detailed analyses are required to tighten these constraints.

(iii) Collider Signatures and Mirror Fermions.

The quaternionic Dirac operator implies the existence of mirror fermions. If these states have masses in the TeV range, they could lead to missing-energy or displaced-vertex signals at the LHC. Preliminary estimates indicate that small mixing angles would preserve consistency with current experimental limits.

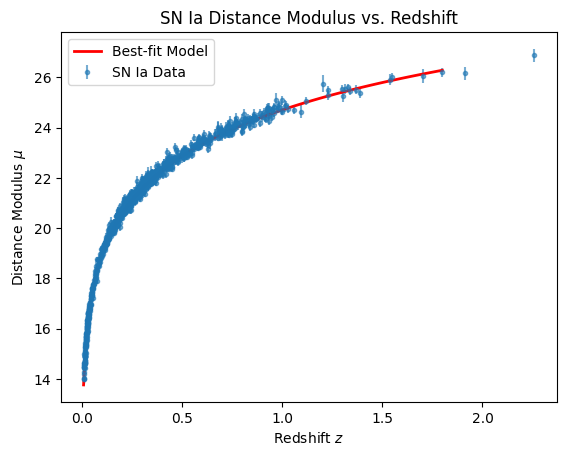

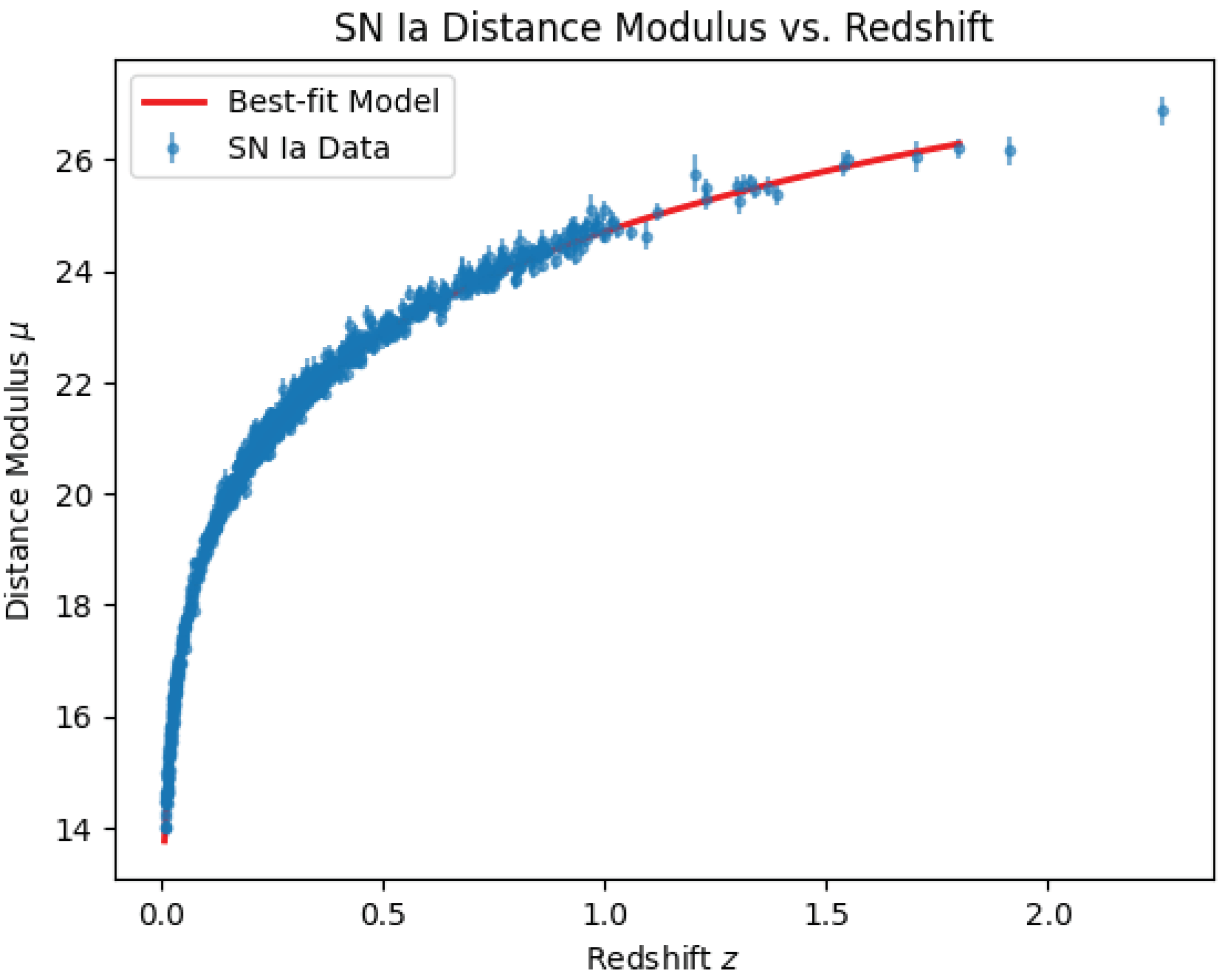

11. SN Ia Pantheon Data Analysis

We fit Type Ia supernova data (the Pantheon sample) by introducing an effective dark energy parameter

arising from the imaginary components of the metric. Our Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis yields:

which is consistent with

CDM.

