Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The main aspect for greener process of materials preparation is taking constituents of the designed material from green sources. Recycling is the fundamental feature for the reutilization of already applied elements with a subsequently minor wasting of raw materials. Transition elements as cobalt, nickel and manganese can be found in a variety of application and several sort of energy storage devices contain a considerable amount of these elements. From as stated before, nowadays is more and more interesting drive research on recovery and separation of cobalt, nickel and manganese from energy storage devices. The MIL (Institute Lavoisier Materials) are metal organic frameworks of high porosity often utilized for a wide variety of application as gas storage, conductivity, electricity storage and supercapacitors, sensing and detection of analytes, environment saving purpose. MIL-53 is the metal organic framework employed in the followed research for cobalt, nickel and manganese adsorption as the first time.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Cobalt

1.2. Importance of Cobalt in Metal Organic Framework and Some Common Applications

1.3. Cobalt Adsorption

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

4. Synthesis

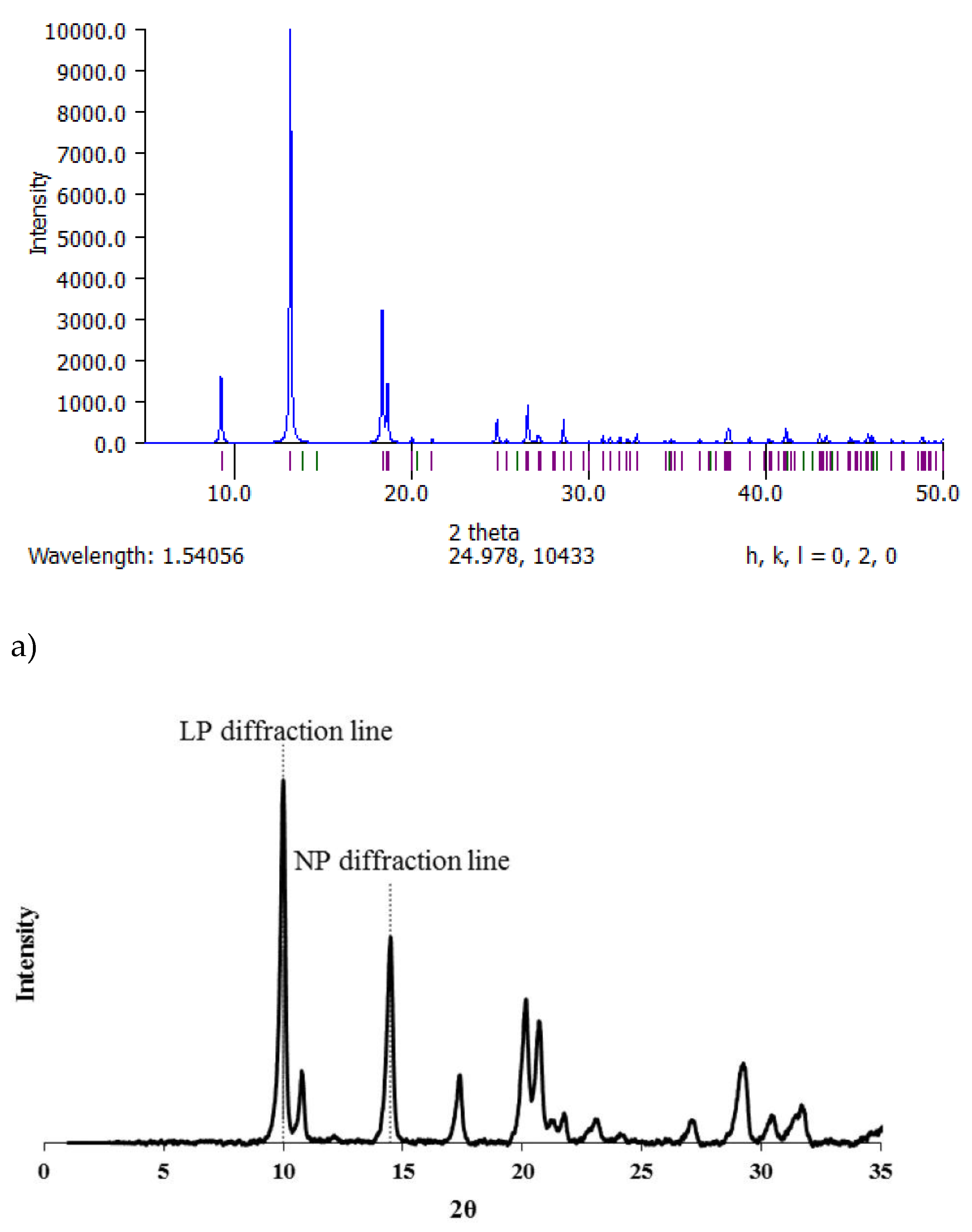

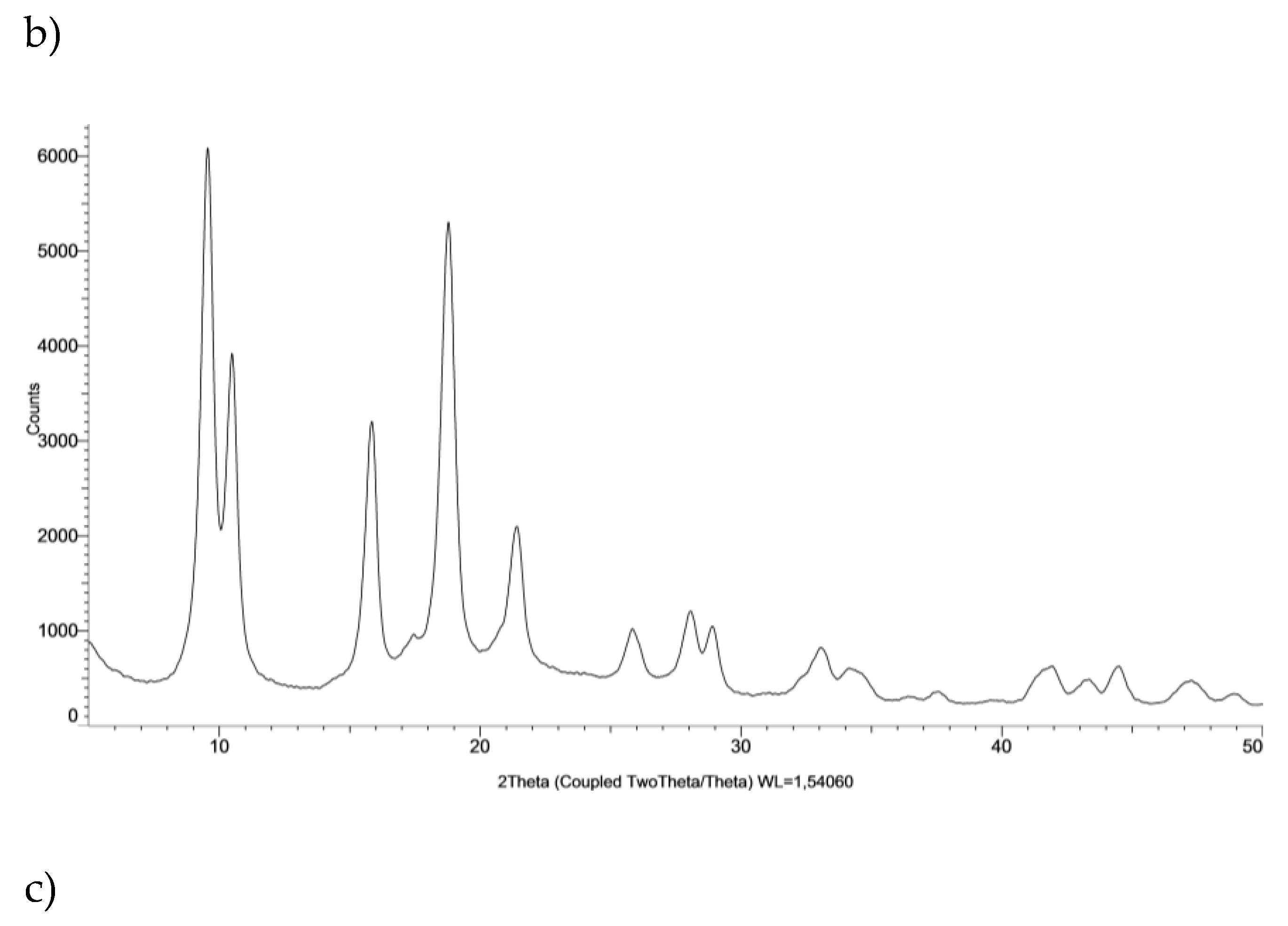

5. Structural Characterization

