1. Introduction

The RPAS industry has experienced significant growth, with the global drone market projected to reach

$42.8 billion by 2025, driven by technological advancements such as real-time decision-making, and flight endurance; cost reductions[

1,

2]. These systems have demonstrated versatility across different industries, such as military, civil, and commercial applications due to their ability to access hazardous or inaccessible areas. In scientific contexts, RPAS a practical, cost-effective, and robust alternative for data collection compared to traditional methods, with the advantage of being minimally invasive when used in natural environments [

3]. Meroever, drones can perform these tasks autonomously or semi-autonomously with minimal human intervention [

4], demonstrating high efficiency in carrying out repetitive, complex, and precise operations.

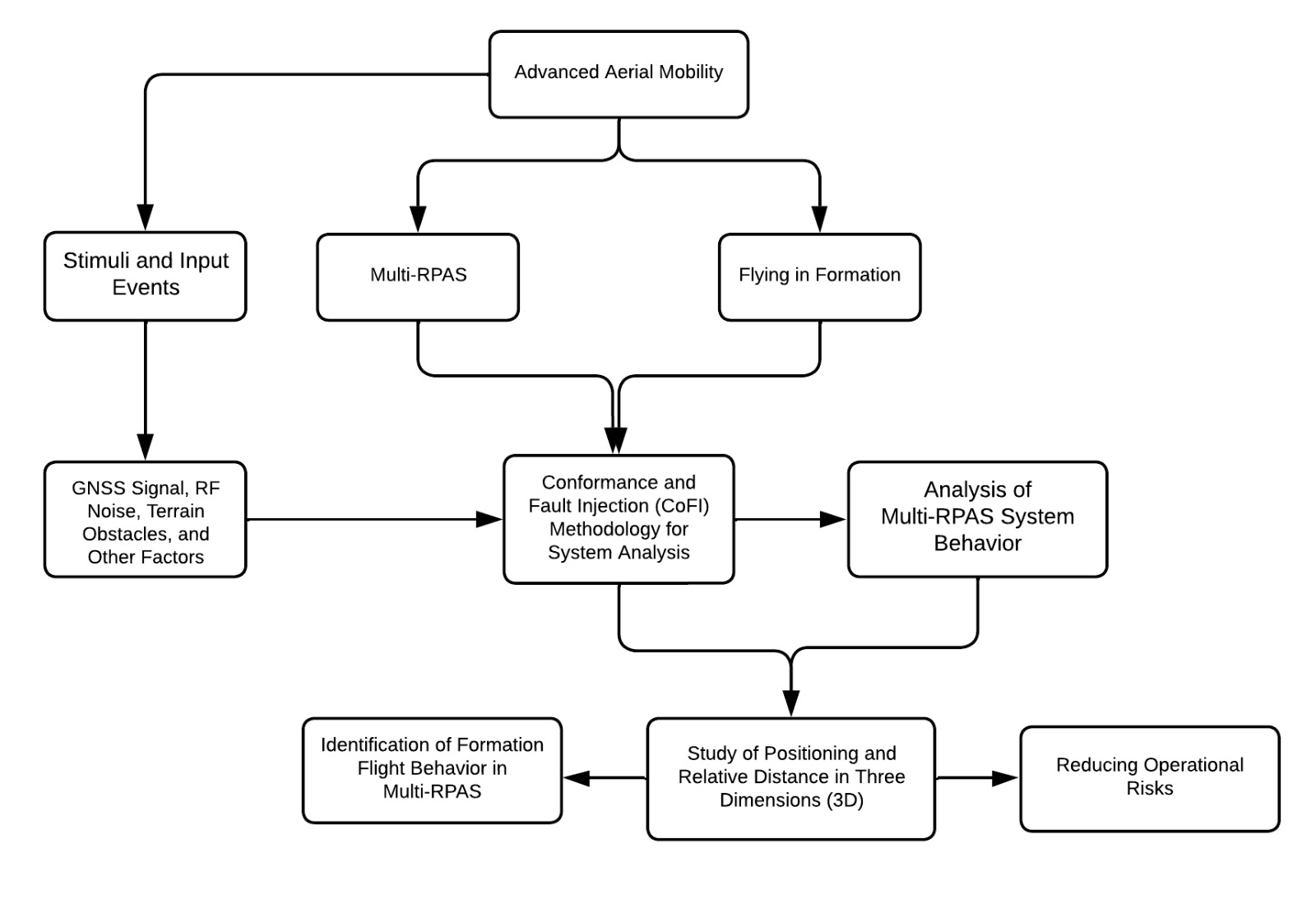

This study introduces the application of the CoFI methodology to Multi-RPAS formations, addressing unique challenges such as GNSS dependency, communication reliability, and energy constraints. By focusing on fault injection and recovery within this specific operational context, the research bridges a critical gap in the existing literature, contributing to the advancement of fault-tolerant Multi-RPAS systems.

However, according to Roldan et al. in 2015 [

5], tasks such as structure inspections, environmental monitoring, recognition tasks, surveillance, and cargo transportation can be complex for a single RPAS to execute. In military applications, for instance, single RPAS are limited by their visual range, combat range, and strike radius. The failure of a single RPAS during a mission can critically compromise the entire operational plan [

6]. In contrast, multi-RPAS systems, where each Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) in the system executes an independent task while collaborating with others [

7]; offer significant advantages, including enhanced efficiency and reduced mission duration, which depends on the number of UAVs utilized [

5,

8,

9].

The use of multi-RPAS has progressively increased, driven primarily to enhancing efficiency and reducing cost. Advancement that are attributed to hardware standardization, which has significantly decreased the prices of critical components such as batteries, propellers, motors, cameras, and other essential elements [

8]. Additionally, their semiautonomous operations eliminates the need for a pilot, reducing man-hours and enhancing cost-effectiveness [

10,

11]. Multi-RPAS systems also contribute to lowering operational costs and mitigating human risk during hazardous operations, such as military or research missions. Furtheremore, they minimize noise disturbance, enable more frequent data collection, and, in certain scenarios, provide higher-quality and larger volumes of data [

11,

12].

Despite these adventages, operating multi-RPAS formations presents several challenges including security breaches, privacy violations, firmware vulnerabilities in newly vehicles, control instability, high energy consumption, issues with formation control, collision and obstacle avoidance, location recognition, and the increased operational complexity associated with the number of vehicles involved [

6,

13,

14,

15]. Moreover, the affordability of these systems makes them susceptible to exploitation for illegal activities, such as transporting payloads—including weapons, explosives, and drugs—to difficult-to-reach locations undetected[

16].

A particular critical challenge lies in localization, according to Mijac et al. in 2022 [

17], the development and executions of missions involving multi-RPAS systems face significant localization challenge, primarily from the reliance on Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) which is prone to errors of up to 2 meters [

18], these errors complicate vehicle coordination, increasing the risk of collisions between vehicles [

17]. Additionally, the impact of RF noise (Radio Frequency noise) must be addressed, as it can disrupt communication between the ground segment and the aerial segment [

19]. Finally, the energy consumption required for constant position correction and maneuvers is an additional challenge to consider [

17,

20,

21].

This research aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the behavior of multiple RPAS operating in formation. The study specifically examines the dynamics of positioning and relative distance in three-dimensional space (3D) among two RPAS. To achieve this, it identifies detailed set of operational requirements, delineates the system’s operating states, and systematically addresses potential scenarios that may arise during formation flight, including nominal operations and anomalous conditions.

