Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- How the availability and secure GE supply be ensured to generate sustainable fuels (SF), along with the direct primary applications of GE?

- How we will address the water availability for electrolysis applications, considering future possible water scarcity and increased SH demand?

- What is the impact of limited RE potential on SH generation in Bavaria?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Hydrogen Production and Perceived Use Landscape.

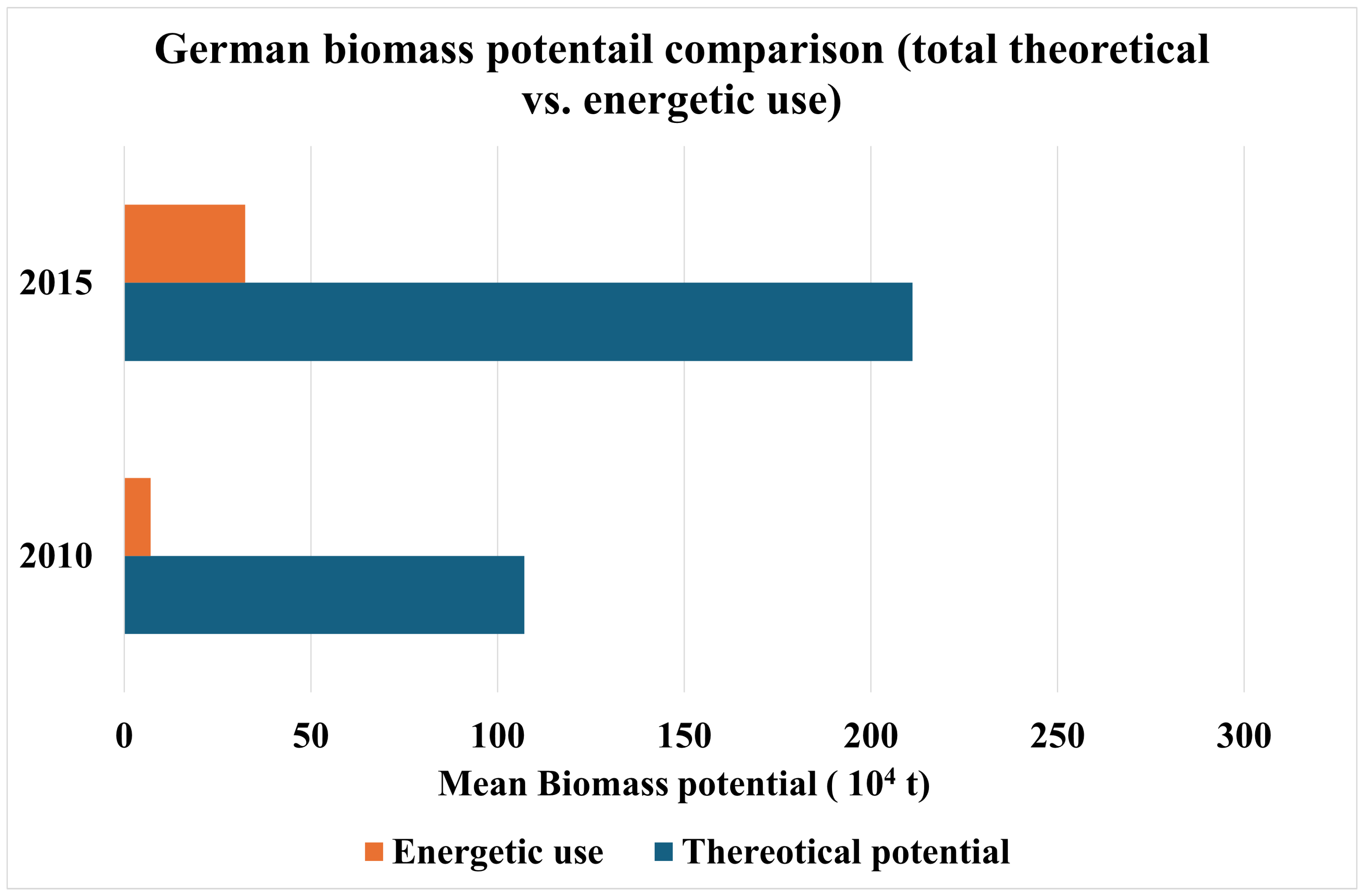

2.2. Bio-Waste Processing Landscape.

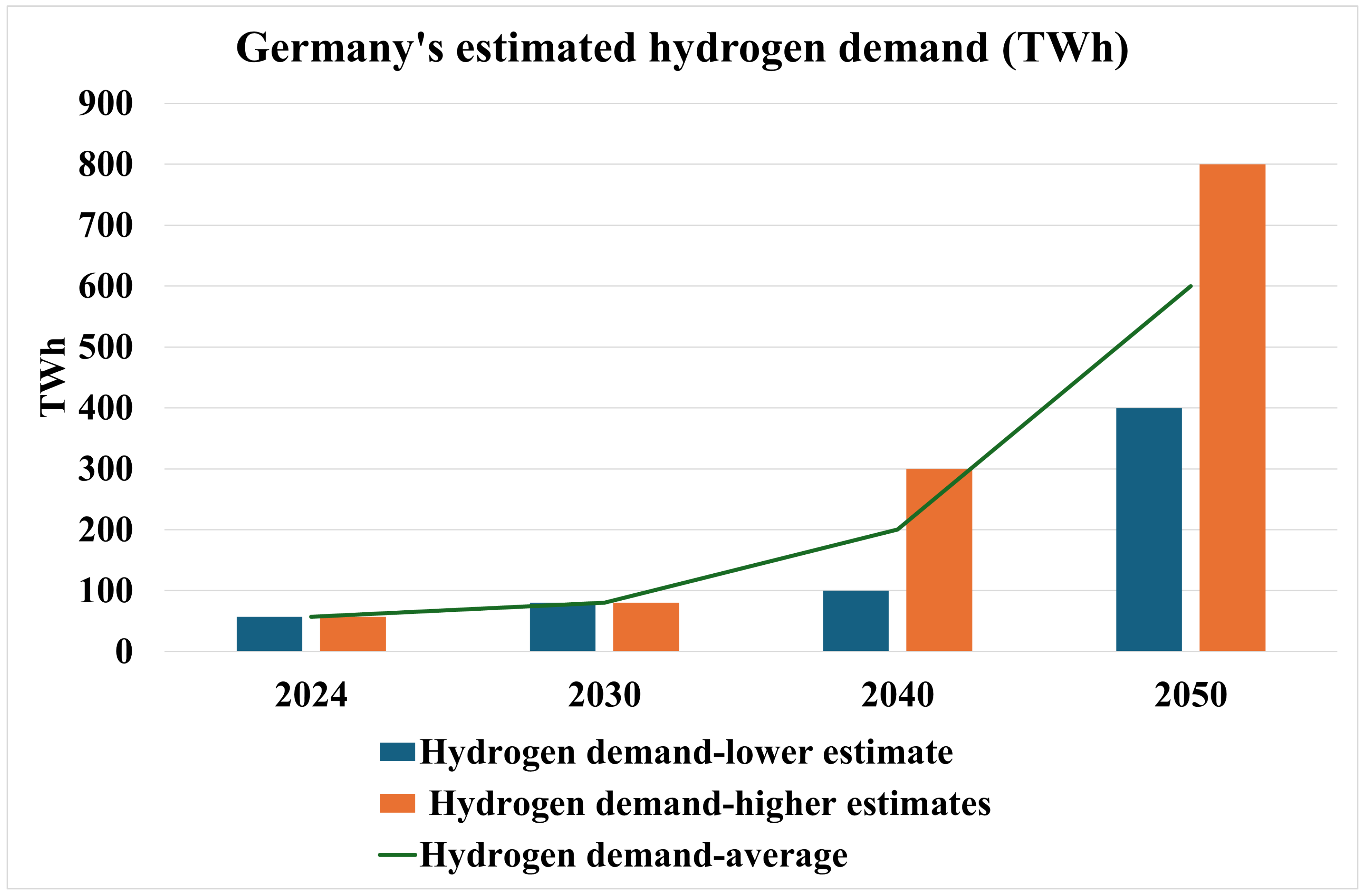

2.3. Hydrogen Demand Landscape

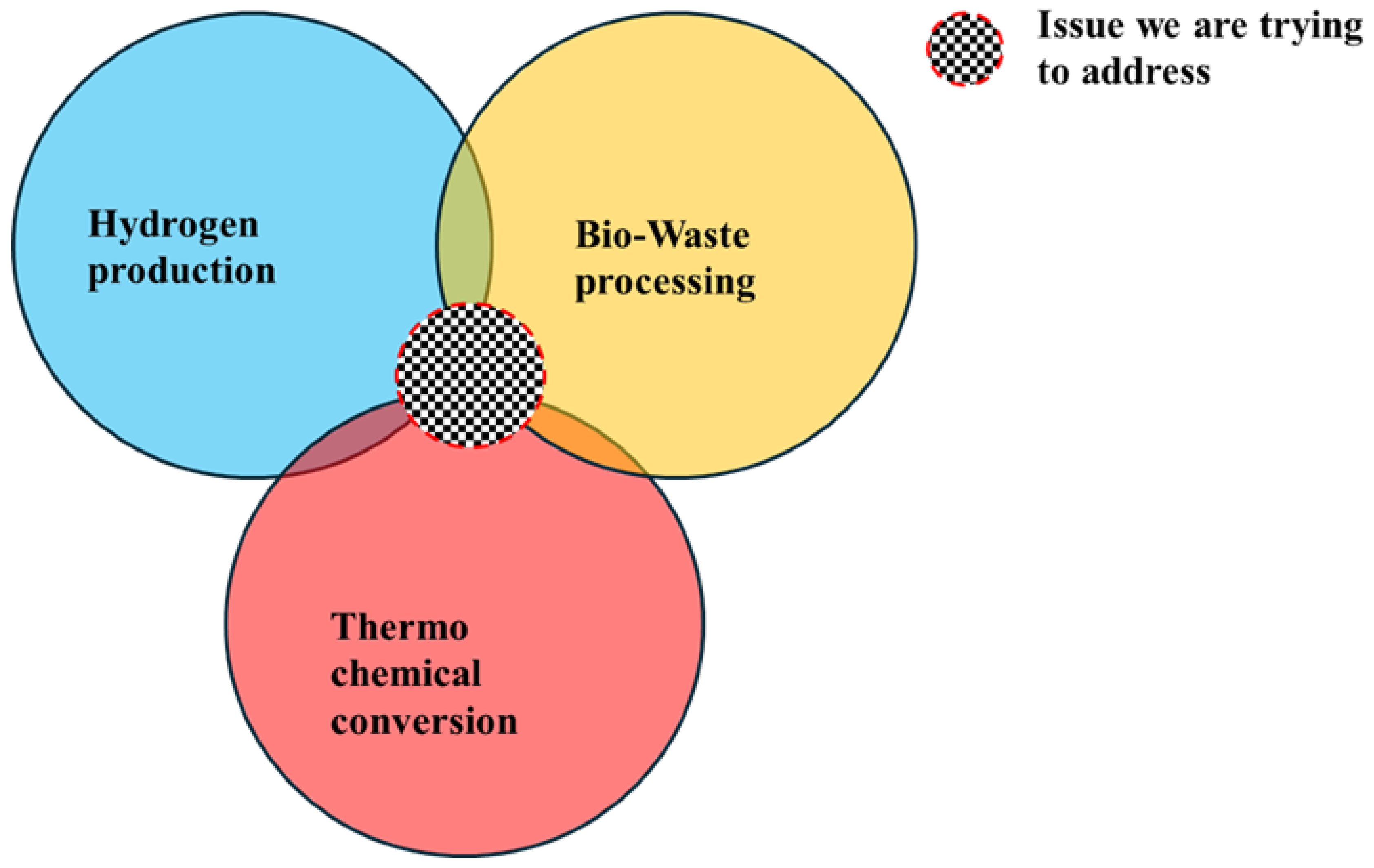

2.4. Identification of Research Gap

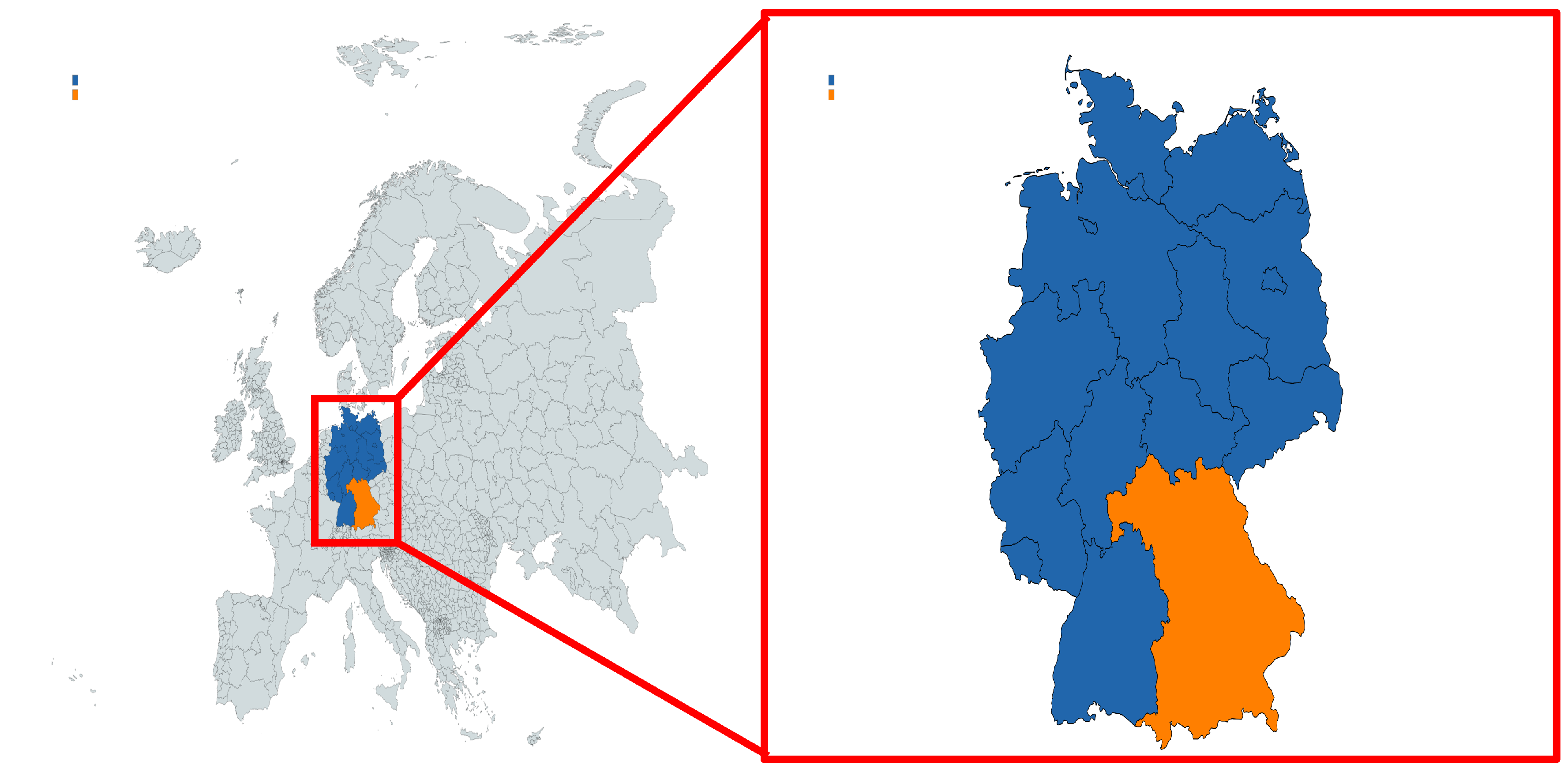

3. Bavaria Region

- Spatial expansion of capacity (such as expansion of electrical grid)

- Temporal expansion of the capacity (employing energy storage options)

- Improved flexibility (by providing gas as well as hydrogen based power generation options)

