1. Introduction

In the current highly volatile work environment, retention of employees by building their commitment is a key challenge faced by managers. Therefore, there is continuous research attention on finding ways of building employee commitment. Committed employees are emotionally attached to the organization they work for and are willing to work for a longer future period (Uddin et al., 2019), and they contribute to higher performance (Baron & Chou, 2016) as well as a greater level of effectiveness and efficiency (Bartuseviciene and Sakalyte, 2013). The past literature generally indicates that commitment has a significant positive effect on employees’ rewards, turnover, efficiency, and performance (Behziun, Abdolazimi and Sahranavard, 2016; Nwankwo, Orga, and Abel,2019; Tett and Meyer 1993; Barber et al.,1999). In line with this argument, the scholars who conduct research on commitment claim that the affective and normative components of commitment positively relate to employee efficiency whereas continuance commitment negatively relates to employee efficiency (Giedrė & Auksė, 2013; Salman, Pourmehdi, and Hamidi, 2014). In contrast, some scholars have found that the relationships between job commitment, work efficiency, and performance are not significant (Mowday et al.,1982; Mthieu and Zajac, 1990). For example, some studies report that continuance commitment does not have a significant relationship with employee efficiency (Rumaizah et al.,2021, Mowday et al.,1982; Mthieu and Zajac, 1990). As some of the meta-analyses report, the reason for these mixed results is due to the existence of unexplained variance in this relationship (e.g., Jaramillo, Mulki, & Marshall, 2005; Mathieu & Zajac, 1990; Sungu, Weng, & Xu, 2019; Wright & Bonett, 2002) which suggests the presence of moderating variables. Consequently, scholars have called for empirical studies to identify the factors that regulate the relationship between organizational commitment and job performance (e.g., Meyer, Becker, & Vandenberghe, 2004; Sungu, Weng, & Xu, 2019; Wright & Bonett, 2002). Thus, the current study is conducted to respond to the demand for studies that enhance our understanding of under what conditions organizational commitment is strongly related to employee efficiency.

According to Meyer et al. (2004), one major reason for the heterogeneous nature of the relationship between organizational commitment and job performance is the effect of contextual factors. For example, leadership can be considered an important contextual factor in the workplace that strongly influences employees’ organizational behaviours (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Leadership is the ability of an individual or group of individuals to influence and guide the team or other members of the organization and make them work in a defined direction. The concept of leadership is considered one of the highly studied but less understood topics in organizational research (Bennis, 2019). Over the past years, a variety of leadership styles has been identified and studied, which mainly includes great man theory, traits theory, situational theories, behavioural theories, process theories, transformational theories, and transactional leadership theories out of which researchers have highly emphasized the transactional and transformational leadership styles (Ahmed, Allah and Irfanullah, 2016; Kariyawasam, 2020). Transformational leadership models are considered the most interesting leadership style and frequently researched leadership model among present-day scholars (Lowe and Gardner,2000; Dinh et al. 2014). Transformational leaders influence change the followers individually and collectively; encourage innovation and creativity, facilitate learning, and create inspiring a vision for the future (Mostafa, Claudine, and Carmen, 2015). Previous research suggests that transformational leadership has a significant positive impact on many employee level outcomes such as work performance (Khan, Rehmat & Butt 2020), organizational citizenship behviour & retention (Tian atel.,2020), organizational culture & organizational vision (Gathungu, Iravo & Namusonge, 2015) and work engagement (Hayati, Charkhabi & Naami, 2014). By developing and testing a theoretical model that explains transformational leadership as a moderator of the relationship between organizational commitment and employee efficiency, we contribute to the literature in four ways.

First, employees concurrently demonstrate multiple commitments. Thus, it is theoretically important to understand their interactions in influencing employee behavior (Cohen, 2003). The current study responds to the demand for studies exploring how multiple commitments influence employee behavior (e.g., Alqudah, Carballo-Penela, & Ruzo-Sanmartín, 2022; Cohen & Freund, 2005; Kim & Mueller, 2011; Sungu, Weng & XU, 2019). We bring an argument that employees with high commitment are more likely to motivate and perform better with their belief of high-performance leads to receiving support and resources for developing their careers. Thus, the current study enriches the commitment theory by hypothesizing that the different components of organizational commitment more strongly relate to work efficiency.

Second, we argue that transformational leadership as a contextual factor is important for explaining the heterogeneous nature of the commitment–efficiency relationshiTransformational leaders behave towards identifying their followers’ needs and providing support and resources for their followers to accomplish their goals (Bass, 1985; Bass & Riggio, 2006). Employees are likely to perceive a favourable and supportive work environment when transformational leadership is high and they exhibit high job performance (e.g., Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006). Consequently, we posit that organizational commitment will be more strongly related to employee efficiency under high transformational leadership.

