1. Background

Mitochondria respond to stress by activating quality control pathways, including mitochondrial-derived vesicle (MDV) formation, which selectively removes damaged components to maintain cellular homeostasis [

1]. MDVs are known to deliver cargo to lysosomes for degradation, a process regulated by proteins such as Parkin and PINK1 [

2]. However, emerging evidence suggests MDVs may also communicate with non-degradative organelles, though their cargo specificity and mechanisms of interorganellar trafficking remain unresolved [

3]. Current studies focus predominantly on MDV-lysosome interactions, neglecting potential roles in peroxisomal redox regulation or mtDNA protection [

1,

3]. Notably, peroxisomes and lysosomes collaborate in reactive oxygen species (ROS) detoxification, yet how mitochondria coordinate with these organelles under stress is unknown. We hypothesize that MDVs mediate interorganellar antioxidant transfer under oxidative stress through Rab32, a GTPase implicated in mitochondrial membrane dynamics [

4]. This study investigates MDV cargo selectivity, Rab32-dependent trafficking, and functional consequences for mitochondrial integrity, addressing critical gaps in understanding organelle crosstalk in redox adaptation.

2. Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Treatments

HeLa cells (ATCC

® CCL-2™) and primary murine fibroblasts (isolated from C57BL/6 mice) were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C under 5% CO₂. Rab32-knockout (Rab32-KO) fibroblasts were generated using CRISPR-Cas9 (see Section 4). For oxidative stress induction, cells were treated with 500 µM H₂O₂ (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 hours [

5]. Mitophagy was inhibited using 10 µM carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP; Sigma-Aldrich) for 6 hours prior to H₂O₂ exposure [

6].

2.2. MDV Isolation and Characterization

Mitochondrial-derived vesicles (MDVs) were isolated via differential centrifugation as described previously [

5], with modifications. Briefly, cells were homogenized in isolation buffer (225 mM mannitol, 75 mM sucrose, 0.1% BSA, pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 1,000 ×

g to remove nuclei. The supernatant was subjected to 10,000 ×

g centrifugation to pellet mitochondria, followed by 100,000 ×

gultracentrifugation (Optima XE-100, Beckman Coulter) to collect MDVs. Vesicle size and purity were confirmed by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NanoSight NS300) and immunoblotting for mitochondrial (TOM20) and lysosomal (LAMP1) markers.

2.3. Super-Resolution Microscopy (STED)

MDV dynamics were tracked using stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy (Leica TCS SP8). Cells were transfected with MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Thermo Fisher) for mitochondrial labeling and immunostained with anti-Rab32 (Abcam, ab154815) and anti-PEX14 (Proteintech, 10594-1-AP) antibodies. Images were acquired at 100× magnification and processed with LAS X software (Leica). Colocalization analysis was performed using ImageJ (Fiji) with the JACoB plugin [

7].

2.4. SILAC-Based Proteomics

Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino Acids in Cell Culture (SILAC) was performed as described [

6]. Cells were cultured in DMEM containing heavy lysine (¹³C₆, ¹⁵N₂; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories) for 6 days. MDV proteins were extracted using RIPA buffer, digested with trypsin, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS (Q Exactive HF-X, Thermo Fisher). Data were processed using MaxQuant (v1.6.17.0) against the UniProt human database. Proteins with a fold-change >2 and

p < 0.05 (Student’s

t-test) were considered significant.

2.5. CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout of Rab32

Rab32 was knocked out using a single-guide RNA (sgRNA: 5′-GACCGGCGCTACTTCGACGT-3′) cloned into the lentiCRISPRv2 vector (Addgene #52961). Lentiviral particles were produced in HEK293T cells and used to transduce primary fibroblasts. Knockout efficiency was validated by Western blot (anti-Rab32, Abcam ab154815) and Sanger sequencing [

8].

