Submitted:

07 August 2025

Posted:

08 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

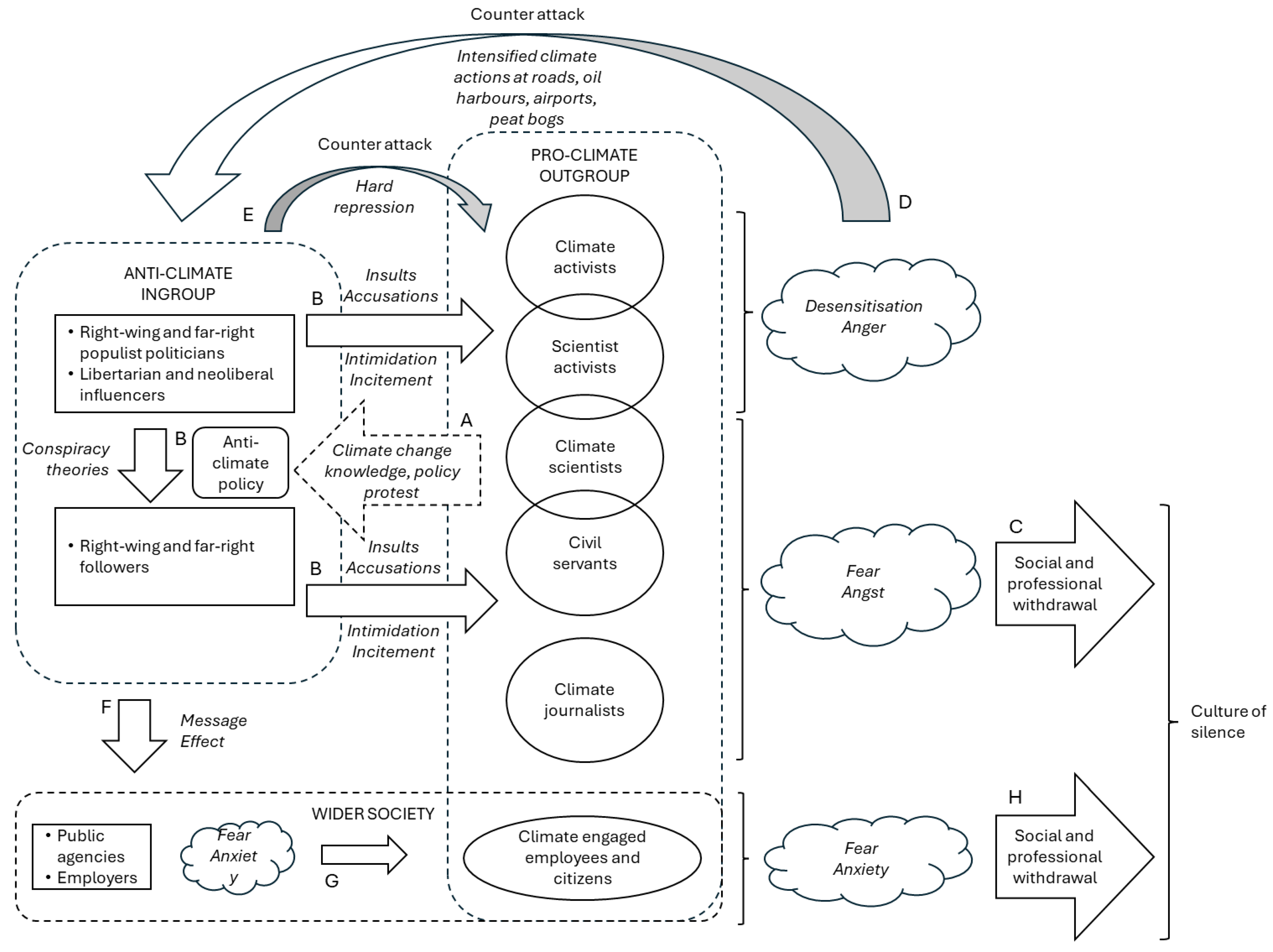

1.1. Hate Speech in Climate Politics

1.2. Aim of the Paper

- How are different target groups and people victimised by nasty rhetoric? Are there differences in target group victimisation?

- How do victims of nasty rhetoric react emotionally and behaviourally? Are there differences in emotional and behavioural reactions among different target groups?

- How resilient are different groups of victims?

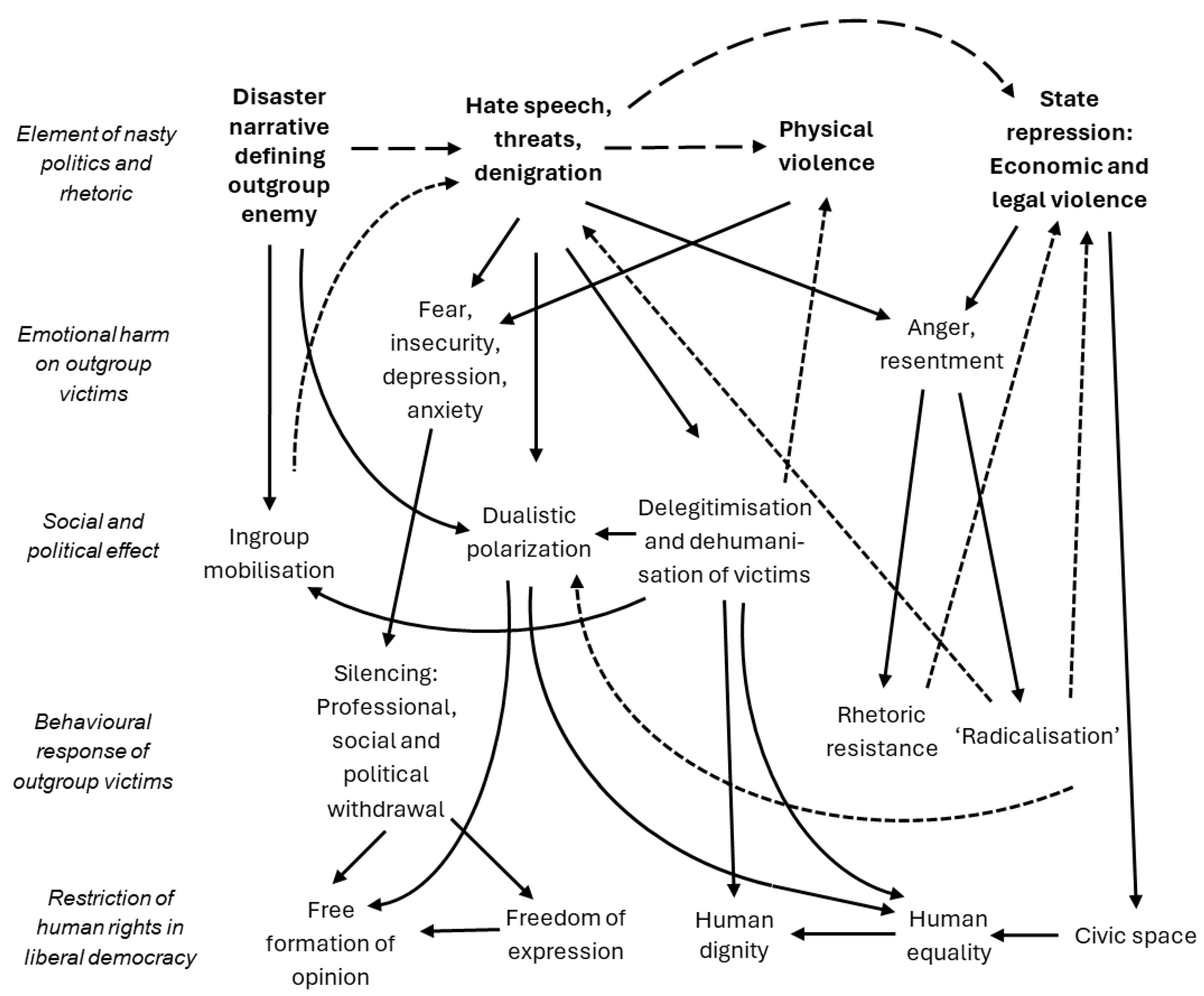

2. Nasty Rhetoric – Systematic Acts of Hate Speech and Hate Crime to Eliminate Political Opponents

2.1. Nasty Rhetoric and Far-Right Populism

2.2. Nasty Rhetoric and Emotions

3. Victimisation and Harm of Nasty Rhetoric

3.1. Victimisation

3.1.1. The Ideal Victim

3.1.2. Culture and Victims

3.1.3. Green Criminology and Victims in Climate Politics

Customary international law sets forth obligations for States to ensure the protection of the climate system and other parts of the environment from anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. These obligations include the following:(a) States have a duty to prevent significant harm to the environment by acting with due diligence and to use all means at their disposal to prevent activities carried out within their jurisdiction or control from causing significant harm to the climate system and other parts of the environment, in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities;(b) States have a duty to co-operate with each other in good faith to prevent significant harm to the climate system and other parts of the environment, which requires sustained and continuous forms of co-operation by States when taking measures to prevent such harm.

A breach by a State of any obligations [in relation to climate change mitigation] constitutes an internationally wrongful act entailing the responsibility of that State. The responsible State is under a continuing duty to perform the obligation breached. The legal consequences resulting from the commission of an internationally wrongful act may include the obligations of:(a) cessation of the wrongful actions or omissions, if they are continuing;(b) providing assurances and guarantees of non-repetition of wrongful actions or omissions, if circumstances so require; and(c) full reparation to injured States in the form of restitution, compensation and satisfaction, provided that the general conditions of the law of State responsibility are met, including that a sufficiently direct and certain causal nexus can be shown between the wrongful act and injury.

3.2. Emotional and Cognitive Impacts

3.3. Behavioural Impacts

4. Method and Materials

4.1. A Qualitative Case Study

- a stronghold of liberal democracy since World War II, able to develop and maintain a green and equitable welfare state, but is now showing signs of autocratisation and the end of Swedish exceptionalism regarding far-right populism (e.g. Rydgren & van der Meiden, 2019; Rothstein, 2023; Silander, 2024; V-Dem Institute, 2024, 2025),

- an international role model in climate policy and governance, but is currently implementing new policies increasing GHG emissions (Matti et al., 2021; Widerberg et al., 2024), and

- the home of strong social movements advocating ambitious climate policy, particularly with Greta Thunberg and Fridays for Future (de Moor et al., 2020), which are now increasingly criticised and threatened (Berglund et al., 2024).

