1. Introduction

Highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza viruses (AIVs) have evolved into various NA subtypes (H5Nx), and the cocirculation of highly pathogenic (HP) H5Nx AIVs with low-pathogenicity (LP) H9N2 AIVs is not uncommon [

1,

2]. Among these subtypes, the H5N1 and H9N2 subtypes are the most problematic, with reported cases of infections in various mammals, including humans [

3,

4,

5]. In Korea, HP H5N1, H5N6, and H5N8 AIVs, as well as the LP H9N2 AIV, continue to cause significant economic losses to the poultry industry, but vaccines against only H9N2 AI have been approved to date [

6,

7,

8]. Serological differentiation of infected from vaccinated animals (DIVA) remains an important prerequisite for developing vaccines against HP AIVs. Recent studies have shown that while the hemagglutinin (HA) protein is the primary antigen in influenza vaccines, the neuraminidase (NA) protein also plays a crucial role in effective virus neutralization and protection [

9,

10]. Therefore, developing an effective H5N2 vaccine strain for dual protection against H5Nx and H9N2 AIVs could be valuable for NA-based DIVA strategies for the detection of specific antibodies against N1, N6 and N8 [

11].

Efforts have been made to increase viral titers and decrease the mammalian pathogenicity of vaccine strains. The balance between HA and NA activities is crucial for efficient viral replication in embryonated chicken eggs (ECEs). N-glycan is acquired around the receptor-binding site (RBS) to help the virus evade humoral immunity by masking B-cell epitopes, but this also decreases the binding affinity of HA to receptors (an α2,3-sialogalactose moiety) on the host cell surface [

12] . To compensate for the decrease in HA activity, NA activity is often decreased by stalk deletion, resulting in reduced accessibility of NA to receptors [

13]. Clade 2.3.2.1c A/mandarin duck/Korea/K10-483/2010 (K10-483) H5N1 viruses have acquired 144N-glycan and a 20-amino-acid deletion (aa-del) in the NA stalk [

14]. An H9N2 vaccine strain, A/chicken/Korea/01310-CE20/2001 (01310), belonging to a Y439-like lineage, was established by passaging 20 times through ECEs. During passage, 01310 acquired an 18-aa-del in the NA stalk and 133N-glycan in HA [

15]. Moreover, the polymerase protein complex of influenza A virus is a trimer composed of PB2, PB1, and PA, and its activity can be modulated primarily by PB2 [

16]. The balance between polymerase activity and surface glycoprotein levels (HA and NA) is crucial for efficient viral replication and pathogenicity in mammals. Therefore, highly productive, nonmammalian pathogenic vaccine strains can be generated by optimizing the balance between HA and NA activities, as well as ensuring proper alignment with polymerase activity [

16].

The presence of universal epitopes across different subtypes of AIVs has been reported in the HA2 subunit and extracellular domain of the Matrix 2 (M2e) protein, where they play a role in providing protection against the virus [

17,

18]. Although these universal epitopes exist, there are amino acid variations, and interestingly, N-glycans that can potentially mask these epitopes are commonly present in the HA (154N-glycan) of most viruses but are rarely found in M2e. Notably, in the PR8 strain, which provides the six internal gene segments for recombinant vaccine strain development, M2e does contain an N-glycan (20N-glycan,

Table S1). Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the impact of N-glycan removal on the replication efficiency and cross-protection efficacy of vaccine strains.

Different reagents are employed for the inactivation of vaccine viruses, and the choice of an appropriate inactivation method is crucial for vaccine efficacy. Formaldehyde is a widely used inactivation reagent that works by covalently cross-linking proteins and modifying genetic material. However, cross-linking of surface protective proteins may alter the antigenic structure and reduce the accessibility of epitopes, potentially affecting the antigenicity and immunogenicity of vaccines [

19]. In contrast, binary ethylenimine (BEI) can inactivate viral genetic materials while preserving the function of viral proteins [

20].

In this study, we aimed to develop a model vaccine strain capable of neutralizing both H5N1 and H9N2 viruses and suitable for serological DIVA to differentiate major subtypes (H5N1, H5N6 and H5N8) of HP AIV infections. We generated PR8-derived recombinant H5N2 vaccine strains with different combinations of the HA gene from a clade 2.3.2.1c H5N1 HP AIV strain without the 154N-glycan, the NA gene of 01310 without N-glycans of the stalk, chimeric PR8 M2 with avian M2e and 20N-glycan deletion, and the PB2 gene from 01310. We compared their replication efficiencies, as well as their immunogenicity and antigenicity after inactivation with different reagents. Finally, we successfully obtained a model recombinant H5N2 vaccine strain that is highly productive, nonpathogenic in mammals, neutralizes both H5N1 and H9N2, and can be applied in the serological DIVA strategy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Viruses, Cells and Plasmids

The A/chicken/Korea/01310-CE20/2001 (H9N2, 01310 E20) strain, which was passaged 20 times through specific pathogen-free (SPF) ECEs, was obtained from the Laboratory of Influenza Viruses at the Animal and Plant Quarantine Agency (QIA) in Korea. The 01310-CE20 strain has been used as a vaccine strain to control H9N2 LP AIV outbreaks in Korea [

15]. The HP strain A/mandarin duck/Korea/K10-483/2010 (K10-483) was isolated from a mandarin duck that migrated to Korea in 2010. This strain was classified into clade 2.3.2.1c together with the H5N1 HP AIVs that caused the fourth poultry outbreak in Korea from 2010 to 2011 [

21]. The Hoffmann vector system was used to generate recombinant influenza viruses, which were passaged three times in 10-day-old SPF ECEs (VALO) and then used for experiments [

22]. We utilized the HA and NA genes of K10-483, the NA gene of 01310 E20, six internal genomic segments (PB2, PB1, PA, NP, M, NS) from A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1, PR8), and the PB2 gene of 01310. All the genomic segments were cloned and inserted into the pHW2000 vector. 293T and MDCK cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin‒streptomycin (Pen-Strep, Gibco). All the cell lines were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO

2 incubator.

2.2. M2e Sequence Analysis

Sequences of the M2e region from H5N1, H5N6, H5N8, and H9N2 AIVs, isolated between 2018 and 2021, were collected from the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID). A total of 627 H5N1 M2e sequences, 364 H5N6 M2e sequences, 1453 H5N8 M2e sequences, and 993 H9N2 M2e sequences and the M2e sequence of PR8 were aligned for comparative analysis. The consensus sequences for each subtype, excluding the PR8 M2e, were determined. Potential N-glycosylation sites found in the consensus sequence were removed to determine the final M2e (Av) sequence.

2.3. Recombinant Virus Generation by Reverse Genetics

PR8-derived recombinant H5N1 viruses with different combinations of the attenuated HA gene of K10-483, the NA gene of K10-483 or 01310-CE20, the PB2 genes of PR8 or 01310, and the M2e (Av) gene and PR8 M2e gene were generated via reverse genetics. The HA gene of K10-483 was attenuated by replacing its polybasic cleavage site sequence (RERRRKR/GLF) with a monobasic sequence (ASGR/GLF). The M2e protein is highly conserved in AIVs and has become a major target for the development of universal vaccines [

23,

24,

25]. However, we identified significant differences between PR8-M2e and avian-M2e, notably, a six-amino-acid discrepancy (

Table S1). Additionally, we discovered a potential N-glycosylation site at amino acid positions 20-22 in PR8 M2e, which could negatively impact vaccine immunogenicity. To incorporate a representative M2e (Av) sequence into rvH5N2-aM2e, we aligned the M2e sequence of the H5N1, H5N6, H5N8, and H9N2 subtype viruses isolated between 2018 and 2021, which pose major threats to the poultry industry, and then identified a consensus sequence (

Table S1). However, this consensus sequence contained potential N-glycosylation sites, which could shield epitopes and thereby adversely affect the immunogenicity of the vaccine [

26]. Therefore, the potential N-glycan at the asparagine at position 18 was removed. Additionally, the N-glycosylation site covering the HA2 stem region was removed, especially for rvH5N2-aM2e. The genomic constellation of the recombinant viruses is summarized in

Table 1. All recombinant viruses were generated using a 8-plasmid reverse genetics system [

22]. Briefly, 293T cells were cultured (to 1 × 10

6 cells/well in 6-well plates) and transfected with 300 ng of each plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and PLUS Reagent (Invitrogen) in a final volume of 1 ml of Opti-MEM (Gibco). After 24 hours of incubation, the transfected cells were supplemented with Opti-MEM and TPCK-treated trypsin (L-1-tosylamido-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone-treated trypsin, Sigma‒Aldrich). After an additional 24-hour incubation, 200 µL of the cell supernatant was inoculated into 10-day-old SPF ECEs, which were subsequently incubated for 3 days at 37°C. After incubation, the allantoic fluid was harvested and tested via an hemagglutination assay using 1% (v/v) chicken red blood cells (RBCs) according to the WHO Manual on Animal Influenza Diagnosis and Surveillance. Each generated recombinant virus was confirmed by RT‒PCR and Sanger sequencing as previously described [

27].

