1. Introduction

During the recent years, Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) are experiencing a growing interest of industry and research, alike. The flexibility of UAS design paired with enhanced sensors and the rapidly evolving processing- and guidance algorithms create a fertile ground for new and cost-efficient solutions for many economic areas like logistics and maintenance. In order to enable a safe operation of UAS, regulatory frameworks have been developed, posing a wide range of requirements on design, operation, and maintenance. An integral part of this strategy is the safe integration of UAS into the airspace [

1]. To achieve this, detect and avoid (DAA) systems are required for certain types of operations by regulatory authorities.

Besides the efforts to integrate certified UAS into the airspace, interests have risen to also enable the integration of non-certified UAS. A framework to achieve this has been developed by the Joint Authorities for Rulemaking on Unmanned Systems (JARUS) which has been adopted by many countries.

Within the European Union (EU), the Commission Delegated Regulation EU 2019/945 of the European Commission establishes the JARUS framework and introduces three different UAS classes: open, specific, and certified. Based on different operational parameters, like maximum take-off mass (MTOM), maximum dimension, and operational domains, one of these classes is assigned to each defined operation and each vehicle. The Commission Implementing Regulation EU 2019/947 enhances the framework by introducing requirements for these classes. While the open category does not demand specific equipment, the certified class requires a DAA system to promote the separation from other aircraft. The specific class represents a special case as it requires a risk assessment to derive additional requirements. Furthermore, the regulation defines the JARUS Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA) 2.0 as an Acceptable Means of Compliance (AMC) in its amendment. As a part of this assessment, the concept Air Risk Classes (ARCs) is introduced. Based on the traffic density of the operational volume, an ARC is assigned to the operation. The scale ranges from ARC-a as the lowest air risk to ARC-d as the highest one. When operating in ARC-b and beyond, a DAA system must be utilized to mitigate the collision risk. The performance requirements on the DAA system become higher with an increasing ARC level. For more detailed information about the ARC and the specific category, it is recommended to review the associated documents [

2,

3].

Summing up, it can be seen that these regulatory documents do not only make a DAA system a necessity for many UAS applications, but also introduce requirements and boundary conditions. These requirements and boundary conditions are further refined by several DAA standards. These standards do not only define requirements for concrete equipment and their integration, but also pose a wide range of performance requirements on the logic of a DAA system. Algorithms for detection, alerting, and manoeuvring must fulfil these requirements to be used within a DAA system. This motivates an analysis of how these documents affect engineering and research in this field.

It shall be mentioned here that there is an endeavor to introduce dedicated volumes for UAS operations within the existing airspace classes, called U-space, which is defined in the Commission Implementing Regulations EU 2021/664, 2021/665, and 2021/666. Among other things, it incorporates concepts for a UAS traffic management (UTM), designated geographical zones, and supporting services. Moreover, special demands on DAA capabilities of vehicles operating within these volumes are formulated [

4,

5,

6]. However, since there are, due to their early development state, currently neither standards nor manuals or guidelines on U-space DAA capabilities available, U-space will not be covered within this paper.

2. Detect and Avoid in Manned Aviation

The modern DAA approaches for UAS, as described by the standards, build up on the experience and methodology of collision avoidance methods for manned aircraft. Therefore, it is reasonable to briefly revisit the history and major aspects of manned aircraft DAA, in order to foster the understanding of UAS DAA concepts.

2.1. ICAO Conflict Management

The avoidance of collision is an integral part of International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Annex 2 Rules of the Air. It comprises procedures, the right of way (RoW) rules, and technical measures to reduce collision hazards. It states that the pilot-in-command (PIC) has the responsibility to keep well clear of other traffic and avoid collision hazards [

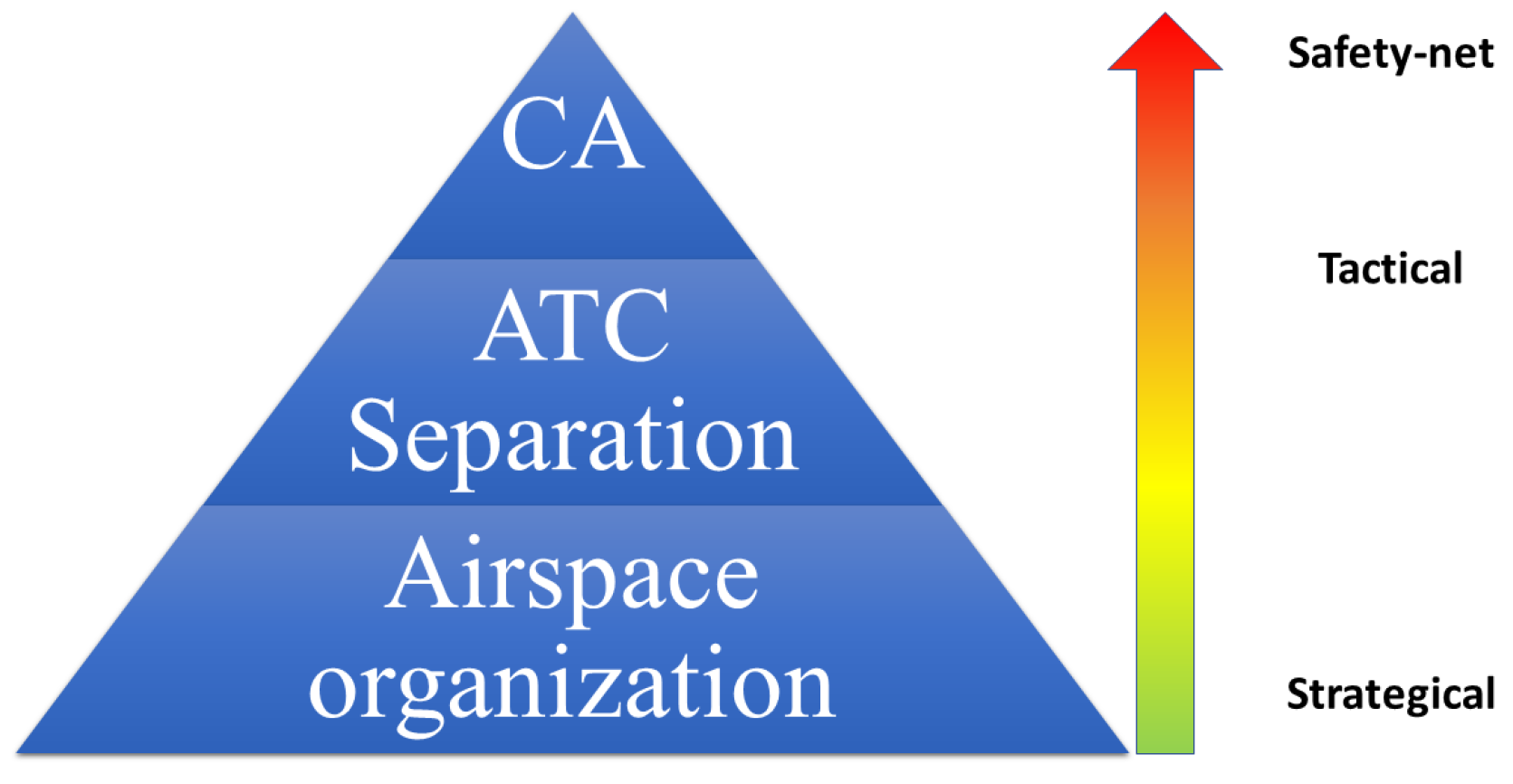

7]. It can be seen that the term “avoidance of collision” represents a whole range of mitigation strategies and should not be confused with the term “collision avoidance” (CA) which represents last resort actions/maneuvers. These last resort actions take place when other mitigation strategies, like airspace organisation and air traffic control (ATC) separation services, have failed and is a part of avoidance of collision. This layered approach, as described before, can be seen in

Figure 1.

