Submitted:

19 July 2023

Posted:

20 July 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biodiversity

3. Productive Activities

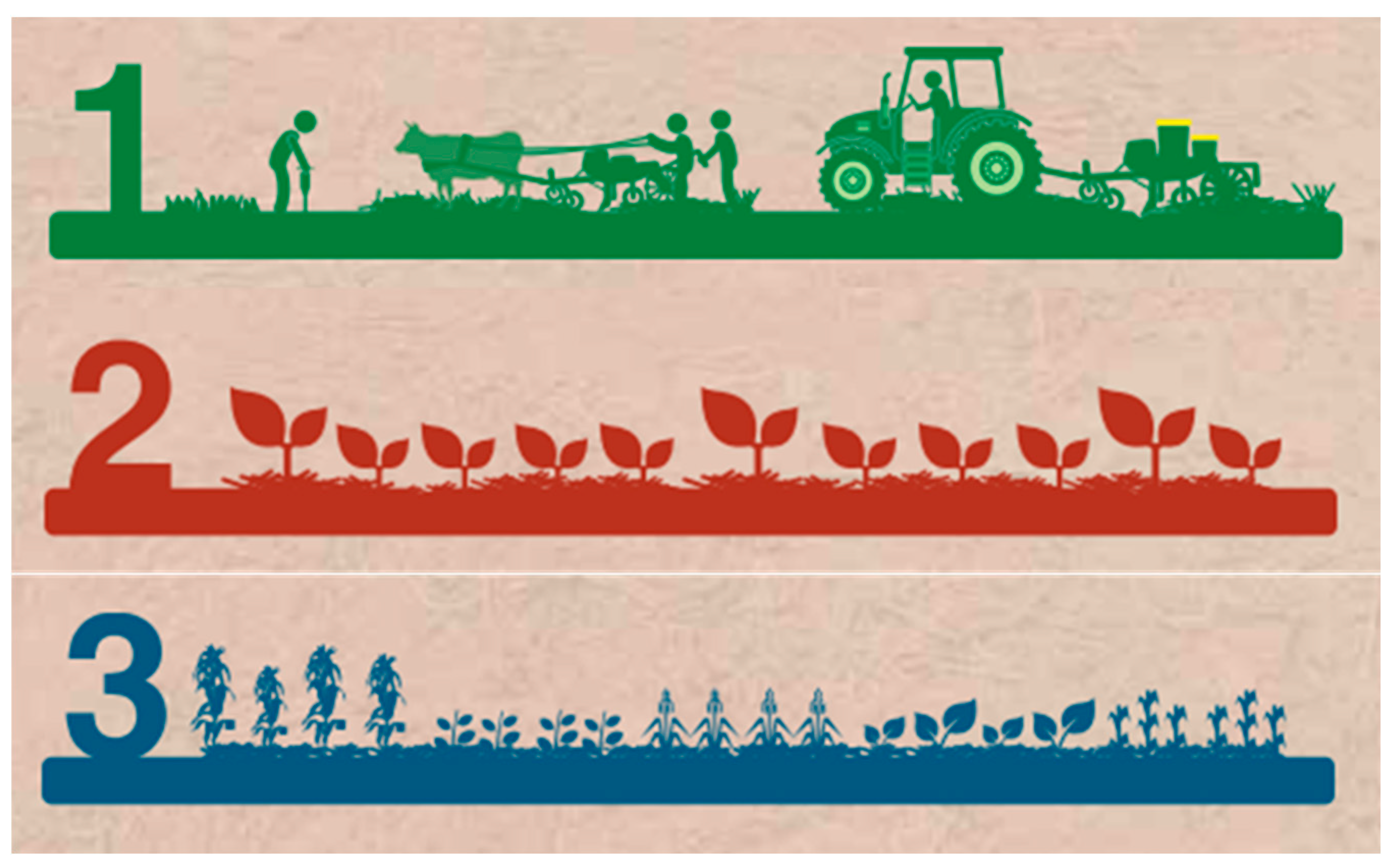

3.1. Cultivation

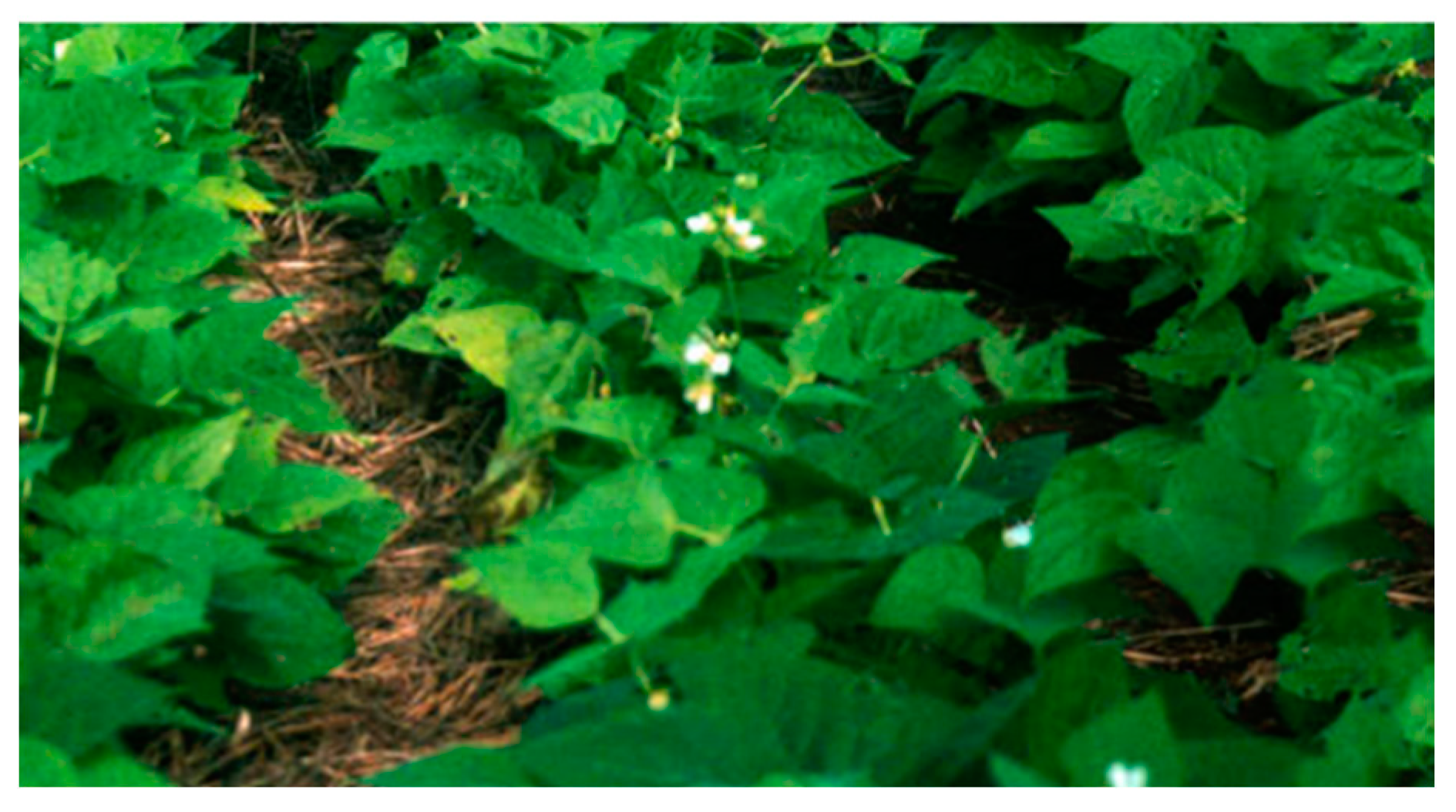

3.1.1. Conservation Agriculture

- Strigosa oat or Black oat (Avena strigosa Schreb),

- White lupine (Lupinus albus L.),

- Oleaginous radish (Raphanus sativus L. var. oleiferus Metzg),

- Hairy pea (Vicia villosa Roth),

- Rye (Secale cereale L.),

- Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.),

- Cassamel or gorse (Spergula arvensis L.).

3.1.2. Site Selection

3.1.3. Ambient Ecological and Social Impact

3.1.4. Climate

3.1.5. Soil and Fertilization

- It is necessary to ensure the use of appropriate types and amounts of fertilizers (both organic and chemical) through agricultural research [14]. Obtaining documented information about the type and amount of fertilizer used and the results obtained can help determine the appropriate amount to use.

- ○

- By creating buffer zones, or buffer zones next to a watercourse (a downstream buffer zone). In these areas, trees, shrubs, and perennial plants are used to filter runoff water before it reaches the watercourse/watercourse. Buffers capture sediment, nutrients, and pathogens and reduce soil erosion by creating a dense root system that holds soil in place. In addition, these areas allow native plants, animals, and insects to thrive, which enhances the area's ecosystem (Leavell and Turpin, undated). To create a buffer next to a stream, install a group of trees, shrubs, and perennials that thrive with varying amounts of water, with sometimes the buffer zone flooding and flooding the plants, while other times the area dries up (Leavell and Turpin, n/d).

- ○

- By growing cover crops and “green manure” such as alfalfa [14].

3.1.6. Irrigation and Drainage

- Irrigation should be controlled and implemented according to the needs of the plants [38].

- Water used for irrigation should comply with regional/national quality standards [38].

- The farmer should pay attention to the quality of irrigation water. Irrigation water must comply with established quality standards and be as free as possible from pollutants [39].

3.1.7. Field Maintenance and Plant Protection

- The crop must be adapted to the growth and needs of the plants [38].

- Insecticides and herbicides should be avoided as much as possible. If application of approved plant protection products is required, the following should be considered

- ○

- The order should only be performed by qualified personnel, using approved equipment [38].

- ○

- Information about the order and the pesticide should be documented and made available to the purchaser, if requested [39].

- ○

- The organization/company carrying out the cultivation must assign a person to check compliance with the processing and sign the documents necessary to accept responsibility [39].

- ○

- The minimum time interval between this treatment and the time of harvest must be specified by the purchaser or as recommended by the manufacturer of the plant protection product.

- ○

- Regional and/or national regulations on remaining maximum limits must be adhered to. If the product is intended for the European market, compliance must be ensured, for example with European Pharmacopoeia regulations, EU pesticide database and other European directives, Codex Alimentarius, etc.) [38,39].