2.4. Recombinant Virus Titration in ECEs

Each recombinant virus was subjected to 10-fold serial dilution, and each dilution was inoculated into five 10-day-old SPF ECEs to measure the titer of the recombinant viruses. The presence of AIVs in the allantoic fluid was confirmed by the HA assay. The 50% infectious dose (EID

50/ml) in chicken embryos was calculated via the Spearman–Karber method [

28]

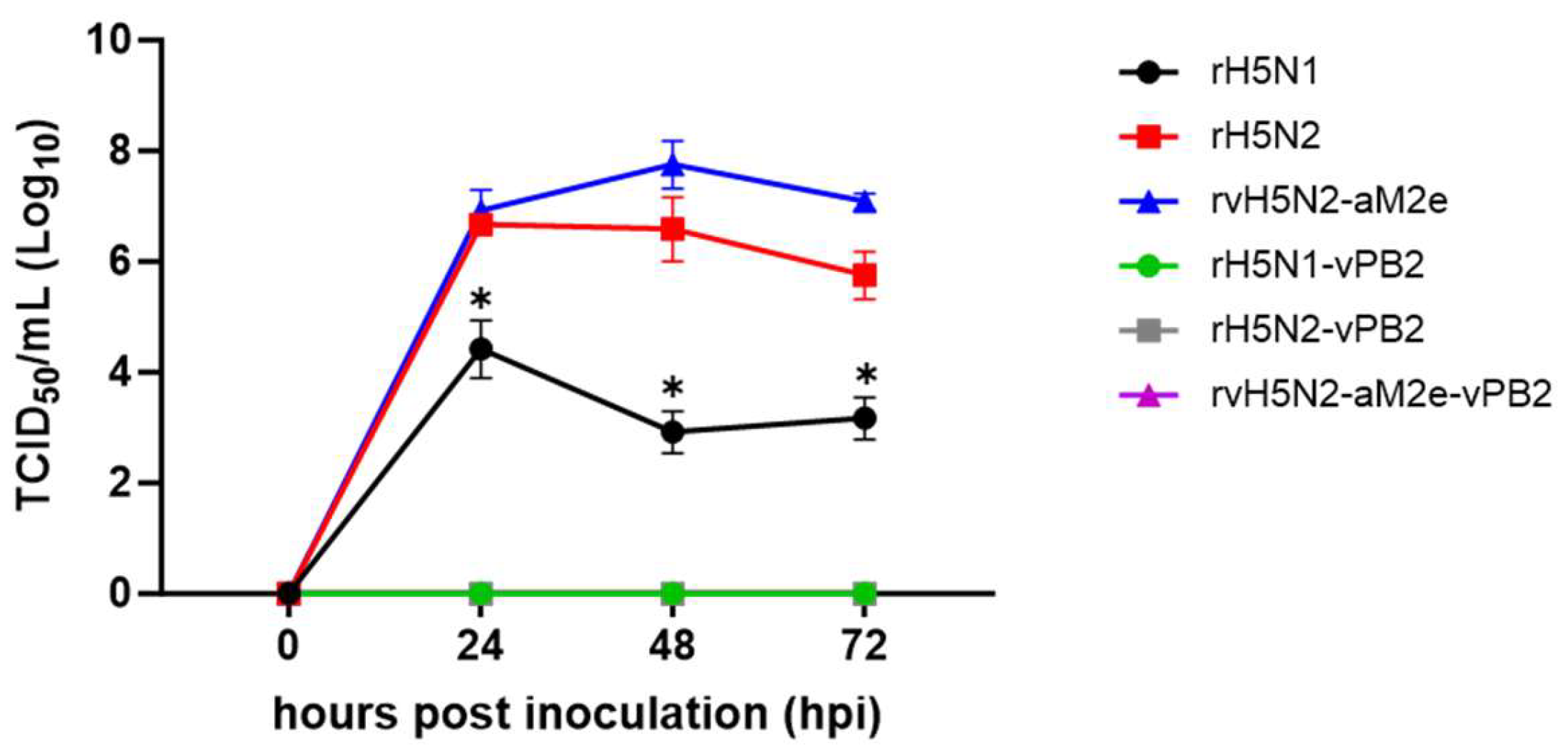

2.5. Growth Curves of Recombinant Viruses in MDCK Cells

To measure the infectivity of the recombinant viruses in mammalian cell lines, each virus was inoculated onto MDCK cells in a 12-well plate at an MOI of 0.001. After incubation for one hour at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator, the inoculum was replaced with fresh medium. The supernatants were then collected at intervals of 0, 24, 48 and 72 hours. These collected supernatants were subjected to 10-fold dilution and subsequently inoculated onto MDCK cells to determine the viral titer, which was measured as the TCID50/mL.

2.6. Virus Inactivation Using Formaldehyde or BEI

Each recombinant virus was used in undiluted allantoic fluid, with the following viral titers used for the viruses: rH5N1-vPB2 = 10

9.33 ± 0.23 EID

50/mL, rH5N2-vPB2 = 10

9.0 ± 0.35 EID

50/mL, and rvH5N2-aM2e-vPB2 = 10

9.58 ± 0.23 EID

50/mL (

Table 1). The recombinant viruses from each group were then inactivated via two different methods. For formaldehyde-mediated inactivation, 0.2% formaldehyde was applied to the viruses, which were then incubated in a 37°C incubator for overnight. Viral inactivation was confirmed by inoculating the sample into SPF ECEs. For BEI-mediated inactivation, 0.1 M BEI was mixed with the viruses, followed by a 24-hour incubation in a 37°C incubator. Inactivation was terminated by the addition of a 1 M sodium thiosulfate solution. Viral inactivation was confirmed using SPF ECEs, which is consistent with the procedures described previously. The two types of vaccines were prepared by mixing with ISA78 (SEPPIC) at a 3:7 ratio to create oil-emulsion vaccines.

2.7. Immunogenicity of H5N2 Recombinant Viruses

The procedures for animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Seoul National University (IACUC-SNU-230612-5, SNU-220412-1-2). To evaluate the immunogenicity of formaldehyde- or BEI-inactivated H5N2 recombinant viruses, five three-week-old SPF chickens were vaccinated via intramuscular (IM) injection with 0.5 mL of inactivated virus. Blood samples were collected from the wing vein at 0, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days post vaccination (DPV). Hemagglutination inhibition (HI) tests were performed according to the WHO Manual on Animal Influenza Diagnosis and Surveillance. Briefly, each serum sample was treated at 56°C for 30 minutes and diluted 2-fold with PBS, and 25 μL of each diluted sample was mixed with an equal volume of 4 hemagglutinating units (HAUs) of virus. After incubation at room temperature for 30 minutes, 25 μL of 1% (v/v) chicken red blood cells (RBCs) was added, and hemagglutination was recorded after 40 minutes.

To assess the M2e immune response and protective efficacy of live H5N2 recombinant virus inoculation, six-week-old female BALB/c mice (n=13) were intranasally administered either 104 EID50 of live virus (rH5N2 or rvH5N2-aM2e) or PBS as a negative control. Two weeks after virus inoculation, sera were collected from five mice to evaluate the M2e immune response, while the remaining mice (n=8) were challenged with 106 EID50 of SNU50-5 (A/wild duck/Korea/SNU50-5/2009(H5N1)), PR8 (A/Puerto Rico/8/1934(H1N1)), or PR8-M(Av) (PR8 virus with avian M2e). Body weight and survival rates were monitored for an additional two weeks. At three days postchallenge (dpc), three mice were sacrificed, and the lung viral titers were determined via TCID50/mL measurements.

2.8. Virus Neutralization (VN) Test

A virus neutralization (VN) assay was conducted via a previously described method with slight modifications [

29]. Heat-inactivated serum was diluted two-fold in DMEM, without the addition of FBS, in a 96-well U-plate (starting with a 32-fold dilution in the first well). The diluted serum was mixed with an equal volume of 100 TCID

50 antigen and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Then, the mixture was added to a 96-well plate containing a monolayer of MDCK cells and incubated at 37°C for 3 days. On the third day, the supernatant was harvested and mixed at a 1:1 ratio with 1% chicken RBCs. The VN titer was defined as the highest serum dilution that inhibited the hemagglutination of the RBCs.