2.2. Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System

During the early years of aviation, there only were a few mid-air collisions (MACs). Due to the rapidly growing traffic density, mid-air collisions became more likely. A fatal accident in 1956 in Arizona, USA, with 128 casualties led to the founding of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the establishment of airspace segregation as a strategic mitigation for MACs. However, further accidents, involving human error and bad weather conditions, led to the cognisance that a collision avoidance system (CAS) is required to further improve safety. In the 1970s, the so-called Beacon Collision Avoidance System (BCAS) has been developed for low-density airspaces. The system got further enhanced for high-density airspaces into the Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System (TCAS) which is still in use today [

8].

A Collision Avoidance System consists of three major components: The traffic detection, the conflict detection and alerting component, and the avoidance component. The traffic detection component uses different sensors for locating nearby traffic. These sensors can be split into two categories: cooperative and non-cooperative sensors. Non-cooperative sensors like primary surveillance radars (PSRs) and cameras provide data that can be utilized to detect other aerial vehicles without the need to collaborate with them. Cooperative sensors on the other hand rely on the traffic to make themselves conspicuous. Examples for cooperative sensors are transponders, ADS-B, and FLARM. A detailed review of sensor technologies for detecting traffic is beyond the scope of this paper. There is extensive literature available for further reading [

9,

10,

11]. TCAS makes use of the transponder to identify nearby traffic. The advantage of choosing a cooperative sensor lies in the large range of the detection and the possibility of information exchange. Besides transferring position information via the transponder, the signal is also utilized to implement a method for maneuver coordination. With the growing presence of ADS-B equipped aircraft, also ADS-B signals are considered by TCAS to detect traffic in the vicinity [

8].

Once other traffic is detected, an evaluation takes place in order to determine, if the detected traffic poses a thread towards the ownship. This process is known as conflict detection. A situation where two aerial vehicles are in proximity to each other, so that a loss of separation may occur, is called an encounter. To describe the encounter characteristics, it is suitable to establish some parameters that define the geometry. The most crucial parameter for collision avoidance is the closest point of approach (CPA). This is the point in time where the intruder aircraft and the ownship are facing the minimum distance between them. The parameters "time to CPA" and "distance at CPA", can be defined for this point [

11]. The absolute distance between the ownship and the intruder is also called the slant range.

Due to limitations of the sensors, the intruder state may not be known in its entirety. While the pressure altitude could be easily determined and communicated via Mode C, TCAS was facing large horizontal position uncertainties in the pre-GPS era. The transponder enabled TCAS to determine the slant range and the closing rate, but the overall velocity vector of the intruder could not be estimated with a sufficient precision to determine the slant range at the CPA. For this reason, TCAS assumed the distance to CPA to be zero. Given the range, an altitude difference, and the closing speed between the ownship and the intruder, it is possible to define alerting thresholds. These alerting thresholds are utilized to decide on when to alert the pilot and issue a maneuver guidance to resolve the conflict. Since the velocity of transport aircraft can vary over a wide range, it is desirable to choose the time to collision as the alerting threshold quantity. TCAS defines two parameters, named Tau values, for this purpose: one for the estimated time to CPA, called the range test, and one for the time to co-altitude, called the altitude test. When both of these thresholds are passed, TCAS issues an alert. First, a traffic advisory (TA) is issued to inform the pilot about the detected traffic. When the situation deteriorates, resolution advisories (RA) are issued which contain mandatory maneuver guidance. The pilot must follow these RAs. It is worth noting that the range does not need to be purely horizontal. This is why the ACAS manual uses the term "collision plane" [

12]. An issue of this approach is that slow approaching intruders, due to their low closing speed, can get very close to the ownship before reaching the alerting threshold. Due to this reason, a spatial protective volume is spanned in addition to the pure temporal alerting. The cylindrical volume is defined by a range radius called distance modification (DMOD) and a half-height called z-threshold (ZTHR). If these volumes are infringed, a RA is also issued. The alerting logic was further changed to take into account that the distance at CPA might not be zero. A geometric optimized parameter for the range test, called modified Tau or Tau-Mod, is therefore used instead of the original Tau parameter for the range test. While the derivation and the detailed logic of TCAS is sophisticated and beyond the scope of this paper, it is worth mentioning that TCAS adapts the parameters by choosing one of seven so-called sensitivity levels. As the aircraft performance degrades with increasing altitude, larger thresholds are used for alerting [

12,

13]. The approach of defining temporal alerting thresholds and protection volumes has been adapted and enhanced by modern DAA systems.

For completeness reasons, it shall be mentioned here that there were three planned TCAS variants, from which two entered service. TCAS I represents the most cost-efficient TCAS implementation. It does only provide TA functionality while not being able to issue RAs. TCAS II, the most common variant, provides TA and RA functionality as described before. It was the first variant that went into service as it was introduced in 1990 as Version 6. In 2000, version 7 got introduced and was mandated by ICAO for turbine-powered aircraft with more than 19 passengers or a maximum take-off mass (MTOM) larger than 5700kg. TCAS II is the most used TCAS variant and is still in service today. In Addition to TCAS II with its pure vertical guidance, a variant called TCAS III had been developed to also provide horizontal RAs, based on a more complex directional antenna system. However, it was found that the results were not satisfying which is why TCAS III never entered service [

14].

2.3. Remain Well Clear

Besides collision avoidance, the pilot of a manned aircraft must fulfil other responsibilities in order to satisfy the overall duty of avoidance of collision. One of these is the responsibility to keep well clear from all other traffic. While there are airspace classes where the pilot has to provide the separation by themself, there are also airspace classes where the ATC provides separation services. However, these separation services do not relief the pilot from its responsibility to practice vigilance towards proximate traffic [

7]. For UAS, where a pilot is either in a ground station with limited situational awareness or, in case of a full autonomous operation, not existing, there must be other means to support the pilot or command unit of the vehicle to keep well clear. Concerns arose that for traffic operating under Visual Flight Rules (VFR), a collision avoidance system is not sufficient for UAS. Thus, the concept of remain well clear (RWC) was introduced. It shall be noted here that, in general, DAA systems do not necessarily include collision avoidance (CA) functionality. A separate CAS can be used instead. RTCA DO-365C defines such airborne DAA systems without CA capability as class 1 systems. In theory, the term DAA system can also cover a pure CA system without RWC functionality. However, standard terminology usually assumes that a DAA system provide RWC functionality while the term CA system is used for systems that provide pure CA functionality. This paper will assume that both functionalities are provided by one DAA system, if not stated differently. Since the ICAO definition of well clear is only of qualitative nature, different standards define quantitative volumes, similar to the protection volume used for collision avoidance for manned aircraft, to be used as a DAA well clear (DWC) volume.

