1. Introduction

1.1. Hip Endoprosthesis

Orthopaedic patients, such as those experiencing pain when engaging in daily activities, possibly because of arthritis damage or sudden injury, may seek several types of treatment. This may include exercise therapy, patient education, weight reduction or even manual threapy. Treatment is coupled with pharmacological treatment with paracetamol and non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) [

1]. If such treatments are not effective, patients may seek a surgical relief of pain, total hip arthroplasty (THA). During this procedure, damaged sections of hip joint are removed and replaced with hip endoprosthesis. The aim of THA procedure is to reduce pain and improve patient’s mobility and quality of life [

2]. During hip replacement surgery, the surgeon removes the diseased or necrotic tissue from the hip joint, including bone and cartilage. The head of femor and acetabulum are replaced with artificial materials [

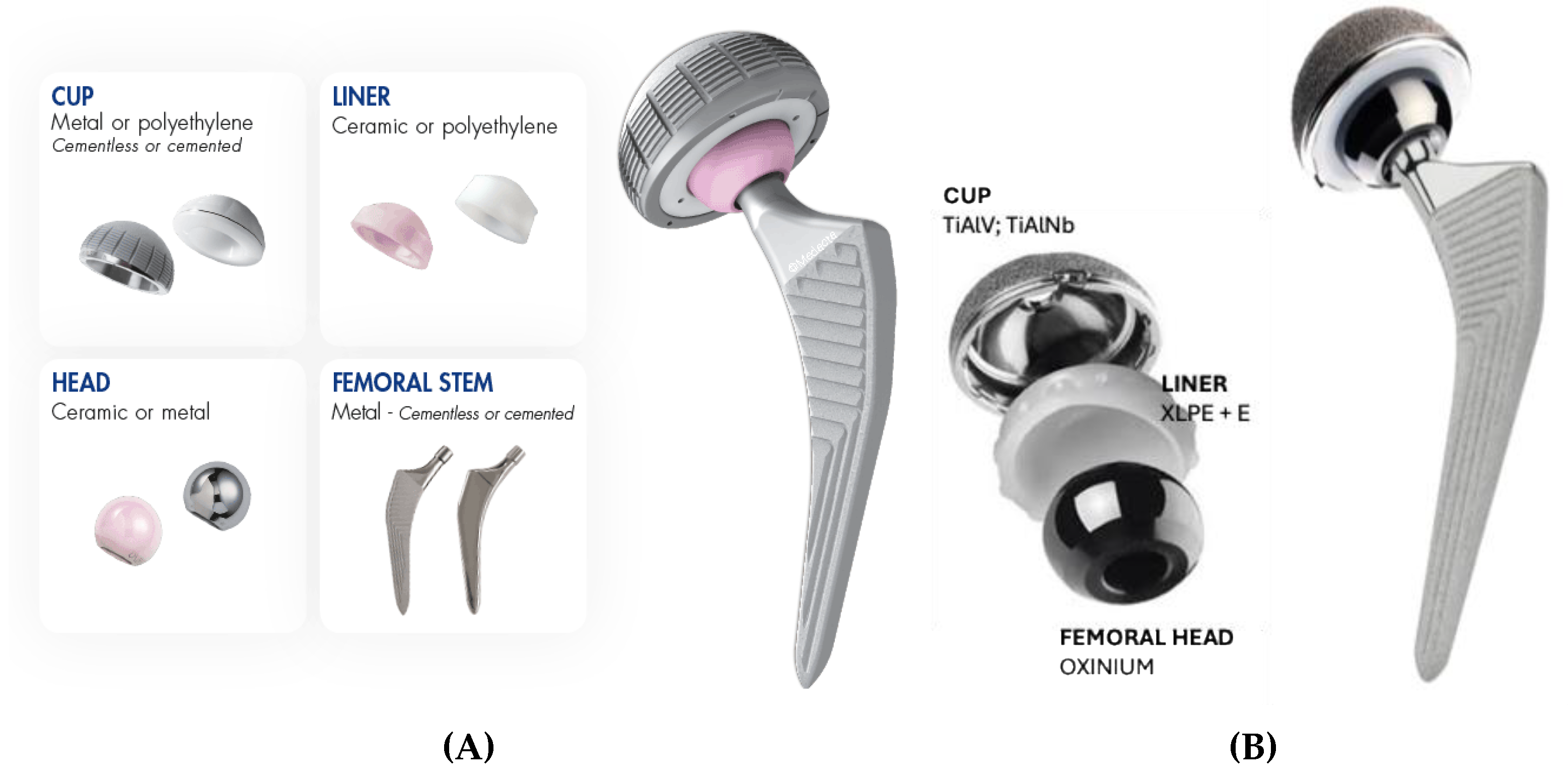

3]. Prosthetic components may either be

press fit into the bone, allowing it to grow around prosthesis, or they may be cemented into the bone. The quality and strength of patient’s bone is a factor in choosing the right fixation method [

4]. Additionally, prosthetic components may be made from several different materials, such as metal alloys and different ceramics. The materials prostheses are made of should be biocompatible and enable long-term survivability of the implant [

5].

1.2. Brief History of Hip Endoprostheses Biomaterials

Biomaterials used in medical applications, such as total hip and knee replacement endoprostheses, must meet certain specifications regarding their design and material constitution. This includes sphericity, dimensional tolerances, and surface finish [

6]. During in-body prosthesis motion, certain particle debris is formed due to friction of articular surfaces. Possible debris of such materials must be explored, as its presence can trigger an inflammatory response by the body’s macrophages. This can result in degradation of tissue surrounding the prosthesis (osteolysis) [

7]. As an increasing number of younger and more active patients are receiving total hip and knee arthroplasties, there is an increasing necessity to fabricate materials with increased longevity. With those materials, we can expect reduced bone loss and improved wear [

8].

The hip endoprosthesis is made of femoral and acetabular components. The femoral component is nowadays made of two parts – a metallic stem and a head. The acetabular component is made of a metal acetabular cup and acetabular interface. The femoral stem is made of cobalt-chromium (CoCr) or titanium alloy, though in the past it was also made of stainless steel [

9]. The material used in femoral heads was often CoCr alloy, which articulates against the acetabular component. The latter is made of metal cup and interface. Either ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) or recent highly crossed linked polyethylene HXLPE [

10], or ceramic, were used as an acetabular interface [

9].

Lately, the development of prostheses has been largely targeted towards the reduction of friction between the femoral head and the acetabular interface, thus reducing wear of articulating surfaces. Attempts to harden the femoral head CoCr surface and improve the quality of acetabular interface HXLPE have been made but have shown limited success [

11]. There have been promising results regarding the reduction of polyethylene prosthesis wear with the use of alumina and zirconia ceramics as replacements for the metal femoral head in the 1990s. However, usage of ceramic components remained limited because of the lower toughness of the material [

12].

Zr-2.5Nb is used in nuclear reactors as the pressure tube in pressurized heavy water reactors due to its superior high temperature mechanical and corrosion resistant properties. The microstructure of the as-fabricated tube comprises of

elongated α-Zr grains with continuous fine β-Zr ligaments between α/α interfaces [

10]. Oxidized zirconium (OxZr or oxinium) was then developed as an alternative material for orthopaedic prostheses. It showed improvements in resistance to roughening, frictional behavior, and biocompatibility, all related to the production of submicron debris and, consequently, osteolysis [

7].

1.2.1. Ceramics in Hip Endoprostheses

Ceramic materials for THA began being used in the previous decades. The aim was to reduce friction with polyethylene and consequent surface wear. They proved successful, showing reduced osteolysis, as well as lower revision rates [

13]. Generally, ceramic femur head on ceramic acetabular interface have showed a lower wear rate compared to metal-on-polyethylene and ceramic-on-polyethylene. This helps increase the lifespan of prosthesis and improves patient quality of life [

14].

In the late 1970s, zirconia toughened alumina (ZTA) was developed as Biolox delta, where aluminum oxide matrix consisting of approximately 80% alumina, 17% zirconia and 3% strontium oxide [

15,

16,

17]. Zirconia was added to increase the material strength and prevent the initiation and propagation of cracks. An additional toughening mechanism is created with the addition of strontium oxide, which forms a platelet type crystal to dissipate energy by deflecting cracks. Up to 25% of zirconia weight was introduced to alumina matrix, fabricating a composite material that showed increased flexural strength, fracture toughness and fatigue resistance [

18]. ZTA composite shows the more favorable crack resistance and toughness of zirconium, in addition to its excellent wear resistance, chemical and hydrothermal resistance [

5].

1.2.2. Oxidized Zirconium Zr2.5Nb Alloy (Oxinium, OxZr)

Zr-2.5Nb is widely used in nuclear reactors as the pressure tube in pressurized heavy water reactors due to its superior high temperature mechanical and corrosion resistant properties. At the end of the previous century, a new material alternative for hip endoprosthesis was introduced. It consists of a metallic zirconium alloy, Zr2.5Nb, and a smooth articulating surface of oxidized zirconium (Oxinium, OxZr). Its idea was to present the toughness of metal with the benefits of a ceramic surface [

12]. In Oxinium prosthesis, ceramic is not a coating onto metal, but rather a 4-5 μm thick diffusion surface zone of ceramic-to-metal. It is fabricated with heat treatment of metallic head in air at 500°C. The reaction transforms zirconia into a durable low-friction oxide on top of metal head. The product is therefore a metallic head with an Oxinium ceramic surface. Because the head is still mainly metallic, it does not have the same risk of fracture as a regular ceramic head [

8,

19]. In vitro studies have demonstrated that less particle debris is formed with Oxinium femoral heads,

Figure 1b, than CoCr heads when articulating with HXLPE [

20]. Oxinium heads therefore offer the potential to reduce wear and consequently increase implants longevity [

8].

