1. Introduction

The transition from chaos to order is a foundational problem that has puzzled scientists across disciplines, from physics and biology to economics and social sciences. Classical deterministic approaches, rooted in Newtonian mechanics, often assume that order must be imposed externally or preordained by initial conditions. However, observations of natural systems—from planetary motion to cellular organization and financial markets—suggest that order can spontaneously emerge from randomness. This raises a crucial question: how does order arise from chaos?

The concept of randomness has evolved throughout the history of science. Early deterministic views, as exemplified by Laplace’s notion of a perfectly predictable universe, dominated classical physics. However, the development of statistical mechanics in the 19th century introduced probability as a fundamental tool for describing macroscopic behavior. The 20th century saw further paradigm shifts with the advent of quantum mechanics, where uncertainty and stochastic behavior are intrinsic to physical laws. Simultaneously, chaos theory revealed that deterministic systems can exhibit unpredictable, highly sensitive behavior, further blurring the line between order and disorder.

Despite these advances, a unifying explanation for how structured patterns emerge from disordered systems remained elusive. The advent of stochastic processes provided a new perspective, illustrating how randomness can drive self-organization. This paper posits that stochasticity is not merely a source of noise but an essential mechanism for generating stable, macroscopic order( [

6]). By examining stochastic differential equations, entropy-driven processes, and nonlinear feedback mechanisms, we aim to uncover the universal principles governing emergent complexity across diverse systems.

This study employs a multidisciplinary approach, integrating mathematical modeling, empirical observations, and computational simulations. We explore how stochastic dynamics underpin natural organization, bridging quantum phenomena, evolutionary adaptation, and social structures. By recognizing stochasticity as a driving force rather than an impediment, this research offers a novel framework for understanding the intricate balance between chaos and order.

Building upon this foundation, our study aims to explore the underlying mechanisms that govern the emergence of order from chaos through a stochastic perspective. Traditional reductionist methods often struggle to fully capture the complexity of dynamic systems, as they tend to isolate variables rather than embrace the interconnected and often unpredictable nature of interactions within a system. By contrast, a stochastic framework enables us to analyze the probabilistic interactions that drive system evolution, revealing hidden patterns and self-organizing principles that deterministic approaches may overlook.

One of the central hypotheses of this research is that stochasticity acts as a fundamental organizing principle rather than a mere source of randomness. This claim is supported by evidence across multiple scientific domains. In thermodynamics, stochastic fluctuations at the microscopic level give rise to stable macroscopic properties, as described by statistical mechanics. In biology, random genetic mutations drive evolutionary adaptation, leading to structured complexity over time. Similarly, in social and economic systems, individual decision-making processes—often influenced by uncertainty—aggregate into stable market trends and societal structures. These examples underscore the role of stochasticity in fostering emergent organization across disciplines.

To systematically investigate this phenomenon, we employ a combination of mathematical modeling, computational simulations, and empirical analysis. Our methodology incorporates stochastic differential equations, entropy-based models, and agent-based simulations to quantify how randomness contributes to the development of structured behavior. By examining case studies ranging from quantum fluctuations to large-scale ecological patterns, we seek to establish a unifying framework for understanding self-organization in complex systems.

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 introduces the theoretical background of stochastic processes and their significance in physical, biological, and social systems.

Section 3 presents mathematical and computational models that describe self-organization through stochasticity, including stochastic differential equations and numerical simulations.

Section 4 explores empirical evidence from various disciplines, demonstrating the role of randomness in emergent order.

Section 5 discusses practical applications, such as machine learning, financial modeling, and climate science, highlighting the relevance of stochastic neural networks.

Section 6 synthesizes these findings, discussing broader implications and future research directions. Finally, Section 7 provides conclusions, emphasizing the importance of stochastic principles in understanding and modeling complex systems.

2. Stochasticity and Stochastic Determinism

Stochasticity, or randomness, is a fundamental property of many natural systems, spanning across physics, biology, and social sciences. Unlike deterministic systems, where outcomes are entirely defined by initial conditions and governing equations, stochastic systems incorporate randomness as an intrinsic element of their evolution. This randomness can arise from external perturbations, inherent quantum uncertainty, or the aggregate behavior of many interacting components.

Mathematically, stochasticity is commonly modeled using probability theory and stochastic differential equations (SDEs). A general form of an SDE is given by:

where

is the state variable,

represents deterministic forces,

denotes the stochastic influence, and

is a Wiener process representing Brownian motion. These equations are essential for describing systems with uncertainty, such as financial markets, thermodynamic fluctuations, and evolutionary dynamics.

The interplay between stochastic and deterministic forces leads to the concept of

stochastic determinism, an emerging theoretical framework suggesting that stochasticity does not necessarily equate to disorder but can, paradoxically, facilitate structured behavior( [

1]). This perspective argues that randomness, under specific conditions, can drive the emergence of predictable macroscopic patterns. A notable example is statistical mechanics, where random molecular motions give rise to well-defined thermodynamic laws at a macroscopic scale.

Stochastic determinism finds applications in diverse fields. In physics, quantum mechanics embraces probabilistic interpretations to describe particle behavior, reconciling wave-function collapse with statistical predictions. In biology, genetic drift and mutation introduce variability, yet evolutionary processes channel this randomness into adaptive complexity. Similarly, in social sciences, individual choices appear random at the micro-level but aggregate into stable economic and social structures.

Thus, stochastic determinism provides a unifying lens through which the emergence of order from randomness can be understood. By exploring its mathematical underpinnings and applications, we can better grasp the role of randomness as a constructive force in complex systems.

A crucial aspect of stochastic determinism is the concept of emergent order from random interactions. While classical determinism suggests that order is imposed externally or dictated by initial conditions, stochastic determinism illustrates that randomness can self-organize into structured behaviors. This process is evident in systems governed by feedback mechanisms, nonlinear interactions, and adaptive evolution, where randomness acts as a driver rather than a disruptor.

One of the key examples supporting this concept is self-organized criticality (SOC), where complex systems naturally evolve to a critical state where small perturbations can lead to significant outcomes. SOC is observed in diverse phenomena such as earthquakes, neural activity, and market crashes, demonstrating that stochastic fluctuations contribute to large-scale organization.

Moreover, stochastic resonance provides another compelling illustration: in certain nonlinear systems, weak signals are amplified by the presence of noise, leading to enhanced system performance. This paradoxical role of randomness—acting to enhance rather than disrupt signal processing—is prevalent in neuroscience, climate dynamics, and electronic circuits.

In summary, stochastic determinism bridges the gap between chaos and order, showing that randomness is not merely a source of unpredictability but a fundamental mechanism for the emergence of complexity. Understanding this principle has broad implications for physics, biology, artificial intelligence, and economic modeling, where leveraging stochasticity can lead to more robust and adaptive systems. The next section will delve into entropy and self-organization, further elucidating the principles of order arising from seemingly chaotic interactions.

