Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

(1) Background: The emergence of H5N1 Influenza A viruses clade 2.3.3.4b since 2020, have caused the mortality of thousands of birds/mammals worldwide, through evolu-tionary changes have been associated with acquired mutations and posttranslational modifications. (2) Methods: This study aimed to compare the mutational profile of H5N1 avian Influenza virus isolated from a Peruvian natural reserve, with recent data from other related international studies made in human and different species of domestic and wild birds and mammals. Briefly, the near complete protein sequences of Influenza virus coming from a Calidris alba were analyzed in a multisegmented level, altogether with 55 samples collected between 2022-2024 in different countries. Moreover, the glycosylation patterns were also predicted in silico. (3) Results: A total of 603 amino acid changes were found among H5N1 viruses analyzed, underscoring the detection of critical mutations HA:143T, HA:156A, HA:208K, NA: 71S, NP:52H, PA:336M, PA:36T, PA:85A/N, PB1-F2:66S, PB2:199S, PB2:292V, PB2:559T, as well as PA:86I, PA:432I, PA:558L, HA:492D, NA:70D, NS1-83P, PB1:515A, PA-X:57Q, PB1-F2:22E, NS1-21Q, NEP:67G, among others, considered of importance under One Health perspective. Similarly, changes in the N-linked glycosylation sites (NLGs) predicted in both HA and NA proteins were found, highlighting the loss/acquisition or changes in some NLGs sites such as 209NNTN, 100 NPTT, 302NSSM (HA) and 70NNTN, 68NISS, 50NGSV (NA). (4) Conclu-sions: This study provides our understanding about the evolution of current Influenza A viruses H5N1 HPAIV circulating globally. These findings outline the importance of sur-veillance updating mutational profiles and glycosylation patterns of these highly evolved virus.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Molecular Detection

