Submitted:

29 November 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Reference Aircraft

1.2. System High Level Requirements

1.2.1. Sense Requirements

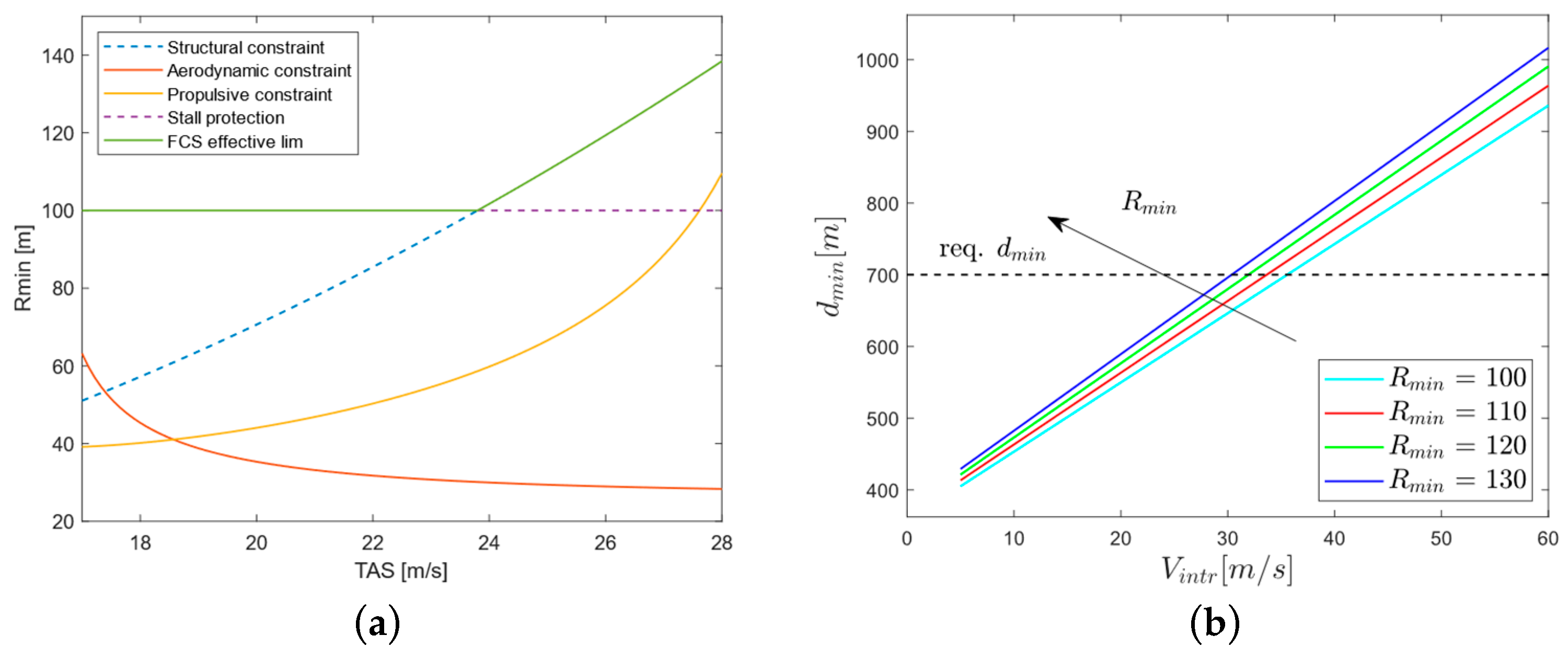

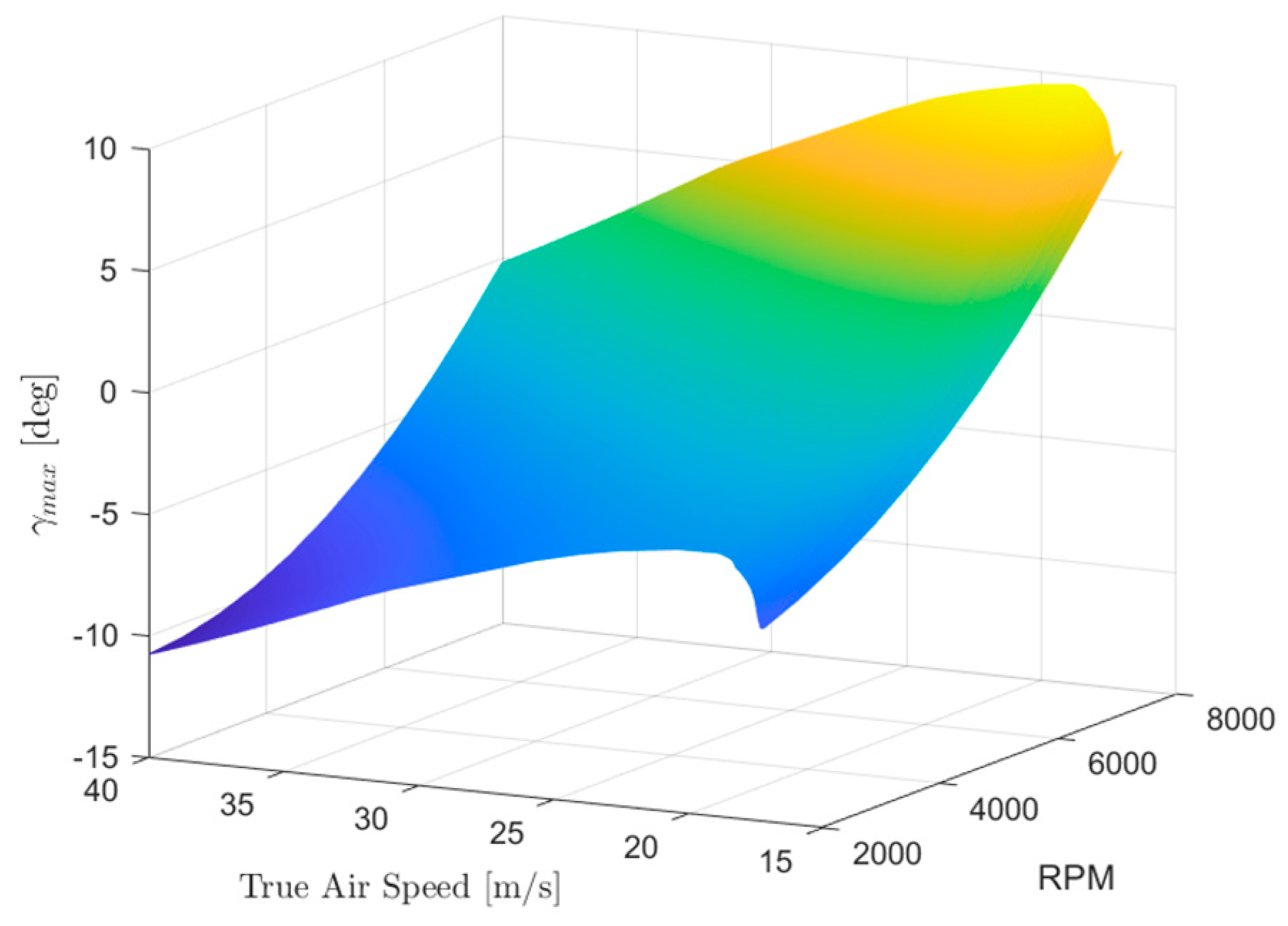

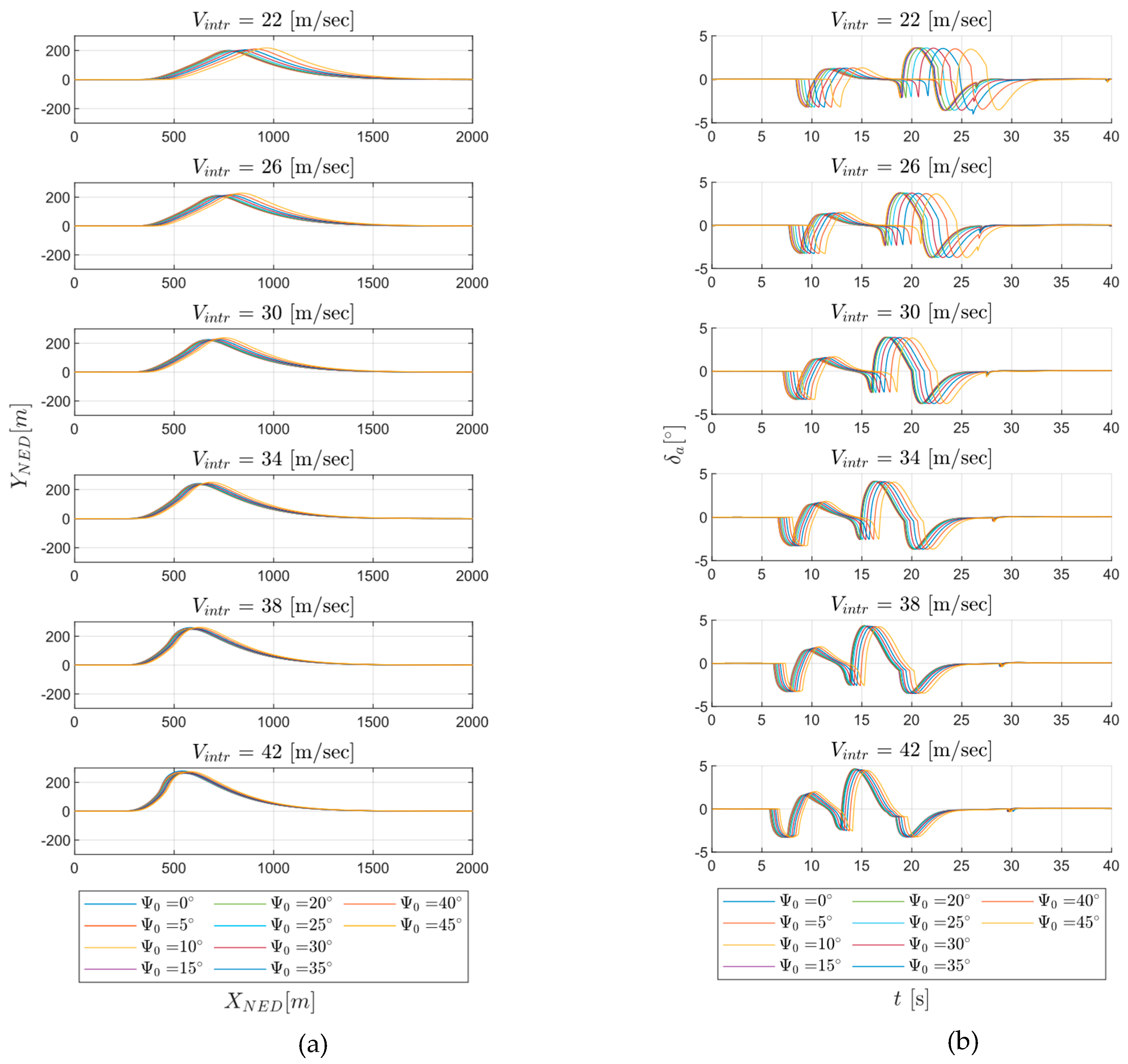

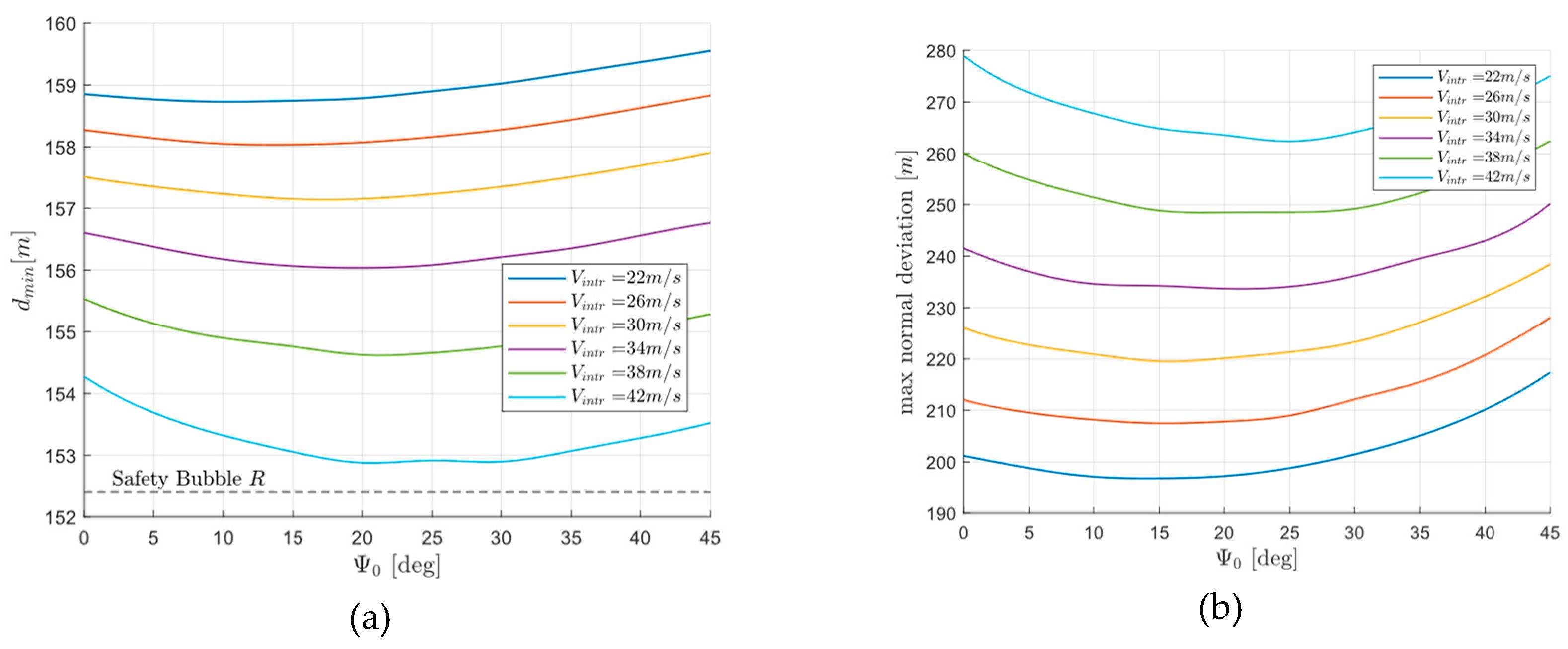

- Detection range, It is connected to the time-to-collision by means of approaching speed. It must be sufficiently large to allow for an avoidance manoeuvre complying with aircraft dynamic, structural and aerodynamical constraints that guarantees a minimum separation of 500 ft at the closest point of approach to the obstacle (“miss distance”) [23]. For the characterization of this requirement, the procedure described in [27] has been adopted by considering the most critical condition of a frontal encounter. Since the evasive manoeuvre will be conducted by means of a corrected turn on the horizontal plane, essentially depends on four factors: UAV speed, intruder aircraft speed, latency between detection and evasive command execution and especially the minimum turn radius. As well known, minimum turn radius (in stationary manoeuvre at constant altitude and speed) for a conventional fixed wing aircraft depends on three constraints: aerodynamic, structural and propulsive. As an example, Figure 2 (a) shows the minimum attainable turn radius at sea level for the TERSA aircraft according to each constraint where realistic bounds have been assumed for maximum lift coefficient , maximum