Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

13 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

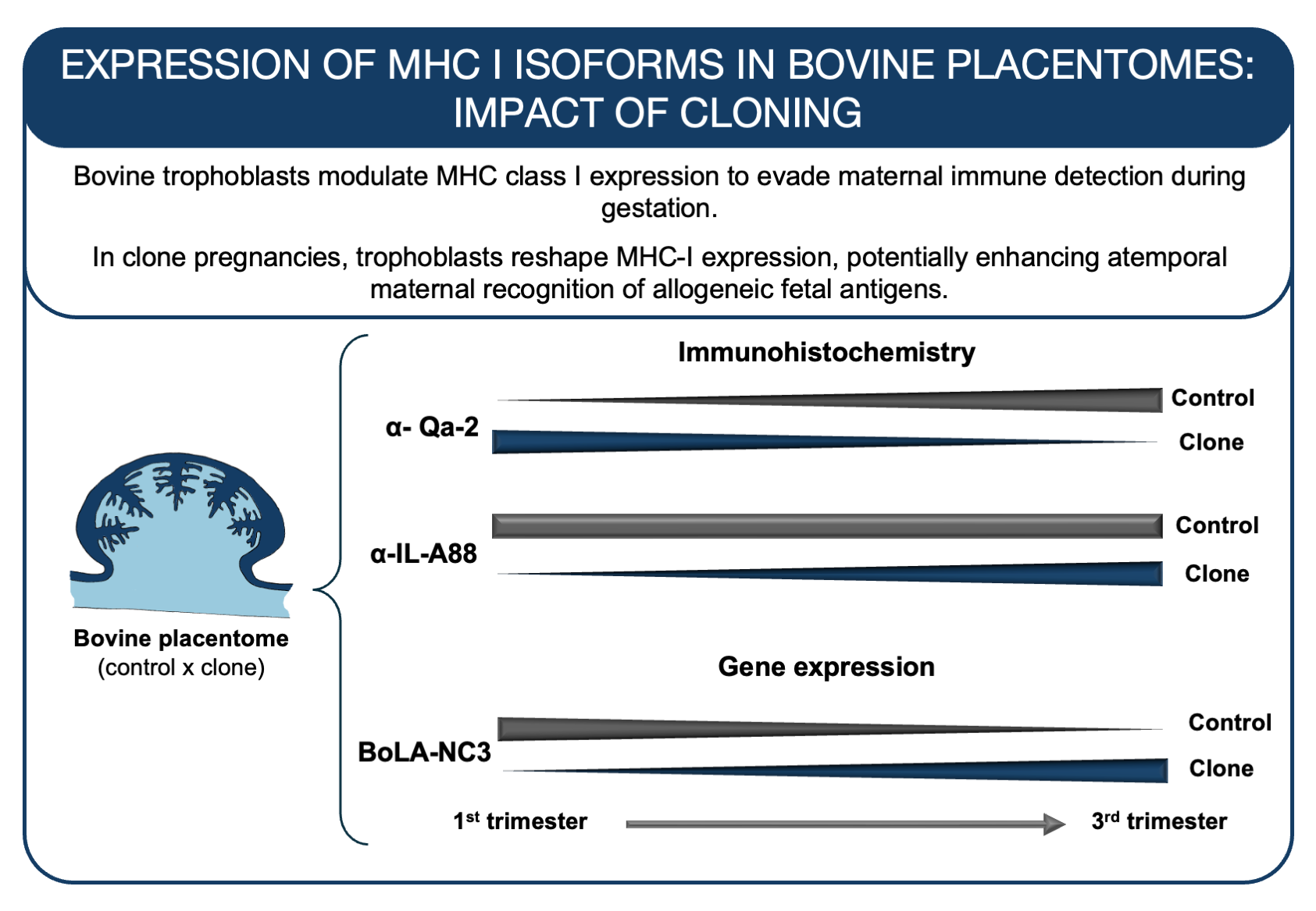

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

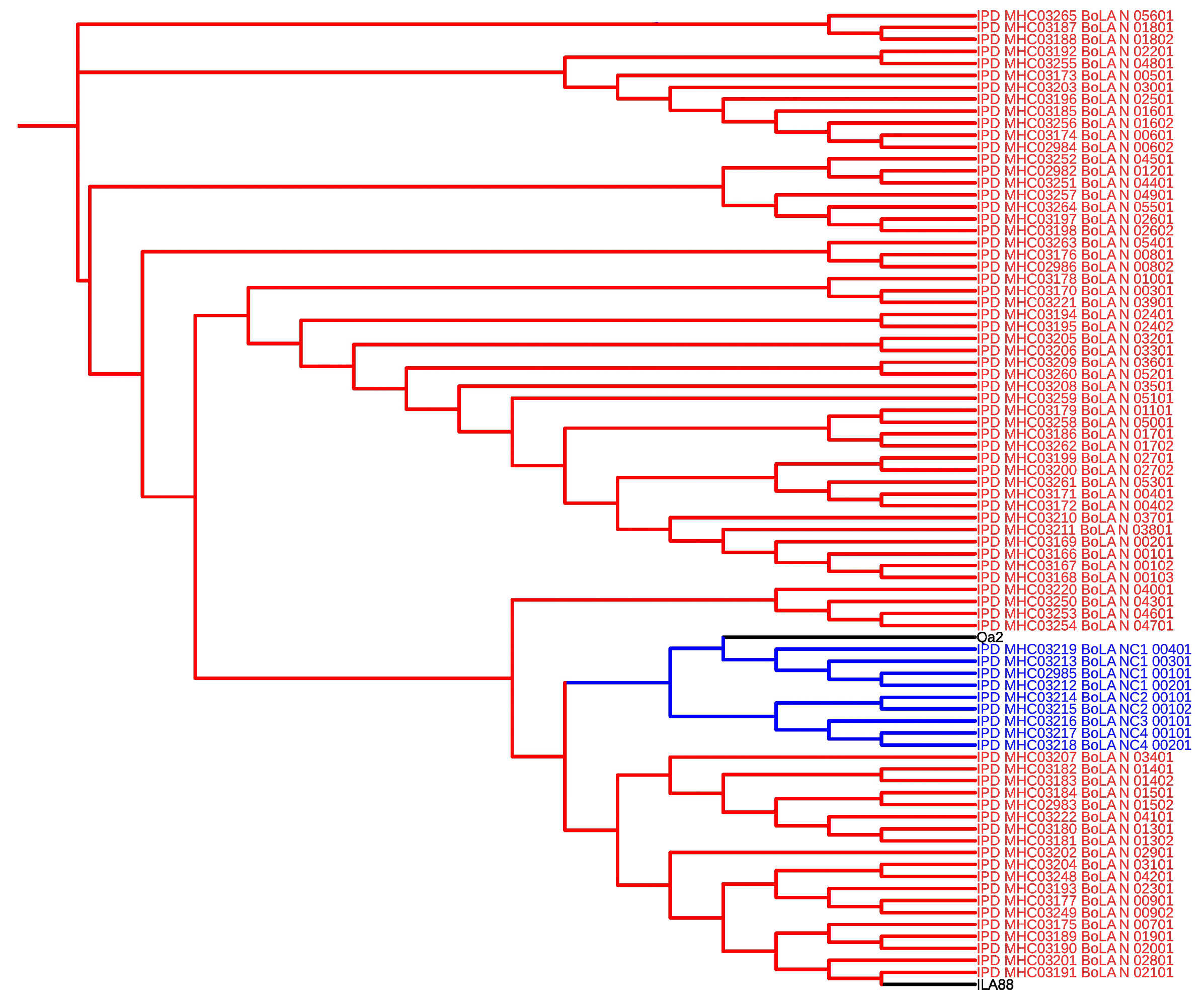