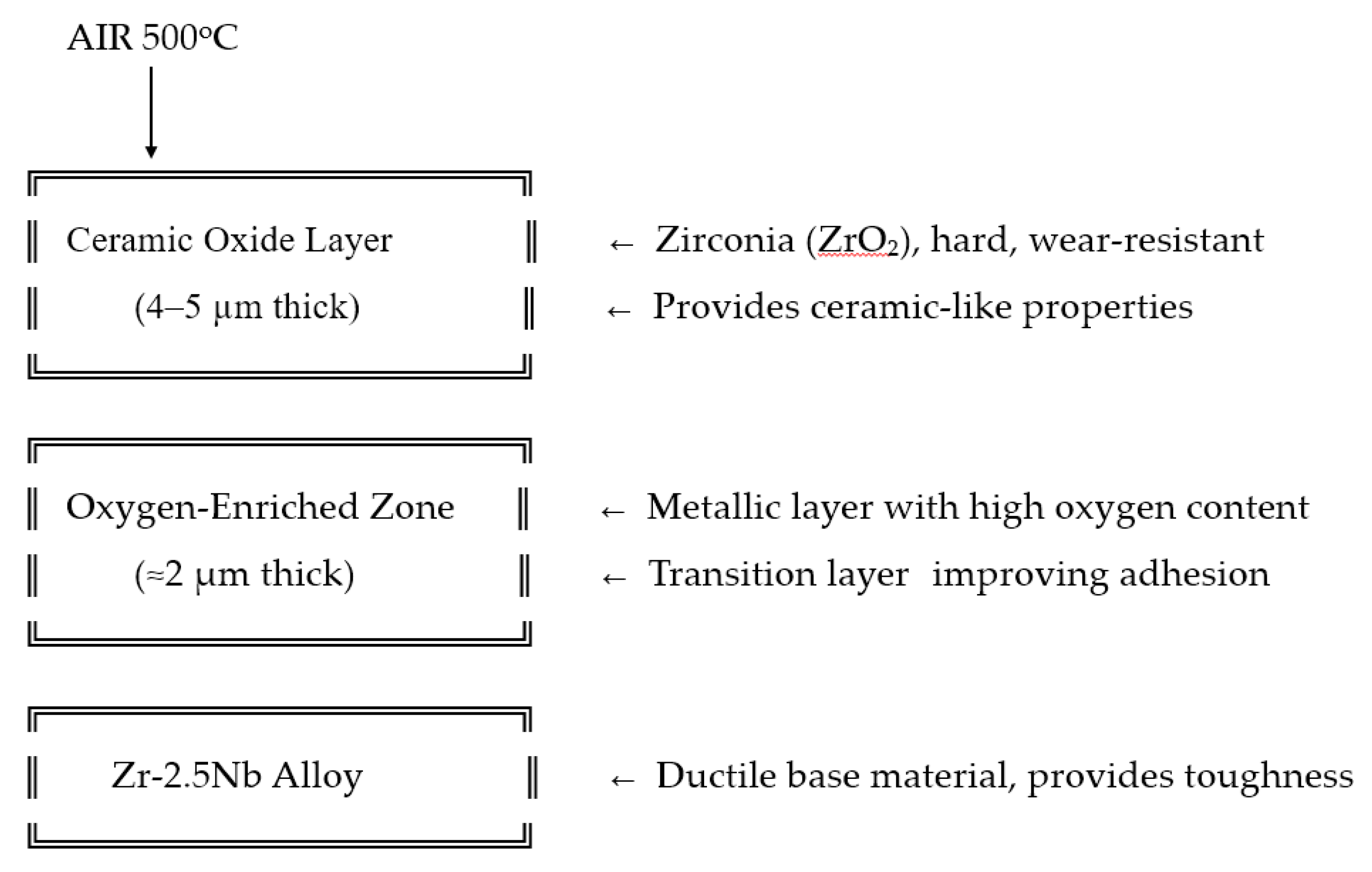

Layer Structure After Thermal Treatment:

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the formation of the ceramic-like diffusion layer on an Oxinium femoral head. The base material is a Zr-2.5Nb alloy. After final shaping, the femoral heads undergo thermal oxidation in an air atmosphere at 500 °C. This process results in the formation of a ceramic oxide surface layer approximately 4–5 µm thick, underlain by an oxygen-enriched diffusion zone approximately 2 µm thick. Beneath this lies the ductile Zr-2.5Nb metallic core, which provides toughness and structural integrity.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the formation of the ceramic-like diffusion layer on an Oxinium femoral head. The base material is a Zr-2.5Nb alloy. After final shaping, the femoral heads undergo thermal oxidation in an air atmosphere at 500 °C. This process results in the formation of a ceramic oxide surface layer approximately 4–5 µm thick, underlain by an oxygen-enriched diffusion zone approximately 2 µm thick. Beneath this lies the ductile Zr-2.5Nb metallic core, which provides toughness and structural integrity.

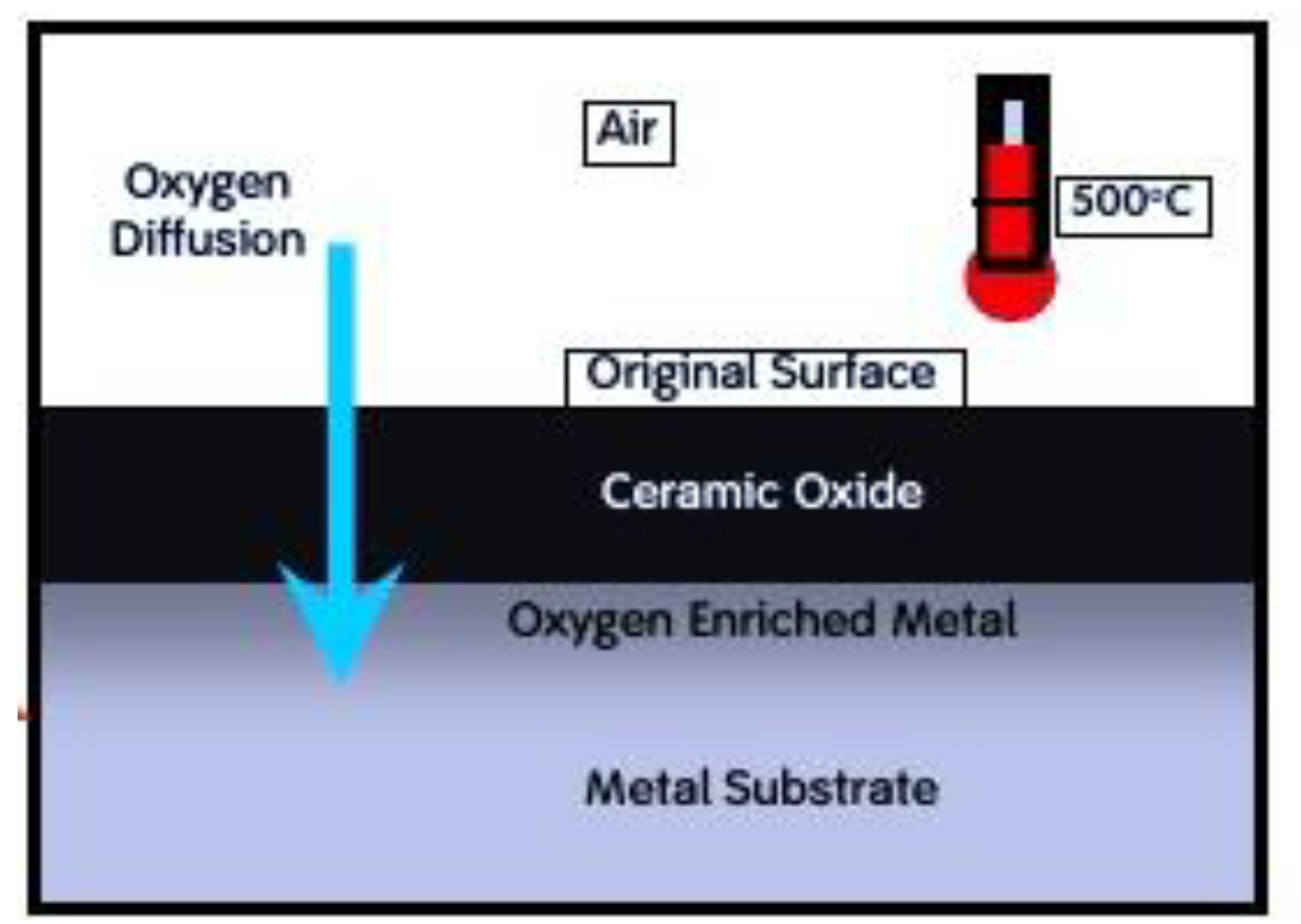

Figure 3.

Oxinium processing involves thermal treatment of the original Zr-2.5Nb alloy surface in air at 550°C. During this process, oxygen diffuses into the base material, forming a ceramic-like diffusion layer approximately 4–5 µm thick. Of this layer, around 2 µm consists of oxygen-enriched metal.

Figure 3.

Oxinium processing involves thermal treatment of the original Zr-2.5Nb alloy surface in air at 550°C. During this process, oxygen diffuses into the base material, forming a ceramic-like diffusion layer approximately 4–5 µm thick. Of this layer, around 2 µm consists of oxygen-enriched metal.