4. Methodology

4.1. Input Materials Considered

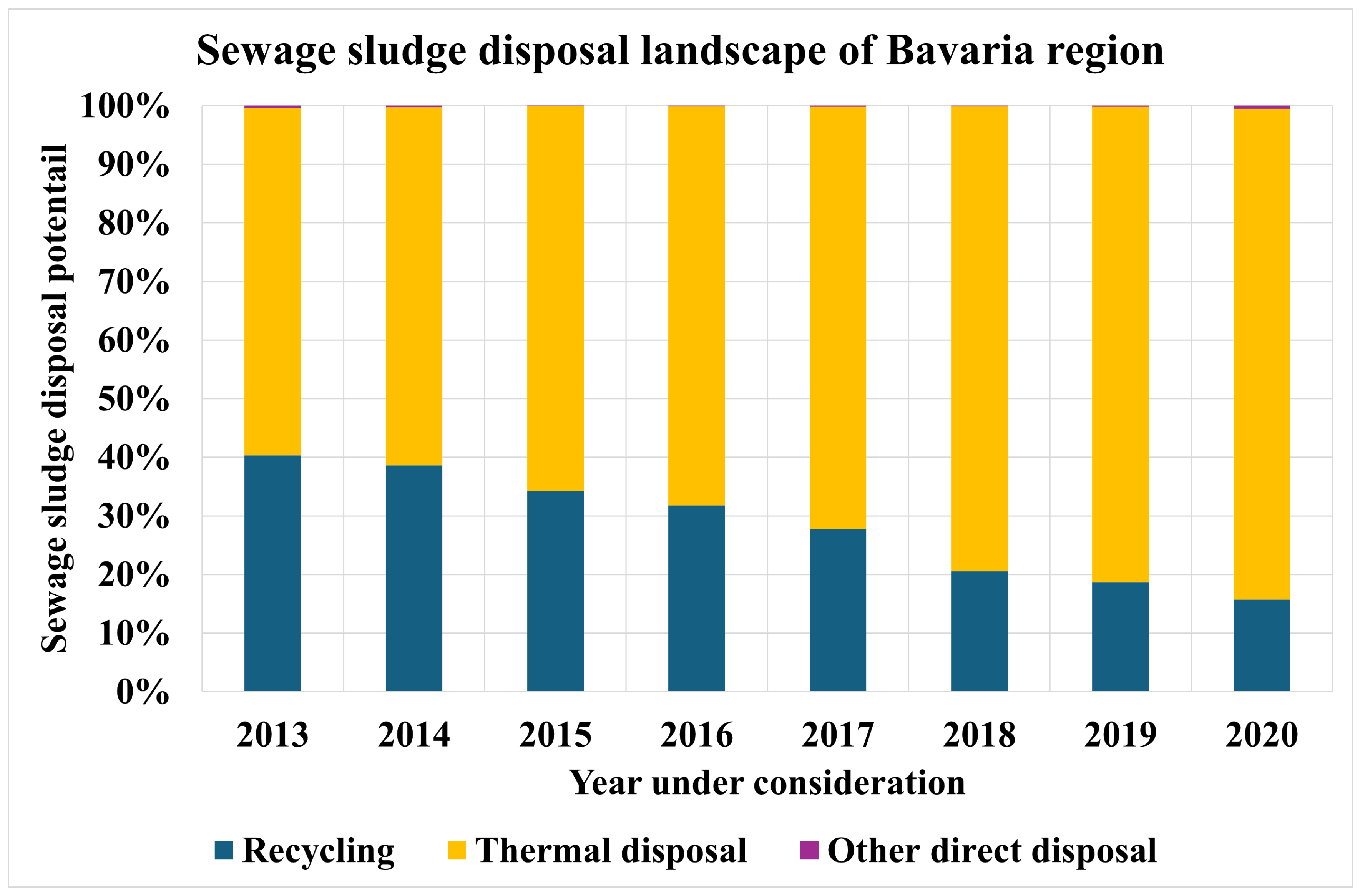

- recycling

- thermal disposal

- other methods of direct disposal

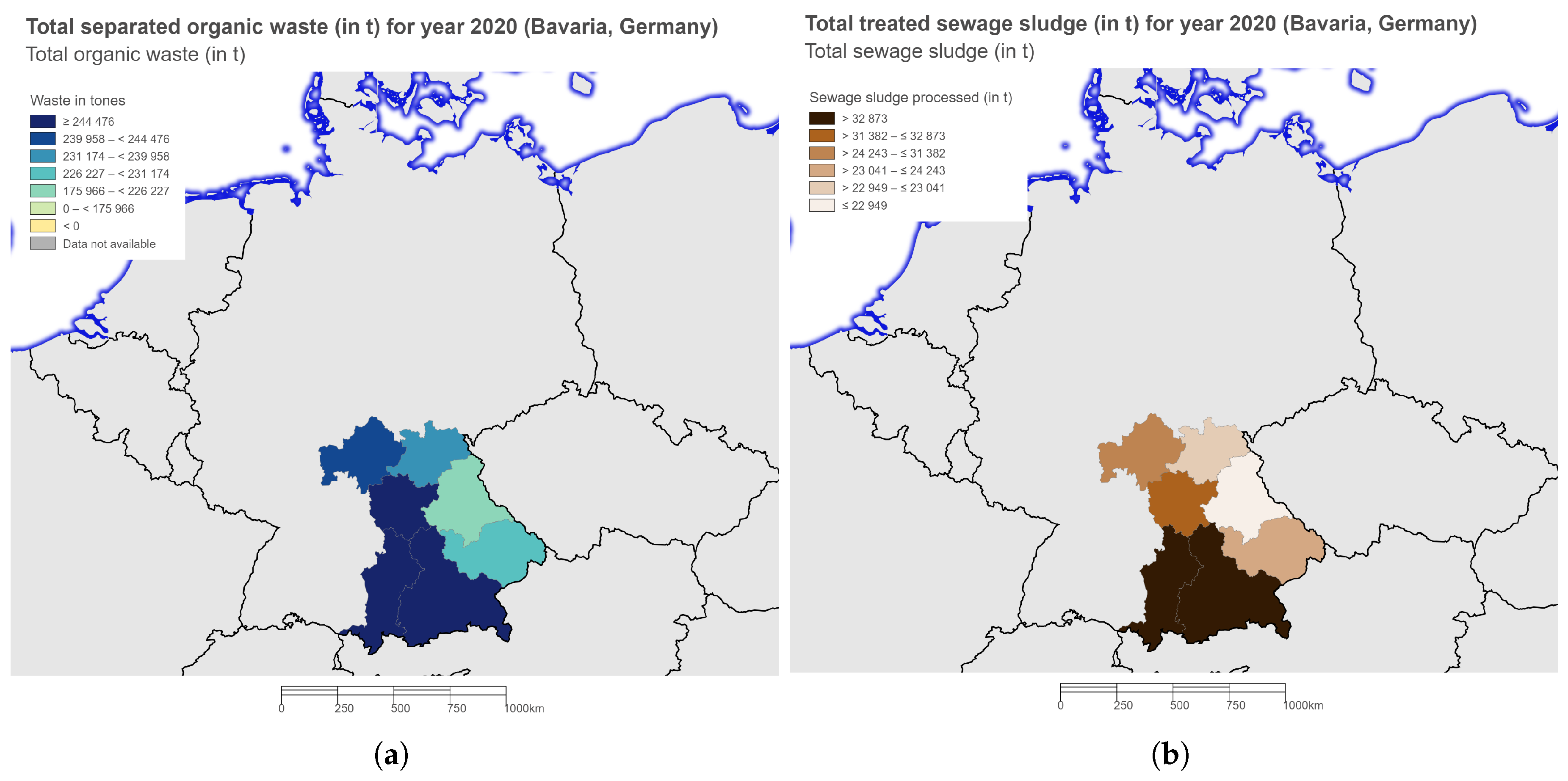

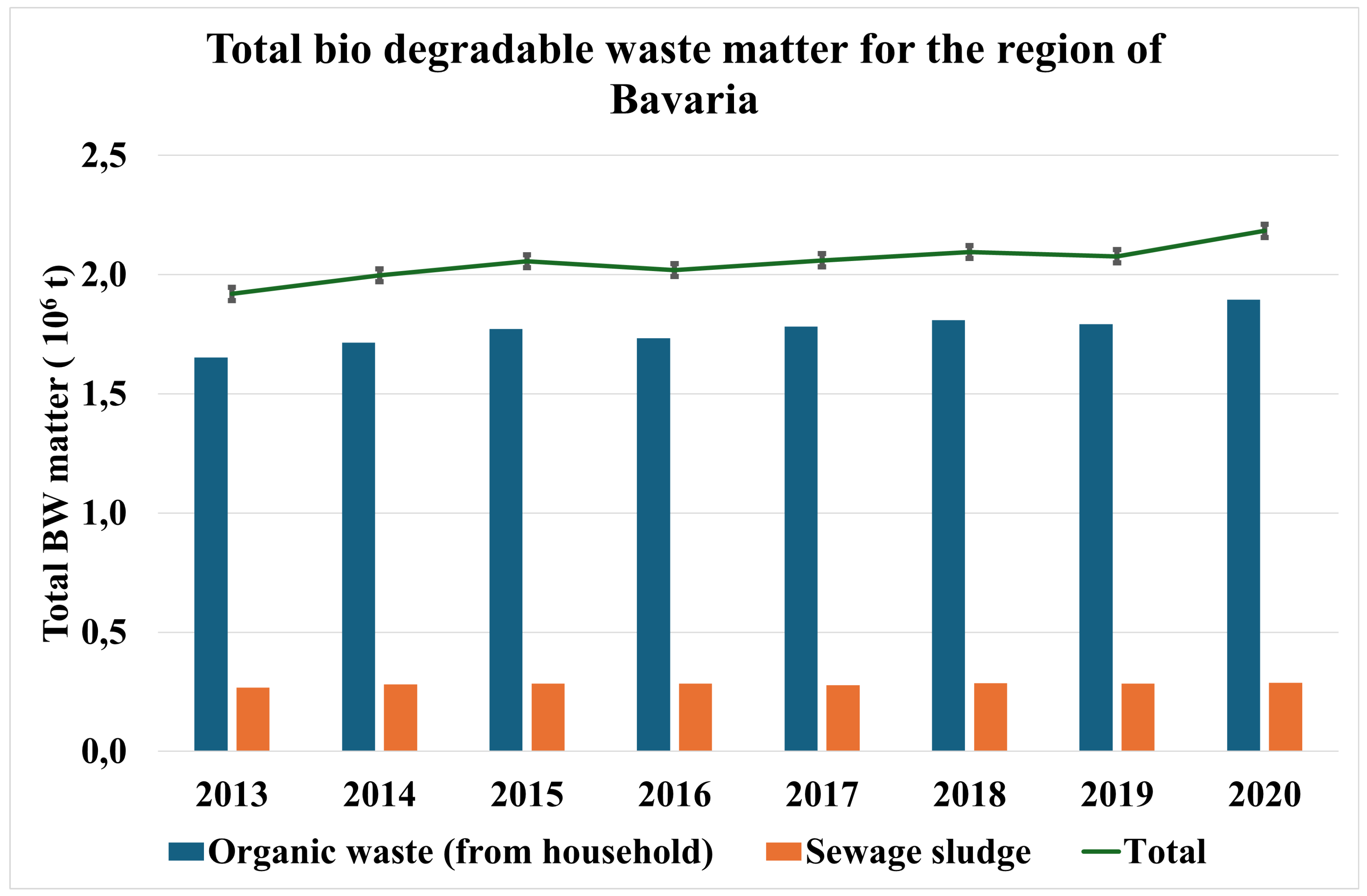

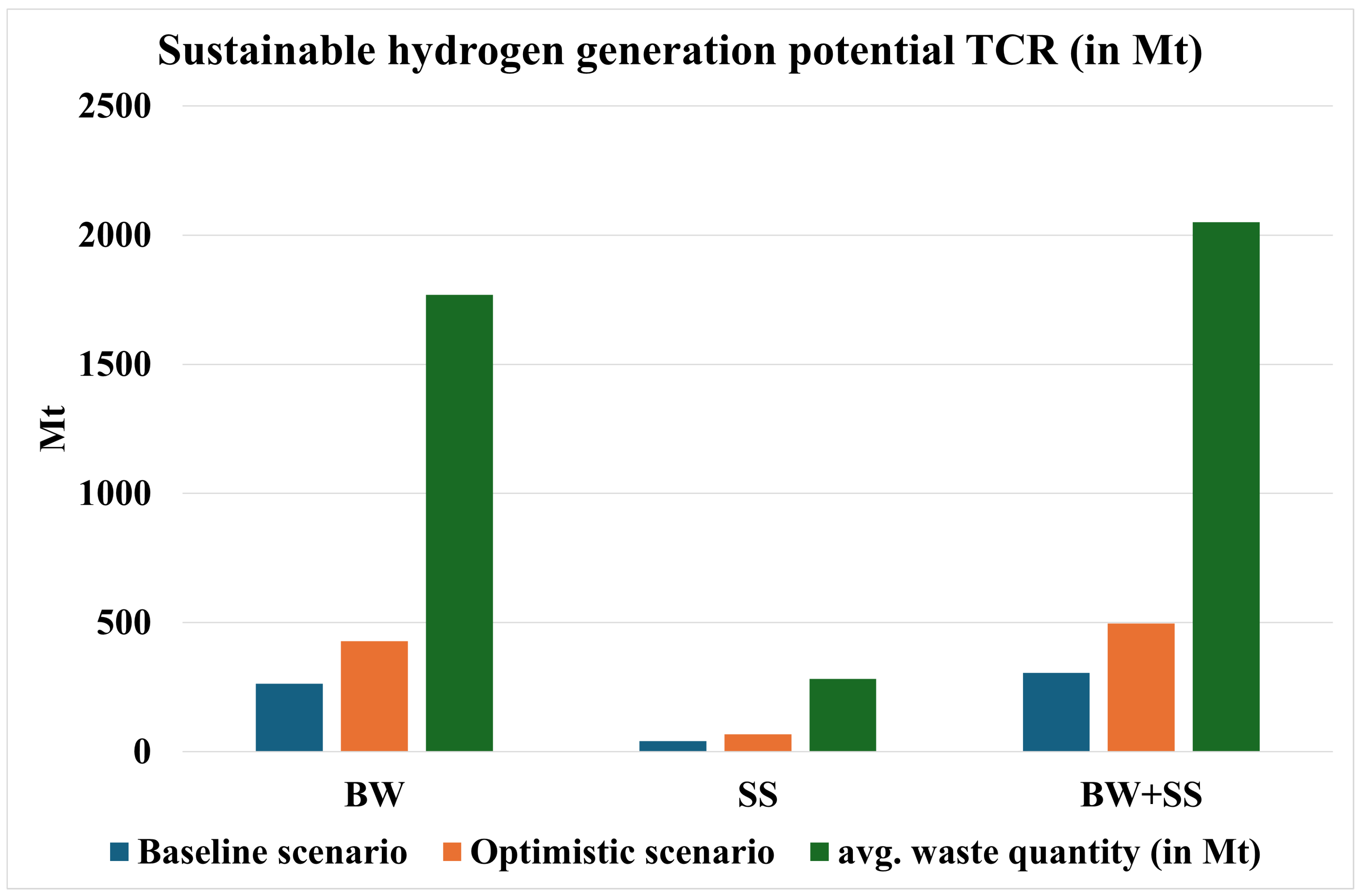

| Total organic waste (in 1000 t) | |

|---|---|

| BW | 1768.881 |

