1. Introduction

In the agriculture of small fruit and vegetable producers, mulching is a technique that consists of covering the soil with materials such as straw, sawdust, rice husks, paper or plastic films, in order to protect the soil and the root zone of the crop from various environmental factors, as well as pests and weeds [

1,

2,

3]. This technique mainly seeks to protect delicate crops from unfavorable conditions whether biotic or abiotic as a result of extreme climatic conditions and with the aim of avoiding production losses which is reflected in crop yields [

4,

5].

Although it is true that mulches provide improvements in production, one of the most serious points in their use is the fact that most of those that are used belong to plastic film mulches

, that mostly are made of synthetic materials derived from petroleum [

2,

6]. A major drawback of these synthetic mulches, is that once used they must be removed from the field and most is thrown into landfills or burned which represents a significant threat to the environment [

7,

8]. However, even after the practice of removing synthetic mulches there are reports that a considerable percentage (11%) remains in the field which represents 8 kg/ha [

9]. The subsistence in the soil of these fragments of synthetic material, can remain for long periods of time resulting in both the release of toxins and the adsorption of contaminants, as well as in the contamination of water and other organisms [

10,

11].

A viable strategy to overcome this accumulation of synthetic material in soils and consequently the risks of contamination is the search for materials designed to be degraded by microorganisms present in the soil. Biobased mulch films are a potential alternative since they can also provide benefits that allow reducing production losses of agricultural products and if they remain in the soil, they can be degraded by microorganisms present in it [

2,

12].

Various natural materials from biopolymers are being used to make degradable biobased materials. Among these biopolymers we can mention cellulose, the most abundant polymer in the world, renewable, biodegradable and considered a classic example of reinforcing biopolymer in polymeric matrices [

13,

14]. Similarly, we find chitosan, a copolymer obtained after a series of deacetylations of chitin, considered the second most abundant polymer in nature [

15,

16]. Another natural polymer, gelatin, is also of equal importance. This polymer is produced after a series of hydrolysis of collagen from bones, skin and muscle membranes of animals [

17]. Standing out among other characteristics for being low cost as well as presenting good properties in the formation of degradable films [

18].

However, understanding polymer degradation in soils remains a major challenge due to its dependence on polymer properties, soil characteristics, environmental conditions [

19], and thickness since this determines the durability of mulches films. To address this knowledge gap on biopolymer degradation the objective of this study was to prepare mulches films from biopolymer formulations and, evaluate its biodegradation time in soil.

2. Material and Methods

Micro cellulose from fibrous endocarp of waste mango (Mangifera caesia Jack ex Wall) was employed in this study. This was used as reinforcing material with the following characteristics; 40–400 μm in length and 72.44 % crystallinity [

20]. The gelatine was of bovine origin in its granulated form and yellow color, purchased from Gelita Ltd. (Mexico). The chitosan was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Ltd. (Germany), with a medium molecular weight, degree of deacetylation of 75–85%, and a viscosity of 200–800 cps. The reagent-grade glycerol was purchased from J.T. Backer, Ltd. (New Jersey, USA).

2.1. Preparation of Liquid Mulch Film

Two mulching films were prepared in the laboratory using gelatine and chitosan, each material reinforced with micro cellulose (hereafter, GC and ChC). Sample GC used 3% (w/v) hydrated gelatin. When the blend was homogeneous, 0.1% micro cellulose and 0.9 g of glycerol were added. The blend was stirred and heated a temperature of 45 °C. To prepare sample ChC, 1% (w/v) of chitosan was hydrated in an aqueous solution of glacial acetic acid (0.1M) at 25 °C, micro cellulose was added at 0.1% and 0.9 g of glycerol. The formulation was degassed in an ultrasonic cleaner (Branson 2510MT ultrasonic cleaner) for 15 min [

21]. The film-forming solution from both samples was poured onto a plate and dried at 40 °C in a continuous flow oven for 12 h [

22]. The films obtained were separated from the Petri dishes and stored in a desiccator (25 °C) with a relative humidity of 57%.

2.2. Film thickness

The thickness of each sample was determined according to the ASTM D6988-21 standard [

23], using a digital micrometer with an accuracy of 0.001 mm (Mitutoyo Corp. Tokyo, Japan), at 6 random positions along the film.

