1. Introduction

UAS are currently conquering the skies due to their autonomus capabilities, high mobility, and fast and flexible deployment. Typically a the more general term of UAS consists of the unmanned aircraft namely Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV), a Data Link, and the Remote Pilot Station (RPS) [

1]. With the emergence of new technological advancements in communication and sensor technologies these systems have gained the potential to catalyse equivalent fundamental change in our mobility infrastructure. Particularly BVLOS operations are playing a pivotal role in unlocking the full potential of unmanned systems due to their extended intelligence and autonomy. BVLOS refers to the capability of an unmanned vehicle, to operate where humans cannot reach, following a predefined route, while any onboard information is obtained by advanced sensing instrumentation, such as on-board cameras, and detect and avoid technologies. In such a highly automated operation framework, the aircraft is able to conduct its own mission, make its own decisions during the mission and react to unforeseen events without the pilot’s intervention [

2].

1.1. Opportunities and challenges

BVLOS operations offer new means of delivering value-added services through a wide range of applications, ranging from remote sensing for object detection and tracking [

3], search and rescue operations, disaster and crisis management [

4], precision agriculture [

5], or environmental monitoring [

6] to logistics and industrial applications such as freight transportation [

7], or delivery of medical supplies [

8]. This ‘plateau of productivity’ holds particular promise but demands new technical and regulatory capabilities to support drone operations in long range as well as UAS operation in the future high volumes of air traffic.

Highly reliable and precise multi-technology communication systems, fail-operational hardware and fault tolerant software are all essential requirements for the further enhancement of highly reliable and autonomous BVLOS flights for everyday tasks, like delivery of goods. These systems must ensure accurate and safe navigation as well as dependable control links, all while maintaining a cost level that aligns with acceptable expenses for mass-market product delivery. The realization of efficient and cost-effective drone delivery applications can be facilitated by a combination of Commercial Off-The-Shelf (COTS) technologies and systems, possibly sourced from other industries. Moreover, integration with existing planning and flight management infrastructures in the concept of Urban Air Mobility (UAM) [

9] and incorporating established aviation technologies such as the integration of the ADS-B (Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast) surveillance protocol ensures compatibility with existing airspace users and safety of operations [

10]. BVLOS demands levels of autonomy and collaboration that have hitherto only been seen in the autonomous vehicle market. It is expected that technologies developed for those markets can be exploited for drone application. Technology must be compliant with the regulatory framework, that needs to be defined. Fortunately, that process is already in flow with U-space (U-space), building and testing the operational and regulatory framework that enables this new dawn from a regulatory and compliance perspective [

11].

1.2. Scope and contributions

This paper provides an overview of the enabling technologies that play a pivotal role in advancing the field of BVLOS operations. We explore the essential technological components, architectures, algorithms and protocols and shed light on the critical aspects that fascilitate safety and reliability in BVLOS scenarios, while adopting a risk-based approach. In this way, we pave the way for future endeavors to address these gaps and boost BVLOS operations towards greater efficacy, security, and success. To support the work, the Arcadia and Capella tools [

12] were used to develop a drone reference logical architecture. This created an improved understanding between market and operational needs (e.g., capabilities needed to operate within U-space [

13]) and to better identify integration requirements between the different capabilities to be developed.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 discusses various background studies related technological developments of UAVs.

Section 3 explains the proposed architecture and related components.

Section 4 presents the implementation details that verify the performance with existing work. Finally, a conclusion with future directions is presented in

Section 5.

2. Related Work

Nowadays BVLOS flights open a myriad of applications revolutionizing various industries, from goods delivery to safety and security, through surveying, crowd management, as well as search and rescue [

14]. Drones can make a significantly positive impact on customer satisfaction by enhancing the quality of delivery services. In recent years many leading retail companies, such as Amazon, Google, and Walmart were introducing drone delivery services [

15]. “Amazon Prime Air” was initiated by Amazon to deliver packages of 2.3 kg within thirty minutes at a distance of 16 km from click to delivery [

16]. After introducing innovative sensor technologies and communication systems to their UAS delivery services, the company aspired to reduce noise pollution, eliminate carbon footprint and facilitate safer and more reliable services. In 2019, DHL launched its first fully automated, intelligent drone delivery solution in China which reduces one-way delivery time from 40 minutes to only eight minutes and can save costs of up to 80% per delivery, with reduced energy consumption and carbon footprint compared to road transportation [

17].

The key to unlock the potential of UAS, and allow various related applications to bloom, is to develop components, systems and architectures for autonomous, intelligent and safe UAS use, beginning from the industrial domain(s) for components, over system design and development with cross-domain contributions to system architectures for resilience, robustness and collaboration air-to-ground. SESAR (Single European Sky Air Traffic Management Research) has already started work on regulatory and procedural structures for drone co-existence with crewed traffic with the U-space architecture and has defined levels of implementation of that architecture U1-U4 covering the period from 2019 to 2035 [

11]. In the following sections we present some of the key technologies that have been identified as key drives for safe and reliable UAS operations.

2.1. Cooperative Detect and Avoid

Detect and Avoid (DAA) technologies are key to unlocking commercially viable BVLOS operations, as they allow a safe and efficient integration into civilian airspace, by helping UAS to avoid collisions with other aircraft, buildings, and other obstacles. The growing number of UAS applications has made a necessity for sophisticated and highly dependable collision avoidance systems evident and incontestable from the public safety perspective[

18]. Such systems are based on the use of sensors to detect and position of obstacles to subsequently establish maneuvers to guarantee the safety of the aircraft Many recent works implement LiDAR (Light Detecting And Ranging), vision cameras, thermal or infrared cameras for collision avoidance of UAS [

10,

19].

The detection of possible objects in the navigation space can be also realised through pattern recognition technology which includes methods for identifying relevant characteristic features of an object through image processing algorithms. Deep learning algorithms for object detection with high sensitivity to data restructuring are the most common approaches in object detection and classification [

20].

2.2. Communication technologies

The reliability of UAS communication technology is essential for their wider deployment. The commercialization of the fifth generation networks (5G) technology provides UAS communication with ultra-high speed, very low latency, high data rate transmissions and other capabilities, which effectively solve the problem of UAS communication quality [

21], at least when the operational volume is within the coverage of the mobile network. However, current UAS communication systems still face several limitations in terms of UAV aerial base station (BS) deployments, spectrum utilization and energy consumption of UAV communication [

22]. Extensive research has been conducted regarding UAV groups, categories, sorting, charging, and adjustment. In latest years, the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) defined a new concept called “Multi-access Edge Computing” (MEC) which refers to the deployment of cloud computing services at the edge of the cellular network. UAVs can be integrated in MEC networks as users that execute various computing tasks [

23]. Such systems can significantly decrease network congestion and increase the network performance in applications related to task allocation [

24].

Future UAS applications have stricter demand for latency, data rates and reliability and channel variations introduced by their mobility, which in turn relocates research interest beyond fifth-generation (B5G) mobile communications. Emerging UAS scenarios include drones that can act as mobile roadside units (RSUs), gathering data from an area and transmitting that data to terrestrial vehicles, stationary RSUs, and other nearby drones. UAS networks can be deployed faster than any other stable network infrastructure system; thus, it is better to use them as the basis of mobile infrastructure networks for remote locations[

25]. To enhance network and performance in UAS communication, existing literature has explored various emerging wireless communication technologies, such Non-orthogonal multiple access (NOMA) which prevails over the traditional orthogonal frequency-division multiple access (OFDMA) schemes due to its unique characteristics, such as enhanced spectrum efficiency (SE), reduced traffic latency with high reliability [

26].