| SS | 281.70 |

| Total avg. | 2050.59 |

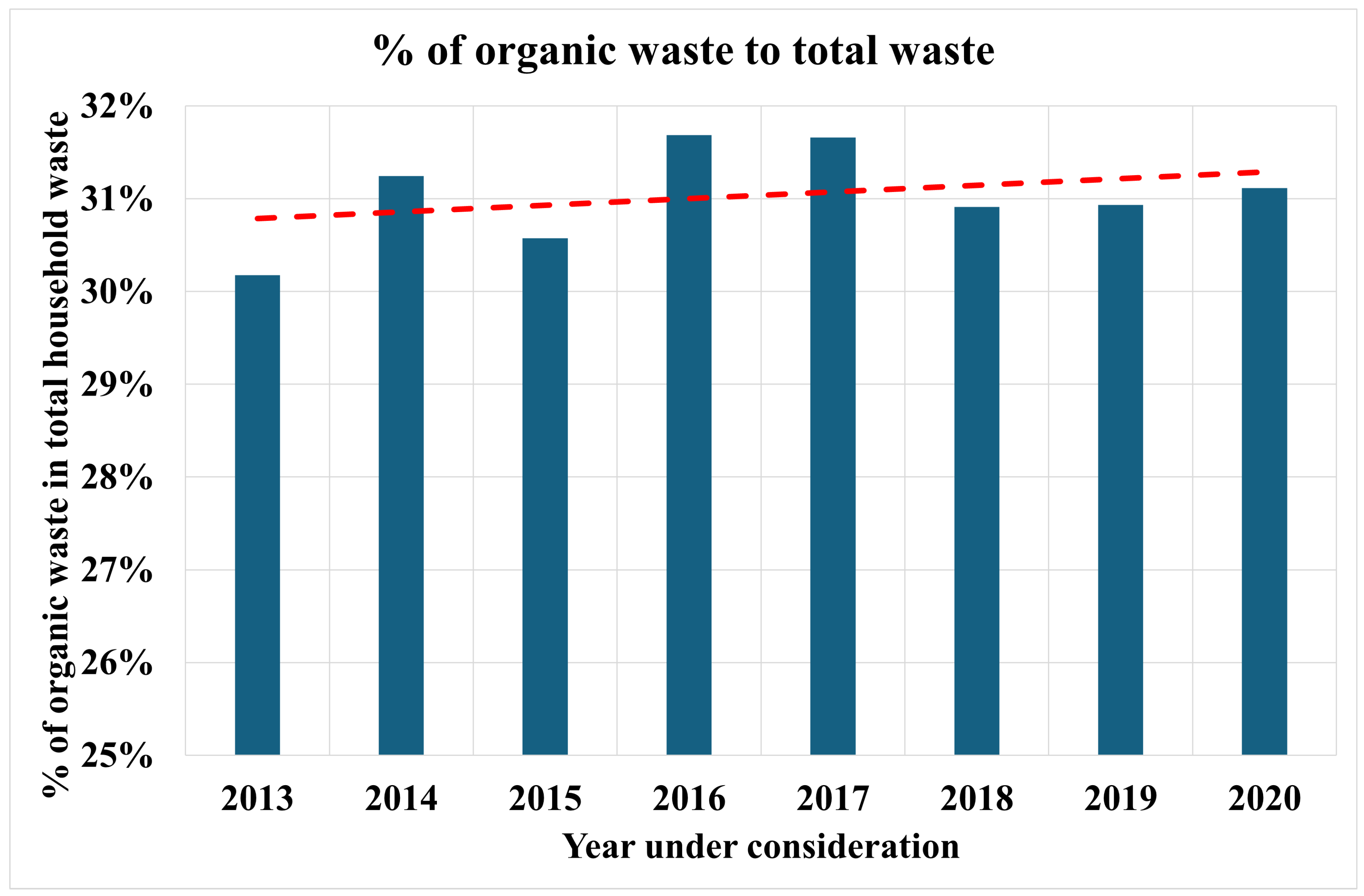

4.2. Assessing Organic Waste (Domestic BW and SS) generation landscape for Bavarian region.

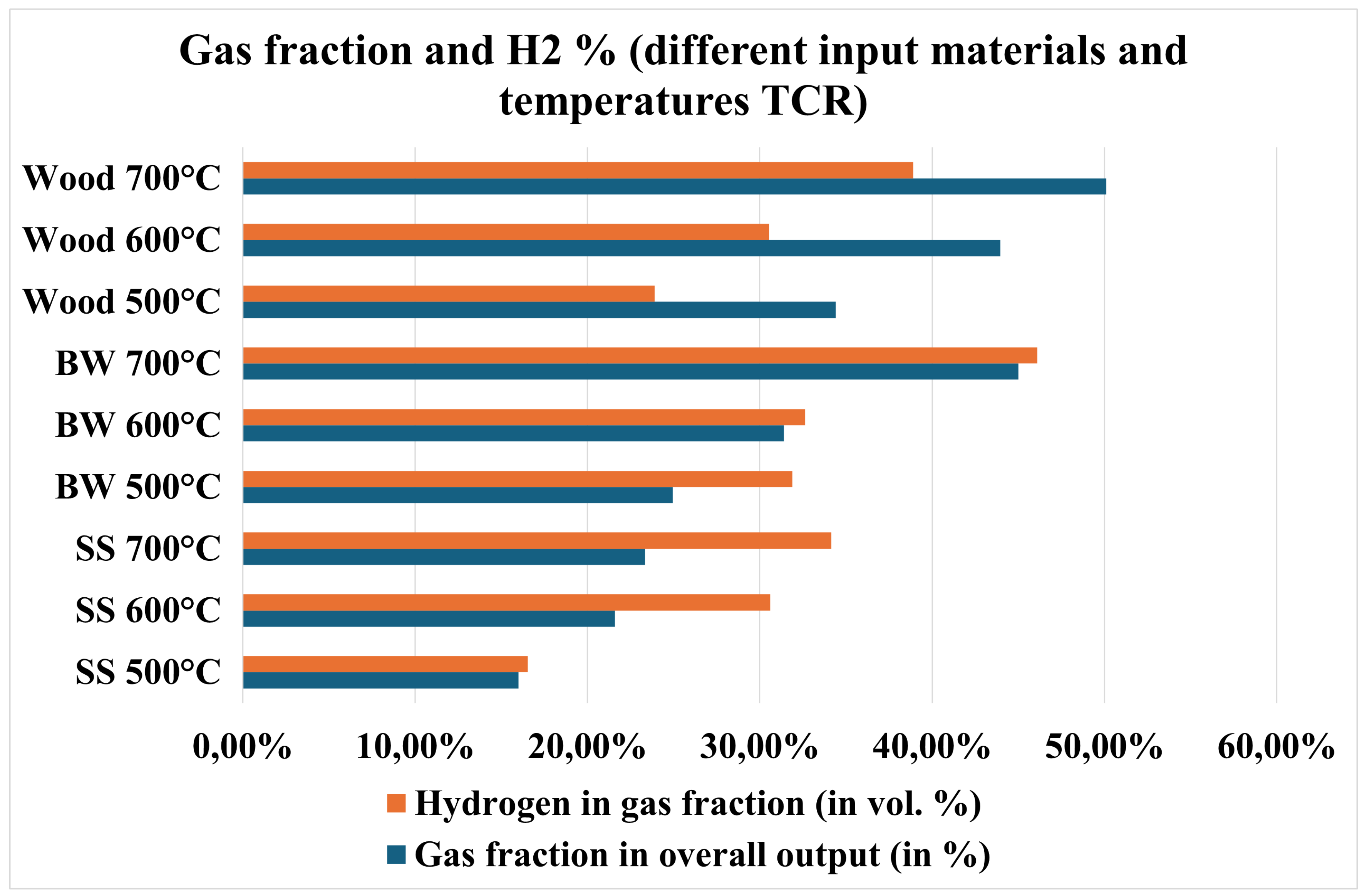

4.3. Accessing Thermochemical Conversion Potential for SH Production.

- H fraction in volume percentage

- and other gasses in volume percentage