- ○

- Particular attention should be paid to monitoring and removal of toxic herbs (eg herbs containing pyrrolizidine and tropane alkaloid) [39].

3.1.8. Seeds and Propagation Material

- Seeds and vegetative propagating material must be identified botanically and, to be traceable, the species and, whenever necessary and possible, the subspecies of the plant variety, chemotype and origin, must be documented. Recording these characteristics allows the control and identification of incompatible plants, especially incompatible toxic ones, which should be eliminated as much as possible (EUROPAM, 2022).

- Seeds should have an appropriate degree of purity, vigor, and germination rate so that they are, as far as possible, free from pests, diseases and (poisonous) weed seeds [39]

- Consider permanent organic soil cover and species diversification to promote soil health and prevent pests and diseases.

- Considering the external environmental conditions and avoiding the risks of pollution.

- Consider the environmental and social impact on local communities and monitor the impact over time.

- Know in advance the duration of sunlight, average precipitation, and average temperature, including temperature differences during the day and night.

- The crop must be adapted to the needs of the plants and the use of pesticides and herbicides should be avoided. Particular attention should be paid to weeding.

3.2. Harvest

3.2.1. Conservation

3.2.2. Recommended Practices

- The following are some recommendations for the sustainable management of the MAP crop.

- To limit the PAM harvest to a sustainable level, an effective management system must be established that considers annual harvest quotas, seasonal or geographic restrictions, and harvest restriction to certain plant parts or size classes [51].

- Harvest time depends on the part of the plant that will be used. Detailed information on the appropriate timing of sample collection should be consulted, which is often available in national pharmacopoeia, published standards, formal studies, and major reference books [14].

- Continuous improvement of harvesting techniques should be sought to reduce waste at this stage, avoid loss of quality and reduce yield [55].

- Harvesting should take place when the plants are of the best possible quality, according to the different uses [16].

- Plants should be harvested in the best possible conditions, avoiding wet soil, dew, rain, or exceptionally high air humidity. If harvesting takes place in humid conditions, the potential adverse effects on the plant should be neutralized [16].

- During harvesting, care must be taken to ensure that toxic herbs do not mix with the harvested crop [16].

- Materials from decaying medicinal plants must be identified and disposed of during harvesting, post-harvest inspections and treatment processes, to avoid microbial contamination and loss of product quality [14].

- When necessary, large fabrics, preferably made of clean cotton cloth, can be used as an interface between the harvested plants and the soil [14].

- Equipment used for harvesting must be kept clean and in perfect working order. Parts of equipment/machinery that have direct contact with the harvested crop should be cleaned regularly and kept free of oils and other contaminations, including plant residues [16].

- Cutting devices should be modified so that aggregation of soil particles can be minimized [16].

