1. Introduction

Yellow passion fruit (

Passiflora edulis f.

flavicarpa Deg.) is a crop of major economic and social importance in Brazil, widely adapted to tropical and subtropical regions and increasingly demanded by the food industry and other productive sectors [

1,

2].

The production of high-quality seedlings is crucial for the success of commercial orchards, as plant uniformity and vigor directly affect productivity and tolerance to abiotic stresses. However, in many producing regions, irrigation water contains elevated salt concentrations, compromising early seedling development and reducing the plants’ productive potential [

3,

4,

5].

Passion fruit is relatively sensitive to salinity (Ayers & Westcot, 1999), which triggers osmotic, ionic, and oxidative stress due to Na⁺ and Cl⁻ accumulation. These effects disrupt mineral nutrition and impair photosynthesis and growth [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Such responses, widely documented in cultivated species, highlight the need for effective mitigation strategies.

Among the proposed strategies, silicon (Si) has emerged as a promising agent for alleviating salt stress [

3,

11,

12,

13]. Si acts through multiple mechanisms, including restriction of Na⁺ uptake by roots, maintenance of ionic homeostasis, enhancement of nutrient acquisition, reinforcement of cell walls, regulation of water balance, and stimulation of antioxidant activity [

12,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Physiologically and nutritionally, Si modulates nutrient uptake and redistribution among plant tissues, directly influencing morphophysiological traits [

19,

20,

21]. Molecular studies have identified specific transporters, such as Lsi1 and Lsi2, which regulate silicic acid transport and explain interspecific variation in absorption capacity [

22,

23].

Exogenous Si application methods markedly affect its bioavailability and efficiency in mitigating salt stress. Soil application ensures a continuous supply of silicic acid in the rhizosphere, modifying ionic dynamics and influencing the microbial community, whereas foliar spraying enables direct absorption and rapid physiological responses [

13,

24,

25,

26,

27]. We hypothesize that combined soil and foliar applications may integrate local and systemic benefits, thereby enhancing nutritional and physiological performance.

In passion fruit, Si has been reported to improve seedling growth, water relations, and nutrient balance under saline conditions, although responses vary depending on cultivar, Si source, and application method [

3,

5,

11,

12]. Despite these advances, few studies have systematically compared application routes or explored their combined effects on macro- and micronutrient uptake and morphophysiological traits.

These knowledge gaps constrain practical recommendations for seedling production and hinder the broader adoption of Si as a salinity mitigation strategy. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of different Si application methods (soil, foliar, and combined) on the mitigation of salt stress in yellow passion fruit seedlings, focusing on the relationships among nutritional changes, morphophysiological responses, and seedling quality.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Conditions

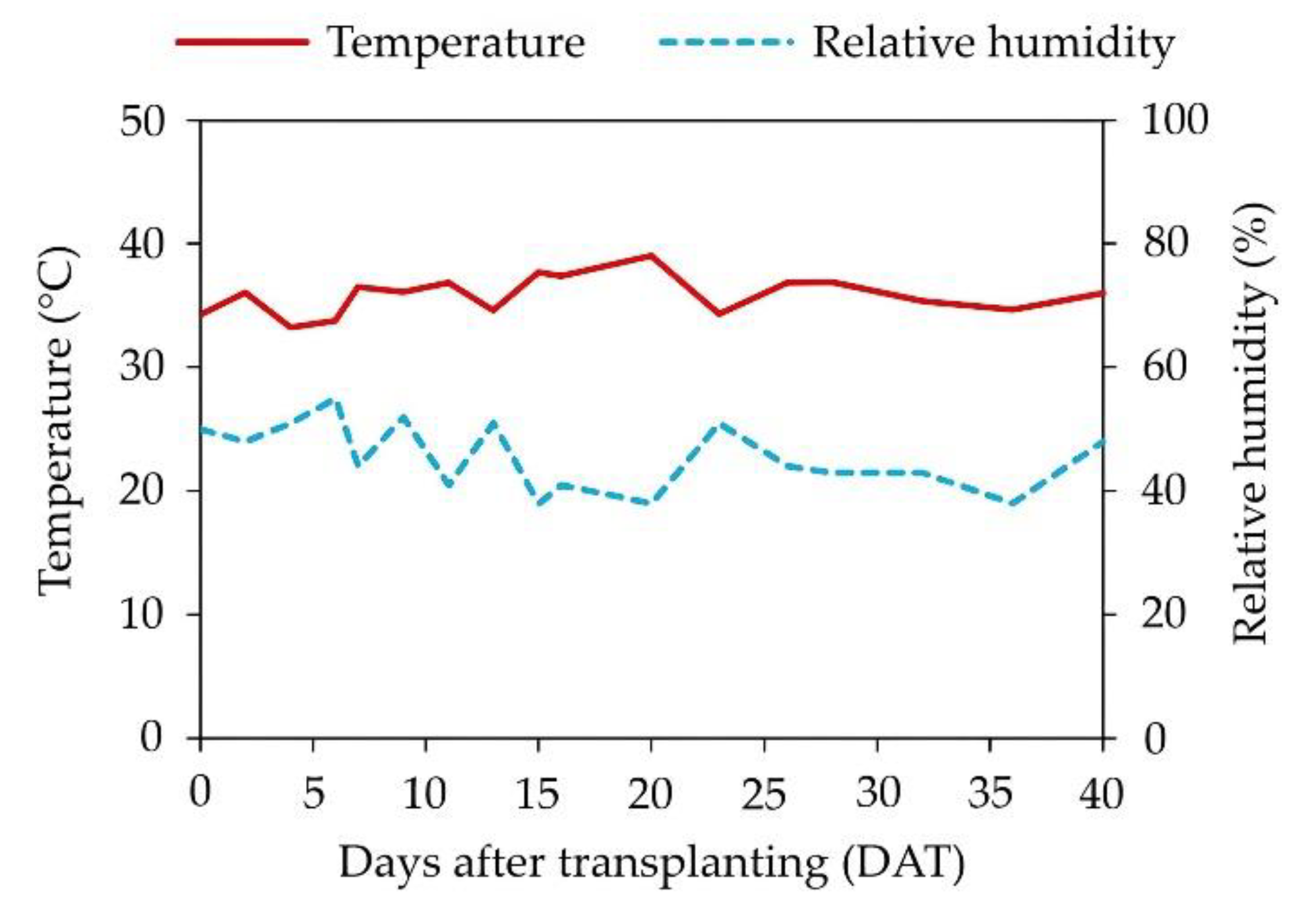

The experiment was conducted in a greenhouse from August to October 2023 at the Center for Human and Agricultural Sciences, Paraíba State University, located in Catolé do Rocha, Paraíba State, Brazil (6°21’10.295” S, 37°43’24.029” W; 252 m a.s.l.). The average air temperature and relative humidity recorded during the experimental period are presented in

Figure 1.

