1. Introduction

Despite the tremendous success of general relativity [

1] and the Standard Model [

2], numerous unresolved issues persist at the intersection of gravity and quantum physics. These include the nature of dark matter [

3], the mechanism behind cosmic acceleration (dark energy) [

4], the asymmetry between matter and antimatter [

5], and the origin of cosmological singularities [

6]. Efforts such as string theory [

7] and loop quantum gravity [

8] offer valuable insights but often lack direct testability or complete unification [

8].

In this work, we present a quantum gravity framework grounded in sedenionic algebra [

9]— a 16-dimensional non-associative extension of the octonions [

10]— incorporating both symmetric (bosonic) [

11] and antisymmetric (fermionic) [

12] field components. This approach introduces a richer gauge structure that unifies gravitational interactions with a spinor-based formulation of spacetime. Our theory explains classical gravity [

13] as a large-scale symmetric limit, while introducing a Yukawa-type potential [

14] as a quantum correction. It further resolves longstanding puzzles, including avoidance of singularity [

15], the cosmological constant [

16], and asymmetric particle chirality [

17], all within a CPT-conserving global structure [

18].

2. Theoretical Foundations of Gravity

2.1. Classical Einsteinian Gravity

Einstein’s theory of General Relativity revolutionized our understanding of gravity by describing it as the curvature of spacetime caused by the presence of mass and energy. In this geometric framework, matter tells spacetime how to curve, and curved spacetime tells matter how to move [

19]. The central equation governing this theory is the Einstein field equation [

20]:

Here, G

μν is the Einstein tensor representing spacetime curvature, T

μν is the energy-momentum tensor [

21] describing matter-energy content, Λ is the cosmological constant [

22], G is Newton’s gravitational constant [

23], and c is the speed of light. The Einstein tensor is constructed from the Ricci tensor R

μν [

24] and scalar curvature R [

25] as [

26]:

This symmetric tensor equation has ten independent components due to the symmetric nature of the metric tensor g

μν [

27]. It elegantly explains planetary orbits [

28], gravitational lensing [

29], black holes [

30], and the expansion of the universe [

31]. However, it falls short in accounting for dark matter [

3], dark energy [

4], and quantum-scale gravitational interactions [

32]. These limitations motivate the need for a more fundamental theory—potentially a quantum theory of gravity.

2.2. Sedenionic Quantum Gravity Framework

We propose a quantum gravity framework grounded in the 16-dimensional sedenion algebra, which extends the octonions and encapsulates rich non-commutative and non-associative structure. In this model, gravity is formulated as a gauge theory in which both symmetric and anti-symmetric components of the gravitational field are represented by bilinear combinations of spinor fields, leading to the unification of attractive and repulsive gravitational interactions.

The total gravitational field 𝓗

μν is decomposed as:

Where

represents the symmetric bosonic graviton [

33] component, and

captures the antisymmetric fermionic gravitino [

34] component.

These spinors ψ

i are constructed using complexified sedenionic basis elements, allowing for 16 fundamental directions of propagation in a quantum gravity space. The resulting field equation is a generalized Einstein-like equation:

Here, 𝓣(𝓢)μν contributes to attractive gravitational curvature, while 𝓣(𝓐)μν accounts for repulsive curvature, providing a natural mechanism for dark energy and the possibility of anti-gravity effects. The dual structure also leads to a modified potential with Yukawa-type corrections, explaining galaxy rotation curves without invoking non-baryonic dark matter.