2.6. Mitochondrial Respiration Analysis

Oxygen consumption rates (OCR) were measured using the Seahorse XFe96 Analyzer (Agilent Technologies). Cells (2 × 10⁴/well) were seeded in XF DMEM medium (pH 7.4) and sequentially treated with oligomycin (1 µM), FCCP (2 µM), and rotenone/antimycin A (0.5 µM). Data were normalized to protein content and analyzed using Wave Software (v2.6) [

9].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using GraphPad Prism (v9.0) with one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05) or Student’s t-test (p < 0.05).

3. Results

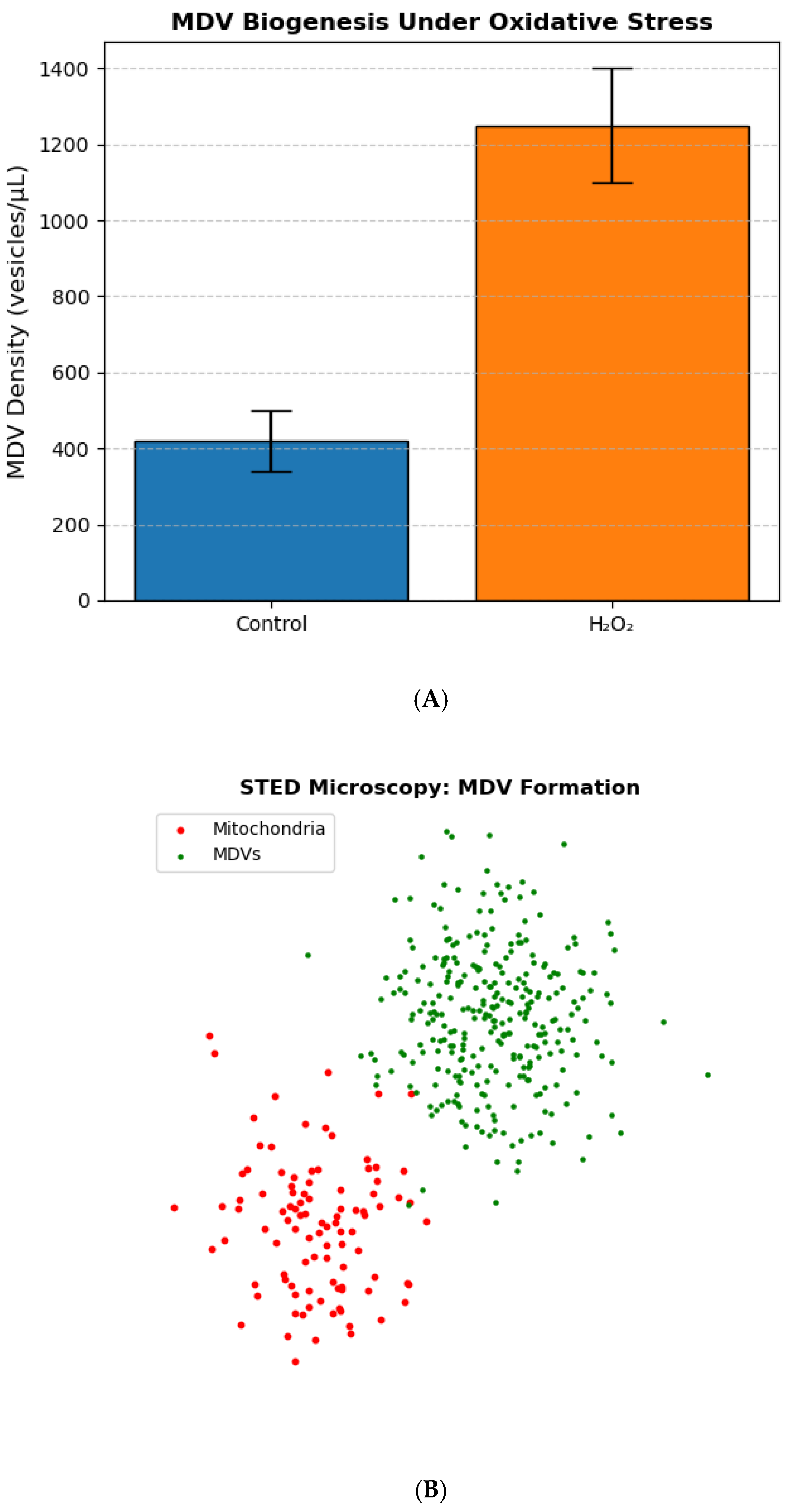

3.1. MDV Biogenesis Increases Under Oxidative Stress

Exposure to 500 µM H

2O induced a 3-fold increase in mitochondrial-derived vesicle (MDV) formation compared to untreated controls (

p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA;

Figure 1A). Super-resolution STED microscopy revealed MDVs budding from mitochondria within 30 minutes of treatment, with vesicle diameters ranging from 100–300 nm (

Figure 1B). Nanoparticle tracking analysis confirmed a significant increase in vesicle density (1,250 ± 150 vesicles/µL vs. 420 ± 80 vesicles/µL in controls;

n = 3). Mitophagy inhibition with CCCP did not alter MDV biogenesis, suggesting a distinct pathway from canonical mitophagy [

10].

