Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

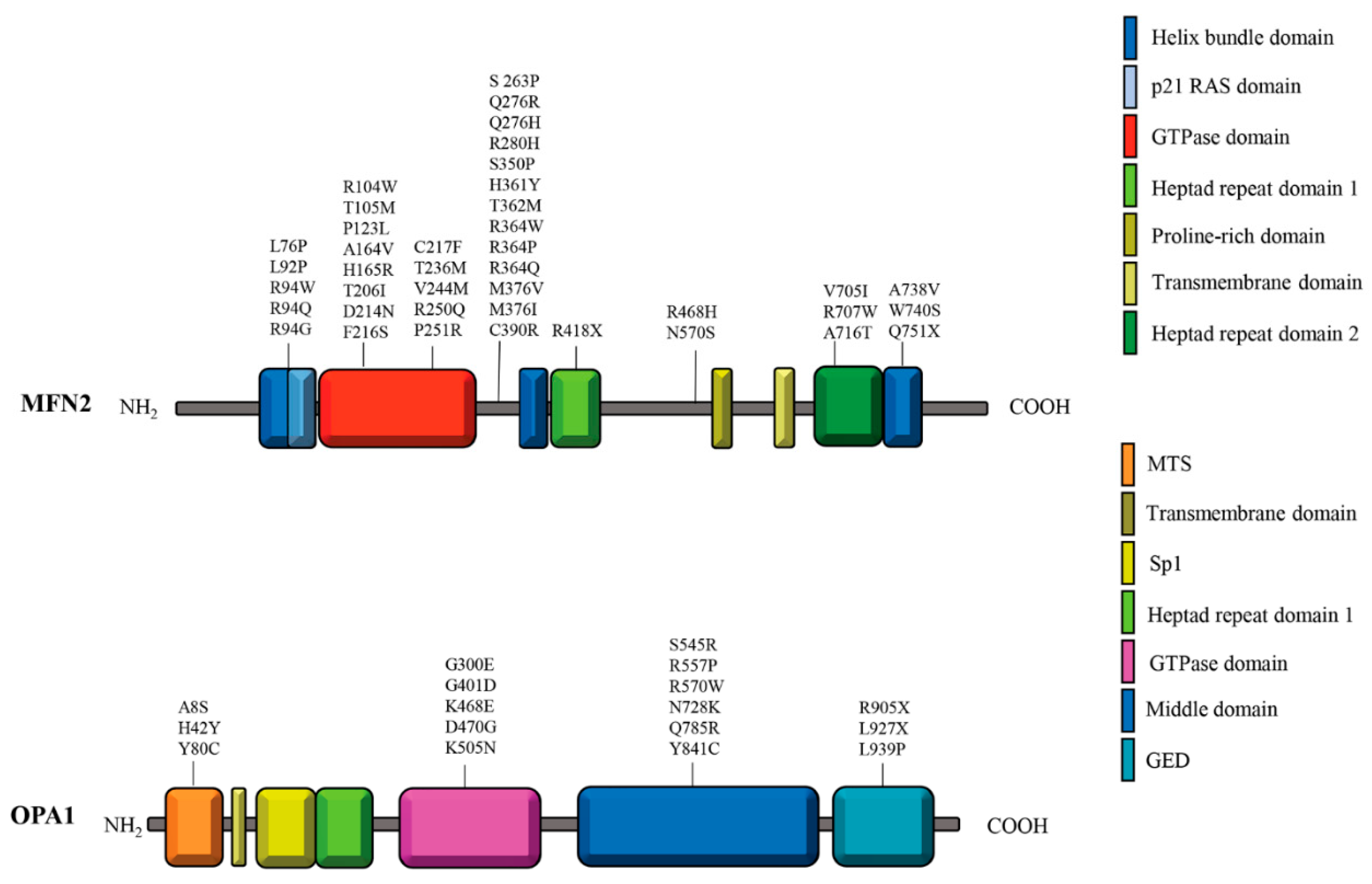

2. Structural insights into MFN2 and OPA1

3. MFN2 and OPA1 in the Mitochondrial Fusion Process

4. Mitochondrial Fusion Proteins in the Regulation of Oxidative Phosphorylation

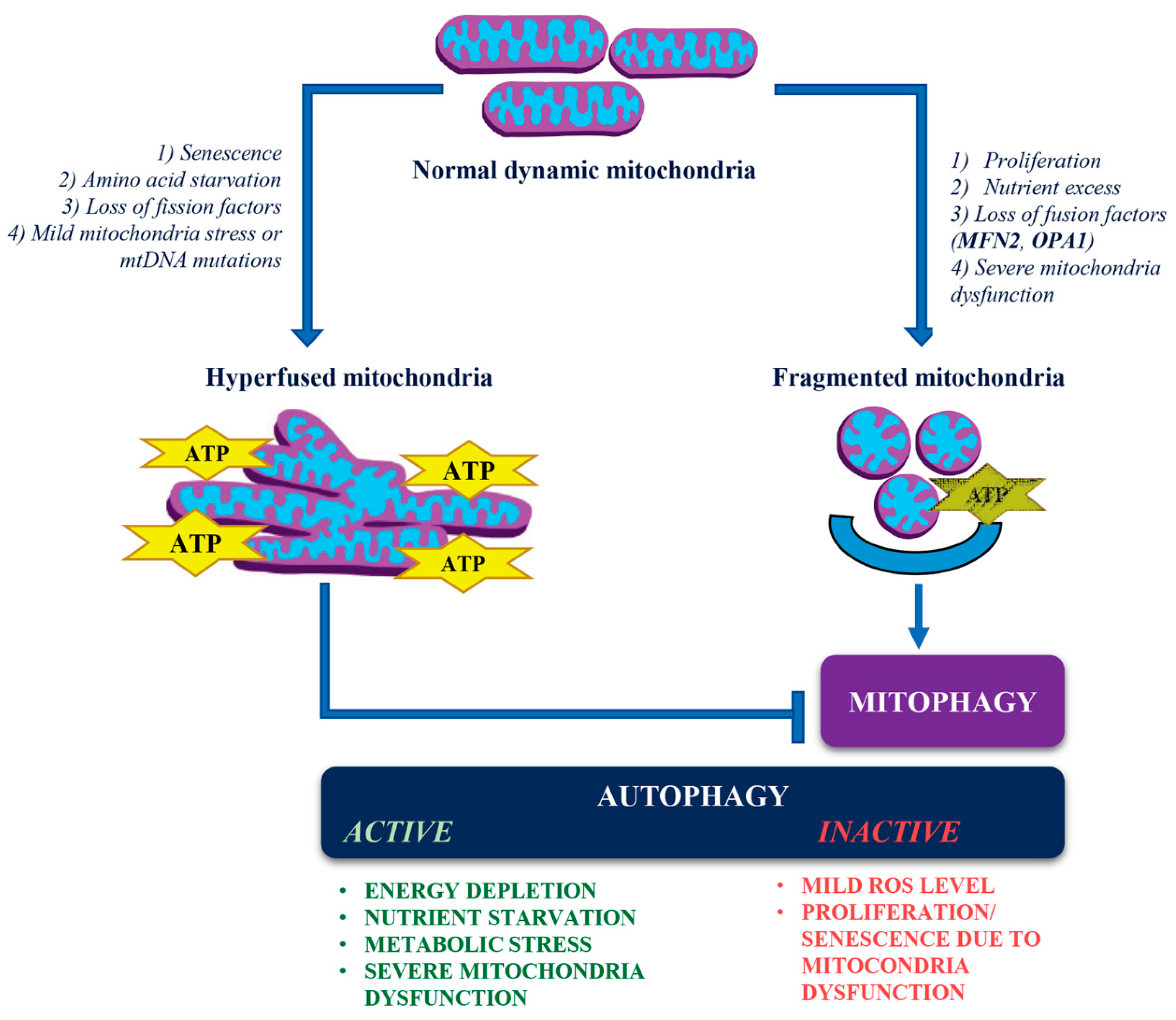

5. Dynamic Changes in Mitochondrial Structure and Quality Control

6. Autophagy/Mitophagy and Mitochondrial Dynamics

7. Metabolic Cues Driving Mitochondrial Fusion

8. Mitochondrial Dynamics in Neuronal Differentiation and Bioenergetics

9. Pathological Implications of MFN2 and OPA1 Mutations

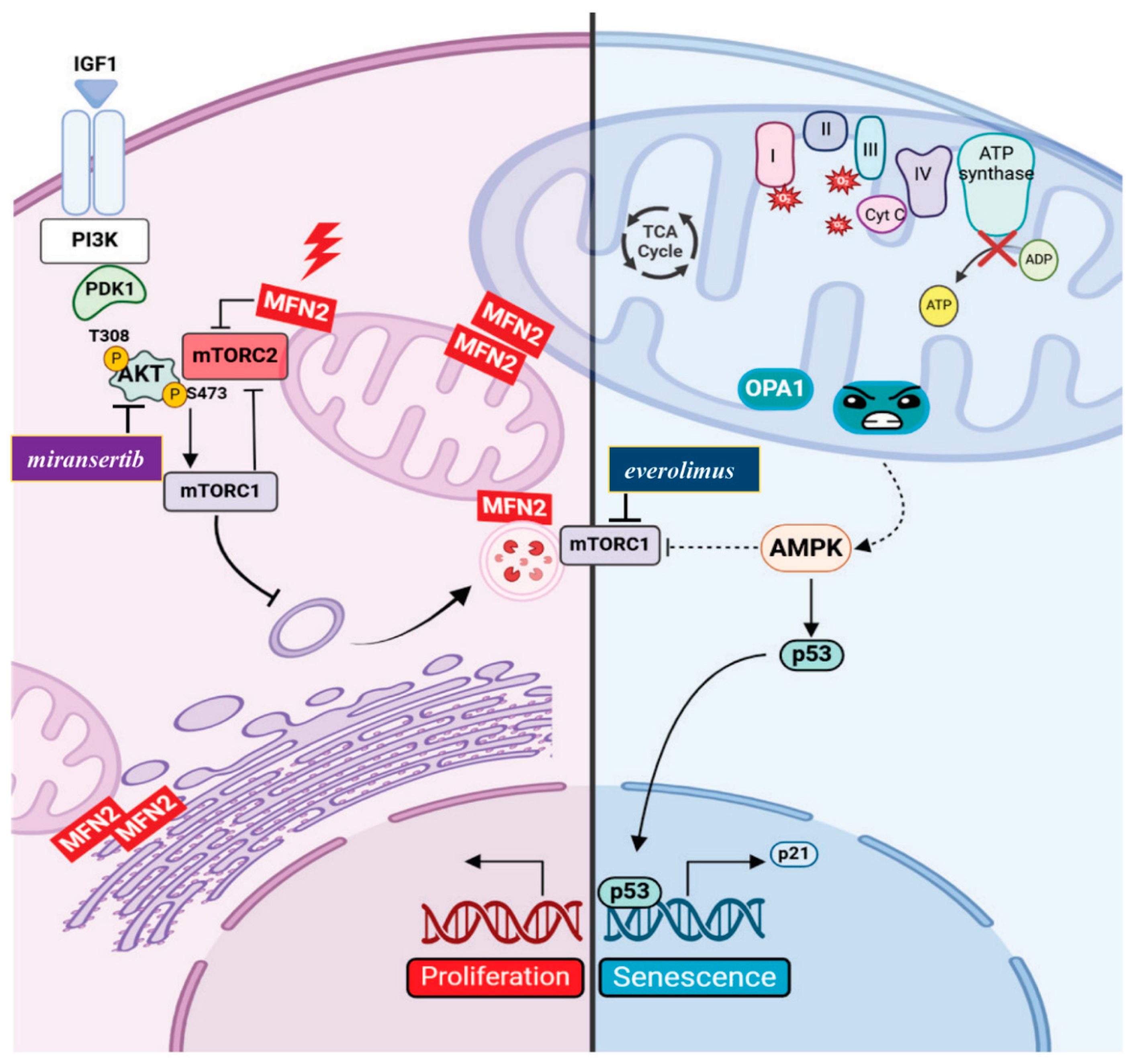

10. Distinct Cellular Outcomes of MFN2 and OPA1 Mutations

11. Concluding Remarks

-

Mitochondrial Hyperfusion:

- -

- Triggered by cellular senescence, amino acid starvation, loss of fission factors, mild mitochondrial stress, or mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations.

- -

- Supports oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) and ATP production.

- -

- Prevents autophagic clearance of damaged mitochondria by mitophagy despite cellular stressors.

-

Mitochondrial Fragmentation:

- -

- Induced by cellular proliferation, nutrient excess, loss of fusion factors (like MFN2 and OPA1), and severe mitochondrial dysfunction.

- -

- Promotes selective autophagic clearance (mitophagy) of dysfunctional mitochondria.

- 3.

-

Autophagy Regulation:

- -

- There are instances when, despite mitochondrial fragmentation, autophagy may not be activated, particularly in contexts such as cell proliferation (as seen in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A) or premature senescence (observed in Autosomal Dominant Optic Atrophy).

- -

- Under mild oxidative stress, mitophagy is activated; however, the induction of non-selective autophagy may not occur simultaneously.

12. Future Directions

- Could the proliferative changes observed in CMT2A2 fibroblasts and cancer models of MFN2 dysfunction also occur in neuronal stem cells affected by CMT2A?

- Does senescence caused by OPA1 deficiency directly contribute to neurodegeneration in ADOA, and is this related to impaired autophagy?

- How does metabolic reprogramming influence the progression of mitochondrial diseases, and can interventions be implemented to restore the balance of autophagy and mitophagy?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liesa, M.; Shirihai, O.S. Mitochondrial Dynamics in the Regulation of Nutrient Utilization and Energy Expenditure. 2013, 17, 491–506. [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Chen, G.; Li, W.; Kepp, O.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Q. Mitophagy, Mitochondrial Homeostasis, and Cell Fate. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 467. [CrossRef]

- Pernas, L.; Scorrano, L. Mito-Morphosis: Mitochondrial Fusion, Fission, and Cristae Remodeling as Key Mediators of Cellular Function. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2016, 78, 505–531. [CrossRef]

