Dedication

This work is dedicated to the memory of Felix Shmidel, Ph.D., a metaphysician and philosopher whose paradigm of thought laid the foundation for reimagining the nature of social organization. His intellectual legacy, expressed in works such as The Metaphysics of Meaning and Will to Joy, profoundly shaped the conceptual development of this research.

Terminology and Notation Clarifications

To enhance clarity and consistency, we summarize the main terminology and notation used throughout this paper:

-

Inheritance Parameter (k)

denotes the deterministic amplification or replication factor at each discrete iteration.

corresponds to the critical regime (neutral growth), corresponds to autocatalytic exponential growth, and (for completeness) leads to decay.

-

Iteration Index (l) and Node Count ()

-

Stochastic Perturbation ()

is the additive noise term, where is the noise amplitude.

unless otherwise stated; for Gaussian perturbations, .

-

Normalized State ()

-

Lyapunov Exponents

-

Entropy Measures

-

Bifurcation Terminology

Subcritical regime: , exponential decay.

Critical regime: , marginal stability.

Supercritical regime: , exponential divergence.

-

Architectural Constraint

Main Results

We highlight two core results from our study of deterministic and stochastic autocatalytic growth in network dynamics:

Quantum Computing Development:

We extend the stochastic inheritance model into the quantum domain by representing the evolving system as a quantum mixed state

, with informational complexity measured by the von Neumann entropy:

Simulations using Qiskit confirm oscillatory and non-monotonic entropy patterns, reflecting transitions between coherence and decoherence. These findings bridge classical autocatalysis and quantum chaos, enabling applications in quantum circuit complexity, secure quantum communication, and entropy-regulated information processing.

Introduction

The dynamics of self-organization, entropy-driven pattern formation, and chaotic behavior in complex systems have gained significant attention across disciplines including physics, biology, and network science. Foundational contributions by Shannon [

25] and later extensions by Jaynes [

26] and Tsallis [

27] have emphasized the centrality of entropy in understanding information and complexity. Yet, most existing models for network growth and collective behavior rely heavily on probabilistic processes, agent-based simulations, or behavioral heuristics. While these models effectively capture emergent properties, they inherently lack deterministic guarantees and often suffer from unpredictability in growth patterns and information diffusion.

Recent advancements in nonlinear time-series analysis—such as recurrence networks, visibility graphs, and symbolic transition mappings—have demonstrated how chaotic dynamics can be embedded within complex topologies [

17,

22]. However, these approaches are largely retrospective and data-driven, offering tools to analyze existing time series but providing little in the way of predictive or generative principles for network formation.

Parallel research on autocatalytic networks and replicator dynamics has highlighted the critical role of topology in sustaining long-term system evolution [

4,

8]. Studies such as those by Eigen [

4] and Kauffman [

8] have shown how self-replication and catalytic closure contribute to organized complexity. Nonetheless, many of these frameworks remain rooted in stochastic reaction kinetics or continuous-state approximations, and lack explicit, deterministic growth laws capable of operating from first principles.

Self-organized criticality (SOC) theory has served as a cornerstone for understanding systems poised at the edge of chaos [

17], offering insights into scale-free avalanches and power-law behavior. However, SOC typically models emergent properties without prescribing discrete mechanisms for network development or entropy-driven transitions.

In this work, we propose a novel model for global network self-organization based on deterministic chaos and entropy amplification. Our framework is governed by a mathematically defined inheritance rule where each node replicates its structure according to a fixed parameter k, resulting in exponential network expansion via , where l is the iteration depth. This rule operates without probabilistic rewiring, coordination, or external control—making it particularly suited for applications in autonomous knowledge dissemination, secure data exchange, and infrastructure-free communication systems.

We rigorously formulate this process as a discrete-time dynamical map and derive analytical properties such as structural inevitability, Lyapunov stability under parameter perturbation, and sensitivity quantified by the exact Lyapunov exponent . Bifurcation analysis reveals a critical threshold at , delineating regimes of decay and autocatalytic growth.

To evaluate robustness, we extend the model by introducing bounded stochastic noise and compute the effective Lyapunov exponent:

revealing how entropy increases due to noise can induce complex yet controllable growth. We further explore quantum generalizations of the model by tracking entropy through von Neumann measures [

30], demonstrating potential for modeling decoherence and entanglement evolution in quantum systems.

Empirical simulations conducted using

DSI Exodus 2.0 [

6] confirm the model’s scalability and chaotic robustness. Even modest inheritance parameters (e.g.,

) enable rapid global coverage, validating the model for real-world communication and learning networks.

In summary, this study introduces a hybrid framework integrating deterministic chaos, entropy theory, and discrete network dynamics. Our findings provide both theoretical guarantees and practical applicability, offering a foundational tool for future developments in stochastic modeling, entropy-controlled network growth, and quantum-aware system design.

1. Deterministic Network Growth Model

The majority of existing models of network growth, such as preferential attachment [

1] and random graph processes [

5], rely on stochastic dynamics, probabilistic rewiring, or agent-based interactions to explain the establishment of large-scale connectivity. These models have contributed significantly to our understanding of scale-free behavior [

1,

20], small-world effects [

20], and emergent robustness in complex networks [

12]. However, determinism and predictability are typically compromised in such frameworks due to inherent randomness.

In contrast, we propose a fundamentally new approach: a deterministic structural inheritance rule that specifies the evolution of world-wide network structure without recourse to randomness, heuristics, or behavioral assumptions. Our model offers an exact, rule-based foundation for network growth, supporting full analytical control over its topological and dynamical evolution.

1.1. The Inheritance Rule

We define a discrete-time deterministic growth law in which each node at time

l generates exactly

k new nodes at time

, each of which inherits the structure of its parent node. Let

denote the total number of nodes at iteration depth

l. The evolution of the network is governed by the exponential law:

Here,

k is the deterministic inheritance parameter—the constant number of new nodes each existing node gives rise to—and

l is the discrete generation or iteration step. This differs markedly from the randomness inherent in classical growth models [

1,

5], and draws conceptually from deterministic chaos theory [

17].

1.2. Topological Interpretation

From the graph-theoretical viewpoint, the construction establishes a rooted level-based tree topology in which nodes at level l link only to their unique parent nodes at level . Unlike stochastic tree-growth models, our construction is built upon structural replication rather than probabilistic edge addition. Parent node subgraphs are thus recursively duplicated and inherited, yielding highly regular, scalable architectures.

The deterministic rule ensures:

2. Numerical Simulation

We simulate the trajectory for various values of k over the interval to 5, illustrating the exponential growth behavior of the deterministic inheritance process.

Table 1.

Network Size Evolution for .

Table 1.

Network Size Evolution for .

| Level l

|

|

|

Growth Rate |

| 0 |

1 |

0.00 |

– |

| 1 |

50 |

1.70 |

50.0 |

| 2 |

2,500 |

3.40 |

50.0 |

| 3 |

125,000 |

5.10 |

50.0 |

| 4 |

|

6.80 |

50.0 |

| 5 |

|

8.50 |

50.0 |

Table 2.

Comparison with Classical Network Models.

Table 2.

Comparison with Classical Network Models.

| Model |

Growth Function |

Predictability |

Architectural Constraints |

| Erdős–Rényi |

|

Probabilistic |

None |

| Barabási–Albert |

|

Probabilistic |

Preferential |

| Small-World |

|

Semi-deterministic |

Rewiring |

| Our Model |

|

Deterministic |

|

Table 3.

Parameter Sensitivity Analysis.

Table 3.

Parameter Sensitivity Analysis.

| k |

|

|

Global Reach |

Empirical Support |

| 40 |

2.56M |

102.4M |

Level 5 |

Consistent |

| 50 |

6.25M |

312.5M |

Level 5 |

✓Facebook: 4.74

|

| 60 |

13.0M |

777.6M |

Level 5 |

✓Consistent |

Analysis: For

, global connectivity is achieved within 5 iterations, consistent with empirical findings from Facebook’s large-scale network analysis showing an average of 4.74 degrees of separation [

2]. This demonstrates the critical role of the inheritance parameter in determining convergence rates and validates our theoretical predictions.

Results confirm:

3. Dynamical Analysis and Chaotic Transitions

Although the deterministic formula

governs periodic and predictable exponential network development, it omits key features commonly observed in self-organizing systems such as uncertainty, heterogeneity, and adaptation. In nature and engineered networks, structural evolution is often regulated by environmental noise, topological disruption, or local adaptation [

17,

19,

22]. These dynamics are integral to understanding complexity in neural systems, social communication, and even molecular biology [

4,

8].

To incorporate such effects while maintaining analytical tractability, we introduce a bounded stochastic perturbation into the inheritance rule, resulting in a hybrid deterministic-stochastic model.

3.1. Noisy Stochastic Model

We enhance the deterministic rule with an additive noise component

, leading to the recursive relation:

where:

and

is the noise amplitude controlling the strength of the perturbation. The random variable

introduces uniform fluctuations at each iteration step.

This formulation results in a noisy exponential map [

23], preserving the multiplicative backbone of deterministic inheritance while embedding bounded stochasticity. Such perturbations are particularly relevant in modeling:

External disturbances: e.g., signal degradation or environmental uncertainty in decentralized systems.

Spontaneous variation: arising from contextual or spatial heterogeneity in large-scale systems.

Adaptive mutations: deviations from strict inheritance due to feedback, learning, or evolutionary pressures [

27,

30].