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- [1] Md. R. Awual, Md. M. Hasan, A. Islam, A. M. Asiri, e M. M. Rahman, «Optimization of an innovative composited material for effective monitoring and removal of cobalt(II) from wastewater», Journal of Molecular Liquids, vol. 298, p. 112035, gen. 2020. [CrossRef]

- [2] S. Pullen e G. H. Clever, «Mixed-Ligand Metal–Organic Frameworks and Heteroleptic Coordination Cages as Multifunctional Scaffolds—A Comparison», Acc. Chem. Res., vol. 51, fasc. 12, pp. 3052–3064, dic. 2018. [CrossRef]

- [3] J. Da Silva Burgal, L. Peeva, e A. Livingston, «Towards improved membrane production: using low-toxicity solvents for the preparation of PEEK nanofiltration membranes», Green Chem., vol. 18, fasc. 8, pp. 2374–2384, 2016. [CrossRef]

- [4] G. Gumilar et al., «General synthesis of hierarchical sheet/plate-like M-BDC (M = Cu, Mn, Ni, and Zr) metal–organic frameworks for electrochemical non-enzymatic glucose sensing», Chem. Sci., vol. 11, fasc. 14, pp. 3644–3655, apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- [5] S. Sakaida et al., «Crystalline coordination framework endowed with dynamic gate-opening behaviour by being downsized to a thin film», Nature Chem, vol. 8, fasc. 4, Art. fasc. 4, apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- [6] X. Zhang et al., «Electrochemically Assisted Interfacial Growth of MOF Membranes», Matter, vol. 1, fasc. 5, pp. 1285–1292, nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- [7] M. Y. B. Zulkifli, K. Su, R. Chen, J. Hou, e V. Chen, «Future perspective on MOF glass composite thin films as selective and functional membranes for molecular separation», Advanced Membranes, vol. 2, p. 100036, gen. 2022. [CrossRef]