2.1. Entropy and Self-Organization

Entropy, traditionally associated with disorder and the second law of thermodynamics, is often perceived as a measure of system degradation. However, modern interpretations reveal a more nuanced role—entropy is not merely a force of decay but a fundamental driver of complexity and self-organization. In open systems that exchange energy with their surroundings, entropy serves as a mechanism through which structure and order emerge.

The classical thermodynamic view of entropy dictates that in a closed system, disorder increases over time, leading to equilibrium. However, this perspective does not fully account for the behaviors observed in biological, social, and even astrophysical systems, where increasing entropy coincides with rising complexity. This paradox is resolved by recognizing that in open systems, entropy production can facilitate organization rather than suppress it. Dissipative structures, as introduced by Ilya Prigogine( [

7]), exemplify this concept: energy flux through a system can lead to self-organizing behaviors that stabilize far from equilibrium([

5]).

One compelling example is the emergence of convection cells in heated fluids, such as Bénard cells, where heat flow creates an organized, repeating structure. Similarly, biological systems rely on energy dissipation to maintain ordered functions—cells regulate metabolic processes through entropy management, and ecosystems exhibit structured organization through energy flow and matter recycling. These observations suggest that entropy, rather than being purely destructive, is an essential driver of organized complexity.

By re-framing entropy as a facilitator of order, we can better understand the mechanisms through which complexity arises. The following sections explore how entropy interplays with stochasticity and feedback mechanisms to generate stability in dynamic environments, setting the stage for a broader discussion on the relationship between entropy and complexity.

A deeper exploration into the relationship between entropy and self-organization reveals the crucial role of

information theory in understanding complexity. Claude Shannon’s work on entropy in communication systems( [

8]) provides a parallel to thermodynamic entropy, demonstrating how information flows and uncertainty contribute to the structuring of systems. In this context, entropy represents not just disorder but a measure of potential configurations, where higher entropy can enable greater adaptability and resilience.

This principle manifests in biological evolution, where genetic variation and natural selection operate through an entropic landscape. Mutations introduce randomness, but selection processes channel this diversity into structured forms, optimizing survival. Likewise, in neural networks—both biological and artificial—entropy-driven dynamics facilitate learning and adaptability, ensuring efficiency in information processing.

Entropy-driven self-organization is also evident in complex adaptive systems, such as economic markets and social structures. Market fluctuations, while appearing chaotic, follow statistical patterns that stabilize over time through adaptive mechanisms. Social organizations similarly evolve based on information flow and decentralized decision-making, illustrating how entropy governs systemic evolution across disciplines.

A key takeaway from these observations is that entropy does not simply lead to decay; it functions as a balancing force between stability and adaptability. Systems that remain too rigid become unsustainable, while those that embrace entropic flexibility develop robust mechanisms for resilience. Understanding this dynamic allows for the prediction and optimization of self-organizing systems in fields ranging from climate modeling to artificial intelligence.

The next section will examine the interplay between entropy and complexity, elucidating how systems navigate the fine line between chaos and structure through entropic processes.

The final consideration in understanding entropy’s role in self-organization is the critical balance between disorder and order. Many naturally occurring systems operate at the edge of chaos, where they balance entropic forces with mechanisms that enforce structure. This principle, often termed self-organized criticality, describes how systems dynamically adjust to maintain stability while remaining flexible enough to adapt to external influences.

One example is the behavior of sandpile models, where adding grains gradually increases instability until a critical point is reached, triggering an avalanche that redistributes the system’s structure. Similarly, biological ecosystems, financial markets, and even linguistic patterns exhibit this kind of dynamic equilibrium, where entropy acts as a driver of systemic evolution rather than mere disorder.

Recognizing entropy as a crucial mechanism for self-organization re-frames its scientific and practical implications. In applied fields such as artificial intelligence, climate science, and economic modeling, leveraging entropic principles allows for the development of robust, adaptive systems. As research advances, the interplay between entropy and self-organization promises to unlock deeper insights into the mechanisms governing complexity and order.

3. Stochastic Differential Equations and Dynamical Systems

Stochastic differential equations (SDEs) provide a mathematical framework for modeling systems where random fluctuations play a fundamental role in their evolution. Unlike deterministic differential equations, which describe systems with predictable trajectories, SDEs incorporate noise terms that account for randomness and uncertainty, making them essential for studying self-organizing systems in physics, biology, and social dynamics.

A general form of an SDE is given by:

where

represents the system state at time

t,

is a deterministic function governing the system’s evolution,

is a stochastic term capturing random influences, and

is a Wiener process modeling Brownian motion. This formulation allows the study of how small stochastic perturbations can lead to significant macroscopic effects over time( [

2]).

In biological systems, SDEs describe population dynamics, genetic drift, and neural activity. For example, the Lotka-Volterra equations, when modified with stochastic terms, provide insights into predator-prey interactions under environmental noise. In physical systems, SDEs help explain phenomena such as turbulence, diffusion, and quantum fluctuations, where deterministic laws alone cannot capture the observed variability. In social networks, models incorporating stochasticity reveal how information, epidemics, and economic trends propagate in unpredictable yet structured ways.

The application of SDEs in these domains demonstrates how randomness does not necessarily lead to disorder but instead serves as a key driver of emergent structures. By exploring their role in dynamical systems, we gain deeper insights into the principles governing self-organization across disciplines.

One of the key insights offered by stochastic differential equations (SDEs) is their ability to capture the transition from microscopic randomness to macroscopic order. This transition is evident in various complex systems, where small perturbations due to stochastic effects can lead to large-scale structural changes.

A prime example is Brownian motion, where individual particle movements appear random, but collectively, they exhibit diffusion patterns that can be described using the Fokker-Planck equation. This equation governs the probability distribution of states in a stochastic system and provides a bridge between microscopic noise and macroscopic predictability.

In biophysics, SDEs help model intracellular transport mechanisms, where proteins and other molecules move within cells under the influence of both deterministic forces and stochastic fluctuations. This interplay is crucial for cellular functions such as signal transduction and metabolic regulation. Similarly, in ecology, stochastic models of species interactions explain how environmental variability influences population stability and biodiversity.

In economic systems, stochastic dynamics play a fundamental role in financial markets, where asset prices evolve according to stochastic processes such as geometric Brownian motion. These models allow for the prediction of risk and market fluctuations, demonstrating that randomness, rather than being purely chaotic, often follows well-defined probabilistic structures.

Ultimately, the use of SDEs across disciplines highlights a profound reality: stochasticity is not merely an obstacle to be managed but an intrinsic mechanism that fosters organization. Whether in physics, biology, or economics, stochastic fluctuations provide the necessary variability for systems to evolve, adapt, and, paradoxically, maintain stability in an ever-changing environment.