2.3. Autonomous navigation

Awareness of the UAS surroundings is a key aspect of BVLOS operations, particularly in large-scale and complex environments. Drone navigation is characterized by two fundamental components: path-planning and obstacle detection and avoidance. Path planning involves determining an optimal trajectory for the drone and defining parameters such as the velocity and turns over time, to achieve optimality in the trajectory generation. As such, each autonomous flight is characterised by an objective, either being the arrival to certain target point, or the aim of maximizing the information coverage [

27]. With regards to UAS navigation, different path-planning alternatives can be used depending on the specific requirements of the application [

28]. These methods can be classified in two categories, those that are based on a sampling of the search space and those that employ artificial intelligence (AI) to find a solution with respect to the representation of the environment [

29].

Recent works on autonomous UAV navigation have mainly focused on the creation of a 3D map of the surrounding environment. This 3D deployment and resource utilization has been addressed by powerful optimization methods such as convex optimization [

30], or game theory [

31]. In addition, various path planning methods have been deployed for obtaining optimal paths, graph based methods such as the A* algorithm [

32,

33], or evolutionary methods such as the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [

34,

35]. The observation that UAS navigation can be treated as a sequential decision-making problem, has led more and more researchers to the use of learning-based methods for solving complex navigation problems and intelligently managing onboard resources [

36]. AI and ML models play a vital role to all these tasks as the main part of the processing pipeline, which begins with data collection and pre-processing and ends with inference and decision making in real-time. The models for some tasks are continuously or periodically trained in order to adapt to new conditions and environments and this process can be carried out either online or offline. Recent works have implemented the Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) algorithm for solving UAs reactive navigation problems in simulated environment [

37] or in real world conditions [

38].

Although autonomous navigation methods are continuously evolving, driven by technological advancements, BVLOS can only be successful if carried out in concert with other roadmaps for regulatory development and operating standards and procedures. Initiatives to unify European regulatory standards for commercial drone operation have been introduced by by EASA and a Specific Operations Risk Assessment (SORA) can be conducted that aids safety and compliance for operations in urban environments. Moreover, if the planned operation reaches into airspace where the drone may come into contact with traditional (manned) aviation, the upcoming regulations around U-space come into play, as currently being developed by SESAR [

39].

3. Architecture and Functionalities

In this section we present a comprehensive overview of the proposed technologies, architectures, algorithms, and protocols that are crucial for a UAS sub-system to effectively manage navigation tasks for the further enhancement of highly reliable and secure drone missions.

