1. Introduction

During plant growth and development, auxin is involved at nearly every stage, from seed germination to aging and death. In addition to its direct involvement in plant physiology and development, auxin regulates gene transcription and is associated with changes in auxin synthesis and transport, and gene expression [

1]. The auxin synthesis and transport pathway is an extremely complex system that plays a crucial role in plant growth and development and their responses to stress [

2,

3]. However, current research on the regulation of plant roots through signaling pathways remains incomplete.

The citrus fruit, renowned for its distinctive flavor and abundant nutritional content, is extensively cultivated in 140 countries worldwide, making it the most widely produced fruit globally [

4]. However, soil erosion leads to the loss of organic matter, which in turn reduces the water and nutrient retention capacity of the soil, thus adversely affecting citrus production [

5]. Therefore, understanding the effects of auxin on citrus roots is crucial to enhancing the mineral element absorption level and stress resistance of citrus plants.

In general, roots are mainly divided into two types: primary roots formed during embryo development and secondary roots formed after embryo development [

6]. These secondary roots include lateral roots (LRs), which branch from the main root, and adventitial roots (ARs), which develop on non-root tissues such as hypocotyls, stems, and leaves [

7]. Auxin, as the main plant hormone, plays an important role in root development. Its ability to drive root growth and development in response to related genes regulatory networks has been well characterized [

8].

Auxin synthesis genes, as well as input and output vectors, play an important role in auxin signal transmission. The regulation of the plant-root structure mainly depends on the active auxin-synthesizing genes

TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASE RELATED (

TAR) and

YUCCA (

YUC) in the apex, which induce cells to produce auxin through specific signaling pathways [

9,

10].

AUX1 plays an important role in regulating the asymmetric distribution of auxin in root tips, especially in synergistic action with

LIKE AUX3 (

LAX3) to regulate plant auxin levels [

11,

12]. The directed flow of auxin between cells is closely related to PIN efflux transporters. In the

PIN gene family,

PIN1 is a target regulating auxin action, while

PIN3 is an auxin response factor in ARF7-mediated lateral root development [

12,

13]. In addition, SWI/SNF chromatin also promotes root stem cell niche formation by targeting

PIN4 [

13]. As a novel vector, the ABCB protein family plays a regulatory role in maintaining auxin levels during plant tissue mitosis [

14].

Mineral nutrients are selectively absorbed through the root system to regulate plant growth and development [

15]. Mineral elements play a variety of important roles in plants. For example, phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) regulate the sugar metabolism pathway of the plant, while magnesium (Mg) influences photosynthesis and respiration [

16,

17]. It is worth noting that zinc (Zn) has a very important relationship with the synthesis and transport of auxin, as it is involved in the synthesis of indole acetic acid [

18].

Research on auxin transport genes is extensive, but most studies focus narrowly on specific gene families, lacking a comprehensive analysis of all gene functions. Therefore, exogenous auxin and auxin inhibitor treatments were applied to the test materials in this study. Auxin synthesis genes, input vectors, and output vectors were detected to understand the effects of auxin on citrus root signal transduction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Growth Conditions

In this study, trifoliate orange seeds purchased from the experimental base of Wuhan Forest Fruit Promotion Station were selected as experimental materials. First, the river sand used for planting materials was washed three times with tap water and pure water, and then sterilized using a high-temperature autoclave to ensure cleanliness. Then, full and consistent seeds were selected, soaked, and disinfected with 75% (V/V) ethanol for 15 minutes, and washed 4–5 times with sterile water. After disinfection, the seeds were placed in a sterilized tray and placed in a dark incubator at 28 °C for germination. When the germinated seeds were 1 cm in length, they were sown in round pots (Height × Diameter = 30 × 20 cm) filled with sand and placed in a greenhouse.

The transplanted potted seedlings were cultured under 16 hours of light (28 °C) and 8 hours of darkness (22 °C). Nutrient solution was applied from the day of transplantation and the seedlings were watered every 3 days with a dosage of 100 mL each time. After the growth of three true leaves, the treatment began. All seedlings were irrigated with full Hoagland solution containing the corresponding growth regulators (100 mL) once every 3 days.

The basic culture Hoagland solution was composed of the following: 6.00 mM KNO3, 4.00 mM Ca (NO3)2·4H2O, 1.00 mM NH4H2PO4, 2.00 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 9.40 μM MnCl2·4H2O, 0.34 μM CuSO4·3H2O, 0.74 μM ZnSO4·7H2O, 48.00 μM H3BO3, 0.14 μM H2MoO4, and 50.00 mM EDTA-Fe, at 5.84 - 6.02 pH.

2.2. Experiment Design

The seedlings were treated with growth regulators (Shanghai Yuanye Biological Technology Co., Ltd., China) in three different ways: the control group (CK), 1.0 µmol•L

-1 IBA and 50.0 µmol•L

-1 2-NOA. Four pots were treated, each containing 10 seeds, and the process was repeated three times. The configuration of growth regulators was based on Zhang et al. [

30]. After 10 treatments, one broken cultivation basin was selected for each treatment. The cultivation substrate was stripped away, and the fine sand on the root surface was washed with water to determine the root morphology. After 15 treatments, the same method was used to remove the test material for subsequent analysis.

2.3. Study of Root Morphology

After 10 treatments of the transplanted test material, three seedlings with relatively consistent growth were selected from the pot seedlings to measure the length of main and lateral roots, the diameter of the main roots, and the number of lateral roots. Each index was measured three times.

2.4. Mineral Nutrient Content Analysis

The test materials of the aboveground and underground parts of each treatment were packaged and dried in an oven at 105 °C to constant weight (about 48 h). After crushing, 0.5 g of test materials was ground into a powder with liquid nitrogen. After weighing, 0.2 g of the sample was placed into a muffle furnace (500 °C) for ashing for 10 h, then removed and dissolved with 0.1 mol•L

-1 HCl. The dissolved solution was sent to the Institute of Soil Science, Nanjing, Chinese Academy of Sciences, where the contents of phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, iron, cuprum, zinc, boron, and other mineral nutrients were determined using an atomic absorption spectrometer (SPECTR AA220, Varian Co., USA). The determination method followed that of Borah et al. [

19]. The total nitrogen content was determined using a plasma emission spectrometer (ICP Spectrometer, Model: IRIS Advantage, USA) and analyzed following Branko’s method [

20].