- [8] Y. Zhou, X. Wei, L. Huang, e H. Wang, «Worldwide research on extraction and recovery of cobalt through bibliometric analysis: a review», Environ Sci Pollut Res, vol. 30, fasc. 7, pp. 16930–16946, feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- [9] E. Savinova, C. Evans, É. Lèbre, M. Stringer, M. Azadi, e R. K. Valenta, «Will global cobalt supply meet demand? The geological, mineral processing, production and geographic risk profile of cobalt», Resources, Conservation and Recycling, vol. 190, p. 106855, mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- [10] X. Feng et al., «Aluminum Hydroxide Secondary Building Units in a Metal–Organic Framework Support Earth-Abundant Metal Catalysts for Broad-Scope Organic Transformations», ACS Catal., vol. 9, fasc. 4, pp. 3327–3337, apr. 2019. [CrossRef]

- [11] J. A. Botas, G. Calleja, M. Sánchez-Sánchez, e M. G. Orcajo, «Cobalt Doping of the MOF-5 Framework and Its Effect on Gas-Adsorption Properties», Langmuir, vol. 26, fasc. 8, pp. 5300–5303, apr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- [12] J.-H. Choi, J. Jegal, e W.-N. Kim, «Fabrication and characterization of multi-walled carbon nanotubes/polymer blend membranes», Journal of Membrane Science, vol. 284, fasc. 1, pp. 406–415, nov. 2006. [CrossRef]

- [13] M. Rauche et al., «Solid-state NMR studies of metal ion and solvent influences upon the flexible metal-organic framework DUT-8», Solid State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, vol. 120, p. 101809, ago. 2022. [CrossRef]