vertical load factor , and available thurst (actual exact values provided by the manufacturer have been omitted due to NDA reasons). A lower threshold of is enforced by the FCS as a stall protection mechanism. As it can be noted, in the range of operative flight speeds (), structural constraint is the only effective bound but in turn is capped by the stall protection limit. Figure 2 (b) shows the required minimum detection range for various intruder speed and UAV minimum turn radius, according to the procedure described in [27] (conservative estimate with a delay factor of between detection and evasive command execution). A detection range of appears satisfactory for the effectiveness of a collision avoidance maneuver with an intruder flying at a comparable cruise speed as the UAV.

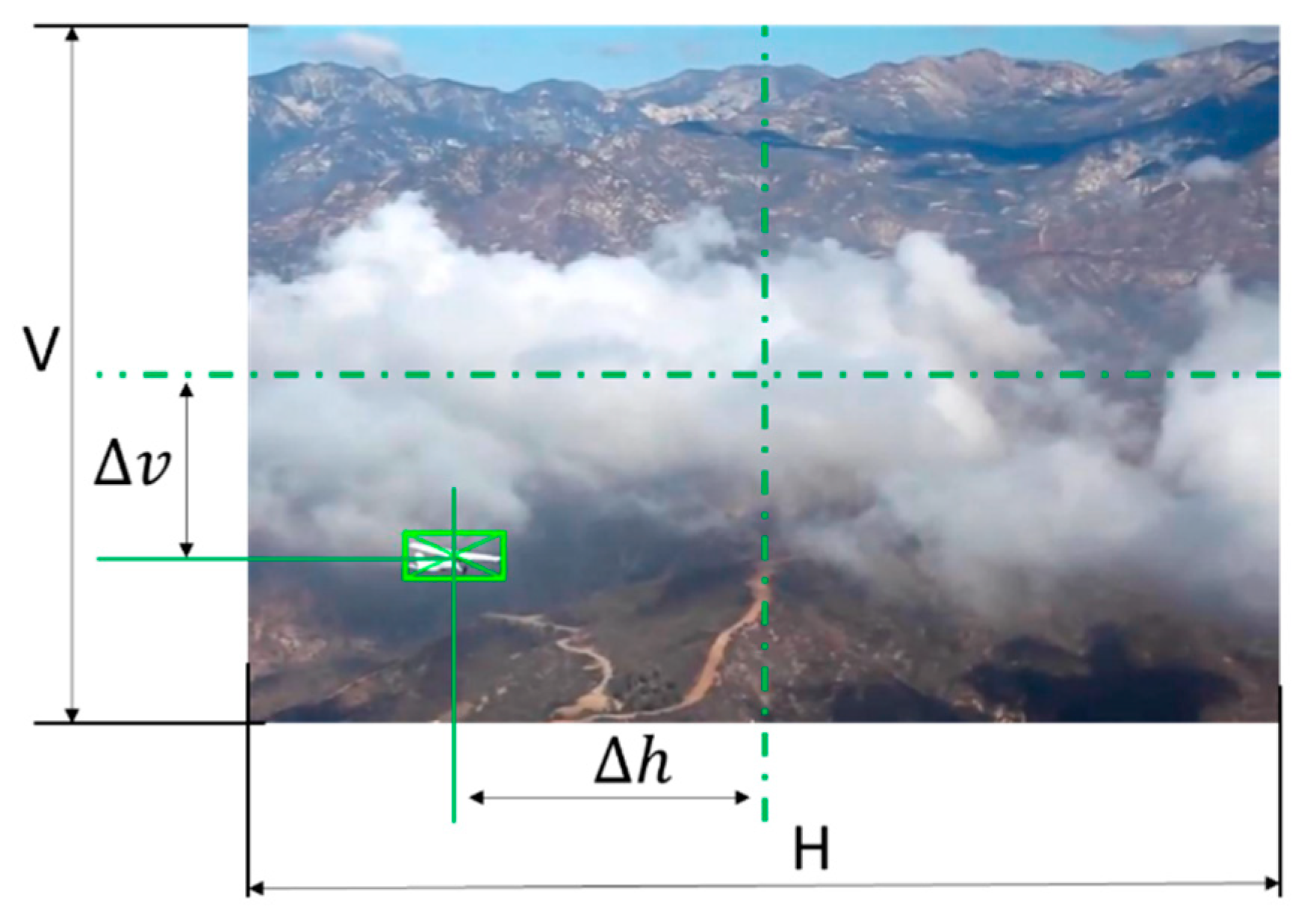

- Field of View: A widely accepted guideline for manned aircraft manufacturers is to build cockpits as to ensure a visibility of ±110° (azimuthal) and ±15° (in elevation) [23]. Usually, the same requirement is extended to Unmanned aircraft. However, due to the prototypical nature of this system a FOV of ±60° has been identified as the design requirement. As a matter of fact, preliminary sensitivity analysis conducted on a wide range of collision encounter scenarios, considering an intruder cruise speed comparable with the UAV cruise speed, have shown that, given an assigned detection range , FOV anlges greater than 55° don’t substantially affect the detectability of the intruder aircraft.