2.4. Encounter Modelling

The main objective of certifying a DAA system is to provide evidence that the system is able to provide a safety benefit for the overall operation. For this purpose, different performance metrics can be defined. One major group of performance metrics are the so-called risk ratios. Risk ratios are defined as a ratio of probabilities that describe how likely it is that a conflict can be resolved. The probability of conflict resolution having a DAA system equipped is divided by the probability of conflict resolution without having a DAA system equipped. By doing so, it can be demonstrated that equipping a DAA system will result in an actual improvement in safety. These risk ratios can be applied for different conflicts like Loss of DWC (LWC) conflicts, unequipped intruder near mid-air collision (NMAC) conflicts, and TCAS equipped intruder NMAC conflicts. Standards usually adapt the ICAO thresholds for risk ratios to derive additional requirements, like alerting times. These risk ratios are calculated by defining a set of encounters. Based on these encounters, simulations are performed to check, if an infringement of the RWC or NMAC volume takes place. For each encounter, these simulations are performed twice. Once without the DAA system and once with the DAA system able to interact. To assure that the defined encounters are representative for real traffic, encounter models have been developed. These models are based on data acquired by long-term observations of different airspace classes. The data is then filtered for conflicts, processed, and a feature extraction takes place. The identified features are then used to produce a model which is capable of generating realistic encounters. Encounter models are in general divided into two different types: correlated and uncorrelated encounter models. The difference between those is that for correlated encounter models, the extracted conflicts involve transponder-equipped aircraft. Therefore, it is likely that at least one aircraft was in contact with the ATC and received an ATC message concerning the intruder before the collision avoidance system becomes active. The trajectories of both aircraft are therefore correlated. Common encounter models are the MIT Lincoln Lab Encounter Models and the Eurocontrol CREME Encounter model. Extensive literature on the development of such encounter models is available [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

3. Applicable Detect and Avoid Standards

Although the regulatory framework poses requirements on a DAA system, solely fulfilling these mandatory requirements is compulsory but not sufficient to provide enough evidence about the safety of a DAA system. In order to achieve a safe DAA system, different standards have been developed to provide additional requirements and guidelines to promote the development of safe and reliable DAA systems. While the full scope of these standards is too extensive to be covered in a paper, an overview of these standards, their key points, and mayor differences shall be discussed here. The focus is put on the performance requirements on the DAA logic as it is the central part of the system. By doing so, a basis to select and understand a given standard for a particular DAA system use case is provided. Furthermore, the requirements on the system logic can be used to verify the safety benefit of research algorithms. It shall be mentioned here that, while the most standards are primarily developed for certified UAS, some of these standards may also be applied within the specific class. However, a direct link between a standard and the applicable Air Risk Class is seldomly found. Instead, a matching of requirements, concerning minimum and maximum altitude, vehicle weight, and dimensions must be performed in order to recognize a standard as suitable for a given application.

The main institutions that define standards to certify DAA systems for civil UAS are the Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics (RTCA), EUROCAE, and the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) International. Each of these organizations has developed one or more standards to guide the DAA system development process. These standards adapt the regulatory requirements and define concepts that allow engineering a system that complies with these requirements. Further requirements and guidelines are then derived from these concepts. There are multiple types of standards used to describe DAA systems. The Operational Services and Environment Definition (OSED) standards describe a DAA system in its operational context and describe the DAA logic, mostly in a qualitative manner. A Minimum Aviation System Performance Standard (MASPS) derives characteristics and functional requirements for a DAA system on a system level and allocates them to specific components. In addition to MASPS, interoperability requirements standards (INTEROP) are sometimes introduced to ensure compatibility between different segments. Depending on the complexity and the quantity of requirements, interoperability requirements can also be part of a MASPS document. A Minimum Operational Performance Standard (MOPS) represents the most refined description of the here mentioned types by defining requirements for a specific component [

21]. Also this definition originates from EUROCAE, it is in line with the RTCA definition.

3.1. RTCA DO-365C

The RTCA DO-365 “Minimum Operational Performance Standards (MOPS) for Detect and Avoid (DAA) Systems” standard was released in 2017 and was the first standard for DAA for UAS. It defines performance requirements for DAA system components. Since then, three new revisions have been released, with the latest being DO-365C from September 2022. Apart from some minor changes and expansions, these revisions extended the original content by introducing terminal operations and Airborne Collision Avoidance System (ACAS) Xu compatibility. ACAS Xu will be introduced in the following sub chapter. Furthermore, the OSED was moved from Appendix A of the document to the standalone standard DO-398 [

22].

In contrast to other DAA standards, the DO-365 considers only the RWC functionality. Collision Avoidance is expected to be provided by a separate system. The standard can be applied when operating UAS, having a Maximum Take-off Mass (MTOM) above 55lbs, under Instrument Flight Rules (IFR) in the airspace classes B-E and G between 400 ft AGL and FL 180. The standard allows for different cooperative and non-cooperative surveillance methods.

A major aspect of the standard is the alerting logic. The definition of the alerting criteria is comparable to the alerting in TCAS which motivated the coarse overview of its alerting logic found in the preceding chapter. Like TCAS, the defined RWC functionality uses temporal parameters as well as protection volumes for temporal and spatial alerting. However, there are some major differences to the alerting logic of TCAS. First, in contrast to TCAS, DO-365 uses DMOD as a purely horizontal parameter and not as a parameter in the collision plane. Furthermore, the temporal parameter, modified Tau, of this document does not only incorporate the closing speed but also the slant range itself. Although the definition is changed, the threshold values are usually identical with the ones defined by TCAS. While some standards adapt these values with the sensitivity level, like TCAS does, this standard uses a static value of 35 seconds, which originates from a sensitivity level of 7, the highest level of TCAS. In Addition, modified Tau, is not directly used for alerting. Instead, it is rearranged for the distance to span a second protection volume. This protection volume is again associated with a temporal alerting threshold. Last, this standard defines three types of alerts, which will be introduced later. It can be seen that neither explanations for these decisions, nor equations are mentioned here. This is due to the complexity of the logic and its derivation. Rather than describing the logic in detail, only the broad concepts behind the logic shall be explained here. For a comprehensive discussion of these topics, it is recommended to review the standard itself. This holds also true for the different parameter variants. Similar to TCAS, DO-365 adapts some of its parameters to changing conditions. But instead of making these parameters altitude dependant, they change with the method of detection (cooperative/non-cooperative), the mission state (En-route/Terminal area), the type of alert and a set of special cases. For example, the DMOD threshold for en-route cooperative detection is given with 4000ft for all types of alerts while the height threshold is set to 450ft or 700ft, depending on the type of alert [

22].

In order to generate appropriate alerts for a given encounter, three types of alerts are defined for RWC: preventive alerts, corrective alerts, and warning alerts. Each alert type is associated with a corresponding alert level according to FAA Advisory Circular (AC) 25.1322-1. While the preventive and corrective alert types are caution level alerts, the warning alert type is a warning level alert. These alert types provide detailed requirements on when to alert for a given encounter. This is achieved by defining three volumes: the Hazard Alert Zone (HAZ), the May Alert Zone (MAZ), and the Non-Hazard Zone (NHZ). The Hazard Alert Zone defines a volume where an alert must be issued once this volume is infringed. It is spanned by an HMD threshold, an altitude difference threshold, and a temporal threshold. The NHZ is spanned in an equal manner but with different values. Additionally, while the HAZ volume covers the space below the defined threshold values, the NHZ volume covers the space beyond. Within the NHZ volume, alerts are considered nuisance alerts. Consequently, alerting when operating in this region, is prohibited. The remaining space between the HAZ and the NHZ is called the May Alert Zone (MAZ). Within this zone, an alert may be issued. While there are early and late thresholds for alerting within this zone, there is also a minimum average time of alerting defined. It must be proven that the average alerting time of the system is greater than the corresponding threshold. Depending on the operation, there are different tables available that define all required thresholds for en-route and terminal operations as well as for cooperative and non-cooperative detection [

22].

3.2. RTCA DO-386

Besides the approaches of the RTCA special comitee SC-228 and the EUROCAE working group WG-105 to define new standards for DAA systems in form of the DO-365 and ED-271, respectively, there have been ongoing efforts to enhance the TCAS system and the associated ACAS standards. These efforts are bundled within the ACAS X project. Different sub-types have been defined to meet the evolving requirements of aviation. While ACAS-Xa and ACAS-Xo are developed for manned fixed-wing aircraft, ACAS-Xu and ACAS-sXu are developed for large and small unmanned aircraft, respectively [

14]. At the time of writing, there is an additional variant under development. ACAS-Xr will define an ACAS system for rotor aircraft.