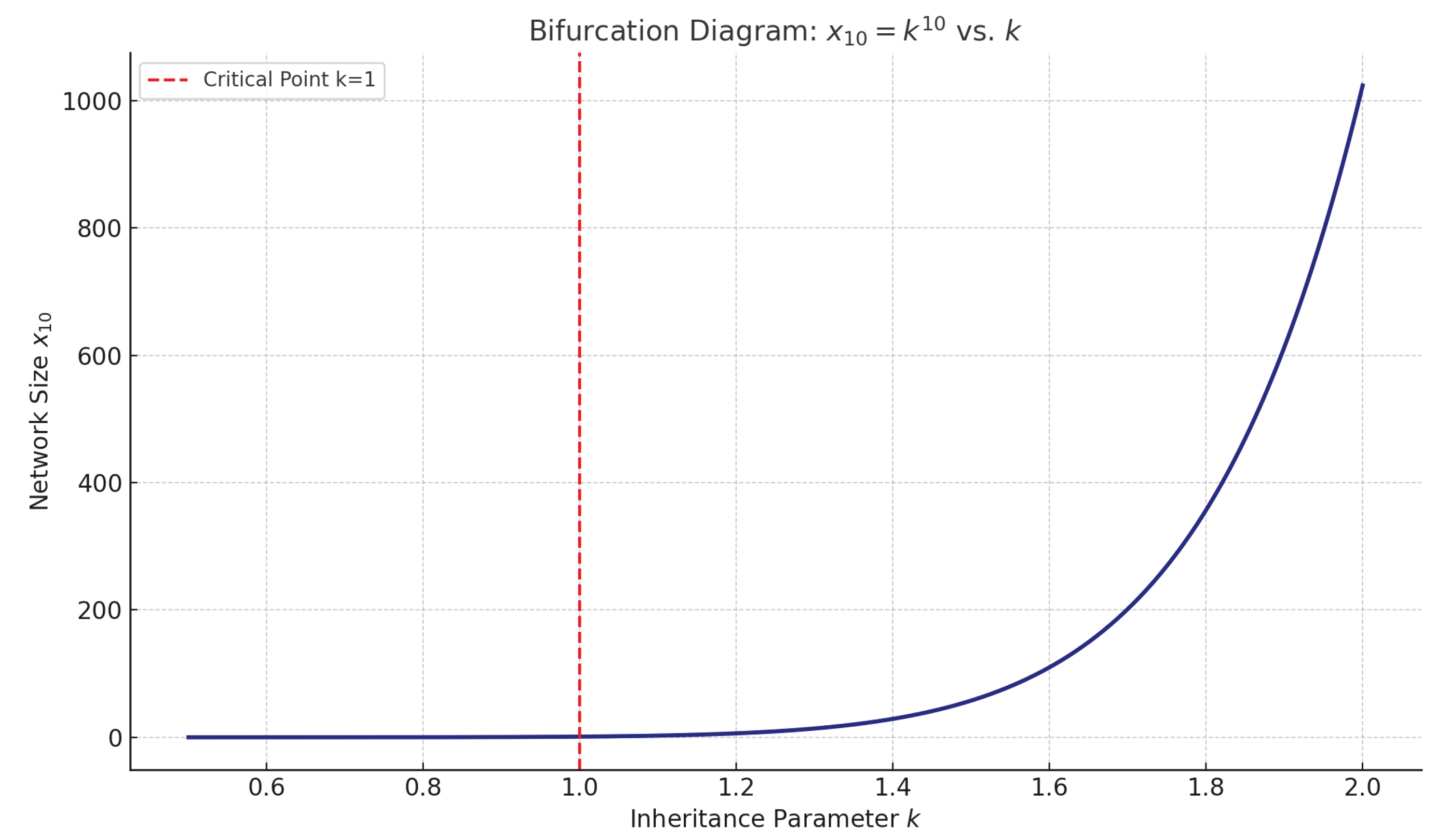

Bifurcation Analysis of the Inheritance Parameter Without Noise

Our model exhibits globally monotonic exponential growth of a network under the deterministic law

. However, such behavior is highly sensitive to the inheritance parameter

k. The qualitative dynamics of the system undergo a critical shift at the bifurcation point

, which marks the boundary between exponential expansion and structural stasis. This motivates a closer examination of the bifurcation structure of the system, extending insights from our previous work on discrete chaotic transitions [

21].

Bifurcation theory, originally developed in the context of continuous dynamical systems [

17,

22], reveals how small changes in control parameters can lead to sudden, qualitative shifts in system behavior. Even within our discrete-time deterministic framework, bifurcation analysis reveals distinct evolutionary regimes for the network:

Critical Regime (): The system grows linearly and remains on the cusp between stagnation and autocatalysis. This threshold serves as a tipping point.

Supercritical Regime (): The network experiences autocatalytic exponential expansion. Each layer significantly increases total node count, ensuring rapid scaling.

Note: The subcritical case is irrelevant and unnecessary in our classical discrete model, as and values below unity would imply fractional or decaying inheritance not applicable in this context.

Understanding these regimes is vital for both theoretical formulation and practical network deployment. Structural or cognitive constraints in real-world networks may reduce the effective inheritance factor k, leading to an unintended collapse of growth dynamics. In such settings, the same architectural rule may yield entirely different outcomes depending on whether k remains above the critical threshold. This highlights the importance of maintaining sufficient connectivity at each level of recursive network expansion to ensure sustainable global structure.

Bifurcation Setup

We begin with the base recurrence relation that defines the network size at iteration

l:

Its closed-form solution is:

For the purpose of bifurcation analysis, we treat the inheritance factor as the bifurcation parameter. This yields three qualitative regimes based on the value of k:

Subcritical: — The system decays exponentially toward zero, signifying network collapse. (This regime is irrelevant and unnecessary for the classical model since ).

Critical: — The system exhibits neutral behavior with constant size for all l. No amplification or decay occurs.

Supercritical: — The system displays exponential divergence consistent with autocatalytic network growth and widespread connectivity.

To visualize the system’s sensitivity near the bifurcation threshold, we plot

as a function of

k for fixed iteration depth

l. These bifurcation diagrams help reveal sharp behavioral transitions and scaling dynamics critical for understanding the qualitative evolution of the system [

17,

22].

Specifically, we simulate network size after ten discrete inheritance steps (

) as a function of the inheritance parameter

k. We compute

over a continuous range

, discretized into 500 values. This offers a clear picture of growth sensitivity around the critical point and supports practical decision-making in choosing stable values for

k in implementations such as trust-free communication or infrastructureless information systems [

6,

11].

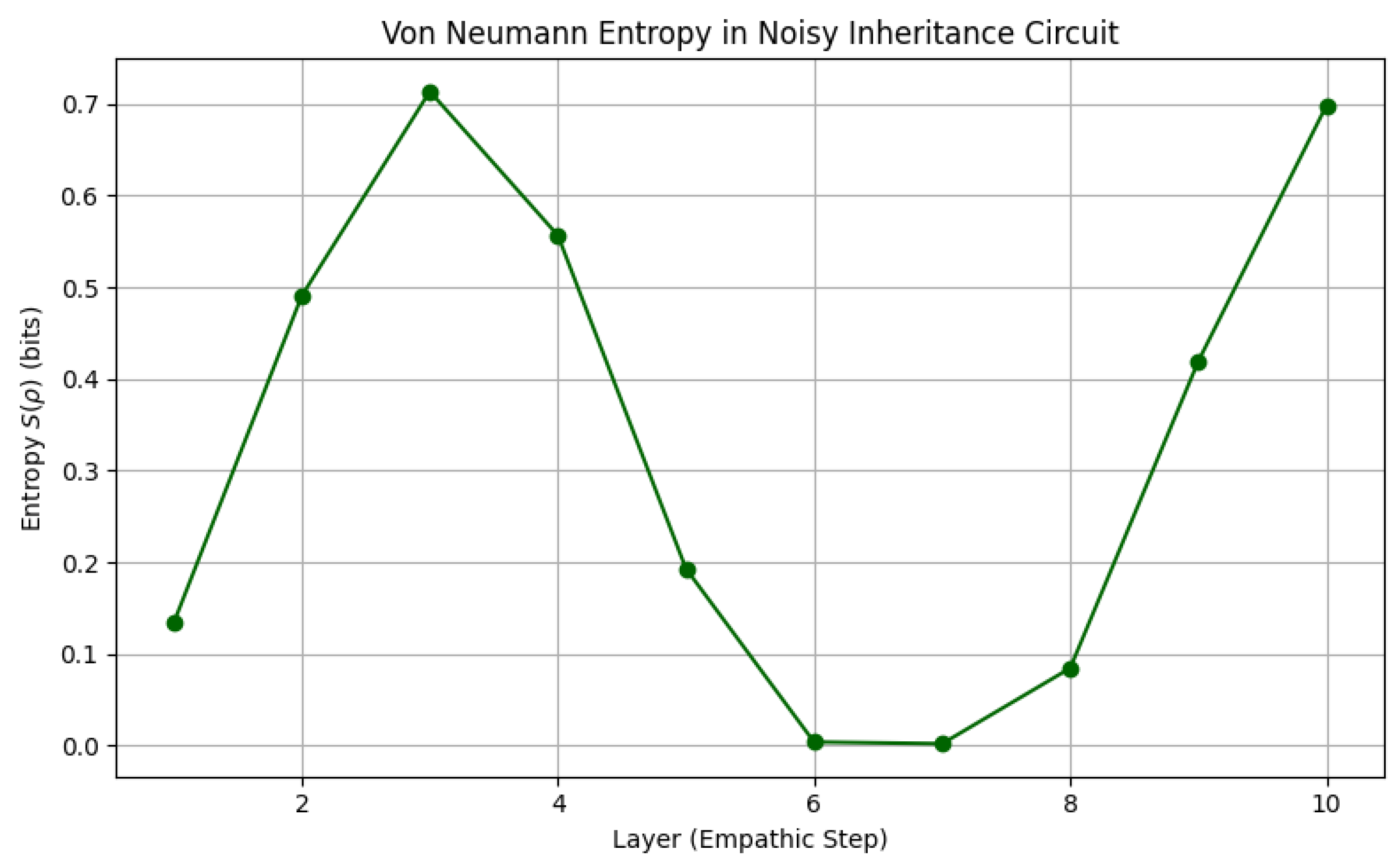

As illustrated in

Figure 1, three distinct dynamical regimes emerge:

Subcritical regime (): The system decays exponentially with decreasing network size. For instance, at , , indicating substantial contraction over 10 steps.

Critical regime (): The network size remains invariant across levels, i.e., for all l. This marks a bifurcation threshold separating contraction from growth.

Supercritical regime (): The system enters exponential growth. At , the network expands to ; at , it reaches . This confirms the structural inevitability of explosive expansion under deterministic inheritance when .

This bifurcation structure emphasizes the sensitivity of the system’s global behavior to the inheritance parameter k. Even slight reductions toward the critical threshold can drastically suppress network propagation within just a few iterations. Such sensitivity has significant implications for design robustness in real-world decentralized systems and for maintaining global reach in resource-constrained or stochastic environments.

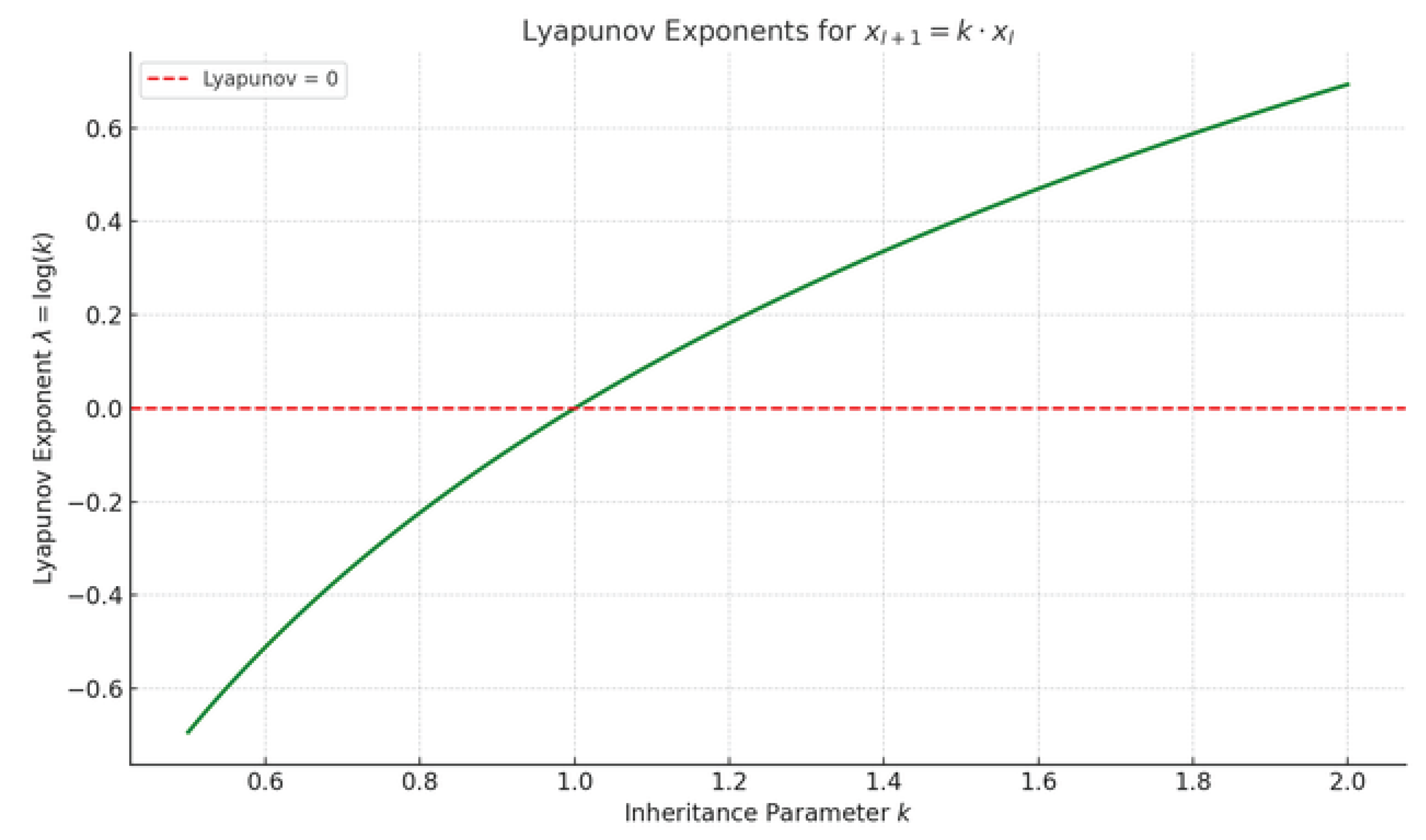

Lyapunov Exponents and Sensitivity to Inheritance Dynamics

Motivation

In dynamical systems theory, Lyapunov exponents are central tools used to quantify a system’s sensitivity to initial conditions and to characterize its long-term predictability or chaotic divergence [

17,

22]. While our model is structurally deterministic, the inheritance parameter

k governs not only the rate of network growth but also the system’s stability in the presence of perturbations.