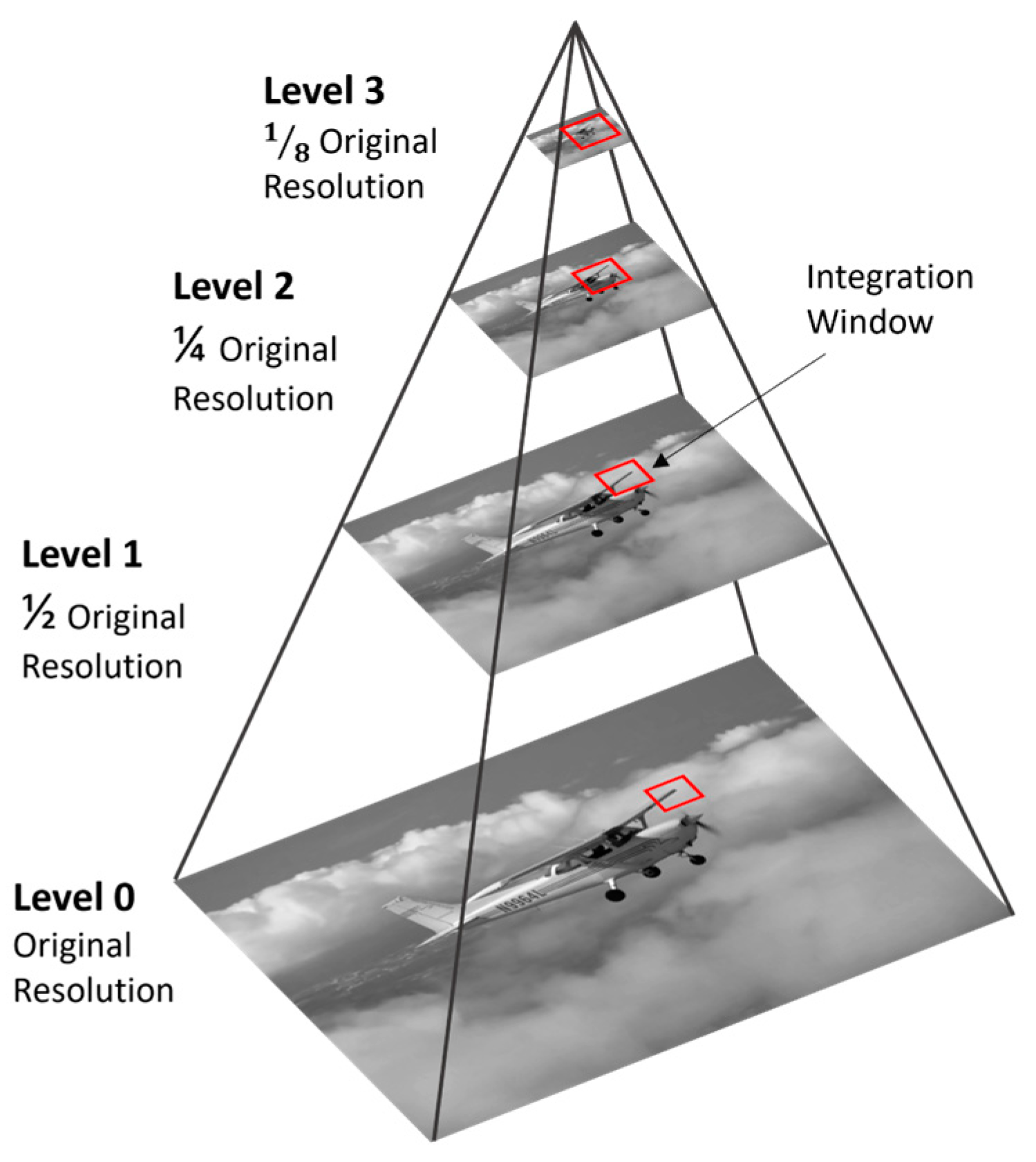

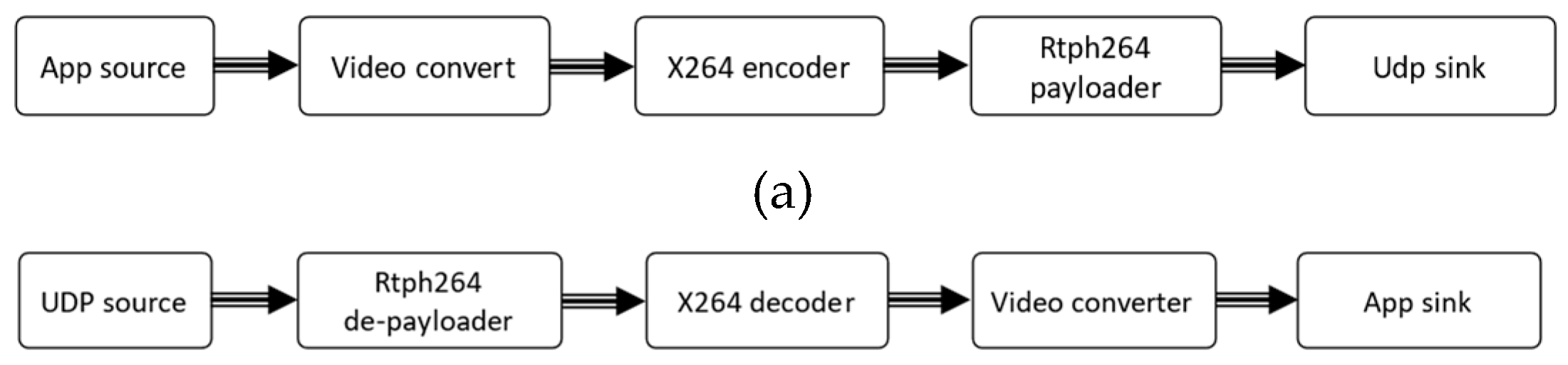

- Refresh rates: For a precise tracking of the intruder aircraft, computer vision algorithms should run at a sufficiently high frequency (> 10 FPS). Given the limited computational power available on board, it is thus essential to optimize object detection and tracking algorithms and to select the best compromise between image resolution and performance. Data fusion algorithms are based on a standard implementation of an extended Kalman filter and thanks to optimized linear algebra libraries do not pose a significant computation burden on the VPU processor. Likewise, collision avoidance routines, that exploit simple geometric laws, do not constitute a bottleneck for performance; the computation of the setpoint on the desired ground track angle to carry out the maneuver, essentially boils down to the extraction of the roots of a 4th order polynomial which again is performed effectively on the VPU processor by means of optimized linear algebra libraries (OpenBLAS/cuBLAS). The bottleneck is thus represented by the object detector pipeline.

- Optical sensor resolution: the choice of the optimal compromise is the result of a trade-off between computational efficiency and capability of detecting small targets at a great distance. The performance of the visual tracker chosen for the implementation of the system is essentially independent of the resolution because it acts on a finite set of discrete anchor points. On the contrary, the object detection pipeline is strongly affected by the size of the image as detailed in chapter 3. At the same time, a higher resolution is beneficial for two major reasons:

- The attainable maximum angular resolution can be expressed as:where is the horizontal pixel density of the sensor and the focal length.

- Johnson criteria states that the maximum distance at which an object of physical characteristic size of can be detected by an optical sensor, denoting with the minimum number of pixel the object needs to occupy for a successful detection (Johnson’s factor usually assumed = 2) and with the physical size of the pixel, is given by [27]:

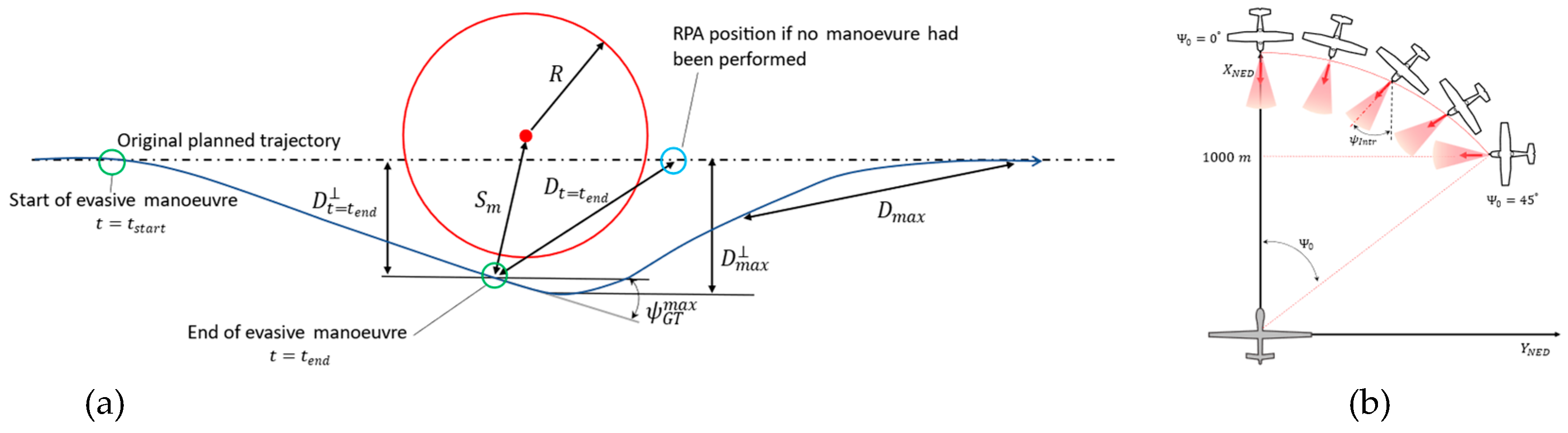

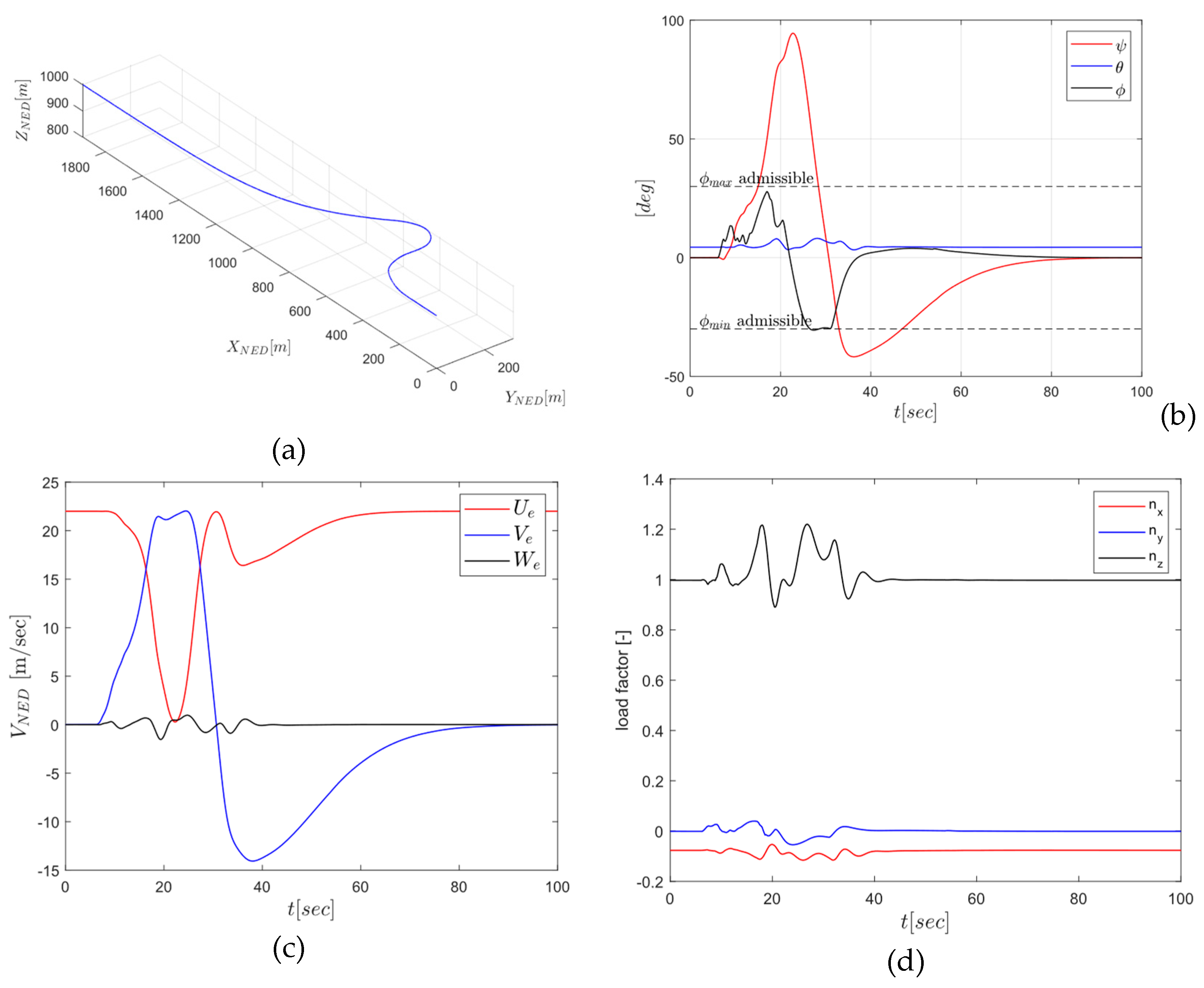

1.2.2. Avoid Requirements

- One single intruder aircraft present at a given time in the conflict scenario belonging to the same UAV class with comparable cruise speed and altitude.

- Such aircraft maintains its original linear stationary flight course, wing levelled, constant speed. Several combinations of relative initial positions and relative speeds are evaluated.

- Evasive maneuver is conducted by means of a correct turn on the horizontal plane, conducted at constant speed and altitude.

- Once a threat has been positively identified by the sense module, the avoid function has to perform an avoidance manoeuvre in a completely autonomous fashion which guarantees minimum separation provision at all times between the UAV and the intruder aircraft. The Autonomous Collision Avoidance (ACA) strategy employed must be effective for non-cooperative intruders.

- Such manoeuvre must be conducted on the horizontal plane by means of a coordinate turn that takes into account the aerodynamic and structural limits of the UAV.

- After the conflict has been deemed resolved by the Conflict Detection and Resolution (CDR) algorithms, the avoid module must bring the UAV on his original trajectory.

- It is desirable that the avoidance manoeuvre produces the minimum deviation from the original planned trajectory of the UAV.

