1. Introduction

To explain entanglement, it is crucial that the states of an entangled system are defined before measurement and are not random. Otherwise, there are no correlations between the measurement results on both sides of the entangled system. Various approaches, including Bell’s, assume that a hidden parameter must be introduced for a realistic explanation of entanglement, which is assigned to both partner particles at the source of an entangled photon pair [

1,

2] . This was also performed in [

3,

4] and allowed the development of models that correctly explained quantum correlations. This is sufficient to disprove Bell’s theorem, which states that a realistic local model for predicting quantum correlations is impossible. Although there are a number of approaches that consider nonlocality as a physical phenomenon of entangled particles, none has so far been completely convincing [

5]. There are also doubts that quantum correlations necessarily result in nonlocal behavior [

6].

In this study, a new approach is proposed that does not require hidden variables and still predicts defined states before a measurement. This is achieved by a model describing the entirety of all possible states, from which the measured state is extracted by selection before the measurement. This model is only valid for particles whose quantum states are indistinguishable and can therefore assume common states. The model is described using four model assumptions (italics). Both entangled and non-entangled photons in superposition were considered. This model also explains the measurement results obtained using a Mach-Zehnder interferometer.

2. Method – Model Description

Model assumption MA1 (describing superposition)

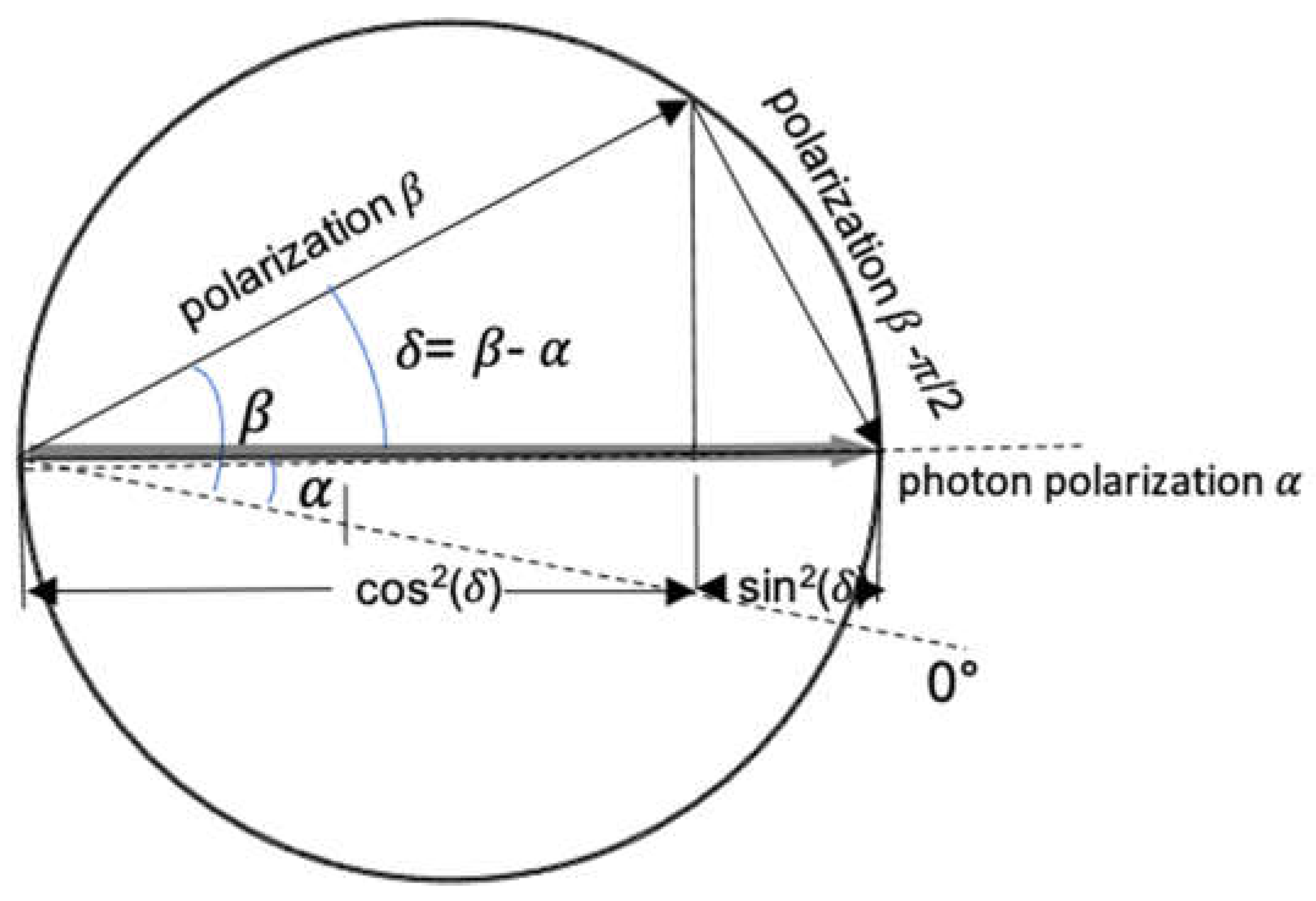

A photon beam with polarization α can be regarded as a mixture of two indistinguishable photon beams, one with polarization β and share cos2(β-α) and the other with polarization β-π/2 and share sin2(β-α) for arbitrary α and β. A polarizer set to β/β-π/2 selects the photon beams with polarization β and β-π/2 from the original beam. All pairs of beams are equivalent.