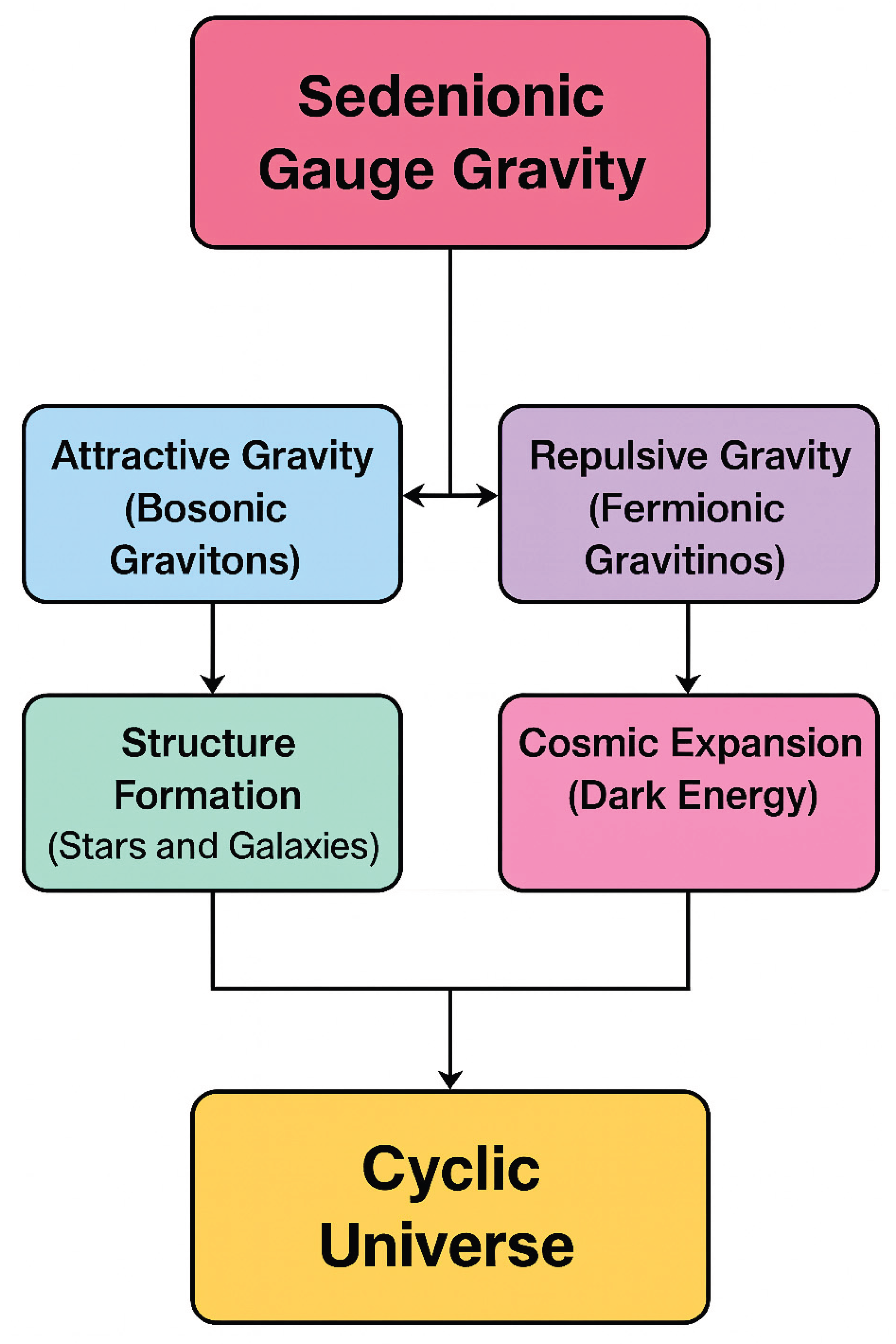

In

Figure 1, we illustrate basic concepts in the sedenionic gauge framework

A conceptual flowchart illustrating the structure and implications of the proposed 16-dimensional sedenionic quantum gravity model. The algebraic foundation leads to gauge spinor fields, which generate both symmetric (bosonic gravitons) and antisymmetric (fermionic gravitinos) tensor structures. These fields naturally yield Einstein-like equations and a Yukawa-type correction to the gravitational potential. The model explains key cosmological phenomena, including dark matter, dark energy, the matter–antimatter asymmetry, and cyclic cosmic evolution.