2.3. Whole-Genome Sequencing

2.4. Data Sets

2.5. Mutational analysis and genotype identification

2.6. Prediction of Potential N-Glycosylation sites in HA and NA Influenza A H5N1 Viruses

3. Results

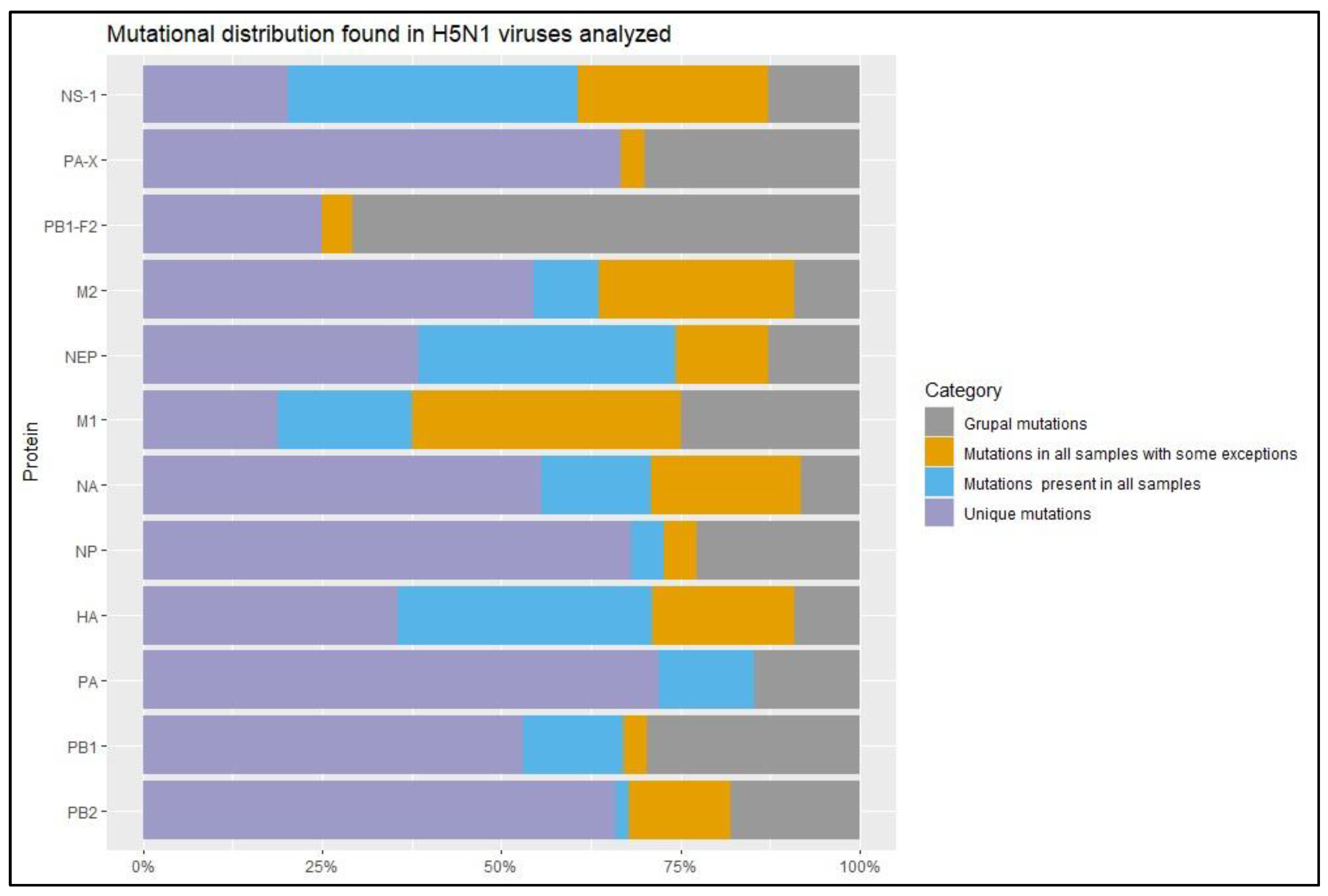

3.1. Mutational Manual Analysis

3.2. Flumut Mutational Analysis

3.3. Genotype Identification

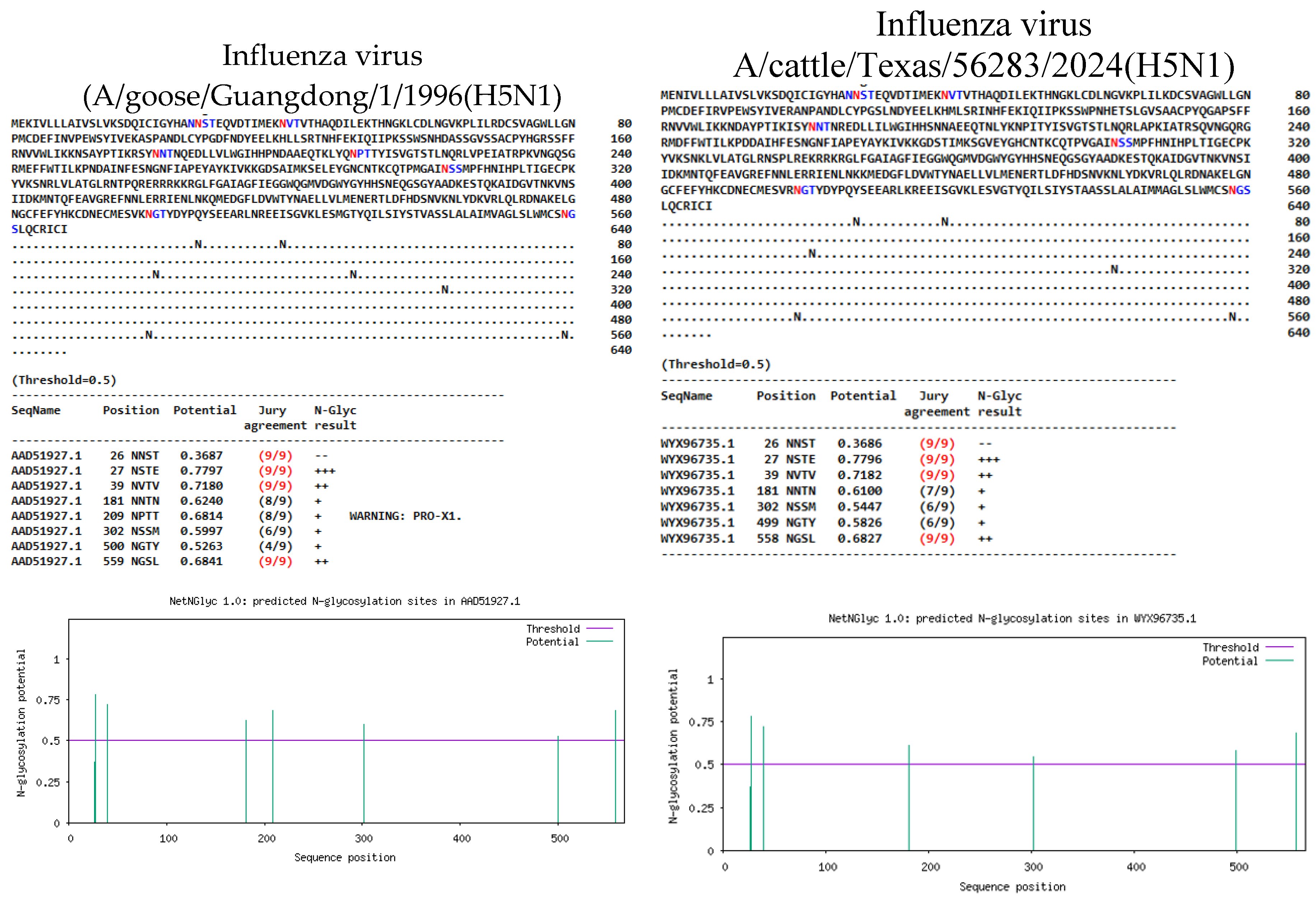

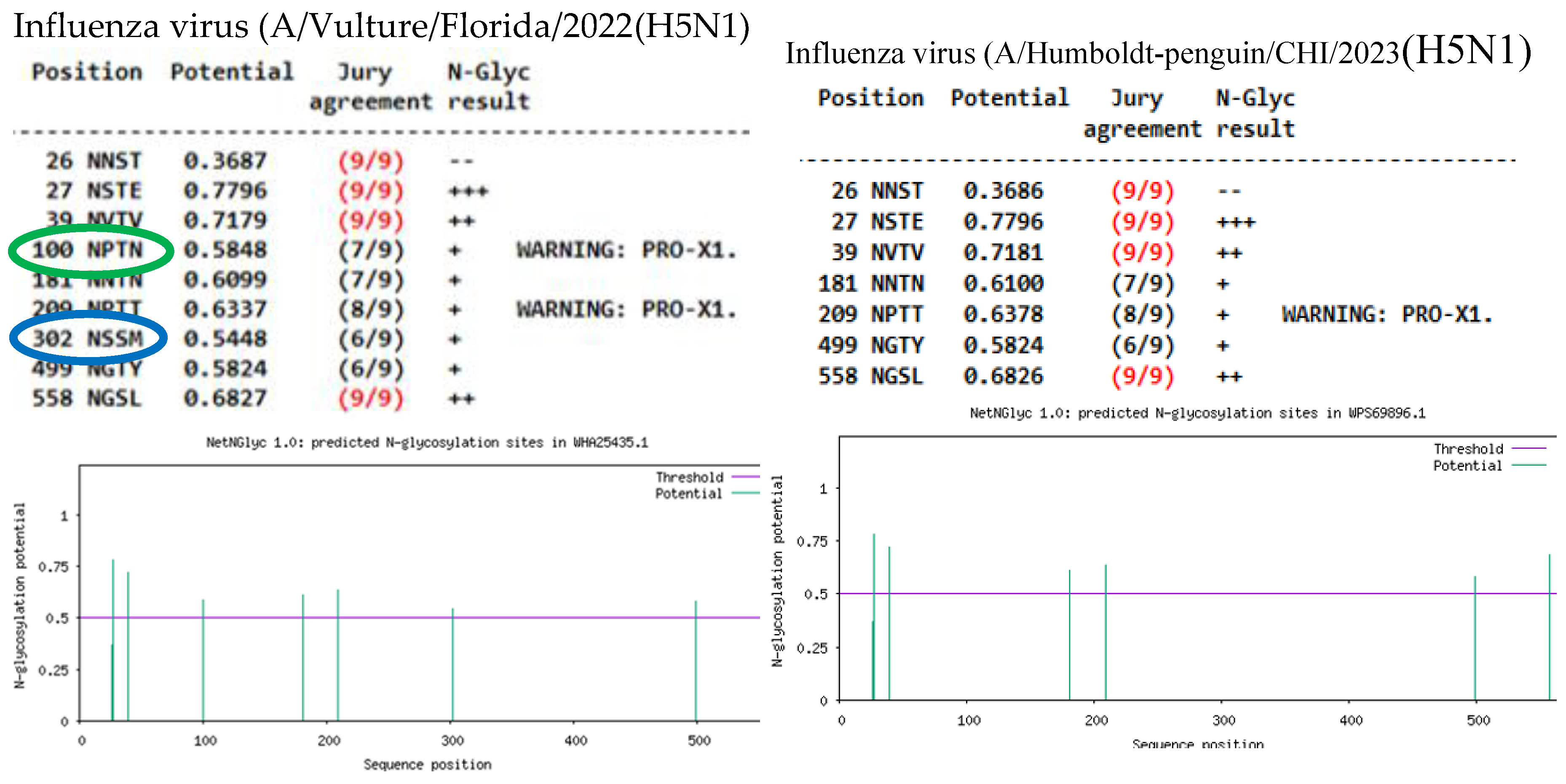

3.4. Glycosylation Patterns

3.3.1. N-linked Glycosylations in the HA of Influenza H5N1 Viruses

3.3.2. N-linked Glycosylations in the NA of Influenza H5N1 viruses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Uhart MM, Vanstreels RET, Nelson MI, Olivera V, Campagna J, Zavattieri V, et al. Epidemiological data of an influenza A/H5N1 outbreak in elephant seals in Argentina indicates mammal-to-mammal transmission. Nat Commun [Internet]. 2024 Nov 11;15(1):9516. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-53766-5.

- Duriez O, Sassi Y, Le Gall-Ladevèze C, Giraud L, Straughan R, Dauverné L, et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza affects vultures’ movements and breeding output. Current Biology. 2023 Sep;33(17):3766-3774.e3. [CrossRef]

- Caliendo V, Bellido Martin B, Fouchier RAM, Verdaat H, Engelsma M, Beerens N, et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Contributes to the Population Decline of the Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) in The Netherlands. Viruses [Internet]. 2024 Dec 27;17(1):24. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/17/1/24.

- Höfle U, Barral M, Donazar JA, Arrondo E, Antonio Sánchez-Zapata J, Cortés-Avizanda A, et al. Highly Pathogenic H5N1 Avian Influenza in Free-Living Griffon Vultures [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Jan 7]. Available from: https://digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/341041/1/HighlyPathogenic.pdf.