1.3. Case Report

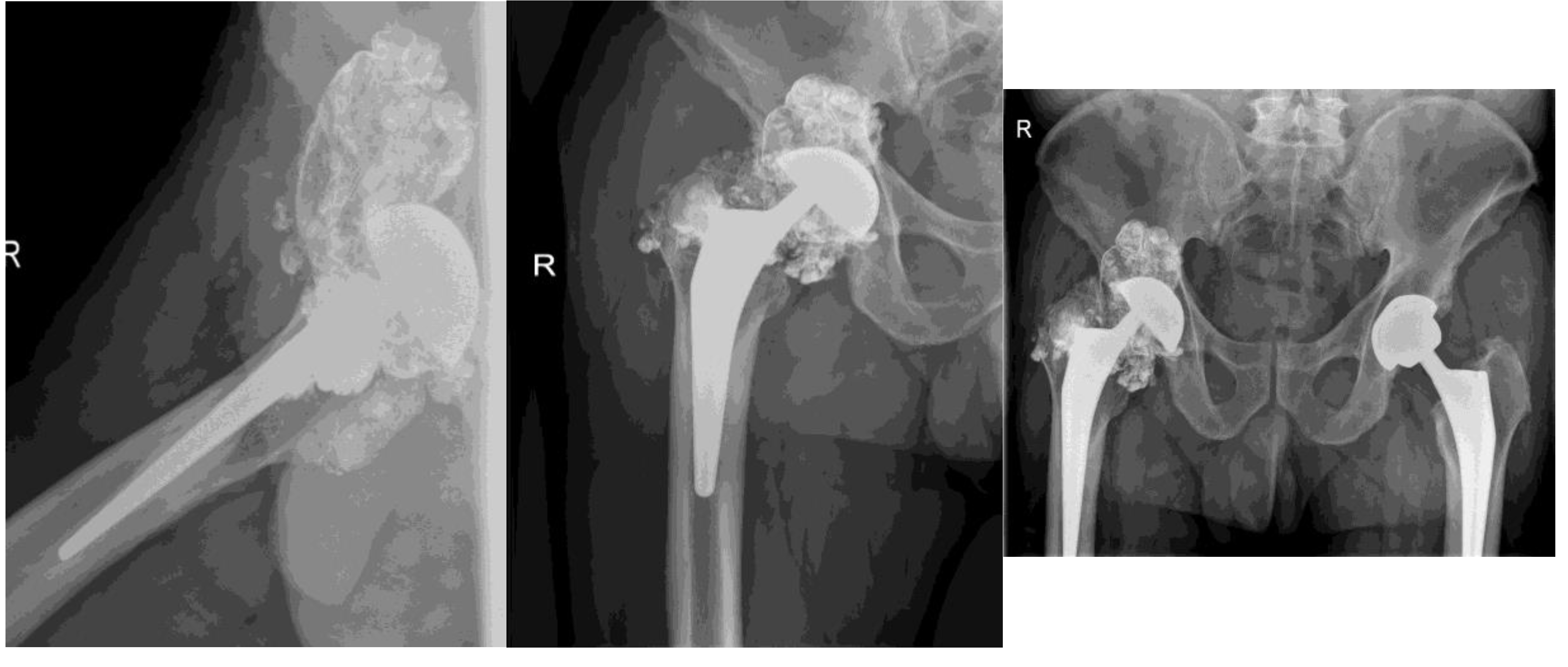

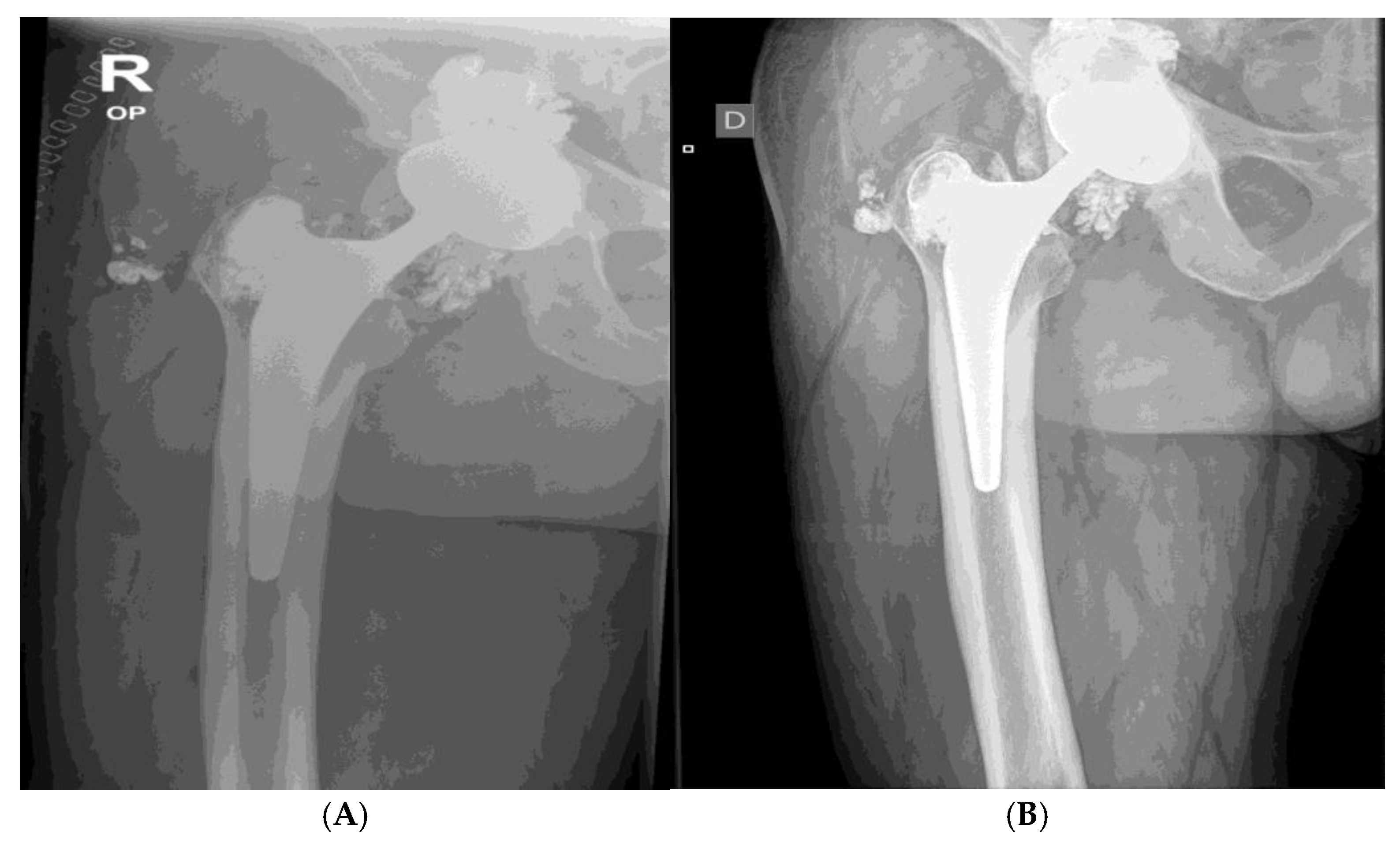

A 64-year-old male had the initial THA surgery performed 144 months prior due to hip dysplasia-induced osteoarthritis. The procedure and rehabilitation protocol were carried out in accordance with the in-clinic protocol and were uneventful. 140 months after initial surgery the patient fell in mountains and suffered a contusion on the operated side.

The initial radiographic evaluation showed no evidence of fracture or displacement of endoprosthesis components. However, in the weeks following the incident, the patient began reporting progressive worsening pain localized to the greater trochanteric region. Audible crepitus emerged shortly thereafter and became increasingly pronounced over time. 4 months after the fall, the patient presented for a follow-up evaluation, citing persistent and debilitating pain. Repeat radiographs demonstrated cranial migration of the femoral head within the acetabulum, consistent with advanced polyethylene inlay wear.

He was admitted to the hospital for revision surgery after total hip arthroplasty (THA) due to pain, limited range of motion, audible crepitus, and radiographic signs of acetabular polyethylene inlay wear,

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

X-ray shows aasymmetrical positioning of the femoral head in the acetabulum- suggesting damage and/or wear of components. Direct contact of oxinium femoral head and Ti6Al4V acetabular cup is the cause for extensive metallosis around the prosthesis – cloud like appearance around endoprosthesis. Wear of metallic components is suspected, since wear of polyethylene acetabulum liner would not be seen on x-ray, apart from asymmetric positioning of the head. Oxinium femoral head suffered severe wear, especially diffusion layer, or so called »ceramic layer«. Left hip/ prosthesis- symmetrical positioning of components and femoral head- normal x-ray.

Figure 4.

X-ray shows aasymmetrical positioning of the femoral head in the acetabulum- suggesting damage and/or wear of components. Direct contact of oxinium femoral head and Ti6Al4V acetabular cup is the cause for extensive metallosis around the prosthesis – cloud like appearance around endoprosthesis. Wear of metallic components is suspected, since wear of polyethylene acetabulum liner would not be seen on x-ray, apart from asymmetric positioning of the head. Oxinium femoral head suffered severe wear, especially diffusion layer, or so called »ceramic layer«. Left hip/ prosthesis- symmetrical positioning of components and femoral head- normal x-ray.

In

Figure 5the X-ray shows aasymmetrical positioning of the femoral head in the acetabulum- suggesting damage and/or wear of components. Direct contact of oxinium femoral head and Ti6Al4V acetabular cup is the cause for extensive metallosis around the prosthesis – cloud like appearance around prothesis. Wear of metallic components is suspected, since wear of plastic acetabulum liner would not be seen on x-ray, apart from asymmetric positioning of the head. Oxinium femoral head suffered severe wear especially diffusion layer, or so called »ceramic layer«

A 31. 3. 2021. Xray after revision surgery. Extensive metallosis was found and mosty removed. Damaged femoral head, polyethylene and acetabular cup were exchanged.

Proper symetrical positioning of components- after femoral head and acetabular componets were exchanged. A lot of metall infused soft tissues were removed- note diminished cloud around the prothesis.