- [14] S. Ehrling et al., «Tailoring the Adsorption-Induced Flexibility of a Pillared Layer Metal–Organic Framework DUT-8(Ni) by Cobalt Substitution», Chem. Mater., vol. 32, fasc. 13, pp. 5670–5681, lug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- [15] H. Miura et al., «Spatiotemporal Design of the Metal–Organic Framework DUT-8(M)», Advanced Materials, vol. 35, fasc. 8, p. 2207741, 2023. [CrossRef]

- [16] H. Kim e C. S. Hong, «MOF-74-type frameworks: tunable pore environment and functionality through metal and ligand modification», CrystEngComm, vol. 23, fasc. 6, pp. 1377–1387, feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- [17] D. Feng et al., «Kinetically tuned dimensional augmentation as a versatile synthetic route towards robust metal–organic frameworks», Nat Commun, vol. 5, fasc. 1, Art. fasc. 1, dic. 2014. [CrossRef]

- [18] C. Dong, J.-J. Yang, L.-H. Xie, G. Cui, W.-H. Fang, e J.-R. Li, «Catalytic ozone decomposition and adsorptive VOCs removal in bimetallic metal-organic frameworks», Nat Commun, vol. 13, fasc. 1, Art. fasc. 1, ago. 2022. [CrossRef]

- [19] M.-H. Zeng et al., «Apical Ligand Substitution, Shape Recognition, Vapor-Adsorption Phenomenon, and Microcalorimetry for a Pillared Bilayer Porous Framework That Shrinks or Expands in Crystal-to-Crystal Manners upon Change in the Cobalt(II) Coordination Environment», Inorg. Chem., vol. 48, fasc. 15, pp. 7070–7079, ago. 2009. [CrossRef]

- [20] A. Helal, S. Shaheen Shah, M. Usman, M. Y. Khan, Md. A. Aziz, e M. Mizanur Rahman, «Potential Applications of Nickel-Based Metal-Organic Frameworks and their Derivatives», The Chemical Record, vol. 22, fasc. 7, p. e202200055, 2022. [CrossRef]

- [21] H. Olivier-Bourbigou, P. A. R. Breuil, L. Magna, T. Michel, M. F. Espada Pastor, e D. Delcroix, «Nickel Catalyzed Olefin Oligomerization and Dimerization», Chem. Rev., vol. 120, fasc. 15, pp. 7919–7983, ago. 2020. [CrossRef]

- [22] T. Wurzel, S. Malcus, e L. Mleczko, «Reaction engineering investigations of CO2 reforming in a fluidized-bed reactor», Chemical Engineering Science, vol. 55, fasc. 18, pp. 3955–3966, set. 2000. [CrossRef]

- [23] M. A. Nieva, M. M. Villaverde, A. Monzón, T. F. Garetto, e A. J. Marchi, «Steam-methane reforming at low temperature on nickel-based catalysts», Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 235, pp. 158–166, gen. 2014. [CrossRef]

- [24] J. Xu, W. Zhou, Z. Li, J. Wang, e J. Ma, «Biogas reforming for hydrogen production over nickel and cobalt bimetallic catalysts», International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 34, fasc. 16, pp. 6646–6654, ago. 2009. [CrossRef]

- [25] B. Abdullah, N. A. Abd Ghani, e D.-V. N. Vo, «Recent advances in dry reforming of methane over Ni-based catalysts», Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 162, pp. 170–185, set. 2017. [CrossRef]

- [26] L. Karam, J. Reboul, S. Casale, P. Massiani, e N. El Hassan, «Porous Nickel-Alumina Derived from Metal-Organic Framework (MIL-53): A New Approach to Achieve Active and Stable Catalysts in Methane Dry Reforming», ChemCatChem, vol. 12, fasc. 1, pp. 373–385, 2020. [CrossRef]

- [27] N. Hongloi, P. Prapainainar, e C. Prapainainar, «Review of green diesel production from fatty acid deoxygenation over Ni-based catalysts», Molecular Catalysis, vol. 523, p. 111696, mag. 2022. [CrossRef]

- [28] X. Sun et al., «Metal–Organic Framework Mediated Cobalt/Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Hybrids as Efficient and Chemoselective Catalysts for the Hydrogenation of Nitroarenes», ChemCatChem, vol. 9, fasc. 10, pp. 1854–1862, 2017. [CrossRef]

