1. Introduction

Mulching is a widely used technique in horticulture to increase crop earliness, control weed growth and save water by limiting direct evaporation from the soil [

1]. The most widely used mulching material commercially has been polyethylene (PE), a material that is not biodegradable and leaves a considerable amount of residues: 250 kg/ha of polyethylene of which about 100 kg/ha is left as waste in broccoli cultivation in SE Spain [

2] , the average plastic mulch residue in China is 84 kg/ha in China [

3] and there can be between 89 and 206 fragments/ha left in mulched areas in Germany [

4].

Both material removal from farms and management of these residues incur costs. Moreover, management can be complicated by several extraneous materials (soil and crop residues) that make the material coming from the farms unacceptable to waste management companies [

5,

6]. Indeed, there has been an increasing presence of microplastics in agriculture, of which mulching material is one source [

3,

4]. For these two reasons, the use of degradable materials is becoming more and more attractive and widespread [

1,

2,

5].

Consequently, the use of biodegradable materials in mulch is a measure to be considered as part of strategies to mitigate climate change. The use of biodegradable plastics for mulching has a more favourable life cycle analysis (LCA) profile than PE, with a lower global warming potential and use of non-renewable energy sources (between 25% and 80% lower, respectively) [

7].

Biodegradable plastics can be composed of blends of starch and aliphatic polyesters or of polycaprolactones and other synthetic polymers. These materials are degraded by the combined action of climatic conditions and decomposition by soil micro-organisms [

1,

8]. In addition, biodegradable long fibre papers have been developed specifically for mulching in agriculture, with very good degradability though with some handling problems compared to plastic [

9,

10].

The main barriers to adopting biodegradable mulch materials are the higher price compared to PE and the lack of knowledge about the degradation rate of the material [

11]. The costs of biodegradable materials are in some cases also higher than PE [

1,

5,

12].

The use of plastic mulch in Tenerife is particularly widespread in cucurbit crops (pumpkin, watermelon and melon). The sum of these three crops accounts for 10% of the total area of horticultural crops on the island [

13]. For the last 10 years, the use of open-air semi-fertilisation techniques (tunnels and mulching) in these crops has become the norm in medium-size and large farms on the island. In fact, there is a certain lack of experience in the use of biodegradable materials under Canarian cultivation conditions. This is due, among other reasons, to logistical problems of having to transport the materials from Mainland Spain, with high costs for small quantities.

One of the top priorities for waste management operations in the European Union is preventing and reducing waste generation. In the Canary Islands, where there is not enough infrastructure for waste treatment and with a limited and remote territory, minimising waste generation is very important [

14,

15]. Consequently, an experimental demonstration trial with the materials available on the island of Tenerife in 2021 on a pumpkin crop was conducted to find out how these materials perform in the open-air conditions of the island. It was aimed at disseminating their use among vegetable growers.

2. Materials and Methods

In this trial, the productive behaviour of a squash crop was studied with the four biodegradable mulching materials available on the island of Tenerife in December 2021. Two controls were used: polyethylene was used in the rest of the plot, which corresponds to the most commonly used material on the island; and the second was no mulch. The materials tested and their characteristics are shown in

Table 1.

The experiment was carried out in an outdoor commercial plot of 18,400 m2, at an altitude of 428 m above sea level, located in the municipality of Arico (SE Tenerife). Both the soil and the irrigation water used were within the normal parameters for the area. The previous crop was also pumpkin. Prior to planting, 20 t/ha of goat manure was applied.

The squash cultivar ‘Largo de Nápoles’ (Cucurbita moschata D.) was used. The plants were transplanted on 23 March 2022, with a planting spacing of 1 m between plants and 3 m between rows (3333 plants/ha). A localised irrigation system was used.

The biodegradable materials were placed manually on 22 March 2022 due to the experimental design and to facilitate the logistics of the work for the staff of the collaborating farm. In the rest of the plot, PE was used as mulch material.

In the case of the mulch papers, it was observed that the constant wind in the area lifted the paper until the crop managed to cover the line, so bags with soil were placed on top to avoid the total lifting of the material. This behaviour has also been reported in other similar trials [9,10]. This was not necessary for the biodegradable plastics. In the un-mulched treatment, two manual weeding operations had to be carried out because the spontaneous plant growth was much faster than that of the crop at the beginning. The rest of the cultivation tasks such as irrigation, fertilisation and phytosanitary treatments were the usual ones in the area, with all plants receiving the same agronomic treatment. For irrigation management, there was a pair of electro-tensiometers placed in the PE mulching area.

From 100 days after transplanting (dat) a high number of plants with virus symptoms (ZYMV and CMV) were observed, which also affected the final production, especially with malformations. The trial was terminated on 16 August 2022 (146 dat).

The trial used a randomised block design with three replications and six treatments, corresponding to the different materials. The experimental unit consisted of 1 row 34 m long (102 m2 and 34 plants). The data were checked for normal distribution, and then subjected to analysis of variance and separation of means by the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test, using IBM SPSS Statistics v.28. The parameters controlled were:

Evolution of initial vegetative growth: The number of leaves produced by the main vine of five plants of each experimental unit was determined weekly, from the appearance of the main vine until there was no longer a dominant one

Evolution of fruit production: The total number of fruits produced from each experimental unit was determined weekly, from the appearance of the first fruit to the moment when the first fruit was mature (considered as the moment when the corolla was dry) until the end of the trial

Commercial production: Two commercial harvests were carried out: on 28 July and 11 August. The production of each experimental unit was monitored.