B Routine x-ray at follows up 2 months after surgery- no dynamics

The patient was satisfied with the surgical outcome and reported only slight limitations in range of motion (ROM). He works as a painter (residential and commercial), and occasionally experiences pain following heavy work or lifting heavy objects. No other complaints were reported.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials and Methods

The initial implant was Implantcast Eco Fit femoral stem 12.5mm cementless made of Ti6Al4V alloy, 12/14 taper for femoral head. Smith & Nephew oxinium femoral head φ 32 mm was used. Implantcast acetabular cup φ 52 mm; cementless Ti6Al4V with Implantcast HXLPE φ 41mm inlay were implanted initially.

2.1. Sample Preparation

The retrieved Oxinium head samples were prepared for XPS and hardness measurements, and the new Oxinium head was processed in the same manner. The heads were sectioned into several parts using a Struers saw to obtain suitable samples for XPS analysis. Of ceramic-like surface. The surface layer, approximately 4–5 µm thick, is extremely hard, whereas the retrieved worn oxinium surface is slightly softer while the core material (Zr2.5Nb) is relatively soft. The metallographic sample was prepared using standard methods of grinding and polishing for hardness profile measurements.

2.2. Microbiological Analysis

All tissue samples collected during surgery were processed with standard microbiological protocol using both PCR and standard cultures for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, also Cutibacterim Acnes presence was observed. All implants removed during surgery were processed using sonication followed by microbiological analyses at the Institute for Microbiology, UMC Ljubljana, Slovenia. Both PCR and standard cultures for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria were used. Following the microbiological analysis, implants were cleaned and sterilized (autoclaving Coatings KA). All microbiology findings were negative; no presence of bacteria was found.

2.3. XPS surface Analysis

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) is a powerful analytical technique used to investigate the surface of materials, offering valuable insights into both their elemental and chemical composition. XPS is highly surface-sensitive, typically analyzing only the top ~10 nanometers of a sample. This exceptional surface specificity, combined with its ability to quantify surface chemistry, makes XPS an essential tool for materials characterization and surface analysis. The main goal of XPS in our investigation was obtain surface composition in 2-4nm surface layer, identify chemical oxidation states of elements/compounds and 0-40 nm depth distribution of elements of new and retrieved oxinium acetabular cup of hip endoprosthesis.

2.4. Microindentation- Hardness Measurements

Hardness measurements of ceramic-like diffusion layer and worn surface were conducted by micro-indentation using Fischerscope H100C instrument, at the load of 0.005 N. The hardness profile of bulk material was measured by Vickers hardness instrument Instron Tukon 2100B using load 1N and 0,01N.

3. Results

3.1. Hardness Measurements

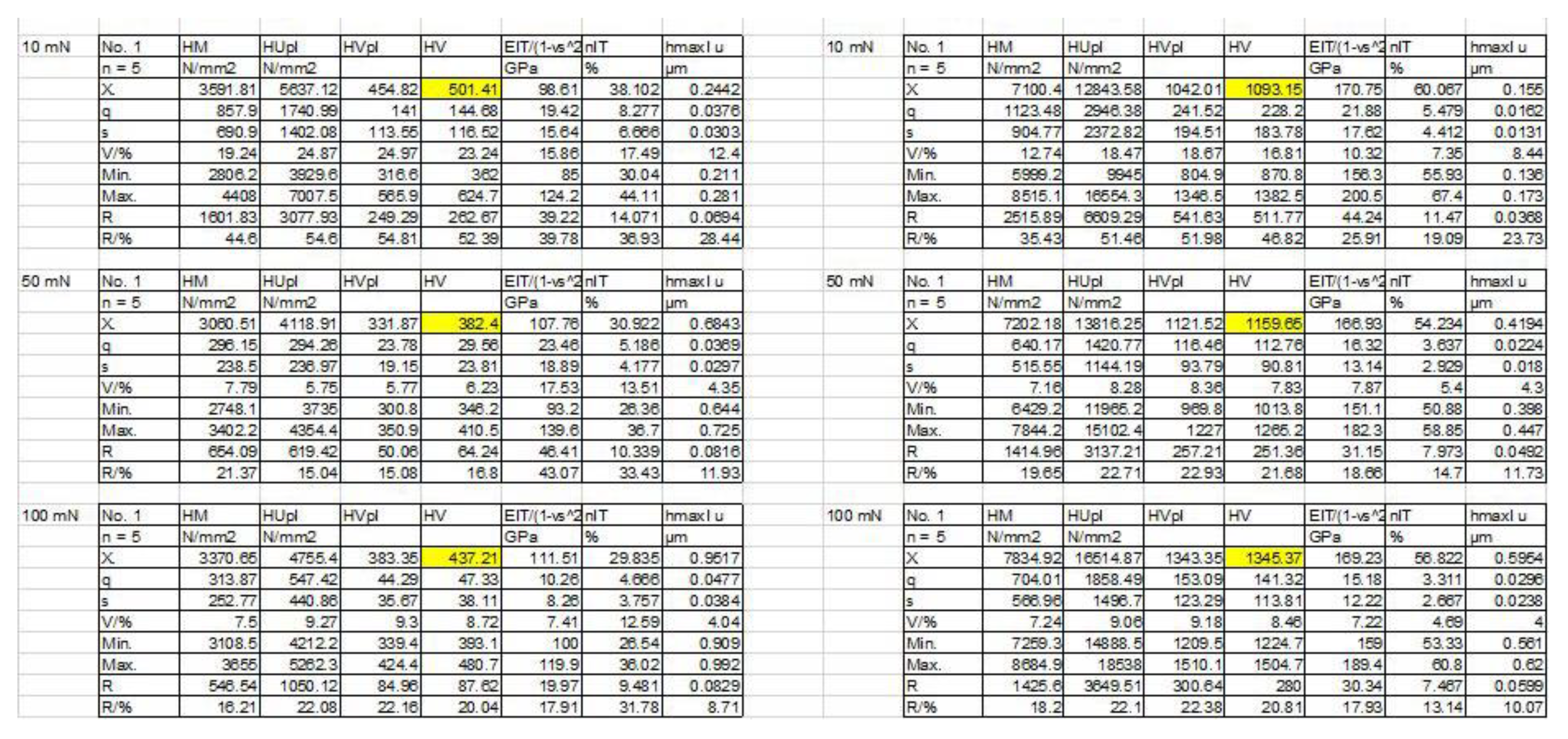

Hardness measurement of ceramic like diffusion layer vs worn layer results

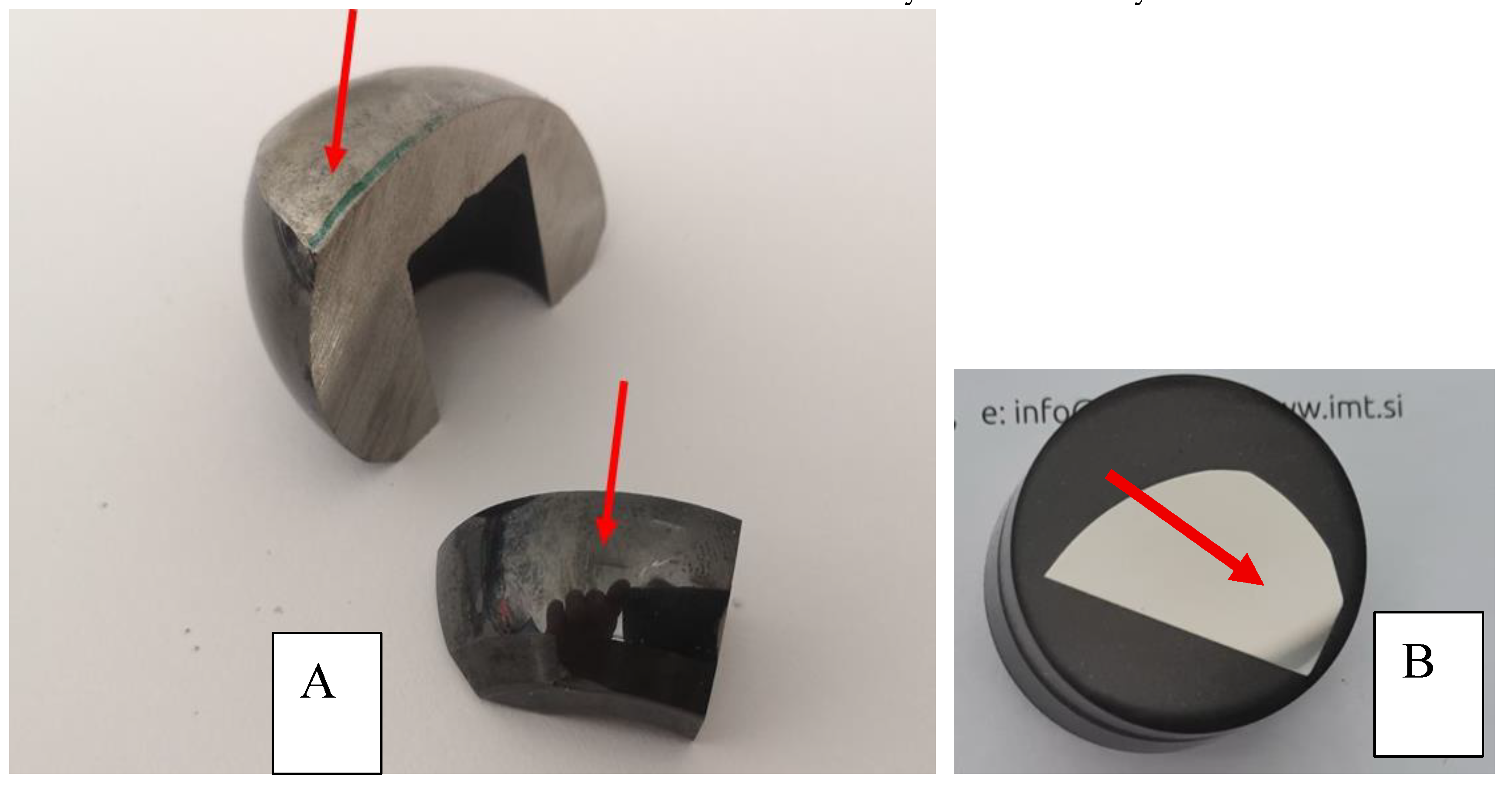

Figure 6.

