Submitted:

10 July 2024

Posted:

11 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

Cell Lines and Cell Culture Conditions

Cell Cycle Synchronization

Double Thymidine

Nocodazole

Cytotoxicity Assay

Clonogenic Cell Survival Assay

Flow Cytometry

siRNA Transfection

Plasmid Construction and Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Immunofluorescence Staining and Confocal Microscopy

Co-Immunoprecipitation

Western Blot Analysis

Mitochondria Subcellular Fractionation

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

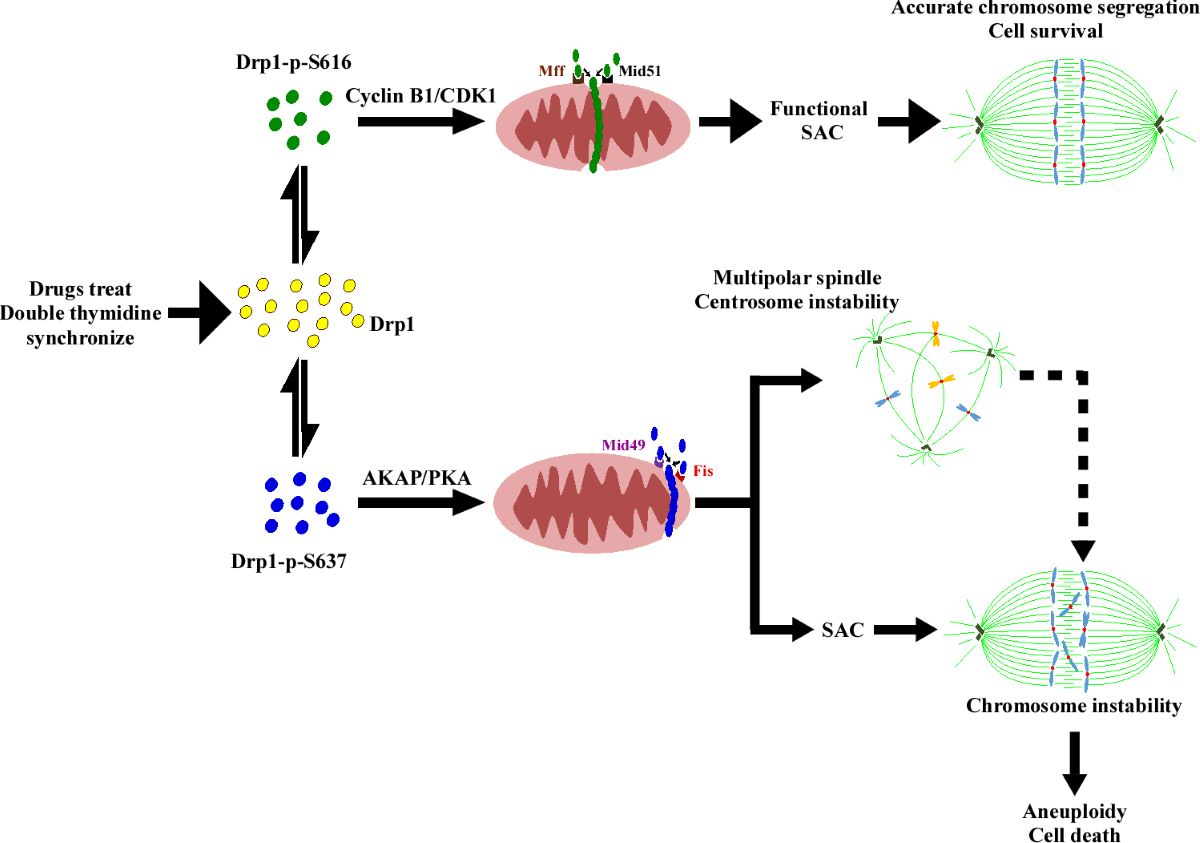

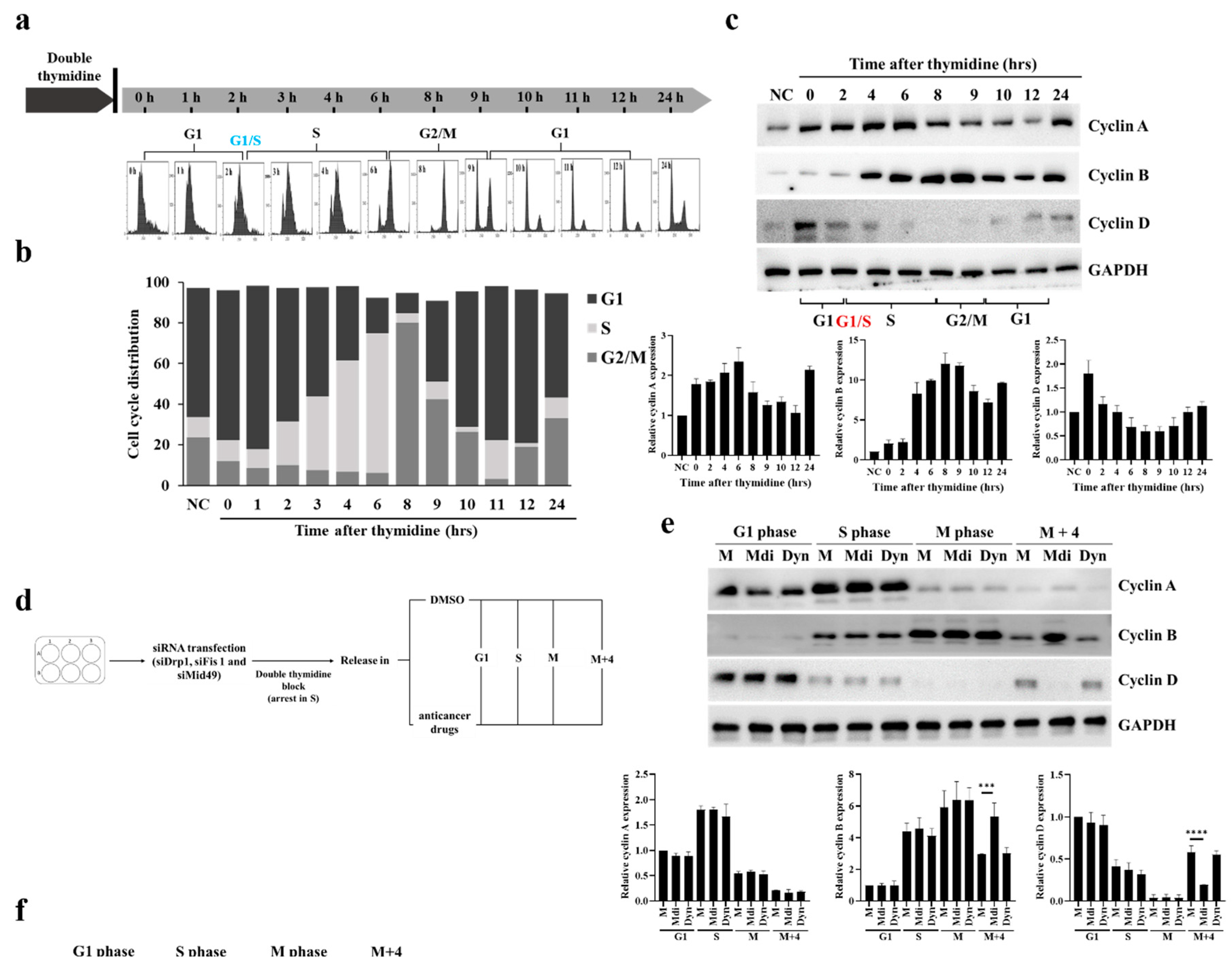

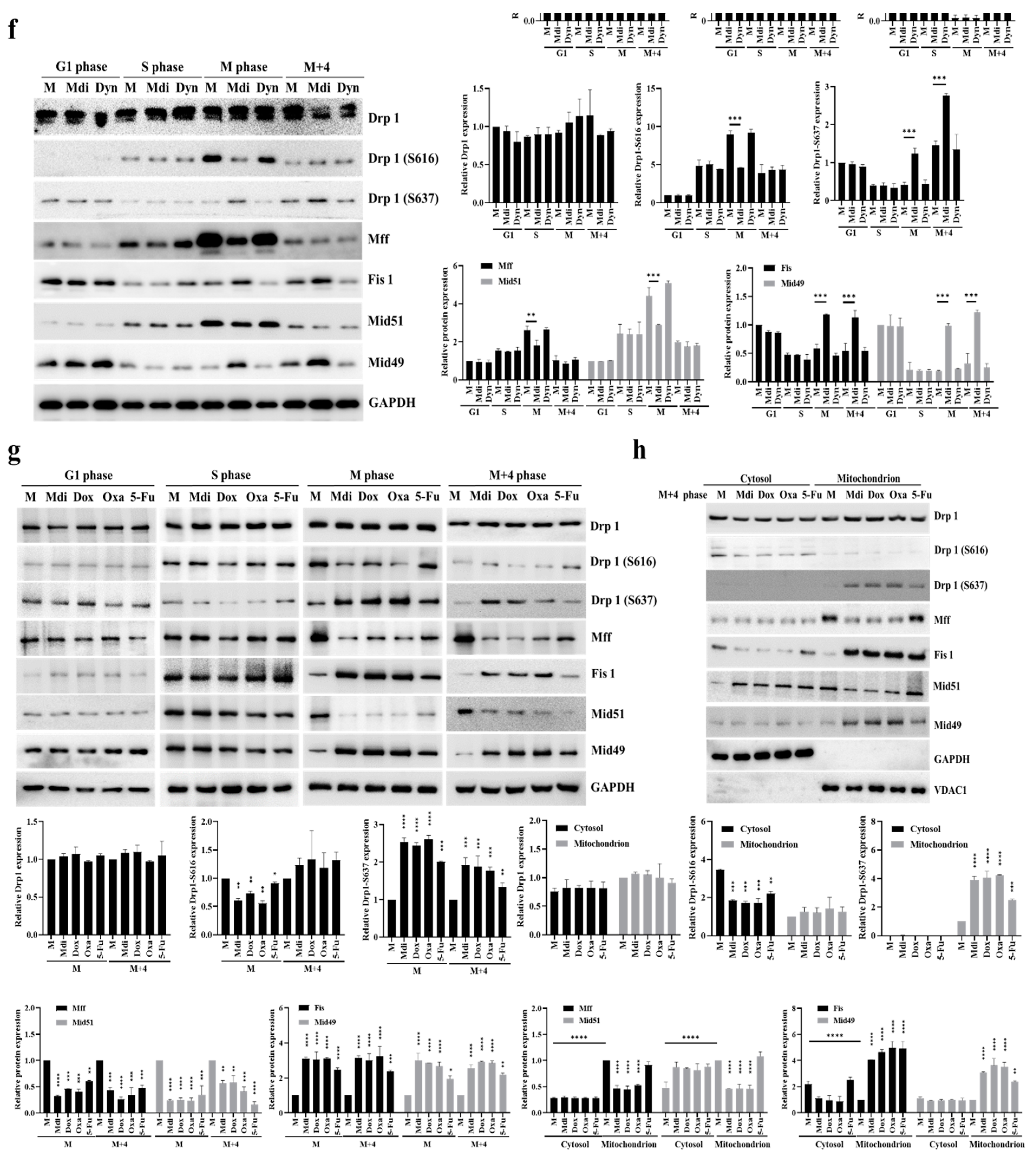

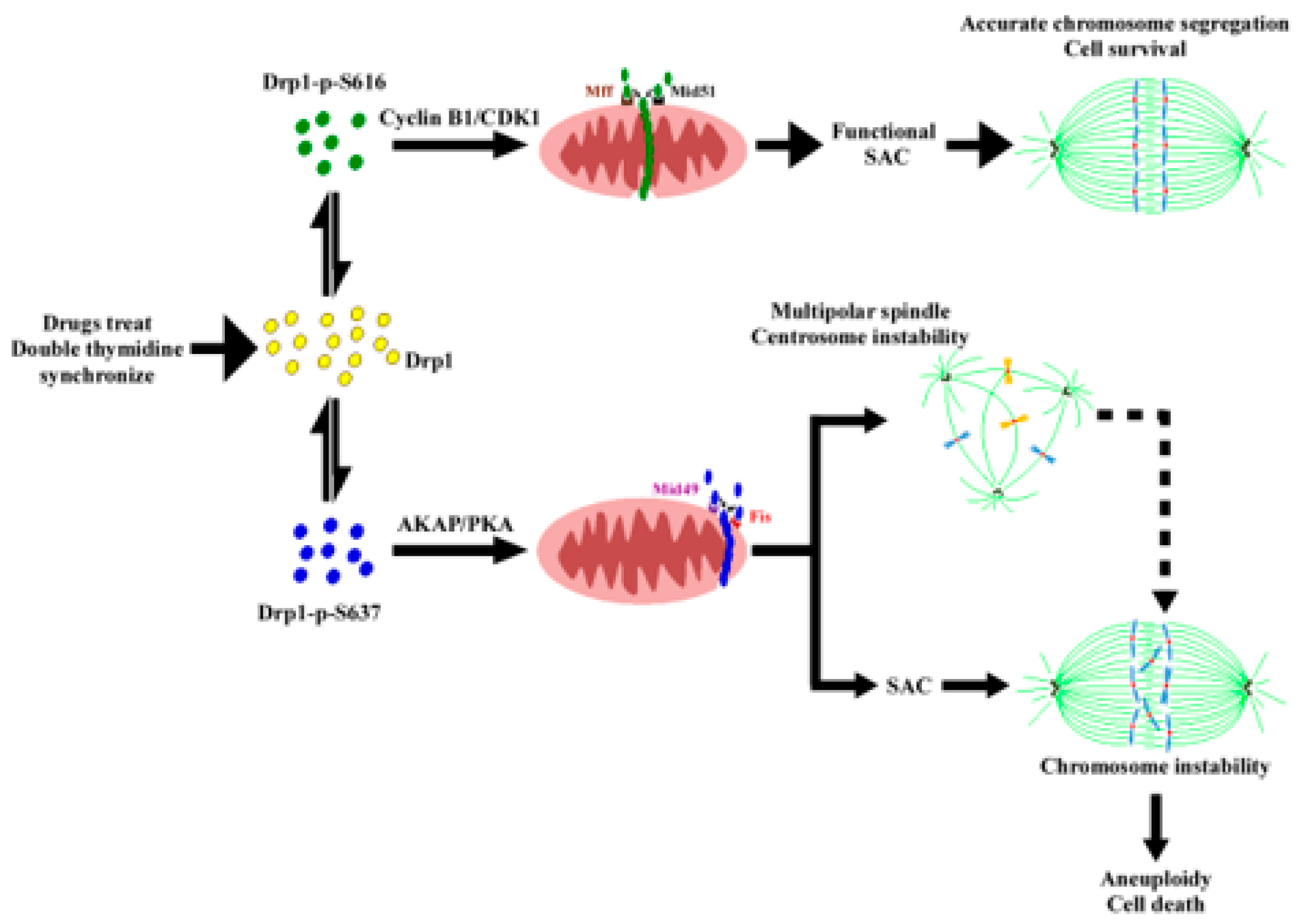

3.1. Two Signaling Clusters of Mitochondrial Fission on Double-Thymidine Synchronized HeLa Cell Cycle Progression- Phsopho-Drp1 Status with Four Drp1 Adaptors

