Introduction

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses are members of the Alpha-influenza viruses (AIVs) that are part of the Orthomyxoviridea family (1). AIVs are classified into several subtypes according to their antigenic determinants in the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) proteins. There are 18 distinct HAs and 11 distinct NAs identified till now (2). AIVs have a segmented RNA genome and an RNA-polymerase that lacks the 3'-5' exonuclease activity, which results in an accumulation of an average mutation rate of 10−4. The variations observed in the genome, which induce aa changes, are known as (i) antigenic drift, that represent the accumulation of mutations leading to considerable changes in both HA and NA peptides, and (ii) antigenic shift, that leads to a virion with a hybrid genome composed of different segments exchanged from various strains during the co-infection of the same cell (1,3-6). On the other hand, recombination is not a process that is well studied or proven among influenza viruses, even though evidence of homologous recombination has been demonstrated on different segments in Chinese isolates (7,8).

AIVs are divided into two pathotypes that are either low (all subtypes) or high pathogenic (H5 and H7), as the latter not only target the respiratory and digestive systems, like the low pathogenic strains, but also cause systemic degenerative disease in infected avian hosts (9). This high pathogenicity was shown to be associated with the presence of specific multi-basic amino acids within the cleavage site on the HA protein targeted by subtilisin-like enzymes. The cleavage activity of these enzymes, present in various organs, is responsible for the differentiation of HA into its active form (10, 11). Migratory birds, particularly Anseriformes and Charadriiformes, are considered the natural reservoir of AIVs (12). They are known to host the low pathogenic pathotype; however, when the virus is transmitted to poultry flocks, there is a change toward the high pathogenic form (13). The change is mostly indels or single-nucleotide deletions (SNDs) in the HA RNA that are required for better adaptation to the host (14)

Globally, H5Nx strains are associated with two different lineages, the Eurasian lineage, which originated from China in 1996 (A/goose/Guangdong/1/1996) [Gs/GD], and the North American lineage that was identified later in 2014 (13,15-18). In Africa, several migratory routes that could be associated with virus transmission to the continent were identified. Moreover, three different clades of the Gs/GD lineage {2.2 (2005–2011), 2.3.2.1c (2011–2017), and 2.3.4.4b (2014–2018)} that originated from East or North-Central Asia were identified (19,20). The HPAI H5N1 2.3.4.4b is the most concerning group as it became a threat not only to the farm poultry production but also to other species, since spillovers to dairy cattle across several states in the USA and four farm workers were recently reported (20-23). This cluster is widely distributed in Asia and Europe, causing tremendous losses in poultry production, and it was introduced in December 2021 into North America, and ever since, humans, avian, and mammal species have been found affected (24-27). During the last four years, at least 35 documented cases of AIV/H5N1 virus infections in humans have been reported to WHO (24). The majority of these patients were infected with viruses belonging to the clade 2.3.4.4b (24,28,29). A total of 66 cases of HPAI A(H5N1) belonging to the clade 2.3.4.4 have been reported in infected humans in the US in 2024 following contact with infected poultry or cows (24,29).

Two distinct epizooties have affected the poultry flocks raised in Algeria; the first one, from December 2020 to May 2021, was caused by H5N8, and the second, from late September 2022 until July 2023, was caused by H5N1. They have caused up to 70% and 40% mortality in chickens and turkeys, respectively. Previously, we reported on the detection and the pathological properties of viruses that caused both epizooties (30). In this study, we are reporting on the genetic characteristics of the HA and NA genes of these strains following sequence analyses.

Materials and Methods

RNA extraction was performed using Qiagen products on organ samples collected during both epizooties as described in Ammali et al., 2024. RT-PCR was performed using the primers H5N1-ha_4Fv2 and H5N1-ha_4Rv2 to amplify the full hemagglutinin (HA-H5) gene and the primers H5N1-na_6Fv2 and H5N1-na_6Rv2 to amplify the full neuraminidase (NA-N1) gene (31). The full NA-N8 gene was amplified using H5N8-N8-F and H5N8-N8-R primers we reported earlier, Ammali et al. 2024 (30). The same thermal profile was used for amplification of all the genes with one-step reverse transcription at 50°C for 15 min and denaturation at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 sec, 50°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 2 min.

Semi-nested PCR protocols were conducted for the samples that failed to produce the full-length HA amplicon products with the external primers. One µl of the PCR products was used as a matrix for a new PCR amplification using the external H5N1-ha_4Fv2 associated with the internal H5-1162Rv: 5’-GAGTGGATTCTTTGTCTG-3’ (31,32) primers, to generate the 1155 bp HA-H5 fragment. Similarly, the external H5N1-ha_4Rv2 was associated with the internal H5-1063Fw: 5’-TTTATAGAGGGAGGATGG-3’ (31, 32) primers to generate the 716 bp HA-H5 fragment. These two fragments cover the total HA-H5 coding sequences.

A similar semi-Nested PCR strategy was performed using the external H5N1-na_6Fv2 and H5N1-na_6Rv2NA-N1 primers (31) on extracted RNAs, and then the internal N1av-648Rv: 5’-GCCATTTACACATGCACATT-ATTCAG-3’ (32) and AN1B: 5’-TTGCTTGGTCAGCA -AGTGCA-3’ (33) NA-N1 primers on the first PCR products. These Semi-nested PCR reactions generated 648 bp and 895 bp fragments, respectively, covering the total NA-N1 coding sequences.

For the NA-N8 gene, we used the H5N8-N8-F and H5N8-N8-R external primers in combination with NA8-856-R: 5’-GCATTCCACTTTACCATCA-3’ and NA8-735-F: 5’-GTAATGACTG- ACGGTCCAT-3’, respectively. These primers were designed with BLASTN (34) (RRID: SCR_001598) and BioEdit v7.2.5 (RRID: SCR_007361). These semi-nested PCR amplified 835 bp and 665 bp amplicons, respectively.

The thermal profile for the amplification applied to all semi-nested PCR reactions was identical to the one used with the external primers, but without the reverse transcription step. Samples of the resulting amplicon products were separated in a 1.2% agarose gel by electrophoresis containing safe view dye and then visualized under UV light.

PCR products and gel-separated PCR products were purified using the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up kit (MACHEREY-NAGEL) according to the protocol provided. The quality of purification was assessed by electrophoresis using a 1.2% agarose gel.

The sequencing was conducted on thirteen H5N8 samples from the first epizooty (2020-2021) and eight H5N1 from the second epizooty (2022-2023) isolated in Algeria (30).

Purified DNA samples were referred to Eurofins Genomics Europe (Ebersberg, Germany) using the LightRun service for sequencing based on the Sanger method. The DNA template and the oligonucleotide primer mixes were prepared according to the protocol applied for the LightRun service.

The sequences were treated with SnapGene (RRID:SCR_015052), the alignment was achieved using Clustal Omega version 1.2.4 and phylogenetic analyses were conducted with BLASTN (34), Phylogeny.fr (35) (RRID:SCR_010266), and MEGA 11 Software (RRID:SCR_000667) (36) using the Neighbor-Joining method (37). The evolutionary distances were computed using the Maximum Composite Likelihood method (38). Recombination hotspots were detected with Recombination Detection Program (RRID:SCR_018537) (RDP4, v.4.39) (39) and Genetic Algorithm for Recombination Detection (GARD) (

https://www.datamonkey.org/gard) (40).