- Meade PS, Bandawane P, Bushfield K, Hoxie I, Azcona KR, Burgos D, et al. Detection of clade 2.3.4.4b highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus in New York City. J Virol. 2024 Jun 13;98(6). [CrossRef]

- Gamarra-Toledo V, Plaza PI, Angulo F, Gutiérrez R, García-Tello O, Saravia-Guevara P, et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) strongly impacts wild birds in Peru. Biol Conserv. 2023 Oct 1;286. [CrossRef]

- Gamarra-Toledo V, Plaza PI, Gutiérrez R, Luyo P, Hernani L, Angulo F, et al. Avian flu threatens Neotropical birds. Vol. 379, Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science; 2023. p. 246. [CrossRef]

- Bruno A, de Mora D, Olmedo M, Garcés J, Vélez A, Alfaro-Núñez A, et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Virus Outbreak in Ecuador in 2022–2024. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2024 Dec 1. [CrossRef]

- Wade D, Ashton-Butt A, Scott G, Reid SM, Coward V, Hansen RDE, et al. High pathogenicity avian influenza: targeted active surveillance of wild birds to enable early detection of emerging disease threats. Epidemiol Infect [Internet]. 2023 Dec 11;151:e15. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0950268822001856/type/journal_article.

- Reischak D, Rivetti AV, Otaka JNP, Domingues CS, Freitas T de L, Cardoso FG, et al. First report and genetic characterization of the highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus in Cabot’s tern (Thalasseus acuflavidus), Brazil. Vet Anim Sci. 2023 Dec 1;22. [CrossRef]

- Plaza PI, Gamarra-Toledo V, Rodríguez Euguí J, Rosciano N, Lambertucci SA. Pacific and Atlantic sea lion mortality caused by highly pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) in South America. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2024 Mar;102712. [CrossRef]

- Tomás G, Marandino A, Panzera Y, Rodríguez S, Wallau GL, Dezordi FZ, et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus infections in pinnipeds and seabirds in Uruguay: Implications for bird–mammal transmission in South America. Virus Evol [Internet]. 2024 May 15;10(1). Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ve/article/doi/10.1093/ve/veae031/7645834.

- Ulloa M, Fernández A, Ariyama N, Colom-Rivero A, Rivera C, Nuñez P, et al. Mass mortality event in South American sea lions (Otaria flavescens) correlated to highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 outbreak in Chile. Veterinary Quarterly. 2023;43(1):1–10. [CrossRef]

- Oguzie JU, Marushchak L V., Shittu I, Lednicky JA, Miller AL, Hao H, et al. Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus among Dairy Cattle, Texas, USA. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2024 Jul;30(7). Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/30/7/24-0717_article.

- Nguyen TQ, Hutter C, Markin A, Thomas M, Lantz K, Lea Killian M, et al. Emergence and interstate spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) in dairy cattle. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Baechlein C, Kleinschmidt S, Hartmann D, Kammeyer P, Wöhlke A, Warmann T, et al. Neurotropic Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus in Red Foxes, Northern Germany. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023 Dec;29(12). [CrossRef]

- Bordes L, Vreman S, Heutink R, Roose M, Venema S, Pritz-Verschuren SBE, et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Virus Infections in Wild Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes) Show Neurotropism and Adaptive Virus Mutations. Microbiol Spectr. 2023 Feb 14;11(1). [CrossRef]

- Barry KT, Tate MD. Flu on the Brain: Identification of Highly Pathogenic Influenza in the Brains of Wild Carnivores in The Netherlands. Vol. 12, Pathogens. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2023. [CrossRef]

- Stimmelmayr, R. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus A(H5N1) Clade 2.3.4.4b Infection in Free-Ranging Polar Bear, Alaska, USA. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024 Jul 1;30(7). [CrossRef]

- Kutkat O, Gomaa M, Moatasim Y, El Taweel A, Kamel MN, El Sayes M, et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b in wild rats in Egypt during 2023. Vol. 13, Emerging Microbes and Infections. Taylor and Francis Ltd.; 2024. [CrossRef]

- Burrough ER, Magstadt DR, Petersen B, Timmermans SJ, Gauger PC, Zhang J, et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Clade 2.3.4.4b Virus Infection in Domestic Dairy Cattle and Cats, United States, 2024. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2024 Jul;30(7). Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/30/7/24-0508_article.

- Chothe SK, Srinivas S, Misra S, Nallipogu NC, Gilbride E, LaBella L, et al. Marked neurotropism and potential adaptation of H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4.b virus in naturally infected domestic cats. Emerg Microbes Infect [Internet]. 2025 Dec 31;14(1). Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/22221751.2024.2440498.

- Ly H. Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus infection of companion animals. Virulence [Internet]. 2024 Dec 31;15(1). Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21505594.2023.2289780.

- Pulit-Penaloza JA, Brock N, Belser JA, Sun X, Pappas C, Kieran TJ, et al. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) virus of clade 2.3.4.4b isolated from a human case in Chile causes fatal disease and transmits between co-housed ferrets. Emerg Microbes Infect [Internet]. 2024 Dec 31;13(1). Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/22221751.2024.2332667.

- Guan Y, Peiris M, Kong KF, Dyrting KC, Ellis TM, Sit T, et al. H5N1 Influenza Viruses Isolated from Geese in Southeastern China: Evidence for Genetic Reassortment and Interspecies Transmission to Ducks. Virology [Internet]. 2002 Jan;292(1):16–23. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0042682201912073.

- Dholakia V, Quantrill JL, Richardson S, Pankaew N, Brown MD, Yang J, et al. Polymerase mutations underlie early adaptation of H5N1 influenza virus to dairy cattle and other mammals [Internet]. 2025. Available from: http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2025.01.06.631435.

- Lin TH, Zhu X, Wang S, Zhang D, McBride R, Yu W, et al. A single mutation in bovine influenza H5N1 hemagglutinin switches specificity to human receptors. Science (1979) [Internet]. 2024 Dec 6;386(6726):1128–34. Available from: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.adt0180.

- Marchenko VYu, Panova AS, Kolosova NP, Gudymo AS, Svyatchenko S V., Danilenko A V., et al. Characterization of H5N1 avian influenza virus isolated from bird in Russia with the E627K mutation in the PB2 protein. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2024 Nov 3;14(1):26490. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-78175-y.

- Sealy JE, Peacock TP, Sadeyen JR, Chang P, Everest HJ, Bhat S, et al. Adsorptive mutation and N-linked glycosylation modulate influenza virus antigenicity and fitness. Emerg Microbes Infect [Internet]. 2020 Jan 14;9(1):2622–31. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/22221751.2020.1850180.

