Submitted:

06 September 2025

Posted:

09 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells, Viruses, Sera, and Reagents

2.2. Antigenic Analysis

2.3. HA1 Protein Sequence Alignment and Analysis

2.4. Rescue and Antigenic Validation of Single-Site Mutant Viruses

2.5. Structural and Mutational Simulation Analysis of the HA1 128 Amino Acid Position

3. Results

3.1. HI Assays Reveal Significant Antigenic Differences Between TJ312 and GD1536

3.2. HA1 Protein Sequence Alignment Reveals Multiple Amino Acid Differences in Antigenic Sites

3.3. The Amino Acid at Position 128 in the HA1 Protein Is a Key Determinant of Antigenic Differences Between TJ312 and GD1536 Strains

| Purpose | Primers (5’-3’) a | |

| Forward | Reverse | |

| TJ312/Mut-1 | TTAAAAGCTGATACCCTTTGTATAGGCTACCATGCCAAC | GGCATGGTAGCCTATACAAAGGGTATCAGCTTTTAATGT |

| TJ312/Mut-2 | GACACTGTCGACACAGTATTGGAGAAAAATGTGACTGT | AGTCACATTTTTCTCCAATACTGTGTCGACAGTGTCTGTG |

| TJ312/Mut-3 | ATTTACTGGAAGACAAGCATAATGGGAAACTCTGCAGCC | CAGAGTTTCCCATTATGCTTGTCTTCCAGTAAATTAACTG |

| TJ312/Mut-4 | GAAACTCTGCAAACTGAGAGGAGTGGCCCCCTTACAACTG | TAAGGGGGCCACTCCTCTCAGTTTGCAGAGTTTCCCATT |

| TJ312/Mut-5 | CTCTGCAAACTGAGAGGAGTGGCCCCCTTACAACTGGGAAACTG | CAGTTGTAAGGGGGCCACTCCTCTCAGTTTGCAGAGTTTCCCAT |

| TJ312/Mut-6 | AGATCCCCTTACAACTGGGAAAATGCAACGTAGCAGGATG | ATCCATCCTGCTACGTTGCATTTTCCCAGTTGTAAG |

| TJ312/Mut-7 | TACAACTGGGAAACTGCAACATAGCAGGATGGATCCTTG | TTGCCAAGGATCCATCCTGCTATGTTGCAGTTTCCCAGT |

| TJ312/Mut-8 | CTTGGCAACCCAGAATGTGAATCGCTGTCCACAGCGAGATCGTGGTCTT | GATCTCGCTGTGGACAGCGATTCACATTCTGGGTTGCCAAGGATCCATC |

| TJ312/Mut-9 | TTCGTGGTCTTACATAGTAGAGACTTCAAATTCAAAAAAT | TTTGAATTTGAAGTCTCTACTATGTAAGACCACGAATTCG |

| TJ312/Mut-10 | TAGAGACTTCAAATTCAGACAATGGAGCATGCTACCCCG | GGGTAGCATGCTCCATTGTCTGAATTTGAAGTCTCTAT |

| TJ312/Mut-11 | CAAATTCAAAAAATGGAACATGCTACCCCGGAGAATTTGC | AATTCTCCGGGGTAGCATGTTCCATTTTTTGAATTTGAAG |

| TJ312/Mut-12 | CTACCCCGGAGATTTTATTAATTATGAAGAGTTAAAGGAG | TTAACTCTTCATAATTAATAAAATCTCCGGGGTAGCATGC |

| TJ312/Mut-13 | CTGATTATGAAGAGTTAAGGGAGCAGCTGAGTACAGTTTC | ACTGTACTCAGCTGCTCCCTTAACTCTTCATAATCAGC |

| TJ312/Mut-14 | TAAAGGAGCAGCTGAGTTCAGTTTCTTCATTTGAAAGAT | CTTTCAAATGAAGAAACTGAACTCAGCTGCTCCTTTAACT |

| TJ312/Mut-15 | AAATTTTCCCAAAGACAAGTTCATGGCCACACCATGATAC | TGGTGTGGCCATGAACTTGTCTTTGGGAAAATTTCAAATC |

| TJ312/Mut-16 | AGGCAACTTCATGGCCAAACCATGATACCACCAGAGGTAC | CCTCTGGTGGTATCATGGTTTGGCCATGAAGTTGCCTTTG |

| TJ312/Mut-17 | GGCCACACCATGATTCCGACAAAGGTACCACGGTTTCATG | ACCGTGGTACCTTTGTCGGAATCATGGTGTGGCCATGAAG |

| TJ312/Mut-18 | CACCAGAGGTGTCACGGCTGCATGCCCCCACGCTGGAGCCAACAGCTTTTATCG | TGTTGGCTCCAGCGTGGGGGCATGCAGCCGTGACACCTCTGGTGGTATCATGGT |