The main objectives of enhancing the ACAS system are the improvement of the risk ratio, a reduction of nuisance alerts, and the utilisation of new surveillance methods. Furthermore, horizontal RAs have been introduced within ACAS-X so that these systems can issue both, horizontal and vertical RAs. Another major change can be found within the alerting logic. Instead of using a heuristic-based decision process, the ACAS-X systems use a probabilistic approach [

23]. A Markov Decision Process (MDP) has been used to model possible actions and the corresponding collision risks and is solved by applying Dynamic Programming (DP). This process generates a lookup table which is used during runtime to determine appropriate alerts, depending on the discretized encounter state [

8]. However, the probabilistic approach cannot be directly compared to the alerting parameters of conventional algorithms, which are usually realized by decision trees. In order to compare both approaches, it is reasonable to directly assess the performance of the implemented logic. However, of all introduced standards, only the standards of the ACAS-X family provide algorithms for a concrete implementation. Therefore, a performance assessment of logic implementations cannot be achieved when purely basing on the given documents. There is literature available that compares the performance of different logic implementations [

24,

25].

RTCA DO-386 "Minimum Operational Performance Standards for Airborne Collision Avoidance System Xu (ACAS-Xu)" defines operational requirements for the ACAS-Xu system and the associated equipment. ACAS-Xu is considered as an implementation of DO-365 and differentiates itself from the manned ACAS-X variants as it is designed to utilize a wide range of surveillance methods and to encounter vehicles with significantly varying performance characteristics. Besides using transponder and ADS-B/R for hybrid surveillance, also an air-to-air radar (ATAR) is used which presents an acceptable means to validate ADS-B data when a transponder is not available. In order to align with DO-365, ACAS-Xu provides not only CA functionality but also RWC alerting according to DO-365. This is achieved by introducing an optimized look-ahead process to meet the system time requirements. To combine both, RWC and CA capabilities, it is suitable to adapt the alerting. For this reason, DO-365 accepts that ACAS-Xu does not issue RWC warning alerts, as the combination of caution level alerts and RAs have been proven to be sufficient to fulfil the safety objectives. Moreover, the CA function of ACAS does not provide any TAs since the RWC alerts are considered as sufficient. In addition to the alerting, ACAS-Xu is also capable of providing outputs which can be used to implement an automatic maneuver execution but does not consider automatic manoeuvring within the standard. Likewise, information display and aural alerts are not part of the standard as ACAS-Xu only deals with onboard components, while alerting equipment is part of the ground station. Users are redirected to DO-365 and DO-385 (ACAS-Xa/Xo) for human-machine interface (HMIs) design [

14].

3.3. EUROCAE ED-271

During the recent years, efforts have been made to develop an European DAA system which is, in contrast to the ACAS-Xu system, tailored to the European airspace. In order to assure that the system will be safe to operate, the EUROCAE WG-105 has been developing new standards which will be used to certify the DAA system. One of these standards, which is already published, is the ED-271 “Minimum Aviation System Performance Standard (MASPS) for Detect and Avoid [Traffic] for Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems in Airspace Classes A-C under IFR”. In contrast to the DO-365, which is considered a MOPS, a MASPS define high-level system requirements instead of defining requirements for concrete components of a system implementation, like MOPS do. Consequently, the ED-271, as a MASPS, can only partly be compared to a MOPS like DO-365. A major difference between both standards can be found within the provided functionality. While DO-365 does only provide RWC functionality, ED-271 comprises both, RWC and CA functionality. However, the DO-365 describes the introduced RWC functionality in greater detail than the ED-271. The latter document, for example, does not specify concrete alerting thresholds.

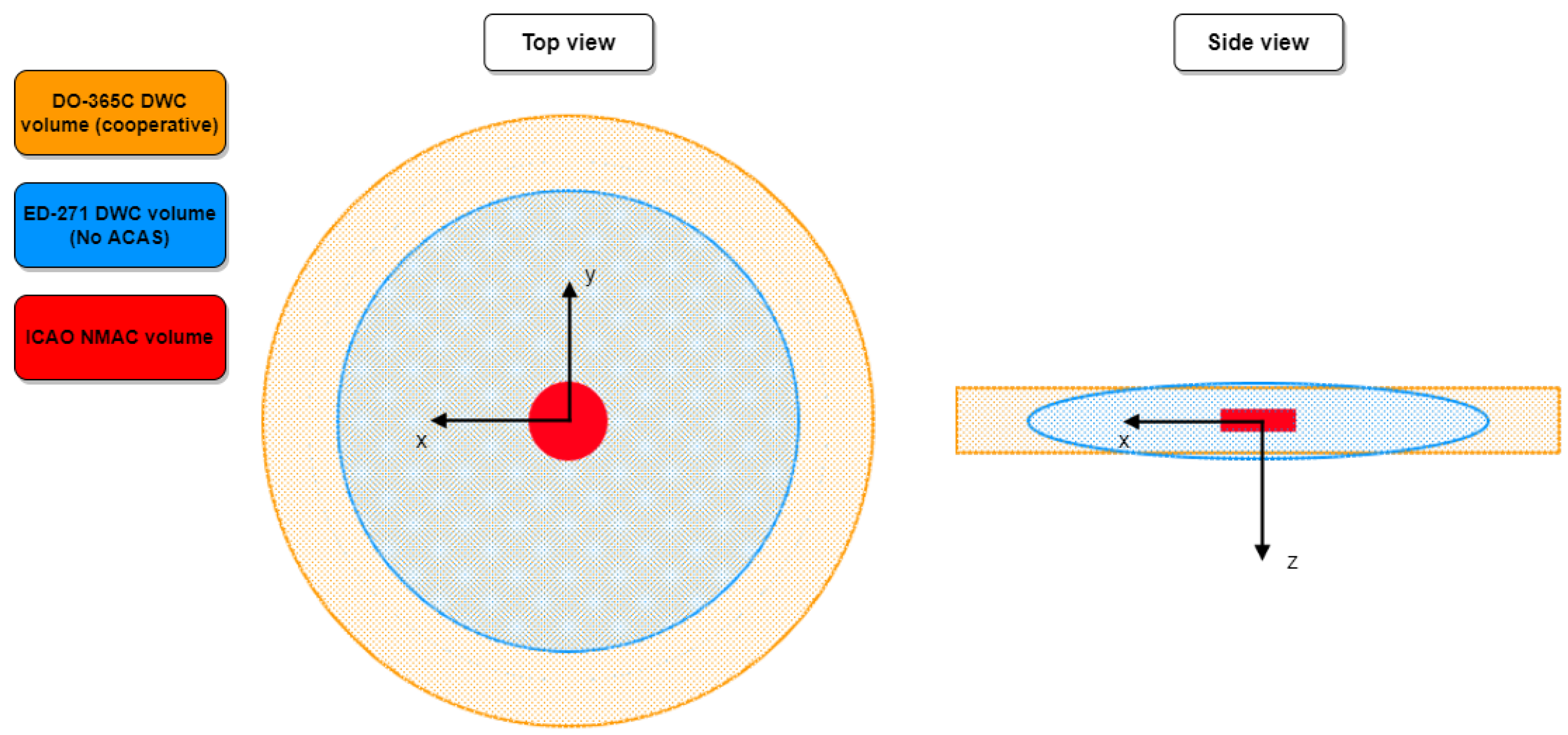

The protective volume for DWC is set to be a spheroid of a horizontal half-axis of 0.5 NM (3038ft) and a half-height of 500ft when the intruder is not indicating ACAS equipage. In case that the intruder reports to possess ACAS capability, the defined values are compared to the values given for ACAS range in ICAO Annex 10 and the greater of both variants is chosen. Besides the numerical values and the shape, the ED-271 differs from the DO-365 DWC definition by choosing the threshold based on intruder CA capabilities and not intruder surveillance equipment. Furthermore, it adopts the NMAC volume, a cylinder of 500ft horizontal half-axis and 150ft half-height, and the temporal thresholds from the ICAO ACAS definition. An exemplary visualisation of protection volumes can be seen in

Figure 2. For the DO-365 DWC volume, the en-route, cooperative intruder, warning alert is depicted. The ED-271 DWC volume corresponds to the described spheroid when the intruder does not report ACAS capability as it is independent of the sensitivity levels. It can be observed that the ED-271 DWC volume is smaller than the DO-365 volume. Nevertheless, it is not possible to deduce performance assumptions from this fact as there are no alerting thresholds specified for the ED-271 DWC volume. Besides defining the protection volumes, the standard establishes a set of high-level requirements which cover a wide range of aspects like link performance, TCAS interoperability, and operational requirements. It is recommended to review the original source for an in-depth presentation of all requirements and their corresponding derivation [

26]. Theunissen et. al. made a comparison between the RWC concept as defined in ED-271 and the one from DO-365 which further elaborates on the similarities of the caution level alerts and the design decision of DO-365 to issue also warning level alerts for RWC [

27]. However, it is worth noting that the comparison of the DO-365 values is done against a project which was used to derive the RWC requirements. Not all aspects of the project are incorporated into this standard. At the time of writing, there is a revision for ED-271, as well as a corresponding DAA MOPS, derived from the MASPS, under development. The revision will be valid for all airspace classes, instead of covering only airspace classes A-C, like the current revision does.