- Sun Y, Zhu Y, Zhang P, Sheng S, Guan Z, Cong Y. Hemagglutinin glycosylation pattern-specific effects: implications for the fitness of H9.4.2.5-branched H9N2 avian influenza viruses. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2024;13(1). [CrossRef]

- Bao D, Xue R, Zhang M, Lu C, Ma T, Ren C, et al. N-Linked Glycosylation Plays an Important Role in Budding of Neuraminidase Protein and Virulence of Influenza Viruses. J Virol. 2021 Jan 13;95(3). [CrossRef]

- Kim P, Jang YH, Kwon S Bin, Lee CM, Han G, Seong BL. Glycosylation of hemagglutinin and neuraminidase of influenza a virus as signature for ecological spillover and adaptation among influenza reservoirs. Viruses. 2018 Apr 7;10(4). [CrossRef]

- Li S, Schulman J, Itamuraj S, Palese P. Glycosylation of Neuraminidase Determines the Neurovirulence of Influenza A/WSN/33 Virus. 1993. [CrossRef]

- She YM, Farnsworth A, Li X, Cyr TD. Topological N-glycosylation and site-specific N-glycan sulfation of influenza proteins in the highly expressed H1N1 candidate vaccines. Sci Rep. 2017 Dec 1;7(1). [CrossRef]

- Fouchier RAM, Bestebroer TM, Herfst S, Van der Kemp L, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus ADME. Detection of influenza a viruses from different species by PCR amplification of conserved sequences in the matrix gene. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(11):4096–101. [CrossRef]

- WHO WHO. WHO Information for the molecular detection of Influenza viruses [Internet]. Who. 2017. p. 1–60. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/sequencing_primers/en/index.html.

- Landazabal-Castillo S, Suarez-Agüero D, Alva-Alvarez L, Mamani-Zapana E, Mayta-Huatuco E. Highly pathogenic avian influenza A virus subtype H5N1 (clade 2.3.4.4b) isolated from a natural protected area in Peru. Roux S, editor. Microbiol Resour Announc [Internet]. 2024 Sep 10;13(9). Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/mra.00417-24.

- Cruz CD, Icochea ME, Espejo V, Troncos G, Castro-Sanguinetti GR, Schilling MA, et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) from Wild Birds, Poultry, and Mammals, Peru. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2023 Dec;29(12):2572–6. Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/29/12/23-0505_article.

- Hu X, Saxena A, Magstadt DR, Gauger PC, Burrough ER, Zhang J, et al. Genomic characterization of highly pathogenic avian influenza A H5N1 virus newly emerged in dairy cattle. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2024;13(1). [CrossRef]

- Marandino A, Tomás G, Panzera Y, Leizagoyen C, Pérez R, Bassetti L, et al. Spreading of the High-Pathogenicity Avian Influenza (H5N1) Virus of Clade 2.3.4.4b into Uruguay. Viruses [Internet]. 2023 Sep 11;15(9):1906. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/15/9/1906.

- Uyeki TM, Milton S, Abdul Hamid C, Reinoso Webb C, Presley SM, Shetty V, et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Infection in a Dairy Farm Worker. New England Journal of Medicine [Internet]. 2024 May 3; Available from: http://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMc2405371.

- Youk S, Torchetti MK, Lantz K, Lenoch JB, Killian ML, Leyson C, et al. H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza clade 2.3.4.4b in wild and domestic birds: Introductions into the United States and reassortments, December 2021–April 2022. Virology. 2023 Oct 1;587. [CrossRef]

- Pardo-Roa C, Nelson MI, Ariyama N, Aguayo C, Munoz G, Navarro C, et al. Cross-species transmission and PB2 mammalian adaptations of highly pathogenic avian influenza A/H5N1 viruses in Chile 2 3. 2023. [CrossRef]

- de Araújo AC, Silva LMN, Cho AY, Repenning M, Amgarten D, de Moraes AP, et al. Incursion of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Clade 2.3.4.4b Virus, Brazil, 2023. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024 Mar;30(3). [CrossRef]

- Rivetti AV, Reischak D, de Oliveira CHS, Otaka JNP, Domingues CS, Freitas T de L, et al. Phylodynamics of avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses from outbreaks in Brazil. Virus Res. 2024 Sep 1;347. [CrossRef]

- Campagna C, Uhart M, Falabella V, Campagna J, Zavattieri V, Vanstreels RET, et al. Catastrophic mortality of southern elephant seals caused by H5N1 avian influenza. Mar Mamm Sci [Internet]. 2024 Jan 25;40(1):322–5. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/mms.13101.

- Rimondi A, Vanstreels RET, Olivera V, Donini A, Lauriente MM, Uhart MM. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Viruses from Multispecies Outbreak, Argentina, August 2023. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024 Apr;30(4). [CrossRef]

- Uhart M, Vanstreels RET, Nelson MI, Olivera V, Campagna J, Zavattieri V, et al. Massive outbreak of Influenza A H5N1 in elephant seals at Península Valdés, Argentina: increased 1 evidence for mammal-to-mammal transmission 2 3. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Madeira F, Madhusoodanan N, Lee J, Eusebi A, Niewielska A, Tivey ARN, et al. The EMBL-EBI Job Dispatcher sequence analysis tools framework in 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024 Jul 5;52(W1):W521–5. [CrossRef]

- GNU Affero. FluMut [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jan 20]. Available from: https://github.com/izsvenezie-virology/FluMut.

- Youk S, Torchetti MK, Lantz K, Lenoch JB, Killian ML, Leyson C, et al. H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza clade 2.3.4.4b in wild and domestic birds: Introductions into the United States and reassortments, December 2021–April 2022. Virology. 2023 Oct 1;587. [CrossRef]

- Gupta R, Brunak S. Prediction of glycosylation across the human proteome and the correlation to protein function. 2002.

- Boeijen M. Glycosylation of the influenza A virus Hemagglutinin protein [Internet]. 2013. Available from: http://biology.kenyon.edu/BMB/Chime2/2005/Cer.

- Lambertucci SA, Santangeli A, Plaza PI. The threat of avian influenza H5N1 looms over global biodiversity. Nature Reviews Biodiversity [Internet]. 2025 Jan 15;1(1):7–9. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s44358-024-00008-7.

- Ahamad MI, Yao Z, Ren L, Zhang C, Li T, Lu H, et al. Impact of heavy metals on aquatic life and human health: a case study of River Ravi Pakistan. Front Mar Sci. 2024;11. [CrossRef]

- Verma N, Rachamalla M, Kumar PS, Dua K. Assessment and impact of metal toxicity on wildlife and human health. In: Metals in Water. Elsevier; 2023. p. 93–110. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez J, Boklund A, Dippel S, Dórea F, Figuerola J, Herskin MS, et al. Preparedness, prevention and control related to zoonotic avian influenza. EFSA Journal [Internet]. 2025 Jan;23(1). Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.2903/j.efsa.2025.9191.

- Alvarado-Facundo E, Vassell R, Schmeisser F, Weir JP, Weiss CD, Wang W. Glycosylation of Residue 141 of Subtype H7 Influenza A Hemagglutinin (HA) Affects HA-Pseudovirus Infectivity and Sensitivity to Site A Neutralizing Antibodies. Krammer F, editor. PLoS One [Internet]. 2016 Feb 10;11(2):e0149149. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0149149.

- Kuiken T, Vanstreels R, Banyard A, Begeman L, Breed A, Dewar M, et al. Emergence, spread, and impact of high pathogenicity avian influenza H5 in wild birds and mammals of South America and Antarctica, October 2022 to March 2024 [Internet]. 2025. Available from: https://ecoevorxiv.org/repository/view/8459/.

- Suttie A, Deng YM, Greenhill AR, Dussart P, Horwood PF, Karlsson EA. Inventory of molecular markers affecting biological characteristics of avian influenza A viruses. Virus Genes [Internet]. 2019 Dec 19;55(6):739–68. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11262-019-01700-z.

- Samson M, Abed Y, Desrochers FM, Hamilton S, Luttick A, Tucker SP, et al. Characterization of Drug-Resistant Influenza Virus A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) Variants Selected In Vitro with Laninamivir. Antimicrob Agents Chemother [Internet]. 2014 Sep;58(9):5220–8. Available from: https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/AAC.03313-14.