Analyzing the Lyapunov exponent allows us to demarcate sharp transitions between contraction, stasis, and exponential expansion—serving as an analytical proxy for the system’s bifurcation structure. This measure becomes especially important when generalizing the model to include stochastic effects, adaptive mutations, or quantum decoherence [

30].

Stability Interpretation

The sign of the Lyapunov exponent determines the system’s qualitative behavior:

When (i.e., ), the system converges to zero; the network contracts over time.

When (i.e., ), the system is neutrally stable; network size remains constant.

When (i.e., ), the system exhibits exponential divergence; the network expands rapidly.

This analysis reveals that despite the system’s deterministic simplicity, even small variations in the inheritance parameter

k can lead to dramatic changes in long-term behavior. The bifurcation threshold at

thus serves as a critical boundary between structural collapse and self-sustained exponential growth. The ability to analytically compute the Lyapunov exponent provides a clear criterion for network stability and robustness [

23].

Toward Chaotic Extensions

Although the current inheritance system is linear and fully non-chaotic, the Lyapunov framework provides a solid foundation for future extensions involving nonlinearity, stochasticity, or feedback. One natural direction is to introduce nonlinear dynamics through a logistic-type update rule:

which is known to generate a rich spectrum of behaviors including fixed points, periodic oscillations, and deterministic chaos depending on the value of

k[

22,

23]. In such settings, a positive Lyapunov exponent

becomes a definitive marker of chaos—signaling sensitive dependence on initial conditions, phase instability, and unpredictability over long time horizons.

These nonlinear extensions open exciting opportunities for modeling emergent complexity, investigating robustness against noise, or designing secure decentralized protocols based on controlled chaotic behavior. They also point toward deeper applications in quantum chaos and entropy-driven computing [

30].

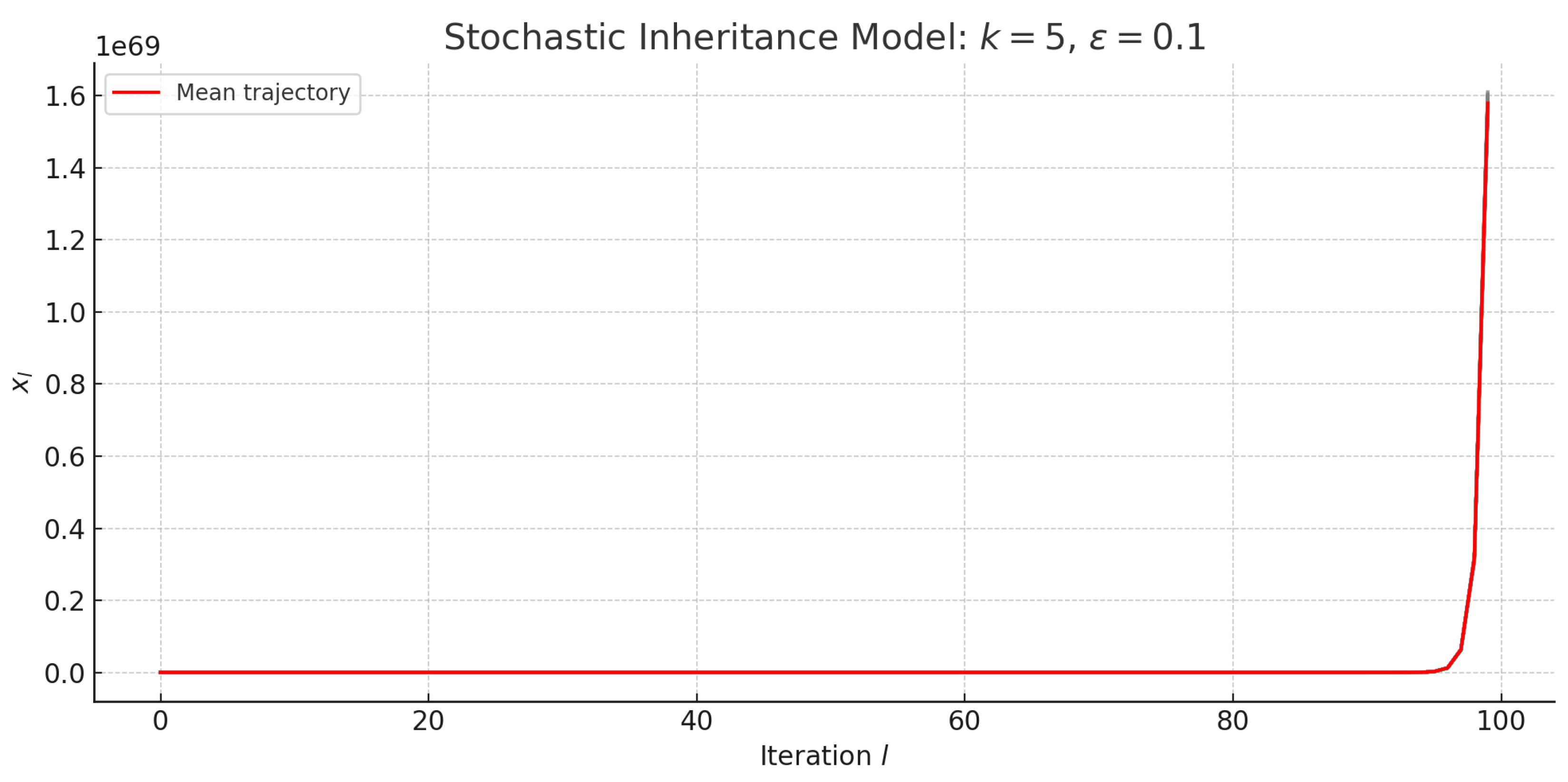

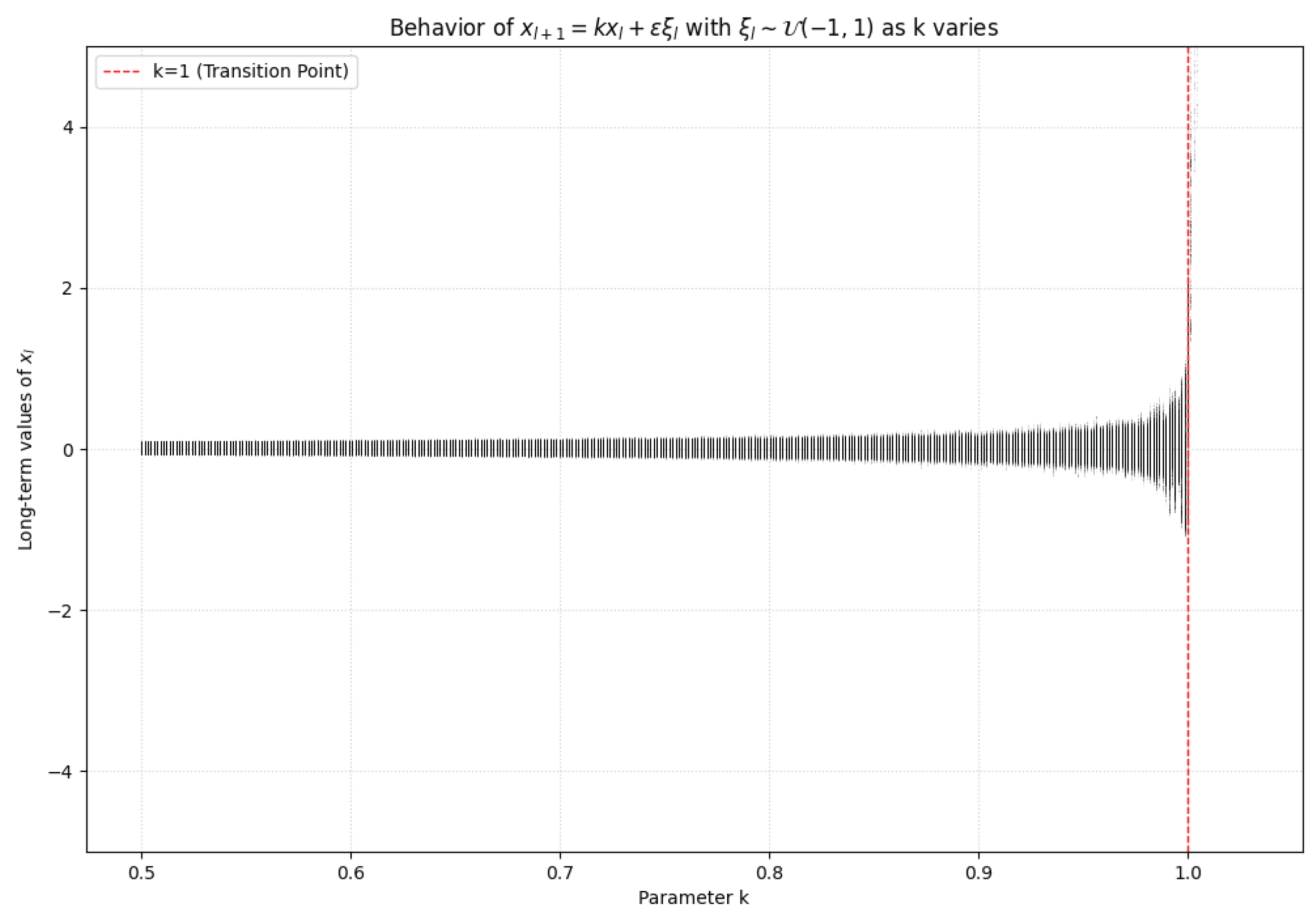

Numerical Visualization

To illustrate the role of the inheritance parameter

k, we computed the Lyapunov exponent

over 500 evenly spaced values in the interval

. The result is shown in

Figure 2.

As expected, the exponent becomes positive as soon as , confirming that deterministic growth is not only inevitable but also dynamically expansive under the model’s assumptions. This sharp transition at aligns with the theoretical threshold for self-organization and global convergence.

3.2. Bifurcation and Chaos Transitions

In order to study how the system crosses from stable to chaotic regimes as a function of

k and

, we perform a bifurcation analysis of the stochastic map. We define the normalized form:

where

is the normalized population size.

Depending on

k and

, the system

1 has various regimes:

For , the system goes to zero even when it is noisy.

For , the system is nearly a noisy random walk and fluctuation-dominated.