3.4. TCAS Interoperability

When operating within ARC-d or the certified category, a DAA system must ensure that it does not degrade the CA capabilities of the ownship as well as the surrounding traffic. If the DAA system does not include CA functionality, it must be ensured and demonstrated that the RWC functionality does not deteriorate the CA system. If the DAA system incorporates CA functionality, it must be interoperable with other CA systems. It has been shown by means of simulations that the risk of a collision is higher, if both aircraft are TCAS equipped, but do not coordinate their resolutions than having an encounter where one aircraft is unequipped. Therefore, it is essential to coordinate RAs with the intruders. EUROCAE ED-264 and RTCA DO-382 define interoperability requirements for CA systems. They include communication-, coordination-, and performance considerations. An integral part of the interoperability considerations is the coordination protocol. Depending on the equipment of the aircraft involved in the encounter, a coordination protocol is chosen. A communication is always established between two aircraft. If a multi-aircraft encounter is present, each aircraft communicates pair-wise with the other ones. There are three protocols: active coordination, passive coordination, and responsive coordination. Active coordination is chosen when both aircraft are equipped with a CA system and a 1090 MHz transponder as an active surveillance system. This enables both aircraft to communicate with each other. The aircraft with the lower ICAO address is considered the master in the coordination and can overwrite commands from the slave aircraft. Once the first aircraft has detected a conflict and issues a directional sense RA, a vertical RA complement (VRC) is sent to the intruder, e.g., if the TCAS logic of the first aircraft decides to issue a downward sense RA, it also sends a “do not pass below” VRC. Such VRCs can be reversed by the master aircraft if deemed necessary. The passive coordination protocol uses a similar approach, but is applied when both aircraft are equipped with a CA system and ADS-B but no aircraft has a transponder. In this case, the communication is handled by the passive surveillance system, broadcasting the messages as so-called operational coordination messages (OCMs). In case that only one aircraft is equipped with a transponder, the responsive coordination is chosen. Since the transponder-equipped aircraft is also capable of performing the active coordination protocol with other intruders, a so-called senior role is assigned to it. The other aircraft is not capable of responding to the transponder interrogations and is therefore assigned with the junior role. In comparison to the master and slave roles from the active and passive coordination, the senior role aircraft is not allowed to consider any messages received from the junior aircraft and must discard them immediately. Independent of the equipment, aircraft can be designated as junior aircraft by a competent authority. Given that case, the actual aircraft equipment might be suitable to perform active coordination but is not allowed to. Nevertheless, the equipment can be utilized for communication purposes. This results in two sub-types of the responsive coordination: modified active and modified passive. For a detailed explanation of the different protocols, it is recommended to review the interoperability standards directly [

28,

29].

3.5. ASTM F3442/F3442M-23

The ASTM F3442/F3442M-23 standard focuses on performance requirements for UAS operating in the specific category. It defines DAA system performance requirements for operations in the air space classes B-E and G below 400ft-1200ft AGL, depending on the airspace class. Besides the airspace classes, the standard poses additional limitations on the airspace risk class as defined by JARUS SORA 2.0. While operating in ARC-a to ARC-c is allowed, for operation in ARC-d, other standards must be applied to certify the DAA system. To validate the DAA system performance, the standard uses the ICAO risk ratios for NMAC and LWC, for both, cooperative (ADS-B) and non-cooperative intruders. It must be proven by means of encounter modelling that the system is able to achieve these risk ratios. A noticeable difference towards other standards is the exemplary evaluation of simulations to derive surveillance performance metrics. By complying with the derived requirements, surveillance systems can be considered to comply with the defined risk ratios without performing encounter simulations. Since the velocity of UAS operating under the applicable conditions is expected to be sufficiently low, a narrow DWC volume of 2000ft radius and 250ft half-height has been defined by the committee, while the NMAC volume possesses a 500ft radius and 100ft half height. It shall be noted here that the ASTM standard does not define specific alerting times. It just mentions that the latest time for alerting is the infringement of the DWC volume. When developing a DAA system according to this standard, encounters should be simulated with different alerting thresholds to identify an alerting interval which enables the DAA system to meet the defined risk ratios without issuing too many nuisance alerts. In comparison to DAA system standards for higher risk application in the specific category and certified systems, this document focuses only on high level requirements and does not include extensive requirements for the equipment, used by the system [

30].

3.6. RTCA DO-396

All of the previously introduced standards are either targeting large UAS to operate within airspace classes where manned aircraft usually fly or small UAS which operate in low-level in uncontrolled airspace. In order to enable UAS with a MTOM < 55lbs to operate in higher altitudes, the ACAS-sXu standard, RTCA DO-396, has been developed. It inherits the working principle of the ACAS-X systems but tailored the system requirements and architectural aspects to smaller UAS. It shall be mentioned here that the standard does not use the term “small UAS”, since it is linked to the definition of 14 CFR §107.3 which incorporates a maximum dimension of 25ft and an upper MTOM boundary of 55lbs. Instead, the document introduces a definition of the term “smaller UAS” which still inhabits a maximum dimension of 25 ft but does not restrict the MTOM. By applying this definition as a use case for the standard, it exceeds the scope of DO-365C. In its place, the ASTM F3442/F3442M standard serves as a reference for ACAS-sXu. Major aspects like the risk ratios, the well clear boundary, vehicle performance requirements, and the absence of a MTOM limit within the DO-396 can be traced back to it. Additionally, the necessity to be capable of hovering is a requirement that is inherited from F3442/F3442M.

As the maximum dimension is still restrained and the MTOM is still limited by efficiency considerations, the capability of a smaller UAS to carry sufficient onboard sensory and computing power for DAA functionality is not guaranteed. Therefore, ACAS sXu does not define a specific architecture. All subsystems associated with ACAS-sXu can be onboard, offboard, or a mixture of both. However, when using offboard components for ACAS-sXu, the standard demands vulnerabilities against link loss to be addressed. While offering a range of approaches concerning the architecture, the choice of surveillance systems is constrained. DO-396 requires an ADS-B In as a cooperative detection method and at least one non-cooperative surveillance method if non-cooperative traffic can be expected. The use of a transponder and ADS-B Out, however, is not permitted. By doing so, other manned traffic and large UAS cannot detect and coordinate with smaller UAS by utilising active surveillance. This, and the small size of the UAS is assumed to render the UAS invisible to such traffic. Subsequently, the responsibility for RWC and CA lies solely on the smaller UAS which are required to always give way to the specified intruder types. Additionally, the UAS is not allowed to receive ATC separation services.