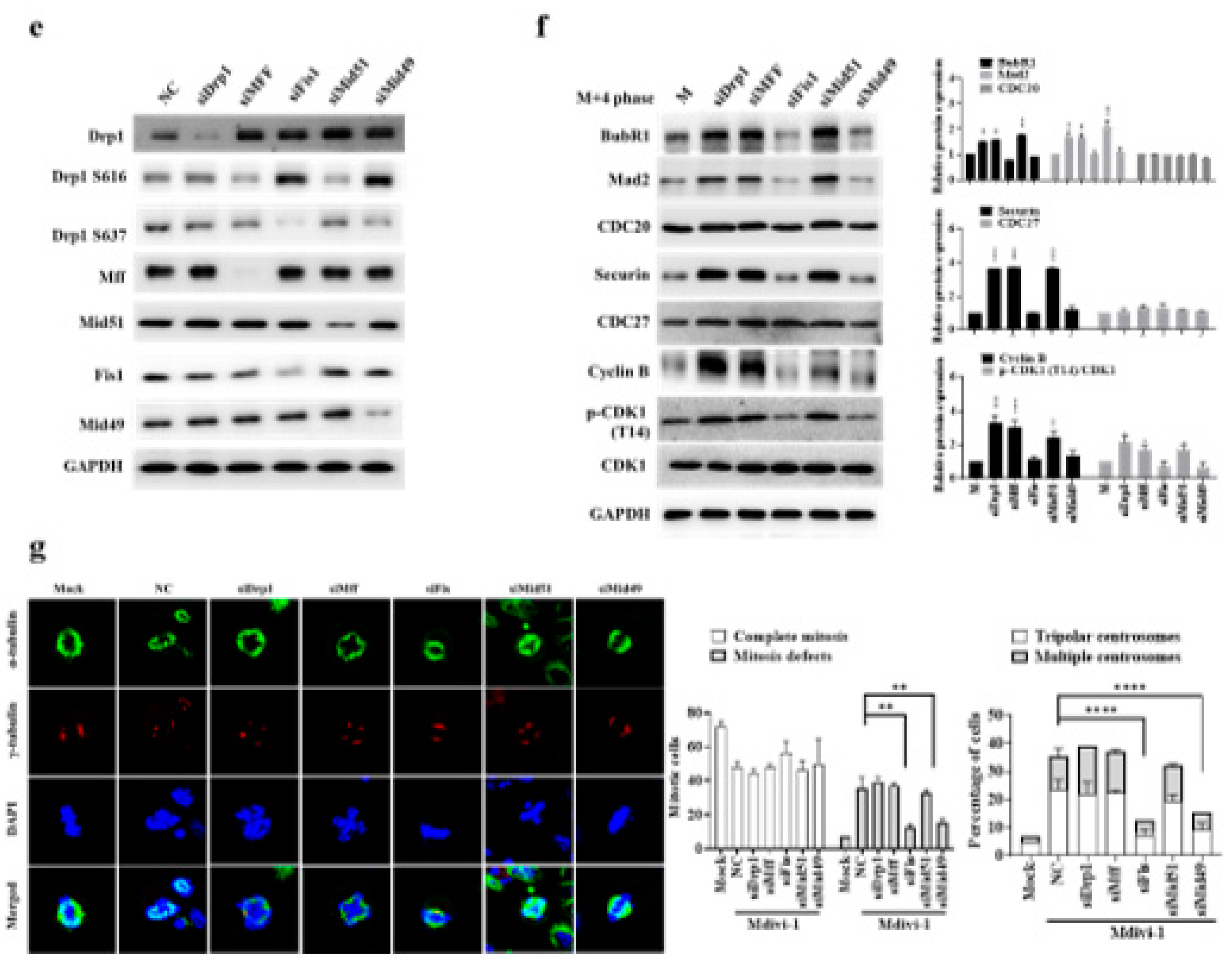

3.2. The Two Signaling Clusters of Mitochondrial Fission Correspond to and Link Two Distinct Types of Mitochondrial Fission during Mitosis