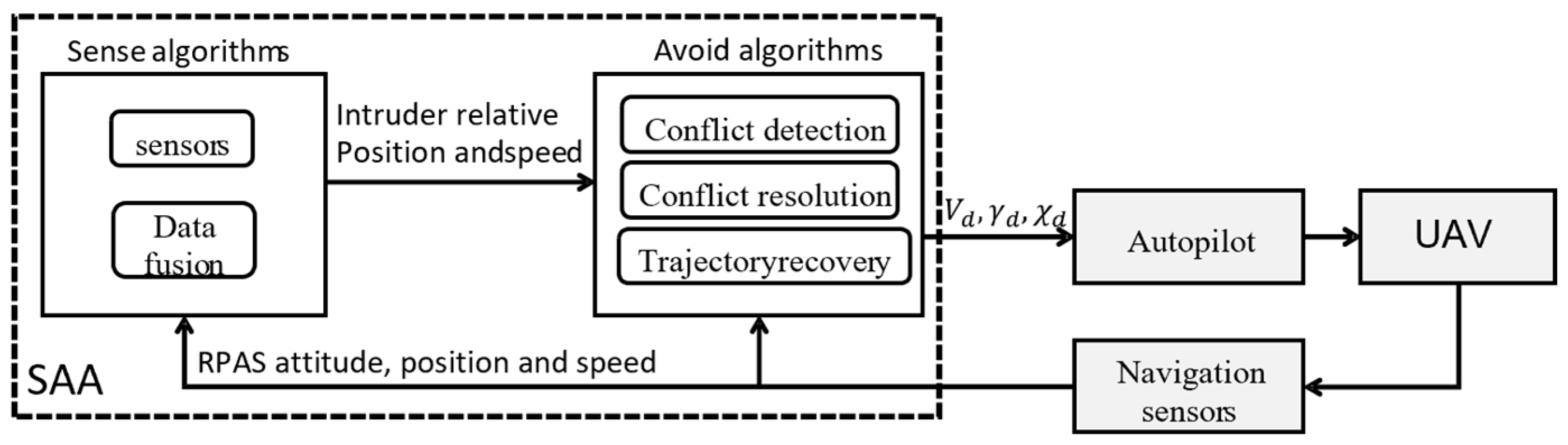

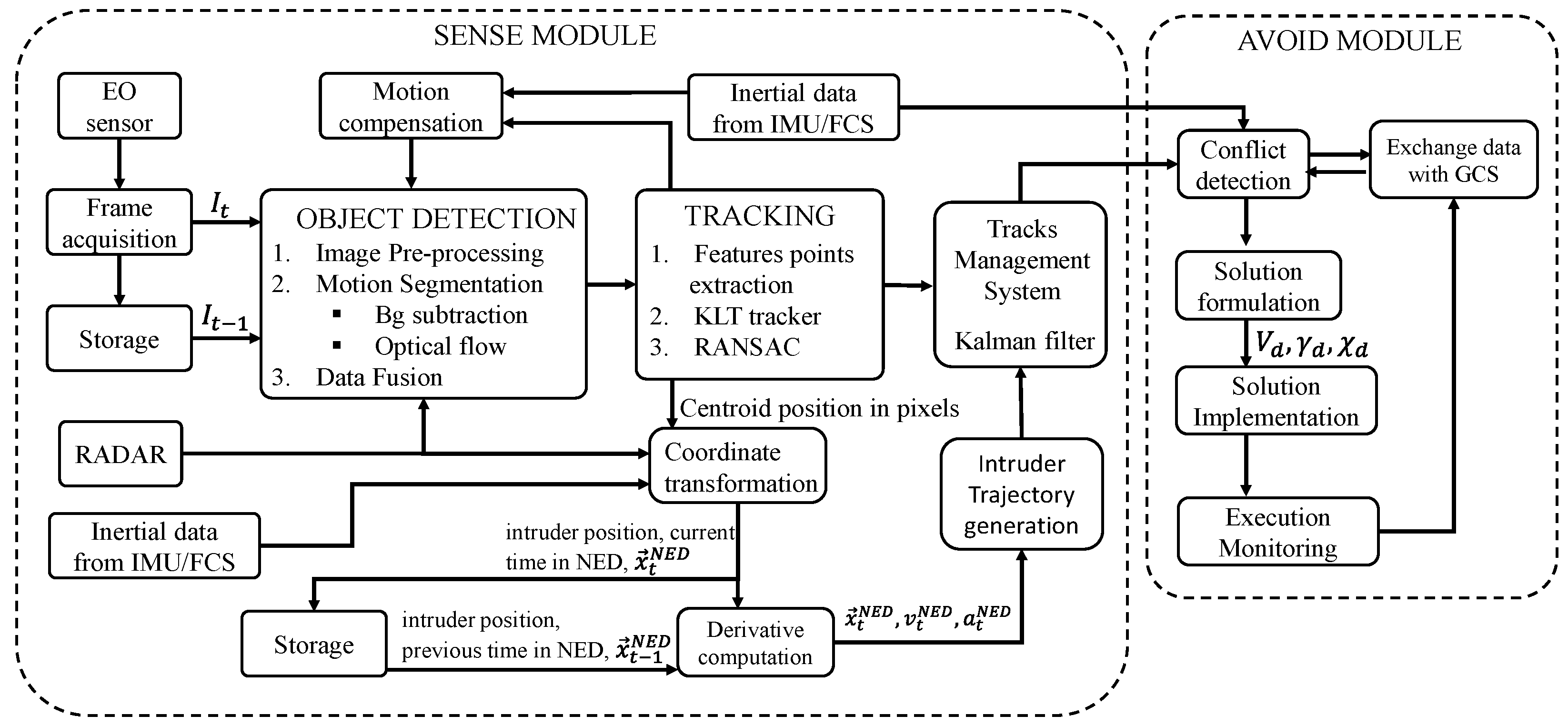

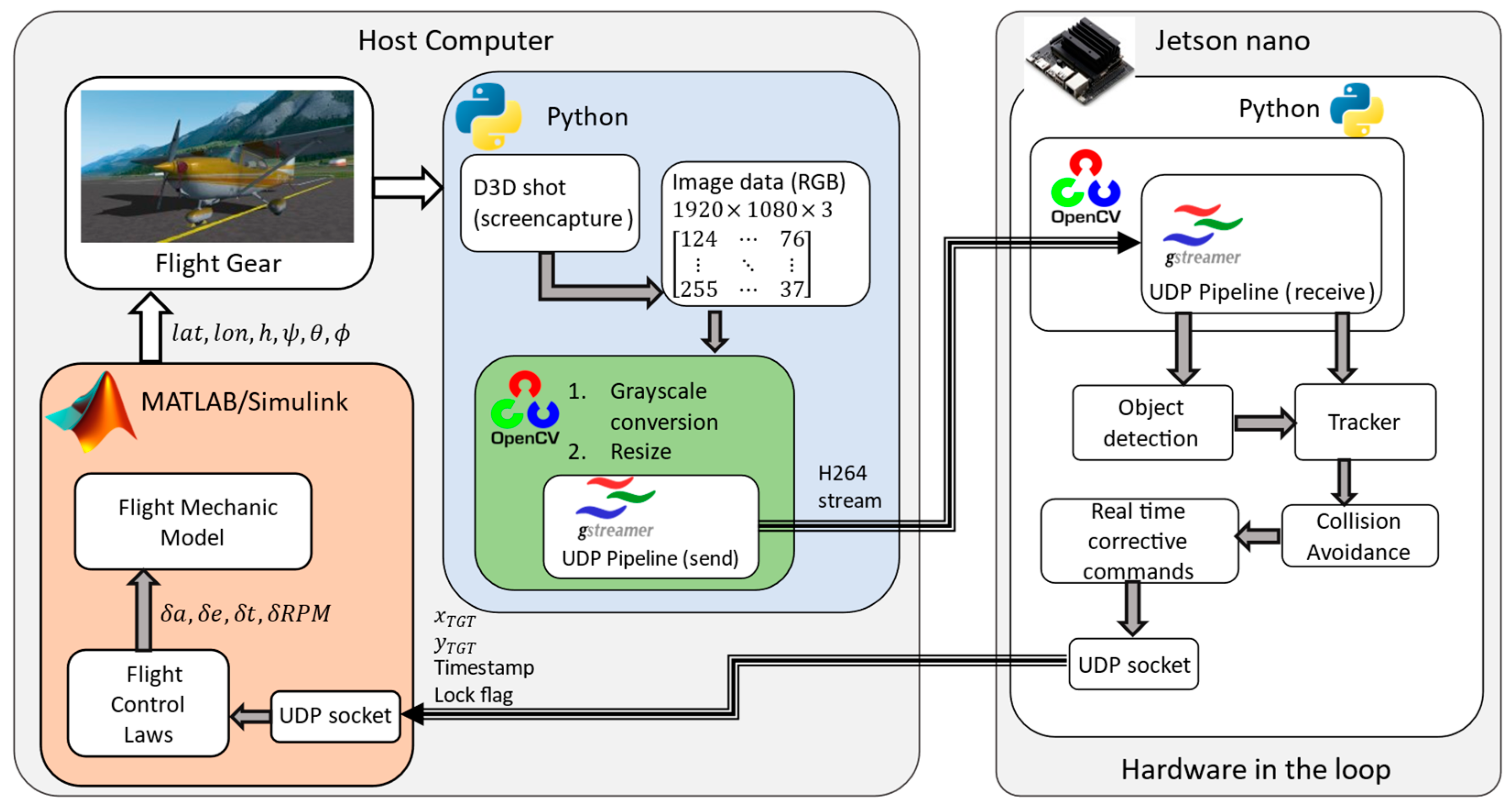

2. System Architecture

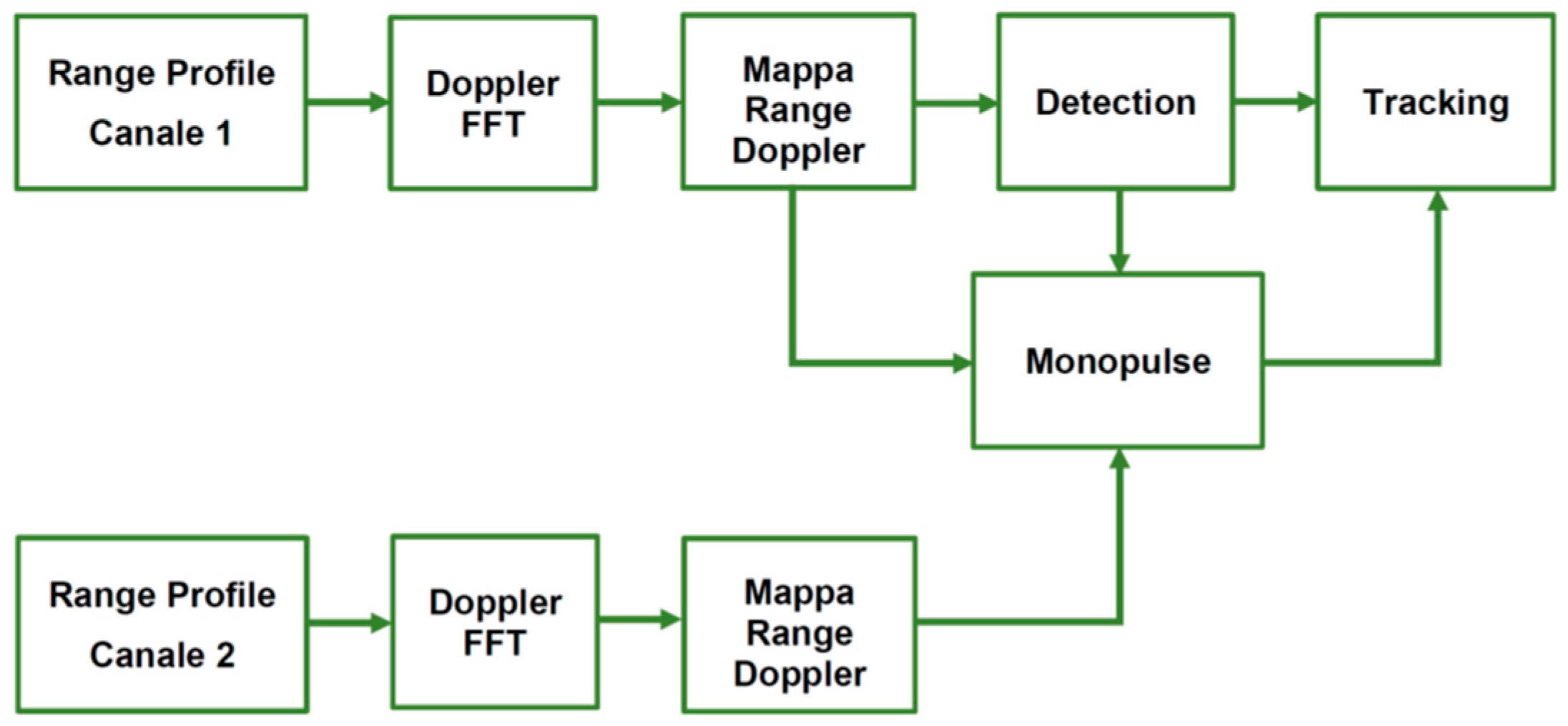

- A range doppler radar in Ku-band (13.325 GHz) with forward-looking configuration. Radar emits a Linear Frequency Modulated Continuous Wave (FMCW) with a maximum transmitted band of 150 MHz. Azimuth estimation is obtained by means of monopulse amplitude technique.

- Electro-optical sensor with at least 30 FPS, HD ready resolution. Focal length must be chosen to ensure a sufficiently high FOV.

- Vision processing Unit. An embedded platform with low power absorption, easily interfaceable with camera and radar (through ethernet) must be chosen, ideally optimized for computer vision tasks. Both Sense and avoid algorithms run on the embedded platform

- An Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) must be employed to retrieve attitude angles which are necessary to transform intruder aircraft position and velocity states into the inertial frame where the conflict is resolved.