Results

Sample Amplification and Sequencing

The PCR aiming the full-length genes successfully amplified the HA-H5 coding sequences in nine samples identified as H5N8 and five others identified as H5N1. Similarly, the full-length NA-N8 coding sequences were amplified in nine samples identified as H5N8, and the NA-N1 coding sequences from five samples were identified as H5N1. Following amplicon purifications, eight H5N8 and five H5N1 were positively selected for DNA sequencing.

The semi-nested PCRs applied on the samples that failed to amplify enough amplicon with the external primers, provided additional HA-H5 amplicons in six samples, NA-N8 amplicons in four additional samples, and NA-N1 amplicons in two additional samples. Therefore, four H5N8 and two H5N1 purified PCR products were selected for sequencing.

The sequencing data based on the classical Sanger method using the external primers provided the full-length sequences of two HA-H5 genes (PP422362 (H5N8) and PP422967(H5N1)), and 12 partial sequences of HA-H5 genes (five from H5N1 and eight from H5N8) (

Table 1). The full-length sequences of NA-N1 were obtained with two samples (PP422536 and PP422956), and partial sequences in three others (

Table 1). For the NA-N8 coding sequences, partial sequences were obtained in ten samples (

Table 1). Sequencing annotation and aligning of the HA and NA genes from the two subtypes were conducted separately. The details regarding the sequences are reported in

Table 1.

Molecular Characterization of the H5N8 and H5N1 Isolates

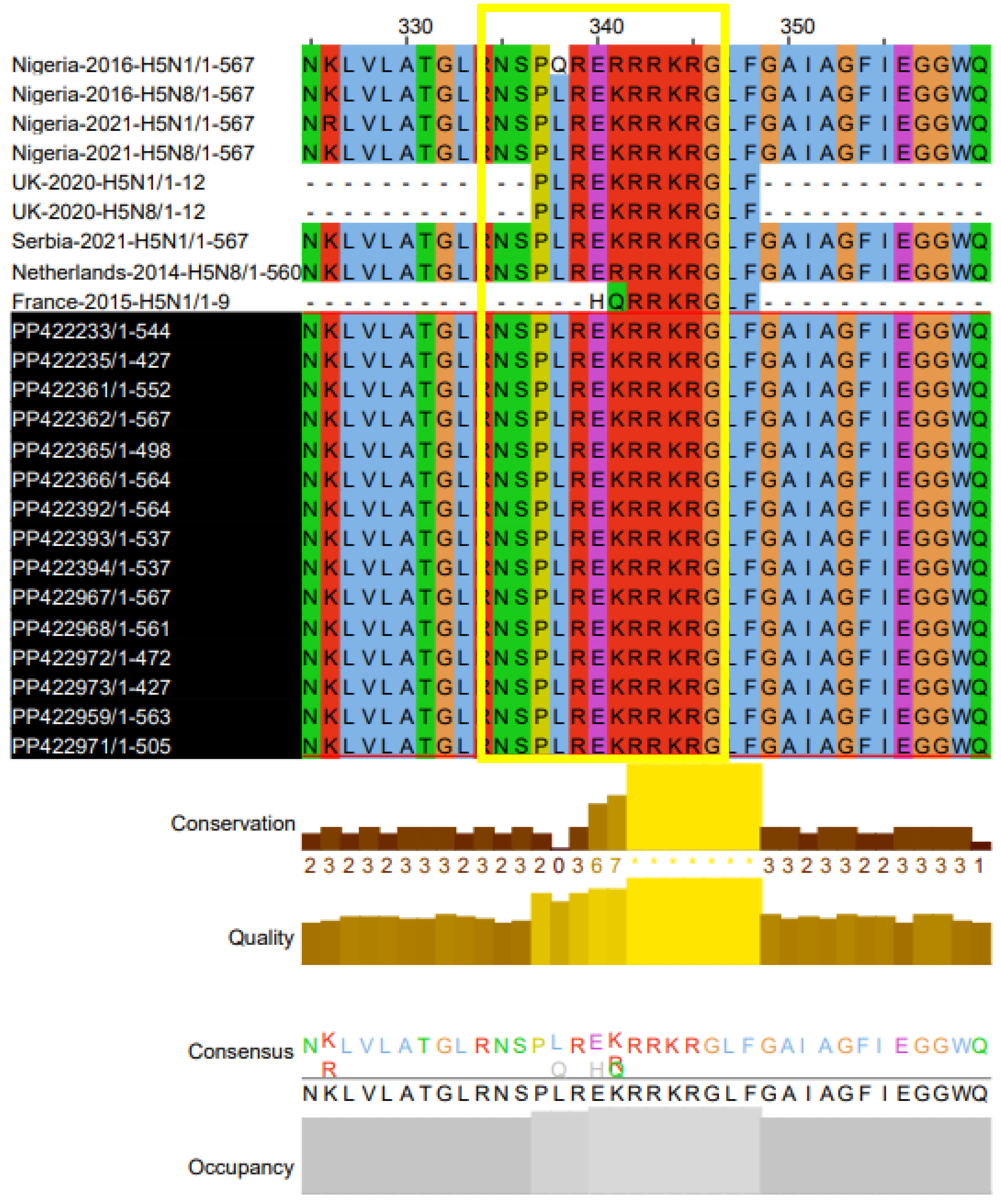

Analyses of sequencing data showed that all the sequences of all HA-H5 samples have a conserved motif 337PLREKRRKR/GLF348 corresponding to the cleavage site typical of the highly pathogenic pathotype of the strains.

Similarly, examination of NA-N8 and NA-N1 sequencing data revealed that the Oseltamivir susceptibility site on N8 (273H and 293N, N8 numbering) and N1 (275H and 295N, N1 numbering) was conserved in the sequences of our isolates (41,42).

Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogenetic analysis was performed separately for all the sequence data of the four genes compared to similar sequences available in the Genbank database, which were used for comparison.

