2.2. Production and Processing of Research Samples

The alloy samples were melted in a copper water-cooled crystallizer in an argon arc furnace with a non-expendable tungsten electrode L200DI (Leybold-Heraeus, Hanau, Germany) at an argon pressure of 40×103 Pa. The following were used as charge materials: titanium (Ti-1 grade), zirconium (Zr-1 grade), and niobium (Hb-1 grade). The materials were placed in a copper water-cooled tray of a vacuum electric arc furnace as follows: titanium was placed at the bottom of the crystallizer wells, then zirconium, and niobium on top. The order of arrangement of initial metals corresponded to the melting temperature of each material, and melting was carried out by arc directed from top to bottom. In addition, zirconium was placed in a separate pan to act as a getter. The furnace was vacuumed to a residual pressure of 1.33 Pa and filled with high purity inert argon gas. First, the zirconium getter is melted after induction into the inert gas chamber to remove possible oxygen impurities in the gas. Next, the starting materials are melted until individual ingots are formed. Remelting was carried out 7 times, with the ingots being turned over for better mixing of the raw materials. The specified number of remelting operations helped to achieve uniformity of chemical composition throughout the ingot volume. The duration of each ingot melting was 1-1.5 min. After melting, the ingot had the shape of a "boat" with length ~120 mm, width ~25 mm, height ~12 mm.

The obtained ingots have a dendritic structure. Homogenizing annealing in a vacuum resistance furnace ESKVE-1.7.2.5/21 ShM13 (NITTIN, Moscow, Russia) at 1000 °C for 4 h was used to homogenize the structure and remove stresses. To protect against oxidation, annealing was performed in a vacuum environment at 27×10−4 Pa

Primary deformation of ~18 mm thick castings was carried out by warm rolling at preheating to a temperature of 700 °C on a double-roller mill, DUO-300 (AO Istok ML, Fryazino, Moscow Oblast, Russia), with partial absolute compressions per pass: 1.5 mm down to billet thickness of 4.0 mm (heating every 2 passes, total 10 passes), then 1.0 mm down to billet thickness of 2.0 mm (heating every pass, total 2 passes), and a further 0.5 mm down to final billet thickness—1 mm (heating before the first pass at thickness of 2 mm, total 2 passes). The billets were heated before deformation in a muffle furnace KYLS 20.18.40/10 (Hans Beimler, Leipzig, Germany) to a temperature of 600°C for 20 min before the first rolling and for 5 min during intermediate annealing. The plates were cold-rolled from a thickness of 1.5 mm. The effect of heat treatment on the structure and mechanical properties of Ti-38Zr-11Nb alloys was investigated on samples cut from plates with a final thickness of 1 mm using a DK7745 Electrical discharge machining (Meatec, Moscow, Russia). Prior to this, the plate (length ~640 mm, width ~56 mm, height ~1 mm) was quenched by heating for 5 min at 600°C and cooling in room temperature water. During the rolling and quenching process, a thin oxide layer was formed on the plate surface. This layer was removed by mechanical grinding.

