Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

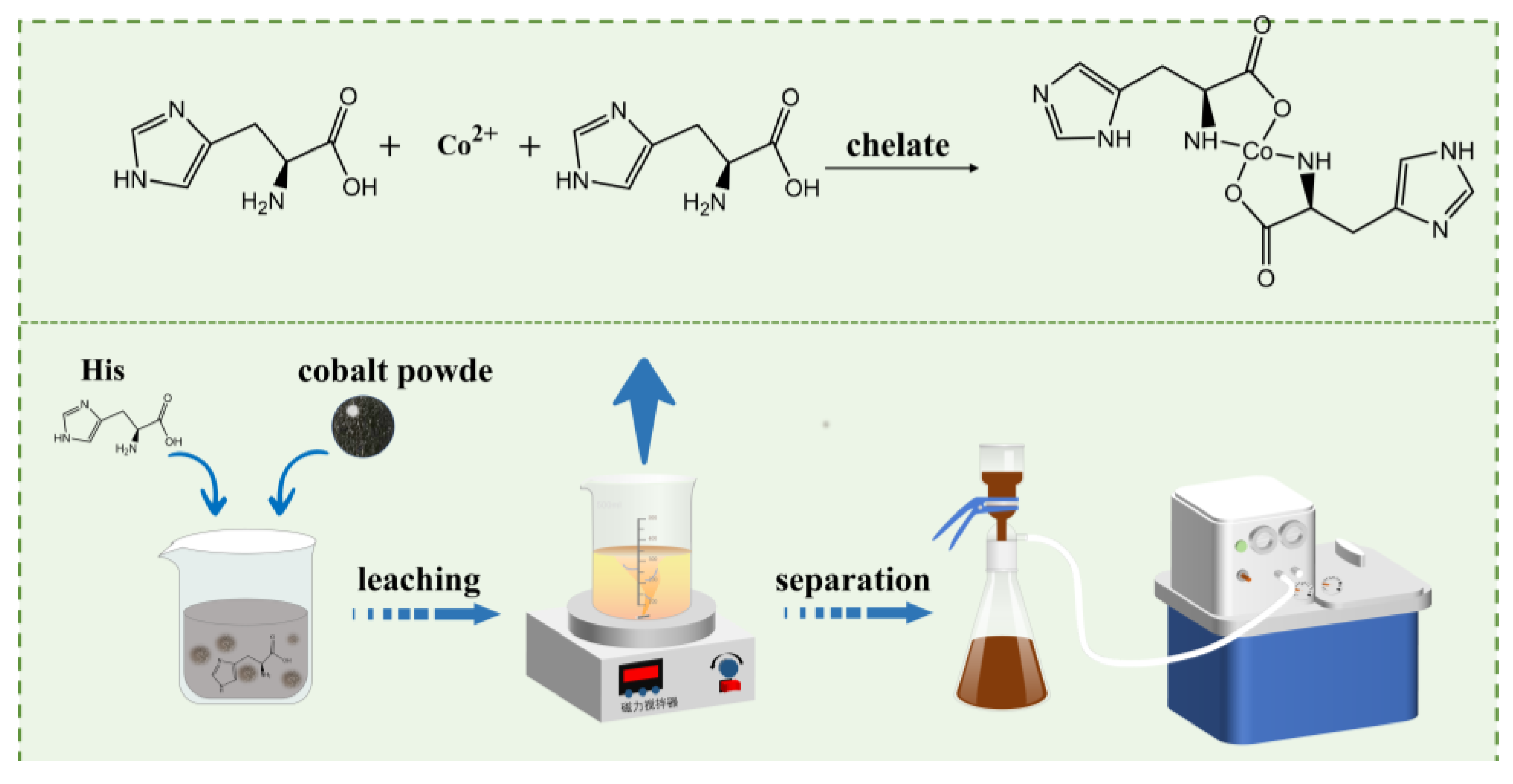

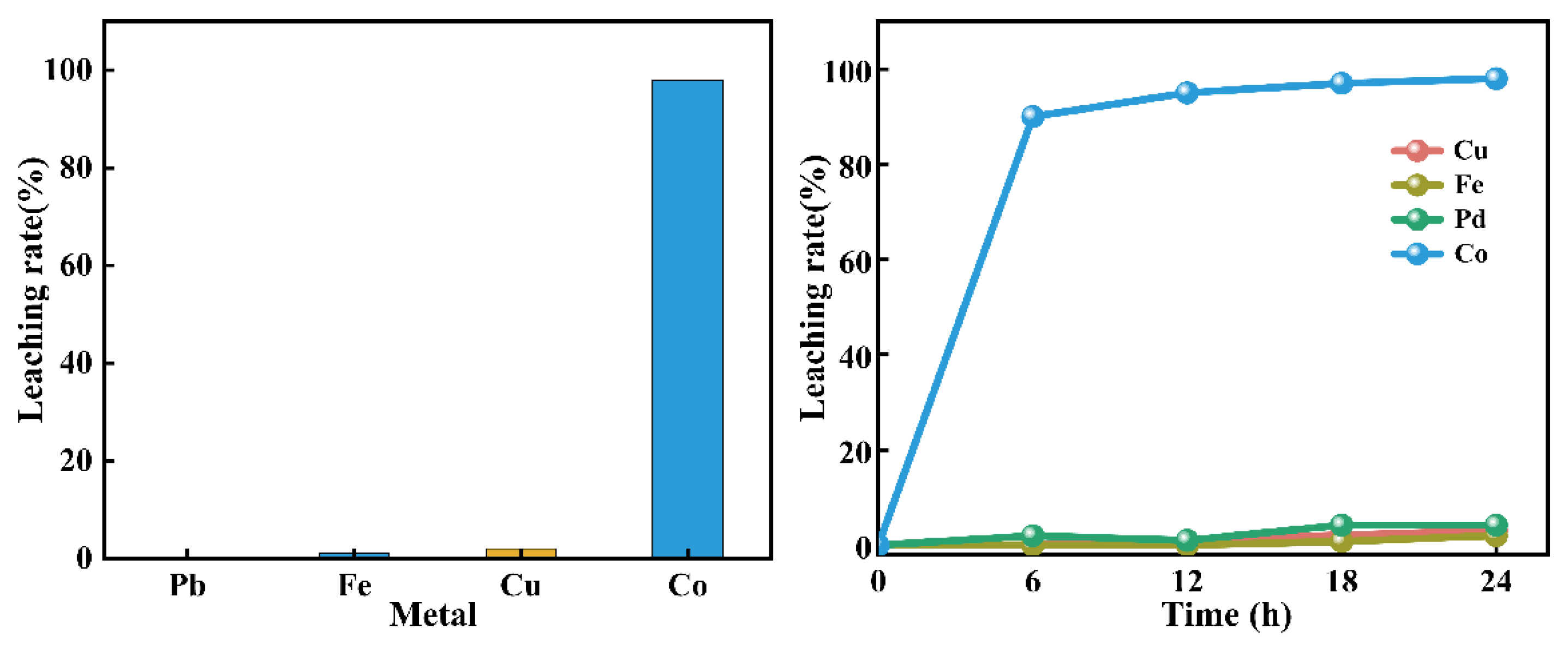

For the extraction of cobalt from cobalt-rich alloy slag, ammonia was considered a lixiviant with limited environmental impact compared to acid lixiviant. However, problems such as large ammonia volatilization loss, toxic vapor emissions, and suboptimal process control were encountered during ammonia leaching. To address these issues, a new method was proposed for recovering cobalt via selective complexing leaching, where an alkaline histidine solution was utilized instead of ammonia. A high cobalt leaching rate of 99% was achieved under the following conditions: a leaching temperature of 35℃, a histidine/cobalt molar ratio of 1.5, a pH range of 6–11, a leaching duration of 6 hours, and a stirring speed of 300 rpm. In the verification test for the leaching of Cu-Co alloy slag with histidine, cobalt was almost entirely leached, while iron, lead, and copper were observed to be difficult to leach. The kinetic analysis of the cobalt leaching process revealed that electrons were donated to Co²⁺ by the amino and COO⁻ groups in histidine during the coordination reaction. This confirmed that a soluble complex, Co(C₆H₉N₃O₂)₂, was formed through coordination between histidine and Co²⁺.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Leaching Experiment