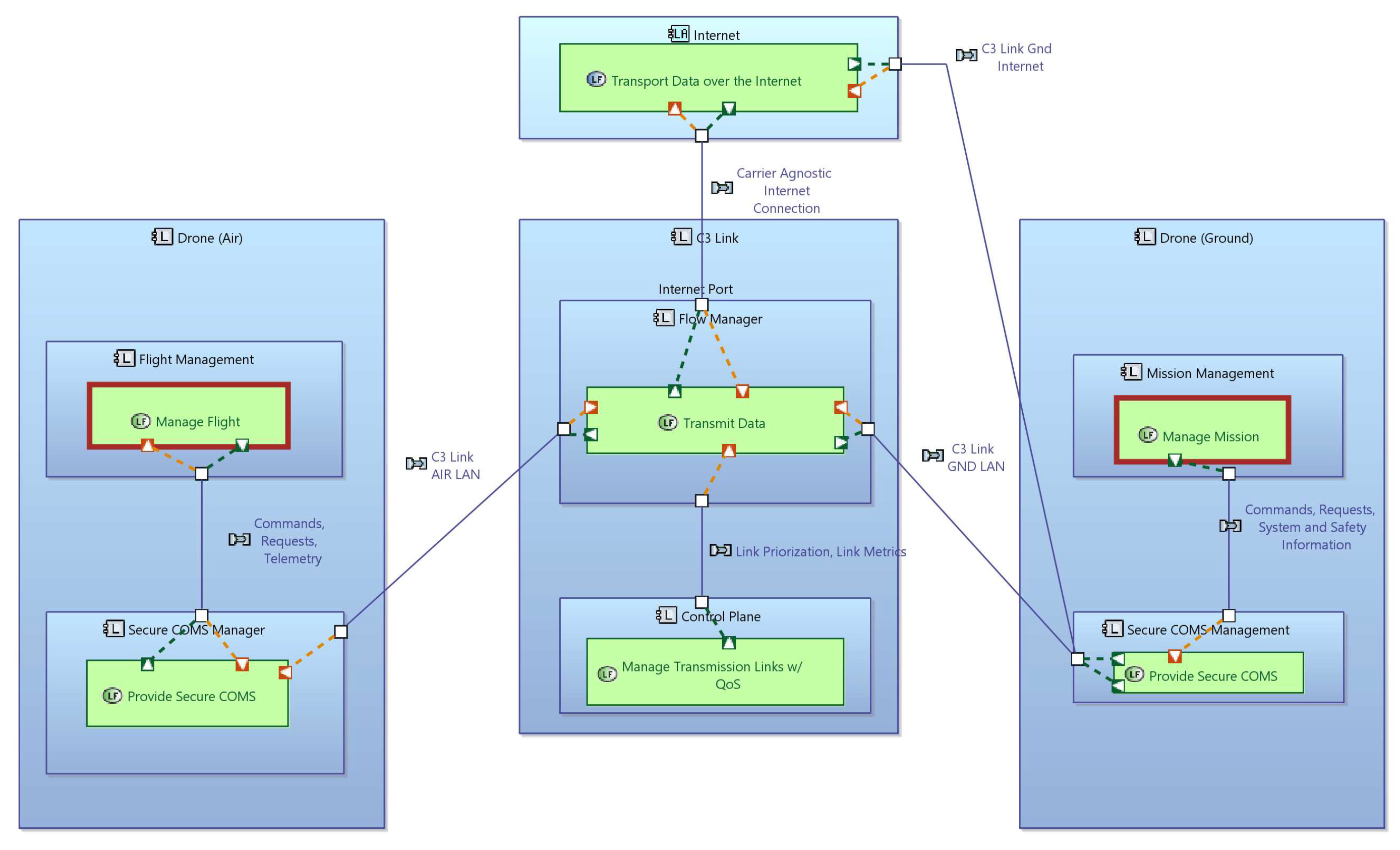

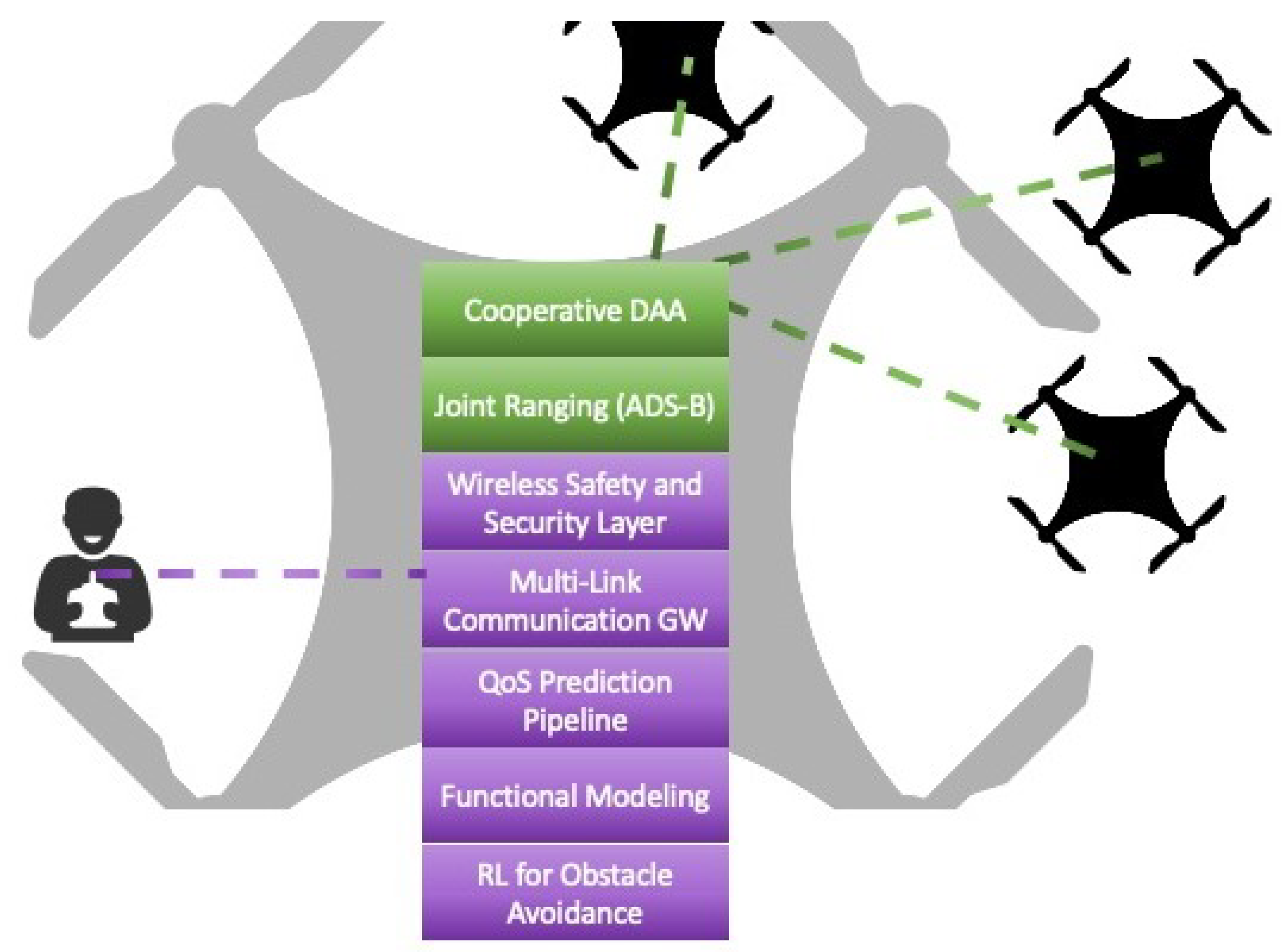

Figure 1 depicts the overview of the technologies developed to tackle this challenge.

To build and operate UAS safely and economically, it makes sense to base the systems on available commercial technologies and services where possible. This is true for the command, control and communication (C3) link as well. Public mobile communication networks are a prime example of this, as well as WiFi and similar technologies for more local links, or satellite links to achieve an even larger operational area. The usage of economically viable, commercial service providers or off-the-shelf technologies allows to increase the reliability of the connection between UAV and operator, through redundancy via the use of multiple underlying links for the C3 link.

Compared to the technologies used in traditional aviation, commercial mass market communication technologies evolve much faster: 3GPPP releases a new standard every 18 months, while for instance some of the newest digital communication systems in aviation, such as ADS-B and Controller Pilot Data Link Communications (CPDLC), follow standards that have been frozen for years [

40]. To create a sustainable system design for the C3 link, it has to support diverse technologies and identify the key functions needed to guide the software development to bridge between the on-board system and the firmware of the communication modules for each communication technology. For instance, a system built around 5G as the current state of the art in mobile communication, should be able to incorporate 6G as it becomes available, while maintaining the architecture and the main functional blocks, as shown in

Figure 2.

Among other things, this identification of the functional blocks allows to put the necessary focus on the control plane of the C3 link, which in turn will allow to develop system components for network telemetry, measurement of Quality of Service (QoS) and use these data to actively select the best available link at any given time of the flight. To distribute the data on the links, an evaluation of their QoS is necessary. Especially in complex network structures such as mobile radio, the QoS can fluctuate significantly and are difficult to predict in contrast to direct connections where functions that calculate the path loss according to the distance to the transmitter can be applied. For example, with cellular connections latency spikes can occur during the handover between two mobile radio base stations. Moreover, within the context of UAVs connected via mobile radio, there is a degradation of the QoS with rising altitudes [

41]. In order to predict these fluctuations before they occur and to be able to initiate countermeasures, if necessary, a Deep Learning (DL)-based QoS prediction model is being developed.

To support the technology-independent system architecture, three main components are needed for the high-level functioning of the C3 link in this architecture:

Interface to the data links with an API for the access technologies, allowing to incorporate new technologies as they become available or as needed to support specific operational scenarios

Interface to system component to determine link availability

Detecting possible obstacles interface to the QoS estimation and prediction component

4. Implementation

To enable BVLOS operations in the future, a range of new technologies have been developed and approaches from other industries have been refined to enable a risk-based operation. The following section presents these advancements.

4.1. Functional modelling

In this work, the Arcadia methodology and the Capella tool were used to improve robustness of the proposed technologies and architectures. At the operational level, from U-space, the high level capabilities of "Detect and Avoid"; "Command and Control"; "Communication, Navigation & Surveillance" are of particular interest. To these, the general capability of "BVLOS Drone Logistic Services" serves as a business motivator and operational driver to frame their deployment.

Figure 2.

Logical architecture for a C3 Link leveraging a generic, carrier agnostic connection to the internet to enable high availability and QoS.

Figure 2.

Logical architecture for a C3 Link leveraging a generic, carrier agnostic connection to the internet to enable high availability and QoS.

As an example of this part of the work,

Figure 2 shows a Logical Architecture diagram for the C3 link developed by AnyWi. This logical architecture abstracts the C3 Link as a logical entity, that transports all messages between air and ground. A key concept is leveraging the internet infrastructure, being link agnostic. This allows the implementation of the architecture for mobile networks, but also other wireless types, as WiFi or Sat-COM. The architecture thus comprises a QoS function, that ensures optimal selection of the best link (or links) to transmit the data. The further development of this logical architecture into the physical level will see the decomposition and allocation of blocks and functions to dedicated physical blocks in the air segment (i.e., drone) and ground segment (i.e., ground station). This logical perspective also makes the re-use of functions between ground and air clear.

Interface to the data links consists of a UDP-based protocol to transmit data in the two directions, from drone to ground and ground to drone. UDP is chosen here as it allows to incorporate the highest number of access technologies, from WiFi local links, over mobile networks to Sat-COM. A specific state machine-based technical architecture is developed, where state machines track the state of each UDP-based connection, as well as the multi-link connection consisting of one or more of the underlying UDP connections.

Interface to a system component to determine link availability. Links become available, or not available, as the aircraft moves over the flight geography and the control plane of the C3 link needs to detect this and adjust its algorithms for link selection for each data packet. Current Linux-based systems make this information available through the networking stack and the device drivers, but with a significant delay. For instance drivers for mobile network modules report the link available for many seconds after packet loss has reached 100%. Hence, the control place must detect this situation and react accordingly based on information that it collects itself.

Interface to the QoS estimation and prediction component. This component is discussed in the section on communication modules.