When considering the conflict detection and alerting function, a few deviations can be spotted in comparison to ACAS-Xu. ACAS-sXu provides RWC and CA functionality but does not possess separate functions for these tasks. Since it does not comply with the DO-365, additional RWC alerts are not required. Instead, only one type of alert is issued that enables to mitigate NMACs and loss of DWC (LWC) with the required risk ratios as referenced in F3442/F3442M. An additional difference is the support of ACAS-sXu for terrain awareness. It is assumed that, even though surpassing the 400ft AGL boundary, sXu equipped UAS are still operating within ground proximity. As a vertical avoidance maneuver could lead to controlled flight into terrain, it is possible to provide ground information to consider terrain when planning the maneuver. This is achieved by representing the terrain and obstacles as stationary traffic. Although this functionality is provided, the algorithm is not optimized for avoiding it which is why the functionality is only considered a terrain awareness function and not a terrain avoidance function. Furthermore, real traffic is always prioritised over the stationary pseudo-traffic [

31]. This prioritisation differs from ICAO Doc 8168 which requires the inverted prioritisation for manned aircraft [

32]. Nonetheless, because a collision of a smaller UAS with the ground is assumed by the standard to be less severe than a collision with a manned aircraft, the prioritisation represents a sound conclusion. Finally, the DO-396 is the first standard which suggests CA between smaller UAS. With a defined NMAC volume of 50 ft horizontal distance and 15 ft vertical distance, it allows the system to also avoid small intruders. RWC functionality is said to not be required, due to the decreased severity and likelihood of encounters between smaller UAS. To coordinate these encounters, different aspects are proposed, like incorporating smaller UAS communication, Advanced Air Mobility, Urban Air Mobility, and UAS traffic management concepts. These concepts and the corresponding technologies, however, are rather a broad draft of what could be possible than a utilizable framework. Consequently, the proposals do not provide a concrete guidance on how to apply any of these concepts. Although the standard defines objectives for this type of encounters, implementing them is not a hard requirement [

31].

3.7. Operational Services and Environment Description Standards

Since the presented standards are tailored to specific applications, it might be reasonable to develop a new standard, if the existing ones are not matching the intended operation. To provide guidance during a standard development, so-called Operational Services and Environment Description (OSED) standards have been developed. Like the name suggests, these standards describe operational environments by defining assumptions and deriving requirements and recommendations from them. The approach to define standards to be used for defining new standards may seem strange at first but has proven to be a prolific approach, as it mirrors and accompanies the system engineering approach of requirement breakdown. The most popular OSEDs are the DO-398 “Operational Services and Environment Definition (OSED) for Unmanned Aircraft Systems Detect and Avoid Systems (DAA)” and the newly released ED-313 “Operational Services and Environment Definition for Detect and Avoid [Traffic] in Class A-G Airspaces under IFR“. The former was initially a part of DO-365, found in Appendix A. With revision C, the Appendix got removed and released as an independent standard [

22,

33]. The latter supersedes the standards ED-238 “Operational Services and Environment Definition (OSED) for Traffic Awareness and Collision Avoidance (TAACAS) in Class A, B and C Airspace for Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS) operating under Instrument Flight Rules” [

34] and ED-258 “Operational Services and Environment Definition for Detect and Avoid [Traffic] in Class D-G Airspaces under VFR/IFR” [

35]. Both, the DO-398 and the ED-313 identify several actors in an encounter: the remote pilot, the DAA systems, the intruder pilot, and the ATC. The interactions between these actors are specified in flow charts within the standards to visualise the process of resolving an encounter. While the overall processes, defined in these standards, are in line with the ICAO definitions and are therefore similar to each other, there are certain differences within the implementation details worth noticing. Foremost, like DO-365, DO-398 does only consider RWC functionality. This has the direct effect that the standard does not consider Class A airspace to be a driver of DAA requirements as separation services are provided by the ATC. However, operating the system in this airspace class is still allowed [

33]. ED-313 on the contrary considers CA and RWC functionality, leading to major deviations between ED-313 and Do-398 regarding operational, and interoperability requirements. Additionally, DO-398 inherits warning type alerts for RWC, enabling the remote pilot to perform associated RWC maneuvers without involving the ATC while receiving ATC services. ED-313 follows the ICAO guidance and implements only caution level alerts for RWC functionality [

36]. Even though there are some further differences between both standards, the decision of choosing one standard over the other can be narrowed down to decide on whether to include CA capabilities within the DAA system or not as the major differences between both standards are rooted within this design decision.

While ED-313 and DO-398 are both addressing operations within the classic airspace, there is also an OSED for operations within very low-level (VLL), EUROCAE ED-267 “Operational Services & Environment Definition (OSED) for Detect & Avoid in Very Low-Level Operations”. In comparison to the other OSEDs, ED-267 is describing the environment in a much broader context. Instead of just focusing on DAA for traffic, also fixed and mobile obstacles, terrain, hazardous weather, wildlife, and humans (on the ground) are considered due to the ground proximity during operations. Even though a lot of hazards are identified, the requirements derived in this standard are less concrete than the requirements of the other OSEDs. Therefore, it is recommended to additionally review ED-313 and/or DO-398 as a guidance for typical DAA procedures when developing a VLL standard for DAA (traffic) [

37]. At the time of writing, there is no standard that uses ED-267 as a basis to define a DAA system.

3.8. Important Standard Characteristics

To conclude this section, the most important information, as presented above, shall be summarized and compared. Like mentioned before, the direct comparison between standards is in many aspects not desirable as they represent different types of standards (MOPS, MASPS, OSED, INTEROP) and suggest different architectures. Nevertheless, these documents have some main characteristics in common which are worth comparing. By doing so, it is possible to draw conclusions on selecting appropriate standards for a given application. These characteristics, as introduced in the preceding sub-chapters, are gathered in

Table 1. When parameters are inherited from other documents, like the applicable airspace classes for DO-386, the original source is mentioned within the brackets behind. It is worth mentioning that the mapping to initial ARC levels is, except for F3442/F3442M, not part of the official standards. The mapping is done based on the applicable airspace classes. Furthermore, an initial ARC level being marked as applicable does not guarantee that a system can be operated within this level, but that there is an intersecting set between the standard limitations and the SORA requirements. This is done to provide an initial guidance. It is suggested to directly compare a chosen standard with the current, applicable, regulatory documents, including possible strategic mitigations. Parameters, marked with

* or

†, indicate that the values change for different circumstances. While

* mark values, which are only valid for cooperative intruders encountered during en-route operations,

† prerequisites that the intruder does not report ACAS capability. These values have been chosen to demonstrate the order of magnitude of the corresponding parameters. For detailed information about these parameters, please refer to the associated document.