- Santel, A.; Fuller, M.T. Control of mitochondrial morphology by a human mitofusin. J. Cell Sci. 2001, 114, 867–874. [CrossRef]

- Knott, A.B.; Perkins, G.; Schwarzenbacher, R.; Bossy-Wetzel, E. Mitochondrial fragmentation in neurodegeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008, 9, 505–518. [CrossRef]

- Giacomello, M.; Pyakurel, A.; Glytsou, C.; Scorrano, L. The cell biology of mitochondrial membrane dynamics. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 204–224. [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.C. Mitochondrial Fusion and Fission in Mammals. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2006, 22, 79–99. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L. C.; Scorrano, L. Mitochondrial Morphology in Mitophagy and Macroautophagy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 2013, 1833 (1), 205–212. [CrossRef]

- Schrepfer, E.; Scorrano, L. Mitofusins, from Mitochondria to Metabolism. Molecular Cell 2016, 61 (5), 683–694. [CrossRef]

- Filadi, R.; Pendin, D.; Pizzo, P. Mitofusin 2: from functions to disease. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Gilkerson, R.; De La Torre, P.; Vallier, S.S. Mitochondrial OMA1 and OPA1 as Gatekeepers of Organellar Structure/Function and Cellular Stress Response. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Rojo, M.; Legros, F.; Chateau, D.; Lombès, A. Membrane topology and mitochondrial targeting of mitofusins, ubiquitous mammalian homologs of the transmembrane GTPase Fzo. J. Cell Sci. 2002, 115, 1663–1674. [CrossRef]

- Chandhok, G.; Lazarou, M.; Neumann, B. Structure, Function, and Regulation of Mitofusin-2 in Health and Disease. Biological Reviews 2018, 93 (2), 933–949. [CrossRef]

- Bourne, H.R.; Sanders, D.A.; McCormick, F. The GTPase superfamily: a conserved switch for diverse cell functions. Nature 1990, 348, 125–132. [CrossRef]

- Bourne, H.R.; Sanders, D.A.; McCormick, F. The GTPase superfamily: conserved structure and molecular mechanism. Nature 1991, 349, 117–127. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.C.; Detmer, S.A.; Ewald, A.J.; Griffin, E.E.; Fraser, S.E.; Chan, D.C. Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 160, 189–200. [CrossRef]

- Koshiba, T.; Detmer, S.A.; Kaiser, J.T.; Chen, H.; McCaffery, J.M.; Chan, D.C. Structural Basis of Mitochondrial Tethering by Mitofusin Complexes. Science 2004, 305, 858–862. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.-H.; Guo, X.; Ma, D.; Guo, Y.; Li, Q.; Yang, D.; Li, P.; Qiu, X.; Wen, S.; Xiao, R.-P.; et al. Dysregulation of HSG triggers vascular proliferative disorders. Nat. Cell Biol. 2004, 6, 872–883. [CrossRef]

- Eura, Y.; Ishihara, N.; Yokota, S.; Mihara, K. Two Mitofusin Proteins, Mammalian Homologues of FZO, with Distinct Functions Are Both Required for Mitochondrial Fusion. J. Biochem. 2003, 134, 333–344. [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, N.; Fujita, Y.; Oka, T.; Mihara, K. Regulation of mitochondrial morphology through proteolytic cleavage of OPA1. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 2966–2977. [CrossRef]