3.1. Qa-2 and IL-A88 Antibodies Recognizes Putative Soluble MHC-I Proteins

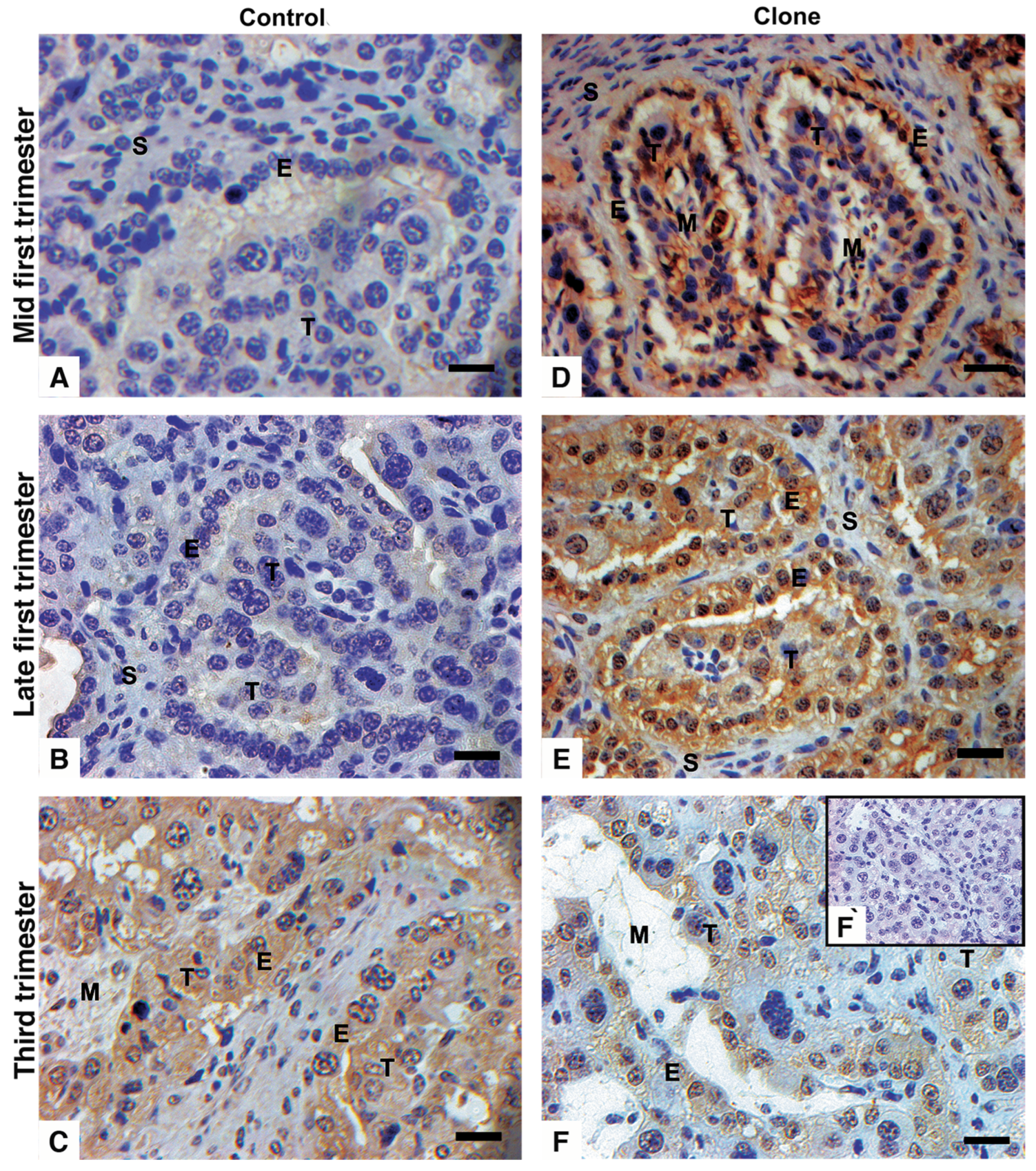

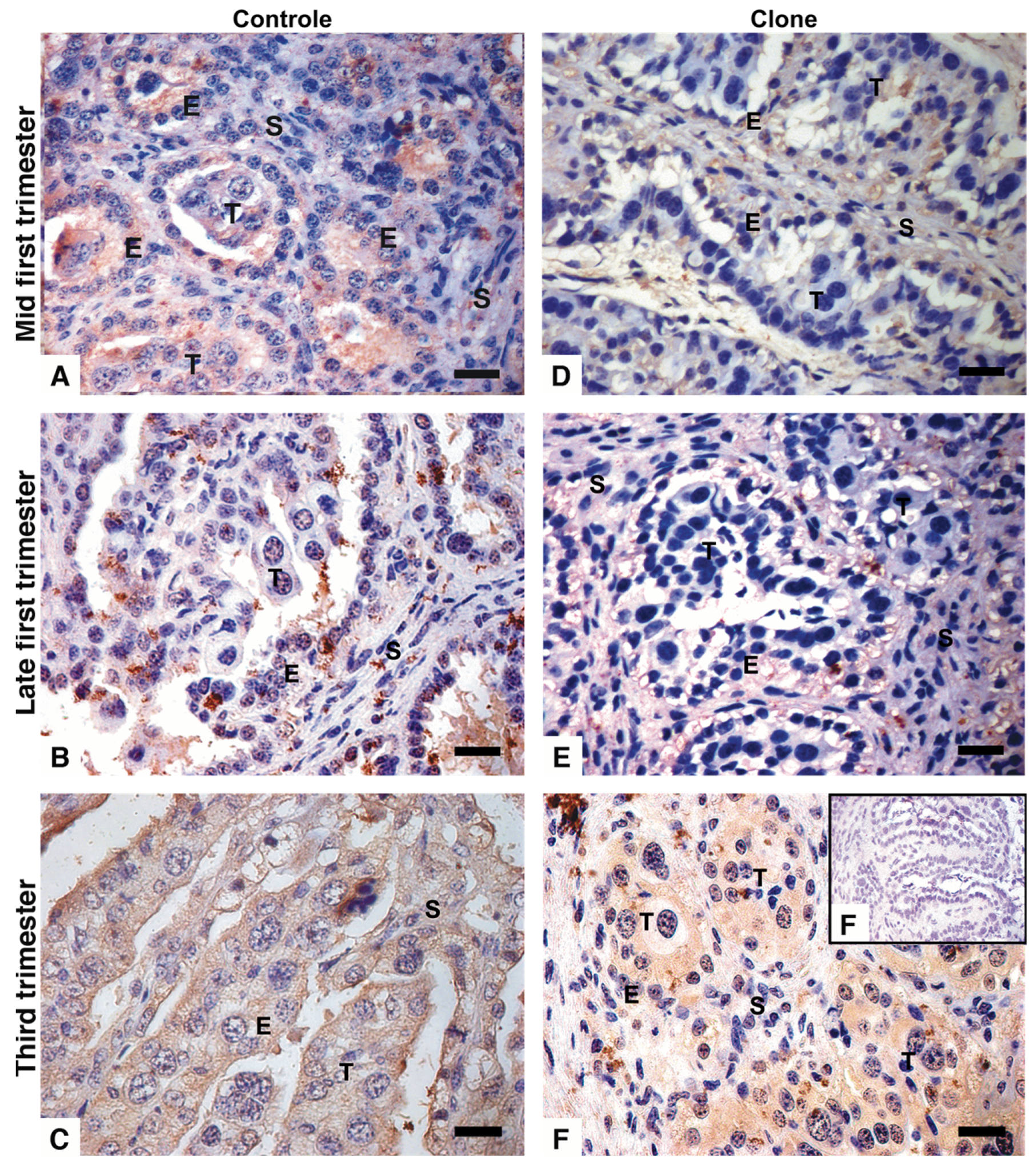

3.2. Immunohistochemistry with Distinct Pattern Between Qa2 and IL-A88 Antibodies

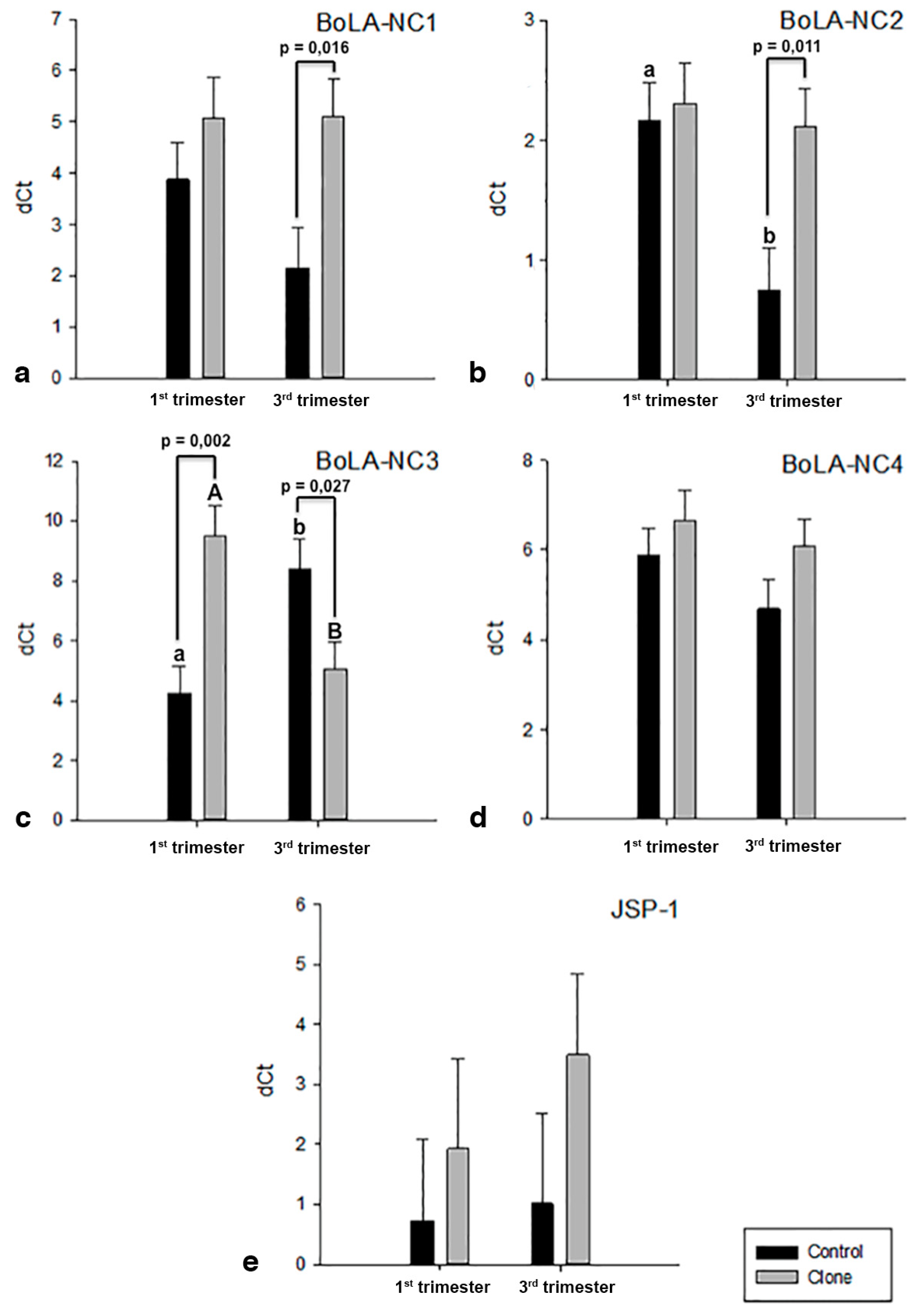

3.3. Expression and Regulation of MHC I Gene Isoforms

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zumkeller, W. Current Topic: The Role of Growth Hormone and Insulin-like Growth Factors for Placental Growth and Development. Placenta 2000, 21, 451–467. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, R.; Melchiorri, L.; Stignani, M.; Baricordi, O.R. HLA-G Expression Is a Fundamental Prerequisite to Pregnancy. Hum Immunol 2007, 68, 244–250. [CrossRef]

- Moffett-King, A. Natural Killer Cells and Pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol 2002, 2, 656–663. [CrossRef]