2.3. Soil Composition

The composition of the soil used for the degradation analysis is shown in

Table 1.

2.4. Biodegradation Studies in Soil

The samples were cut into 3 cm² and placed on the surface of the Petri dish with soil sample. The weight loss assessment was determined gravimetrically, the samples were weighed at 5, 10, 15, 20, 30 and 70 days of degradation. A transparent mulch LDPE sample (0.1 mm, thick) was used as a reference (PM). The samples were cleaned and dried at 60 °C for 24 hours, weighed and the final weight was recorded. Weight loss was calculated using equation 1, and photographic analysis was performed [

24].

2.5. Surface Analysis of Mulches

Photomicrographs were obtained with a Carl Zeiss EVO LS 10 equipment. Samples of the films (5 × 5 mm) were attached to a dual-adhesion carbon conductive tape. Images were obtained at a voltage of 2.5 kV, at controlled laboratory temperature (20 °C), with a resolution of 3–10 nm and magnifications at 500 X [

25].

2.6. Functional Group Analysis

The samples were previously dried (40 °C) for 24 h with the intention of removing traces of adsorbed water. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) studies were carried out using a Perkin-Elmer-Spectrum 100–100 N FT-IR Infrared Spectrometer, following the methodology of Montoya-Escobar et al. [

26], to which some modifications were made specifically in resolution and number of scans. The infrared region was in the range of 4000–650 cm

-1 in transmittance mode, with a resolution of 16 cm

-1 and 24 scans.

3. Results

Figure 1 shows the mulch film obtained by the plate casting method and which presented thickness of 0.045 and 0.055 mm for GC and ChC samples, respectively. These values are within the parameters which is indicated by the ASTM standard [

23], whose nominal thickness does not exceed 0.25 mm. The thickness of the mulch is important since it could determine the durability just as it have positive effects from factors such as soil temperature and humidity as well as the type of agricultural or horticultural crop where it will be used [

27,

28,

29].

Both mulch films (

Figure 1a,b) tend to have a uniform, smooth, transparent and homogeneous appearance, furthermore, no material that has not dissolved is detected.

3.1. Biodegradation Studies in Soil

The weight loss values and photographic record of the materials during degradation

are shown in

Table 2 and Figure 2.

The PM sample was taken as a reference, and did not show any visible changes throughout the analysis. No color changes or cracks are observed that somehow is an indicator for its degradation. Furthermore, no fragmentation of this material was reported and its weight was constant during the 70 days of degradation. This result clearly indicates that the permanence of these synthetic mulches in soil and in contact with microorganisms, is not enough to carry out the biodegradation, and can therefore remain for long periods of time in the environment [

30].

It can be observed that after 5 days the GC sample presented changes in appearance, the material shrinks and yellow marks appear around it. The changes are attributed to the polymer matrix, due to its hydrophilic character since the content of glycerine, it increases the absorption and activity of water within the film [

31]. 10 days into the experiment, GC became brittle, an action attributed to the leaching of the plasticizer. After 20 days of exposure, GC and ChC showed a weight loss of 65% and 55 % (

Table 2), at the end of 30 days, GC showed 90% weight loss, while ChC only 65%. Observing how the GC degrades faster than ChC, since until day 70 a weight loss of 96% could be observed for ChC. This action can be attributed to the crystallinity of cellulose and chitosan, since, being complex structures, microorganisms take longer to adapt and break the bonds between the glucose units [

32], therefore, biodegradation becomes slower.

The results showed that the microbial activity in soil in each sample, can be easily observed after the the first few days, similar situation to the biodegradation works with cotton and linen fibers [

33], which presented a behavior similar to that found here, this referring to biodegradation times and without forgetting that cellulose is the main actor in both works.

On the other hand, the biodegradation results found here clearly indicate that cellulose-reinforced mulch, demonstrate that are a promising alternative to synthetic materials mulches. This also according to the works of Zhang et al. [

34] and Bianchini et al. [

35] who studied the role that biodegradable films play in a crop in relation to the use and promising replacement of conventional polyethylene-based mulch fimls. Both authors conclude that biobased mulch films showed higher degradation rates than commercial plastic mulches. Situation similar to what was found here and with shorter biodegradation times and even complete biodegradation which will allow there is no presence of residuals particules in the soil (refer to the

Figure 2 and

Table 2).