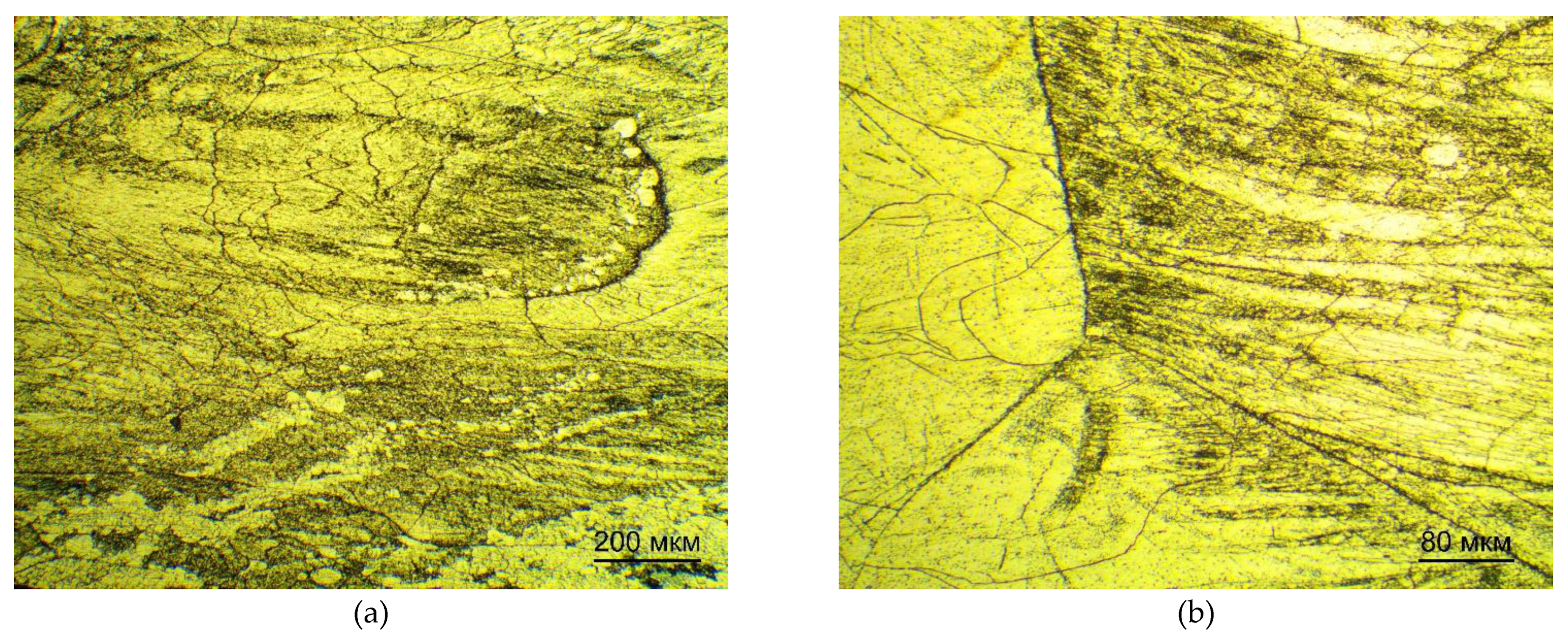

Preparation of samples for metallographic study was carried out by sequential grinding on a Phoenix 4000 machine (Buehler, Lake Bluff, Illinois, USA). The microstructure was revealed and analyzed by etching in a weak solution of hydrofluoric and nitric acids with distilled water in the ratio of 10% HF: 10% HNO3: 80% H2O for 20–30 s. After, the microstructure was rinsed with distilled water, and residual water was removed by air flow.

2.3. Methods of Research

To determine oxygen and nitrogen impurities, we used reducing melting in a graphite crucible in a helium-fueled pulse resistance furnace using the TC-600 analyzer (LECO, 3000 Lakeview Avenue, St.Joseph, MI 49085-2396, USA). Nitrogen was detected by thermal conductivity, and oxygen was detected by the amount of released CO2 using the infrared absorption method.

To determine hydrogen impurities, we used reducing melting in a graphite crucible in an argon-fueled pulse resistance furnace using the RHEN-602 analyzer (LECO, 3000 Lakeview Avenue, St.Joseph, MI 49085-2396, USA). Hydrogen was detected by thermal conductivity.