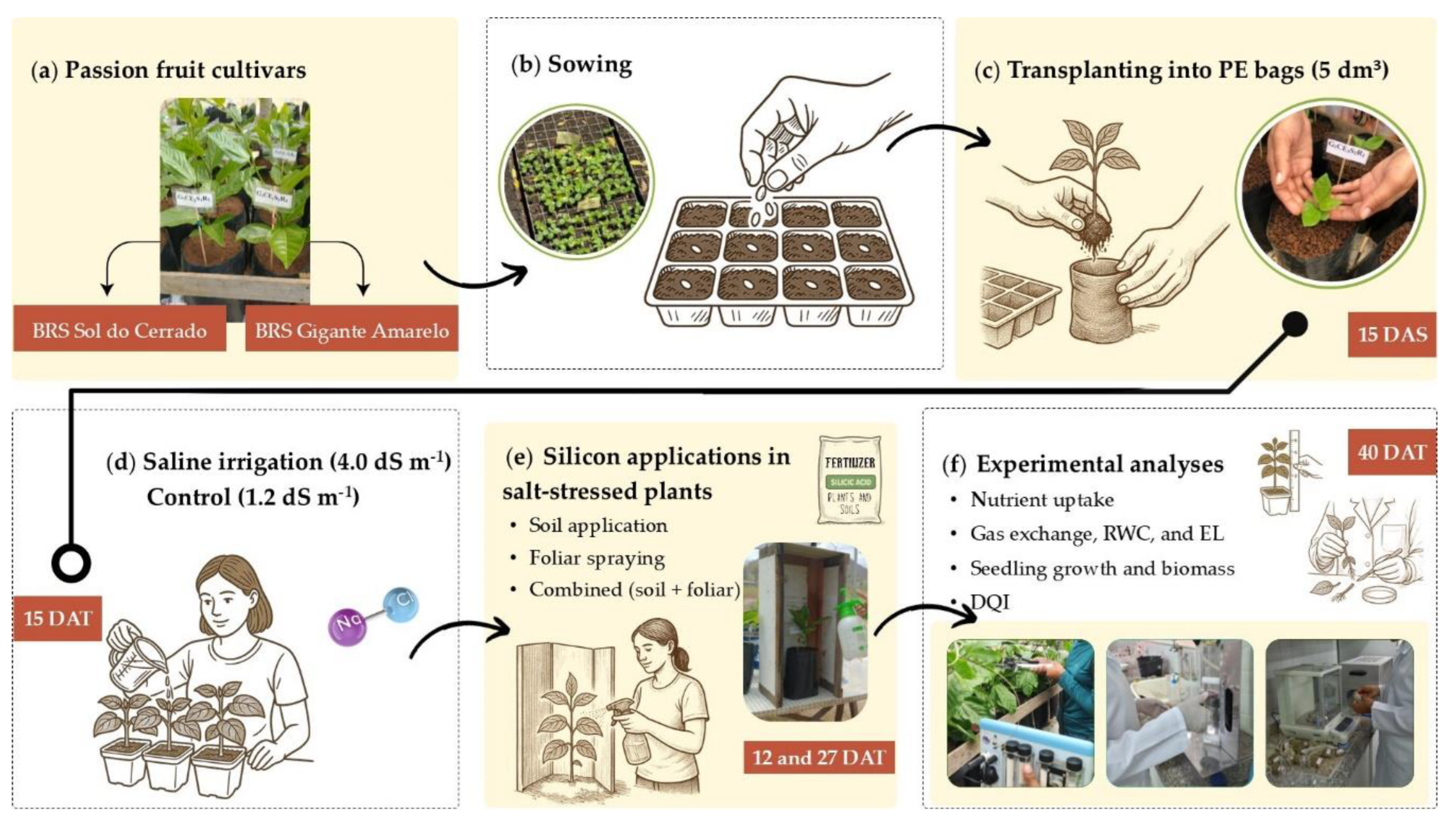

Seeds of two yellow passion fruit cultivars (

Figure 2A) were sown in polypropylene trays with cells of 0.0125 dm³ (

Figure 2B), filled with a substrate composed of soil and bovine manure (1:1, v/v). One seed was placed per cell. Fifteen days after sowing (DAS), seedlings were transplanted into polyethylene bags containing 5 dm³ of the same substrate (

Figure 2c). The physical and chemical properties of the soil and manure used in the substrate are shown in

Table 1.

2.2. Treatments and Experimental Design

The treatments consisted of two yellow passion fruit cultivars (BRS Sol do Cerrado and BRS Gigante Amarelo) combined with five management conditions involving salinity levels and silicon application methods: MC1 = irrigation with water at 1.2 dS m-1 (control); MC2 = irrigation with water at 4.0 dS m-1 (salt stress); MC3 = salt stress + soil-applied Si; MC4 = salt stress + foliar-sprayed Si; and MC5 = salt stress + combined Si application (50% soil and 50% foliar). The experiment followed a completely randomized design in a 2 × 5 factorial arrangement with five replicates. Each experimental unit consisted of a single plant.

The saline irrigation water for treatments MC2, MC3, MC4, and MC5 was prepared by dissolving sodium chloride in water from a shallow dug well (locally known as “Amazon well“) until reaching an electrical conductivity (EC) of 4.0 dS m-1.

Until 14 days after transplanting (DAT), all plants were irrigated with water from the dug well, which naturally had an EC of 1.2 dS m

-1 and the following chemical characteristics: pH = 6.9; Ca

2+ = 2.5, Mg

2+ = 1.48, Na

+ = 6.45, Cl

⁻ = 8.1, HCO

3⁻ = 2.75, SO

42⁻ = 0.18 mmol

c L

-1; and sodium adsorption ratio = 4.57 (mmol L

-1)

0.5. Plants in treatment MC

1 continued to receive this water throughout the experiment. High-salinity irrigation (4.0 dS m

-1) began at 15 DAT and was applied daily at 16:00 h (

Figure 2d).

The irrigation volume at each event was adjusted to meet plant water requirements over a 24-hour period using the drainage lysimetry method. The irrigation amount was estimated as the difference between the applied and drained volumes in the previous event, plus a 10% leaching fraction applied fortnightly.

Silicon was supplied using the commercial product Sifol® (silicic acid) with the following characteristics: 92% SiO2 (42.9% Si), bulk density 80–140 g L-1, particle size 8–12 µm, and pH 6.0–7.5.

Two Si applications were performed at 12 and 27 DAT (

Figure 2e). The treatments were conducted as follows: in MC

3, Si was applied to the soil around the plant collar using 150 mL of a solution containing 0.5 g Si L

-1 in distilled water; in MC

4, Si was foliar-sprayed using a solution of 0.2 g Si L

-1 until runoff; and in MC

5, a combined application was performed, with 150 mL of a 0.25 g Si L

-1 solution applied to the soil and a foliar spray of 0.1 g Si L

-1 until runoff.

2.3. Experimental Analyses

At 40 DAT, nutritional, physiological, and growth analyses were performed on yellow passion fruit plants (

Figure 2f).

2.3.1. Foliar Nutrient Content

For nutritional analyses, leaf samples were oven-dried at 65 °C to constant weight, ground using a knife mill, and analyzed according to the methodologies of Tedesco et al. [

28] and Meneghetti [

29]. The concentrations of carbon (C), nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg), iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), and manganese (Mn) were determined.

C content was determined using the Walkley–Black method, involving oxidation of organic carbon with 5 mL of potassium dichromate in acidic medium, followed by the addition of 10 mL of sulfuric acid and heating for 30 min. After cooling, 10 mL of phosphoric acid and an indicator were added, and the excess Cr⁶⁺ was titrated. N content was determined by sulfuric acid digestion, distillation, and titration following the Kjeldahl method. For P, K, Ca, Mg, Fe, Zn, and Mn, samples were pre-digested using a nitric–perchloric acid solution. P was quantified spectrophotometrically using the molybdenum blue method, K by flame photometry, and Ca, Mg, Fe, Zn, and Mn by atomic absorption spectrometry.

2.3.2. Physiological Traits

Physiological measurements were taken on the third fully expanded leaf of each plant in the morning (09:00–11:00 h). Stomatal conductance (gs) and CO2 assimilation rate (A) were measured using an infrared gas analyzer (IRGA, model CIRAS-3; PP Systems, Amesbury, MA, USA) under a constant photosynthetic photon flux density of 1,800 μmol m-2 s-1 and an airflow rate of 300 mL min-1.

Relative water content (RWC) and electrolyte leakage (EL) were determined from 1-cm-diameter leaf discs. For RWC, 10 discs per plant were weighed immediately to obtain fresh mass (FM), then rehydrated for 24 h in distilled water at room temperature to determine turgid mass (TM), and oven-dried at 65 °C for 48 h to obtain dry mass (DM). RWC was calculated as: RWC = [(FM - DM)/(TM - DM)] × 100. For EL, five discs per plant were incubated in 10 mL of deionized water for 90 min, and the initial electrical conductivity (ECi) was recorded. Samples were then heated at 80 °C for 90 min, and final conductivity (ECf) was measured. EL was calculated as: EL = (ECi/ECf) × 100.

2.3.3. Seedling Growth and Quality

Plant height (PH), root length (RL), and plant dry mass (PDM) were measured to assess growth. PH was measured from the substrate surface to the tip of the highest leaf, and RL from the plant collar to the apex of the main root after substrate removal. For PDM, plants were oven-dried at 65 °C to constant weight and weighed using a precision balance (0.01 g).

Seedling quality was evaluated using the Dickson Quality Index (DQI) [

30], calculated as:

Where:

PDM - plant dry mass (g);

PH - plant height (cm);

SD - stem diameter (mm);

SDM and RDM - shoot dry mass and root dry mass (g), respectively.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were tested for normality (Shapiro–Wilk) and homoscedasticity (Bartlett). When assumptions were met, factorial ANOVA was performed. Means of the cultivars were compared using Student’s t-test (p ≤ 0.05), and means of the management conditions (salinity and silicon treatments) were compared using the Scott–Knott test (p ≤ 0.05). Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted in R version 4.5.1 (R Core Team, 2025) using the FactoMineR package.