2.5. Root Auxin Content

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) were used to determine the auxin content in the lateral root tip (0-0.5 cm from the root tip), the root hair area (2-3 cm from the root tip), and the epidermis and middle column of the main root hair area (4-5 cm from the root tip). The relevant test materials from each treatment were collected, frozen, and stored in dry ice. These samples were sent to the Engineering Research Center of the Ministry of Education of Plant Growth Regulators, China Agricultural University, for IAA determination. Each treatment was repeated three times, and the determination followed Dang Wei’s method [

21].

2.6. Analysis of Gene Expression

Primer design and synthesis: Gene primers were designed using Primer 5, and the housekeeping gene

β-actin was selected as the internal reference gene to amplify with other target genes and correct differences in their relative expression levels across each sample (

Table 1, [

23]). The primers were synthesized by BGI Co., LTD. Before use, the primers were centrifuged at 10000 xg at room temperature for 1 min. RNase-free H

2O was added according to the corresponding concentration of the respective primers, diluted to 10 μmol L

-1, and the solution was stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C after gentle mixing.

RNA extraction: Root segments 0-1 cm and 2-3 cm away from the lateral root tip were frozen in liquid nitrogen for 1 min and then stored in an ultra-low temperature refrigerator at -80 °C for total RNA extraction. The extraction method followed the product manual of the kit.

Synthesis of first strand cDNA: cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript@RT reagent Kit(TaKaRa, Japan) kit, and gDNA was removed using the gDNA Eraser in the kit

Fluorescence quantitative PCR: The relative expression levels of each gene in each sample were determined using the SYBRGreenI incorporation method on a Q7 real-time quantitative PCR instrument (ABI, USA). The fluorescent quantitative PCR reagent was SYBR@PreMix Ex TaqTM (TaKaRa, Japan). Relative quantitative PCR was calculated using the Livak and Schmittgen [

24] 2

-△△ CT method, and each reaction was repeated four times.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data and graphics were processed using Microsoft Excel 2010 and Photoshop 7.0.1 software. All test data were analyzed using SAS mathematical statistics analysis software (version 8.1) to perform an ANOVA for testing significant differences (P<0.05).

3. Results

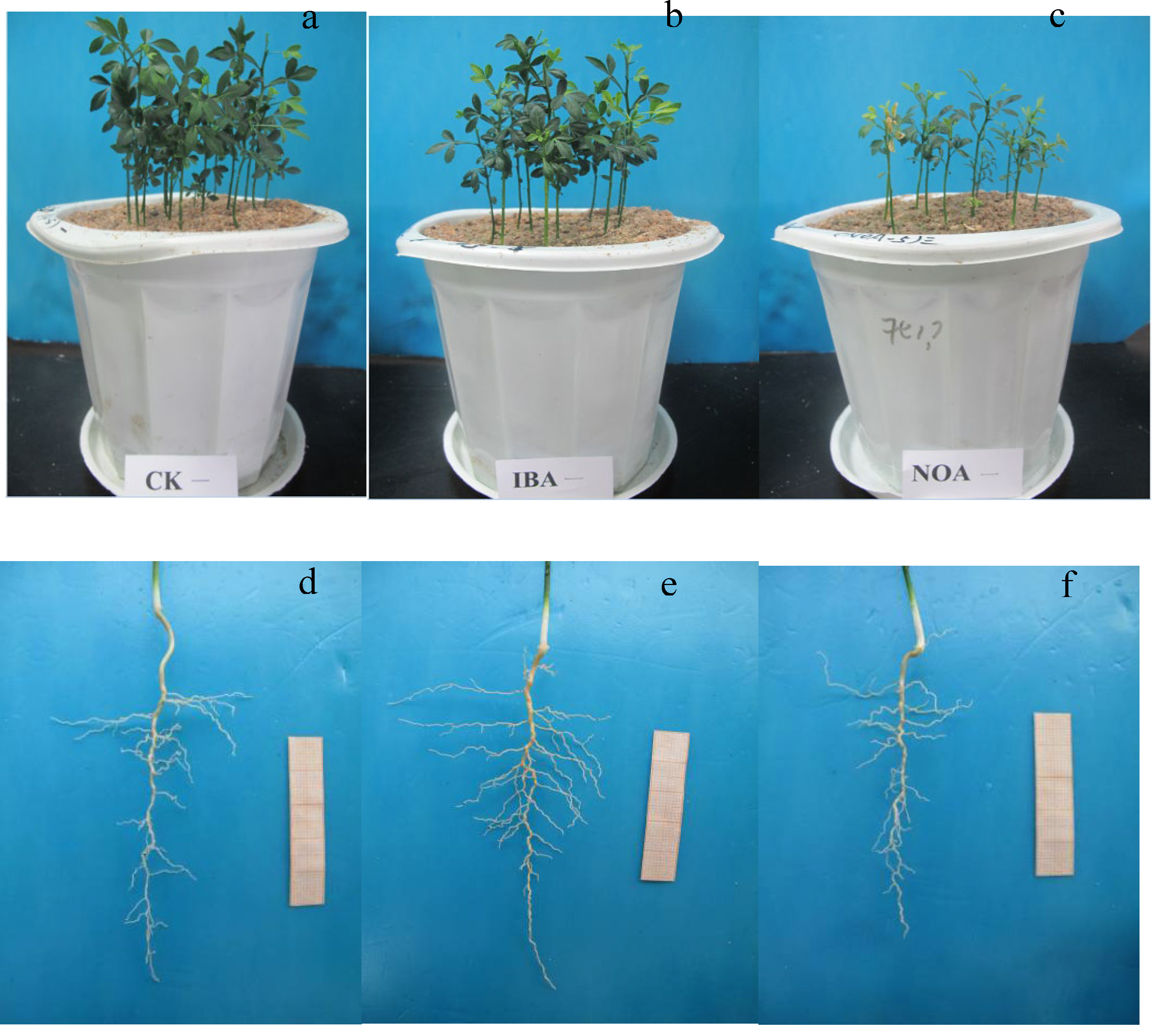

3.1. The Morphology of Trifoliate Orange Seedlings

As shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, IBA and 2-NOA treatments had a significant effect on trifoliate orange seedlings. Although exogenous IBA treatment did not cause significant changes in the aboveground part of the plant, root development in the underground part was noticeably more robust. Compared with the control, taproot length and lateral root density increased significantly. In contrast, the potted plants treated with 2-NOA were shorter, with sparse and yellow leaves. The overall root system was weaker than that of the control group, with shorter taproots and fewer shorter lateral roots compared to the control group.