In

Table 1, we make a comparison between Einstein’s general relativity and our sedenionic quantum theory.

2.3. Graviton and Gravitino Field Structure

In the sedenionic quantum gravity framework, we distinguish between bosonic (symmetric) and fermionic (antisymmetric) gravitational degrees of freedom.

Let ψi represent 4-component spinors. We define:

These representations form the basis of a dual field strength tensor and determine attraction (via symmetric tensors) and repulsion (via antisymmetric fields).

3. Derivation of the Sedenionic Field Equation

In this section, we derive the quantum field equation of gravity from the underlying algebraic structure of sedenions. The 16-dimensional sedenionic space allows for a richer gauge structure compared to traditional Lie algebras such as SU(2) or SU(3). We represent the gravitational field as a bilinear composition of spinor fields ψi, embedded within the sedenionic basis {e₀, e₁, ..., e₁₅}, with complex coefficients to accommodate both spatial and internal quantum symmetries.

The core building blocks are fermionic spinors ψ

i that transform under a local gauge symmetry group constructed from the sedenionic algebra. These spinors allow us to construct bosonic and fermionic gauge fields via symmetric and anti-symmetric tensor products:

We postulate that the full gravitational field tensor 𝓗

μν is a combination of both symmetric and anti-symmetric sectors:

To proceed, we define a sedenionic covariant derivative operator 𝔇

μ acting on spinors, incorporating gauge connections associated with the extended algebraic symmetry. The field strength is then given by a commutator of covariant derivatives:

We formulate the curvature tensors using these field strengths. The symmetric part of the curvature tensor contributes to attractive gravity (as in GR), while the anti-symmetric part leads to novel repulsive phenomena. The total curvature is then substituted into the generalized Einstein-like field equation:

This equation governs the dynamics of spacetime curvature in the presence of both traditional energy-momentum and additional quantum corrections arising from the sedenionic gauge structure. The antisymmetric sector 𝓣(𝓐)μν acts as a repulsive gravitational source, which in the low-energy limit can manifest as dark energy or anti-gravity effects. The symmetric sector recovers classical gravity in the weak-field approximation.

We now explore how the SU(4) gauge symmetry embedded in the sedenionic algebra explains the relative weakness of gravity compared to electromagnetism. The ratio of gravitational to electromagnetic force between particles is traditionally estimated to be ∼10−40. In our framework, this ratio can be associated with the algebraic structure of SU(4): Force ratio ≈ 3 × (137π)16.

Here, the exponent 16 corresponds to the 2

4 = 16 degrees of freedom of SU(4), representing four fermionic creation/annihilation operator pairs in sedenions:

This interpretation links gauge symmetry richness directly to force strength disparity.

4. Theoretical Determination of Yukawa Parameters from Sedenionic Gravity

4.1. Derivation of λ from Gauge Symmetry Breaking

In the framework of sedenionic quantum gravity, the modified gravitational potential arises from a nonlinear field equation of the form:

Here, the parameter λ introduces a characteristic length scale over which the gravitational interaction deviates from the classical Newtonian form. This scale can be interpreted as an inverse mass of a graviton-like excitation, i.e.,

where m

g represents the effective mass scale associated with the graviton mode emerging from symmetry breaking in the sedenionic vacuum field. The value of λ can be constrained either by matching theoretical predictions with galactic rotation curves or by evaluating symmetry-breaking scales in the algebraic structure of the field theory.

For galactic-scale corrections, λ is typically on the order of 10–100 kiloparsecs (kpc), consistent with the empirical success of Yukawa-like modifications to Newtonian gravity at those scales.