3.2. Surface Analysis of Mulches

Morphological changes due to exposure to soil at different degradation times, were carry out in mulches films through SEM analysis. Deterioration is a superficial degradation that modifies the mechanical, physical and chemical properties of a wide variety of materials, such as the case of mulches. It is mainly the result of the activity of microorganisms growing on the surface or inside a material [

33].

The surface of the PM sample showed roughness and some irregularities associated with the processing and fabrication of the material (

Figure 3a). It can be observed some color changes after 25 days, but without the presence of pores or irregularities. (

Figure 3b). In the GC film, small spherical structures, similar to gelatin particles, were observed (

Figure 3c), However, after 25 days the sample was completely fractured, the analyzed fraction that could be rescued was able to show the growth of mycelia and pores on the surface (

Figure 3d). The existence of mycelium is causing damage to the surface of the GC sample [

36], likewise, weight loss can be observed in

Table 2.

Figure 3e shows the surface of the ChC sample at the start of the test, this material did not present pores. However, the cellulose microfibres integrated into the mixture can be seen. As degradation progresses, fungi and bacteria become very active with the absolute disappearance of the smooth surface of the composite matrix. During the evaluation time, ChC was the one that presented the lowest number of mycelia and spores. On the twenty-fifth day (

Figure 3f), the first mycelia appeared on the surface, these attributed to glycerol and the amorphous regions of the biopolymers present in the matrix. Likewise, the measured attack of microorganisms is due to the antifungal capacity that chitosan has, thus avoiding accelerated degradation [

37,

38,

39].

The presence of filaments of microorganisms on the surface of the films, it fits well with the fact that fungi are ubiquitous and extremely effective in their biodegradation effect under different moisture regimes [

40], as could be seen through the biodegradation test.

