1. Climate Change, Wicked Problems and Politics of Emotions

1.1. Climate Change—A Super Wicked Problem

Could one imagine a more wicked problem

(Rittel & Webber, 1973) than climate change? The scope, viable responses,

and appropriate mechanisms and pathways towards achieving improvement regarding

climate change mitigation are complex and uncertain, and appear at the

intersection of science, economics, politics, and human behaviour (Incropera, 2015;

Grundmann, 2016). Wicked problems are inherently societal and cut across

temporal, geographical and value related dimensions, for which, in pluralistic

societies with diverse interests, traditions and values there is seldom

consensus on the problem and potential solutions (Crowley & Head, 2017).

The social context in which climate change is framed makes ideological, ethical

and religious beliefs and worldviews important in public discourse and

policymaking (Incropera, 2015; Hornsey, 2021). Besides different views on

solutions, the social context also impacts the perception of climate change as

a problem at all, with the existence of climate change deniers and sceptics

questioning that climate change takes place and thus the need for climate

change policy (Sharman & Howarth, 2017; Hultman et al., 2019; Lewandowsky,

2021; Vowles & Hultman, 2021a, 2021b; Ekberg & Pressfeldt, 2022).

Recognising the difficulties in agreeing on framing and formulating problems

and viable solutions, climate change has even been called a super wicked

problem (Lazarus, 2008; Levin et al., 2012).

1.2. Climate Politics as Politics of Emotions

The witnessing of climate change events like more

frequent and extreme rains, storms, floodings, landslides, heatwaves, droughts

and wildfires, and their negative impacts on people, societies and economies

all over the world (Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change, 2023) make a lot of people emotionally affected

(Brosch, 2021; Howe, 2021; Schneider et al., 2021). World leaders, including

the UN Secretary General (UNSG) António Guterres and President of the European

Commission Ursula von der Leyen, as well as climate activists talk about a

climate emergency. People like Greta Thunberg, the figurehead number one of the

climate justice movement, find an emotionally and ideologically motivated

identity in being climate justice activists, devoting their work or leisure

time to advocate for strong climate policy (Masson & Fritsche, 2021).

Having worked with national, EU and global climate policy and governance as

non-political policy officer and deputy director in the Swedish Government

Offices for more than 15 years, I know that many colleagues in Sweden, the EU

and globally started working with climate change to help save the world.

Politics, including climate politics, is emotional

(Beattie et al., 2019; Shah, 2024). This is not a new phenomenon. It is long

since known that emotions are important to political behaviour. Emotions

influence action tendencies because they inform an individual about a situation

and prepare the body for a certain course of action (Frijda, 1986). Emotions

are modes of relating to the environment: states of readiness for engaging, or

not engaging, in interaction with that environment (Frijda & Mesquita, 1994;

Keltner et al., 2014). The role of emotions for shaping climate policy was

highlighted in the first party leader debate after the Swedish general

elections in 2022 (von Malmborg, 2025a). The leader of the far-right populist

party Sweden Democrats (SD) claimed that the previous Social Democrat

(S) and Green Party (MP) government, together with the Left Party

(V) and the Centre Party (C) were emotional on climate policy, not

basing it on facts, and that everything was about the children and what

children think. In a similar vein, the current prime minister (PM) of Sweden,

representing the conservative Moderate Party (M), claimed in the same

debate that the symbol politics of the previous red–green government will be

replaced by things that have a real effect. In essence, they claimed that

climate policy should not be based on emotions, but being technically-economically

rational.

However, climate politics and climate policy may

not only be

based on emotions. It can also be shaped to

invoke

emotions. Analysing the strategic agency of the new right-wing government

in the radical transformation of Swedish climate policy since 2022, von

Malmborg (2024a) identified systematic use of emotional hate speech such as

insults, accusations, denigration and in rare cases violence, targeting

advocates of strong climate policy. It was a tactic of leading politicians,

including the PM and cabinet ministers of the right-wing government, supported

by SD, to use such

nasty politics with

nasty rhetoric (Zeitzoff,

2023) to discredit oppositional politicians and to delegitimise and dehumanise

climate scientists, climate activists and climate journalists to make them

silent and disappear from the climate policy debate (von Malmborg, 2024b,

2024c). A leading Swedish newspaper recently described Swedish climate politics

as “a musty rant with accusations of betrayal, sin and devil pacts”.

1

Use of nasty rhetoric, including hate speech and

hate crime, as a tactics in strategic agency of far-right populists is

well-known in policy domains such as migration and identity policy (see e.g.

Yılmaz, 2012; Lutz, 2019; Peters, 2020; Weeks & Allen, 2023; Svatoňová

& Doerr, 2024). For instance, members of the Jewish diaspora, the Muslim

community and the LGBTQi communities in EU countries are victimised by online

hate speech on an almost daily basis (Berecz & Devinat, 2017). It is now

used also to polarise climate politics in a culture war (Cunningham et

al., 2024) to demount national climate policy and governance in line with

far-right populist whims (von Malmborg, 2024a). This is a dangerous development

that counters the need for pluralistic approaches to democratic governance of

climate change (Newell, 2008; Goodman & Morton, 2014; Pickering et al.,

2020; Lindvall & Karlsson, 2023) as a truly wicked problem.

Research on hate speech and nasty rhetoric in

climate politics has mainly focused on its polarising role (e.g. Eubanks, 2015;

Bsumek et al. 2019; Pandey, 2024), and hate campaigns towards specific groups

of targets, such as the climate justice movement (Agius et al., 2021;

Andersson, 2021; White, 2022; Arce-García et al., 2023) and climate journalists

(Björkenfeldt & Gustafsson, 2023; Schulz-Tomančok & Woschnagg, 2024).

The latter has shown that anti-climate rhetoric is often intersected with anti-feminism

(Andersson, 2021; Vowles & Hultman, 2021a; White, 2022; Arce-García et al.,

2023), resulting in female activists and journalists being victimised more

often and more aggressively. Less is known about the use and harms of nasty

rhetoric as strategy and tactics in radically changing climate politics and

governance.

The strategic use of nasty rhetoric in climate

politics, as seen from the perpetrators’ perspectives—the initiators and the

followers—was recently analysed by von Malmborg (2025a). He suggests that nasty

rhetoric is a double-edged sword to initiators, aimed at silencing

opponents in the outgroup, but also at mobilising ingroup followers to expand

nasty rhetoric. To the followers, nasty rhetoric can be described as a weird

kind of sport. Sociological research has found that followers in nasty

rhetoric and hate speech spread hate and threats in social media for reasons of

social gratification, including as entertainment and having fun (Walther,

2025). The resulting emotional, cognitive and behavioural harms of nasty

rhetoric in climate politics on different groups of victims was analysed by von

Malmborg (2025b), finding that climate scientists and journalists are targeted

with more aggressive hate speech than climate activists. The former are more

often receiving threats of physical violence and death threats. To victims, nasty rhetoric is perceived as asynchronous

or coordinated swarms of instants that keep coming in a vertical

temporality (von Malmborg, 2025c). It leaves many victims with fear of crime

and anxiety from not knowing when life will go normal. They resign or stay

silent in the public policy debate. Nasty rhetoric also ignites anger, a holy

wrath, radicalising some victims. Not to turn violent,

but to intensify peaceful protests to pursue their science-based argumentation

for strong climate policy. Thus, nasty rhetoric victimisation can also be

seen as a traffic cone (von Malmborg, 2025c) Some victims hide in the

wide end and turn silent, others use it to speak louder to backfire on the

perpetrators of nasty rhetoric.

1.3. Aim of the Paper

Given that emotion laden nasty rhetoric in Swedish

climate politics is found to be part of a strategy for radical change of

climate policy and governance (von Malmborg, 2024a)—an iconoclastic paradigm

shift—this paper aims to explore and explain the wider effects on democracy of

nasty rhetoric in climate politics as a specific case of emotional politics of

wicked problems. The following research questions are addressed:

How is democracy affected by nasty rhetoric targeting climate scientists?

How is democracy affected by nasty rhetoric targeting climate journalists?

How is democracy affected by nasty rhetoric targeting climate activists?

In this paper, climate scientists refer to

academic researchers studying the causes and effects of global warming, those

developing technologies to mitigate and adapt to climate change, as well as

those studying responses, actions, policies and measures (including political,

economic, technological, social and behavioural) taken or that could or should

be taken by politicians, business leaders, economists, public organisations,

social organisations and people to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Climate

activists refer to people who, organised in climate movements or

unorganised, participate in the public debate advocating a need for urgent

action to mitigate and adapt to the climate change emergency. Climate

journalists refer to journalists that report on climate change, climate

science, climate action and climate politics in news media.