2.3. Analytical Method

3. Results

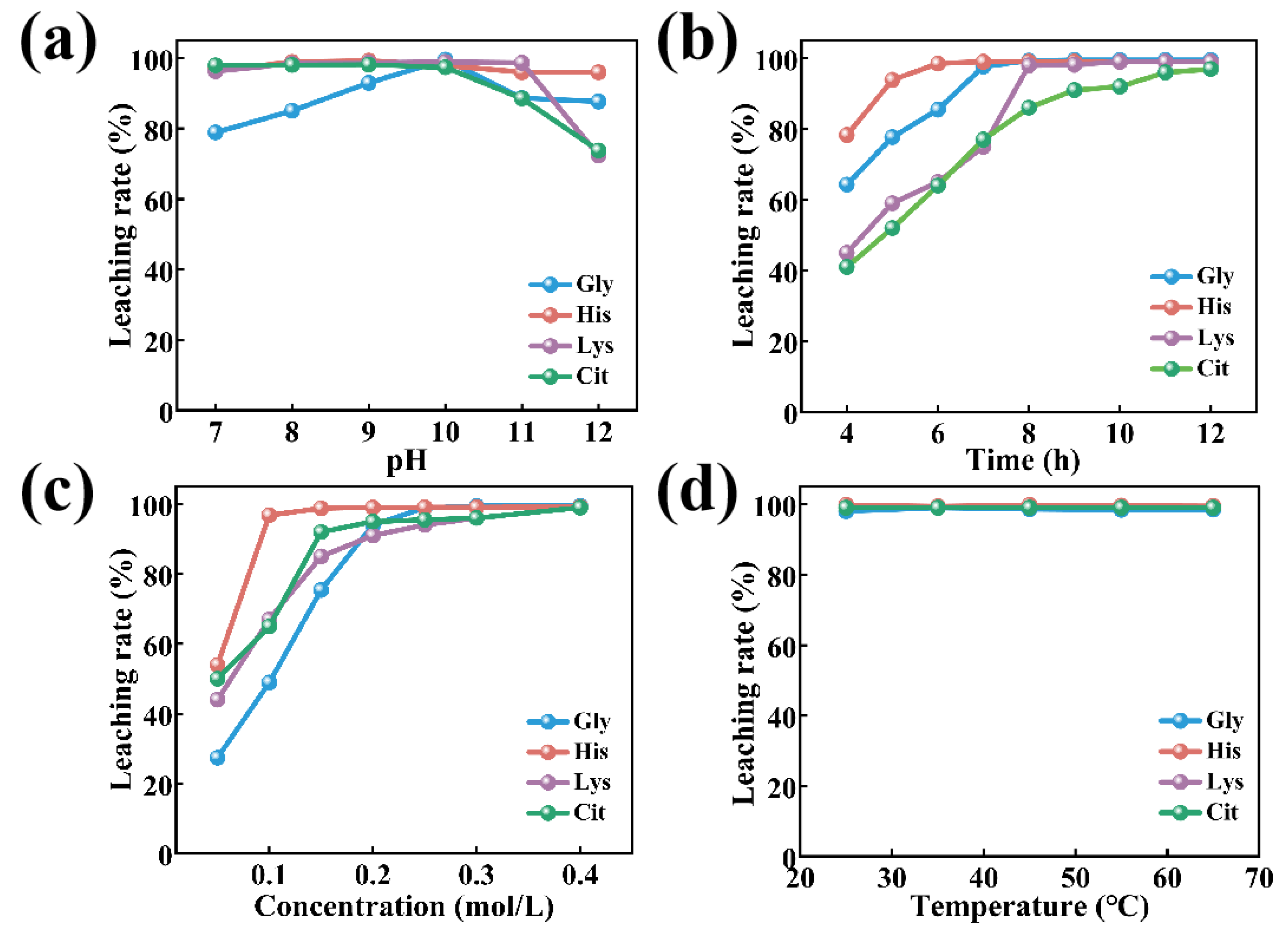

3.1. Comparison of the Leaching Effects of Different Types of Amino Acids on Cobalt Subsection

3.2 Parameter Optimization

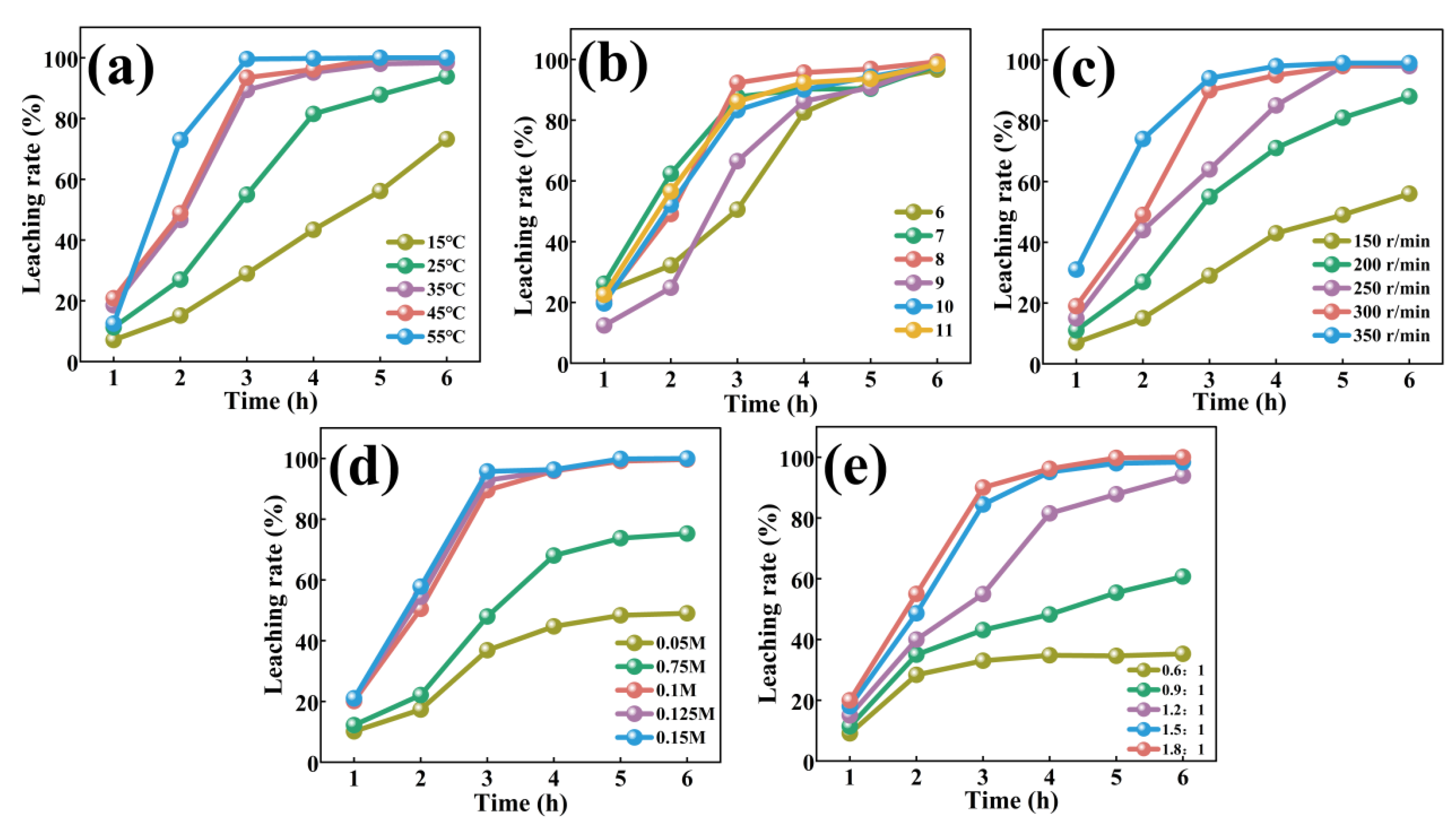

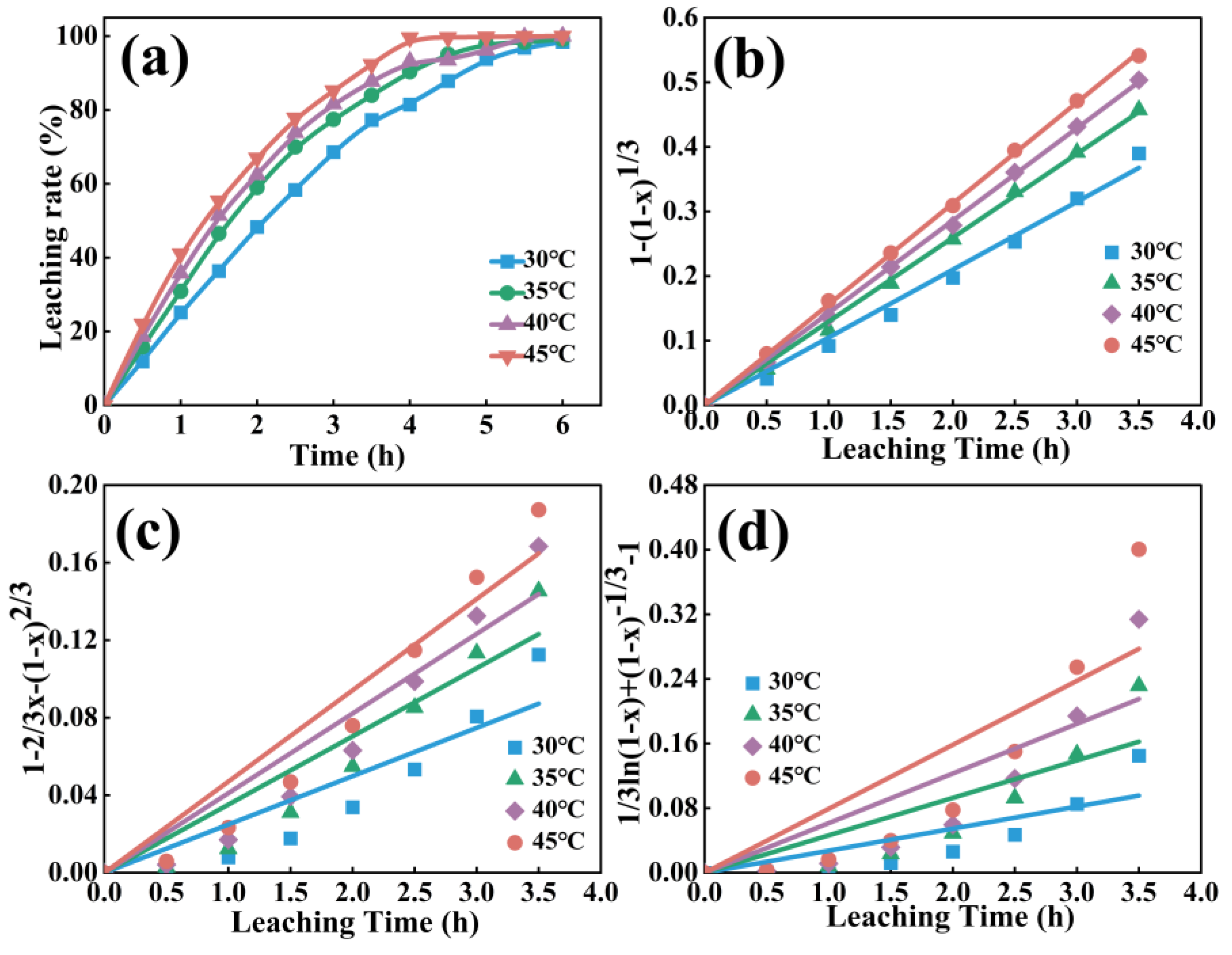

3.2.1 Effect of Temperature

3.2.2 Effect of pH

3.2.3 Effect of Stirring Speed

3.2.4 Effect of Histidine Concentration

3.2.5 Effect of His/Co Molar Ratio

3.2.6 Selective Leaching of Cu-Co Alloy Slag

4. Discussion

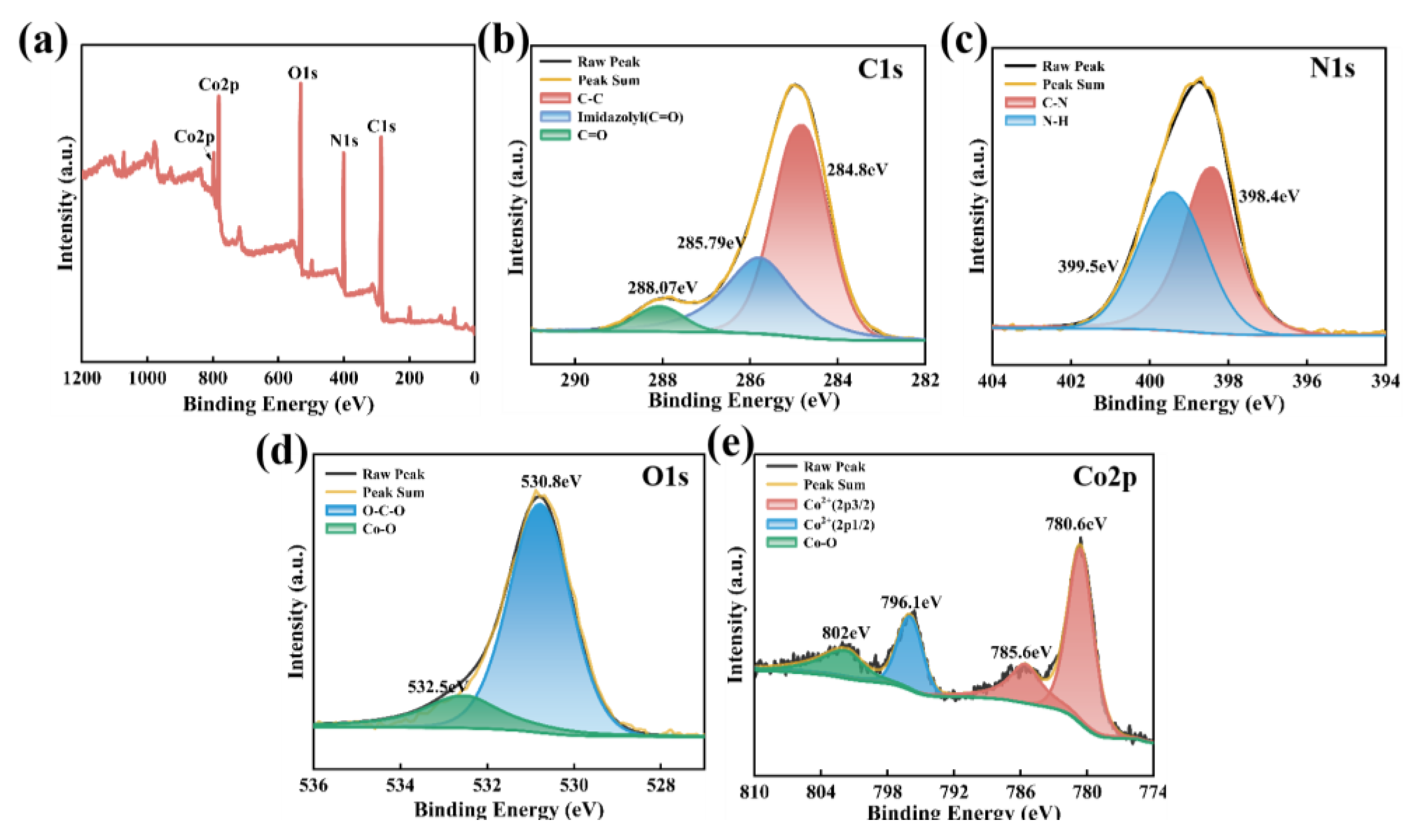

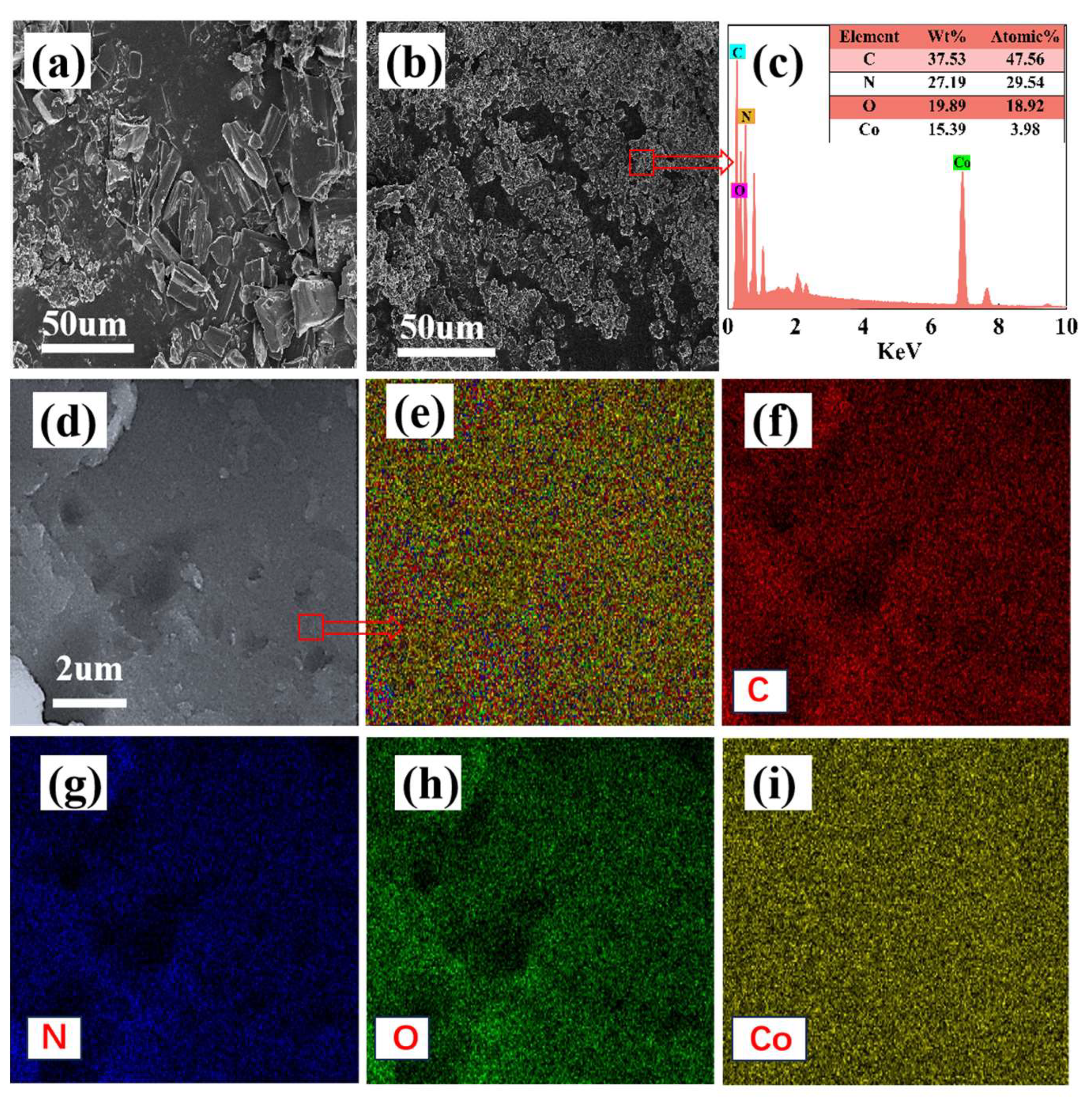

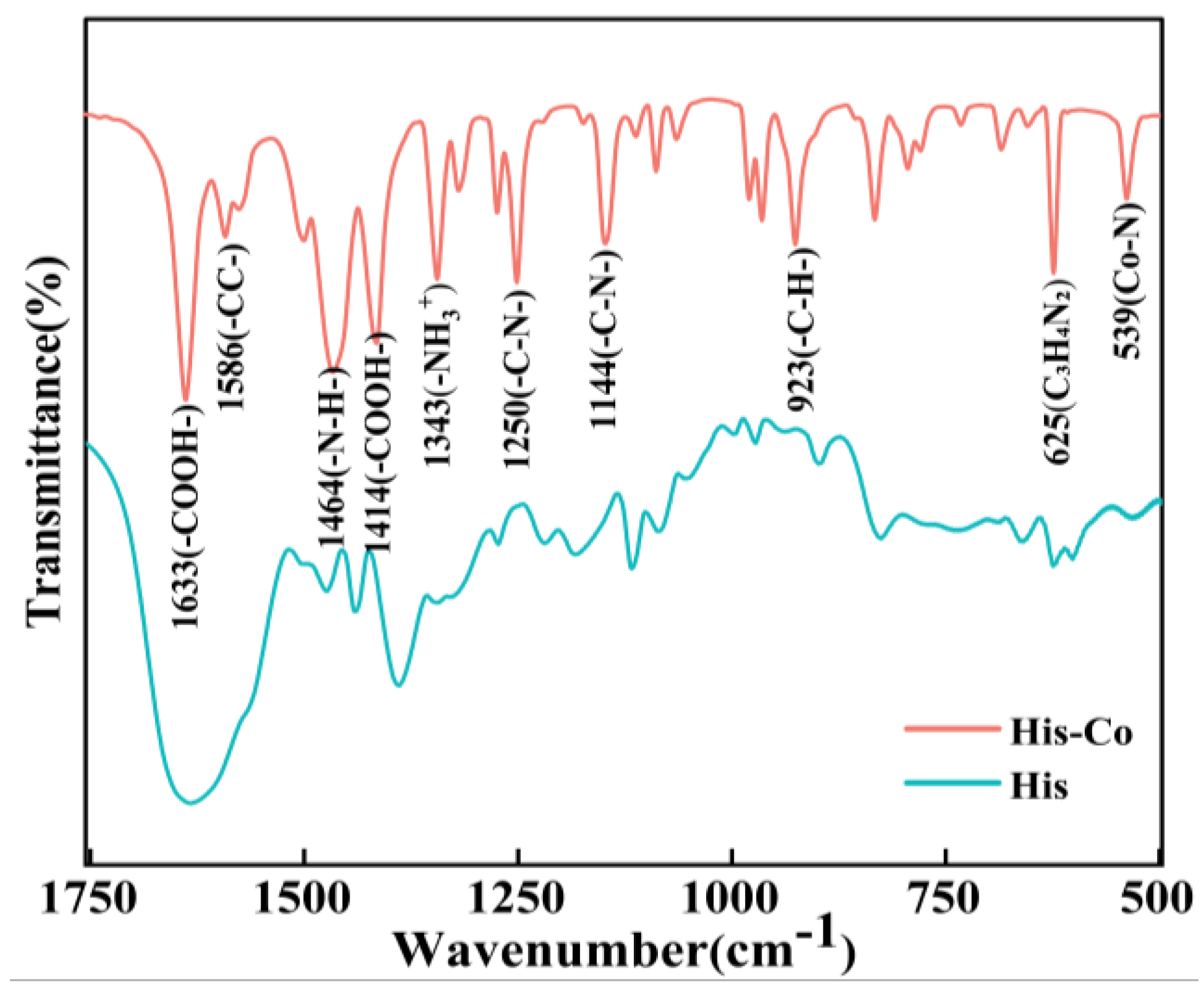

4.1 characterization Analysis

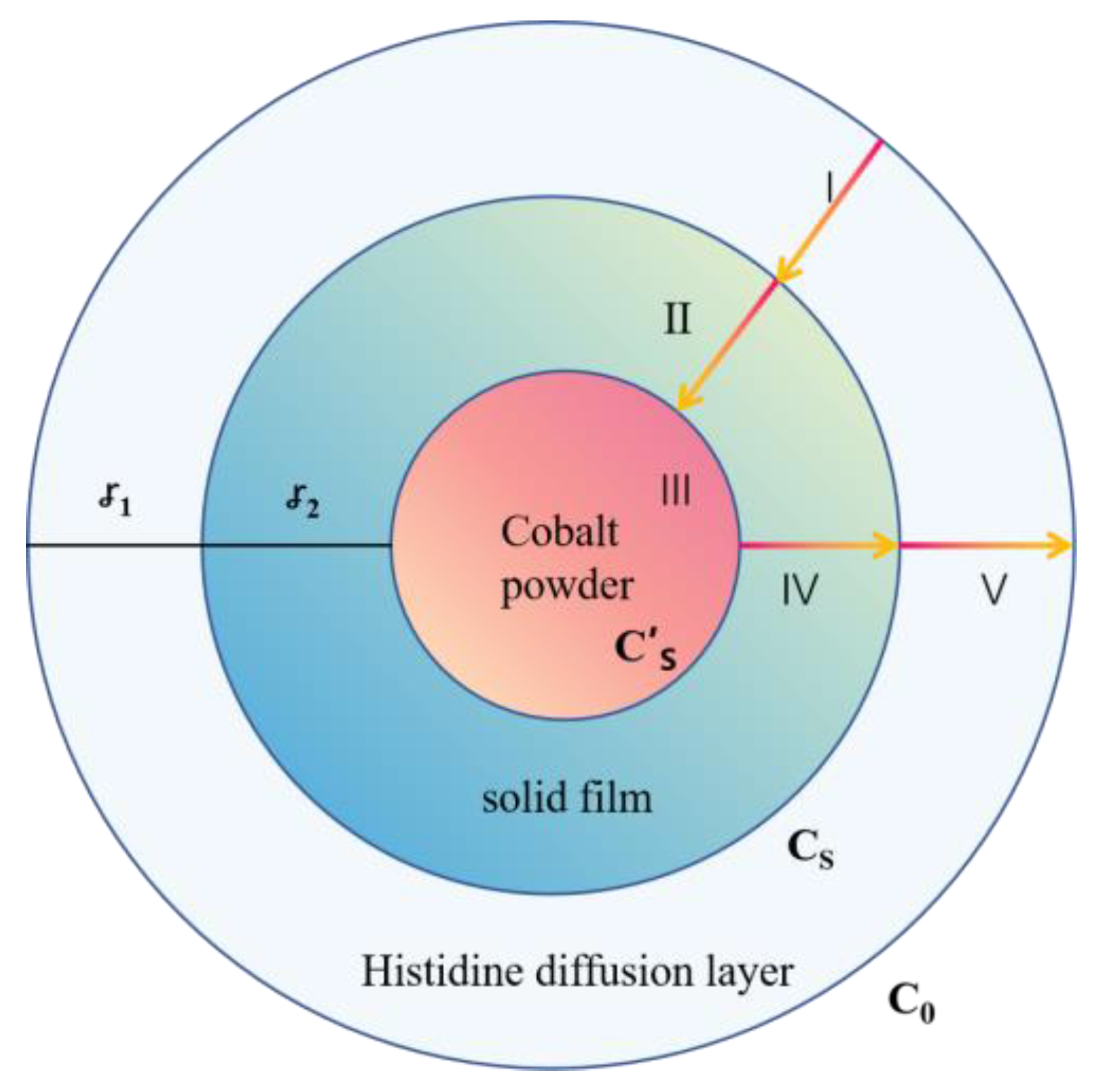

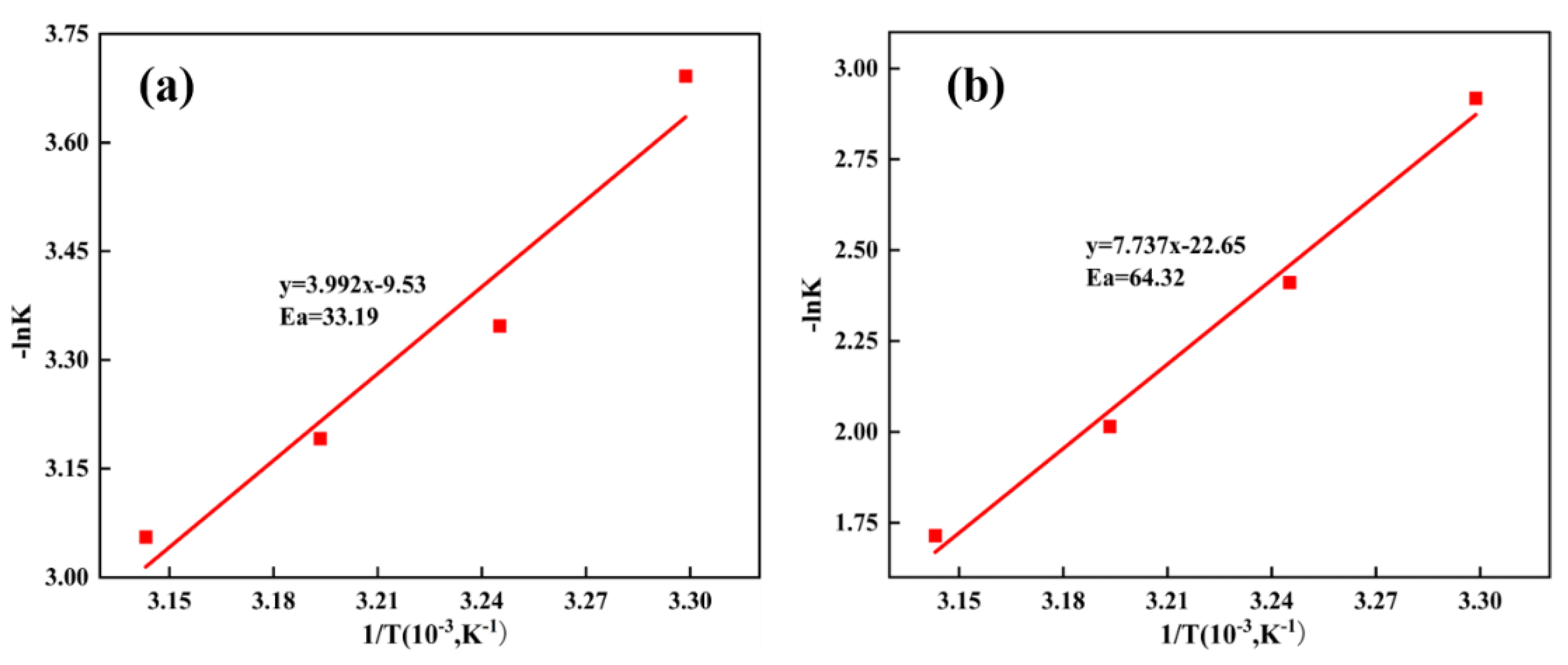

4.2 Leaching Kinetics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Z. Liping, X. Wanhai, L. Guobiao, W. Dong, W. Jian, D. Haojie, L. Yong, Y. Chunlin, Q. Tao, W. Zhi, A cleaner and sustainable method for recovering rare earth and cobalt from NdFeB leaching residues. Journal of Cleaner Production 2023, 422. [Google Scholar]