Thus MA1 reproduces Malu’s law. From the quantum perspective, a system with the polarization α can be regarded as a superposition of two systems with polarizations β and β-π/2. MA1 indicates that the projective measurement selects states that already exist. All individual photons that pass through a polarizer are polarized before the measurement. However, owing to the indistinguishability of photons in a superposition, it is not possible to predict which photon will enter which exit of a polarizer.

Figure 1 geometrically shows how a photon beam of polarization α can be seen as a mixture of two indistinguishable photon beams with polarization β and β-π/2 for arbitrary α and β. Mixtures of indistinguishable states in R3 are equivalent to superposition in the Hilbert space. This is because the proportions of the different components are the same in both the representations. Born’s rule is already included in the model, whereas it must be added to the quantum state in Hilbert space to predict the probabilities of the measurement results.

Complementary to MA1 we define for arbitrary α and β

Model assumption MA2:(describing the absolute value of the common polarization)

Indistinguishable photon beams with fractions cos2(β-α) of polarizationβ and sin2(β-α) of polarizationβ -π/2 assume the common polarizationα or -α.

The sign of the common polarization on both sides is given for Bell states by model assumption MA3.

Model assumption MA3:(controlling the sign of the common polarization)

Each Bell state is a mixture of indistinguishable constituent photon pairs in equal shares whose components have the same polarization 0° or 90° forΦ+ andΦ- and an offset ofπ/2 forΨ+ andΨ-. The constituent photon pairs make up the initial state. From the conservation of the spin angular momentum we obtain forΨ- andΦ+ the same sign for the polarization of the beams, and forΨ+ andΦ- the opposite sign in the original coordinate system.

This is described in detail in [

4]. It has been shown that rotational invariance and conservation of spin angular momentum are equivalent and denote the same physical situation. From these results entanglement swapping and teleportation were derived.