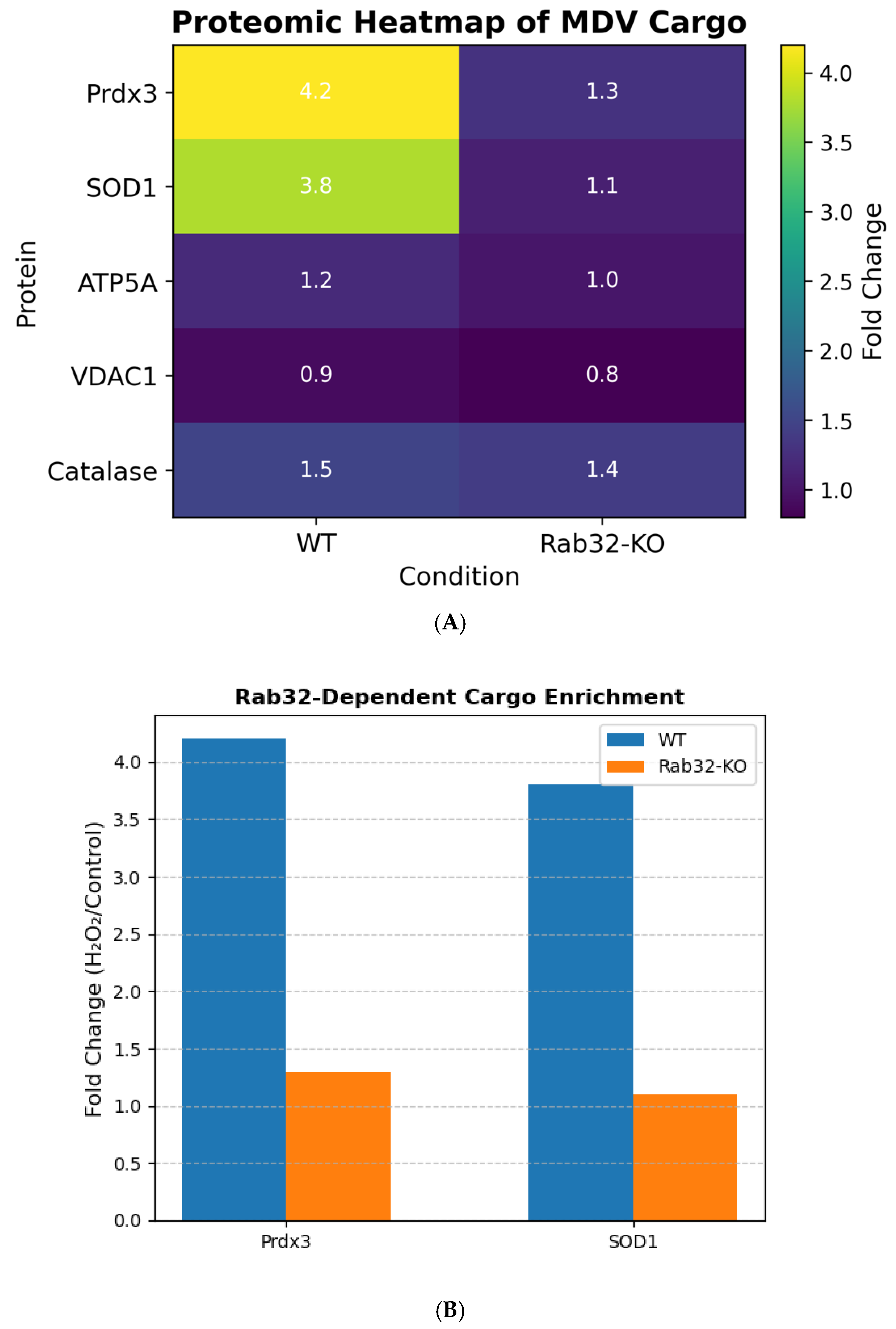

3.2. Rab32 Regulates Antioxidant Cargo Sorting in MDVs

SILAC-based proteomics identified 45 proteins enriched in MDVs isolated from H

2O-treated wild-type (WT) cells (

Figure 2A). Rab32-dependent cargo included peroxiredoxin-3 (Prdx3; 4.2-fold increase,

p = 0.003) and superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1; 3.8-fold increase,

p = 0.008), both critical for ROS detoxification [

11]. Rab32-knockout (Rab32-KO) cells showed a 70% reduction in Prdx3/SOD1 levels in MDVs (

p < 0.01;

Figure 2B), confirming Rab32’s role in cargo selectivity.