3. Results

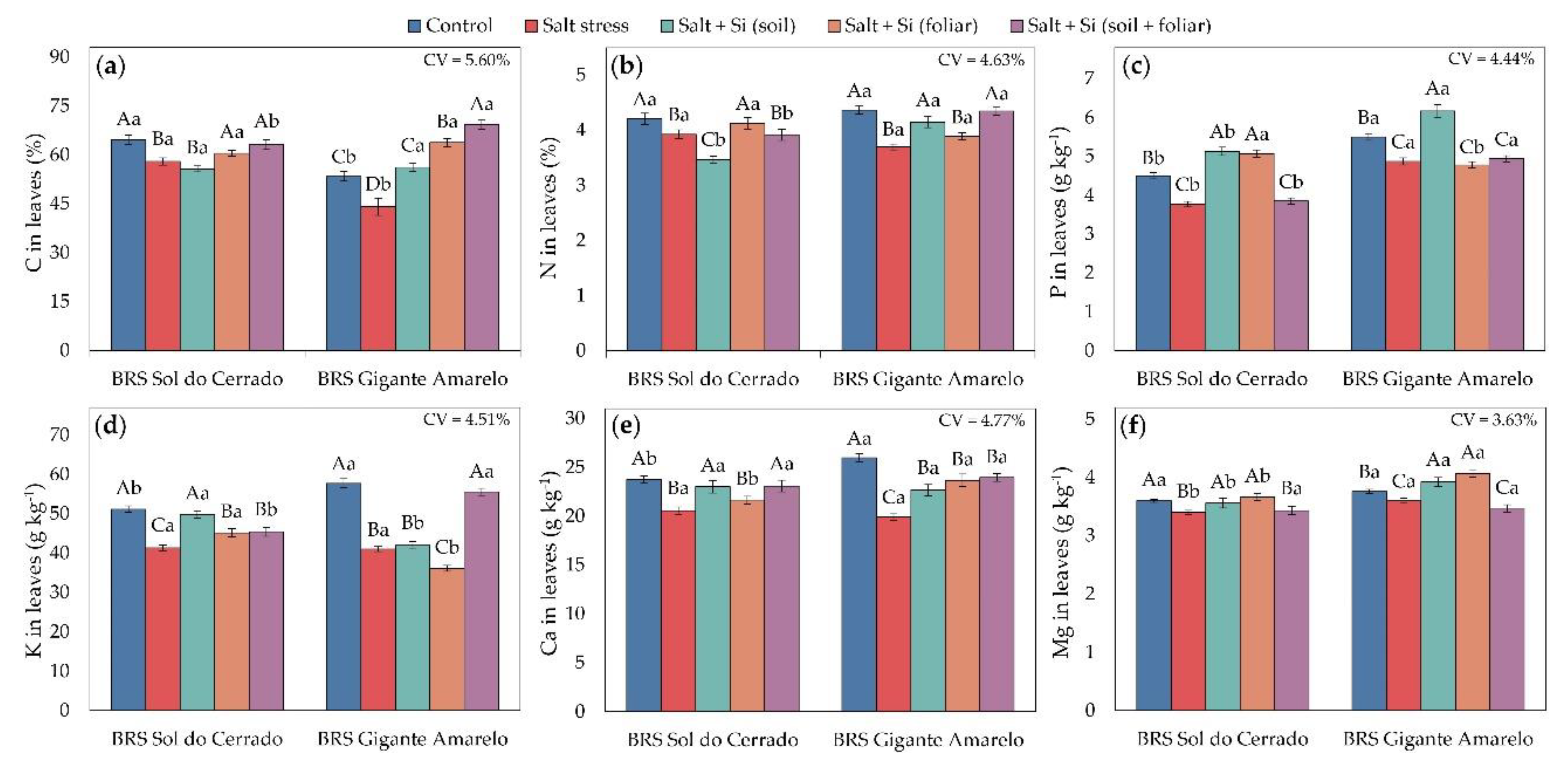

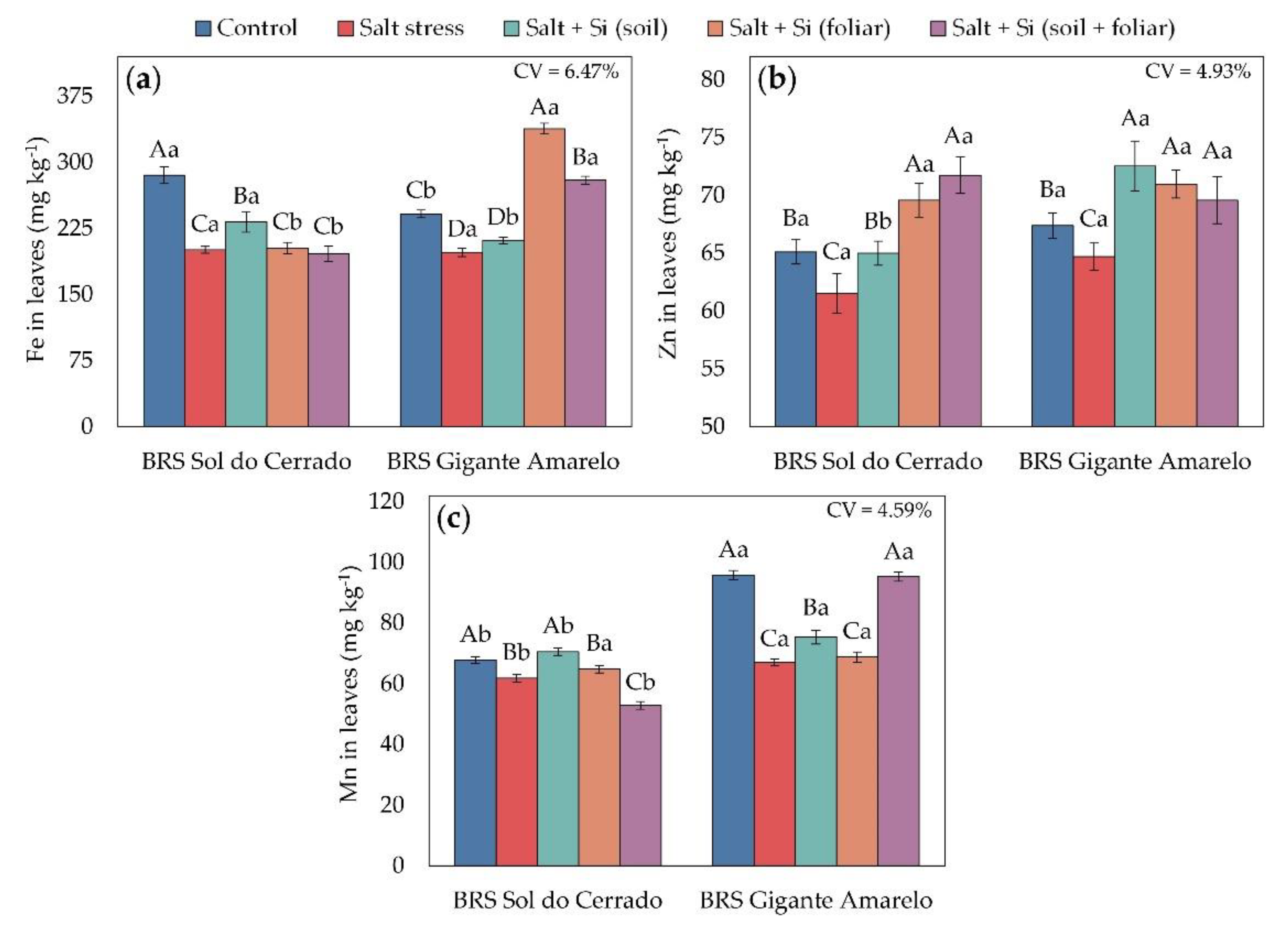

3.1. Foliar Mineral Element Content

The interaction between passion fruit cultivars and management conditions, including salinity levels and silicon application methods, significantly affected foliar concentrations of C (p < 0.0001), N (p < 0.0001), P (p < 0.0001), K (p < 0.0001), Ca (p = 0.0120), Mg (p = 0.0199), Fe (p < 0.0001), Zn (p = 0.0426), and Mn (p < 0.0001), according to factorial ANOVA.

Irrigation with saline water (4.0 dS m

-1) generally reduced foliar macronutrient concentrations in both yellow passion fruit cultivars (

Figure 3). In BRS Sol do Cerrado, salt stress caused reductions of 10% in C (

Figure 3a), 7% in N (

Figure 3b), 16% in P (

Figure 3c), 19% in K (

Figure 3d), 13% in Ca (

Figure 3e), and 6% in Mg (

Figure 3f), relative to the control (1.2 dS m

-1). In BRS Gigante Amarelo, the corresponding reductions were 17%, 15%, 11%, 29%, 23%, and 5%, respectively.

Certain Si application methods mitigated nutrient losses and promoted macronutrient accumulation under high salinity, with responses depending on the cultivar and application route. In BRS Sol do Cerrado, foliar spraying and combined application (soil + foliar) increased C by 4% and 9%, respectively, compared with plants without Si (

Figure 3a). In BRS Gigante Amarelo, all Si application methods enhanced foliar C by 27% (soil), 45% (foliar), and 57% (soil + foliar) relative to non-supplemented plants.

For N (

Figure 3b), in BRS Sol do Cerrado under high salinity, only foliar Si application increased foliar N by 5% compared with plants without Si. In contrast, in BRS Gigante Amarelo, soil and combined applications increased N by 12% and 18%, respectively. Regarding P (

Figure 3c), in BRS Sol do Cerrado, soil and foliar applications increased P by 36% and 34%, respectively, whereas in BRS Gigante Amarelo, only soil application produced a 27% increase relative to plants without Si. For K (

Figure 3d), in BRS Sol do Cerrado, soil, foliar, and combined applications increased K by 21%, 9%, and 10%, respectively, compared with non-supplemented plants. In BRS Gigante Amarelo, only the combined application increased foliar K by 35% relative to the control.

For Ca (

Figure 3e), in BRS Sol do Cerrado, soil and combined applications increased foliar Ca by 12% under salt stress compared with plants without Si. In BRS Gigante Amarelo, all Si application methods enhanced foliar Ca by 13% (soil), 19% (foliar), and 20% (combined) relative to non-supplemented plants. Regarding Mg (

Figure 3f), soil and combined applications increased foliar Mg in both cultivars under salt stress, by 5% and 8% in BRS Sol do Cerrado and 9% and 13% in BRS Gigante Amarelo, respectively, compared with plants without Si.

Foliar micronutrient concentrations were also influenced by salinity and Si management (

Figure 4). In BRS Sol do Cerrado under salt stress, Foliar Fe (

Figure 4a) increased by 16% only with soil Si application compared with plants without Si. In BRS Gigante Amarelo under 4.0 dS m

-1, foliar spraying and combined application (soil + foliar) increased Fe by 71% and 41%, respectively. For Zn (

Figure 4b), all Si application methods increased foliar Zn in both cultivars, by 6%, 13%, and 17% in BRS Sol do Cerrado, and by 12%, 10%, and 8% in BRS Gigante Amarelo for soil, foliar, and combined applications, respectively, relative to non-supplemented plants. Regarding Mn (

Figure 4c), only soil application increased foliar Mn by 14% in BRS Sol do Cerrado, whereas in BRS Gigante Amarelo, only the combined application increased Mn by 42% compared with plants without supplementation.