Since Zeitzoff’s theory of nasty politics is mainly

developed to explore and explain nasty rhetoric between oppositional

politicians (see section 2), the paper will also contribute to development of

the theory on nasty politics and nasty rhetoric, including other groups of

actors in society and politics.

The paper is outlined as follows.

Section 2 presents the theory of nasty rhetoric

and emotional governance, as well as findings from the literature on harms of

nasty rhetoric and related areas such as hate speech, cyberhate and hate crime.

Section 3 presents the method and

material used to analyse nasty rhetoric in the case of Swedish climate

politics.

Section 4 presents the case

study, while section 5 presents and discusses different harms on democracy,

including the Swedish debate on whether or not to ban nasty rhetoric. While

left-liberal politicians and debaters call for its ending, far-right populists

and libertarians claim that a ban on nasty rhetoric would restrict freedom of

expression. Contributing to the overall theme of this special issue, section 6

draws conclusions on the politics of emotions in governance of wicked problems.

The analysis and discussion draw on a broad literature to grasp the many

aspects and layers of nasty rhetoric and its harm on democracy, ranging from

political science, sociology and law studies to philosophy, history of religion

and history of arts.

2. Theory of Nasty Rhetoric

The concept of nasty politics was introduced

by Zeitzoff (2023, p. 6) to describe the phenomenon when politicians use “a set

of tactics […] to insult, accuse, denigrate, threaten and in rare cases

physically harm their domestic political opponents”, which can include

“political parties, partisans, ethnic groups, police and security services,

immigrants, judges, businessmen, companies, journalists, members of the press,

NGOs, government officials, military, business groups, or other domestic

political opponents broadly construed” (Zeitzoff, 2023, p. 9). The core of

nasty politics is the use of nasty rhetoric, characterised by divisive

and contentious rhetoric with insults and threats containing elements of hatred

and aggression that entrenches political divides vith ‘us vs. them’ narratives,

i.e. polarisation (Klein, 2020), designed to denigrate, deprecate,

delegitimise, dehumanise and hurt their target(s) to make them silent (Kalmoe

et al., 2018). Nasty rhetoric can be used in “campaign rallies, speeches, via

social media or face-to-face in debates or in actual violent confrontations”

(p. 6).

In that sense, nasty rhetoric covers offline and

online hate speech (the latter often referred to as cyberhate) as well as hate

crime (Whillock & Slayden, 1995; Chetty & Alathur, 2018;

Castaño-Pulgarín et al., 2021; Vergani et al., 2024). Hate crime can be defined

as “a crime motivated by prejudice and discrimination that stirs up a group of

like-minded people to target victims because of their membership of a social

group, religion or race” (Peters, 2022, p. 2326). In comparison, there is a spectrum

of definitions of hate speech, reflecting the jurisprudence in different

polities (Assimakoupoulos et al., 2017; Hietanen & Eddebo, 2022). Media

scientist Sponholz (2018, p. 51) defines hate speech as “the deliberate and

often intentional degradation of people through messages that call for, justify

and/or trivialise violence based on a category (gender, phenotype, religion or

sexual orientation)” (my translation). As such, hate speech is not restricted

to speech acts, but also encompasses, e.g., image-based communication and can

be unintentional. Zeitzoff (2023) has proposed a typology of nasty rhetoric, to

which economic and legal violence, e.g. repression, has been added since it is

increasingly used against climate activists in Europe (

Table 1).

As described by Zeitzoff

(2023), different types of nasty rhetoric do not happen in isolation, but tend

to happen together, with more threatening and aggressive rhetoric happening

alongside less aggressive rhetoric. Social psychology research on hate,

described as a strong, intense, enduring, and destructive emotional experience

intended to harm or eliminate its targets physically, socially, or symbolically

(Fischer et al., 2018; Martínez et al., 2022a; Opotow & McClelland, 2007),

finds a causal relationship between hate and aggression in terms of aggressive

tendencies and hurting behaviour experienced towards specific individuals and

entire outgroups (Martínez et al., 2022b). What starts with different

expressions of hate soon escalates to different forms of threats, one more aggressive

than the other, and further to violence.

Deprecation, i.e. insults and accusations to make

claims about action, may be a precursor to more targeted violent rhetoric and

action, and act as a provocation and incitement to addressees and bystanders as

much as emotional sentiments that wound the targets of a speech, text, picture

or video. As for violence, “speech can and does inspire crime” (Cohen-Almagor

et al., 2018, p. 38; Schweppe & Perry, 2021). As stated by Maria Ressa,

Nobel Peace Prize laureate in 2021:

2

Online violence does not stay online. Online violence leads to real world violence.

Thus, hate speech is also seen as a type of

terrorism or trigger event of terrorism, i.e. any intentional act directed

against life or related entities causing a common danger (Chetty & Alathur,

2018; Piazza, 2020a).

2.1. Nasty Rhetoric and Far-Right Populism

Far-right populist parties have increased their

votes in every election to national parliaments in Europe since the 1980s and

autocratisation is increasing (Mudde, 2004, 2021; V-Dem Institute, 2024). Recently, far-right populist “insulter in chief” Donald

Trump (Vargiu et al., 2024) was inaugurated as President of the USA a second

time. To reach their political aims, populists disseminate conspiracy

theories about the state of society and use incivil and nasty rhetoric with coarse, rude, and disrespectful language (Moffitt & Tormey, 2013; Moffitt, 2016; Lührmann et

al., 2020; Mudde, 2021; Zeitzoff, 2023; Törnberg & Chueri, 2025).

Dellagiacoma et al. (2024) report that people adhering to right-wing

authoritarianism are significantly more likely to produce online hate than

people with a social liberal orientation.

Narratives of ‘disaster’ or ‘anxiety’ are important

for the success of far-right populists (Kinnvall & Svensson, 2022). These

refer to a fictional fantasy of a constant crisis, rather than an actual crisis

of the nation, caused by long-term mismanagement by a corrupt ‘elite’ (Kinnvall

& Svensson, 2022; Ketola & Odmalm, 2023; Abraham,

2024). Entrenching an ‘us vs. them’ narrative, far-right populists refer to

a homogeneous ‘people’, the popular (the ingroup), as a counterpoint to the

‘elite’ (the outgroup). They portray themselves as the saviour of the nation

and the people, and they claim that the ‘elite’ should be punished for their

crimes against the ‘people’. The notion of ‘people’, the central tenet of

populism, is constructed and sustained through the stories of peoplehood told

by political leaders (Smith, 2003), often linked to an emotional response

(Koschorke & Golb, 2018).

In political science, populism, either left or

right, is seen as a thin ideology, which largely lacks in content beyond its

distinction between the pure people and the corrupt elite (Mudde, 2004). The

populist argument is therefore based on politics as an “expression of the volonté

générale (general will) of the people” (Mudde, 2004, p. 543). While

sometimes talking the language of the ‘people’, populists are not responsive to

popular will. Their political stance is based on a unitary and non-pluralist

vision of society’s public interest, and they themselves are rightful

interpreters of what is in the public interest—a putative will of the ‘people’

(Bitonti, 2017; Caramani, 2017), systematically presenting misinformation and

conspiracy theories (Törnberg & Chueri, 2025). They act on their own will

and invite their audience to identify with them (White, 2023). And some people

do. As mentioned by Valcore et al. (2023, p. 251), “deprecation is a

perlocutionary message and permission to hate not because of some

characteristic of the hated other, but for what has presumably been done by the

hated other to the safe, clean, Arcadian, white world the speaker cherishes”.

2.2. Nasty Rhetoric and Emotional Governance

Based on the work of Mouffe (2013), Chang (2019)

and Olson (2020) show that nasty rhetoric is not only about what is conveyed

explicitly by use of language. Political sentiments are often emotional and

affective, determined by viscerally experienced sentiments and a physically

imagined sense of rightness or wrongness. Political persuaders, particularly

populists, use language or images to affect emotions, perceptions of knowledge,

belief, value, and action (Shah, 2024). This aligns with notions of persuasion

that stress pathos as an equally important part of rhetoric as logos and ethos

respectively (Olson, 2020). Populist rhetoric operates in a world where it is

not required for “every statement be logically defensible” (McBath &

Fisher, 1969, p. 17).