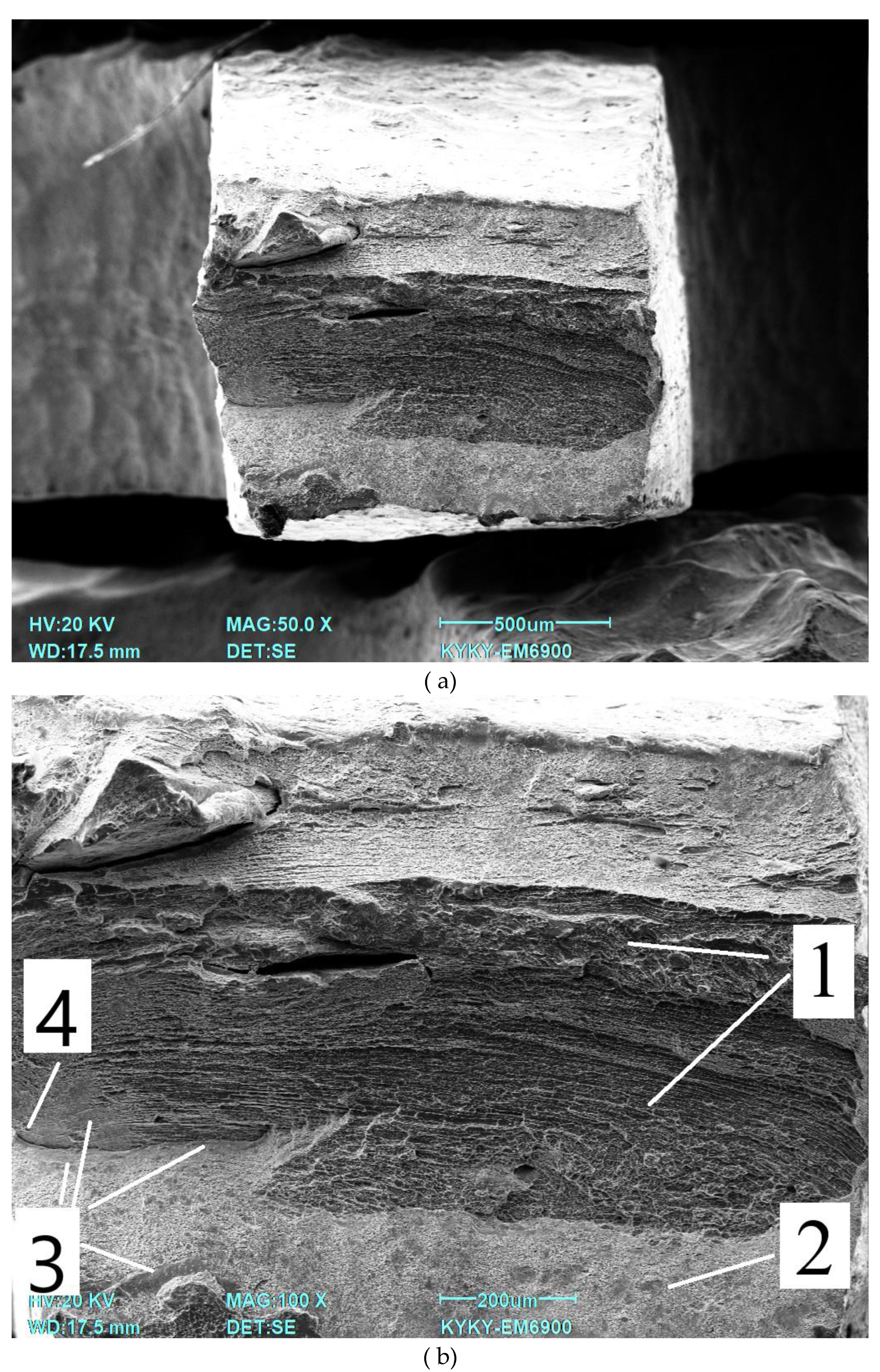

To determine carbon and sulfur impurities, we used oxidizing melting in a ceramic crucible in an induction furnace with the flux using a CS-600 analyzer (LECO, 3000 Lakeview Avenue, St.Joseph, MI 49085-2396, USA). The elements were detected by the amount of released CO2 and SO2 using the infrared absorption method. The distribution of elements was studied using the scanning electron microscope (SEM) EM6900 (KYKY, Beijing, China) with an EDS detector from Oxford Instruments (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom) using Aztec software.