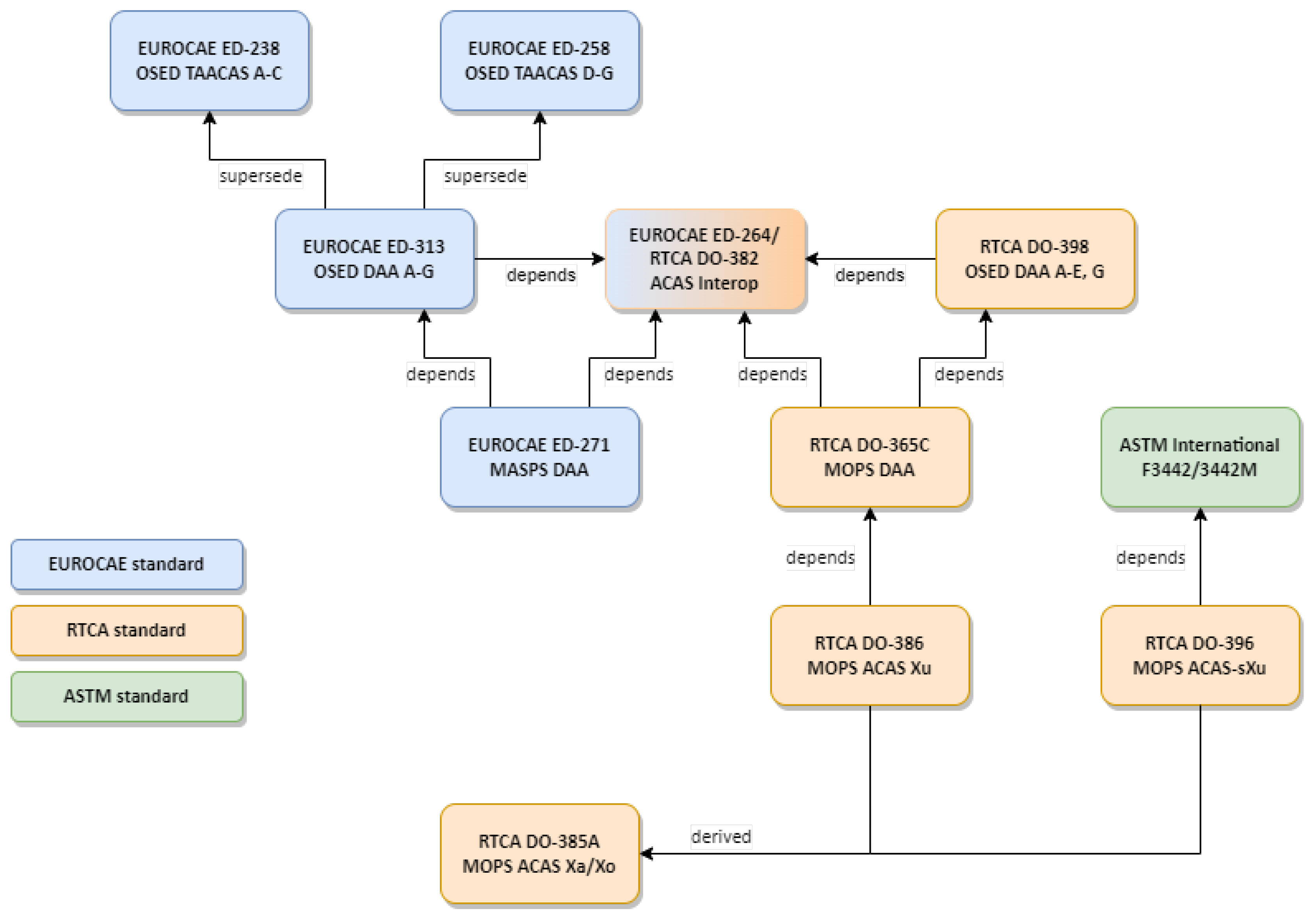

Figure 3 illustrates an overview of the hierarchical structure of the presented documents. It can be recognized that both, ED-271 and DO-365, are depending on an OSED and the joint interoperability standard ED-264/DO-382. DO-396 abstains on interoperability to manned aircraft and large UAS CA systems, like mentioned before. Additionally, DO-396 possesses a custom OSED in its Appendix A as F3442/F3442M is not considered an OSED, but a performance standard. Both ACAS-X standards for UAS, DO-386 and DO-396, inherit the main system architecture and the probabilistic conflict detection from the ACAS-X variants for manned aircraft, ACAS-Xa and ACAS-Xo. Consequently, they are marked as derived from this standard. It is worth mentioning that additional standards are available which define requirements for sensors which can be used for DAA. These standards are not mentioned here as they do not focus on the core aspects of DAA like the conflict detection and alerting.

4. Conclusions

This paper presents the currently available standards for DAA systems for UAS. It can be seen that the majority of efforts to develop a DAA system for UAS have been made for large UAS operating in the conventional airspace. The first standard being released is the RTCA DO-365 which defines a RWC system that is assumed to operate in parallel to a CA system. In contrast to the ICAO definition, one of the three defined RWC alerts from DO-365, the warning alert, is a warning level alert in accordance with AC 25.1322-1, while ICAO only suggests caution level alerts for RWC functionality. EUROCAE ED-271 on the other hand defines a DAA system that provides RWC and CA functionality and aligns its alerting fully with the ICAO guidance. Besides TAs and RAs, only one additional alert is defined which is issued by the RWC component. However, in the current revision, ED-271 applies only to airspace classes A-C and the system is missing a MOPS which specifies equipment requirements to make the system comparable to DO-365. Both, the revision to include all airspace classes and the MOPS standard, are currently under development. RTCA DO-386 inherits the DO-365 and introduces ACAS-Xu, which combines the traditional TCAS RA alerts with the RWC alerts from DO-365, but without issuing RWC warning level alerts and replacing the heuristic-based TCAS logic with a probabilistic model from the ACAS-X family. ASTM F3442/F3442M was the first standard to address DAA systems for smaller UAS. By tailoring classical approaches for RWC and CA functionality to the needs and constraints of smaller UAS, F3442/F3442M lays a basis for DAA systems that can be operated below ARC-d in the specific category. RTCA DO-396 adopted the approach of ASTM and developed ACAS-sXu, a derivation of the probabilistic ACAS-X family, as an implementation.

It is recognizable that there are still missing building blocks in the DAA standardization framework, especially for the DAA system as defined by ED-271 and DAA systems for VLL. However, the development efforts of DAA standards for large UAS are usually accompanied by efforts to design concrete systems and there are ongoing efforts to close the existing gaps in order to path the way for the corresponding system to be certified. It is expected that these systems will acquire regulatory approval and will be ready-to-market in the years to come. Even though a significant progress in developing DAA systems for smaller UAS has been achieved during the recent years, at the time of writing, there is still no broadly applied implementation of one of the systems, as defined by these standards. The reason for this can be recognized when comparing a standard for large UAS like the DO-365 and a standard for smaller UAS like the F3442/F3442M. While documents for large UAS are already very precise about the architecture and what auxiliary systems, like transponders, ADS-B, and air to air radars, shall be used, the standards for smaller UAS are not. A reason might be that large UAS are not as restraint in their size, weight, power, and cost (SWaP-C) requirements as smaller UAS are. Therefore, larger systems can benefit much more from the experience and the technology that has been developed for manned CA during the last decades. Smaller UAS, especially when operating in VLL, are facing major challenges like detecting manned traffic in regions with high clutter. Furthermore, smaller UAS-to-UAS DAA concepts are still under development. Detection of small UAS, encounter models for VLL, and maneuver coordination for smaller UAS are some of the main aspects which still require suitable solutions. While there is plenty of research done within these areas, none of these approaches have undergone the transition from prototype experiments to robust, safe, standardized, and secure subsystems. This is why standards like the DO-396 rather suggest a broad range of technologies than providing a narrow set of concrete subsystems to be used. Moreover, there is currently no standard available that applies to smaller UAS which are not capable of hovering. Future efforts have to address these issues in order to promote the safety of operations of smaller UAS. Additionally, apart from focusing on DAA for traffic, the OSED for VLL, ED-267, suggests DAA systems for other hazards like obstacles, terrain, hazardous weather, and wildlife. Additional research is required in these areas to foster the standardization and development of such systems.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC |

Advisory Circular |

| ACAS |

Airborne Collision Avoidance System |

| ADS-B |

Automatic Dependent Surveillance - Broadcast |

| AGL |

Above ground level |

| AMC |

Acceptable Means of Compliance |

| ARC |

Air risk class |

| ASTM |

American Society for Testing and Materials |

| ATAR |

Air-to-air radar |

| ATC |

Air traffic control |

| BCAS |

Beacon Collision Avoidance System |

| CA |

Collision avoidance |

| CAS |

Collision avoidance system |

| CPA |

Closest point of approach |

| DAA |

Detect and Avoid |

| DMOD |

distance modification |

| DP |

Dynamic Programming |

| DWC |

DAA well clear |

| EU |

European Union |

| FL |

Flight level |

| HAZ |

Hazard Alert Zone |

| HMI |

Human-machine interface |

| ICAO |

International Civil Aviation Organization |

| IFR |

Instrument Flight Rules |

| INTEROP |

Interoperability Requirements Standards |

| JARUS |

Joint Authorities for Rulemaking on Unmanned Systems |

| LWC |

Loss of DWC |

| MAC |

Mid-air collision |

| MASPS |

Minimum Aviation System Performance Standard |

| MAZ |

May Alert Zone |

| MDP |

Markov Decision Process |

| MOPS |

Minimum Operational Performance Standard |

| MTOM |

Maximum take-off mass |

| NHZ |

Non-Hazard Zone |

| NMAC |

Near mid-air collision |

| OCM |

Operational coordination message |

| OSED |

Operational Services and Environment Definition |

| PIC |

Pilot-in-command |

| PSR |

Primary surveillance radar |

| RA |

Resolution advisory |

| RoW |

Right of way |

| RTCA |

Radio Technical Commission for Aeronautics |

| RWC |

Remain well clear |

| SC |

Special comitee |

| SORA |

Specific Operations Risk Assessment |

| TA |

Traffic advisory |

| TCAS |

Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System |

| UTM |

UAS traffic management |

| UAS |

Unmanned aircraft systems |

| VFR |

Visual Flight Rules |

| VLL |

Very Low Level |

| VRC |

Vertical RA complement |

| WG |

Working group |

| ZTHR |

Z-threshold |

References

- Opromolla, R.; Fasano, G.; Accardo, D. Conflict Detection Performance of Non-Cooperative Sensing Architectures for Small UAS Sense and Avoid. In Proceedings of the 2019 Integrated Communications, Navigation and Surveillance Conference (ICNS), 2019, pp. 1–12. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2019/947 of 24 May 2019 on the rules and procedures for the operation of unmanned aircraft: COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2019/947, 2019.

- European Commission. COMMISSION DELEGATED REGULATION (EU) 2019/945 of 12 March 2019 on unmanned aircraft systems and on third-country operators of unmanned aircraft systems: COMMISSION DELEGATED REGULATION (EU) 2019/945, 2019.

- European Commission. COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2021/666 of 22 April 2021 amending Regulation (EU) No 023/2012 as regards requirements for manned aviation operating in U-space airspace: COMMISSION DELEGATED REGULATION (EU) 2021/666, 2021.

- European Commission. COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2021/665 of 22 April 2021 amending Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/373 as regards requirements for providers of air traffic management/air navigation services and other air traffic management network functions in the U-space airspace designated in controlled airspace: COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2021/665, 2021.

- European Commission. COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2021/664 of 22 April 2021 on a regulatory framework for U-space: COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2021/664, 2021.

- ICAO. Annex 2: Rules of the Air, 2005.

- Kochenderfer, M.J.; Holland, J.E.; Chryssanthacopoulos, J.P. Next-Generation Airborne Collision Avoidance System. In Lincoln Laboratory Journal; 2012; Vol. 19, pp. 17–33.

- Schalk, L.M.; Peinecke, N. Detect and Avoid for Unmanned Aircraft in Very Low Level Airspace, 2021.

- Hottman, S.B.; Hansen, K.R.; Berry, M. Literature Review on Detect, Sense, and Avoid Technology for Unmanned Aircraft Systems. Technical Report DOT/FAA/AR-08/41, FAA, Washington, D.C., 2009.

- Fasano, G.; Accado, D.; Moccia, A.; Moroney, D. Sense and avoid for unmanned aircraft systems. IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine 2016, 31, 82–110. [CrossRef]

- ICAO. Airborne Collision Avoidance System Manual, 2006.

- ICAO. Annex 10 Volume IV: Surveillance and Collision Avoidance Systems, 2014.

- RTCA. DO-386: Minimum Operational Performance Standards for Airborne Collision Avoidance System Xu (ACAS Xu), 2020.

- Kochenderfer, M.J.; Edwards, M.W.M.; Espindle, L.P.; Kuchar, J.K.; Griffith, J.D. Airspace Encounter Models for Estimating Collision Risk. Journal of Guidance, Control, and Dynamics 2010, 33, 487–499. [CrossRef]

- Kochenderfer, M.J.; Espindle, L.P.; Kuchar, J.K.; Griffith, J.D. Uncorrelated Encounter Model of the National Airspace System Version 1.0. In MIT Lincoln Laboratory Report ATC-345; 2008.

- Kochenderfer, M.J.; Espindle, L.P.; Kuchar, J.K.; Griffith, J.D. Correlated Encounter Model for Cooperative Aircraft in the National Airspace System Version 1.0. In MIT Lincoln Laboratory Report ATC-344; 2008.

- Weinert, A.; Harkleroad, E.; Griffith, J.; Edwards, M.; Kochenderfer, M. Uncorrelated Encounter Model of the National Airspace System Version 2.0; 2013.

- Manfredi, G.; Jestin, Y. An Introduction to Fast Time Simulations for RPAS Collision Avoidance System Evaluation, 2018.

- SESAR. SESAR PJ.13-Solution 111: Description of Collision Avoidance Fast-time Evaluator (CAFE) Revised Encounter Model for Europe (CREME), 2022.

- EUROCAE. EUROCAE Documents (ED) categories and definitions, 2020.

- RTCA. DO-365C: Minimum Operational Performance Standards for Detect and Avoid Systems, 2022.

- RTCA. DO-385A: Minimum Operational Performance Standards for Airborne Collision Avoidance System X (ACAS X) (ACAS Xa and ACAS Xo), 2023.

- Davies, J.T.; Wu, M.G. Comparative Analysis of ACAS-Xu and DAIDALUS Detect-and-Avoid Systems, 2018.

- Grebe, T.; Kunzi, F. Detect and Avoid (DAA) Alerting Performance Comparison: CPDS vs. ACAS-Xu. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/AIAA 38th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), 2019, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- EUROCAE. ED-271: Minimum Aviation System Performance Standard (MASPS) for Detect and Avoid [Traffic] for Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems in Airspace Classes A-C under IFR, 2022.

- Theunissen, E.; Corraro, G.; Corraro, F.; Ciniglio, U.; Filippone, E.; Peinecke, N. Differences between URClearED Remain Well Clear and DO-365. In Proceedings of the 2023 Integrated Communication, Navigation and Surveillance Conference (ICNS), 2023, pp. 1–10. [CrossRef]

- EUROCAE. ED-264: Minimum Aviation System Performance Standards (MASPS) for the Interoperability of Airborne Collision Avoidance Systems (CAS), 2020.

- RTCA. DO-382: Minimum Aviation System Performance Standards (MASPS) for the Interoperability of Airborne Collision Avoidance Systems (CAS), 2020.

- ASTM International. ASTM F3442/F3442M-23: Standard Specification for Detect and Avoid System Performance Requirements, 2023.

- RTCA. DO-396: Minimum Operational Performance Standards for Airborne Collision Avoidance System sXu (ACAS sXu), 2022.

- ICAO. Procedures for Air Navigation Services - Aircraft Operations, 2006.

- RTCA. DO-398: Operational Services and Evironment Definition (OSED) for Unmanned Aircraft Systems Detect and Avoid Systems (DAA), 2022.

- EUROCAE. ED-238: Operational Services and Environment Definition (OSED) for Traffic Awareness and Collision Avoidance (TAACAS) in Class A, B and C Airspace for Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS) operating under Instrument Flight Rules, 2017.

- EUROCAE. ED-258: Operational Services and Environment Description for Detect and Avoid [Traffic] in Class D-G Airspaces under VFR/IFR, 2019.

- EUROCAE. ED-313: Operational Services and Environment Description for Detect and Avoid [Traffic] in Class A-G Airspaces under IFR, 2023.

- EUROCAE. ED-267: Operational Services & Environment Definition for Detect & Avoid in Very Low-Level Operations, 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).