Populism is based on emotional appeals to the

‘people’ as the ingroup, anti-elitism, and the exclusion of outgroups who are

routinely blamed and scapegoated for perceived grievances and social ills

(Aalberg & de Vreese, 2016). Emotions are central in nasty rhetoric, thus

in the structural and affective changes that underlie populist mobilisation and

the polarisation of everyday insecurities in general (Kinnvall & Svensson,

2022). Such emotional governance includes techniques of surveillance,

control, and manipulation, i.e. how society governs emotions through cultural

and institutional processes, meaning how it “affords individuals with a sense

of what is regarded as appropriate and inappropriate behavior” (Crawford, 2014,

p. 536). Emotional rhetoric is central in reproduction of structural power and

power relations between ‘us’ and ‘them’ as it pays attention to collective

emotions as patterns of relationships and belonging (Kinnvall & Svensson,

2022), thus central in cultural-institutional as well

as structural policy entrepreneurship aimed at changing other actors’

beliefs and perceptions and enhancing governance influence by altering the

distribution of formal authority (Boasson & Huitema, 2017; von Malmborg,

2024a).

In all, populist politics is very much about

emotional governance through storytelling (Polletta et al., 2011) where the

“core populist narrative about good people reclaiming power from corrupt elites

is rooted in evocative stories drawing on mythical pasts, crisis-driven

presents, and utopian futures” (Taş, 2022, p. 128). Populism is less about

great ideas and more about spinning a good yarn containing heroes, villains and

plotlines promising change (Nordensvärd & Ketola, 2021).

2.3. Democracy Harms of Nasty Rhetoric

The aim of nasty rhetoric is to silence the

outgroup in political discussions (Kalmoe et al., 2018). Hate speech and hate

crime evocate feelings and do emotional harm to outgroup targets (e.g. Lazarus,

1991; Calvert, 1997; Lang et al., 2000; Chang, 2019; Wagner & Morisi, 2019;

Olson, 2020; Hagerlid, 2021; Allwood et al., 2022;

Cowan & Hodge, 2022; Glad et al., 2024). Emotions are important to

behaviour because they are modes of relating to the environment: states of

readiness for engaging or not engaging, fighting or fleeing, in interaction

with that environment (e.g. Frijda, 1986; Frijda &

Mesquita, 1994; Izard, 2010; Keltner et al., 2014). Being emotionally

harmed, victims to hate speech and hate crime are also harmed cognitively,

normatively and behaviourally (e.g. Cassese, 2021; Wahlström et al., 2021;

Abuín-Vences et al., 2023; Renström et al., 2023). As analysed by von Malmborg

(2025b), victims to nasty rhetoric in Swedish climate politics respond

behaviourally in two main ways, mirroring the basic behavioural reactions to

hate, i.e. fleeing or fighting:

Silence and self-censoring: Withdrawing from public debates, ending civil disobedience, changing job, or changing research area.

Resistance and radicalisation: Increased argumentation for climate action, strike-backs with nasty rhetoric, more actions of civil disobedience, or radicalised climate actions such as sabotage and trespass.

Zeitzoff (2023) argues that nasty politics and

nasty rhetoric may have some positive effects to democracy since it provides a

tactic for marginalised groups and politicians to exercise power. However, he

claims that the negative impacts are more detrimental. Without specifying

relations and causalities, he particularly mentions that (p. 53):

it makes people more cynical of democracy and less willing to vote and participate;

politicians in power can use nasty politics as a tool to demonise their political rivals and stay in power, eroding the democracy in the process;

an increase in nasty politics leads good politicians to choose not to run and to retire, and nastier politicians take their place; and

heightened nasty politics precedes actual political violence.

As for nasty politics and rhetoric as a precursor

to political violence, Piazza (2020b), analysing terrorism and hate speech data

for about 150 countries globally for the period 2000–2017, found that hate

speech by political figures boosts domestic terrorism, mediated through

increased political divides caused by hate speech (Klein, 2020). Donald Trump

is a well-known user of nasty rhetoric targeting several groups in society,

promoting hatred and violence (Valcore et al., 2023).

He is not the only world leader accused of publicly denigrating people beyond

politicians based on their racial, ethnic or religious backgrounds, or for

their political opinions (Piazza, 2020b), but he actively incited violent riots

at the storming of Capitolium on 6 January 2021 (Zeitzoff, 2023), and he

violates numerous democratic norms such as legitimacy and accountability in

delivery and content of his speeches (e.g., Jamieson & Taussig, 2017; Ross

& Rivers, 2020).

When politicians view and talk about their

opponents as traitors or illegitimate, they violate a core principle in liberal

and deliberative democracy—pluralism of ideas—leading to political polarisation

(von Malmborg, 2024a). Political hate speech and polarisation breeds general

mistrust in politics (Mutz & Reeves, 2005) and feeds political intolerance,

defined as the support or willingness to denounce basic democratic values and

the equal rights of people belonging to a defined outgroup in a particular society

(Oates et al., 2006).

Focusing on politicians’ use of nasty rhetoric

targeting oppositional politicians, Zeitzoff (2023) and other political

scientists studying nasty rhetoric only analyse effects of nasty rhetoric on

politics and democracy based on harm on politicians as victims and wider

message effects. But nasty rhetoric in climate politics does not only target

oppositional politicians, but also climate scientists, climate journalists,

civil servants, climate justice activists and people in general worried about

climate change for their political opinions and their professional work (von

Malmborg, 2025a).

Going beyond nasty rhetoric between politicians,

research on hate speech and hate crime targeting journalists and scientists

indicate that nasty rhetoric restricts the flow of information, which may

invoke knowledge resistance (Strömbäck et al., 2022). This poses grave

challenges for the functioning of liberal and deliberative democracies, e.g.

(i) free formation of opinion, (ii) public deliberation, (iii) citizens ability

to evaluate public policy, hold politicians accountable and make informed votes

(Tenove, 2020; Wikforss, 2021; Pawelec, 2022), (iv) undermining democratic

processes by corrupting political discussions (Gutmann & Thompson, 1996;

Dahl, 1998), and (v) undermining the legitimacy of the democratic system as

such (Lago & Coma, 2017; Pawelec, 2022). In all, political hate speech

breeds general mistrust in politics (Mutz & Reeves, 2005) and feeds

political intolerance, defined as the support or willingness to denounce basic

democratic values and the equal rights of people belonging to a defined outgroup

in a particular society (Oates et al., 2006). This is considered one of the

most problematic phenomena in democratic societies as it paves the way for

democratic breakdown (Levitsky & Ziblatt, 2018).

Democracy scholars highlight the need for strong

civil society organizations and civic education as an important effort to

defend liberal democracy against ongoing autocratisation (Lührmann, 2021;

Mudde, 2021; Silander, 2024; V-Dem Institute, 2024). As reported by von

Malmborg (2024a), the Swedish government has taken measures to reduce financial

support to civic education and civil society organizations, in parallel to the

attacks on climate justice activists. Thus, reduction of the civic space may

also be a key harm of nasty rhetoric on democracy.