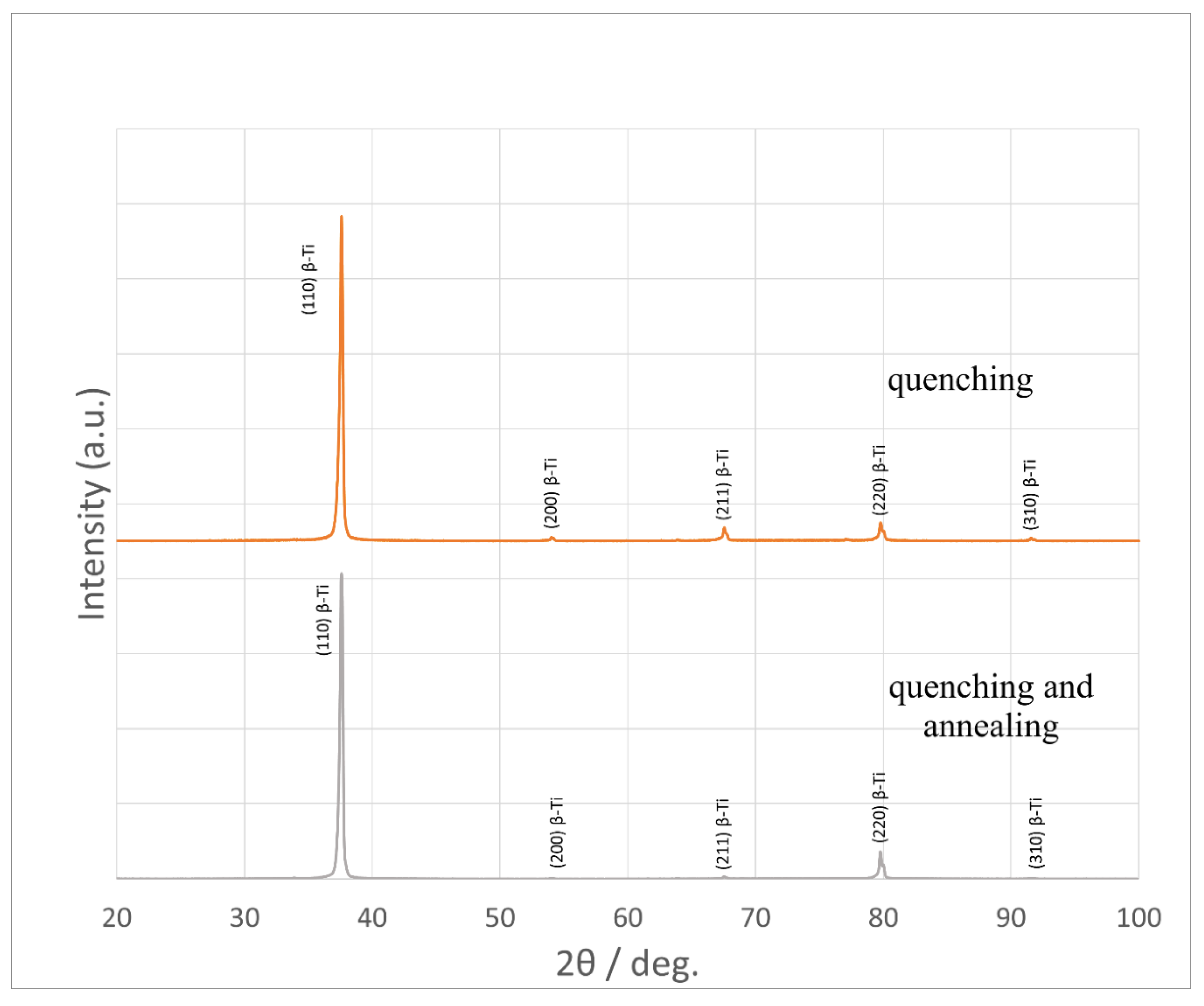

X-ray phase analysis was performed on the DX2700mini diffractometer (Dandong Haoyuan Instrument Co., Dandong City, Liaoning Province, China). The studies were carried out in CuKα = 1.54178 Å radiation, 2θ = 20-100° range, the shooting step was 0.02°/s, the holding time per step was 0.2 s, the voltage on the tube was 40 kV, the current was 13 mA. The analysis of the obtained diffraction patterns was carried out in the Match! 3 program.