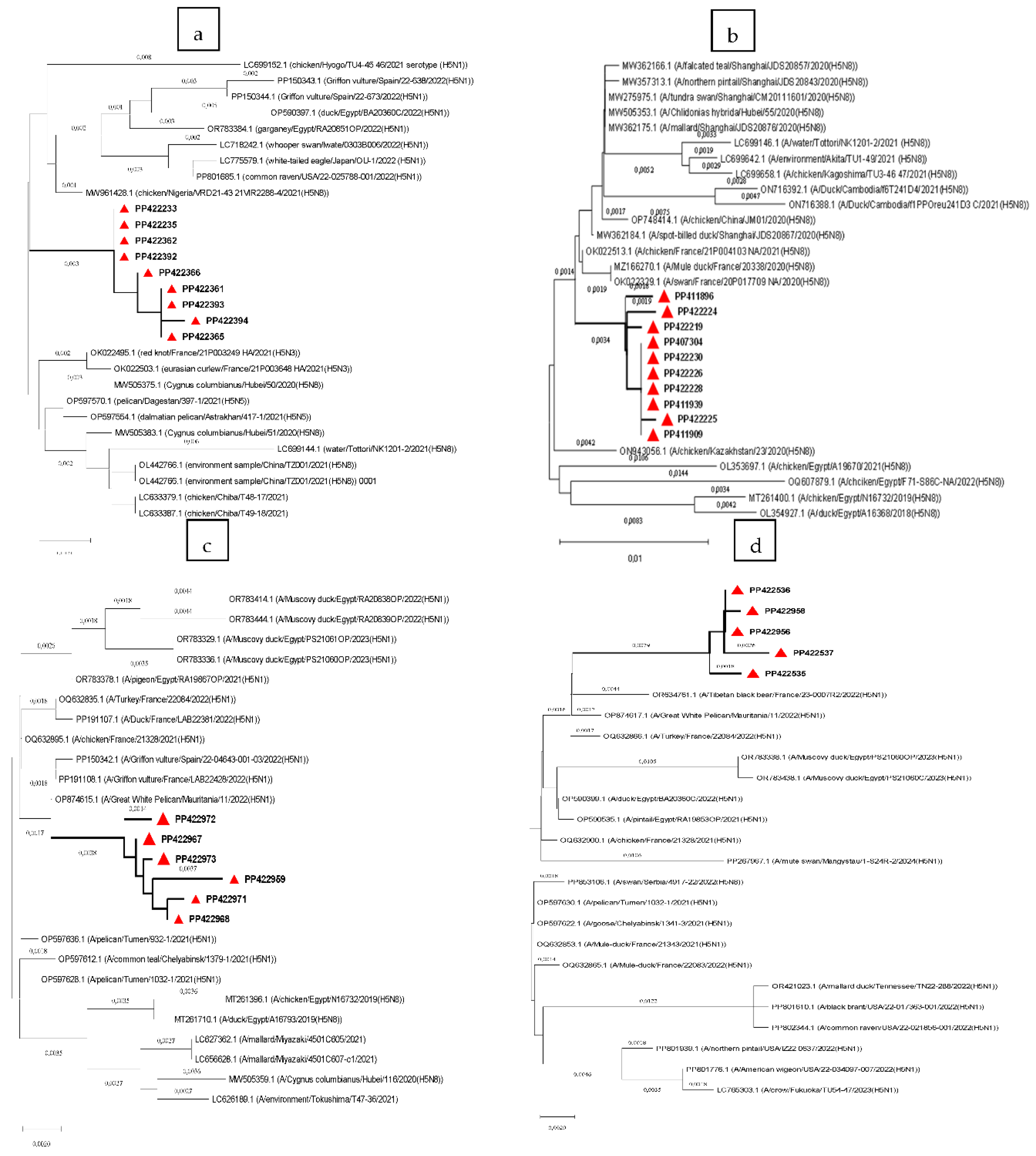

Based on this analysis, the HA-H5 genes from the 2020-2021 epizooty caused by H5N8, were closely related to the Nigerian isolate (Chicken/Nigeria/2021(H5N8)) (nucleotide homologies 99.21%) and the Chinese strain (Cygnus Columbianus/Hubei/2020 (H5N8)) (nucleotide homologies 99.20%) (

Figure 1.a). These data consolidated our earlier findings that the virus isolates causing this epizooty were indeed H5N8 subtypes. The sequences of the virus isolates also clustered with a variety of other subtypes, that were isolated mainly from wild birds, including the H5N3 isolated in France in 2021 (nucleotide homologies 98.76%-98.85%), the H5N1 isolated in Egypt, Spain, Japan and USA in 2022 (nucleotide homologies 98.68%-98.06%) and the H5N5 isolated in Dagestan and Astrakhan in 2021 (nucleotide homologies 98.94% and 98.85%, respectively) (Fig.1.a). The NA-N8 genes of this H5N8 virus closely clustered with the sequences of the French isolates (Swan/France/2020(H5N8)) and (Mule duck/France/2020(H5N8)) collected in 2020 (nucleotide homologies 99.12%) (

Figure 1.b).

Phylogenetic analysis of the sequences of both H5 and NA genes of the viruses causing the 2022-2023 epizooty confirmed that the virus was an H5N1 subtype. The HA and NA sequences of these virus isolates were found to be closer to those of an African H5N1 isolate that was collected in Mauritania in 2022 (Great_White_Pelican/Mauritania/2022 (H5N1)) with 99.25% nucleotide homologies for HA-H5 and 98.74% for NA-N1 genes (

Figure 1.c and d). Sequence similarities of these viruses were also found with those of other strains isolated in 2021 and 2023 outbreaks in Egypt, with similarities reaching 98.6% in HA-H5 and 98.34% in NA-N1 genes. The sequences were likewise related to the French strains isolated in 2021 and 2022, with nucleotide homologies in HA-H5 reaching 98.94% and up to 98.59% in NA-N1 (

Figure 1.c and d).

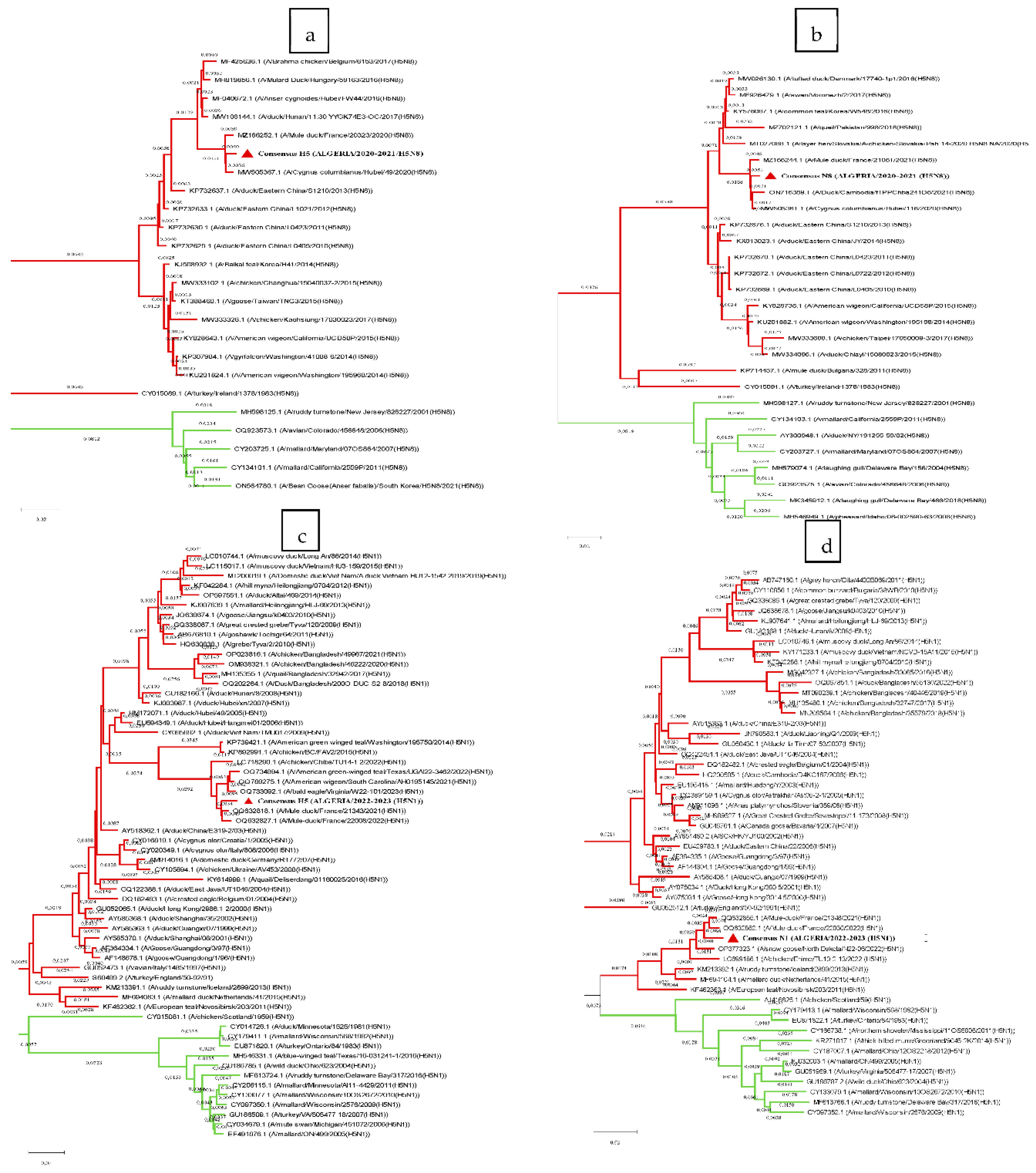

To examine to which lineage the sequences of Algerian strains are the closest, we compared their sequences to those of selected representatives of the two lineages from the Influenza Virus Resource database, and calculated the patristic distances (