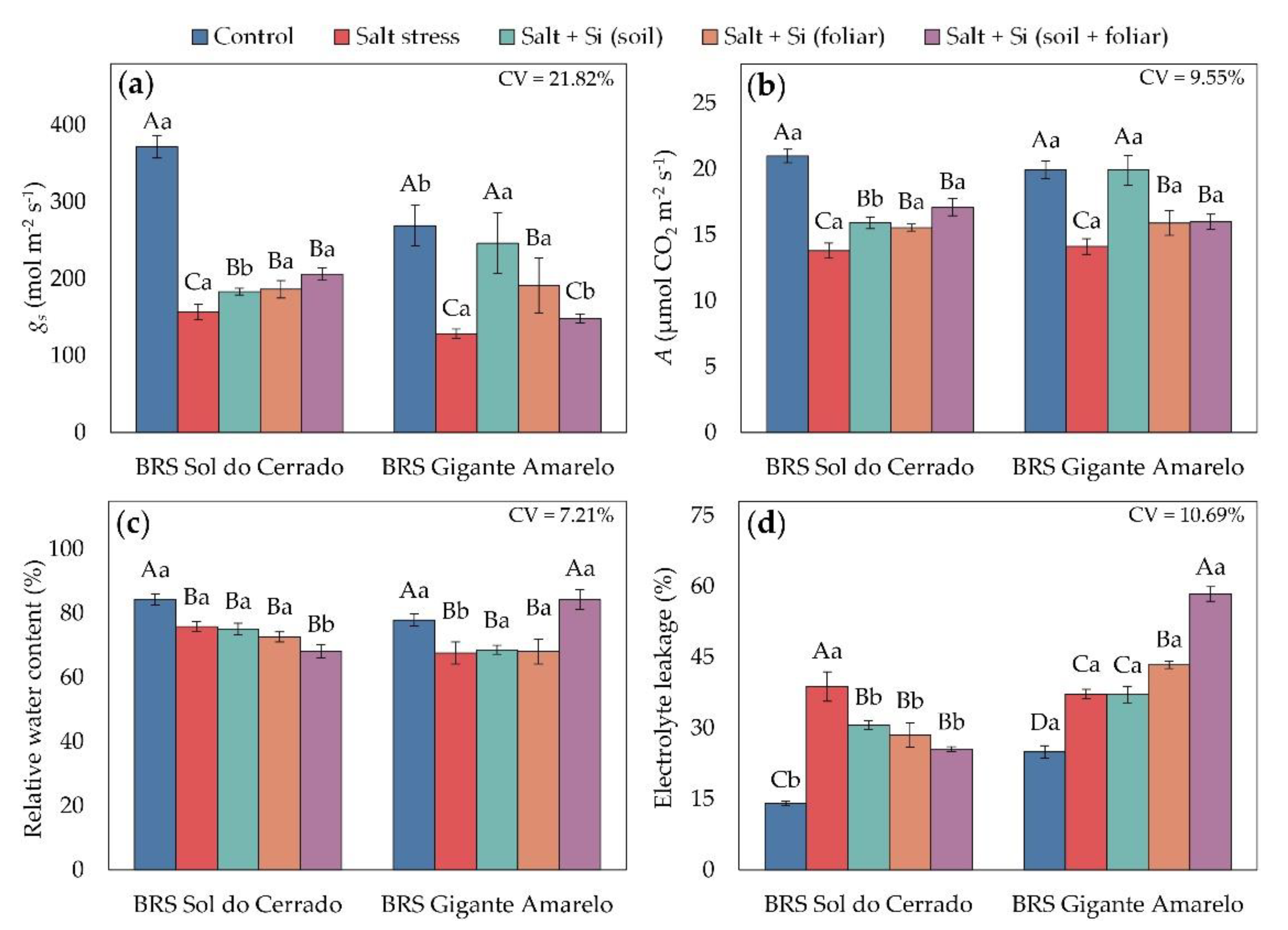

3.2. Physiological Traits

According to factorial ANOVA, the interaction between passion fruit cultivars and management conditions was significant for stomatal conductance (p = 0.0032), CO

2 assimilation rate (p = 0.0067), leaf relative water content (p < 0.0001), and electrolyte leakage (p < 0.0001). All these variables were negatively affected by irrigation with high-salinity water (EC = 4.0 dS m

-1) in the absence of Si (

Figure 5). In BRS Sol do Cerrado under salt stress,

gs decreased by 58% (

Figure 5a),

A by 34% (

Figure 5b), and RWC by 10% (

Figure 5c), while EL increased by 176% (

Figure 5d). In BRS Gigante Amarelo, reductions were 52% for

gs, 29% for

A, and 13% for RWC, whereas EL increased by 49% compared with the control (1.2 dS m

-1).

Silicon application improved gas exchange in both cultivars under salt stress. In BRS Sol do Cerrado at 4.0 dS m

-1,

gs increased by 18%, 19%, and 31% with soil, foliar, and combined applications, respectively (

Figure 5a). In BRS Gigante Amarelo,

gs increased by 92% with soil application and 49% with foliar spraying compared with stressed plants without Si. Regarding CO

2 assimilation (

Figure 5b), all Si application methods enhanced

A in both cultivars under salinity. In BRS Sol do Cerrado, increases in

A were 15% (soil), 13% (foliar), and 24% (combined), whereas in BRS Gigante Amarelo, the corresponding increases were 41%, 12%, and 13%.

Relative water content (

Figure 5c) and electrolyte leakage (

Figure 5d) showed contrasting behaviors between cultivars under saline stress. In BRS Sol do Cerrado, silicon application did not significantly change RWC under high salinity, while in BRS Gigante Amarelo, the combined soil + foliar application improved RWC by 25% compared to untreated stressed plants. Regarding membrane stability, in BRS Sol do Cerrado, soil, foliar, and combined Si applications reduced EL by 21%, 26%, and 34%, respectively, compared with non-supplemented plants. In BRS Gigante Amarelo, EL increased by 17% with foliar spraying and 57% with combined application relative to stressed plants without Si.

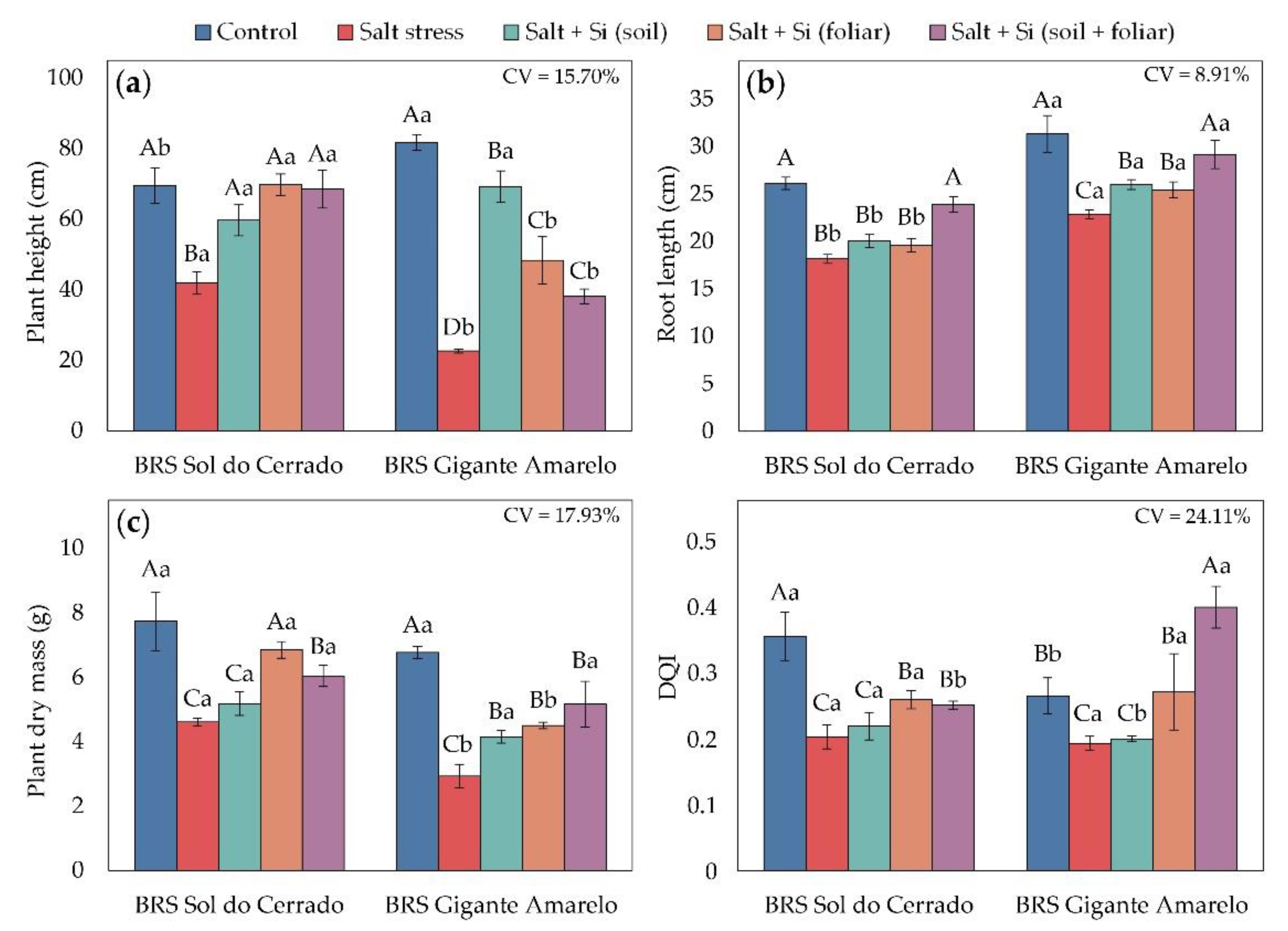

3.3. Seedling Growth and Quality

Factorial ANOVA revealed that the interaction between cultivars and management conditions significantly influenced plant height (p < 0.0001), root length (p < 0.0001), plant dry mass (p < 0.0001), and the Dickson Quality Index (p = 0.0007). When compared with the control treatment (1.2 dS m