Third, a contextual gap in the extant literature is filled by conducting this research in a developing country. That is, many researchers have defined leadership in different ways according to the context, culture, rules, laws, complexities, psychological context, and situations (Amabile et al.,2004; Shahin & Wright, 2004; Zheng, Wu, Xie, & Li, 2019). For instance, based on a study of Egyptian Investment Banks, Shahin & Wright (2004) revealed that the transformational and transactional leadership theories which were developed in the West are to be modified when they apply in other cultures. These variations do not allow us to generalize the findings of leadership studies to a particular country context which demands country-specific leadership studies.

Finally, prior studies reveal that transformational leadership promotes the relationship between human resource practices and employee behaviour (Marwa, Namusonge and Kilika, 2019) and the relationship between employee commitment and performance (Marwa, Namusonge and Kilika, 2019). A study conducted by Jansen, George, Bosch, & Volberda, (2008) found that the executive directors’ transformational leadership moderates the relationship between the senior teams’ commitment to the shared vision and the senior team’s effectiveness (Jansen, George, Bosch, & Volberda, 2008). In contrast to these findings, some research studies (e.g., Rafia, Sudiro & Sunaryo, 2020) found that transformational leadership doesn’t have a significant impact on organizational functions such as employee performance. Therefore, further investigation of the contingent nature of transformational leadership is required to understand how it translates through different demographic groups (Bass and Riggio, 2006). One of the less investigated demographic areas in transformational leadership is the hierarchical level of leaders (Avolio and Bass, 1991; Ivey and Kline, 2010). In general, the leadership hierarchy of military organizations operates more frequently under an authoritarian style of leadership (Waddle, 1994; Turner & Lloyd-Walker, 2008; Warne, 2000). Therefore, leaders in the defense environment tend to have an autocratic leadership style who direct the progress of the followers to do the work and accomplish the mission (Waddle, 1994). However, more traditional leadership responsibilities such as maintaining order and discipline are no longer adequate for accomplishing the goals of military organizations (Scoppio, 2009). Therefore, prior studies claim that transformational leadership better supports the success of military organizations (Nissinen, Dormantaite, & Dungveckis, 2022; Robbinson, Mckenna, & Rooney; 2022).