- Heemskerk, B.; Lankester, A.C.; van Vreeswijk, T.; Beersma, M.F.C.; Claas, E.C.J.; Veltrop-Duits, L.A.; Kroes, A.C.M.; Vossen, J.M.J.J.; Schilham, M.W.; van Tol, M.J.D. Immune Reconstitution and Clearance of Human Adenovirus Viremia in Pediatric Stem-Cell Recipients. J Infect Dis 2005, 191, 520–530. [CrossRef]

- Bulmer, J.N.; Johnson, P.M. Antigen Expression by Trophoblast Populations in the Human Placenta and Their Possible Immunobiological Relevance. Placenta 1985, 6, 127–140. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.S.; Petroff, M.G.; McIntire, R.H.; Ober, C. HLA-G and Immune Tolerance in Pregnancy. FASEB Journal 2005, 19, 681–693. [CrossRef]

- Steinborn, A.; Varkonyi, T.; Scharf, A.; Bahlmann, F.; Klee, A.; Sohn, C. Early Detection of Decreased Soluble HLA-G Levels in the Maternal Circulation Predicts the Occurrence of Preeclampsia and Intrauterine Growth Retardation during Further Course of Pregnancy. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2007, 57, 277–286. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Houser, B.L.; Nicotra, M.L.; Strominger, J.L. HLA-G Homodimer-Induced Cytokine Secretion through HLA-G Receptors on Human Decidual Macrophages and Natural Killer Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 5767–5772. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Song, H.; Cheng, H.; Qi, J.; Nam, G.; Tan, S.; Wang, J.; Fang, M.; Shi, Y.; Tian, Z.; et al. Structures of the Four Ig-like Domain LILRB2 and the Four-Domain LILRB1 and HLA-G1 Complex. Cell Mol Immunol 2020, 17. [CrossRef]

- Tilburgs, T.; Crespo, Â.C.; van der Zwan, A.; Rybalov, B.; Raj, T.; Stranger, B.; Gardner, L.; Moffett, A.; Strominger, J.L. Human HLA-G+ Extravillous Trophoblasts: Immune-Activating Cells That Interact with Decidual Leukocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 7219–7224. [CrossRef]

- Djurisic, S.; Teiblum, S.; Tolstrup, C.K.; Christiansen, O.B.; Hviid, T.V.F. Allelic Imbalance Modulates Surface Expression of the Tolerance-Inducing HLA-G Molecule on Primary Trophoblast Cells. Mol Hum Reprod 2014, 21, 281–295. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, R.; Lo Monte, G.; Bortolotti, D.; Graziano, A.; Gentili, V.; Di Luca, D.; Marci, R. Impact of Soluble HLA-G Levels and Endometrial NK Cells in Uterine Flushing Samples from Primary and Secondary Unexplained Infertile Women. Int J Mol Sci 2015, 16, 5510–5516. [CrossRef]

- Leonard, S.; Murrant, C.; Tayade, C.; Vandenheuvel, M.; Watering, R.; Croy, B. Mechanisms Regulating Immune Cell Contributions to Spiral Artery Modification – Facts and Hypotheses – A Review. Placenta 2006, 27, 40–46. [CrossRef]

- Carter, A.M.; Enders, A.C. Comparative Aspects of Trophoblast Development and Placentation. Reproductive biology and endocrinology 2004, 2, 46. [CrossRef]

- Carter, A.M. Evolution of Placental Function in Mammals: The Molecular Basis of Gas and Nutrient Transfer, Hormone Secretion, and Immune Responses. Physiol Rev 2012, 92, 1543–1576. [CrossRef]

- Wooding, F.B. Current Topic: The Synepitheliochorial Placenta of Ruminants: Binucleate Cell Fusions and Hormone Production. Placenta 1992, 13, 101–113.

- Pereira, F.T.V.; Oliveira, L.J.; Barreto, R.S.N.; Mess, A.; Perecin, F.; Bressan, F.F.; Mesquita, L.G.; Miglino, M.A.; Pimentel, J.R.; Neto, P.F.; et al. Fetal-Maternal Interactions in the Synepitheliochorial Placenta Using the EGFP Cloned Cattle Model. PLoS One 2013, 8, e64399. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.J.; Hansen, P.J. Deviations in Populations of Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells and Endometrial Macrophages in the Cow during Pregnancy. Reproduction 2008, 136. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, L.J.; McClellan, S.; Hansen, P.J. Differentiation of the Endometrial Macrophage during Pregnancy in the Cow. PLoS One 2010, 5. [CrossRef]

- Moffett, A.; Loke, C. Immunology of Placentation in Eutherian Mammals. Nat Rev Immunol 2006, 6, 584–594. [CrossRef]

- Chavatte-Palmer, P.; Guillomot, M.; Roïz, J.; Heyman, Y.; Laigre, P.; Servely, J.L.; Constant, F.; Hue, I.; Ellis, S. a Placental Expression of Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I in Bovine Somatic Clones. Cloning Stem Cells 2007, 9, 346–356. [CrossRef]