4.2. Cooperative Detect and Avoid

ICAO defined DAA in ICAO Annex 2 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation [

42]: ‘Rules of the Air’: “The capability to see, sense or detect conflicting traffic or other hazards and take the appropriate action.” This definition makes the detection and avoidance functionality even wider and broader than only the detection of other aircraft and having the UAV to avoid them. Looking from this wider perspective, the following functions can be distinguished:

Detection of other manned and unmanned aircraft

Tracking of the detected aircraft

Detecting possible obstacles (e.g. buildings, structures, persons)

-

Determining an avoidance manoeuvre

- -

Avoidance in the sense of ‘Remain Well Clear’ (RWC)

- -

Avoidance in the sense of Collision Avoidance (CA)

Executing the determined avoidance manoeuvre

To perform these functions, the DAA-system requires both sensors and computing power, ideally placed on-board of the UA, to perform these functions. This on-board placement is preferred to ensure a high level of autonomy and reduces reliance on communication systems and possible system failures, especially in the case of highly automated operations.

With respect to the sensor systems, the DAA-system is preferably equipped with both cooperative and non-cooperative sensors. A cooperative sensor could make use for instance of the already available transponder systems on-board of manned aircraft and new systems on-board of unmanned aircraft, such as Electronic Conspicuity (e-Conspicuity) and ADS-L (Light). A non-cooperative sensor could be a DAA-radar system or other system able to detect and track other aircraft without any communication. The non-cooperative sensor would also be needed to detect ground obstacles.

Thus, the minimum DAA-system hardware would consist of two sensors and a computer. Taking into account that the system is required on all BVLOS operating UA, this makes Size, Weight, and Power (SWaP) an important aspect of the system, next to the overall safety level, and thus airworthiness aspect.

4.3. Communication modules

The prediction of QoS for mobile radio connections such as LTE, 5G and, in future, 6G [

43] is a current research topic. For example, Machine Learning models have been evaluated by Khatouni et al. [

44] to predict the Round-trip Time (RTT) for LTE connections. Especially in the field of automotive for V2X communication, there are several works on predicting the QoS for the mobile network. In this research field, models for V2X communication based on LTE [

45,

46] as well as 5G [

47,

48] have been studied. The models applied for QoS prediction range from Support Vector Machines, Decision Trees, Random Forest [

44,

45,

46,

47] to DL models such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) based architectures [

45,

49]. The related work presented include model deployment [

46] and QoS prediction in the UAV context [

49]. However, none of the researched methods describe QoS prediction to improve the connection between the operator and UAV for the BVLOS use case. In addition, deployment and integration on the UAV poses special demands on the weight and power consumption of the hardware used. In contrast to the previous approaches, the developed system represents a holistic approach that addresses these difficulties, whereby it is integrated into the Multi-Link Communication Gateway.

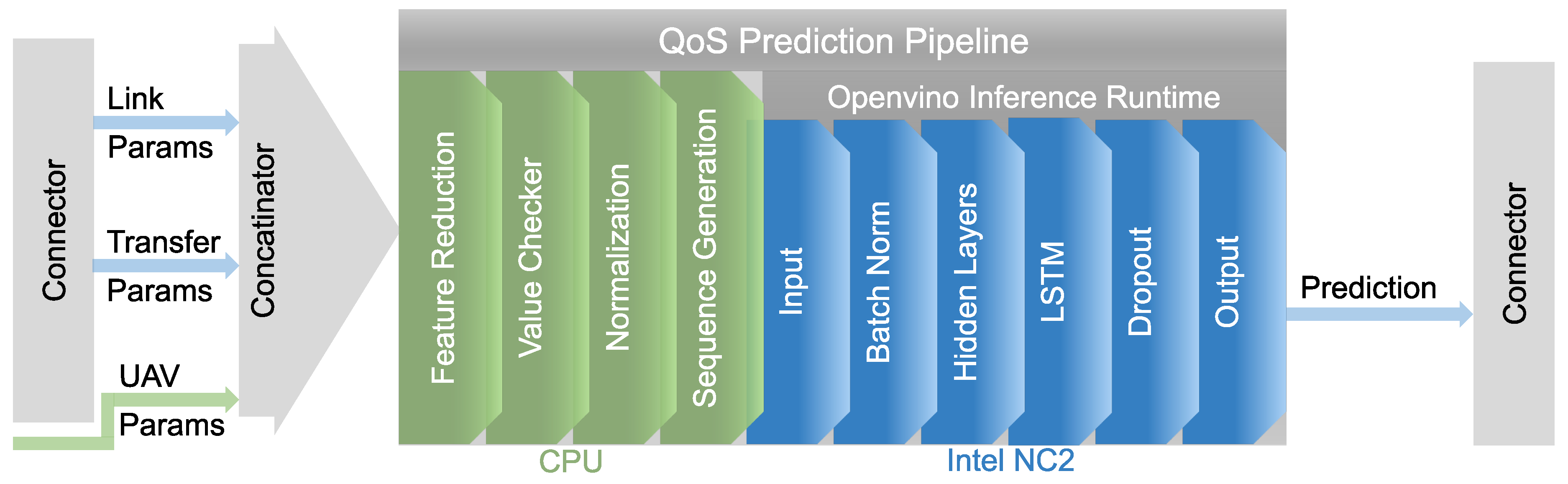

All software parts are designed to be executable on low weight and power, making them well suited for UAS deployment on an NXP Layerscape FRWY-LS1012A board with an Intel Neural Compute Stick 2 connected via the USB interface. This hardware offers low weight and power consumption but enough processing power for BVLOS drone use-case. An overview of the implemented QoS prediction pipeline is shown in

Figure 3. There, the real-time measurement data of the mobile network link is received from the gateway by the Connector. This provides two data streams to the Concatenator. One with Link Parameters, which provide the physical parameters of the radio connection such as signal strength and a second one feeding the Transfer Parameters containing the properties of the link on packet level, e.g. RTT. In the Concatenator, the streams are merged with additional UAV data based on the measurement timestamps. The UAV parameter include, for example, the height above the ground, as the reliability of the mobile radio connection generally decreases with increasing height [

41]. The parameters are then forwarded to the prediction pipeline, whereby the steps marked in green are processed on the CPU and the blue ones are deployed on the AI accelerator. First, a feature reduction is executed based on the variance and the correlation of the features from the training. Subsequently, the value ranges of relevant features are checked and adjusted, if necessary, followed by normalization, which is mainly included to reduce the quantization error induced by the model input. In the next step, the features of multiple measurement points are accumulated as a sequence with fixed length according to the first in - first out principle. The resulting matrix is fed into the DL model running on the Intel Neural Compute Stick 2. The handling of the data exchange between CPU and stick as well as the inference execution is made possible by using the Openvino

TM Inference Runtime.

When designing the model architecture, attention was paid not only to prediction accuracy, but also to model deployment in terms of the usability of individual layers on the Intel stick and model size, and thus also to inference time. For example, unlike the LSTM layers, no gated recurrent units are supported. The model itself consists of an Input and a Batch Norm layer, which is used during model training to reduce overfitting. As well as Hidden Layers, which consists of several connected LSTM, Dropout and Dense layers. The number of hidden layers, the unit sizes of the LSTMs and the dropout rate are hyperparameters that were determined using suitable optimization algorithms. Finally, the outputs are generated in a final LSTM and dropout layer followed by an output layer consisting of dense nodes. The output includes prediction values for different time horizons for the RTT as well as pseudo-probability values for an occurring edge. An edge is defined as an increase of at least 50 in the RTT between two sample points. The predicted values are forwarded to the Multi-Link Communication Gateway via the connector, where it will be processed to evaluate the usability of the mobile link.