(A)sample of oxinium retrieved femoral head HV on the region with worn surface 383HV and on the diffusion layer 1159 HV as shown in

Figure 5 red arrow indicated the place of measurements. (B) metaloghic sample cross section of oxinium retrieved femoral head was used for hardness.

Figure 6.

(A)sample of oxinium retrieved femoral head HV on the region with worn surface 383HV and on the diffusion layer 1159 HV as shown in

Figure 5 red arrow indicated the place of measurements. (B) metaloghic sample cross section of oxinium retrieved femoral head was used for hardness.

- A.

The results of micro indentation hardness measurements are given in

Figure 7 for retrieved, worn surface and new unused oxinium femoral heads

- B.

The results of hardness measurements of bulk Zr2.5Nb metal alloy are given in

Table 1. The loads used were 1N and 0.01. The hardnes profile of bulk Zr2.5Nb is presented in

Table 2

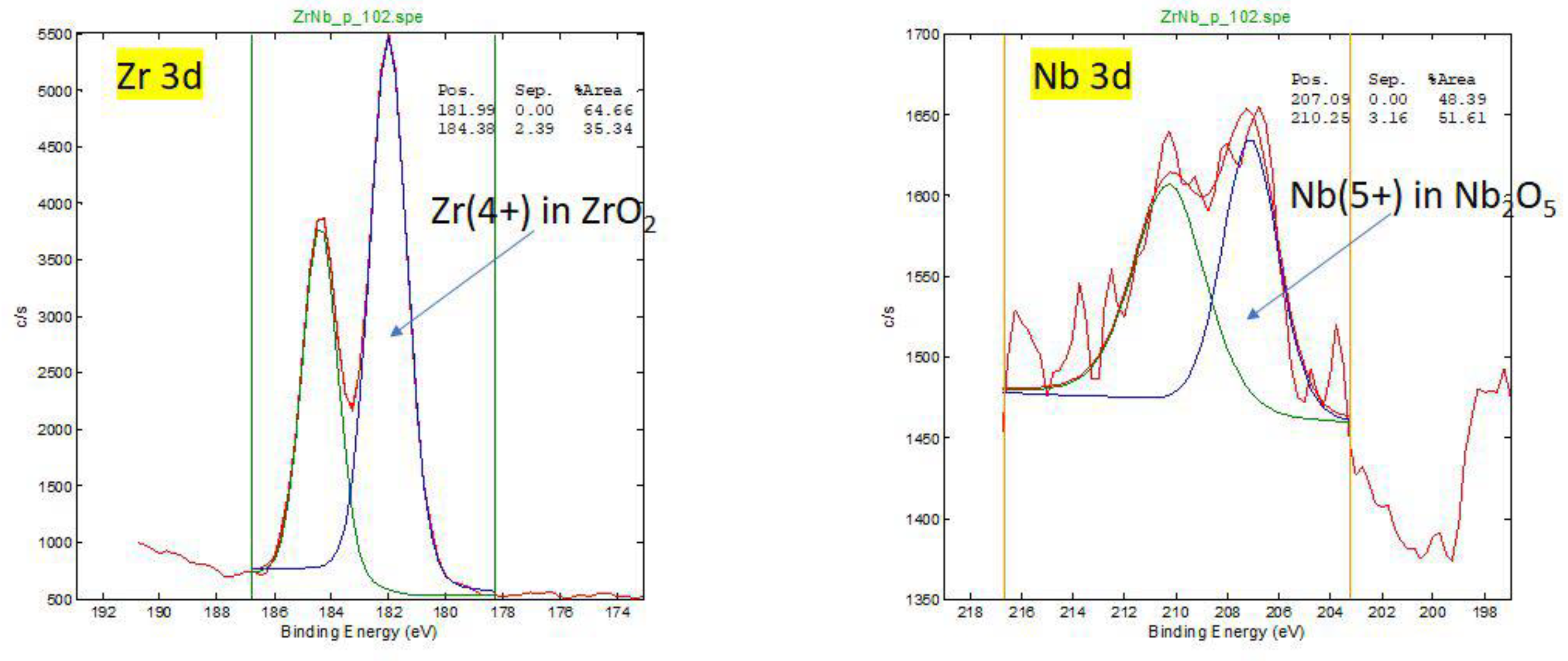

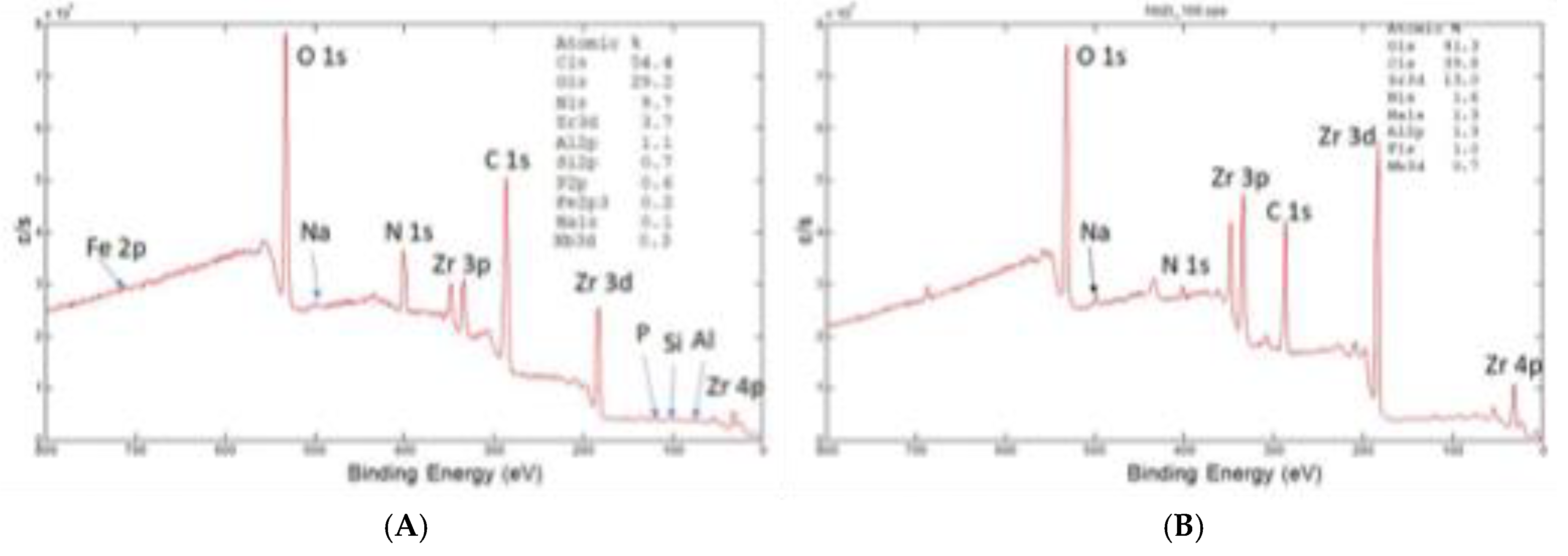

3.1. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

XPS measurements were performed on the worn surface of retrieved and new femoral heads, as indicated in

Figure 7. Red arrows indicate the place of XPS analysis on worn surface of retrieved femoral head and on the surface of the new oxinium femoral head.

Figure 8.

Red arrows indicate the place of XPS analysis on worn surface of retrieved.

Figure 8.

Red arrows indicate the place of XPS analysis on worn surface of retrieved.