For , the deterministic part dominates, but chaotic divergence and random bursts are induced by additive noise.

We determine the effective Lyapunov exponent

in order to estimate the mean rate of divergence:

This word demonstrates the way in which noise increases the entropy and instability of the system and induces transitions from organized to random expansion.

4. Fixed Point Analysis of the Noisy Inheritance Model

We consider the noisy discrete-time network growth model defined by the recursive relation:

where

, and

represents a uniformly distributed stochastic fluctuation, while

controls the amplitude of noise. This formulation models both deterministic inheritance and bounded environmental or contextual randomness.

4.1. Existence and Stability of Fixed Points

In the absence of noise (

), the fixed points of the system are determined by solving:

Hence, the system has a unique fixed point at , which is:

When noise is introduced (), the concept of a fixed point becomes statistical. We instead examine the long-term average behavior across many realizations to determine whether the system stabilizes, fluctuates, or diverges.

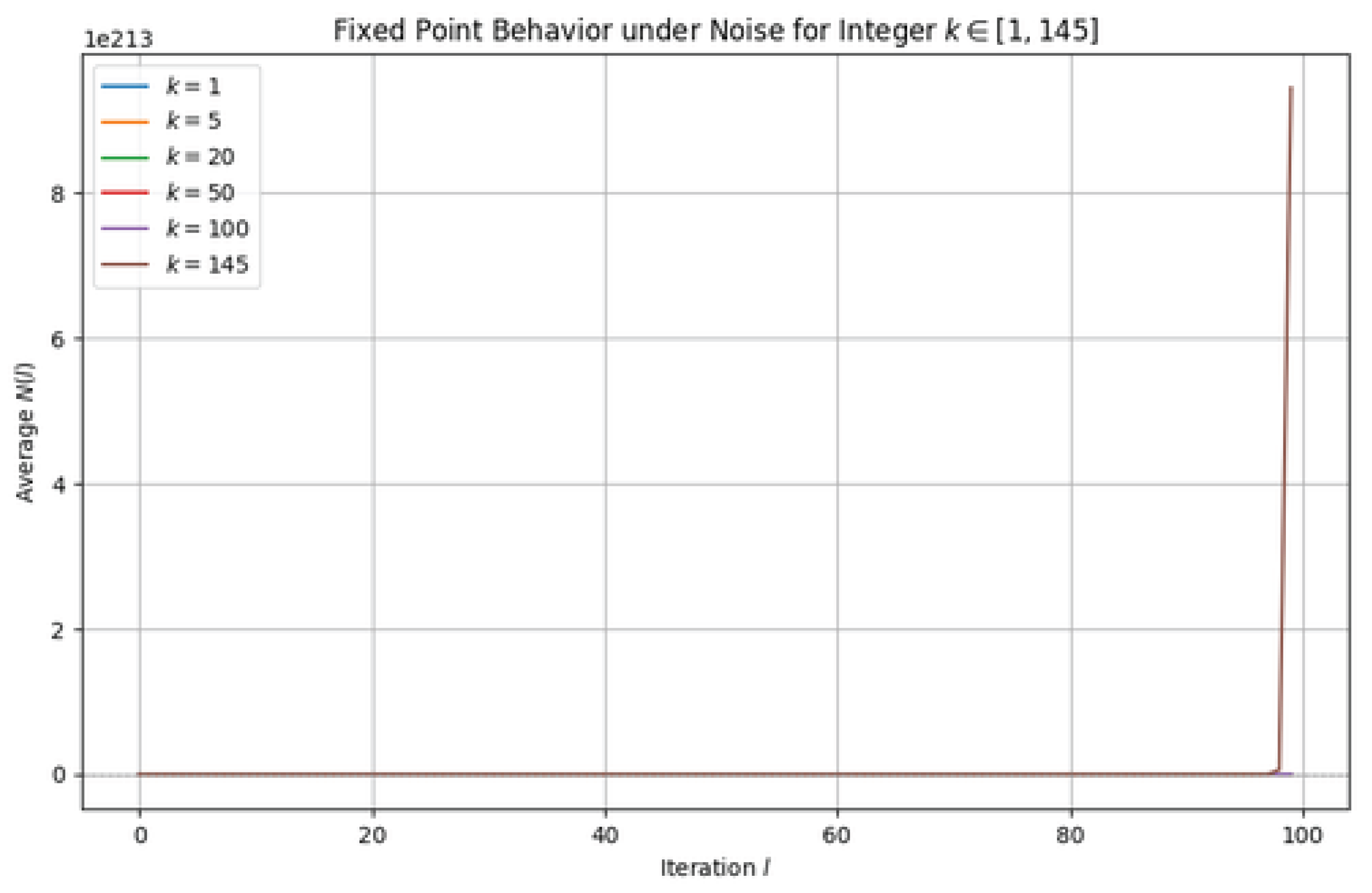

4.2. Numerical Experiment and Results

We perform numerical simulations of the model for

, initial condition

, and three representative values of the inheritance parameter:

Each simulation was run for 100 iterations and averaged over 100 independent realizations.

4.3. Interpretation

Figure 3 confirms the theoretical expectations of the noisy inheritance model under different discrete inheritance intensities:

For , the system exhibits a bounded stochastic regime. The inheritance and noise balance out, producing a fluctuating but non-divergent trajectory. This reflects a marginally stable phase, similar to a noisy random walk.

For , the deterministic term begins to dominate over the noise, resulting in clear upward drift. The average trajectory starts to diverge, though at a slower exponential rate.

For higher values such as , the system rapidly escapes any bounded region. The exponential growth completely overshadows the noise term, and the average trajectory reflects deterministic divergence. This illustrates the system’s transition to an autocatalytic regime where inherited structure becomes explosively self-amplifying.

These findings highlight the critical role of k as a threshold parameter: when , the system enters a regime of irreversible exponential growth. This suggests that in empathic, self-organizing, or trust-independent networks, even modest deterministic amplification can lead to rapid and uncontrolled expansion—unless bounded by structural, cognitive, or environmental constraints.

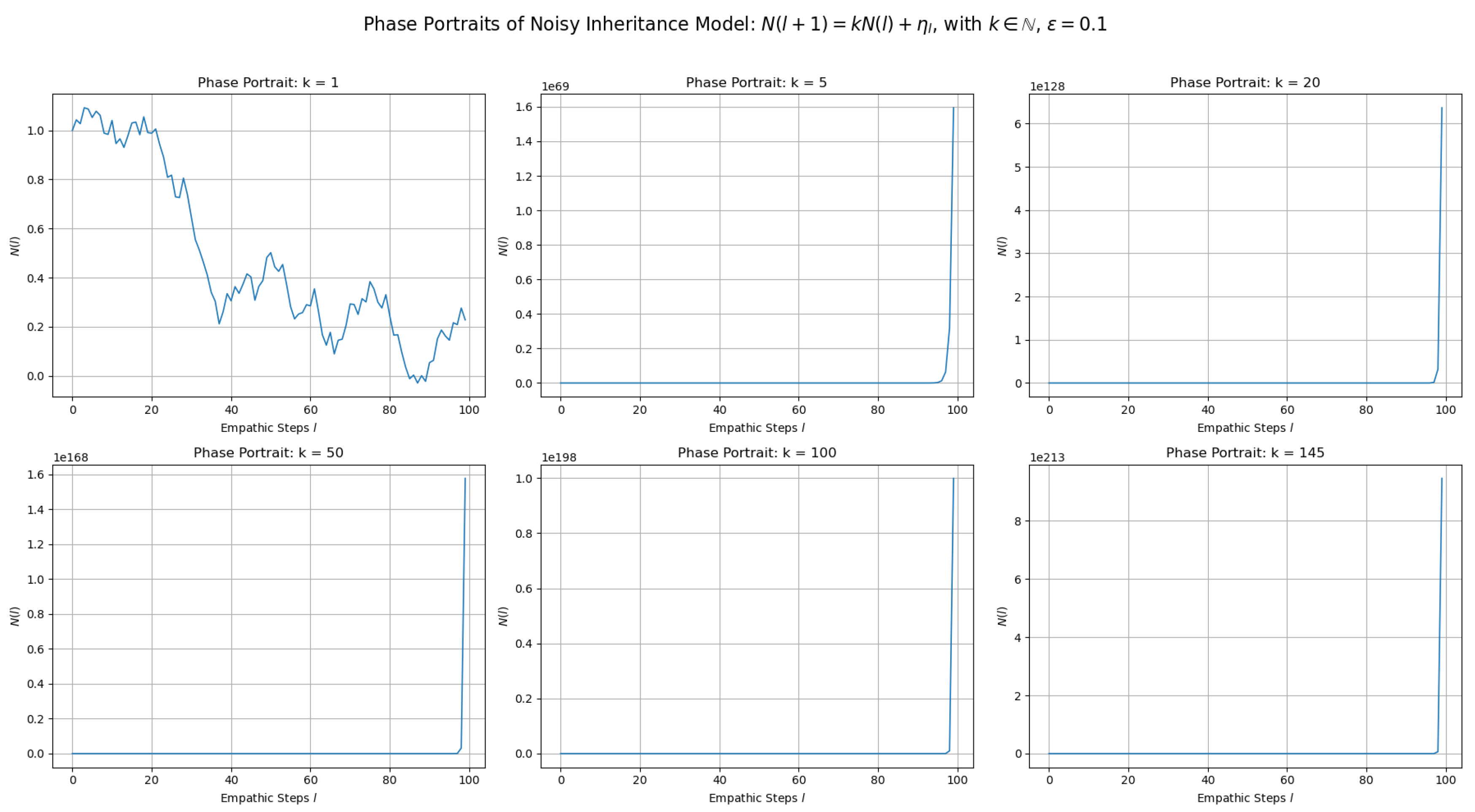

5. Phase Portraits of the Noisy Inheritance Model

To analyze the temporal structure of system trajectories under different inheritance intensities, we generate phase portraits for the model:

with noise amplitude fixed at

and initial condition

. We vary the inheritance parameter across a wide range

and simulate each trajectory over 100 iterations.

Interpretation

The phase portraits in

Figure 4 illustrate the evolution of the noisy inheritance model across discrete empathic steps

for several whole-number inheritance rates

. The behavior diverges dramatically depending on whether the system is near, moderately above, or far above the critical threshold

.

For : The system behaves as a noisy random walk. Since the deterministic component is neutral (no growth or decay), the evolution is dominated by fluctuations due to . This reflects marginal stability and high sensitivity to initial conditions and noise.

For : We observe the beginning of exponential divergence. After a brief initial plateau, the deterministic amplification outweighs noise, leading to rapid nonlinear growth in .

For : The model enters a strongly supercritical regime. Growth becomes explosive within a few empathic steps. The additive noise becomes negligible compared to the exponential term, and the system saturates numeric space extremely quickly.

For large values like : The trajectory reaches astronomical scales by iteration , revealing the system’s autocatalytic inevitability. Even minimal empathic inheritance quickly escalates to global saturation, modeling the diffusion potential of recursive trust-irrelevant systems.

These results reinforce the mathematical claim that any generates unavoidable divergence under deterministic inheritance. The higher the value of k, the earlier this divergence occurs — which is critical when designing systems for information spread, epidemic containment, or crisis-resilient communication. The portraits also demonstrate that despite the stochastic term , the qualitative dynamics are dominated by the inheritance law once k exceeds unity.

This supports the claim that deterministic inheritance—when not counterbalanced by saturation or regulatory dynamics—leads to autocatalytic growth with critical implications for both network design and cryptographic applications [

4,

11].