For optical examination of the microstructure, the samples were pre-pressed in a rigid mold into cylinders by means of one-sided pressing.

The samples were pressed on an IPA 40 air-hydraulic press (Remet, Bologna, Italy) into Aka-Resin Epoxy resin at temperatures of 160…185°C and a holding time of 20 minutes. The sample was placed in a mold, filled with granulated resin, after which the chamber was closed and the sample was pressed to a pressure of 6 bar. The device then performed a given program, after which the pressed sample was ground and polished. Polishing and grinding of samples for examination on an optical microscope were carried out in the following sequence.

• On a Piatto diamond disc with the following grit:

P220 for 10 min

P600 for 10 min

P1000 for 5 min

P1200 for 5 min

P2500 for 5 min

P4000 for 5 min

• On an Akasel NAPAL velvet polishing wheel with a DiaMaxx Poly diamond suspension with particle sizes of 1 μm and 50 nm for 5 min for each suspension.

A Phoenix 4000 polishing machine(Buehler, Lake Bluff, Illinois, USA) was used for grinding and polishing.

The surface of the samples was etched with a solution of nitric and hydrofluoric acids with distilled water in a ratio of HF: HNO3: 15 H2O by volume. The sections were immersed in the etching solution for 5–30 s, then washed with running water.

Light microscopy was carried out on the MET 5C (Altami, Saint Petersburg, Russia) microscope using a high-resolution video camera built into the device and Altami Studio 4.0 software. [

8]