Femoral head and on the new one

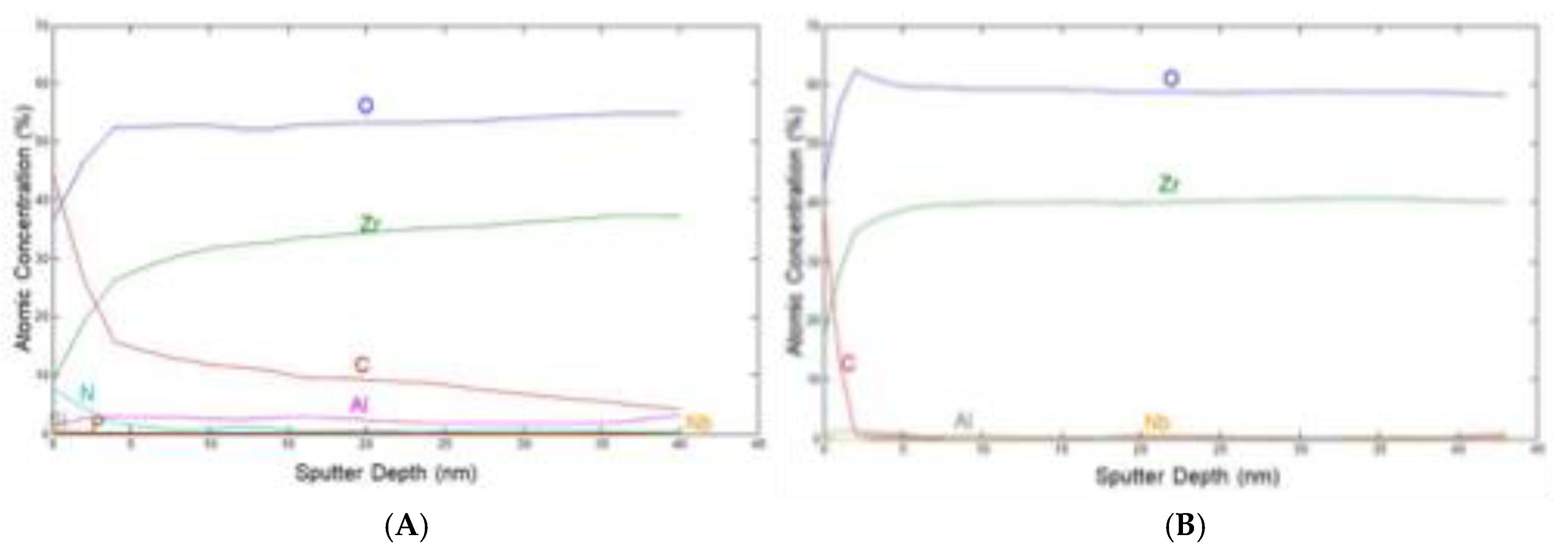

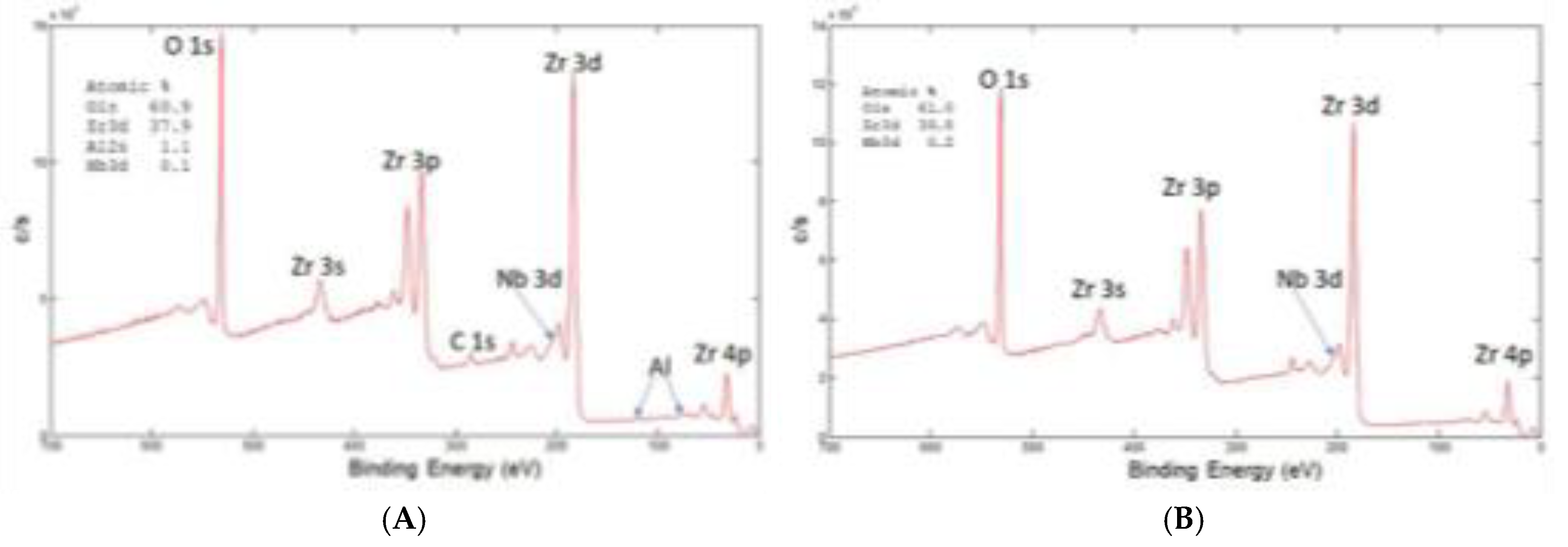

Surface composition in 2-4 nm surface layer of new and retrieved nondamaged and worn oxidized Zr2.5Nb diffusion layer is shown in

Figure 4

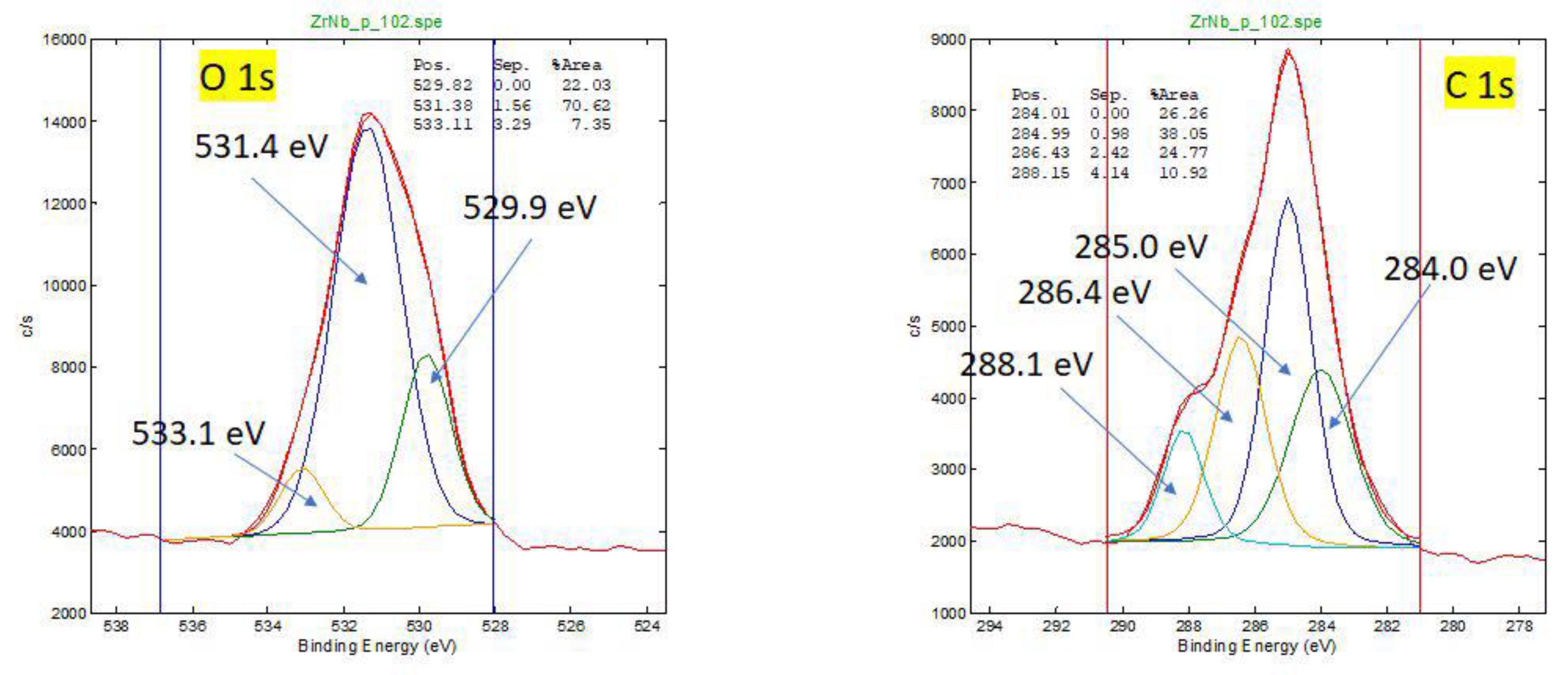

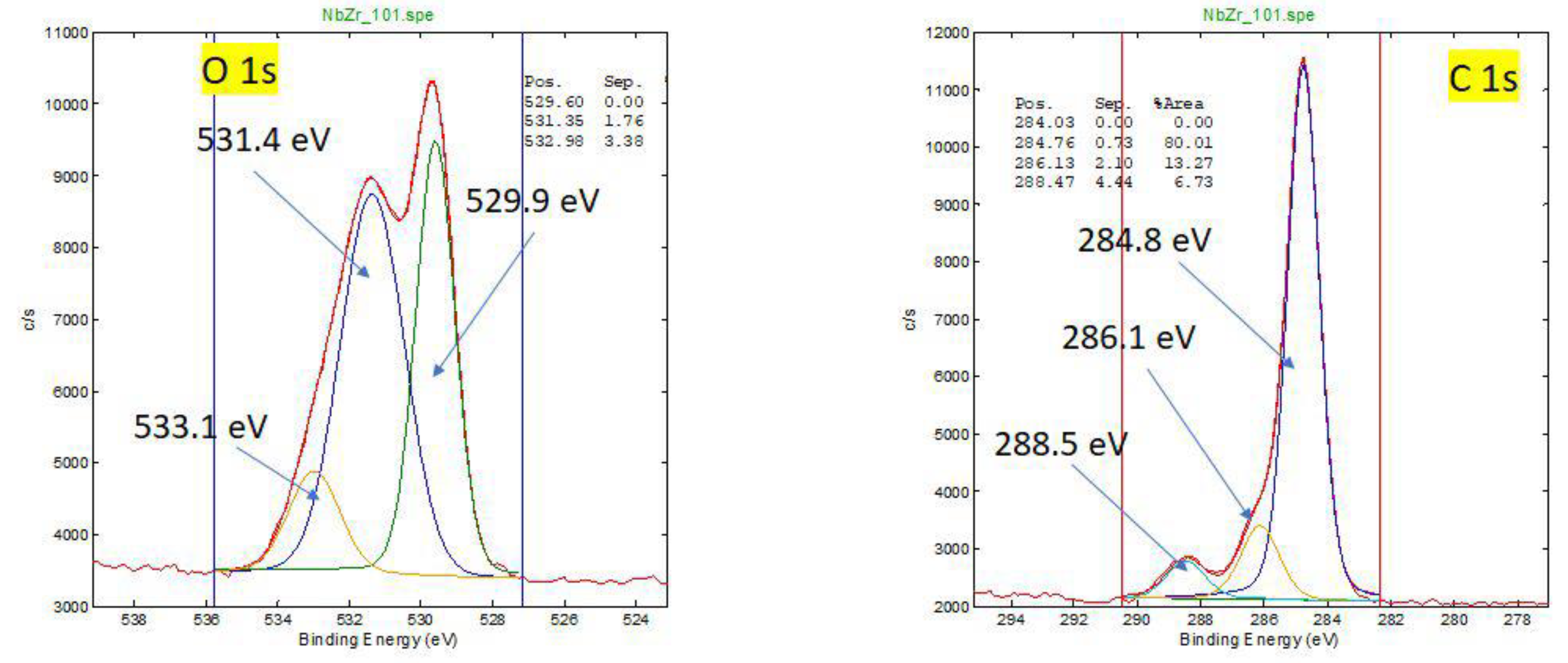

XPS spectrum at the surface of retrieved and new oxinium ceramic like diffusion layer of oxinium femoral heads is shown in