- H. Yukun, C. Pengxu, S. Xuanzhao, F. Biao, P. Weijun, L. Jiang, C. Yijun, Z. Xiaofeng, Extraction and recycling technologies of cobalt from primary and secondary resources: A comprehensive review. International Journal of Minerals, Metallurgy and Materials 2024, 31, 628–649. [Google Scholar]

- Q. Hong, M. Brian, Z. Jianwei, Y. Dawei, G. Xueyi, T. Qinghua, Hydrochlorination of Copper-Cobalt Alloy for Efficient Separation of Valuable Metals. Journal of Sustainable Metallurgy 2022, 8, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Heejung, I. Yuta, J. Virginia, W.A. C, B. Scott, Engineering Polyhistidine Tags on Surface Proteins of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans: Impact of Localization on the Binding and Recovery of Divalent Metal Cations. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2022, 14, 10125–10133. [Google Scholar]

- C. Chunqing, F.A.T. N, H. Takafumi, W. Rie, G. Masahiro, Amino Acid Leaching of Critical Metals from Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries Followed by Selective Recovery of Cobalt Using Aqueous Biphasic System. ACS omega 2023, 8, 3198–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. Leqi, L. Zhongming, Z. Wen, Recovery of lithium and cobalt from spent Lithium- Ion batteries using organic aqua regia (OAR): Assessment of leaching kinetics and global warming potentials. Resources, Conservation & Recycling 2021, 167, 105416. [Google Scholar]

- L. Tian, A. Gong, X. Wu, X. Yu, Z. Xu, L. Chen, Process and kinetics of the selective extraction of cobalt from high-silicon low-grade cobalt ores using ammonia leaching. International Journal of Minerals Metallurgy and Materials 2022, 29, 218–227. [Google Scholar]

- B. B. Kumar, J.U. U., M. Munusamy, J. Lianghui, Y.E. Hua, C. Bin, Biological Leaching and Chemical Precipitation Methods for Recovery of Co and Li from Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2018, 6, 12343–12352. [Google Scholar]