-1), both cultivars exhibited marked reductions in all growth and quality parameters under irrigation with high-salinity water (4.0 dS m

-1) (

Figure 6). In BRS Sol do Cerrado, reductions reached 40% in plant height (

Figure 6a), 30% in root length (

Figure 6b), 40% in dry mass (

Figure 6c), and 43% in DQI (

Figure 6d). In BRS Gigante Amarelo, the corresponding decreases were 72%, 27%, 57%, and 27%.

Plant height and root length responded differently to the silicon application methods under salt stress (

Figure 6a and

Figure 6b). In BRS Sol do Cerrado, soil, foliar, and combined (soil + foliar) applications increased PH by 43%, 67%, and 64%, respectively, compared with high-salinity plants without Si (

Figure 6a). In BRS Gigante Amarelo, increases were more pronounced: 206%, 113%, and 68%, respectively, under the same treatments. Similar patterns were observed for root length (

Figure 6b), with the combined Si application yielding the greatest increases (32% in BRS Sol do Cerrado and 28% in BRS Gigante Amarelo), followed by soil (10% and 14%) and foliar (8% and 11%) applications.

Plant dry mass (

Figure 6c) also improved under salt stress with the application of Si. In BRS Sol do Cerrado, foliar and combined treatments increased dry mass by 49% and 31%, respectively, relative to the saline control. In BRS Gigante Amarelo, Si applied to the soil, leaves, or both increased dry mass by 42%, 54%, and 76%, respectively, showing that combined application provided the greatest benefit for biomass accumulation.

The Dickson Quality Index was consistently affected by salinity and silicon application across both cultivars (

Figure 6d). Under irrigation with 4.0 dS m

-1 water, soil-applied Si increased DQI by 28% in BRS Sol do Cerrado and 41% in BRS Gigante Amarelo relative to non-supplemented plants. When Si was applied via both soil and foliar routes, DQI further increased by 24% in BRS Sol do Cerrado and by 107% in BRS Gigante Amarelo.

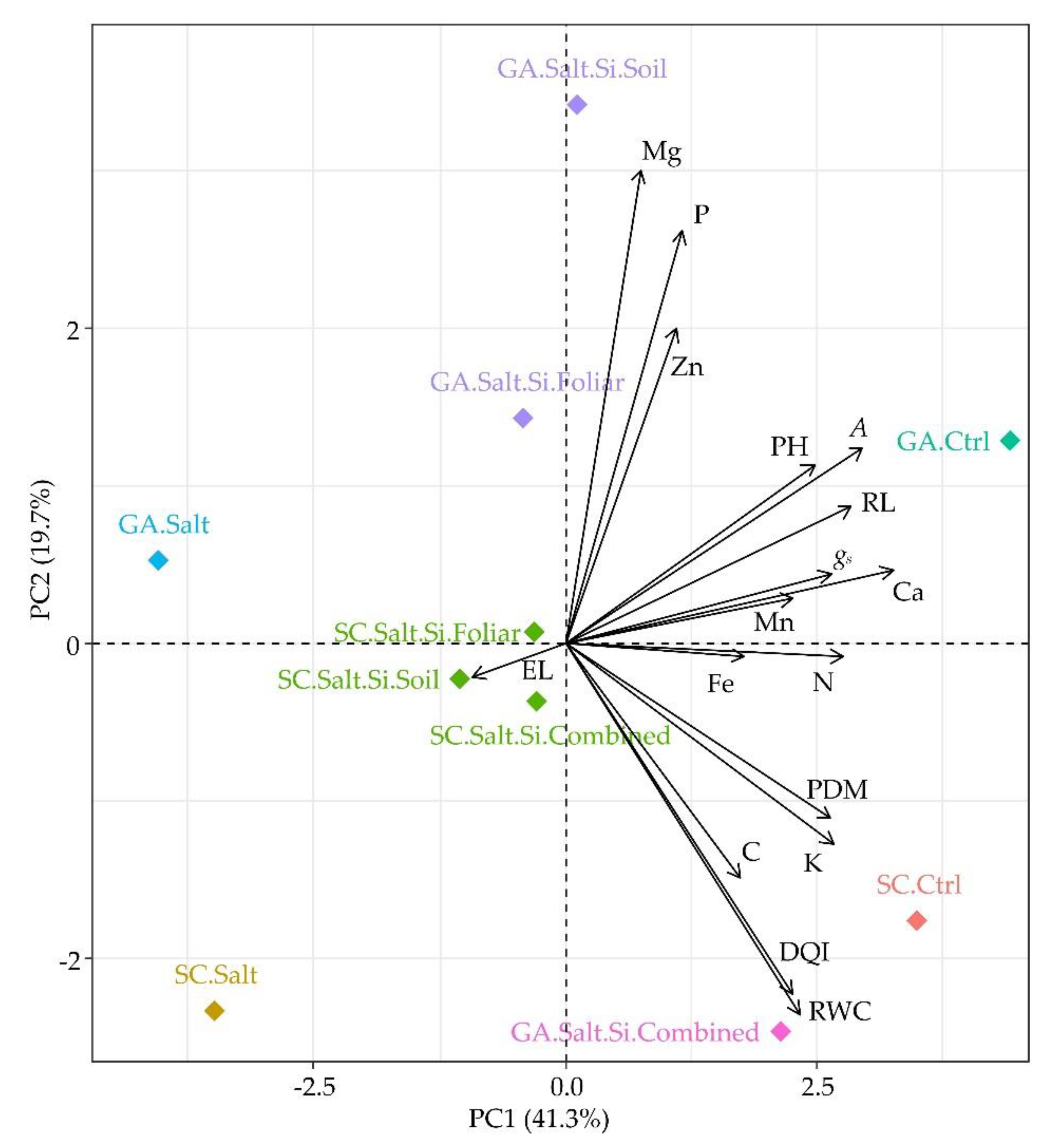

3.4. PCA Analysis

Principal component analysis explained 61% of the total variance across the first two components (PC1 = 41.3%; PC2 = 19.7%). PC1 distinguished treatments related to improved morphophysiological and nutritional performance (PH,

gs,

A, PDM, Ca, N, and Fe) on the positive semiaxis from those associated with salt-induced damage, characterized by higher EL, on the negative semiaxis (

Figure 7). PC2 captured a secondary response dimension emphasizing Mg and P on its positive side. Correlation analysis revealed strong positive associations among PH,

gs,

A, PDM, Ca, N, and Fe, whereas EL showed negative correlations with these parameters.

The PCA identified seven distinct groups, represented by different colors in the biplot. Control treatments (1.2 dS m-1) of both cultivars were located on the positive side of PC1, near vectors representing growth, gas exchange, and the nutrients Ca and N. Treatments exposed solely to high salinity were positioned toward the negative side of PC1, in association with the EL vector.

Silicon-supplemented treatments were distributed between these extremes, with their positioning influenced by cultivar and application method. In BRS Gigante Amarelo, soil application was closely associated with Mg and P and moderately with Zn, whereas combined application shifted samples toward DQI and RWC vectors, indicating strong positive associations with these traits. Additionally, a moderate positive correlation was observed between GA.Salt.Si.Combined and foliar C content. In BRS Sol do Cerrado, Si-treated plants clustered near the plot’s center, exhibiting reduced EL compared with salt-stressed plants lacking Si supplementation.

4. Discussion

Irrigation with high-electrical-conductivity water (4.0 dS m

-1) reduced foliar macro- and micronutrient contents (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), compromised gas exchange and water status (

Figure 5), and impaired the growth and morphology of Passiflora edulis seedlings (

Figure 6). These effects are widely reported in the literature and result from immediate osmotic stress, subsequent ionic stress due to Na⁺ and Cl⁻ accumulation, and oxidative stress that together reduce cell turgor, limit carbon assimilation, and disrupt ion homeostasis [

8,

10,

32,

33]. In the present study, osmotic stress likely induced stomatal closure and decreased CO

2 diffusion into chloroplast, while ionic imbalance increased the Na

+/K

+ ratio, impairing enzymatic processes and promoting reactive oxygen species formation.