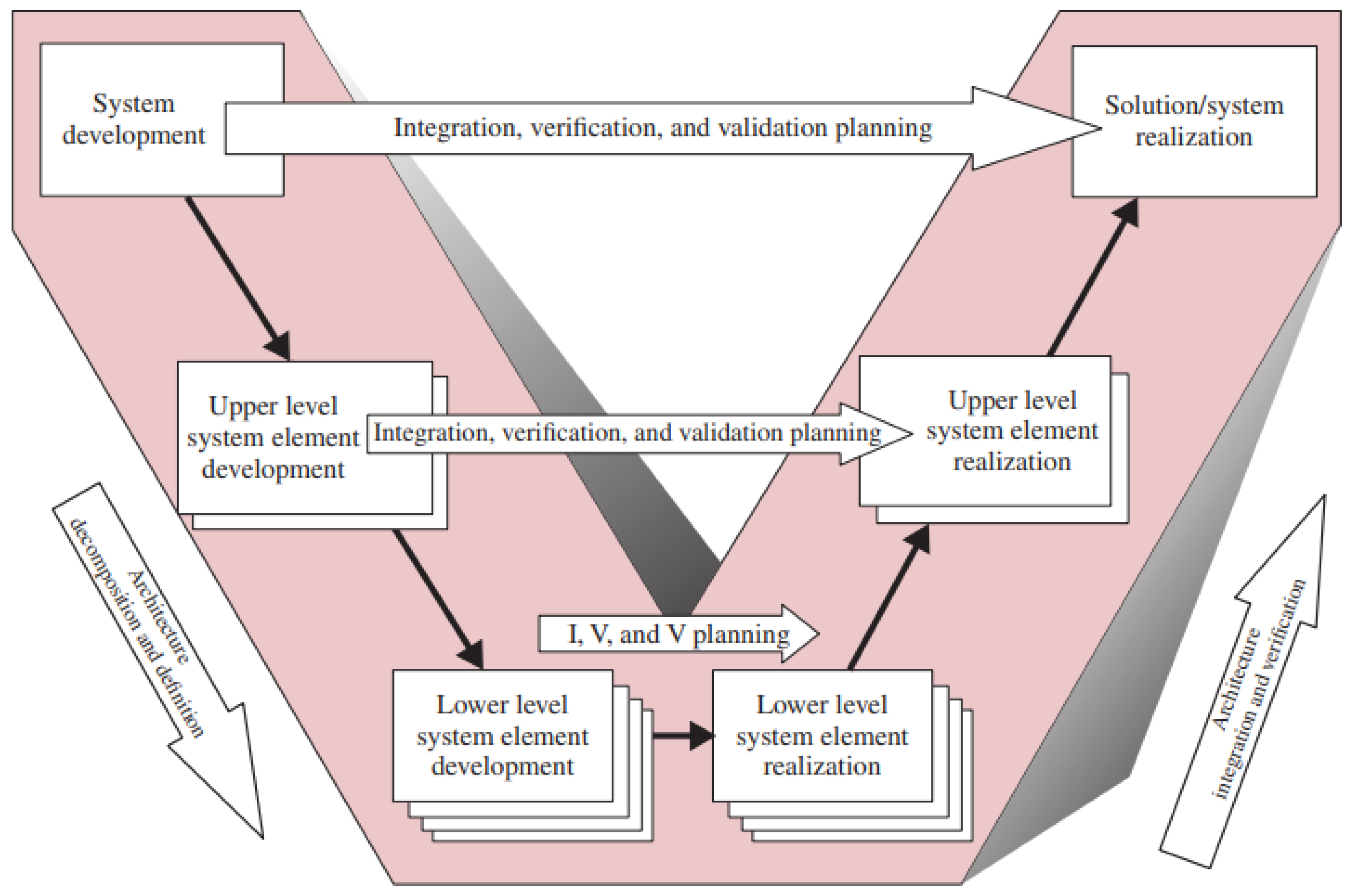

To gain a comprehensive understanding of multiple RPAS flying in formation, this study employs the "Conformance and Fault Injection" (CoFI) methodology. The CoFI methodology is a model-based approach that guides the user towards a thorough understanding of the system and allows for the creation of a set of finite state machines representing the system's behavior under study [

22]. It is also important to note that this research is traditionally applied during the system verification and validation (V&V) phase, in line with the "V" model used in systems engineering design for the development of complex systems. However, planning for the system's integration, verification, and validation should be considered from the beginning of its development, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

According to Ai et al. in 2022 [

24], it is essential to incorporate fault-tolerant control mechanisms to maintain operational integrity under anomalous conditions. Therefore, the objective of this research is to present models and requirements for the behavior of a formation flight system composed of at least two RPAS flying in formation. This will be achieved through the CoFI methodology, which facilitates fault injection into the operation and the prediction of behavior in anomalous situations.

The primary objective of this research is to systematically identify the inherent weaknesses in the deployment of multi-RPAS systems and to propose targeted improvements and potential solutions aimed at enhancing their safety and autonomy. By addressing these critical challenges, the study aims to advance autonomy, improve the planning, verification, and validation of RPAS formation flight behavior with heightened precision and mitigating the associated operational risks [

24].

2. Materials and Methods

Various Fault-Tolerant Control (FTC) methods have been proposed for RPAS systems. Generally, FTC can be classified into passive and active approaches and further categorized as model-based and data-driven methods. According to Peng and Cheng [

25], model-based methods are more economical and efficient as they do not require the processing of extensive datasets [

25].

The CoFI methodology is a model-based approach that represents the behavior of the system under study [

26]. CoFI relies on a testing process that allows for the derivation of fault situations and test cases. The system to be modelled is viewed as a System Under Test (SUT) [

22].

Additionally, this approach considers the events or stimuli that occur in the environment and the desired actions or responses triggered by the corresponding events or stimuli. The SUT is modelled using Mealy machines, with the system's behavior represented in states. State changes are depicted by transitions that encompass the inputs and outputs of the SUT interfaces [

27]. CoFI methodology forms the cornerstone of this study, offering a systematic, model-based approach for the verification and validation of complex systems. In this research, CoFI has been employed to analyse the behaviour of Multi-RPAS flying in formation under both nominal and fault conditions. The methodology operates through three principal stages: identifying the context and interface of the SUT, modelling, and generating test cases [

22].

This work focuses on decomposing the system to model it effectively. Therefore, the operational context of the SUT is identified based on the airworthiness recommendations for RPAS from civil aviation authorities, leading to the modelling and generation of test cases through a simplified set of CoFI steps that cover the system's behavior [

4]

These steps are organized as follows:

-

Context and Interface Identification: This initial phase delineates the operational boundaries and interactions of the system under test (SUT), encompassing the operational environment, functional requirements, and potential fault scenarios. For Multi-RPAS formations, the operational environment considers real-world challenges such as reliance on GNSS, radio frequency interference, and energy consumption constraints. Functional requirements are defined to include critical capabilities such as collision avoidance, formation maintenance, and energy-efficient operation. Additionally, potential fault scenarios, including temporary communication failures, GPS inaccuracies, and hardware malfunctions, are systematically incorporated into the test design to ensure comprehensive evaluation and robust system performance.

- 1.1.

Identify the concept of operation.

- 1.2.

Establish main functional requirements.

- 1.3.

Identify the services that the SUT must perform for the user.

- 1.4.