Average fruit weight. The weight of each fruit harvested in the two commercial harvests was determined

-

Costs associated with the mulching: The cost was calculated as the sum of the following aspects.

- ○

Cost of materials. The cost also included transport costs from Mainland Spain to the Canary Islands.

- ○

A cost for 3,666 linear metres (ml) of material per hectare was considered (3,333.3 ml/ha and an additional 10% to anchor the beginning of the line and taking into account losses due to cuts).

- ○

Laying costs for all materials were considered to be similar. Laying time was 15.75 hours/ha.

- ○

The labour cost was 9.64 €/hour.

- ○

Transport costs to the waste management company were calculated using the Canary Islands land freight cost simulator [16] for a 3,500 kg lorry of maximum permissible weight (26.84 €/hour). A time of 1 hour between loading, transport and unloading at the nearest waste management company was calculated, which corresponds to an average figure for the dimensions of an island the size of Tenerife (2,034 km2).

- ○

The waste management costs of the nearest waste management company (41.57 €/t) were applied.

- ○

In the case of the control without mulching, the cost of manual weeding in the crop row was considered.

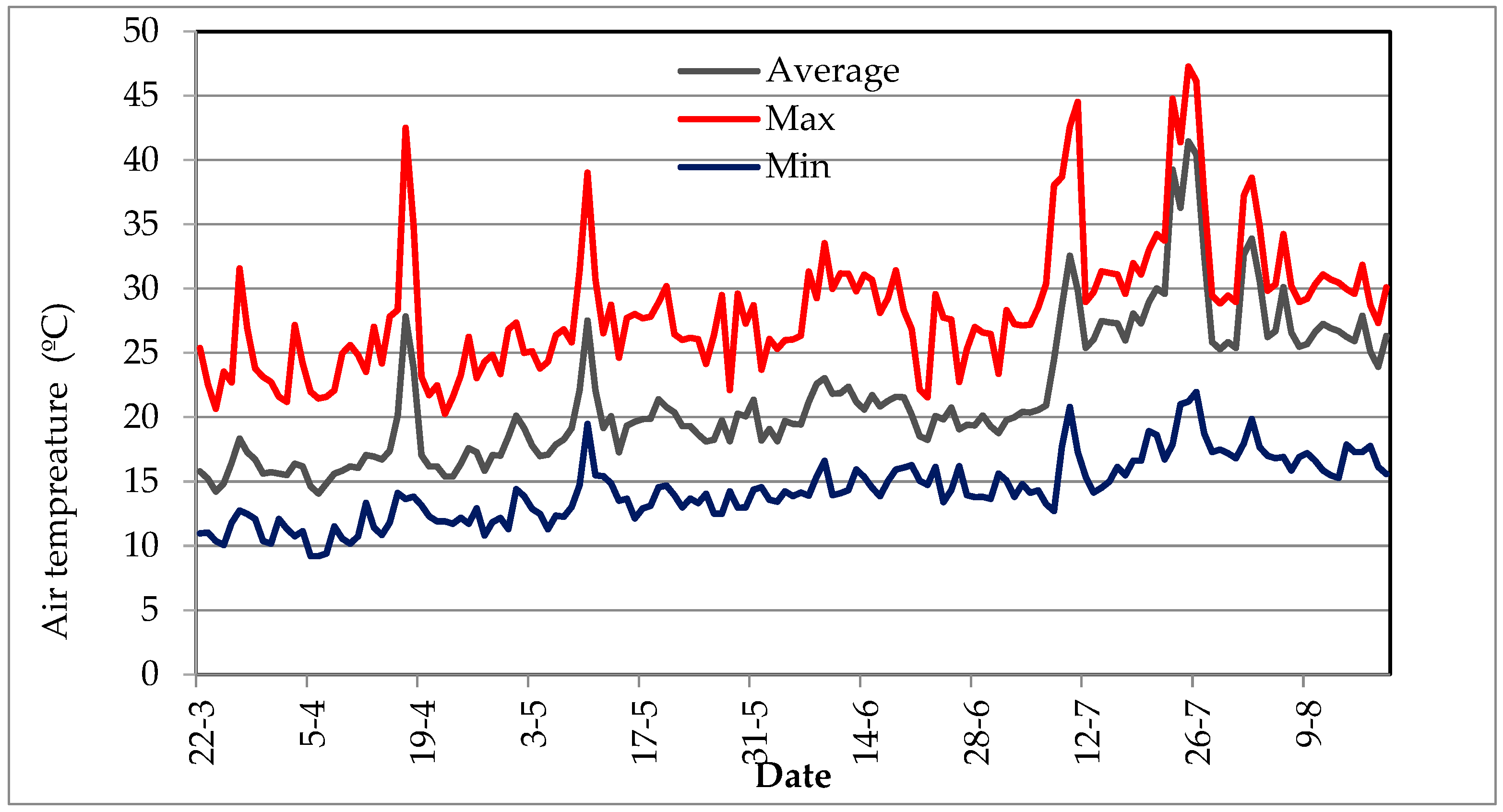

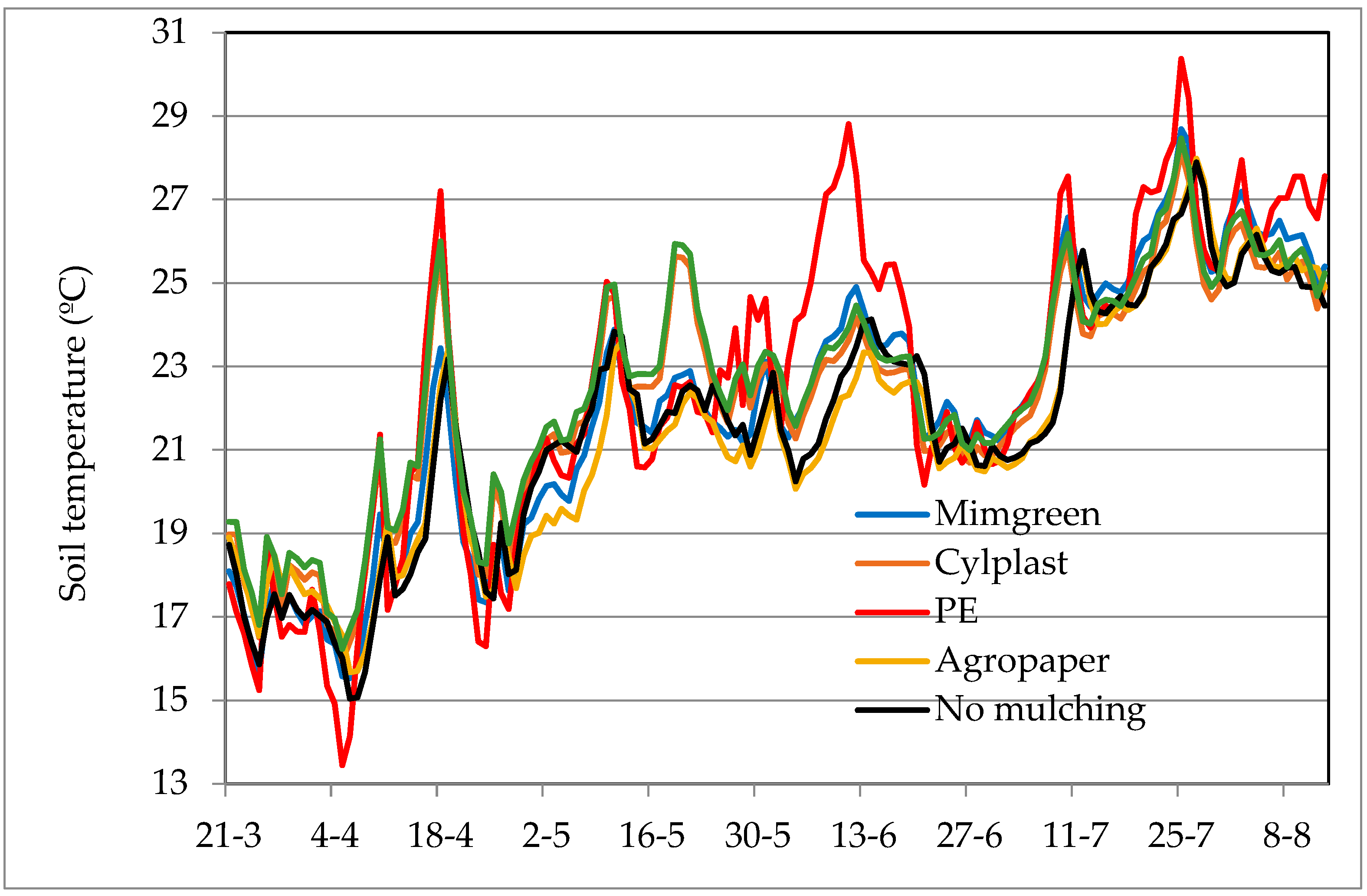

Air temperature and humidity data were taken during the experiment and recorded with an OM-92 logger (Omega Engineering Inc). Soil temperature data were also recorded at 10 cm, with one sensor per treatment, connected to a HOBO Onset logger (T&D Corporation). Air temperature data are presented in

Figure 1, and daily averages of soil temperatures in

Figure 2.

After the end of the trial, at 160 dat, and after removing the PE from the plot, a rototiller was used to incorporate the crop residues and biodegradable materials that remained in the plot (

Figure 3).

3. Results

3.1. Development of Initial Growth

Table 2 shows the influence of mulching on initial plant growth. Plants without mulch developed the first vine at 53-63 dat. Initial plant growth in the plastic mulching was slightly higher than in the paper ones, though with no significant differences. At 63 dat, when the mulching treatments no longer had a single dominant guide, PE mulched plants were similar in value to Mater-Bi plastic and Agropaper. Mimgreen paper and Cylplast plastic had significantly lower initial growth than the control with PE. The control without mulch had a significantly lower initial growth than the other treatments, starting after 53 dat. This could be due to the lower soil temperature (figure 2) or competition with weeds.