- Climate scientists: academic researchers from multiple disciplines studying the causes and effects of global warming, those developing technologies to mitigate and adapt to climate change, as well as those studying responses, actions, policies and measures (including political, economic, technological, discursive, social and behavioural) taken or potentially taken by politicians, business leaders, economists, public organisations, social organisations and people to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

- Climate activists: people who, organised in social climate movements or unorganised, engage in strenuous and and/or risky activities to advocating urgent action to mitigate and adapt to the climate change emergency (cf. Martiskainen et al., 2020; Kirsop-Taylor et al., 2023). They have realised they have to do something to stop climate change, and they see themselves as spokespersons speaking on behalf of potential victims of climate change like themselves but also for those who do not have a voice, particularly children. In that sense, they evolve from victims-to-be to activists in the here-and-now (cf. Vegh Weis & White, 2020). Climate activists included in this study use different strategies, tactics, forums and media to advocate exogenous change of the state and industry, from writing and speaking, via legal demonstrations to disruptive civil disobedience and illegal but non-violent action (cf. Berglund & Schmidt, 2020; Berglund, 2025). Climate activists in this study are all confrontational. Many of them refer to the anthropogenically induced climate change and the resulting climate emergency as ecocide, i.e. unlawful or wanton acts, committed with the knowledge that they are likely to cause widespread, long-term and severe damage to the natural environment (Proedrou & Pournara, 2025).

- Climate journalists: journalists that report on climate change, climate science, climate action and climate politics in news media such as television, radio, podcasts, newspapers, magazines, blogs, books and/or social media.

4.2. Materials

4.3. Data Analysis

5. The Case of Nasty Rhetoric in Swedish Climate Politics

5.1. A Far-Right Populist Takeover

5.2. From Climate Policy Role Model to International Scapegoat

- A Climate Act with a legally binding target that Sweden should have net-zero GHG emissions by 2045, as well as interim targets;

- A requirement in the Climate Act for the government to present to the Riksdag a Climate Action Plan (CAP) with policies and measures to reach the targets, at the latest the calendar year after national elections; and

- Establishment of the Swedish Climate Policy Council (SCPC), an independent and interdisciplinary body of climate scientists, to evaluate the alignment of the government’s policies with the 2045 climate target.

5.3. Use of Nasty Rhetoric in Swedish Climate Politics

6. Emotional and Behavioural Effects on Victims

6.1. Climate Scientists

The development is becoming increasingly threatening. And when you also manage to move the debate in the Riksdag from “what to do about climate change” to “is there climate change” – then you yourself become conspiratorial. Is this some kind of plan? It’s scary.

As an environmental researcher, I have been exposed from various directions. After a wolf debate, I was informed that I live with two red dots on my chest. And in the climate debate over the past ten years, I have received threats that both one and the other measures will be taken to get me rid of my job, in a couple of cases in the last five years also uttered or hinted at by politicians.

I’ve received hate and threats for long. Being criticised in substance is part of being a researcher, that is what brings science forward. But being criticised in person, often related to conspiracy theories, is detrimental. Once, haters threatened to send a death squad to the university. The hatred and threats drain me of energy and to avoid it, I refrain from participating in the public discussion on climate policy.

It’s one thing if someone criticises your selection or method. It can be answered by showing raw data or analyses. Attacks that are directed at you as a person cannot be responded to without abandoning your role as a researcher. And this is something that has become more common. When we published a study in a scientific journal a few years ago that questions Swedish industry practice, several representatives of the industry questioned, among other things, that the paper had not been reviewed for longer than eleven days by the journal. For me, it crosses a red line when high-ranking people in industry and politics, but also colleagues in academia, question the entire validity of the scientific process and academia.

Should one engage in online discussions with science deniers so as not to let them run wild with their messages – or does it affect your credibility as a scientist if you ‘lower’ yourself to the level of trolls?

6.2. Climate Activists

6.2.1. Primary Victimisation

We sit with our signs and try to show our feelings about the climate and the future. We try to reach into people’s hearts and touch them emotionally. We notice that something is happening between us and those who pass by. Older men, often talked about as an obstacle to change, often stop by our sit-ins and are noticeably moved. Sometimes teenage boys have come up and say: ‘Can we sit with you for a while?’ Sit here, we say. It’s a very low threshold in.

I’ve received many death threats and threats of physical violence, both me and my family. The threats to the family are much, much worse. I have also been beaten. In the moment of incitement, I get completely cold. Silent and passive. Afterwards, I can be very sad and disappointed that people can be so cruel. These events have made me more careful when I move around town so as not to be knocked down by someone who recognises me. I’ve also become more afraid that staff and people around a climate action will act violently towards me or my friends.

When politicians throw around concepts such as terrorism and totalitarian forces, I see it as a scare tactic. I'm provoked instead. As a white, well-educated woman, Im quite privileged, so I have a responsibility. Both for my children, but also to not just back down.

We in the small group of radical activists in Restore Wetlands and parts of Extinction Rebellion are strengthened in our conviction and what is required when we have serious allegations about sabotage and terrorism directed at us.

Greenpeace: “We need to talk about democracy, Ulf Kristersson.”

XR: “It’s really, really bad that the prime minister accuses XR of being a security threat instead of taking the climate threat seriously.”

“We are a totally peaceful movement. When the prime minister lied about his own policies during his open after-works, we felt a need to protest in the way we could. The fact that the prime minister is now portraying peaceful children and young people as a security threat is undemocratic.

6.2.2. Secondary Victimisation

When the campaign started, of course, it felt terrible, and I thought at first that it was me who had done something wrong, so then I didn’t feel well. I really liked the Energy Agency and was absolutely horrified that I might have done something that damaged the agency’s reputation, which I absolutely did not want. But then I saw how it was all staged and understood that it wasn’t my fault. After all this, I also very quickly got an assignment, so I got over the bad feeling. This is of course a very serious story. The serious thing is that it shows that society is heading in an undemocratic direction, and that this is part of a tougher climate that affects a lot of people, and also our climate transition work.

The police and prosecutors are often biased in the conflicts we find ourselves in. Reports of environmental crimes, assault, perjury (staff from fossil fuel companies who outright lie in court) are not considered or are immediately dropped. On site, at an action, the police usually have a preconceived idea that we are the ones who are breaking the law. Knowledge of international law and governing conventions is very inadequate.

You never know if and when you’re going to end up in prison. It’s a constant worry and it makes it difficult for me and my family to make longer plans. To avoid this stress, we chose not to appeal the prison sentence and instead serve out the time.

Sometimes the present feels extremely surreal. I alternate between correcting exams and discussing, with both the father of my youngest and my boss, upcoming (one week) absence due to climate lawsuit. At the same time as the planet alternately burns up, sometimes drowns. Difficult to navigate.

We know that our methods work because we measure and analyse the effects. We can also see that petitions and permitted demonstrations have less and less effect, both regarding media space and being able to influence decision-makers. The fact that we in Restore Wetlands have had such a great impact on restoring wetlands and that there is a proposal to ban peat mining on the government’s table shows that we are successful. You have to disturb to be heard and we disturb just enough for it to have an effect.

I will continue regardless of what repression there will be. I have long been willing to take prison sentences because I know that we have to act on climate justice and democracy. The current situation must change.

It is by disturbing that you are seen, heard and get your message out. The rhetoric and acts of far-right populists in power, that there must be no disturbance, is actually to circumscribe the freedom of demonstrations. A demonstration that does not disturb, be seen and heard is not a demonstration. The court case is about democracy, and the threat to it.

I feel insecure about our way of acting; do we dare to rethink or not? But if you look at climate research, what we do is insufficient.

6.3. Science Activists

The task of higher education institutions must include collaborating with the surrounding society for mutual exchange and working to ensure that the knowledge and expertise available at higher education benefits society.

It would be much easier if more scientists and activists dared to take a stance, or at least support others in public. That they agree that the public debate climate is heading in the wrong direction, that you must obey in advance, saying only what some people think is the right thing to say.

It’s frightening, it can result in imprisonment for two years. Risking prison for holding a banner during a demonstration, I would never have thought that was possible in Sweden. I chose to express my opinion for something that I believe is important for improving society. Because of that, I am ultimately denied the right to vote. That does not go together with democracy. There is a strong right to protest in a democracy.

6.4. Civil Servants

It’s sick that this could have happened from the start. But I think I’m a winner somewhere, and if it makes people becoming less afraid, if it becomes more difficult to repress or dismiss people who engage in activism from employment, then this has contributed to something good. We have shown that if you fire people who are committed to the climate issue without reason, then you will be in the newspaper. Even the UN steps in and writes the world’s finest letter. Such strong words! The UN’s letter was to all of us. Not just for me. I’ve come out of this stronger. And now I feel that there has been a point to everything. We have managed to turn a hate campaign into something positive.

We feel that we have to hide, because we are fighting for our children and grandchildren to have a planet that can safely be lived on. That’s the general mood right now.

If you show climate commitment, there will be tougher tests and controls, which does not make it easier for the agency to find qualified aspirants. And, if you show an understanding that people are protesting something through peaceful civil disobedience, you will not pass a security clearance.

I work at a government agency that really works with environmental and climate issues. Every employee and manager know how bad the situation is with climate change. Still, we downplay the external information about how serious it is. There is an anxiety about the political situation—we are giving in before anyone has even demanded it.

6.5. Climate Journalists

While working as a climate journalist, I have been in a storm of hatred, threats and insults. Lies about my person and alleged political affiliation have been glued to me. My feeling of powerlessness has been paralysing at times. I have, to use an old-fashioned word, felt dishonoured. Therefore, I have now resigned as a journalist.

Since 2019, I’ve got several e-mails saying ‘Damn you, I pay your salary and will make sure you’re fired’.