Figure 9 (A) and (B). Surface composition , shown in

Figure 4, of retreived femoral oxinium head show the main phase is ZrO

2, at the surface is present 0.3%Nb, carbon is posibly from HXLPE or contamination, there is also 10 %of N, oorigin may be from soft tissue near hip endoprostheses. We found Al 1.1%; Si0.1%, Fe0.2%, P 0,6% and Na 0.1%. For comparison we investiaged the new unused femoral head and the surface composition was similar the main phase is ZrO

2 with 0.7% Nb at the surface, C is from contamination and present elements are Al 1.3%; F1.0%; and Na 1.3%

Figure 10 represent the XPS depth profile of 0-40 nm of retrieved (A) and new oxinium femoral heads, component of hip endoprosthesis (B).

XPS spectra at the depth of 40 nm of retrieved (A) and new(B) oxinium femoral heads are shown in

Figure 11.

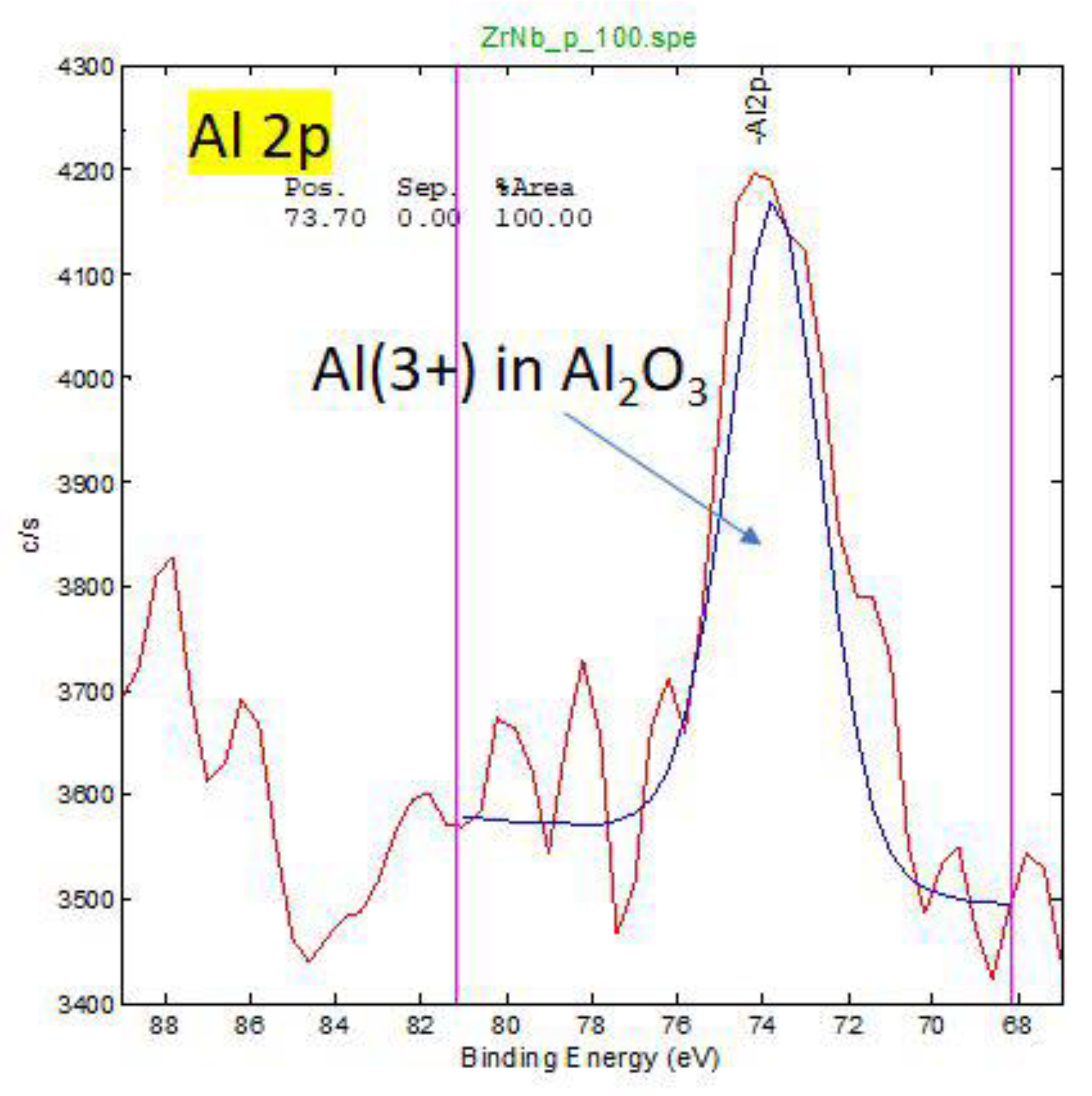

Surface composition shown in

Figure 10 at the depth of 40 nm show XPS spectra (A) retrieved and (B) new femoral oxinium. Composition at 40 nm presented main phase ZrO

2, 0.1 at.% Nb present and 1.1 at.% of Al.

Figure 11 show XPS spectra of new oxinium. ZrO

2 is the main phase in subsurface region, Al (~ 2-3 at.%) present in subsurface region.

Carbon decreasing strongly from surface (only very thin contamination of 1-2 nm). Minor elements like Nb (0.2 at.%) are present in the layer.

XPS analysis show that the main phase on the surface and in the subsurface of femoral heads is ZrO2, where Zr is in the (4+) oxidation state. Small amount of Nb (0.1-0.3 at. %) in Nb (5+) oxidation state is present in surface region. Aluminium, Al, is also present in the surface region (1-3 at. %)

For worn diffusion layer, carbon on the surface may be related to interaction with the HXLPE or from contamination.

For a new oxinium head, the carbon surface layer is very thin (1-2 nm), and it is due to contamination.

A significant amount of nitrogen (10 at. %) is present on the surface of the retrieved femoral head (worn part of oxinoum), probably indicating the rest of the soft tissue. Other elements are also present on the surface, like Fe, P, Si, Na, on worn coating. On the new oxinium femoral head elements O, C, Zr, Nb, and traces of Al, F are present.

4. Discussion

Several authors have reported that dislocated Oxinium femoral heads can undergo rapid, accelerated wear, potentially resulting in catastrophic implant failure [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Although the Oxinium surface is reported to be twice as hard as that of cobalt-chromium (CoCr) femoral heads [

22], the underlying substrate is significantly softer, as demonstrated by Kop et al. [

25] and corroborated by our own hardness measurements. These findings confirm a very hard ceramic-like oxide surface layer over a relatively soft metallic core.

In our patient, despite adherence to standard diagnostic protocols, dissociation of the polyethylene acetabular liner went undetected for 140 months following the primary total hip arthroplasty (THA). This delay likely contributed to progressive mechanical damage. Although Oxinium femoral heads offer surface hardness superior to CoCr counterparts, their clinical performance is critically dependent on the integrity of the polyethylene liner and its interface with the head. Damage or dissociation of the liner can lead to direct articulation between the femoral head and the acetabular cup, accelerating wear and deformation of the Oxinium surface.

It is well established that polyethylene wear, particularly at the nanoscale, can result in “polyethylene disease,” marked by the release of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE) particles. These nano-sized particles can trigger adverse local tissue reactions, including pseudotumor formation and osteolysis. To address this, highly cross-linked polyethylene (HXLPE) enhanced with vitamin E has been developed, demonstrating improved oxidative stability and significantly greater wear resistance compared to conventional UHMWPE.

Multiple case reports support the notion that damaged Oxinium implants can fail prematurely. Ozden et al. described three patients who underwent revision surgery 3–7 years after their initial THA with Oxinium femoral heads. These patients, who had been asymptomatic initially, presented with pain, squeaking or a shattering-glass sound during ambulation, and limited hip movement. Revision surgery revealed broken ceramic liners, severe deformation of the Oxinium heads, and tissue metallosis, although the metal femoral stems remained stable [

21]. Similarly, Frye et al. documented eccentric positioning and deformation of Oxinium heads, polyethylene liner dissociation, and visible wear debris in patients with comparable symptoms prior to revision [

23].

Jaffe et al. further demonstrated that damaged Oxinium heads exhibit a 50-fold increase in wear rate compared to undamaged counterparts, particularly after contact with the metallic acetabular shell during dislocation or similar high-stress events [

10]. These findings raise concerns about the reliability of Oxinium heads in patients with a higher risk of dislocation, challenging the perceived benefits of improved wear performance and prolonged implant longevity.

Additional case studies reinforce these concerns. Tribe et al. reported a patient who, after a dislocation episode, developed pain, instability, and squeaking in the hip. Revision revealed a cracked and displaced polyethylene liner, extensive metallosis, and severe edge wear on the Oxinium femoral head [

24]. Likewise, Gibbon et al. described a unique case in which a fractured trochanteric fixation wire, following multiple dislocations, migrated into the acetabular cup and caused macroscopic damage to the Oxinium head. Once the hard oxide surface was compromised, the softer underlying alloy experienced rapid wear, resulting in severe tissue staining and implant degradation [

10,

24].