Identify the physical environment where the SUT operates, as well as the type of communication between the SUT and external entities.

- 1.5.

Identify faults that may occur in the hardware that the SUT must detect and handle.

-

Modelling: The behaviour of the system is represented using Mealy machines, which formalise the states, transitions, and associated inputs/outputs, providing a robust framework for predicting system responses to diverse conditions. State diagrams visually depict the transitions between nominal operations, fault conditions, and recovery states, ensuring clear traceability between faults, system responses, and predefined requirements. Furthermore, the models are tailored to include critical scenarios, such as GNSS disruptions, inter-RPAS communication failures, and environmental challenges, to comprehensively evaluate the system's performance under both standard and adverse conditions.

- 2.1.

Identify event or stimulus inputs.

- 2.2.

Identify the actions or responses of the SUT.

- 2.3.

Define the behavior of the SUT using a state diagram for four classes of models.

-

Test Case Generation: Evaluate the system’s behaviour across a range of scenarios, including nominal operations, fault tolerance, and edge cases. Nominal operations focus on routine mission execution under ideal conditions, while fault tolerance examines recovery strategies for addressing disruptions such as reconfiguration during RPAS failures. Edge cases explore uncommon but critical scenarios, including simultaneous GNSS errors and energy shortages. These test cases are assessed using key metrics such as system stability, recovery time, and energy efficiency to ensure comprehensive performance evaluation.

- 3.1.

Nominal operation.

- 3.2.

Specific operational exceptions.

- 3.3.

Stealth paths or untimely inputs.

- 3.4.

Fault tolerance.

Finally, the models and test cases are analyzed to verify the behavior of the formation flight.

To validate the CoFI methodology, a simulation environment was developed to emulate the operational conditions of two RPAS flying in formation. This simulated application was designed to evaluate both nominal performance and responses to fault conditions, focusing on several key objectives: assessing the stability of formation flight under routine conditions, evaluating the system’s ability to detect, respond to, and recover from faults, and measuring the impact of recovery processes on energy consumption, positioning accuracy, and communication reliability.

The simulation accounted for a variety of environmental conditions, including urban interference characterized by high signal noise and obstacles, adverse weather conditions such as turbulence and strong winds, and remote operations where communication infrastructure is limited. Additionally, the simulation incorporated critical fault scenarios, including temporary GNSS signal loss resulting in positioning inaccuracies, communication disruptions between RPAS and the ground control station, and energy depletion during prolonged missions, necessitating emergency maneuvers.

System performance was evaluated using three principal metrics: recovery time, which measures the duration required to restore nominal operations; energy efficiency, which examines variations in energy consumption during fault recovery; and mission continuity, which assesses the system’s ability to complete mission objectives despite encountered faults. The results demonstrated that the CoFI methodology enables robust fault detection and recovery, ensuring the safe and efficient operation of Multi-RPAS formations even under challenging conditions.

2.1. Comparison with Other Fault Injection Methodologies

To contextualise the findings, a comparison was made between the CoFI methodology and other fault injection methodologies, such as Monte Carlo-based testing and neural network models. This analysis highlights potential advantages of CoFI in the context of Multi-RPAS formations. Regarding efficiency, CoFI leverages state-based modelling, which can reduce computational complexity compared to the extensive randomised sampling often associated with Monte Carlo simulations. Its systematic approach also facilitates the generation of targeted test cases, including edge scenarios. In terms of adaptability, while neural network models are effective in recognising patterns, they require substantial datasets and may be less flexible when addressing novel fault scenarios. CoFI’s structured modelling could allow adaptation to dynamic operational environments. As can be seen in

Table 1, the comparison also identifies areas where combining methodologies may provide complementary strengths, potentially leading to more robust fault diagnosis. In terms of precision and predictability, CoFI offers a formal framework for identifying faults and planning recovery strategies, which can support safety-critical systems. Neural networks, however, may present challenges in terms of interpretability, potentially complicating real-time fault analysis. Overall, this comparative analysis suggests that CoFI may enhance fault tolerance and operational reliability in Multi-RPAS systems, particularly when integrated with other methodologies to address complex operational demands.