I remember laughing at the first threat that came. It was so banal, such blatant lies. There were five individuals/organisations that over a period of nine months wrote ‘articles’ with lies, several a day. Each article was followed by threats and harassment from their followers. The phone rang non-stop, e-mails were filled up, all social media accounts were sabotaged. It wasn’t really the content that tired me, but the amount... After a couple of months, a death threat came that was so cold and uncomfortably worded that I was really scared, and after that it was hard to stop being afraid. As if something had shifted inside.

People call straight to them and say “you don’t understand anything”. If you’re not confident in your role and about climate change, then you might doubt yourself.

I have camera surveillance outside the door, security door and security glass. Have a note in my wallet with a direct number to a security company, contact to Swedish Security Service. Constant information to relatives what you are doing and encouragement to everyone to be attentive. Life has changed completely. I’m very rarely scared – but I’m damn pissed off! Angry because the whole society has slowly adapted to a new norm where this form of everyday terror has been accepted. And angry for the ineptitude that has spread all the way up to the highest decision-makers.

The reason why anti-climate advocates like to throw the ‘activist’ stamp on a journalist who investigates large companies and the system is because climate policy is potentially subversive. The UN says that we must have rapid change in every sector. Of course, it is dangerous for everyone who wants business-as-usual and for many who are in positions of power. There is a huge interest in criminalising activism.

Compared to media coverage of the Covid-19 pandemic, when a lot of news was given a pandemic angle and the feeling of emergency that we had to change our way of life was present in the newspapers, climate events are presented as news among others.

7. Analysis and Discussion

7.1. Nasty Rhetoric Impacts on Victims

7.1.1. Fear and Angst Make Scientist and Journalist Victims Withdraw

7.1.2. Desensitisation, Anger and ‘Radicalisation’

Come to Grimsås! Borås police station has limited cells. Let’s fill them all! Because we are doing the right things and Neova is a fossil emitter that is going out of our country.

7.1.3. Surreal Exhaustion and Anxiety from Secondary Victimisation

7.1.4. A Culture of Silence

7.2. Resilience of Victims

There may be a loophole in the Swedish constitution implying that a state employee cannot have his or her freedom of expression violated by the state. This opens for the state to arbitrarily get rid of employees based on who sits in the Swedish government at the moment. This creates uncertainty among our members and is a major departure from the system we have, where employees are assessed based on their knowledge and skills.

- with conversations when you are worried and need someone to talk to,

- with information about the legal process and whether you want support in the event of a trial,

- when contacting the authorities and providing information about compensation and damages, and

- offering support to relatives and witnesses.

7.3. Nasty Rhetoric and Crime Victim Discourse

7.3.1. Media Portrayal of Victims

By categorising environmental activism as a potential terrorist threat, by limiting freedom of expression and by criminalising certain forms of protests and protesters, these legislative and policy changes contribute to the shrinking of the civic space and seriously threaten the vitality of democratic societies.

7.3.2. Victims Acknowledging Victimhood

7.3.3. DARVO: Far-Right Populist Reversal of Offender and Victim Roles

prevent terrorism and other ideologically motivated crimes that pose a security threat or that threaten our basic democratic functions, regardless of whether the underlying causes are religious or political. It can be about people, groups and organisations that encourage or use violence, threats and harassment to change society.

That principle is, that the sole end for which mankind is warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.

Instead of a traditional government, we have a right-wing regime led by Sweden Democrats. A regime that uses its position of power to threaten and silence critical voices. /…/ The SD led government destroys what makes Sweden Swedish.

The development is really dangerous. If clear boundaries are not set early, there are no boundaries at all.83

To you in the Elite – politicians, campaign journalists, activists: Do you know? We are not ashamed! It is not us who have destroyed Sweden... It is you who are to blame for it.

7.3.4. Victims and Victimisation in a System of Criminal Acts

7.3.5. Developing the Victim Discourse

We must listen to what they say, not to the narrative portraying climate activists as dangerous criminals. Even if laws are being tightened in almost all countries now and activists are repressed and thrown in prison, we must be critical of the system and not just relate to the law. We must also relate to what is actually scientifically dangerous and what is not.

8. Conclusions

References

- Aalberg, T. & De Vreese, C. (2016) Introduction: Comprehending populist political communication, In: Populist Political Communication in Europe, Aalberg, T., Esser, F., Reinemann, C., De Vreese, C. & Stromback, J. (eds.), London: Routledge; 3-11.

- Abraham, A. (2024). Hating an outgroup is to render their stories a fiction: A BLINCS model hypothesis and commentary, Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 0(0). [CrossRef]

- Abts, K. & Rummens, S. (2007) Populism versus democracy, Political Studies, 55(2), 405-424. [CrossRef]

- Abuín-Vences, N., Cuesta-Cambra, U., Niño-González, J.I. & Bengochea-González, C. (2022) Hate speech analysis as a function of ideology: Emotional and cognitive effects, Comunicar: Media Education Research Journal, 30(71), 35-45. [CrossRef]

- Agius, C., Bergman Rosamond, A. & Kinnvall, C. (2021) Populism, ontological insecurity and gendered nationalism: Masculinity, climate denial and Covid-19, Politics, Religion & Ideology, 21(4), 432-450. [CrossRef]

- Allwood, M., Ghafoori, B., Salgado, C., Slobodin, O., Kreither, J., Waelde, L.C., Larrondo, P. & Ramos, N. (2022) Identity-based hate and violence as trauma: Current research, clinical implications, and advocacy in a globally connected world, Journal of Traumatic Stress, 35(2), 349-361. [CrossRef]

- Alkiviadou, N. (2018) The legal regulation of hate speech: The international and European frameworks, Politička Misao: Croatian Political Science Review¸55(4), 203-229. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=748798.

- Anderson, A.A. & Huntington, H.E. (2017) Social media, science, and attack discourse: How twitter discussions of climate change use sarcasm and incivility, Science Communication, 39(5), 598-620. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M. (2021) The climate of climate change: Impoliteness as a hallmark of homophily in YouTube comment threads on Greta Thunberg’s environmental activism, Journal of Pragmatics, 178, 93-107. [CrossRef]

- Andrewes, D.G. & Jenkins, L.M. (2019) The role of the amygdala and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in emotional regulation: Implications for post-traumatic stress disorder, Neuropsychology Review, 29, 220-243. [CrossRef]

- Arato, A. & Cohen, J.L. (2017) Civil society, populism and religion, Constellations, 24(3), 283-295. [CrossRef]

- Arce-García, S., Díaz-Campo, J. & Cambroneo-Saiz, B. (2023) Online hate speech and emotions on Twitter: a case study of Greta Thunberg at the UN Climate Change Conference COP25 in 2019, Social Network Analysis and Mining, 13, 48. [CrossRef]

- Ardin, A. (2024) Stämplad som demokratiextremist, Stockholm: Forum. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1915084/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Arendt, H. (1971) Thinking and moral considerations: A lecture, Social Research, 38(3), 417-446. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40970069.

- Askanius, T., Brock, M., Kaun, A. & Larsson, A.O. (2024) ‘Time to abandon Swedish women’: Discursive connections between misogyny and white supremacy in Sweden, International Journal of Communication, 18, 5046-5064. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/16808/4840.

- Assimakopoulos, S. (2020) Incitement to discriminatory hatred, illocution and perlocution, Pragmatics and Society, 11(2), 177-195. [CrossRef]

- Assimakopoulos, S., Baider, F. H. & Millar, S. (2017) Online Hate Speech in the European Union, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Atak, K. (2022) Racist victimization, legal estrangement and resentful reliance on the police in Sweden, Social & Legal Studies, 31(2), 238-260. [CrossRef]

- Beirne, P. & South, N. (2007) Introduction: Approaching green criminology, In: Issues in Green Criminology, Beirne, P. & South, N., (eds.), London: Routhledge; xiii-xxii.

- Bell, J.G. & Perry, B. (2014) Outside looking in: The community impacts of anti-lesbian, gay, and bisexual hate crime, Journal of Homosexuality, 62(1), 98-120. [CrossRef]

- Benton, T. (2007) Ecology, community and justice: The meaning of green, In: Issues in Green Criminology, Beirne, P. & South, N., (eds.), London: Routhledge; 3-30.

- Berecz, T. & Devinat, C. (2017) Relevance of cyberhate in Europe and current topics that shape online hate speech, International Network Against Cyber Hate (INACH). Available online: https://www.inach.net/wp-content/uploads/FV-Relevance_of_Cyber_Hate_in_Europe_and_Current_Topics_that_Shape_Online_Hate_Speech.pdf.

- Bergendahl, P. (2025) I Fängelse för Klimatet, Stockholm: BoD.

- Berglund, O. (2025) Disruptive protest, civil disobedience & direct action, Politics, 45(2), 239-257. [CrossRef]

- Berglund, O. & Schmidt, D. (2020) Extinction Rebellion and Climate Change Activism: Breaking the Law to Change the World, London: Palgrave Macmillan. [CrossRef]

- Berglund, O., Brotto, T.F., Pantazis, C., Rossdale, C. & Cavalcanti, R.P. (2024) Criminalisation and Repression of Climate and Environmental Protest, Bristol: University of Bristol. https://bpb-eu-w2.wpmucdn.com/blogs.bristol.ac.uk/dist/f/1182/files/2024/12/Criminalisation-and-Repression-of-Climate-and-Environmental-Protests.pdf.

- Best, J. (1999) Random Violence: How we Talk about New Crimes and New Victims, Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

- Bilewicz, M. & Soral, W. (2020) Hate speech epidemic. The dynamic effects of derogatory language on intergroup relations and political radicalization, Political Psychology, 41(S1), 3-33, . [CrossRef]

- Björkenfeldt, O. (2024) Online Harassment Against Journalists, Dissertation Sociology of Law, Lund, SE: Lund University. https://portal.research.lu.se/en/publications/online-harassment-against-journalists-a-socio-legal-and-working-l.