3.2. Evolution of Fruit Production

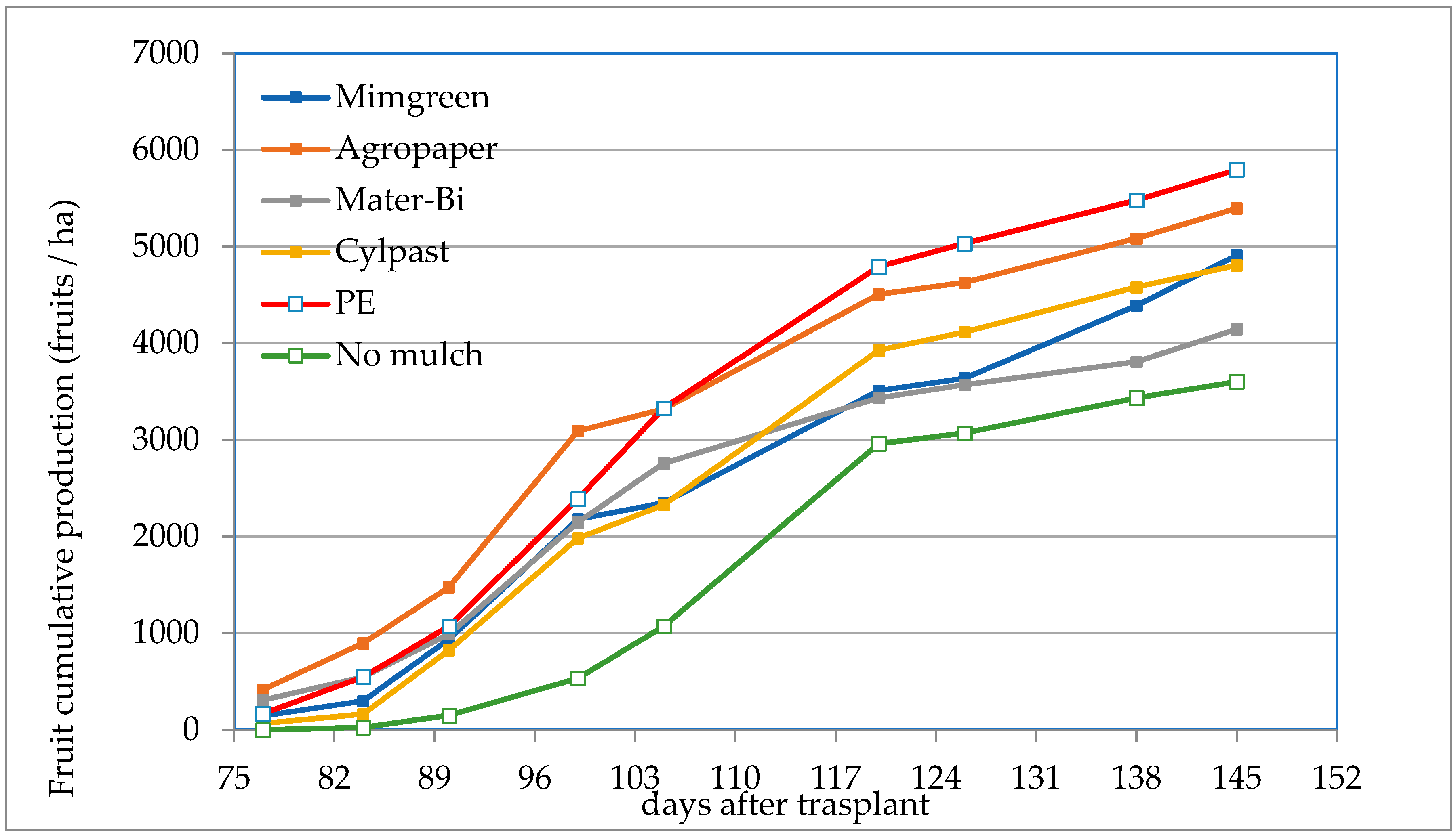

Table 3 and

Figure 4 show that the fruit yield in the treatment without mulch was lower throughout the entire period monitored. At the beginning of the period, there was a slight advantage of mulch paper, especially Agropaper over plastic. From 96 dat onwards, PE had a slightly higher fruit production than Agropaper. In a second step, the other materials up to 103 dat, Mimgreen and Cylplast had a slightly higher fruit production than Mater-Bi, although without significant differences. In the period between 103 and 120 dat, the fruit setting dropped significantly, probably due to the high temperatures (

Figure 1) [17].

Regarding the final data (

Table 3), at 145 dat, the control with PE produced almost 5800 fruits/ha, followed by Agropaper, Mimgreen and Cylplast at around 5000 fruits/ha, with no significant differences with the control. Mater-Bi, with slightly more than 4000 fruits/ha, did not differ significantly from the biodegradable materials, but did differ significantly from PE.

3.3. Yields

Commercial production was relatively low for normal values in the area (40 - 50 t/ha) but not due to trial-related causes (partridge damage in the first fruit sets and malformations due to viruses and pollination problems due to high temperatures).