Table 2). Based on the results of these calculations and the phylogenetic trees, all genes were found to be related to the Eurasian lineage (

Figure 2.a, b, c, d). However, the N1 gene shared similarities with both lineages; therefore, a Z test (α=0.05, Z=1.96) was conducted, and no significant difference was observed between the two means.

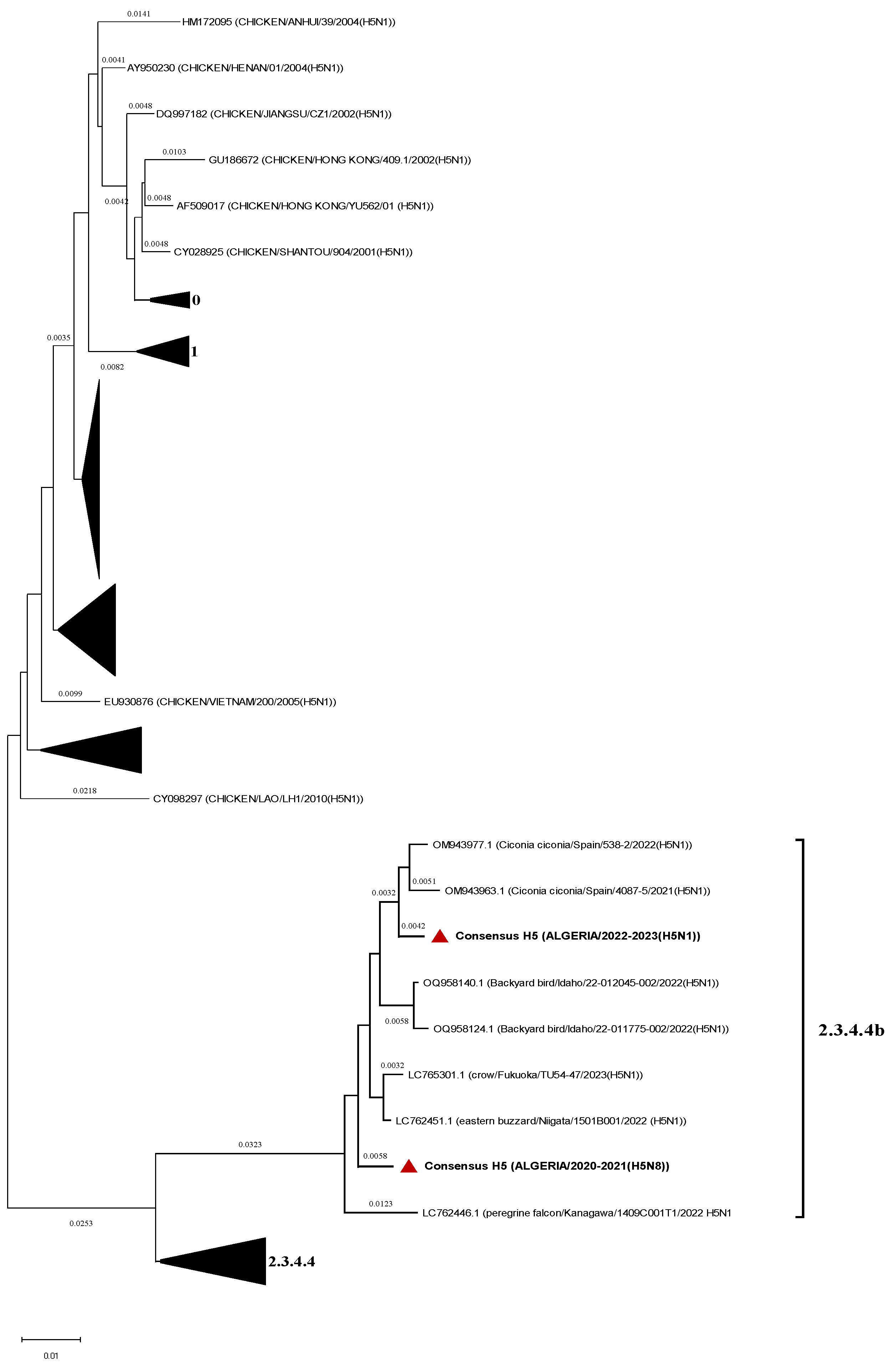

H5 consensus sequences were compared to representatives’ sequences of the Gs/GD lineage clades and both strains belong to the 2.3.4.4b (

Figure 3).