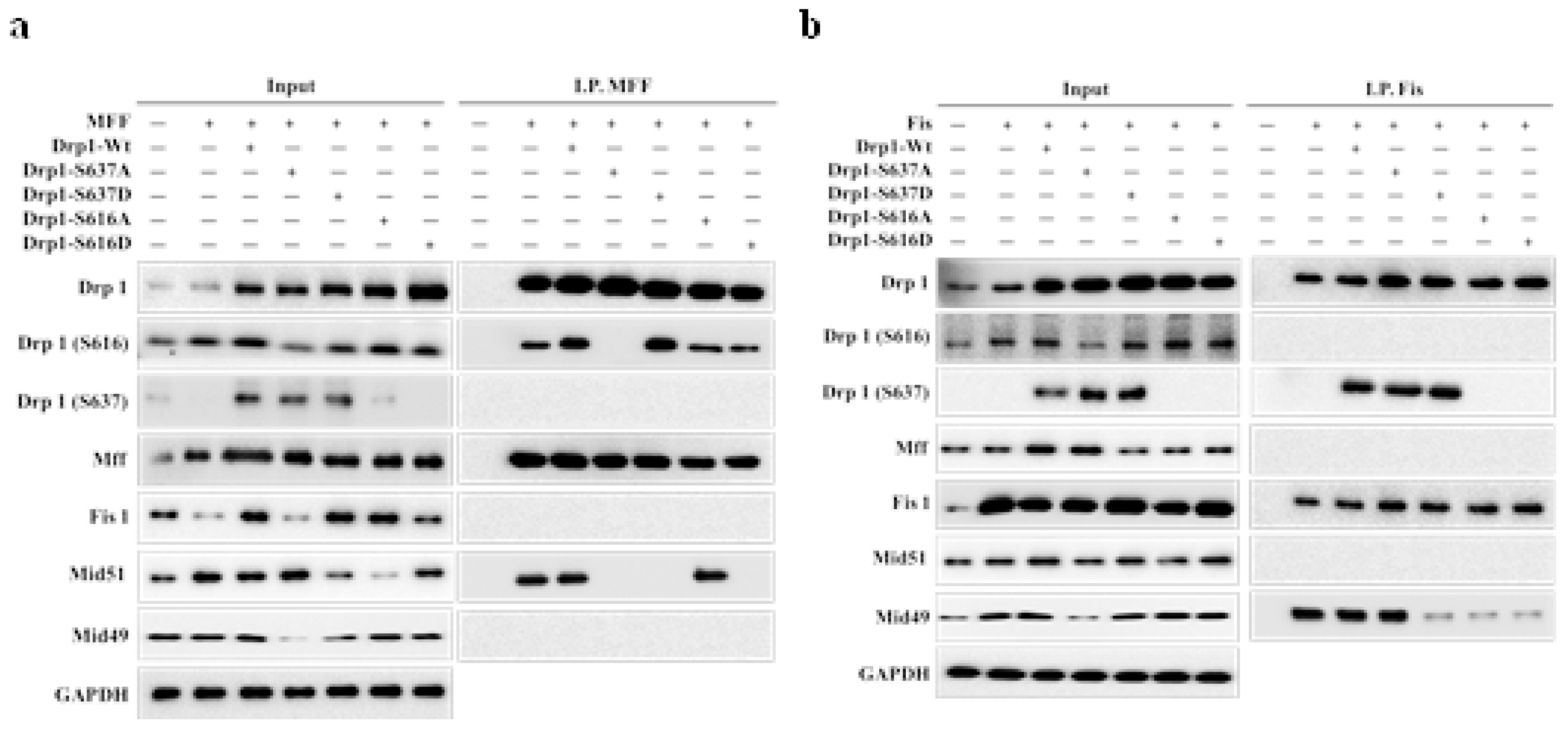

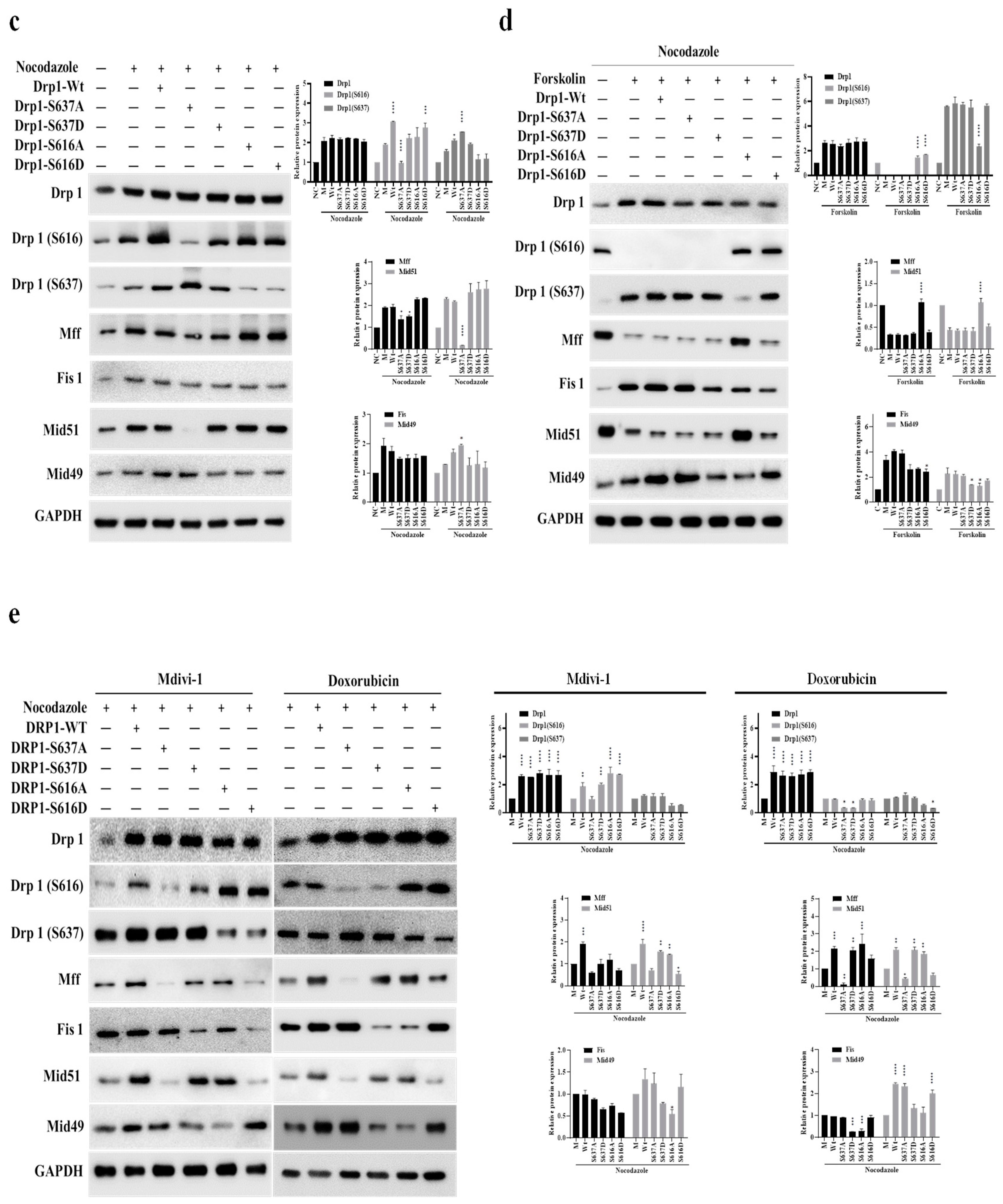

3.3. The Delicate Interplay of Two Phospho-Drp1 (Ser-616 and Ser-637) Clusters

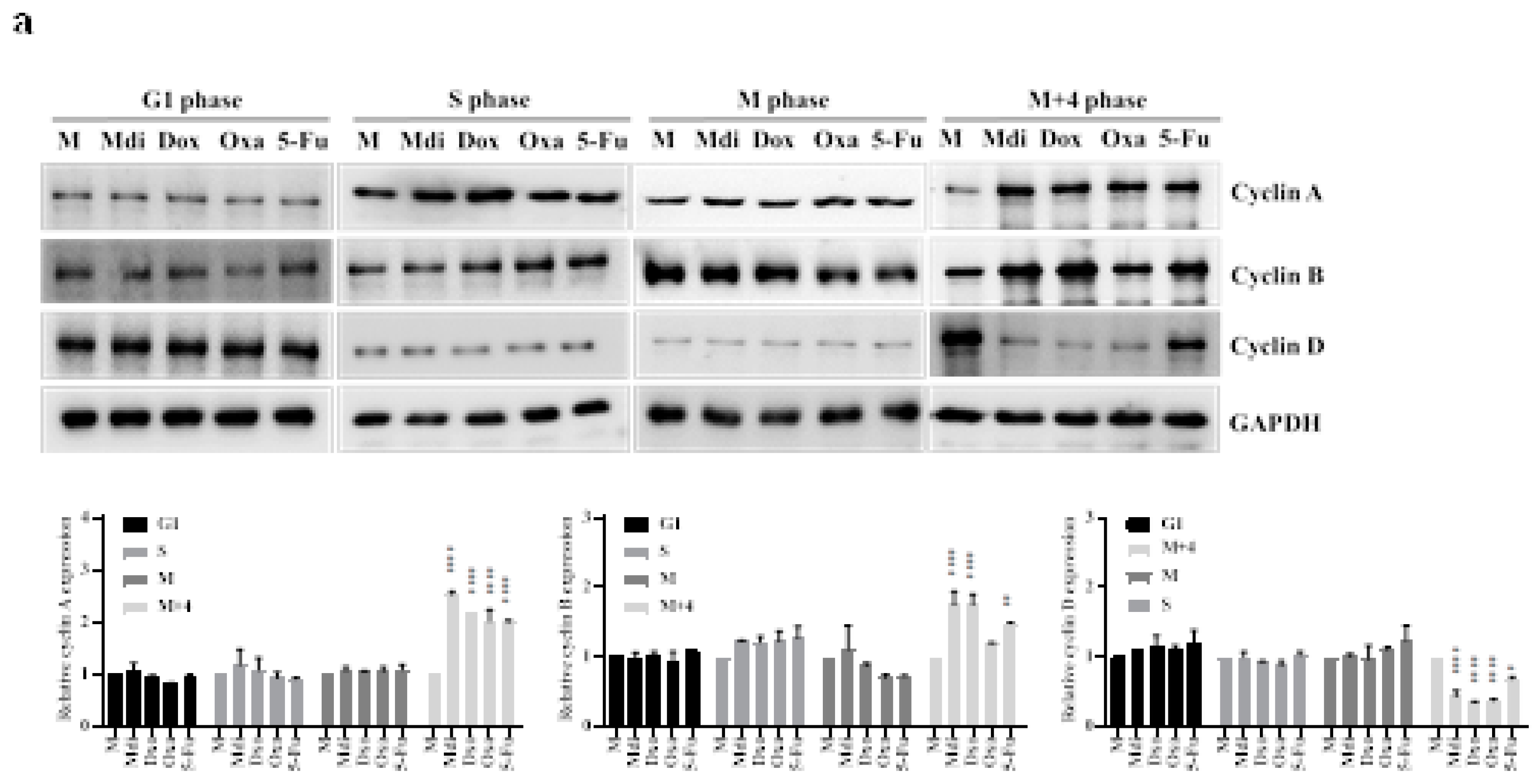

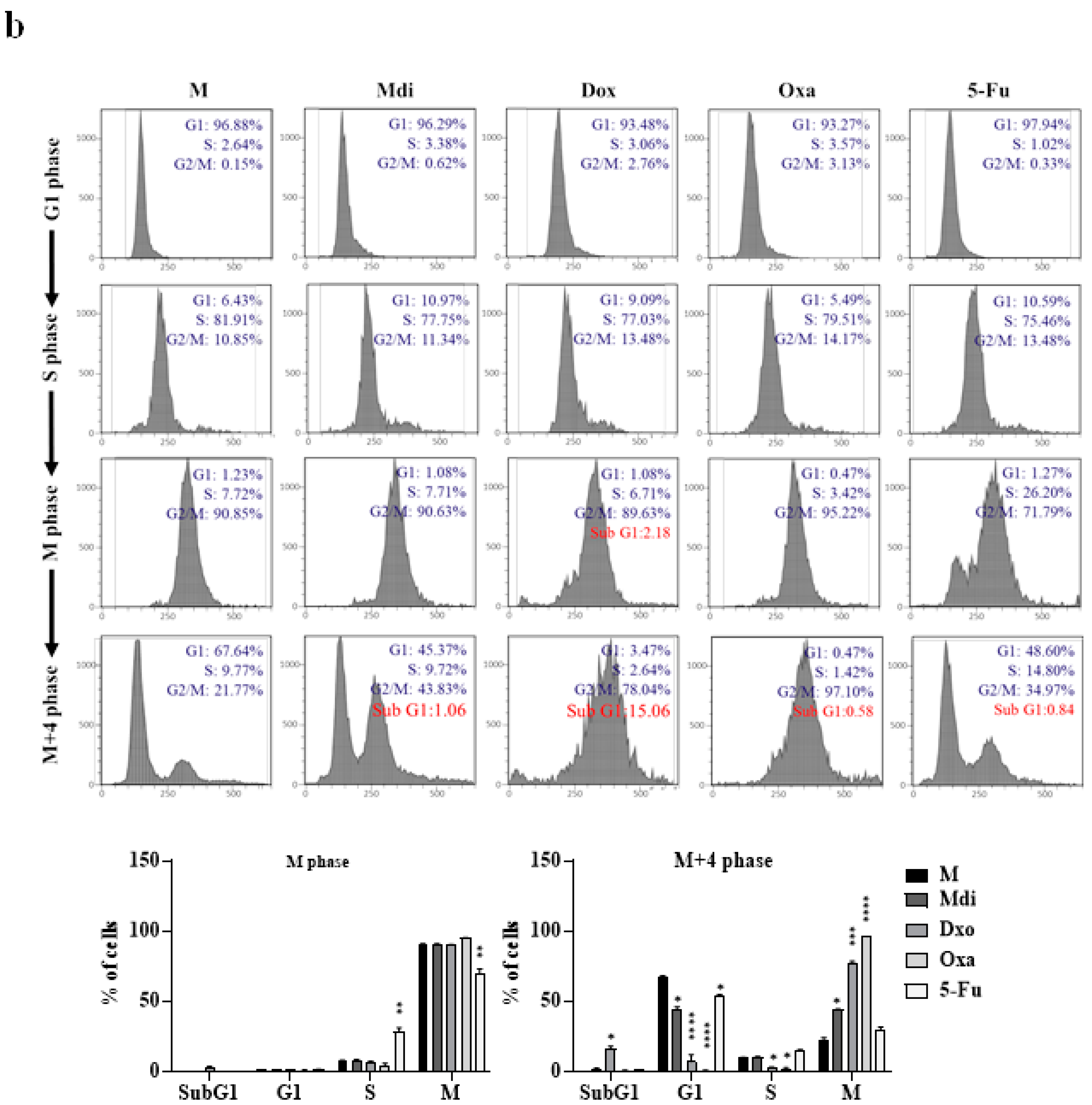

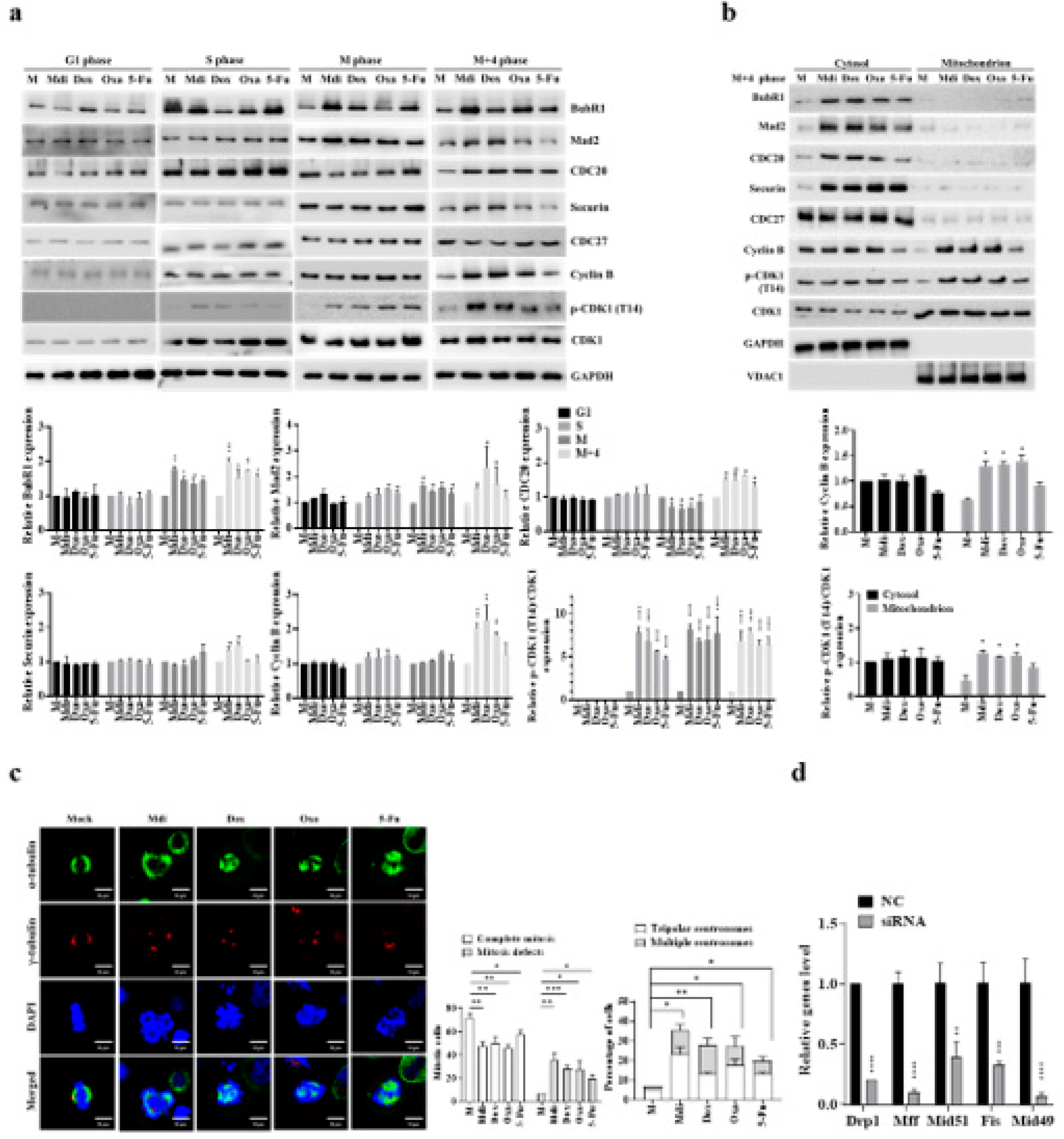

3.4. The Impact of DRUGS on the Hela cell Cycle and Survival

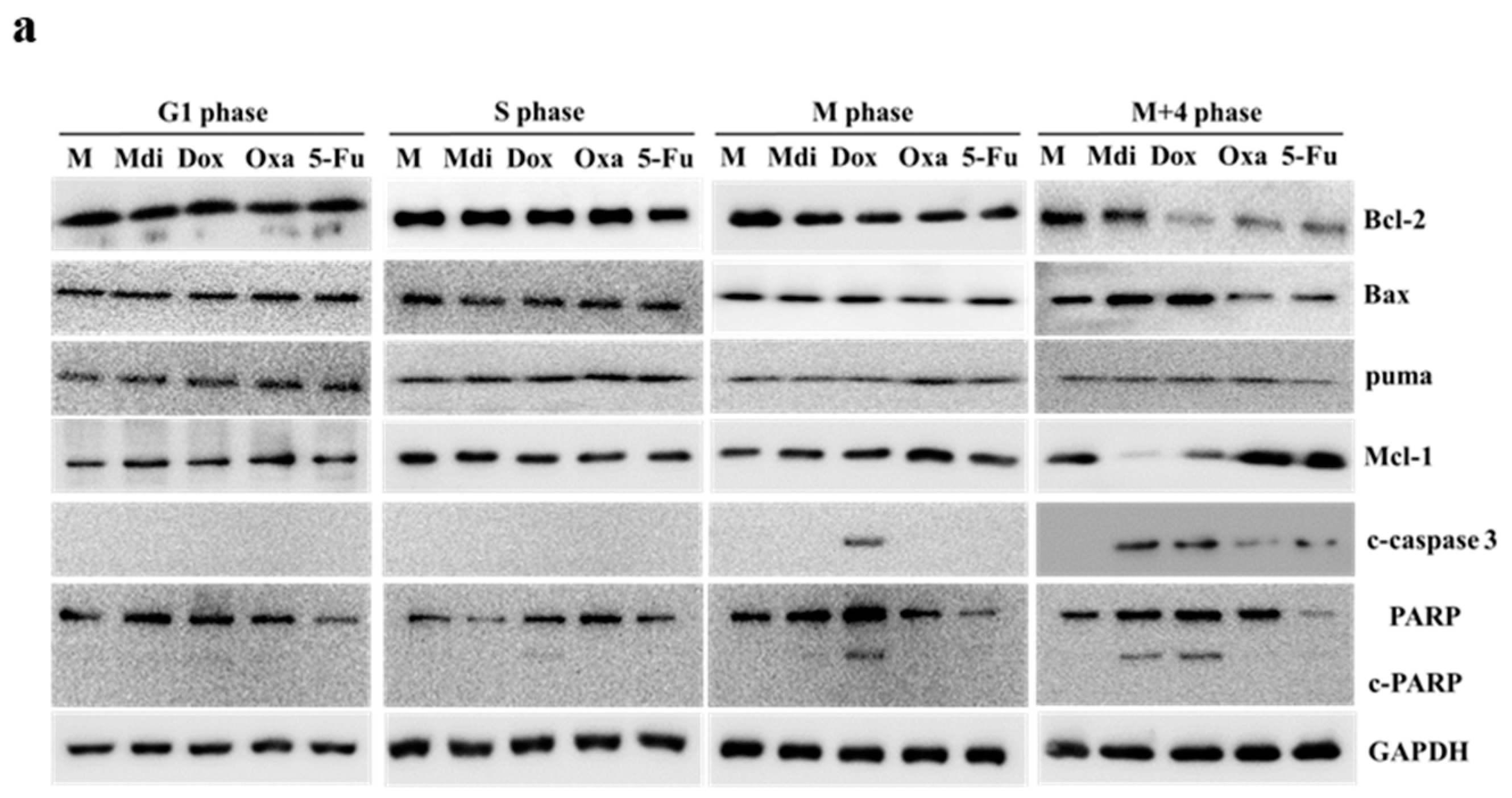

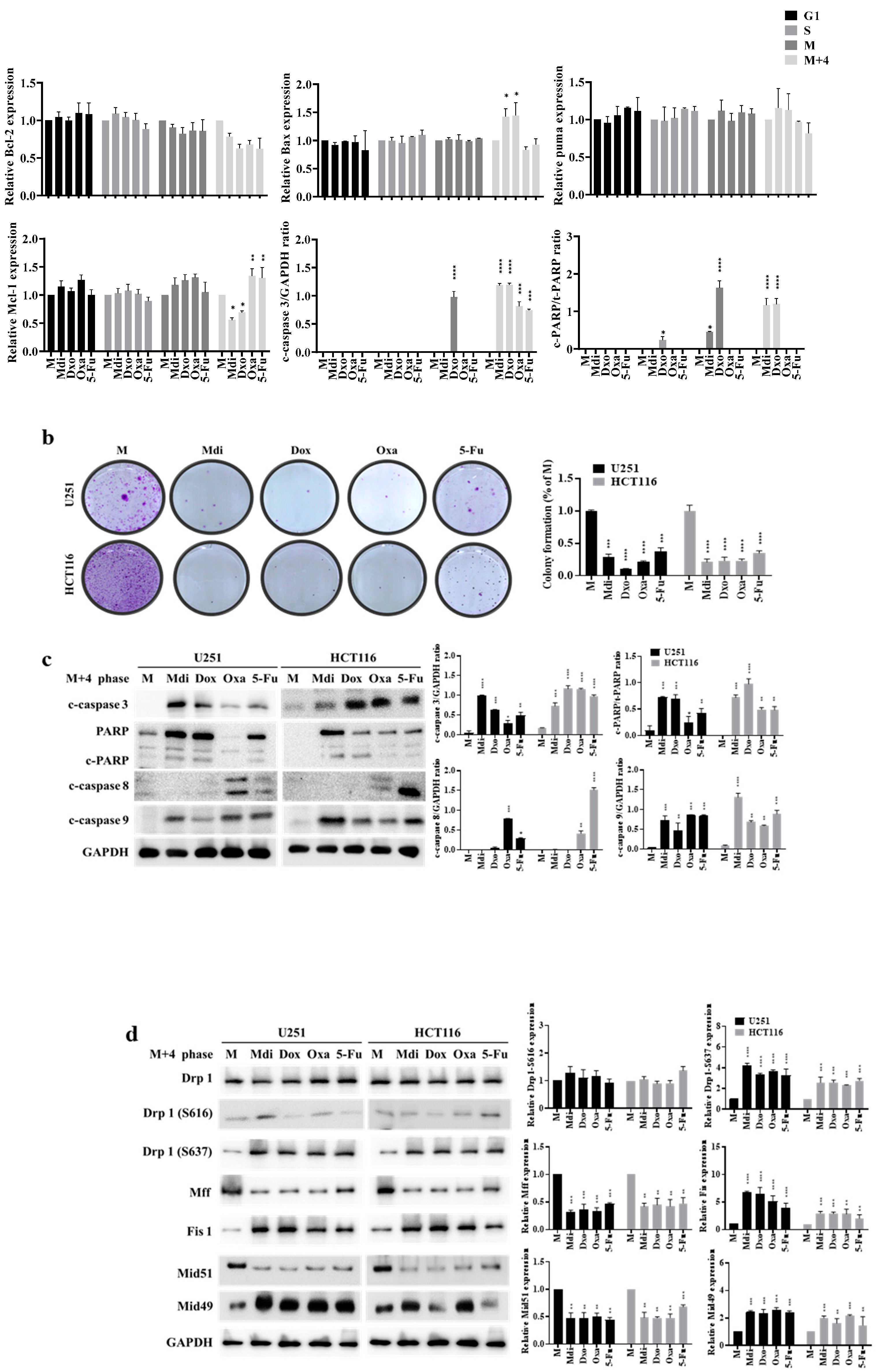

3.5. Enhancing Sensitivity to Mitotic Arrest and Inducing Apoptosis in Various Synchronized Cells

3.6. Regulation of SAC Function and Mitotic Spindle Formation by a Variety of Anti-Cancer Drugs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sinha, D.; Duijf, P.H.G.; Khanna, K.K. Mitotic slippage: an old tale with a new twist. Cell Cycle 2019, 18, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryniawec, J.M.; Rogers, G.C. Centrosome instability: when good centrosomes go bad. Cell Mol Life Sci 2021, 78, 6775–6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, B.A.; Silk, A.D.; Montagna, C.; Verdier-Pinard, P.; Cleveland, D.W. Aneuploidy acts both oncogenically and as a tumor suppressor. Cancer Cell 2007, 11, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigg, E.A. Centrosome aberrations: cause or consequence of cancer progression? Nature Reviews Cancer 2002, 2, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, D.J.; Resio, B.; Pellman, D. Causes and consequences of aneuploidy in cancer. Nat Rev Genet 2012, 13, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleele, T.; Rey, T.; Winter, J.; Zaganelli, S.; Mahecic, D.; Perreten Lambert, H.; Ruberto, F.P.; Nemir, M.; Wai, T.; Pedrazzini, T., et al. Distinct fission signatures predict mitochondrial degradation or biogenesis. Nature 2021, 593, 435–439. [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, R.; Higgs, H. Revolutionary view of two ways to split a mitochondrion. Nature 2021, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, H.J.; Tsai, C.Y.; Chiou, S.J.; Lai, Y.L.; Wang, C.H.; Cheng, J.T.; Chuang, T.H.; Huang, C.F.; Kwan, A.L.; Loh, J.K., et al. The Phosphorylation Status of Drp1-Ser637 by PKA in Mitochondrial Fission Modulates Mitophagy via PINK1/Parkin to Exert Multipolar Spindles Assembly during Mitosis. Biomolecules 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Pangou, E.; Sumara, I. The Multifaceted Regulation of Mitochondrial Dynamics During Mitosis. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 767221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.; Lim, H.H.; Surana, U. Mapping Mitotic Death: Functional Integration of Mitochondria, Spindle Assembly Checkpoint and Apoptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol 2018, 6, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.S.; Ma, I.C.; Lin, Y.F.; Ko, H.J.; Loh, J.K.; Hong, Y.R. The mystery of phospho-Drp1 with four adaptors in cell cycle: when mitochondrial fission couples to cell fate decisions. Cell Cycle, 2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santel, A.; Frank, S. Shaping mitochondria: The complex posttranslational regulation of the mitochondrial fission protein DRP1. IUBMB Life 2008, 60, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.R.; Blackstone, C. Dynamic regulation of mitochondrial fission through modification of the dynamin-related protein Drp1. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010, 1201, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.R.; Blackstone, C. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylation of Drp1 regulates its GTPase activity and mitochondrial morphology. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 21583–21587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cribbs, J.T.; Strack, S. Reversible phosphorylation of Drp1 by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase and calcineurin regulates mitochondrial fission and cell death. EMBO Rep 2007, 8, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cereghetti, G.M.; Stangherlin, A.; Martins de Brito, O.; Chang, C.R.; Blackstone, C.; Bernardi, P.; Scorrano, L. Dephosphorylation by calcineurin regulates translocation of Drp1 to mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 15803–15808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taguchi, N.; Ishihara, N.; Jofuku, A.; Oka, T.; Mihara, K. Mitotic phosphorylation of dynamin-related GTPase Drp1 participates in mitochondrial fission. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 11521–11529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, C.H.; Lin, C.C.; Yang, M.C.; Wei, C.C.; Liao, H.D.; Lin, R.C.; Tu, W.Y.; Kao, T.C.; Hsu, C.M.; Cheng, J.T. , et al. GSK3beta-mediated Drp1 phosphorylation induced elongated mitochondrial morphology against oxidative stress. PLoS One 2012, 7, e49112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youle, R.J.; van der Bliek, A.M. Mitochondrial fission, fusion, and stress. Science 2012, 337, 1062–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.S.; Osellame, L.D.; Laine, D.; Koutsopoulos, O.S.; Frazier, A.E.; Ryan, M.T. MiD49 and MiD51, new components of the mitochondrial fission machinery. EMBO Rep 2011, 12, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgass, K.; Pakay, J.; Ryan, M.T.; Palmer, C.S. Recent advances into the understanding of mitochondrial fission. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1833, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovski, D.; Koutsopoulos, O.S.; Okamoto, K.; Ryan, M.T. Levels of human Fis1 at the mitochondrial outer membrane regulate mitochondrial morphology. Journal of Cell Science 2004, 117, 1201–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, M.; Jeong, S.