- Björkenfeldt, O. & Gustafsson, L. (2023) Impoliteness and morality as instruments of destructive informal social control in online harassment targeting Swedish journalists, Language & Communication, 93, 172-187. [CrossRef]

- Blagojev, T., Bleyer-Simon, K., Brogi, E., Carlini, R., Da Costa, D., Borges, L., Kermer, J., Nenadić, I., Palmer, M., Parcu, P.L., Reviglio, U., Trevisan, M. & Verza, S. (2025) Monitoring Media Pluralism in the European Union, San Domenico di Fiesole, IT: European University Institute. https://cadmus.eui.eu/server/api/core/bitstreams/6f582946-bb17-49fc-ab81-9a4b79b4d0ce/content.

- Bleich, E. (2011) The rise of hate speech and hate crime laws in liberal democracies, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 37(6), 917-934. [CrossRef]

- Bleiker, R. (2018) Visual Global Politics, Oxford: Routledge.

- Boeckmann, R.J. & Turpin-Petrosino, C. (2002) Understanding the harm of hate crime, Journal of Social Issues, 58(2), 207-225. [CrossRef]

- Boese, V.A., Lundstedt, M., Morrison, K., Sato, Y. & Lindberg, S.I. (2022) State of the world 2021: Autocratization changing its nature? Democratization, 29(6), 983-1013. [CrossRef]

- Bosma, A., Mulder, E. & Pemberton, A. (2018) The ideal victim through other(s’) eyes, In: Revisiting the “Ideal Victim”: Developments in Critical Victimology, Duggan, M. (ed.), Bristol: Bristol University Press; 27-42.

- Brax, D. (2024) Utsatthet vid svenska universitet och högskolor: En undersökning om trakasserier, hot och våld mot forskare och lärare, Gothenburg, SE: Gothenburg University, Swedish National Secretariat for Gender Research. https://www.gu.se/sites/default/files/2024-12/utsatthet-svenska-hogskolor-universitet-tg.pdf.

- Brisman, A. (2014) Of theory and meaning in green criminology, International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 3(2), 21-34. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/agispt.20142519.

- Brisman, A., & South, N. (2013). A green-cultural criminology: An exploratory outline, Crime, Media, Culture, 9(2), 115-135. [CrossRef]

- Brown, A. (2017) What is hate speech? Part 1: The Myth of Hate, Law and Philosophy, 36, 419-468. [CrossRef]

- Brudholm, T. & Johansen, B.S. (2018) Hate, Politics, Law: Critical Perspectives on Combating Hate, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bsumek, P.K., Schwarze, S., Peeples, J. & Schneider, J. (2019) Strategic gestures in Bill McKibben’s climate change rhetoric, Frontiers in Communication, 4, 40. [CrossRef]

- Burck, J., Uhlich, T., Bals, C., Höhne, N., Nascimento, L., Wong, J., Beaucamp, L., Weinreich, L. & Ruf, L. (2024) Climate Change Performance Index 2025, Bonn: Germanwatch, NewClimate Institute & Climate Action Network. https://ccpi.org/download/climate-change-performance-index-2025/.

- Buzogány, A. & Mohamad-Klotzbach, C. (2022) Environmental populism, In: Oswald, M. (ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of Populism, Cham, CH: Palgrave Macmillan; 321–340.

- Calvert, C. (1997) Hate speech and its harms: A communication theory perspective, Journal of Communication, 47(1), 4-19. [CrossRef]

- Cantrell, D.J. (2019) Love, anger, and social change, Drexel Law Review, 12, 47-92. https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/faculty-articles/1259.

- Cao, A.N. & Wyatt, T. (2016) The conceptual compatibility between green criminology and human security: A proposed interdisciplinary framework for examinations into green victimisation, Critical Criminology, 24, 413-430. [CrossRef]

- Caramani, D. (2017) Will vs. reason: The populist and technocratic forms of political representation and their critique to party government, American Political Science Review, 111(01), 54-67. [CrossRef]

- Cassegård, C. & Thörn, H. (2017) Climate justice, equity and movement mobilization, In: Climate Action in a Globalizing World, Cassegård, C., Soneryd, L., Thörn, H. & Wettergren, Å. (eds.), London: Routledge; 33-56.

- Cassese, E.C. (2021) Partisan dehumanization in American politics, Political Behavior, 43, 29-50. [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Pulgarín, S.A., Suárez-Betancur, N., Tilano Vega, L.M. & Herrera López, H.M. (2021) Internet, social media and online hate speech. Systematic review, Aggression and Violent Behavior, 58, 101608. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborti, N. (2017) Victims of hate crime, In: Handbook of Victims and Victimology, 2nd ed., Walklate, S. (ed.), London: Routledge; 139-154.

- Chang, W.L. (2019) The impact of emotion: A blended model to estimate influence on social media, Information Systems Frontiers, 21, 1137-1151. [CrossRef]

- Chetty, N. & Alathur, S. (2018) Hate speech review in the context of online social networks, Aggression and Violent Behavior, 40, 108-118. [CrossRef]

- Chiew, S., Mayes, E., Maiava, N., Villafaña, D. & Abhayawickrama, N. (2024) Funny climate activism? A collaborative storied analysis of young climate advocates’ digital activisms, Global Studies of Childhood, 14, early view. [CrossRef]

- Christie, N. (1986) The ideal victim, In: From Crime Policy to Victim Policy, Fattah, E.A. (ed.), London: Palgrave Macmillan; 17-30.

- Cohen-Almagor, R. (2018) Taking North American white supremacist groups seriously: The scope and challenge of hate speech on the internet, International Journal for Crime, Justice, and Social Democracy, 7(2), 38-57. [CrossRef]

- Cowan, G. & Hodge, C. (1996) Judgments of hate speech: The effects of target group, publicness, and behavioral responses of the target, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 26(4), 355-374. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, N.C. (2014) Institutionalizing passion in world politics: Fear and empathy, International Theory, 6(3), 535-557. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.T. & Brandt, M.J. (2020) Ideological (A)symmetries in prejudice and intergroup bias, Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 34, 40-45. [CrossRef]

- Crowley, K. & Head, B.W. (2017) The enduring challenge of ‘wicked problems’: revisiting Rittel and Webber, Policy Sciences 50, 53-547. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, K., Hix, S., Dennison, S. & Laermont, I. (2024) A Sharp Right Turn: A Forecast for the 2024 European Parliament Elections, Berlin: European Council on Foreign Relations. https://ecfr.eu/publication/a-sharp-right-turn-a-forecast-for-the-2024-european-parliament-elections/.

- Davies, P.A. (2014) Green crime and victimization: Tensions between social and environmental justice, Theoretical Criminology, 18(3), 300-316. [CrossRef]

- Davies, P. (2018). Environmental crime, victimisation, and the ideal victim, In: Revisiting the “Ideal Victim”: Developments in Critical Victimology, Duggan, M., (ed.), Bristol: Bristol University Press; 175-192.

- Dellagiacoma, L., Geschke, D. & Rothmund, T. (2024) Ideological attitudes predicting online hate speech: the differential effects of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation, Frontiers in Social Psychology, 2, early view. [CrossRef]

- della Porta, D. (2013) Clandestine Political Violence, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- de Moor, J., De Vydt, M., Uba, K. & Wahlström, M. (2020) New kids on the block: Taking stock of the recent cycle of climate activism, Social Movement Studies, 20, 619-625. [CrossRef]

- Dreißigacker, A., Müller, P., Isenhardt, A. & Schemmel, J. (2024) Online hate speech victimization: consequences for victims’ feelings of insecurity, Crime Science, 13, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-024-00204-y Duggan, M. (2018) Introduction, In Revisiting the “Ideal Victim”: Developments in Critical Victimology, Duggan, M., (ed.), Bristol: Bristol University Press; 1-10.

- Dunbar, E. (2006) Race, gender, and sexual orientation in hate crime victimization: Identity politics or identity risk? Violence and Victims, 21(3), 323-337. [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, E.W. (2017) Employing a criterion-based strategy to assess the bias component of hate crime perpetration: Its utility for offender risk assessment and intervention, In: Dunbar, E.W., Blanco, A., Crèvecoeur-MacPhail, D.A., Munthe, C., Fingerle, M. & Brax, D. (eds.), The Psychology of Hate Crime as Domestic Terrorism: U.S. and Global Issues, Praeger: Santa Barbara, CA; 43-102.

- Dunbar, E.W. (2022) The neuroscience of hate and bias ideology: A brain-behavior approach to bias aggression, In: Dunbar, E.W. (ed.), Indoctrination to Hate: Recruitment Techniques of Hate Groups and How to Stop Them, Praeger: Santa Barbara, CA; 176-216.

- Durnová, A. (2018) Understanding emotions in policy studies through Foucault and Deleuze, Politics and Governance, 6(4), 95-102. [CrossRef]

- Earl, J. (2006) Introduction: Repression and the social control of protest, Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 11(2), 129-143.

- Earl, J. (2011) Political repression: Iron fists, velvet gloves, and diffuse control, Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 261-284.

- Earl, J. (2013) Repression and social movements, In: The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements, Snow, D.A., della Porta, D., Klandermans, B. & McAdam, D. (eds.), Malden: Blackwell Publishing; 1083-1089.

- Ekberg, K. & Pressfeldt, V. (2022) A road to denial: Climate change and neoliberal thought in Sweden, 1988–2000, Contemporary European History, 31(4), 627-644. [CrossRef]

- Ergon, J., Hildingsson, R. & Karlsson, M. (2025) Exploring a green Swedish model: Coinciding and contradictory interests on a just climate transformation in Sweden, Ambio 54, 1237-1249. [CrossRef]

- Eubanks, P. (2015) The Troubled Rhetoric and Communication of Climate Change: The Argumentative Situation, London: Routledge.

- European Commission (2021) A more inclusive and protective Europe: extending the list of EU crimes to hate speech and hate crime, Brussels. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:4d768741-58d3-11ec-91ac-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF.

- Farrell, A. & Lockwood, S. (2023) Addressing hate crime in the 21st Century: Trends, threats, and opportunities for intervention, Annual Review of Criminology, 6, 107-130. [CrossRef]

- Ferree, M.M. (2004) Soft repression: Ridicule, stigma, and silencing in gender-based movements, In: Authority in Contention, Myers, D.J. & Cress, D.M. (eds.), Bingley, UK: Emerald; 85-101.