- All containers used for collection must be kept clean and free from contamination from previously harvested medicinal plants and other foreign matter. When not in use, containers should be kept in a dry place and should be protected from insects, rodents, birds, pests, livestock, and pets [14].

- Harvested plants should be collected and transported immediately in dry, clean conditions and in a way that prevents overheating [16].

- Mechanical damage and compaction of the harvested plant, which may result in undesirable changes in quality, should be avoided. In this sense, attention should be paid to cyst overfilling or overcrowding [17].

- The collection organization must appoint a person to verify the compliance of the processing with the rules established in the management system [16].

- ●

- Create an effective management system that considers:

- ○

- spoon quantity,

- ○

- harvest season,

- ○

- status of the plant community.

- ●

- Promote continuous improvement of harvesting techniques to reduce waste at this stage, avoid loss of quality and reduce yield.

- ●

- Keep all containers and tools used in harvesting clean and free from contamination.

- ●

- Avoid unwanted alterations in plant quality during collection and post-harvest transportation.

- ●

- Checking the compatibility of processing with the established effective management system.

3.3. Drying

- Freshly harvested material should be transported in clean, dry, and well-ventilated containers as soon as possible to the drying site [16].

- In the case of natural drying in the open air, the crop should be spread in a thin layer. To ensure adequate air circulation, drying racks should be placed at a sufficient distance from the floor. An attempt must be made to obtain uniform drying of the crop and thus avoid mold formation. When drying with oil, the gases released for drying must not be reused. Direct drying should not be allowed, except with butane, propane or natural gas [17].

- In the drying room, the fresh material should be spread in thin layers on a clean surface (for example, drying racks or plastic cloths), avoiding direct contact with the ground, and in order to protect the material from rain and moisture, the material (such as other plants in the surrounding area, stones, dust, plastics, etc.), pollutants (detergents, smoke, allergens, etc.), pests and pets [16].

- Harvested material that has been spoiled or damaged (which can be identified by bite marks and/or unusual color, texture and/or smell) should be excluded [16].

- When PAM materials are prepared for use in a dry form, the moisture content of the material should be kept as low as possible to minimize damage from mold and other microbial infections [14].

- When possible, temperature and humidity should be controlled to avoid spoilage of active chemical ingredients [14].

- It must be considered that drying by traditional methods, such as an open-air dryer, reduces the quality of the product while increasing the cost and time of the drying process [61].

- The drying process is characterized by an ideal relative humidity level of 50 to 60% [61].

- Information on the appropriate moisture content of some herbal substances may be available in pharmacopoeia or other formal monographs and should be consulted [14].

- ●

- Determination, control, and verification of the criteria of basic economic and environmental criteria in the drying process that affect energy consumption and the quantity and quality of the active ingredients of the plants, namely:

- ○

- drying method,

- ○

- air speed,

- ○

- air temperature

- ○

- exposure time.

- ●

- Ensure optimal final moisture content to avoid over-drying and reduce drying time, energy costs, mass loss and risk of quality degradation.

3.4. Extraction

3.4.1. Solvents

3.4.2. Methods

- Choose non-toxic solvents.

- Estimate relative CO2 emissions associated with extraction methods and prefer methods with greater energy efficiency, lower CO2 emissions and lower cost.

3.5. Packaging

- Medicinal plant materials should be packaged as quickly as possible to prevent damage to the product and to protect it from potential pest attacks and other sources of contamination [14].

- To eliminate unwanted materials before and during the final stages of packaging, continuous process quality control procedures must be implemented [14].

- Batch packing records must be kept for three years, or as required by national and/or regional authorities, which include product name, place of origin, batch number, weight, job number and date [14].

3.5.1. Packing Materials

- After final inspection and disposal of any foreign matter, the product should be packed in clean and dry bags, sacks, bales or cans, suitable for food, preferably new [39].

- Packaging materials should be stored in a clean, dry, pest-free place, inaccessible to livestock, pets, and other sources of contamination. Also, it must be ensured that the product is not contaminated with the packaging material (especially in the case of a fiber bag) due to lose plastic fibers, chemical residues, strange odors, or any kind of household waste [16,17,39].

- When packaging, adhere to standard operating procedures and national and/or regional regulations of the producing countries and the end user [14].

- It is recommended that fragile medicinal plant materials be packed in rigid containers [14].

- Whenever possible, the packaging used should be agreed upon between the supplier and the purchaser [14].

3.5.2. Label

- ●

- The label must be clearly visible and permanently attached and must be made of a non-toxic material [39].

- ●

- ○

- The common and scientific name of the plant,

- ○

- used parts of the plant,

- ○

- The name and address of the product.

- ○

- production batch number,

- ○

- quantitative information (eg package weight),

- ○

- preservation techniques (if any),

- ○

- place of origin, i.e., place of cultivation or assembly,

- ○

- date of cultivation or collection,

- ○

- Hazard information (if any),

- ○

- packing and moving arrangements (if any),

- ○

- In the case of organic products: the organic certificate control number,

- ○

- Information indicating quality approval and compliance with other national and/or regional labeling requirements,

- ○

- Additional information on production standards and quality of medicinal plant materials can be added in a separate certificate attached to the package with the same batch number.

3.5.3. Life Cycle Extension

- Keep packaging materials and storage areas clean and dry.

- Uncontaminated packaging materials are preferred.

- Ensure that re-use does not cause contamination of the product.

- The label must be made of non-toxic material and must clearly contain the relevant information.

- If appropriate, integrate packaging pre-treatment measures that extend its shelf life.

- Follow food safety management system standards applicable to packaging.

- Maintain proper storage temperature (10°C is a recommended value) to prolong the shelf life of herbs.