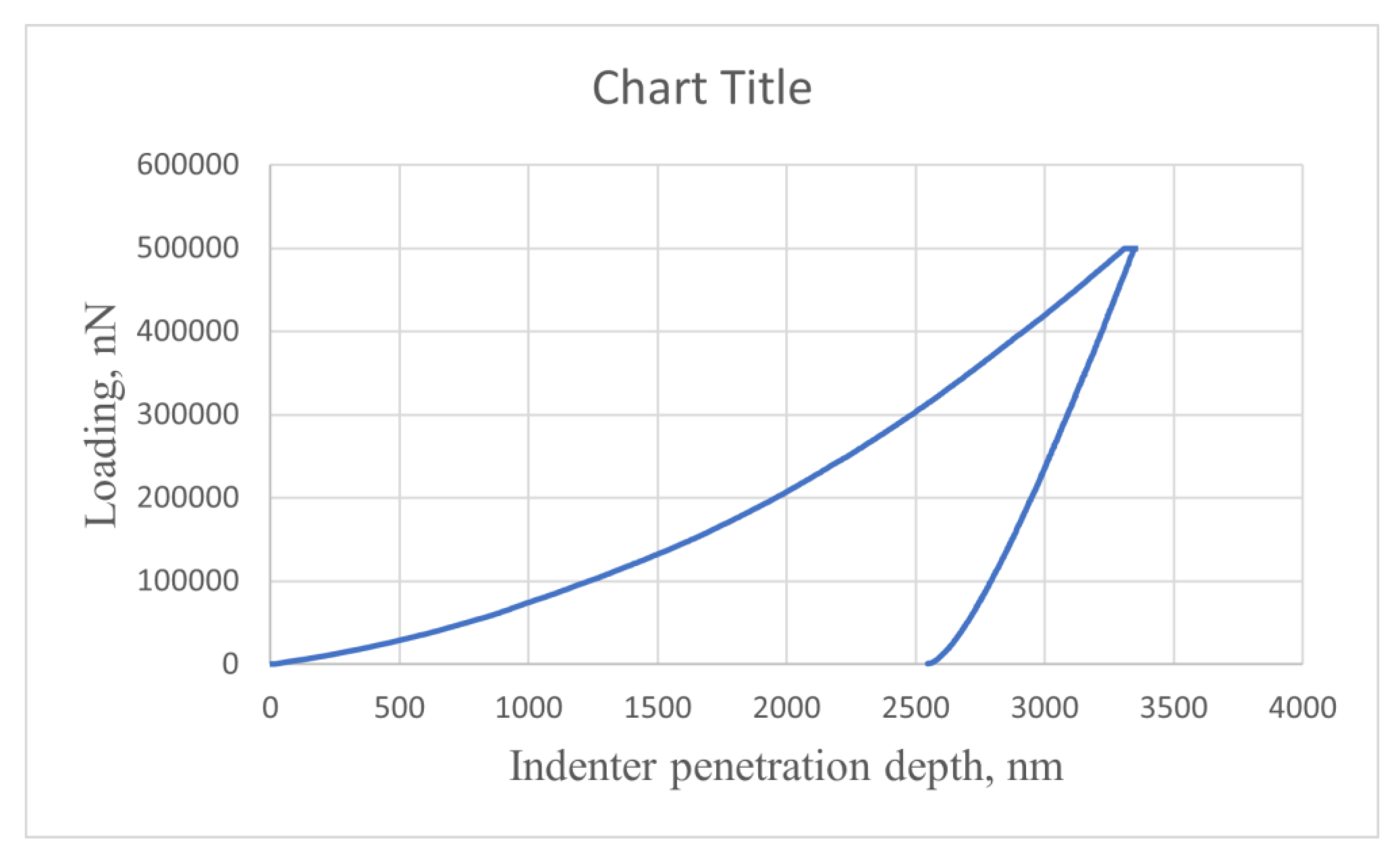

Nanohardness and Young's modulus were determined using a NanoScan-4D nanohardness tester (NauchSpecPribor, Troitsk, Russia). Instrumental indentation was performed according to ISO 14577-1:2002 [

9]. All specimens were subjected to instrumental indentation into the matrix with a load of 500 mN using a Berkovich type diamond tip. Measurements were taken across the full width of the specimen. The load/unload rate was 20 mN/s, the contact time was 20 s, and the distance between indentations was 200 μm. The number of indentations for each treatment type was 27. The experimental curves were processed using NANOINDENTATION 3.0 software from CSM Instruments (Switzerland) with a specified Poisson's ratio (0.3) and averaged over five experimental curves. Elastic recovery was defined as the ratio of elasticity to total indentation work. Fractographic studies were carried out on a KYKY EM6900 (KYKY, Beijing, China) scanning electron microscope using a secondary electron detector at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV.

Static mechanical tests were performed on an INSTRON 3382 universal testing machine (Instron, Norwood, MA, USA) at a tensile speed of 1 mm/min using flat specimens of 28 × 6 × 1 mm and a working part size of 15 × 3 × 1 mm. The number of specimens for each alloy and treatment type was 9. The processing of the test results to determine the characteristics of mechanical properties was carried out in accordance with GOST 1497-84 using INSTRON Bluehill 2.0 software. The following parameters were determined: conditional yield strength σ0.2, tensile strength σv and relative elongation δ.