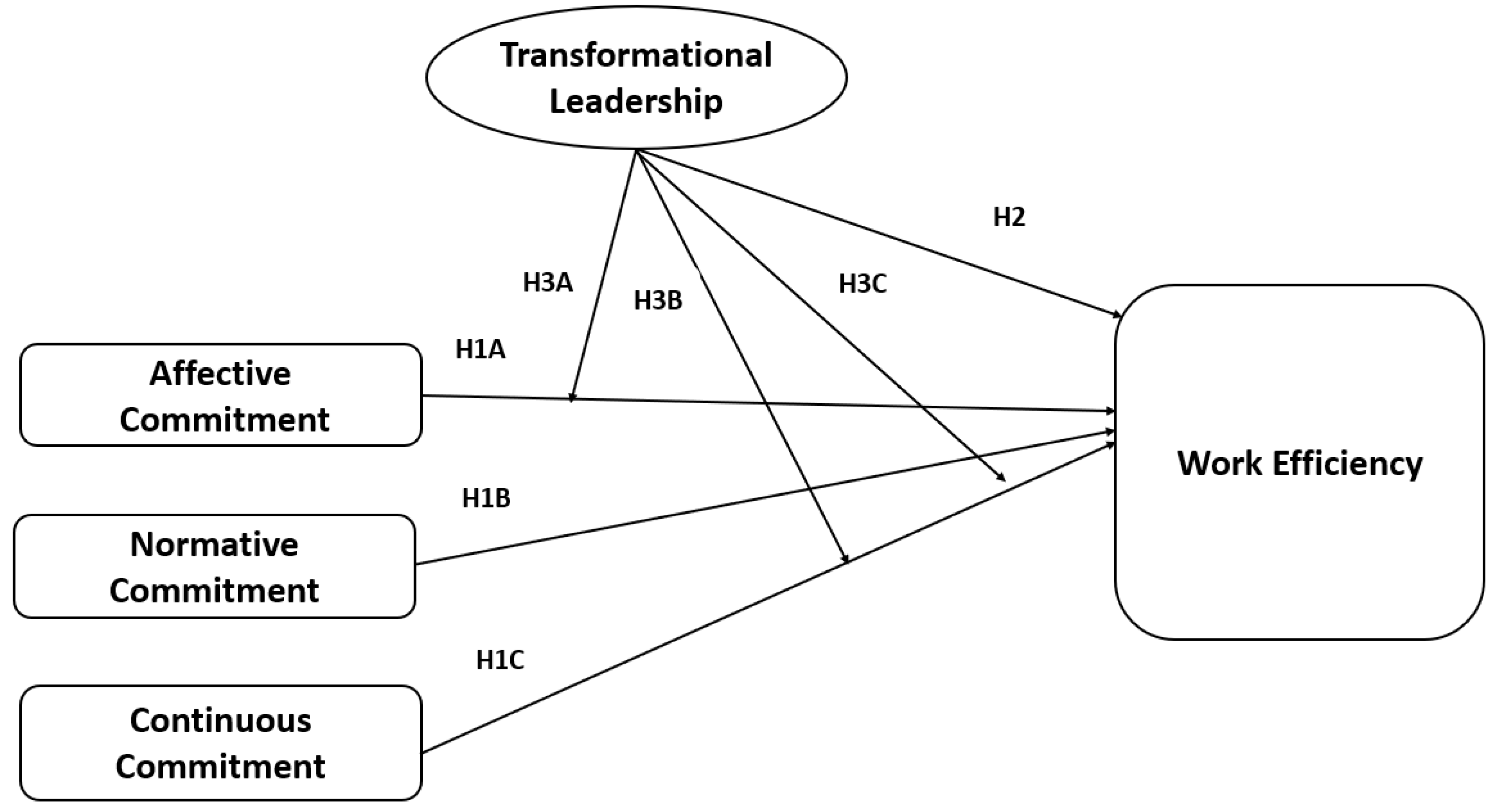

The existing studies on military leadership reveal that transformational leadership exists at all levels but, the frequency of those behaviors is different at different leader levels. (Bass et al., 2003; Bass, 1985; Kane and Tremble, 2000). Therefore, our study makes a significant contribution by responding to the demand for exploring transformational leadership to understand how it translates through different demographic groups (Bass and Riggio, 2006). Our study sample is from military leaders as one of the less investigated demographic groups (Avolio and Bass, 1991; Ivey and Kline, 2010). The existence of transformational leadership within Sri Lankan defense forces is highlighted by many studies (Bass, 1997; Jayawardana, 2020) which motivated us to conduct our study with junior sailors of the Sri Lanka Navy. In sum, by developing a model in the premise of theory (see

Figure 1), this study explains the relationship between organizational commitment and employee efficiency.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Work Efficiency

In the current competitive environment employers focus on the increase of their employees’ efficiency and productivity by supporting them to enhance their skills and competencies (Dwivedi, Chaturvedi, & Kishore Vashist, 2020; Dissanayake et al., 2022; Apostu et al., 2022; Hysa, 2014; Panait et al., 2022; Foote & Hysa, 2022). Therefore, employers force their employees to work more efficiently by saving time and shaping the way they work as per the sophisticated technology (Holland and Bardoel, 2016). Effectiveness and efficiency are considered as the key performance indicators in organizations (Moozas, 2006; Low, 2000; Iddagoda et al., 2021). There are different conceptualizations of efficiency in different contexts (Rutgers and van der Meer, 2010). For instance, efficiency is categorized as business efficiency, operational efficiency, cost efficiency and employee efficiency (Pinprayong and Siengthai, 2012). Similarly, Bartusevicienė & Sakalytė (2013) and Chavan (2009) have explained work efficiency as how optimally the input is used for the output whereas Taylor (1992) explains the efficiency as completing the task well and timely manner. Johansson & Lofgren (1996) and Rainey (1997) have identified the efficiency as the production made by minimum cost while maintaining the product quality. According to Chavan (2009) efficiency is the utilization of available resources in an optimum manner to achieve the determined objectives. Present day work efficiency is the trade-off between pay and required results and best utilization of resources (Rutgers and van der Meer, 2010). The public sector, efficiency of employees differs from the private sector due to unique characteristics such as ownership and profit orientation. Therefore, apart from technical efficiency of input output ratio, the public sector efficiency has been defined as good administration (Frederickson, Smith, 2003).

2.2. Organizational Commitment and Employee Efficiency

Organizational commitment has been defined by Mowday, Steers & Porter (1979) as the individual strength of understanding and contribution to the organization. It is also defined by Nijhof, De Jong and Beukhof (1998) as the willingness to continue with the organization whilst agreeing with and supporting organizational values. Further, level of commitment differs from person to person based on perception and loyalty and it is decided the level of engagement in goal accomplishment to the organization (Allen & Meyer, 1996). According to Wombacher and Felfe (2017), organizational commitment is a basic component in analyzing and clarifying the employee’s behaviours in their organization. Furthermore, committed employees increase job desire (Allen & Meyer, 1990; Mowday et al., 1979; Tuna et al., 2016), job satisfaction, and engagement (Toor & Ofori, 2009; Tuna et al., 2011). Committed employees are key stakeholders in achieving organizational aims and objectives (Tuna et al., 2011) and enhance the effectiveness as well as efficiency (Singh and Gupta, 2015).