- Zhang T, Ye Z, Yang X, Qin Y, Hu Y, Tong X, et al. NEDDylation of PB2 Reduces Its Stability and Blocks the Replication of Influenza A Virus. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2017 Mar 2;7(1):43691. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/srep43691.

- Yamayoshi S, Kiso M, Yasuhara A, Ito M, Shu Y, Kawaoka Y. Enhanced replication of highly pathogenic influenza A(H7N9) virus in humans. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018 Apr 1;24(4):746–50. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Xu G, Wang C, Jiang M, Gao W, Wang M, et al. Enhanced pathogenicity and neurotropism of mouse-adapted H10N7 influenza virus are mediated by novel PB2 and NA mutations. Journal of General Virology [Internet]. 2017 Jun 1;98(6):1185–95. Available from: https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/jgv/10.1099/jgv.0.000770.

- Schulze IT. Effects of Glycosylation on the Properties and Functions of Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin. J Infect Dis [Internet]. 1997 Aug;176(s1):S24–8. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article-lookup/doi/10.1086/514170.

- Guo X, Zhou Y, Yan H, An Q, Liang C, Liu L, et al. Molecular Markers and Mechanisms of Influenza A Virus Cross-Species Transmission and New Host Adaptation. Vol. 16, Viruses. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI); 2024. [CrossRef]

- Wang CC, Chen JR, Tseng YC, Hsu CH, Hung YF, Chen SW, et al. Glycans on influenza hemagglutinin affect receptor binding and immune response [Internet]. 2009. Available from: www.pymol.org.

- Shakin-Eshleman SH, Spitalnik SL, Kasturi L. The Amino Acid at the X Position of an Asn-X-Ser Sequon Is an Important Determinant of N-Linked Core-glycosylation Efficiency*. Vol. 271, THE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY. 1996. [CrossRef]

- Taguchi Y, Yamasaki T, Ishikawa M, Kawasaki Y, Yukimura R, Mitani M, et al. Structural basis for the strict exclusion of proline from the N-glycosylation sequon. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Liu D, Wang Y, Su W, Liu G, Dong W. The Importance of Glycans of Viral and Host Proteins in Enveloped Virus Infection. Vol. 12, Frontiers in Immunology. Frontiers Media S.A.; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kim P, Jang Y, Kwon S, Lee C, Han G, Seong B. Glycosylation of Hemagglutinin and Neuraminidase of Influenza A Virus as Signature for Ecological Spillover and Adaptation among Influenza Reservoirs. Viruses [Internet]. 2018 Apr 7;10(4):183. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/10/4/183.

- She YM, Farnsworth A, Li X, Cyr TD. Topological N-glycosylation and site-specific N-glycan sulfation of influenza proteins in the highly expressed H1N1 candidate vaccines. Sci Rep. 2017 Dec 1;7(1). [CrossRef]

| Mutation | Source |

|---|---|

| HA:9V HA:10T HA:87T HA:99S HA:99D HA:102T HA:104G HA:147M HA:152S HA:201R HA:225M HA:226T HA:248L,259C, HA:277Y,285E, HA:316E,324T, HA:336R,493D HA:304N HA:310V HA:336N HA:473K HA:520R HA:520N HA:531L |

South America (Andean-guayata/ARG) North America(harbor-seal/ME), continent outside (duck/BD) North America (vulture/FL) South America (duck/UGY) Continent outside (turkey/GER, duck/BD) North America(vulture/FL), continent outside (chicken/JPN) North America (A/CA,emu/CA), South America (Procellaria/BR) North America (A/CA) North America (harbor-seal/ME), continent outside (turkey/GER) South America(Calidris-alba/LIM) South America (Numida/BR) North America (harbor-seal/ME) South America (Numida/BR) South America (Numida/BR) South America (Numida/BR) South America (Numida/BR) South America (Sterna/BR, Humboldt-penguin/CHI) South America (panthera-leo) North America (A/CA, emu/CA) Continent outside (turkey/GER) North America (goat/MI) Continent outside (turkey/GER) South America (Fregata/BR) |

| NA:19V NA:20A NA:23V NA:44N NA:45H NA:48T NA:53V NA:62I NA:67I NA:74L NA:74C NA:75I NA:81D NA:82P NA:84A NA:90P NA:221S NA:216V NA:217R NA:223T NA:234I NA:237F NA:241I NA:254R NA:257R NA:284N NA:286S NA:288V NA:308R NA:308K NA:329S NA:340Y NA:340F NA:364N N:374V N:399L NA:432R NA:436V NA:442I NA:460S |

South America (Numida/BR) North America (goat/MI) North America(A/LOU/WT) North America(A/LOU/WT) North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (Eagle/JPN) North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (A/LOU/WT) Continent outside (turkey/GER) North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (A/LOU/WT) Continent outside (turkey/GER) North America (A/LOU/WT) South America (Belcher-gull/PER) South America (Numida/BR) North America (peregrine-falcon/NY) North America (A/LOU/WT, Northern-pintail) North America (peregrine-falcon/NY) North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (house-mouse) North America (A/LOU/WT) South America (black-necked-swam/UGY), continent outside (chicken/JPN) North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (A/LOU/WT) Continent outside (duck/BD) Continent outside (turkey/GER) North America (A/LOU/WT) South America (duck/UGY) Continent outside (duck/BD) South America (Belcher-gull/PER) Continent outside (duck/BD) North America (polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (pintail/EGY) North America (A/WT) North America (polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (Eagle/JPN) South America (Calidris-alba/LIM) North America (grackle/TX) |

| M1:55M M1:191H M1:218A |

Continent outside (turkey/GER, pintail/EGY) South America (gallus/PER) South America (Sterna/BR) |

| M2:12R M2:19Y M2:21G M2:27A M2:28T M2:52S |

Continent outside (turkey/GER) South America (wild-duck/CO), North America (peregrine-falcon/NY) Continent outside (turkey/GER) North America (cattle/TX), continent outside (duck/BD) North America (raccoon/IA) South America (Calidris-alba/LIM) |

| PA:13V PA:42V PA:36T PA:45S PA:59K PA:59G PA:68S PA: 75Q PA: 86I PA:142E PA:100I PA:118U PA:184S,207V PA:190F PA:201I PA:201T PA:272N PA: 211I PA:213K PA:269K PA:322V PA:322L PA:323I PA:330V PA:336M PA:348L PA:351G PA: 354F PA:382G PA:388G PA:399V PA:404S PA:423T PA:425F PA:459V PA:465M PA:465T PA:486M PA:486L PA:489S PA:523L PA:538G PA:545V PA:561V PA:581I PA:613Q PA: 614D PA:614S PA:621V PA:626R PA:655F PA:664R PA:688G |