Recombination Events Detection

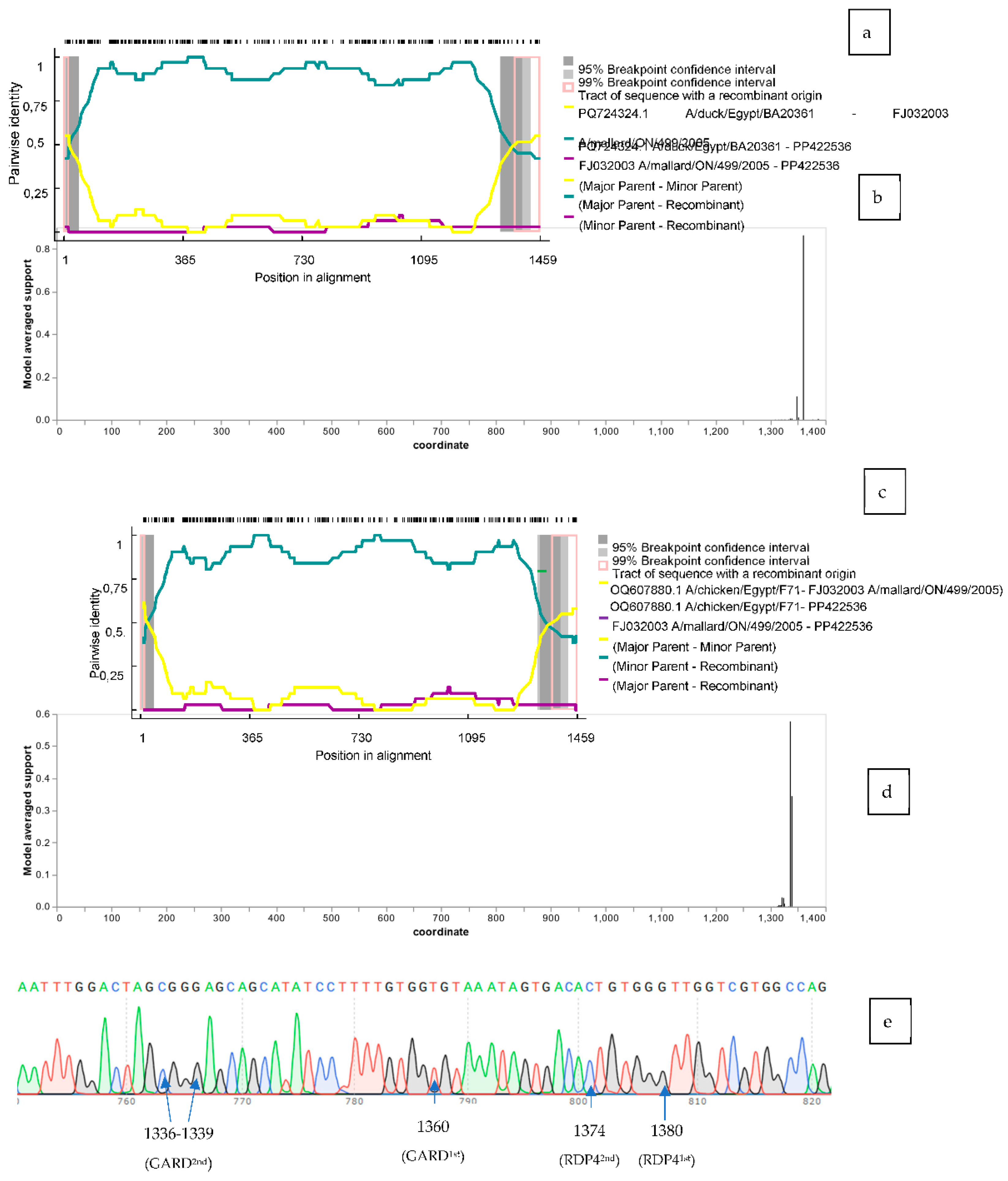

To detect the presence of a putative recombination hotspot in the mismatching region of the gene, we used the RDP 4.39 (39) to test the four N1 sequences. Several methods (RDP, GENECONV, BootScan, MaxChi, Chimaera, SiScan, PhylPro, LARD and 3Seq) were used to detect the potential hotspot points of recombination. RDP, GENECONV, MaxChi, Chimaera, BootScan and 3Seq methods revealed a recombination hotspot in three (PP422536, PP422956, PP422535) out five analyzed sequences (

Table 3). Two potential breakpoints were determined in PP422536 and PP422535, the first one was at position 15 and the second at 1380, and one breakpoint in PP422956 beginning at 1380 and ending at 1456 (according to the reference sequence PP422536 alignment) (

Figure 4.a). The analysis established PQ724324.1 (A/duck/Egypt/BA20361C/2022(H5N1)) as the major parent and FJ032003.1 (A/mallard/ON/499/2005 (H5N1)) as the minor parent. The pairwise identity ranged between 49% and 99% between the two breakpoints. Regarding the minor parent, pairwise identity was mostly lower than 10% compared to the N1 recombinants tested.

Similar analysis was conducted with Genetic Algorithm for Recombination Detection (GARD) available in the Datamonkey web server (40). Similar results were found where a potential breakpoint was identified at position 1360 (86%) (according to the reference sequence PP422536 alignment) (AIC-c

baseline = 7844.9, c-AIC

breakpoint = 7729.2) (

Figure 4.b).

The latter analysis failed to determine the minor parent as the closest to the C terminal last 100 bp of our sequence, therefore that part was blasted on NCBI and the best three hits all included Swiss N1 genes (PQ098778.1, PQ098642.1, PQ098751.1) of the subtype H5N1 and the strains were isolated in 2022 and 2023 (pairwise identity set at 96.91%). The blast also revealed an important pairwise identity of 94.85% with strains isolated from cattle and milk from the USA (PV091375.1, PQ373713.1, PQ373729.2).

The recombination study was run again with the sequences obtained with the C-terminal blast (100 bp) included in the initial set tested. PP422536 and PP422535 maintained two potential breakpoints at positions [PP422536: 15 and 1374, PP422535: 29 and 1375] with the same methods (according to the reference sequence PP422536 alignment) when analyzed with RDP 4 software (

Table 3). The analysis also recognized an Egyptian sequence as the major parent [OQ607880.1 (A/chicken/Egypt/F71-F114C/2022(H5N1))], and FJ032003.1 (A/mallard/ON/499/2005(H5N1)) remained as the minor parent. The pairwise identity with the major parent between the two breakpoints was comparable to the first test (48% to 99%). Regarding the minor parent, pairwise identity was mostly lower than 12% when compared to PP422536 (

Figure 4.c). The second attempt also didn’t determine the parental sequence of the C-terminal region.

GARD was similarly used with the same set of sequences, and two potential hotspots were detected at position 1336 (56%) and 1339 (34%) (according to the reference sequence PP422536 alignment) (AIC-c

baseline = 9604.95, c-AIC

1336breakpoint = 9552.5) (

Figure 4.d). The raw data (chromatogram) of PP422536 carrying the potential recombination hotspots is shown in

Figure 4.e.