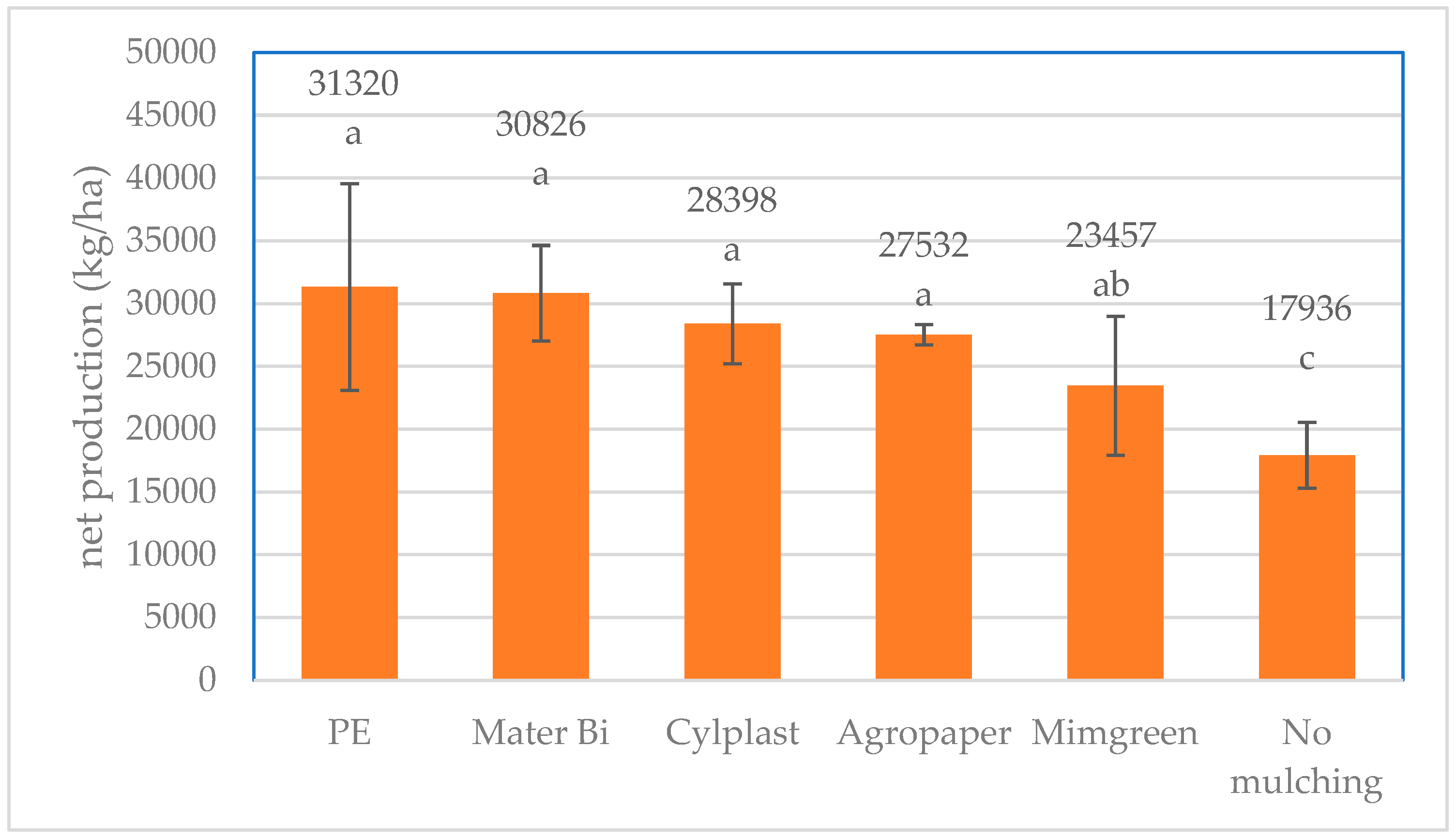

All of the mulching treatments (23,457 – 31,320 kg/ha) had a significantly higher value than no mulching (17,936 kg/ha) (

Figure 4). All materials tested had a statistically similar value to the control with PE (31,320 kg/ha), with biodegradable plastics (28,398 kg/ha and 30826 kg/ha for Cylplast and Mater-Bi, respectively) and Agropaper (27532 kg/ha) standing out.