3. Algorithms Design

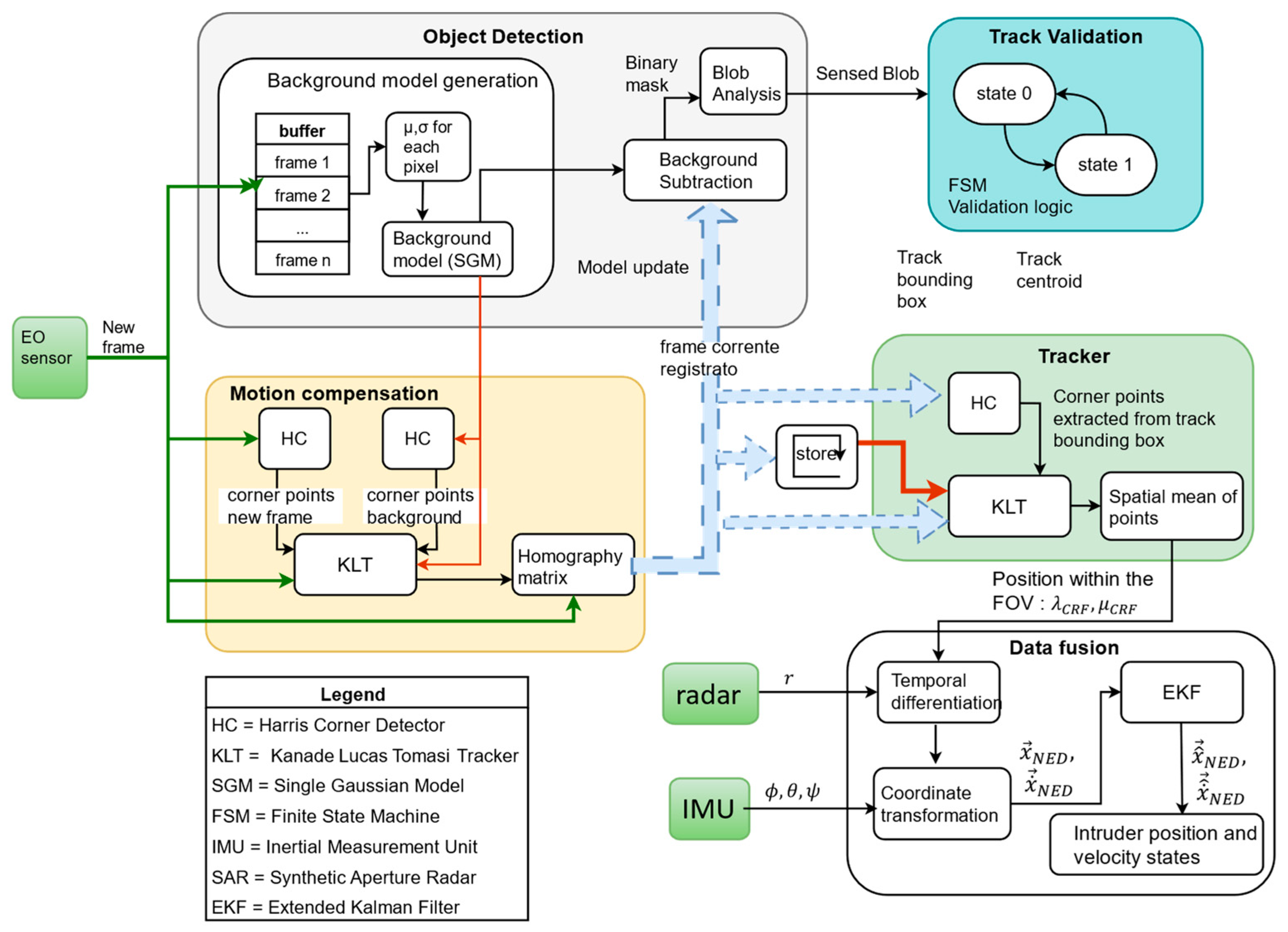

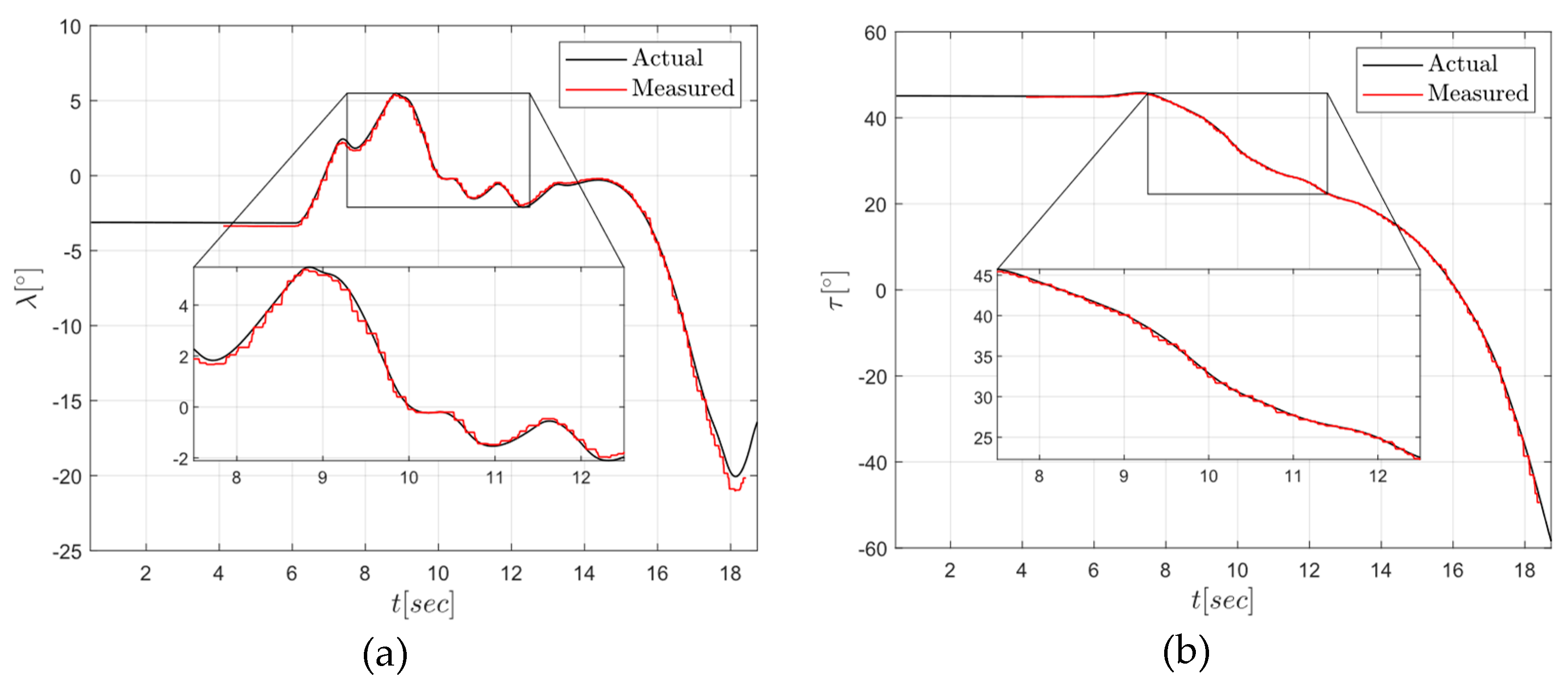

3.1. Sense Module

- 4.

- Segmentation between background and objects of interest within the FOV with the aim of identifying the presence of an intruder aircraft, Object Detection (OB).

- 5.

- Carry out noise suppression due to camera ego-motion, Ego Motion Compensation (EMO)

- 6.

- Once the presence of an object has been confirmed, track its motion efficiently across frames after its identification.

3.1.1. Harris Corner Detector

- Gray scale conversion of original image

- Spatial gradient calculation by means of linear spatial convolution with kernels and its transpose

- Structural tensor calculation for each pixel in a window centered around the pixel.

- Harris response calculation, by computing trace and determinant of M matrix.

- Non maxima suppression (to eliminate duplicate points) and thresholding: in a nutshell, only those points whose response is higher then 1% of the maximum R are selected as valid points.

- Biquadratic fitting to refine corner position and obtain a subpixel location.

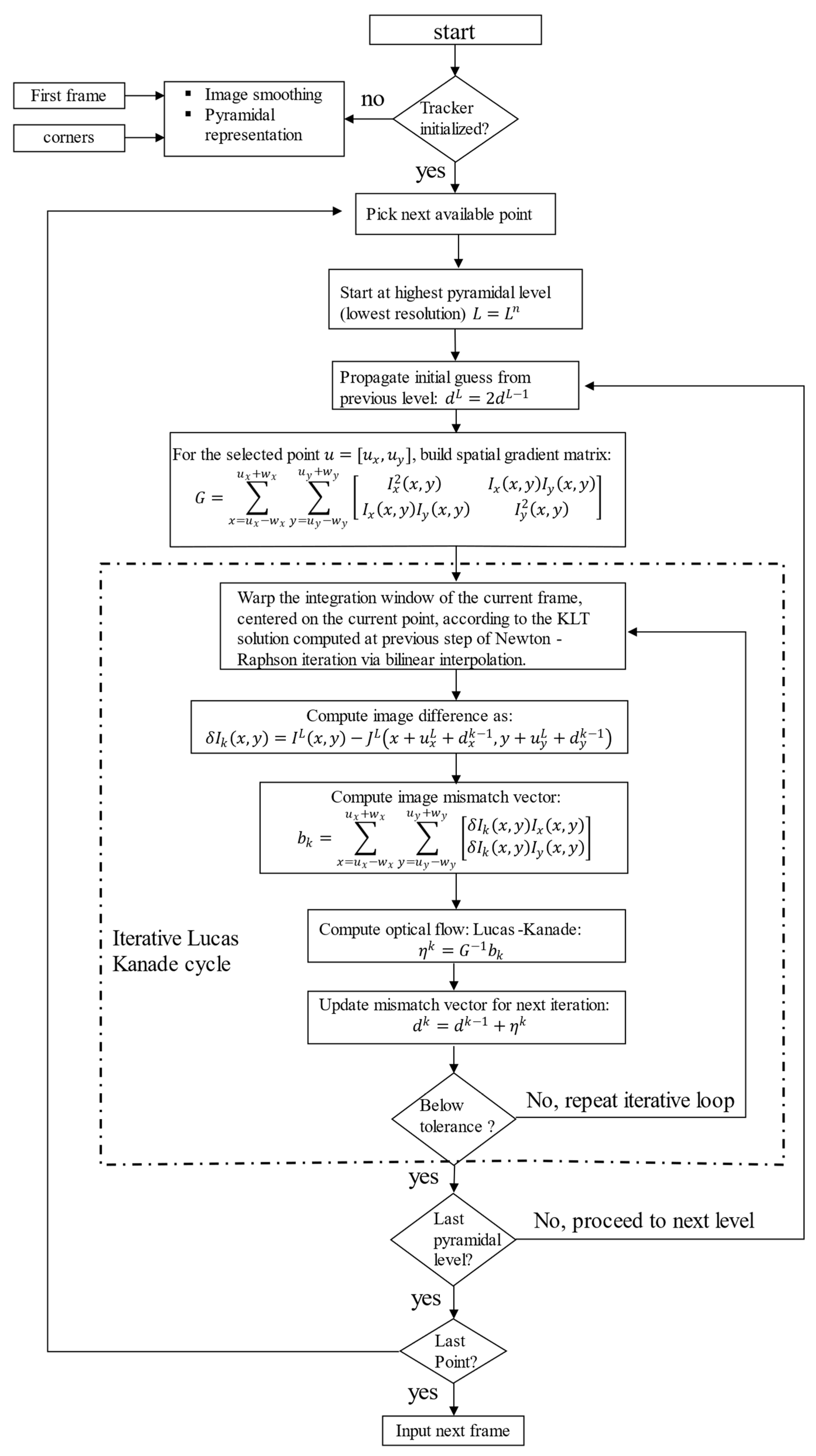

3.1.2. Kanade Lucas Tomasi Feature Tracker

3.1.3. Object Detection

- The construction of a panoramic background model by co-registering and stitching consecutive frames of the scene, the so-called panorama stitching.

- The update of a background model which preserves its size in terms of pixels. For this approach it is necessary to warp the background model on the current frame according to a matrix describing the transformation of the scene. The overlapping regions can then be updated while the new regions must be considered as background at the first iteration.