4. Waste Recovery

4.1. Distillation

4.1.1. Solid Waste

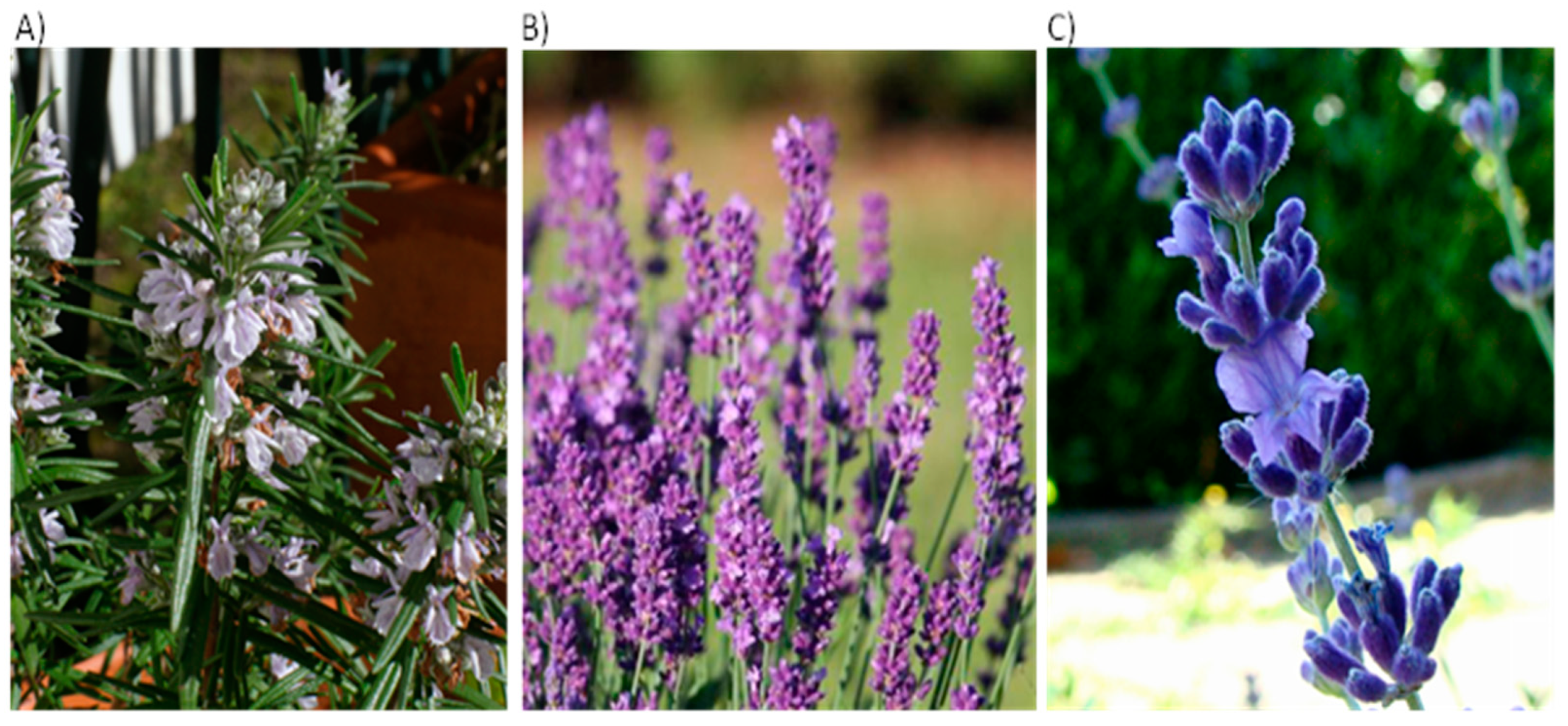

- The solid residue from the water distillation of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) can be used as an antioxidant supplement for pregnant ewes to reduce fat oxidation in meat. Furthermore, the European Commission considers this residue as a semi-natural food preservative additive (regulated under code E-392) [80].

- Solid residues from the distillation of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) and lavandin (sterile mixture of L. angustifolia × L. latifolia), i.e., straw, are cheap, readily available and useful industrial by-products for the production of high-value compounds, as platform particles (such as antibiotics). oxidants) and fungal enzymes involved in the decomposition of lignocellulosic biomass, which have potential as raw materials for the green chemistry industry [83].

- ●

- Energy purposes through direct combustion, making briquettes after drying, pelletizing, gasification, and in methanol and pyrolysis processes, to obtain biodiesel and biochar,

- ●

- Fertilizer,

- ○

- Pulp production,

- ●

- Biosorbents,

- ●

- Vital aggregates for building materials,

- ●

- Fodder or nutritional supplements for animals,

- ●

- Food industries as preservatives,

4.1.2. Liquid Waste

- Hydrates from different parts of the Elderberry (Sambucus nigra) can be used in therapeutic applications due to the pH and trace amounts of the oils. The hydrosols obtained are milder therapeutic agents than essential oils, they are mild and non-toxic and therefore ideal for use as a skin tonic or for therapeutic baths [84].

- Water from the hydro-distillation of lemongrass or lemongrass (Sympopogon citrate) consists of an essential oil rich in emulsified citral, making it a suitable ingredient for food applications. This hydrosol can be used as a functional ingredient in formulations of matcha tea in compliance with beverage safety regulations [78].

- The liquid distillation residue of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) contains phenolic compounds, such as rosmarinic acid and caffeic acid, and can be used in the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industry [82].

- Eco-friendly bio-pesticides,

- Liquid fertilizers,

- Functional dietary fiber and functional ingredient in matcha tea formulations in the food industry,

- Sources of phenolic compounds such as rosmarinic acid and caffeic acid in the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industry.

4.1.3. Waste Extraction

- Solid residue extracts showed antioxidant, anti-fungal, anti-bacterial, anti-inflammatory, and germination-stimulating properties as food preservatives, suitable for various applications in the food, cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries.

- Hydrosol extracts contain biological properties such as nematocidal, insecticidal, antibacterial, antifungal, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory, favoring their use as a medical treatment for hyperlipidemia and cardiovascular diseases.

- Wastewater extracts contain many antioxidants, antifungal, bacterial, enzymatic, and anti-inflammatory biological activities, which favor their use in food additives, cosmetics, or even medical treatments.

4.2. Other Waste

- Although the roots of Levisticus (Levisticum officinale W.D.J. Koch) are generally discarded, they can be a source of valuable bioactive compounds, such as phthalides and phenolic acids, and offer biological properties worth exploring, which can lead to a circular economy in the food and/or pharmaceutical industry [91].

- The alcoholic extract of Elderflower (Sambucus nigra) has good antioxidant activity, and the glycerin extract contains appreciable amounts of anthocyanins and other nutrients. Evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of the extract reveals the great potential of bioactive compounds such as nutraceuticals, drugs, and cosmetics for therapeutic purposes [84].

- Tobacco processing waste (Nicotiana tabacum) can be transformed into new raw materials. Compounds are found in tobacco that exhibit important biological activities, including resistance to many diseases, human health regulation, sterilization, and pest control. The wide range of application scenarios gives by-products of the tobacco processing industry a high potential for recovery [92].

- The use of residual hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) biomass as an alternative and renewable lignocellulosic raw material in the manufacture of lightweight board products is a fundamental principle of the circular economy and an environmentally sound strategy to deal with the increasing scarcity of resources in the wood-based board industry [93]. In addition, hemp residue can be used for composting, incineration, and anaerobic digestion [94].

- Pine bark and buds, previously considered inappropriate waste, have been identified as a rich source of natural polyphenols, which have beneficial nutritional, medicinal and health properties [95].