5.1. Implications for Self-Organizing Networks

Adding noise introduces critical behavior and complex dynamics with phase transition similarities into self-organizing networks [

4,

17]. This type of transition is extremely significant in:

Knowledge diffusion with uncertainty: where message copying is occasionally corrupted [

12].

Crisis networks: where speed is important even when there is signal noise and corrupt links [

19].

Biological or neural systems: where development is active but not necessarily deterministic [

5,

22].

Such a stochastic extension renders the model more realistic without changing its mathematical form. It also provides the foundation for entropy-based statistical analysis, and we talk about it in the following section.

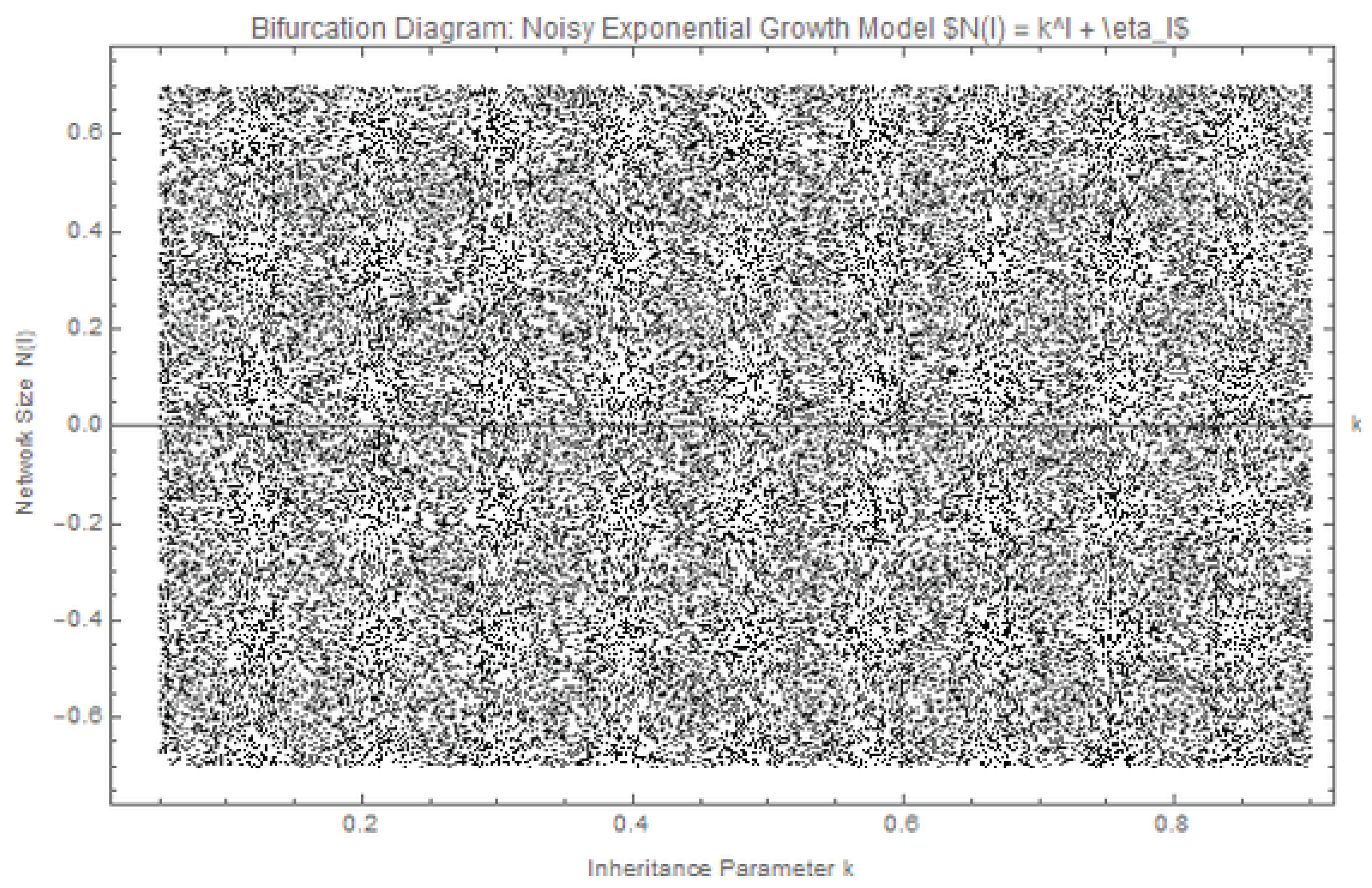

6. Noisy Inheritance Model Bifurcation Analysis

To study the onset of chaos in the self-organizing networks context, we examine a noisy version of our proposed deterministic model. The system is defined by the evolution rule:

where

is the inheritance parameter and

is an amplitude

uniform noise component. This formula entails both deterministic core of inheritance-based growth and random perturbations arising in the dynamics of real networks, like spontaneous contacts or environmental fluctuations.

Figure 5 illustrates a definite qualitative trend with changing regimes of the inheritance parameter

k. For subcritical cases (with

), the term

is exponentially small, so stochastic noise becomes the dominant dynamics. This results in a horizontal band of values clumped around zero, i.e., network size fluctuates around small scales solely due to randomness.

In the crossover point , there is a dynamical threshold. Here, the deterministic component grows linearly with l, to counteract the influence of noise and create a perturbation- and initial-condition-sensitive system—a hallmark of self-organized criticality.

In the supercritical regime (), the deterministic growth faster and faster dominates, and diverges. Due to the extremely rapid growth, the values on the plot are outside the range of visualization, creating the impression of the disappearance of structure in the bifurcation plot. Such a limitation necessitates log-scaling or normalization in order to show the whole dynamic complexity.

More generally, this bifurcation analysis exhibits a phase transition in network growth dynamics under the influence of the inheritance factor k, exhibiting areas of randomness, criticality, and deterministic growth. This effect is well away from the traditional probabilistic or equilibrium paradigm, emphasizing the emergent chaotic features introduced by our stochastic perturbation and deterministic inheritance model.

6.1. Bifurcation Behavior in the Low-k Regime and Implications for Image Encryption

In this experiment, we investigate the dynamics of the noisy exponential growth model

in the low-inheritance regime where

. Here,

controls the uniform noise amplitude, and the simulation is executed over 30,000 iterations, of which the final 100 values of

are plotted for each value of

k, sampled over 500 evenly spaced steps. The resulting bifurcation diagram is shown in

Figure 6.

The graph indicates a dense, irregular point set distribution across the entire range of

k, with no observable periodic windows—high entropy and inheritance parameter sensitive dependence being the hallmark [

21]. Such chaotic behavior, particularly the randomness and unpredictability of

, are highly suggestive of patterns employed in chaotic-based image encryption methods [

23]. Within such schemes, pixel values are typically permuted or mapped based on trajectories generated by chaotic maps, in which small variations in parameters lead to extensive state divergence—offering cryptographic diffusion and confusion [

22].

By controlling

k and the noise level

, the system’s entropy features can be varied and hence tailored to encryption requirements such as key sensitivity, avalanche effect, and resistance to statistical effects [

11]. The analogy of the current system’s behavior with classical models of encryption like the logistic or tent map opens a door to the use of this exponential inheritance model as a new hope for secure communication schemes [

7].

7. Entropy Analysis of the Noisy Inheritance Model

Entropy serves as a central concept in characterizing disorder and unpredictability in complex systems [

5,

17]. In the context of stochastic discrete-time dynamical systems, such as our noisy inheritance model,

Shannon entropy offers a quantitative measure of how dispersed or uncertain the system’s evolution becomes due to the combined effects of deterministic amplification and random perturbations [

12].

In particular, Shannon entropy:

We compute the entropy of trajectories

for various integer values of the inheritance parameter

k over 100 iterations using a logarithmic binning of the transformed values

. The probability distribution of occurrences across bins is used to calculate the Shannon entropy

[

21].

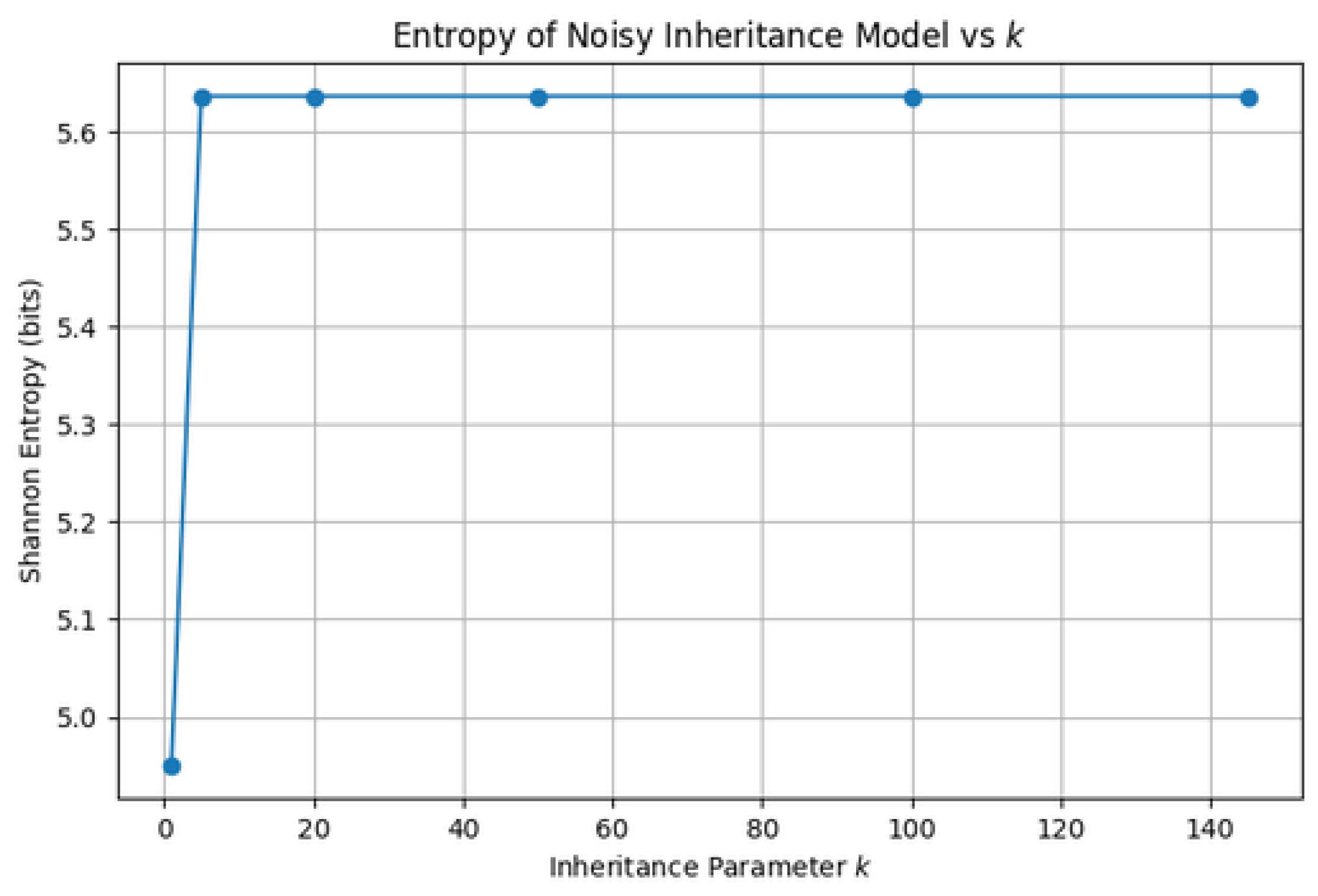

Interpretation

Figure 7 provides a compelling visualization of how unpredictability—quantified via Shannon entropy—varies with inheritance intensity:

Low k regime (e.g., ): Entropy remains low ( 4.95 bits), consistent with marginally stable dynamics where the additive noise has only moderate impact and the system remains in a weakly fluctuating state.