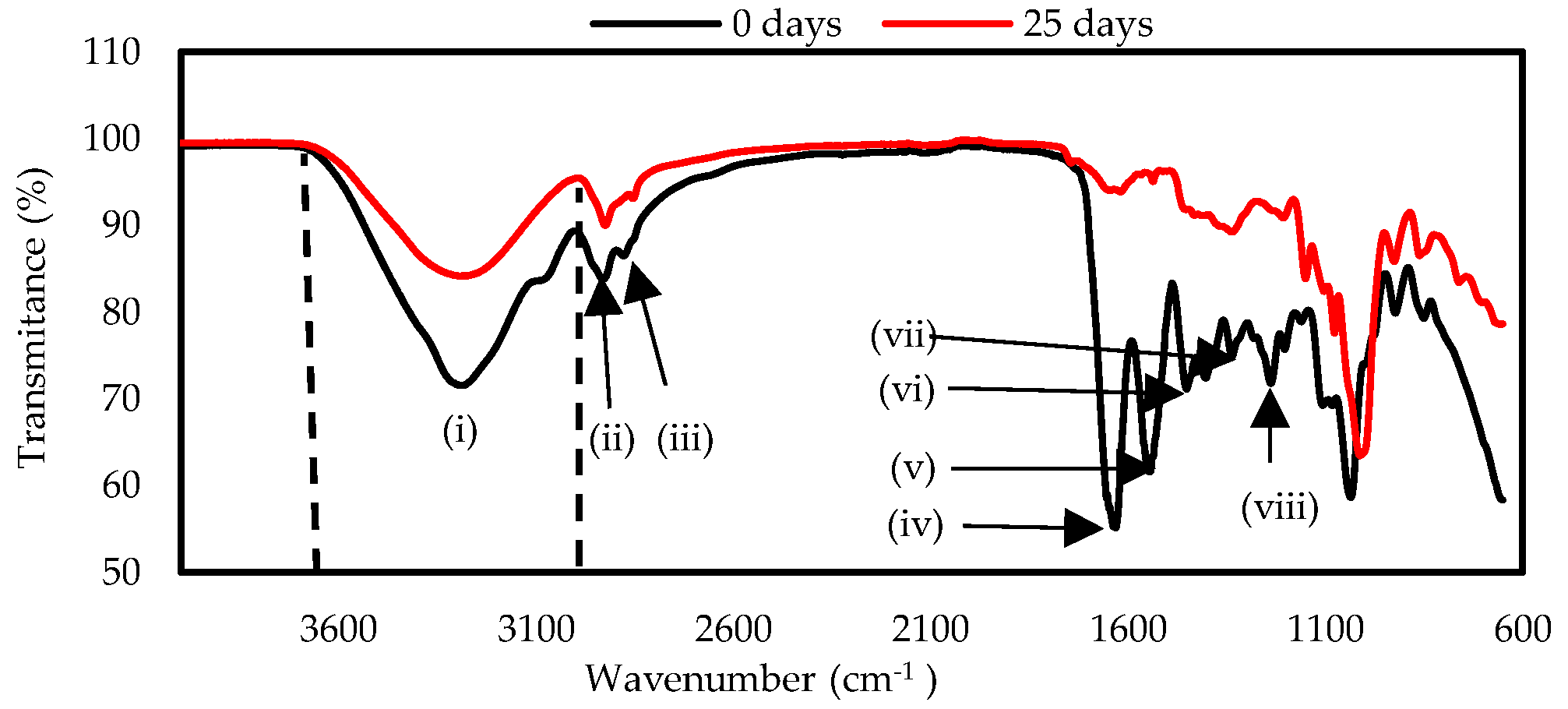

3.3. Functional Groups Anaylisis

The functional groups of the materials GC and ChC were determined before and at the end of the biodegradation test. (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Both samples showed three intense signals at the beginning of the test. The first corresponds to the stretching of the hydroxyl group (

-OH) between 3600 – 3000 cm

-1 (i), which belong to cellulose, glycerol and water. It also indicates the presence of H-N-H bonds present in amino acids [

41] and in chitosan [

42]. The intensity of these bands as well as those of other peaks decreased due to the loss of moisture in the samples and also to the partial breakage of intermolecular and intramolecular hydrogen bonds [

43]. The second and third peaks occurred in the region of 2920 cm

-1 (ii) and 2852 cm

-1 (iii) corresponding to the vibration of the H-C-H bond of polysaccharides [

44,

45]. At the start of the test, the GC sample presented a band in the 1630 cm

-1 (iv), signal corresponding to the C=O stretching vibration present in primary amides, at 1541 cm

-1 (v)corresponds to the stretching vibration of the N-H present in secondary amides, the signal at 1449 cm

-1 (vi) is attributed to aliphatic C-H bending vibrations and the intense peaks at 1335 (vii) and 1233 cm

-1 (viii) indicate the stretching vibrations of the C-N bond present in the amino acids [

45,

46]. The decrease of the peaks 1630, 1541, 1337 and 1206 cm

-1 indicate the rupture of the amide groups and the C-N bonds present in gelatin, as is shown in

Figure 4.