- The roots of the aloe vera plant (Aloe barbadensis Miller), due to its quinone content, have pharmacological significance and antiviral activity [82].

- A study suggests including the ethanolic extract of the solid remains of female Abrótano (Santolina chamaecyparissus) as a natural ingredient for the development of natural coatings to preserve cheese and prevent oxidation and fungal development [80].

- The use of ethanolic extracts from solid residues of lavender (Lavandula angustifolia) and lemongrass (Melissa officinalis) has the potential to extend the shelf life of bread [80].

- Parts of plants that are often considered waste products (roots, bark and buds) can be a source of valuable bioactive compounds useful in the food, pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries.

- Residues resulting from harvesting, drying and processing can be used in composting to obtain organic fertilizers.

5. Conclusions

References

- Taghouti, I., R. Cristobal, A. Brenko, K. Stara, N. Markos, B. Chapelet, L. Hamrouni, D. Buršić and J.A. Bonet, The Market Evolution of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: A Global Supply Chain Analysis and an Application of the Delphi Method in the Mediterranean Area. Forests, 2022. 13(5). [CrossRef]

- Chandra, P. and V. Sharma, Marketing information system and strategies for sustainable and competitive medicinal and aromatic plants trade. Information Development, 2019. 35(5): p. 806-818. [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.L.A. and U.P. Albuquerque, Indicators of conservation priorities for medicinal plants from seasonal dry forests of northeastern Brazil. Ecological Indicators, 2021. 121(September 2020): p. 106993-106993. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R., Anticancer Medicinal Plants: Opportunities and Challenges For Conservation and Sustainable Use. Ambient Science, 2019. 06H & 06Sp(2 & 1): p. 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N. and C.P. Kala, Harvesting and management of medicinal and aromatic plants in the Himalaya. Journal of Applied Research on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, 2018. 8(February 2017): p. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Pata, U.K., Linking renewable energy, globalization, agriculture, CO2 emissions and ecological footprint in BRIC countries: A sustainability perspective. Renewable Energy, 2021. 173: p. 197-208. [CrossRef]

- Yu, S. and Y. Mu, Sustainable Agricultural Development Assessment: A Comprehensive Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability (Switzerland), 2022. 14(19). [CrossRef]

- Bandinelli, R., D. Acuti, V. Fani, B. Bindi and G. Aiello, Environmental practices in the wine industry: an overview of the Italian market. British Food Journal, 2020. 122(5): p. 1625-1646. [CrossRef]

- Trabelsi, M., E. Mandart, P. Le Grusse and J.P. Bord, ESSIMAGE: a tool for the assessment of the agroecological performance of agricultural production systems. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2019. 26(9): p. 9257-9280. [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M., P. Savaget, N.M.P. Bocken and E.J. Hultink, The Circular Economy – A new sustainability paradigm? Journal of Cleaner Production, 2017. 143: p. 757-768.

- Braga, F.C., Paving New Roads Towards Biodiversity-Based Drug Development in Brazil: Lessons from the Past and Future Perspectives. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia, 2021. 31(5): p. 505-518. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, L.C., J.R. Barbosa, A.L.C. da Costa, F.W.F. Bezerra, R.H.H. Pinto and R.N.d. Carvalho Junior, From waste to sustainable industry: How can agro-industrial wastes help in the development of new products? Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2021. 169(December 2020).

- Yaashikaa, P.R., P. Senthil Kumar and S. Varjani, Valorization of agro-industrial wastes for biorefinery process and circular bioeconomy: A critical review. Bioresource Technology, 2022. 343(October 2021): p. 126126-126126. [CrossRef]

- WHO, WHO guidelines on good agricultural and collection practices (GACP) for medicinal plants. World Health Organization, 2003: p. 80-80.

- Europam, Guidelines for Good Agricultural and Wild Collection Practice ( GACP ) of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. 2006(7): p. 1-12.

- Europam, European Herb Growers Association (EUROPAM) GACP Working Group A Practical Implementation Guide to Good Agricultural and Wild Collection Practices (GACP). 2016. 1-47.

- European Medicines Agency (EMA), Guideline on Good Agricultural and Collection Practice (GACP) for Starting Materials of Herbal Origin. EMEA, 2006(February): p. 1-11.

- Felix, L., T. Houet and P.H. Verburg, Mapping biodiversity and ecosystem service trade-offs and synergies of agricultural change trajectories in Europe. Environmental Science and Policy, 2022. 136(July): p. 387-399. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Y. Cao, L. Yu, X. Liu, R. Yang and P. Gong, Future global conflict risk hotspots between biodiversity conservation and food security: 10 countries and 7 Biodiversity Hotspots. Global Ecology and Conservation, 2022. 34(June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Köninger, J., P. Panagos, A. Jones, M.J.I. Briones and A. Orgiazzi, In defence of soil biodiversity: Towards an inclusive protection in the European Union. Biological Conservation, 2022. 268(March). [CrossRef]

- Winkel, G., M. Lovrić, B. Muys, P. Katila, T. Lundhede, M. Pecurul, D. Pettenella, N. Pipart, T. Plieninger, I. Prokofieva, C. Parra, H. Pülzl, D. Roitsch, J.L. Roux, B.J. Thorsen, L. Tyrväinen, M. Torralba, H. Vacik, G. Weiss and S. Wunder, Governing Europe's forests for multiple ecosystem services: Opportunities, challenges, and policy options. Forest Policy and Economics, 2022. 145(May).

- Stryamets, N., M. Elbakidze, J. Chamberlain and P. Angelstam, Governance of non-wood forest products in Russia and Ukraine: Institutional rules, stakeholder arrangements, and decision-making processes. Land Use Policy, 2020. 94(November 2017): p. 104289-104289. [CrossRef]

- Lubbe, A. and R. Verpoorte, Cultivation of medicinal and aromatic plants for specialty industrial materials. Industrial Crops and Products, 2011. 34(1): p. 785-801. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., C. Shi, K. Alamgir, S.M. Kwon, L. Pan, Y. Zhu and X. Yang, Global assessment of the distribution and conservation status of a key medicinal plant (Artemisia annua L.): The roles of climate and anthropogenic activities. Science of the Total Environment, 2022. 821: p. 153378-153378. [CrossRef]

- Vincent, H., D. Hole and N. Maxted, Congruence between global crop wild relative hotspots and biodiversity hotspots. Biological Conservation, 2022. 265: p. 109432-109432. [CrossRef]

- McEwan, C., A. Hughes and D. Bek, Futures, ethics and the politics of expectation in biodiversity conservation: A case study of South African sustainable wildflower harvesting. Geoforum, 2014. 52: p. 206-215. [CrossRef]

- Alzweiri, M., A.A. Sarhan, K. Mansi, M. Hudaib and T. Aburjai, Ethnopharmacological survey of medicinal herbs in Jordan, the Northern Badia region. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2011. 137(1): p. 27-35. [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, M., I. Uysal, E. Karabacak and S. Celik, Plant species microendemism, rarity and conservation of pseudo - Alpine zone of Kazdaǧi (Mt. Ida) national park - Turkey. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2011. 19: p. 778-786.