- Low, B.G.; Hansen, P.J.; Drost, M.; Gogolin-Ewens, K.J. Expression of Major Histocompatibility Complex Antigens on the Bovine Placenta. J Reprod Fertil 1990, 90, 235–243. [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.J.; Fisher, P.J.; Schlafer, D.H. Temporal and Regional Regulation of Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I Expression at the Bovine Uterine / Placental Interface. Placenta 2000, 21, 194–202. [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.J.; Hill, J.R.; Edwards, J.L.; Schrick, F.N.; Fisher, P.J.; Eldridge, J.A.; Schlafer, D.H. Major Histocompatibility Antigen Expression on the Bovine Placenta: Its Relationship to Abnormal Pregnancies and Retained Placenta. Anim Reprod Sci 2004, 82–83, 267–280. [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.R.; Schlafer, D.H.; Fisher, P.J.; Davies, C.J.; Al, H.E.T. Abnormal Expression of Trophoblast Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I Antigens in Cloned Bovine Pregnancies Is Associated with a Pronounced Endometrial Lymphocytic Response 1. Biol Reprod 2002, 67, 55–63. [CrossRef]

- Fair, T.; Gutierrez-Adan, A.; Murphy, M.; Rizos, D.; Martin, F.; Boland, M.P.; Lonergan, P. Search for the Bovine Homolog of the Murine Ped Gene and Characterization of Its Messenger RNA Expression during Bovine Preimplantation Development. Biol Reprod 2004, 70, 488–494. [CrossRef]

- Rutigliano, H.M.; Thomas, A.J.; Wilhelm, A.; Sessions, B.R.; Hicks, B.A.; Schlafer, D.H.; White, K.L.; Davies, C.J. Trophoblast Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I Expression Is Associated with Immune-Mediated Rejection of Bovine Fetuses Produced by Cloning. Biol Reprod 2016, 95, 39–39. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Cowley, A.; Uludag, M.; Gur, T.; McWilliam, H.; Squizzato, S.; Park, Y.M.; Buso, N.; Lopez, R. The EMBL-EBI Bioinformatics Web and Programmatic Tools Framework. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43. [CrossRef]

- Sangalli, J.R.; De Bem, T.H.C.; Perecin, F.; Chiaratti, M.R.; Oliveira, L. de J.; de Araújo, R.R.; Valim Pimentel, J.R.; Smith, L.C.; Meirelles, F.V. Treatment of Nuclear-Donor Cells or Cloned Zygotes with Chromatin-Modifying Agents Increases Histone Acetylation but Does Not Improve Full-Term Development of Cloned Cattle. Cell Reprogram 2012, 14, 235–247. [CrossRef]

- Evans, H.E.; Sack, W.O. Prenatal Development of Domestic and Laboratory Mammals: Growth Curves, External Features and Selected References. Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia: Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series C 1973, 2, 11–45. [CrossRef]

- Miglino, M. a; Pereira, F.T. V; Visintin, J. a; Garcia, J.M.; Meirelles, F. V; Rumpf, R.; Ambrósio, C.E.; Papa, P.C.; Santos, T.C.; Carvalho, a F.; et al. Placentation in Cloned Cattle: Structure and Microvascular Architecture. Theriogenology 2007, 68, 604–617. [CrossRef]

- Mess, A.M.; Oliveira Carreira, A.C.; Oliveira, C.M. de; Fratini, P.; Favaron, P.O.; Barreto, R. da S.N.; Pfarrer, C.; Meirelles, F.V.; Miglino, M.A. Vascularization and VEGF Expression Altered in Bovine Yolk Sacs from IVF and NT Technologies. Theriogenology 2017, 87, 290–297. [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.R.; Burghardt, R.C.; Jones, K.; Long, C.R.; Looney, C.R.; Shin, T.; Spencer, T.E.; Thompson, J.A.; Winger, Q.A.; Westhusin, M.E. Evidence for Placental Abnormality as the Major Cause of Mortality in First-Trimester Somatic Cell Cloned Bovine Fetuses. Biol Reprod 2000, 63, 1787–1794. [CrossRef]

- O’Gorman, G.M.; Al Naib, A.; Naib, A. Al; Ellis, S. a; Mamo, S.; O’Doherty, A.M.; Lonergan, P.; Fair, T. Regulation of a Bovine Nonclassical Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I Gene Promoter. Biol Reprod 2010, 83, 296–306. [CrossRef]

- Al Naib, a; Mamo, S.; O’Gorman, G.M.; Lonergan, P.; Swales, A.; Fair, T. Regulation of Non-Classical Major Histocompatability Complex Class I MRNA Expression in Bovine Embryos. J Reprod Immunol 2011, 91, 31–40. [CrossRef]

- Mansouri-Attia, N.; Oliveira, L.J.; Forde, N.; Fahey, A.G.; Browne, J.A.; Roche, J.F.; Sandra, O.; Reinaud, P.; Lonergan, P.; Fair, T. Pivotal Role for Monocytes/Macrophages and Dendritic Cells in Maternal Immune Response to the Developing Embryo in Cattle. Biol Reprod 2012, 87, 123. [CrossRef]

- Goossens, K.; Van Poucke, M.; Van Soom, A.; Vandesompele, J.; Van Zeveren, A.; Peelman, L.J. Selection of Reference Genes for Quantitative Real-Time PCR in Bovine Preimplantation Embryos. BMC Dev Biol 2005, 5, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Mansouri-Attia, N.; Sandra, O.; Aubert, J.; Degrelle, S.; Everts, R.E.; Giraud-Delville, C.; Heyman, Y.; Galio, L.; Hue, I.; Yang, X.; et al. Endometrium as an Early Sensor of in Vitro Embryo Manipulation Technologies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 5687–5692. [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [CrossRef]