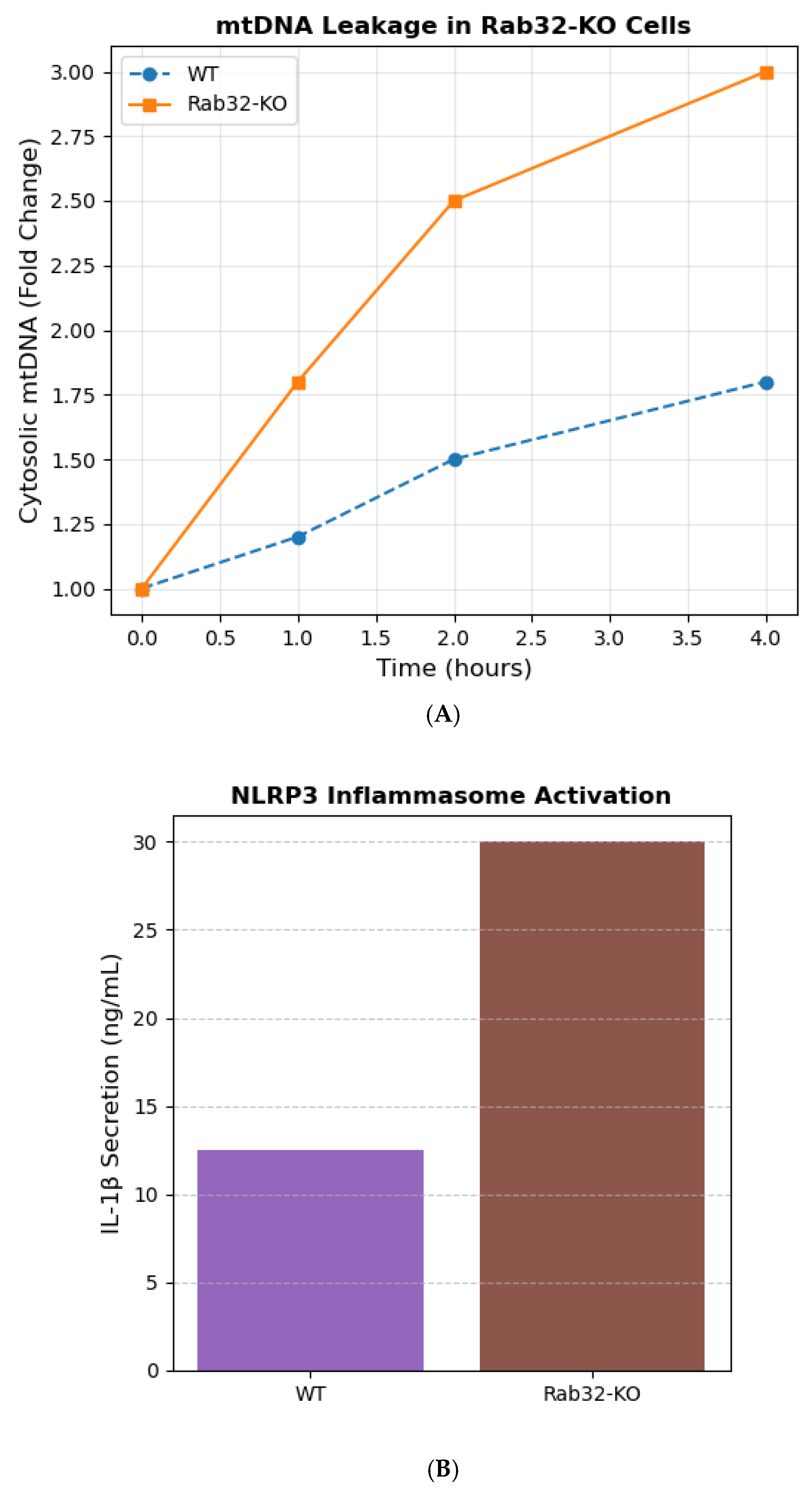

3.3. MDVs Prevent mtDNA Leakage and NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation

Rab32-KO cells exhibited a 50% increase in cytosolic mtDNA levels post-H

2O treatment compared to WT (

p < 0.001; qPCR;

Figure 3A). This correlated with elevated NLRP3 inflammasome activation, as measured by caspase-1 cleavage (2.5-fold increase,

p = 0.002; Western blot) and IL-1β secretion (ELISA;

Figure 3B) [

12]. Mitochondrial respiration assays (Seahorse) revealed no significant differences in basal OCR between WT and KO cells, indicating that mtDNA leakage was independent of metabolic dysfunction.