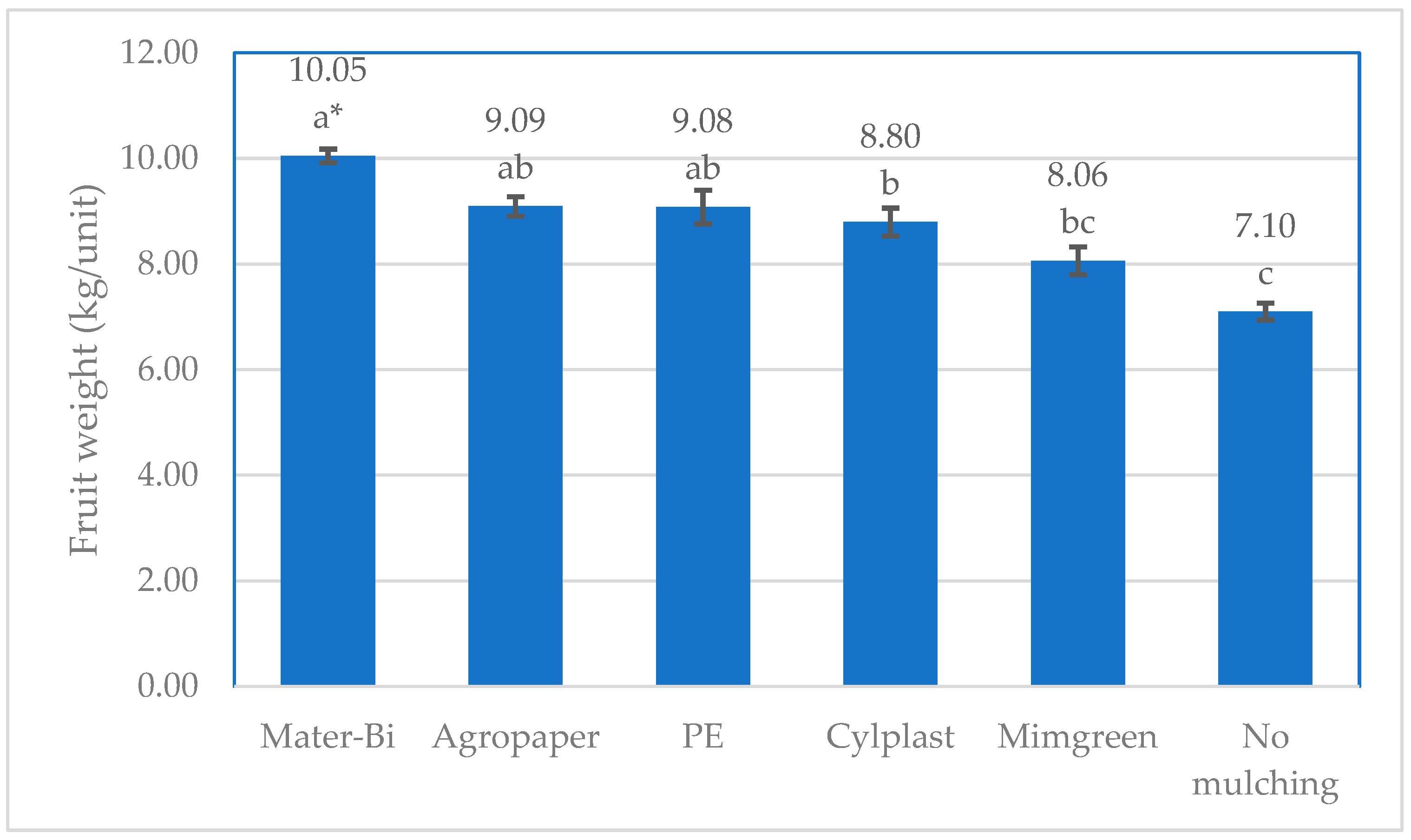

3.4. Average Fruit Weights

The highest mean weight corresponded to the treatment with Mater-Bi (10.1 kg/piece), followed by Agropaper and polyethylene, which exceeded 9.0 kg/piece (

Figure 5). Cylplast plastic and Mimgreen paper, without giving significantly higher values than Mater-Bi, were similar to the PE control. The treatment without mulch, with only 7.1 kg/piece, had the lowest squash weight, significantly lower than the control with PE.

Figure 5 also shows the standard deviations of the weights of each treatment, as there is no size or weight classification for this type of squash. The ranges of the pumpkins harvested in the mulched plots are between 7.27 and 10.43 kg/piece, with Mater-Bi standing out with 9.7 - 10.4 kg/piece. In contrast, the treatment without mulching was between 6.6 and 7.6 kg/piece.