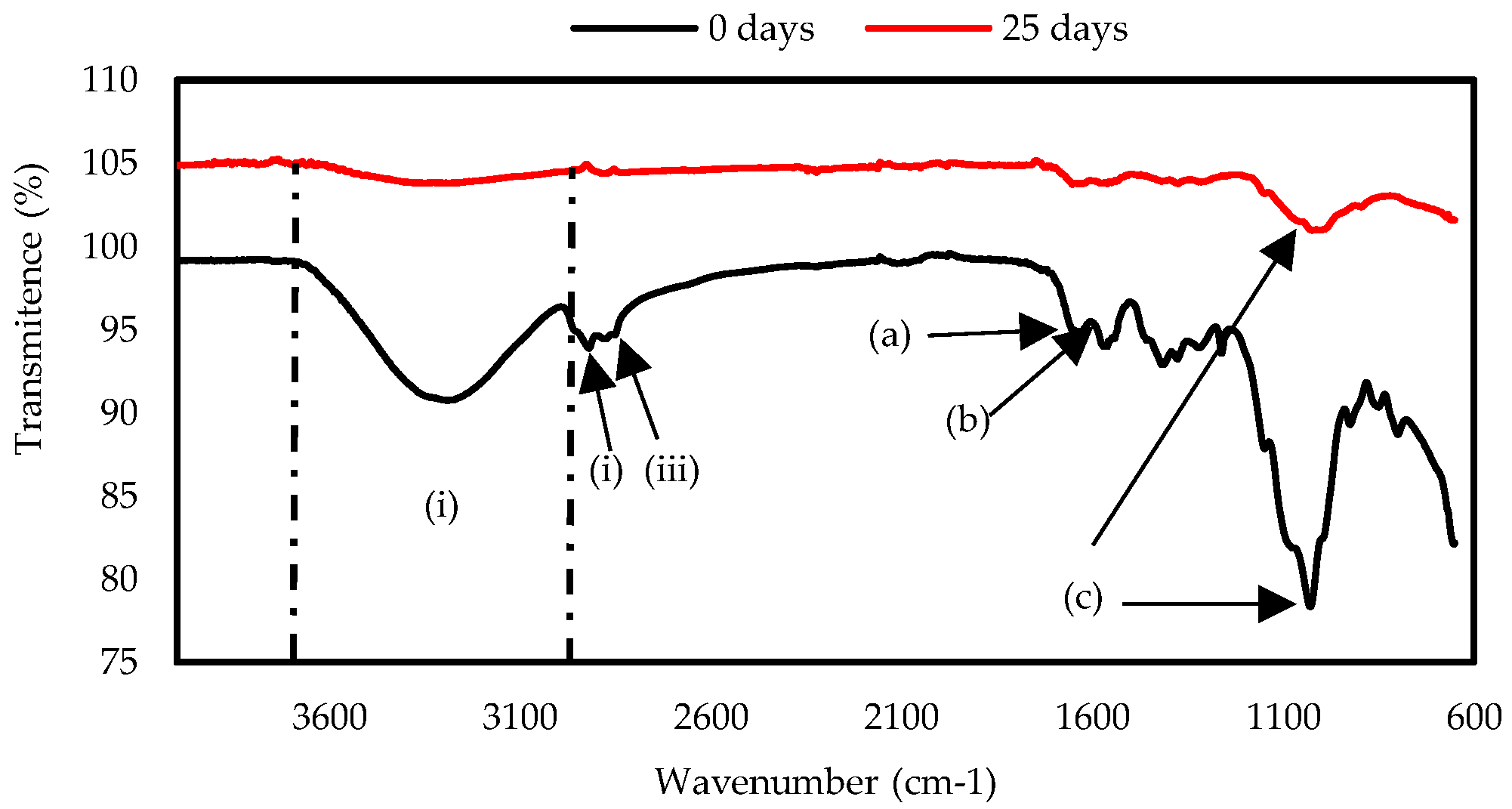

In

Figure 5 the spectra obtained by FTIR of the ChC sample is shown, two bands were observed at the amide groups in 1631 cm

-1 (a) attributed to the C-O stretching and at 1593 cm

-1 (b) corresponding to the N-H bond, present in the chitosan structure [

41]. The most intense band was present at 1026 cm

-1 (c), a signal corresponding to the glycosidic ring [

47]. After exposure in soil for 30 days, the ChC sample showed a decrease in the band at 1026 cm

-1, characteristic signal of chitosan [

48], and the decrease indicates the breakdown of the biopolymer structure.

The changes that can be observed in the FTIR spectrum of ChC in signs 1631 and 1593 cm-1, indicate the degradation of the material. This is due to the fact that the hydrogen bonds formed between the polymers were broken, which can reduce the crystallinity of polymers.

The FTIR spectra of both samples show the characteristic peaks of the polymers, however, several changes can be observed and which indicate the degradation of the material. This is due to the fact that the hydrogen bonds formed between the polymers were broken, which can reduce the crystallinity of polymers. In this sense our results are in agreement with the work of Gonzáles et al. [

49], in their results with starch and chitosan based films.