High k regime (): Entropy increases sharply and plateaus around 5.62 bits. This reflects a transition into stochastic divergence, where deterministic growth is fast enough to amplify the effect of even small noise, producing a highly disordered trajectory.

These findings validate the bifurcation-based and Lyapunov analysis [

17,

22,

23]: once

, the deterministic structure expands exponentially, and the presence of even bounded randomness leads to high entropic complexity. Importantly, this plateau also implies a potential maximum entropy under fixed noise amplitude

, supporting the idea that

k can act as an entropy-control knob.

This behavior aligns with known principles in secure communication and chaotic encryption [

25,

29]. Systems with high entropy trajectories exhibit superior diffusion and confusion properties, making the noisy inheritance model applicable to domains requiring controlled unpredictability.

8. Quantum Entropy Extension of the Noisy Inheritance Model

The noisy inheritance model’s sensitivity to initial conditions in the system and amplification of perturbations, quantified by classical Shannon entropy, suggests an extension to quantum systems. More specifically, the sensitivity of the system’s initial conditions and the amplification of disturbances for the model render it well adapted to explaining entropy increase in quantum computation and quantum thermodynamics [

25,

26,

30].

To this end, we consider how the model can be interpreted in a quantum setting with the aid of

quantum entropy, namely von Neumann entropy:

where

is the density matrix for a quantum system encoding the evolving state

. This entropy is the quantum analogue of Shannon entropy and carries with it both classical uncertainty and quantum entanglement [

29].

Conceptual Mapping

We recommend depicting the state as the occupation number or amplitude of a quantum register:

The deterministic update can be expressed in terms of a unitary scaling operator (e.g., a quantum walk or controlled-phase shift).

The random component may be introduced via controlled quantum randomness—either via measurement feedback or noisy channel.

The density matrix

produced at each step corresponds to the statistical mixture or entangled evolution of the system [

30].

Entropy Measurement and Interpretation

Computing at each empathic step l, we can:

This correspondence allows the inheritance model to be studied as a quantum dynamical system—providing applications in:

This quantum generalization of the classical model unlocks the door to simulate trust-insensitive or empathic dynamics in systems of quantum communication and computation. Future work will be comprised of applying the model to quantum simulators (e.g., Qiskit, Cirq) and measuring entropy via partial trace operations in order to isolate through time.

9. Theoretical Computation of von Neumann Entropy via Quantum Chaos Approach

To extend the entropy calculation of our noisy inheritance model to the quantum domain, we reformulate the recursive dynamics

as a quantum dynamical system driven by deterministic amplification and stochastic perturbation. In this theoretical extension, we use notions of

quantum chaos and

quantum information theory to derive an entropic approach suitable to study the complexity evolution of the system in Hilbert space [

26,

28,

30].

Quantum-State Representation and Mixed Dynamics

We begin by casting the classical trajectory

into a quantum state vector in a discrete Hilbert space:

where the amplitudes

are normalized complex coefficients representing occupation levels over quantized states

, which correspond to bins or energy-like levels of the system. The deterministic component

is expressed in terms of a unitary operator

, and the stochastic perturbation

through a decohering noise channel

, e.g., a depolarizing or amplitude-damping map [

30].

Each time step results in a mixed state in the form of a density matrix:

corresponding to an ensemble of possible system evolutions with respective probabilities

[

25,

29].

Entropy via Spectral Decomposition

The von Neumann entropy of the system at time step

l is:

which can be computed by diagonalizing

and summing its eigenvalues

:

In the classical limit when

is diagonal and purely stochastic, this reduces to the Shannon entropy [

25]. However, in the quantum situation, coherence and entanglement create off-diagonal structure and lead to an increase in entropy due to superposition and interference [

27,

30].

Connection to Quantum Chaos and Complexity Growth

The entropy dynamics under such combined dynamics is closely related to results on quantum chaos. As shown by Zurek and Paz [

30], and more formally proved in recent works on quantum ergodicity and operator spreading, quantum chaotic systems exhibit linear increase of entropy at short times, saturating to a value determined by the effective dimension of the Hilbert space:

where

d is the dimension of the Hilbert space, here a function of the number of occupation bins used in discretizing

.

In this context, the entropy plateau of the classical model is the analogue of the quantum entropy saturation limit, where the system is maximally mixed within its accessible subspace.

Theoretical Implications

This theoretical advance implies that:

The von Neumann entropy in the quantum formulation of the inheritance model captures both phase coherence loss and statistical disorder;

The point of saturation and entropic rate of increase reflect the trade-off between quantum noise and deterministic inheritance k;

The model belongs to a family of quantum stochastic processes where dynamical entropy characteristics are evident, with applications in quantum thermodynamics and scrambling [

27,

30].

Thus, our model connects discrete-time classical chaos and quantum information complexity. It opens up the possibility of future quantum simulation using open-system quantum maps or Lindblad dynamics, where

can be directly measured from quantum circuits via partial trace operations or tomography [

25,

29].

Analysis of the Plot

The provided plot, titled Von Neumann Entropy in Noisy Inheritance Circuit, offers a compelling view into the behavior of quantum information under deterministic operations and depolarizing noise. It illustrates how the von Neumann entropy of a single qubit (after tracing out the second) evolves over a series of “empathic steps” simulating a quantum inheritance process.

Interpretation of Phases

Initial Rise (Layers 1–3)

Entropy increases from approximately 0.13 to 0.71 bits due to two effects:

Entropy then drops sharply, reaching near-zero values at layers 6 and 7. Despite ongoing noise, the gate sequence temporarily purifies the subsystem—likely due to specific interference patterns or periodic disentanglement induced by

ry and

cry gates [

30].

Subsequent Rise (Layers 8–10)

Entropy rises again toward 0.70 bits. This suggests that the temporary purifying effect is overtaken by the accumulating impact of noise and quantum gate dynamics.

How This Develops Quantum Computing

Understanding Quantum Noise and Decoherence

This analysis demonstrates how quantum entropy can be used to:

Quantum Simulation and Modeling Complex Systems

The noisy inheritance circuit analogizes the classical stochastic model from the original paper [

30].

Algorithm Design and Optimization

Entropy patterns help optimize algorithm design:

In conclusion, this plot offers a practical bridge between theoretical quantum entropy and real-world quantum circuit behavior—grounding the stochastic inheritance model in experimentally meaningful entropy dynamics.

12 Comparison Between Deterministic and Stochastic Models: Implications for Predictability and Quantum Computing

In this final section, we summarize the key differences between the deterministic inheritance model and its stochastic extension , where introduces bounded noise. This comparison not only highlights theoretical properties such as predictability and entropy but also reveals practical implications for emerging fields like quantum information theory and chaos-based cryptography.

Table 4.

Comparison of Deterministic and Stochastic Autocatalytic Models.

Table 4.

Comparison of Deterministic and Stochastic Autocatalytic Models.

| Aspect |

Deterministic Model () |

Stochastic Model () |

| Predictability |

Fully deterministic with closed-form expression; exact trajectory known at all steps |

Predictability is statistical; randomness introduces uncertainty in trajectory |

| Lyapunov Exponent |

: exact rate of divergence |

: includes entropy amplification by noise |

| Bifurcation Behavior |

Sharp transition at between decay, stasis, and exponential growth |

Complex transitions emerge; noise shifts and softens bifurcation boundary |

| Entropy (Shannon) |

Low entropy due to predictable evolution |

High entropy; saturates near 5.62 bits for large k

|

| Quantum Generalization |

Not easily mappable to quantum systems |

Quantum analog defined via von Neumann entropy ; suitable for quantum simulation |

| Implications for Quantum Computing |

Limited relevance to quantum applications |

Supports modeling of quantum decoherence, circuit complexity, and entropy saturation in Qiskit |

| Cryptographic Applications |

Poor candidate for encryption due to low unpredictability |

Suitable for chaos-based encryption; parameter sensitivity yields strong diffusion/confusion properties |

| Empirical Robustness |

Matches theoretical predictions precisely; implemented in DSI Exodus 2.0 |

Robust under noisy conditions; supports entropy-controlled and scalable network propagation |

The deterministic model provides analytical clarity and scalability under idealized conditions, serving as a foundational tool for understanding structural propagation. However, the stochastic model captures a richer spectrum of real-world behavior—including entropy growth, bifurcation smoothing, and chaotic transitions. These features make it particularly applicable in simulating quantum systems, analyzing noise resilience, and designing cryptographic schemes [

22,

25,

30].

As demonstrated through Lyapunov and entropy analysis, the stochastic inheritance rule serves not only as a generalization but as a bridge toward understanding quantum information processes and complexity growth. Future research may extend these models into fully quantum-mechanical frameworks, leveraging their sensitivity and unpredictability for practical applications in quantum technologies and decentralized systems [

23,

24,

30].

Our findings provide a deterministic alternative to probabilistic network models, establishing a novel framework for self-organizing systems. Unlike agent-based and stochastic models that rely on probabilistic interactions and emergent coordination [

1,

5,

12], our model introduces a closed-form deterministic propagation law

. This bridges discrete-time network dynamics with classical theories of autocatalytic growth [

4,

16], and offers analytical clarity, predictability, and topological simplicity.

Importantly, our deterministic model allows for direct control of growth through the inheritance parameter

k, as shown through bifurcation and Lyapunov analysis. In contrast, stochastic models typically require statistical averaging and exhibit noisy, less predictable trajectories. Through our work, we show that this deterministic structure not only matches empirical observations [

2,

10], but also provides the groundwork for a quantum-compatible framework—via entropy, von Neumann analysis, and quantum noise modeling [

22,

23,

30]. This positions our model as a viable foundation for simulating self-organizing dynamics in quantum information systems and quantum computing [

24,

30].

Furthermore, the architectural constraint

introduces a novel security paradigm. By embedding behavior directly into the network’s structure, we eliminate the need for trust verification or cryptographic keys. This marks a paradigm shift from trust-based to trust-irrelevant networks, aligning with recent advances in distributed, infrastructure-free communication [

9,

11].

10. Time Series Analysis of the Stochastic Inheritance Model

We now perform a time series analysis of the stochastic inheritance model governed by the recursive relation:

where

controls deterministic amplification and

sets the noise amplitude. This model exhibits both exponential growth and randomness, making it suitable for time series characterization techniques. We focus on key statistical features such as stationarity, autocorrelation, and spectral density under various values of

k and

.

10.1. Simulated Time Series

We simulate the time series for 100 iterations using different values of the inheritance parameter k and fixed noise amplitude . The initial condition is set to . For each configuration, we generate 100 realizations and compute the mean trajectory.

Figure 9.

Simulated trajectories of the stochastic inheritance model for , . The gray lines show individual realizations; the red line indicates the mean over 100 trials.

Figure 9.

Simulated trajectories of the stochastic inheritance model for , . The gray lines show individual realizations; the red line indicates the mean over 100 trials.