-Y.; Karbowski, M.; Youle, R.J.; Tjandra, N. The Solution Structure of Human Mitochondria Fission Protein Fis1 Reveals a Novel TPR-like Helix Bundle. Journal of Molecular Biology 2003, 334, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandre-Babbe, S.; van der Bliek, A.M. The Novel Tail-anchored Membrane Protein Mff Controls Mitochondrial and Peroxisomal Fission in Mammalian Cells. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2008, 19, 2402–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogensen, M.M. Microtubule release and capture in epithelial cells. Biol Cell 1999, 91, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abal, M.; Piel, M.; Bouckson-Castaing, V.; Mogensen, M.; Sibarita, J.B.; Bornens, M. Microtubule release from the centrosome in migrating cells. J Cell Biol 2002, 159, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugnard, E.; Zaal, K.J.; Ralston, E. Reorganization of microtubule nucleation during muscle differentiation. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton 2005, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boveri, T. Concerning the origin of malignant tumours by Theodor Boveri. Translated and annotated by Henry Harris. J Cell Sci 2008, 121 Suppl 1, 1–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornens, M. Centrosome composition and microtubule anchoring mechanisms. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2002, 14, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bettencourt-Dias, M.; Glover, D.M. Centrosome biogenesis and function: centrosomics brings new understanding. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007, 8, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, H.A.; Nigg, E.A. Antibody microinjection reveals an essential role for human polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) in the functional maturation of mitotic centrosomes. J Cell Biol 1996, 135, 1701–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, A.M.; Meraldi, P.; Nigg, E.A. A centrosomal function for the human Nek2 protein kinase, a member of the NIMA family of cell cycle regulators. Embo j 1998, 17, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casenghi, M.; Meraldi, P.; Weinhart, U.; Duncan, P.I.; Körner, R.; Nigg, E.A. Polo-like kinase 1 regulates Nlp, a centrosome protein involved in microtubule nucleation. Dev Cell 2003, 5, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casenghi, M.; Barr, F.A.; Nigg, E.A. Phosphorylation of Nlp by Plk1 negatively regulates its dynein-dynactin-dependent targeting to the centrosome. J Cell Sci 2005, 118, 5101–5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meraldi, P.; Honda, R.; Nigg, E.A. Aurora kinases link chromosome segregation and cell division to cancer susceptibility. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2004, 14, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayor, T.; Meraldi, P.; Stierhof, Y.D.; Nigg, E.A.; Fry, A.M. Protein kinases in control of the centrosome cycle. FEBS Lett 1999, 452, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donthamsetty, S.; Brahmbhatt, M.; Pannu, V.; Rida, P.C.; Ramarathinam, S.; Ogden, A.; Cheng, A.; Singh, K.K.; Aneja, R. Mitochondrial genome regulates mitotic fidelity by maintaining centrosomal homeostasis. Cell Cycle 2014, 13, 2056–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, P.; Panda, D. Rotenone inhibits mammalian cell proliferation by inhibiting microtubule assembly through tubulin binding. Febs j 2007, 274, 4788–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A.; Golden, A. Hypothesis: Bifunctional mitochondrial proteins have centrosomal functions. Environ Mol Mutagen 2009, 50, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashatus, D.F.; Lim, K.H.; Brady, D.C.; Pershing, N.L.; Cox, A.D.; Counter, C.M. RALA and RALBP1 regulate mitochondrial fission at mitosis. Nat Cell Biol 2011, 13, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, K.S.; Huh, S.; Liu, S.; Lee, D.Y.; Hong, S.H.; Yu, K.; Lu, B. Polo Kinase Phosphorylates Miro to Control ER-Mitochondria Contact Sites and Mitochondrial Ca(2+) Homeostasis in Neural Stem Cell Development. Dev Cell 2016, 37, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, N.; Sicheritz-Pontén, T.; Gupta, R.; Gammeltoft, S.; Brunak, S. Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics 2004, 4, 1633–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, C.S.; Elgass, K.D.; Parton, R.G.; Osellame, L.D.; Stojanovski, D.; Ryan, M.T. Adaptor proteins MiD49 and MiD51 can act independently of Mff and Fis1 in Drp1 recruitment and are specific for mitochondrial fission. J Biol Chem 2013, 288, 27584–27593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Wu, S.; Xing, D. Drp1, Mff, Fis1, and MiD51 are coordinated to mediate mitochondrial fission during UV irradiation-induced apoptosis. Faseb j 2016, 30, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.Y.; Ma, W.L.; Liang, S.; Zeng, Y.; Shi, R.; Yu, H.L.; Xiao, W.W.; Zheng, W.L. Analysis of microRNA expression profiles during the cell cycle in synchronized HeLa cells. BMB Rep 2009, 42, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losón, O.C.; Song, Z.; Chen, H.; Chan, D.C. Fis1, Mff, MiD49, and MiD51 mediate Drp1 recruitment in mitochondrial fission. Mol Biol Cell 2013, 24, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, R.; Liu, T.; Ning, C.; Tan, F.; Jin, S.B.; Lendahl, U.; Zhao, J.; Nistér, M. The phosphorylation status of Ser-637 in dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) does not determine