3.2. The Growth of Main and Lateral Roots

To quantitatively evaluate the effects of auxin and its inhibitors on taproot and lateral root development of trifoliate orange seedlings, we analyzed the root phenotype data of trifoliate orange seedlings in each treatment group. As shown in

Figure 1, lateral root length increased by 123.08% after IBA treatment. Additionally, the length, diameter, and number of taproots significantly increased compared to the control group, by 17.56%, 18.18%, and 88.89%, respectively. In contrast, compared with the control group, 2-NOA treatment reduced taproot length, diameter, and lateral root length by 21.37%, 9.00%, and 10.26%, respectively. The number of lateral roots decreased by 88.89%. These results indicate that auxin and its inhibitors have significant effects on the roots of trifoliate orange seedlings.

Table 2.

Effects of IBA and 2-NOA on the growth of tap and lateral roots of trifoliate orange (mean±SD).

Table 2.

Effects of IBA and 2-NOA on the growth of tap and lateral roots of trifoliate orange (mean±SD).

| Treatment |

Tap root length (cm) |

Tap root diameter (cm) |

Lateral root length (cm) |

Lateral root number (#) |

| CK |

5.24±1.48b |

0.11±0.01b |

0.39±0.08b |

1.80±0.44b |

| 1.0 µmol•L-1 IBA |

6.16±0.39a |

0.13±0.01a |

0.87±0.22a |

3.40±1.63a |

| 50 µmol•L-1 2-NOA |

4.12±0.14c |

0.10±0.01b |

0.35±0.03c |

1.02±0.10c |

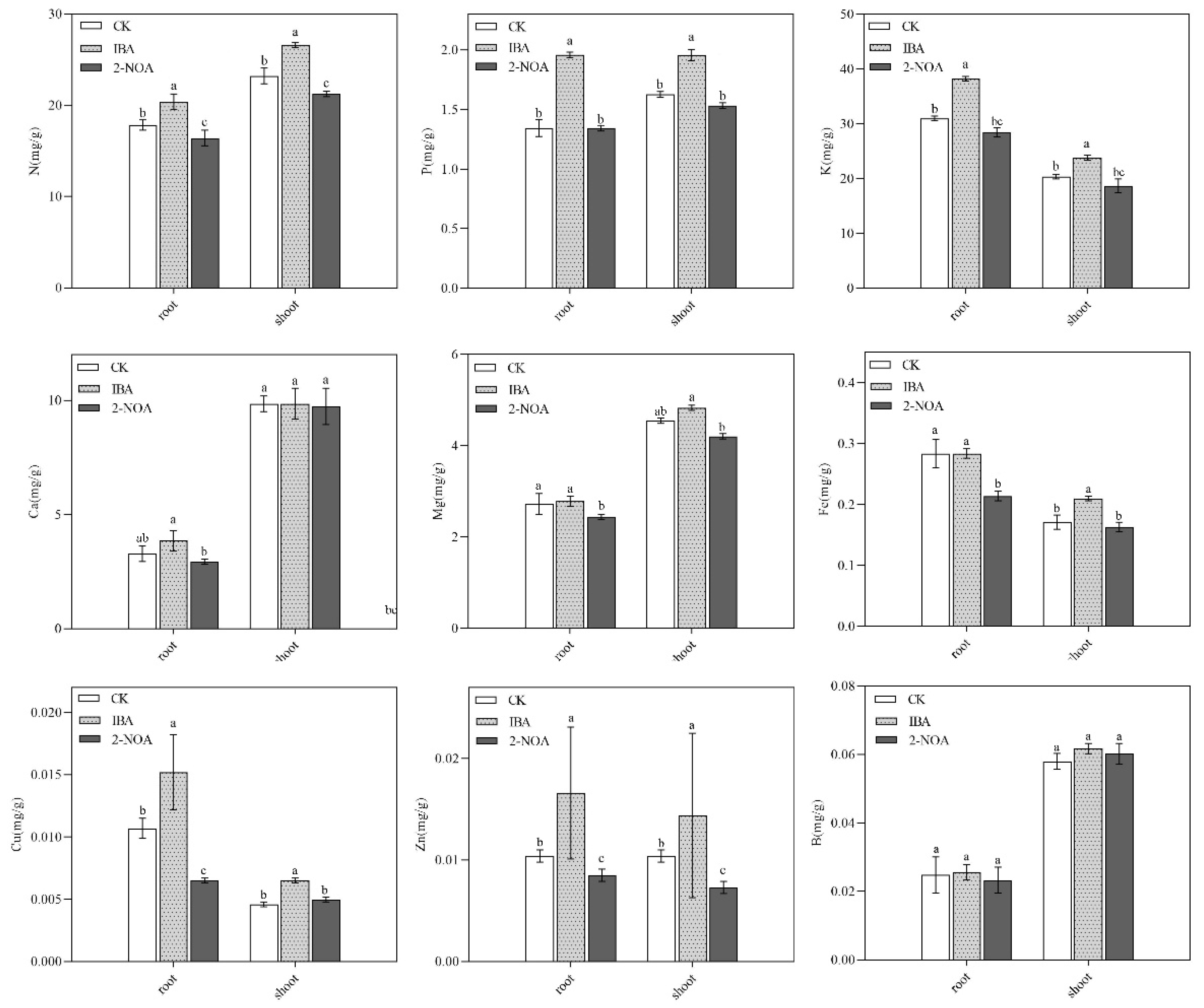

3.3. Variations in Plant Mineral Nutrient Composition

According to

Figure 2, treatment with IBA and its inhibitor 2-NOA had varying effects on the aboveground and root mineral concentrations of trifoliate orange seedlings. IBA treatment had the greatest effect on the concentrations of P, Cu, and Zn in trifoliate orange roots, increasing them by 45.61%, 42.86%, and 59.80%, respectively. Additionally, the concentrations of N, Ca, Mg, and B in trifoliate orange roots increased by 14.29%, 17.24%, 2.08%, and 3.03%, respectively. In the aboveground tissue, IBA treatment increased Cu and Zn concentrations by 41.67% and 38.14%, respectively. Similarly, the