4. Conclusions

Sample ChC was the one that presented the greatest resistance to the microorganisms present in the mixture since its maximum degradation time was 70 days. On the other hand, GC presented an average degradation time in soil of 25 days, and was the sample that showed the greatest weight loss from day 10 of the test. SEM micrographs showed that microorganisms tend to attack chitosan composite matrices with less intensity, basically attributed to its antifungal capacity. FTIR spectra revealed a decrease in hydroxyl groups, amides and carbonyls bands during the biodegradation test. Based on the results, the films obtained could be used as biodegradables mulch in short-cycle crops, besides that its short biodegradation times will allow their survival in the soil not to be a risk to the environment. While it is true that materials from biopolymers, including cellulose, are more susceptible to microbial development and growth, has certain advantages in materials containing cellulose, mainly when looking for biodegradable and environmentally friendly materials. However, it would be important to evaluate its thermal, mechanical and structural characteristics, this, to have a more complete study of the function of the biobased mulch films. In addition, it is necessary to analyze the behavior of these materials in crops, to determine its capacity and similarity to commercial plastic mulches, since this work was done under laboratory- controlled conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.L.S., S.M.C.R., J.R R.V., and E.G.H.; methodology, M.A.L.S., J.R R.V., and E.G.H.; formal analysis, M.A.L.S., S.M.C.R., and J.R R.V.; investigation, M.A.L.S., and, J.R.R.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.L.S, and J.R.R.V.; writing—review and editing, M.A.L.S., S.M.C.R., J.R.R.V., G.P.V., and E.G.H., supervision, J.R.R.V., Project administration, J.R.R.V, funding acquisition, J.R.R.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Instituto Politécnico Nacional, grant number SIP20220289, SIP20230043.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Instituto Politécnico Nacional and Tecnológico Nacional de México, I.T. Zacatepec for allowing this research to be carried out.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Haapala, T.; Palonen, P.; Tamminen, A.; Ahokas, J. Effects of different paper mulches on soil temperature and yield of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) in the temperate zone. Agric. Food Sci. 2015, 24, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofanelli, M.B.D.; Wortman, S.E. Benchmarking the Agronomic Performance of Biodegradable Mulches against Polyethylene Mulch Film: A Meta-Analysis. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Fu, C.; Li, M.; Qi, X.; Jia, X. Effects of Biodegradation of Corn-Starch–Sodium-Alginate-Based Liquid Mulch Film on Soil Microbial Functions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 8631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.-Y.; Turner, N.C.; Gong, Y.-H.; Li, F.-M.; Fang, C.; Ge, L.-J.; Ye, J.-S. Benefits and limitations to straw- and plastic-film mulch on maize yield and water use efficiency: A meta-analysis across hydrothermal gradients. Eur. J. Agron. 2018, 99, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kader, M.A.; Singha, A.; Begum, M.A.; Jewel, A.; Khan, F. H.; Khan, N.I. Mulching as water-saving technique in dry land agriculture. Bull. Natl. Res.Cent., 2019, 43, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samphire, M.; Chadwick, D.R.; Jones, D.L. Biodegradable plastic mulch films increase yield and promote nitrogen use efficiency in organic horticulture. Front. Agron. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Leng, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, J. Microplastic pollution in vegetable farmlands of suburb Wuhan, central China. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 257, 113449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, G.