Supplementation with silicon via different application routes mitigated many of these adverse effects, with responses dependent on both the cultivar and application method. At the nutritional level, Si applications (soil, foliar spraying, and especially combined) restored or increased foliar contents of C, N, P, K, Ca, and Mg compared with salt-stressed plants without Si (

Figure 3), with BRS Gigante Amarelo showing greater responsiveness. These findings agree with studies reporting enhanced nutrient uptake under salinity when Si is supplied [

5,

12,

16,

18,

34].

The silicon application route was a key determinant of Si efficacy. Foliar and combined applications produced stronger increases in foliar carbon (

Figure 3a) and more pronounced recovery of morphophysiological parameters (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) than soil-only application. This behavior is consistent with the rapid absorption of soluble Si forms through the leaf surface and the complementary benefits of root uptake in the rhizosphere [

21,

26,

35]. According to previous studies [

5,

25,

27,

36,

37], foliar uptake provides a fast protective effect on leaf tissues and photosynthetic machinery, while root-applied Si modifies the rhizosphere chemistry and root structure, resulting in additive benefits when both methods are combined.

At the physiological level, increases in stomatal conductance (

Figure 5a) and CO

2 assimilation rate (

Figure 5b) in salt-stressed seedlings supplemented with Si suggest preservation of the photosynthetic apparatus [

5,

14,

17,

38]. Maintained stomatal aperture and higher assimilation rates under Si supply likely reflect osmotic adjustment and protection of chloroplast ultrastructure from oxidative damage. Regarding membrane stability, the observed reductions in electrolyte leakage (

Figure 5d), particularly in BRS Sol do Cerrado, indicate reinforcement of the cell wall through Si deposition associated with hemicelluloses, pectins, and phenolic compounds [

17,

39]. The contrasting EL response observed in BRS Gigante Amarelo may reflect genotypic variation in Si accumulation and redistribution or dose- and time-dependent effects.

The increases in K (

Figure 3d), Ca (

Figure 3e), and Mg (

Figure 3f) in Si-supplemented plants, especially in BRS Gigante Amarelo, indicate that Si favors K

+ retention and reduces Na

+ competition, thus enhancing ionic homeostasis under salinity [

18,

40,

41]. Foliar K enrichment is crucial for stomatal regulation, protein synthesis, and turgor maintenance [

42], while higher Ca and Mg levels strengthen membrane integrity, stimulate enzyme activity, support protein and nucleic acid synthesis, and enhance Rubisco performance, contributing to greater salt tolerance and photosynthetic efficiency [

9,

12,

43,

44,

45].

The integration of these nutritional and physiological responses explains the observed increases in plant height (

Figure 6a), root length (

Figure 6b), plant dry mass (

Figure 6c), and Dickson Quality Index (

Figure 6d), particularly under combined Si application. Similar outcomes have been reported in passion fruit under saline conditions, reinforcing Si’s role as an effective mitigating agent [

3,

5,

12,

46]. Improved root growth under Si supply likely enhanced water and nutrient foraging capacity, which together with foliar protection translated into higher biomass accumulation and superior seedling quality indices.

The PCA (

Figure 7) confirmed these trends, revealing that salinity induces a multivariate stress pattern characterized by nutritional, physiological, and growth impairments. The shift of Si-supplemented treatments toward positive PC1 values reflects the simultaneous recovery of nutrition, gas exchange, and growth, highlighting the integrative effect of combined application. The association of soil-applied Si with Mg, P, and Zn in BRS Gigante Amarelo suggests a rhizospheric mechanism that complements rapid foliar absorption and explains the superior performance of combined applications over single routes. This multivariate evidence supports a model in which root- and leaf-targeted Si interventions act through distinct but complementary pathways to restore homeostasis under salinity.

The proximity of combined Si application treatments to RWC and DQI vectors indicates that integrating foliar and root pathways improves water balance and overall seedling quality. In BRS Sol do Cerrado, reduced EL predominated, demonstrating that membrane integrity preservation is a central Si-mediated response, whereas in BRS Gigante Amarelo, nutritional recovery was more prominent. Such cultivar-specific response patterns emphasize the need to tailor Si management to genotype, developmental stage, and stress intensity.

Overall, Si proved to be an effective strategy for alleviating salinity effects in Passiflora edulis, maintaining nutritional balance, cellular integrity, water status, and vegetative growth. Among the evaluated methods, combined Si application achieved the best overall performance by integrating nutritional and physiological responses that resulted in improved growth and seedling quality. However, as the present study was conducted under greenhouse conditions and at the seedling stage, further field trials and long-term assessments are recommended to verify whether the benefits of Si persist during later developmental stages and fruit production. Despite seedlings being a critical phase in yellow passion fruit cultivation, future research should quantify Si uptake and partitioning, perform biochemical analyses, and characterize the expression of Si transporter genes to strengthen the mechanistic understanding of Si-mediated salinity tolerance in this species.

5. Conclusions

Irrigation with saline water (4.0 dS m-1) reduced foliar nutrient concentrations and impaired the morphophysiological performance and seedling quality of Passiflora edulis. However, exogenous silicon application mitigated these adverse effects by enhancing nutrient accumulation, improving gas exchange, and increasing growth and quality, with the combined method (soil + foliar spraying) being the most effective. Genotypic variation was evident, as BRS Gigante Amarelo responded more strongly than BRS Sol do Cerrado, indicating that both cultivar and application route must be considered in Si management during seedling production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.F.P., J.F.d.B.N., A.S.d.M., and E.V.d.M.; methodology, R.d.S.F., R.F.P., A.C.Z.d.S., L.K.S.L., C.d.S.S., J.P.C.D., F.S.F., O.S.M., E.A.G., R.A.S.A., and E.F.d.M.; software, R.F.P., A.C.Z.d.S., C.d.S.S., and E.F.d.M.; validation, R.d.S.F., R.F.P., C.d.S.S., J.F.d.B.N., A.S.d.M., and E.V.d.M.; formal analysis, R.d.S.F., R.F.P., and C.d.S.S.; investigation, R.d.S.F., R.F.P., A.C.Z.d.S., J.F.d.B.N., C.d.S.S., J.P.C.D., F.S.F., O.S.M., E.A.G., R.A.S.A., and E.F.d.M.; resources, A.S.d.M. and E.V.d.M.; data curation, E.F.d.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.d.S.F. and R.F.P.; writing—review and editing, A.C.Z.d.S., J.F.d.B.N., L.K.S.L., C.d.S.S., J.P.C.D., F.S.F., O.S.M., E.A.G., R.A.S.A., A.S.d.M., and E.F.d.M.; visualization, R.F.P.; supervision, R.F.P. and E.F.d.M.; project administration, E.F.d.M.; funding acquisition, A.S.d.M. and E.V.d.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially funded by Paraíba State University (Grant #01/2025), Coordination of Superior Level Staff Improvement – CAPES (Finance Code 02), National Council for Scientific and Technological Development – CNPq (Proc. CNPq 408952/2021-0), and Paraíba State Research Foundation – FAPESQ (Grant #09/2023).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author (E.F.d.M.).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (Embrapa Cerrado) for providing the seeds used in this experiment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DQI |

Dickson Quality Index |

| DAT |

Days after transplanting |

| DAS |

Days after sowing |

| PE |

Polyethylene |

| RWC |

Relative water content |

| EL |

Electrolyte leakage |

| OM |

Organic matter |

| SEB |

Sum of exchangeable bases |

| CEC |

Cation exchange capacity |

| V |

Base saturation percentage |

| BD |

Bulk density |

| PD |

Particle density |

| TP |

Total porosity |

| VWC |

Volumetric water content |

| FC |

Field capacity |

| PWP |

Permanent wilting point |

| EC |

Electrical conductivity |

| gs |

Stomatal conductance |

| A |

CO2 assimilation rate |

| IRGA |

Infrared gas analyzer |

| FM |

Fresh mass |

| TM |

Turgid mass |

| DM |

Dry mass |

| PH |

Plant height |

| RL |

Root length |

| PDM |

Plant dry mass |

| SD |

Stem diameter |

| SDM |

Shoot dry mass |

| RDM |

Root dry mass |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| PCA |

Principal component analysis |

| CV |

Coefficient of variation |

References

- Pereira, Z.C.; Cruz, J.M.A.; Corrêa, R.F.; Sanches, E.A.; Campelo, P.H.; Bezerra, J.A. Passion Fruit (Passiflora spp.) Pulp: A Review on Bioactive Properties, Health Benefits and Technological Potential. Food Res. Int. 2023, 166, 112626. [CrossRef]

- IBGE—Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Passion Fruit Production; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2025. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/explica/producao-agropecuaria/maracuja/br (Accessed on 18 October 2025). (In Portuguese).

- Almeida, C.J.S.; Dantas, J.S.; Mesquita, E.F.; Sousa, C.S.; Soares, V.C.S.; Diniz, J.P.C.; Pereira, R.F.; Lins, L.K.S.; Nogueira, V.F.B.; Silva Filho, I.P. Silicon as a Salt Stress Mitigator in Yellow Passion Fruit Seedlings. Agric. Res. Trop. 2024, 54, e80305. [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.S.; Jesus, O.N.; Sampaio, S.R.; Gonçalves, Z.S.; Soares, T.L; Ferreira, J.R.; Lima, L.K.S. Salt Tolerance Strategy in Passion Fruit Genotypes During Germination and Seedling Growth and Spectrophotometric Quantification of Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2). Sci. Hortic. 2024, 338, 113818. [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.Z.; Pereira, R.F.; Ferreira, R.S.; Alves, S.B.; Sousa, F.S.; Rodrigues, S.S.; Brito Neto, J.F.; Melo, A.S.; Silva, R.M.; Mesquita, E.F. Silicon and Potassium Synergistically Alleviate Salt Stress and Enhance Soil Fertility, Nutrition, and Physiology of Passion Fruit Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1685221. [CrossRef]

- Ayers, R.S.; Westcot, D.W. The Quality of Water in Agriculture, 2nd ed.; UFPB: Campina Grande, Brazil, 1999; 153p. (In Portuguese).