concentrations of N, P, Mg, and B in aboveground tissue increased by 14.63%, 20.29%, 6.25%, and 6.49%, respectively, while the concentration of Ca did not change. In contrast, 2-NOA treatment reduced Cu content in trifoliate orange roots by up to 39.29%. After 2-NOA treatment, the concentrations of N, Ca, Mg, Zn, and B in trifoliate orange roots decreased by 7.94%, 10.34%, 10.42%, 18.76%, and 6.06%, respectively, while the concentration of P did not change. In the aboveground tissue, 2-NOA treatment reduced Zn concentration by up to 29.58%. Similarly, N, P, Ca, and Mg concentrations in aboveground tissue decreased by 8.54%, 5.80%, 1.15%, and 7.50%, respectively. In contrast to other measured mineral contents, Cu and B concentrations in aboveground tissues increased after 2-NOA treatment by 8.33% and 3.9%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Effects of IBA and 2-NOA on the concentrations of N, P, K, Ca, Mg, Fe, Cu, Zn, and B in trifoliate orange seedlings.

Figure 2.

Effects of IBA and 2-NOA on the concentrations of N, P, K, Ca, Mg, Fe, Cu, Zn, and B in trifoliate orange seedlings.

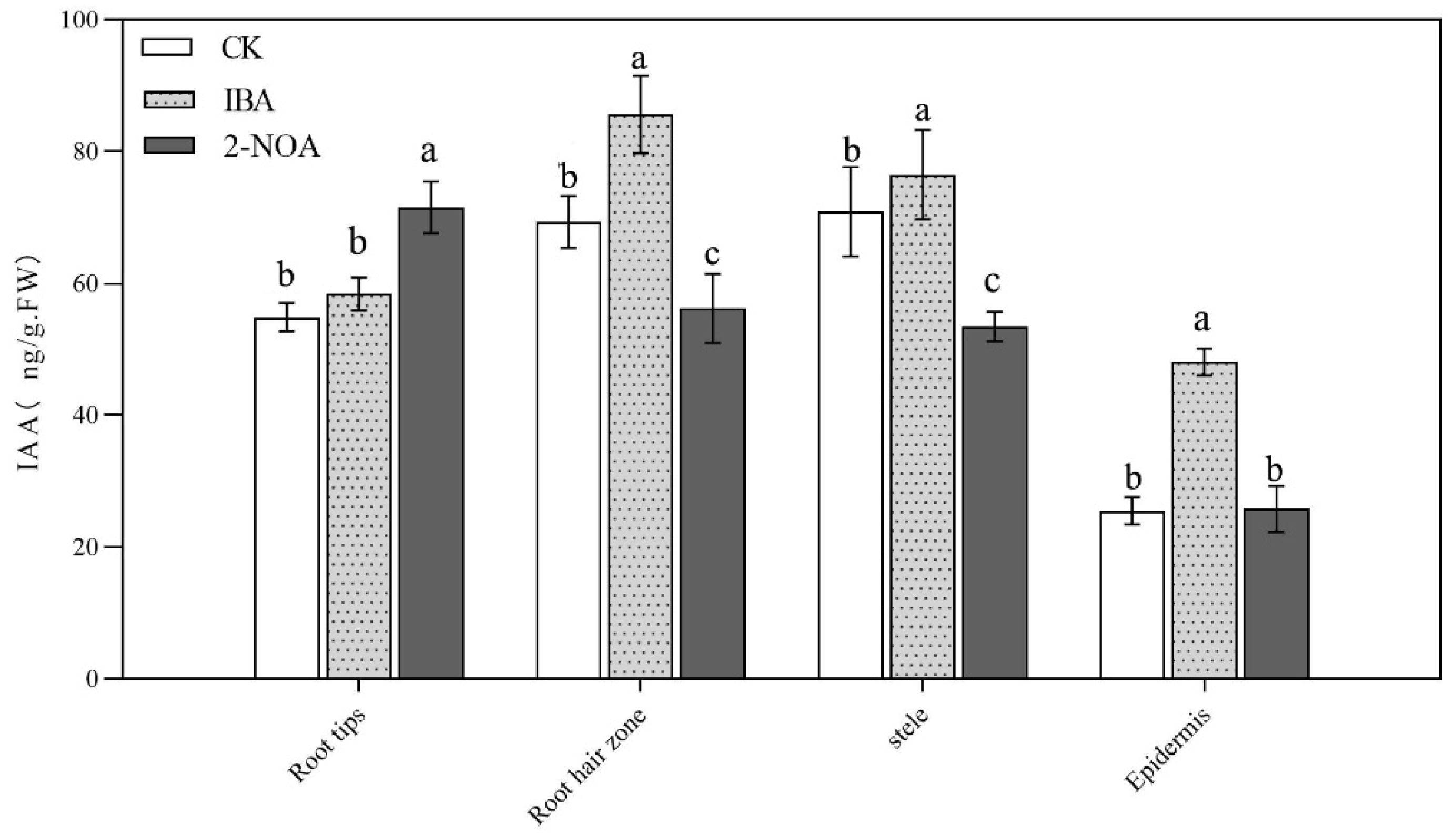

3.4. Measurement of Endogenous Auxin Content in Roots

To study the effects of exogenous auxin and its inhibitors on endogenous auxin, we compared the concentrations of endogenous IAA in the tissues of the lateral root tip, root hair area, root hair area epidermis, and middle column. Compared with the control group, IBA significantly increased the auxin concentration in the lateral root hair by 23.58% and 88.64%, respectively, while its effect on the lateral root tip and taproot epidermis was relatively minor, increasing the auxin concentration by 6.45% and 7.94%, respectively (

Figure 3). Interestingly, after treatment with IBA, the auxin concentration in the lateral root and apex increased significantly by 30.32%. In contrast, the concentrations in the lateral root hair and taproot epidermis decreased significantly by 18.87% and 24.60%, respectively. Remarkably, the taproot column remained largely unaffected.