| TJ312/Mut-19 | GCTCCCACTCTGGAGCCAAAAGCTTTTATCGGAATTTACT | AAATTCCGATAAAAGCTTTTGGCTCCAGAGTGGGAGCATG |

| TJ312/Mut-20 | GAGCCAACAGCTTTTATAAGAATTTACTATGGATAGT | ACTATCCATAGTAAATTCTTATAAAAGCTGTTGGCTCCAG |

| TJ312/Mut-21 | TTTATCGGAATTTAATATGGCTAGTAAAGAAAGGAAACTC | CCTTTCTTTACTAGCCATATTAAATTCCGATAAAAGCTGT |

| TJ312/Mut-22 | CTAAGCTCAACCAGACATACATAAACGATAAGGGAAAGGAAGTGCTTGT | TTTCCCTTATCGTTTATGTATGTCTGGTTGAGCTTAGGATAGGAGTTTCT |

| TJ312/Mut-23 | GAAAGGAAGTGCTTGTACTTTGGGGAGTGCACCACCCTCC | GGGTGGTGCACTCCCCAAAGTACAAGCACTTCCTTTCCCT |

| TJ312/Mut-24 | TGCTTGTAATTTGGGGAATTCACCACCCTCCAACTGATAG | TCAGTTGGAGGGTGGTGAATTCCCCAAATTACAAGCACTT |

| TJ312/Mut-25 | CACCCTCCAACTATTGCTGTCCAAGAAAGCCTCTACCAGAATAATCATAC | TTCTGGTAGAGGCTTTCTTGGACAGCAATAGTTGGAGGGTGGTGCACTC |

| TJ312/Mut-26 | CTACCAGAATGCTGATGCATATGTTTCAGTTGGATCATC | ACTGAAACATATGCATCAGCATTCTGGTAGAGGGTTTGTT |

| TJ312/Mut-27 | ATAATCATACATATGTTTTTGTTGGATCATCAAAATACT | TATTTTGATGATCCAACAAAAACATATGTATGATTATTCT |

| TJ312/Mut-28 | TTCAGTTGGAACATCAAGATACTCCAAAAAGTTCAAACCAGAAATAGTAGCAAGACC | TACTATTTCTGGTTTGAACTTTTTGGAGTATCTTGATGTTCCAACTGAAACATATGTAT |

| TJ312/Mut-29 | TCACACCAGAAATAGCAACAAGACCTAAAGTCAGAGAAC | CTGACTTTAGGTCTTGTTGCTATTTCTGGTGTGAACCTTT |

| TJ312/Mut-30 | CTAAAGTCAGAGATCAAGAAGGCAGAATGAATTATTACTG | TTCATTCTGCCTTCTTGATCTCTGACTTTAGGTCTTGCT |

| TJ312/Mut-31 | ACTGGACACTGGTAGAACCAGGGGACACCATAACTTTTG | ATGGTGTCCCCTGGTTCTACCAGTGTCCAGTAATAATTC |

| TJ312/Mut-32 | TGTTAGATCAAGGGGACAAAATAACTTTTGAAGCCACTGG | GTGGCTTCAAAAGTTATTTTGTCCCCTTGATCTAACAGTG |

| TJ312/Mut-33 | GCCACTGGAAATTTAGTAGTACCAAGGTATGCATTTGCATTGAAAAAAGG | TTTCAATGCAAATGCATACCTTGGTACTACTAAATTTCCAGTGGCTTC |

| TJ312/Mut-34 | GCATGCATTTACAATGGAAAGAGATGCTGGATCTGGAATTATGAGGTCGG | TAATTCCAGATCCAGCATCTCTTTCCATTGTAAATGCATGCCATGGTGCT |