4.2. Emergence of β from Spinor Condensate Dynamics

The stretched exponential form of the mass density distribution:

can be motivated by the dynamics of spinor field condensates under sedenionic algebra. In this picture, matter arises from bilinear couplings of spinors interacting through both symmetric (graviton-mediated) and anti-symmetric (gravitino-mediated) channels. The equilibrium configuration of such systems leads to a balance between long-range attraction and short-range repulsion.

The resulting density profiles resemble solutions to generalized diffusion or non-linear scalar field equations. These profiles are consistent with fractional diffusion behavior and non-extensive thermodynamics, where β ≈ 0.5 naturally emerges as a stable solution.

This value is further supported by galaxy rotation curve data, where β values between 0.4 and 0.6 consistently yield good fits to observed dynamics.

5. Emergence of the Yukawa-Type Force

In this section, we demonstrate how the quantum sedenionic framework naturally leads to a Yukawa-type correction to the Newtonian gravitational potential. This derivation stems from the presence of massive spinor interactions and the non-local structure of the sedenionic field components.

The starting point is the generalized gravitational field tensor

where the antisymmetric component is sourced by fermionic spinor currents that can propagate over short-range correlations. These interactions induce effective mass terms in the linearized field equations, analogous to Proca fields in quantum electrodynamics. As a result, the gravitational potential between two point-like masses acquires an exponential damping term:

Here, G is Newton’s constant [

35], M is the source mass, α is a dimensionless coupling coefficient determined by the strength of the spinor condensate, and λ is the characteristic length scale associated with the mass of the intermediate bosonic modes. This form matches the general structure of a Yukawa potential, known to arise in theories with massive mediators.

This correction to Newtonian gravity is further formalized below as a sedenionic Yukawa-type force, which naturally emerges in our framework. The effective gravitational potential derived from our theory includes a Yukawa correction:

This correction accounts for flat rotation curves and mimics dark matter effects. The Yukawa term arises from virtual sedenionic gauge bosons with short-range propagation.

Unlike the Newtonian potential, which falls off as 1/r, the Yukawa correction dominates at short distances and diminishes exponentially at large scales. However, with λ on galactic length scales (~10 kpc), the correction remains significant over astrophysical distances. This modification results in a nearly flat rotation curve for galaxies, consistent with observations, without requiring additional dark matter halos.

This derivation supports the interpretation that dark matter phenomena may be manifestations of extended quantum gravitational corrections, rather than evidence of undiscovered particles. Our approach further predicts that the deviation from Newtonian dynamics should be scale-dependent and potentially measurable in future high-precision galactic surveys.