A three-dimensional model has been developed by Allen and Meyer (1990) which has been utilized by many researchers for contemporary commitment-related studies (Tuna et al., 2016, Abdullah, 2011; Karim & Noor, 2006; Alam, 2014). As per Allen and Mayer (1990) the organizational commitment comprises three components including affective commitment, normative commitment, and continuance commitment. Affective commitment means employees’ emotional bond with the organization and enjoyment of living with the organization. Continuous commitment denotes the encouragement of employees to remain in the same organization due to the fear of losing the existing comfort. Normative commitment is a result of the obligation to the organization and employee interest in the job, and loyalty to the firm. It has been proven that a significant relationship exists between employee commitment and employee efficiency (Nwankwo, Orga and Abel, 2019; Walker Information Inc., 2000; Tett and Meyer, 1993; Barber et al., 1999). Moreover, Behziun, Abdolazimi and Sahranavard (2016) revealed that there are significant relationships between all three dimensions of affective commitment, normative commitment, continuance commitment, and efficiency of the employees. Linked to this argument, some scholars claim that the affective and normative components of commitment positively relate to employee efficiency whereas continuance commitment negatively relates to employee efficiency (Giedrė & Auksė, 2013; Salman, Pourmehdi, and Hamidi, 2014).

Hypothesis-1: There is a significant positive relationship between junior sailors’ (a) affective commitment, (b) normative commitment, and efficiency, whereas (c) a significant negative relationship exists between junior sailors’ continuous commitment and their efficiency.

2.3. Transformational Leadership and Employee Efficiency

As suggested by Meyer et al. (2004), contextual factors affect the relationship between organizational commitment and job performance as such leadership can be considered an important contextual factor in the workplace that strongly influences employees’ organizational behaviours (Bass & Riggio, 2006). Therefore, among many contextual factors affecting employee efficiency and productivity, effective leadership plays an integral role (Turner and Muller, 2005). Transformational leadership is a positive significant influencer of employee performance (Al-Amin, 2017; Buil, Martínez, & Matute,2019), employee efficiency (Dwivedi, Chaturvedi & Vashist, 2020, Khan et al., 2014), and enable them to deliver outstanding outcomes.

Hypothesis-2: Transformational leadership of the senior sailors has a significant positive effect on junior sailors’ work efficiency.

2.4. Moderating Effect of Transformational Leadership on Employee Commitment and Efficiency

Transformational leaders inspire, empower, and stimulate followers to go beyond their normal level of performance (Bass, 1985; Bass & Riggio, 2006; Wang & Rode, 2010; Yukl, 1999). Bass (1999) claimed that transformational leadership shifts “the follower beyond immediate self-interest through idealized influence (charisma), inspiration, intellectual stimulation, or individualized consideration” (11). Transformational leadership plays an important role in determining employee job performance (Dvir, Eden, Avolio, & Shamir, 2002) and, consequently, is regarded as an important context for examining the effect of organizational commitment on job performance (Meyer et al., 2004).

Previous studies suggest that transformational leadership enhances the relationship between HRM practices and employee behaviour. (Marwa, Namusonge & Kilika, 2019). Moreover, committed employees demonstrate higher performance when they are led by transformational leaders (Marwa, Namusonge, and Kilika, 2019). This claim is valid even for higher levels in the organizational hierarchy. For example, Jansen, George, Bosch, & Volberda, (2008) revealed that the commitment to the organization’s shared vision by the senior team positively impacts their team’s effectiveness when the executive director demonstrates transformational leadership.

Transformational leadership encourages followers to go beyond their short-term interests and focus more on best interest of the organization and their long-term professional development (Bass & Riggio, 2006; Sungu, Weng, & Xu, 2019). Consequently, employees will perceive a more enabling work environment under high transformational leadership as compared to low transformational leadership.

In the current study, we argue that transformational leadership leads highly committed employees to exhibit high job efficiency. Employees with low organizational commitment, however, have little motivation to exert effort for the good of the organization (Wright & Bonett, 2002). Therefore, high transformational leadership is less likely to influence their job performance. We, therefore, suggest that the relationship between organizational commitment and employee efficiency will be stronger under high as compared with low transformational leadership.