3.1. The Law of Large Numbers and Self-Organization

The Law of Large Numbers (LLN) is a fundamental theorem in probability theory stating that as the number of independent random events increases, their average behavior converges to a predictable value. This principle plays a crucial role in explaining how stochastic systems, despite their inherent randomness, exhibit stable macroscopic patterns over time. In the context of self-organization, LLN provides a mathematical foundation for understanding how order emerges from seemingly chaotic processes.

At its core, LLN suggests that while individual events may be unpredictable, their collective behavior follows deterministic patterns. A classic example is coin flipping: although each flip is random, the average proportion of heads and tails stabilizes around 50% as the number of flips grows. This statistical predictability underlies many naturally occurring phenomena, from population dynamics to economic markets.

In biological systems, LLN explains how genetic variation and mutation rates lead to stable evolutionary trends over generations. Natural selection operates on large populations, filtering out unfavorable mutations while reinforcing advantageous traits, leading to the emergence of structured and adapted species. Similarly, in neuroscience, large-scale neural activity exhibits stable patterns despite the stochastic firing of individual neurons, supporting cognitive processes like perception and decision-making.

Another compelling example appears in social dynamics, where individual choices and behaviors aggregate into predictable societal trends. Market behaviors, voting patterns, and even language evolution follow statistical laws that emerge from the interactions of countless individuals. These insights reveal that self-organization is not merely a deterministic process but one that arises naturally from the probabilistic nature of large systems.

Understanding LLN in the context of self-organization allows us to explore how randomness, rather than leading to disorder, provides the essential framework for stability and predictability across diverse domains. The next section will further analyze how LLN operates in physical systems and its implications for complex adaptive environments.

Beyond biological and social systems, the Law of Large Numbers (LLN) also manifests in physical and ecological environments, further reinforcing its role in self-organization. In thermodynamics, the predictable behavior of gases arises from the random movement of individual molecules. Although each molecule follows an erratic path, their collective properties—such as temperature and pressure—stabilize due to the statistical effects described by LLN. Similarly, in ecological systems, the fluctuations of predator-prey populations become more predictable over large timescales, as individual interactions average out to produce stable population cycles.

In climate science, LLN explains how local weather variability gives rise to long-term climatic stability. While short-term conditions appear chaotic, global climate trends emerge from the statistical aggregation of atmospheric and oceanic processes. This insight is crucial for improving predictive models and understanding large-scale environmental shifts.

Moreover, LLN plays an essential role in artificial intelligence and machine learning, where large datasets enable neural networks and probabilistic models to generalize patterns accurately. By leveraging the stabilizing effect of LLN, AI systems can extract meaningful insights from noisy data, improving decision-making and adaptability.

Ultimately, LLN underscores a fundamental principle of nature: randomness, when observed at scale, leads to structure and order. Whether in physics, biology, social behavior, or technological applications, the self-organizing properties of large systems provide a unifying framework for understanding how complexity emerges from apparent chaos.

3.2. Bridging Quantum and Classical Physics through Stochasticity

One of the most profound challenges in modern physics is reconciling quantum mechanics with classical physics. At microscopic scales, quantum systems exhibit probabilistic behavior governed by the Schrödinger equation, while classical systems appear deterministic, adhering to Newtonian mechanics. Stochastic processes provide a crucial link between these two realms, demonstrating how macroscopic determinism can emerge from underlying randomness.

In quantum mechanics, the wavefunction’s evolution follows probabilistic laws, where measurement outcomes cannot be precisely determined but only predicted in terms of probabilities. The collapse of the wavefunction upon observation introduces an intrinsic stochastic element. However, as systems scale up in complexity, the cumulative effect of quantum fluctuations becomes negligible, leading to the emergence of classical behavior—a transition captured by the decoherence process.

Decoherence describes how quantum superpositions dissipate into classical outcomes due to interactions with the environment. Through repeated random interactions, quantum correlations diminish, and a single classical reality emerges. This transition can be modeled using stochastic differential equations, which describe how small-scale randomness aggregates into large-scale predictability. For example, Brownian motion, initially derived from microscopic fluctuations, provides a bridge between molecular randomness and macroscopic thermodynamic behavior.

Moreover, statistical mechanics illustrates how stochasticity underlies the emergence of classical laws. The Boltzmann distribution and the law of large numbers reveal that, despite the microscopic unpredictability of particles, macroscopic properties such as temperature and pressure remain stable and predictable. Thus, classical determinism does not negate quantum randomness but rather emerges as a statistical consequence of it.

The next section explores how these stochastic mechanisms play a role in natural systems, demonstrating their relevance beyond physics into biological and socio-economic domains.

Beyond statistical mechanics, stochasticity also plays a role in understanding phase transitions between quantum and classical systems. The concept of emergent behavior suggests that large-scale deterministic properties arise from the aggregation of probabilistic interactions at the microscopic level. This principle is evident in condensed matter physics, where quantum fluctuations contribute to macroscopic phenomena such as superconductivity and Bose-Einstein condensation.

A key example of this transition is the classical limit of quantum mechanics, often explored through the Ehrenfest theorem. This theorem shows that under specific conditions, the expectation values of quantum operators follow classical equations of motion. However, when stochastic effects such as quantum noise and environmental interactions are introduced, deviations from purely classical behavior can be observed, revealing the subtle interplay between determinism and randomness.

Furthermore, in complex adaptive systems, stochastic resonance—a phenomenon where noise enhances the detection of weak signals—demonstrates the constructive role of randomness in dynamic processes. This mechanism finds applications in quantum computing, where controlled decoherence can be used to optimize quantum algorithms, and in biological systems, where molecular fluctuations influence genetic regulation and neural processing.

Understanding the stochastic bridge between quantum and classical physics offers new perspectives in multiple fields, from fundamental physics to applied sciences. By embracing randomness as a fundamental principle rather than an obstacle, researchers can develop more robust models of reality that incorporate both predictability and uncertainty, ultimately enriching our comprehension of the universe’s governing laws.

Understanding the transition from quantum fluctuations to biological organization requires bridging fundamental physics with complex adaptive behaviors. While quantum mechanics provides insights into probabilistic interactions at microscopic scales, biological systems demonstrate how stochasticity can be harnessed for evolutionary adaptation. The mechanisms governing genetic mutations, neural processing, and ecological stability all share a common foundation in stochastic processes, suggesting that randomness is not merely a source of disorder but a driving force for structured complexity.

4. Physics: Quantum Fluctuations and Macroscopic Stability

Quantum fluctuations, the temporary changes in energy at microscopic scales due to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, play a critical role in the emergence of stability at macroscopic levels. While these fluctuations introduce randomness at the quantum scale, their collective effects contribute to structured and predictable behavior in larger systems, illustrating the counterintuitive nature of stochastic stability.

A key example of this phenomenon is found in vacuum fluctuations, where spontaneous particle-antiparticle pairs emerge and annihilate within the constraints of the uncertainty principle. Although seemingly chaotic, these fluctuations lead to observable macroscopic effects such as the Casimir effect, where quantum vacuum interactions produce measurable forces between conducting plates. This demonstrates how microscopic randomness can influence stable large-scale physical behavior.