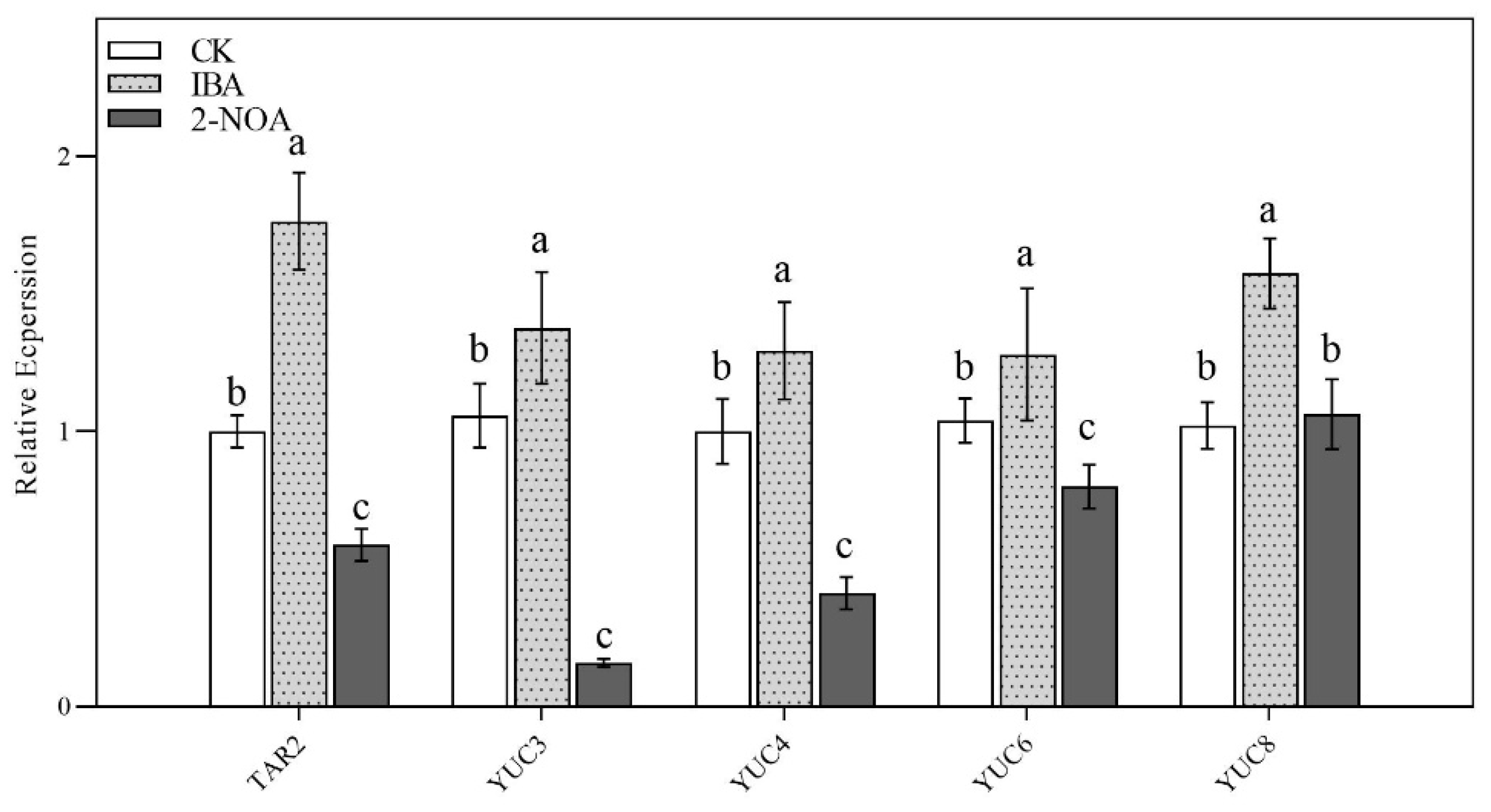

3.5. The Expression Levels of Root Auxin Biosynthesis and Transport Genes

Auxin synthesis is regulated by related genes, such as the

TARs gene, which regulates the conversion of tryptophan to indole 3-pyruvate (IPA), while the

YUCCAs family genes primarily promote the conversion of IPA to IAA [

26]. It is generally believed that the root tip is a key site for plant auxin synthesis; therefore, the root tip was selected for expression analysis. In this experiment, the relative expression levels of auxin synthesis-related genes (

TAR2,

YUC3,

YUC4,

YUC6,

YUC8) in lateral root tips were cloned and measured under exogenous auxin and its inhibitor treatments (

Figure 4). As shown in

Figure 4,

TAR2,

YUC3,

YUC4, and

YUC6 were positively regulated by IBA, with

TAR2 exhibiting the highest expression level, while 2-NOA significantly reduced its relative expression. In contrast,

YUC8 was positively regulated by IBA, and 2-NOA treatment had minimal effect on its expression.