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Malhi, S.S. Plastic mulch: Tradeoffs between productivity and greenhouse gas emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 172, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasirajan, S.; Ngouajio, M. Polyethylene and biodegradable mulches for agricultural applications: a review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 501–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamas, A.; Moon, H.; Zheng, J.; Qiu, Y.; Tabassum, T.; Jang, J.H.; Abu-Omar, M.; Scott, S.L.; Suh, S. Degradation Rates of Plastics in the Environment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 3494–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briassoulis, D.; Babou, E.; Hiskakis, M.; Kyrikou, I. Analysis of long-term degradation behaviour of polyethylene mulching films with pro-oxidants under real cultivation and soil burial conditions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 22, 2584–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopitar, D.; Marasovic, P.; Jugov, N.; Schwarz, I. Biodegradable Nonwoven Agrotextile and Films—A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerqueira, J.C.; Penha, J.d.S.; Oliveira, R.S.; Guarieiro, L.L.N.; Melo, P.d.S.; Viana, J.D.; Machado, B.A.S. Production of biodegradable starch nanocomposites using cellulose nanocrystals extracted from coconut fibers. Polim. E Tecnol. 2017, 27, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khenblouche, A.; Bechki, D.; Gouamid, M.; Charradi, K.; Segni, L.; Hadjadj, M.; Boughali, S. Extraction and characterization of cellulose microfibers from Retama raetam stems. Polim. E Tecnol. 2019, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, H.; Aghbashlo, M.; Sharma, M.; Gaffey, J.; Manning, L.; Basri, S.M.M.; Kennedy, J.F.; Gupta, V.K.; Tabatabaei, M. Chitin and chitosan derived from crustacean waste valorization streams can support food systems and the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Food 2022, 3, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, K.; Ravichandran, S.; Muralisankar, T.; Uthayakumar, V.; Chandirasekar, R.; Rajeevgandhi, C.; Rajan, D.K.; Seedevi, P. Extraction and characterization of chitin from sea snail Conus inscriptus (Reeve, 1843). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 126, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhao, P.; Wei, Y.; Guo, X.; Deng, X.; Zhang, J. Properties of allicin–zein composite nanoparticle gelatin film and their effects on the quality of cold, fresh beef during storage. Foods, 2023, 12, 3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Shen, R.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Ma, X.; He, L.; Li, A.; Kong, X.; Shi, H. Preparation, Optimization, and Characterization of Bovine Bone Gelatin/Sodium Carboxymethyl Cellulose Nanoemulsion Containing Thymol. Foods 2024, 13, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, M. Biodegradation of Polymeric Mulch Films in Agricultural Soils: Concepts, Knowledge Gaps, and Future Research Directions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 2304–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Santiago, M.A.; Rendón-Villalobos, R. Isolation and characterization of micro cellulose obtained from waste mango. Polim. E Tecnol. 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, L. Structure and properties of the nanocomposite films of chitosan reinforced with cellulose whiskers. J. Polym. Sci. Part B- Polym. Phys. 2009, 47, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranoto, Y.; Lee, C.M.; Park, H.J. Characterizations of fish gelatin films added with gellan and κ-carrageenan. LWT 2007, 40, 766–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society for Testing and Materials. Book of ASTM Standards. Publisher: ASTM International. West Conshohocken, PA, USA. 2021. ASTM D6988-21.

