1. Introduction

Fruit processing industries generate substantial waste, primarily consisting of seeds and peels. In juice production facilities, approximately 50% of fruit becomes waste material, with peels accounting for 50–55% of this waste. This creates serious environmental challenges as microbial decomposition leads to the mission of greenhouse gases [

1]. Consequently, it is now imperative that fruit waste be managed sustainably [

2]. Food processing produces byproducts of bioactive compounds, including pectin. These pectins from the food processing industries are considered non-toxic heteropolysaccharides [

3] that have also been actively used in the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries [

4]. Pectin has a variety of uses in the food, pharmaceutical, and healthcare industries, as well as in packaging regulations. In food processing, it acts as a thickener, emulsifier, and stabilizing agent. The pharmaceutical industry employs pectin to develop medications for lowering blood cholesterol, treating gastrointestinal disorders, and cancer therapy [

5]. To support its continued use in the food industry, pectin must be recovered and extracted from food waste materials [

6,

7]. In plants, pectin naturally occurs in cell walls, intercellular spaces, and the central lamella, connected through glycosidic linkages [

8]. This compound is essential for mechanical strength and intercellular connections, providing plant tissue with its firmness and structure. Additionally, it contributes to plant cells' turgidity and resilience [

9]. The term "pectin" encompasses various polymers that differ in molecular mass, chemical composition, and sugar concentration, as different plants produce pectin with distinct functional properties. Common sources of pectin include citrus peel, apple pomace, cocoa husk, and potato pulp [

10]. Certain fruits such as apples, citrus fruits, blackberries, cranberries, gooseberries, grapes, and plums contain high levels of pectic components in their polysaccharides. Notably, mature banana peels contain higher pectin concentrations compared to other fruits [

11]. Furthermore, the abundance of pectin in various fruits and vegetables demonstrates its role in maintaining cell wall strength, flexibility, and biological processes. Pectin content varies significantly by source: citrus peels contain 20-30% pectin, sugar beet yields 10-20%, while apple pomace contains less than 15% on a dry weight basis [

12].

Louis Nicolas Vauquelin isolated the molecule pectin from the fruit known as tamarind for the first time in 1790. Henri Braconnot first used pectin in 1825, derived from the Greek word "pektikos," which means solidifying or coagulating [

13]. Modern nutritionists have shown particular interest in pectins as they serve as dietary fiber that increases transit time and glucose absorption in the digestive tract, leading to notable physiological effects [

14]. The structure of pectin determines its physicochemical characteristics, making it essential to investigate the extracted pectin's structure. The source of the pectin, plant growth phases, and their extraction conditions significantly impact pectin structures [

15]. The backbone of pectin is made up of galacturonic acids (GalpA) joined by (1,2)-linked β- L- rhamnose (Rhap). Galacturonic acid and its units are linked with additional substances found in the cell walls of plants, such as lignin, cellulose, or polyphenols [

16]. Homogalacturonan (HG) and rhamnogalacturonan I (RG-I) are the most prevalent classes of these extremely complex polysaccharides that are covalently bonded. Rhamnogalacturonan II (RG-II), xylogalacturonan (XGA), and apiogalacturonan (AGA) are examples of small constituents of substituted galacturonans [

17]. Given the intricate structure of the polysaccharides in pectin and the fact that plants retain the many genes needed to synthesise pectin, it is likely that pectin serves a variety of purposes in the growth and development of plants. During ripening, the pectin structure is hydrolyzed by enzymes such as pectinase and pectinesterase. The main job of the enzyme pectinase is to break down the pectin's whole structure by cleaving the primary pectin chain and its side branches, changing it into a common soluble polymer [

18]. The chemical structure of pectin is very interesting as it consists of linear polysaccharides with a higher molecular weight varying between 75,000-125,000 g/mol [

19]. The carboxyl groups can be found free or as salts with calcium, sodium, or other tiny counterion of residual uronic acid. They can also be found naturally esterified in certain situations, typically with methanol. The presence of free carboxyl groups contributes to pectin's acidic nature The chemical structure of pectin is affected by its physicochemical properties, such as molar masses, extent of methylation, and esterification, which in turn is vital for functional characteristics like gelling, solubility, and viscosity [

20]. The structure of pectin can be modified by non-sugar components like methanol, acetic acid, phenolic acids, and sometimes amide groups. In addition, these non-sugar components consist of polyesters, polyhydric alcohols, poly acids, reduced carbohydrates, certain polar carboxyl groups, and non-polar methyl groups [

21].

The process of separating pectin from the source plant matter is the first step in using it. Historically, using acid for commercially extracting pectin has become the norm [

22]. However, pectin extraction techniques remain an important challenge requiring further research. Optimizing the extraction process and improving the quality of the pectin need the use of an efficient extraction technique. Green extraction techniques have emerged as an alternative approach in recent years due to the growing awareness of environmental protection. Later on, several eco-friendly extraction techniques, such as enzyme-assisted extraction (EAE), microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), and ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), have been developed to improve pectin quality and efficiency [

23,

24,

25]. This review will discuss many other green techniques for pectin extraction.