- [29] F. Su, L. Lv, F. Y. Lee, T. Liu, A. I. Cooper, e X. S. Zhao, «Thermally Reduced Ruthenium Nanoparticles as a Highly Active Heterogeneous Catalyst for Hydrogenation of Monoaromatics», J. Am. Chem. Soc., vol. 129, fasc. 46, pp. 14213–14223, nov. 2007. [CrossRef]

- [30] B. Lin et al., «Preparation of a Highly Efficient Carbon-Supported Ruthenium Catalyst by Carbon Monoxide Treatment», Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., vol. 57, fasc. 8, pp. 2819–2828, feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- [31] Z. Liu, Y. Yang, J. Mi, X. Tan, e Y. Song, «Synthesis of copper-containing ordered mesoporous carbons for selective hydrogenation of cinnamaldehyde», Catalysis Communications, vol. 21, pp. 58–62, mag. 2012. [CrossRef]

- [32] C.-C. Huang, Y.-H. Li, Y.-W. Wang, e C.-H. Chen, «Hydrogen storage in cobalt-embedded ordered mesoporous carbon», International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 38, fasc. 10, pp. 3994–4002, apr. 2013. [CrossRef]

- [33] Y. Liu, Y. Wang, Y. Chen, C. Wang, e L. Guo, «NiCo-MOF nanosheets wrapping polypyrrole nanotubes for high-performance supercapacitors», Applied Surface Science, vol. 507, p. 145089, mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- [34] Q. Li et al., «Self-assembled Mo doped Ni-MOF nanosheets based electrode material for high performance battery-supercapacitor hybrid device», International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 45, fasc. 41, pp. 20820–20831, ago. 2020. [CrossRef]

- [35] J. Li et al., «Highly effective electromagnetic wave absorbing Prismatic Co/C nanocomposites derived from cubic metal-organic framework», Composites Part B: Engineering, vol. 182, p. 107613, feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- [36] M. Azadfalah, A. Sedghi, H. Hosseini, e H. Kashani, «Cobalt based Metal Organic Framework/Graphene nanocomposite as high performance battery-type electrode materials for asymmetric Supercapacitors», Journal of Energy Storage, vol. 33, p. 101925, gen. 2021. [CrossRef]

- [37] L. Wan et al., «ZIF-8 derived nitrogen-doped porous carbon/carbon nanotube composite for high-performance supercapacitor», Carbon, vol. 121, pp. 330–336, set. 2017. [CrossRef]

- [38] Y. Jiao, J. Pei, C. Yan, D. Chen, Y. Hu, e G. Chen, «Layered nickel metal–organic framework for high performance alkaline battery-supercapacitor hybrid devices», Journal of Materials Chemistry A, vol. 4, fasc. 34, pp. 13344–13351, 2016. [CrossRef]

- [39] X. Hu et al., «Cobalt-based metal organic framework with superior lithium anodic performance», Journal of Solid State Chemistry, vol. 242, pp. 71–76, ott. 2016. [CrossRef]

- [40] H. Shayegan, V. Safari Fard, H. Taherkhani, e M. A. Rezvani, «Efficient Removal of Cobalt(II) Ion from Aqueous Solution Using Amide-Functionalized Metal-Organic Framework», Journal of Applied Organometallic Chemistry, vol. 2, fasc. 3, pp. 109–118, ago. 2022. [CrossRef]

- [41] X. Wang, Y. Zhou, J. Men, C. Liang, e M. Jia, «Removal of Co(II) from aqueous solutions with amino acid-modified hydrophilic metal-organic frameworks», Inorganica Chimica Acta, vol. 547, p. 121337, mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- [42] H. Shahriyari Far, M. Hasanzadeh, M. Najafi, T. R. Masale Nezhad, e M. Rabbani, «Efficient Removal of Pb(II) and Co(II) Ions from Aqueous Solution with a Chromium-Based Metal–Organic Framework/Activated Carbon Composites», Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., vol. 60, fasc. 11, pp. 4332–4341, mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- [43] G. Yuan et al., «Schiff base anchored on metal-organic framework for Co (II) removal from aqueous solution», Chemical Engineering Journal, vol. 326, pp. 691–699, ott. 2017. [CrossRef]