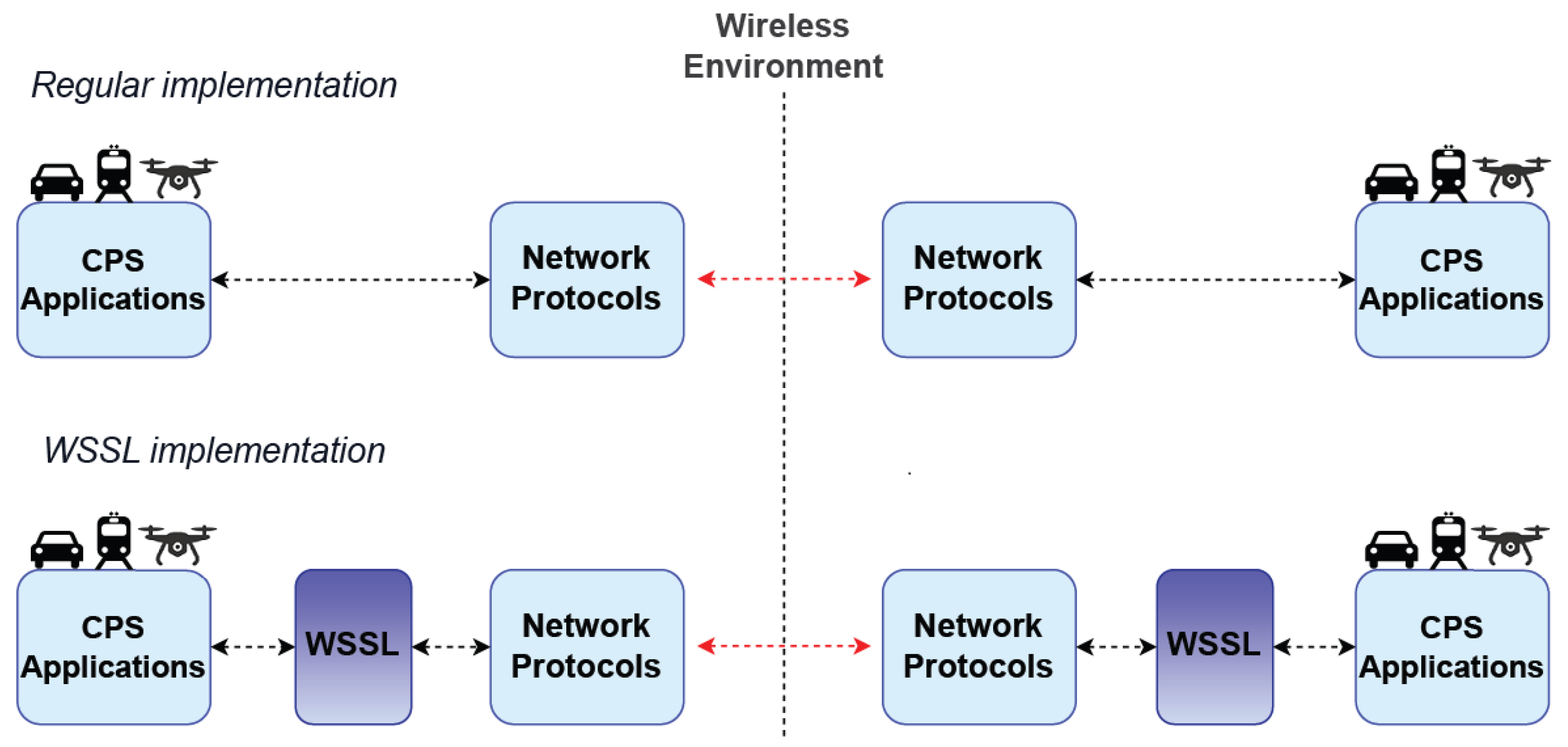

4.4. Wireless Safety and Security Layer

The primary function of the WSSL is the detection of communication issues between CPS devices, whether or not caused by malicious agents. These issues can be message repetition, packet loss, or inter-message delay. By definition, this is assumed to be the safety layer of WSSL. In addition, WSSL implements a message signing model, ensuring increased communication security by allowing the receiver to confirm that the received message comes from the correct sender. This signature model guarantees the integrity of the received messages, discarding those with data loss. The Wireless Safety and Security Layer (WSSL) consists of an additional layer to the adopted communication system, implementing a detection process for relevant communication issues, establishing a safe and secure connection between each WSSL endpoint, and providing an extra level of confidence to the cyber-physical system (CPS) devices. Its use seeks to increase trust between the sender and receiver since communication failures or malicious interactions can have critical consequences. It can be used in open communication systems, where transmissions are unsafe. The implementation is agnostic to the used communication protocols, thus being generically applicable to many use-cases, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

Considering the diversity of CPS devices, WSSL was developed as a static library compiled in C++. It can be attached to most systems on specific hardware or as part of the original system. Thus, its implementation cost is minimal, and its benefits significant, allowing its application in low-cost or high-performance systems. Although it detects the conditions and problems of the communications network, WSSL does not alter the operation of the device it was implemented in, informing the application about the detection of the event so that the device can handle it.

4.5. Robust spatio-temporal awareness of UAV swarms

To realize BVLOS operations, accurate spatio-temporal awareness of a UAV is essential. This is typically achieved by exploiting various surveillance methods e.g., primary surveillance radar (PSR), which measures the distance and bearing of the target. A popular alternative to PSR is the secondary surveillance radar (SSR) system, which considers the aerial vehicle to be equipped with a radar transponder that can respond to an interrogation signal with encoded information about the identity and state of the aerial vehicle, e.g. position and velocity. Modern methods of secondary surveillance include the mono-pulse secondary surveillance radar (MSSR) and Traffic Collision and Avoidance System (TCAS) or internationally known as the Airborne Collision Avoidance System (ACAS) [

50,

51]. The TCAS or ACAS system typically employ SSR in Mode-S operation with an onboard integrator, for cooperative DAA and thus enabling safe integration of UAVs in civilian air spaces [

52]. More recently, sensor-fusion based low-complexity and efficient estimators have been proposed, which offer a more accurate radial velocity estimation as compared to the ACAS [

53].

An alternative for SSR methods is the Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast (ADS-B) system [

54], which requires no interrogation signal from the ground. An aerial vehicle equipped with a GPS sensor, an IMU and an ADS-B transponder can asynchronously broadcast in real-time their position, velocity and identification, to aircraft traffic control (ATC) and other aerial vehicles. ADS-B systems are considered to be a key component of the future air transportation system and is mandated by EUROCONTROL in Europe and FAA in the U.S. for all aerial vehicles since 2020 (see [

55] and references within).

However, modern ADS-B systems are plagued with noisy data and packet losses, which cause the state of the aerial vehicle to be intermittently unknown. To overcome this limitation, model-based tracking methods for trajectory prediction are typically employed [

56,

57]. In case of UAVs advanced neural networks e.g, Long Short-Term Memory [

58,

59] have recently shown promising results for accurately tracking the agent trajectory. In the future, for a network of UAVs, distributed state-space models can be employed for reliable tracking of the state variables, e.g. distributed Kalman filtering [

60,

61] or distributed particle filtering [

62,

63].

A direct approach to resolve packet losses, is to use blind source separation methods, however these solutions suffer from sign ambiguity and require the number of receive antennas not to be larger than the number of drones/aircraft [

64]. More recently, to enable robust UAV navigation, joint range and phase offset estimation algorithms have been developed which enables coherent detection of a single or (collided) multiple ADS-B packets with a significantly lower Packet Error Rate (PER) compared to non-coherent detection methods, and can estimate the range of multiple drones/aircraft using only a single receive antenna [

65].