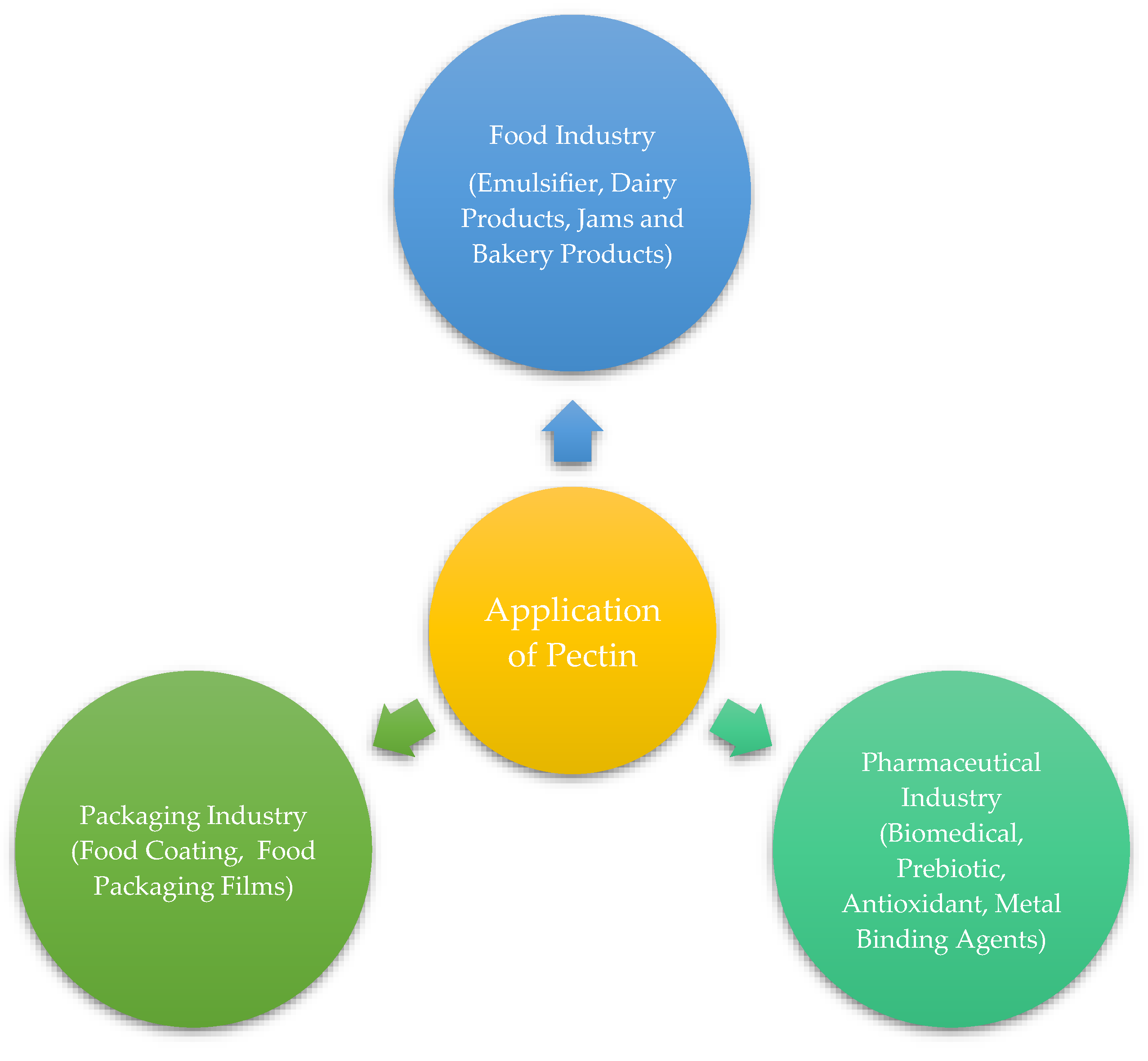

Pectin has many potential applications, from the industrial and pharmaceutical sectors to the primary food processing industries. Various applications of pectin have been demonstrated in

Figure 1. The compound has gained significant importance in nutrition, food, and health sectors. Its molecular structure, comprising polar and nonpolar components, enables seamless integration into various food items [

26]. Contemporary data suggests that people are more focused on healthy diets and are actively looking for feasible substitutes for petroleum-based plastic used in food packaging [

27]. The edible polymers make excellent alternatives to these plastics, given their non-toxicity, environmental friendliness, and compatibility with most foods. Because of its capacity to gel and transport active substances like antimicrobials and antioxidants, pectin has justly found application in edible packaging [

28,

29]. Pectin is a valuable thickener [

30], stabilizer [

31,

32,

33], and emulsifier [

34] in the food industry because of its multipurpose qualities. Pectin is frequently employed in jams, marmalades, and jellies because it can create a viscoelastic solution and a structural network. Pectin’s origin and the way it is processed directs particular qualities, resulting in its varied uses. For instance, in comparison to pectin from other plant fruits, apple pectin is characteristically more viscous and provides dark shades. As a result, it works better with fillings and pastries. However, compared to apple pectin, citrus pectin is lighter and better fit as a texturing ingredient for jam and sweet jellies. So, it can be inferred that the structure of pectin can influence its use [

35]. Additionally, pectin has also been shown to have biomedical and biomaterial applications. Although humans cannot digest or absorb pectin, it helps with good bacteria in the large intestine to provide prebiotic qualities [

36]. Several researchers [

37,

38] have documented the health benefits of pectin use, which include preventing inflammatory and allergic illnesses, supporting cancer treatment, and reducing blood sugar and cholesterol levels. While numerous literature reviews cover pectin's extraction, structural chemistry, pharmaceutical applications, and its nutritional and functional properties in food packaging [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43], comprehensive research on greener extraction techniques and their applications remains limited. This review examines green extraction methodologies of pectin, their physiochemical properties, structural characterization, and future multidisciplinary applications.

Figure 1.

Various applications of pectin.

Figure 1.

Various applications of pectin.