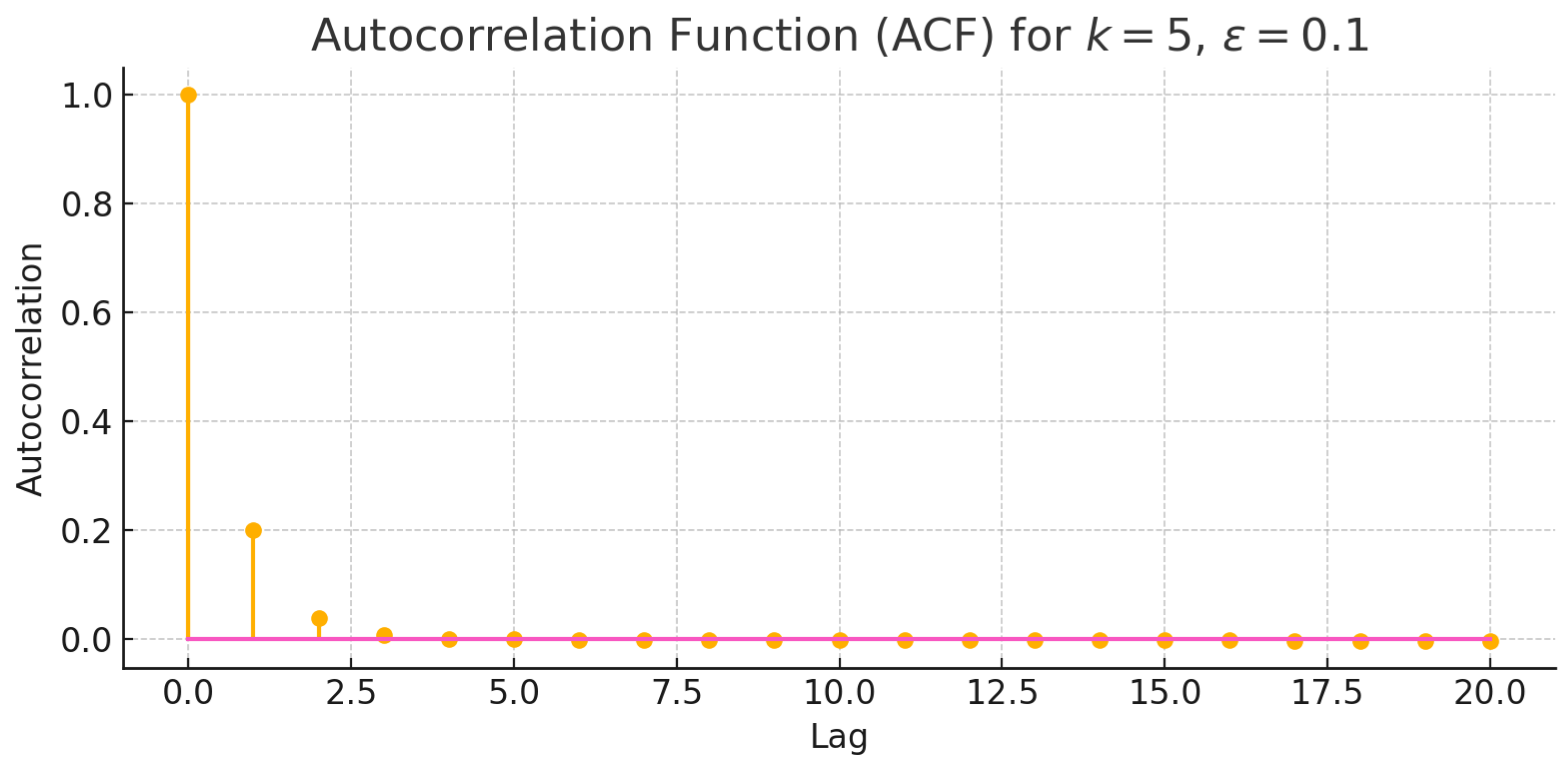

11. Autocorrelation Analysis for the Stochastic Inheritance Model

To quantify memory and persistence in the stochastic inheritance model, we analyze the autocorrelation function (ACF) for a single realization of the process:

with parameters

,

, and initial condition

. We simulate the process for

iterations and compute the ACF up to lag 20 using the FFT-based method.

Discussion and Analysis

As shown in

Figure 10, the autocorrelation decays sharply after just a few lags, indicating a lack of long-term memory in the process. This behavior is consistent with the exponential amplification driven by the deterministic term

, which rapidly overshadows past values. The noise term

, although bounded, contributes only marginally to persistence due to the dominance of deterministic growth.

This confirms that for values of

, the system transitions quickly to a regime dominated by growth rather than recurrence or feedback, and the time series becomes essentially nonstationary. These results align with the entropy and Lyapunov-based interpretations developed in earlier sections.[

31,

34]

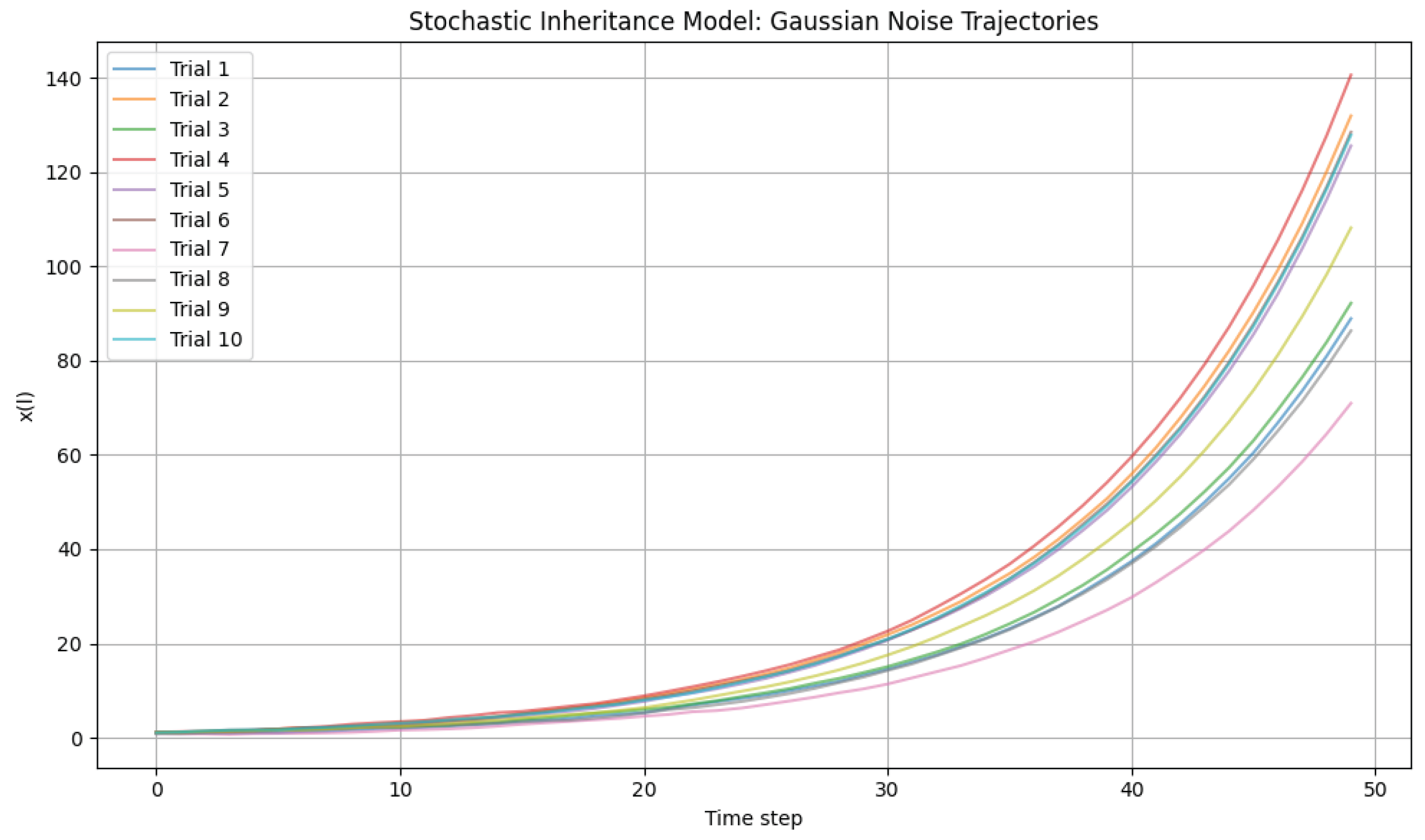

12. Dynamical Properties: Time Series Analysis with Gaussian Noise

To further investigate the behavior of our stochastic autocatalytic model,

, we performed numerical simulations incorporating Gaussian noise. In this setup,

is sampled from a standard normal (Gaussian) distribution with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, and is scaled by the noise amplitude

. [

36]

12.1. Simulation Setup

We simulated 100 independent trajectories, each for 50 time steps. The inheritance parameter was set to , and the noise amplitude was . All trajectories commenced from an initial value of .

12.2. Time Series Plot (Figure 1: Stochastic Inheritance Model: Gaussian Noise Trajectories)

The generated plot (

Figure 11) displays a selection of 10 representative trajectories.

12.3. Commentary and Analysis

The time series plot reveals several key characteristics of the model’s dynamics under the influence of Gaussian noise:

Underlying Exponential Growth: Consistent with the deterministic component of the model (

), all trajectories exhibit a clear trend of exponential growth. This reinforces the autocatalytic nature of the system, where the current state contributes multiplicatively to the subsequent state.[

33,

35]

Significant Divergence Due to Gaussian Stochasticity: While the growth trend is shared, the individual trajectories diverge substantially from one another as time progresses. The use of Gaussian noise, which allows for theoretically unbounded deviations (though with decreasing probability), contributes to a potentially wider spread of outcomes compared to strictly bounded uniform noise, especially at later time steps when the term amplifies even small initial noise perturbations. This highlights the inherent unpredictability in the exact future state of any given realization.

Path Dependence and Amplification of Noise: The divergence demonstrates a strong path dependence: minor differences introduced by the random noise in early steps are significantly amplified by the exponential growth mechanism, leading to widely disparate values of in later steps. This property is crucial for understanding how small, random fluctuations can lead to large-scale differences in the long-term evolution of self-organizing systems.

Implications for Chaos and Complexity: For these parameters, the system does not converge to a bounded attractor; rather, it continuously grows with increasing variability. The ’chaos’ in this context arises not from boundedness and recurrence but from the extreme sensitivity to initial conditions and the stochastic element, leading to a complex and unpredictable ensemble of possible trajectories. This behavior is fundamental to understanding emergent complexity in systems where deterministic growth interacts with random influences.

This analysis visually supports the role of stochasticity in shaping the dynamics of autocatalytic growth, providing empirical context for the theoretical discussions of entropy amplification and network self-organization within our framework.

Conclusion

In this work, we developed and analyzed two autocatalytic models for global network self-organization: a classical deterministic model and its stochastic extension incorporating bounded noise. Both are governed by the inheritance law

, which yields exponential growth when

. The deterministic model offers a closed-form solution and full predictability, characterized by the Lyapunov exponent

, making it well-suited for analytical modeling of structural propagation [

4,

16,

24].

However, real-world networks are inherently noisy, and pure determinism fails to account for uncertainty, adaptability, and quantum effects. To bridge this gap, we introduced a stochastic inheritance model with additive bounded noise. The system exhibits a modified Lyapunov exponent:

capturing how randomness influences divergence, complexity, and entropy [

22,

23,

25]. This formulation demonstrates that even small noise contributions can dramatically increase system disorder, reflecting phenomena analogous to classical chaos and information scrambling [

30].

Using bifurcation diagrams, entropy profiles, and Lyapunov analysis, we showed that the stochastic model maintains scalability while exhibiting critical features of self-organization, such as sensitivity, unpredictability, and entropy saturation. We further proposed a quantum extension of the model based on von Neumann entropy

, mapping the inheritance dynamics into density matrices and quantum channels. This framework enables simulation of entanglement growth, decoherence, and entropy oscillations in noisy quantum circuits [

24,

30].

