Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

21 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

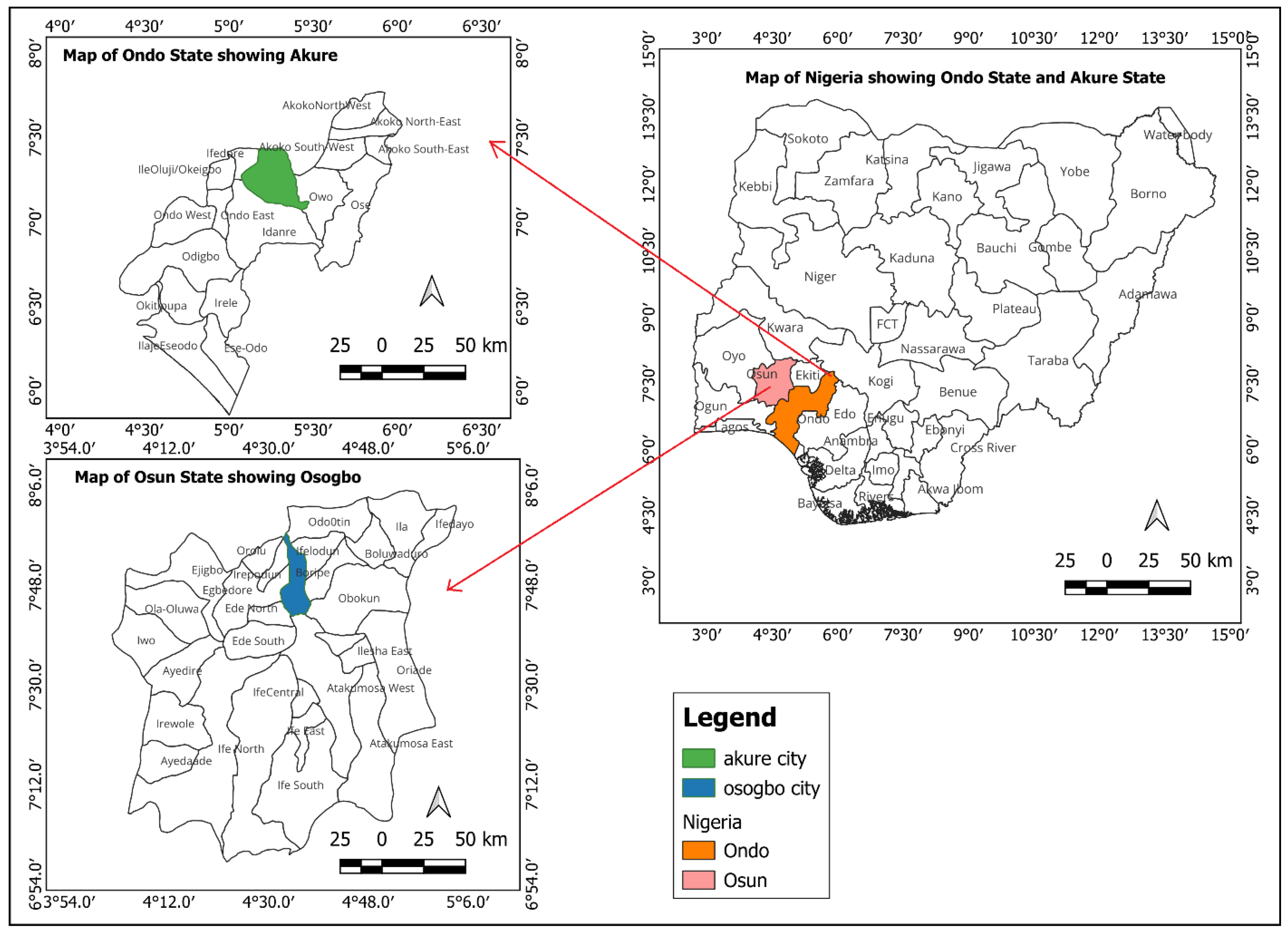

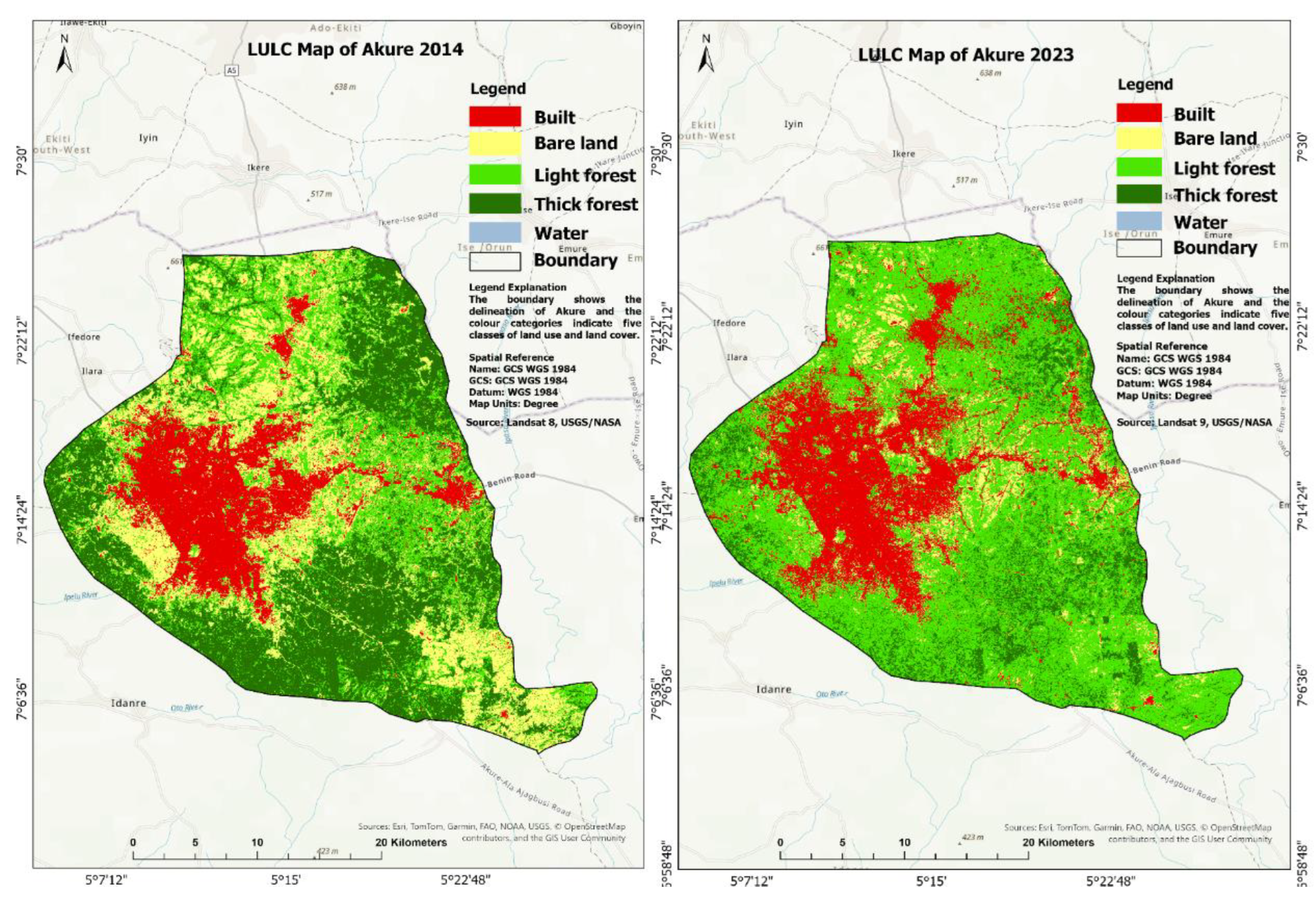

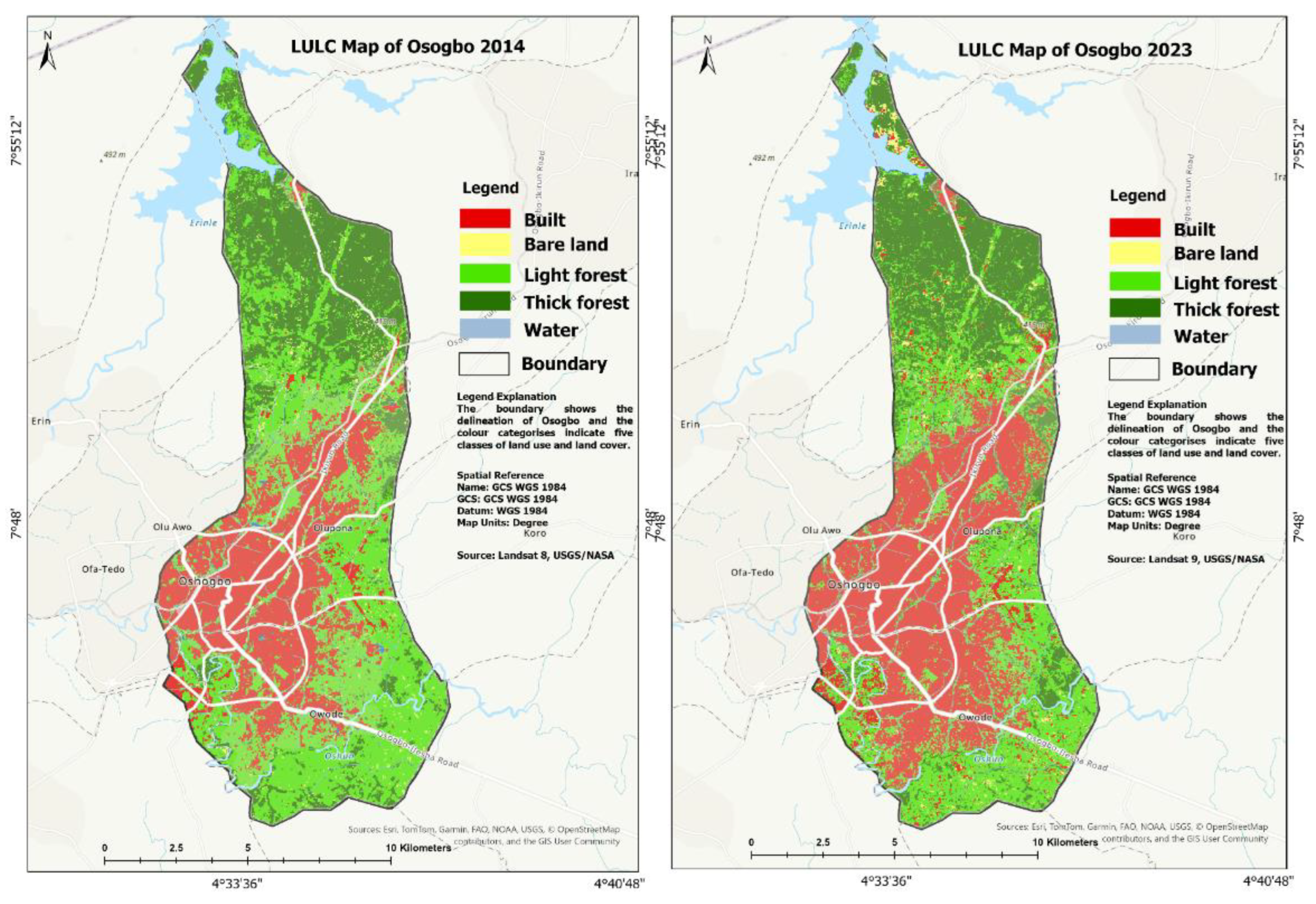

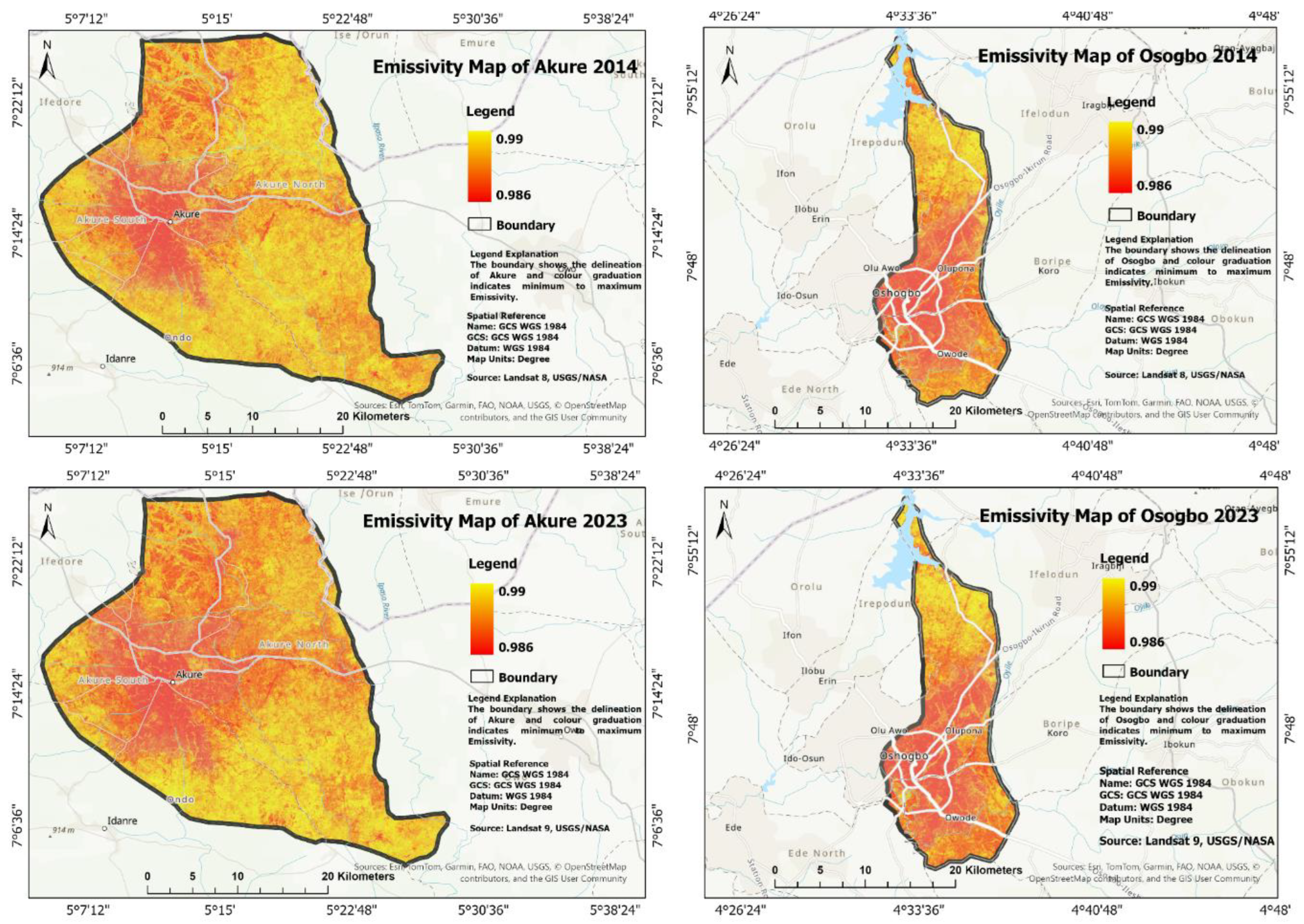

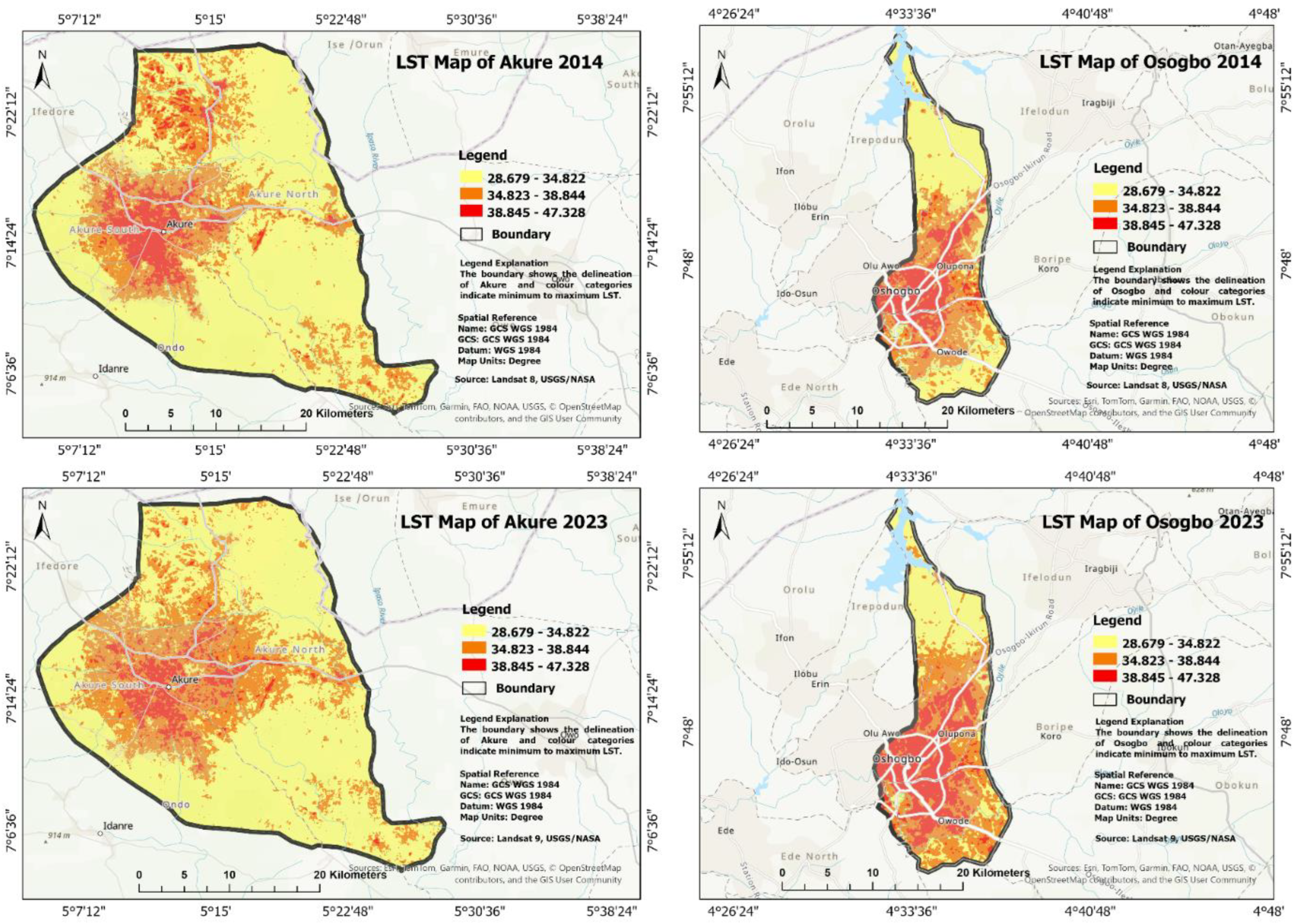

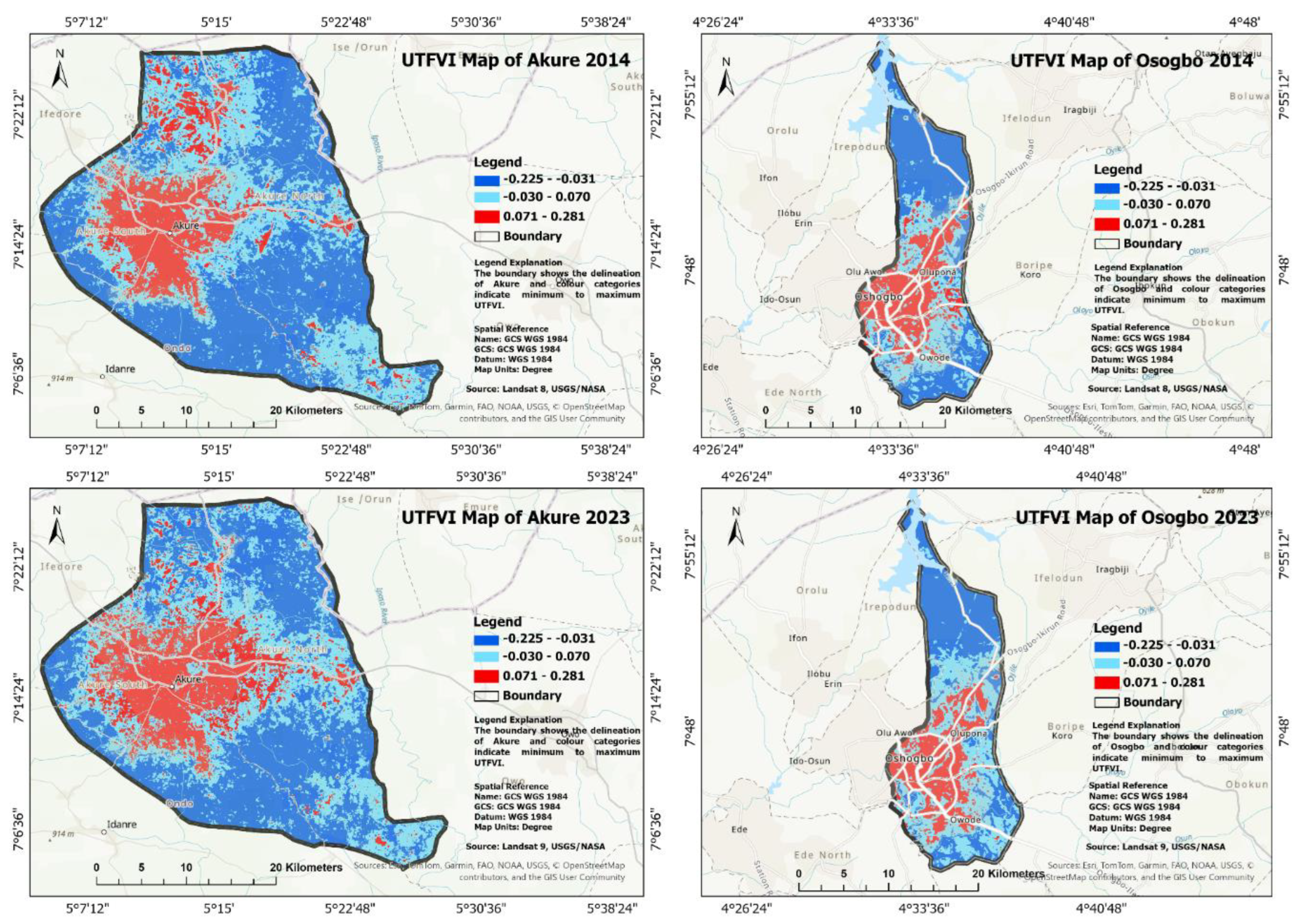

Rapid urbanization and climate impacts have raised concerns about the emergence and aggravation of urban heat island effects. In Africa, studies have focused more on big cities due to their growing populations and high socio-economic functions, while mid-sized cities remain understudied, with limited comparative insights into their distinct characteristics. This study therefore provided a spatiotemporal analysis of land use land cover change (LULCC) and surface urban heat islands (SUHI) effects in the Nigerian mid-sized cities of Akure and Osogbo from 2014 to 2023. This study used Landsat 8 and 9 imagery (2014 and 2023) and analyzed data via Google Earth Engine and ArcGIS Pro 3.4. Results showed that Akure increased significantly from 164.026 km² to 224.191 km² in the built areas while Osogbo witnessed a smaller expansion from 41.808 km² to 58.315 km² in built areas. This study identified Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and emissivity patterns associated with vegetation and thermal emissions and a positive association between LST and urbanization. The findings across Akure and Osogbo cities established that the LULCC had a different impact on SUHI effects. As a result, evidence from a mid-sized city might not be extended to other cities of similar size and socioeconomic characteristics without caution.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