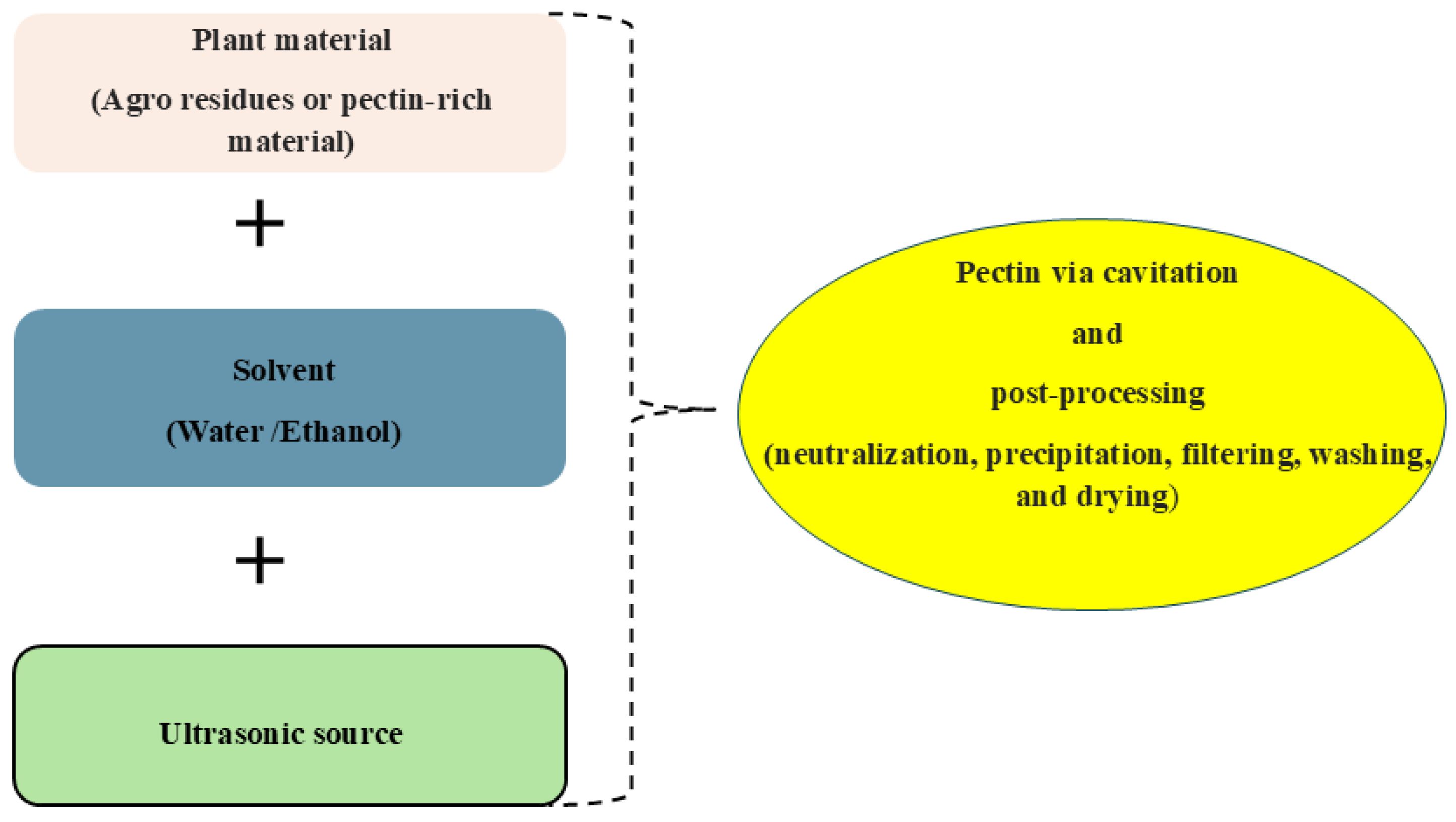

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction technique.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction technique.