- Amati-Bonneau, P.; Milea, D.; Bonneau, D.; Chevrollier, A.; Ferré, M.; Guillet, V.; Gueguen, N.; Loiseau, D.; Crescenzo, M.-A. P. D.; Verny, C.; Procaccio, V.; Lenaers, G.; Reynier, P. OPA1-Associated Disorders: Phenotypes and Pathophysiology. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 2009, 41 (10), 1855–1865. [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.J.; Lampe, P.A.; Stojanovski, D.; Korwitz, A.; Anand, R.; Tatsuta, T.; Langer, T. Stress-induced OMA1 activation and autocatalytic turnover regulate OPA1-dependent mitochondrial dynamics. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 578–593. [CrossRef]

- Anand, R.; Wai, T.; Baker, M.J.; Kladt, N.; Schauss, A.C.; Rugarli, E.; Langer, T. The i-AAA protease YME1L and OMA1 cleave OPA1 to balance mitochondrial fusion and fission. J. Cell Biol. 2014, 204, 919–929. [CrossRef]

- Van Der Bliek, A. M.; Shen, Q.; Kawajiri, S. Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Fission and Fusion. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2013, 5 (6), a011072–a011072. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-J.; Cao, Y.-L.; Feng, J.-X.; Qi, Y.; Meng, S.; Yang, J.-F.; Zhong, Y.-T.; Kang, S.; Chen, X.; Lan, L.; et al. Structural insights of human mitofusin-2 into mitochondrial fusion and CMT2A onset. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Qi, Y.; Huang, X.; Yu, C.; Lan, L.; Guo, X.; Rao, Z.; Hu, J.; Lou, Z. Structural basis for GTP hydrolysis and conformational change of MFN1 in mediating membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2018, 25, 233–243. [CrossRef]

- Mattie, S.; Riemer, J.; Wideman, J.G.; McBride, H.M. A new mitofusin topology places the redox-regulated C terminus in the mitochondrial intermembrane space. J. Cell Biol. 2017, 217, 507–515. [CrossRef]

- Duvezin-Caubet, S.; Jagasia, R.; Wagener, J.; Hofmann, S.; Trifunovic, A.; Hansson, A.; Chomyn, A.; Bauer, M.F.; Attardi, G.; Larsson, N.-G.; et al. Proteolytic Processing of OPA1 Links Mitochondrial Dysfunction to Alterations in Mitochondrial Morphology. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 37972–37979. [CrossRef]

- Brandt, T.; Cavellini, L.; Kühlbrandt, W.; Cohen, M.M. A mitofusin-dependent docking ring complex triggers mitochondrial fusion in vitro. eLife 2016, 5. [CrossRef]

- Twig, G.; Elorza, A.; Molina, A.J.A.; Mohamed, H.; Wikstrom, J.D.; Walzer, G.; Stiles, L.; Haigh, S.E.; Katz, S.; Las, G.; et al. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. EMBO J. 2008, 27, 433–446. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Vermulst, M.; Wang, Y.E.; Chomyn, A.; Prolla, T.A.; McCaffery, J.M.; Chan, D.C. Mitochondrial Fusion Is Required for mtDNA Stability in Skeletal Muscle and Tolerance of mtDNA Mutations. Cell 2010, 141, 280–289. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chan, D.C. Physiological functions of mitochondrial fusion. Ann. New York Acad. Sci. 2010, 1201, 21–25. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Nuevo, A.; Díaz-Ramos, A.; Noguera, E.; Díaz-Sáez, F.; Duran, X.; Muñoz, J.P.; Romero, M.; Plana, N.; Sebastián, D.; Tezze, C.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA and TLR9 drive muscle inflammation upon Opa1 deficiency. EMBO J. 2018, 37, e96553. [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.-H.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Kung, C.-P.; Weber, J.D.; Patti, G.J. Mitochondrial fusion supports increased oxidative phosphorylation during cell proliferation. eLife 2019, 8, e41351. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.C.; Di Benedetto, G.; Scorrano, L. During autophagy mitochondria elongate, are spared from degradation and sustain cell viability. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011, 13, 589–598. [CrossRef]

- Molina, A.J.; Wikstrom, J.D.; Stiles, L.; Las, G.; Mohamed, H.; Elorza, A.; Walzer, G.; Twig, G.; Katz, S.; Corkey, B.E.; et al. Mitochondrial Networking Protects β-Cells From Nutrient-Induced Apoptosis. Diabetes 2009, 58, 2303–2315. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial dynamics in health and disease: mechanisms and potential targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Jheng, H.-F.; Tsai, P.-J.; Guo, S.-M.; Kuo, L.-H.; Chang, C.-S.; Su, I.-J.; Chang, C.-R.; Tsai, Y.-S. Mitochondrial Fission Contributes to Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Insulin Resistance in Skeletal Muscle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012, 32, 309–319. [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.W.; Fung, T.S.; Baker, D.C.; Saoi, M.; Park, J.; Febres-Aldana, C.A.; Aly, R.G.; Cui, R.; Sharma, A.; Fu, Y.; et al. Cellular ATP demand creates metabolically distinct subpopulations of mitochondria. Nature 2024, 635, 746–754. [CrossRef]

- De Brito, O. M.; Scorrano, L. Mitofusin 2 Tethers Endoplasmic Reticulum to Mitochondria. Nature 2008, 456 (7222), 605–610. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Alvarez, M.I.; Sebastián, D.; Vives, S.; Ivanova, S.; Bartoccioni, P.; Kakimoto, P.; Plana, N.; Veiga, S.R.; Hernández, V.; Vasconcelos, N.; et al. Deficient Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondrial Phosphatidylserine Transfer Causes Liver Disease. Cell 2019, 177, 881–895.e17. [CrossRef]

- Zorzano, A.; Hernández-Alvarez, M.I.; Sebastián, D.; Muñoz, J.P. Mitofusin 2 as a Driver That Controls Energy Metabolism and Insulin Signaling. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2015, 22, 1020–1031. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, R.J.; Malhotra, J.D. Calcium trafficking integrates endoplasmic reticulum function with mitochondrial bioenergetics. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Res. 2014, 1843, 2233–2239. [CrossRef]

- Whitaker-Menezes, D.; Martinez-Outschoorn, U. E.; Flomenberg, N.; Birbe, R.; Witkiewicz, A. K.; Howell, A.; Pavlides, S.; Tsirigos, A.; Ertel, A.; Pestell, R. G.; Broda, P.; Minetti, C.; Lisanti, M. P.; Sotgia, F. Hyperactivation of Oxidative Mitochondrial Metabolism in Epithelial Cancer Cells in Situ: Visualizing the Therapeutic Effects of Metformin in Tumor Tissue. Cell Cycle 2011, 10 (23), 4047–4064. [CrossRef]

- Naon, D.; Zaninello, M.; Giacomello, M.; Varanita, T.; Grespi, F.; Lakshminaranayan, S.; Serafini, A.; Semenzato, M.; Herkenne, S.; Hernández-Alvarez, M.I.; et al. Critical reappraisal confirms that Mitofusin 2 is an endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria tether. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 11249–11254. [CrossRef]

- Filadi, R.; Greotti, E.; Turacchio, G.; Luini, A.; Pozzan, T.; Pizzo, P. Mitofusin 2 ablation increases endoplasmic reticulum–mitochondria coupling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E2174–E2181. [CrossRef]

- Naon, D.; Scorrano, L. At the right distance: ER-mitochondria juxtaposition in cell life and death. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Res. 2014, 1843, 2184–2194. [CrossRef]

- Filadi, R.; Theurey, P.; Pizzo, P. The endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria coupling in health and disease: Molecules, functions and significance. Cell Calcium 2017, 62, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-Y.; Sheng, Z.-H. Regulation of mitochondrial transport in neurons. Exp. Cell Res. 2015, 334, 35–44. [CrossRef]

- Misko, A.; Jiang, S.; Wegorzewska, I.; Milbrandt, J.; Baloh, R.H. Mitofusin 2 Is Necessary for Transport of Axonal Mitochondria and Interacts with the Miro/Milton Complex. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 4232–4240. [CrossRef]

- Mou, Y.; Dein, J.; Chen, Z.; Jagdale, M.; Li, X.-J. MFN2 Deficiency Impairs Mitochondrial Transport and Downregulates Motor Protein Expression in Human Spinal Motor Neurons. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2021, 14. [CrossRef]