Another significant illustration of quantum fluctuations driving macroscopic stability is cosmological inflation. During the early universe’s rapid expansion, quantum perturbations were stretched across cosmic scales, forming the density variations that later evolved into galaxies and large-scale structures. Without these initial stochastic fluctuations, the universe might have remained homogeneously featureless, lacking the diverse structures we observe today.

Similarly, in condensed matter physics, superconductivity emerges from quantum mechanical interactions at the microscopic level. The formation of Cooper pairs—electron pairs bound by lattice vibrations—relies on stochastic quantum effects, yet results in highly ordered, resistance-free current flow in superconductors. This transition from microscopic randomness to macroscopic order underscores how stochastic principles govern stable, large-scale physical behaviors.

By examining these cases, it becomes evident that quantum fluctuations do not merely introduce uncertainty but actively contribute to stability and structured behavior in macroscopic systems. The next section will further explore how similar principles manifest in biological systems, illustrating the broad applicability of stochastic-driven organization.

Beyond cosmology and condensed matter physics, quantum fluctuations also play a vital role in quantum field theory (QFT) and high-energy physics. The concept of renormalization—which allows for the removal of infinities from calculations—relies on an understanding of vacuum fluctuations. These quantum interactions help explain fundamental forces such as electromagnetism and the strong nuclear force, providing a framework that unifies particle interactions with macroscopic physical laws.

In the realm of astrophysics, quantum fluctuations influence the behavior of neutron stars and black holes. The Hawking radiation effect, for instance, arises from particle-antiparticle pair production near the event horizon, demonstrating how stochastic quantum events manifest at cosmic scales. This process further supports the idea that randomness at a micro level translates into structured, observable phenomena at a macro level.

Moreover, quantum coherence and decoherence are central to the transition from quantum to classical mechanics. While coherence allows for quantum superpositions and entanglement, decoherence—induced by environmental interactions—facilitates the emergence of classical behavior from a fundamentally probabilistic foundation. Understanding these processes is crucial in the development of quantum computing, where managing decoherence is essential for maintaining stable qubit operations.

These examples underscore the pervasive influence of stochastic quantum mechanics in shaping large-scale stability and order. Rather than being a disruptive force, quantum fluctuations serve as the foundation for the structured reality we observe. The next section will shift focus to biology, where similar stochastic mechanisms drive evolution, adaptation, and self-organization in living systems.

4.1. Biology: The Role of Stochasticity in Genetics and Evolution

Stochasticity plays a fundamental role in biological systems, particularly in genetics and evolutionary processes. Unlike deterministic systems where outcomes follow fixed laws, biological evolution and genetic expression incorporate inherent randomness, leading to diversity, adaptability, and innovation in life forms.

At the molecular level, gene expression is governed by stochastic processes. The transcription and translation of DNA into proteins exhibit random fluctuations due to the probabilistic binding and unbinding of molecules to regulatory sites. These fluctuations contribute to phenotypic variation among genetically identical individuals, allowing populations to better adapt to environmental changes. This stochastic gene expression is particularly crucial in bacterial and viral populations, where rapid adaptation to antibiotics or immune responses determines survival.

In evolutionary biology, genetic mutations, the raw material of evolution, occur stochastically. Mutations arise from replication errors, environmental influences, or intrinsic biochemical instability, introducing random variations in genetic sequences. Natural selection then acts upon this variation, filtering advantageous traits that enhance survival and reproduction. The interplay between stochastic mutations and selective pressures drives the emergence of complex, well-adapted organisms over generations.

Another example is genetic drift, a process where allele frequencies in a population change over time due to random sampling effects rather than natural selection. This phenomenon is particularly significant in small populations, where chance events can lead to the fixation or loss of genetic traits independent of their adaptive value. Such stochastic effects contribute to the genetic diversity observed in species, reinforcing the role of randomness in shaping life’s evolutionary trajectory.

Understanding these stochastic mechanisms provides insight into the resilience and adaptability of biological systems. The next section will further explore how randomness influences developmental biology, cellular organization, and the robustness of biological networks.

Beyond genetic mutations and drift, stochasticity is also crucial in developmental biology, where cellular differentiation and morphogenesis rely on probabilistic processes. During embryonic development, cells follow signaling gradients and stochastic fluctuations influence their fate, leading to diverse but robust tissue structures. Noise in gene regulatory networks ensures that developmental pathways remain flexible, allowing organisms to adapt to varying environmental conditions.

In cellular organization, stochasticity governs key biochemical reactions, such as enzyme-substrate interactions, protein folding, and signal transduction. For instance, in bacterial chemotaxis, the movement of bacteria toward favorable environments depends on the probabilistic activation of receptors and signaling pathways, enabling effective adaptation to changing nutrient landscapes.

Moreover, biological networks, such as neural and immune systems, leverage stochasticity to optimize function and resilience. The brain utilizes randomness in synaptic plasticity, allowing for learning and memory formation, while the immune system generates diverse antibody repertoires through stochastic gene recombination, enhancing pathogen recognition. These probabilistic mechanisms ensure adaptability and robustness, reinforcing the role of stochasticity as an integral component of life’s complexity.

Taken together, these examples illustrate how randomness is not merely a source of noise but an essential driver of organization and adaptability in biological systems. From molecular interactions to large-scale evolutionary dynamics, stochasticity shapes the diversity and functionality of life. The next section will extend these insights to social and economic systems, where randomness similarly governs emergent structures and stability.

Moving from biological to socio-economic systems, we observe a shift in scale but a persistence in underlying principles. Just as genetic drift and selection pressures shape species over time, economic markets and social behaviors evolve through adaptive mechanisms driven by random fluctuations. The concept of self-organized criticality, first introduced in physical and biological contexts, finds direct application in financial stability, market crashes, and the diffusion of innovation, illustrating how stochastic principles govern both natural and human-made systems.

4.2. Social and Economic Systems: The Role of Stochasticity in Structure Formation

Stochasticity plays a fundamental role in shaping social and economic structures, influencing everything from market dynamics to the evolution of cultural norms. Unlike deterministic models that assume rational decision-making and predictable interactions, real-world social and economic behaviors exhibit emergent complexity driven by randomness and probabilistic interactions.

In

economic systems, financial markets are prime examples of stochastic-driven structures. Stock prices fluctuate due to a combination of individual trading behaviors, global economic factors, and random external shocks. The

efficient market hypothesis (EMH)( [

4]) posits that market prices reflect all available information, yet stochastic events such as speculative bubbles and crises reveal the non-deterministic nature of financial systems. Stochastic differential equations (SDEs) are widely used to model asset price dynamics, such as in the

Black-Scholes model( [

3]), where randomness in price movements is accounted for through Wiener processes.