- Alkharabsheh, H.M.; Seleiman, M.F.; Hewedy, O.A.; Battaglia, M.L.; Jalal, R.S.; Alhammad, B.A.; Schillaci, C.; Ali, N.; Al-Doss, A. Field Crop Responses and Management Strategies to Mitigate Soil Salinity in Modern Agriculture: A Review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2299. [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Yang, Y. How Plants Tolerate Salt Stress. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, p. 5914–5934. [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, S.; Nazir, Q.; Saleem, I.; Naz, R.; Azhar, S.; Rafay, M.; Usman, M. Soil Salinity Hinders Plant Growth and Development and Its Remediation: A Review. J. Agric. Res. 2023, 61, 189–200. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Zhou, H. Plant Salt Response: Perception, Signaling, and Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1053699. [CrossRef]

- Diniz, G.L.; Nobre, R.G.; Lima, G.S.; Soares, L.A.A.; Gheyi, H.R. Irrigation With Saline Water and Silicate Fertilization in The Cultivation of ‘Gigante Amarelo’ Passion Fruit. Rev. Caatinga 2021, 34, 199–207. [CrossRef]

- Sá, J.R.; Toledo, F.H.S.F.; Mariño, Y.A.; Soares, C.R.F.S.; Ferreira, E.V.O. Growth and Nutrition of Passiflora edulis Submitted to Saline Stress After Silicon Application. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2021, 43, e-057. [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, L.L.G.; Mesquita, E.F.; Sousa, C.S.; Pereira, R.F.; Diniz, J.P.C.; Melo, A.S.; Alencar, R.S.; Dias, G.F.; Soares, V.C.S.; Mesquita, F.O.; Pires, J.P.M.M.; Rodrigues, S.S.; Lins, L.K.S.; Alves, A.S.; Araújo, K.T.A.; Costa Ferraz, P.S. Foliar Silicon Alleviates Water Deficit in Cowpea by Enhancing Nutrient Uptake, Proline Accumulation, and Antioxidant Activity. Plants 2025, 14, 1241. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, A.L.; Muneer, S.; Kim, Y.H.; Al-Rawahi, A.; Al-Harrasi, A. Silicon and Salinity: Crosstalk in Crop-Mediated Stress Tolerance Mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1429. [CrossRef]

- Farouk, S.; Elhindi, K.M.; Alotaibi, M.A. Silicon Supplementation Mitigates Salinity Stress on Ocimum basilicum L. Via Improving Water Balance, Ion Homeostasis, and Antioxidant Defense System. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 206, 111396. [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, V.; Dehnavi, M.M.; Balouchi, H.; Yadavi, A.; Hamidian, M. Silicon Can Improve Nutrient Uptake and Performance of Black Cumin Under Drought and Salinity Stresses. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2022, 54, 297–310. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, A. Interaction of Silicon With Cell Wall Components in Plants: A Review. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2023, 15, 480–497. [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, P.; Amiri, J.; Mahna, N.; Naseri, L.; Sadaghiani, M.R. Silicon-Induced Mitigation of Salt Stress in GF677 and GN15 RootStocks: Insights Into Physiological, Biochemical, and Molecular Mechanisms. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 719. [CrossRef]

- Greger, M.; Landberg, T.; Vaculík, M. Silicon Influences Soil Availability and Accumulation of Mineral Nutrients in Various Plant Species. Plants 2018, 7, 41. [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, J.; Kostic, L.; Bosnic, P.; Kirkby, E.A.; Nikolic, M. Interactions of Silicon With Essential and Beneficial Elements in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 23, 697592. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, P; Subedi, S; Khan, A.L.; Chung, Y.S.; Kim, Y. Silicon Effects on The Root System of Diverse Crop Species Using Root Phenotyping Technology. Plants 2021, 10, 885. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.F.; Yamaji, N. A Cooperative System of Silicon Transport in Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 435–442. [CrossRef]

- Mitani-Ueno, N.; Yamaji, N.; Huang, S.; Yoshioka, Y.; Miyaji, T.; Ma, J.F. A Silicon Transporter Gene Required for Healthy Growth of Rice on Land. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6522. [CrossRef]

- Verma, K.K.; Song, X.-P.; Li, D.-M.; Singh, M.; Wu, J.-M.; Singh, R.K.; Sharma, A.; Zhang, B.-Q.; Li, Y.-R. Silicon and Soil Microorganisms Improve Rhizospheric Soil Health With Bacterial Community, Plant growth, Performance and Yield. Plant Signal. Behav. 2022, 17, 2104004. [CrossRef]

- Dutra, A.F.; Leite, M.R.L.; Melo, C.C.F.; Amaral, D.S.; Silva, J.L.F., Prado, R.M.; Piccolo, M.S.; Miranda, R.S.; Silva Júnior, G.B.; Sousa, T.K.S.A.; Mendes, L.W.; Araújo, A.S.F.; Zuffo, A.M.; Alcântara Neto, F. Soil and Foliar Si Fertilization Alters Elemental Stoichiometry and Increases Yield of Sugarcane Cultivars. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16040. [CrossRef]

- Babu, P.M.; Thakuria, D.; Majumdar, S.; Kalita, H.C. Sources and Application Methods of Silicon For Rice in Acid Soil. Silicon 2025, 17, 499–515. [CrossRef]

- Baioui, R.; Hidri, R.; Zouari, S.; Hajji, M.; Falouti, M.; Bounaouara, F.; Borni, M.; Hamzaoui, A. H.; Abdelly, C.; Zorrig, W.; Slama, I. Foliar Application of Silicon: An Innovative and Effective Strategy for Enhancing Tomato Yield in Hydroponic Systems. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1553. [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, M.J.; Gianello, C.; Bissani, C.A.; Bohnen, H.; Volkweiss, S.J. Soil, Plant, and Other Material Analysis, 2nd ed.; UFRS: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1995; 174p. (In portuguese).

- Meneghetti, A.M. Manual of Procedures for Sampling and Chemical Analysis of Plants, Soil, and Fertilizers; EDUTFPR: Curitiba, Brazil, 2018; 252p. (In portuguese).

- Dickson, A.; Leaf, A.L.; Hosner, J.F. Quality Appraisal of White Spruce and White Pine Seedling Stock in Nurseries. For. Chron. 1960, 36, 10–13. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment For Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria; 2025. Available online: https://www.r-project.org (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Liu, C.; Jiang, X.; Yuan, Z. Plant Responses and Adaptations to Salt Stress: A Review. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1221. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Shi, H.; Yang, Y.; Feng, X.; Chen, X.; Xiao, F.; Lin, H.; Guo, Y. Insights Into Plant Salt Stress Signaling and Tolerance. J. Genet. Genomics 2024, 51, 16–34. [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.; Ramzan, M.; Naz, G.; Ali, L.; Danish, S.; Ansari, M.J.; Salmen, S.H. Effect of Silicon Nanoparticle-Based Biochar on Wheat Growth, Antioxidants and Nutrients Concentration Under Salinity Stress. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 6380. [CrossRef]

- Wadas, W.; Kondraciuk, T. The Role of Foliar-Applied Silicon in Improving The Growth and Productivity of Early Potatoes. Agriculture 2025, 15, 556. [CrossRef]

- Attia, E.A.; Elhawat, N. Combined Foliar and Soil Application of Silica Nanoparticles Enhances the Growth, Flowering Period and Flower Characteristics of Marigold (Tagetes erecta L.). Sci. Hortic. 2021, 282, 110015. [CrossRef]

- Dabravolski, S.A.; Isayenkov, S.V. The Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms of Silicon Action in Salt Stress Amelioration. Plants 2024, 13, 525. [CrossRef]

- Souri, Z.; Khanna, K.; Karimi, N.; Ahmad, P. Silicon and Plants: Current Knowledge and Future Prospects. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 40, 906–925. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.; Chen, S. Plant Silicon-Cell Wall Complexes: Identification, Model of Covalent Bond Formation and Biofunction. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 155, 13–19. [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Fan, X.; Zheng, W.; Gao, Z.; Yin, C.; Li, T.; Liang, Y. Silicon Alleviates Salt Stress-Induced Potassium Deficiency by Promoting Potassium Uptake and Translocation in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Plant Physiol. 2021, 258, 153379. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.Z.; Odeibat, H.A.; Ahmad, R.; Gatasheh, M.K.; Shahzad, M.; Abbasi, A.M. Low Apoplastic Na+ and Intracellular Ionic Homeostasis Confer Salinity Tolerance Upon Ca2SiO4 Chemigation in Zea mays L. Under Salt Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1268750. [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, H.; Jamil, M.; Haq, A.; Ali, S.; Ahmad, R.; Malik, Z.; Parveen, Z. Salt Stress Manifestation on Plants, Mechanism of Salt Tolerance and Potassium Role in Alleviating It: A Review. Zemdirb. Agric. 2016, 103, 229–238. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Han, W.; Gong, H. Beneficial Effects of Silicon in Alleviating Salinity Stress of Tomato Seedlings Grown Under Sand Culture. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2015, 37. [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Li, S.; Gao, L.; Sun, C.; Hu, J.; Ullah, A.; Gao, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, D.; Cao, W.; Tian, Z.; Dai, T. Magnesium Application Promotes Rubisco Activation and Contributes to High-Temperature Stress Alleviation in Wheat During the Grain Filling. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 675582. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Zhang, B.; Bozdar, B.; Chachar, S.; Rai, M.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Hayat, F.; Chachar, Z.; Tu, P. The Power of Magnesium: Unlocking the Potential for Increased Yield, Quality, and Stress Tolerance of Horticultural Crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1285512. [CrossRef]

- Souza, T.M.A.; Mendonça, V.; Sá, F.V.S.; Silva, M.J.; Dourado, C.S.T. Calcium Silicate as Salt Stress Attenuator in Seedlings of Yellow Passion Fruit cv. BRS GA1. Rev. Caatinga 2020, 33, 509–517. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Mean air temperature and relative humidity recorded during the growth period of yellow passion fruit seedlings in the greenhouse.