- Jarić, S., Z. Popović, M. Mačukanović-Jocić, L. Djurdjević, M. Mijatović, B. Karadžić, M. Mitrović and P. Pavlović, An ethnobotanical study on the usage of wild medicinal herbs from Kopaonik Mountain (Central Serbia). Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2007. 111(1): p. 160-175. [CrossRef]

- Dejouhanet, L., S. Assemat, M.A. Tareau and C. Tareau, Building a value chain with a wild plant: Lessons to be learned from an experiment in French Guiana. Environmental Science and Policy, 2022. 138(October): p. 162-170. [CrossRef]

- Millhauser, J.K. and T.K. Earle, Biodiversity and the human past: Lessons for conservation biology. Biological Conservation, 2022. 272(May): p. 109599-109599. [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, S.L., L.A. Domeignoz-Horta, V. Loaiza and A.L. Laine, Plant biodiversity promotes sustainable agriculture directly and via belowground effects. Trends in Plant Science, 2022. 27(7): p. 674-687. [CrossRef]

- Kumar Rai, P. and J.S. Singh, Invasive alien plant species: Their impact on environment, ecosystem services and human health. Ecological Indicators, 2020. 111(January): p. 106020-106020. [CrossRef]

- Kurnaz, M.L. and I. Aksan Kurnaz, Commercialization of medicinal bioeconomy resources and sustainability. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy, 2021. 22(February): p. 100484-100484. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.K., S. Dixit and A.A. Srivastava, Criticism of Triple Bottom Line: TBL (With Special Reference to Sustainability). Corporate Reputation Review, 2022. 25(1): p. 50-61.

- FAO, Conservation Agriculture Principles. Plant Production and Protection Division, 2022: p. 2-3.

- Florentín, M.A., M. Peñalva, A. Calegari, R.D. Translated and M.J. McDonald, Green Manure/Cover Crops and Crop Rotation in Conservation Agriculture on Small Farms. Vol. 12. 2010. 12-2010.

- EMEA, Guideline on Good Agricultural and Collection Practice (GACP) for Starting Materials of Herbal Origin. EMEA, 2006(February): p. 1-11.

- Europam, Guidelines for Good Agricultural and Wild Collection Practice ( GACP ) of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. 2022(7): p. 1-12.

- Volenzo, T. and J. Odiyo, Integrating endemic medicinal plants into the global value chains: the ecological degradation challenges and opportunities. Heliyon, 2020. 6(9): p. e04970-e04970. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, A.B., J.A. Brinckmann, X. Yang and J. He, Introduction to the special issue: Saving plants, saving lives: Trade, sustainable harvest and conservation of traditional medicinals in Asia. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2019. 229(August 2018): p. 288-292. [CrossRef]

- Ihemezie, E.J., L.C. Stringer and M. Dallimer, Understanding the diversity of values underpinning forest conservation. Biological Conservation, 2022. 274(July): p. 109734-109734. [CrossRef]

- Ticktin, T., M. Charitonidou, J. Douglas, J.M. Halley, M. Hernández-Apolinar, H. Liu, D. Mondragón, E.A. Pérez-García, R.L. Tremblay and J. Phelps, Wild orchids: A framework for identifying and improving sustainable harvest. Biological Conservation, 2023. 277(July 2022).

- Palomo-Campesino, S., M. García-Llorente, V. Hevia, F. Boeraeve, N. Dendoncker and J.A. González, Do agroecological practices enhance the supply of ecosystem services? A comparison between agroecological and conventional horticultural farms. Ecosystem Services, 2022. 57(June).

- Šumrada, T., B. Vreš, T. Čelik, U. Šilc, I. Rac, A. Udovč and E. Erjavec, Are result-based schemes a superior approach to the conservation of High Nature Value grasslands? Evidence from Slovenia. Land Use Policy, 2021. 111(February).

- Heywood, V., A. Casas, B. Ford-Lloyd, S. Kell and N. Maxted, Conservation and sustainable use of crop wild relatives. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 2007. 121(3): p. 245-255. [CrossRef]

- Abensperg-Traun, M., CITES, sustainable use of wild species and incentive-driven conservation in developing countries, with an emphasis on southern Africa. Biological Conservation, 2009. 142(5): p. 948-963. [CrossRef]

- Barata, A.M., F. Rocha, V. Lopes and A.M. Carvalho, Conservation and sustainable uses of medicinal and aromatic plants genetic resources on the worldwide for human welfare. Industrial Crops and Products, 2016. 88: p. 8-11. [CrossRef]

- Draper Munt, D., P. Muñoz-Rodríguez, I. Marques and J.C. Moreno Saiz, Effects of climate change on threatened Spanish medicinal and aromatic species: predicting future trends and defining conservation guidelines. Israel Journal of Plant Sciences, 2016. 63(4): p. 309-319. [CrossRef]

- Schippmann, U., D. Leaman and A.B. Cunningham, A Comparison of Cultivation and Wild Collection of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants Under Sustainability Aspects. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, 2007: p. 75-95. [CrossRef]

- Cetinkaya, G., A. Kambu and K. Nakamura, Sustainable development and natural resource management: An example from Köprülü kanyon National Park, Turkey. Sustainable Development, 2014. 22(1): p. 63-72.

- Li, X., Y. Chen, Y. Lai, Q. Yang, H. Hu and Y. Wang, Sustainable utilization of traditional chinese medicine resources: Systematic evaluation on different production modes. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2015. 2015. [CrossRef]

- El-Zaeddi, H., Á. Calín-Sánchez, L. Noguera-Artiaga, J. Martínez-Tomé and Á.A. Carbonell-Barrachina, Optimization of harvest date according to the volatile composition of Mediterranean aromatic herbs at different vegetative stages. Scientia Horticulturae, 2020. 267(February): p. 109336-109336.

- Schippmann, U., D.J. Leaman and a.B. Cunningham, Impact of Cultivation and Gathering of Medicinal Plants on Biodiversity : Global Trends and Issues. FAO. 2002. Biodiversity and the Ecosystem Approach in Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Satellite event on the occasion of the Ninth Regular Session of the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Rome, 12-13 October 2002. Inter-Depart, 2002. 676(October): p. 1-21.