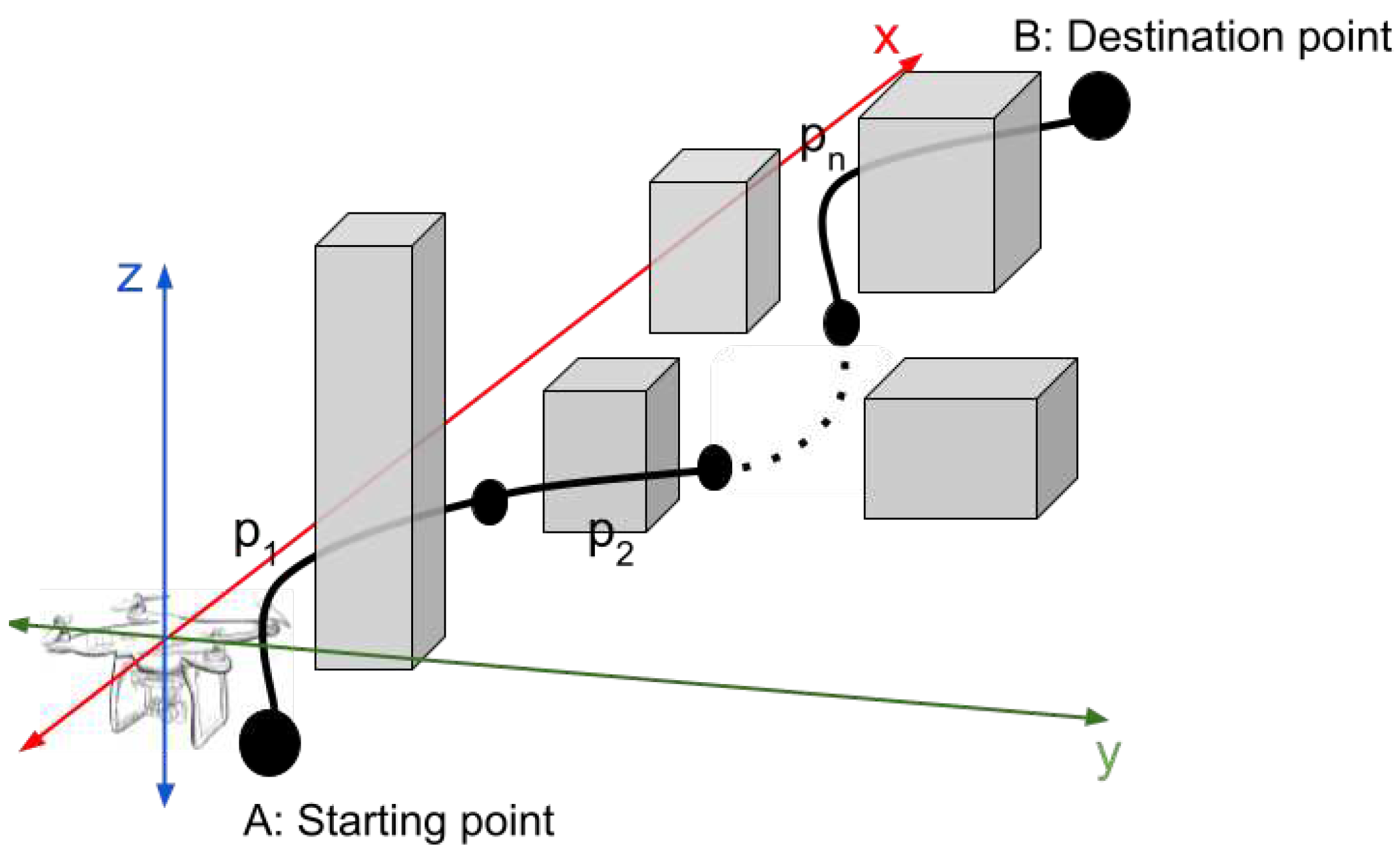

4.6. Autonomous navigation and scene perception

In BVLOS operations the efficient perception of the UAV surroundings, as well as the safe and fast navigation are critical for data collection and environmental exploration tasks. This is particularly true in the case of dynamic environments, where the landscape composition is not known in advance and obstacles may appear as the planned trajectory is executed. Therefore, obtaining an appropriate trajectory that safely leads a UAV from its initial position to its final destination is key in autonomous operations.

Recent literature has explored various path planning techniques for generating optimal trajectories in BVLOS operation in dynamic environments with various obstacles, where the term "optimal" may refer to the path length, time of execution or energy output. Some examples are graph-based space search algorithms [

66,

67], swarm intelligence algorithms [

68], artificial potential field (APF) methods [

69,

70] or reinforcement learning (RL). Particularly reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms have been extensively used for autonomous navigation as they generate robust and efficient solutions with great performance [

38,

71].

In this work we investigated the typical navigation problem for UAVs through unknown environments and dynamic obstacles. The proposed approach is showcased in the

Figure 5

The performance of two common reinforcement learning algorithms, namely Advanced Actor Critic (A2C), and Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) was tested against the traditional graph-based methods A* for obtaining optimal trajectories through dynamic and unknown environments with various obstacles, based on a given map and the actual position of the UAV, the location of its target and the detected obstacles. Environmental perception was achieved with the deployment of low-cost sensors through the Microsoft AirSim

1 simulator with four distance sensors attached to a quad copter in the following positions: three sensors placed in the middle of the drone for detecting the edges of obstacles and one sensor at the bottom for the distance between the ground and any obstacle below. Through our simulations we performed a comparative analysis of the proposed algorithms based on the length of trajectory, flight duration and safety of flight. In general the PPO and A2C algorithms demonstrate great performance due to their ability to learn from past experiences and optimize their policy accordingly. Particularly, in our simulations the PPO algorithm attained an optimal path with 99% success rate, while it also accomplished trajectories of shorter length in comparison to the other two algorithms. Because RL algorithms are implemented using low-cost sensors, they outperform traditional methods in terms of robustness and efficiency. On the contrary, the A* algorithm is a solid and reliable solution for path planning problems, although rely on more expensive LiDAR sensors and therefore are computationally more complex. After several training epochs for the Reinforcement Learning algorithms that we trained (A2C and PPO) we resulted in a significantly better performance for PPO compared to the performance of an implementation of A* that gradually finds a path to the target (end-point) while learning the obstacles ahead.

4.7. Societal acceptance of BVLOS operations

As drone technologies continue to emerge with obvious benefits along the way, it remains uncertain whether the public opinion and perception is for or against adopting UAS. Technological and scientific improvements as well as the development of more reliable frameworks aim to further boost their adoption in the future. Although the UAV market already has a great variety of hardware, software, and operational products to offer, the key element for their successful implementation is hardly defined by those aspects, but largely depends on the adoption of its users and more importantly on the acceptance of the wider public. However, it also largely depends on their integration and the conformance of the final results to local regulation [

72]. Without the wide acceptance of society, drones will be unable to exploit their considerable potential as tools for smarter cities. The key to unlock the potential of drones, and allow applications to bloom, is to integrate them within the daily routine and activities of the society. Since UAVs are still at a low level of implementation, collecting actual experiences by users remains a challenging task [

73].