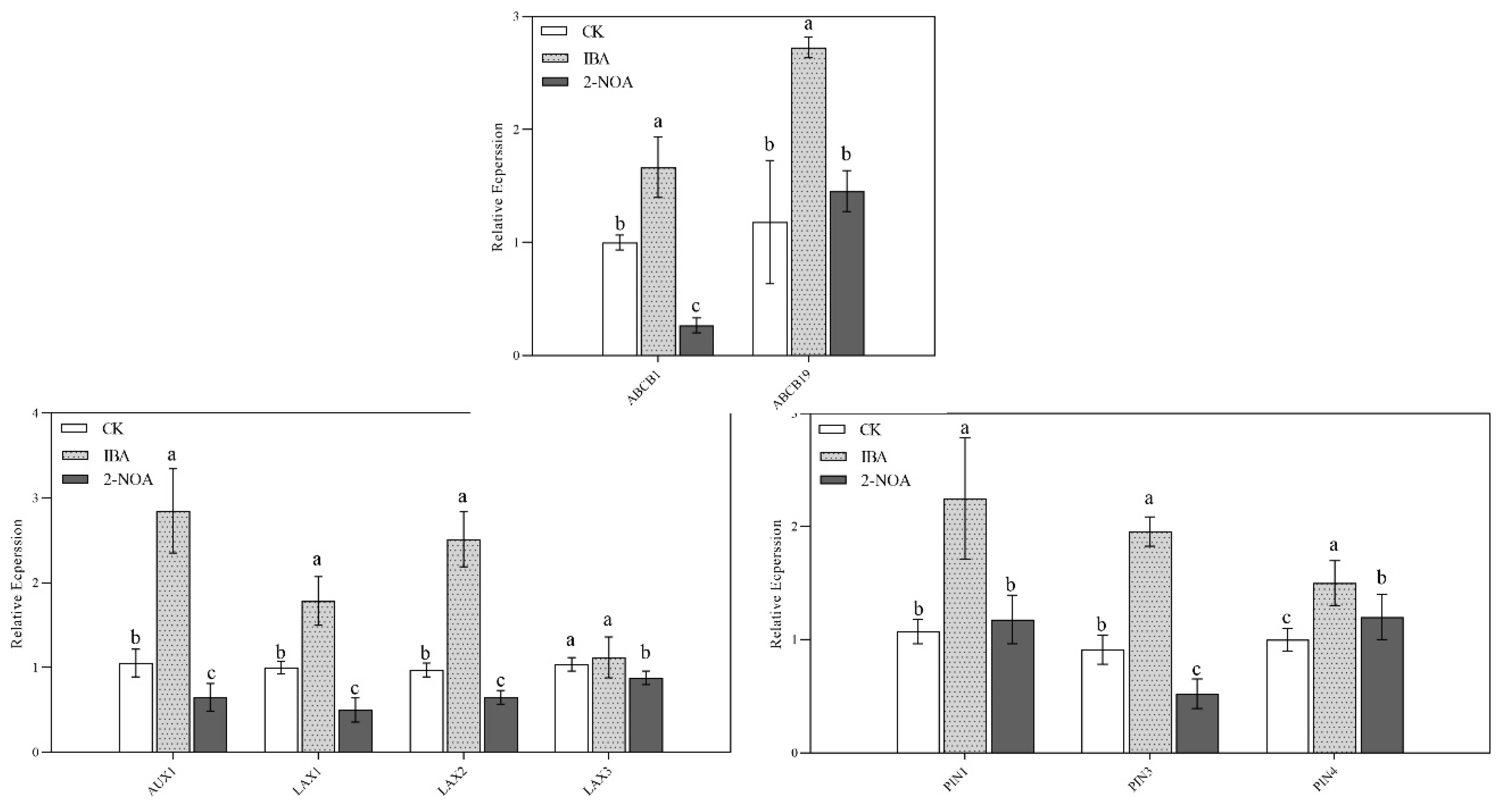

Auxin transport occurs through two modes: fast, long-distance, non-specific non-polar transport, and slower polar transport regulated by transport carriers [

27]. In this experiment, the relative expression levels of trifoliate orange auxin transport vector genes (

AUX1,

LAX1,

LAX2,

LAX3,

PIN1,

PIN3,

PIN4,

ABCB1,

ABCB19) in lateral root tips were cloned and measured (

Figure 5). As shown in

Figure 5, IBA treatment significantly up-regulated the expression levels of

AUX1,

LAX1, and

LAX2 in the input vector, while 2-NOA treatment significantly down-regulated their expression levels. The relative expression of

LAX3 was less pronounced than that of

AUX1,

LAX1, and

LAX2; however, 2-NOA treatment still led to down-regulated expression. As shown in

Figure 5, IBA treatment significantly up-regulated the expression levels of

PIN1,

PIN3, and

PIN4 in root tips within the output vector. In contrast,

2-NOA treatment significantly down-regulated the expression levels of

PIN3 in root tips but had no significant effect on

PIN1 and

PIN4. The effects of the

ABCB family on auxin transport in lateral root apex were analyzed by examining the

ABCB1 and

ABCB19 genes. IBA treatment significantly up-regulated the expression levels of both

ABCB1 and

ABCB19. However, 2-NOA treatment significantly down-regulated the expression level of

ABCB1 but had no significant effect on

ABCB19.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Auxin on the Root Growth of Trifoliate Orange

The results showed that IBA promoted the growth and development of the roots of trifoliate seedlings. Cavallari et al. demonstrated that auxin plays an important role in triggering and supporting plant root development, as well as in molecular regulatory pathways, which is consistent with our results [

28]. Previous studies have shown that auxin synthesis, transport, and signaling have significant effects on root growth and development [

29]. This was consistent with our observation that exogenous auxin significantly promoted the development of the trifoliate root system, increasing taproot length, taproot diameter, lateral root length, and lateral root number to varying degrees. In particular, lateral root growth was significantly enhanced. In contrast, the results indicated that 2-NBA had an inhibitory effect on the root growth, particularly on taproot length and the number of lateral roots. This is likely because 2-NOA affects the transport of auxin from the root tip to the base and the root hair area, leading to a reduced auxin concentration in the root hair area [

30].

4.2. Effect of Auxin on Mineral Nutrients of Trifoliate Orange

Minerals play an important role in the growth of plant roots, stimulating root growth and increasing surface area, thereby improving the efficiency of mineral absorption by plants [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. Our results showed that after IBA treatment, the concentrations of N, P, K, Ca, Cu, and Zn in the root system significantly increased, while the concentrations of Mg, Fe, and B remained almost unchanged. This indicated that IBA could enhance the efficiency of mineral nutrient uptake by plant roots. In contrast, 2-NOA significantly decreased the concentrations of N, K, Ca, Mg, Fe, and Cu in roots, slightly increased the concentration of B, and had minimal effects on P and Zn. Previous studies have shown that N is an essential component of plant metabolic activities, and P plays a key role in important metabolic processes. Photosynthesis and respiration rely heavily on K and Cu, which play particularly important roles in these processes. Therefore, it can be inferred that auxin enhances the growth capacity of trifoliate orange. However, after treatment with auxin inhibitors, the growth potential of the plants was significantly reduced [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. After IBA treatment, the contents of N, P, K, Mg, and Fe significantly increased. Meanwhile, Cu, Zn, and B showed slight increases, while Ca concentrations remained unchanged. In the aboveground tissues treated with 2-NOA, the concentrations of N, P, K, and Mg decreased significantly, while Fe, Cu, Zn, and B showed smaller decreases, and Ca concentrations remained unchanged. The changes in mineral concentrations in the aboveground tissues were generally consistent with those in the root system, except the concentration of Ca, which remained unaffected under any treatment. Based on the research of Sardans et al., this stability in Ca concentration may be attributed to its primary role in maintaining cell wall stability, which is not influenced by auxin in aboveground tissues [

46].