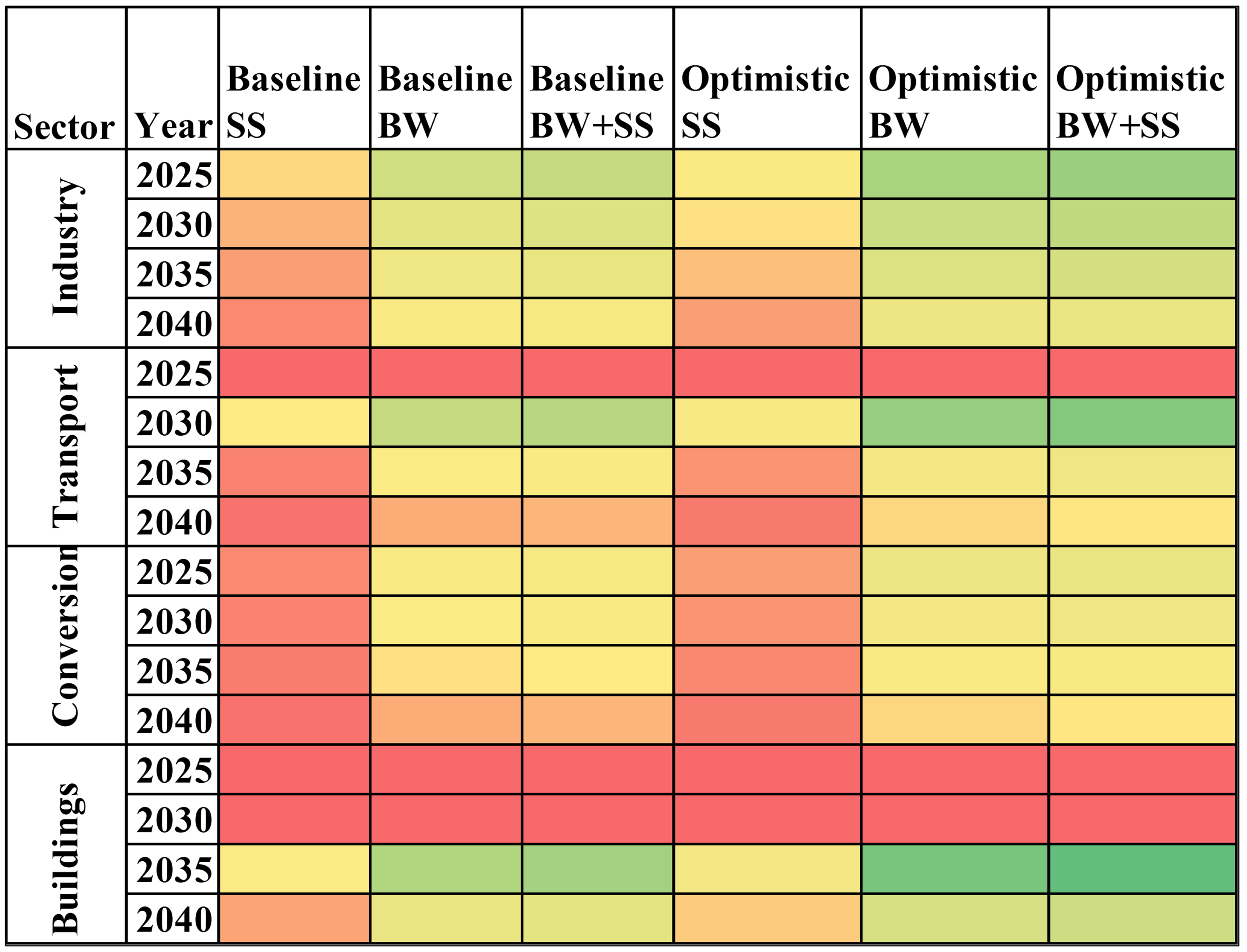

4.4. Scenario Creation

- Baseline ( 27% gas output from TCR process with 55% H fraction in it. )

- Optimistic (44% gas output from TCR process with 55% H fraction in it.)

- BW only (Baseline)

- SS only (Baseline)

- BW+SS (Baseline)

- BW only (Optimistic)

- SS only (Optimistic)

- BW+SS (Optimistic)