- Fischer, A., Halperin, E., Canetti, D. & Jasini, A. (2018) Why we hate, Emotion Review, 10(4), 309-320. [CrossRef]

- Flam, H. (2005) Emotions’ map, Emotions and Social Movements, Flam, H. & King, D. (eds.), London: Routledge; 19-40.

- Förell, N. & Fischer, A. (2025) Climate backlash and policy dismantling: How discursive mechanisms legitimised radical shifts in Swedish climate policy, Environmental Policy and Governance, 35(4), 615-630. [CrossRef]

- Forst, M. (2024a) Letter from the UN Special Rapporteur on environmental defenders under the Aarhus Convention to the Swedish Government, ACSR/C/2024/39 (Sweden), 16 August 2024, https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2025-02/ACSR_C_2024_Sweden_to_HE_MFA_from_Aarhus_SR_EnvDefenders_complaint_16.08.2024_redacted.pdf.

- Forst, M. (2024b) State repression of environmental protest and civil disobedience: a major threat to human rights and democracy, Position Paper by UN Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders under the Aarhus Convention, February 2024, Geneva: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2024-02/UNSR_EnvDefenders_Aarhus_Position_Paper_Civil_Disobedience_EN.pdf.

- Freyd, J.J. (1997) Violations of power, adaptive blindness and betrayal trauma theory, Feminism & Psychology, 7(1), 22-32. [CrossRef]

- Fridlund, P. (2025) Populism as idea, Statsvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 127(1), 127-148. https://journals.lub.lu.se/st/article/view/27914.

- Frijda, N.H. (1986) The Emotions, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Frijda, N.H. & Mesquita, B. (1994) The social roles and functions of emotions, In: Kitayama, S. & Markus, H.R. (eds.), Emotion and Culture: Empirical studies of mutual influence, Washington, DC American Psychological Association; 51-87. [CrossRef]

- Glad, K.A., Dyb, G., Hellevik, P., Michelsen, H. & Øien Stensland, S. (2023) “I wish you had died on Utøya”: Terrorist attack survivors’ personal experiences with hate speech and threats, Terrorism and Political Violence, 36(6), 834-850. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.M., Hall, K. & Ingram, M.B. (2020) Trump’s comedic gesture as political weapon, In: Language in the Trump Era: Scandals and Emergencies, McIntosh, J. & Mendoza-Denton, N. (eds.), Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 97-123.

- Goodman, J. & Morton, T. (2014) Climate crisis and the limits of liberal democracy? Germany, Australia and India compared, In: Democarcy & Crisis, Isakhan, B. & Slaughter, S. (eds.), London: Palgrave Macmillan; 229-252.

- Green, S. & Pemberton, A. (2017) The impact of crime, In: Handbook of Victims and Victimology, 2nd ed., Walklate, S. (ed.), London: Routledge; 61-86.

- Gruber, A. (2003) Victim wrongs: The case for a general criminal defense based on wrongful victim behavior in an era of victims’ rights, Temple Law Review, 76, 645. https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/faculty-articles/523.

- Grundmann, R. (2016) Climate change as a wicked social problem, Nature Geoscience, 9, 562-563. [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, P. (2024) Angreppet – så urholkar Tidöregeringen vår demokrati, Lund, SE: Arkiv förlag.

- Hagerlid, M. (2020) Swedish women’s experiences of misogynistic hate crimes: The impact of victimization on fear of crime, Feminist Criminology, 16(4), 504-525. [CrossRef]

- Halperin, E., Russell, A., Dweck, C. & Gross, J.J. (2011) Anger, hatred, and the quest for peace: Anger can be constructive in the absence of hatred, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 55(2), 274-291. [CrossRef]

- Halperin, E., Cannetti, D. & Kimhi, S. (2012) In love with hatred: Rethinking the role hatred plays in shaping political behavior, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(9), 2231-2256. [CrossRef]

- Hansen Löfstrand, C. (2009) Understanding victim support as crime prevention work: The construction of young victims and villains in the dominant crime victim discourse in Sweden, Journal of Scandinavian Studies in Criminology and Crime Prevention, 10(2), 120-143. [CrossRef]

- Harnett, N.G., Goodman, A.M. & Knight, D.C. (2020) PTSD-related neuroimaging abnormalities in brain function, structure, and biochemistry, Experimental Neurology, 330, 113331. [CrossRef]

- Harsey, S. & Freyd, J.J. (2020) Deny, attack, and reverse victim and offender (DARVO): What is the influence on perceived perpetrator and victim credibility?, Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 29:8, 897-916, . [CrossRef]

- Harsey, S.J., Adams-Clark, A.A., Freyd, J.J. (2024) Associations between defensive victim-blaming responses (DARVO), rape myth acceptance, and sexual harassment, PLoS ONE, 19(12), e0313642. [CrossRef]

- Haug, M.R. & Sussman, M.B. (1969) Professional autonomy and the revolt of the client, Social Problems, 17(2), 153-161. [CrossRef]

- Hellström, A. (2023) The populist divide in far-right political discourse in Sweden: Anti-immigration claims in the Swedish socially conservative online newspaper Samtiden from 2016 to 2022, Societies, 13(5), 108. [CrossRef]

- Hietanen, M. & Eddebo, J. (2022) Towards a definition of hate speech: With a focus on online contexts, Journal of Communication Inquiry, 47(4), 440-458. [CrossRef]

- (2017) Freedom of Expression and Religious Hate Speech in Europe, London: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Hobson, K. & Niemeyer, S. (2012) “What sceptics believe”: The effects of information and deliberation on climate change scepticism, Public Understanding of Science, 22(4), 396-412. [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, M.J. (2021) The role of worldviews in shaping how people appraise climate change, Current Opinion in Behavioral Science, 42, 36-41. [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.W. (2019) Free speech and hate speech, Annual Review of Political Science, 22, 93-109. [CrossRef]

- Hultman, M., Björk, A. & Viinikka, T. (2019) The far right and climate change denial, In: The Far Right and the Environment: Politics, Discourse and Communication, Forchtner, B. (ed.), London: Routledge; 121-136.

- Hulme, M. (2009) Why We Disagree About Climate Change, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Hunger, S. & Paxton, F. (2022) What’s in a Buzzword? A systematic review of the state of populism research in political science, Political Science Research and Methods, 10(3), 617-633. [CrossRef]

- ICJ (2025) Obligations of States in respect of Climate Change, Press release, 2025/36, The Hague: International Court of Justice. https://www.icj-cij.org/sites/default/files/case-related/187/187-20250723-pre-01-00-en.pdf.

- Ilse, P.B. & Hagerlid, M. (2024) ‘My trust in strangers has disappeared completely’: How hate crime, perceived risk, and the concealment of sexual orientation affect fear of crime among Swedish LGBTQ students, International Review of Victimology, 31(1), 39-58. [CrossRef]

- Incropera, F.P. (2015) Climate Change: A Wicked Problem. Complexity and uncertainty at the intersection of science, economics, politics, and human behavior, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC (2023) Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [CrossRef]

- Izard, C.E. (2010) More meanings and more questions for the term “emotion”, Emotion Review, 2(4), 383-385. [CrossRef]

- Jämte, J. & Ellefsen, R. (2020) The consequences of soft repression, Mobilization: An International Journal, 25(3), 383-404. [CrossRef]

- Jylhä, K.M., Strimling, P. & Rydgren, J. (2020) Climate change denial among radical right-wing supporters, Sustainability, 12(23), 10226. [CrossRef]

- Kalmoe, N. P., Gubler, J. R. & Wood, D. A. (2017) Toward conflict or compromise? How violent metaphors polarize partisan issue attitudes, Political Communication, 35(3), 333–352. [CrossRef]

- Keltner, K., Oatley, K. & Jenkins, J. M. (2014) Understanding Emotions, 3rd ed., London: Wiley.

- Ketola, M. & Odmalm, P. (2023) The end of the world is always better in theory: The strained relationship between populist radical right parties and the state-of-crisis narrative, In: Political Communication and Performative Leadership, Lacatus, C., Meibauer, G. & Löfflmann, G. (Eds.), London: Palgrave Macmillan; 163-177.

- Kinnvall, C. & Svensson, T. (2022) Exploring the populist ‘mind’: Anxiety, fantasy, and everyday populism, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 24(3), 526-542. [CrossRef]

- Kirsop-Taylor, N., Russel, D. & Jensen, A. (2023) A typology of the climate activist, Humanities and Social Science Communications, 10, 896. [CrossRef]

- Klein, E. (2020) Why We’re Polarized, Avid Reader Press: New York.

- Klein, N. (2024) Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World, Toronto: Penguin Random House.

- Klemperer, V. (2002) The Language of the Third Reich: LTI, Lingua Tertii Imperii: A Philologist’s Notebook, London, Continuum.

- Knight, G. & Greenberg, J. (2011) Talk of the enemy: Adversarial framing and climate change discourse, Social Movement Studies, 10(4), 323-340. [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.K., Geiger, S.J., Gellrich, A., Münsch, M., White, M.P. & Pahl, S. (2025) Reasonable or radical? First-order, second-order, and meta-stereotypes of different climate activists among the German public and climate activists, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 104, 102594. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, R. (2014) Climate change: A state-corporate crime perspective, In: Environmental Crime and its Victims, Spapens, T., White, R. & Kluin, M., (eds.), London: Routledge; 21-37.

- Laclau, E. & Mouffe, C. (1985) Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics, London: Verso.

- Laebens, M.G. & Lührmann, A. (2021) What halts democratic erosion? The changing role of accountability, Democratization, 28(5), 908-928. [CrossRef]

- Lahn, B. (2021) Changing climate change: The carbon budget and the modifying-work of the IPCC, Social Studies of Science, 51(1), 3-27. [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.J., Davis, M., & Öhman, A. (2000) Fear and anxiety: Animal models and human cognitive psychophysiology, Journal of Affective Disorders, 61(3), 137-159. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. (1991) Emotion and Adaptation, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Leets, L. (2002) Experiencing hate speech: Perceptions and responses to anti-semitism and antigay speech, Journal of Social Issues, 58(2), 341-361. [CrossRef]

- Lillian, D.L. (2007) A thorn by any other name: Sexist discourse as hate speech, Discourse & Society, 18(6), 719-740. [CrossRef]

- Lindekilde, L. (2014) A typology of backfire mechanisms, In: Dynamics of Political Violence: A Process-Oriented Perspective on Radicalization and the Escalation of Political Conflict, Bosi, L., Demetriou, C. & Malthaner, S. (eds.), Farnham, UK: Ashgate; 51-69.