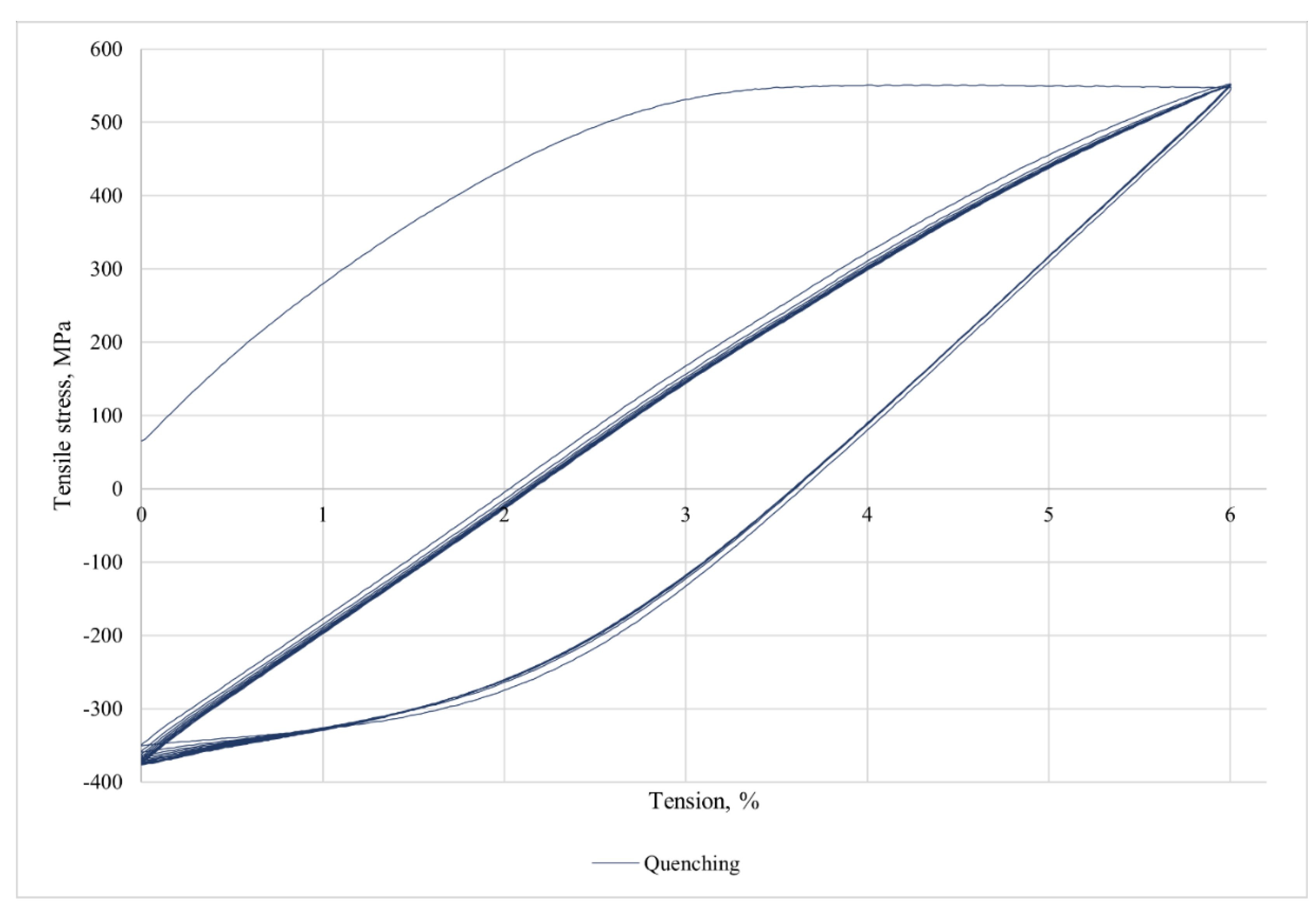

Cyclic tests to determine the hysteresis behavior of the material were performed on an INSTRON 3382 universal testing machine. For each specimen, 10 cycles were performed; in the first part of the cycle, the specimen was stretched at a rate of 1 mm/min until the working area was elongated by 8%, and in the second part of the cycle, the specimen was compressed at a rate of 1 mm/min to the original size. The best hysteresis behavior can be used to evaluate the superplasticity effect of the alloys studied. Strain measurement was performed with an additional probe mounted directly on the specimen with two clamps along the edge of the specimen work area, so that the tensile value of the specimen work area was more accurate and did not include the strain of the gripping parts of the specimen, which occurs when using tensile values from the INSTRON 3382 frame-mounted probe. The specimen dimensions were 56 × 10 × 1 mm and the workspace size was 32 × 6 × 1 mm.