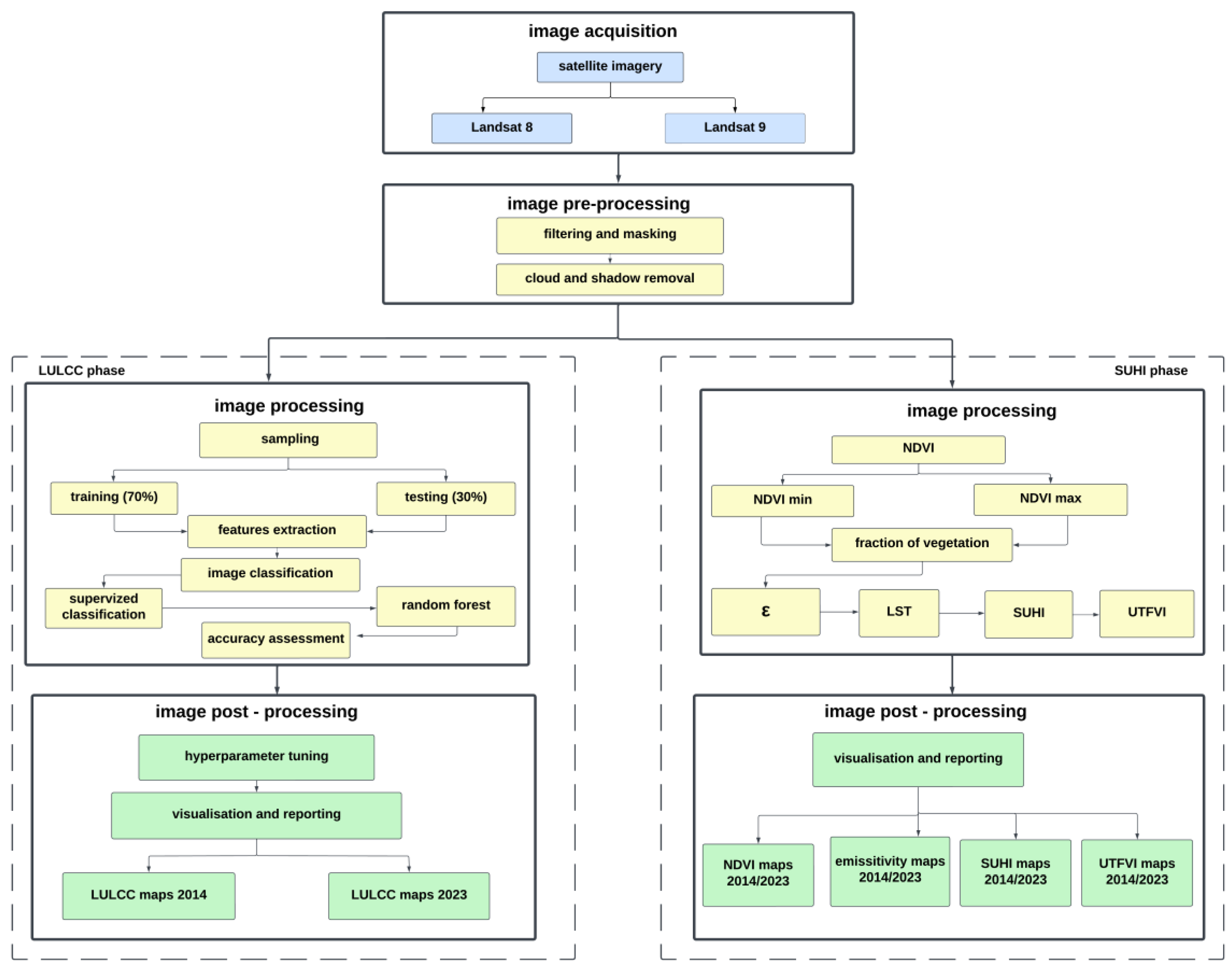

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Acquisition

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Image Classification

2.3.2. Random Forest

2.3.3. Quantitative Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Land Use Land Cover Change in Akure and Osogbo Between 2014 and 2023

3.2. Surface Urban Heat Island Effects in Akure and Osogbo Between 2014 and 2023

3.3. Relationship Between LULC Change and SUHI Effects in Akure and Osogbo Between 2014 and 2023

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brenner, N.; Keil, R. From global cities to globalized urbanization. In The city reader; Routledge, 2011; pp. 667–684. [Google Scholar]

- Kundu, D.; Pandey, A. K. World urbanization: trends and patterns. Developing national urban policies: Ways forward to green and smart cities 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations; Department of Economic and Social Affairs; Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. 2022. Retrieved from. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdf.

- Popoola, O.; Durojaye, P.; Bayode, T.; Popoola, A.; Olanibi, J.; Aladetuyi, O. Spatio-temporal variance and urban heat island in Akure, Nigeria: A time-spaced analysis Using GIS Techniqu. South African Journal of Geomatics 2020, 9(2), 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linard, C.; Tatem, A. J.; Gilbert, M. Modelling spatial patterns of urban growth in Africa. Applied Geography 2013, 44, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterji, T. New urban worlds: inhabiting dissonant times. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Urban population (% of total population)–Nigeria Data World. 2018. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS?locations=NG.