- Lindvall, D. & Karlsson, M. (2023) Exploring the democracy–climate nexus: A review of correlations between democracy and climate policy performance, Climate Policy, 24, 87-103. [CrossRef]

- Lührmann, A., Gastaldi, L., Hirndorf, D. & Lindberg, S.I. (2020) Defending Democracy Against Illiberal Challengers: A Resource Guide, Gothenburg: V-Democracy Institute/University of Gothenburg. https://www.v-dem.net/documents/21/resource_guide.pdf.

- Lutz, P. (2019) Variation in policy success: radical right populism and migration policy, West European Politics, 42(3), 517-544. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.J. & Long, M.A. (2022) Green criminology: Capitalism, green crime and justice, and environmental destruction, Annual Review of Criminology, 5, 255-276. [CrossRef]

- Malm, A., Ekberg, K., Englund, C., Grønkjær, J.T., Charlier, M., Medin, O. & Holgersen, S. (2025) Green national paradox? How the far right turned Sweden from a (reputed) pioneer of climate mitigation to an obstructor, Political Geography, 122, 103390. [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, J., Oliveira, C. & Lederer, M. (2022) Same, same but different? How democratically elected right-wing populists shape climate change policymaking, Environmental Politics, 31(5), 777-800. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.A., van Prooijen, J.-W. & Van Lange, P.A.M. (2022a) Hate: Toward understanding its distinctive features across interpersonal and intergroup targets, Emotion, 22(1), 46.63. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.A., van Prooijen, J.-W. & Van Lange, P.A.M. (2022b) A threat-based hate model: How symbolic and realistic threats underlie hate and aggression, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 103, 104393. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.A., van Prooijen, J.-W. & Van Lange, P.A.M. (2023) The hateful people: Populist attitudes predict interpersonal and intergroup hate, Social Psychological and Personality Science, 14(6), 698-707. [CrossRef]

- Martiskainen, M., Axon, S., Sovacool, B.K., Sareen, S., Del Rio, D.F. & Axon, K. (2020) Contextualizing climate justice activism: Knowledge, emotions, motivations, and actions among climate strikers in six cities, Global Environmental Change, 65, 102180. [CrossRef]

- Marwick, A.E. (2021) Morally motivated networked harassment as normative reinforcement, Social Media + Society, 7(2), 20563051211021378. [CrossRef]

- Mason-Bish, H. & Duggan, M. (2019) ‘Some men deeply hate women, and express that hatred freely’: Examining victims’ experiences and perceptions of gendered hate crime, International Review of Victimology, 26(1), 112-134. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, M.J. (1989) Public response to racist speech: Considering the victim’s story’, Michigan Law Review, 87, 2320-2381. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, M.J. (1993) Words That Wound: Critical Race Theory, Assaultive Speech, and the First Amendment, Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Matti, S., Petersson, C. & Söderberg, C. (2021) The Swedish climate policy framework as a means for climate policy integration: an assessment, Climate Policy, 21(9), 1146-1158. [CrossRef]

- McBath, J.H. & Fisher, W.R. (1969) Persuasion in presidential campaign communication, Quarterly Journal of Speech, 55(1), 17-25. [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, J. (2020) Introduction: The Trump era as a linguistic emergency, In: Language in the Trump Era: Scandals and Emergencies, McIntosh, J. & Mendoza-Denton, N. (eds.), Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1-44.

- Mchangama, J. & Alkiviadou, N. (2021) Hate speech and the European Court of Human Rights: Whatever happened to the right to offend, shock or disturb? Human Rights Law Review, 21(4), 1008-1042. [CrossRef]

- Mede, N.G. & Schroeder, R. (2024) The “Greta Effect” on social media: A systematic review of research on Thunberg’s impact on digital climate change communication, Environmental Communication, 18(6), 801-818. [CrossRef]

- Meléndez, C. & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2021) Negative partisanship towards the populist radical right and democratic resilience in Europe, Democratization, 28(5), 949-969. [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Denton, N. (2020) “Ask the gays”: How to use language to fragment and redefine the public sphere, In: Language in the Trump Era: Scandals and Emergencies, McIntosh, J. & Mendoza-Denton, N. (eds.), Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 47-51.

- Miller, C.O. & Bloomfield, E.F. (2022) “You can’t be what you can’t see”: Analyzing Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s environmental rhetoric, Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric, 12(1), 1-16. http://contemporaryrhetoric.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Miller_Bloomfield_12_1_1.pdf.

- Moffit, B. (2016) The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Moffitt, B. & Tormey, S. (2013) Rethinking populism: Politics, mediatisation and political style, Political Studies, 62(2), 381-397. [CrossRef]

- Mouffe, C. (2000) The Democratic Paradox, London: Verso.

- Mouffe, C. (2005a) On The Political, London: Routledge.

- Mouffe, C. (2005b) The ‘end of politics’ and the challenge of right-wing populism, In: Populism and the Mirror of Democracy, Panizza, F. (ed.), London: Verso; 50-71.

- Mouffe, C. (2013) Agonistics: Thinking the World Politically, London: Verso.

- Mudde, C. (2004) The populist Zeitgeist, Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541-563. [CrossRef]

- Mudde, C. (2017) Populism: An ideational approach, In: The Oxford Handbook of Populism, Rovira Kaltwasser, C., Taggart, P., Ochoa Espejo, P. & Ostiguy, P. (eds), Oxford: Oxford University Press; 27-47.

- Mudde, C. (2021) Populism in Europe: An illiberal democratic response to undemocratic liberalism, Government and Opposition, 56(4), 577-597. [CrossRef]

- Müller, K. & Schwarz, C. (2020) Fanning the flames of hate: social media and hate crime, Journal of the European Economic Association, 19(4), 2131-2167. [CrossRef]

- Mythen, G. & McGowand, W. (2017) Cultural victimology revisited: Synergies of risk, fear and resilience, In: Handbook of Victims and Victimology, 2nd ed., Walklate, S. (ed.), London: Routledge; 381-395.

- Nobles, M.R. (2019) Environmental and green crime, In: Handbook on Crime and Deviance, 2nd ed., Krohn, M.D., Hendrix, N., Penly Hall, G. & Lizotte, A.J. (eds.), Cham: Springer; 591-601.

- Nordensvärd, J. & Ketola, M. (2022) Populism as an act of storytelling: analyzing the climate change narratives of Donald Trump and Greta Thunberg as populist truth-tellers, Environmental Politics, 31(5), 861-882. [CrossRef]

- Oates, S. & Gibson, R.K. (2006) The Internet, civil society and democracy: A comparative perspective, In: The Internet and Politics: Citizens, Voters and Activists, Oates, S., Owen, D. & Gibson, R.K. (eds.), Abingdon: Routledge; 1-16.

- OECD (2025) OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Sweden 2025, Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, A., Celuch, M., Latikka, R., Oksa, R. & Savela, N. (2022) Hate and harassment in academia: the rising concern of the online environment, Higher Education, 84(3), 541-567. [CrossRef]

- Olivas Osuna, J.J. (2021) From chasing populists to deconstructing populism: A new multidimensional approach to understanding and comparing populism, European Journal of Political Research, 60(4), 829-853. [CrossRef]

- Olson, G. (2020) Love and hate online: Affective politics in the era of Trump, In: Violence and Trolling on Social Media: History, Affect, and Effects of Online Vitriol, Polak, S. & Trottier, D. (eds.), Amsterdam, NL: Amsterdam University Press; 153-178. [CrossRef]

- Oltmann, S.M., Cooper, T.B. & Proferes, N. (2020) How Twitter’s affordances empower dissent and information dissemination: An exploratory study of the rogue and alt government agency Twitter accounts, Government Information Quarterly, 37(3), 101475. [CrossRef]

- Opotow, S. & McClelland, S.I. (2007) The intensification of hating: A theory, Social Justice Research, 20(1), 68-97. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S. (2024) A comparative rhetorical analysis of Trump and Biden’s climate change speeches: Framing strategies in politics, Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, early view. [CrossRef]

- Park, C., Liu, Q. & Kaye, B.K. (2021) Analysis of ageism, sexism, and ableism in user comments on YouTube videos about climate activist Greta Thunberg, Social Media + Society, 7(3), 205630512110360. [CrossRef]

- Paz, M.A., Montero-Díaz, J. & Moreno-Delgado, A. (2020) Hate speech: A systematized review, SAGE Open, 10(4). [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J. & Nogué, S. (2023) Catastrophic climate change and the collapse of human societies, National Science Review, 10(6), nwad082. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.A. (2020) Limiting the capacity for hate: Hate speech, hate groups and the philosophy of hate, Educational Philosophy and Theory, 54(14), 2325–2330. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A. & Wahlström, M, (2015) Repression: The governance of domestic dissent, In: The Oxford Handbook of Social Movements, della Porta, D. & Diani, M. (eds.), Oxford: Oxford University Press; 634-652.

- Piazza, J. A. (2020) Politician hate speech and domestic terrorism, International Interactions, 46(3), 431-453. [CrossRef]

- Pickard, S., Bowman, B. & Arya, D. (2020) “We are radical in our kindness”: The political socialisation, motivations, demands and protest actions of young environmental activists in Britain, Youth and Globalization, 2(2), 251-280. [CrossRef]

- Pretus, C., Ray, J.L., Granot, Y., Cunningham, W.A., Van Bavel, J.J. (2022) The psychology of hate: Moral concerns differentiate hate from dislike, European Journal of Social Psychology, 53(2), 336-353. [CrossRef]

- Proedrou, F. & Pournara, M. (2024) Exploring representations of climate change as ecocide: implications for climate policy, Climate Policy, 25(2), 269-282. [CrossRef]

- Renström, E.A, Bäck, H. & Carroll, R. (2023) Threats, emotions, and affective polarization, Political Psychology, 44(6), 1337-1366. [CrossRef]

- Richardson-Self, L. (2018) Woman-hating: On misogyny, sexism, and hate speech, Hypatia, 33(2), 256-272. doi:10.1111/hypa.12398.