- Lapuente-Brun, E.; Moreno-Loshuertos, R.; Acín-Pérez, R.; Latorre-Pellicer, A.; Colás, C.; Balsa, E.; Perales-Clemente, E.; Quirós, P.M.; Calvo, E.; Rodríguez-Hernández, M.A.; et al. Supercomplex Assembly Determines Electron Flux in the Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain. Science 2013, 340, 1567–1570. [CrossRef]

- Cogliati, S.; Frezza, C.; Soriano, M.E.; Varanita, T.; Quintana-Cabrera, R.; Corrado, M.; Cipolat, S.; Costa, V.; Casarin, A.; Gomes, L.C.; et al. Mitochondrial Cristae Shape Determines Respiratory Chain Supercomplexes Assembly and Respiratory Efficiency. 2013, 155, 160–171. [CrossRef]

- A Patten, D.; Wong, J.; Khacho, M.; Soubannier, V.; Mailloux, R.J.; Pilon-Larose, K.; MacLaurin, J.G.; Park, D.S.; McBride, H.M.; Trinkle-Mulcahy, L.; et al. OPA1-dependent cristae modulation is essential for cellular adaptation to metabolic demand. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 2676–2691. [CrossRef]

- Eisner, V.; Picard, M.; Hajnóczky, G. Mitochondrial dynamics in adaptive and maladaptive cellular stress responses. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 755–765. [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, M.; Singh, S.; Singh, A.P.; Dasgupta, S. Mitochondrial fusion and fission: The fine-tune balance for cellular homeostasis. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21620–e21620. [CrossRef]

- Westermann, B. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in cell life and death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 872–884. [CrossRef]

- Pickles, S.; Vigié, P.; Youle, R.J. Mitophagy and Quality Control Mechanisms in Mitochondrial Maintenance. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, R170–R185. [CrossRef]

- Mottis, A.; Jovaisaite, V.; Auwerx, J. The mitochondrial unfolded protein response in mammalian physiology. Mamm. Genome 2014, 25, 424–433. [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Evans, R. PPARs and ERRs: molecular mediators of mitochondrial metabolism. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015, 33, 49–54. [CrossRef]

- Cardamone, M.D.; Tanasa, B.; Cederquist, C.T.; Huang, J.; Mahdaviani, K.; Li, W.; Rosenfeld, M.G.; Liesa, M.; Perissi, V. Mitochondrial Retrograde Signaling in Mammals Is Mediated by the Transcriptional Cofactor GPS2 via Direct Mitochondria-to-Nucleus Translocation. Mol. Cell 2018, 69, 757–772.e7. [CrossRef]

- Hock, M.B.; Kralli, A. Transcriptional Control of Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Function. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2009, 71, 177–203. [CrossRef]

- Scarpulla, R.C.; Vega, R.B.; Kelly, D.P. Transcriptional integration of mitochondrial biogenesis. 2012, 23, 459–466. [CrossRef]

- Finley, L.W.; Haigis, M.C. The coordination of nuclear and mitochondrial communication during aging and calorie restriction. 2009, 8, 173–188. [CrossRef]

- Guha, M.; Avadhani, N.G. Mitochondrial retrograde signaling at the crossroads of tumor bioenergetics, genetics and epigenetics. Mitochondrion 2013, 13, 577–591. [CrossRef]

- Bohovych, I.; Khalimonchuk, O. Sending Out an SOS: Mitochondria as a Signaling Hub. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 4, 109. [CrossRef]

- Chandel, N.S. Evolution of Mitochondria as Signaling Organelles. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 204–206. [CrossRef]

- Butow, R. A.; Avadhani, N. G. Mitochondrial Signaling. Molecular Cell 2004, 14 (1), 1–15.

- Liu, Z.; Butow, R.A. Mitochondrial Retrograde Signaling. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2006, 40, 159–185. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.C.; Di Benedetto, G.; Scorrano, L. Essential amino acids and glutamine regulate induction of mitochondrial elongation during autophagy. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 2635–2639. [CrossRef]

- Tondera, D.; Grandemange, S.; Jourdain, A.; Karbowski, M.; Mattenberger, Y.; Herzig, S.; Da Cruz, S.; Clerc, P.; Raschke, I.; Merkwirth, C.; et al. SLP-2 is required for stress-induced mitochondrial hyperfusion. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 1589–1600. [CrossRef]

- Tezze, C.; Romanello, V.; Desbats, M.A.; Fadini, G.P.; Albiero, M.; Favaro, G.; Ciciliot, S.; Soriano, M.E.; Morbidoni, V.; Cerqua, C.; et al. Age-Associated Loss of OPA1 in Muscle Impacts Muscle Mass, Metabolic Homeostasis, Systemic Inflammation, and Epithelial Senescence. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 1374–1389.e6. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.; Galloway, C. A.; Jhun, B. S.; Yu, T. Mitochondrial Dynamics in Diabetes. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2011, 14 (3), 439–457.

- Yoon, Y.; Yu, T.; Wang, L. Morphological control of mitochondrial bioenergetics. Front. Biosci. 2015, 20, 229–246. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Smith, S.B.; Yoon, Y. The short variant of the mitochondrial dynamin OPA1 maintains mitochondrial energetics and cristae structure. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 7115–7130. [CrossRef]

- Sessions, D.T.; Kim, K.-B.; Kashatus, J.A.; Churchill, N.; Park, K.-S.; Mayo, M.W.; Sesaki, H.; Kashatus, D.F. Opa1 and Drp1 reciprocally regulate cristae morphology, ETC function, and NAD+ regeneration in KRas-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 111818–111818. [CrossRef]

- Frezza, C.; Cipolat, S.; de Brito, O.M.; Micaroni, M.; Beznoussenko, G.V.; Rudka, T.; Bartoli, D.; Polishuck, R.S.; Danial, N.N.; De Strooper, B.; et al. OPA1 Controls Apoptotic Cristae Remodeling Independently from Mitochondrial Fusion. Cell 2006, 126, 177–189. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Z.; Li, Y.; Fu, R.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Cui, H.; et al. ROS-mediated activation and mitochondrial translocation of CaMKII contributes to Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission and apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer cells by isorhamnetin and chloroquine. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Zorov, D.B.; Juhaszova, M.; Sollott, S.J. Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and ROS-Induced ROS Release. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 909–950. [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, G.R.; Hardie, D.G. New insights into activation and function of the AMPK. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 255–272. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.-J.; Koju, N.; Sheng, R. Mammalian integrated stress responses in stressed organelles and their functions. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2024, 45, 1095–1114. [CrossRef]

- Shackelford, D.B.; Shaw, R.J. The LKB1–AMPK pathway: metabolism and growth control in tumour suppression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 563–575. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Qiang, L.; Joseph, J.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Viollet, B.; He, Y.-Y. Mitochondrial dysfunction activates the AMPK signaling and autophagy to promote cell survival. Genes Dis. 2016, 3, 82–87. [CrossRef]

- Rambold, A.S.; Kostelecky, B.; Elia, N.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J. Tubular network formation protects mitochondria from autophagosomal degradation during nutrient starvation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 10190–10195. [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.W.S.; Haydar, G.; Taniane, C.; Farrell, G.; Arias, I.M.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Fu, D. AMPK Activation Prevents and Reverses Drug-Induced Mitochondrial and Hepatocyte Injury by Promoting Mitochondrial Fusion and Function. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0165638. [CrossRef]

- Hoozemans, J.J.; van Haastert, E.S.; Eikelenboom, P.; de Vos, R.A.; Rozemuller, J.M.; Scheper, W. Activation of the unfolded protein response in Parkinson’s disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 354, 707–711. [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Trinh, M. A.; Wexler, A. J.; Bourbon, C.; Gatti, E.; Pierre, P.; Cavener, D. R.; Klann, E. Suppression of eIF2α Kinases Alleviates Alzheimer’s Disease–Related Plasticity and Memory Deficits. Nat Neurosci 2013, 16 (9), 1299–1305. [CrossRef]

- Millot, P.; Pujol, C.; Paquet, C.; Mouton-Liger, F. Impaired mitochondrial dynamics in the blood of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementia. Alzheimer's Dement. 2023, 19. [CrossRef]

- Bilen, M.; Benhammouda, S.; Slack, R.S.; Germain, M. The integrated stress response as a key pathway downstream of mitochondrial dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2022, 27. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.M.; Lourenco, M.V. Integrated Stress Response: Connecting ApoE4 to Memory Impairment in Alzheimer's Disease. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 1053–1055. [CrossRef]

- Shpilka, T.; Haynes, C.M. The mitochondrial UPR: mechanisms, physiological functions and implications in ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 109–120. [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Herrmann, J.M.; Becker, T. Quality control of the mitochondrial proteome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 22, 54–70. [CrossRef]