North America (house-mouse/NM), continent outside (eagle/JPN) South America (Numida/BR) North America (Cattle/TX), South America (Numida/BR) South America (Panthera-leo/PER) Continent outside (duck/BD) North America (vulture/FL) North America (A/CA, emu/CA) North America (polar-bear/ALK) South America (elephant-seal/ARG, tern/ARG) North America (alpaca/ID) North America (Racoon/IA), South America (Procellaria/BR) North America (peregrine-falcon/NY) Continent outside (duck/BD) South America (fregata/BR) North America (A/LOU/WT), continent outside (duck/BD) North America (polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (eagle/JPN) North America (vulture/FL) North America (A/LOU) North America (Northern-pintail) North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (Eagle/JPN) North America (A/LOU/WT) Continent outside (chicken/JPN) South America (Chilean-dolphin) North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (A/WT) North America (polar-bear/ALK/ALK), continent outside (Eagle/JPN) Continent outside (duck/BD) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK) North America (A/LOU) North America (cattle/TX) Continent outside (chicken/JPN) South America (black-necked-black-necked-swam/UGY) South America (Chilean-dolphin) South America (Procellaria/BR) North America (harbor-seal/ME) North America (A/CA) North America (Northern-pintail) North America (A/LOU) South America (Procellaria,Sterna/BR) North America (A/LOU) North America (A/LOU/WT), continent outside (Eagle/JPN) Continent outside (chicken/JPN) Continent outside (duck/BD) South America (Procellaria/BR) North America (polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (Eagle/JPN) North America (goat/MI) Continent outside (turkey/GER) North America (A/LOU) North America (A/CA) Continent outside (duck/BD) Continent outside (turkey/GER) |

| PA-X: 20T PA-X:36D PA-X:36T PA-X:42V,52D PA-X:59K PA-X: 62T PA-X:68S PA-X:70V PA-X:75Q PA-X: 86I PA-X:118V PA-X:122I PA-X:142E PA-X:160E PA-X:184N PA-X:190F PA-X: 195K PA-X:207L PA-X:211Y PA-X:250P |

South America (elephant-seal/ARG, tern/ARG) South America (Numida/BR) North America (cattle-TX) South America (Numida/BR) North America (vulture/FL), continent outside (duck/BD) South America (Sterna/BR) North America (A/CA, emu/CA) North America (harbor/seal/ME) North America (polar-bear/ALK) South America (elephant-seal/ARG, tern/ARG) North America (peregrine-falcon/NY) South America (turkey, duck/UY) North America (alpaca/ID) North America (polar-bear/ALK) Continent outside (duck/BD) South America (Fregata/BR) North America (A/LOU/WT) South America (wild-duck/CO), North America (peregrine-falcon/NY) North America (A/LOU) North America (A/LOU/WT, peregrine-falcon/NY), South America (wild-duck/CO) |

| PB2:9N PB2:79G PB2:152V PB2:190R PB2:191G PB2:199T PB2:251K PB2:255A PB2:274V PB2:292V,339R PB2:346A PB2:353R PB2:444G PB2:453S PB2:451V PB2:452V PB2:472D PB2:532L PB2:539V PB2:560M PB2:575V PB2:596A PB2:639S PB2:660R PB2:663R PB2:666I PB2:667I PB2:670R PB2:677K PB2:679S PB2:680G PB2:683A PB2:684S,697M PB2:711S PB2:715S |

North America (polar-bear/ALK), South America (Pelecanus/PER) North America (harbor-seal/ME) South American (elephant-seal/ARG) South America (Panthera-leo/PER) Continent outside (chicken/JPN) South America (black-necked-swam/UGY) North America (goat/MI) North America (bovine/TX) North America (goat/MI) Continent outside (turkey/GER) North America (goat/MI) North America (goat/MI) South America (Fregata/BR) North America (vulture/FL) Continent outside (duck/BD, pintail/EGY)) South America (wild-duck/CO) South America (wild-duck/CO), North America (peregrine-falcon/NY) North America (polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (Eagle/JPN) North America (raccoon/IA), South America (wild-duck/CO) Continent outside (turkey/GER) Continent outside (turkey/GER) North America (red-fox) North America (Northern-pintail) South America (duck,turkey/UGY) North America (goat/MI) North America (polar-bear/ALK), continent outside(Eagle/JPN) North America (goat/MI) North America (A/CA, emu/CA) North America (A/MO) South America (Calidris-alba/LIM) North America (polar-bear/ALK), continent outside(Eagle/JPN) Continent outside (turkey/GER) Continent outside(duck/BD) North America (peregrine/falcon/NY) North America (harbor-seal/ME) |

| PB1:11R PB1:14V PB1:40I PB1:51E PB1:53E PB1:121N PB1:147V PB1: 171A PB1:176T PB1:211K PB1:291A PB1: 321I PB1:339V PB1: 348V PB1:371D PB1: 372I PB1:383G,455D PB1:384P PB1:384T PB1:384A PB1:390G PB1:394S PB1:431H PB1:512L PB1:533S PB1:576M PB1:584H PB1:621K PB1:657H PB1:660I PB1:719I PB1:738G PB1:739D |

South America (Sterna/BR) South America (Sterna, Procellaria/BR) South America (Chilean-dolphin) South America (necked/UGY, Numida/BR) South America (Sterna/BR) South America (black-necked-swam/UGY) North America (Northern-pintail) North America (A/CO) North American (harbor-seal/ME) North American (goat/MI, Northern-pintail) North American (polar-bear/ALK) North America (peregrine-falcon/NY), South America (wild-duck/CO) South America (Numida/BR) South America (duck,turkey/UGY) South America (Numida/BR) North American (harbor-seal/ME) Continent outside(duck/BD) North American (house-mouse/NM) North American (cattle/TX) North American (turkey/GER) North American (A/WT) South America (Fregata, Procellaria/BR) North America (vulture/FL) Continent outside (turkey/GER) North America (polar-bear/ALK) Continent outside(duck/BD) North America (goose/ALK) South America (elephant-seal/ARG, tern/ARG) South America (Sterna/BR) North America (harbor-seal/ME) South America (Humboldt-penguin, cormorant/CHI) North America (harbor-seal/ME), South America (Procellaria/BR) South America (Procellaria,Sterna/BR) |

| NSI:36I NS1:66D NS1: 67G NS1:67Q NS1:75G NS1:76A NS1:77R NS1:81V NS1:88H NS1:129T NS1:136M NS1:193Q NSI:201Y NSI:202T, 210R, NS1:217T NSI:213L NSI:219E NS1:226T |

North America (Goat/MI) South America (royal-tern/ARG) North America (A/CA, emu/CA) North America(harbor-seal/ME) North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (House-mouse) Continent outside (duck/BD) South America (Belcher-gull) Continent outside (duck/BD,turkey/GER,chicken/JPN) North America (Goat/MI) North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (Goat/MI) Continent outside (duck/BD) Continent outside (duck/BD) South America (Calidris-alba/LIM North America (Northern-pintail) South America (elephant-seal/ARG,tern/ARG, Chilean-dolphin) |

| NEP:27G NEP:36V NEP:52V NEP: 56Y NEP:60S NEP:61K NEP:63E NEP: 64T,76M, NEP:77K,85Q ,81G, NEP:82E NEP:89T NEP: 89V |

South America (Numida/BR), North America (Northern-pintail) North America (A/ LOU/WT) Outside continent (duck/BD) South America (Calidris/alba/LIM) North America (Cattle/TX) North America (grackle/TX) North America (A/LOU/WT) Continent outside (duck/BD) Continent outside (duck/BD) North America(peregrine-falcon/NY, vulture/FL), South (wild-duck/CO) North America (A/MO) South America (Panthera-leo/PER) |

| PB1-F2:11R PB1-F2:11L PB1-F2:29R PB1-F2:35L PB1-F2:39T PB1-F2:41L PB1-F2:57Y PB1-F2:69L PB1-F2:73E PB1-F2:78R PB1-F2:79Q PB1-F2:90I |