- 1kg of H = 33.3 kWh equivalent of H

- 1 TWh equivalent H = 30.030 x 10 Mt of H

5. Results and Discussion

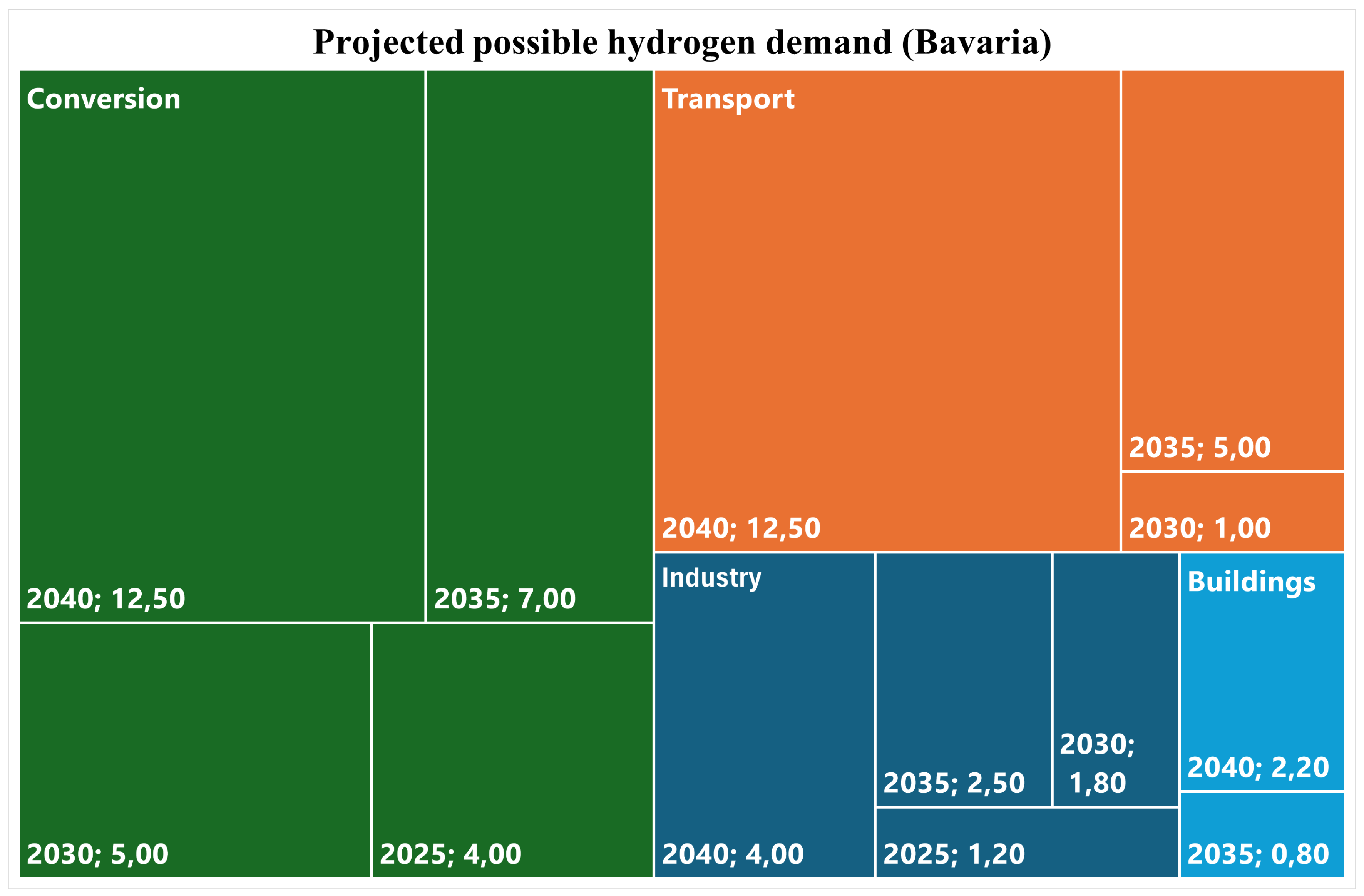

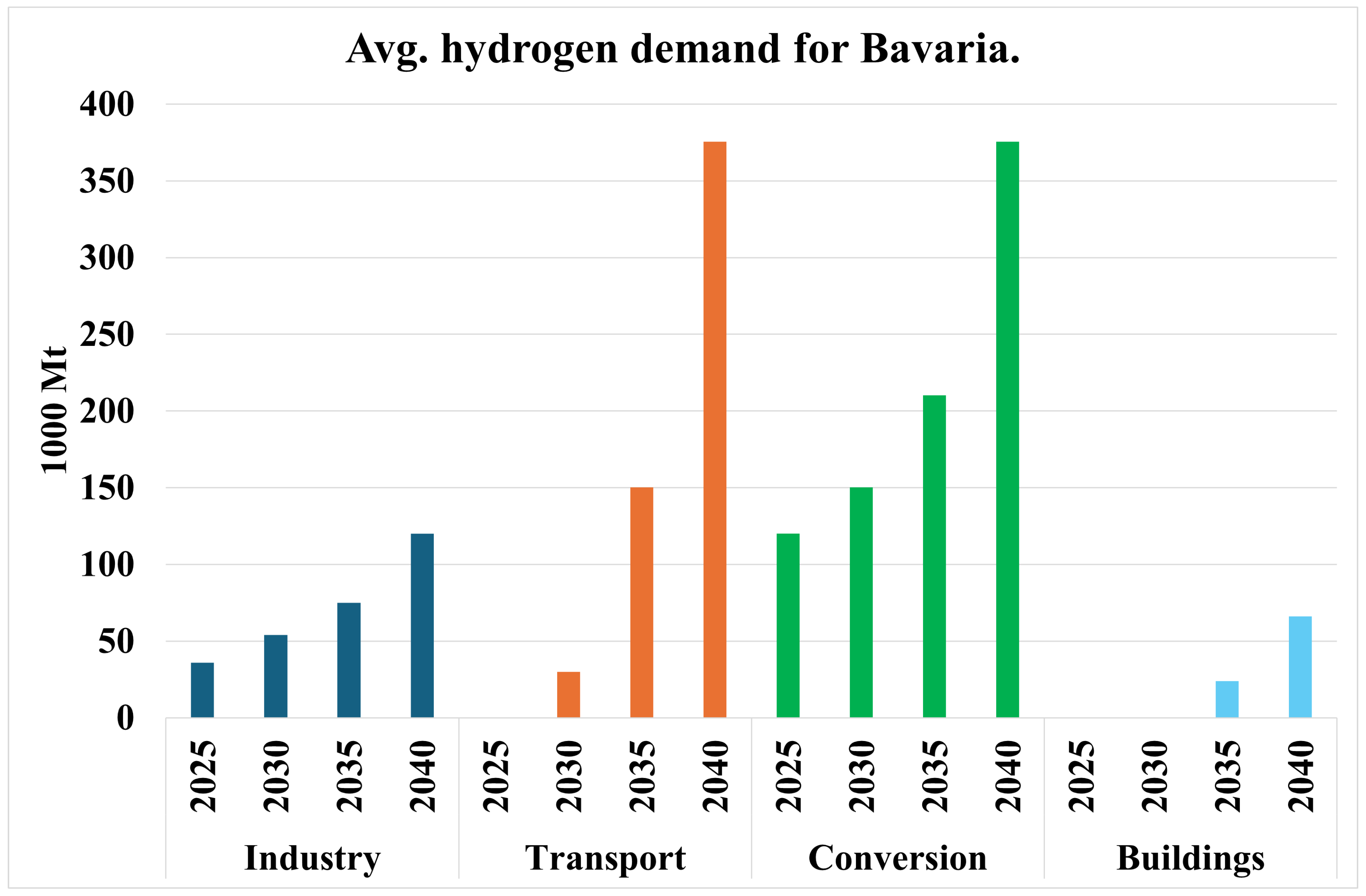

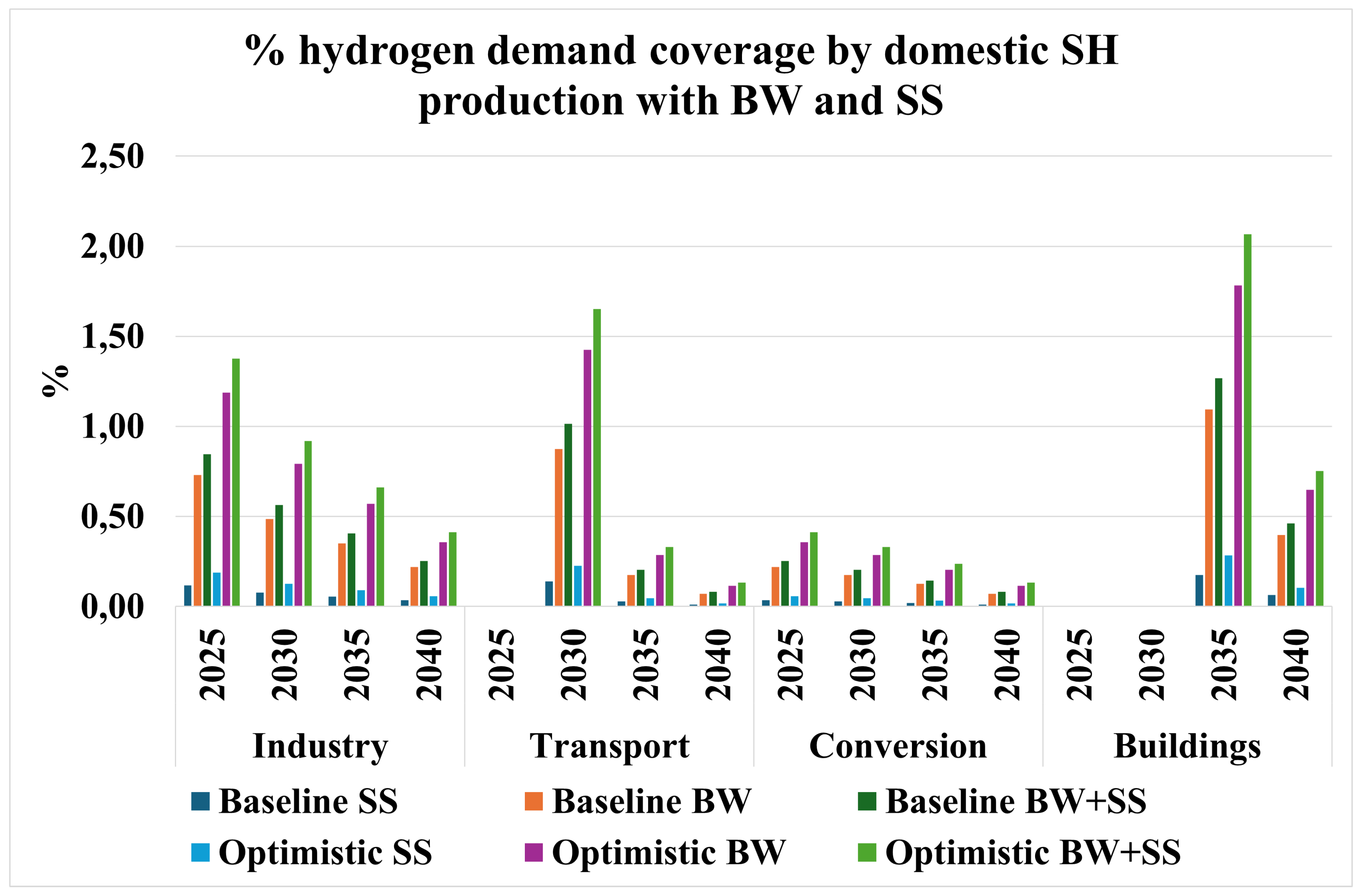

5.1. Industry

5.2. Transportation

5.3. Conversion

5.4. Buildings

6. Conclusions

7. Future Work

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IEA, B. World Energy Outlook. IEA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Plan, A.; et al. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. European Commission 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goers, S.; Rumohr, F.; Fendt, S.; Gosselin, L.; Jannuzzi, G.M.; Gomes, R.D.; Sousa, S.M.; Wolvers, R. The role of renewable energy in regional energy transitions: An aggregate qualitative analysis for the partner regions Bavaria, Georgia, Québec, São Paulo, Shandong, Upper Austria, and Western Cape. Sustainability 2020, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhrich, K. CO2 emission factors for fossil fuels, German Environment Agency, 2016.

- Full, J.; Trauner, M.; Miehe, R.; Sauer, A. Carbon-negative hydrogen production (HyBECCS) from organic waste materials in Germany: how to estimate bioenergy and greenhouse gas mitigation potential. Energies 2021, 14, 7741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BMUV. Waste Management in Germany 2023. Technical report, Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection (BMUV), April 2023.