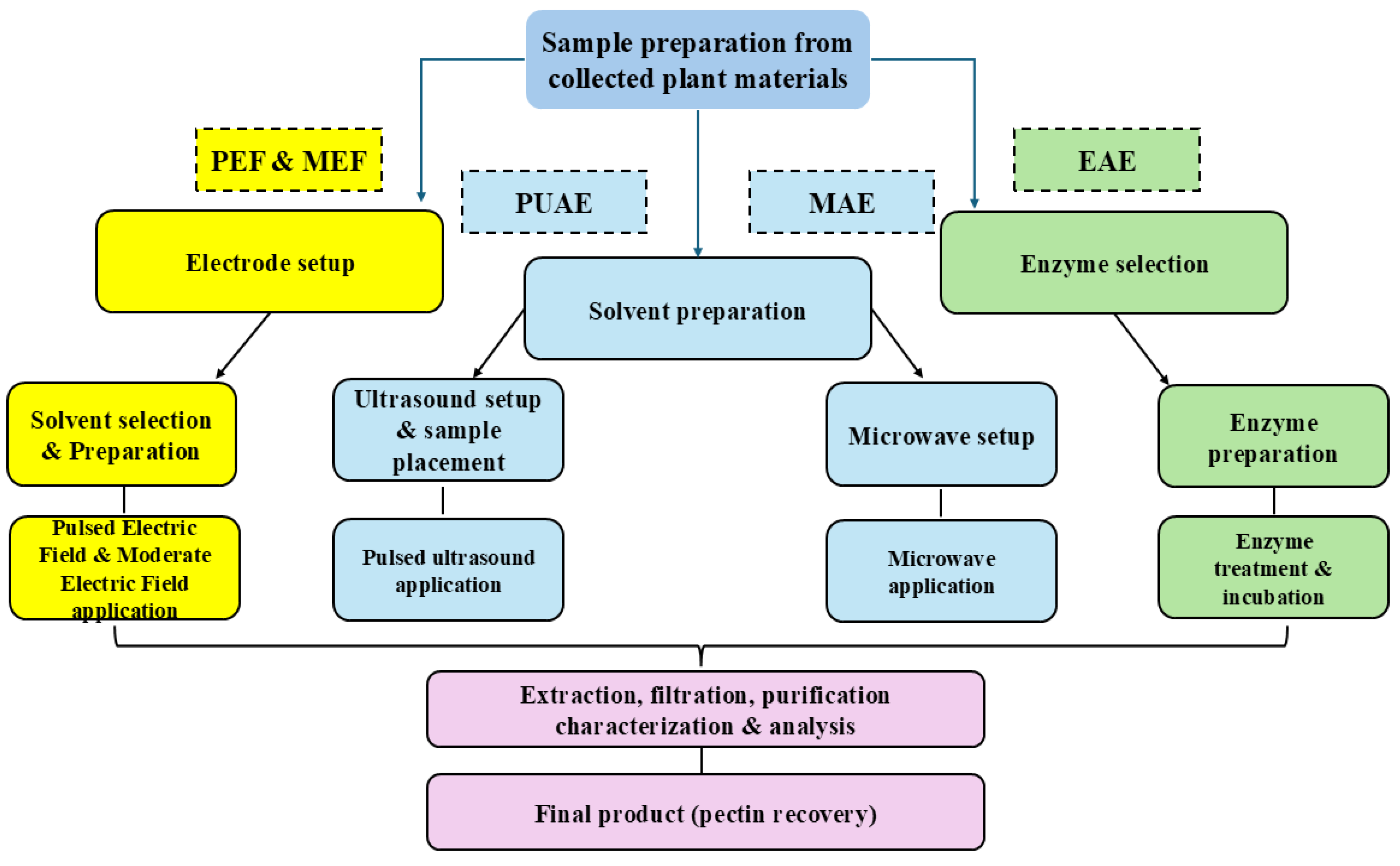

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of PUAE, PEF, MAE and EAE extraction techniques.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of PUAE, PEF, MAE and EAE extraction techniques.

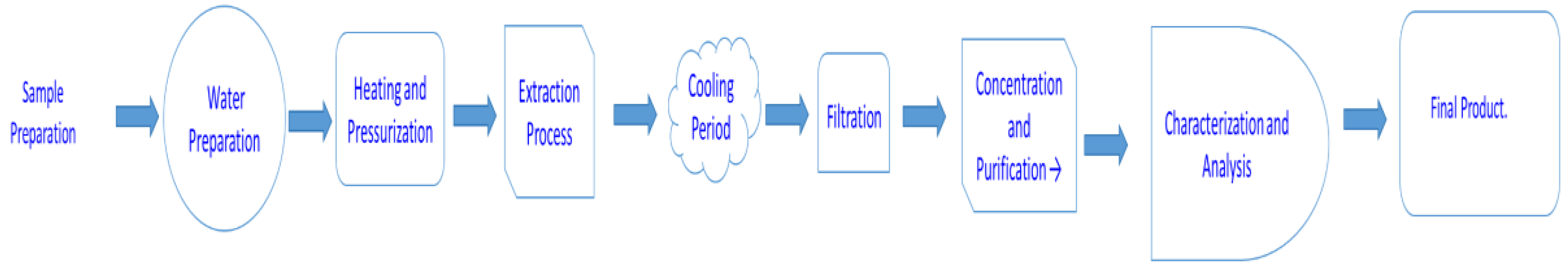

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the SWE technique.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the SWE technique.