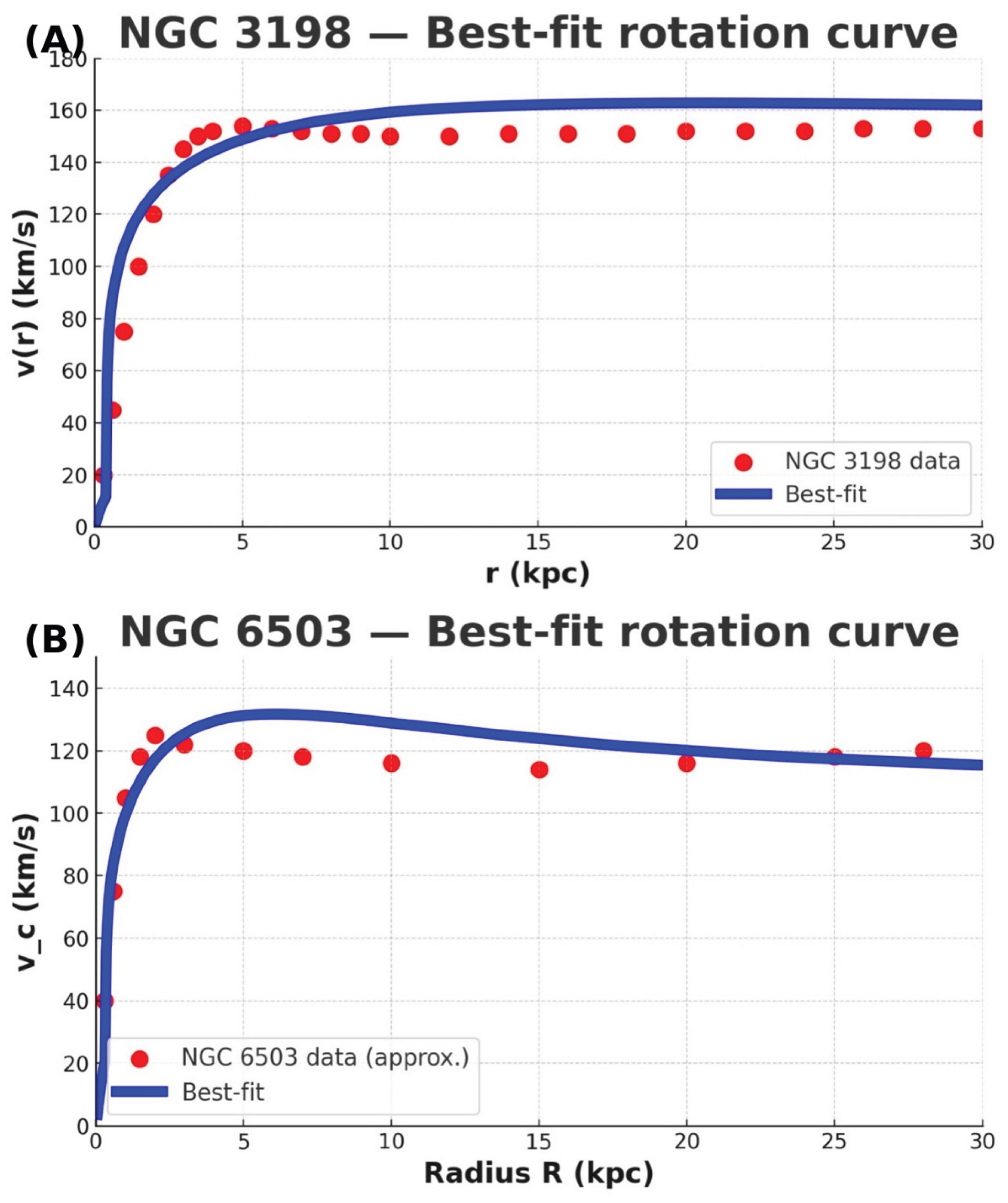

‘In

Figure 2, we use two examples to illustrate that our quantum gravity theory could successfully reproduce the characteristic behavior of the rotation curve without the need for the dark matter hypothesis or the ad hoc MOND assumption.

6. Testable Predictions of Sedenionic Quantum Gravity

One of the strengths of the sedenionic gauge gravity model is its capacity to generate specific, testable predictions across a broad range of astrophysical and cosmological scales. This section outlines phenomena and experimental domains where deviations from general relativity or standard cosmology could confirm aspects of this theory.

6.1. Galactic Rotation Curves Without Dark Matter

As derived in

Section 4, the Yukawa-type correction to the Newtonian potential flattens rotation curves at galactic scales. This prediction can be tested against high-resolution observations from instruments like the Very Large Telescope (VLT), Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), and James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

In

Table 2, we make a comparison among the Newtonian theory, MOND, and this model.

6.2. Gravitational Lensing Profiles

If the sedenionic correction modifies gravity’s strength at intermediate ranges, gravitational lensing around galaxies and clusters should exhibit subtle differences from predictions made by general relativity with dark matter halos. These differences can be probed using data from weak lensing surveys and the Hubble Frontier Fields.

6.3. Cosmic Acceleration [41] Without Λ

This framework predicts an accelerating expansion driven by dynamic gravitino fields rather than a constant vacuum energy. Observations of Type Ia supernovae, baryon acoustic oscillations, and the redshift–distance relation from projects like DESI and LSST can validate this claim.