- Ripple, W.J., Wolf, C., Gregg, J.W., Rockström, J., Mann, M.E., Oreskes, N., Lenton, T.M., Rahmstorf, S., Newsome, T.M., Xu, C., Svenning, J.C., Cardoso Pereira, C., Law, B.E. & Crowther, T.W. (2024) The 2024 state of the climate report: Perilous times on planet Earth, BioScience, 74(12), 812-824. [CrossRef]

- Rock, P. (2018) Theoretical perspectives on victimisation, In: Handbook of Victims and Victimology, 2nd ed., Walklate, S. (ed.), London: Routledge; 31-59.

- Rogers, C., Ostarek, M., Nadel, S. & Kenward, B. (2025) What was the impact of the Swedish Restore Wetland campaign? London: Social Change Lab. https://www.socialchangelab.org/restore-wetlands-campaign.

- Roseman, I.J. & Steele, A.K. (2018) Concluding commentary: Schadenfreude, Gluckschmerz, jealousy, and hate – What (and when, and why) are the emotions? Emotion Review, 10(4), 327-340. [CrossRef]

- Röstlund, L. & Urisman Otto, A. (2025) Att Låta Världen Få Veta: Handbok i Klimatjournalistik, Stockholm, SE: Mondial.

- Rothstein, B. (2023) The shadow of the Swedish right, Journal of Democracy, 34(1), 36-49. [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, V. &, South, N. (2013) Green criminology and crimes of the economy: Theory, research and praxis, Critical Criminology, 21, 359-373. [CrossRef]

- Rydgren, J. & van der Meiden, S. (2019) The radical right and the end of Swedish exceptionalism, European Political Science, 18, 439-455. [CrossRef]

- SCPC (2024) Klimatpolitiska rådets rapport 2024, Stockholm: Swedish Climate Policy Council. https://www.klimatpolitiskaradet.se/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/klimatpolitiskaradetsrapport2024.pdf.

- Salmela, M., & von Scheve, C. (2018) Emotional dynamics of right- and left-wing political populism, Humanity & Society, 42(4), 434-454. [CrossRef]

- Sharman, A. & Howarth, C. (2017) Climate stories: Why do climate scientists and sceptical voices participate in the climate debate? Public Understanding of Science, 26(7), 826-842. [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, S., Sülflow, M. & Reiners, L. (2022) Hate speech as an indicator for the state of the society: Effects of hateful user comments on perceived social dynamics, Journal of Media Psychology, 34(1), 3-15. [CrossRef]

- Schlosberg, D. & Collins, L.B. (2014) From environmental to climate justice: Climate change and the discourse of environmental justice, WIREs Climate Change, 5, 359-374. [CrossRef]

- Schulz-Tomančok, A. & Woschnagg, F. (2024) Credibility at stake. A comparative analysis of different hate speech comments on journalistic credibility and support on climate protection measures, Cogent Social Sciences, 10(1), early view. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2024.2367092 Schweppe, J. & Perry, B. (2021) A continuum of hate: Delimiting the field of hate studies, Crime, Law and Social Change, 77, 503-528. [CrossRef]

- Schwöbel-Patel, C. (2018) The ‘ideal’ victim of international criminal law, The European Journal of International Law, 29(3), 703-724. [CrossRef]

- Serafis, D. & Assimakopoulos, S. (2024) Zooming in on the study of soft hate speech: an introduction to this special issue, Critical Discourse Studies, early view, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Shah, T.M. (2024) Emotions in politics: A review of contemporary perspectives and trends, International Political Science Abstracts, 74(1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, K.G., Lawshe, N.L., & McDevitt, J. (2021) Hate crimes in a cross-cultural context, In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice., Pontell, H.N. (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Silander, D. (2024) Problems in Paradise? Changes and Challenges to Swedish Democracy, Leeds, UK: Emerald.

- Simpson, B., Willer, R. & Feinberg, M. (2022) Radical flanks of social movements can increase support for moderate factions, PNAS Nexus, 1(3), pgac110. [CrossRef]

- Skitka, L.J., Bauman, C.W. & Sargis, E.G. (2005) Moral conviction: Another contributor to attitude strength or something more? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(6), 895-917. [CrossRef]

- Sloam, J., Pickard, S. & Henn, M. (2022) Young people and environmental activism: The transformation of democratic politics’, Journal of Youth Studies, 25(6), 683-691. [CrossRef]

- Sloan, L.M., Schmitz, C.L. (2025) Environmental and climate justice: Protecting human and ecological rights, Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, early view. [CrossRef]

- Slotta, J. (2020) The significance of Trump’s incoherence, In: Language in the Trump Era: Scandals and Emergencies, McIntosh, J. & Mendoza-Denton, N. (eds.), Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 52-62.

- Soral, W., Bilewicz, M., & Winiewski, M. (2018) Exposure to hate speech increases prejudice through desensitization, Aggressive Behavior, 44, 136-146. [CrossRef]

- South, N. (2014) Green criminology: Reflections, connections, horizons, International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 3(2), 5-20. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/informit.270196734841610.

- Smith, R. (2020) The three-process model of implicit and explicit emotion, In: Lane, R.D. & Nadel, L. (eds.), Neuroscience Enduring Change, Oxford: Oxford Academic; 25-55. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190881511.003.0003 Spapens, T. (2014) Invisible victims: The problems of policing environmental crime, In: Environmental crime and its victims: Perspectives within green criminology, Spapens, T., White, R. & Kluin, M., (eds.), London: Routledge; 221-236).

- Sponholz, L. (2018) Hate Speech in den Massenmedien: Theoretische Grundlagen und empirische Umsetzung, Wiesbaden: Springer.

- ST (2021) Tyst Stat, Stockholm: Fackförbundet ST. https://editorial.st.org/sites/default/files/2022-06/tyst_stat_en_rapport_om_den_hotade_oppenheten_i_statlig_forvaltning.pdf.

- Stephan, W.G. & Stephan, C.W. (2017) Intergroup threats, In: Sibley, C.G. & Barlow, F.K. (eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of the Psychology of Prejudice, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 131-148. [CrossRef]

- Stephan, W.G., Ybarra, O. & Morrison, K. (2009) Intergroup threat theory, In: Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination, Nelson, T. (ed.), Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 43-60.

- Sternberg, R.J. & Sternberg, K. (2008) The Nature of Hate, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Strömbäck, J., Wikforss, Å., Glüer, K., Lindholm, T. & Oscarsson, H. (2022) Knowledge Resistance in High-Choice Information Environments, New York, NY: Routledge.

- Svatoňová, E., & Doerr, N. (2024) How anti-gender and gendered imagery translate the Great Replacement conspiracy theory in online far-right platforms, European Journal of Politics and Gender, 7(1), 83-101. [CrossRef]

- Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (2024) Naturvårdsverkets underlag till regeringens klimatredovisning 2024, Stockholm. https://www.naturvardsverket.se/49732a/globalassets/amnen/klimat/klimatredovisning/naturvardsverkets-underlag-till-regeringens-klimatredovisning-2024.pdf.

- Swedish Police Authority (2022) Hatbrott och andra brott som hotar demokratin, Stockholm. https://polisen.se/contentassets/1aef051c07884399bc909999a11d6a90/rapport-hatbrott-och-andra-brott-som-hotar-demokratin---delredovisning-1.pdf/.

- TCO (2025) Tyst Förvaltning, Stockholm: Tjänstemännens Centralorganisation. https://tco.se/media/kpclvdtf/tco_rapport_tyst-fo-rvaltning.pdf.

- Tham, H., Rönneling, A. & Rytterbro, L.L. (2011) The emergence of the crime victim: Sweden in a Scandinavian context, Journal of Crime and Justice, 40, 555-610. [CrossRef]

- Thörn, H. & Svenberg, S. (2016) ‘We feel the responsibility that you shirk’: Movement institutionalization, the politics of responsibility and the case of the Swedish environmental movement, Social Movement Studies, 15(6), 593-609. [CrossRef]

- Tidö Parties (2022) Tidöavtalet: En överenskommelse för Sverige (Tidö Agreement: An agreement for Sweden), 14 October 2022, Tidö, SE: Moderaterna, Kristdemokraterna, Liberalerna, Sverigedemokraterna. https://www.liberalerna.se/wp-content/uploads/tidoavtalet-overenskommelse-for-sverige-slutlig.pdf.

- Tom Tong, S. (2025) Foundations, definitions and, directions in online hate research, In: Social Processes of Online Hate, Walther, J.B. & Rice, R.E. (eds.), Oxon: Routledge; 37-72s.

- Törnberg, P. & Chueri, J. (2025) When do parties lie? Misinformation and radical-right populism across 26 countries, The International Journal of Press/Politics, early view. [CrossRef]

- Tsesis, A. (2009) Dignity and speech: The regulation of hate speech in a democracy, Wake Forest Law Review, 44, 497. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm?abstractid=1402908.

- V-Dem Institute (2024) Democracy Winning and Losing at the Ballot: Democracy Report 2024, Gothenburg, SE: University of Gothenburg. https://v-dem.net/documents/43/v-dem_dr2024_lowres.pdf.

- V-Dem Institute (2025) Democracy Report 2025: 25 Years of Autocratization – Democracy Trumped? Gothenburg, SE: University of Gothenburg. https://v-dem.net/documents/61/v-dem-dr__2025_lowres_v2.pdf.

- Vahter, M. & Jakobson, M.L. (2023) The moral rhetoric of populist radical right: The case of the Sweden Democrats, Journal of Political Ideologies, early view. [CrossRef]

- van Doorn, J. (2018). Anger, feelings of revenge, and hate, Emotion Review, 10(4), 321-322. [CrossRef]

- van Doorn, J., Zeelenberg, M. & Breugelmans, S.M. (2014) Anger and prosocial behavior, Emotion Review, 6(3), 261-268. [CrossRef]

- Vargiu, C., Nai., A. & Valli, C. (2024) Uncivil yet persuasive? Testing the persuasiveness of political incivility and the moderating role of populist attitudes and personality traits, Political Psychology, early view. [CrossRef]

- Vegh Weis, V. & White, R. (2020) Environmental victims and climate change activists, In: Victimology: Research, Policy and Activism, Tapley, J. & Davies, P., (eds), Cham: Palgrave Macmillan; 301-319.