5. Conclusions

This paper presents the challenges that state of the art technologies face for supporting BVLOS drone flights. It is pointed out, that in order to facilitate risk-based flight missions for BLVOS operations, further enhancements of the technologies are essential to ensure their maximum reliability and minimal risk of failure. Therefore, in this paper the concept of a risk-based approach to BVLOS operations is investigated, aiming to address the challenges and uncertainties associated with these operations while promoting their safe and efficient integration into the airspace. Specifically, the combination of technological components, architectures and protocols that drive future UAS growth was presented, while related opportunities and challenges were discussed. In order to future-proof the systems and facilitate their development, a drone reference logical architecture was developed using the Arcadia and Capella tools as exemplified in section 3 with reliable communications. In the process, we prioritized understanding the intersection between market and operational demands while identifying integration necessities among the various capabilities. The enhanced technologies treated in this paper encompass collision avoidance methods, namely Cooperative DAA and ADS-B, communication systems incorporating redundant connections, QoS prediction algorithms, and a safety and security framework, in addition to reinforcement learning-fuelled autonomous navigation and scene perception capabilities. To conclude, with this paper several key pillars towards autonomous BVLOS operation according to the U-space are addressed. Finally, we set the scene for future research towards realizing the full potential of BVLOS into the rapidly evolving airspace.

Acknowledgments

ADACORSA has received funding from the ECSEL Joint Undertaking (JU) and National Authorities under grant agreement No 876019. Follow

www.adacorsa.eu for more information.

References

- Organization, I.C.A. ICAO Cir 328, Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS). Available online: https://www.icao.int/Meetings/UAS/Documents/Circular%20328_en.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2023).

- Nex, F.; Armenakis, C.; Cramer, M.; Cucci, D.A.; Gerke, M.; Honkavaara, E.; Kukko, A.; Persello, C.; Skaloud, J. UAV in the advent of the twenties: Where we stand and what is next. ISPRS journal of photogrammetry and remote sensing 2022, 184, 215–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, W.; Hong, D.; Tao, R.; Du, Q. Deep learning for unmanned aerial vehicle-based object detection and tracking: A survey. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2021, 10, 91–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawad, W.; Halima, N.B.; Aziz, L. An Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) System for Disaster and Crisis Management in Smart Cities. Electronics 2023, 12, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velusamy, P.; Rajendran, S.; Mahendran, R.K.; Naseer, S.; Shafiq, M.; Choi, J.G. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV) in precision agriculture: Applications and challenges. Energies 2021, 15, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, R.J.a.L.; Henderson, I.L.; Jackson, C.L. BVLOS unmanned aircraft operations in forest environments. Drones 2022, 6, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, W.; Gong, W.; Lu, Z.; Yan, H.; Wei, W.; Wang, Z.; Shen, C.; Pang, J. LiDAR-Assisted UAV Stereo Vision Detection in Railway Freight Transport Measurement. Drones 2022, 6, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozioł, A.; Sobczyk, A. Usage of unmanned aerial vehicles in medical services: A review. Materials Research Proceedings 2022, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Straubinger, A.; Rothfeld, R.; Shamiyeh, M.; Büchter, K.D.; Kaiser, J.; Plötner, K.O. An overview of current research and developments in urban air mobility–Setting the scene for UAM introduction. Journal of Air Transport Management 2020, 87, 101852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldao, E.; González-de Santos, L.M.; González-Jorge, H. Lidar based detect and avoid system for uav navigation in uam corridors. Drones 2022, 6, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undertaking, S.J. ; others. U-space: blueprint. 2017.

- Voirin, J.L. Model-based system and architecture engineering with the arcadia method; 2017; pp. 1–368.

- EUROCONTROL. U-space CONOPS 4th Edition. Technical report, SESAR, 2023. [Online; accessed 01-October-2023].

- Tan, L.K.L.; Lim, B.C.; Park, G.; Low, K.H.; Yeo, V.C.S. Public acceptance of drone applications in a highly urbanized environment. Technology in Society 2021, 64, 101462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.; Yu, E.; Jung, J. Drone delivery: Factors affecting the public’s attitude and intention to adopt. Telematics and Informatics 2018, 35, 1687–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazon. Amazon reveals the new design for Prime Air’s delivery drone. https://www.aboutamazon.com/news/transportation/amazon-prime-air-delivery-drone-reveal-photos, 2022. [Online; accessed 30-July-2023].

- Press, D. DHL EXPRESS LAUNCHES ITS FIRST REGULAR FULLY-AUTOMATED AND INTELLIGENT URBAN DRONE DELIVERY SERVICE. https://www.dhl.com/global-en/home/press/press-archive/2019/dhl-express-launches-its-first-regular-fully-automated-and-intelligent-urban-drone-delivery-service.html, 2019. [Online; accessed 30-July-2023].

- Mikołajczyk, T.; Mikołajewski, D.; Kłodowski, A.; ukaszewicz, A.; Mikołajewska, E.; Paczkowski, T.; Macko, M.; Skornia, M. Energy Sources of Mobile Robot Power Systems: A Systematic Review and Comparison of Efficiency. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 7547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horla, D.; Giernacki, W.; Báča, T.; Spurny, V.; Saska, M. AL-TUNE: A family of methods to effectively tune UAV controllers in in-flight conditions. Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems 2021, 103, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, B.; Al Said, N.; Dong, B. New technologies for UAV navigation with real-time pattern recognition. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogra, A.; Jha, R.K.; Jain, S. A survey on beyond 5G network with the advent of 6G: Architecture and emerging technologies. IEEE Access 2020, 9, 67512–67547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Jin, X.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, P.; Ren, J.; Yao, J.; Zhang, S. A survey of energy efficient methods for UAV communication. Vehicular Communications, 1005. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.; Zhang, G. A survey on UAV-assisted wireless communications: Recent advances and future trends. Computer Communications 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmatov, N.; Baek, H. RIS-carried UAV communication: Current research, challenges, and future trends. ICT Express 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerna, A.; Bitam, S.; Calafate, C.T. Roadside unit deployment in internet of vehicles systems: A survey. Sensors 2022, 22, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, T.; Liu, Y.; Song, Z.; Sun, X.; Chen, Y. Exploiting NOMA for UAV communications in large-scale cellular networks. IEEE Transactions on Communications 2019, 67, 6897–6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yi, Z.; Liu, Y.; Huang, K.; Huang, H. Survey on path and view planning for UAVs. Virtual Reality & Intelligent Hardware 2020, 2, 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.; Djahel, S.; Welsh, K. Path-planning for unmanned aerial vehicles with environment complexity considerations: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Kumar, N. Path planning techniques for unmanned aerial vehicles: A review, solutions, and challenges. Computer Communications 2020, 149, 270–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Fei, Z.; Zhang, Y. UAV communications for 5G and beyond: Recent advances and future trends. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2018, 6, 2241–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Peng, M.; Cao, X. A game theory approach for joint access selection and resource allocation in UAV assisted IoT communication networks. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2018, 6, 1663–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Xi, Q.; Xing, X.; Gui, H.; Liu, Q. Path planning for UAV tracking target based on improved A-star algorithm. 2019 1st International Conference on Industrial Artificial Intelligence (IAI). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–6.

- Flores-Caballero, G.; Rodríguez-Molina, A.; Aldape-Pérez, M.; Villarreal-Cervantes, M.G. Optimized path-planning in continuous spaces for unmanned aerial vehicles using meta-heuristics. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 176774–176788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.J.; Bang, H. UAV path planning under dynamic threats using an improved PSO algorithm. International Journal of Aerospace Engineering 2020, 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayeem, G.M.; Fan, M.; Akhter, Y. A time-varying adaptive inertia weight based modified PSO algorithm for UAV path planning. 2021 2nd International Conference on Robotics, Electrical and Signal Processing Techniques (ICREST). IEEE, 2021, pp. 573–576.