2.9. M2e-Specific IgG Analysis by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

To assess M2e-specific IgG titers, an M2e peptide-coating ELISA was conducted. Peptides with sequences corresponding to PR8 M2e (MSLLTEVETPIRNEWGCRCNGSSD) and M2e (Av) (MSLLTEVETPTRNGWECKCSDSSD) were synthesized (BIONICS, South Korea). Both M2e peptides were coated onto a 96-well immunoplate and incubated overnight at 4°C. The following day, the plate was washed with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST). The plate was subsequently blocked with blocking buffer (PBST with 0.1% BSA) and incubated at room temperature for 2 hours. Serum samples were subjected to two-fold serial dilution in a fresh 96-well U-plate. These diluted serum samples were then transferred to the blocked plate and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. After the plates were washed, the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody was applied to all the wells, and the plate was incubated for an additional hour at room temperature. Subsequently, the HRP reaction was induced using the substrate TMB. The reaction was stopped with 0.1 M H2SO4, and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a microplate reader (TECAN, Switzerland). To evaluate the antibody responses to M2e following live virus inoculation, sera collected from mice at two weeks post inoculation were analyzed via M2e peptide-coated ELISA following the same procedure as that used for chicken sera.

2.10. NA Inhibition Test

The NA inhibition activity of the serum samples was measured using the NA-star™ Influenza Neuraminidase Inhibitor Resistance Detection Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, heat-treated serum samples collected at 3 weeks post vaccination (wpv) were serially subjected to two-fold dilutions in NA star assay buffer, starting from a 1:16 dilution up to a 1:1024 dilution. Viruses were added to the serially diluted serum samples and incubated at room temperature for 20 minutes. Then, 1:1000 diluted NA substrate was added to all the wells at 10 μL/well, and the plate was incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. Then, NA-star accelerator was added at 60 μL/well, and luminescence was measured immediately using an Infinite 200 PRO (TECAN, Switzerland). The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) against the virus was the serum dilution titer that achieved 50% inhibition of NA activity.

2.11. T-Cell Epitope Analysis and Structural Modeling

To compare the CD8+ T-cell epitopes of the HA, NA, NP, M1, and NEP proteins between the vaccine strains (rH5N2/rvH5N2-aM2e) and challenge viruses (SNU50-5, PR8) used in the mouse study, the Immune Epitope Database Analysis Resource (

http://tools.iedb.org/main/tcell/) was utilized, with the allele set to H-2-Kd. Predicted epitopes with a percentile rank below 0.5 were considered to possess high MHC affinity.

The 3D structures of the N1 protein from the rH5N1 virus and the N2 protein from the 01310 (H9N2) virus were predicted using the AlphaFold 3 model. The predicted structures were visualized in PyMOL v4.6.0. To compare the heights of the ectodomains (head and stalk) of the NA, excluding the transmembrane and cytoplasmic tail regions, the average distance between five conserved active-site amino acid (R118, R152, E276, R292, R371) in the head and the amino acid at the lowest position in the stalk was measured.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Statistical plots were generated via GraphPad Prism 9.5.1. All data are represented as mean ± SD. The replication efficacy of the recombinant viruses in embryonated eggs, NA inhibition test results and mouse lung viral titer were compared between the groups via one-way ANOVA. For comparing growth kinetics in the MDCK cell line, as well as for the HI and VN assays and ELISAs, two-way ANOVA was employed.

4. Discussion

Clade 2.3.2.1c H5N1 viruses evolved from clade 2.3.2, resulting in the accumulation of adaptive mutations over more than a decade of repeated infections in chicken flocks [

32]. These viruses caused fatal human cases in Cambodia in 2024 and have become endemic in several Asian countries [

33]. Furthermore, progeny variants of clade 2.3.2.1c, such as clades 2.3.2.1d and 2.3.2.1e, have emerged in China [

34]. As previously reported, the viral titer in ECEs of the clade 2.3.2.1c H5N1 vaccine strain generated through conventional reverse genetics using the six internal genes of PR8 was very low. However, it could be increased more than ten-fold by replacing the PR8 PB2 gene with the 01310 PB2 gene [

14]. Therefore, the continuous circulation of clade 2.3.2.1c and its progeny variants reflects the need for high-titer vaccines as well as massive, nationwide vaccination.

The unexpectedly high viral titers of rH5N2 and rvH5N2-aM2e in ECEs support the importance of the balance of HA and NA activities with each other as well as with the activity of PB2 (

Table 1). The increase in the viral titers may be attributed to differences in the enzyme activities of N1 and N2, which may cooperate with HA to affect viral replication efficiency. Most clade 2.3.2.1c H5N1 viruses also acquired the V223I mutation at the interfaces of HA trimer globular heads, which decreased the thermostability of HA [

32]. The thermostability of HA is related to acid stability, and clade 2.3.2.1c HA is predicted to change conformation for fusion at relatively high pH [

35]. For the fusion of the viral envelope and the endosomal membrane, HA must detach from the receptor to induce destabilization of the globular head trimer. The optimal pH for the enzymatic activity of most N1s is slightly lower than that for N2, and a shorter N1 may be inactive at the pH of the early endosome, potentially hindering HA release from receptors. However, N2 may perform this function more effectively than N1. Investigating how different types of NAs might influence the viral envelope and endosomal membrane fusion as the endolysosomal pH decreases would be particularly interesting [

36,

37]. Although we did not directly compare enzyme activities, the length of the NA stalk is one of the factors that influences receptor accessibility and neuraminidase activity [

38]. Both N1 of K10-483 and N2 of 01310 underwent adaptation in poultry flocks, resulting in 20- and 18-amino-acid deletions in their stalks, respectively. When the lengths of the extracellular region of these NA proteins were compared, N1 (56.4 Å) was found to be shorter than N2 (64.0 Å) (

Figure S1). Stalk amino acid deletions may reduce NA activity, and shorter NAs may have a lower probability of cleaving host cell surface receptors for rapid viral escape. The reduced activity of N1 could lead to an imbalance with the stronger activities of HA and PB2, resulting in decreased replication efficiency of rH5N1. In this context, the relatively low viral titer of rH5N2-vPB2 can be attributed to the relatively low activity of 01310 PB2 compared with that of PR8 PB2, leading to an imbalance [

39]. The effect of lower PB2 activity may be balanced somehow by combined mutations in HA (TGT) and M2e (aM2e) that increase the viral replication efficiency of rvH5N2-aM2e-vPB2. The TGT mutation at the 154N-glycosylation site is a rare mutation that affected virus replication efficiency much less than many other mutations did in our previous study [

40]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the M2 protein significantly influences the viral budding capacity and contributes to viral assembly through M1 protein recruitment to the cell membrane [

41,

42]. To date, experimental evidence supporting the effect of M2e modification on viral replication efficiency has not been reported, but the delayed mortality of PR8-M(Av) (mean death time, 153.6 hr) days) compared with that of PR8 (mean death time, 129.6 hr) may suggest that M2e modification may decrease viral fitness (