Drp1 recruitment to mitochondria. J Biol Chem 2019, 294, 17262–17277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangou, E.; Bielska, O.; Guerber, L.; Schmucker, S.; Agote-Arán, A.; Ye, T.; Liao, Y.; Puig-Gamez, M.; Grandgirard, E.; Kleiss, C. , et al. A PKD-MFF signaling axis couples mitochondrial fission to mitotic progression. Cell Reports 2021, 35, 109129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westrate, L.M.; Sayfie, A.D.; Burgenske, D.M.; MacKeigan, J.P. Persistent Mitochondrial Hyperfusion Promotes G2/M Accumulation and Caspase-Dependent Cell Death. PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e91911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castedo, M.; Perfettini, J.L.; Roumier, T.; Andreau, K.; Medema, R.; Kroemer, G. Cell death by mitotic catastrophe: a molecular definition. Oncogene 2004, 23, 2825–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, M.; Ando, H.; Watanabe, N.; Kitamura, K.; Ito, K.; Okayama, H.; Miyamoto, T.; Agui, T.; Sasaki, M. Identification and characterization of human Wee1B, a new member of the Wee1 family of Cdk-inhibitory kinases. Genes to Cells 2000, 5, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. Cdc20: a WD40 activator for a cell cycle degradation machine. Mol Cell 2007, 27, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Farrell, P.H. Triggering the all-or-nothing switch into mitosis. Trends in Cell Biology 2001, 11, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulonval, K.; Kooken, H.; Roger, P.P. Coupling of T161 and T14 phosphorylations protects cyclin B-CDK1 from premature activation. Mol Biol Cell 2011, 22, 3971–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña-Blanco, A.; Haschka, M.D.; Jenner, A.; Zuleger, T.; Proikas-Cezanne, T.; Villunger, A.; García-Sáez, A.J. Drp1 modulates mitochondrial stress responses to mitotic arrest. Cell Death Differ 2020, 27, 2620–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, D.; Reddy, P.H. Dynamics of Dynamin-Related Protein 1 in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, J.S.; Kaur, S.; Mishra, J.; Dibbanti, H.; Singh, A.; Reddy, A.P.; Bhatti, G.K.; Reddy, P.H. Targeting dynamin-related protein-1 as a potential therapeutic approach for mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2023, 1869, 166798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Clusters | Function | Mitochondria Fission | SAC Function | Mitotic cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drp1-S616/Mff/Mid51 | Up | Midzone | Normal | Bipolar spindles |

| Drp1-S616/Mff/Mid51 | Down | Peripheral | Up | Multipolar spindles |

| Drp1-S637/Fis/Mid49 | Up | Peripheral | Up | Multipolar spindles |

| Drp1-S637/Fis/Mid49 | Down | Midzone | Normal | Bipolar spindles |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).