- Rudnik, E.; Briassoulis, D. Degradation behavior of poly (lactic acid) films and fibers in soil under Mediterranean field conditions and laboratory simulations testing. Ind. Crop. Prod, 2011, 33, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón-Villalobos, R.; García-Hernández, E.; Güizado-Rodríguez, M.; Salgado-Delgado, R.; Rangel-Vázquez, N. A. Preparation and characterization of banana starch (Musa paradisiaca L. ) acetylated to different degrees of substitution. Afinidad, 2010, 67, 294–300. [Google Scholar]

- Montoya-Escobar, N.; Ospina-Acero, D.; Velásquez-Cock, J.A.; Gómez-Hoyos, C.; Guerra, A.S.; Rojo, P.F.G.; Acosta, L.M.V.; Escobar, J.P.; Correa-Hincapié, N.; Triana-Chávez, O.; et al. Use of Fourier Series in X-ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis and Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) for Estimation of Crystallinity in Cellulose from Different Sources. Polymers 2022, 14, 5199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suminarti, N.E.; Retno, B.P.A.; Fajriani, S.; Fajrin, A.N. Effect of Size and Thickness of Mulch on Soil Temperature, Soil Humidity, Growth and Yield of Red Beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) In Jatikerto Dry Land, Indonesia. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2020, 20, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Niu, J.; Berndtsson, R.; Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Li, X.; Zhu, Z. Efficient organic mulch thickness for soil and water conservation in urban areas. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shella, R. E.; Wulandari, M.; Wuryan, U. R. T.; Kristianto, S.; Sukian W., S. Comparison of the thickness of rice straw mulch, rice husk and reeds on the observation of the number of fruit plants tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). J. Nat. Sci. Learn., 2023, 2, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ostadi, H.; Hakimabadi, S. G.; Nabavi, F.; Vossoughi, M.; Alemzadeh, I. Enzymatic and soil burial degradation of corn starch/glycerol/sodium montmorillonite nanocpmposites. Polym. Renewable Resour., 2020, 11, 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Liu, K.; Dai, L.; Zhang, J.; Fang, X. The structural and biochemical basis for cellulose biodegradation. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2012, 88, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Soto, K.; de Bog, U.; Piñeros-Castro, N.; Ortega-Toro, R. LAMINATED COMPOSITES REINFORCED WITH CHEMICALLY MODIFIED SHEETS-STALK OF MUSA CAVENDISH. Rev. Mex. De Ing. Quimica 2018, 18, 749–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, K.; Skrifvars, M.; Vivod, V.; PoliMaT, C.o.E.f.P.M.a.T.; Valh, J.V.; Vončina, B. Biodegradation of Natural Textile Materials in Soil. Tekstilec 2014, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Xue, Y.; Jin, T.; Zhang, K.; Li, Z.; Sun, C.; Mi, Q.; Li, Q. Effect of Long-Term Biodegradable Film Mulch on Soil Physicochemical and Microbial Properties. Toxics 2022, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, M.; Trozzo, L.; D'Ottavio, P.; Giustozzi, M.; Toderi, M.; Ledda, L.; Francioni, M. Soil refinement accelerates in-field degradation rates of soil-biodegradable mulch films. Ital. J. Agron. 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalka, S.; Huber, T.; Steinberg, J.; Baronian, K.; Müssig, J.; Staiger, M.P. Biodegradability of all-cellulose composite laminates. Compos. Part A: Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2014, 59, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muxika, A.; Etxabide, A.; Uranga, J.; Guerrero, P.; de la Caba, K. Chitosan as a bioactive polymer: Processing, properties and applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 105, 1358–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado Hernández, A. M.; Barrera Necha, L. L.; Hernández Lauzardo, A. N.; Velázquez del Valle, M. G. Antifungal activity of chitosan and essential oils on Rhizopus stolonifer (Ehrenb. : Fr.) Vuill causal agent of soft rot of tomato. Rev. Colomb. Biotecnol., 2011, 13, 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- El-Araby, A.; Janati, W.; Ullah, R.; Ercisli, S.; Errachidi, F. Chitosan, chitosan derivatives, and chitosan-based nanocomposites: eco-friendly materials for advanced applications (a review). Front. Chem. 2024, 11, 1327426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maran, J.P.; Sivakumar, V.; Thirugnanasambandham, K.; Sridhar, R. Degradation behavior of biocomposites based on cassava starch buried under indoor soil conditions. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 101, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Santhiya, D. In situ mineralization of bioactive glass in gelatin matrix. Mater. Lett. 2017, 188, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardioui, M.; Meftah K. I., M.; el kacem, Q. A.; Bouhfid, R. Bio-active nanocomposite films based on nanocrystalline cellulose reinforced styrylquinoxalin-grafted-chitosan: Antibacterial and mechanical properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol., 2018, 114, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajer, D.; Kaczmarek, H. Study of the influence OV UV radiation on biodegradable blends based on chitosan and starch. Prog. Chem. Appl. Chitin Derivatives, 2010, 15, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, H.; Jun-Yi, Y.; Shao-Ping, N.; Ming-Yong, X. Applications of infrared spectroscopy in polysaccharide structural analysis: Progress, challenge and perspective. Food Chem. X 2021, 12, 100168. [Google Scholar]

- González, S.P.; Medina, C. J.; Famá, L.; Goyanes, S. Biodegradable and non-retrogradable eco-films based on starch-glycerol with citric acid as crosslinking agent. Carbohydr. Polym., 2016, 138, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C.; Tao, F.; Cui, Y. New starch ester/gelatin based films: Developed and physicochemical characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 109, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauricio-Sánchez, R.A.; Salazar, R.; Luna-Bárcenas, J.G.; Mendoza-Galván, A. FTIR spectroscopy studies on the spontaneous neutralization of chitosan acetate films by moisture conditioning. Vib. Spectrosc. 2018, 94, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cordero, A.; Rojas-Sierra, J.; Rodriguez-Ruiz, J.; Arrieta-Álvarez, I.; Arrieta-Álvarez, Y.; Rodríguez-Carrascal, A. Antibacterial activity of chitosan acid solutions obtained from shrimp exoskeleton. Rev. Colomb. Biotecnol. 2014, XVI, 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Calderon, J.A.; Vallejo-Montesinos, J.; Martínez-Martínez, H.N.; Cerecero-Enríquez, R.; López-Zamora, L. Effect of chemical modification of titanium dioxide particles via silanization under properties of chitosan/potato starch film. Rev. Mex. Ing. Química 2019, 18, 913–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).