Hypothesis-3: Senior sailors’ transformational leadership moderates the relationship between junior sailors (A) Affective Commitment, (B) Normative Commitment, and (C) Continuance Commitment and efficiency such that the relationship is stronger when the transformational leadership is high.

4. Data Analysis and Results

The demographic data indicates that 83.44% of the sample were male respondents and only 16.56% of were female respondents. Most of the respondents, 67.48% were aged between 26 to 35 whereas 10.43% were aged between 18 to 25 years. Out of the participants, 22.09% were who were in the age range of 36 to 45 years old. In terms of the tenure of the junior sailors, only 1.23% of sample served more than 21 years while 5.52% of the sample served between 16 to 20 years in Sri Lanka Navy. Junior sailors with 11 to 15 years of service were 50.92% and only 11.66% had 1 to 5 years of service.

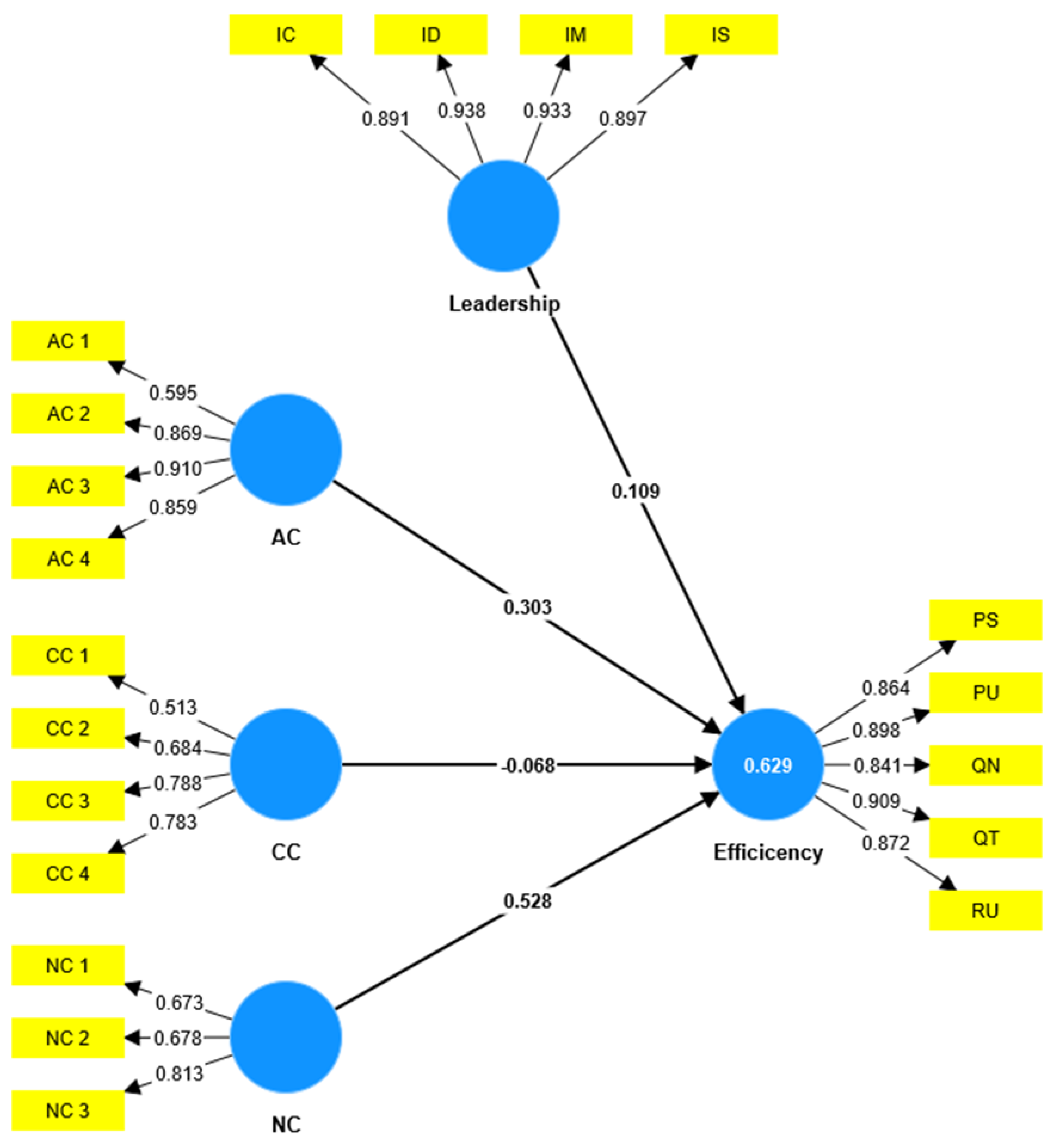

The main aim of this research is to investigate the moderating role of senior sailors’ leadership on the relationship of junior sailors’ affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment with work efficiency in the writer branch of the Sri Lanka Navy. To analyze the collected data, Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) technique along with partial Least Square (PLS) was applied using smart PLS 4.0 software. A two-step approach was used to evaluate the data set namely measurement model analysis and structural model analysis. The measurement model evaluates parameter measurement such as reliability and validity of the data set and the structural model evaluates the conceptual relationship or correlations between the parameters among the variable. If the measurement model is not reliable and valid, structural model could be inaccurate (Hair et al., 2017). This study had the second order reflective construct, and two stages approach was applied for the analysis as Lower Order Construct (LOC) and Higher Order Construct (HOC). LOC measurement model was built to evaluate the reliability and validity of the data set and due to reliability and validity issues indicators RU 2 and RU 4 were deleted from the model. Then the scores obtained from the LOC measurement model used as manifest variables for HOC model.

Figure 2 illustrates the HOC measurement model and factor loading. Model validity and reliability were tested using internal consistency reliability, individual indicator reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity.

Internal consistency of the construct is measured through composite reliability (CR). It emphasizes the degree of individual indicators representing the latent construct. If the CR is greater than 0.7 is the accepted range and if it is closer to 0.9 indicated the higher internal consistency. As per

Table 1, all the CR values are greater than 0.7 and it indicates the model is satisfying the required internal consistency reliability. On the other hand, Cronbach’s alpha value should be greater than 0.7 to satisfy the internal consistency.