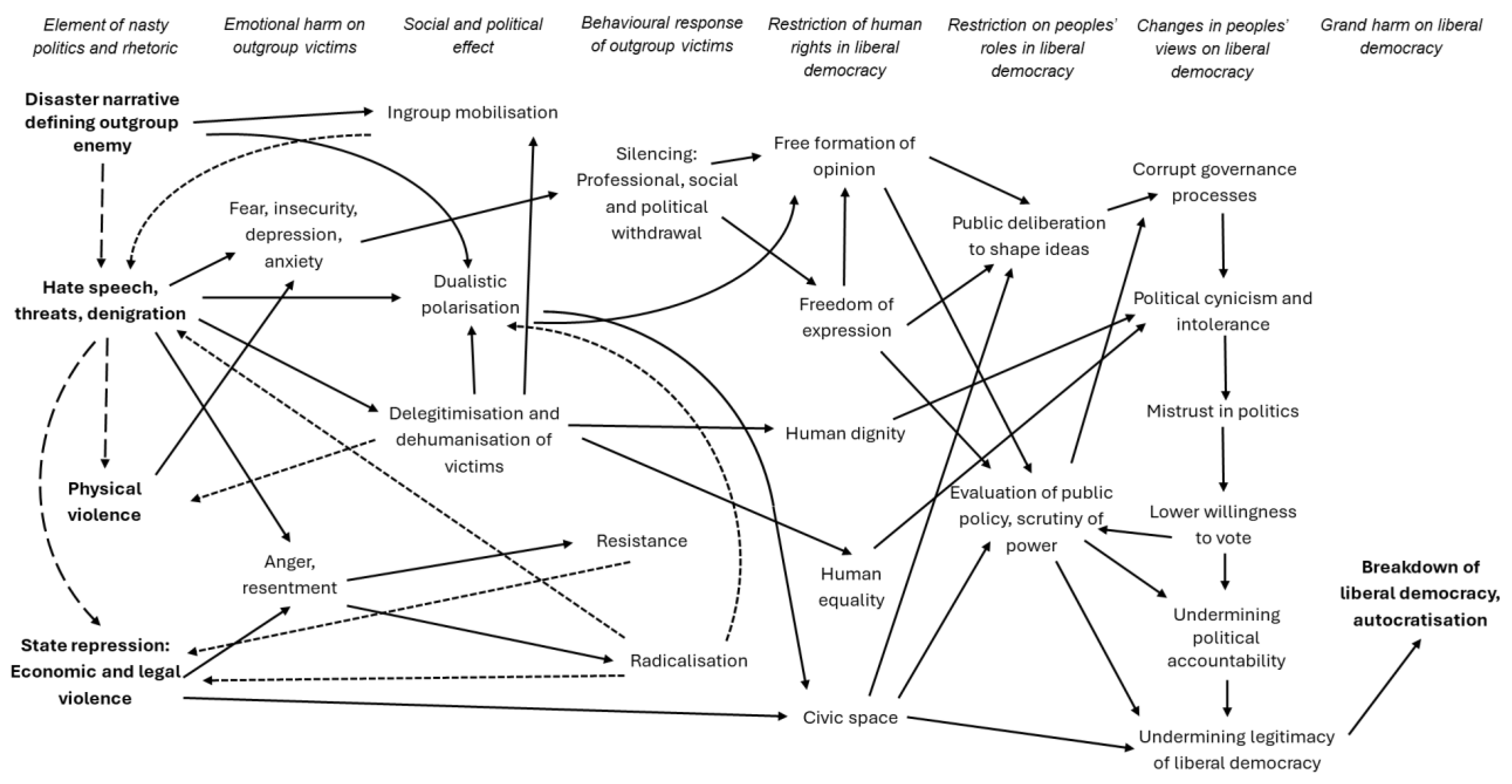

In all, drawing on the literature on behavioural

and democratic harms of nasty rhetoric and more generally hate speech and hate

crime, targeting oppositional politicians as well as other kinds of outgroups

victims, a framework with typologies for analysing democracy harms of nasty

rhetoric is developed (

Table 2), which is

used in this study.

4. The Case of Nasty Rhetoric in Swedish Climate Politics

4.1. A Far-Right Populist Takeover

Sweden has been considered a bastion of strong liberal democracy since the end of World War II, able to develop and maintain a green and equitable welfare state (Boese et al., 2022; Silander, 2024). However, the 2022 elections to the Swedish parliament (Riksdag) marks a shift. Then, far-right nativist populist SD won 20.5 % of the votes and 73 out of 349 seats, becoming the second largest party in the Riksdag after the Social Democrats (S). This progress made SD gain formal powers in the Riksdag, holding the chairs in the committees of justice, labour market, foreign affairs and industry, and having direct influence over the government in most policy areas.

Bargaining on who was to form a government for the 2022–2026 term resulted in the Tidö Agreement (Tidö parties, 2022) between SD and a liberal-conservative troika of M, the Christian Democrats (KD) and the Liberals (L). SD supports the Tidö government, under the condition that SD takes part in decisions in six policy areas to undergo a rapid paradigm shift: climate and energy, criminality, economic growth and household economy, education, migration and integration, and public health, of which criminality, migration and climate change are deemed the most important (Rothstein, 2023). SD holds no seats in the cabinet but has political staff in the PM’s Office within the Government Offices of Sweden. In that sense, SD holds tangible powers but is not accountable for the government’s decisions. In all, the Tidö quartet holds majority with 176 of 349 seats in the Riksdag, while the opposition, consisting of S, MP, C and V, holds 173 seats.

When formed in 1988, SD was extremist and violent, rooted in neo-fascism, but with the election of current party leader Jimmie Åkesson in 2005, SD tried to distance itself from its neo-fascist past and show a more respectable façade to gain legitimacy (Rydgren & van der Meiden, 2016; Widfeldt, 2023). Compared to other far-right movements in Sweden, SD’s ideology is

culture-oriented rather than race-oriented or identity-oriented, focusing on beliefs, values and behaviours that are consider to be Swedish.

4 Based on the works of British nationalist political philosopher Roger Scruton (2004), SD acts to counter

oikophobia, i.e. the contempt for one’s own culture, one’s history and one’s country. To SD, oikophobia characterizes postmodern Western society, where the only thing that is valued is the foreign. Countering oikophobia needs a culture war, in which religion has moved from the periphery to the centre of SD’s populist nativist ideology, where the Church of Sweden’s Protestantism is at the centre of what SD considers Swedish (Poletti Lundström, 2022).

Religion is recurrently one of the adjacent concepts that temporarily stabilises the core of Swedish far-right nativist populism:

people and

territory.

In this culture war, SD combines populism, anti-pluralism and authoritarianism with nativism—the longing for a homogenous nation state—and propose, based on populist storytelling, illiberal policies in many areas, primarily migration but also culture, media, social, justice and environmental policy (Hellström, 2023). SD hails Victor Orbán’s Hungary, the worst example of autocratisation in the world (Meléndez & Rovira Kaltwasser, 2021; Mudde, 2021; Boese et al., 2022; Silander, 2024; V-Dem Institute, 2024), as a role model of democratic governance. They have also welcomed the recent developments in the US and world politics since the installation of Donald Trump as the 47th President of the US in January 2025. Due to the success of SD, Sweden is currently one of the strongholds of far-right populists in the EU (Widfeldt, 2023). To understand SD political agency, they “sacralize their core ideas and predominantly employ virtue ethical justification strategies, positioning themselves as morally superior to other parties” (Vahter & Jakobson, 2023, p. 1). They assign essentialist value to their key political concepts, a stance that sharply contrasts with the moral composition of the rest of the political spectrum adhering to liberal or deliberative perspectives on democracy.

Accusing Swedish established media of belonging to a “left-liberal conspiracy”, SD and other nationalist right-wing groups built their own ecosystem of digital media news sites, blogs, video channels and anonymous troll accounts in social media, which did not have to relate to the rules of press ethics (Vowles & Hultman, 2021b). Normalising knowledge resistance and using nasty rhetoric were central to their strategy of structural policy entrepreneurship (von Malmborg, 2024a).

Nasty rhetoric is an outspoken tactic of SD to entrench the polarising ‘us’ vs. ‘them’ and the ‘people vs. elite’ narratives. It was recently revealed by Swedish news media that SD’s communications office, inspired by Donald Trump and directed by party leader Åkesson, runs a ‘troll factory’. Using anonymous ‘troll accounts’ in social media, SD has deliberately and systematically spread misinformation and conspiracy theories to shape opinion, manipulate voters and incite outgroups by spreading insults, hate and threats.

5 SD Party leader Åkesson has confirmed that SD, representing the ‘people’, use and will continue to use ‘troll accounts’, particularly on TikTok, to avoid getting public accounts reported and closed due to their frequent use of hate and threats:

To you in the Cry...we are not ashamed. It is not us who have destroyed Sweden... It is you who are to blame for it.

Swedish scholars of democracy (Rothstein, 2023; Silander, 2024; V-Dem Institute, 2024; von Malmborg, 2024a) as wll as Civil Rights Defenders (CRD, 2023), United Nations Association of Sweden (2023) and Gustavsson (2024) have identified several signs of autocratisation in Sweden since the 2022 elections. Nasty rhetoric is one important sign. They argue that the current developments in Swedish politics and society risk weakening Sweden’s liberal democracy and may be another step in the process of gradual autocratisation overseen by democratically elected but antidemocratic leaders. Tidö parties use democratic institutions to erode democratic functions, e.g. censoring media, imposing restrictions on civil society, harassing activists, protesting, and promoting polarisation through disrespect of counterarguments and pluralism (Silander, 2024; V-Dem Institute, 2024; von Malmborg, 2024a). Even the editorial offices of Sweden’s largest newspapers, independent liberal Dagens Nyheter, and Sweden’s largest tabloid, independent social democrat Aftonbladet, are worried of the development, arguing that “Sweden is now taking step after step towards less and less freedom”.