3. Results – Calculating Probabilities of Matching Events with Entangled Photons

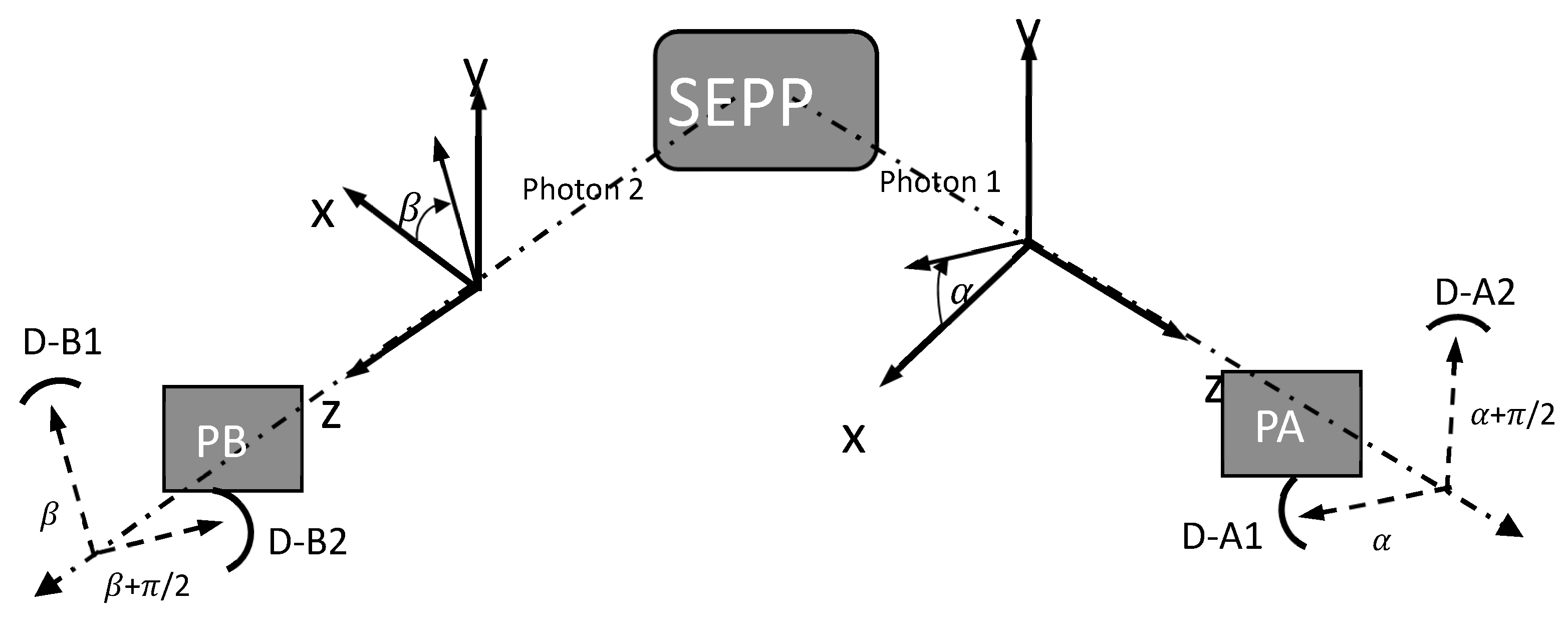

Figure 2 shows the coordinate systems and nomenclature of experiments with polarization-entangled photons [

4].

Entangled photons on either side can be understood as a mixture of indistinguishable horizontally polarized and vertically polarized photon beams in equal parts. We set PA to the value α. Owing to MA1, all photons selected by PA had the polarization α before the measurement. The fraction of horizontally polarized photons contributing to the beam with polarization α is cos2(0-α) = cos2(α) and the fraction of vertically polarized photons is cos2(π/2-α)= sin2(α).

For the singlet state, we obtain the corresponding beam of the partner photons on side B from the initial conditions. The fraction of horizontally polarized photons on side B matches that of vertically polarized photons on side A, that is sin2(α). The fraction of vertically polarized photons on side B is cos2(α), matching the fraction of horizontally polarized photons on side A. From MA2 and MA3, we obtain that the common polarization of the partner photons on side B is α+π/2. (offset of π/2 for Ψ- and the same sign of the polarization)

Now we set PB to β. From MA1, we obtain that the fraction of photons with polarization β contributing to the photon flux with polarization α+π/2 is cos

2 (β-α-π/2 ) = sin

2(β-α). This is the probability of matching events at polarizer PA and polarizer PB. The expectation value for a joint measurement with photon 1 detected behind detector PA at

α and partner photon 2 detected behind detector PB at

β is as obtained from ([

3], eq. (13))

This matches the predictions of quantum mechanics. As in Ref. [

4], this also explains entanglement swapping and teleportation.