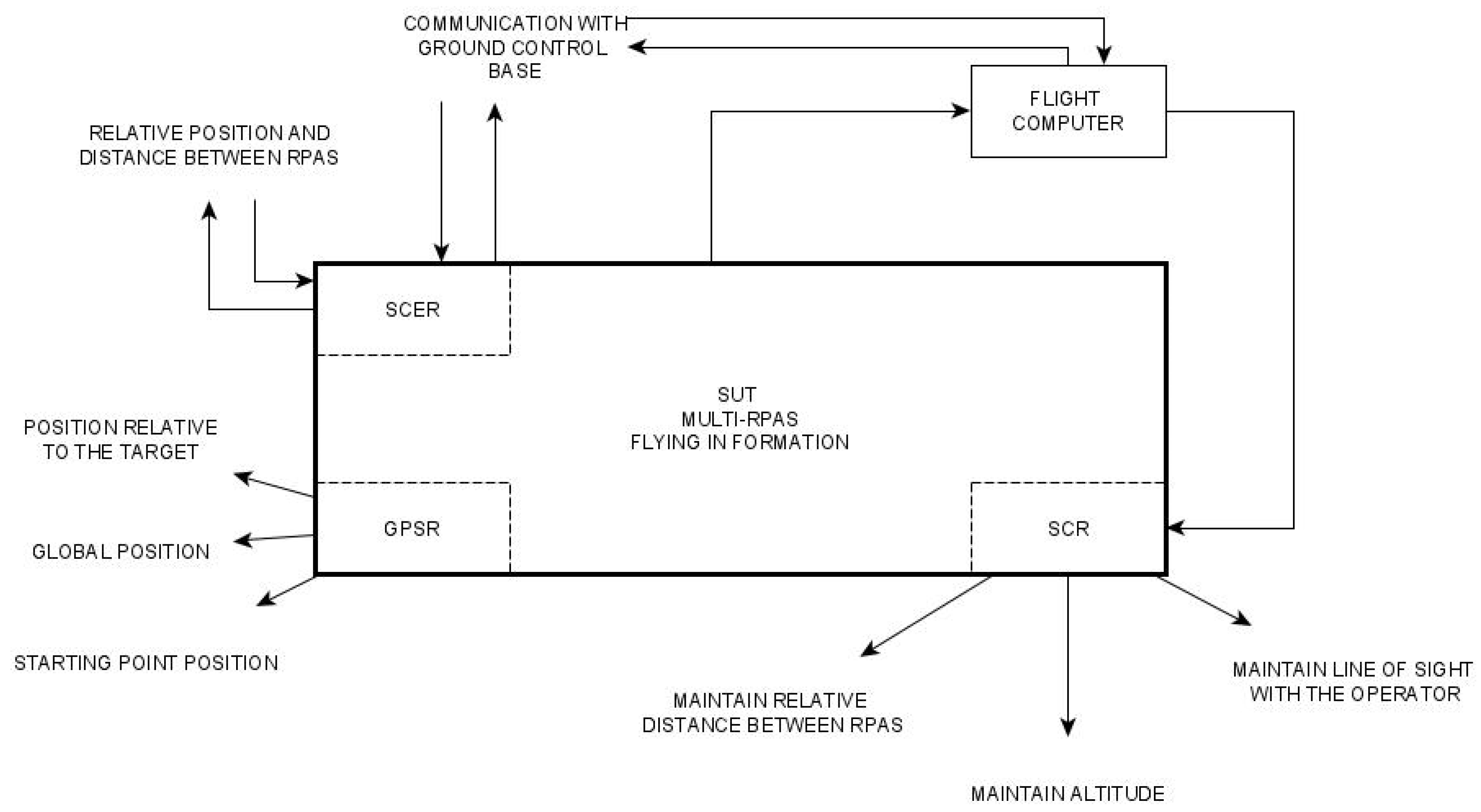

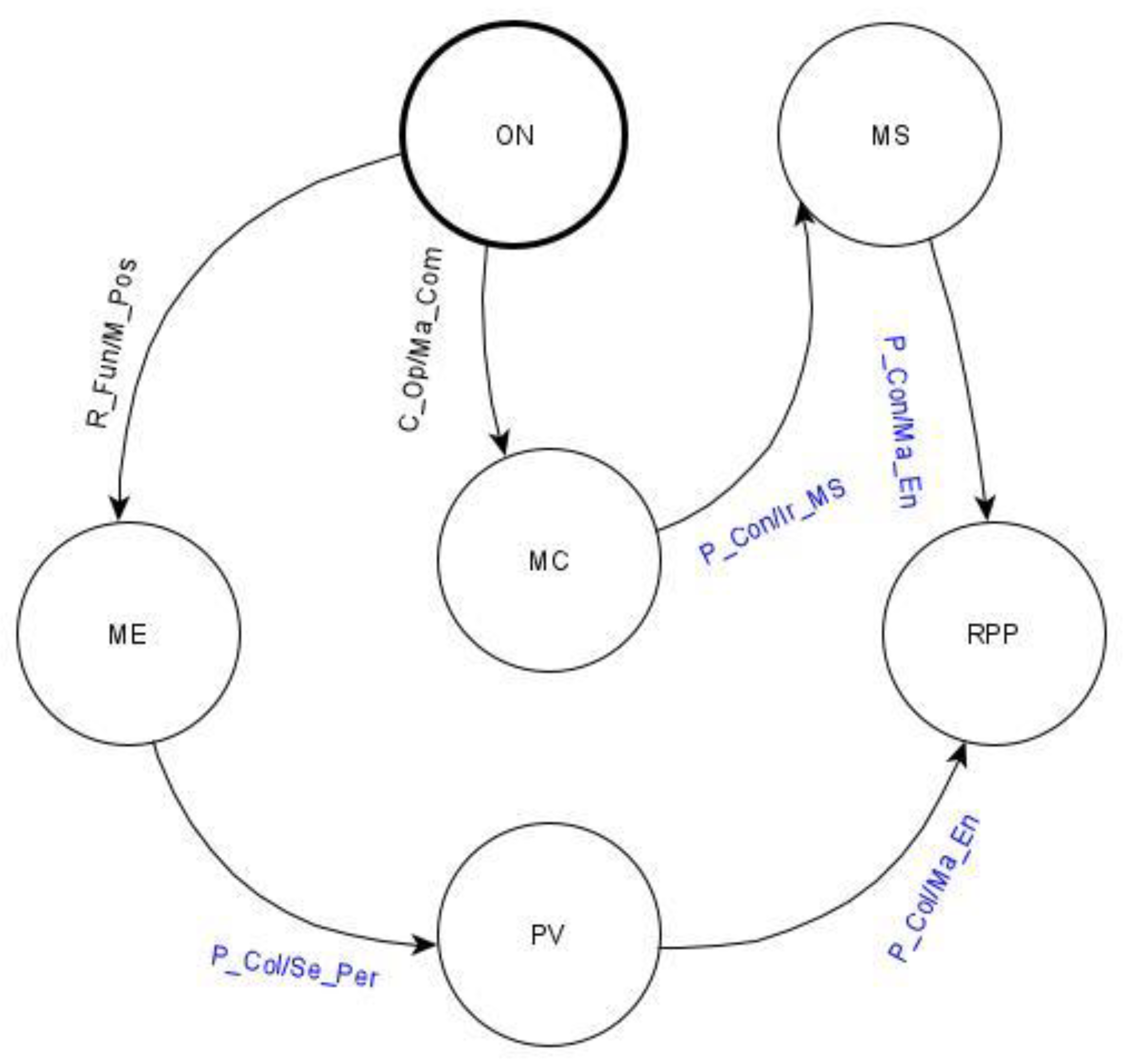

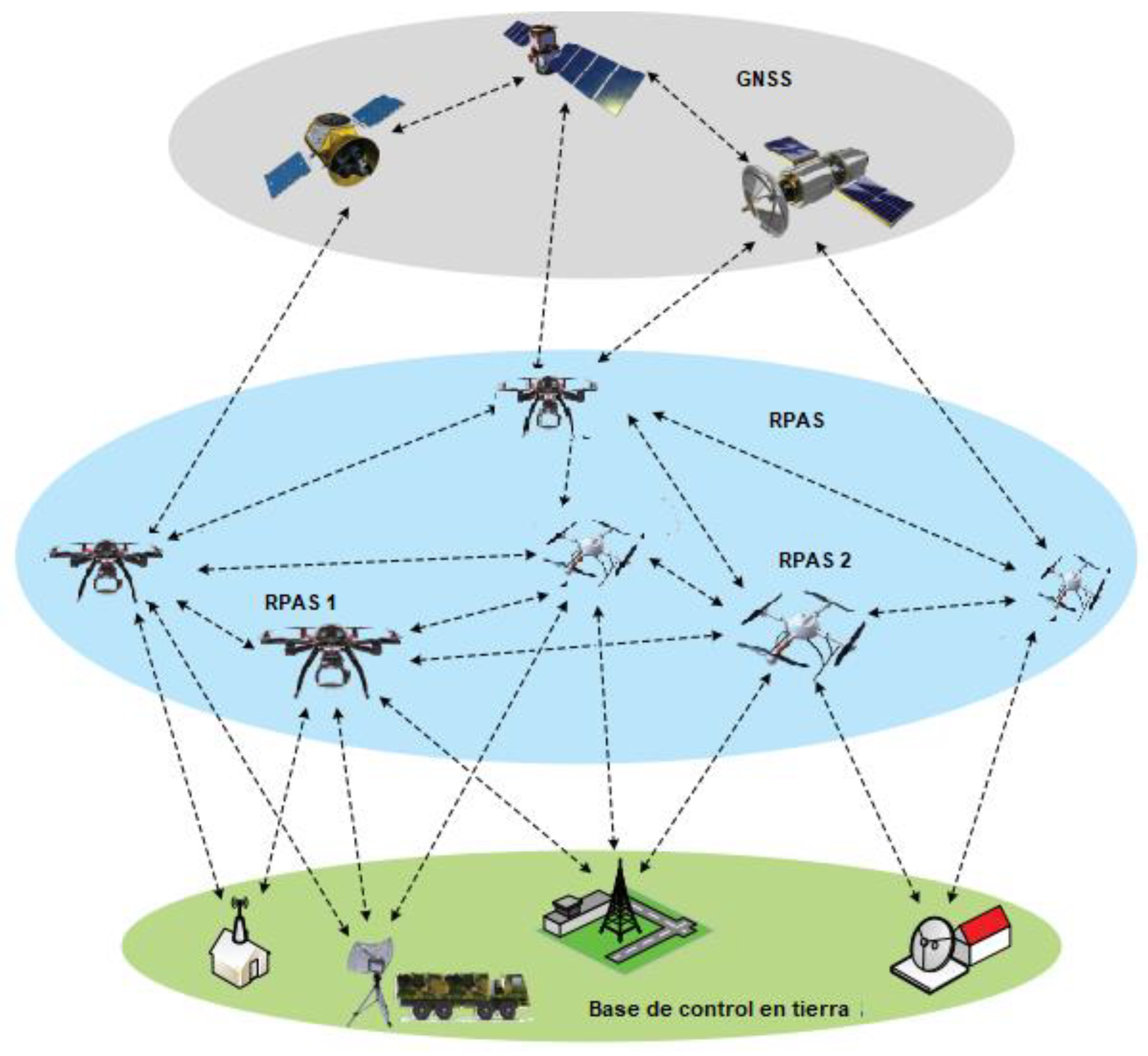

2.2. Concept of Operations (ConOps) for Multi-RPAS Flying in Formation

This research aims to explore the application of the CoFI methodology to analyze the nominal operation and various situations that may arise in Multi-RPAS flying in formation. Initially, the study focuses on the operation of two RPAS flying in formation, with positioning facilitated by GNSS and communication maintained between the RPAS and the ground control base, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

Additionally, is necessary to take into account the airworthiness limitations of RPAS proposed by the local Civil Aviation Authorities (CAA).

2.3. Expansion of test cases

To perform a comprehensive evaluation of the system, a series of test cases was designed to encompass both routine operational conditions and exceptional scenarios. These test cases simulate operations in urban environments with significant signal interference, flights in remote areas lacking communication infrastructure, and operations under adverse weather conditions. The inclusion of these scenarios facilitates a thorough analysis of the system's behavior across diverse contexts, thereby underscoring its adaptability and operational reliability under varying conditions.

To further strengthen the validation of the CoFI methodology, additional test cases were developed and systematically evaluated across a range of environmental and fault scenarios. These scenarios include:

Nominal Operations: Routine mission execution under ideal conditions, serving as a baseline for performance evaluation.

Fault Tolerance: Scenarios such as temporary GNSS signal loss, communication disruptions, and energy depletion, testing the system’s ability to detect, respond to, and recover from faults.

Edge Cases: Uncommon but critical situations, including simultaneous GNSS errors and high interference environments, designed to assess the system’s robustness under extreme conditions.

Each test case was analysed using the following key performance metrics:

Recovery Time: The time required for the system to return to nominal operation after encountering a fault.

Energy Efficiency: The impact of fault recovery processes on overall energy consumption.

Mission Continuity: The system’s ability to complete mission objectives despite fault occurrences

2.4. Detailed State Machine Models

The state machine modeling has been expanded by incorporating additional states that present events such as temporary communication loss and the need for formation reconfiguration in the event of an RPAS failure. States such as “Formation Reconfiguration” and “In-flight Energy Recharge” provide the system with greater flexibility, enabling it to adapt in real-time and continue mission objectives safely.

2.5. Validation with Integrated CoFI Simulations in Realistic Environments

To validate the model's effectiveness, simulations have been performed using flight data in realistic environments. These simulations include interference factors such as turbulence, frequency noise, and terrain obstacles, allowing for an evaluation of the system's performance in a controlled setting that replicates real-world conditions. This robust validation ensures that the CoFI methodology can be effectively applied to RPAS formations in complex missions, providing reliable and representative results.

2.6. Formation Flight Requirements