North America (peregrine-falcon), South America (wild-duck/CO) Continent outside (turkey/GER) Continent outside (duck/BD, turkey/GER, chicken/JPN) Continent outside (duck/BD) North America (A/LOU) North America (vulture/FL) Continent outside (duck/BD) North America (vulture/FL) North America (harbor-seal/ME) South America (royal-tern/ARG) North America (vulture/FL), outside continent (duck/BD) South America (black-necked-swam/UGY) |

| NP:41V NP:48R NP:63T NP:119T NP:119V NP:190A NP:221K NP:230L NP:234S NP:253V NP:318L NP:323S NP:363I NP:411A NP:425V |

South America (Procellaria/BR) South America (Panthera-leo/PER) North America (A/CO) South America (Chilean-dolphin, elephant-seal/ARG, tern/ARG) North America (A/CA, emu/CA) South America (Calidris-alba/PER) South America (Numida/BR) South America (mammals/birds) Continent outside (turkeyGER, pintail/EGY) North America (peregrine-falcon/NY) North America(A/LOU) South America (Numida/BR, black-necked-swam/UGY) South America (gallus/PER) North America (A/CO) South America (Panthera-leo/PER) |

| Mutation | Source |

|---|---|

| HA:11I HA:52A HA:211I HA:242I HA:492D HA:504Y HA:527I |

North America(A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (eagle/JPN) North America(A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (eagle/JPN) North America (mammals/birds) South America(Sterna,Numida,Fregata,Procellaria,thalasseus/BR) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (eagle/JPN) South America(Sterna,Fregata,Procellaria,thalasseus/BR), continent outside (duck/BD) North America(A/LOU/WT,polar-bear/ALK), continente outside (chicken/eagle/JPN, pintail/EGY, duck/BD, eagleJPN) |

| NA:6R NA:10T NA:70N NA:71S NA:321I NA:405T |

North America(polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (duck/BD, turkey/GER, eagle/JPN, pintail/EGY) North America(polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (duck/BD, turkey/GER, eagle/JPN, pintail/EGY) North America(polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (duck/BD, eagle/JPN), South America (wild-duck/CO) North America (mammals, birds) North America (mammals, birds) North America (polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (duck/BD, turkey/GER, eagle/JPN, pintail/EGY) |

| M1:82S M1:125A M1:227T M1:236K |

North America (mammals/birds) South America (Sterna/BR) North America (mammals,birds) Continent outside (chicken/JPN) |

| M2:88N | North America (mammals,birds) |

| NP:52H NP:105M NP:293K NP:377N NP:482N |

North America (mammals/birds), continent outside (Eagle/JPN) North America (mammals/birds), continent outside (turkey/GER), South America (wild-duck/CO) South America (Sterna,Procellaria,Fregata,thalaseus/BR), continent outside (turkey/GER) North America (harbor-seal/ME,vulture/FL,peregrine-falcon/NY), South America (wild-duck/CO), continent outside (chicken/JPN) North America (mammals,birds) |

| PB2:58A PB2:109I PB2:139I PB2:154F PB2:362G PB2:441N PB2:495I PB2:631L PB2:649I PB2:676A |

North America (mammals/birds) North America (mammals/birds) North America (mammals/birds) South America (Procellaria,Sterna,Thalasseus,Fregata/BR, duck,turkey,black-necked-swam/UGY) North America (mammals/birds) North America (mammals/birds) North America (mammals/birds) North America (mammals/birds) North America (mammals/birds) North America (mammals,birds), raccoon (676V) |

| PB1:16D PB1:154S PB1: 171V PB1:171A PB1:172D PB1:179I PB1:207R PB1: 215K PB1:264D PB1:375N PB1:378M PB1:399D PB1:429R PB1:430K PB1:515A PB1:548F PB1:587P PB1:614D PB1:646I PB1:694S |

North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (pintail/EGY, Eagle/JPN) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (eagleJPN) North America (birds/mammals) North America (A/LOU/WT, harbor-seal/ME, polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (chicken/eagle/JPN, pintail/EGY, duck/BD, Eagle/JPN) North America (A/CO) North America (A/LOU/WT, harbor-seal/ME,polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (eagle/chicken/JPN, turkey/GER, duck/BD, pintail/EGY) North America (birds-mammals) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (turkey/GER, eagle/JPN) South American (birds/mammals), continent outside (duck/BD) South America (birds, mammals) North America (A/LOU/WT, harbor-seal/ME, polar-bear/ALK, peregrine-falcon/NY), continent outside (chicken/eagle/JPN, pintail/EGY, duck/BD,turkey/GER), South America (wild-duck/CO) South America (birds/mammals) South America (birds/mammals) South America (birds/mammals) North America (birds/mammals) South America (Chilean-dolphin, elephant-seal/ARG, tern/ARG, pelecanus, Humboldt-penguin,cormorant,chimango/CHI) South America ((Chilean-dolphin, elephant-seal/ARG, tern/ARG) North America (birds/mammals) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (Eagle/JPN) South America (Procellaria,Numida,Fregata/BR, swam,duck,turkey/UGY) North America (A/LOU/WT, harbor-seal/ME, polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (eagle/chickenJPN, turkey/GER, duck/BD) |

| PB1-F2:4G PB1-F2:7I PB1-F2:7T PB1-F2:7M PB1-F2:8Q PB1-F2:17S PB1-F2:18T PB1-F2:20R PB1-F2:21R PB1-F2:22E PB1-F2:30L PB1-F2:31E PB1:36T PB1-F2:40G PB1-F2:42Y PB1-F2:44R PB1-F2:46T PB1-F2:47S PB1-F2:48R PB1-F2:49A PB1-F2:50G PB1-F2:54K PB1-F2:55I PB1-F2:56A PB1-F2:57C PB1-F2:58W PB1-F2:65R PB1-F2:66S PB1-F2:68I PB1-F2:70G PB1-F2:75L PB1-F2:82S PB1-F2:84S PB1-F2:90N |