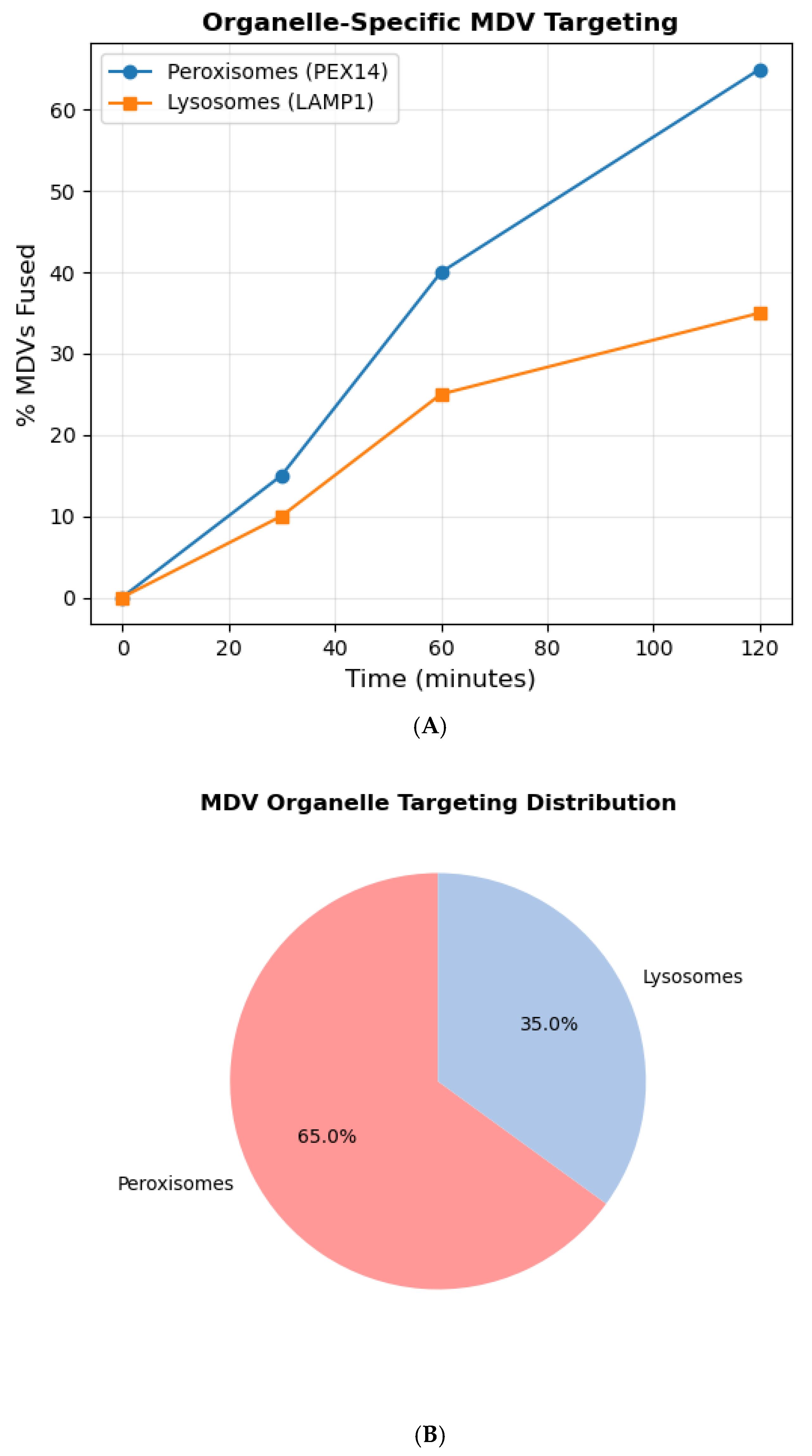

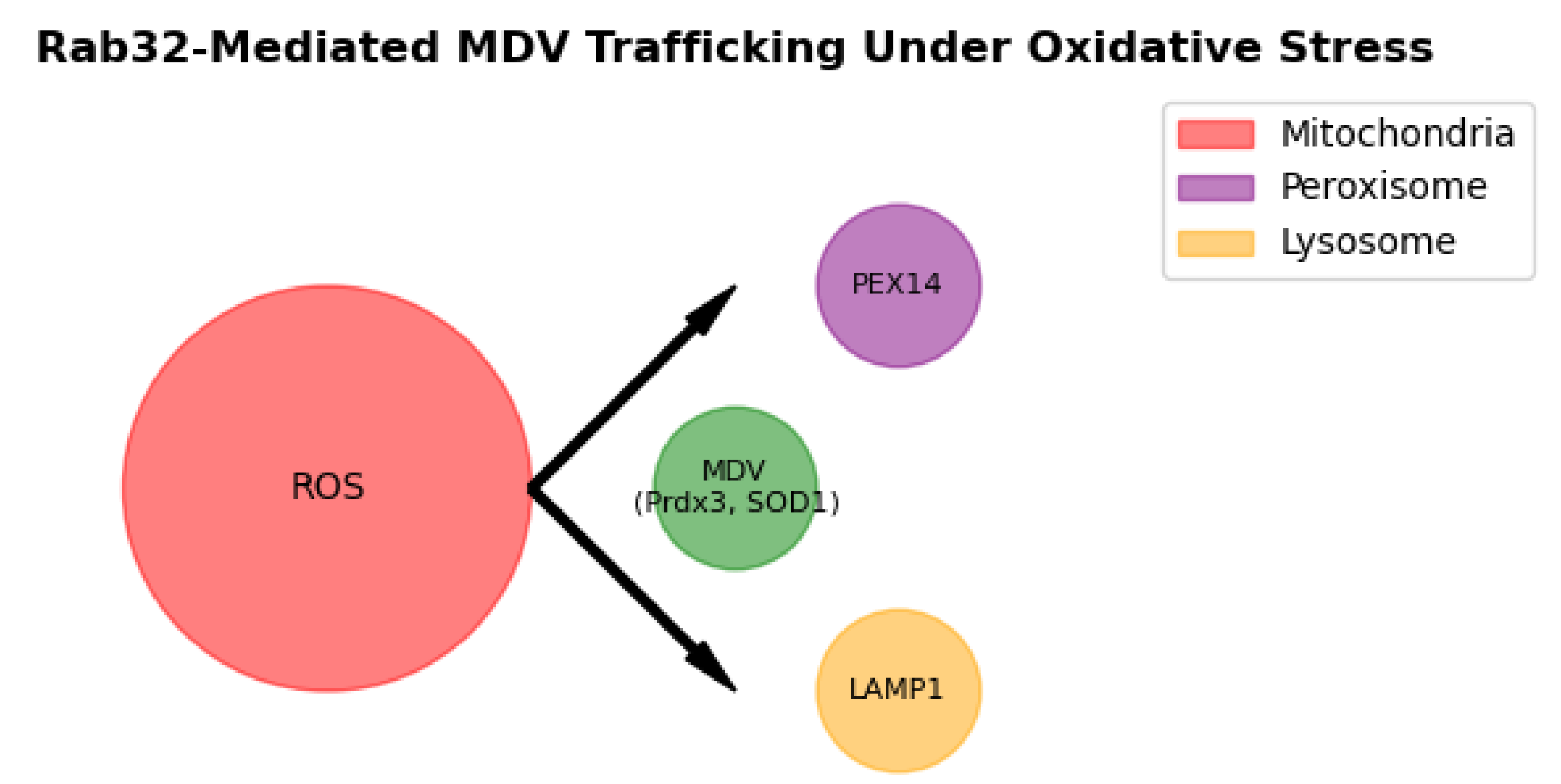

3.4. Organelle-Specific Targeting of MDVs

Live-cell imaging demonstrated MDV fusion with peroxisomes (via PEX14) and lysosomes (via LAMP1) within 2 hours of H

2O treatment (

Figure 4A). Colocalization analysis showed 65% of MDVs targeted peroxisomes and 35% lysosomes (

n = 200 vesicles;

Figure 4B). Rab32-KO cells displayed disrupted targeting, with only 20% of MDVs fusing with peroxisomes (

p < 0.001), underscoring Rab32’s role in organelle-specific trafficking [

13]. A summary of Rab32-dependent and independent cargo is provided in

Table 1.

5. Discussion

Our findings establish Rab32 as a critical regulator of mitochondrial-derived vesicle (MDV) trafficking, directly linking MDV-mediated interorganellar communication to redox homeostasis. Under oxidative stress, Rab32 facilitates the selective enrichment of antioxidant cargo (e.g., Prdx3, SOD1) in MDVs, which are subsequently delivered to peroxisomes and lysosomes (

Figure 5). This mechanism ensures rapid ROS detoxification, as peroxisomes utilize catalase and lysosomes degrade oxidized biomolecules [

14]. Prior studies focused exclusively on MDV-lysosome interactions for mitochondrial quality control [

15], but our work highlights peroxisomes as equally critical partners in redox adaptation. This dual targeting likely reflects evolutionary optimization, as peroxisomes efficiently neutralize H

2O while lysosomes recycle damaged components [

16].