4.2. From Climate Policy Role Model to International Scapegoat

Sweden used to be considered an international role model in climate policy (Matti et al., 2021), advocating high ambitions in global and EU climate governance as well as nationally. In 2017, the Swedish Riksdag adopted with support of all parties but SD a new climate policy framework, including:

A target that Sweden should have net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) by 2045;

A Climate Act, stating among other things that the government shall present to the Riksdag a Climate Action Plan (CAP) with policies and measures to reach the targets, at the latest the calendar year after national elections; and

Establishment of the Swedish Climate Policy Council (SCPC), an independent and interdisciplinary body of climate scientists, to evaluate the alignment of the government’s policies with the 2045 climate target.

Sweden’s GHG emissions in total decreased by approximately 37% from 1990 to 2022 and a decoupling of emissions and economic growth began in 1992, when Sweden introduced carbon dioxide taxation. This long-term trend of emissions reductions made a U-turn when the Tidö government supported by SD entered office. They advocated a radical change of Swedish climate policy and governance. SD has long since been vocal as a climate change denier (Jylhä et al., 2020; Vihma et al., 2021), wanting to abort national climate targets and climate policies. SD is culturally and cognitively motivated by conflicting ‘evil’ beliefs of previous governments for decades, both S-led and M-led. Like other European far-right populist parties,

6 SD is mobilising a

culture war on climate change, making climate policy less ambitious (Buzogány & Mohamad-Klotzbach, 2022; Marquardt et al., 2022; Cunningham et al., 2024). Climate policy was purposefully included in the Tidö Agreement by SD, opening a window of opportunity for SD to dictate and veto the government’s climate policy. Bargaining on finalising the Tidö CAP in 2023, SD now accepts the 2045 target but managed to reduce overall climate policy ambitions by deleting short- and medium-term targets and actions important for reaching long-term targets. The Tidö quartet focuses entirely on emission reductions by 2045, ignoring climate science saying that reducing every ton of GHG emitted from now to 2045 is what counts (Lahn, 2021).

Tidö climate policy can be characterised as anti-climate action with increased GHG emissions. The CAP was welcomed by the

Confederation of Swedish Enterprise (CSE) and its libertarian thinktank

Timbro, but heavily criticised domestically by the political opposition, climate scientists, economists, government authorities, the environmental and social justice movement, business associations other than CSE, citizens and editorial writers in leading national newspapers, for its lack of short- and medium-term domestic action, manipulation of information, and a large focus on new nuclear power and climate compensation in other countries.

7 SCPC (2024) and Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (SWEPA, 2024) claimed that Tidö policies lead to increases of annual GHG emissions, corresponding to more than 10 % of Sweden’s total annual emissions, and that the CAP will not suffice for Sweden to reach the target on climate neutrality by 2045, nor Sweden’s responsibilities in relation to EU’s 2030 climate target.

In critique of Tidö climate policy, three out of four parties in the Riksdag opposition (C, MP and V) tabled a motion of non-confidence, calling for the setting aside of climate minister Romina Pourmokhtari (L) for failing to deliver policies that reduce GHG emissions. The critique towards Pourmokhtari also refers to the fact that she herself promised to resign if Sweden does not meet Swedish and EU climate targets—which it will not. In addition, more than 1 350 critical L-politicians from local and regional levels demanded the resignation of Pourmokhtari because she and L gave way to SD’s influence over the CAP, implying crossing several red lines of L’s party program and ideology. However, when the Riksdag voted, the critics did not gather enough support to set Pourmokhtari aside.

Besides domestic criticism, Tidö climate policies were criticised also internationally, claiming that Sweden is losing its role as climate policy frontrunner and risk dragging the EU down with it.

8 Due to the Tidö climate policies, Sweden dropped from number one to number eleven between 2021 and 2024 in the Climate Change Performance Index (Burck et al., 2024). The European Commission has rejected Sweden’s application for SEK 40 billion funding from the EU Recovery Fund since Sweden will meet neither national nor EU climate targets for 2030.

9 In March 2025, the international Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) mentioned in its review of Sweden’s environmental policies that “recent policy shifts, particularly in the transport sector, have put into question Sweden’s ability to meet EU and domestic climate targets, with emissions projected to increase” (OECD, 2025).

4.3. Use of Nasty Rhetoric in Swedish Climate Politics

In a related study, von Malmborg (2025a) found that nasty rhetoric is widely used by party leaders and cabinet ministers, including the PM to target oppositional politicians, climate scientists, climate activists and climate journalists. It is also used by neoliberal, libertarian and far-right influencers and climate sceptics, applauding the weakening of Swedish climate policy.

That high-level politicians in the government and the Riksdag utter insults, accusations and intimidations towards climate scientists, journalists and particularly activists can be considered an important reason for the increase in online hate and threats (von Malmborg, 2025a). Nasty rhetoric has become normalised and collectivised (cf. Peters, 2022) when the PM and other cabinet ministers and people with leading positions in the Riksdag use it, calling the climate justice movement “totalitarian”, “security threats”, “terrorists”, “saboteurs” and “a threat to Swedish climate governance and Swedish democracy” that should be “sent to prison” and “executed”. In addition, they accuse climate science of being “just an opinion”. Green politicians are “strawmen” that should be “killed”, and female climate journalists are a “left pack” and “moron hags” that “will be raped”. Insults, accusations, intimidations and incitements are made openly, mainly in social media from official accounts of ministers and other politicians. Intimidations and incitement targeting climate activists are also made in national radio, on the streets, and in political debates in the Riksdag.

Hate speech is also conveyed anonymously. Accusing Swedish established media of being “climate alarmist propaganda centres” belonging to a “left-liberal conspiracy”, SD and other nationalist right-wing groups built their own ecosystem of digital media news sites, blogs, video channels and anonymous troll accounts in social media, which did not have to relate to the rules of press ethics (Vowles & Hultman, 2021b). Normalising knowledge resistance and using nasty rhetoric were central to their strategy of structural policy entrepreneurship (von Malmborg, 2024a, 2025a).

Swedish politicians rarely humiliate or denigrate other politicians in person, but other political parties. Swedish politics is not as person fixated as, for example, American politics. It is rather far-right extremist persons that target politicians in person. Except for the hate on Greta Thunberg, the same holds true for nasty rhetoric of politicians targeting climate activists or scientists. It is primarily the organizations, not the persons, who are targeted (von Malmborg, 2025b). In contrast, hate and threats sent by anonymous offenders online are often targeting individual climate activists, scientists, journalists and other outgroups, orchestrated by SD and far-right extremist Alternative for Sweden (AfS),

10 who display names, photos, addresses and phone numbers of the ‘enemies’ in far-right extremist web forums, i.e. doxxing

11.

Hate speech in Swedish climate politics has resulted in hate crime in terms of physical violence, but also to increased legal and economic repression of climate activists. In spring 2022, XR reported that five masked people attacked a climate action, and that one activist had been assaulted, following infiltration and doxxing organized by AfS.

12

Since 2020, 310 climate activists have been prosecuted in Swedish district courts for different crimes related to civil disobedience, some of them several times. Of these, 200 persons were convicted, mainly to fines or suspended sentence. In 2022, leading SD politician now chair of the industry committee in the Riksdag, and the former M spokesperson on legal policy issues, now minister of migration, accused climate activists performing traffic blockades at demonstrations of being “saboteurs”, and that they should be charged for “sabotage” instead of “disobedience to law enforcement”.

13 This change was later supported by the current minister of justice, saying that the actions of climate activists must be seen as sabotage so that they can be “sentenced to prison”.

14 In 2022, without change of legislation, prosecutors around Sweden suddenly began to charge climate activists performing roadblocks at demonstrations for sabotage. Between summers 2022 and 2023, 25 persons were convicted for sabotage, some of which were sentenced to prison, but most were later acquitted in the Court of Appeal.

15

In 2024, a person engaged in

MR, a subgroup of

XR that not engage in civil disobedience but only friendly actions such as singing,

16 was fired from her job at the Swedish Energy Agency due to accusations and intimidations of her predecessor, right-wing and far-right media and minister for civil defence that she was a threat to Swedish national security. In 2023, a scientist engaged in

SR was arrested for alleged sabotage of an airport. The action took place outside the airport and the scientist activist held a banner. The court case, which includes several lies from the airport manager, is still ongoing, but the activist recently got her application for Swedish citizenship rejected with the motivation that “[s]ince you are suspected of a crime, you have not shown that you meet the requirement of an honest way of life”.