These cases collectively demonstrate that while Oxinium heads may offer theoretical advantages in terms of surface hardness and wear resistance, their actual performance is highly contingent upon maintaining the structural integrity of surrounding components. Once compromised, Oxinium heads can degrade rapidly, generating particulate debris and leading to osteolysis, tissue reaction, and poor patient outcomes.

5. Conclusions

While in vitro studies have highlighted Oxinium as a promising prosthetic material with reduced surface friction, lower wear rates, and decreased debris formation—particularly advantageous for younger and more active patients—clinical experiences have revealed significant limitations.

Numerous case reports have documented severe wear of the Oxinium ceramic-like surface following mechanical damage, often related to joint dislocation or contact with foreign objects. Patients frequently reported audible symptoms such as squeaking or a “glass-shattering” sound prior to revision surgery. In such cases, revision was invariably necessary due to accelerated implant degradation and surrounding tissue damage.

Our XPS analysis confirms that the Oxinium surface is approximately twice as hard as cobalt-chromium (CoCr) femoral heads, and that the ceramic-like diffusion layer provides excellent initial properties. However, the critical weak point appears to be the interface between the Oxinium head and highly cross-linked polyethylene (HXLPE) liners. While this interface shows potential, further biomechanical and clinical studies are needed to optimize implant design, enhance durability, and improve surgical protocols to reduce the risk of catastrophic wear and failure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.K., E.K., S.T.K., J.K., M.J., and M.D.; methodology, B.K., E.K., S.T.K., J.K., M.J., and M.D.; validation, B.K.;E.K.; S.T.K; J.K.; M.J.; and M.D.; formal analysis, B.K.; J.K.; and M.J investigation, B.K.;E.K.; S.T.K; J.K.; M.J.; and MD.; resources, B.K.;E.K.; S.T.K; J.K.; M.J.; M.D..; data curation B.K.;E.K.; S.T.K; J.K.; M.J.; M.D.;writing—original draft preparation B.K.; E.K.; M.J. and M.D. —review and editing, B.K.; E.K.; S.T.K., M.J. and M.D..; supervision, B.K.; E.K.; S.T.K; J.K.; M.J.; and M.D..; project administration, B.K.; E.K.; S.T.K; J.K.; M.J.; and M.D..; funding acquisition, B.K., J.K., and M.J.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research was funded by Slovenian Research Agency -ARIS L3-2621 project, and Slovenian Research Agency -ARIS grant P2-0082 and the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery of University Medical Centre Ljubljana, Slovenia- UMC: Tertiary project No. 20250128 and -UMC Tertiary project 20250132.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of (protocol code KME RS (Case No. 0120-121/2023/6) date of approval November 2023).” for studies involving humans.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Borut Žužek from the Institute of Metals and Technology, Ljubljana, Slovenia, for providing bulk hardness measurements. Special thanks to Ms. Tina Sever, B.Sc. in Physics, also from the Institute of Metals and Technology, Ljubljana, Slovenia, for sample preparation. The authors also thank Dr. Alojz Drnovšek from the Jožef Stefan Institute, Ljubljana, Slovenia, for performing micro-indentation hardness measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.”

Appendix A

Figure A1.

HR (High resoluyion) XPS spectra for oxidation states of Zr and Nb of retrieved oxinium femoral head. On the surface Zr is in 4+ oxidation state in ZrO2 and Nb is in 5+ oxidation state in Nb2O5.

Figure A1.

HR (High resoluyion) XPS spectra for oxidation states of Zr and Nb of retrieved oxinium femoral head. On the surface Zr is in 4+ oxidation state in ZrO2 and Nb is in 5+ oxidation state in Nb2O5.

Figure A2.

HR XPS spectra for oxidation states of O and C for retrieved oxinium femoral head. Different oxidation states of O and C atoms on surface (oxides, polymer, contamination CO2 adsorption).

Figure A2.

HR XPS spectra for oxidation states of O and C for retrieved oxinium femoral head. Different oxidation states of O and C atoms on surface (oxides, polymer, contamination CO2 adsorption).

Figure A3.

HR XPS spectra for oxidation states of Al for retrieved oxinium femoral head. On the surface Al is in 3+ oxidation state in Al2O3.

Figure A3.

HR XPS spectra for oxidation states of Al for retrieved oxinium femoral head. On the surface Al is in 3+ oxidation state in Al2O3.

Figure A4.

HR XPS spectra for oxidation states of O and C for new oxinium femoral head.

Figure A4.

HR XPS spectra for oxidation states of O and C for new oxinium femoral head.

References

- E. Poulsen, H. W. Christensen, E. M. Roos, W. Vach, S. Overgaard and J. Hartvigsen, “Non-surgical treatment of hip osteoarthritis. Hip school, with or without the addition of manual therapy, in comparison to a minimal control intervention: Protocol for a three-armed randomized clinical trial,” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, vol. 12, p. 88, 2011.

- Mayo Clinic, “Mayo Clinic: Hip replacement,” 22 April 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/hip-replacement/about/pac-20385042. [Accessed 2025].

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, “Hip Replacement Surgery,” August 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/hip-replacement-surgery. [Accessed 2025].

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, “Total Hip Replacement,” June 2020. [Online]. Available: https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/treatment/total-hip-replacement/. [Accessed 2025].

- M. Merola and S. Affatato, “Materials for Hip Prostheses: A Review of Wear and Loading Considerations,” Materials (Basel), vol. 12, no. 3, p. 495, 2019.

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration, “Recognized Consensus Standards: Medical Devices,” 29 May 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfStandards/detail.cfm?standard__identification_no=42378.

- G. Hunter, W. M. Jones and M. Spector, “Oxidized Zirconium,” Total Knee Arthroplasty, pp. 370-377, 2005.

- V. Good, K. Widding, G. Hunter and D. Heuer, “Oxidized zirconium: a potentially longer lasting hip implant,” Materials & Design, vol. 26, no. 7, pp. 618-622, 2004.

- G. Baura, Total hip prostheses, Academic Press, 2021, pp. 451-482.

- E. Gibon, C. Scemama, B. David and M. Hamadouche , “Oxinium femoral head damage generated by a metallic foreign body within the polyethylene cup following recurrent dislocation episodes,” Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research, vol. 99, no. 7, pp. 865-869, 2013.

- M. Innocenti, R. Civinini, C. Carulli, F. Matassi and M. Villano, “The 5-year Results of an Oxidized Zirconium Femoral Component for TKA,” The Association of Bone and Joint Surgeons, vol. 468, no. 5, pp. 1258-1263, 2009.

- A. Salehi and G. Hunter, “Laboratory and Clinical Performance of Oxidized Zirconium Alloy,” Clinical Cases in Mineral and Bone Metabolism, vol. 7, no. 3, p. 169, 2010.

- G. Willmann, “Ceramics for total hip replacement--what a surgeon should know,” Orthopedics, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 173-177, 1998.

- S. Affatato, M. Goldoni, M. Testoni and A. Toni, “Mixed oxides prosthetic ceramic ball heads. Part 3: effect of the ZrO2 fraction on the wear of ceramic on ceramic hip joint prostheses. A long-term in vitro wear study,” Biomaterials, vol. 22, no. 7, pp. 717-723, 2001.

- M. Hamadouche and L. Sedel. Ceramics in orthopaedics. The Journal of bone and joint surgery 2000, 82, 1095–1099. [Google Scholar]

- C. Piconi, G. Maccauro, F. Muratori and E. Brach Del Prever. Alumina and zirconia ceramics in joint replacements. Journal of applied biomaterials & biomechanics 2003, 1, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- A. H. De Aza, J. Chevalier, G. Fantozzi, M. Schehl and R. Torrecillas. Crack growth resistance of alumina, zirconia and zirconia toughened alumina ceramics for joint prostheses. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. Affatato, R. Torrecillas, P. Taddei, M. Rocchi, C. Fagnano, G. Ciapetti and A. Toni, “dvanced nanocomposite materials for orthopaedic applications. I. A long-term in vitro wear study of zirconia-toughened alumina,” Journal of biomedical materials research, vol. 78, no. 1, pp. 76-82, 2006.

- P. Hernigou, A. Nogier, O. Manicom, A. Poignard, L. De Abreu and P. Filippini. Alternative femoral bearing surface options for knee replacement in young patients. The Knee 2004, 11, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- V. Good, M. Ries, R. L. Barrack, K. Widding, G. Hunter and D. Heuer, “Reduced wear with oxidized zirconium femoral heads,” The Journal of bone and joint surgery., vol. 85, no. 4, pp. 105-110, 2003.

- V. E. Ozden, N. Saglam, G. Dikmen and I. R. Tozun. Oxidized zirconium on ceramic; Catastrophic coupling. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research 2017, 103, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- W. L. Jaffe, E. J. Strauss, M. Cardinale, L. Herrera and F. J. Kummer, “Surface oxidized zirconium total hip arthroplasty head damage due to closed reduction effects on polyethylene wear,” Arthroplasty, vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 898-902, 2009.

- B. M. Frye, K. R. Laughery and A. E. Klein. The Oxinium Arthrogram: A Sign of Oxidized Zirconium Implant Failure. Arthroplasty Today 2021, 8, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E. Gibon, C Scemama, B David, M Hamadouche. Oxinium femoral head damage generated by a metallic foreign body within the polyethylene cup following recurrent dislocation episodes Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013 Nov;99(7):865-9. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Kop, C. Whitewood, D.J.L. Johnston. Damage of oxinium femoral heads subsequent to hip arthroplasty dislocation three retrieval case studies. J Arthroplasty,2007 , 22 pp. 775-779.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).