According to Mijac et al. in 2022 [

4], the use of multiple RPAS presents various challenges, including location recognition and the complexity arising from the number of vehicles involved. Additionally, the RF noise generated by the simultaneous operation of multiple RPAS must be taken into account. Moreover, the energy consumption required for the vehicles to maintain their relative positions and the time needed for maneuver management are critical factors that should be considered.

To address these challenges, functional requirements identified in various studies are compiled, primarily considering those established by Mijac et al. in 2022 [

4], and the limitations proposed by various CAAs.

R01. The system shall be operated by a single flight controller.

R02. The system shall allow for a change of flight controller.

R03. The system shall enable communication between RPAS.

R04. The system shall prevent collisions between RPAS.

R05. The system shall be capable of autonomously returning to its point of origin.

R06. The system shall avoid interference with local air traffic operations.

R07. The system shall maintain the maximum permitted speed.

R08. The system shall maintain the maximum permitted altitude.

R09. The system shall remain within the operator's line of sight.

R10. The system shall operate within the airspace zones permitted by the CAA.

R11. The system shall complete the mission with the available stored energy in each RPAS of the formation.

R12. The system shall maintain the relative 3D distance defined by the proposed mission.

These requirements are focused on the system in operation.

2.7. Behavior of the Flight Formation

The context of the Multi-RPAS operation is based on the ConOps of the mission. Therefore, the interfaces of the SUT must be taken into account. Consider the SUT as a black box containing the communication system between RPAS (SCER), the Global Positioning System of the RPAS (GPSR), and the control system of the RPAS (SCR). These are associated with the external elements of the vehicle through information exchange, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

In the SUT, it is necessary to consider the flight computer responsible for processing and organizing the information shared between RPAS and the ground control base.

2.8. List of Events

To present the behavior of the SUT and develop the models, the possible events that can occur in the work environment and cause a change in the state of the SUT are initially defined. The list of events is constructed based on the events occurring in the operational environment observed by the SUT. The event description and the traceability relationship for the requirements are shown in

Table 2.

Each event is identified with an "ID" to differentiate them and represent them in the models.

2.9. List of Actions

Similarly, mnemonics are defined to represent one or several actions (or reactions) that the system will take when an event occurs. The proposed actions are based on the events that have occurred to mitigate their negative consequences. In

Table 3, the traceability column links the requirements and events to the actions to be taken.

Each event and action must respond to the fulfilment of the requirements, moving the formation from one state to another.

The following list describes the states of the formation for its nominal operation.

The proposed states correspond to conventional nominal operating states of a Multi-RPAS flight formation.