- Vannuvel, K.; Renard, P.; Raes, M.; Arnould, T. Functional and morphological impact of ER stress on mitochondria. J. Cell. Physiol. 2013, 228, 1802–1818. [CrossRef]

- Senft, D.; Ronai, Z.A. UPR, autophagy, and mitochondria crosstalk underlies the ER stress response. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 141–148. [CrossRef]

- Arnould, T.; Michel, S.; Renard, P. Mitochondria Retrograde Signaling and the UPRmt: Where Are We in Mammals? IJMS 2015, 16 (8), 18224–18251. [CrossRef]

- Nandi, D.; Tahiliani, P.; Kumar, A.; Chandu, D. The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System. J. Biosci. 2006, 31 (1), 137–155. [CrossRef]

- Grice, G.L.; Nathan, J.A. The recognition of ubiquitinated proteins by the proteasome. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3497–3506. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-C.; Kinefuchi, H.; Lei, L.; Kikuchi, R.; Yamano, K.; Youle, R.J. Mitochondrial YME1L1 governs unoccupied protein translocase channels. Nat. Cell Biol. 2025, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Jin, S. M.; Youle, R. J. The Accumulation of Misfolded Proteins in the Mitochondrial Matrix Is Sensed by PINK1 to Induce PARK2/Parkin-Mediated Mitophagy of Polarized Mitochondria. Autophagy 2013, 9 (11), 1750–1757. [CrossRef]

- Mohan, J.; Wollert, T. Human ubiquitin-like proteins as central coordinators in autophagy. Interface Focus 2018, 8, 20180025. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Jensen, L.E.; Hurley, J.H. Autophagosome biogenesis comes out of the black box. Nat. Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 450–456. [CrossRef]

- Ganley, I.G.; Simonsen, A. Diversity of mitophagy pathways at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2022, 135. [CrossRef]

- Axe, E.L.; Walker, S.A.; Manifava, M.; Chandra, P.; Roderick, H.L.; Habermann, A.; Griffiths, G.; Ktistakis, N.T. Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 182, 685–701. [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, A.; Tooze, S.A. Coordination of membrane events during autophagy by multiple class III PI3-kinase complexes. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 186, 773–782. [CrossRef]

- Markaki, M.; Tsagkari, D.; Tavernarakis, N. Mitophagy mechanisms in neuronal physiology and pathology during ageing. Biophys. Rev. 2021, 13, 955–965. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Long, H.; Hou, L.; Feng, B.; Ma, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Cai, J.; Zhang, D.-W.; Zhao, G. The mitophagy pathway and its implications in human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.M.; Lazarou, M.; Wang, C.; Kane, L.A.; Narendra, D.P.; Youle, R.J. Mitochondrial membrane potential regulates PINK1 import and proteolytic destabilization by PARL. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 191, 933–942. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, A.; Cleland, M.M.; Xu, S.; Narendra, D.P.; Suen, D.-F.; Karbowski, M.; Youle, R.J. Proteasome and p97 mediate mitophagy and degradation of mitofusins induced by Parkin. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 191, 1367–1380. [CrossRef]

- Gegg, M. E.; Cooper, J. M.; Chau, K.-Y.; Rojo, M.; Schapira, A. H. V.; Taanman, J.-W. Mitofusin 1 and Mitofusin 2 Are Ubiquitinated in a PINK1/Parkin-Dependent Manner upon Induction of Mitophagy. Human Molecular Genetics 2010, 19 (24), 4861–4870. [CrossRef]

- Ziviani, E.; Tao, R.N.; Whitworth, A.J. Drosophila Parkin requires PINK1 for mitochondrial translocation and ubiquitinates Mitofusin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 5018–5023. [CrossRef]

- Narendra, D.; Tanaka, A.; Suen, D.-F.; Youle, R.J. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 183, 795–803. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, N.; Sato, S.; Shiba, K.; Okatsu, K.; Saisho, K.; Gautier, C.A.; Sou, Y.-S.; Saiki, S.; Kawajiri, S.; Sato, F.; et al. PINK1 stabilized by mitochondrial depolarization recruits Parkin to damaged mitochondria and activates latent Parkin for mitophagy. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 189, 211–221. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M. M. J.; Leboucher, G. P.; Livnat-Levanon, N.; Glickman, M. H.; Weissman, A. M. Ubiquitin–Proteasome-Dependent Degradation of a Mitofusin, a Critical Regulator of Mitochondrial Fusion. MBoC 2008, 19 (6), 2457–2464. [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, A.; Nagashima, S.; Tokuyama, T.; Amo, T.; Matsuki, Y.; Ishido, S.; Kudo, Y.; McBride, H.M.; Fukuda, T.; Matsushita, N.; et al. MITOL Regulates Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondria Contacts via Mitofusin2. Mol. Cell 2013, 51, 20–34. [CrossRef]

- Kissová, I.; Deffieu, M.; Manon, S.; Camougrand, N. Uth1p Is Involved in the Autophagic Degradation of Mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 39068–39074. [CrossRef]

- Princely Abudu, Y.; Pankiv, S.; Mathai, B. J.; Håkon Lystad, A.; Bindesbøll, C.; Brenne, H. B.; Yoke Wui Ng, M.; Thiede, B.; Yamamoto, A.; Mutugi Nthiga, T.; Lamark, T.; Esguerra, C. V.; Johansen, T.; Simonsen, A. NIPSNAP1 and NIPSNAP2 Act as “Eat Me” Signals for Mitophagy. Developmental Cell 2019, 49 (4), 509-525.e12. [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Gao, M.; Liu, B.; Qin, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, H.; Wu, H.; Gong, G. Mitochondrial autophagy: molecular mechanisms and implications for cardiovascular disease. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tan, Z.; Zhu, C.; Li, Y.; Han, Z.; Chen, L.; Gao, R.; Liu, L.; et al. Mitophagy receptor FUNDC1 regulates mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy. Autophagy 2016, 12, 689–702. [CrossRef]

- Landes, T.; Emorine, L.J.; Courilleau, D.; Rojo, M.; Belenguer, P.; Arnauné-Pelloquin, L. The BH3-only Bnip3 binds to the dynamin Opa1 to promote mitochondrial fragmentation and apoptosis by distinct mechanisms. Embo Rep. 2010, 11, 459–465. [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, A.; McLelland, G.-L.; Fon, E.A.; McBride, H.M. A new pathway for mitochondrial quality control: Mitochondrial-derived vesicles. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 2142–2156. [CrossRef]

- Hailey, D.W.; Rambold, A.S.; Satpute-Krishnan, P.; Mitra, K.; Sougrat, R.; Kim, P.K.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J. Mitochondria Supply Membranes for Autophagosome Biogenesis during Starvation. Cell 2010, 141, 656–667. [CrossRef]

- Hamasaki, M.; Furuta, N.; Matsuda, A.; Nezu, A.; Yamamoto, A.; Fujita, N.; Oomori, H.; Noda, T.; Haraguchi, T.; Hiraoka, Y.; et al. Autophagosomes form at ER–mitochondria contact sites. Nature 2013, 495, 389–393. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Huang, X.; Han, L.; Wang, X.; Cheng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, J.; Cheng, H.; Xiao, R.; et al. Central Role of Mitofusin 2 in Autophagosome-Lysosome Fusion in Cardiomyocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 23615–23625. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X.; Zheng, M. Mitofusin 2-Deficiency Suppresses Cell Proliferation through Disturbance of Autophagy. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0121328–e0121328. [CrossRef]

- Pich, S.; Bach, D.; Briones, P.; Liesa, M.; Camps, M.; Testar, X.; Palacín, M.; Zorzano, A. The Charcot–Marie–Tooth type 2A gene product, Mfn2, up-regulates fuel oxidation through expression of OXPHOS system. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 1405–1415. [CrossRef]

- Gordaliza-Alaguero, I.; Sànchez-Fernàndez-De-Landa, P.; Radivojevikj, D.; Villarreal, L.; Arauz-Garofalo, G.; Gay, M.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; Seco, J.; Martín-Malpartida, P.; Vilaseca, M.; et al. Endogenous interactomes of MFN1 and MFN2 provide novel insights into interorganelle communication and autophagy. Autophagy 2024, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Sauvanet, C.; Duvezin-Caubet, S.; di Rago, J.-P.; Rojo, M. Energetic requirements and bioenergetic modulation of mitochondrial morphology and dynamics. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010, 21, 558–565. [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Jeyaraju, D.V.; Prudent, J.; Caron, A.; Lemieux, P.; McBride, H.M.; Laplante, M.; Tóth, K.; Pellegrini, L. A Mitofusin-2–dependent inactivating cleavage of Opa1 links changes in mitochondria cristae and ER contacts in the postprandial liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 16017–16022. [CrossRef]