- O’Gorman, G.M.; Al Naib, A.; Naib, A. Al; Ellis, S. a; Mamo, S.; O’Doherty, A.M.; Lonergan, P.; Fair, T. Regulation of a Bovine Nonclassical Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I Gene Promoter. Biol Reprod 2010, 83, 296–306. [CrossRef]

- Al Naib, a; Mamo, S.; O’Gorman, G.M.; Lonergan, P.; Swales, A.; Fair, T. Regulation of Non-Classical Major Histocompatability Complex Class I MRNA Expression in Bovine Embryos. J Reprod Immunol 2011, 91, 31–40. [CrossRef]

- Mansouri-Attia, N.; Sandra, O.; Aubert, J.; Degrelle, S.; Everts, R.E.; Giraud-Delville, C.; Heyman, Y.; Galio, L.; Hue, I.; Yang, X.; et al. Endometrium as an Early Sensor of in Vitro Embryo Manipulation Technologies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 5687–5692. [CrossRef]

- Goossens, K.; Van Poucke, M.; Van Soom, A.; Vandesompele, J.; Van Zeveren, A.; Peelman, L.J. Selection of Reference Genes for Quantitative Real-Time PCR in Bovine Preimplantation Embryos. BMC Dev Biol 2005, 5, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Mansouri-Attia, N.; Oliveira, L.J.; Forde, N.; Fahey, A.G.; Browne, J.A.; Roche, J.F.; Sandra, O.; Reinaud, P.; Lonergan, P.; Fair, T. Pivotal Role for Monocytes/Macrophages and Dendritic Cells in Maternal Immune Response to the Developing Embryo in Cattle. Biol Reprod 2012, 87, 123. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, R.M.; Miller, K.; Soares, F.; Vassallo, J.; Shenka, N.; Gobbi, H. The Use of the Immunohistochemical Biotin-Free Visualization Systems for Estrogen Receptor Evaluation of Breast Cancer. Applied Cancer Research 2009, 29, 112–117.

- Ellis, S.A.; Sargent, I.L.; Charleston, B.; Bainbridge, D.R.J. Regulation of MHC Class I Gene Expression Is at Transcriptional and Post-Transcriptional Level in Bovine Placenta. J Reprod Immunol 1998, 37, 103–115. [CrossRef]

- Bainbridge, D.R.J.; Sargent, I.L.; Ellis, S.A. Increased Expression of Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) Class I Transplantation Antigens in Bovine Trophoblast Cells before Fusion with Maternal Cells. Reproduction 2001, 122, 907–913. [CrossRef]

- Ishitani, A.; Sageshima, N.; Lee, N.; Dorofeeva, N.; Hatake, K.; Marquardt, H.; Geraghty, D.E. Protein Expression and Peptide Binding Suggest Unique and Interacting Functional Roles for HLA-E, F, and G in Maternal-Placental Immune Recognition. Journal of Immunology 2003, 171, 1376–1384. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L. de M.; Ambrósio, C.E.; Teixeira, D.G.; Araújo, K.P.C.; Júnior, J.R.K.; Junior, J.C.M.; Morini, A.C.; Rici, R.E.G.; Ferreira, G.J.B. de C.; Martins, D. dos S.; et al. Behavior of Binucleate Giant Cells in Nelore Cow Placenta (Bos Indicus - Linnaeus, 1758) [Comportamento Das Células Trofoblásticas Gigantes Na Placenta de Vacas Nelore (Bos Indicus -Linnaeus, 1758)]. Rev Bras Reprod Anim 2008, 32, 110–121.

- Birch, J.; Codner, G.; Guzman, E.; Ellis, S. a Genomic Location and Characterisation of Nonclassical MHC Class I Genes in Cattle. Immunogenetics 2008, 60, 267–273. [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.J. Why Is the Fetal Allograft Not Rejected? J Anim Sci 2007, 85, E32-5. [CrossRef]

- Hiendleder, S.; Zakhartchenko, V.; Wenigerkind, H.; Reichenbach, H.-D.; Brüggerhoff, K.; Prelle, K.; Brem, G.; Stojkovic, M.; Wolf, E. Heteroplasmy in Bovine Fetuses Produced by Intra- and Inter-Subspecific Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer: Neutral Segregation of Nuclear Donor Mitochondrial DNA in Various Tissues and Evidence for Recipient Cow Mitochondria in Fetal Blood. Biol Reprod 2003, 68, 159–166. [CrossRef]

- Turin, L.; Invernizzi, P.; Woodcock, M.; Grati, F.R.; Riva, F.; Tribbioli, G.; Laible, G. Bovine Fetal Microchimerism in Normal and Embryo Transfer Pregnancies and Its Implications for Biotechnology Applications in Cattle. Biotechnol J 2007, 2, 486–491. [CrossRef]