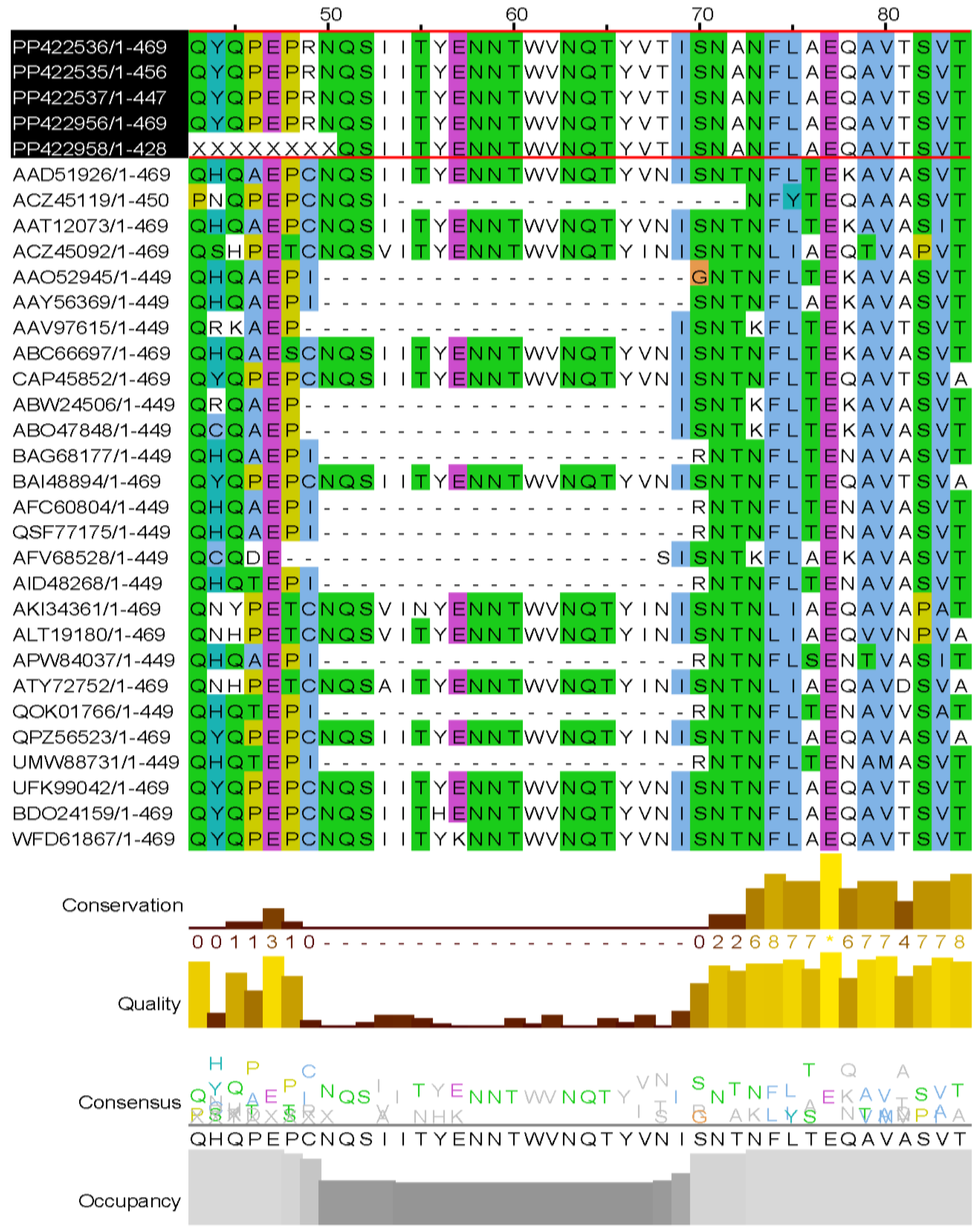

Stalk Characterization

Stalk deletion in NA is considered a virulence trait contributing to the high pathogenicity character within influenza viruses, and it was observed in N1, N2, N3, N5, N6, and N7 subtypes (43,44). Our isolates’ N1 sequences were aligned using

Clustal Omega on NGPhylogeny (45) with random sequences from isolates of each year, starting with Gs/GD strain (A/goose/Guangdong/1/1996) downloaded from the Influenza Virus database (

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/FLU/Database/nph-select.cgi?). The alignment was then represented on JalviewJS (RRID:SCR_006459) (46). According to Hermann et Krammer (2025) (43), the stalk deletion appeared in 2002 and remained until 2022 in H5N1 strains. However, when recreating the same flow, we observed that our isolates maintained their long stalk, and in addition, the deletion was sporadic during the period mentioned (

Figure 5). The excision involved 20 aa from positions 50 to 69 (according to GS/GD strain alignment).

Discussion

During the two epizooties of H5N8 (2020-2021) and H5N1 (2022-2023) that affected Algerian poultry production, samples were collected from infected animals raised in different farms across the country based on disease symptoms, mortality rate, and gross lesion examination. Following RT-PCR analyses that confirmed the presence of AIV genomes of the highly pathogenic H5N1 and H5N8 strains, here we sequenced six HA-H5 and five NA-N1 from H5N1 strains and nine HA-H5 and ten NA-N8 from H5N8 strains. Overall, the sequencing data targeted viruses circulating in eight affected farms by the H5N8 and five others by the H5N1 strains.

Pathotyping

It is now well established that pathological AIV H5N1 and H5N8 strains isolated in Africa from

migratory birds in Mauritania (47), Namibia

(48), Lesotho (49), and Egypt (50,51) share the same aa sequences of the cleavage site (CS)

. Interestingly, the great majority of the cases that shared similar lesions like those observed in animals infected with our strains (30); and those isolated in

[Nigeria (MF112620, MW961492,MW961484, MN759490), England (52), Serbia (PP853096), Netherlands (KR233690) and France (53)] shared the same aa composition of CS. However, heterogenous CS aa sequences were observed in the genomes of the H5N1 strains isolated in Nigeria in 2016 and France in 2015, and the H5N8 strain isolated in the Netherlands in 2014 (

Figure 6). The dissimilarities in some amino acids don’t seem to affect the strain’s infectivity and tropism.

Phylogenetic Analysis

The H5 (H5N8) phylogenetic tree revealed that our strain isolated in Algeria was close to that isolated in Nigeria (Chicken/Nigeria/2021(H5N8)) during the 2021 H5N8 outbreak that affected poultry. Our strain was also found to be close to a Chinese strain (Cygnus Columbianus/Hubei/2020 (H5N8)) isolated from one of the thirteen wild birds found dead in a lake in Hubei district in 2020 (54). There were also close similarities with other H5 genes, suggesting that reassortments happened before or after its transit in Algeria. The N8 gene was close to the number of isolates collected in 2020 from wild and domestic birds (France) (Kazakhstan).

Both genes of the H5N1 subtype seem related to a strain isolated in Mauritania from a dead pelican found in the National Park of Diawling with 2,140 other migratory birds (47). The outbreak was declared in February 2022, before the Algerian outbreak; therefore, it can be the same circulating strain. N1 sequences were similar to those isolated in 2022 from a black Tibetan bear in France, suggesting that the Algerian N1 might have the ability to fulfil the infection cycle within a mammal host.

Based on the sequences compared to our isolates and the migratory flyways crossing Algeria (30), the introduction of the two viruses was possible through one of the three corridors described. Regarding the H5N8 outbreak of 2020-2021, we can incriminate the East-Atlantic flyway if we consider China as the origin of the strain, which crossed Kazakhstan (West Asia) and France (Western Europe) before it arrived in Algeria. For the 2022-2023 H5N1 epizooty, it was carried through two possible flyways; therefore, if we take Egypt as the source of the studied strain, the corridor that crosses South-East Asia to reach Central America is plausible. On the other hand, if we incriminate Western Europe as the source of the strain, in this case France and Spain, migratory birds might have taken the East-Atlantic flyway before landing in Algeria and/or in Mauritania. These hypothetical origins of the Algerian strains align with the phylogenetic analysis that showed that the HA and NA studied were related to the Eurasian lineages and belonged to the 2.3.4.4b clade.

Recombination Events in the N1 Gene

As for the N1 gene, the consensus showed to be closer to the North American cluster. Further analysis was conducted to detect a recombination hotspot, and it revealed a potential breakpoint at position 1360 (according to GARD) or at 1380 (according to RDP 4). As the methods used didn’t point out the parental sequence of the C-terminal region, the blast conducted showed close homology to Swiss strains isolated during the same period of the Algerian H5N1 epizooty. Homologous recombination is known to be a rare event within influenza viruses (55); however, He et al. (7) previously determined a potential breakpoint in the N1 genes of H5N1 subtype at position 1090 within Chinese strains. These events were also encountered in PA, PB1, PB2, HA, and NP segments (7, 8, 56, 57).

Long Stalk Persistence

The aa multiple alignment conducted to verify the stalk deletion in our isolates showed the conservation of these 20 aa in comparison to different N1 sequences from different years. Results also showed that the deletion was not a persistent trait in other isolates; however, it might be a predominant motif in most strains (58, 59). This kind of deletion is known to confer an increase in pathogenicity and a better adaptability in hosts (60). It is also observed when the virus is transmitted from wild to domestic birds (24), suggesting that this change is probably associated with the variation noted in the HA’s CS during this host transition.