| TJ312/Mut-35 | CTAGTTCTGGAATTATCATTTCGGATGCTCAGGTTCAC | ACCTGAGCATCCGAAATGATAATTCCAGAACTAGAACCTT |

| TJ312/Mut-36 | TTATGAGGTCGGATACTCCGGTTCACAATTGCACTAC | GTGCAATTGTGAACCGGAGTATCCGACCTCATAATTCCAG |

| TJ312/Mut-37 | ATGCTCAGGTTCACGATTGCAATACAACGTGCCAAACTCCCCATGGGGC | TGGGGAGTTTGGCACGTTGTATTGCAATCGTGAACCTGAGCATCCGACC |

| TJ312/Mut-38 | CAAAGTGCCAAACTCCCGAGGGGGCCTTGAAAGGCAACCT | TTGCCTTTCAAGGCCCCCTCGGGAGTTTGGCACTTTGTAG |

| TJ312/Mut-39 | CATGGGGCCATAAACACCAGCCTTCCCTTTCAGAATGTAC | AAGGGAAGGCTGGTGTTTATGGCCCCATGGGGAGTTTGGC |

| TJ312/Mut-40 | TTCAGAATGTACATCCCATCACTATTGGGAAATGCC | GGGCATTTCCCAATAGTGATGGGATGTACATTCTGAAAGG |

| TJ312/Mut-41 | AATATGTTAAAAGCACCAAACTGAGAATGGCAACAGGACT | CCTGTTGCCATTCTCAGTTTGGTGCTTTTAACATATTTGG |

| TJ312/Mut-42 | AAAGCACCCAACTGAGACTGGCAACAGGACTAAGAAATAT | TTTCTTAGTCCTGTTGCCAGTCTCAGTTGGGTGCTT |

| TJ312/Mut-43 | CAACAGGACTAAGAAATGTCCCCTCTATTCAATCCAGAGG | CTGGATTGAATAGAGGGGACATTTCTTAGTCCTGTTGCC |

| GD1536/N128H | TTCATGGCCTCATCATGACTCGGAC | TCCGAGTCATGATGAGGCCATGAAC |

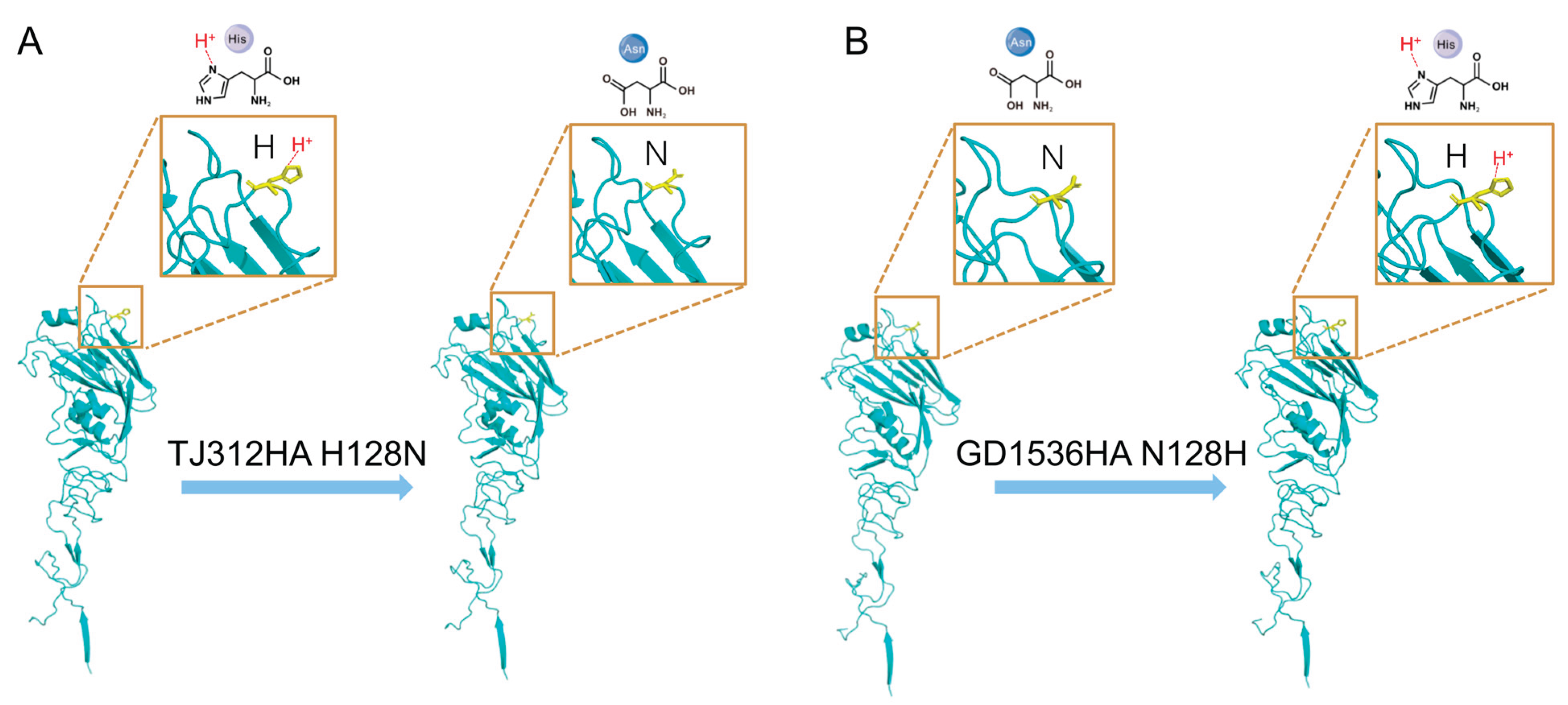

3.4. Structural Analysis Reveals the Impact of the 128 Amino Acid Substitution on HA1 Conformation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson TK, Macken CA, Lewis NS, Scheuermann RH, Van Reeth K, et al. 2016. A Phylogeny-Based Global Nomenclature System and Automated Annotation Tool for H1 Hemagglutinin Genes from Swine Influenza A Viruses. mSphere 1. [CrossRef]

- Caton AJ, Brownlee GG, Yewdell JW, Gerhard W. 1982. The antigenic structure of the influenza virus A/PR/8/34 hemagglutinin (H1 subtype). Cell 31:417-27. [CrossRef]

- Durrwald R, Wedde M, Biere B, Oh DY, Hessler-Klee M, et al. 2020. Zoonotic infection with swine A/H1(av)N1 influenza virus in a child, Germany, June 2020. Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin 25.

- Eggink D, Kroneman A, Dingemans J, Goderski G, van den Brink S, et al. 2025. Human infections with Eurasian avian-like swine influenza virus detected by coincidence via routine respiratory surveillance systems, the Netherlands, 2020 to 2023. Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin 30. [CrossRef]

- Gerhard W, Yewdell J, Frankel ME, Webster R. 1981. Antigenic structure of influenza virus haemagglutinin defined by hybridoma antibodies. Nature 290:713-7. [CrossRef]