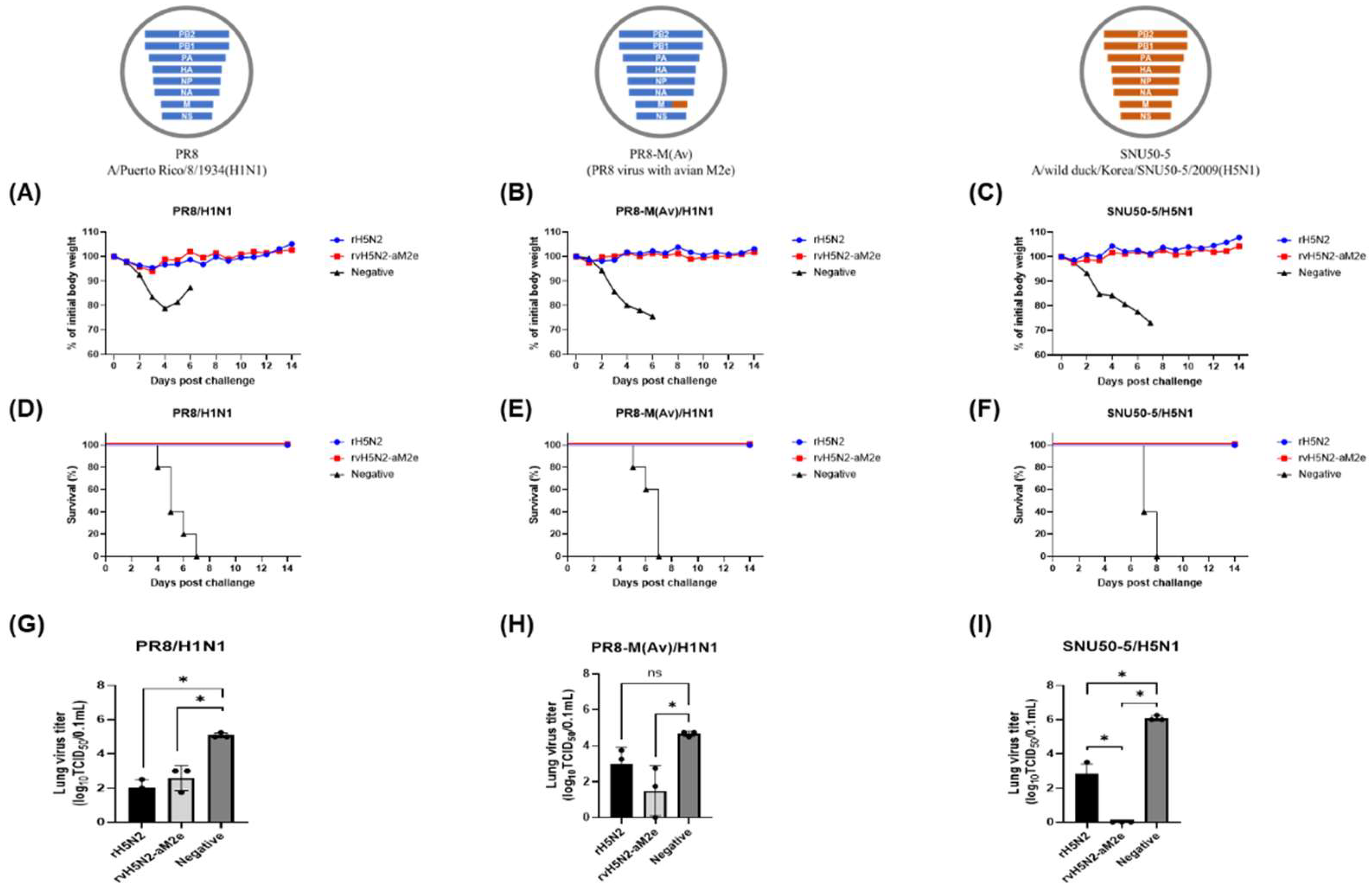

Figure 6).

The PR8 PB2 gene contains multiple mammalian pathogenicity-related mutations, including the most potent E627K mutation, and intentional or accidental generation of artificial reassortants of AIV strains possessing PR8 PB2 should be avoided [

39]. In contrast to PR8 PB2-possessing recombinant strains, all the 01310 PB2-possessing recombinant strains did not replicate in MDCK cells. The effect of N2 on viral replication efficiency was also apparent in MDCK cells, and rH5N2 and rvH5N2-aM2e presented significantly higher viral titers than did rH5N1 (

Figure 1). Fortunately, rH5N1 replicated in the lungs of BALB/c mice without body weight loss in our previous study, and rH5N2 and rvH5N2-aM2e did not cause body weight loss after inoculation at 10

4 EID

50/mouse in this study [

14]. However, all the G1-, Y280- and Y439-like H9N2 recombinant vaccine strains possessing PR8 PB2 caused severe body weight loss in BALB/c mice [

43,

44,

45]. Therefore, the biosafety of vaccine strains and the biosecurity of vaccine production lines for veterinary use need to be guaranteed, especially when they represent nonvaccine subtypes in humans.