- Ouadi, M.; Jaeger, N.; Greenhalf, C.; Santos, J.; Conti, R.; Hornung, A. Thermo-Catalytic Reforming of municipal solid waste. Waste Management 2017, 68, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, R.; Shah, R.R. Hydrogen as energy carrier: Techno-economic assessment of decentralized hydrogen production in Germany. Renewable Energy 2021, 177, 915–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunow, P. Decentral Hydrogen. Energies 2022, 15, 2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welder, L.; Ryberg, D.S.; Kotzur, L.; Grube, T.; Robinius, M.; Stolten, D. Spatio-temporal optimization of a future energy system for power-to-hydrogen applications in Germany. Energy 2018, 158, 1130–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, J.; Bünger, U.; Crotogino, F.; Donadei, S.; Schneider, G.S.; Pregger, T.; Cao, K.K.; Heide, D. Hydrogen generation by electrolysis and storage in salt caverns: Potentials, economics and systems aspects with regard to the German energy transition. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 13427–13443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendziorski, M.; Göke, L.; von Hirschhausen, C.; Kemfert, C.; Zozmann, E. Centralized and decentral approaches to succeed the 100% energiewende in Germany in the European context–A model-based analysis of generation, network, and storage investments. Energy Policy 2022, 167, 113039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalchschmid, V.; Erhart, V.; Angerer, K.; Roth, S.; Hohmann, A. Decentral Production of Green Hydrogen for Energy Systems: An Economically and Environmentally Viable Solution for Surplus Self-Generated Energy in Manufacturing Companies? Sustainability 2023, 15, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.; Orehounig, K.; Grosspietsch, D.; Carmeliet, J. A comparison of storage systems in neighbourhood decentralized energy system applications from 2015 to 2050. Applied Energy 2018, 231, 1285–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahnaoui, A.; Wulf, C.; Dalmazzone, D. Optimization of hydrogen cost and transport technology in France and Germany for various production and demand scenarios. Energies 2021, 14, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzmann, D.; Heinrichs, H.; Lippkau, F.; Addanki, T.; Winkler, C.; Buchenberg, P.; Hamacher, T.; Blesl, M.; Linßen, J.; Stolten, D. Green hydrogen cost-potentials for global trade. international journal of hydrogen energy 2023, 48, 33062–33076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, Birgit Reinelt, D.W. Potenziale einer Wasserstoffgewinnung durch Vergasung von Gewerbeabfall. Technical report, bifa Umweltinstitut. May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, V.C.; Iervolino, G.; Tugnoli, A.; Cozzani, V. Techno-economic and environmental sustainability of biomass waste conversion based on thermocatalytic reforming. Waste management 2020, 101, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naegeli de Torres, F.; Brödner, R.; Cyffka, K.-F.; Fais, A.; Kalcher, J.; Kazmin, S.; Meyer, R.; Radke, K.-S.; Richter, F.; Selig, M.; Wilske, B.; Thrän, D. DBFZ Resource Database: DE-Biomass Monitor. Biomass Potentials and Utilization of Biogenic Wastes and Residues in Germany 2010-2020 [Data set]. Zenodo, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, D.; Wolf, C.; Schulz, C.; Weber-Blaschke, G. Environmental impacts of various biomass supply chains for the provision of raw wood in Bavaria, Germany, with focus on climate change. Science of the Total Environment 2016, 539, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, K.; Rogers, H. A research agenda for circular food waste management in Bavaria. Transportation Research Procedia 2022, 67, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, E.C.; Istrate, I.A.; Ragazzi, M. Trends in the management of residual municipal solid waste. Environmental Technology 2009, 30, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A.U. Life cycle environmental assessment of municipal solid waste to energy technologies. Global Journal of Environmental Research 2009, 3, 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ateş, F.; Miskolczi, N.; Borsodi, N. Comparision of real waste (MSW and MPW) pyrolysis in batch reactor over different catalysts. Part I: Product yields, gas and pyrolysis oil properties. Bioresource technology 2013, 133, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Yin, L.; Wang, H.; He, P. Pyrolysis technologies for municipal solid waste: a review. Waste management 2014, 34, 2466–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wappler, M.; Unguder, D.; Lu, X.; Ohlmeyer, H.; Teschke, H.; Lueke, W. Building the green hydrogen market–Current state and outlook on green hydrogen demand and electrolyzer manufacturing. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 33551–33570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wietschel, M.; Zheng, L.; Arens, M.; Hebling, C.; Ranzmeyer, O.; Schaadt, A.; Hank, C.; Sternberg, A.; Herkel, S.; Kost, C.; et al. Metastudie wasserstoff-auswertung von Energiesystemstudien. Metastudie Wassserstoff 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wettengel, J. Germany’s future hydrogen needs significantly higher than expected. Technical report, Clean Energy Wire. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Scharf, H.; Sauerbrey, O.; Möst, D. What will be the hydrogen and power demands of the process industry in a climate-neutral Germany? Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 142354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemer, M.; Zheng, L.; Eckstein, J.; Wietschel, M.; Pieton, N.; Kunze, R.; et al. Future hydrogen demand: A cross-sectoral, global meta-analysis, Fraunhofer ISI Karlsruhe, 2022.

- Scheller, F.; Wald, S.; Kondziella, H.; Gunkel, P.A.; Bruckner, T.; Keles, D. Future role and economic benefits of hydrogen and synthetic energy carriers in Germany: a review of long-term energy scenarios. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2023, 56, 103037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Global energy transformation: A roadmap to 2050 (2019 edition), International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi. Technical report, IRENA. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Council, H.; Company, M. Hydrogen for Net-Zero A critical cost-competitive energy vector. Technical report, Hydrogen Council and McKinsey & Company. November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Philipp Runge, S.D. Hydrogen Roadmap Bavaria Perspectives and recommendations towards the ramp-up of the Bavarian hydrogen economy. Technical report, Hydrogen Center Bavaria. May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bique, A.O.; Zondervan, E. An outlook towards hydrogen supply chain networks in 2050—Design of novel fuel infrastructures in Germany. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2018, 134, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- München, S. Stadtwerke München, Verlag nicht ermittelbar. 1997.

- Lee, J.; Hong, S.; Cho, H.; Lyu, B.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.; Moon, I. Machine learning-based energy optimization for on-site SMR hydrogen production. Energy Conversion and Management 2021, 244, 114438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargbo, H.O.; Zhang, J.; Phan, A.N. Optimisation of two-stage biomass gasification for hydrogen production via artificial neural network. Applied Energy 2021, 302, 117567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- für Statistik, B.L. Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- National Bioeconomy Strategy, German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture. July 2020.

- Günther, S.; Karras, T.; Naegeli de Torres, F.; Semella, S.; Thrän, D. Temporal and spatial mapping of theoretical biomass potential across the European Union. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, N.; Apfelbacher, A.; Jäger, N.; Daschner, R.; Stenzel, F.; Hornung, A. Thermo-chemical conversion of biomass and upgrading to biofuel: The Thermo-Catalytic Reforming process–A review. Biofuels, Bioproducts and Biorefining 2019, 13, 822–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, R.; Jäger, N.; Neumann, J.; Apfelbacher, A.; Daschner, R.; Hornung, A. Thermocatalytic reforming of biomass waste streams. Energy Technology 2017, 5, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Singh, B. Selectively closing recycling centers in Bavaria: Reforming waste-management policy to reduce disparity. Networks 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornung, A.; Jahangiri, H.; Ouadi, M.; Kick, C.; Deinert, L.; Meyer, B.; Grunwald, J.; Daschner, R.; Apfelbacher, A.; Meiller, M.; et al. Thermo-Catalytic Reforming (TCR)–An important link between waste management and renewable fuels as part of the energy transition. Applications in Energy and Combustion Science 2022, 12, 100088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, A.S.; Brammer, J.G.; Hornung, A.; Steele, A.; Poulston, S. The intermediate pyrolysis and catalytic steam reforming of Brewers spent grain. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2013, 103, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaas, M.; Greenhalf, C.; Ouadi, M.; Jahangiri, H.; Hornung, A.; Briens, C.; Berruti, F. The effect of torrefaction pre-treatment on the pyrolysis of corn cobs. Results in Engineering 2020, 7, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, J.; Meyer, J.; Ouadi, M.; Apfelbacher, A.; Binder, S.; Hornung, A. The conversion of anaerobic digestion waste into biofuels via a novel Thermo-Catalytic Reforming process. Waste management 2016, 47, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, C. Some rules of thumb of the hydrogen economy. online blog post. June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jensterle, M.; Narita, J.; Piria, R.; Samadi, S.; Prantner, M.; Crone, K.; Siegemund, S.; Kan, S.; Matsumoto, T.; Shibata, Y.; et al. The role of clean hydrogen in the future energy systems of Japan and Germany: an analysis of existing mid-century scenarios and an investigation of hydrogen supply chains. Technical report, Wuppertal Institut, dena, IEE Japan, adelphi. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Thrän, D.; Hennig, C.; Rensberg, N.; Denysenko, V.; Eppler, U. IEA bioenergy task 40: country report Germany 2014, DBFZ, 2015.

| Colour scheme and classification (Hydrogen) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Source | Method | Colour |

| Black coal | Gasification | Black |

| Lignite (Brown coal) | Gasification | Brown |

| Natural Gas | Natural gas reforming | Grey |

| Oil | Partial oxidation | Grey |

| Byproduct | Naphtha reformation | Grey |

| Byproduct | Chlor-alkali electrolysis | Grey |

| Natural Gas + CCS | Natural gas reforming | Blue |

| Methane | Pyrolysis | Turquoise |

| Nuclear Energy | Water electrolysis | Pink |

| Mixed Grid Electricity | Water electrolysis | Yellow |

| Renewable Energy | Water electrolysis | Green |

| Feedstock composition | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultimate analysis | Unit | MSW(BW) | SS |

| C | wt% | 43.1 | 23.3 |

| H | wt% | 6.1 | 4.3 |

| N | wt% | 1.0 | 3.6 |

| S | wt% | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| O | wt% | 31.4 | 19.7 |

| Proximate analysis | |||

| HO | wt% | 10.0 | 9.7 |

| Ash | wt% | 18.1 | 46.5 |

| HHV | MJkg | 18.3 | 10.0 |

| Moisture ash free basis. | |||

| Calculated by difference. | |||

| Dry basis. | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).