- Sun, Y.; Jiao, L.; Guo, Y.; Xu, Z. Recognizing urban shrinkage and growth patterns from a global perspective. Applied Geography 2024, 166, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewale, A. O.; Adepoju, K. A.; Awotoye, O. O. Mapping and assessing impervious surface areas and urban heat island in Osogbo, Nigeria. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Icaza, L. E.; Neht, A.; Klavins, M.; Morgan, E. A. Coping with the impacts of urban heat islands. A literature based study on understanding urban heat vulnerability and the need for resilience in cities in a global climate change context. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 171, 1140–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuholske, C. Exposure to deadly urban heat worldwide has tripled in recent decades. State of the Planet, Earth Institute, Columbia University. 2021. Available online: https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2021/10/04/exposure-to-deadly-urban-heat-worldwide-has-tripled-in-recent-decades/.

- Ma, X.; Dong, L. Surface urban heat island effect and its spatiotemporal dynamics in metropolitan areas: A case study in the Zhengzhou metropolitan area, China. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2023. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2023.00001/full. [CrossRef]

- Badmos, O. S.; Callo-Concha, D.; Agbola, B.; Rienow, A.; Badmos, B.; Greve, K.; Jürgens, C. Determinants of residential location choices by slum dwellers in Lagos megacity. Cities 2020, 98, 102589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. K.; Verma, P.; Shankar Singh, G. Agricultural growth and land use land cover change in peri-urban India. Environmental monitoring and assessment 2019, 191, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Singh, R.; Singh, P.; Raghubanshi, A. S. Urban ecology–current state of research and concepts. In Urban ecology; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Angadi, D. P. Land use-land cover (LULC) transformation and its relation with land surface temperature changes: A case study of Barrackpore Subdivision, West Bengal, India. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 2020, 19, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demisse Negesse, M.; Hishe, S.; Getahun, K. LULC dynamics and the effects of urban green spaces in cooling and mitigating micro-climate change and urban heat island effects: a case study in Addis Ababa city, Ethiopia. Journal of Water and Climate Change 2024, 15(7), 3033–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguda, A. S.; Adegboyega, S. A. Evaluation of spatio-temporal dynamics of urban sprawl in Osogbo, Nigeria using satellite imagery & GIS techniques. International Journal of Multidisciplinary and Current Research 2013, 1(1), 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B.; Tebaldi, C.; O’Neill, B. C.; Oleson, K.; Gao, J. Avoiding population exposure to heat-related extremes: demographic change vs climate change. Climatic change 2018, 146, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eresanya, E. O.; Daramola, M. T.; Durowoju, O. S.; Awoyele, P. Investigation of the changing patterns of the land use land cover over Osogbo and its environs. Royal Society Open Science 2019, 6(12), 191021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, G. T.; Berlie, A. B.; Wubie, M. A.; Legesse, S. A. Drivers of surface urban heat island of Gondar City, Ethiopia: a comparative study. Cogent Social Sciences 2024, 10(1), 2354974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Kim, G. A comprehensive review of different types of green infrastructure to mitigate urban heat islands: Progress, functions, and benefits. Land 2022, 11(10), 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorio, M.; Paparella, R. Climate Mitigation Strategies: The Use of Cool Pavements. Sustainability 2023, 15(9), 7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardhu, V. A. K.; Sharma, A. Classification, Mitigations and Methods to Detect UHI: A Review. International Journal of Scientific Research in Engineering and Management (IJSREM) 2023, 7(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, B.; Guldmann, J. M. Spatial statistical analysis and simulation of the urban heat island in high-density central cities. Landscape and Urban Planning 125 2014, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbling, M.; Meierrieks, D. Global warming and urbanization. Journal of population economics 2023, 36(3), 1187–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, D.; Morimoto, T.; Murayama, Y.; Ranagalage, M. The impact of landscape composition for urban heat island intensity in Addis Ababa City using Landsat data (1986–2016). Abstracts of the Ica 2019, 1, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degefu, M. A.; Argaw, M.; Feyisa, G. L.; Degefa, S. Dynamics of green spaces-land surface temperature intensity nexus in cities of Ethiopia. Heliyon 2023, 9(2), e13274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owoeye, J. O.; Ibitoye, O. A. Analysis of Akure urban land use change detection from remote imagery perspective. Urban Studies Research 2016, 2016(1), 4673019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfeey, A. M. M.; Chau, H. W.; Sumaiya, M. M. F.; Wai, C. Y.; Muttil, N.; Jamei, E. Sustainable mitigation strategies for urban heat island effects in urban areas. Sustainability 2023, 15(14), 10767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makvandi, M.; Li, W.; Ou, X.; Chai, H.; Khodabakhshi, Z.; Fu, J.; Horimbere, E. D. L. J. Urban heat mitigation towards climate change adaptation: An eco-sustainable design strategy to improve environmental performance under rapid urbanization. Atmosphere 2023, 14(4), 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasomsup, W. Spatial evalution and prediction of urban heat island pkenomena in bangkok and its vicinity. Doctoral dissertation, School of Remote Sensing Institute of Science Suranaree University of Technology, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eludoyin, A. O.; Omotoso, I.; Eludoyin, O. M.; Popoola, K. S. Remote sensing technology for evaluation of variations in land surface temperature, and case study analysis from Southwest Nigeria. Geospatial challenges in the 21st century 2019, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simwanda, M.; Ranagalage, M.; Estoque, R. C.; Murayama, Y. Spatial analysis of surface urban heat islands in four rapidly growing African cities. Remote Sensing 2019, 11(14), 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athukorala, D.; Murayama, Y. Urban heat island formation in Greater Cairo: Spatio-temporal analysis of daytime and nighttime land surface temperatures along the urban–rural gradient. Remote Sensing 2021, 13(7), 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotir, C.; Amponsah, O.; Anbazu, J.; Takyi, S. A.; Blija, D. K.; Frempong, F. Unveiling Ghana's urban tapestry: satellite-based analysis of Tamale city's spatial expansion and land surface temperature (LST) dynamics. GeoJournal 2024, 89(6), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makinde, E. O.; Agbor, C. F. Geoinformatic assessment of urban heat island and land use/cover processes: a case study from Akure. Environmental Earth Sciences 2019, 78, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofordu, C. S.; Agbor, C. F.; Aigbokhan, O. J.; Audu, M. A.; Adedoyin, E. D.; Ogoliegbune, O. M. Urban Heat Island and Land Use/Cover Dynamics Evaluation in Enugu Urban, Nigeria. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection 2022, 10(12), 354–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odunsi, O. M.; Rienow, A. Estimating Surface Urban Heat Island Effects of Abeokuta Within the Context of Its Economic Development Cluster in Ogun State Nigeria: A Baseline Study Utilising Remote Sensing and Cloud-Based Computing Technologies. Climate 2024, 12(12), 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Population Commission of Nigeria. National Bureau of Statistics - City population. 2023. Available online: https://citypopulation.de/en/nigeria/admin/ondo/NGA029005__akure_north/.