- Ehses, S.; Raschke, I.; Mancuso, G.; Bernacchia, A.; Geimer, S.; Tondera, D.; Martinou, J.-C.; Westermann, B.; Rugarli, E.I.; Langer, T. Regulation of OPA1 processing and mitochondrial fusion by m-AAA protease isoenzymes and OMA1. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 187, 1023–1036. [CrossRef]

- Laplante, M.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR Signaling in Growth Control and Disease. Cell 2012, 149, 274–293. [CrossRef]

- Morita, M.; Prudent, J.; Basu, K.; Goyon, V.; Katsumura, S.; Hulea, L.; Pearl, D.; Siddiqui, N.; Strack, S.; McGuirk, S.; et al. mTOR Controls Mitochondrial Dynamics and Cell Survival via MTFP1. Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 922–935.e5. [CrossRef]

- Parra, V.; Verdejo, H. E.; Iglewski, M.; Del Campo, A.; Troncoso, R.; Jones, D.; Zhu, Y.; Kuzmicic, J.; Pennanen, C.; Lopez-Crisosto, C.; Jaña, F.; Ferreira, J.; Noguera, E.; Chiong, M.; Bernlohr, D. A.; Klip, A.; Hill, J. A.; Rothermel, B. A.; Abel, E. D.; Zorzano, A.; Lavandero, S. Insulin Stimulates Mitochondrial Fusion and Function in Cardiomyocytes via the Akt-mTOR-NFκB-Opa-1 Signaling Pathway. Diabetes 2014, 63 (1), 75–88. [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.J.; Chen, Y.; Shi, L.X.; Cheng, H.R.; Banda, I.; Ji, Y.H.; Wang, Y.T.; Li, X.M.; Mao, Y.X.; Zhang, D.F.; et al. AKT-GSK3βSignaling Pathway Regulates Mitochondrial Dysfunction-Associated OPA1 Cleavage Contributing to Osteoblast Apoptosis: Preventative Effects of Hydroxytyrosol. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Cribbs, J.T.; Strack, S. Reversible phosphorylation of Drp1 by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase and calcineurin regulates mitochondrial fission and cell death. Embo Rep. 2007, 8, 939–944. [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Henriques, M.; Joaquim, M. Mitofusins: Disease Gatekeepers and Hubs in Mitochondrial Quality Control by E3 Ligases. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 517. [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, M.; Allaman, I.; Magistretti, P.J. Brain Energy Metabolism: Focus on Astrocyte-Neuron Metabolic Cooperation. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 724–738. [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Mendez, A.; Almeida, A.; Fernández, E.; Maestre, C.; Moncada, S.; Bolaños, J.P. The bioenergetic and antioxidant status of neurons is controlled by continuous degradation of a key glycolytic enzyme by APC/C–Cdh1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 747–752. [CrossRef]

- Bittner, C.X.; Valdebenito, R.; Ruminot, I.; Loaiza, A.; Larenas, V.; Sotelo-Hitschfeld, T.; Moldenhauer, H.; Martín, A.S.; Gutiérrez, R.; Zambrano, M.; et al. Fast and Reversible Stimulation of Astrocytic Glycolysis by K+and a Delayed and Persistent Effect of Glutamate. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 4709–4713. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.W.; Kim, J.H.; Chung, M.K.; Hong, Y.J.; Jang, H.S.; Seo, B.J.; Jung, T.H.; Kim, J.S.; Chung, H.M.; Byun, S.J.; et al. Mitochondrial and Metabolic Remodeling During Reprogramming and Differentiation of the Reprogrammed Cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2015, 24, 1366–1373. [CrossRef]

- Prigione, A.; Fauler, B.; Lurz, R.; Lehrach, H.; Adjaye, J. The Senescence-Related Mitochondrial/Oxidative Stress Pathway is Repressed in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. STEM CELLS 2010, 28, 721–733. [CrossRef]

- Kasahara, A.; Cipolat, S.; Chen, Y.; Dorn, G.W.; Scorrano, L. Mitochondrial Fusion Directs Cardiomyocyte Differentiation via Calcineurin and Notch Signaling. Science 2013, 342, 734–737. [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Cui, C.; Huang, X.; Yin, X.; Li, Y.; Wen, J.; Luan, Q. MFN2 silencing promotes neural differentiation of embryonic stem cells via the Akt signaling pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 235, 1051–1064. [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Yan, S.; Yu, Q.; Chen, D.; Yan, S.S. Mfn2 is Required for Mitochondrial Development and Synapse Formation in Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells/hiPSC Derived Cortical Neurons. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31462. [CrossRef]

- Van Lent, J.; Verstraelen, P.; Asselbergh, B.; Adriaenssens, E.; Mateiu, L.; Verbist, C.; De Winter, V.; Eggermont, K.; Bosch, L.V.D.; De Vos, W.H.; et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived motor neurons of CMT type 2 patients reveal progressive mitochondrial dysfunction. Brain 2021, 144, 2471–2485. [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, L.; Scorrano, L. A cut short to death: Parl and Opa1 in the regulation of mitochondrial morphology and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2007, 14, 1275–1284. [CrossRef]

- Cogliati, S.; Enriquez, J.A.; Scorrano, L. Mitochondrial Cristae: Where Beauty Meets Functionality. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 261–273. [CrossRef]

- Youle, R. J.; Van Der Bliek, A. M. Mitochondrial Fission, Fusion, and Stress. Science 2012, 337 (6098), 1062–1065.

- Züchner, S.; De Jonghe, P.; Jordanova, A.; Claeys, K.G.; Guergueltcheva, V.; Cherninkova, S.; Hamilton, S.R.; Van Stavern, G.; Krajewski, K.M.; Stajich, J.; et al. Axonal neuropathy with optic atrophy is caused by mutations in mitofusin 2. Ann. Neurol. 2006, 59, 276–281. [CrossRef]

- Vallat, J.-M.; Ouvrier, R.A.; Pollard, J.D.; Magdelaine, C.; Zhu, D.; Nicholson, G.A.; Grew, S.; Ryan, M.M.; Funalot, B. Histopathological Findings in Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathy of Axonal Type With Onset in Early Childhood Associated WithMitofusin 2Mutations. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2008, 67, 1097–1102. [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, K. MFN2 mutation distribution and genotype/phenotype correlation in Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2. Brain 2006, 129, 2093–2102. [CrossRef]

- Baloh, R.H.; Schmidt, R.E.; Pestronk, A.; Milbrandt, J. Altered Axonal Mitochondrial Transport in the Pathogenesis of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease from Mitofusin 2 Mutations. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 422–430. [CrossRef]

- Detmer, S.A.; Chan, D.C. Complementation between mouse Mfn1 and Mfn2 protects mitochondrial fusion defects caused by CMT2A disease mutations. J. Cell Biol. 2007, 176, 405–414. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chan, D.C. Critical dependence of neurons on mitochondrial dynamics. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2006, 18, 453–459. [CrossRef]

- Feely, S.; Laura, M.; Siskind, C.; Sottile, S.; Davis, M.; Gibbons, V.; Reilly, M.; Shy, M. MFN2 mutations cause severe phenotypes in most patients with CMT2A. Neurology 2011, 76, 1690–1696. [CrossRef]

- Larrea, D.; Pera, M.; Gonnelli, A.; Quintana-Cabrera, R.; Akman, H.O.; Guardia-Laguarta, C.; Velasco, K.R.; Area-Gomez, E.; Dal Bello, F.; De Stefani, D.; et al. MFN2 mutations in Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease alter mitochondria-associated ER membrane function but do not impair bioenergetics. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, 1782–1800. [CrossRef]

- Dorn, G.W. Mitofusin 2 Dysfunction and Disease in Mice and Men. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 782. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, F.; Ronchi, D.; Salani, S.; Nizzardo, M.; Fortunato, F.; Bordoni, A.; Stuppia, G.; Del Bo, R.; Piga, D.; Fato, R.; et al. Selective mitochondrial depletion, apoptosis resistance, and increased mitophagy in human Charcot-Marie-Tooth 2A motor neurons. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 4266–4281. [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A.; Ariyoshi, M.; Okawa, Y.; Kaimoto, S.; Uchihashi, M.; Fukai, K.; Iwai-Kanai, E.; Ikeda, K.; Ueyama, T.; Ogata, T.; et al. Inhibition of p53 preserves Parkin-mediated mitophagy and pancreatic β-cell function in diabetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 3116–3121. [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.-H.; Kang, E.Y.-C.; Lin, P.-H.; Yu, B.B.-C.; Wang, J.H.-H.; Chen, V.; Wang, N.-K. Mitochondria in Retinal Ganglion Cells: Unraveling the Metabolic Nexus and Oxidative Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8626. [CrossRef]