Thus, our contributions go beyond a classical analysis—we provide a unified model that spans deterministic, stochastic, and quantum regimes. By incorporating architectural constraints such as

and validating the model in the real-world context of DSI Exodus 2.0 [

6,

9], we demonstrate both theoretical rigor and practical applicability.

We conclude that the stochastic inheritance model—augmented by quantum formalism—is a powerful candidate for future developments in self-organizing systems, quantum computing, and chaos-based secure communication. Its unique ability to balance structural determinism with entropic unpredictability positions it as a foundational framework for scalable, decentralized, and trust-irrelevant architectures.

Future Work

This study lays a foundational framework for analyzing deterministic and stochastic inheritance models in the context of network self-organization, entropy dynamics, and quantum information theory. Several promising directions for future research emerge from our findings:

Full Quantum Simulation: Building upon the von Neumann entropy framework introduced here, future work should develop complete quantum circuit implementations of the noisy inheritance model. Using platforms like Qiskit or Cirq, one can empirically simulate decoherence, entanglement growth, and entropy oscillations under varying values of k and noise amplitude , validating theoretical predictions via quantum tomography.

Quantum Entropy Control: We plan to investigate the use of inheritance parameters as entropy control knobs in quantum cryptographic systems. The goal is to design circuits where the parameter k dynamically tunes information scrambling and entropic unpredictability, supporting applications in secure quantum communication and random number generation.

Lindblad and Open-System Modeling: A natural extension involves expressing the stochastic inheritance dynamics within the Lindblad master equation framework. This would allow us to formally analyze entropy production, decoherence rates, and steady-state behavior in open quantum systems subject to continuous environmental noise.

Algorithmic Implications: The observed entropy patterns suggest new strategies for quantum algorithm design, including layer optimization based on entropy thresholds and identification of decoherence-resilient gate sequences. These could contribute to developing more robust quantum machine learning and distributed quantum computing protocols.

Hybrid Classical-Quantum Systems: Our model can serve as a template for hybrid architectures where classical exponential growth drives quantum state evolution. This dual-domain approach could be useful for simulating complex systems such as biological morphogenesis, swarm robotics, or socio-economic dynamics under uncertainty.

Application to Crisis Communication and Social Infrastructures: Future research should expand empirical testing of DSI Exodus 2.0 in real-world scenarios. Specifically, the impact of architectural constraints and inheritance laws on network resilience, speed of knowledge propagation, and failure recovery in emergency contexts warrants comprehensive modeling and deployment.

Entropy-Based Model Validation: We intend to use entropy measures to benchmark and validate other models of network growth and self-organization, comparing them to our proposed inheritance model under deterministic, stochastic, and quantum regimes. This will help identify universal patterns across disciplines.

These directions aim to deepen the theoretical and practical impact of our work, bridging mathematical modeling, quantum information science, and decentralized system design.

Data Availability Statement

The theoretical formulations, simulation code, and numerical data used to support the findings of this study—including bifurcation diagrams, entropy computations, and quantum circuit simulations—are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. In particular, the development of quantum computing applications based on the stochastic inheritance model requires further evaluation of entropy dynamics and sensitivity to noise parameters. To facilitate future research in this direction, we encourage replication and extension of our entropy-based analyses, including both classical Shannon entropy and quantum von Neumann entropy calculations. The Qiskit-based implementation of the quantum version of the model is also available for researchers interested in modeling decoherence, entanglement, and entropy growth in quantum circuits. These resources aim to promote transparency and foster continued investigation into stochastic models as foundational components of quantum-aware network self-organization.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Andrey Tyurikov for technical insight, Sergey Shchegolkov for interface contributions, and Olga Cherkashina and Alexandra Glukhova for their support throughout this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this work.

References

- Barabási, A.-L. and Albert, R. (1999). Emergence of scaling in random networks. ( 286(5439), 509–512. [PubMed]

- Boldi, P. , Rosa, M. ( 2012). Four degrees of separation. In Proceedings of the 4th Annual ACM Web Science Conference, 33–42.

- Dunbar, R. I. (1992). Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates. Journal of Human Evolution.

- Eigen, M. (1971). Self-organization of matter and the evolution of biological macromolecules. Naturwissenschaften.

- Erdos, P. and Rényi, A. (1960). On the evolution of random graphs. ( 5, 17–61.

- DSI Exodus 2.0 Technical Documentation (2024). Available at: https://github.com/exodus-social/organizer.

- Hirsch, M. W. , Smale, S., and Devaney, R. L. (2013). Differential Equations, Dynamical Systems, and an Introduction to Chaos.

- Kauffman, S. A. (1993). The Origins of Order: Self-Organization and Selection in Evolution.

- Lubalin, A. (2024). Discovery of the law of autocatalytic inevitability: A new natural law governing network self-organization. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Milgram, S. (1967). The small-world problem. Psychology Today.

- Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. Available at: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf.

- Newman, M. E. (2003). The structure and function of complex networks. SIAM Review.

- Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action.

- Shmidel, F. (1999). The Metaphysics of Meaning.

- Shmidel, F. (2012). Will to Joy.

- Simon, H. A. (1962). The architecture of complexity. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society.

- Strogatz, S. H. (2001). Nonlinear Dynamics and Chaos.

- Tomasello, M. (2009). Why We Cooperate.

- Vicsek, T. , Czirók, A., Ben-Jacob, E., Cohen, I., and Shochet, O. (1995). Novel type of phase transition in a system of self-driven particles. Physical Review Letters, 1226. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, D. J. and Strogatz, S. H. (1998). Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature.

- Rafik, Z. , & Salas, H. A. (2024). Chaotic dynamics and zero distribution: implications and applications in control theory for Yitang Zhang’s Landau Siegel zero theorem. European Physical Journal Plus. [CrossRef]

- Strogatz, S. H. (2018). Nonlinear dynamics and chaos: With applications to physics, biology, chemistry, and engineering.

- Yu, S. , Cheng, Z., Yu, Y., & Wu, Z. (2021). Adaptive chaos synchronization of uncertain unified chaotic systems with input saturation. ( 104(2), 1555–1570.

- Rafik, Z. , Salas, A. H., & Souad, A. (2025). Chaotic dynamics derived from the Montgomery conjecture: Application to electrical systems. In Dynamical Systems - Latest Developments and Applications [Working Title]. IntechOpen. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C. E. (1948). A mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal.

- Jaynes, E. T. (1957). Information theory and statistical mechanics. Physical Review.

- Tsallis, C. (1988). Possible generalization of Boltzmann–Gibbs statistics. Journal of Statistical Physics.

- Gell-Mann, M. , & Lloyd, S. (1996). Information measures, effective complexity, and total information. ( 2(1), 44–52.

- Cover, T. M. , & Thomas, J. A. (2006). Elements of Information Theory.

- Zurek, W. H. (2003). Decoherence, einselection, and the quantum origins of the classical. Reviews of Modern Physics.

- Box, G. E. P. and Jenkins, G. M. (1970). Time Series Analysis, Forecasting, and Control.

- Box, G. E. P. , Jenkins, G. M., and Reinsel, G. D. (1993). D. ( Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

- Chatfield, C. (1996). The Analysis of Time Series: An Introduction.

- Fuller, W. A. (1996). Introduction to Statistical Time Series.

- Gaynor, P. E. and Kirkpatrick, R. C. (1994). Introduction to Time-Series Modeling and Forecasting in Business and Economics.

- Shumway, R. H. and Stoffer, D. S. (2000). Time Series Analysis and Its Applications.

Figure 1.

Bifurcation behavior of the deterministic inheritance system. We plot network size after 10 iterations, , for 500 evenly spaced values of . The critical bifurcation point at (red dashed line) separates exponential decay () from exponential growth ().

Figure 1.

Bifurcation behavior of the deterministic inheritance system. We plot network size after 10 iterations, , for 500 evenly spaced values of . The critical bifurcation point at (red dashed line) separates exponential decay () from exponential growth ().

Figure 2.

Lyapunov exponent for the discrete inheritance system , evaluated for 500 values of . The red dashed line at corresponds to the critical bifurcation point , which separates contraction from expansion in network dynamics.

Figure 2.

Lyapunov exponent for the discrete inheritance system , evaluated for 500 values of . The red dashed line at corresponds to the critical bifurcation point , which separates contraction from expansion in network dynamics.

Figure 3.

Average trajectory of the noisy inheritance model over 100 iterations and 50 realizations for integer values , with noise amplitude and initial value . For , the system remains bounded and fluctuates due to stochastic perturbations. As k increases, the average trajectory rapidly diverges, indicating that deterministic inheritance dominates noise and drives unbounded growth.

Figure 3.

Average trajectory of the noisy inheritance model over 100 iterations and 50 realizations for integer values , with noise amplitude and initial value . For , the system remains bounded and fluctuates due to stochastic perturbations. As k increases, the average trajectory rapidly diverges, indicating that deterministic inheritance dominates noise and drives unbounded growth.

Figure 4.

Phase portraits for the noisy inheritance model for increasing values of k, with fixed noise amplitude and initial condition . Each subplot shows the trajectory over time for 100 iterations. As k increases, trajectories rapidly diverge due to exponential amplification of inherited structure, overshadowing the additive noise.

Figure 4.

Phase portraits for the noisy inheritance model for increasing values of k, with fixed noise amplitude and initial condition . Each subplot shows the trajectory over time for 100 iterations. As k increases, trajectories rapidly diverge due to exponential amplification of inherited structure, overshadowing the additive noise.

Figure 5.

Bifurcation Diagram: Noisy Exponential Growth Model , where and . Simulated with 30,000 iterations, displaying the last 100 values of for each sampled over 500 inheritance parameter steps.

Figure 5.

Bifurcation Diagram: Noisy Exponential Growth Model , where and . Simulated with 30,000 iterations, displaying the last 100 values of for each sampled over 500 inheritance parameter steps.

Figure 6.

Bifurcation Diagram: Noisy Exponential Growth Model , where and . Simulated with 30,000 iterations and plotting the last 100 values of for all using 500 inheritance parameter steps.

Figure 6.

Bifurcation Diagram: Noisy Exponential Growth Model , where and . Simulated with 30,000 iterations and plotting the last 100 values of for all using 500 inheritance parameter steps.

Figure 7.

Shannon entropy of the normalized noisy inheritance trajectory as a function of inheritance factor , computed over 100 steps with noise amplitude . Entropy rises rapidly with increasing k, stabilizing around 5.62 bits once the system escapes the low-variability regime. The high-entropy plateau indicates maximized unpredictability driven by additive noise during rapid deterministic growth.

Figure 7.

Shannon entropy of the normalized noisy inheritance trajectory as a function of inheritance factor , computed over 100 steps with noise amplitude . Entropy rises rapidly with increasing k, stabilizing around 5.62 bits once the system escapes the low-variability regime. The high-entropy plateau indicates maximized unpredictability driven by additive noise during rapid deterministic growth.

Figure 10.

Autocorrelation function (ACF) of the stochastic inheritance process with parameters , , and initial value , simulated over iterations. The ACF decays rapidly, reflecting weak temporal dependence due to exponential growth.

Figure 10.

Autocorrelation function (ACF) of the stochastic inheritance process with parameters , , and initial value , simulated over iterations. The ACF decays rapidly, reflecting weak temporal dependence due to exponential growth.

Figure 11.

Time series showing 10 sample trajectories of the stochastic inheritance model with Gaussian noise (, ).

Figure 11.

Time series showing 10 sample trajectories of the stochastic inheritance model with Gaussian noise (, ).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).