- Fasakin, J.; Basorun, J.; Bello, M.; Enisan, O.; Ojo, B.; Popoola, O. Effect of Land Pricing on Residential Density Patter in Akure Nigeria. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal 2018, 5(1), 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduwaye, L.; Akinbile, C.; Oluwatobi, A. A GIS-based assessment of urban expansion and its environmental consequences in Akure, Nigeria. In Journal of Environmental Planning and Management; Office, Vienna, 2020; Volume 63, 8, pp. 1407–1425. [Google Scholar]

- Adejuwon, J. O.; Adekitan, A. A.; Oladunmoye, S. L. Community awareness and evaluation of surface water bodies in Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management 2018, 22(10), 1567–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladehinde, G.; Fatusin, A. F.; Ojo, V. Urban expansion and loss of agricultural land in Osogbo, Osun State Nigeria, using multi-temporal imageries. Journal of African Real Estate Research 2019, 4(1), 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayiwola, A. M.; Olaitan, A. A. Spatial preference of urban residential location in Osogbo, Nigeria. Ghana Journal of Geography 2019, 11(1), 140–158. [Google Scholar]

- Aluko, O. W.; Okhimamhe, A.; Abubaker, S. Towards Transforming Osogbo into a Sustainable City, The Remote Sensing Perspective. AIJR Preprints 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, S. A.; Andongma, T. W.; Ogungbade, O.; Senbore, S. S.; Alepa, V. C.; Akinlabi, O. J.; Muhammed, Q. O. Flood vulnerable zones mapping using geospatial techniques: Case study of Osogbo Metropolis, Nigeria. The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science 2022, 25(3), 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote sensing of Environment 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badmos, O. S.; Rienow, A.; Callo-Concha, D.; Greve, K.; Jürgens, C. Urban development in West Africa—Monitoring and intensity analysis of slum growth in Lagos: Linking pattern and process. Remote Sensing 2018, 10(7), 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badmos, O. S.; Rienow, A.; Callo-Concha, D.; Greve, K.; Jürgens, C. Simulating slum growth in Lagos: An integration of rule based and empirical based model. Computers, environment and urban systems 2019, 77, 101369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine learning 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, F.; Di Napoli, A. Reliability assessment of a measure: the kappa statistic. Giornale di Tecniche Nefrologiche e Dialitiche 2016, 28(4), 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Tang, L.; Hupy, J.P.; Wang, Y.; Shao, G.F. A commentary review on the use of normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) in the era of popular remote sensing. J. For. Res. Erratum in J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 1–6, Erratum in J. For. Res. 2021, 32, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarian, M.; Doyle, T. E.; Samavi, R. MLCM: Multi-label confusion matrix. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 19083–19095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J.M.; Becker, F. Terminology in thermal infrared remote sensing of natural surfaces. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1995, 77, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. L.; Tang, B. H.; Wu, H.; Ren, H.; Yan, G.; Wan, Z.; Sobrino, J. A. Satellite-derived land surface temperature: Current status and perspectives. Remote sensing of environment 2013, 131, 14–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waleed, M.; Sajjad, M.; Acheampong, A. O.; Alam, M. T. Towards sustainable and livable cities: leveraging remote sensing, machine learning, and geo-information modelling to explore and predict thermal field variance in response to urban growth. Sustainability 2023, 15(2), 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisa, M. B.; Gemeda, D. O. Assessment of urban thermal field variance index and thermal comfort level of Addis Ababa metropolitan city, Ethiopia. Heliyon 2022, 8(8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bytyqi, V.; Qevani, S.; Agaj, T. Quantifying and Visualizing Land Cover. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ghazaryan, G.; Rienow, A.; Oldenburg, C.; Thonfeld, F.; Trampnau, B.; Sticksel, S.; Jürgens, C. Monitoring of urban sprawl and densification processes in western Germany in the light of SDG indicator 11.3. 1 based on an automated retrospective classification approach. Remote Sensing 2021, 13(9), 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuba, N. Research note: Sankey diagrams for visualizing land cover dynamics. Landscape and Urban Planning 2015, 139, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balogun, I. A.; Adeyewa, D. Z.; Balogun, A. A.; Morakinyo, T. E. Analysis of urban expansion and land use changes in Akure, Nigeria, using remote sensing and geographic information system (GIS) techniques. Journal of Geography and Regional Planning 2011, 4(9), 533. [Google Scholar]