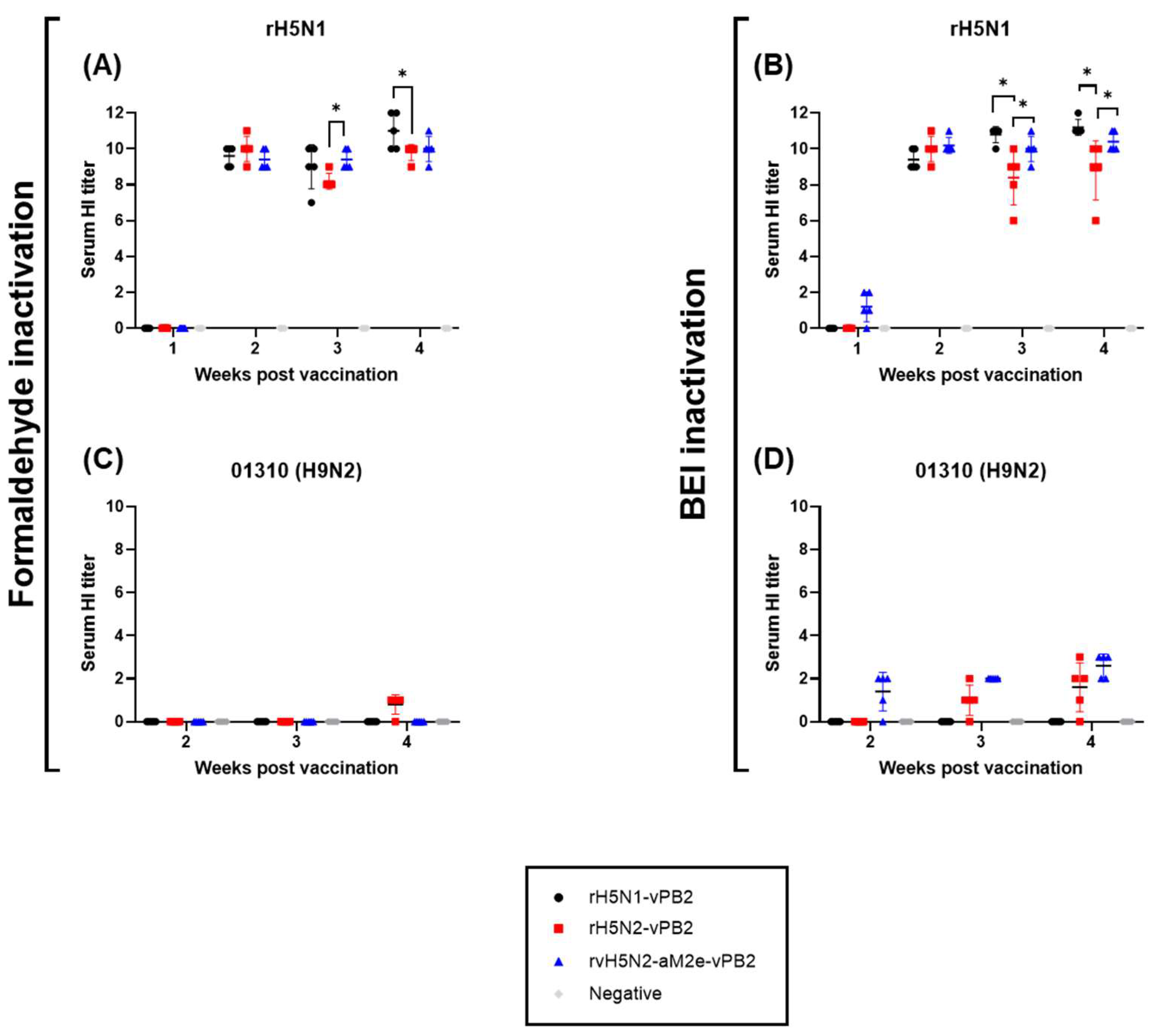

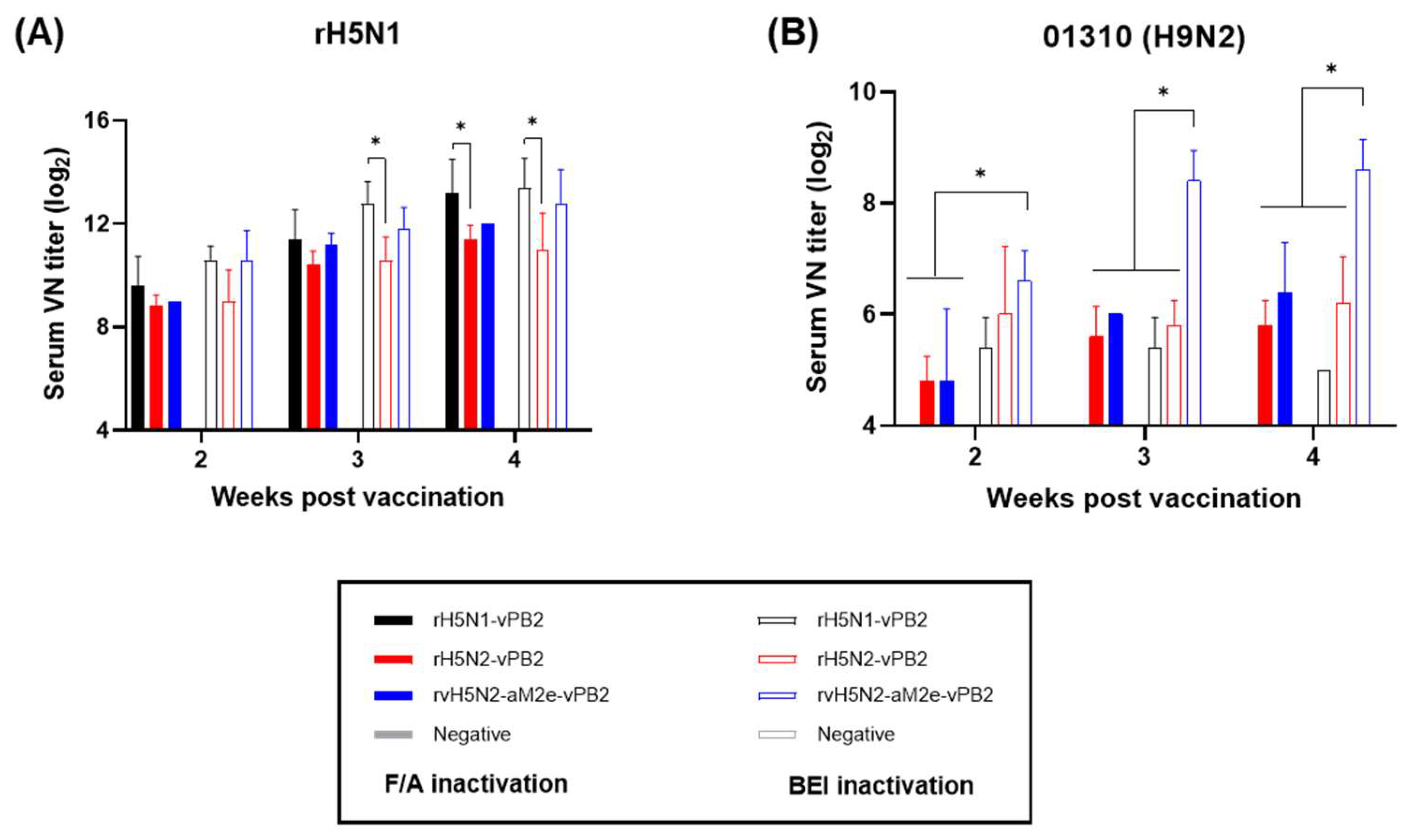

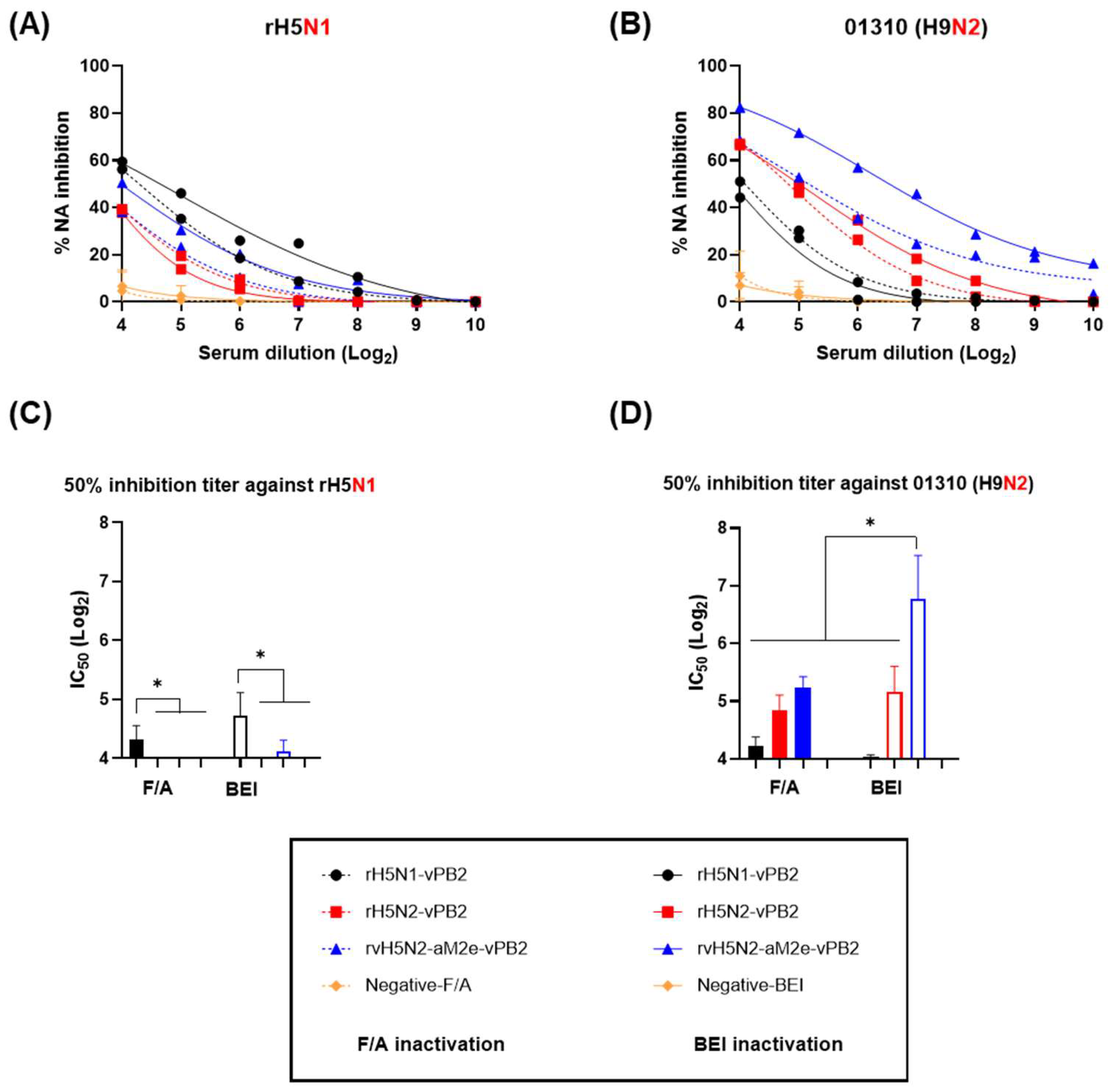

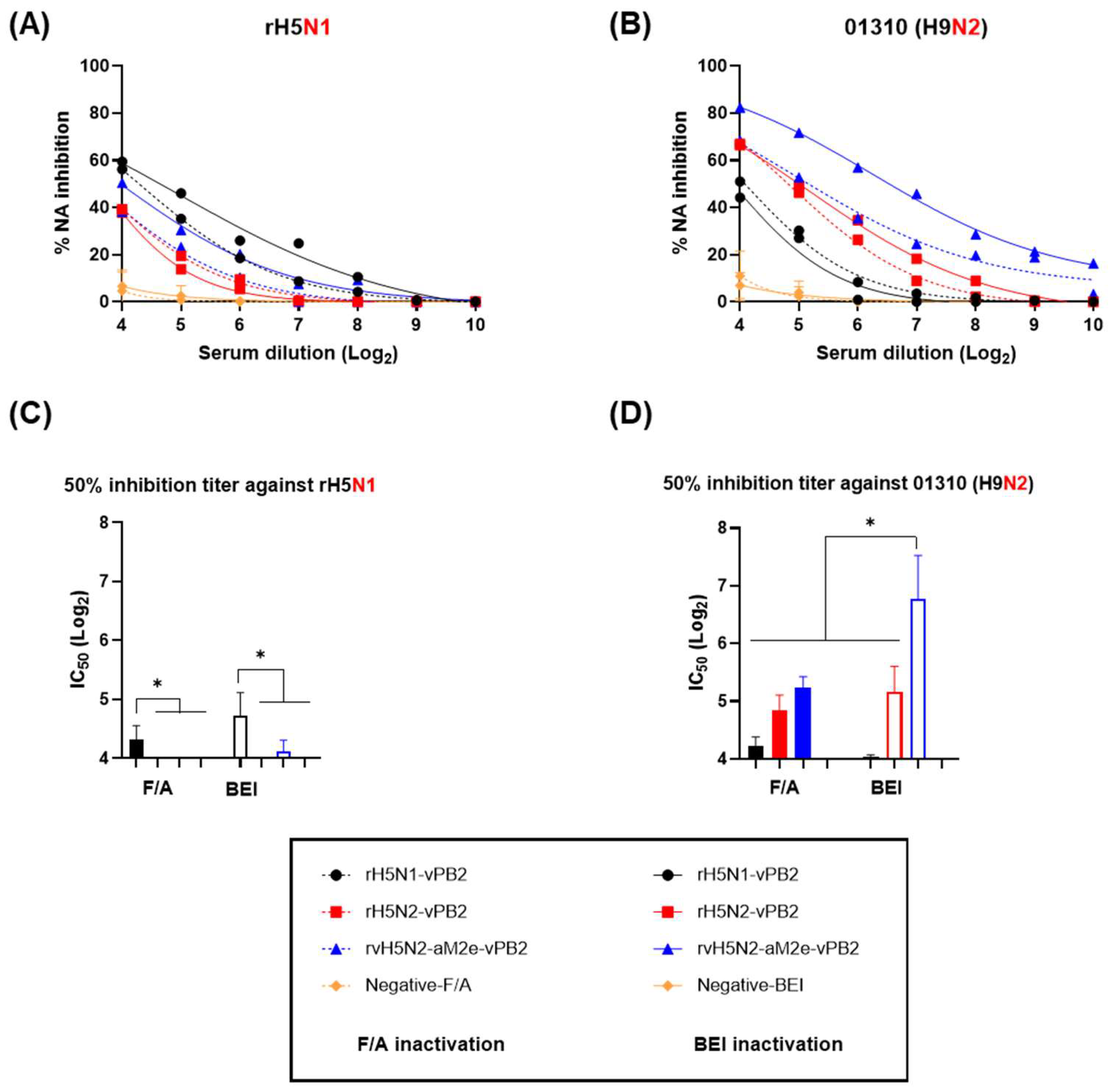

The immunogenicities of rH5N1-vPB2, rH5N2-vPB2 and rvH5N2-aM2e-vPB2 were high enough to induce very high HI and VN titers against rH5N1 irrespective of the inactivation reagents used, but BEI-inactivated rvH5N2-aM2e-vPB2 was best because it induced significantly higher VN and NI antibody levels against 01310 (H9N2) than the other vaccines (

Figure 3 and 4). In this study, we aimed to evaluate the impact of N-glycan removal from the HA, NA stalk, and M2e of rvH5N2-aM2e-vPB2 on enhancing immunogenicity. While some effects of N-glycan removal were observed, our results were not fully explained by these effects. The differences in immunogenicity between rH5N2-vPB2 and rvH5N2-aM2e-vPB2 for the homologous antigen (rH5N1) could not be attributed to the effects of N-glycan removal due to differences in the viral titers administered. Similarly, the differences in immunogenicity between rH5N1-vPB2 and rvH5N2-aM2e-vPB2 against rH5N1 could not be explained by the effects of N-glycan removal, likely due to the overall high levels of immunogenicity of both vaccines. For each homologous NA antigen, the lower NI antibody level of the BEI-inactivated rH5N1-vPB2 vaccine than of the BEI-inactivated rvH5N2-aM2e-vPB2 vaccine supports the finding that a shorter N1, compared with N2, has lower immunogenicity (

Figure S1). Moreover, higher NI antibody levels against homologous NA subtypes may be useful in serological DIVA strategy to diagnose unvaccinated H5N1 HPAIV infection (

Figure 4C and D).