- He F, Yu H, Liu L, Li X, Xing Y, et al. 2024. Antigenicity and genetic properties of an Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine influenza virus in Jiangsu Province, China. Biosaf Health 6:319-26. [CrossRef]

- He Y, Song S, Wu J, Wu J, Zhang L, et al. 2024. Emergence of Eurasian Avian-Like Swine Influenza A (H1N1) virus in a child in Shandong Province, China. BMC infectious diseases 24:550. [CrossRef]

- He YJ, Song SX, Wu J, Wu JL, Zhang LF, et al. 2024. Emergence of Eurasian Avian-Like Swine Influenza A (H1N1) virus in a child in Shandong Province, China. Bmc Infectious Diseases 24. [CrossRef]

- Henritzi D, Petric PP, Lewis NS, Graaf A, Pessia A, et al. 2020. Surveillance of European Domestic Pig Populations Identifies an Emerging Reservoir of Potentially Zoonotic Swine Influenza A Viruses. Cell Host Microbe 28:614-27 e6. [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne ED, Smith C, Brett I, Pokorny BA, Johansson B, Cox N. 2002. The total influenza vaccine failure of 1947 revisited: Major intrasubtypic antigenic change can explain failure of vaccine in a post-World War II epidemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99:10748-52. [CrossRef]

- Li X, Guo L, Liu C, Cheng Y, Kong M, et al. 2019. Human infection with a novel reassortant Eurasian-avian lineage swine H1N1 virus in northern China. Emerg Microbes Infect 8:1535-45. [CrossRef]

- Meng F, Chen Y, Song ZC, Zhong Q, Zhang YJ, et al. 2023. Continued evolution of the Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine influenza viruses in China. Science China-Life Sciences 66:269-82. [CrossRef]

- Meng F, Yang H, Qu Z, Chen Y, Zhang Y, et al. 2022. A Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine influenza reassortant virus became pathogenic and highly transmissible due to mutations in its PA gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 119:e2203919119. [CrossRef]

- Neumann G, Noda T, Kawaoka Y. 2009. Emergence and pandemic potential of swine-origin H1N1 influenza virus. Nature 459:931-9. [CrossRef]

- Parys A, Vandoorn E, King J, Graaf A, Pohlmann A, et al. 2021. Human Infection with Eurasian Avian-Like Swine Influenza A(H1N1) Virus, the Netherlands, September 2019. Emerging Infectious Diseases 27:939-43. [CrossRef]

- Pensaert M, Ottis K, Vandeputte J, Kaplan MM, Bachmann PA. 1981. Evidence for the natural transmission of influenza A virus from wild ducts to swine and its potential importance for man. Bull World Health Organ 59:75-8.