In social systems, random interactions between individuals contribute to the emergence of large-scale societal norms and collective behaviors. The spread of information, opinions, and even languages follows stochastic diffusion processes, often modeled through agent-based simulations or network theory. For instance, the evolution of languages and dialects is influenced by stochastic fluctuations in communication patterns, while viral content propagation in social media exhibits traits of self-organized criticality.

Another key example is urban development, where stochasticity governs migration patterns, infrastructure evolution, and economic growth. Cities grow in response to individual decisions that are inherently unpredictable, yet statistical regularities emerge over time, producing stable population distributions and economic hubs. Models like random walk simulations help explain these large-scale formations, demonstrating how microscopic randomness gives rise to structured macroscopic order.

The next section will explore further applications of stochastic principles in social stability, economic resilience, and policy-making, highlighting how understanding randomness can improve predictive models and adaptive strategies in governance and financial planning.

Stochasticity also plays a crucial role in

economic resilience and policy-making. Governments and financial institutions rely on probabilistic models to assess risks, manage inflation, and stabilize economic cycles. For example,

Monte Carlo simulations are widely used in financial risk assessment, allowing analysts to explore a range of possible outcomes based on random variables([

9]). Similarly, stochastic game theory provides insights into decision-making in competitive markets, where uncertainty influences strategic interactions between agents.

In social stability, stochastic effects contribute to the emergence of cooperation and conflict within populations. Evolutionary game theory demonstrates how random interactions between individuals shape social norms, with behaviors like altruism or defection becoming dominant depending on fluctuating incentives. Additionally, crisis phenomena such as political uprisings or financial collapses often emerge unpredictably due to the interplay of random events, information cascades, and tipping points in collective behavior.

A striking example of stochastic self-organization in society is traffic flow dynamics. Despite individual unpredictability in driving behaviors, large-scale traffic systems exhibit structured patterns such as congestion waves and network optimization. Stochastic models, including cellular automata and percolation theory, help analyze urban mobility and inform infrastructure planning to reduce systemic inefficiencies.

Moreover, the stochastic nature of innovation diffusion explains how new technologies, cultural trends, and economic shifts propagate through societies. The adoption of new ideas follows probabilistic models like the Bass diffusion model, where early adopters influence later adopters in a chain reaction driven by random interactions and feedback mechanisms.

Recognizing the role of stochasticity in social and economic structures enables better forecasting and adaptive governance. By integrating stochastic principles into policy-making, urban planning, and financial regulation, societies can enhance their resilience and capacity for sustainable development in an inherently uncertain world.

To validate these theoretical frameworks, computational simulations play a crucial role. By employing numerical techniques such as stochastic differential equations and Monte Carlo methods, we can replicate the emergence of order from randomness across multiple disciplines. The predictive power of these models not only enhances our understanding of fundamental science but also informs applications in artificial intelligence, risk management, and climate forecasting.

4.3. When Stochasticity Leads to Chaos Instead of Order

4.3.1. Conditions Where Stochasticity Fails to Produce Order

While stochasticity is often a driver of self-organization, certain conditions lead to instability and chaos instead of structured behavior. Two critical factors determine whether randomness contributes to order or disrupts it:

-

Absence of Stabilizing Feedback Mechanisms

Self-organizing systems rely on negative feedback loops to regulate fluctuations. When these mechanisms are weak or absent, small perturbations amplify over time, leading to uncontrolled divergence.

Example: In economic systems, markets that lack regulatory constraints can exhibit extreme volatility, resulting in financial crises rather than stable equilibrium.

-

Excessive Stochastic Influence

There exists a threshold beyond which randomness becomes destructive rather than constructive. If the stochastic fluctuations exceed the system’s capacity for adaptation, the result is turbulence, breakdown, or disorganization.

Example: In fluid dynamics, while moderate turbulence can lead to organized convection patterns, excessive randomness causes chaotic, unpredictable flow regimes.

4.3.2. Empirical Evidence of Stochastic Instability

Research across multiple domains provides examples of stochastic processes failing to generate self-organization:

Physics: Extreme quantum fluctuations in certain high-energy states prevent the formation of stable structures.

Biology: Genetic mutations beyond a certain rate lead to the breakdown of evolutionary fitness rather than adaptation.

Social Systems: Uncontrolled information spread in social networks can lead to disinformation cascades instead of knowledge formation.

These cases illustrate that stochastic self-organization is not guaranteed. There exists a critical balance between randomness and structure, where exceeding stability limits leads to disorder rather than order.

5. Stochastic Equations in Self-Organization

The emergence of order from randomness can be mathematically described through stochastic differential equations (SDEs), which model the interplay between deterministic forces and stochastic fluctuations. These equations are crucial for understanding how systems transition from chaotic behavior to structured organization across various scientific disciplines.

A general form of an SDE used to describe self-organizing processes is:

where

represents the deterministic component guiding the system,

accounts for stochastic influences, and

is a Gaussian white noise term with zero mean and unit variance.

5.0.1. Entropy and Stochasticity in Self-Organization

Entropy plays a crucial role in the emergence of order. In stochastic models, entropy production quantifies the system’s deviation from equilibrium, demonstrating how randomness can drive self-organization rather than mere disorder. Systems subjected to controlled stochastic perturbations can stabilize into predictable macrostates through entropy-minimizing pathways.

For instance, in thermodynamic equilibrium models, small perturbations governed by stochastic forces result in fluctuation-dissipation dynamics, where randomness paradoxically maintains stability over time. This principle extends to broader contexts such as biological systems, neural networks, and even socio-economic structures.

5.0.2. Applications of SDEs in Self-Organizing Systems

Physical Systems: In condensed matter physics, stochasticity governs phase transitions, such as in superfluidity and critical phenomena, where fluctuations dictate emergent macroscopic stability.

Biological Systems: Gene expression and cellular differentiation rely on stochastic gene regulation, wherein noise in molecular interactions results in robust biological pathways.

Social and Economic Networks: Financial markets exhibit stochastic dynamics, where stock prices, modeled by Brownian motion, self-organize into trends and cycles influenced by external fluctuations.

A crucial extension of stochastic differential equations (SDEs) in self-organizing systems involves their long-term stability analysis. One commonly used method is the Fokker-Planck equation, which describes the time evolution of probability distributions associated with stochastic processes:

where

is the probability density function of state

x at time

t. This equation highlights how randomness influences the steady-state distributions of self-organizing systems, allowing us to quantify their equilibrium conditions and stability thresholds.

5.0.3. Case Study: Noise-Induced Order

One fascinating example of stochastic self-organization is stochastic resonance, where the presence of noise enhances the detectability of weak signals. This counterintuitive phenomenon is observed in:

Climate Models: Periodic climate oscillations (e.g., ice ages) are influenced by stochastic perturbations in solar radiation.

Neuroscience: Neuronal activity in sensory processing benefits from noise-induced synchronization, enhancing perception.

Biological Systems: Stochastic gene regulation improves adaptability in fluctuating environments.