Table 1 exhibits the Cronbash’s alpha of HOC model and required conditions were satisfied except NC. However, composite reliability for the NC is greater than 0.70. Therefore, a higher level of internal consistency reliability has achieved for all the dimensions of the LOC construct.

Individual indicator reliability indicates through the outer loading estimates, and it should be greater than 0.70 (Hair et al., 2011). However, Henseler et al. (2009) & Hair et al. (2017) has argued that if the individual item reliability is greater than 0.5 and other measures are in sufficient standard, indicators should not be deleted. As per

Figure 1 and

Table 2 all the factor loadings were greater than 0.50 and satisfied the individual item reliability.

Convergent validity was measured through the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and it is explained by the number of variances that indicator of reflective construct converges with each other. If the AVE is greater than 0.50, it is accepted as sufficient level of convergent validity (Hair, Ringle, et al., 2011). As per

Table 1 all AVE values are greater than 0.50 except continuance commitment. However, Allen & Meyers’ (1990) validated three-dimensional model was used by the researcher for this study and therefore the indicator was retained.

Discriminant validity is explained as the distinction of the constructs each other in the model. Discriminant validity is measured through Fornell–Larcker criterion, cross loading and HTMT of measurement model of the LOC (Hair et al.,2014). If the square root of each construct’s AVE should be greater than its correlations with any other construct, discriminant validity is satisfied (Hair et al.,2014). The Fornell-Larcker criterion of the model is represented in

Table 3 and all the values under the diagonal is lower than its diagonal values. Therefore, it can be concluded that the required rate of discriminant variability of the data has been satisfied by the model.

When an indicator’s outer loading onto its associated construct is greater than any of its cross-loading onto other constructs, the discriminant validity is established (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Table 4 shows the cross-loading of the model, and it confirmed the sufficient level of discriminant validity.

HTMT values indicate the true correlation between two perfectly reliable latent variables, when the HTMT values are greater than 0.90 is considered as lack of discriminant validity. (Henseler, Ringle, & Sarstedt, 2015). Corresponding HTMT estimations are represented in

Table 5. The HOC model satisfied the required Heterotrait - monotrait Ratio.

In a structural model, the indicators are expected to free from a highly correlated state called multicollinearity (Jarvis et al., 2003). Multicollinearity can lead to their bias estimation of weights and statistical significance (Hair et al., 2017). As per

Table 6 all the VIF values are less than 5 and therefore, Multicollinearity effect does not exist with the model (Hair et al., 2011).