- Retamal M, Abed Y, Rheaume C, Baz M, Boivin G. 2017. In vitro and in vivo evidence of a potential A(H1N1)pdm09 antigenic drift mediated by escape mutations in the haemagglutinin Sa antigenic site. The Journal of general virology 98:1224-31. [CrossRef]

- Schotsaert M, García-Sastre A. 2016. A High-Resolution Look at Influenza Virus Antigenic Drift. Journal of Infectious Diseases 214:982-. [CrossRef]

- Shih ACC, Hsiao TC, Ho MS, Li WH. 2007. Simultaneous amino acid substitutions at antigenic sites drive influenza A hemagglutinin evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104:6283-8. [CrossRef]

- Smith DJ, Forrest S, Ackley DH, Perelson AS. 1999. Variable efficacy of repeated annual influenza vaccination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96:14001-6. [CrossRef]

- Smith GJ, Vijaykrishna D, Bahl J, Lycett SJ, Worobey M, et al. 2009. Origins and evolutionary genomics of the 2009 swine-origin H1N1 influenza A epidemic. Nature 459:1122-5. [CrossRef]

- Stray SJ, Pittman LB. 2012. Subtype- and antigenic site-specific differences in biophysical influences on evolution of influenza virus hemagglutinin. Virol J 9:91. [CrossRef]

- Sun H, Xiao Y, Liu J, Wang D, Li F, et al. 2020. Prevalent Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine influenza virus with 2009 pandemic viral genes facilitating human infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117:17204-10. [CrossRef]

- van Diemen PM, Byrne AMP, Ramsay AM, Watson S, Nunez A, et al. 2023. Interspecies Transmission of Swine Influenza A Viruses and Human Seasonal Vaccine-Mediated Protection Investigated in Ferret Model. Emerg Infect Dis 29:1798-807. [CrossRef]

- Vijaykrishna D, Smith GJ, Pybus OG, Zhu H, Bhatt S, et al. 2011. Long-term evolution and transmission dynamics of swine influenza A virus. Nature 473:519-22. [CrossRef]

- Wang DY, Qi SX, Li XY, Guo JF, Tan MJ, et al. 2013. Human infection with Eurasian avian-like influenza A(H1N1) virus, China. Emerg Infect Dis 19:1709-11. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Chen Y, Chen H, Meng F, Tao S, et al. 2022. A single amino acid at position 158 in haemagglutinin affects the antigenic property of Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine influenza viruses. Transboundary and emerging diseases 69:e236-e43. [CrossRef]

- Wu NC, Wilson IA. 2020. Influenza Hemagglutinin Structures and Antibody Recognition. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 10. [CrossRef]

- Xie JF, Zhang YH, Zhao L, Xiu WQ, Chen HB, et al. 2018. Emergence of Eurasian Avian-Like Swine Influenza A (H1N1) Virus from an Adult Case in Fujian Province, China. Virol Sin 33:282-6. [CrossRef]

- Xu C, Zhang N, Yang Y, Liang W, Zhang Y, et al. 2022. Immune Escape Adaptive Mutations in Hemagglutinin Are Responsible for the Antigenic Drift of Eurasian Avian-Like H1N1 Swine Influenza Viruses. Journal of virology 96:e0097122. [CrossRef]

- Xu R, Ekiert DC, Krause JC, Hai R, Crowe JE, Jr., Wilson IA. 2010. Structural basis of preexisting immunity to the 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza virus. Science 328:357-60. [CrossRef]

- Yang H, Chen Y, Qiao C, He X, Zhou H, et al. 2016. Prevalence, genetics, and transmissibility in ferrets of Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine influenza viruses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113:392-7. [CrossRef]

- Zhu W, Zhang H, Xiang X, Zhong L, Yang L, et al. 2016. Reassortant Eurasian Avian-Like Influenza A(H1N1) Virus from a Severely Ill Child, Hunan Province, China, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis 22:1930-6. [CrossRef]