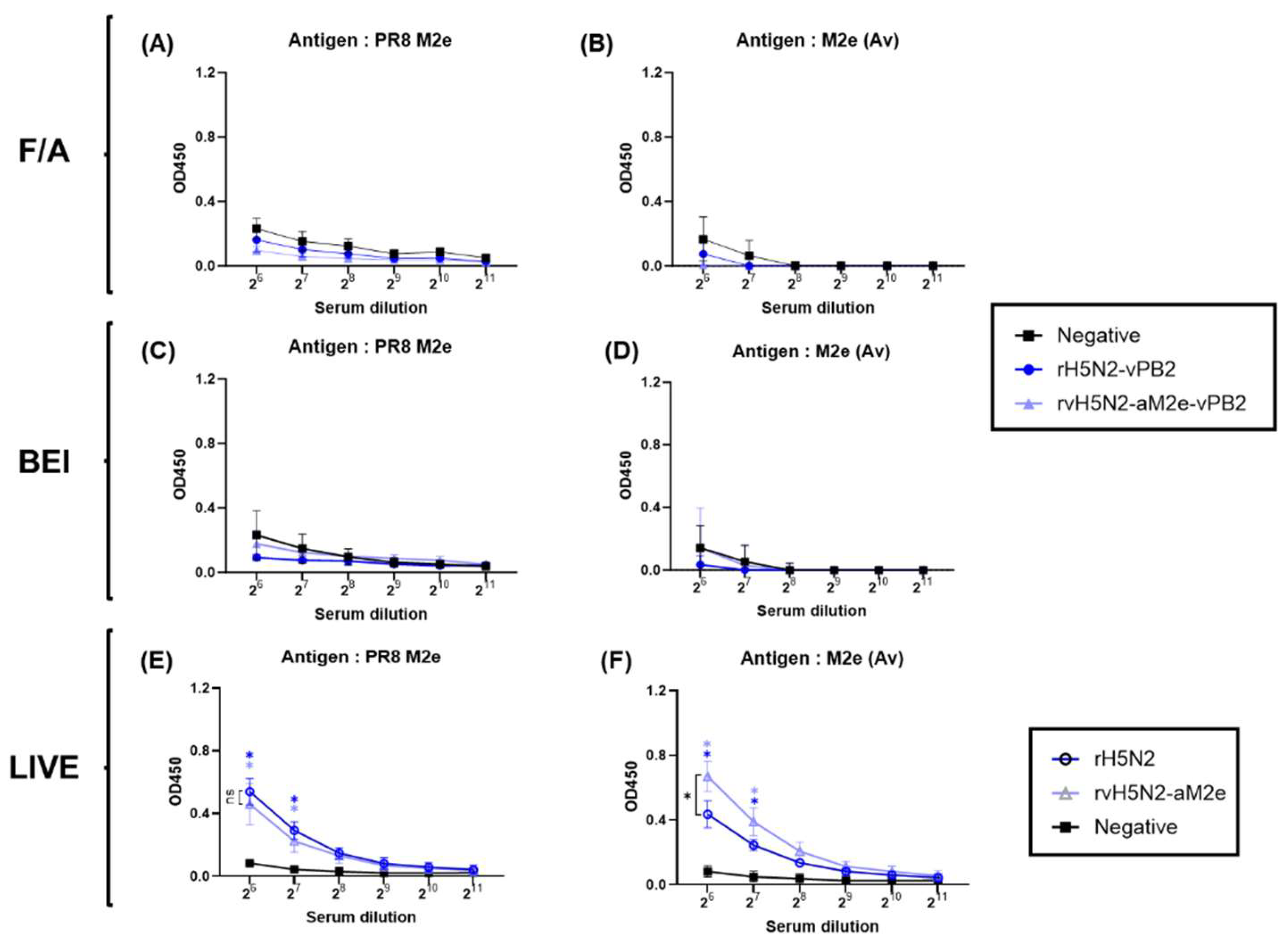

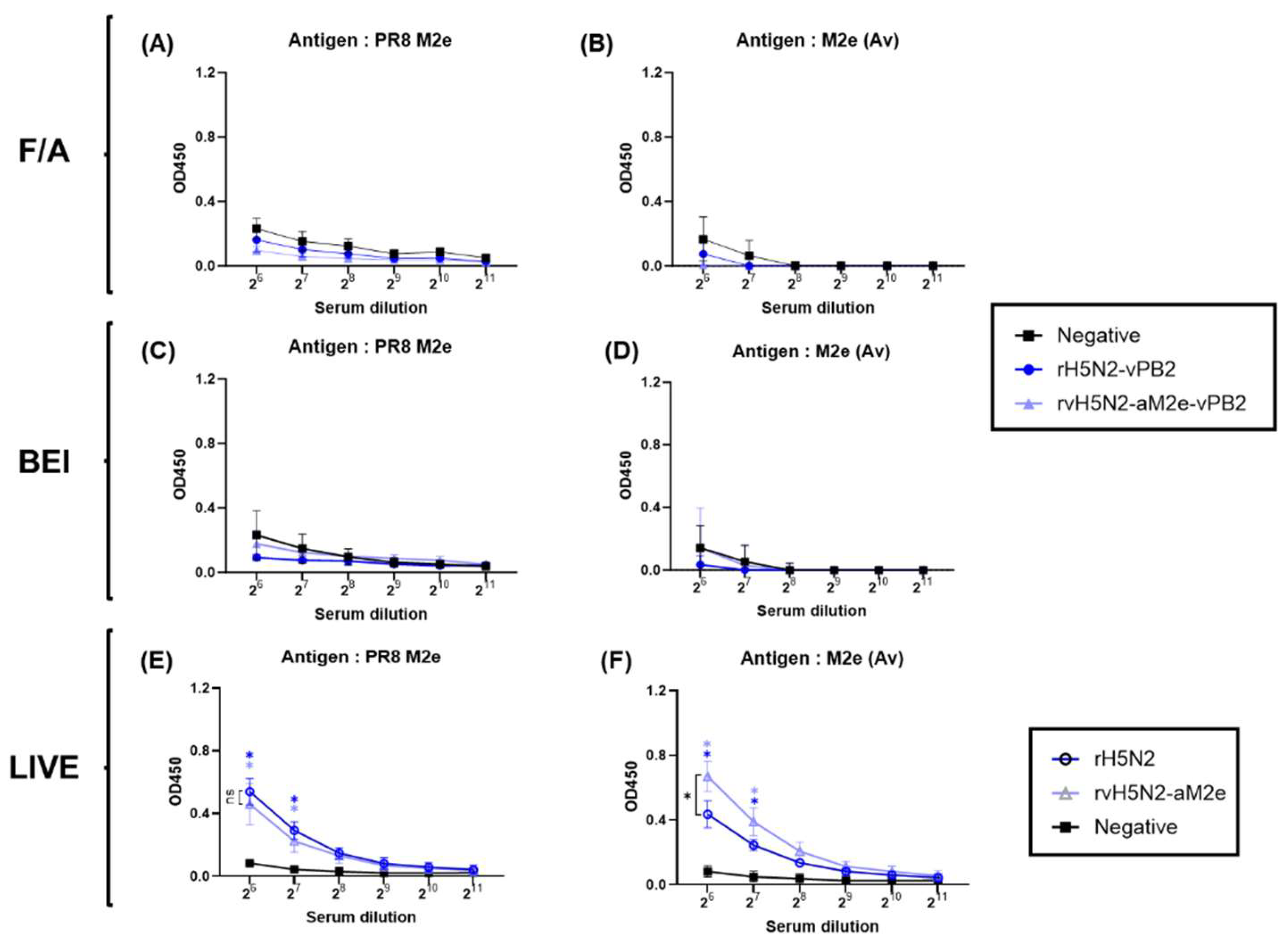

Anti-M2e antibody production was not induced by inactivated oil emulsion vaccines but was instead induced by live vaccines. The M2 protein is abundantly expressed on the surface of infected cells but is only sparsely incorporated into virions [

46]. Therefore, the no immunogenicity of M2e on virions is attributed to its low copy number and limited surface exposure, a phenomenon that can be overcome by live vaccines, as demonstrated in this study. This finding may also be useful for verifying the M2e-based serological DIVA strategy. The M2e epitopes recognized by monoclonal antibodies are composed of four amino acid residues: E6, P10, I11 and W15. In this epitope, only one amino acid of PR8 M2e (T11) differs from that of M2e (Av) (I11) [

47]. However, M2e(Av) contains additional mutations, including E14G, G16E, R18K, N20S and G21D, which differ from the residues in PR8 M2e. Despite these multiple amino acid differences, the mouse anti-serum samples collected from the live rH5N2- and rvH5N2-aM2e-vaccinated groups presented similar OD values in the PR8 M2e peptide-ELISA (

Figure 5E), suggesting that mutations other than I11T are unlikely to affect antibody binding. However, the anti-serum samples from the rvH5N2-aM2e-vaccinated group presented significantly greater OD values than did those from the rH5N2 group according to the M2e(Av) peptide-ELISA (

Figure 5F). The live rvH5N2-aM2e vaccine may exhibited enhanced immunogenicity due to the reduction in N-glycan levels in HA, NA and M2e, which subsequently increased binding affinity and facilitated the generation of more specific antibodies against the M2e(Av) peptide within just 14 days. Furthermore, the higher M2e antibody titers induced by rvH5N2-aM2e may have compensated for the lower binding affinity to the PR8 M2e peptide, resulting in OD values comparable to those of rH5N2 against PR8 M2e. The live rH5N2 and rvH5N2-M2e vaccines provided complete protection against heterosubtypic PR8 and PR8-M(Av) strains, which possess nearly identical internal genes, as did the SNU50-5 strain, which has different internal genes. The protective efficacy of the live vaccines may be attributed mainly to common CD8+ T-cell epitopes related to cellular immunity (

Table 2 and

Table S2) [

31,

48]. However, the significantly lower lung viral titer in the rvH5N2-aM2e-vaccinated group than in the rH5N2 group cannot be explained solely by cellular immunity, as they share identical CD8+ T-cell epitopes. Additionally, while antibodies against M2e lack neutralizing activity compared to antibodies against HA, they can bind to M2e expressed on virus-infected host cells and inhibit viral budding through antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), thereby reducing viral replication [

49,

50]. Therefore, the increased levels of anti-M2e(Av) antibodies may contribute to the reduced lung viral titers of both PR8-M(Av) and SNU50-5 (

Figure 6H, 6I).

In conclusion, we succeeded in generating a highly productive, mammalian nonpathogenic and dual-protective H5N2 vaccine strain against H5Nx and H9N2 AIVs and determined the proper inactivation reagent. The dual-protective H5N2 vaccine strain may be useful for reducing the antigen volume for avian influenza vaccines and may facilitate the development of other vaccines, such as commercial poultry multivalent oil emulsion vaccines against Newcastle disease, infectious bronchitis, egg drop syndrome, metapneumovirus infection and avian influenza. If the H5N2 vaccine efficacy is verified in vaccine challenge experiments in chickens, our results may promote the development of other H5N2 vaccine strains covering clade 2.3.4.4b H5Nx and Y280-like H9N2 or G1-like H9N2 vaccine strains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.-H.S. and H.-J.K.; methodology, J.-H.S., S.-E.S., S.-H.A. and C.-Y.L.; software, J.-H.S., S.-E.S. and H.-J.K.; validation, J.-H.S., S.-E.S., H.-J.K. and K.-S.C.; formal analysis, J.-H.S., S.-E.S., H.-W.K. and S.-H.A.; investigation, J.-H.S., S.-E.S., H.-W.K., S.-H.A. and C.-Y.L.; resources, J.-H.S., H.-W.K., S.-H.A. and C.-Y.L.; data curation, J.-H.S. and H.-J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-H.S. and H.-J.K.; writing—review and editing, J.-H.S., H.-J.K. and K.-S.C.; visualization, J.-H.S., and H.-J.K.; supervision, H.-J.K. and K.-S.C.; project administration, H.-J.K. and K.-S.C.; funding acquisition, H.-J.K. and K.-S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the replication efficiencies of the recombinant viruses in MDCK cells. MDCK cells were inoculated with recombinant H5N1 or H5N2 virus at an MOI of 0.001. After 1 h of incubation, the inoculum was replaced with fresh medium, and the supernatant was obtained at each time point (0, 24, 48, and 72 h). The viral titer was measured as the TCID50/ml in MDCK cells, and the results are presented as the means ± SDs of triplicate experiments. Statistical significance was analyzed by two-way ANOVA. The asterisk represents a significant difference between rH5N1 and the other groups (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the replication efficiencies of the recombinant viruses in MDCK cells. MDCK cells were inoculated with recombinant H5N1 or H5N2 virus at an MOI of 0.001. After 1 h of incubation, the inoculum was replaced with fresh medium, and the supernatant was obtained at each time point (0, 24, 48, and 72 h). The viral titer was measured as the TCID50/ml in MDCK cells, and the results are presented as the means ± SDs of triplicate experiments. Statistical significance was analyzed by two-way ANOVA. The asterisk represents a significant difference between rH5N1 and the other groups (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Comparison of serum HI titers induced by recombinant virus vaccines inactivated by formaldehyde or binary ethylenimine (BEI). Comparison of HI titers at 1–4 weeks post vaccination. Serum samples were collected from SPF chickens (n=5). (A), (C) HI antibody responses against rH5N1 or 01310 (H9N2) induced by vaccines inactivated with formaldehyde. (B), (D) HI antibody responses against rH5N1 or 01310 (H9N2) induced by vaccines inactivated with BEI. Data are represented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed via two-way ANOVA, and the results are denoted by asterisks (*p <0.01).

Figure 2.