- [44] G. Yuan et al., «Removal of Co(II) from aqueous solution with functionalized metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) composite», J Radioanal Nucl Chem, vol. 322, fasc. 2, pp. 827–838, nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- [45] F. Fang et al., «Removal of cobalt ions from aqueous solution by an amination graphene oxide nanocomposite», Journal of Hazardous Materials, vol. 270, pp. 1–10, apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- [46] M. Li et al., «Efficient removal of Co(II) from aqueous solution by flexible metal-organic framework membranes», Journal of Molecular Liquids, vol. 324, p. 114718, feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- [47] G. Yuan et al., «Glycine derivative-functionalized metal-organic framework (MOF) materials for Co(II) removal from aqueous solution», Applied Surface Science, vol. 466, pp. 903–910, feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- [48] Md. A. Islam, Md. R. Awual, e M. J. Angove, «A review on nickel(II) adsorption in single and binary component systems and future path», Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, vol. 7, fasc. 5, p. 103305, ott. 2019. [CrossRef]

- [49] M. S. Hellal, A. M. Rashad, K. K. Kadimpati, S. K. Attia, e M. E. Fawzy, «Adsorption characteristics of nickel (II) from aqueous solutions by Zeolite Scony Mobile-5 (ZSM-5) incorporated in sodium alginate beads», Sci Rep, vol. 13, fasc. 1, p. 19601, nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- [50] A. Nour et al., «Efficient Nickel and Cobalt Recovery by Metal–Organic Framework-Based Mixed Matrix Membranes (MMM-MOFs)», ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng., vol. 12, fasc. 32, pp. 12014–12028, ago. 2024. [CrossRef]

- [51] M. S. M. Zahar, F. M. Kusin, e S. N. Muhammad, «Adsorption of Manganese in Aqueous Solution by Steel Slag», Procedia Environmental Sciences, vol. 30, pp. 145–150, gen. 2015. [CrossRef]

- [52] M. A. Karim, S. Nasir, T. W. Widowati, e U. Hasanudin, «Kinetic Study of Adsorption of Metal Ions (Iron and Manganese) in Groundwater Using Calcium Carbide Waste», J. Ecol. Eng., vol. 24, fasc. 5, pp. 155–165, mag. 2023. [CrossRef]

- [53] A. Wilamas, S. Vinitnantharat, e A. Pinisakul, «Manganese Adsorption onto Permanganate-Modified Bamboo Biochars from Groundwater», Sustainability, vol. 15, fasc. 8, Art. fasc. 8, gen. 2023. [CrossRef]

- [54] Y. Tong et al., «Systematic understanding of the potential manganese-adsorption components of a screened Lactobacillus plantarum CCFM436», RSC Adv., vol. 6, fasc. 104, pp. 102804–102813, ott. 2016. [CrossRef]

- [55] K. Fialova et al., «Removal of manganese by adsorption onto newly synthesized TiO2-based adsorbent during drinking water treatment», Environmental Technology, vol. 44, fasc. 9, pp. 1322–1333, apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- [56] T. Loiseau et al., «A Rationale for the Large Breathing of the Porous Aluminum Terephthalate (MIL-53) Upon Hydration», Chemistry—A European Journal, vol. 10, fasc. 6, pp. 1373–1382, 2004. [CrossRef]

- [57] A. Taheri, E. G. Babakhani, e J. Towfighi, «Study of synthesis parameters of MIL-53(Al) using experimental design methodology for CO2/CH4 separation», Adsorption Science & Technology, vol. 36, fasc. 1–2, pp. 247–269, feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