17

4.4. Emotional and Behavioural Harm on Victims to Nasty Rhetoric

Nasty rhetoric is not empty words, it is emotional. Political sentiments in nasty rhetoric stress the evocation of feeling, aiming at persuading ingroup people to join the weird kind of sport of hating and threatening ‘enemies of the nation’, and at dehumanising and hurting outgroup people emotionally and eventually physically, economically or legally. Being hit, nasty rhetoric does something to people. Results of this qualitative study identify some similarities but also differences in emotional and behavioural effects on the different groups of victims. In common, nasty rhetoric violates the victims’ fundamental right to dignity and equality. Like other forms of hate speech and hate crime, nasty rhetoric targeting climate scientists, climate journalists and climate activists also has message effects (cf. Ilse & Hagerlid, 2025). The motive behind the act is aimed at more than just the victim. Hate and threats are directed against people or groups of people to prevent them from participating in the public and democratic discourse. They should refrain from expressing opinions that do not agree with those of the perpetrator or perpetrators.

Climate journalists and non-activist climate scientists, targeted as individuals for what they do professionally, report threats of being fired, physical violence and death threats, beyond insults and accusations. They react with fear of crime and being followed or chased, insecurity, anxiety and exhaustion, but also anger. To cope with mental stress, many of them withdraw from the public debate or change research area or job. They self-censor. But some get angry, bite the bullet and try to win the battle. They hit back with insults and accusations, showing with the eye of a child and based on science that the offenders are wicked and naked like the emperor. Scientists’ and journalists’ reactions with fear and insecurity are in line with research on Swedish hate crime based on other motives, e.g. anti-feminism, sexual identity and ethnicty (Hagerlid, 2021; Atak, 2022; Ilse & Hagerlid, 2025).

In comparison, climate activists are targeted for their political opinions and actions in leisure time, outside their professional occupations. They are targeted with insults, accusations, intimidations and incitement, mainly as a group, less so as individuals. The same holds true for science activists, where the activism is performed in their leisure time, not at work. When targeted as individuals, it is through secondary victimisation from legal and economic repression—a late stage of nasty rhetoric—more seldom incitement about physical violence or death threats. One exception is Greta Thunberg, who has experienced plenty of hate and threats based on climate scepticism and misogyny. Some activists react with fear and choose to revert to more friendly actions, while others, particularly the core group activists react with anger and plan new actions over and over again, while eventually getting physically exhausted. Their fear and anxiety are related to the climate emergency, which made them climate activists. They react with anger since their perpetrators continue to deny the climate emergency, despite their actions. They also react with physical exhaustion since they find it difficult to combine job, family, court trials and climate actions while the Earth is burning and flooding at the same time. An uncertainty factor for climate activists changing behaviour is that politicians and other haters do not see any difference between the very heterogeneous group of climate justice organizations. All are lumped together. Backing down from civil disobedience to peaceful actions makes no difference to the perpetrators, and there is a risk that you will continue to be exposed to hatred and threats. But as mentioned, hate and threats are primarily aimed at the organizations, not individual persons.

Targeted as a group, climate activists seem to spur each other to learn individually and collectively to ignore insults, accusations, intimidations and incitements. They undergo a process of desensitisation (cf. Soral et al., 2018). They are less sensitive to hate speech and more prejudiced toward hate speech perpetrators, finding nasty rhetoric to be part of a larger strategy orchestrated by (far) right-wing politicians to polarise and break down society and democracy. They are strengthened in their conviction that they are right, and the perpetrators are wrong. They are more afraid and anxious about the climate emergency and get angry because they think that politicians and business leaders are not acting appropriately fast and ambitious given the severe situation. Fear, angst and anger about social, economic and political inaction to curb climate change made them climate activists. Instead of being silenced by nasty rhetoric, they are radicalised and do more actions.

Compared to climate scientists and journalists, climate activists and scientist activists are victimised twice. First by hate speech, second by the state repression through economic and legal violence being fired and prosecuted and sometimes sentenced for criminal acts. Climate activists testify about hateful and threatening behaviour of individual police officers. This resembles experiences of legal estrangement among racist hate crime victims in Sweden (Atak, 2022).

4.5. A Message Effect

Emotional governance with nasty rhetoric does not only target individuals in the outgroup. It includes techniques of surveillance, control, and manipulation to govern emotions in society, providing individuals with a sense of what is regarded as appropriate and inappropriate behaviour (Crawford, 2014). Nasty rhetoric has a message effect that target people and society in general. Nasty rhetoric is central in reproduction of structural power and power relations between ‘us’ and ‘them’ as it pays attention to collective emotions as patterns of relationships and belonging (Kinnvall & Svensson, 2022).

The climate activist who got fired from the Swedish Energy Agency initially thought that her case would make people more afraid to get involved in climate activism. But the aftermath of her case made her change opinion:

18

Now I don’t think so anymore. I think I’m a winner somewhere. It’s sick that this could have happened. But if it can lead to people becoming less afraid, if it becomes more difficult to subject people who engage in activism to repression, then this has contributed to something good. We have shown that if you fire people who are committed to the climate issue without reason, then you will be in the newspaper. Even the UN steps in and writes the world’s finest documents. Such strong words! The UN’s letter was to all of us. Not just for me. I’ve come out of this stronger. And now I feel that there has been a point to everything. We have managed to turn a drive into something positive.

What made her change her mind was that the Green Party and the Left Party reported the minister of civil defence for ministerial rule. A trade union for state employees, ST, took the case to the Chancellor of Justice, and later to the district court. And the UN rapporteur on rights of environmental organisations wrote a letter to the Swedish Government, stating that he was deeply concerned with the actions of the minister of civil defence. The trade union’s formulations are crystal clear:

You cannot hide behind the Security Protection Act in order to restrict a constitutional right, such as freedom of speech. The Civil Defence Minister’s actions can easily be interpreted as a desire to restrict the freedom of expression of government employees.

But this turned out to be wrong. It has been the other way around. Due to the message effect of nasty rhetoric, more state employees feel anxious about getting involved in the climate debate, of saying what they think. A culture of silence has spread. The fact is that many state employees testify about widespread fear and a culture of silence, and that the climate issue is polarised and difficult to discuss.

19 A civil servant in a municipality states:

20

That we feel that we have to hide, because we are fighting for our children and grandchildren to have a planet that can safely be lived on. But that’s the general mood right now.

The hunt for climate activist employees in state agencies has not only been limited to the energy agency. According to the World Health Organization (2021), climate change is the biggest threat to human health. When officials at the Public Health Agency of Sweden (PHAS) appealed to raise the issue, they were called activists by their superiors, who also told that they had behaved inappropriately and violated the state’s values—the rules that government officials must follow. “We were being silenced”, says one employee.

21 Officials of PHAS raised the issue after an action by

Scientist Rebellion at the entrance of PHAS, arguing for the agency to address climate change as a public health issue. The fear of some kind of repression from the employers have made more than 60 civil servants in 18 state agencies, regions and municipalities, many of which have key roles in climate policy, to form a secret climate network.

22

The hate and threats targeting the climate activist that got fired from the energy agency and the silencing of employees at PHAS were preceded by leading Tidö members of the Riksdag claiming that non-political staff in the Government Offices and national agencies are activists, taking employment to drive their private agenda.

23 It has later been found that leaders in SD have an exclusion list of people they want to fire from the Government Offices for having wrong opinions.

24 This is similar to, but far behind the Trump administration’s Project 2025 to reshape the federal government of the United States and consolidate executive power in favour of far-right extremist policies.

25

Policy officers, managers and director generals in state agencies are reacting emotionally. People sit crosswise and slow down the clean energy transition because they become suspicious and afraid of doing wrong. An employee of a state agency working with climate policy and member of the secret network testifies:

26

I work at a government agency that really works with environmental and climate issues. Every employee and manager know how bad the situation is with climate change. Still, we downplay the external information about how serious it is. There is an anxiety about the political situation—we are giving in before anyone has even demanded it.

A recent study from a Swedish labour union reports that civil servants in state agencies have become more silent (TCO, 2025). They are afraid of telling their opinion openly, and if they do or if they act as whistle-blowers, they are afraid of the consequences.