Figure 1.

Mean air temperature and relative humidity recorded during the growth period of yellow passion fruit seedlings in the greenhouse.

Figure 2.

Experimental schematic: seedlings of two Passiflora edulis cultivars (a); sowing in trays (b); transplanting into polyethylene bags (c); saline irrigation management (d); silicon applications under salt stress (e); and evaluated plant traits (f). PE – polyethylene; DAS – days after sowing; DAT – days after transplanting; RWC – relative water content; EL – electrolyte leakage; DQI – Dickson Quality Index.

Figure 2.

Experimental schematic: seedlings of two Passiflora edulis cultivars (a); sowing in trays (b); transplanting into polyethylene bags (c); saline irrigation management (d); silicon applications under salt stress (e); and evaluated plant traits (f). PE – polyethylene; DAS – days after sowing; DAT – days after transplanting; RWC – relative water content; EL – electrolyte leakage; DQI – Dickson Quality Index.

Figure 3.

Foliar contents of C (a), N (b), P (c), K (d), Ca (e), and Mg (f) in seedlings of two Passiflora edulis cultivars under irrigation water salinity levels and silicon application methods. Uppercase letters compare management conditions (salinity and silicon application methods) within each cultivar (Scott-Knott test, p ≤ 0.05), and lowercase letters compare cultivars within each management condition (Student’s t-test, p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 5). CV – coefficient of variation.

Figure 3.

Foliar contents of C (a), N (b), P (c), K (d), Ca (e), and Mg (f) in seedlings of two Passiflora edulis cultivars under irrigation water salinity levels and silicon application methods. Uppercase letters compare management conditions (salinity and silicon application methods) within each cultivar (Scott-Knott test, p ≤ 0.05), and lowercase letters compare cultivars within each management condition (Student’s t-test, p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 5). CV – coefficient of variation.

Figure 4.

Foliar contents of Fe (a), Zn (b), and Mn (c) in seedlings of two Passiflora edulis cultivars under irrigation water salinity levels and silicon application methods. Uppercase letters compare management conditions (salinity and silicon application methods) within each cultivar (Scott-Knott test, p ≤ 0.05), and lowercase letters compare cultivars within each management condition (Student’s t-test, p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 5). CV – coefficient of variation.

Figure 4.

Foliar contents of Fe (a), Zn (b), and Mn (c) in seedlings of two Passiflora edulis cultivars under irrigation water salinity levels and silicon application methods. Uppercase letters compare management conditions (salinity and silicon application methods) within each cultivar (Scott-Knott test, p ≤ 0.05), and lowercase letters compare cultivars within each management condition (Student’s t-test, p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 5). CV – coefficient of variation.

Figure 5.

Stomatal conductance (gs) (a), CO2 assimilation rate (A) (b), relative water content (c), and electrolyte leakage (d) in seedlings of two Passiflora edulis cultivars under irrigation water salinity levels and silicon application methods. Uppercase letters compare management conditions (salinity and silicon application methods) within each cultivar (Scott-Knott test, p ≤ 0.05), and lowercase letters compare cultivars within each management condition (Student’s t-test, p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 5). CV – coefficient of variation.

Figure 5.

Stomatal conductance (gs) (a), CO2 assimilation rate (A) (b), relative water content (c), and electrolyte leakage (d) in seedlings of two Passiflora edulis cultivars under irrigation water salinity levels and silicon application methods. Uppercase letters compare management conditions (salinity and silicon application methods) within each cultivar (Scott-Knott test, p ≤ 0.05), and lowercase letters compare cultivars within each management condition (Student’s t-test, p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 5). CV – coefficient of variation.

Figure 6.

Plant height (a), root length (b), plant dry mass (c), and Dickson Quality Index (DQI) (d) in seedlings of two Passiflora edulis cultivars under irrigation water salinity levels and silicon application methods. Uppercase letters compare management conditions (salinity and silicon application methods) within each cultivar (Scott-Knott test, p ≤ 0.05), and lowercase letters compare cultivars within each management condition (Student’s t-test, p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 5). CV – coefficient of variation.

Figure 6.

Plant height (a), root length (b), plant dry mass (c), and Dickson Quality Index (DQI) (d) in seedlings of two Passiflora edulis cultivars under irrigation water salinity levels and silicon application methods. Uppercase letters compare management conditions (salinity and silicon application methods) within each cultivar (Scott-Knott test, p ≤ 0.05), and lowercase letters compare cultivars within each management condition (Student’s t-test, p ≤ 0.05). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (n = 5). CV – coefficient of variation.

Figure 7.

PCA clustering of nutritional and morphophysiological traits in Passiflora edulis seedlings under salinity and silicon application treatments. The colors indicate the treatment groups formed by clustering in the PCA. Arrows represent the contribution and direction of each variable to the principal components. RWC – relative water content; EL – electrolyte leakage; gs – stomatal conductance; A – CO2 assimilation rate; PH – plant height; PDM – plant dry mass; DQI – Dickson quality index; SC – BRS Sol do Cerrado; GA – BRS Gigante Amarelo; Ctrl – control (1.2 dS m-1); Salt – salt stress (4.0 dS m-1); Salt.Si.Soil – salt stress + Si applied to soil; Salt.Si.Foliar – Si applied by foliar spraying; Salt.Si.Combined – salt stress + Si applied to soil and by foliar spraying.

Figure 7.

PCA clustering of nutritional and morphophysiological traits in Passiflora edulis seedlings under salinity and silicon application treatments. The colors indicate the treatment groups formed by clustering in the PCA. Arrows represent the contribution and direction of each variable to the principal components. RWC – relative water content; EL – electrolyte leakage; gs – stomatal conductance; A – CO2 assimilation rate; PH – plant height; PDM – plant dry mass; DQI – Dickson quality index; SC – BRS Sol do Cerrado; GA – BRS Gigante Amarelo; Ctrl – control (1.2 dS m-1); Salt – salt stress (4.0 dS m-1); Salt.Si.Soil – salt stress + Si applied to soil; Salt.Si.Foliar – Si applied by foliar spraying; Salt.Si.Combined – salt stress + Si applied to soil and by foliar spraying.

Table 1.

Chemical and physical characteristics of the soil and cattle manure used in the experiment.

Table 1.

Chemical and physical characteristics of the soil and cattle manure used in the experiment.

| Chemical features of the soil |

| pH |

OM |

P |

K+ |

Na+ |

Ca2+ |

Mg2+ |

Al3+ |

H+ + Al3+ |

SEB |

CEC |

V |

| 1:2.5 |

g kg-1

|

mg dm-3

|

..................................................cmolc dm-3 ..................................................... |

% |

| 6.00 |

13.58 |

16.63 |

0.08 |

0.05 |

1.09 |

1.12 |

0.00 |

1.24 |

2.34 |

3.58 |

65.36 |

| Physical features of the soil |

| Sand |

Silt |

Clay |

BD |

PD |

TP |

VWCFC |

VWCPWP |

Textural class |

| ……….g kg-1………. |

…..g cm-3….. |

...........................%........................... |

– |

| 546.00 |

230.00 |

224.00 |

1.53 |

2.61 |

41.38 |

23.33 |

11.72 |

SCL |

| Chemical features of the cattle manure |

| pH |

EC |

OM |

C |

N |

C/N |

P |

K+ |

Ca2+ |

Mg2+ |

| 1:2.5 |

dS m-1

|

dag kg-1

|

…..g kg-1….. |

- |

….……..……g kg-1………...…… |

| 7.70 |

6.09 |

36.20 |

166.90 |

13.90 |

12.00 |

3.20 |

18.70 |

16.20 |

6.10 |

| S |

CEC |

B |

Fe |

Cu |

Mn |

Zn |

Si |

Na+ |

| g kg-1

|

mmolc dm-3

|

mg kg-1

|

..….…….….……mg kg-1….…….…….….. |

…..g kg-1….. |

| 2.50 |

133.90 |

14.80 |

11,129.90 |

19.30 |

491.40 |

65.30 |

12.50 |

3.50 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).