4. Results – Explaining the Mach-Zehnder-Interferometer

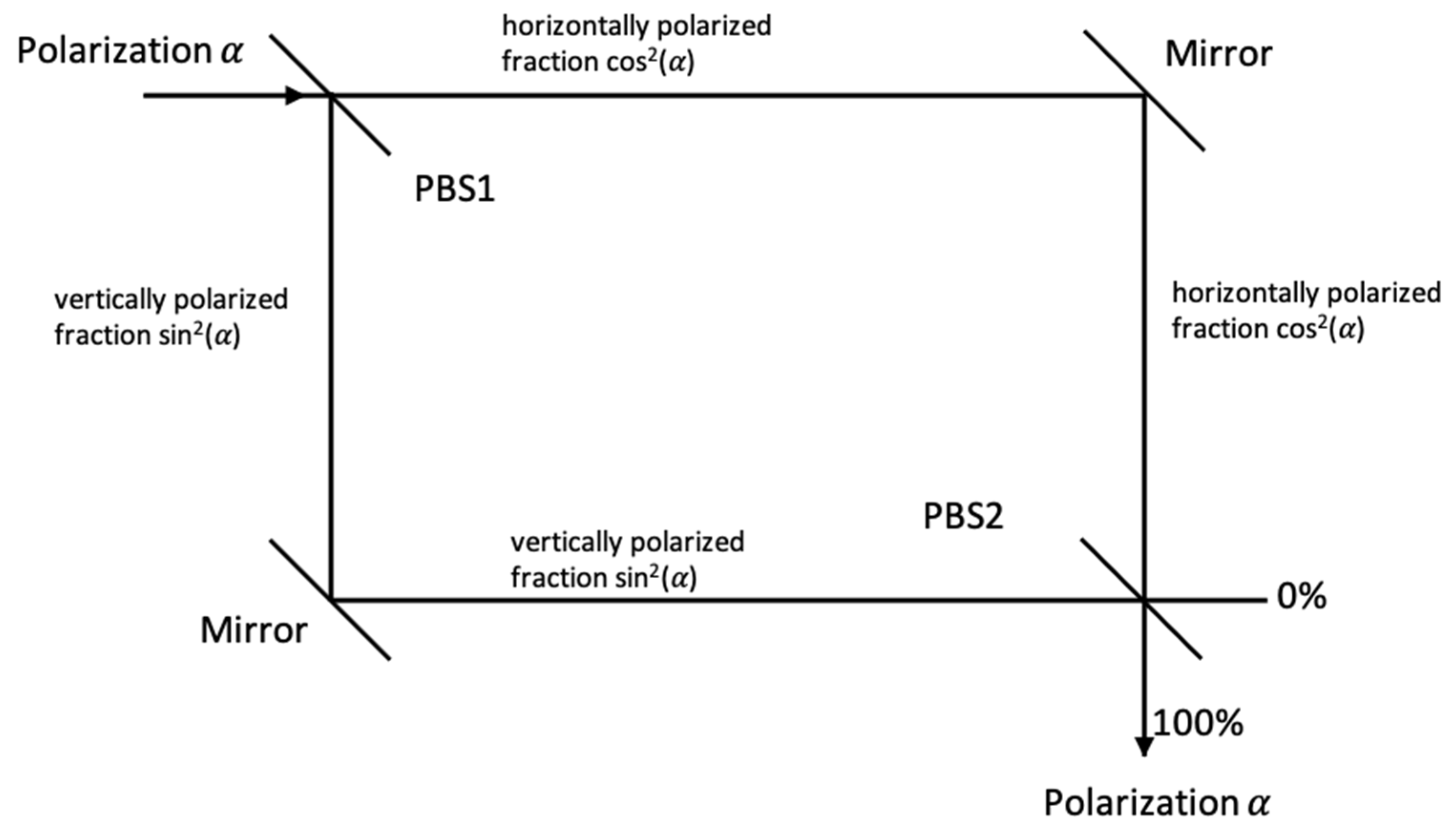

The model also explains the Mach-Zehnder interferometer (MZI) with polarizing beam splitters (PBS) without interference, as shown in

Figure 3. In a Mach–Zehnder interferometer, a photon beam with polarization α is split into a beam of horizontally polarized photons with a fraction of cos

2(α) and a beam of vertically polarized photons with a fraction of sin

2(α) [

7]. At the output, the two separate photon beams are recombined in the PBS, and the original polarization from the input is restored.

Model assumption MA4:(controlling the sign of the output of a MZI without interference)

The vertically polarized photons carry the sign ofα. When generating the common polarizationα, the sign ofα is retained. This is achieved by maintaining the sign of the phase difference between the left- and the right-polarized components of a linearly polarized photon beam.

The relationship between the state of linearly polarized photons and the state of circularly polarized photons is

From eq. (2), we obtain the phase difference between the left and right polarized components as 2α. Thus, α and the phase difference exhibit the same sign. This sign is retained by the vertically polarized photon eqs. (4) and (5), respectively. For α > 0 eq. (4) applies and for α < 0 eq. (5) applies.