- L. Li, Y. Bian, X. Zhang, Y. Guan, E. Fan, F. Wu, R. Chen, Process for recycling mixed-cathode materials from spent lithium-ion batteries and kinetics of leaching. Waste Management 2018, 71, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed O,Zixian D,Huan L. Selective extraction of nickel and cobalt from disseminated sulfide flotation cleaner tailings using alkaline glycine-ammonia leaching solutions. Minerals Engineering 2023, 204, 108418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Shun-xiang, J. Si-qi, N. Chun-chen, L. Biao, C. Hong-hao, Z. Xiang-nan, Kinetic characteristics and mechanism of copper leaching from waste printed circuit boards by environmental friendly leaching system. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2022, 166, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, L. Huan, D. Zixian, E. Jacques, Selective extraction of Ni and Co from a pyrrhotite-rich flotation slime using an alkaline glycine-based leach system. Minerals Engineering 2023, 203, 108330. [Google Scholar]

- E. A. Oraby, J.J. Eksteen, The selective leaching of copper from a gold–copper concentrate in glycine solutions. Hydrometallurgy 2014, 150, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Chen, R. Wang, Y. Qi, Y. Han, R. Wang, J. Fu, F. Meng, X. Yi, J. Huang, J. Shu, Cobalt and lithium leaching from waste lithium ion batteries by glycine. Journal of Power Sources 2021, 482, 228942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Manivannan, S.M.G. Prabhu, R.E. R., v.H.E. D., Hydrometallurgical leaching and recovery of cobalt from lithium ion battery. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2022, 28, 102915. [Google Scholar]

- J. J. Eksteen, E.A. Oraby, V. Nguyen, Leaching and ion exchange based recovery of nickel and cobalt from a low grade, serpentine-rich sulfide ore using an alkaline glycine lixiviant system. Minerals Engineering 2020, 145, 106073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan L,Zixian D,Elsayed O, et al. Amino acids as lixiviants for metals extraction from natural and secondary resources with emphasis on glycine: A literature review. Hydrometallurgy 2023, 216, 106008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eksteen J,Oraby E,Nguyen V. Leaching and ion exchange based recovery of nickel and cobalt from a low grade, serpentine-rich sulfide ore using an alkaline glycine lixiviant system. Minerals Engineering 2020, 145, 106073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue Sun,Yaru Shi,Changgui Li,Hu Shi. Histidine Protonation Behaviors on Structural Properties and Aggregation Properties of Aβ(1-42) Mature Fibril: Approaching by Edge Effects. The journal of physical chemistry 2024, 128. [Google Scholar]

- Essential Amino Acids; Findings from University Erlangen-Nurnberg Has Provided New Data on Essential Amino Acids (A facile UV-light mediated synthesis of L-histidine stabilized silver nanocluster for efficient photodegradation of methylene blue). Science Letter 2015, 404, 27–35.