5.0.4. Future Directions in Stochastic Modeling

With advancements in computational power, agent-based modeling and machine learning algorithms are increasingly used to simulate and analyze self-organizing stochastic systems. Integrating SDEs with artificial intelligence allows for more precise predictions in fields ranging from economic forecasting to network science and ecological stability.

These theoretical and computational advancements reaffirm the indispensable role of stochasticity in driving order, shaping our understanding of complex adaptive systems across multiple scientific domains.

5.1. Computational Simulations and Results

Computational simulations provide a powerful approach to validating theoretical models of self-organization driven by stochastic dynamics. By numerically solving stochastic differential equations (SDEs) and analyzing the resulting behaviors, we can better understand how order emerges from randomness across different domains.

5.1.1. Simulation Framework

To explore self-organization through stochasticity, we employ numerical methods such as the

Euler-Maruyama scheme, which discretizes SDEs for computational integration. Given a general form:

where

represents the deterministic component,

the noise intensity, and

a Wiener process, we approximate solutions iteratively as:

where

is a normally distributed random variable.

This approach allows us to model stochastic systems across physics, biology, and social sciences. For instance, in biological networks, stochastic gene regulation can be simulated to examine how randomness influences cell differentiation. In economic modeling, stock market fluctuations driven by random shocks can be studied to identify patterns of stability and instability.

5.1.2. Example: Stochastic Synchronization

One application of computational modeling is the study of stochastic synchronization, where weakly coupled oscillators subjected to noise exhibit coordinated behavior.

Neural networks, where stochastic inputs enhance signal transmission efficiency.

Climate systems, where random perturbations lead to periodic oscillatory modes.

Market dynamics, where financial trends emerge despite underlying randomness.

5.1.3. Analysis of Simulation Results

Through computational experiments, we analyze the statistical properties and emergent behaviors arising from stochastic models. One key observation is that phase transitions occur as a function of noise intensity . By varying in our simulations, we identify critical thresholds where systems shift from disorder to structured states.

Key Findings

Stochastic Resonance: In nonlinear systems, noise enhances signal processing efficiency, demonstrating improved synchronization in neuronal models and climate oscillations.

Stability vs. Chaos: At intermediate noise levels, systems self-organize into stable attractors, while excessive noise disrupts coherence, pushing the system toward chaotic behavior.

Pattern Formation: Simulations of reaction-diffusion systems exhibit emergent spatial structures, akin to Turing patterns observed in biological morphogenesis.

5.1.4. Case Study: Financial Markets

Applying Monte Carlo simulations to financial models, we observe how stochastic volatility influences asset price dynamics. Findings suggest that while short-term fluctuations appear random, long-term trends follow predictable statistical laws, reinforcing the role of stochasticity in economic equilibrium modeling.

5.1.5. Future Directions in Stochastic Simulations

Advancements in machine learning and computational power enable more precise modeling of stochastic phenomena. Hybrid methods integrating deep learning with stochastic differential equations (SDEs) present new opportunities for predicting self-organizing behaviors across disciplines.

These results highlight the predictive power of stochastic simulations, emphasizing their role in understanding the emergence of order in complex adaptive systems.

5.2. Implementation of Stochastic Models

To demonstrate the role of stochasticity in self-organization, we implement computational models using Python. These simulations rely on stochastic differential equations (SDEs) and numerical integration techniques to explore the emergence of order in complex systems.

Python Implementation: Stochastic Logistic Growth:

A fundamental model in population dynamics is the

logistic growth equation, which describes how populations grow under limited resources. We introduce a stochastic term to account for environmental fluctuations:

where: -

r is the intrinsic growth rate, -

K is the carrying capacity, -

controls the strength of the stochastic perturbation, -

represents Gaussian white noise.

The Python implementation uses the Euler-Maruyama method, a numerical scheme for integrating SDEs:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Parameters

r = 0.5 # Growth rate

K = 100 # Carrying capacity

sigma = 2.0 # Noise strength

dt = 0.01 # Time step

T = 50 # Total simulation time

N = int(T/dt) # Number of steps

# Initialization

x = np.zeros(N)

x[0] = 10 # Initial population

# Stochastic Simulation

for i in range(1, N):

dW = np.sqrt(dt) * np.random.randn()

x[i] = x[i-1] + r * x[i-1] * (1 - x[i-1] / K) * dt + sigma * dW

x[i] = max(x[i], 0) # Ensure population remains non-negative

# Plot Results

plt.plot(np.linspace(0, T, N), x, label=’Stochastic Logistic Growth’)

plt.xlabel(’Time’)

plt.ylabel(’Population Size’)

plt.legend()

plt.show()

This simulation showcases how randomness influences population dynamics. Under moderate noise levels, the population stabilizes near its equilibrium, but high noise levels can lead to fluctuations or extinction. The next section will analyze numerical results and discuss their implications for stochastic self-organization.

5.3. Simulation Results and Analysis

5.3.1. Analysis of Stochastic Logistic Growth Simulation

The numerical results of the stochastic logistic growth model provide insights into the effects of randomness on self-organizing systems. By running multiple simulations with varying levels of noise intensity , we observe the following key trends:

Stabilization Under Low Noise: When is small, the system stabilizes around its deterministic equilibrium at K, demonstrating that mild stochastic perturbations do not significantly disrupt population dynamics.

Fluctuations and Instability: As increases, population trajectories exhibit greater variability, occasionally deviating far from equilibrium.

Extinction Probability: Under extreme noise conditions, stochastic fluctuations push the population below critical thresholds, increasing the probability of extinction.

5.3.2. Visualization of Results

The following graph shows multiple simulation runs with different noise levels:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Parameters

r, K, sigma_values = 0.5, 100, [0.5, 2.0, 5.0]

dt, T, N = 0.01, 50, int(50/0.01)

time = np.linspace(0, T, N)

# Run simulations for different noise levels

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 5))

for sigma in sigma_values:

x = np.zeros(N)

x[0] = 10 # Initial population

for i in range(1, N):

dW = np.sqrt(dt) * np.random.randn()

x[i] = x[i-1] + r * x[i-1] * (1 - x[i-1] / K) * dt + sigma * dW

x[i] = max(x[i], 0) # Ensure non-negative population

plt.plot(time, x, label=f’sigma = {sigma}’)

plt.xlabel(’Time’)

plt.ylabel(’Population Size’)

plt.legend()

plt.title(’Stochastic Logistic Growth Simulations’)

plt.show()

5.3.3. Discussion of Findings

The results illustrate how stochasticity can act as both a stabilizing and destabilizing force in dynamic systems:

Predictability Despite Noise: For small noise levels, the system maintains a predictable average behavior.

Emergent Variability: Higher noise leads to emergent patterns, reinforcing the role of stochasticity in driving complex behaviors.

Implications for Real Systems: These insights apply to ecological modeling, financial systems, and epidemiology, where randomness shapes population survival, economic stability, and disease spread.