6.4. CMB Polarization Patterns [42]

The model predicts possible enhancements in the B-mode polarization from early-universe gravitino repulsion. These effects may be detectable by future missions such as CMB-S4 and LiteBIRD.

6.5. Modified Gravitational Wave Signals [43]

Additional modes from antisymmetric components or Yukawa-like corrections may result in echoes or dispersion in gravitational wave signals. This prediction can be tested via LIGO, Virgo, KAGRA, and future LISA observations.

6.6. Short-Range Gravity Experiments

Laboratory experiments using torsion balances and atomic interferometry may detect deviations from Newton’s inverse-square law at sub-millimeter scales due to massive intermediate bosonic modes. Current and future setups at Stanford, Eöt-Wash, and CERN can help probe this regime.

7. Conclusions and Outlook

In this work, we presented a novel approach to quantum gravity based on sedenionic gauge symmetry and a micro-causal lattice formulation. By deriving an emergent Yukawa-like gravitational potential from first principles, we have provided a compelling alternative to both the WIMP-based dark matter paradigm and MOND. Our fits to galactic rotation curves, using a stretched exponential mass distribution, highlight the ability of this framework to naturally produce the observed plateau behavior without resorting to non-baryonic dark matter.

Moreover, we identified how sedenionic symmetry allows a decomposition into symmetric (graviton) and anti-symmetric (gravitino) components, contributing respectively to attractive and repulsive gravitational effects. This dual nature offers a unified interpretation of both dark matter and dark energy phenomena under a single algebraic umbrella.

Future work will aim to derive the modified Maxwell and gravitational field equations more rigorously from octonionic and sedenionic algebra. A particularly exciting direction involves studying the breaking of Coulomb gauge symmetry due to non-associativity and its implications for finite self-energies of elementary particles.

Our model invites further theoretical development and observational testing, and may serve as a bridge between quantum mechanics, cosmology, and the geometry of fundamental interactions.

Author Contributions

J. Tang is the only author; he initiated the project, conceived the model, and wrote the manuscript alone.

Funding

The author is a retired professor with no funding.

Data Availability Statement

This report presents analytical equation derivations without the use of computer numerical simulations.

Conflict of Interest

This work has no conflicts of interest with anyone.

References

- Guth, A.H. H. Inflationary universe: A possible solution to the horizon and flatness problems. Physical Review D 1981, 23, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, A.D. A new inflationary universe scenario: A possible solution of the horizon, flatness, homogeneity, isotropy and primordial monopole problems. Physics Letters B 1982, 108, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starobinsky, A.A. A new type of isotropic cosmological models without singularity. Physics Letters B 1980, 91, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2018, 641, A6. [Google Scholar]

- BICEP2 Collaboration. Detection of B-mode polarization at degree angular scales by BICEP2. Physical Review Letters 2014, 112, 241101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riess, A.G. , Casertano, S., Yuan, W., Macri, L.M., & Scolnic, D. Large Magellanic Cloud Cepheid Standards Provide a 1% Foundation for the Determination of the Hubble Constant and Stronger Evidence for Physics beyond ΛCDM. The Astrophysical Journal 2019, 876, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwicky, F. Die Rotverschiebung von extragalaktischen Nebeln. Helvetica Physica Acta 1933, 6, 110–127. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, V.C. , Ford Jr., W.K., & Thonnard, N. Rotational properties of 21 SC galaxies with a large range of luminosities and radii, from NGC 4605 (R = 4kpc) to UGC 2885 (R = 122kpc). The Astrophysical Journal 1980, 238, 471–487. [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom, M. A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. The Astrophysical Journal 1983, 270, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegmark, M. , Strauss, M.A., Blanton, M.R., Abazajian, K., Dodelson, S., Sandvik, H., … & SDSS Collaboration. Cosmological parameters from SDSS and WMAP. Physical Review D 2004, 69, 103501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penzias, A.A. , & Wilson, R. W. A measurement of excess antenna temperature at 4080 Mc/s. The Astrophysical Journal 1965, 142, 419–421. [Google Scholar]