- Carelli, V.; Musumeci, O.; Caporali, L.; Zanna, C.; La Morgia, C.; Del Dotto, V.; Porcelli, A. M.; Rugolo, M.; Valentino, M. L.; Iommarini, L.; Maresca, A.; Barboni, P.; Carbonelli, M.; Trombetta, C.; Valente, E. M.; Patergnani, S.; Giorgi, C.; Pinton, P.; Rizzo, G.; Tonon, C.; Lodi, R.; Avoni, P.; Liguori, R.; Baruzzi, A.; Toscano, A.; Zeviani, M. Syndromic Parkinsonism and Dementia Associated with OPA 1 Missense Mutations. Annals of Neurology 2015, 78 (1), 21–38. [CrossRef]

- Kane, M. S.; Alban, J.; Desquiret-Dumas, V.; Gueguen, N.; Ishak, L.; Ferre, M.; Amati-Bonneau, P.; Procaccio, V.; Bonneau, D.; Lenaers, G.; Reynier, P.; Chevrollier, A. Autophagy Controls the Pathogenicity of OPA 1 Mutations in Dominant Optic Atrophy. J Cellular Molecular Medi 2017, 21 (10), 2284–2297. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Erchova, I.; Sengpiel, F.; Votruba, M. Opa1 Deficiency Leads to Diminished Mitochondrial Bioenergetics With Compensatory Increased Mitochondrial Motility. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2020, 61, 42–42. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wu, X.; Bai, H.-X.; Wang, C.; Liu, Z.; Yang, C.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, P. OPA1 haploinsufficiency due to a novel splicing variant resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction without mitochondrial DNA depletion. Ophthalmic Genet. 2021, 42, 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Ashley, N.; Diot, A.; Morten, K.; Phadwal, K.; Williams, A.; Fearnley, I.; Rosser, L.; Lowndes, J.; Fratter, C.; et al. Dysregulated mitophagy and mitochondrial organization in optic atrophy due to OPA1 mutations. Neurology 2017, 88, 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Sarzi, E.; Angebault, C.; Seveno, M.; Gueguen, N.; Chaix, B.; Bielicki, G.; Boddaert, N.; Mausset-Bonnefont, A.-L.; Cazevieille, C.; Rigau, V.; et al. The human OPA1delTTAG mutation induces premature age-related systemic neurodegeneration in mouse. Brain 2012, 135, 3599–3613. [CrossRef]

- Diot, A.; Agnew, T.; Sanderson, J.; Liao, C.; Carver, J.; Neves, R. P. D.; Gupta, R.; Guo, Y.; Waters, C.; Seto, S.; Daniels, M. J.; Dombi, E.; Lodge, T.; Morten, K.; Williams, S. A.; Enver, T.; Iborra, F. J.; Votruba, M.; Poulton, J. Validating the RedMIT/GFP-LC3 Mouse Model by Studying Mitophagy in Autosomal Dominant Optic Atrophy Due to the OPA1Q285STOP Mutation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 103. [CrossRef]

- Zaninello, M.; Palikaras, K.; Naon, D.; Iwata, K.; Herkenne, S.; Quintana-Cabrera, R.; Semenzato, M.; Grespi, F.; Ross-Cisneros, F.N.; Carelli, V.; et al. Inhibition of autophagy curtails visual loss in a model of autosomal dominant optic atrophy. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Zaninello, M.; Palikaras, K.; Sotiriou, A.; Tavernarakis, N.; Scorrano, L. Sustained intracellular calcium rise mediates neuronal mitophagy in models of autosomal dominant optic atrophy. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 29, 167–177. [CrossRef]

- Moulis, M.F.; Millet, A.M.; Daloyau, M.; Miquel, M.-C.; Ronsin, B.; Wissinger, B.; Arnauné-Pelloquin, L.; Belenguer, P. OPA1 haploinsufficiency induces a BNIP3-dependent decrease in mitophagy in neurons: relevance to Dominant Optic Atrophy. J. Neurochem. 2017, 140, 485–494. [CrossRef]

- Hanna, R.A.; Quinsay, M.N.; Orogo, A.M.; Giang, K.; Rikka, S.; Gustafsson, Å.B. Microtubule-associated Protein 1 Light Chain 3 (LC3) Interacts with Bnip3 Protein to Selectively Remove Endoplasmic Reticulum and Mitochondria via Autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 19094–19104. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Bonamy, G.M.C.; Meeusen, S.; Brusch, R.G.; Turk, C.; Yang, P.; Schultz, P.G. A Small Molecule Promotes Mitochondrial Fusion in Mammalian Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012, 51, 9302–9305. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, B.; Wang, J.; Xu, L.; Sun, X.; Ji, K.; Yan, C.; Liu, F.; Zhao, Y. Targeting DRP1 with Mdivi-1 to correct mitochondrial abnormalities in ADOA+ syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- Szabo, A.; Sumegi, K.; Fekete, K.; Hocsak, E.; Debreceni, B.; Setalo, G.; Kovacs, K.; Deres, L.; Kengyel, A.; Kovacs, D.; et al. Activation of mitochondrial fusion provides a new treatment for mitochondria-related diseases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 150, 86–96. [CrossRef]

- Alberti, C.; Rizzo, F.; Anastasia, A.; Comi, G.; Corti, S.; Abati, E. Charcot-Marie-tooth disease type 2A: An update on pathogenesis and therapeutic perspectives. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 193, 106467. [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.S.V.; Trigano, M.; Freeman, T.; Varrichio, C.; Kandaswamy, D.K.; Newland, B.; Brancale, A.; Rozanowska, M.; Votruba, M. New avenues for therapy in mitochondrial optic neuropathies. Ther. Adv. Rare Dis. 2021, 2. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kodam, P.; Maity, S. Targeting protein interaction networks in mitochondrial dynamics for neurodegenerative diseases. J. Proteins Proteom. 2024, 15, 309–328. [CrossRef]

- Zanfardino, P.; Longo, G.; Amati, A.; Morani, F.; Picardi, E.; Girolamo, F.; Pafundi, M.; Cox, S.N.; Manzari, C.; Tullo, A.; et al. Mitofusin 2 mutation drives cell proliferation in Charcot-Marie-Tooth 2A fibroblasts. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2022, 32, 333–350. [CrossRef]

- Zanfardino, P.; Amati, A.; Petracca, E.A.; Santorelli, F.M.; Petruzzella, V. Torin1 restores proliferation rate in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A cells harbouring MFN2 (mitofusin 2) mutation. 2022, 41, 201–206. [CrossRef]

- Zanfardino, P.; Petruzzella, V. Autophagy and proliferation are dysregulated in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A cells harboring MFN2 (mitofusin 2) mutation. Autophagy Rep. 2022, 1, 537–541. [CrossRef]

- Zanfardino, P.; Amati, A.; Doccini, S.; Cox, S.N.; Tullo, A.; Longo, G.; D’erchia, A.; Picardi, E.; Nesti, C.; Santorelli, F.M.; et al. OPA1 mutation affects autophagy and triggers senescence in autosomal dominant optic atrophy plus fibroblasts. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2024, 33, 768–786. [CrossRef]

- Shimobayashi, M.; Hall, M.N. Making new contacts: the mTOR network in metabolism and signalling crosstalk. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 155–162. [CrossRef]

- Mathiassen, S.G.; De Zio, D.; Cecconi, F. Autophagy and the Cell Cycle: A Complex Landscape. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7, 51. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Chen, G.; Li, X.; Wu, X.; Chang, Z.; Xu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yin, P.; Liang, X.; Dong, L. MFN2 Suppresses Cancer Progression through Inhibition of mTORC2/Akt Signaling. Sci Rep 2017, 7 (1), 41718.

- Xue, R.; Meng, Q.; Lu, D.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Hao, J. Mitofusin2 Induces Cell Autophagy of Pancreatic Cancer through Inhibiting the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 2798070. [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Yan, L.-J.; Jana, C.K.; Das, N. Role of Catalase in Oxidative Stress- and Age-Associated Degenerative Diseases. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Balaban, R. S.; Nemoto, S.; Finkel, T. Mitochondria, Oxidants, and Aging. Cell 2005, 120 (4), 483–495.