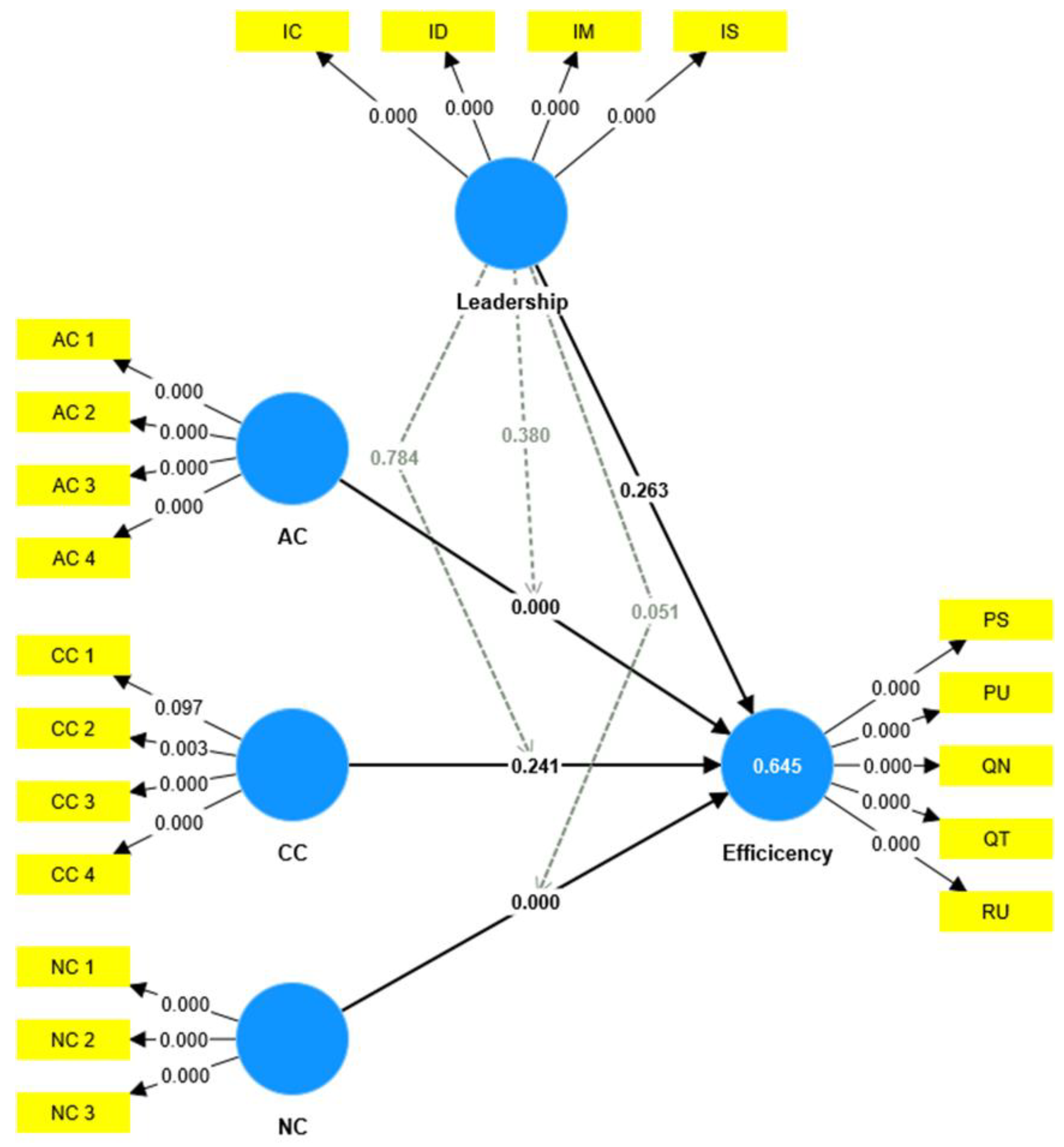

The structural model was constructed to evaluate the relationships between variables after the HOC model confirmed the reliability and validity. To evaluate the structural model, the significance and relevance of the structural model relationship and coefficient of determination were examined. As per

Table 7, R2 value of this model is 0.645 and it explained that 64.5% of the variance of work efficiency by the AC, CC, and NC of the junior sailors and transformational leadership of senior sailors in the writer branch of the Sri Lanka Navy.

This study is aimed to assess the moderation impact of the senior sailors’ transformational leadership upon the relationship between junior sailors’ affective commitment, continuance commitment and normative commitment with work efficiency in writer branch in SLN. Corresponding path coefficient results of this model is illustrated as

Figure 3 and

Table 8.

As per the

Figure 2 and

Table 8, the relationship between affective commitment and work efficiency is significant at the 0.05 of significance level and corresponding Beta value is 0.337 (B = 0.337; P = 0.000). Further, the relationship between normative commitment (NC) and work efficiency of the population is significant at the 0.05 significant level and beta value is 0.439 (B = 0.439; P = 0.000). Therefore, it is indicated that a medium level of significant positive relationships exists between both affective commitment (AC) and normative commitment (CC) with the work efficiency. However, the relationship between continuance commitment (CC) and work efficiency is not significant under the 0.05 significant level (B = -0.072; P = 0.241). On the other hand, it is found that there is no significant impact of the senior sailors’ transformational leadership on the junior sailors’ work efficiency (B = 0.096; P = 0.263).