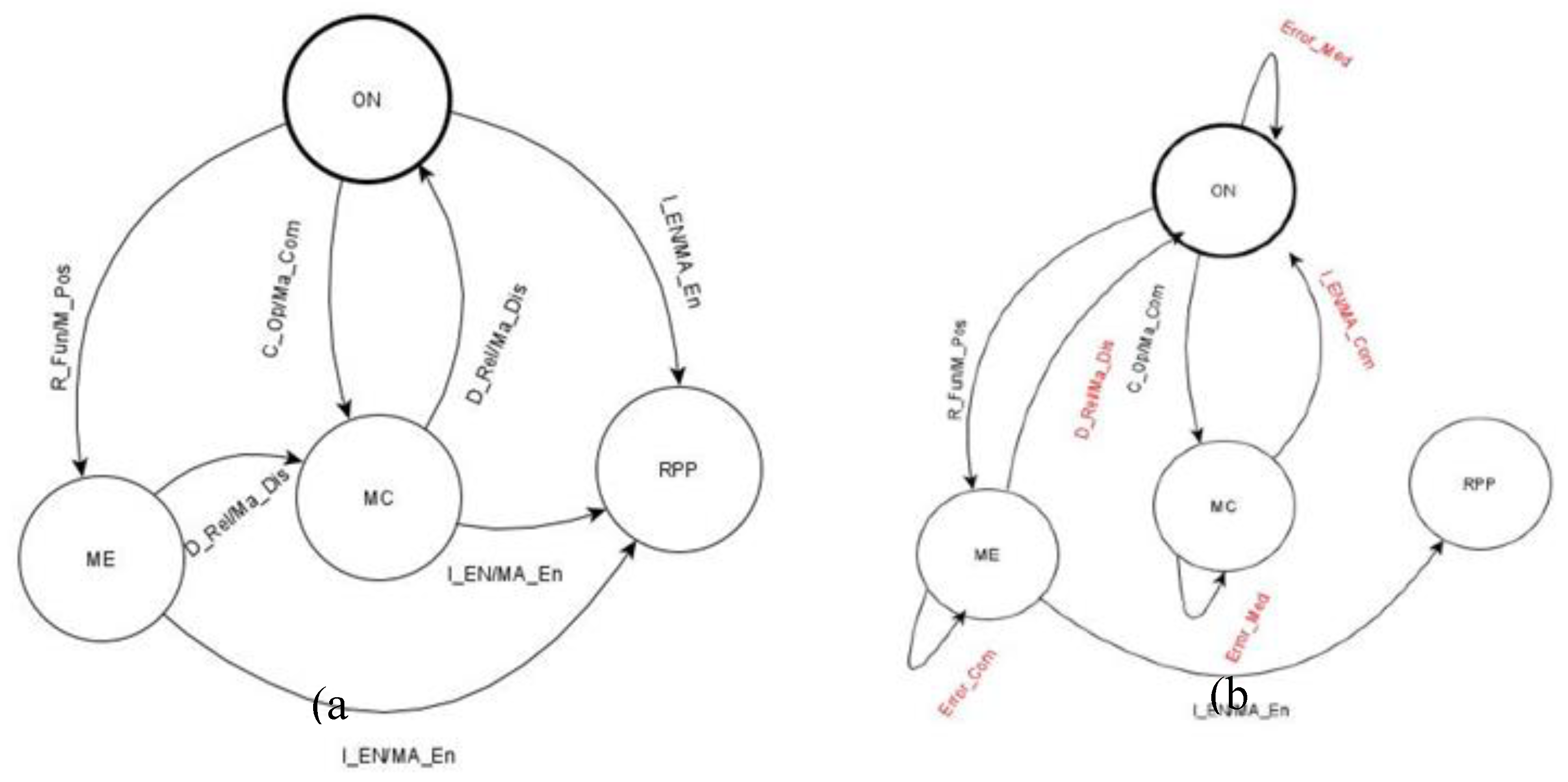

3. State Machine Models

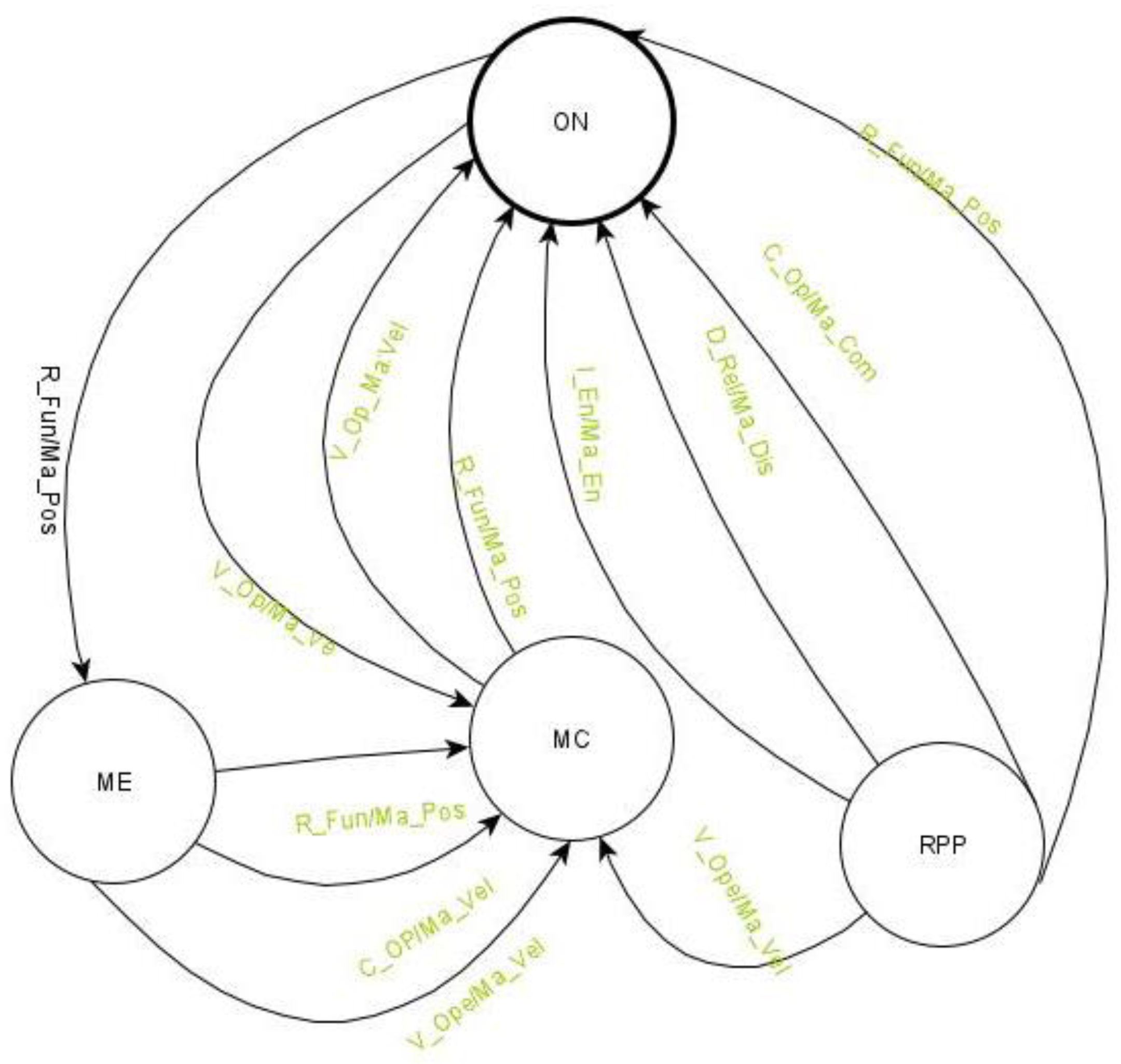

The state machines are constructed based on the events that occur; for each event, there will be an action leading to a specific state.

Figure 4(a) represents the nominal operation of the system, in this case, the formation flight, where it is not constructed with conventional operational events.

Figure 4(b) represents emergency or specific operational states that may occur; in these cases, anomalous events and actions may arise, such as measurement errors (Erro_Med) or calculation errors (Error_Com), which are associated with the vehicles’ flight computer.