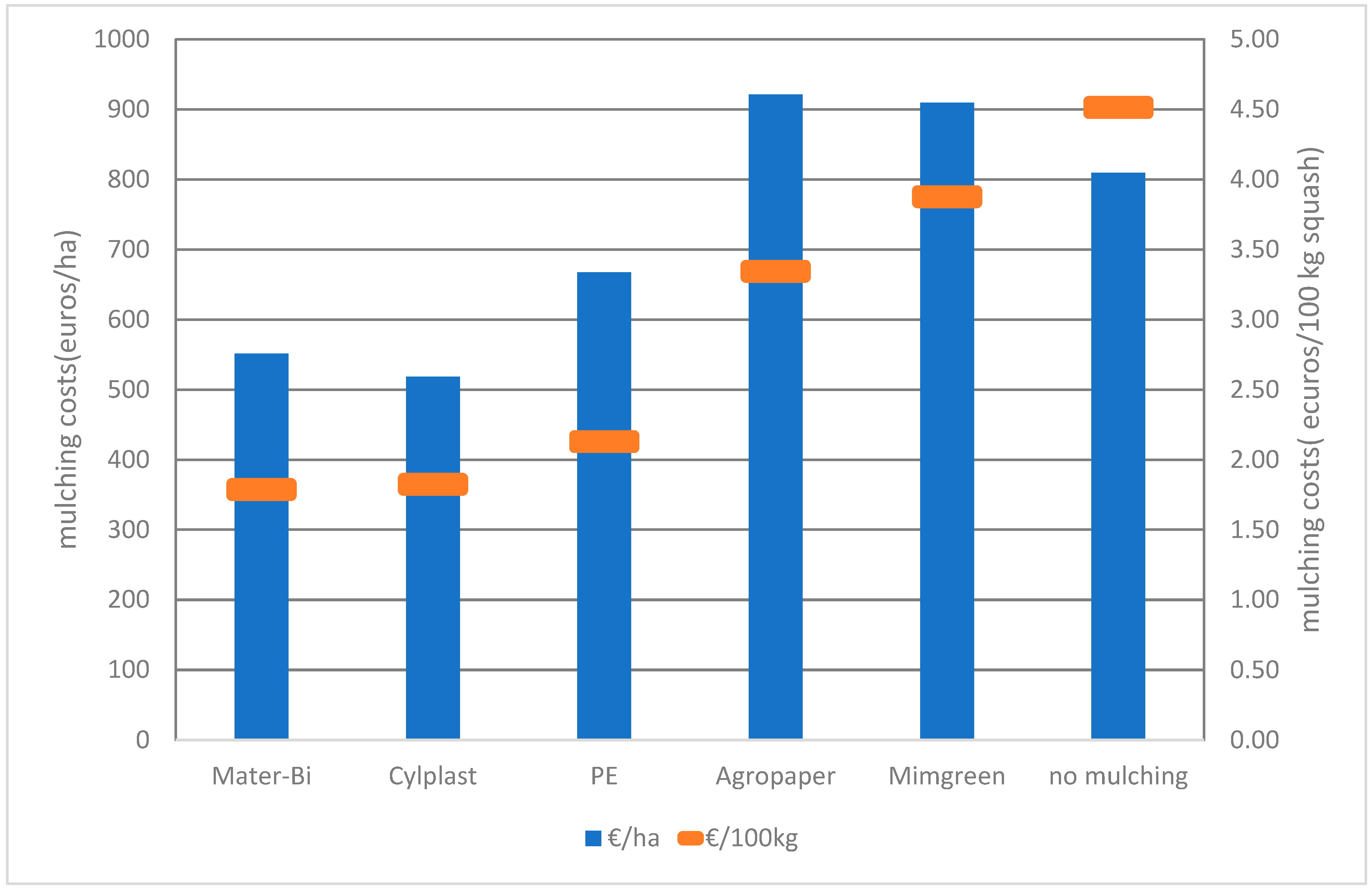

3.5. Costs Associated with Mulching

This section presents the costs of mulching with each material and, in the case of the control, the costs of weeding. When calculating the total costs, the possible differences in the speed of application of each material were not taken into account: some authors point out that paper should be applied at a slower speed [18]. No specific cost was considered for the incorporation of the biodegradable materials because their state at the end of the growing cycle meant that no specific work was necessary, and they were carried out as part of the normal work for the next crop.

The time taken to remove the PE was measured on the farm itself, 17.5 hours/ha. The material collected was also weighed, 550 kg/ha. In the case of the treatment without mulch, two manual weeding operations had to be carried out with a duration of 42 hours/ha.operation.

Papers were higher priced than polyethylene (

Table 5), about 1.9 times more expensive. For plastics, prices were much more similar, about 1.2 times higher. It should be noted that the biodegradable plastics were less thick than the PE used.

The biodegradable materials do not have the costs of removal, transport to the waste management company and management that would have to be charged for polyethylene. Under the trial conditions, this cost amounted to 194.69 €/ha.

The total cost of mulching with PE was 667.30 €/ha (2.13 €/100 kg produced) (

Table 5 and

Figure 6): Cylplast was 518.43 €/ha and Mater-Bi was 551.33 €/ha and mulching costs of 1.79 - 1.83 €/100 kg. The costs of the two papers were almost 50% more expensive than PE, above 900 €/ha and 3.00 €/100 kg.

4. Discussion

Due to the low temperature period at the beginning of the trial, growth was slower than expected. The minimum growth temperature of the pumpkin is 17°C [18]. In

Figure 1, this temperature was not reached on average until 35 - 40 dat. This may have influenced the differences in growth between the plastic mulching treatments compared to the control and to a lesser extent compared to those using paper. Higher temperatures under plastic mulch could favour crop growth [19,20]. Indeed, in

Figure 2, temperatures were higher under the plastic than under paper and bare soil (

Figure 2).

Tofanelli and Wortman (2020) in a meta-analysis found that yields using biodegradable plastics and PE as mulch were similar, irrespective of the crop [21]. The same authors noted a certain decrease in yields in the case of paper. No differences were found in the number of fruits or in pumpkin production between the use of mulching with PE, biodegradable materials (plastics and paper) or not using this technique in subtropical areas in summer crops where there is good weed control [19]. In our case, spring growing conditions may have favoured better mulching behaviour (see

Figure 2 for root environment temperatures). As in other trials, the production in the paper mulch was somewhat lower, which may be due to wind breakage, which led to a higher presence of adventitious weeds. On the other hand, the irrigation of the plot was managed with tensiometers placed in rows with plastic, so the management was not the most optimal for paper, which seems to have a higher direct evaporation [22].

The prices of the materials used were lower than those reported by [

5,

10] which indicated prices up to 3 to 4 times higher for biodegradable materials compared to PE. In other studies, the biodegradable materials used cost twice as much as PE [

12]. This may probably indicate lower prices for biodegradable materials due to the higher volume produced in recent years. The removal costs of PE make the cost of mulching with biodegradable plastics lower than with non-biodegradable plastics, compensating for the higher cost of biodegradable plastics. The higher price of paper makes it more expensive, although it can be quite interesting for controlling some weeds [

5,

9] and in conditions where 100% biodegradability is to be ensured. On the other hand, they are apparently somewhat more complicated to lay and are more sensitive to windy conditions on farms.

In the light of the results of the trial, and for its conditions, it can be concluded that in this first experimental-demonstrative experience with the use of biodegradable materials as mulch in horticultural crops in the Canary Islands, the potential of the materials tested has been proven against the control with PE, achieving similar productive behaviour in terms of production and size.