- Vergani, M., Perry, B., Freilich, J., Chermark, S., Scrivens, R, Link, R., Kleinsman, D., Betts, J. & Iqbal, M. (2024) Mapping the scientific knowledge and approaches to defining and measuring hate crime, hate speech, and hate incidents: A systematic review, Campbell Systematic Reviews, 20(2), e1397. [CrossRef]

- Vihma, A., Reischl, G. & Andersen, A.N. (2021) A climate backlash: Comparing populist parties’ climate policies in Denmark, Finland, and Sweden, The Journal of Environment & Development, 30(3), 219-239. [CrossRef]

- Vowles, K. & Hultman, M. (2021a) Dead white men vs. Greta Thunberg: Nationalism, misogyny, and climate change denial in Swedish far-right digital media, Australian Feminist Studies, 36(110), 414-431. [CrossRef]

- Vowles, K. & Hultman, M. (2021b) Scare-quoting climate: The rapid rise of climate denial in the Swedish far-right media ecosystem, Nordic Journal of Media Studies, 3(1), 79-95. [CrossRef]

- Vowles, K., Ekberg, K. & Hultman, M. (2024) Climate obstruction in Sweden, In: Climate Obstruction across Europe, Brulle, R.J., Roberts, T. & Spencer, M.C. (eds.), Oxford: Oxford University Press; 109-135.

- von Malmborg, F. (2024a) Strategies and impacts of policy entrepreneurs: Ideology, democracy, and the quest for a just transition to climate neutrality, Sustainability, 16(12), 5272. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. (2024b) Tapping the conversation on the meaning of decarbonization: Discourses and discursive agency in EU politics on low-carbon fuels for maritime shipping, Sustainability, 16(13), 5589. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. (2024c) Vem tar ansvar för klimaträttvisan? Dagens ETC, 26 August 2024. https://www.etc.se/debatt/vem-tar-ansvar-foer-klimatraettvisan.

- von Malmborg, F. (2024d) Hat och hot hör ihop i politisk retorik, Magasinet Konkret, 28 October 2024. https://magasinetkonkret.se/hat-och-hot-hor-ihop-i-politisk-retorik/.

- von Malmborg, F. (2025) Weird sporting with double edged swords: Understanding nasty rhetoric in Swedish climate politics, Humanities and Social Science Communications. [CrossRef]

- Wachs, S. Gámez-Guadix, M. & Wright, M.F. (2022) Online hate speech victimization and depressive symptoms among adolescents: The protective role of resilience, Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 25(7). [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M. & Morisi, D. (2019) Anxiety, fear and political decision making, Oxford Research Encyclopedias Online: Politics. [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, M. & Uba, K. (2024) Political icon and role model: Dimensions of the perceived ‘Greta effect’ among climate activists as aspects of contemporary social movement leadership, Acta Sociologica, 67(3), 301-316. [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, M., Törnberg, A. & Ekbrand, H. (2021) Dynamics of violent and dehumanizing rhetoric in far-right social media, New Media & Society, 23(11), 3290-3311. [CrossRef]

- Walklate, S. (2017) Introduction and overview, In: Handbook of Victims and Victimology, 2nd ed., Walklate, S. (ed.), London: Routledge; 1-8.

- Walther, J.B. (2025) Making a case for a social processes approach to online hate, In: Social Processes of Online Hate, Walther, J.B. & Rice, R.E. (eds.), Oxon: Routledge; 9-36.

- Weeks, A.C. & Allen, P. (2023) Backlash against “identity politics”: far right success and mainstream party attention to identity groups, Politics, Groups, and Identities, 11(5), 935-953. [CrossRef]

- Weintrobe, S. (2021) Psychological Roots of the Climate Crisis: Neoliberal Exceptionalism and the Culture of Uncare, New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Weise, Z. & Camut, N. (2025) Let’s kill the Green Deal together, far-right leader urges EU’s conservatives, Politico, 27 January 2025. https://www.politico.eu/article/lets-kill-eu-green-deal-together-france-far-right-leader-tells-center-right-jordan-bardella/.

- Whillock, R.K. & Slayden, D. (1995) Hate Speech, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- White, R. (2011) Transnational Environmental Crime: Toward an Eco-Global Criminology, Abingdon: Routledge.

- White, R. (2018) Climate Change Criminology, Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- White, M. (2021) Greta Thunberg is ‘giving a face’ to climate activism: Confronting anti-feminist, anti-environmentalist, and ableist memes, Australian Feminist Studies, 36(110), 396-413. [CrossRef]

- White, J. (2023) What Makes Climate a Populist Issue? Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment Working Paper 401, London: London School of Economics and Political Science. https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/working-paper-401-White.pdf.

- WHO (2021) COP26 special report on climate change and health: the health argument for climate action, Geneva: World Health Organisation. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514972.

- WHO (2023) Climate Change, Geneva: World Health Organisation. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health.

- Widerberg, O., Bäckstrand, K., Marquardt, J. & Nasiritousi, N. (2024) Sweden’s emissions and climate policy in an international context, In: The Politics and Governance of Decarbonization: The Interplay between State and Non-State Actors in Sweden, Bäckstrand, K., Marquardt, J., Nasiritousi, N. & Widerberg, O. (eds.), Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 41-62.

- Widfeldt, A. (2023) The far-right Sweden, In: The Routledge Handbook of Far-Right Extremism in Europe, Kondor, K. & Littler, M. (eds.), London: Routledge; 193-206.

- Wypych, M. & Bilewicz, M. (2024) Psychological toll of hate speech: The role of acculturation stress in the effects of exposure to ethnic slurs on mental health among Ukrainian immigrants in Poland, Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 30(1), 35-44. [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, F. (2012) Right-wing hegemony and immigration: How the populist far-right achieved hegemony through the immigration debate in Europe, Current Sociology, 60(3), 368-381. [CrossRef]

- Yong, C. (2011) Does freedom of speech include hate speech? Res Publica, 17, 385-403. [CrossRef]

- Zeitzoff, T. (2023) Nasty Politics: The Logic of Insults, Threats and Incitement, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zick, A., Wolf, C., Küpper, B., Davidov, E., Schmidt, P. & Heitmeyer, W. (2008) The syndrome of group-focused enmity: The interrelation of prejudices tested with multiple cross-sectional and panel data, Journal of Social Issues, 64(2), 363-383. [CrossRef]

| Type of nasty rhetoric, hate speech/crime | Type of repression | Description | Level of aggression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insults | Soft | Name-calling, including ridicule, hyperbole and caricature, that influences how people make judgement and interpret situations. Could sometimes include dehumanising and enmity rhetoric. | Hate |

| Accusations | Soft | Blaming opponents of doing something illegal or shady, or promulgating conspiracy theories about opponents, e.g. through hyperbole, caricature, exclusion or ejection. | Hate |

| Intimidations | Hard | Veiled threats advocating economic or legal action against an opponent, e.g., that they should get fired, be investigated or sent to prison. | Threat (psychological violence) |

| Incitements | Hard | The most aggressive type of rhetoric includes people threatening or encouraging sometimes fatal violence against opponents. If the statement is followed, which happens, it implies physical harm to, or in the worst case, death of opponents. | Threat (psychological violence) |

| Sanctions (repression) | Hard | Denunciation, detention, fines, imprisonment | Economic or legal violence |

| Physical violence | Hard | Assault, beating, rape, murder. | Physical violence |

| Activist | Crime | Emotion | Polarisation | Scientist |

| Aggression | Dehumanise | Fear | Politics | Silence |

| Anger | Democracy | Hate | Prison | Terrorist |

| Antidemocratic | Depression | Insecurity | Repression | Threat |

| Anxiety | Disappear | Journalist | Research | Violence |

| Type of media | Media source | No. of sources |

|---|---|---|

| Newspapers and magazines | Sub total | 107 |

| Aftonbladet (independent social democrat) | 16 | |

| Aktuell Hållbarhet (independent, green business) | 1 | |

| Altinget (independent) | 2 | |

| Arbetet (independent social democrat) | 1 | |

| Arbetsvärlden (labour union journal) | 1 | |

| Dagens Arena (independent progressive newspaper) | 2 | |

| Dagens ETC (independent left) | 12 | |

| Dagens Nyheter (independent liberal) | 37 | |

| Expressen (independent liberal) | 5 | |

| Fokus (independent right-wing) | 3 | |

| Fria Tider (far-right populist) | 1 | |

| Frihetsnytt (far-right populist) | 1 | |

| GöteborgsPosten (independent liberal) | 3 | |

| Läget (independent newspaper, published by students in journalism at Stockholm university) | 1 | |

| Landets Fria Tidning (independent green) | 1 | |

| Magasinet Konkret (independent liberal democratic) | 4 | |

| Publikt (journal of labour union for state employees) | 2 | |

| Riks (semi-independent far-right (SD)) | 1 | |

| Samnytt (independent far-right populist) | 1 | |

| SN Södermanlands Nyheter (independent social liberal) | 1 | |

| Svenska Dagbladet (independent conservative) | 10 | |

| Sveriges Natur (magazine of the Swedish Society for Nature Conservation) | 1 | |

| Tidningen Global (independent green liberal) | 1 | |

| Tidningen Syre (independent green liberal) | 10 | |

| Blogs | Sub total | 7 |

| Anna from the Swedish Energy Agency (personal) | 1* | |

| IFJ Blog (International Federation of Journalists) | 1 | |

| Klimataktion (climate activist) | 1 | |

| Motargument (independent green-left) | 1 | |

| Smedjan (independent libertarian, Timbro) | 1 | |

| Supermiljöbloggen (independent green deliberative) | 2 | |

| Podcasts | Sub-total | 4 |

| Statshemligheter (Podcast of ST, labour union for civil servants in the state) | 2 | |

| Två klimatpsykologer möter (Podcast by two professional climate psychologists) | 1 | |