- Grayscale conversion of each new frame and preprocessing by spatial convolution with a Gaussian filter (low pass) to reduce aliasing effects and noise.

- A number of initial frames are stored in a buffer and used to build the single gaussian background model. Here denote pixel position while is the index of the single image in the buffer. In particular, mean intensity value and standard deviation are computed as:

- Once the background model is ready, at each iteration, once a new frame becomes available, the model is coregistered on the current frame following a procedure similar to the one detailed in [35]. The portion of the background which lies outside the new frame is discarded while the new portion of the scene which is not present in the model is flagged as background with maximum learning rate . This is done by computing the homography matrix which describes the perspective transformation between model and current frame using corner points as anchor points and applying this matrix on the background model (warping).

- For each pixel in the current frame, a corresponding pixel in the background model is computed as

- The comparison of the intensity value of a certain pixel in the current frame with the neighborhood of the corresponding pixel in the background model allows to determine whether or not said pixel belongs to the foreground. In analytical form this is expressed by Eq. (23)(24) and (25).where is a threshold chosen arbitrarily (design parameter).

- Once background and foreground section of the frame have been identified (segmentation process), the model is updated according to Eq. (26), (27)

- 7.

- Connected Component Analysis (CAA) is finally applied to condense several close blobs into the same track reading. In the chosen implementation, a connectivity analysis is essentially performed to filter out the various clusters of scattered pixels with little detection significance and due essentially to noise, in order to select only a trace with dimensions compatible with the intended purposes.

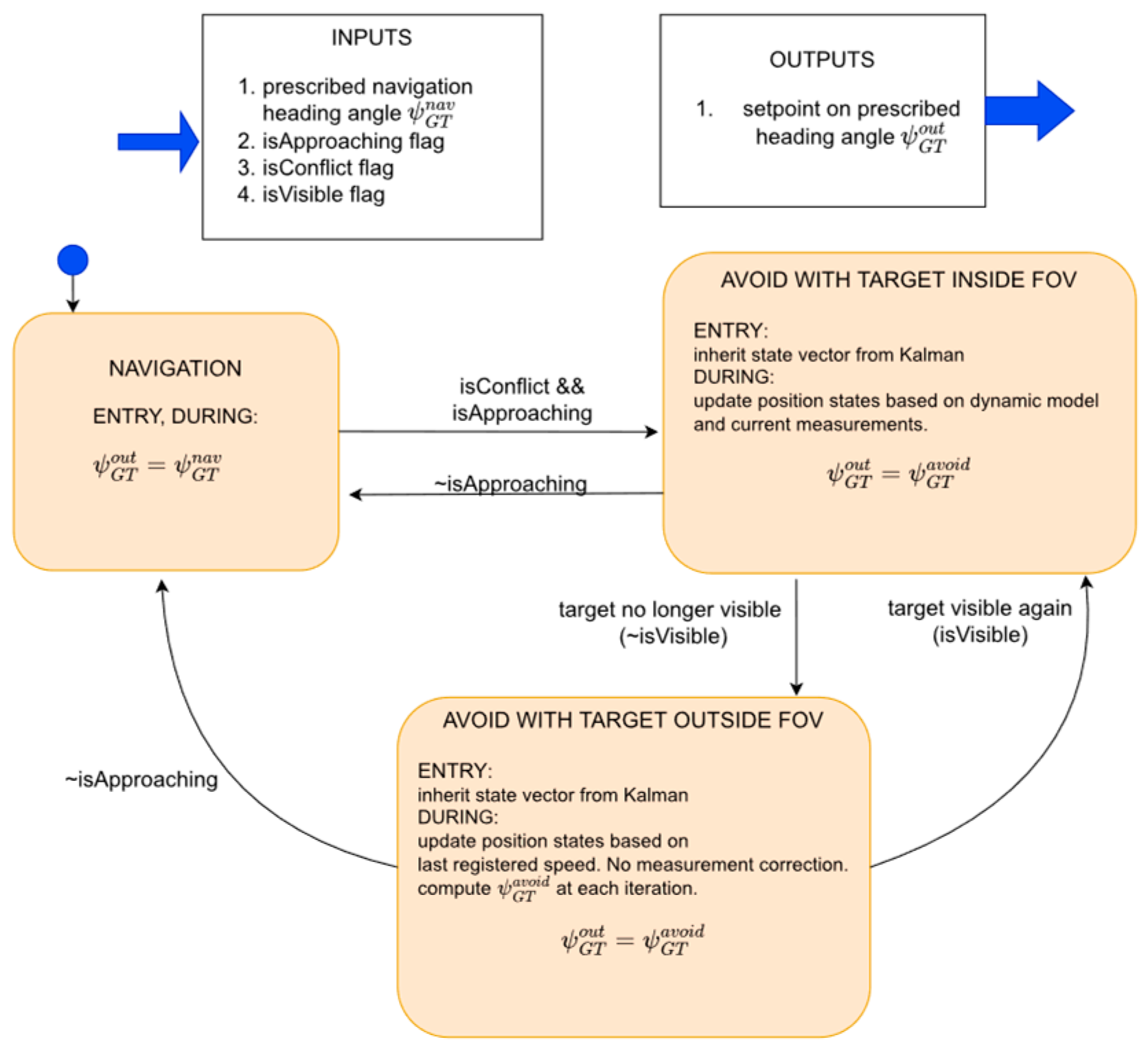

3.2. Avoid Module

- “Conflict detection problem”: at every processing step, the feasibility of a potential conflict in the future is investigated by determining whether or not, loss of minimum separation will occur at a future time. In other words, it is determined whether the UAV will cross the safety bubble centred around the intruder aircraft. If the response is affirmative the next problem is solved.

- “Conflict resolution problem”: based on the concept of collision cone, during conflict resolution stage, the system computes a heading setpoint that will bring the trajectory of the UAV to be tangent to the safety bubble around the intruder aircraft.