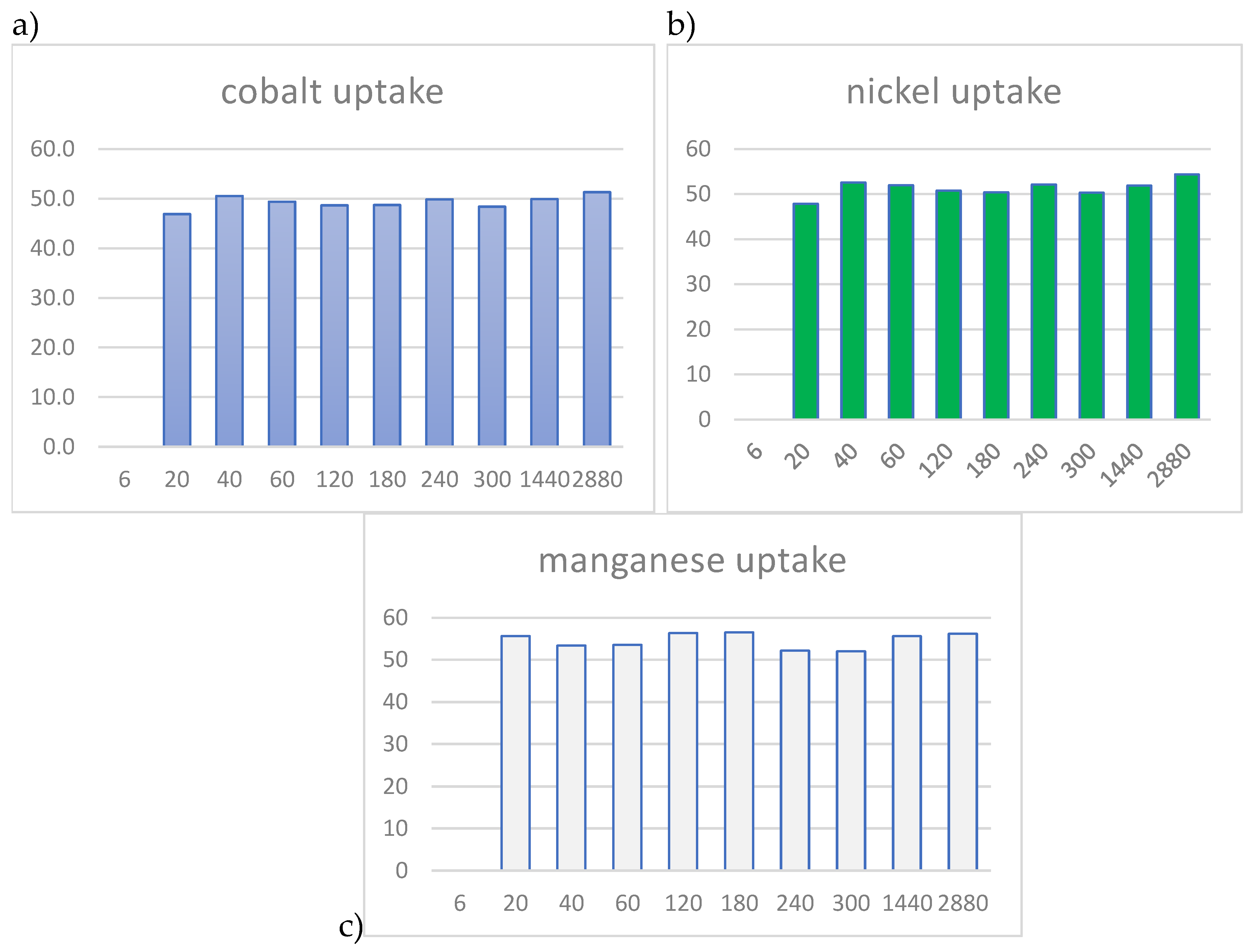

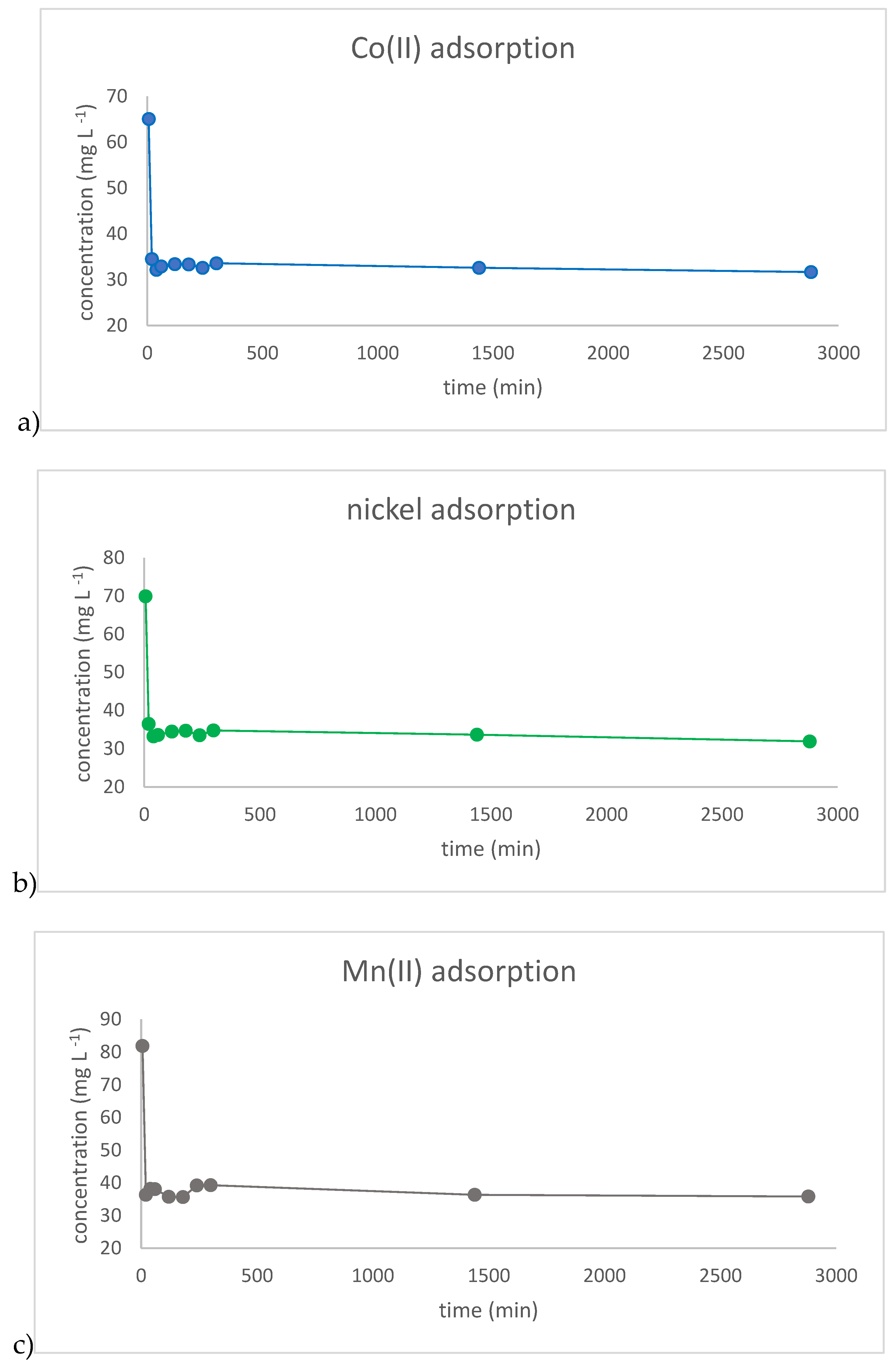

| Cobalt adsorption | |

| MOF | Equilibrium uptake capacity (mg g-1) |

| TMU-24 | 500.0 [40] |

| ZIF-90-lysine | 136.83 [41] |

| ZIF-90-methionine | 164.4 [41] |

| Cr-BDC | 138.0 [42] |

| UiO-66-CONH2 | 339.7 [44] |

| SrCu6Ser | 387.3 [50] |

| Glycine, diglycine, and triglycine were post-synthesized on MIL-101-NH2 | from 185.2 to 232.6 [47] |

| MIL-53(Al) (this work) | 33.4 |

| Nickel adsorption | |

| MIL-53(Al) (this work) | 38.0 |

| SrCu6Ser | 150.8 [50] |

| Manganese adsorption | |

| MIL-53(Al) (this work) | 46.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).