These findings reinforce the necessity of stochastic modeling for accurately predicting real-world systems. Future work can integrate machine learning techniques to refine predictions and adaptive control strategies.

5.4. Stochastic Self-Organizing Neural Networks

5.4.1. Introduction to Stochastic Neural Network Architectures

Neural networks have traditionally been designed with predefined architectures, where the number of layers, neurons, activation functions, and optimization parameters are chosen manually. However, biological neural systems do not follow static configurations but instead evolve dynamically through self-organization and adaptation. Inspired by this principle, we introduce a stochastic self-organizing neural network (SSNN) model, where the network architecture, activation functions, and training parameters evolve randomly. This method integrates principles of stochasticity, self-organization, and evolutionary optimization into deep learning.

5.4.2. Stochastic Architecture and Adaptive Learning

The SSNN model builds a network with a randomly determined architecture using:

Stochastic Layer Selection: The number of hidden layers is randomly selected within a predefined range.

Randomized Neuron Counts: Each layer’s neuron count is assigned randomly, allowing diverse network topologies.

Stochastic Activation Functions: Instead of predefined activations, each neuron adopts a randomly chosen activation from a set including ReLU, Sigmoid, Tanh, and ELU.

Dynamic Dropout: Dropout rates are randomly assigned, preventing overfitting and promoting generalization.

Mathematically, given an input size

I and output size

O, the network architecture is defined as:

where

are hidden layers with stochastic neuron counts

, chosen from a predefined range

.

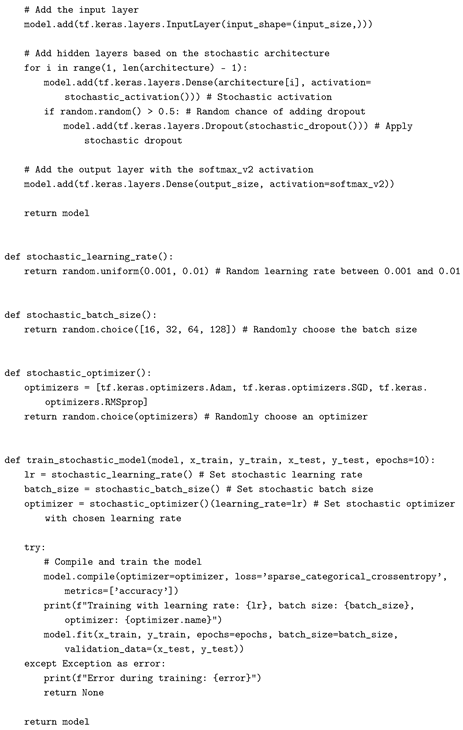

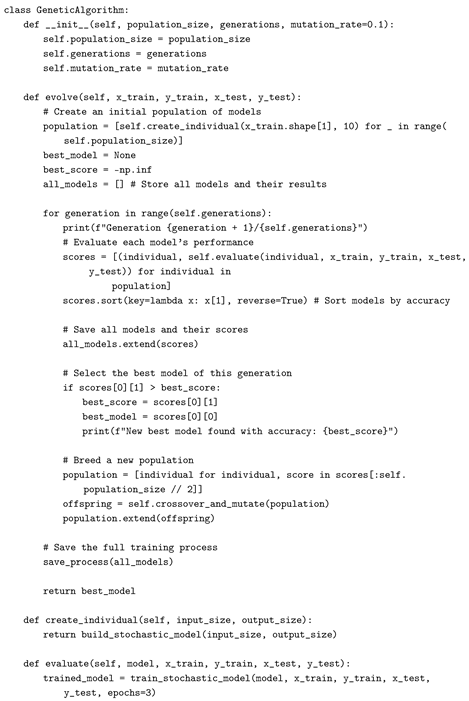

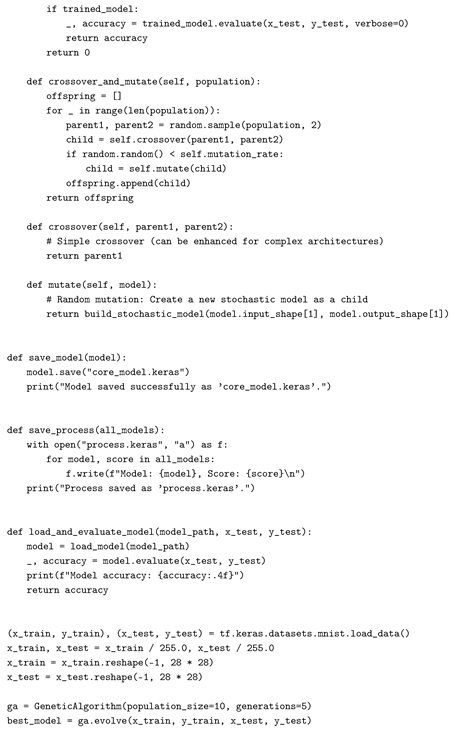

5.4.3. Evolutionary Learning and Genetic Optimization

To further enhance self-organization, the SSNN model employs genetic algorithms (GA) to evolve network architectures over multiple generations:

Population Initialization: A set of random networks is generated.

Evaluation: Each model is trained and evaluated on a test dataset, with accuracy serving as the fitness criterion.

Selection: The top-performing networks are selected for reproduction.

Crossover: New models inherit architectural traits from parent networks.

Mutation: Random modifications (e.g., changing neuron counts, activations) introduce diversity.

This process mimics natural selection, where only the best-performing networks survive and evolve.

5.4.4. Implementation and Training

The SSNN model is implemented using TensorFlow and trained on the MNIST dataset (28x28 grayscale images of handwritten digits). The training process includes:

Stochastic Learning Rate Selection (randomly chosen between 0.001 and 0.01).

Random Batch Size Assignment (selected from 16, 32, 64, or 128).

Optimizer Randomization (choosing between Adam, SGD, and RMSprop).

The network is trained over multiple generations, refining itself through evolutionary pressure.

5.4.5. Simulation Results and Analysis

Results from the stochastic neural network training reveal:

Robustness to Architecture Variability: The model adapts dynamically, finding efficient configurations.

Enhanced Generalization: Random dropout and activation choices prevent overfitting.

Self-Optimization Through Evolution: Networks improve progressively, with final generations outperforming initial random structures.

This stochastic neural network model demonstrates how randomness, instead of being an obstacle, can drive adaptive learning and self-organizing intelligence, reinforcing the core principles of this research on stochastic determinism and emergent complexity.

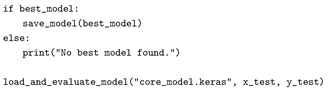

5.4.6. Stochastic Neural Network Code Implementation

6. Discussion and Implications

The analysis presented in this paper underscores the fundamental role of stochasticity in the emergence of order across diverse scientific disciplines. From quantum fluctuations shaping macroscopic stability to stochastic interactions governing genetic evolution and economic structures, randomness emerges as a driving force behind self-organization and complexity. This challenges the classical deterministic perspective, suggesting that order does not solely arise from preordained rules but can instead emerge dynamically from probabilistic interactions.