- Han, X.; Tai, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Wei, X.; Ding, Y.; Gong, H.; Mo, C.; Zhang, J.; et al. AMPK activation protects cells from oxidative stress-induced senescence via autophagic flux restoration and intracellular NAD + elevation. Aging Cell 2016, 15, 416–427. [CrossRef]

- Tai, H.; Wang, Z.; Gong, H.; Han, X.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Wei, X.; Ding, Y.; Huang, N.; Qin, J.; et al. Autophagy impairment with lysosomal and mitochondrial dysfunction is an important characteristic of oxidative stress-induced senescence. Autophagy 2016, 13, 99–113. [CrossRef]

- Kazyken, D.; Magnuson, B.; Bodur, C.; Acosta-Jaquez, H.A.; Zhang, D.; Tong, X.; Barnes, T.M.; Steinl, G.K.; Patterson, N.E.; Altheim, C.H.; et al. AMPK directly activates mTORC2 to promote cell survival during acute energetic stress. Sci. Signal. 2019, 12. [CrossRef]

- Romanello, V.; Scalabrin, M.; Albiero, M.; Blaauw, B.; Scorrano, L.; Sandri, M. Inhibition of the Fission Machinery Mitigates OPA1 Impairment in Adult Skeletal Muscles. Cells 2019, 8, 597. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jeong, S.-Y.; Lim, W.-C.; Kim, S.; Park, Y.-Y.; Sun, X.; Youle, R.J.; Cho, H. Mitochondrial Fission and Fusion Mediators, hFis1 and OPA1, Modulate Cellular Senescence. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 22977–22983. [CrossRef]

- Stab, B.R.; Martinez, L.; Grismaldo, A.; Lerma, A.; Gutiérrez, M.L.; Barrera, L.A.; Sutachan, J.J.; Albarracín, S.L. Mitochondrial Functional Changes Characterization in Young and Senescent Human Adipose Derived MSCs. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 299. [CrossRef]

- Navratil, M.; Terman, A.; Arriaga, E.A. Giant mitochondria do not fuse and exchange their contents with normal mitochondria. Exp. Cell Res. 2008, 314, 164–172. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia-Kiššová, I.; Camougrand, N. Mitophagy is not induced by mitochondrial damage but plays a role in the regulation of cellular autophagic activity. Autophagy 2013, 9, 1897–1899. [CrossRef]

- Eskelinen, E.-L. Maturation of Autophagic Vacuoles in Mammalian Cells. Autophagy 2005, 1, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Morán, M.; Delmiro, A.; Blázquez, A.; Ugalde, C.; Arenas, J.; Martín, M. A. Bulk Autophagy, but Not Mitophagy, Is Increased in Cellular Model of Mitochondrial Disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2014, 1842 (7), 1059–1070. [CrossRef]

- Deffieu, M.; Bhatia-Kiššová, I.; Salin, B.; Klionsky, D.J.; Pinson, B.; Manon, S.; Camougrand, N. Increased levels of reduced cytochrome b and mitophagy components are required to trigger nonspecific autophagy following induced mitochondrial dysfunction. J. Cell Sci. 2013, 126, 415–426. [CrossRef]

- Frank, M.; Duvezin-Caubet, S.; Koob, S.; Occhipinti, A.; Jagasia, R.; Petcherski, A.; Ruonala, M.O.; Priault, M.; Salin, B.; Reichert, A.S. Mitophagy is triggered by mild oxidative stress in a mitochondrial fission dependent manner. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Res. 2012, 1823, 2297–2310. [CrossRef]

| Cell Type | MFN2 mutation | Remarks | References |

| Skin fibroblasts from patients with CMT2A | 1) P123L 2) L92P |

1) Mitochondrial fragmentation and abnormal mitochondrial accumulation around the nucleus 2) Mitochondrial fragmentation |

Verhoeven K. et al., 2006 |

| Skin fibroblasts from 4 patients with CMT2A2 | M21V R364Q A166T |

Reduced cellular respiration: uncoupling causing decreased ATP/O Reduced ΔѰm |

Loiseau D. et al., 2007 |

| Skin fibroblasts from patients with CMT2A | T105M I213T V273G |

Mitochondrial morphology, mtDNA integrity and and respiratory enzyme activities are unchanged Extensive mitochondrial fusion |

Amiott E. A. et al., 2008 |

| Skin fibroblasts from patients with CMT2A | p.D210V | Respiratory chain defects Multiple mtDNA deletions Defect in mtDNA damage repair system Fragmentation of the mitochondrial network |

Rouzier C. et al., 2012 |

| Skin fibroblasts derived from 4 patients with CMT2A | M376V R707P V226_S229del Q74R |

Mitochondrial respiratory chain dysfunction Decreased mtDNA copy number High levels of mtDNA depletion |

Vielhaber S. et al., 2013 |

| Motor neurons derived from iPSCs of patients with CMT2A | R364W | Reduced mitochondrial trafficking with slower anterograde and retrograde velocities along axons. Electrophysiological impairments including increased excitability, higher sodium current density, and reduced inactivation of voltage-dependent sodium and calcium channel |

Saporta et al., 2015 |

| Motor neurons derived from iPSCs of patients with CMT2A |

A383V | Decreased respiratory chain activity: complexes II and III Reduced mitochondrial mass and mtDNA content No mtDNA alterations Decrease of mitochondrial trafficking leading to perinuclear aggregation No survival and morphometric defects Increased resistance to apoptosis Increased autophagic and mitophagic flux |

Rizzo F. et al., 2016 |

| Motor neurons derived from iPSCs of patients with CMT2A | R94Q | Abnormal mitochondrial morphology: shorter mitochondrial length within neurites, presence of abnormal mitochondria with loss of crista Reduction in the percentage of moving mitochondria Decrease in ATP levels in neurites Increased toxicity sensitivity to vincristine and paclitaxel |

Ohara et al., 2017 |

| Motor neurons derived from iPSCs of patients with CMT2A | R94Q | Hyper-connectivity: increase in burst rate Alterations in mitochondrial morphology: reduced mitochondrial elongation and increase in circularity Impairment in axonal transport: decrease in the speed of mitochondria and lysosomes and the proportion of active mitochondria and lysosomes moving within the cells Defects in OxPhos: decrease in mitochondrial basal respiration. Transcriptomic analysis: enrichment in “PI3K-AKT signalling” and respiratory chain pathway |

Van Lent et 2021 |

| Skin fibroblasts derived from CMT2A patients | R364W M376V W740S |

Mitochondrial mass and mtDNA levels are unchanged Moderate disturbances in Ca2+ homeostasis Reduced ER-mitochondria contacts |

Larrea D. et al., 2019 |

| Skin fibroblasts from CMT2A patient | C217F | Mitochondrial mass and mtDNA levels and integrity unchanged Mitochondrial fragmentation Reduced ΔѰm Reduction of respiratory chain complexes activity Transcriptomic analysis: enrichment in “PI3K-AKT signalling” Reduced autophagy and increased cellular proliferation (mTORC2/AKT activation) |

Zanfardino P. et al., 2022 |

| Cell Type | OPA1 mutation | Remarks | References |

| Fibroblasts from 3 patients with ADOA plus | V903Gfs3, E221K QT86Sfs15, H957Y QT86Sfs*15, H957Y |

Increased mitochondrial fragmentation Depletion of mtDNA Altered mitochondrial localization Increased mitophagy flux |

Liao C. et al., 2017 |

| Fibroblasts from 7 ADOA patients |

|

1) and 2) Fragmented and punctiform mitochondria 3) Mild mitochondrial fragmentation 1), 2), and 3) Loss of mitochondrial volume 1) and 2) Mild uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation 4) and 6) Severe defects in oxidative phosphorylation Altered autophagy 4) and 5) Mild mtDNA depletion |

Kane M. S. et al., 2017 |

| Lymphoblastoid cells derived from ADOA patients | P400A | Decreased mtDNA copy number Reduced levels of 4 mtDNA-encoded polypeptides Respiratory capacity defects ATP synthesis defects Altered mitochondrial membrane potential Increased ROS production Increased apoptosis Mitochondrial morphological defects (fragmentation and swelling) |

Zhang et al., 2017 |

| Lymphoblastoid cell lines from ADOA patient | c.1444–2A>C (splicing variants, deletion of the 15th exon in mRNA transcript, low protein levels) | Respiratory chain activity defects More punctate mitochondria clustered in the perinuclear region, No marked depletion of mtDNA or mitochondrial mass Reduced ATP synthesis Reduced ΔѰm Increased ROS production Increased mitophagy |

Sun C. et al., 2021 |

| Skin fibroblasts from ADOA plus patient | H42Y | Mitochondrial mass unchanged mtDNA levels slighly increased mtDNA integrity unchanged Mitochondrial fragmentation Reduced ΔѰm Reduction of respiratory chain complexes activity Increased ROS production Transcriptomic analysis: enrichment in “p21WAF1/CIP1 and p53 pathways” along with downregulation of mitotic cell cycle genes Reduced autophagy and increased expression of senescence markers (SA-β galactosidase; p53 and p21) associated with lower mTORC2 activity |

Zanfardino P. et al., 2024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).