- Ekemode, B. G. Impact of urban regeneration on commercial property values in Osogbo, Osun State, Nigeria. Smart and Sustainable Built Environment 2020, 9(4), 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A. I.; Kehinde, O. J.; Adedayo, O. O.; Aderinola, O. F. Appraising the Performance of Urban Renewal Measures in Nigeria: A Case of Osogbo, Osun State. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoade, A. O.; Onifade, V. A.; Jimoh, H. O. Residents’ satisfaction with urban renewal projects in south-western Nigeria. Journal of Urban Regeneration & Renewal 2022, 16(2), 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ojo, O. O.; Shittu, A. A.; Adebolu, T. J. Landuse Pattern and Landcover of Akure Forest Reserve and Its Environs. International Journal of Environment and Climate Change 2019, 9(12), 852–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochei, M. C.; Ogunfuyi, S. O. Impact of Urbanization on Temperature Trend Using Geospatial Techniques Sciences, 6(3), 208-223.in Ondo State, Nigeria. Remote Sensing in Earth Systems 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, S.; Pasra, M. M. Analysis of correlation between urban heat islands (SUHI) with land-use using sentinel 2 time-series image in Makassar city. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing, 2020; Vol. 419, No. 1, p. 012088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriota, E. G. Analysis of patterns, drivers, and trends of Surface Urban Heat Islands (SSUHIS) in Brazil. 2024. Available online: https://repositorio.ufpb.br/jspui/handle/123456789/32140.

- Singh, R.; Kalota, D. Urban sprawl and its impact on generation of urban heat island: A case study of Ludhiana city. Journal of the Indian society of remote sensing 2019, 47(9), 1567–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafy, A. A.; Rahman, M. S.; Hasan, M. M.; Islam, M. Modelling future land use land cover changes and their impacts on land surface temperatures in Rajshahi, Bangladesh. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 2020, 18, 100314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M. S.; Ahmad, S. R.; Javed, M. A. Impact assessment of urban development patterns on land surface temperature by using remote sensing techniques: a case study of Lahore, Faisalabad and Multan district. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27(32), 39865–39878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seun, A. I.; Ayodele, A. P.; Koji, D.; Akande, S. O. The potential impact of increased urbanization on land surface temperature over South-West Nigeria. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability 2022, 4, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Peng, S. Research on the spatiotemporal coupling relationships between land use/land cover compositions or patterns and the surface urban heat island effect. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022, 29(26), 39723–39742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Band | Wavelength (micrometers) | Resolution (meters) |

| Band1 - Coastal aerosol | 0.43 – 0.45 | 30 |

| Band2 – Blue | 0.45 – 0.51 | 30 |

| Band3 – Green | 0.53 – 0.59 | 30 |

| Band4 – Red | 0.64 – 0.67 | 30 |

| Band5 – Near Infrared (NIR) | 0.85 – 0.88 | 30 |

| Band6 – SWIR 1 | 1.57 – 1.65 | 30 |

| Band7 – SWIR 2 | 2.11 – 2.29 | 30 |

| Band8 – Panchromatic | 0.50 – 0.68 | 15 |

| Band9 – Cirrus | 1.36 – 1.38 | 30 |

| Band10 – Thermal Infrared (TIRS) 1 | 10.6 – 11.19 | 100 |

| Band 11 - Thermal Infrared (TIRS) 2 | 11.50 – 12.51 | 100 |

| Sample | Assessment | Akure 2014 | Akure 2023 | Osogbo 2014 | Osogbo 2023 |

| Training | Overall Accuracy (OvA) | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.993 | 0.996 |

| Kappa Coefficient (K) | 0.998 | 0.996 | 0.991 | 0.995 | |

| Testing | Overall Accuracy (OvA) | 0.812 | 0.800 | 0.834 | 0.816 |

| Kappa Coefficient (K) | 0.746 | 0.705 | 0.791 | 0.738 | |

| Number of trees for hyperparameter tuning | 80 | 90 | 90 | 50 | |

| Study Area | Class | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Median | 90th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akure 2014 | Built | -0.115 | 0.281 | 0.114 | 0.056 | 0.114 | 0.189 |

| Bare land | -0.219 | 0.279 | 0.023 | 0.055 | 0.020 | 0.091 | |

| Light forest | -0.226 | 0.223 | -0.026 | 0.046 | -0.029 | 0.035 | |

| Thick forest | -0.220 | 0.220 | -0.072 | 0.036 | -0.076 | -0.028 | |

| Water | -0.098 | 0.155 | 0.013 | 0.046 | 0.008 | 0.072 | |

| Akure 2023 | Built | -0.435 | 0.267 | 0.083 | 0.065 | 0.093 | 0.157 |

| Bare land | -0.250 | 0.233 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.056 | 0.115 | |

| Light forest | -0.479 | 0.227 | -0.035 | 0.064 | -0.038 | 0.051 | |

| Thick forest | -0.442 | 0.229 | -0.084 | 0.048 | -0.084 | -0.027 | |

| Water | -0.098 | 0.126 | 0.009 | 0.046 | 0.012 | 0.069 | |

| Osogbo 2014 | Built | -0.094 | 0.235 | 0.106 | 0.045 | 0.106 | 0.166 |

| Bare land | -0.200 | 0.163 | -0.029 | 0.072 | 0.026 | 0.065 | |

| Light forest | -0.211 | 0.199 | -0.016 | 0.062 | -0.016 | 0.066 | |

| Thick forest | -0.237 | 0.151 | -0.127 | 0.048 | -0.135 | -0.063 | |

| Water | -0.234 | 0.179 | -0.115 | 0.073 | -0.143 | 0.005 | |

| Osogbo 2023 | Built | -0.155 | 0.221 | 0.075 | 0.047 | 0.080 | 0.130 |

| Bare land | -0.154 | 0.117 | -0.017 | 0.048 | -0.013 | 0.046 | |

| Light forest | -0.214 | 0.149 | -0.021 | 0.054 | -0.015 | 0.046 | |

| Thick forest | -0.244 | 0.135 | -0.116 | 0.052 | -0.125 | -0.043 | |

| Water | -0.286 | 0.083 | -0.163 | 0.045 | -0.156 | -0.117 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).