Figure 5 shows the best-fit distance modulus compared to the data.

GitHub Repository. All Python scripts for the SN Ia data fitting (including the MCMC procedure) are available at our public GitHub repository:

12. Conclusions and Future Directions

We have presented a -symmetric quaternionic extension of spacetime that:

Embeds noncommutativity into the metric, with -symmetry ensuring real observables.

Extends the Einstein–Hilbert action via a Moore/Dieudonné-based determinant, introducing effective dark-sector contributions .

Recovers standard GR and QFT in the low-energy limit, with RG flow naturally suppressing imaginary components.

Allows for finite-temperature phase transitions, potential gravitational-wave signals, and an extended quaternionic Dirac operator that can accommodate mirror fermions, consistent with current collider constraints.

Provides a good fit to SN Ia data (with ) and satisfies partial constraints from GW170817.

Open issues include:

Further mathematical rigor at higher orders, including complete proofs of the noncommutative variation and Bianchi identity.

Detailed dark matter phenomenology via N-body simulations or analytical halo models.

Refined RG flow computations to clarify the physical meaning of the UV scale .

Comprehensive studies on mirror fermion phenomenology and collider constraints.

Implementation of a full Hopf-algebraic quantization scheme.

Continued refinements in both the mathematical framework and phenomenological tests will determine whether this approach can ultimately address the puzzles of dark energy, dark matter, and quantum spacetime.

Appendix A. Additional Quaternionic Algebra Details

Recall the product of two quaternions

yields cross-terms:

Thus, operator ordering is essential when imaginary components are present.

Appendix B. Higher-Order Terms in the Symmetrized Derivative and Bianchi Identity

The symmetrized derivative

eliminates many first-order noncommutative obstructions, but second-order corrections (

) may contribute to torsion or curvature corrections.

-symmetry cancels the leading-order anomalies; a complete treatment of higher orders is deferred to future work.

Appendix C. Variational Details with Noncommutative Ordering

When varying the action

the noncommutativity of

and

requires a normal-ordering prescription valid to

:

This prescription ensures that real contributions are collected at first order. Higher-order terms may require a fully braided measure based on Hopf-algebraic techniques.

References

- S. L. Adler, Quaternionic Quantum Mechanics and Quantum Fields, Oxford University Press (1995).

- C. M. Bender and S. Boettcher, “Real spectra in non-Hermitian Hamiltonians having PT symmetry,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 5243–5246 (1998).

- C. M. Bender, S. Boettcher, and P. N. Meisinger, “PT-symmetric quantum mechanics,” J. Math. Phys. 40, 2201–2229 (1999).

- C. M. Bender, “Making sense of non-Hermitian Hamiltonians,” Rep. Prog. Phys. 70, 947 (2007).

- A. Mostafazadeh, “Pseudo-Hermiticity and Generalized PT- and CPT-Symmetries,” J. Math. Phys. 44, 974–989 (2003).

- C. M. Bender and D. W. Hook, “Geometry of PT-Symmetric Quantum Mechanics,” J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 56, 125302 (2023).

- L. P. Horwitz and L. C. Biedenharn, Ann. Phys. 157, 432–488 (1984).

- D. Finkelstein, J. M. Jauch, S. Schiminovich, and D. Speiser, J. Math. Phys. 3, 207–220 (1962).

- K. Kodaira and D. C. Spencer, Ann. Math. 71, 43 (1963).

- A. Swann, Math. Ann. 289, 421–450 (1991).

- D. Joyce, J. Differential Geom. 55, 3–38 (2000).

- A. Connes, J. Math. Phys. 36, 6194–6231 (1995).

- A. Connes, “Geometry and the Quantum,” Found. Phys. 45, 225–230 (2015).

- S. L. Woronowicz, Commun. Math. Phys. 122, 125 (1989).

- S. Majid, Foundations of Quantum Group Theory, Cambridge University Press (1995).

- S. Majid, A Quantum Groups Primer, Cambridge University Press (2002).

- B.P. Abbott et al. (LIGO Scientific and Virgo Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 161101 (2017).

- M. Hindmarsh, S.J. Huber, K. Rummukainen, and D.J. Weir, Phys. Rev. D 92, 123009 (2015).

- M. Hindmarsh, K. Rummukainen, and D.J. Weir, Phys. Rev. D 95, 063520 (2017).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).