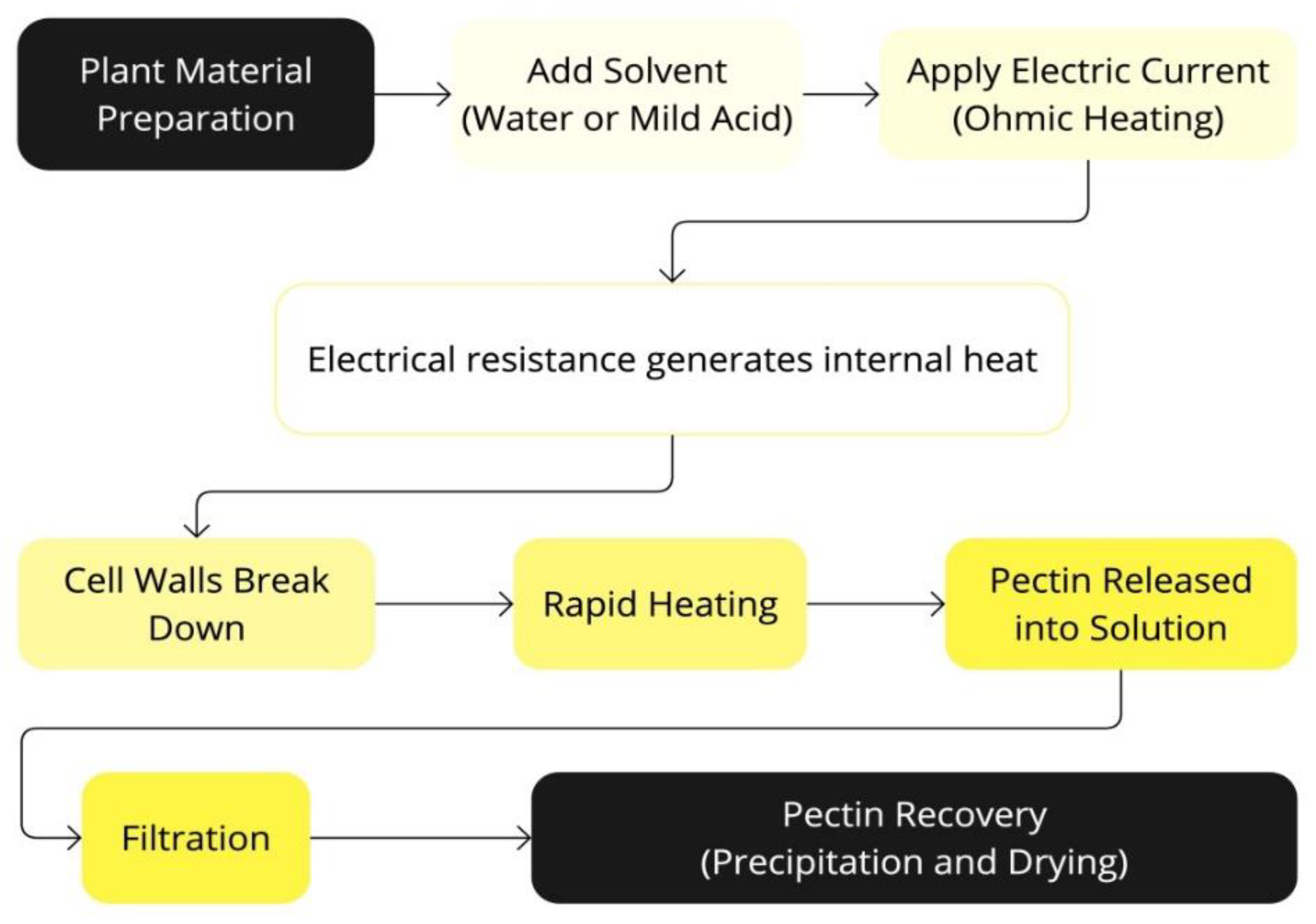

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the Ohmic Heating-Assisted Extraction (OHAE) process.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the Ohmic Heating-Assisted Extraction (OHAE) process.

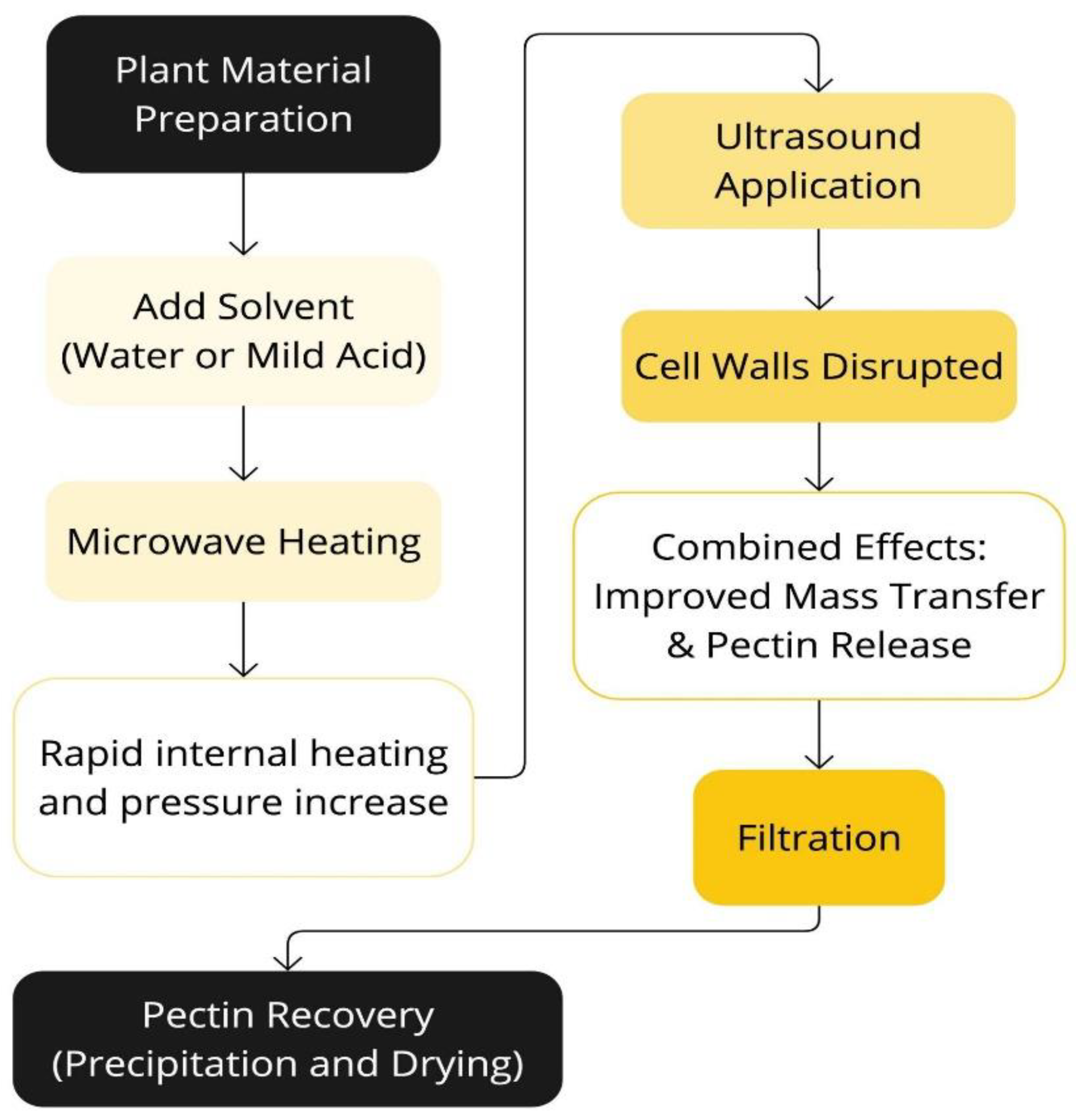

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the Ultrasound-Assisted Microwave Extraction (UAME) process.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the Ultrasound-Assisted Microwave Extraction (UAME) process.