- Rezwan, S.; Choi, W. Artificial intelligence approaches for UAV navigation: Recent advances and future challenges. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 26320–26339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X. Deep-reinforcement-learning-based autonomous UAV navigation with sparse rewards. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 7, 6180–6190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Aouf, N.; Song, B. Explainable Deep Reinforcement Learning for UAV autonomous path planning. Aerospace science and technology 2021, 118, 107052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttunen, M. Drone operations in the specific category: A unique approach to aviation safety. The Aviation & Space Journal 2019, 18, 2–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kožović, D.V.; Đurđević, D.Ž.; Dinulović, M.R.; Milić, S.; Rašuo, B.P. Air traffic modernization and control: ADS-B system implementation update 2022: A review. FME Transactions 2023, 51, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purucker, P.; Schmid, J.; Höß, A.; Schuller, B.W. System Requirements Specification for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) to Server Communication. 2021 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS); IEEE: Athens, Greece, 2021; pp. 1499–1508. ISSN 2575-7296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annex, I. ICAO Annex 2 to the Convention on International Civil Aviation–Rules of the Air 2.

- Networks, G.S.; Association, S.I. Key Strategies for 6G Smart Networks and Services. https://6g-ia.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/6g-ia-position-paper_2023_final.pdf, 2023. [Online; accessed 01-October-2023].

- Khatouni, A.S.; Soro, F.; Giordano, D. A Machine Learning Application for Latency Prediction in Operational 4G Networks. 2019 IFIP/IEEE Symposium on Integrated Network and Service Management (IM), 2019, pp. 71–74. ISSN: 1573-0077.

- Torres-Figueroa, L.; Schepker, H.F.; Jiru, J. QoS Evaluation and Prediction for C-V2X Communication in Commercially-Deployed LTE and Mobile Edge Networks. 2020 IEEE 91st Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2020-Spring), 2020, pp. 1–7. 2: ISSN, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, J.; Purucker, P.; Schneider, M.; vander Zwet, R.; Larsen, M.; Höß, A. Integration of a RTT Prediction into a Multi-path Communication Gateway. Computer Safety, Reliability, and Security. SAFECOMP 2021 Workshops; Habli, I., Sujan, M., Gerasimou, S., Schoitsch, E., Bitsch, F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: York, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousaridas, A.; Manjunath, R.P.; Perdomo, J.; Zhou, C.; Zielinski, E.; Schmitz, S.; Pfadler, A. QoS Prediction for 5G Connected and Automated Driving. IEEE Communications Magazine 2021, 59, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmpounakis, S.; Maroulis, N.; Koursioumpas, N.; Kousaridas, A.; Kalamari, A.; Kontopoulos, P.; Alonistioti, N. AI-driven, QoS prediction for V2X communications in beyond 5G systems. Computer Networks 2022, 217, 109341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, E.N.; Fernandes, K.; Andrade, F.; Silva, P.; Campos, R.; Ricardo, M. A Machine Learning Based Quality of Service Estimator for Aerial Wireless Networks. 2019 International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Computing, Networking and Communications (WiMob), 2019, pp. 1–6. 2: ISSN, 2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchar, J.; Drumm, A.C. The traffic alert and collision avoidance system. Lincoln laboratory journal 2007, 16, 277. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, T.; Spencer, N.A. Development and operation of the traffic alert and collision avoidance system (TCAS). Proceedings of the IEEE 1989, 77, 1735–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Saripalli, S. Sense and avoid for unmanned aerial vehicles using ADS-B. 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2015, pp. 6402–6407.

- Mohammadkarimi, M.; Rajan, R.T. Cooperative Sense and Avoid for UAVs using Secondary Radar. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.03046, arXiv:2306.03046 2023.

- Schäfer, M.; Strohmeier, M.; Lenders, V.; Martinovic, I.; Wilhelm, M. Bringing up OpenSky: A large-scale ADS-B sensor network for research. IPSN-14 Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Information Processing in Sensor Networks. IEEE, 2014, pp. 83–94.

- Schafer, M.; Strohmeier, M.; Smith, M.; Fuchs, M.; Pinheiro, R.; Lenders, V.; Martinovic, I. OpenSky report 2016: Facts and figures on SSR mode S and ADS-B usage. 2016 IEEE/AIAA 35th Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC). IEEE, 2016, pp. 1–9.

- Baek, K.; Bang, H. ADS-B based trajectory prediction and conflict detection for air traffic management. International Journal Aeronautical and Space Sciences 2012, 13, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sun, J.; Rajan, R.T. Aircraft Trajectory Prediction using ADS-B Data. Pre-Proceedings of the 2022 Symposium on Information Theory and Signal Processing in the Benelux, 2022, p. 113.

- Shi, Z.; Xu, M.; Pan, Q.; Yan, B.; Zhang, H. LSTM-based flight trajectory prediction. 2018 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN). IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–8.

- Zhang, Y.; Jia, Z.; Dong, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Q. Recurrent LSTM-based UAV Trajectory Prediction with ADS-B Information. GLOBECOM 2022-2022 IEEE Global Communications Conference. IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–6.

- Olfati-Saber, R. Distributed Kalman filtering for sensor networks. 2007 46th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control. IEEE, 2007, pp. 5492–5498.

- Lian, B.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Lewis, F.L.; Chai, T. Distributed Kalman consensus filter for estimation with moving targets. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2020, 52, 5242–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D. Distributed particle filter for target tracking. Proceedings 2007 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. IEEE, 2007, pp. 3856–3861.

- Tang, R.; Riemens, E.; Rajan, R.T. Distributed Particle Filter Based on Particle Exchanges. 2023 IEEE Aerospace Conference, 2023, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Li, C.; Zhu, L. A comprehensive survey on blind source separation for wireless adaptive processing: Principles, perspectives, challenges and new research directions. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 66685–66708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadkarimi, M.; Leus, G.; Rajan, R.T. Joint Ranging and Phase Offset Estimation for Multiple Drones using ADS-B Signatures. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology. [CrossRef]

- Politi, E.; Garyfallou, A.; Panagiotopoulos, I.; Varlamis, I.; Dimitrakopoulos, G. Path planning and landing for unmanned aerial vehicles using ai. Proceedings of the Future Technologies Conference. Springer, 2022, pp. 343–357.

- Tang, G.; Tang, C.; Claramunt, C.; Hu, X.; Zhou, P. Geometric A-star algorithm: an improved A-star algorithm for AGV path planning in a port environment. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 59196–59210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac, T.T.; Copot, C.; Tran, D.T.; De Keyser, R. A hierarchical global path planning approach for mobile robots based on multi-objective particle swarm optimization. Applied Soft Computing 2017, 59, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, M.; Mohammadkarimi, M.; Rajan, R.T. Artificial Potential Field-Based Path Planning for Cluttered Environments. 2023 IEEE Aerospace Conference, 2023, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.b.; Luo, G.c.; Mei, Y.s.; Yu, J.q.; Su, X.l. UAV path planning using artificial potential field method updated by optimal control theory. International Journal of Systems Science 2016, 47, 1407–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, A.T.; Koubaa, A.; Ali Mohamed, N.; Ibrahim, H.A.; Ibrahim, Z.F.; Kazim, M.; Ammar, A.; Benjdira, B.; Khamis, A.M.; Hameed, I.A.; others. Drone deep reinforcement learning: A review. Electronics 2021, 10, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Nouacer, R.; Corradi, F.; Ouhammou, Y.; Villar, E.; Tieri, C.; Castiñeira, R. Key technologies for safe and autonomous drones. Microprocessors and Microsystems 2021, 87, 104348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Haddad, C.; Chaniotakis, E.; Straubinger, A.; Plötner, K.; Antoniou, C. Factors affecting the adoption and use of urban air mobility. Transportation research part A: policy and practice 2020, 132, 696–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).