- Máthé, Á., A New Look at Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Acta Horticulturae, 2011. 925(March): p. 13-20. [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Andrade, S.P. and O. Hensel, Stepwise drying of medicinal plants as alternative to reduce time and energy processing. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 2016. 138(1). [CrossRef]

- Bhaskara Rao, T.S.S. and S. Murugan, Solar drying of medicinal herbs: A review. Solar Energy, 2021. 223(May): p. 415-436. [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, A.K. and C.N. Nguyen, Drying of medicinal plants. Acta Horticulturae, 2007. 756: p. 47-54. [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, H., A. Rashidi and M.A. Shourkaei, Life cycle assessment of medicinal plant extract drying methods. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 2023(0123456789). [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R.P., E.C. Melo and L.L. Radünz, Influence of drying process on the quality of medicinal plants: A review. Journal of Medicinal Plant Research, 2011. 5(33): p. 7076-7084.

- Khallaf, A.E.M. and A. El-Sebaii, Review on drying of the medicinal plants (herbs) using solar energy applications. Heat and Mass Transfer/Waerme- und Stoffuebertragung, 2022. 58(8): p. 1411-1428. [CrossRef]

- Europe, C.o. European Pharmacopoeia. 2004 2005; 5th Edition. [: 2004 2005; 5th Edition.

- da Silva, R.F., C.N. Carneiro, C.B. Cheila, F. J. V. Gomez, M. Espino, J. Boiteux, M. de los Á. Fernández, M.F. Silva and F. de S. Dias, Sustainable extraction bioactive compounds procedures in medicinal plants based on the principles of green analytical chemistry: A review. Microchemical Journal, 2022. 175(October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Espino, M., M.d.l.Á. Fernández, F.J.V. Gomez, J. Boiteux and M.F. Silva, Green analytical chemistry metrics: Towards a sustainable phenolics extraction from medicinal plants. Microchemical Journal, 2018. 141(March): p. 438-443. [CrossRef]

- Petigny, L., M.Z. Özel, S. Périno, J. Wajsman and F. Chemat, Water as Green Solvent for Extraction of Natural Products. Green Extraction of Natural Products: Theory and Practice, 2014: p. 237-264. [CrossRef]

- Dukić, J., M. Hunić, M. Nutrizio and A. Režek Jambrak, Influence of High-Power Ultrasound on Yield of Proteins and Specialized Plant Metabolites from Sugar Beet Leaves (Beta vulgaris subsp. vulgaris var. altissima). Applied Sciences (Switzerland), 2022. 12(18).

- Kant, R. and A. Kumar, Review on essential oil extraction from aromatic and medicinal plants: Techniques, performance and economic analysis. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy, 2022. 30(August): p. 100829-100829. [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, H.S., D.K.Y. Putri, I. Triesty and M. Mahfud, Comparison of microwave hydrodistillation and solvent-free microwave extraction for extraction of agarwood oil. Chiang Mai Journal of Science, 2019. 46(4): p. 741-755.

- Ranjitha, K., K.S. Shivashankara, D.V. Sudhakar Rao, H.S. Oberoi, T.K. Roy and H. Bharathamma, Improvement in shelf life of minimally processed cilantro leaves through integration of kinetin pretreatment and packaging interventions: Studies on microbial population dynamics, biochemical characteristics and flavour retention. Food Chemistry, 2017. 221: p. 844-854. [CrossRef]

- Rivera, C.S., D. Blanco, P. Marco, R. Oria and M.E. Venturini, Effects of electron-beam irradiation on the shelf life, microbial populations and sensory characteristics of summer truffles (Tuber aestivum) packaged under modified atmospheres. Food Microbiology, 2011. 28(1): p. 141-148. [CrossRef]

- Ouf, S.A. and E.M. Ali, Does the treatment of dried herbs with ozone as a fungal decontaminating agent affect the active constituents? Environmental Pollution, 2021. 277: p. 116715-116715.

- Karam, L., T. Salloum, R. El Hage, H. Hassan and H.F. Hassan, How can packaging, source and food safety management system affect the microbiological quality of spices and dried herbs? The case of a developing country. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2021. 353(May): p. 109295-109295. [CrossRef]

- Santos, J., M. Herrero, J.A. Mendiola, M.T. Oliva-Teles, E. Ibáñez, C. Delerue-Matos and M.B.P.P. Oliveira, Fresh-cut aromatic herbs: Nutritional quality stability during shelf-life. Lwt, 2014. 59(1): p. 101-107.

- Sankat, C.K. and V. Maharaj, Shelf life of the green herb 'shado beni' (Eryngium foetidum L.) stored under refrigerated conditions. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 1996. 7(1-2): p. 109-118.

- Yousuf, B., S. Wu and M.W. Siddiqui, Incorporating essential oils or compounds derived thereof into edible coatings: Effect on quality and shelf life of fresh/fresh-cut produce. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 2021. 108(March 2020): p. 245-257. [CrossRef]

- Luo, X., W. Dessie, M. Wang, G.J. Duns, N. Rong, L. Feng, J. Zeng, Z. Qin and Y. Tan, Comprehensive utilization of residues of Magnolia officinalis based on fiber characteristics. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management, 2021. 23(2): p. 548-556. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K., J.M.S. Tomar, R. Kaushal, D.M. Kadam, A.C. Rathore, H. Mehta and P.R. Ojasvi, Aromatic plants based environmental sustainability with special reference to degraded land management. Journal of Applied Research on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, 2021. 22(January): p. 100298-100298. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L., E. Coelho, R. Madeira, P. Teixeira, I. Henriques and M.A. Coimbra, Food Ingredients Derived from Lemongrass Byproduct Hydrodistillation: Essential Oil, Hydrolate, and Decoction. Molecules, 2022. 27(8). [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, C.A., A.C.A. Sousa, D. Caramelo, F. Delgado, A.P. de Oliveira and M.R. Pastorinho, Chemical profile and eco-safety evaluation of essential oils and hydrolates from Cistus ladanifer, Helichrysum italicum, Ocimum basilicum and Thymbra capitata. Industrial Crops and Products, 2022. 175(November 2021). [CrossRef]

- de Elguea-Culebras, G.O., E.M. Bravo and R. Sánchez-Vioque, Potential sources and methodologies for the recovery of phenolic compounds from distillation residues of Mediterranean aromatic plants. An approach to the valuation of by-products of the essential oil market – A review. Industrial Crops and Products, 2022. 175(November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Zaccardelli, M., G. Roscigno, C. Pane, G. Celano, M. Di Matteo, M. Mainente, A. Vuotto, T. Mencherini, T. Esposito, A. Vitti and E. De Falco, Essential oils and quality composts sourced by recycling vegetable residues from the aromatic plant supply chain. Industrial Crops and Products, 2021. 162(January): p. 113255-113255. [CrossRef]