4.3. Expression of Auxin and Its Related Genes

In this study, the expression of several auxin synthesis genes and transport vector genes in the apex of trifoliate orange roots was analyzed. According to the experimental results, IBA treatment significantly increased the expression levels of auxin synthesis genes, including

TAR2,

YUC3,

YUC4,

YUC6, and

YUC8. Moreover, the expression levels of auxin transport genes

AUX1,

LAX1,

LAX2,

PIN1,

PIN3,

PIN4,

ABCB1, and

ABCB19 were also upregulated. This may be because exogenous auxin treatment significantly improved auxin synthesis and transport in trifoliate, consistent with the findings of Kohler and Peñuelas [

47]. Our study further demonstrated that exogenous auxin can stimulate the expression of

PIN,

YUC,

LAX, and

AUX family genes in plants, thereby promoting the growth and development of plants, consistent with previous studies [

48,

49]. Under 2-NOA treatment, the expression levels of auxin synthesis genes (

TAR2,

YUC3,

YUC4, and

YUC6) and auxin transport genes (

AUX1,

LAX1,

LAX2,

LAX3,

PIN3, and

ABCB1) were reduced, whereas the auxin output vectors

PIN1 and

PIN4 were unaffected. These results align with the findings of Zhang et al. [50] and Xi et al. [51].

PIN1 primarily regulates the polar transport of auxin to the root cap in midcolumn tissues, promoting taproot elongation, while

PIN4 mainly influences the polar transport of auxin to the root tip, thereby regulating root tip growth [50,51]. Therefore, it is speculated that 2-NOA does not impede auxin transport from the apex to the root tip but inhibits auxin transport from the base to the root hair region by down-regulating the expression of related auxin transport vector genes. This significantly reduces the auxin concentration in the root hair region, thereby inhibiting the normal development of the root hair in this region.

5. Conclusions

It can be concluded from our experiment that the addition of exogenous auxin promoted root elongation and increased lateral root density in trifoliate orange. Additionally, it regulated auxin concentrations in different parts of the roots through signaling pathways, thereby achieving control over root growth. By comparing the effects of exogenous auxin and auxin inhibitors on trifoliate orange growth, our findings demonstrate that auxin not only regulates the growth and development of the trifoliate root system but also regulates the absorption of mineral nutrients by plants.

Author Contributions

Y.W.Y. and Y.D.S.; methodology, Y.W.Y.; software, Y.D.S.; validation, C.L.T. and D.J.Z.; formal analysis, C.L.T.; investigation, Y.W.Y. and Y.D.S.; resources, D.J.Z.; data curation, Y.W.Y. and Y.D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W.Y. and Y.D.S.; writing—review and editing, C.L.T. and D.J.Z.; visualization, C.L.T.; supervision, C.L.T.; project administration, D.J.Z.; funding acquisition, D.J.Z.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32001984).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Quint, M.; Gray, W.M. Auxin signaling. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006, 9(5), 448-53. [CrossRef]

- Cavallari, N.; Artner, C.; Benkova, E. Auxin-regulated lateral root organogenesis. Csh Perspect Biol. 2021, 13(7), a039941. https://doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a03994.

- Meirav. Lavy.; Mark, Estelle. Mechanisms of auxin signaling. Development. 2016, 143(18), 3226-3229. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Barzee, T.J.; Zhang, R.; et al. Citrus: Integrated Processing technologies for food and agricultural by-products. Academic Press. 2019, 217-242. [CrossRef]

- Eekhout, J.P.C.; de, Vente, J. Global impact of climate change on soil erosion and potential for adaptation through soil conservation. Earth-Sci Rev. 2022, 226, 103921. [CrossRef]

- Rivas, M.Á. Friero, I,; Alarcón, M.V.; et al. Auxin-cytokinin balance shapes maize root architecture by controlling primary root elongation and lateral root development. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 836592. [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Huang, R. Auxin controlled by ethylene steers root development. Int J. Mol Sci. 2018, 19(11), 3656. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, B.W.; Kim, M.J.; Pandey, S.K.; et al. Recent advances in peptide signaling during Arabidopsis root development. J. Exp Bot. 2021, 72(8), 2889-2902. [CrossRef]

- Thelander, M.; Landberg, K.; Muller, A.; et al. Apical dominance control by TAR-YUC-mediated auxin biosynthesis is a deep homology of land plants. Curr Biol. 2022, 32(17), 3838-3846. e5. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jang, J.; Seomun, S.; et al. Division of cortical cells is regulated by auxin in Arabidopsis roots. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 953225. [CrossRef]

- Swarup R, Péret B. AUX/LAX family of auxin influx carriers—an overview. Front Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 32237. [CrossRef]

- Singh G, Retzer K, Vosolsobě S, et al. Advances in understanding the mechanism of action of the auxin permease AUX1. Int J. Mol Sci. 2018, 19(11), 3391. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.J.; Luo, J. The PIN-FORMED auxin efflux carriers in plants. Int J. Mol Sci. 2018, 19(9), 2759. [CrossRef]

- Vosolsobě, S.; Skokan, R.; Petrášek, J. The evolutionary origins of auxin transport: what we know and what we need to know. J. Exp Bot. 2020, 71(11), 3287-3295. [CrossRef]

- Fageria, N.K.; Moreira, A. The role of mineral nutrition on root growth of crop plants. Adv Agron. 2011, 110, 251-331. [CrossRef]

- Sardans, J.; Peñuelas, J. Potassium control of plant functions: Ecological and agricultural implications. Plants. 2021, 10(2), 419. [CrossRef]