North America (A/LOU/WT, harbor-seal/ME, polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (pintail/EGY, eagleJPN) North America/South America (birds and mammals) North America (birds and mammals), South America/continent outside (birds) South America (Sterna/BR) North America (A/LOU/WT, harbor-seal/ME, polar-bear/ALK, continent outside (Eagle/JPN) South America (birds/mammals) North America (A/LOU/WT, harbor-seal/ME, polar-bear/ALK, continent outside (eagle/chickenJPN, turkey/GER, duck/BD, pintail/EGY) North America (A/LOU/WT, harbor-seal/ME, polar-bear/ALK, continent outside (Eagle/JPN) North America (A/LOU/WT, harbor-seal/ME, polar-bear/ALK, continent outside (chicken/JPN, turkey/GER, duck/BD, pintail/EGY) North America (A/LOU/WT, harbor-seal/ME, polar-bear/ALK, continent outside (Eagle/JPN), South America (Numida/BR,black-necked-swam/UGY) South America (birds/mammals), North America (vulture/FL, peregrine-falcon/NY) North America/South America (birds and mammals) North America (A/LOU/WT, harbor-seal/ME), polar-bear/ALK, continent outside (Eagle/JPN) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (Eagle/JPN, pintail/EGY), South America (Sterna/BR) North America (A/LOU/WT, harbor-seal/ME, polar-bear/ALK, continent outside (chicken/Eagle/JPN, turkey/GER, duck/BD, pintail/EGY) South America (birds/mammals), North America (goose/ALK,vulture/FL, peregrine/falcon), continent outside (chicken/Eagle/JPN, turkey/GER, duck/BD, pintail/EGY) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK,harbor-seal/ME), continent outside (chicken/Eagle/JPN, turkey/GER, duck/BD, pintail/EGY) North American (mammals/birds) North America (polar-bear/ALK, harbor-seal/ME), continent outside (eagle/JPN, pintail/EGY) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK, harbor-seal/ME), continent outside (chicken/Eagle/JPN, turkey/GER, pintail/EGY) South America (birds,mammals), North America (goose/ALK,pintail) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK, harbor-seal/ME), continent outside (chicken/Eagle/JPN, turkey/GER, duck/BD, pintail/EGY) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK, harbor-seal/ME), continent outside (chicken/Eagle/JPN, turkey/GER, duck/BD, pintail/EGY) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK, harbor-seal/ME), continent outside (chicken/Eagle/JPN, turkey/GER, pintail/EGY) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK, harbor-seal/ME), continent outside (chicken/Eagle/JPN, turkey/GER, duck/BD, pintail/EGY) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK, harbor-seal/ME), continent outside (chicken/Eagle/JPN, turkey/GER, duck/BD, pintail/EGY) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK), continent outside (eagleJPN) North America (goose/ALK,pintail), South America (birds/mammals), continent outside (chicken/Eagle/JPN, duck/BD, pintail/EGY) North America (birds/mammals), continent outside (pintail/EGY) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK, harbor-seal/ME), continent outside (eagle/JPN, turkey/GER, duck/BD, pintail/EGY) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK, harbor-seal/ME), continent outside (chicken/Eagle/JPN, turkey/GER, duck/BD, pintail/EGY) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK, harbor-seal/ME), continent outside (chicken/Eagle/JPN, turkey/GER, pintail/EGY) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK, harbor-seal/ME), continent outside (chicken/Eagle/JPN, duck/BD, pintail/EGY) South America (wild-duck/CO), North America (A/LOU/WT, polar-bear/ALK, harbor-seal/ME, peregrine-falcon/NY), continent outside (chicken/JPN, turkey/GER, duck/BD, pintail/EGY) |

| NS1:7S NS1:7L NSI:21R NS1:21Q NS1:26K NSI: 53G NS1:83P NS1: 87S NS1: 88C NS1: 116C NS1: 147I NS1:189N |

North/South America/outside of continent (birds and mammals) North America (3 birds, 14 mammals) North/South America/continente outside (birds and mammals) North/South America (grackleTX, elephant-seal, A/CO, cattleTX) South America (Chilean-dolphin, elephant-seal/ARG, tern/ARG, Humboldt-penguin, chimango, cormorant/CHI) North America (vulture/FL, harbor-seal/ME), South America (birds/mammals) South America (wild-duck/CO), North America (A/LOU/WT,harbor-seal/ME,polar-bear/ALK, peregrine-falcon, vulture/FL), continent outside (pintail/EGY, eagleJPN) North America and continent outside (birds and mammals) South America birds (Procellaria,Fregata,Sterna,thalasseus/BR) North America/continent outside (birds and mammals) North America (A/LOU/WT, polar bear), continente outside (pintail/EGY, eagle/JPN) South America, birds(chimango,cormorant/CHI, Humboldt-penguin/CHI),North America (peregrine-falcon/NY) |

| NEP:7V NEP:7S NEP:31V NEP:67G |

North America (3 birds, 14 mammals), 2 continent outside North/South America/outside (birds and mammals) South America (Birds: chimango, Humboldt-penguin, cormorant) North America (3 birds, 19 mammals), continent outside (Eagle/JPN, pintail/EGY) |

| PA: 57R PA:113R PA:219I PA:237K PA:237A PA:272E PA:277P PA:432I PA:479E PA:497R PA:558L |

South America (mammals and birds) North America (mammals and birds) North America (mammals and birds) South America (tern/ARG, Calidris-alba/LIM, Chimango/Coquimbo/CHI) South America (royal-tern/ARG) North America (peregrine-falcon), South America (wild-duck/CO), continent outside (duck-BD) North America (mammals and birds North America (A/CA, emu/CA,peregrine-falcon/NY), South America (cormorant, wild-duck/CO), continent outside (pintail/EGY, turkey/GER) South America, birds/BR/UGY North America (birds/mammals), South America (Procellaria/BR) South America (elephant-seal/ARG,tern/ARG, pelecanus/PER, Procellaria/BR, turkey/duck/UY, Panthera-leo/PER,Calidris-alba/LIM), North America (goose/ALK, Northern-pintail) |

| PA-X: 57Q PA-X: 61I PA-X:85T PA-X:113R PA-X:193S PA-X:215L PA-X:245N |

South America (mammals,birds), continente outside (turkey/GER), North America (peregrine-falcon/NY, A/LOU/WT) South America (wild-duck/CO), North America (A/LOU/WT, peregrine-falcon/NY), continent outside (turkey/GER, duck/BD). South America (wild-duck/CO), Continent outside (duck/BD,turkey/GER), North America (A/LOU/WT) North America (mammals and birds) South America (wild-duck/CO), North America (A/LOU/WT, peregrine-falcon/NY, polar-bear/ALK,vulture/FL, harbor-seal/ME), continent outside (duck/BD, pintail/EGY) South America (Fregata/BR, Thalasseus/BR,Sterna/BR, Procellaria/BR, duck/UGY, turkey/UGY) South America (mammals/birds) |

| Protein | Commentary |

|---|---|

| HA | 3N,88R,100S,110S,111L,139P,142E,143T,154Q,156A,157P,171D,190I,197S,208K,228K,233S 234Q,239R,243D,256H,284G,326K,429K,499R,515K,539A |

| NA | 46P,76A,78Q,99I,100Y,258I,289M,366S,382E,418M,434N |

| M1 | 140A,144L,165I, |

| M2 | 18N |

| NP | 136L |

| PB2 | 699K,741S |

| PB1 | 177E, 478S, 490F, 535I,536N, 558T, 598P,609Y,610C |

| PB1-F2 | No PB1-F2 sequence in the reference genome |

| NS1 | 6I,18V,22F,23S,24D,25Q,27L,28C,54I,60A,73S,84V,94T,95L,112A, 114G,117I,127R,137L,140Q,146L,153E, 158G,161S, 163L,170T,180V,191T, 194V, 197T, 198L,205S,206S,211R,221K,224R,225T,366S |

| NEP (NS2) | 6V, 14M,22G, 26E,37S, 40L, 48A, 49V,68Q,83V,86R,88K,100M,111Q |

| PA | 63V,129I, 212C, 228N, 361K, 536K,544E, 585L, 586L,716R |

| PA-X | no PA-X sequence in the reference genome |

| PB2 | 355R, |

| NS1 | 44R,55E,56T,59R,63Q,70E,71E,74D,90L,111V,118R,139D,145I,166L,171D,192V,204R,207N, 209D,213P,441V,553A, 608S,245S/N,252K/R |

|---|---|

| PB1 | 59S,75D |

| PB2 | 334S,340R,463V,464M,471T,478I,590G, 616V |

| NP | 450N |

| M2 | 28I,51V,61G |

| M1 | 85S,87T,101R,200V,230R,232D |

| HA | 69K,98R,120M,131L,178I,185R,199N,201E,205N,226A,336S,341K,344R,527V,549M |

| NA | 8T,20V,44Y,81T,155Y,188I,269M,287D,340S,336S,338M,339P,340S,395E,460G |

| NEP | 63A, 64K,81E,85H,89I |

| PA-x | 252R/K |

| PB1-F2 | 11Q,12L/S |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).