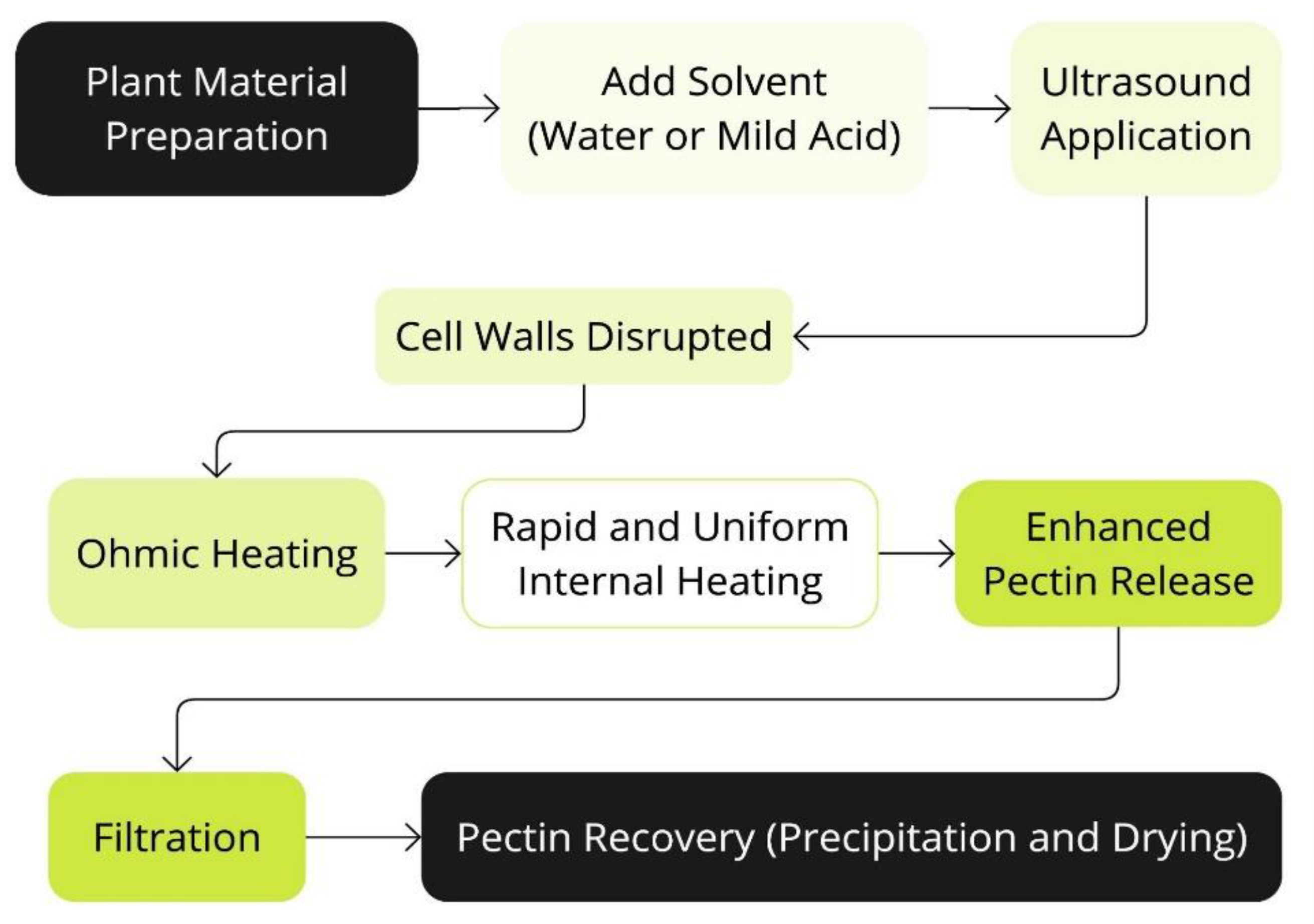

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the process of Ultrasound-Assisted Ohmic Heating Extraction (UAOHE).

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the process of Ultrasound-Assisted Ohmic Heating Extraction (UAOHE).