Within this experimental strategy, work on the use of biodegradable mulching materials should continue. Future studies should adjust irrigation management to the use of papers. Testing of the biodegradability of plastic materials and the presence of microplastics in the soil is also necessary as well as demonstrating the good performance of biodegradable mulching materials in other crops.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R. and B.S. methodology, B.S.; validation, D.R. and B.S..; formal analysis, D.R. and B.S.; investigation D.R. and B.S.; resources, D.R. and B.S.; data curation, D.R. and B.S; writing—original draft preparation, D.R. and B.S; writing—review and editing, D.R. and B.S.; visualization, D.R. and B.S.; supervision, D.R.; project administration, D.R. funding acquisition, D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the companies that participated with the material (Valletek, Novamont Iberia, Smurfitt Kappa España and Mimcord SAU), all the staff of the commercial farm where the trial took place and Mr. Juan Cabrera of Instituto Canario de Investigaciones Agrarias (ICIA).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Yingxue, Y.; Velandia, M.; Hayes, D.G.; DeVetter, L.W.; Miles, C.A.; Flury, M. Biodegradable plastics as alternatives for polyethilene mulch films. Advances in Agronomy. 2024. 183: 121-192. [CrossRef]

- López, J.; González, J. Tendencias y trabajos de campo con acolchados biodegradables. Vida Rural. 2012. 344: 28-32.

- Hu, Q., Li, X., Gonçalves, J. M., Shi, H., Tian, T., & Chen, N. Effects of residual plastic-film mulch on field corn growth and productivity. Science of the Total Environment. 2020. 729, 138901. [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, Z.; Schröder, H. Plastic debris in plastic-mulched soil—a screening study from western Germany. PeerJ, 2022. 10: e13781. [CrossRef]

- Cirujeda, A.; Aibar, J.; Anzalone, L.; Martín, R.; Meco, M.M.; Moreno, A.; Pardo, A.M.; Pelacho, A.M.; Rojo, F.; Royo, A.; Suso, M.L.; Zaragoza C.. Biodegradable mulch instead of polyethylene for weed control of processing tomato production. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012. 32:889–897. [CrossRef]

- Salama, K.; Geyer, M. Plastic mulch films in agriculture: their use, enviromental problemas, recycling and alternatives. Enviroments. Environments 2023, 10, 179. [CrossRef]

- Malincolico, M. Soil degradabable plastics for a sustainable modern agriculture. Springer. Berlin, Heidelberg (Germany). 2017. 185 p.

- Catalina, F.; López, L.; Marquina, D.; Abrusci, C. Biodegradación de polímeros en tierras de cultivo. Revista de plásticos modernos: Ciencia y Tecnología de Polímeros 2006, 603: 256-262.

- Haapala, T.; Palonen, P.; Korpela, A.; Ahokas, J. Feasibilty of paper mulches in crop production: a review. Agricultural and Food Science. 2014. 23: 60-79. [CrossRef]

- Lahoz, I.; Uribarri, A.; Orcaray, L. El papel como alternativa sostenible al acolchado agrícola. Navarra Agraria. 2020. 240, 13-22.

- Velandia, M.; DeLong, K.L.; Wszelaski, A.; Schexnayder, S.; Clark, C.; Jensen, K. Use of polyethylene and plastic biodegradable mulches among Tennessee fruit and vegetable growers. Hortechnology. 2020. 30(2): 212-218. [CrossRef]

- Velandia, M.; Galinato, S.; Wszelaki, A. Economic evaluation of biodegradable plastic films in Tennessee pumpkin production. Agronomy. 2020. 10:51. [CrossRef]

- Estadística anual de superficies y producciones de cultivo. Available online: https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac/estadisticas/sectorprimario/agricultura/agricultura/E01135A.html (accesed on 8 may 2024).

- Santamarta, J.C.; Miklin, L.; Gomes, C.O.; Rodríguez, J.S.; Rodríguez, J.; Cruz, N. Waste management and territorial impact in the Canary Islands. Land. 2023. 10.3390. [CrossRef]

- European Comission. Directive 2018/850/EU Amending Directive 1999/31/EC; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2018.

- Simulador de costes de transporte de mercancías terrestres. Available online: https://www3.gobiernodecanarias.org/transportes/terrestre/simertran-mercancias/ (accessed on 8 may 2024).

- Staub, J.E.; Wehner, T.C. Temperature stress. In Keinath, A.P.; Wintermantel, W.M.; Zitter, T.A. Eds. Compendium of cucurbit diseases and pests. American Phytopathological Society. St. Paul. (USA). Elsevier. Amsterdam. 2017. pp. 188-189.

- Chen, T.W.; Stutzel, H.; Wien, H.C. The cucurbits. In Wien, H.C.; Stutzel, H. Eds. The physiology of vegetable crops. 2nd Ed. CABI Publishing. Wallingford (UK). 2020. pp. 244-270.

- Ghimire, S.; Wszelaki, A.L.; Moores, J.C.; Inglis, D.A.; Miles, C. The use of biodegradable mulches in pie pumpkin crop production in two diverse climates. Hortscience. 2018. 53(3): 288-294. [CrossRef]

- Miles, C.; Wallace, R.; Wszelaki, A.; Martin, J.; Cowan, J.; Walters, T.; Inglis, D. Deterioration of potentially biodegradable alternatives to black plastic mulch in three tomato production regions. Hortscience. 2012. 47(9): 1270-1277 . [CrossRef]

- Tofanelli, M.B.D.; Wortman, S.E. Benchmarking the agronomic performance of biodegradable mulches against polyethylene mulch film: a meta-analysis. Agronomy, 2020. 10, 1068. [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.H.; Franca, F.; Vieiram, C.; Freitas, Silva, D.; Souza, C.M. Mulching materials and wetted soil percentages on zucchini cultivation. Ciência e Agrotecnología .2020. 44:e006720. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).