- Zhu WF, Feng ZM, Chen YK, Yang L, Liu J, et al. 2019. Mammalian-adaptive mutation NP-Q357K in Eurasian H1N1 Swine Influenza viruses determines the virulence phenotype in mice. Emerg Microbes Infec 8:989-99. [CrossRef]

| Viruses | Virus rescue | |

| Mutation of HA | Successfully rescued | |

| TJ312/Mut-1 | I6L, V8I | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-2 | I22V | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-3 | N38D, S39K | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-4 | S46K, N48R, K50V, I51A | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-5 | Q54H | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-6 | N57K | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-7 | V60I | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-8 | K69E, D71E, L72S, L74S, N77R | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-9 | I83V | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-10 | K89D | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-11 | A92T | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-12 | E97D, A99I, D100N | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-13 | K105R | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-14 | T110S | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-15 | A123T, T124S | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-16 | H128N | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-17 | T131S, T132D, R133K | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-18 | T135V, V137A, S138A, S140P, S142A | Noa |

| TJ312/Mut-19 | N145K | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-20 | R149K | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-21 | L152I, I154L | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-22 | S165N, K166Q, S167T, T169I, N171D | No |

| TJ312/Mut-23 | I179L | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-24 | V182I | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-25 | D188I, S189A, D190V, Q192E, T193S | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-26 | N198A, H199D, T200A | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-27 | S203F | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-28 | S206T, K208R, Y210S, R212K, T214K | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-29 | V218A, A219T | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-30 | E225D, A227E | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-31 | L237V, D237E, Q239P | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-32 | T242K | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-33 | I252V, A253V, W255R, H256Y | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-34 | A259T, L260M, K261E, K262R, G263D, S264A S265G | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-35 | M269I, R270I | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-36 | A273T, Q274P | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-37 | N277D, T279N, K281T | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-38 | H286E | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-39 | L289I, K290N, G291T, N292S | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-40 | V301I | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-41 | Q314K | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-42 | M317L | Yes |

| TJ312/Mut-43 | I324V | Yes |

| Virus | Genetic group | Ferret antisera | |||

| TJ312 | GD1536 | GD104 | GX18 | ||

| TJ312 | EA1 | 640a | 80 | 20 | 640 |

| GD1536 | 2009/H1N1 | 40 | 1280 | 20 | 320 |

| GD104 | EA2 | <20 b | <20 | 1280 | 20 |

| GX18 | EA1 | 160 | 160 | 20 | 640 |

| Virus | Ferret antisera | Virus | Ferret antisera | |||

| TJ312 | GD1536 | TJ312 | GD1536 | |||

| TJ312 | 640a | 80 | TJ312/Mut-21 | 640 | 80 | |

| GD1536 | 40 | 1280 | TJ312/Mut-22 | - | - | |

| chimeric G-T | 40 | 1280 | TJ312/Mut-23 | 640 | 40 | |

| chimeric T-G | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-24 | 640 | 80 | |

| TJ312/Mut-1 | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-25 | 160 | 10 | |

| TJ312/Mut-2 | 640 | 40 | TJ312/Mut-26 | 640 | 80 | |

| TJ312/Mut-3 | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-27 | 640 | 160 | |

| TJ312/Mut-4 | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-28 | 640 | 80 | |

| TJ312/Mut-5 | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-29 | 640 | 40 | |

| TJ312/Mut-6 | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-30 | 320 | 80 | |

| TJ312/Mut-7 | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-31 | 640 | 80 | |

| TJ312/Mut-8 | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-32 | 640 | 80 | |

| TJ312/Mut-9 | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-33 | 640 | 80 | |

| TJ312/Mut-10 | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-34 | 640 | 40 | |

| TJ312/Mut-11 | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-35 | 640 | 80 | |

| TJ312/Mut-12 | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-36 | 640 | 80 | |

| TJ312/Mut-13 | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-37 | 640 | 40 | |

| TJ312/Mut-14 | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-38 | 640 | 80 | |

| TJ312/Mut-15 | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-39 | 640 | 80 | |

| TJ312/Mut-16 | 160 | 320 | TJ312/Mut-40 | 640 | 80 | |

| TJ312/Mut-17 | 320 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-41 | 640 | 80 | |

| TJ312/Mut-18 | -b | - | TJ312/Mut-42 | 640 | 80 | |

| TJ312/Mut-19 | 640 | 80 | TJ312/Mut-43 | 640 | 80 | |

| TJ312/Mut-20 | 640 | 80 | GD1536/ N128H | 320 | 320 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).