- Saha, A. and B.B. Basak, Scope of value addition and utilization of residual biomass from medicinal and aromatic plants. Industrial Crops and Products, 2020. 145(November 2019): p. 111979-111979. [CrossRef]

- Lesage-Meessen, L., M. Bou, C. Ginies, D. Chevret, D. Navarro, E. Drula, E. Bonnin, J.C. Del Río, E. Odinot, A. Bisotto, J.G. Berrin, J.C. Sigoillot, C.B. Faulds and A. Lomascolo, Lavender- and lavandin-distilled straws: An untapped feedstock with great potential for the production of high-added value compounds and fungal enzymes. Biotechnology for Biofuels, 2018. 11(1): p. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, A., C. Míguez, A. Iglesias and L. Saborido, Value-Added Products by Solvent Extraction and Steam Distillation from Elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.). Applied Sciences (Switzerland), 2022. 12(6). [CrossRef]

- Huang, C., Z.X. Li, Y. Wu, Z.Y. Huang, Y. Hu and J. Gao, Treatment and bioresources utilization of traditional Chinese medicinal herb residues: Recent technological advances and industrial prospect. Journal of Environmental Management, 2021. 299(9). [CrossRef]

- Truzzi, E., M.A. Chaouch, G. Rossi, L. Tagliazucchi, D. Bertelli and S. Benvenuti, Characterization and Valorization of the Agricultural Waste Obtained from Lavandula Steam Distillation for Its Reuse in the Food and Pharmaceutical Fields. Molecules, 2022. 27(5). [CrossRef]

- Hcini, K., A. Bahi, M.B. Zarroug, M.B. Farhat, A.A. Lozano-Pérez, J.L. Cenis, M. Quílez, S. Stambouli-Essassi and M.J. Jordán, Polyphenolic Profile of Tunisian Thyme (Thymbra capitata L.) Post-Distilled Residues: Evaluation of Total Phenolic Content and Phenolic Compounds and Their Contribution to Antioxidant Activity. Molecules, 2022. 27(24). [CrossRef]

- Ma, J., Y. Chen, K. Wang, Y. Huang and H. Wang, Re-utilization of Chinese medicinal herbal residues improved soil fertility and maintained maize yield under chemical fertilizer reduction. Chemosphere, 2021. 283(December 2020): p. 131262-131262. [CrossRef]

- Greff, B., A. Sáhó, E. Lakatos and L. Varga, Biocontrol Activity of Aromatic and Medicinal Plants and Their Bioactive Components against Soil-Borne Pathogens. Plants, 2023. 12(4).

- Filipović, V., V. Ugrenović, V. Popović, S. Dimitrijević, S. Popović, M. Aćimović, A. Dragumilo and L. Pezo, Productivity and flower quality of different pot marigold (Calendula officinalis L.) varieties on the compost produced from medicinal plant waste. Industrial Crops and Products, 2023. 192(December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Mascoloti, R., Â. Fernandes, T.C. Finimundy, C. Pereira, M. Jos, R.C. Calhelha, C. Canan, L. Barros, J.S. Amaral and I.C.F.R. Ferreira, resources Lovage ( Levisticum o ffi cinale W . D . J . Koch ) Roots : Circular Economy. 2020.

- Zou, X., A. Bk, T. Abu-Izneid, A. Aziz, P. Devnath, A. Rauf, S. Mitra, T.B. Emran, A.A.H. Mujawah, J.M. Lorenzo, M.S. Mubarak, P. Wilairatana and H.A.R. Suleria, Current advances of functional phytochemicals in Nicotiana plant and related potential value of tobacco processing waste: A review. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy, 2021. 143(August): p. 112191-112191. [CrossRef]

- Fehrmann, J., B. Belleville and B. Ozarska, Effects of Particle Dimension and Constituent Proportions on Internal Bond Strength of Ultra-Low-Density Hemp Hurd Particleboard. Forests, 2022. 13(11). [CrossRef]

- Robertson, K.J., R. Brar, P. Randhawa, C. Stark and S. Baroutian, Opportunities and challenges in waste management within the medicinal cannabis sector. Industrial Crops and Products, 2023. 197(March): p. 116639-116639. [CrossRef]

- Dziedziński, M., J. Kobus-Cisowska and B. Stachowiak, Pinus species as prospective reserves of bioactive compounds with potential use in functional food—current state of knowledge. Plants, 2021. 10(7). [CrossRef]

| Species | Nº of weeks after planting date |

|---|---|

| Parsley (Petroselinum crispum) | 9 |

| Dill (Anethum graveolens) | 14 |

| Coriander (Coriandrum sativum) | 3 |

| Peppermint (Mentha × piperita) | 6 |

| Species | Ingredients | MCf (%) |

| Althaea officinalis L. | Raízes | 10 |

| Arnica montana L. | Flores | 10 |

| Calendula officinalis | Flores | 12 |

| Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) | Flores | 12 |

| Coriander | Sementes | 10 |

| Fennel | Sementes | 8 |

| Hypericum perforatum | Ervas | 10 |

| Lovage | Folhas | 12 |

| Malva sylvestris | Folhas | 12 |

| Lemon balm | Folhas | 10 |

| Peppermint | Folhas | 11 |

| Plantago lanceolata | Erva | 10 |

| Valerian | Raízes | 12 |

| Verbascum phlomoides | Erva | 12 |

| Species | Drying Temperature (°C) | MCf (%) | Air Speed (m/s) |

| Echinacea (Echinacea Angustifolia) | 50 | 0 | |

| Bay leaf | 60 | 10 | 15 |

| Andrographic | 7 | ||

| Spearmint (Mentha x villosa Huds) | 50 | 0 | |

| Ginger | 47.2 | 10 | |

| Pistachio | 21.32 | 0.8 | |

| Coconut copra | 7.8 | ||

| Hibiscus | 32.24 | 9.2 | |

| Gourd | 9 | ||

| Garlic | 55-75 | 6.5 | 0.2 |

| Pepper | 55, 60 e 70 | 10 | 1.5 |

| Turmeric (Curcuma zeduaria) | 6.86 | ||

| Spinach | 230 | ||

| Pear | 50-60 | ||

| Bitter orange (Citrus Aurantium) | 50-60 | ||

| Tarragon | 60 | 10 | |

| Longan | 31-58 | ||

| Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) | 45 ± 5 | ||

| Cymbopogon nardus | 60 | ||

| Cymbopogon citratus | 40 | ||

| Summer savory | 45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).