Conclusion

Highly pathogenic H5N8 and H5N1, belonging to clade 2.3.4.4b, struck Algeria and heavily damaged the poultry industry. Further molecular analysis was conducted to characterize the strain’s origin and pathotype. The H5N8 and H5N1 hemagglutinin and neuraminidase genes were studied separately. Although the highly pathogenic character of the isolates was already established based on mortality rate and necropsy observations, the presence of the polybasic cleavage site confirms this finding. The distant and nearest origin of both the subtypes of HA and NA genes is probably Eurasian, considering the proximity noted after phylogenetic analysis. However, the N1 gene seemed to carry a recombination breakpoint in the C-terminal region, and stalk deletion was also detected. Algeria is crossed by three different migratory flyways, future AIV-H5Nx introductions are plausible mainly through Europe and Asia. The latter can’t be controlled; however, dissemination across the different farms can be diminished if proper biosecurity measures and a suitable vaccination plan are applied.

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study's conception and design. A.N., K.R., and C.Y. performed PCR and semi-nested PCR analyses. A.N., C.Y., S.E.H., and G.D. performed sequencing and data analysis. A.N. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, and then all authors contributed to generating subsequent versions to get the final document. All authors read and approved the final draft of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Ladjali Farida's technical contribution. Partial financial supports were provided from University Blida1, Kara’s clinic, INRAE, and UGA.

References

- Bouvier, N.M.; Palese, P. The biology of influenza viruses. Vaccine 2008, 26, D49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.C.; Wilson, I.A. Influenza Hemagglutinin Structures and Antibody Recognition. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 2020, 10, a038778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafa, A.; Abdelwhab, E.; Mettenleiter, T.; Pleschka, S. Zoonotic Potential of Influenza A Viruses: A Comprehensive Overview. Viruses 2018, 10, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adnet, J.; Dina, J. Virus grippaux et Sars-CoV-2, sommes-nous prêts pour le futur ? Actualités Pharmaceutiques 2021, 60, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blot, M.; Chavanet, P.; Piroth, L. La grippe : mise au point pour les cliniciens. La Revue de Médecine Interne 2019, 40, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, S. Family Orthomyxoviridae. Viruses 2023, 253–264. [Google Scholar]

- He, C.-Q.; Xie, Z.; Han, G.-Z.; Dong, J.; Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Ma, L.; Tang, X.; Liu, X.; Pang, Y.; Li, G. Homologous Recombination as an Evolutionary Force in the Avian Influenza A Virus. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2008, 26, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Sun, L.; Li, R.; et al. Is a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus H5N1 fragment recombined in PB1 the key for the epidemic of the novel AIV H7N9 in China, 2013? International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016, 43, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Criado, M.F.; Swayne, D.E. Pathobiological Origins and Evolutionary History of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Viruses. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2020, 11, a038679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, T.; Werner, O. Avian Influenza; EFSA-Wiley, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, W.R.; Sierk, M.L. The limits of protein sequence comparison? Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2005, 15, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glisson, J.R.; McDougald, L.R.; Nolan, L.K.; Suarez, D.L.; Nair, V.L. Diseases of Poultry; John Wiley & Sons, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, B.; Munster, V.J.; Wallensten, A.; Waldenstrom, J.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Global Patterns of Influenza A Virus in Wild Birds. Science 2006, 312, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spronken, M.I.; Funk, M.; Gultyaev, A.P.; de Bruin, A.C.M.; Fouchier, R.A.M.; Richard, M. Nucleotide sequence as key determinant driving insertions at influenza A virus hemagglutinin cleavage sites. npj Viruses 2024, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Avian Influenza Virus; Humana Press, 2008.

- Bevins, S.N.; Shriner, S.A.; Cumbee, J.C.; et al. Intercontinental Movement of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Clade 2.3.4.4 Virus to the United States, 2021. Emerging infectious diseases. 2022, 28, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Torchetti, M.K.; Winker, K.; Ip, H.S.; Song, C.S.; Swayne, D.E. Intercontinental Spread of Asian-Origin H5N8 to North America through Beringia by Migratory Birds. García-Sastre A, ed. Journal of Virology. 2015, 89, 6521–6524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; de Vries, E.; McBride, R.; et al. Highly Pathogenic Influenza A(H5Nx) Viruses with Altered H5 Receptor-Binding Specificity. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2017, 23, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusaro, A.; Zecchin, B.; Vrancken, B.; et al. Disentangling the role of Africa in the global spread of H5 highly pathogenic avian influenza. Nature Communications 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahab, E.M.; Beer, M. Panzootic HPAIV H5 and risks to novel mammalian hosts. npj Viruses 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caserta, L.C.; Frye, E.A.; Butt, S.L.; Laverack, M.; Nooruzzaman, M.; Covaleda, L.M.; Thompson, A.C.; Koscielny, M.P.; Cronk, B.; Johnson, A.; Kleinhenz, K.; Edwards, E.E.; Gomez, G.; Hitchener, G.; Martins, M.; Kapczynski, D.R.; Suarez, D.L.; Alexander Morris, E.R.; Hensley, T.; Beeby, J.S.; Lejeune, M.; Swinford, A.K.; Elvinger, F.; Dimitrov, K.M.; Diel, D.G. Spillover of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus to dairy cattle. Nature 2024, 634, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fao, Global AIV with Zoonotic Potential. AnimalHealth.

- Wille, M.; Barr, I.G. The current situation with H5N1 avian influenza and the risk to humans. Internal Medicine Journal 2024, 54, 1775–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahid, M.J.; Nolting, J.M. Dynamics of a Panzootic: Genomic Insights, Host Range, and Epidemiology of the Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Clade 2.3.4.4b in the United States. Viruses. 2025, 17, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, R.; Liu, Q.; et al. Genomic Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of Five Avian Influenza H5N1 Subtypes from Wild Anser indicus in Yunnan, China. Veterinary Sciences. 2025, 12, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Dou, H.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Genetic evolution and molecular characteristics of avian influenza viruses in Jining from 2018 to 2023. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briand, F.X.; Palumbo, L.; Martenot, C.; et al. Highly Pathogenic Clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 Influenza Virus in Seabirds in France, 2022–2023. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, H.; Sanad, Y.M. Comprehensive Insights into Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 in Dairy Cattle: Transmission Dynamics, Milk-Borne Risks, Public Health Implications, Biosecurity Recommendations, and One Health Strategies for Outbreak Control. Pathogens. 2025, 14, 278–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Torchetti, M.K.; Winker, K.; Ip, H.S.; Song, C.S.; Swayne, D.E. Intercontinental Spread of Asian-Origin H5N8 to North America through Beringia by Migratory Birds. J Virol 2015, 89, 6521–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammali, N.; Kara, R.; Guetarni, D.; Chebloune, Y. Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N8 and H5N1 outbreaks in Algerian avian livestock production. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2024, 111, 102202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoper, D.; Hoffmann, B.; Beer, M. Simple, sensitive, and swift sequencing of complete H5N1 avian influenza virus genomes. J Clin Microbiol 2009, 47, 674–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO information for the molecular detection of influenza viruses: Annex 1. E. Protocol removed: Conventional RT-PCR A(H5N1) • Annex 2. A. Protocol 2 added: One-step real-time RT-PCR for the detection of influenza A viruses (Page 25) • Annex 2. B. Protocol 2 updated: Real-time RT-PCR one-step duplex for the detection of Influenza type A subtype H1pdm09 and subtype H3 (Page 28) • Annex 2. D. Protocol 2 updated: Real-time RT-PCR for the detection of A(H5) HA gene (Page 37); 2017.