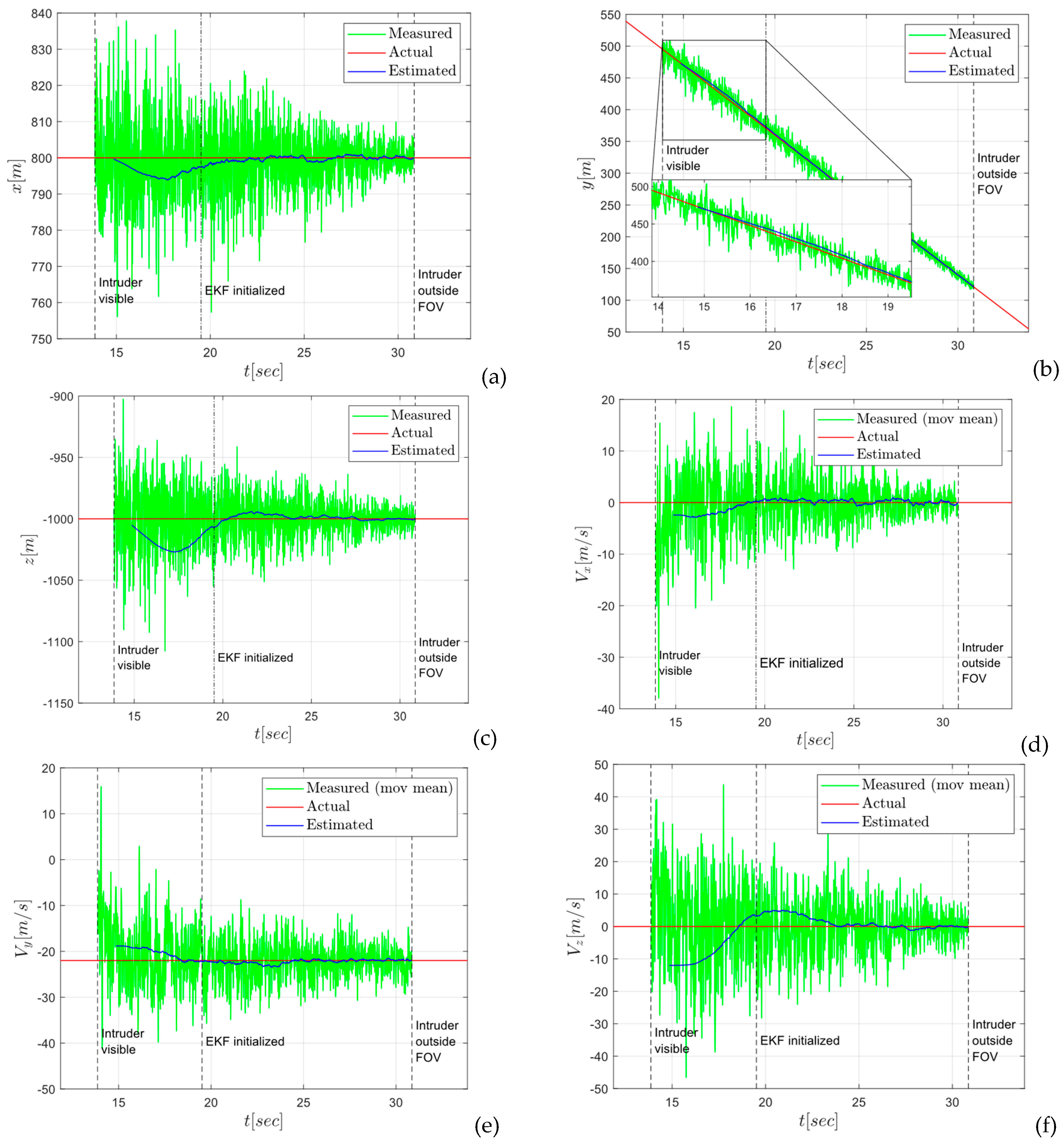

3.3. Data Fusion

3.4. Radar Algorithms

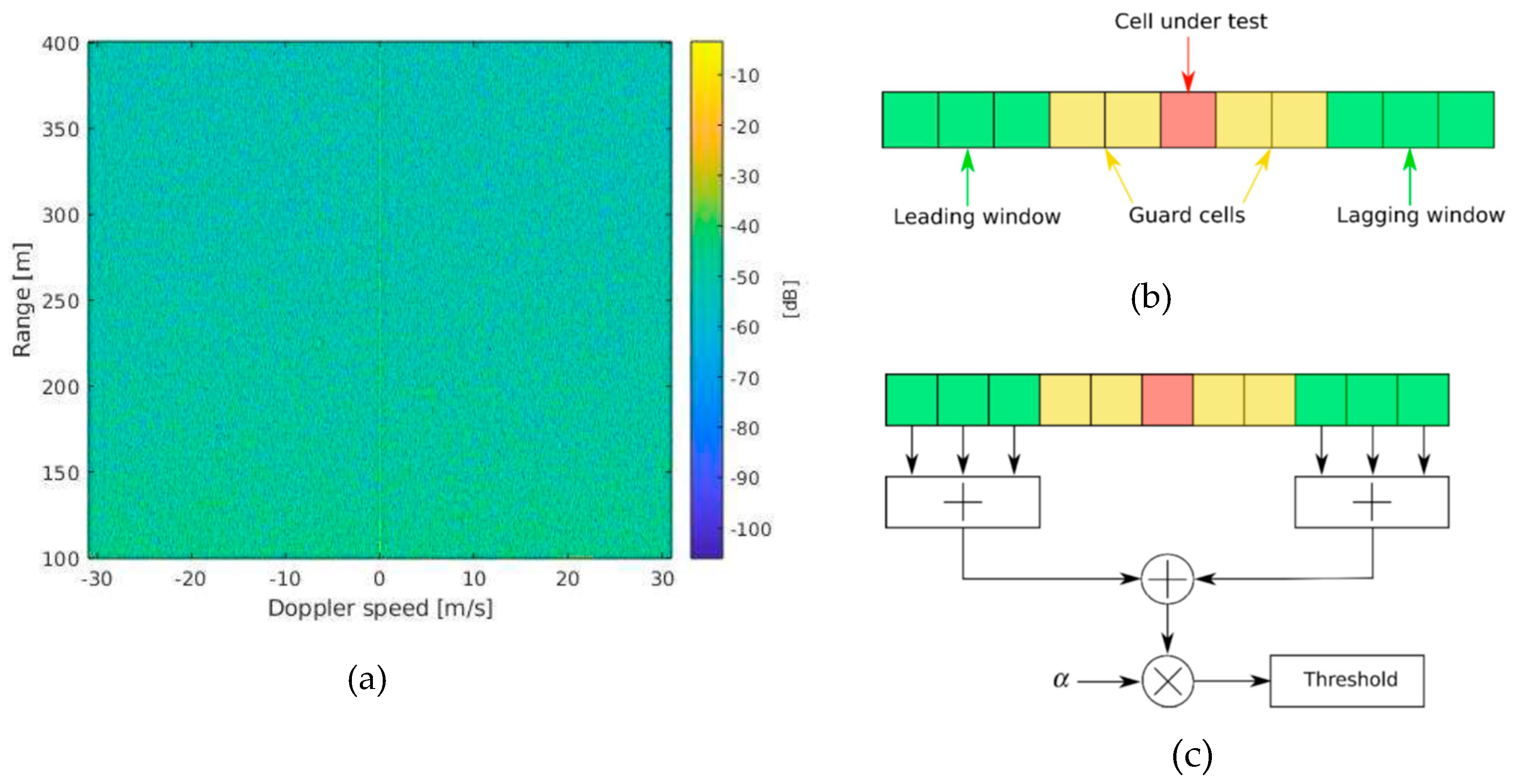

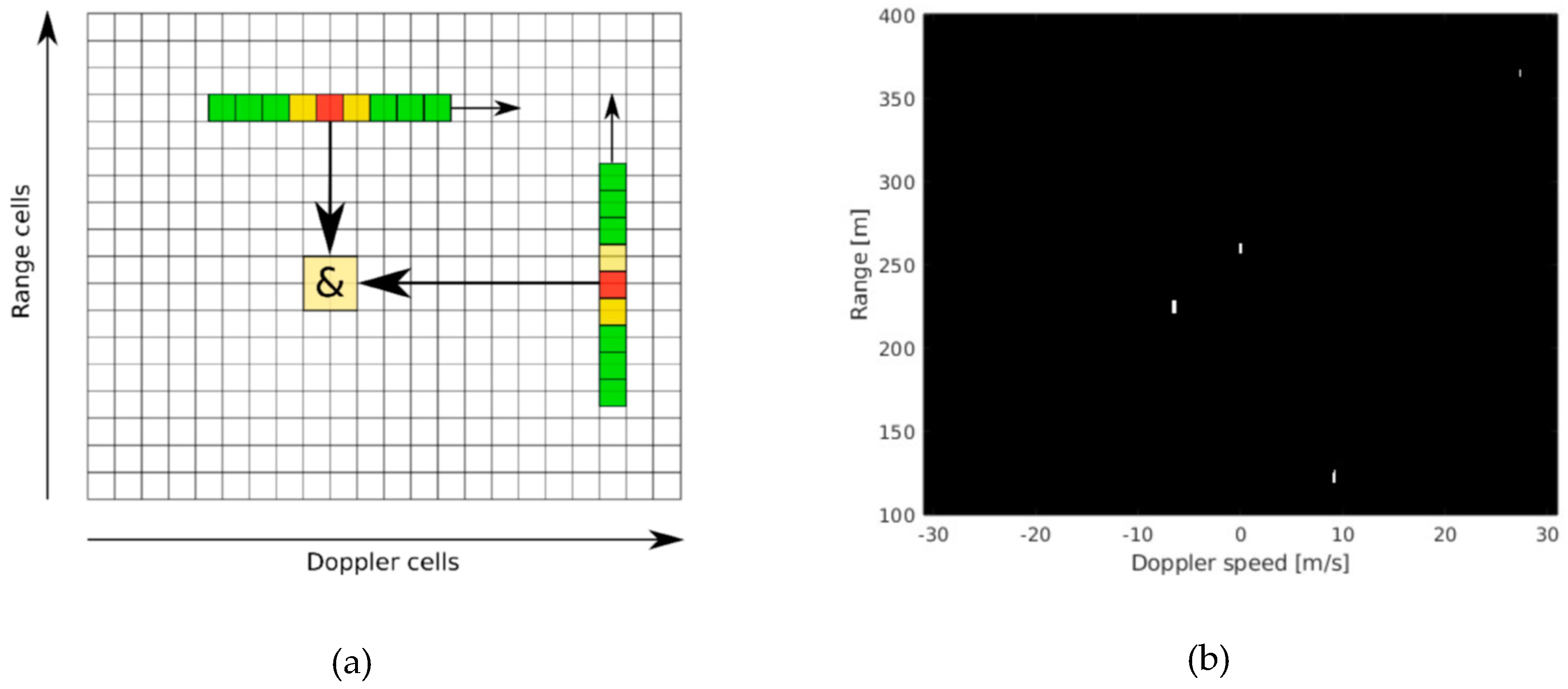

3.4.1. Detection

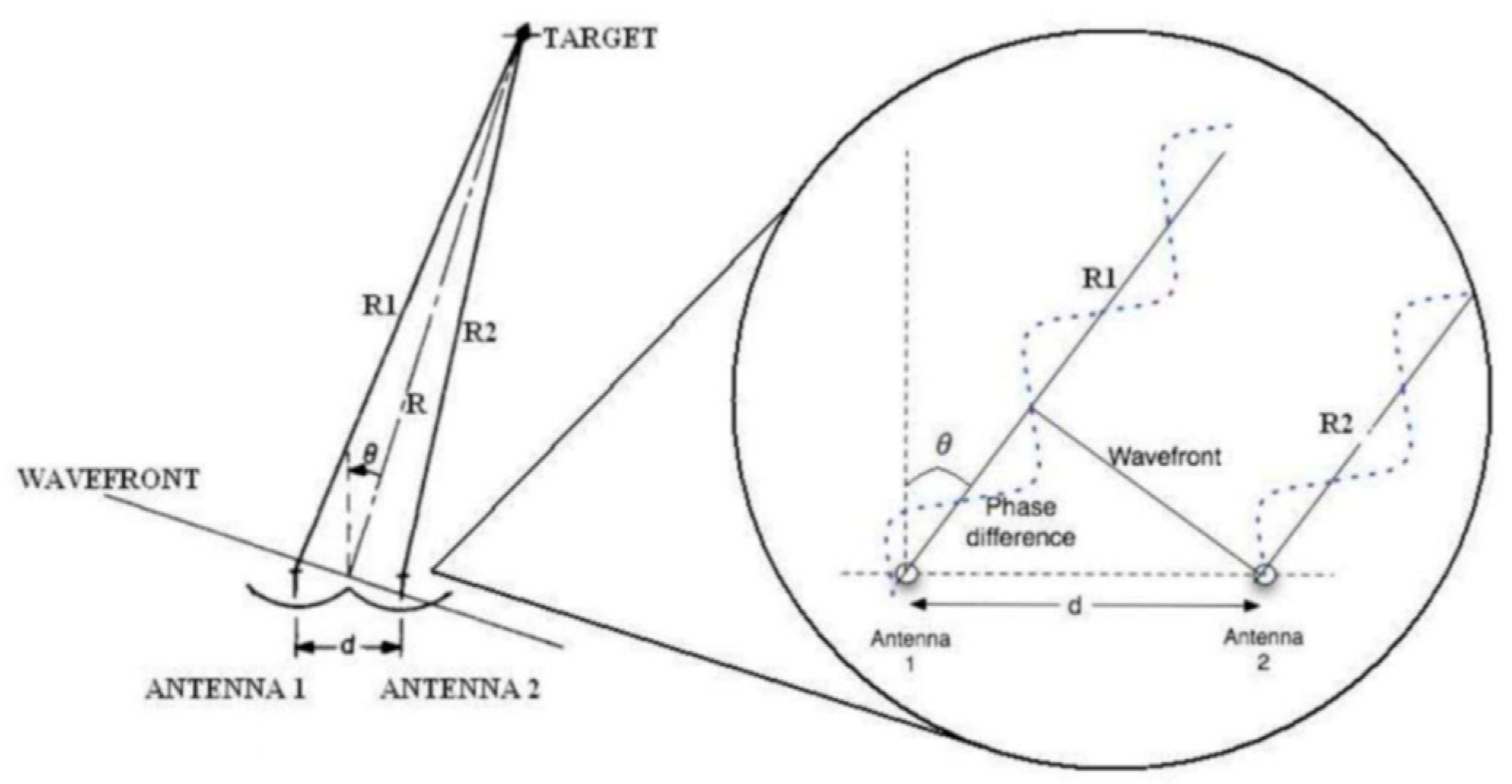

3.4.2. Monopulse

4. Simulation Campaign

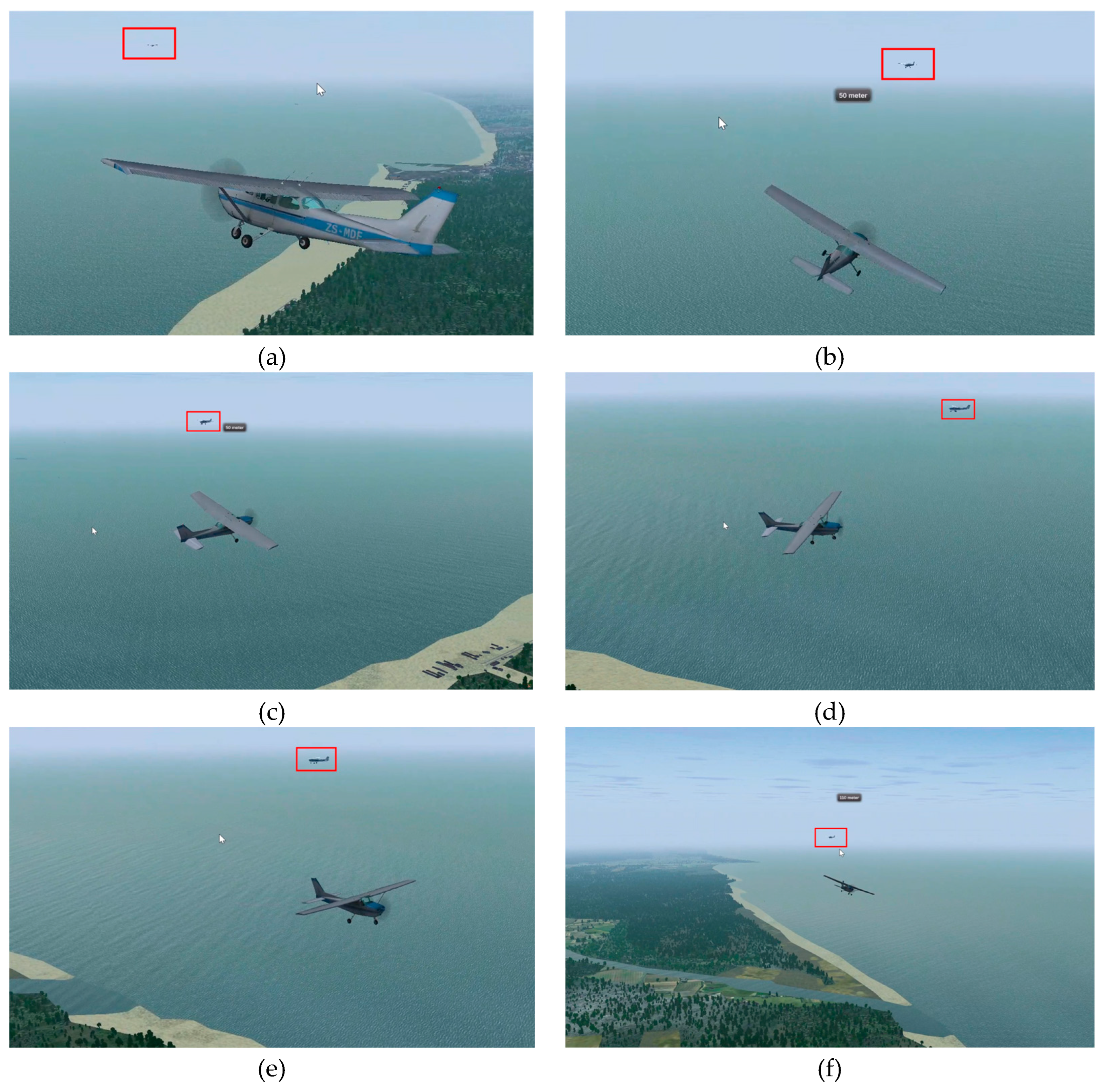

5. Flight Tests

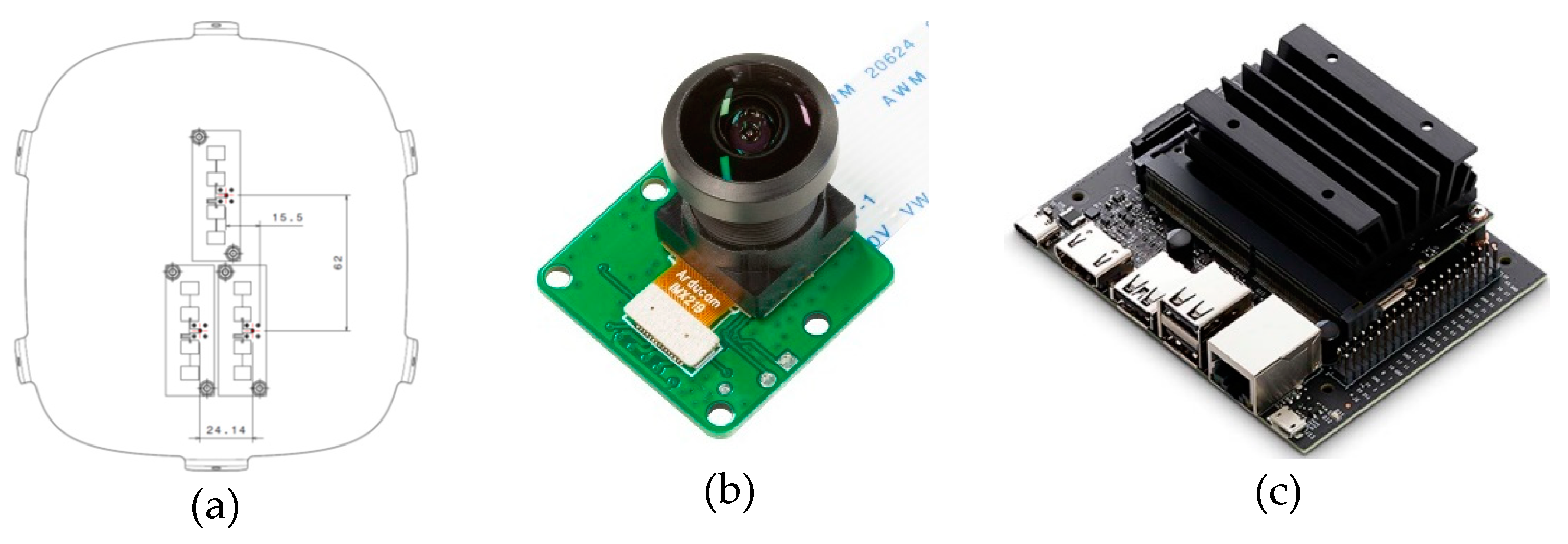

- Color camera Arducam 1/4” 8MP IMX219, 30 FPS. Recording resolution was set at 1280 x 720. Due to the small footprint size of the target in terms of pixels it was chosen a lens with a horizontal FOV of around .

- Sense and Avoid doppler radar, developed by Echoes.

- Vision Processing Unit. Nvidia Jetson Nano was chosen thanks to its small size and weight and low power absorption.

- Receiving and transmitting antennas are housed inside a fiberglass mockup of the nose of the aircraft to better simulate operating conditions of the system. Fig shows the position of the antennas within the nose. Camera sensor was mounted on the nose mockup in such a way to ensure the alignment of the camera Line of Sight with radar beam.

- Lipo batteries provide power to the radar at a tension of 22V, while a voltage regulator is employed to provide power to VPU and camera at a lower voltage.

- Two different workstations were used for real time monitoring of both radar and camera sensors.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAA “Integration of Civil Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) in the National Airspace System (NAS) Roadmap - 2° Ed,” Federal Aviation Administration, 2018.

- R. Merkert and J. Bushell, “Managing the drone revolution: A Systematic literature review into the current use of airborne drones and future strategic directions for their effective control,” Journal of Air transport Management, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Angelov, Sense and Avoid in UAS (Research and Applications), John Wiley & Sons, Ltd ISBN: 978-0-470-97975-4, 2012.

- K. V. a. L. P. K. Dalamagkidis, “On unmanned aircraft systems issues, challeneges and operational restrictions preventing integration into the National Airspace System,” Progress in Aerospace Sciences, vol. 44, no. 7, pp. 503-519, 2008. [CrossRef]

- ENAC, “Regolamento mezzi aerei a pilotaggio remoto,” 2016.

- G. Recchia, G. Fasano, D. Accardo and A. Moccia, “An Optical Flow Based electro-Optical See-and-Avoid System for UAVs,” IEEE, 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. martin, J. Riseley and J. J. Ford, “A Dataset of Stationary, Fixed-wing Aircraft on a Collision Course for Vision-Based Sense and Avoid,” in International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Dubrovnik, Croatia, 2022. [CrossRef]

- FAA, “Sense and Avoid (SAA) for unmanned aircraft systems (UAS). Prepared by FAA sponsored Sense and Avoid Workshop,” Oct. 9, 2009.

- Radio Technical Commision for Aeronautics, “RTCA-DO-185B, Minimum operational performance standards for traffic alert and collision avoidance system II (TCAS II),” July 2009.

- D. Klarer, A. Domann, M. Zekel, T. Schuster, H. Mayer and J. Henning, “Sense and Avoid Radar Flight Tests,” in International Radar Symposium, Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Mohammadkarimi and R. T. Rajan, “Cooperative Sense and Avoid for UAVs using Secondary Radar,” IEEE transactions on aerospace and electronic systems, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Huizing, M. Heiligers, B. Dekker, J. d. Wit and L. Cifola, “Deep Learning for Classification of Mini-UAVs Using Micro-Doppler Spectrograms in Cognitive Radar,” IEEE Aerospace and Electronic Systems Magazine, vol. 34, no. 11, pp. 46-56, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. L. a. Y. S. “. a. t. o. a. U. v. C. Zhou, “Detection and tracking of a UAV via hough transform,” in CIE International Conference on Radar, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Ramasamy, R. Sabatini, A. Gardi and J. Liu, “LIDAR Obstacle Warning and Avoidance System for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Sense-and-Avoid,” Aerospace Science and Technology, 2016. [CrossRef]

- v. Karampinis, A. Arsenos, O. Filippopoulos, E. Petrongonas, C. Skliros, D. Kollias, S. Kollias and A. Voulodimos, “Ensuring UAV Safety: A Vision-only and Real-time Framework for Collision Avoidance Through Detection, Tracking and Distance Estimation.,” in International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Chania, Crete, Greece, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Opromolla, G. Inchingolo and G. Fasano, “Airborne Visual Detection and Tracking of Cooperative UAVs Exploiting Deep Learning,” MDPI Sensors, vol. 19, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhao, J. Zhang, D. Li and D. Wang, “Vision-based Anti-UAV Detection and Tracking,” IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Bauer, A. HIba and J. Bokor, “Monocular Image-based Intruder Direction Estimation at Closest Point of Approach,” in International COnference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Miami, FL, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Vitiello, F. Causa, R. Opromolla and G. Fasano, “Experimental Analysis of Radar/Optical Track-to-track Fusion for Non-Cooperative Sense and Avoid,” in International COnference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), Warsaw, Poland, 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Fasano, D. Accardo, A. E. Tirri and A. Moccia, “Radar/electro-optical data fusion for non-cooperative UAS sense and avoid,” Aerospace Science and Technology, vol. 46, pp. 436-450, 2015. [CrossRef]