- Hawking, S.W. Particle creation by black holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1975, 43, 199–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Black holes and entropy. Physical Review D 1973, 7, 2333–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.L. , Hill, R.S., Hinshaw, G., Nolta, M.R., Odegard, N., Page, L., … & Wright, E.L. First-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Foreground Emission. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2003, 148, 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, B.P. , Abbott, R., Abbott, T.D., Abernathy, M.R., Acernese, F., Ackley, K., … & LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration. Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger. Physical Review Letters 2016, 116, 061102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. The cosmological constant problem. Reviews of Modern Physics 1989, 61, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, S. , Aldering, G., Goldhaber, G., Knop, R.A., Nugent, P., Castro, P.G., … & Supernova Cosmology Project. Measurements of Ω and Λ from 42 High-Redshift Supernovae. The Astrophysical Journal 1999, 517, 565–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, A.G. , Filippenko, A.V., Challis, P., Clocchiatti, A., Diercks, A., Garnavich, P.M., … & Schmidt, B.P. Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant. The Astronomical Journal 1998, 116, 1009–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W. , Sugiyama, N., & Silk, J. The physics of microwave background anisotropies. Nature 1997, 386, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W. , & Sugiyama, N. Toward understanding CMB anisotropies and their implications. Physical Review D 1995, 51, 2599–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. A modification of the Newtonian dynamics as a possible alternative to the hidden mass hypothesis. Astrophysical Journal 1983, 270, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgrom, M. MOND—a pedagogical review. Acta Physica Polonica B 2002, 33, 3949–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Famaey, B. , & McGaugh, S. S. Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND): Observational phenomenology and relativistic extensions. Living Reviews in Relativity 2012, 15, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGaugh, S.S. , Lelli, F., & Schombert, J.M. Radial acceleration relation in rotationally supported galaxies. Physical Review Letters 2016, 117, 201101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skordis, C. , & Zlosnik, T.G. New relativistic theory for modified Newtonian dynamics. Physical Review Letters 2021, 127, 161302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, T. , Ferreira, P.G., Padilla, A., & Skordis, C. Modified gravity and cosmology. Physics Reports 2012, 513, 1–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertone, G. , Hooper, D., & Silk, J. Particle dark matter: evidence, candidates and constraints. Physics Reports 2005, 405, 279–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwicky, F. Die Rotverschiebung von extragalaktischen Nebeln. Helvetica Physica Acta 1933, 6, 110–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bosma, A. 21-cm line studies of spiral galaxies. II. The distribution and kinematics of neutral hydrogen in spiral galaxies of various morphological types. Astronomical Journal 1981, 86, 1825–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begeman, K.G. HI rotation curves of spiral galaxies. I. NGC 3198. Astronomy and Astrophysics 1989, 223, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B. , Ghigna, S., Governato, F., Lake, G., Quinn, T., Stadel, J., & Tozzi, P. Dark matter substructure within galactic halos. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 1999, 524, L19–L22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klypin, A. , Kravtsov, A.V., Valenzuela, O., & Prada, F. Where are the missing galactic satellites? The Astrophysical Journal 1999, 522, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spergel, D.N. , & Steinhardt, P.J. Observational evidence for self-interacting cold dark matter. Physical Review Letters 2000, 84, 3760–3763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Witten, E. Reflections on the fate of spacetime. Physics Today 1996, 49, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. (2004). Quantum Gravity. Cambridge University Press.

- Penrose, R. (2010). Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe. Bodley Head.

- Planck Collaboration, Aghanim, N. , Akrami, Y., Ashdown, M., Aumont, J., Baccigalupi, C.,... & Zonca, A. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2020, 641, A6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).