- Herve, S.; Schmitz, A.; Briand, F.X.; Gorin, S.; Queguiner, S.; Niqueux, E.; Paboeuf, F.; Scoizec, A.; Le Bouquin-Leneveu, S.; Eterradossi, N.; Simon, G. Serological Evidence of Backyard Pig Exposure to Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N8 Virus during 2016-2017 Epizootic in France. Pathogens 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Evans, D.H. Detection and identification of human influenza viruses by the polymerase chain reaction. Journal of Virological Methods 1991, 33, 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Schwartz, S.; Wagner, L.; Miller, W. A Greedy Algorithm for Aligning DNA Sequences. Journal of Computational Biology 2000, 7, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dereeper, A.; Guignon, V.; Blanc, G.; Audic, S.; Buffet, S.; Chevenet, F.; Dufayard, J.F.; Guindon, S.; Lefort, V.; Lescot, M.; Claverie, J.M.; Gascuel, O. Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Research 2008, 36, W465–W469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Molecular Biology And Evolution 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K.; Nei, M.; Kumar, S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 11030–11035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.P.; Murrell, B.; Golden, M.; Khoosal, A.; Muhire, B. RDP4: Detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evolution 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosakovsky Pond, S.L.; Posada, D.; Gravenor, M.B.; Woelk, C.H.; Frost, S.D.W. Automated Phylogenetic Detection of Recombination Using a Genetic Algorithm. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2006, 23, 1891–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraris, O.; Lina, B. Mutations of neuraminidase implicated in neuraminidase inhibitors resistance. Journal of Clinical Virology 2008, 41, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smietanka, K.; Fusaro, A.; Domanska-Blicharz, K.; Salviato, A.; Monne, I.; Dundon, W.G.; Cattoli, G.; Minta, Z. Full-Length Genome Sequencing of the Polish HPAI H5N1 Viruses Suggests Separate Introductions in 2006 and 2007. Avian Diseases 2010, 54, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, E.; Krammer, F. Clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 neuraminidase has a long stalk, which is in contrast to most highly pathogenic H5N1 viruses circulating between 2002 and 2020. mBio 2025, e0398924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stech, O.; Veits, J.; Abdelwhab, E.M.; Wessels, U.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Stech, J. The Neuraminidase Stalk Deletion Serves as Major Virulence Determinant of H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Viruses in Chicken. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 13493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, F.; Correia, D.; Lefort, V.; Doppelt-Azeroual, O.; Mareuil, F.; Cohen-Boulakia, S.; Gascuel, O. NGPhylogeny.fr: new generation phylogenetic services for non-specialists. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 47, W260–W265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Procter, J.B.; Martin, D.M.A.; Clamp, M.; Barton, G.J. Jalview Version 2--a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diambar Beyit, A.; Meki, I.K.; Barry, Y.; Haki, M.L.; El Ghassem, A.; Hamma, S.M.; Abdelwahab, N.; Doumbia, B.; Hacen Ahmed, B.; Daf Sehla, D. Avian influenza H5N1 in a great white pelican (Pelecanus onocrotalus), Mauritania 2022. Veterinary Research Communications, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Molini, U.; Yabe, J.; Meki, I.K.; Ouled Ahmed Ben Ali, H.; Settypalli, T.B.K.; Datta, S.; Coetzee, L.M.; Hamunyela, E.; Khaiseb, S.; Cattoli, G.; Lamien, C.E.; Dundon, W.G. Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus outbreak among Cape cormorants (Phalacrocorax capensis) in Namibia, 2022. Emerg Microbes Infect 2023, 12, 2167610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makalo, M.R.J.; Dundon, W.G.; Settypalli, T.B.K.; Datta, S.; Lamien, C.E.; Cattoli, G.; Phalatsi, M.S.; Lepheana, R.J.; Matlali, M.; Mahloane, R.G.; Molomo, M.; Mphaka, P.C. Highly pathogenic avian influenza (A/H5N1) virus outbreaks in Lesotho, May 2021. Emerg Microbes Infect 2022, 11, 757–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosaad, Z.; Elhusseiny, M.H.; Zanaty, A.; Fathy, M.M.; Hagag, N.M.; Mady, W.H.; Said, D.; Elsayed, M.M.; Erfan, A.M.; Rabie, N.; Samir, A.; Samy, M.; Arafa, A.S.; Selim, A.; Abdelhakim, A.M.; Lindahl, J.F.; Eid, S.; Lundkvist, A.; Shahein, M.A.; Naguib, M.M. Emergence of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A Virus (H5N1) of Clade 2.3.4.4b in Egypt, 2021-2022. Pathogens 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehia, N.; Naguib, M.M.; Li, R.; Hagag, N.; El-Husseiny, M.; Mosaad, Z.; Nour, A.; Rabea, N.; Hasan, W.M.; Hassan, M.K.; Harder, T.; Arafa, A.A. Multiple introductions of reassorted highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses (H5N8) clade 2.3.4.4b causing outbreaks in wild birds and poultry in Egypt. Infect Genet Evol 2018, 58, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byrne, A.; James, J.; Mollett, B.C.; Steven De, M.; Lewis, T.; Czepiel, M.; Seekings, A.H.; Mahmood, S.; Thomas, S.S.; Ross, C.S.; Dominic, J.F.B.; McMenamy, M.; Bailie, V.; Lemon, K.; Hansen, R.; Falchieri, M.; Lewis, N.S.; Reid, S.M.; Brown, I.H.; Banyard, A.C. Investigating the genetic diversity of H5 avian influenza in the UK 2020-2022. bioRxiv (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory) 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gaide, N.; Lucas, M.-N.; Delpont, M.; Croville, G.; Bouwman, K.M.; Papanikolaou, A.; van der Woude, R.; Gagarinov, I.A.; Boons, G.-J.; De Vries, R.P.; Volmer, R.; Teillaud, A.; Vergne, T.; Bleuart, C.; Le Loc’h, G.; Delverdier, M.; Guérin, J.-L. Pathobiology of highly pathogenic H5 avian influenza viruses in naturally infected Galliformes and Anseriformes in France during winter 2015–2016. Veterinary Research 2022, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Zhou, H.; Fan, L.; Zhu, G.; Li, Y.; Chen, G.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Zheng, H.; Feng, W.; Chen, J.; Yang, G.; Chen, Q. Emerging highly pathogenic avian influenza (H5N8) virus in migratory birds in Central China, 2020. Emerg Microbes Infect 2021, 10, 1503–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, M.F.; Zhou, Y.; Taubenberger, J.K.; Holmes, E.C. Homologous Recombination Is Very Rare or Absent in Human Influenza A Virus. Journal of Virology 2008, 82, 4807–4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, M.J. Recombination in the Hemagglutinin Gene of the 1918 "Spanish Flu". Science 2001, 293, 1842–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.Q.; Han, G.Z.; Wang, D.; et al. Homologous recombination evidence in human and swine influenza A viruses. Virology. 2008, 380, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Yu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Tu, J.; Zou, W.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, A.; Yu, Z.; Ye, Z.; Chen, H.; Jin, M. The Special Neuraminidase Stalk-Motif Responsible for Increased Virulence and Pathogenesis of H5N1 Influenza A Virus. PLOS ONE 2009, 4, e6277–e6277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumenkrantz, D.; Roberts, K.L.; Shelton, H.; Lycett, S.; Barclay, W.S. The short stalk length of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus neuraminidase limits transmission of pandemic H1N1 virus in ferrets. J Virol 2013, 87, 10539–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, J.L.; Gilbertson, B.P.; Trifkovic, S.; Brown, L.E.; McKimm-Breschkin, J.L. Influenza Virus Neuraminidase Structure and Functions. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).