27

After the civil defence minister’s outburst and demand that ‘this should not happen again’, the Swedish Energy Agency has rearranged its recruitment routines with additional question batteries. They react by tightening the seat belt for other climate engaged people and people sympathetic with civil disobedience who seek security-classified positions. If you show climate commitment, there will be tougher tests and controls, which does not make it easier for the agency to find qualified aspirants. And, if you show an understanding that people are protesting something through peaceful civil disobedience, you will not pass a security clearance. In other agencies, staff perceived as activistic have been replaced in their job.

5. Nasty Rhetoric as a Threat to Democracy

Noting “a disturbing groundswell of xenophobia, racism and intolerance”, where “social media and other forms of communication are being exploited as platforms for bigotry, and that neo-Nazi and white supremacy movements are on the march”, the United Nations has launched a

Strategy and plan of action on hate speech.

28 In the foreword, UNSG António Guterres mentions that:

This is not an isolated phenomenon or the loud voices of a few people on the fringe of society. Hate is moving into the mainstream—in liberal democracies and authoritarian systems alike. And with each broken norm, the pillars of our common humanity are weakened. Hate speech is a menace to democratic values, social stability and peace. /…/ Silence can signal indifference to bigotry and intolerance, even as a situation escalates and the vulnerable become victims.

As noted by the UNSG, and analysed by political scientists and sociologists, nasty rhetoric is divisive and contentious and includes insults and threats with elements of hatred and aggression that entrenches ‘us vs. them’ polarisation, designed to denigrate, deprecate, hurt, dehumanise and delegitimise their target(s) (see e.g. Moffitt & Tormey, 2013; Aalberg & de Vreese, 2016; Moffitt, 2016; Kalmoe et al., 2018; Lührmann et al., 2020; Mudde, 2021; Kinnvall & Svensson, 2022; Zeitzoff, 2023). As for Swedish climate politics, nasty rhetoric is used by climate sceptic right-wing and far-right politicians and their anonymous followers to emotionally hurt their outgroups enemies, threatening climate activists, climate scientists and climate journalists to silence (von Malmborg, 2025a, 2025b). Some may do it to get attention, to fit in, or just for fun.

Previous research on nasty rhetoric primarily focuses on nasty rhetoric between politicians and the silencing of politicians, having been exposed for many years by oppositional politicians and online warriors who hide behind their computer screens shouting “traitor”, “assassinate”, “kill” (cf. Zeitzoff, 2023). But these scholars do not analyse and problematise nasty rhetoric targeting scientists, activists and journalists. As discussed below, these groups have important roles in liberal democracies, and the nasty rhetoric attacks on these groups are also harming democracy. This study has identified a multitude of negative impacts of nasty rhetoric on liberal democracy, taking place in different stages where one leads to other, also with feedback loops that strengthens the effects or invoke new kinds of nasty rhetoric (

Figure 1). These effects are discussed in the remainder of this section.

Before analysing how nasty rhetoric targeting climate scientists, activists and journalists affect liberal democracy based on the silencing or radicalisation of victims, the more general effect of populist nasty rhetoric in terms of anti-pluralist, dualistic polarisation is analysed.

5.1. Polarisation of Society and Politics

5.1.1. Theological Dualism and Magick

According to Zeitzoff (2023) and other scholars of nasty rhetoric, hate speech and hate crime, and as described in section 4, nasty rhetoric entrenches a division of society and politics into an antagonistic dualistic state. Political science literature often refers to Manichaeism or Manichean to figuratively describe the existence of dualism (e.g. Klein, 2020; Zulianello & Ceccobelli, 2020; Somer et al., 2021), but it seldom relates to the actual meaning of Manichean dualism. Developing a more elaborated understanding of dualism in far-right populist politics, I refer explicitly to Gnostic and proto-orthodox

29 theological dualism of Good–Evil and God–World and an Aristotelean dualism of intellect–body. References to theological dualism and theories of mind are made since they define different kinds of dualism that can help us understand the sort of dualistic divide entrenched by far-right populists, which are largely embedded in different sorts of Christianity, e.g. Protestantism in Sweden and Evangelic Christianity in the US.

Analysing the understanding of religion in the landscape of Swedish radical nativism between 1988 and 2020, Poletti Lundström (2022) found that the concept of religion has moved from the periphery to the centre of SD’s populist nativist ideology, where the Church of Sweden’s Protestantism is at the centre of what SD considers as Swedish. In SD’s universe of ideas, what are termed religious and political views are interwoven with each other—there is no sharp boundary between religion and politics. Religion, more specifically Protestantism, is used by SD to shape ideologies in a discursive struggle to define the language of politics and public policy. Poletti Lundström (2022) concludes that religion is recurrently one of the adjacent concepts that temporarily stabilises the core of Swedish far-right nativist populism: people and territory.

To Gnostics as well as proto-orthodox Christians the world had become dreadfully corrupt since its creation and that people need to be saved from it. This dualism of God and the World, the Good and the Evil, originated in the writings of John and Paul, which were held as sacred scripture by both the Gnostics and the proto-orthodox. 1 John 5:19 declares, “We know that we are God’s children, and that the whole world lies under the power of the evil one”.

30 Paul repeatedly uses the term ‘archon’ to refer to sinister beings who govern the world from the part of the sky below the highest heaven (Pétrement, 1990). For the proto-orthodox Christians, as well as for evangelical Christians like the US Christian right, salvation would occur via bodily resurrection rather than spiritual enlightenment. The material world may have been corrupt, but it was created to be perfect and therefore contained within itself the capacity for perfection, which would be realised again when Jesus returned to earth a second time on the eschatological Judgement Day ensuing separation of the righteous from the wicked, i.e. the good from the evil (Ehrman, 2003).

Professor of climate justice Naomi Klein claims that what we are now witnessing in the US is that “the most powerful people in the world are preparing for the end of the world, an end they themselves are frenetically accelerating”, partly by denying the need for climate action (Klein & Taylor, 2025). She argues that is not so far away from the more mass-market vision of fortressed nations that has gripped the far-right globally, including Australia, Italy, Isreal and Sweden:

In a time of ceaseless peril, openly supremacist movements in these countries are positioning their relatively wealthy states as armed bunkers. These bunkers are brutal in their determination to expel and imprison unwanted humans (even if that requires indefinite confinement in extra-national penal colonies).

In Sweden, the Tidö parties proposed in 2023 that Sweden shall rent prisons in other countries to house people that have committed crime and been sentenced to prison in Sweden.

31 To Klein and Taylor (2025), both the priority-pass corporate state in the US and the mass-market bunker nation in Sweden share a great deal in common with the Christian fundamentalist interpretation of the biblical Rapture, when the faithful will supposedly be lifted up to a golden city in heaven, while the damned are left to endure an apocalyptic final battle down here on earth. The far-right’s fascination for the Judgement Day, the Rapture, has been described also by Italian philosopher and novelist Umberto Eco (1995), reflecting upon his childhood under Mussolini. He states that fascism typically has an “Armageddon complex”—a fixation on vanquishing enemies in a grand final battle. Weintrobe (2021, p. 251) depicts a fascination of libertarians and neoliberal economists for what she calls a “Noah’s Arkism twenty-first-century style”.

Following the Gnostic and proto-orthodox dualism, the concept of religion provides SD with a demarcation between ‘us’ and ‘them’—between a homogenic people and external enemies as well as internal traitors (Poletti Lundström, 2022). Swedish Protestantism, which is however not fundamentalistic, provides an essential exclusionary mechanism aimed at imagined outgroups who are assumed to, in varying degrees, be superstitious, conspiratorial, fanatical, or divisive. Swedish Protestantism also provides a mechanism for construing an imagined ingroup through ideas of a Volksgeist that via Christianity travels from a distant, and often forgotten, mythological past (Poletti Lundström, 2022).

Far-right populist politics is very much about polarising storytelling (Polletta et al., 2011 Taş, 2022) with conspiracy theories and nasty rhetoric to spin a good yarn containing heroes, villains and plotlines promising change (Nordensvärd & Ketola, 2021). They act on their own will and invite their audience to identify with them (White, 2023). In this sense, nasty rhetoric can be seen as a sort of ceremonial magic—Magick—the science and art of causing change to occur in conformity with will (Crowley, 1912/1988; Bogdan & Starr, 2012; Asprem, 2013).