- Lemos, D.C.; Takeuchi, P.L.; Rios, A.F.L.; Araújo, A.; Lemos, H.C.; Ramos, E.S. Bovine Fetal DNA in the Maternal Circulation: Applications and Implications. Placenta 2011, 32, 912–913. [CrossRef]

- Rutigliano, H.M.; Thomas, A.J.; Umbaugh, J.J.; Wilhelm, A.; Sessions, B.R.; Kaundal, R.; Duhan, N.; Hicks, B.A.; Schlafer, D.H.; White, K.L.; et al. Increased Expression of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines at the Fetal–Maternal Interface in Bovine Pregnancies Produced by Cloning. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2022, 87. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Jiang, K.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, G.; Shaukat, A.; Deng, G. The Expression of Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I in Endometrial Epithelial Cells from Dairy Cow under a Simulating Hypoxic Environment. Res Vet Sci 2018, 118, 61–65. [CrossRef]

- Meirelles, F. V; Birgel, E.H.; Perecin, F.; Bertolini, M.; Traldi, A.S.; Pimentel, J.R. V; Komninou, E.R.; Sangalli, J.R.; Neto, P.F.; Nunes, M.T.; et al. Delivery of Cloned Offspring: Experience in Zebu Cattle (Bos Indicus). Reprod Fertil Dev 2010, 22, 88–97. [CrossRef]

- Hoffert-Goeres, K.A.; Batchelder, C.A.; Bertolini, M.; Moyer, A.L.; Famula, T.R.; Anderson, G.B. Angiogenesis in Day-30 Bovine Pregnancies Derived from Nuclear Transfer. Cloning Stem Cells 2007, 9, 595–607. [CrossRef]

- Bouteiller, P. Le; Blaschitz, A. The Functionality of HLA-G Is Emerging. Immunol Rev 1999, 167, 233–244. [CrossRef]

- Rutigliano, H.M.; Thomas, A.J.; Wilhelm, A.; Sessions, B.R.; Hicks, B.A.; Schlafer, D.H.; White, K.L.; Davies, C.J. Trophoblast Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I Expression Is Associated with Immune-Mediated Rejection of Bovine Fetuses Produced by Cloning. Biol Reprod 2016, 95, 39–39. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, J.; Manning, L.; Mitchell, D.; Selanders, J.; Wood, G. Localization and Characterization of Macrophages in Murine Uterus. J Leukoc Biol 1985, 38, 255–265. [CrossRef]

- Billington, W.D. Species Diversity in the Immunogenetic Relationship between Mother and Fetus: Is Trophoblast Insusceptibility to Immunological Destruction the Only Essential Common Feature for the Maintenance of Allogeneic Pregnancy? Exp Clin Immunogenet 1993, 10, 73–84.

- Shi, B.; Thomas, A.J.; Benninghoff, A.D.; Sessions, B.R.; Meng, Q.; Parasar, P.; Rutigliano, H.M.; White, K.L.; Davies, C.J. Genetic and Epigenetic Regulation of Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I Gene Expression in Bovine Trophoblast Cells. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology 2018, 79. [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, L.S.; da Silva Mol, J.P.; de Macedo, A.A.; Silva, A.P.C.; dos Santos Ribeiro, D.L.; Santos, R.L.; da Paixão, T.A.; de Carvalho Neta, A.V. Transcription of Non-Classic Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) Class I in the Bovine Placenta throughout Gestation and after Brucella Abortus Infection. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 2015, 167, 166–170. [CrossRef]

| Gene Symbol | Gene Name | Gene ID | Sequence (5’ – 3’) | Amplicon | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOLA-NC1 | MHC 1 non-classical 1 | F: GGATACAAAAGGAAAACACACAGACTT | 77 | [40] | |

| R: GGCCTCGCTCTGGTTGTAGT | |||||

| BOLA-NC2 | MHC 1 non-classical 2 | F: TGCGCGGCTACTACAACCA | 67 | Mansouri-Attia in press | |

| R: ACGTCGCAGCCGTACATCTC | |||||

| BOLA-NC3 | MHC 1 non-classical 3 | F: CCTGCGCGGCTACTACAAC | 70 | Mansouri-Attia in press | |

| R: CACTTCGCAGCCAAACATCA | |||||

| BOLA-NC4 | MHC 1 non-classical 4 | F: TTGCGAACGGGCTTGAAC | 74 | [41] | |

| R: ACCCACTGGAGGGTGTGAGA | |||||

| JSP-1 | MHC-class I JSP-1 | 407173 | F: TAGGAGTTAGGGAGACTGGCCC | 121 | [42] |

| R: AGCCTCGTCTCTGCTGGAAC | |||||

| YWHAZ | tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein, zeta | 287022 | F: GCATCCCACAGACTATTTCC | 150 | [43] |

| R: GCAAAGACAATGACAGACCA | |||||

| ACTB | Beta-actin | 280979 | F: CAGCAGATGTGGATCAGCAAGC | 108 | [44] |

| R: AACGCAGCTAACAGTCCGCC | |||||

| PPIA | Peptidylprolyl isomerase A | 281418 | F: CATACAGGTCCTGGCATC | 91 | [44] |

| R: CACGTGCTTGCCATCCAA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).