The moderation impact of senior sailors’ transformational leadership on the relationship between junior sailors’ affective commitment, continuance commitment and normative commitment with work efficiency was evaluated. However, it is found that the moderation impact of senior sailors’ transformational leadership on the relationship between affective commitment, continuance commitment and normative commitment with junior sailor’s work efficiency were not significant under 5% of significance level for all the three relationships. Therefore, it can be concluded that there is no significant moderating impact of senior sailors’ transformational leadership on the relationship between junior sailors’ affective commitment, continuance commitment and normative commitment with junior sailors’ work efficiency.

5. Discussion

Previous studies suggest that the three components of commitment (Allen & Mayer, 1990) have significant positive relationships with employee efficiency (Behziun et al., 2016; Giedrė & Auksė, 2013; Nwankwo, Orga and Abel, 2019; Salman et al., 2014; Walker Information Inc., 2000; Tett and Meyer, 1993; Barber et al., 1999). However, the current research supports these findings only for affective and normative commitment. Therefore, the study did not report a significant relationship between continuance commitment and employee efficiency. This outcome is contrary to the previous study findings which state that the continuance commitment improves the organizational effectiveness of the employees (Salman, Pourmehdi, and Hamidi, 2014; Giedrė & Auksė 2013; Mowday et al.,1982; Mthieu and Zajac, 1990). Contrary to previous studies (Dwivedi, Chaturvedi & Vashist, 2020, Khan et al., 2014) the current study does not report a significant relationship between transformational leadership and employee efficiency. This outcome may be because the leadership hierarchy of military organizations operates more frequently under an authoritarian style of leadership (Waddle, 1994; Turner & Lloyd-Walker, 2008; Warne, 2000).

A positive significant moderation effect of transformational leadership on the relationship between organizational culture and employee effectiveness was found in a study conducted by Ayeman and Mohi-Adden (2019). The research conducted by Bellibaş et al. (2021) suggests that transformational leadership plays a significant moderating effect on the association between human capital and organizational innovations. Therefore, many of the organizational functions are energized by the leaders’ transformational style. In contrast to prior studies, this research found that transformational leadership is not a factor that enhances the relationships of affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment with work efficiency.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The findings of the study contribute to the literature in three ways. First, as supported by the study, the affective and normative components of commitment positively influence employee efficiency. These outcomes enrich Allen and Mayer’s (1990) three-component model of commitment and advance our understanding of the interactions of different commitment components with employee efficiency. Second, the absence of a moderating effect of transformational leadership between employee commitment and efficiency supports the claim that transformational leadership is a contextual factor. Therefore, transformational leadership is dependent on the culture, rules, laws, complexities, psychological context, and situations (Amabile et al.,2004; Shahin & Wright, 2004; Zheng, Wu, Xie, & Li, 2019). Finally, the study validated Bass and Avolio’s (1990) transformational leadership questionnaire, Allen, and Meyer’s (1990) questionnaire of the three-dimensional model of organizational commitment, and the efficiency questionnaire developed by Sori (2013) in a non-western context.

5.2. Practical Implications

Our findings could benefit the practice in two ways. First, the weak relationships between affective commitment, normative commitment, and employee efficiency suggest that the Sri Lanka Navy should take measures to build the commitment of junior sailors. Highly committed employees are less likely to leave their employer and more likely to demonstrate higher performance (Tett & Meyer, 1993). Sri Lanka Navy could implement various types of practices such as providing support, rewarding employees fairly, and creating procedural justice to enhance the junior sailors’ affective attachment. In terms of support, caring about the employee’s well-being and treating them fairly, considering the employee’s goals and values, helping when employees need a favor or have a problem and forgiving mistakes are some of the practices that can be proposed. Procedural justice can be assured by communicating decisions transparently, getting employee involvement in making important decisions, and listening to the employee’s voices. Sri Lanka Navy should revisit the existing reward system and should implement programs to recognize junior sailors’ contributions with financial and non-financial rewards. They should also provide opportunities for advancement. Senior sailors should show their concern for the junior sailors and their wellbeing. Finally, the absence of a significant effect of transformational leadership on junior sailors, efficiency may be because of the dominance of authoritative leadership in the Sri Lanka Navy. Therefore, leadership training programs should be offered to senior sailors for developing their leadership skills. The current study would also benefit non-military organizations by signaling the significance of enhancing employee affective and normative commitment to boost employee work efficiency. Therefore, previously mentioned commitment enhancing practices should be implemented toward the employees.