- Farhat, N.; Elkhouni, A.; Zorrig, W.; et al. Effects of magnesium deficiency on photosynthesis and carbohydrate partitioning. Acta Physiol Plant. 2016, 38(6), 145. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, S. Dose-dependent responses of Arabidopsis thaliana to zinc are mediated by auxin homeostasis and transport. Environ Exp Bot. 2021, 189, 104554. [CrossRef]

- Borah, S.; Baruah, A.M.; Das, A.K.; et al. Determination of mineral content in commonly consumed leafy vegetables. Food Anal Method. 2009, 2, 226-230. [CrossRef]

- Kramberger, B.; Gselman, A.; Janzekovic, M.; et al. Effects of cover crops on soil mineral nitrogen and on the yield and nitrogen content of maize. Eur J Agron. 2009, 31(2), 103-109. [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.; Sabri, A.N.; Ljung, K.; et al. Auxin production by plant associated bacteria: impact on endogenous IAA content and growth of Triticum aestivum L. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2009, 48(5), 542-547. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Chen, L.L.; Ruan, X.; et al. The draft genome of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis). Nat Genet. 2013, 45(1), 59-66. [CrossRef]

- Ceng-Hong, H.U.; Shi-Dong, Y.; Cui-Ling, T.; et al. Ethylene modulates root growth and mineral nutrients levels in trifoliate orange through the auxin-signaling pathway. Not Bot Horti Agrobo. 2023, 51(3), 13269-13269. [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D.; Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔ CT method. Methods. 2001, 25(4), 402-408. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R. Mineral nutrition of plants. Plant Biology and Biotechnology: Volume I: Plant Diversity, Organization, Function and Improvement. 2015, 499-538. [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Di, D.W. Precise regulation of the TAA1/TAR-YUCCA auxin biosynthesis pathway in plants. Int J. Mol Sci. 2023, 24(10), 8514. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wu, L.; et al. Functional divergence of PIN1 paralogous genes in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60(12), 2720-2732. [CrossRef]

- Cavallari, N.; Artner, C.; Benkova, E. Auxin-regulated lateral root organogenesis. Csh Perspect Biol. 2021, 13(7), a039941. [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Huang, R. Auxin controlled by ethylene steers root development. Int J. Mol Sci. 2018, 19(11), 3656. [CrossRef]

- Poza-Viejo, L.; Abreu, I.; González-García, M.P.; et al. Boron deficiency inhibits root growth by controlling meristem activity under cytokinin regulation. Plant Sci. 2018, 270, 176-189. [CrossRef]

- Bouain, N.; Krouk, G.; Lacombe, B.; et al. Getting to the root of plant mineral nutrition: combinatorial nutrient stresses reveal emergent properties. Trends Plant Sci. 2019, 24(6), 542-552. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; et al. Nitrogen fertilization increases root growth and coordinates the root–shoot relationship in cotton. Front Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 880. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Fu, H.; Zhu, B.; et al. Potassium improves drought stress tolerance in plants by affecting root morphology, root exudates, and microbial diversity. Metabolites. 2021, 11(3), 131. [CrossRef]

- Omondi, J.O.; Lazarovitch, N.; Rachmilevitch, S.; et al. Phosphorus affects storage root yield of cassava through root numbers. J. Plant Nut. 2019, 42(17), 2070-2079. [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; et al. Effects of Magnesium Imbalance on Root Growth and Nutrient Absorption in Different Genotypes of Vegetable Crops. Plants, 2023, 12(20), 3518. [CrossRef]

- Salas-González, I.; Reyt, G.; Flis, P.; et al. Coordination between microbiota and root endodermis supports plant mineral nutrient homeostasis. Science. 2021, 371(6525), eabd0695. [CrossRef]

- Phuphong, P.; Cakmak, I.; Yazici, A.; et al. Shoot and root growth of rice seedlings as affected by soil and foliar zinc applications. J. Plant Nut. 2020, 43(9), 1259-1267. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, Q.; Xu, H.; et al. Analysis of metabolomic changes in xylem and phloem sap of cucumber under phosphorus stresses. Metabolites, 2022, 12(4), 361. [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Chen, X.F.; Deng, C.L.; et al. Magnesium-deficiency effects on pigments, photosynthesis and photosynthetic electron transport of leaves, and nutrients of leaf blades and veins in Citrus sinensis seedlings. Plants, 2019, 8(10), 389. [CrossRef]

- Adil, M.; Bashir, S.; Bashir, S.; et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles improved chlorophyll contents, physical parameters, and wheat yield under salt stress. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 932861. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Kang, H.; Chen, S..; et al. Gln-Lys isopeptide bond and boroxine synergy to develop strong, anti-mildew and low-cost soy protein adhesives. J Clean Prod. 2023, 397, 136505. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.M.; Ren, G.M.; Luo, K.J. Effects of Sepiolite and Mycorrhizals on Nutrient Element Absorptions of Maize in Heavy Metals Contaminated Soil. Advanced Materials Research. 2013, 800, 153-158. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.B.; Lu, X.H.; Deng, B.; et al. Adaptive mechanisms of the model photosynthetic organisms, cyanobacteria, to iron deficiency. Microbial photosynthesis. 2020, 197-244. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, J.; Pandey, N.; Saxena, J.; Role of potassium in plant photosynthesis, transport, growth and yield. Role of potassium in abiotic stress. 2022, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Sardans, J.; Peñuelas, J.; Potassium control of plant functions: Ecological and agricultural implications. Plants. 2021, 10(2), 419. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Scheres, B. Lateral root formation and the multiple roles of auxin. J. Exp Bot. 2018, 69(2), 155-167. [CrossRef]

- Leftley, N.; Banda, J.; Pandey, B.; et al. Uncovering how auxin optimizes root systems architecture in response to environmental stresses. Csh Perspectt Biol. 2021, 13(11), a040014. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Sun, L.; Qin, J.; et al. cGMP is involved in Zn tolerance through the modulation of auxin redistribution in root tips. Environ Exp Bot. 2018, 147, 22-30. [CrossRef]

- Xi, D.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; et al. Arabidopsis ANAC092 regulates auxin-mediated root development by binding to the ARF8 and PIN4 promoters. J. Integr Plant Biol. 2019, 61(9), 1015-1031. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).