The input beam on the first PBS (PBS1) may have polarization direction α. According to MA1, this beam of photons with polarization α is a mixture of indistinguishable beams of photons of horizontal polarization with fraction cos2(α) and vertical polarization with fraction sin2(α). Owing to MA4, the sign of α is retained by the vertically polarized photons. Horizontally polarized photons are transmitted by PBS1, whereas vertically polarized photons are reflected by PBS1. The mirrors do not change the polarization. The input of the second PBS (PBS2) are horizontally polarized photons with fraction cos2(α) and vertically polarized photons with fraction sin2(α). Horizontally polarized photons are transmitted, whereas vertically polarized photons are reflected by PBS2. Therefore, these photons both reach the same exit of PBS2 and are indistinguishable. Thus, they have a uniform polarization direction, α according to MA2 and MA4.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

It could be shown that superposition can be understood as the entirety of all mixtures of indistinguishable perpendicularly polarized photon beams with arbitrary polarization. The photon beams, whose polarization correspond to the position of the polarizer, are filtered out by selection with a polarizer. Each photon of a selection has a specific polarization state before the measurement, that one that corresponds to the polarizer position. This reflects Malus’ law. From a quantum perspective, projective measurement selects states that already exist.

Superposition as a mixture of indistinguishable photon beams can be demonstrated experimentally using a Mach-Zehnder interferometer. This explains how the polarization of the input state reappears at the output in a Mach-Zehnder interferometer. It also uses the fact that a mixture of indistinguishable, perpendicularly polarized photon beams assume the common polarization, which results from the mixing ratio. The quantum world differs from the classical world in particular in that there are indistinguishable particles in the quantum world, which then assume common properties, which is not possible in the classical world.

When the polarizer setting is defined incompatible polarization states of a photon beam do not exist simultaneously; therefore, there is no collapse of the wave function and the many-worlds theory is obsolete. The behavior of photons is predetermined, but not predictable. This is because of the indistinguishability of the photons.

From the model point of view there are also no nonlocal effects with the entangled photons. This is because the physical states of the photons were defined before each measurement. The connection between the two branches of a Bell experiment arises from the conservation of spin angular momentum and is mediated by the mixing ratio of horizontally and vertically polarized photons on each side. This does not require additional hidden variables and makes Bell’s theorem obsolete. Bell’s theorem deals with the question of whether hidden parameters can explain the quantum correlations in entangled particles locally [

1].

Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen (EPR) [

8] first questioned whether the state function in quantum physics is complete. From the perspective of the model (MA1), it can be concluded that a photon beam with a certain polarization can be understood as a mixture of orthogonally polarized, indistinguishable photon beams. All the pairs of orthogonally polarized photons are equivalent. This implies that the state function of a photon beam with a certain polarization describes all possible mixtures of orthogonally polarized photon beams (MA1). During the measurement, one of these is selected by adjusting a polarizer. This is the role of the observer. This fact has not been modeled by quantum theory. In this respect, the model supplements quantum theory, as called for by EPR. No hidden variables are required. The model does not describe individual systems, but rather ensembles of photon beams. This view corresponds with Einstein’s opinion [

9].

The model also defuses the controversy between Bohr and Einstein regarding the interpretation of quantum physics. Bohr was of the opinion that the wave function is complete and contains all the information we can know about the system [

9]. According to MA1, all possible states are included in the model. This confirms Bohr’s view. However, the finally measured states are filtered out by selection through a polarizer, that is, the states are already present before the measurement and are not randomly generated during the measurement. This confirms Einstein’s view, who is quoted as saying: “God does not play dice.”

The presented model does not replace QM but confirms it and provides statements about the predetermination and locality of quantum states that QM does not provide. The model is based exclusively on physical principles and does not require hidden variables. Thus, the paper presented here is a conclusively substantiated contribution to the interpretation of quantum mechanics.

Author Contribution

E.M is the only author and solely responsible for the entire manuscript

Funding

No funds, grants or other support was received.

Ethical Compliance

No human participants are involved

Data Access Statement

No Data were produced

Competing Interests

The author has no financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Bell, J.S. , On The Einstein Podolsky Rosen Paradox. Physics (Long Island City N.Y.), 1964, 1, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, M. , Genovese, M. and Shimony, A., “Bell’s Theorem”. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Muchowski, E. On a contextual model refuting Bell's theorem. EPL (Europhysics Lett. 2021, 134, 10004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchowski, E. , What connects entangled photons? International Journal of Quantum Foundations 2023, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, R.B. Nonlocality claims are inconsistent with Hilbert-space quantum mechanics. Phys. Rev. A 2020, 101, 022117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annila, A.; Wikström, M. Quantum entanglement and classical correlation have the same form. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2024, 139, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondani, M. , 2021 J. Ser. 1929 01 2055. [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. , Podolsky B., Rosen N., Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete? Phys. Rev. 1935, 47, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist by Arthur Schilpp, Editor (Open Court Press, 1969) Third Edition, page 671.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).