- ICAO, “Doc 10019 - Manual on Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems,” International Civil Aviation Organization, 2015.

- ICAO, “Cir. 328 - Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS),” International Civil Aviation Organization, 2011, 2011.

- ASTM Designation: F 2411-04, “Standard Specification for Design and Performance of an Airborne Sense-and-Avoid system,” ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2004.

- EUROCONTROL, “Specification for the use of Military Unmanned Aerial Vehicle as Operational Traffic Outside Segregated Airspaces, SPEC-0102,” July 2007.

- A. D. Zeitlin, “Progress on Requirements and Standards for Sense & Avoid,” The MITRE Corporation, 2010.

- C. Geyer, S. Singh and L. Chamberlain, “Avoiding Collisions Between Aircraft: State of the Art and Requirements for UAVs operating in Civilian Airspace.,” 2008.

- G. Fasano, D. Accado, A. Moccia and D. Moroney, “Sense and Avoid for Unmanned Aircraft Systems,” IEEE A&E SYSTEMS MAGAZINE, pp. 82-110, November 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Ramasmy and R. Sabatini, “A Unified Approach to Cooperative and Non-Cooperative Sense-and-Avoid,” in International Conference on Intelligent robots and Systems (IROS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. D. Lucas and T. Kanade, “An Iterative Image Registration Technique with an Application to Stereo Vision,” in Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, Canada, 1981.

- C. Harris and M. Stephens, “A Combined Corner And Edge Detection,” in Proceedings of the 4th Alvey Vision Conference, 1988. [CrossRef]

- J. Y. Bouguet, “Pyramidal Implementation of the Lucas Kanade Feature tracker Description of the algorithm,” Intel Corporation, Microprocessor Research Labs, 2000.

- L. Forlenza, G. Fasano and A. M. D. Accardo, “Flight Performance Analysis of an Image Processing Algorithm for Integrated Sense-and-Avoid Systems,” International Journal of Aerospace Engineering, p. 8, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Y. Benezeth, P. M. Jodoin, B. Emile, H. Laurent and C. Rosenberger, “Comparative Study of Background Subtraction Algorithm,” Journal of Electronic Imaging, July 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. Redmon, S. Divvala, R. Girshick and A. Farhadi, “You Only Look Once: Unified Real-Time Object Detection,” 9 May 2016. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1506.02640v5.

- S. W. Kim, K. Yun, K. M. Yi, S. J. Kim and J. Y. Choi, “Detection of moving objects with moving camera using non-panoramic background model,” machine Vision and Applications, pp. 1016-1028, 2013. [CrossRef]

- W. Y. D. H.,. J. K. L. Kurnianggoro, “Online Backgorund-Subtraction with Motion Compensation for Freely Moving Camera.,” in Intelligent Computing Theories and Application, 2016. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Yi, K. Yun, S. W. Kim, H. J. Chang, H. Jeong and J. Y. Choi, “Detection of Moving Objects with Non-stationary Cameras in 5.8ms: Bringing Motion Detection to Your Mobile Device,” in IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, 2013. [CrossRef]

- C. Carbone, U. Ciniglio, F. Corraro and S. Luongo, “A Novel 3D Geometric Algorithm for Aircraft Autonomous Collision Avoidance,” in Proceedings of the 45th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, San Diego, CA, USA, 2006. [CrossRef]

- A. Chakravarthy and D. Ghose, “Obstacle avoidance in a Dynamic Environment: A Collision Cone Approach,” IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics - Part A: Systems and Humans, vol. 28, no. 5, 1998. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang, A. Then and R. Herschel, “UAV Tracking based on Unscented Kalman FIlter for Sense and Avoid Applications,” in International Radar Symposium, Warsaw, Polan, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Huang, H. Zhou, M. Zheng, C. Xu, X. Zhang and W. Xiong, “Cooperative Collision Avoidance Method for Multi-UAV Based on Kalman Filter and Model Predictive Control,” in International Conference on Unmanned Systems and Artificial Intelligence (ICUSAI), Xi'an, China, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Fiorio, R. Galatolo and G. D. Rito, “Extended Kalman Filter Based Data Fusion Algorithm Implemented in a Sense and Avoid System for a Mini-UAV application,” in IEEE Metrology for Aerospace, Lublin, Poland, 2024. [CrossRef]

| MTOW | |

| Reference surface S | |

| Mean aerodynamic chord | |

| Wingspan | |

| Stability margin |

| UAV Telemetry | Radar | Camera |

|---|---|---|

| Altitude | Target radial distance | Target position within FOV |

| Latitude | Target radial velocity | Timestamp of readings |

| Longitude | System attitude (roll, pitch, heading) | |

| Timestamp of readings | System position (altitude, latitude, longitude) | |

| Timestamp of readings |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).