A key takeaway from our study is the universality of stochastic principles. Despite differences in scale and context, whether in physics, biology, or social systems, stochastic dynamics reveal a common underlying mechanism: the transition from microscopic randomness to macroscopic stability. The Law of Large Numbers and stochastic differential equations provide mathematical foundations that explain how randomness, when observed at a sufficiently large scale, gives rise to structured and predictable behaviors.

Moreover, our findings align with existing theoretical frameworks, such as self-organized criticality, which describes how systems naturally evolve toward critical states through stochastic fluctuations. Additionally, our discussion extends the implications of decoherence in quantum mechanics, linking it to classical stability via probabilistic interactions with the environment. These perspectives highlight that stochasticity does not equate to disorder but instead functions as a key organizing principle in nature.

Understanding this perspective has profound implications for multiple domains. For instance, in artificial intelligence, leveraging stochastic processes can enhance machine learning models, improving robustness and adaptability. In climate science, recognizing the role of stochastic feedback loops can refine predictions of environmental fluctuations. Similarly, in financial markets, acknowledging the non-deterministic nature of economic systems allows for better risk assessment and policy formulation.

The next section will explore how these insights compare to classical deterministic models and discuss future research directions aimed at deepening our understanding of stochastic-driven self-organization.

A critical aspect of comparing stochastic and deterministic models is recognizing their complementary roles. While deterministic models excel in describing closed, controlled systems with well-defined initial conditions, stochastic models offer a more accurate representation of real-world complexities where uncertainty, noise, and emergent behavior play a significant role. Chaos theory, for example, reveals how minor perturbations in deterministic systems can lead to unpredictable outcomes, further reinforcing the need for stochastic frameworks to capture long-term behaviors effectively.

In the field of biological systems, deterministic models of genetic inheritance and evolution provide a foundational understanding, but they often fail to account for the variability introduced by genetic drift and epigenetic modifications. Stochastic models, incorporating elements such as probabilistic gene expression and adaptive evolution, bridge this gap by capturing the dynamic interplay between randomness and structured selection pressures.

Similarly, in economic and social sciences, deterministic theories such as classical economic equilibrium models assume rational behavior and perfect information flow. However, real-world markets and social dynamics are influenced by unpredictable events, network effects, and feedback loops, which are best analyzed through stochastic simulations and probabilistic decision-making models. Recognizing the limits of determinism in these contexts allows for more resilient and adaptive policy-making.

Future research should focus on refining hybrid models that integrate stochasticity with deterministic principles. Advances in computational power and data analytics enable more sophisticated simulations that incorporate randomness while maintaining predictive accuracy. Exploring the impact of stochastic feedback mechanisms, threshold effects, and emergent stability will provide deeper insights into how order arises from apparent disorder.

In conclusion, while determinism has historically provided a strong foundation for scientific inquiry, embracing stochasticity as an intrinsic component of complex systems broadens our understanding of natural and artificial processes. Moving forward, interdisciplinary collaborations will be essential in further developing unified theories of self-organization, where stochastic principles continue to play a central role in explaining the structured complexity of our universe.

One of the key directions for future research is the development of more integrated stochastic-deterministic models that can adapt to varying levels of uncertainty. In many natural and artificial systems, the interplay between randomness and order is highly context-dependent, requiring models that can transition seamlessly between deterministic precision and stochastic flexibility.

Additionally, a deeper exploration of stochastic feedback loops and their role in maintaining equilibrium across dynamic systems will further enhance our understanding of self-organized stability. Investigating how such feedback loops operate in biological homeostasis, economic cycles, and ecological resilience will provide valuable insights into the robustness of complex adaptive systems.

Another promising area involves the application of machine learning and artificial intelligence to analyze stochastic patterns. Leveraging AI-driven techniques to identify hidden structures in seemingly random datasets can refine our predictive capabilities in fields as diverse as weather forecasting, epidemiology, and financial modeling. The integration of stochastic modeling with AI algorithms holds great potential for improving real-time decision-making processes.

Finally, interdisciplinary collaboration will be crucial in advancing the practical applications of stochastic principles. By bridging knowledge from physics, biology, economics, and computational sciences, researchers can develop unified frameworks that enhance our ability to model, predict, and optimize the behavior of complex systems.

In summary, this research underscores that stochasticity is not merely a source of uncertainty but a fundamental organizing principle in nature. The challenge ahead lies in refining our theoretical and computational tools to harness the power of randomness in creating structured, adaptive, and resilient systems. As we continue to deepen our understanding, embracing stochastic principles will be key to unlocking new discoveries and innovations in science and technology.

6.0.7. Final Summary and Key Contributions

This paper demonstrates that stochasticity is not a disruptive force but an essential ingredient for the emergence of order across disciplines. From quantum mechanics to socio-economic structures, randomness serves as a mechanism for self-organization, adaptability, and resilience. The integration of theoretical modeling, computational simulations, and interdisciplinary applications provides a unifying perspective on how complexity arises from chaos. Future research should further explore hybrid models that blend stochastic and deterministic elements, paving the way for more accurate predictions and advanced optimization techniques in dynamic systems.

References

- Banzhaf, Wolfgang (2009). “Self-Organizing Systems”. In: Encyclopedia of Complexity and Systems Science. URL: https://www.cs.mun.ca/~banzhaf/papers/sos.pdf.

- Barfoot, Timothy D. and G.M.T. D’Eleuterio (2005). “Stochastic Self-Organization”. In: Complex Systems Journal. URL: http://asrl.utias.utoronto.ca/~tdb/bib/barfoot_cs05b.pdf.

- Black, Fischer and Myron Scholes (1973). “The Pricing of Options and Corporate Liabilities”. In: Journal of Political Economy 81.3, pp. 637–654. [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene F. (1970). “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work”. In: Journal of Finance 25.2, pp. 383–417. [CrossRef]

- Haken, Hermann and Juval Portugali (2016). “Information and Self-Organization”. In: Entropy. URL: https://www.mdpi.com/1099-4300/19/1/18/pdf.

- Heylighen, Francis (2001). “The Science of Self-Organization and Adaptivity”. In: The Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems. URL: https://www.academia. edu/download/3243859/science_of_self_organization.pdf.

- Prigogine, Ilya (1977). “Time, Structure and Fluctuations”. In: Science 201.4358, pp. 777–785. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, Claude E. (1948). “A mathematical theory of communication”. In: Bell System Technical Journal 27.3, pp. 379–423. [CrossRef]

- Yukalov, V.I. and Didier Sornette (2014). “Self-Organization in Complex Systems as Decision Making”. In: Advances in Complex Systems. URL: https: //arxiv.org/pdf/1408.1529.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).