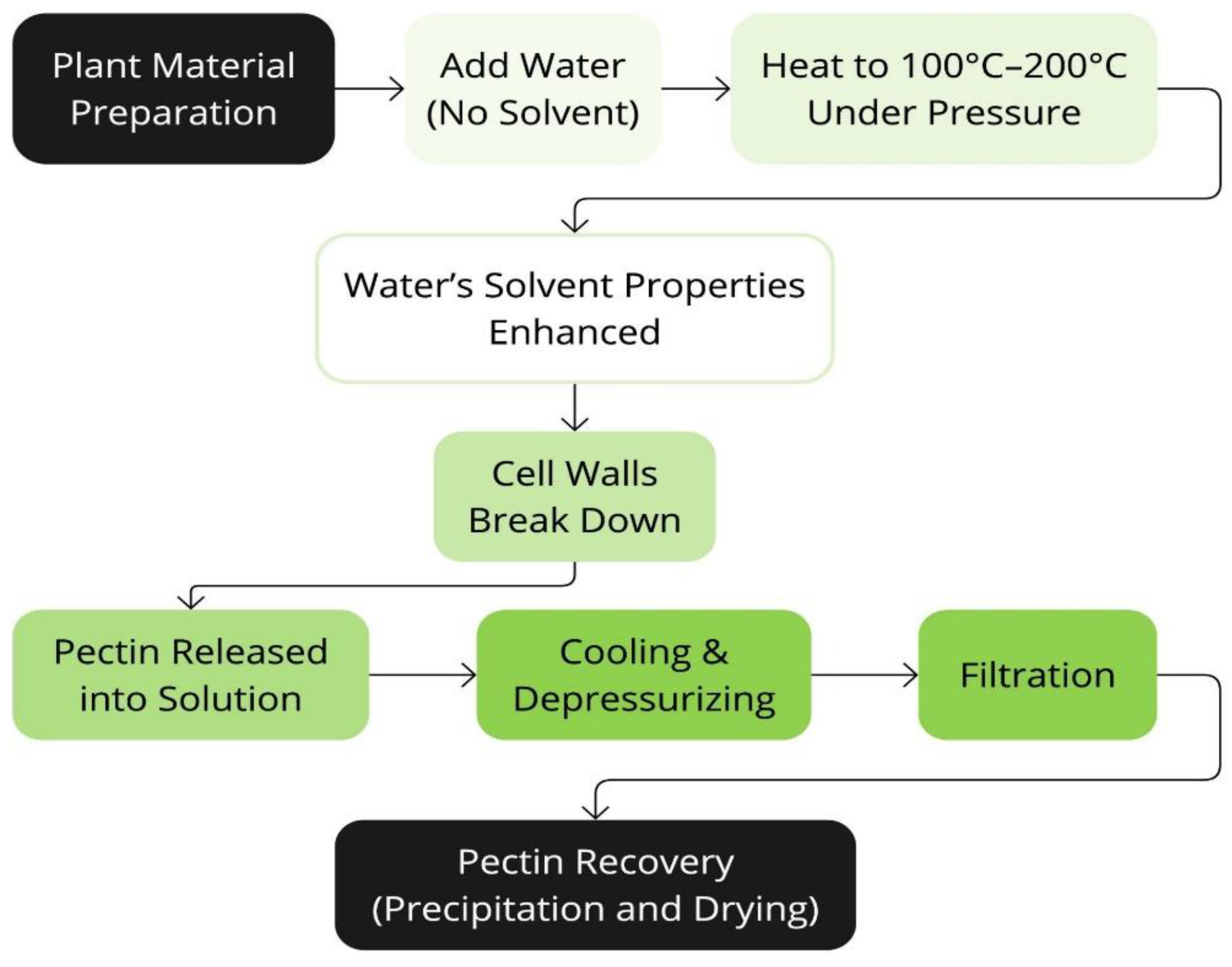

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of the Hydrothermal Extraction process (HTE).

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of the Hydrothermal Extraction process (HTE).