5.1.2. A Response to Post-Politics

In the case of climate politics, the dualistic polarisation comes after years of global depoliticisation or ‘post-politicisation’ of climate politics (Swyngedouw, 2011). For decades, there had been a consensus that something must be done to mitigate climate change. What should be done was mainly turned into a technocratic practice through consensus building on techno-economic solutions among national authorities and businesses, suppressing the articulation of social conflict and justice (Thörn & Svenberg, 2016). Being part of the hegemonic ecological modernisation discourse of liberal environmental democracy, climate post-politics conflicts with the deliberative ecological democracy worldview of the climate justice movement and many green and left parties, stressing the existence of and need to address social conflicts related to equity and justice in climate politics (von Malmborg, 2024a).

The current cycle of climate activism is very much a response to this climate post-politics (Schlosberg, 1999; Cassegård & Thörn, 2017; Berglund & Schmidt, 2020; de Moor et al., 2020). Until climate politics is re-politicised, focusing on the urgency of the zero-carbon transition including focus on equity and climate justice, the climate justice movement will continue to view the movement as challenging the prevailing social-political paradigm through confrontation such as iconoclastic attacks on airports, buildings, painted art or art performances, civil disobedience such as road blocks, or peaceful activism such as flash mobs, sit-ins or singing, targeting politicians and companies portrayed as ‘enemies’ but also aimed at raising awareness of the public (von Malmborg, 2025b). The climate justice movement is clearly antagonistic and dualistic. Some argue that the movement and Greta Thunberg are even populists, since they use a story with a clear plotline containing emotions, agency, antagonism, heroes and enemies (Nordensvärd & Ketola, 2021). I tend to disagree, since they have clear ecocentric and deliberative ideology, they do not claim to represent the people, and their stories and narratives are based on science, not fiction (cf. Zuliyanello & Ceccobelli, 2020).

5.1.3. Liberal Environmental Democracy Under Attack

Beyond referring to a climate emergency, climate justice activists formulate system criticism based on climate science calling for a just transition (Evans & Phelan, 2016; Wang & Lo, 2021; Fischer et al., 2024). It is about the realisation that the whole economic system of today is wrongly inverted (Bailey et al., 2011; Davidson, 2012). An insight transformed into a critique of the neoliberal economic system and its focus on free markets and economic growth (Euler, 2019; Khmara & Kronenberg, 2020). In addition, a critique of the hegemonic liberal democratic system with its increasing focus on restricted and competitive participation where it pays off to invest large in lobbying, as opposed to a more deliberative and inclusive ecological democracy (Pickering et al., 2020; von Malmborg, 2024a).

But liberal environmental democracy is also criticised from far-right populists. Climate change tends to be discussed as a technical issue, a transnational issue and, as stressed by the climate justice movement, an issue that invites alternative ways of living and post-material values—in essence a wicked problem requiring a pluralism of perspectives to solve. This is the very opposite of a populist policy issue, with simple problem framings and simple solutions. Thus, climate change is perfect for populist negation imaginary (Buzogány & Mohamad-Klotzbach, 2022; Marquardt et al., 2022). White (2023) finds another important explanation for populists negating ambitious climate policy—the discourse of climate emergency—that it is something necessitating an urgent response. Framing climate change as an emergency casts politics about responding to external demands as a politics of necessity rather than politics of choice. The possible options for political agency to choose among are drastically narrowed. As claimed by White (2023, p. 8), “populists are well placed to draw support by defining themselves against the necessity-centred discourses of the national and supranational mainstream”, and present an opposing problem framing and policy option triggered by a value-laden, devil-shift-influenced threat (cf. Caramani, 2017). In addition to this anti-emergency politics, there is also an alter-emergency politics, in which far-right populists argue that authorities are dealing with the wrong emergency, e.g., climate change instead of migration (White, 2023).

Like other right-wing populist parties in Europe, SD is waging a culture war on climate policy (Cunningham et al., 2024) as a response to the politics of emergency advocated by climate scientists, the climate justice movement, and leading politicians in the EU and Sweden (White, 2023). Through its significant voter base, SD has had a great opportunity to influence the Tidö government to adopt the same anti-emergency climate policy. SD deliberately included climate policy in the Tidö agreement that frames which policy areas that should undergo a paradigm shift for SD to support the M–KD–L government, thus giving SD a veto on Swedish climate policy and governance. SD’s top candidate in the 2024 elections to the European Parliament, as well as the SD environment and climate policy spokesperson, want to repeal the EU’s new climate legislation Fit for 55 and the EGD climate strategy.

5.1.4. Polarisation as a Response to Threats to Populist Worldviews

Calls for economic degrowth (Heikkurinen, 2021), with a resulting perceived intrusion upon their worldviews and dominant status in society, is a symbolic threat to right-wing and far-right politicians and other climate sceptics (Vowles & Hultman, 2021a, 2021b). Such threats predicts hatred (Stephan & Stephan, 2017), which in turn predicts aggressive tendencies and hurting behaviour (Martínez et al., 2022b). Based on a combination of anti-establishment rhetoric, knowledge resistance and emotional communication of doubt, industrial/breadwinner masculinities, anti-feminism and nativism (Hultman et al., 2019; Jylhä et al., 2020; Agius et al., 2021; Vihma et al., 2021; Vowles & Hultman, 2021b), SD presented a fictional ‘disaster’ narrative (cf. Kinnvall & Svensson, 2022) to polarise climate politics into a Gnostic and proto-orthodox Christian dualistic worldview of ‘good’ vs. ‘evil’, ‘us’ vs. ‘them’, the ‘people’ vs. the corrupt ‘elite’ (cf. Ketola & Odmalm, 2023; Abraham, 2024), accusing the former red-green government, the EU, climate scientists and climate activists for mismanagement and being a threat to and ‘enemies’ of Sweden and the Swedish. Analysing the psychological roots of the climate crisis, psychoanalyst Sally Weintrobe (2021) argue that wealthy people in wealthy countries are stuck in a state of exceptionalism, i.e. a specific psychological state in late capitalism where people seize to compromise. If reality or conspiratory fiction in any way challenges that perception, it is the threatening challenge that needs to be denied. Therefore, individuals or groups who tell difficult, challenging things—such as climate activist, climate scientist or climate journalists—needs to be ostracized. Or be accused of terrorism.

SD, mainly attracting white older men, look back to a great national past during the oil-fueled record years of the 1950s and 60s when men had lifelong jobs in industry and sole access to society’s positions of power (Vowles & Hultman, 2021a, 2021b). This reference to a mythical past (cf. Taş, 2022) is similar to the narrative of Trump–Vance and the MAGA movement, imposing high trade tariffs on export to the US to protect and stimulate American industrial production to bloom like it did in the late 19th century.

Portraying themselves as the saviour of the nation and the people from the wrong-doings of the corrupt elite, following a Gnostic and proto-orthodox Christian narrative, the Tidö parties referred to popular legitimacy and a skewed interpretation of climate justice to take measures a few months after entering office to reduce costs of fossil fuels for cars and aviation, which they considered be too high and harmful for Swedish households. Despite that costs of public transportation had increased much more than fuel prices, and that three out of four Swedes wanted the government to invest more in public transport, the Tidö parties actively refrained from taking measures to reduce costs for public transport. Critics have claimed that the GHG emissions increased significantly and that cost reductions for fossil fuels do not benefit the groups who are most vulnerable (SCPC, 2024). Thus, climate policies adopted are not responsive to popular will. Popular legitimacy has nothing to do with democratic legitimacy, but is rather another term for populist legitimacy (von Malmborg, 2024c).

Instead of countering the threatening degrowth narrative with good arguments in a public debate, as would be the case in liberal or deliberative democracy, Tidö politicians and their followers responded with nasty rhetoric, painting a threatening picture of climate activists but also climate scientists and climate journalists as enemies to the people that should be punished for their crimes against the homogeneous ‘people’. Climate scientists and climate science are portrayed as “just an emotional opinion” in conflict with the Aristotelean intelligible knowledge of the Tidö parties. Non-violent climate activists are portrayed as “a threat to democracy”, “totalitarian forces” or simply “terrorists” to be “sent to prison” and “executed”. That Greta Thunberg has gone from pet peeve to pariah among Tidö parties, CSE and Timbro and other climate sceptics from 2018 to 2020 is no coincidence (Vowles & Hultman, 2021a).

5.1.5. Dualistic Polarisation to Dismantle Ideational Pluralism