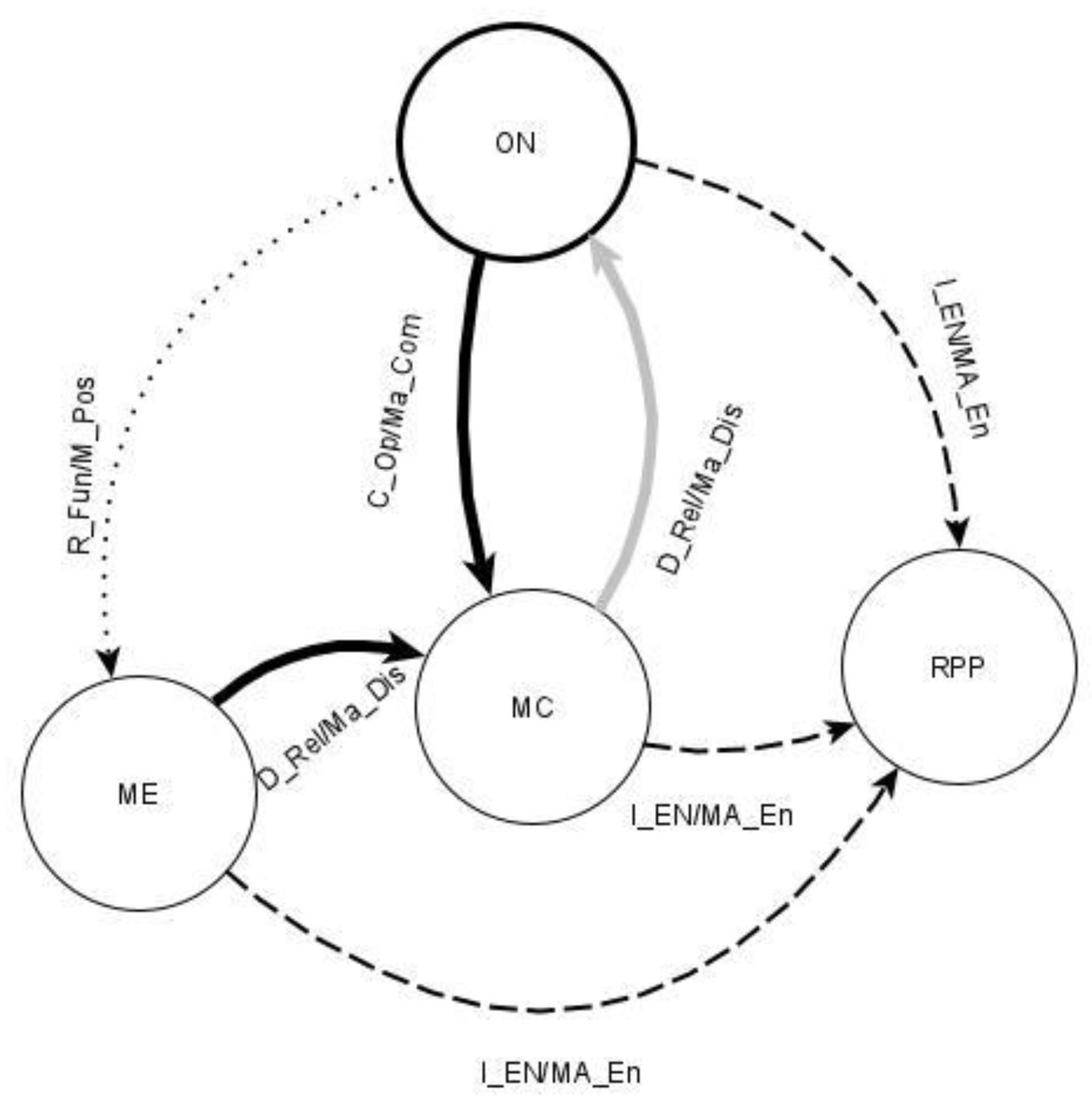

According to the methodology, the following addresses the models of stealth routes or untimely entries through

Table 4, which associates the relationships of nominal and specific routes that were not initially considered.

According to the previous table, 11 stealth routes have been identified, which are represented in

Figure 5.

On the other hand, the creation of a safe mode operation state (MS) is considered for events of loss of control (P_Con) with safe mode actions (Ir_MS) and a vehicle loss state (PV) for collision events (P_Col) with safety actions due to loss (Se_Per) of the formation, as shown in

Figure 6.

4. Behavior Analysis

According to the models analyzed for the different behaviors of a Multi-RPAS flying in formation, it was found that at least 11 possible operational routes are not identified in the nominal operation of the formation, and at least two safety or fault tolerance states are necessary for safe operation.

4.1. Advances Failure Scenarios

To enhance the robustness and analytical depth of RPAS formation behavior, additional failure scenarios have been modeled, including simultaneous GPS signal loss, inter-RPAS communication delays, and control system malfunctions. These scenarios were systematically examined with respect to recovery time, post-failure stability, and operational continuity. The ability of the system to transition into fault tolerance states, such as "Formation Reconfiguration" or "Safe Mode," was a key focus, demonstrating its capacity to maintain mission objectives under adverse conditions.

Analysis revealed that over 80% of the fault recovery routes resulted in transitions to corrective maneuvers (MC) or restoration of nominal operations (ON). Returning to the starting point (RPP) was deemed necessary only under specific anomalous conditions where safety was compromised.

Figure 7 illustrates the state transitions during nominal and fault-tolerant operations, highlighting the flexibility of the CoFI-based approach.

When encountering the event of going out of the functional range (R_Fun), it takes the action of maintaining position (“Ma_Pos”) to transition from the ON state to the ME state (indicated by the dotted line). Subsequently, if the event of losing relative distance (“D_Rel”) occurs, it must perform the action of maintaining distance (“Ma_Dis”) to transition from the ME state to the MC state (represented by the black line). Additionally, there is the possibility of losing communication with the operator (“C_Op”), and through the action of maintaining communication (“Ma_Com”), it transitions from the ON state to the MC state to perform correction maneuvers and, upon regaining control, returns to nominal operation by correcting the relative distance between vehicles (“D_Rel”) and maintaining distance (“Ma_Dis”) (depicted by the grey line).

In the event of encountering the indication of low available energy (“I_En”), the decision would be to maintain constant available energy consumption (“Ma_En”) to transition from any state to the RPP state (represented by dotted lines) for returning to the starting point.

4.2. Evaluation of Impact on Energy Performance Comparison

Energy consumption remains a pivotal metric for evaluating RPAS operational efficiency, particularly during fault recovery maneuvers. This study conducted an in-depth analysis of energy usage under various fault conditions, such as reconfiguration due to GNSS signal degradation or recovery from communication losses. Fault recovery maneuvers increased energy consumption by up to 18% during prolonged missions, underscoring the importance of energy-efficient recovery strategies.

The analysis further revealed that optimized recovery protocols implemented through the CoFI methodology reduced energy consumption by approximately 10% compared to unoptimized approaches. This optimization ensures the RPAS can sustain mission continuity without compromising energy reserves, even under adverse conditions.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the Multi-RPAS flying in formation is an operational system composed of more than one vehicle. Therefore, the operation of such a system necessitates consideration of both air and ground operation segments, as the vehicles must be operated by at least one operator. This makes the requirements and limitations of such operations complex, necessitating the use of tools to identify potential risks.

The CoFi methodology is a tool that should be used from the beginning of the project, as it allows for verifying the functioning of a system and identifying unconsidered behaviors.

The revealed behaviors enable the prediction of anomalous situations, thereby strengthening the operational safety of these vehicles, considering the operational and airworthiness limitations proposed by the AAC.

This research demonstrates the novel application of the CoFI methodology to Multi-RPAS formations, providing a systematic approach for fault injection, detection, and recovery. The methodology’s robustness was validated through diverse test cases, highlighting its adaptability and precision in handling complex fault scenarios. Future work will explore hybrid approaches, integrating CoFI with data-driven methods to further enhance fault-tolerant capabilities and operational reliability.