- Li H,Oraby E,Eksteen J. An alternative amino acid leaching of base metals from waste printed circuit boards using alkaline glutamate solutions: A comparative study with glycine. Separation and Purification Technology 2025, 356, 129953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, Y. Zu, Y. Fu, R. Meng, S. Guo, Z. Xing, S. Tan, Hydrothermal synthesis of histidine-functionalized single-crystalline gold nanoparticles and their pH-dependent UV absorption characteristic. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2009, 76, 311–316. [Google Scholar]

- M. Nidya, M. Umadevi, B.J.M. Rajkumar, Optical and morphological studies of L-histidine functionalised silver nanoparticles synthesised by two different methods. Journal of Experimental Nanoscience 2015, 10, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. M. Lin, S. Geng, N. Li, S.G. Liu, N.B. Li, H.Q. Luo, l-Histidine-protected copper nanoparticles as a fluorescent probe for sensing ferric ions. Sensors & Actuators: B. Chemical 2017, 252, 912–918. [Google Scholar]

- J. J. Eksteen, E.A. Oraby, The leaching and adsorption of gold using low concentration amino acids and hydrogen peroxide: Effect of catalytic ions, sulphide minerals and amino acid type. Minerals Engineering 2015, 70, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armentrout P B,Stevenson Brandon C,Ghiassee Maryam,Boles Georgia C,Berden Giel,Oomens Jos. Infrared multiple-photon dissociation spectroscopy of cationized glycine: effects of alkali metal cation size on gas-phase conformation. Physical chemistry chemical physics 2022, 24, 37. [Google Scholar]

- L. Tianya, S. Jiancheng, D. Yaling, H. Ling, C. Shaoqin, C. Mengjun, H. Weiping, Enhanced recovery of copper from reclaimed copper smelting fly ash via leaching and electrowinning processes. Separation and Purification Technology 2021, 273, 118943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelali B,Younes C,Djamel S. A periodic DFT study of IR spectra of amino acids: An approach toward a better understanding of the N-H and O-H stretching regions. Vibrational Spectroscopy 2021, 116, 103280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Dmitrii, G. Sergei, Mixed-Ligand Nickel(II) Complexes with Histidine and Cysteine in Aqueous Solution: Thermodynamic Approach. Journal of Solution Chemistry 2023, 53, 372–385. [Google Scholar]

- T. Hongyu, G. Zhengqi, P. Jian, Z. Deqing, Y. Congcong, X. Yuxiao, L. Siwei, W. Dingzheng, Comprehensive review on metallurgical recycling and cleaning of copper slag. Resources Conservation & Recycling 2021, 168, 105366. [Google Scholar]

- F. M. Paiva,J.C. Batista,F.S.C. Rêgo,J.A. Lima,P.T.C. Freire,F.E.A. Melo.Infrared and Raman spectroscopy and DFT calculations of DL amino acids: Valine and lysine hydrochloride. Journal of Molecular Structure 2017, 1127, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amino Acids - Histidine; New Histidine Findings from University of Tanta Reported (Nano-sized metal complexes of azo L-histidine: Synthesis, characterization and their application for catalytic oxidation of 2-amino phenol). Chemicals & Chemistry 2018, 32, 4229.

- Amino Acids - Histidine; Findings from Y. He and Colleagues Update Understanding of Histidine (Histidine and histidine dimer as green inhibitors for carbon steel in 3wt% sodium chloride solution; Electrochemical, XPS and Quantum chemical calculation studies). Journal of Engineering 2018, 13, 2136–2153. [Google Scholar]

- Technology - Vacuum Technology; Study Findings from D. Moszynski et al Broaden Understanding of Vacuum Technology (XPS study of cobalt-ceria catalysts for ammonia synthesis - The reduction process). Chemicals & Chemistry 2018, 155, 434–438. [Google Scholar]

- Y. Han, X. Yi, R. Wang, J. Huang, M. Chen, Z. Sun, S. Sun, J. Shu, Copper extraction from waste printed circuit boards by glycine. Separation and Purification Technology 2020, 253, 117463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh, Mostafa, E. Zarandi, Ali, Pasquier, L. César, Azizi, Asghar, Kinetic Investigation on Leaching of Copper from a Low-Grade Copper Oxide Deposit in Sulfuric Acid Solution: A Case Study of the Crushing Circuit Reject of a Copper Heap Leaching Plant. Journal of Sustainable Metallurgy 2021, 7, 1154–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E. Bidari, V. Aghazadeh, Investigation of Copper Ammonia Leaching from Smelter Slags: Characterization, Leaching and Kinetics. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions 2015, 46, 2305–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. B. C., O.E. A., E.J. J., Kinetics of malachite leaching in alkaline glycine solutions. Mineral Processing and Extractive Metallurgy 2021, 130, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. A. M., M.M. S., Leaching kinetics and predictive models for elements extraction from copper oxide ore in sulphuric acid. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers 2021, 121, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements | Co | Cu | Fe | Pb | Ni |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wt.% | 6.2 | 30.7 | 61.2 | 1.4 | 0.42 |

| Temperature (℃) |

Internal diffusion control 1-(2/3)x-(1-x)2/3 | Chemical reaction control 1-(1-x)1/3 | Mixed control 1/3ln(1-x)+(1-x)-1/3-1 |

|||

| k1(min-1) | R2 | k2(min-1) | R2 | k2(min-1) | R2 | |

| 30 | 0.02493 | 0.846 | 0.05406 | 0.989 | 0.02732 | 0.716 |

| 35 | 0.03519 | 0.902 | 0.08991 | 0.998 | 0.04637 | 0.765 |

| 40 | 0.04110 | 0.911 | 0.13334 | 0.999 | 0.06148 | 0.747 |

| 45 | 0.04709 | 0.929 | 0.17980 | 0.999 | 0.07924 | 0.752 |

| Control model | Slope k′ | Correlation coefficient(R2) | Ea (kJ/mol) |

| Chemical reaction control | 7.74 | 0.99 | 64.32 |

| Internal diffusion control | 3.99 | 0.95 | 33.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).