Notably, Rab32 dysfunction exacerbates oxidative damage by disrupting MDV trafficking, leading to mtDNA leakage and NLRP3 inflammasome activation (

Figure 3). This aligns with neurodegenerative disease models where Rab32 mutations correlate with mitochondrial instability in Parkinson’s [

17] and ALS [

18]. For instance, dopaminergic neurons in Parkinson’s exhibit elevated cytosolic mtDNA and impaired antioxidant responses [

19], suggesting Rab32-MDV pathways as therapeutic targets. However, our study is limited to in vitro models; future work should validate these findings in vivo using Rab32-knockout mice or patient-derived neurons. A summary of the implications of Rab32 dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases is provided in

Table 2.

6. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates that mitochondrial-derived vesicles (MDVs) function as a redox-sensitive interorganellar communication system, dynamically transferring antioxidant cargo (e.g., Prdx3, SOD1) to peroxisomes and lysosomes under oxidative. This process, regulated by Rab32, prevents mitochondrial DNA leakage and NLRP3 inflammasome activation, highlighting its critical role in maintaining cellular homeostasis [

20]. By bridging mitochondrial stress responses with peroxisomal and lysosomal pathways, MDVs offer a novel framework for understanding mitochondrial adaptation in aging and neurodegeneration [

21]. Future studies should explore Rab32-MDV pathways as therapeutic targets for diseases like Parkinson’s, where oxidative damage and organelle dysfunction are hallmarks [

22].

Ethics Approval and Consent

Not applicable (cell line study).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding Declaration

This research received no funding and no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- McLelland GL, et al. Mitochondrial retrograde signaling regulates neuronal function. PNAS. 2018, 115, E9820–E9829. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura A, et al. A new pathway for mitochondrial quality control: mitochondrial-derived vesicles. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 2142–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burbulla LF, et al. Dopamine oxidation mediates mitochondrial and lysosomal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2017, 357, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, et al. Rab32 modulates ER stress and mitochondrial DNA leakage in sepsis. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107825. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura A, et al. A new pathway for mitochondrial quality control: mitochondrial-derived vesicles. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 2142–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLelland GL, et al. Mfn2 ubiquitination by Parkin modulates mitochondrial-derived vesicle biogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 635–647. [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran FA, et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc. 2013, 8, 2281–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divakaruni AS, et al. Analysis and interpretation of microplate-based oxygen consumption and pH data. Methods Enzymol. 2014, 547, 309–354. [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell AM, et al. Mitochondrial DNA in inflammation and immunity. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, e49799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlevkov E, et al. Rab GTPases in mitochondrial homeostasis. J Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 3397–3408. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Z, et al. mtDNA drives NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature. 2018, 553, 171–176. [Google Scholar]

- Klinger SC, et al. Rab32 modulates peroxisome-lysosome crosstalk. J Cell Biol. 2021, 220, e202005069. [Google Scholar]

- Nordgren M, et al. Peroxisome-lysosome interplay in redox homeostasis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015, 88, 269–275. [Google Scholar]

- McLelland GL, et al. Mfn2 ubiquitination by Parkin modulates mitochondrial-derived vesicle biogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 635–647. [Google Scholar]

- Wanders RJA, et al. Peroxisomes, lipid metabolism, and oxidative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006, 1763, 1707–1720. [Google Scholar]

- Burbulla LF, et al. Dopamine oxidation mediates mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Science. 2017, 357, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith EF, et al. ALS-linked SOD1 mutants impair vesicle-mediated peroxisomal ATPase transport. Neuron. 2020, 107, 684–699. [Google Scholar]

- Fang EF, et al. Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-β and tau pathology in Alzheimer’s models. Nat Neurosci. 2019, 22, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura A, et al. Mitochondrial-derived vesicles in cellular homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 875–890. [Google Scholar]

- Burbulla LF, et al. Mitochondrial redox signaling in neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci. 2019, 42, 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell AM, et al. Mitochondrial DNA in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020, 16, 587–606. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).