5.1. Recommendation for Operational Implementation

Based on the results obtained, it is recommended to implement redundant communications systems to mitigate risks associated with signal loss between RPAS. Additionally, integrating preprogrammed emergency maneuvers is suggested to allow each RPAS to automatically adjust its position or return to a safe point in case of failure. These recommendations contribute to enhancing the safety and reliability of the system in real-world operations.

5.2. Analysis of Limitations and Improvement Opportunities

The study has certain limitations, including the use of only two RPAS and the reliance on GNSS for navigation. Furthermore, the use of a centralized controller limits the scalability of the system for formations with a larger number of RPAS. These limitations suggest the need for future research exploring decentralized architectures and alternative navigation systems that could enhance the resilience and flexibility of formations in more complex operational contexts.

5.3. Future Research Directions

To continue advancing the development of autonomous RPAS formations, it is recommended to explore the use of artificial intelligence for real-time fault management and to investigate GNSS-independent navigation technologies, such as computer vision. These research directions will offer new perspectives for improving system autonomy and safety, enabling its application across a broader range of missions and environments with fewer technological constraints.

6. Recommendations

This research only considered a specific vehicle within the formation and a particular architecture. It is recommended to conduct a detailed analysis for each case, taking into account the number of members in the formation and their operational characteristics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.R. and A.A.; methodology, A.A.; validation, J.O. and P.M. formal analysis, I.R and A.A.; investigation, I.R and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, D.T.; writing—review and editing, I.R.; supervision, I.R.; project administration, I.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research was funded by Fundación Universitaria Los Libertadores, grant number ING-34-24.

Data Availability Statement

The data utilized in this study are accessible upon request from the corresponding author, subject to privacy considerations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- “DRONE INDUSTRY REPORT,” 1 Lattice(erstwhile PGA Labs), pp. 1–73, Jun. 2023.

- A. Couturier and M. A. Akhloufi, “A Review on Deep Learning for UAV Absolute Visual Localization,” Drones, vol. 8, no. 11, p. 622, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Sorrell, F. M. E. Dawlings, C. E. Mackay, and R. H. Clarke, “Routine and Safe Operation of Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems in Areas with High Densities of Flying Birds,” Drones, vol. 7, no. 8, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Ambrosio, E. Martins, N. L. Vijaykumar, and S. V. De Carvalho, “Conformance testing process for space applications software services,” Journal of Aerospace Computing, Information and Communication, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 146–158, Apr. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Juan Jesús Roldán, Jaime del Cerro, and Antonio Barrientos, “A proposal of methodology for multi-UAV mission modeling,” 2015 23rd Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation (MED), pp. 1–7, Jun. 2015.

- Y. Yang, X. Xiong, and Y. Yan, “UAV Formation Trajectory Planning Algorithms: A Review,” Jan. 01, 2023, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- M. M. Shahzad et al., “A Review of Swarm Robotics in a NutShell,” Apr. 01, 2023, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- W. Y. H. Adoni et al., “Intelligent Swarm: Concept, Design and Validation of Self-Organized UAVs Based on Leader–Followers Paradigm for Autonomous Mission Planning,” Drones, vol. 8, no. 10, p. 575, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Fang and A. V. Savkin, “Strategies for Optimized UAV Surveillance in Various Tasks and Scenarios: A Review,” May 01, 2024, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- M. Campion, P. Ranganathan, and S. Faruque, “A Review and Future Directions of UAV Swarm Communication Architectures,” in 2018 IEEE International Conference on Electro/Information Technology (EIT) :, Rochester, May 2018, pp. 0903–0908. [CrossRef]

- M. Álvarez-González, P. Suarez-Bregua, G. J. Pierce, and C. Saavedra, “Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in Marine Mammal Research: A Review of Current Applications and Challenges,” Nov. 01, 2023, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- L. G. Torres, S. L. Nieukirk, L. Lemos, and T. E. Chandler, “Drone up! Quantifying whale behavior from a new perspective improves observational capacity,” Front Mar Sci, vol. 5, no. SEP, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, B. Jiang, Z. Mao, and Y. Ma, “Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Formation Control of Heterogeneous Multi-Agent Systems under Directed Communication Topology,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 16, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Manikandan and R. Sriramulu, “Optimized Path Planning Strategy to Enhance Security under Swarm of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles,” Drones, vol. 6, no. 11, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Bu, Y. Yan, and Y. Yang, “Advancement Challenges in UAV Swarm Formation Control: A Comprehensive Review,” Jul. 01, 2024, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- G. E. M. Abro, S. A. B. M. Zulkifli, R. J. Masood, V. S. Asirvadam, and A. Laouti, “Comprehensive Review of UAV Detection, Security, and Communication Advancements to Prevent Threats,” Oct. 01, 2022, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- M. Mijač, B. Tomaš, and Z. Stapić, “An Architectural Model of a Software Module for Piloting UAV Constellations,” TEM Journal, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 1485–1493, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. Montenbruck, P. Steigenberger, and A. Hauschild, “Multi-GNSS signal-in-space range error assessment – Methodology and results,” Advances in Space Research, vol. 61, no. 12, pp. 3020–3038, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Silva Lorraine and M. Ramarakula, “A Comprehensive Survey on GNSS Interferences and the Application of Neural Networks for Anti-jamming,” 2023, Taylor and Francis Ltd. [CrossRef]

- B. Hou, Z. Yin, X. Jin, Z. Fan, and H. Wang, “MPC-Based Dynamic Trajectory Spoofing for UAVs,” Drones, vol. 8, no. 10, p. 602, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Novák, K. Kováčiková, B. Kandera, and A. N. Sedláčková, “Global Navigation Satellite Systems Signal Vulnerabilities in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Operations: Impact of Affordable Software-Defined Radio,” Drones, vol. 8, no. 3, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. C. Pinheiro, A. Simão, and A. M. Ambrosio, “FSM-based test case generation methods applied to test the communication software on board the ITASAT university satellite: A case study,” Journal of Aerospace Technology and Management, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 447–461, 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. D. Walden, G. J. Roedler, and K. Forsberg, “INCOSE Systems Engineering Handbook Version 4: Updating the Reference for Practitioners,” INCOSE International Symposium, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 678–686, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Ai, J. Song, G. Cai, and K. Zhao, “Active Fault-Tolerant Control for Quadrotor UAV against Sensor Fault Diagnosed by the Auto Sequential Random Forest,” Aerospace, vol. 9, no. 9, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. H. Lien, C. C. Peng, and Y. H. Chen, “Adaptive observer-based fault detection and fault-tolerant control of quadrotors under rotor failure conditions,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 10, no. 10, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. L. J. Ferris, S. C. Cook, and E. Sitnikova, “Design as a Research Methodology for Systems Engineering.”.

- R. P. Pontes, P. C. Véras, A. M. Ambrosio, and E. Villani, “Contributions of model checking and CoFI methodology to the development of space embedded software,” Empir Softw Eng, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 39–68, Feb. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Pengbo Si, F. Richard Yu, Ruizhe Yang, and Yanhua Zhang, “Dynamic Spectrum Management for Heterogeneous UAV Networks with Navigation Data Assistance,” in 2015 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC 2015, Istanbul: 2015 IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC 2015), Dec. 2015, pp. 1078–1083.

- “NASA Systems Engineering Handbook.” [Online]. Available: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20170001761.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).