Comparison of serum HI titers induced by recombinant virus vaccines inactivated by formaldehyde or binary ethylenimine (BEI). Comparison of HI titers at 1–4 weeks post vaccination. Serum samples were collected from SPF chickens (n=5). (A), (C) HI antibody responses against rH5N1 or 01310 (H9N2) induced by vaccines inactivated with formaldehyde. (B), (D) HI antibody responses against rH5N1 or 01310 (H9N2) induced by vaccines inactivated with BEI. Data are represented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed via two-way ANOVA, and the results are denoted by asterisks (*p <0.01).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the serum VN titers induced by recombinant virus vaccines inactivated by formaldehyde or binary ethylenimine (BEI). Serum samples (n=5) collected at 2, 3, and 4 weeks post vaccination were utilized to conduct virus neutralization (VN) tests. (A) VN antibody responses against rH5N1 induced by vaccines inactivated with either formaldehyde or BEI. (B) VN antibody responses against 01310 (H9N2) induced by vaccines inactivated with either formaldehyde or BEI. We have distinguished between the two vaccine groups in the bar graphs; the vaccines inactivated with formaldehyde are represented by bars filled with color, whereas those inactivated with BEI are depicted by bars that are outlined but not filled. Data are represented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed via two-way ANOVA, and the results are denoted by asterisks (*p <0.01).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the serum VN titers induced by recombinant virus vaccines inactivated by formaldehyde or binary ethylenimine (BEI). Serum samples (n=5) collected at 2, 3, and 4 weeks post vaccination were utilized to conduct virus neutralization (VN) tests. (A) VN antibody responses against rH5N1 induced by vaccines inactivated with either formaldehyde or BEI. (B) VN antibody responses against 01310 (H9N2) induced by vaccines inactivated with either formaldehyde or BEI. We have distinguished between the two vaccine groups in the bar graphs; the vaccines inactivated with formaldehyde are represented by bars filled with color, whereas those inactivated with BEI are depicted by bars that are outlined but not filled. Data are represented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed via two-way ANOVA, and the results are denoted by asterisks (*p <0.01).

Figure 4.

Comparison of serum NI titers induced by recombinant virus vaccines inactivated by formaldehyde or binary ethylenimine (BEI). To compare the immunogenicity against NA, the neuraminidase inhibition (NI) assay was conducted using serum samples collected at week 3 post vaccination. The NA activity of the virus alone was set as 100%, and the relative reduction in NA activity due to the serum was expressed as a percentage of NA inhibition. (A) NA inhibition curves for each serum sample against rH5N1. (B) NA inhibition curves for each serum sample against 01310 (H9N2). The curves for the vaccine groups inactivated with formaldehyde are shown as dashed lines, and those for the BEI-inactivated vaccine groups are shown as solid lines. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) against the (C) rH5N1 or (D) 01310 (H9N2) is represented as the serum dilution titer that achieved 50% inhibition of NA activity. IC50 are represented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed via one-way ANOVA, and the results are denoted by asterisks (*p <0.05).

Figure 4.

Comparison of serum NI titers induced by recombinant virus vaccines inactivated by formaldehyde or binary ethylenimine (BEI). To compare the immunogenicity against NA, the neuraminidase inhibition (NI) assay was conducted using serum samples collected at week 3 post vaccination. The NA activity of the virus alone was set as 100%, and the relative reduction in NA activity due to the serum was expressed as a percentage of NA inhibition. (A) NA inhibition curves for each serum sample against rH5N1. (B) NA inhibition curves for each serum sample against 01310 (H9N2). The curves for the vaccine groups inactivated with formaldehyde are shown as dashed lines, and those for the BEI-inactivated vaccine groups are shown as solid lines. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) against the (C) rH5N1 or (D) 01310 (H9N2) is represented as the serum dilution titer that achieved 50% inhibition of NA activity. IC50 are represented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed via one-way ANOVA, and the results are denoted by asterisks (*p <0.05).

Figure 5.

Comparison of anti-M2e antibody levels induced by inactivated and live recombinant virus vaccines. Three weeks after inactivated vaccine administration, serum samples collected from SPF chickens were used to evaluate the antibody responses against two distinct peptides, PR8 M2e and M2e (Av) (avian M2e), via ELISA. (A), (B) IgG responses against M2e from vaccines inactivated with formaldehyde (F/A). (C), (D) IgG responses against M2e from vaccines inactivated with BEI. (E), (F) Antibody responses to M2e in mouse sera collected after inoculation with live viruses. Six-week-old female BALB/c mice (n=5) were inoculated with 104 EID50 of two live viruses (rH5N2 and rvH5N2-aM2e) or a negative control (PBS). Two weeks post inoculation, we specifically evaluated the IgG responses against PR8 M2e and M2e (Av) (avian M2e) via ELISA. Data are represented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed by two-way ANOVA and is denoted by asterisks (*p <0.001). The black asterisks indicate significant differences between the two vaccines, whereas the blue and light-blue asterisks represent significant differences between the vaccines and the negative control.

Figure 5.

Comparison of anti-M2e antibody levels induced by inactivated and live recombinant virus vaccines. Three weeks after inactivated vaccine administration, serum samples collected from SPF chickens were used to evaluate the antibody responses against two distinct peptides, PR8 M2e and M2e (Av) (avian M2e), via ELISA. (A), (B) IgG responses against M2e from vaccines inactivated with formaldehyde (F/A). (C), (D) IgG responses against M2e from vaccines inactivated with BEI. (E), (F) Antibody responses to M2e in mouse sera collected after inoculation with live viruses. Six-week-old female BALB/c mice (n=5) were inoculated with 104 EID50 of two live viruses (rH5N2 and rvH5N2-aM2e) or a negative control (PBS). Two weeks post inoculation, we specifically evaluated the IgG responses against PR8 M2e and M2e (Av) (avian M2e) via ELISA. Data are represented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was analyzed by two-way ANOVA and is denoted by asterisks (*p <0.001). The black asterisks indicate significant differences between the two vaccines, whereas the blue and light-blue asterisks represent significant differences between the vaccines and the negative control.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of weight changes, survival rates, and lung viral titers in mice inoculated with rH5N2 and challenged with multiple viruses Five 6-week-old female BALB/c mice, inoculated with 104 EID50 of two live viruses (rH5N2, rvH5N2-aM2e) or PBS (negative), were intranasally challenged with 106 EID50 of the SNU50-5 (A/wild duck/Korea/SNU50-5/2009 (H5N1)), PR8 (A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1)), or PR8-M (Av) (PR8 virus with avian M2e) virus at 2 weeks after inoculation. Body weight changes (A-C) and survival rates (D-F) were monitored for 2 weeks after challenge. Three days post challenge, the mice (n=3) were sacrificed, and the lung viral titer (G-I) was determined. Lung viral titers are represented as mean ± SD and analyzed via one-way ANOVA (*p<0.05).

Figure 6.

Evaluation of weight changes, survival rates, and lung viral titers in mice inoculated with rH5N2 and challenged with multiple viruses Five 6-week-old female BALB/c mice, inoculated with 104 EID50 of two live viruses (rH5N2, rvH5N2-aM2e) or PBS (negative), were intranasally challenged with 106 EID50 of the SNU50-5 (A/wild duck/Korea/SNU50-5/2009 (H5N1)), PR8 (A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1)), or PR8-M (Av) (PR8 virus with avian M2e) virus at 2 weeks after inoculation. Body weight changes (A-C) and survival rates (D-F) were monitored for 2 weeks after challenge. Three days post challenge, the mice (n=3) were sacrificed, and the lung viral titer (G-I) was determined. Lung viral titers are represented as mean ± SD and analyzed via one-way ANOVA (*p<0.05).

Table 1.

Genome constellation and replication efficiency of the recombinant virus used in this study.

Table 1.

Genome constellation and replication efficiency of the recombinant virus used in this study.

| Recombinant virus |

HA |

NA |

PB2 |

M |

PB1 |

PA |

NP |

NS |

EID50/mla

|

| rH5N1 |

K10-483/ASGR†

|

K10-483 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

8.25 ± 0.47 |

| rH5N1-vPB2 |

K10-483/ASGR†

|

K10-483 |

01310 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

9.33 ± 0.23*

|

| rH5N2 |

K10-483/ASGR†

|

01310 E20 #

|

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

9.75 ± 0.4*

|

| rH5N2-vPB2 |

K10-483/ASGR†

|

01310 E20 |

01310 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

9.0 ± 0.35 |

| rvH5N2-aM2e |

K10-483/ASGR† /TGT‡

|

01310 E20 |

PR8 |

PR8 (aM2e) §

|

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

9.83 ± 0.31*

|

| rvH5N2-aM2e-vPB2 |

K10-483/ASGR† /TGT‡

|

01310 E20 |

01310 |

PR8 (aM2e) §

|

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

PR8 |

9.58 ± 0.23*

|

Table 2.

Numbers of predicted CD8+ T-cell epitopes shared by vaccine strains and challenge strains.

Table 2.

Numbers of predicted CD8+ T-cell epitopes shared by vaccine strains and challenge strains.

| Matching |

Number of identical predicted CD8+ T-cell epitopes |

| HA |

NA |

NP |

M1 |

NEP |

Total |

| PR8 vs. vaccinesa

|

4 |

0 |

6 |

4 |

3 |

17 |

| SNU50-5 vs. vaccines |

9 |

0 |

4 |

3 |

1 |

17 |