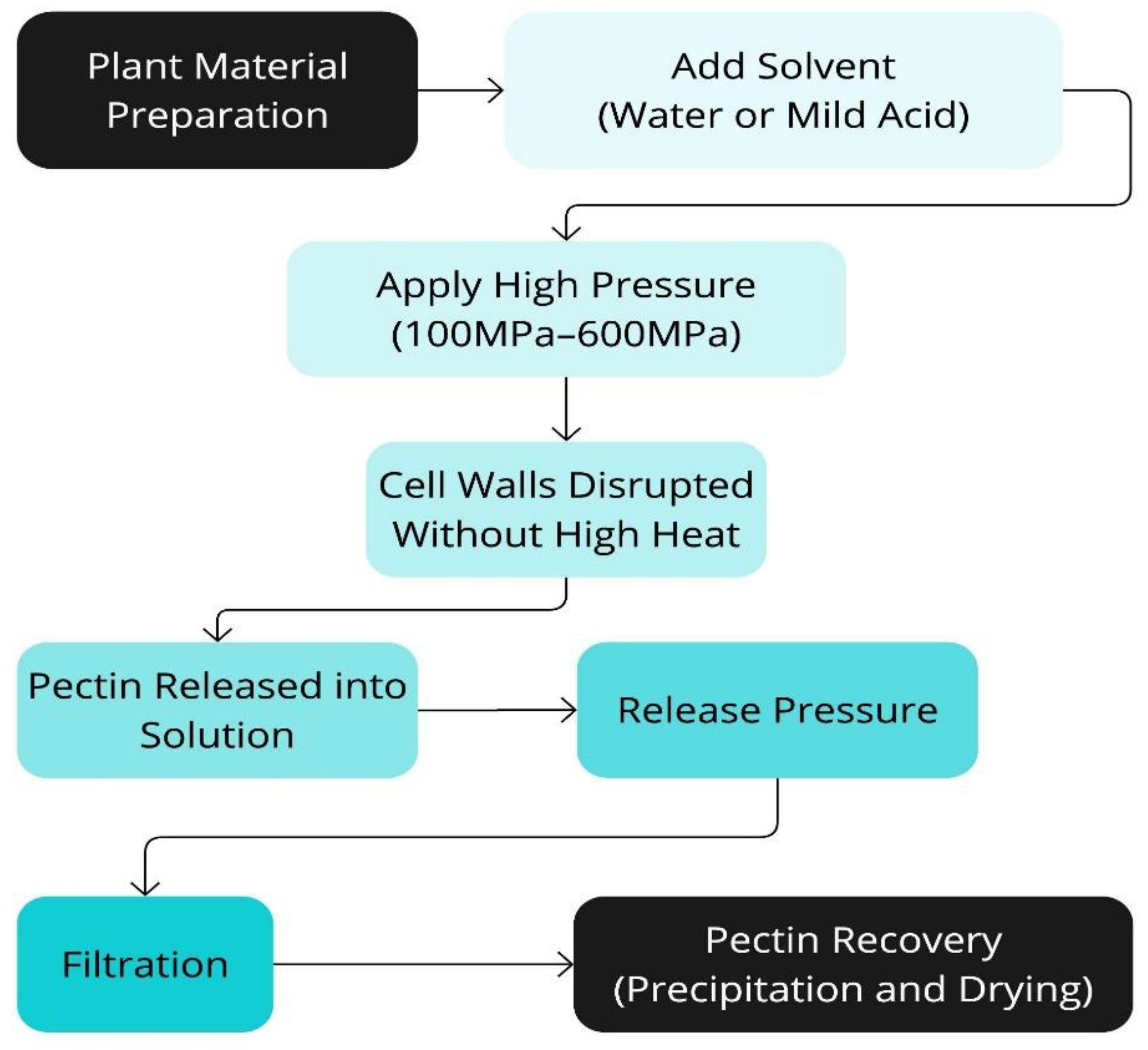

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of the High-Pressure Processing Extraction technique (HPPE).

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of the High-Pressure Processing Extraction technique (HPPE).

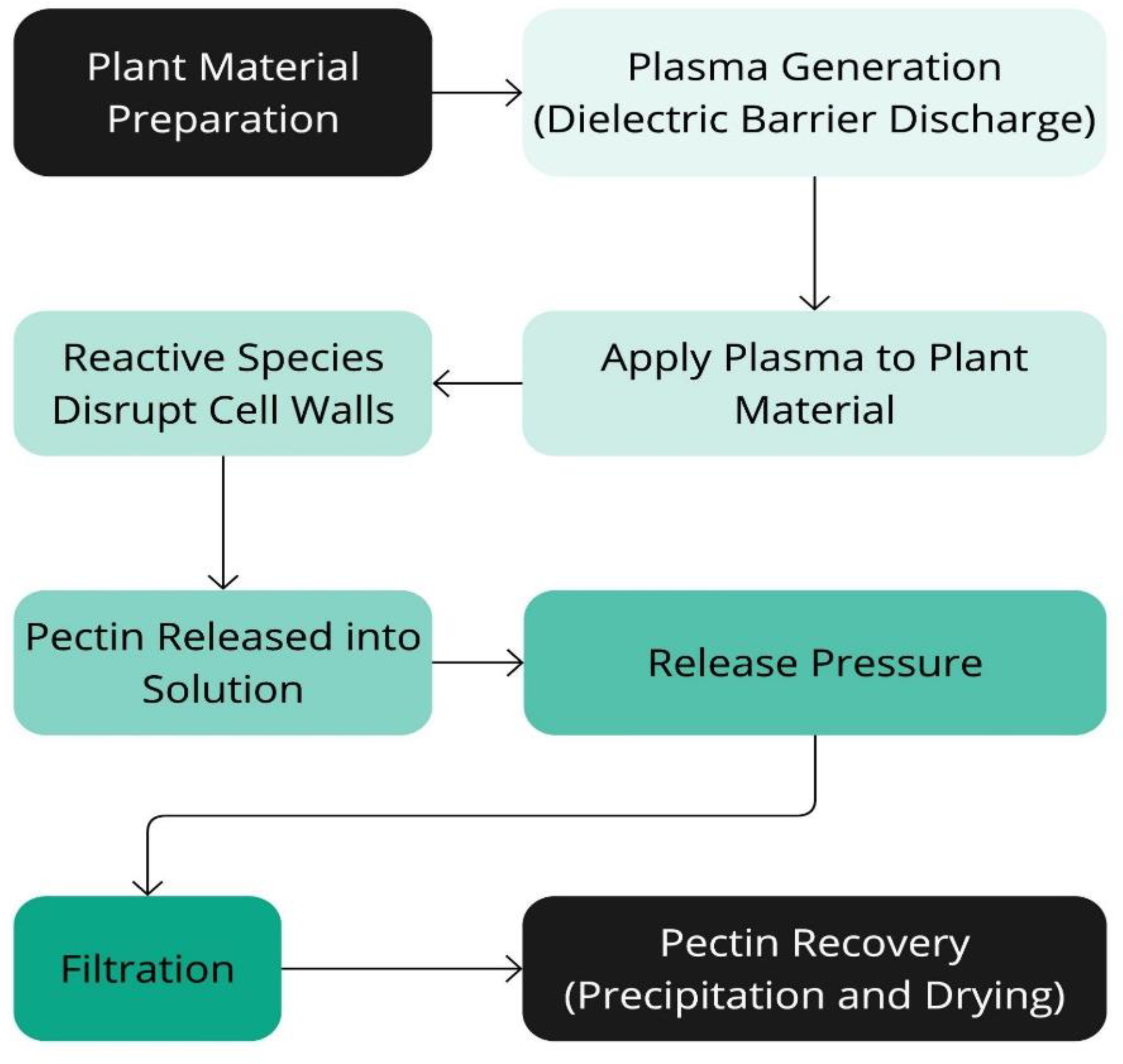

Figure 10.

Schematic representation of the Dielectric Barrier Discharge Extraction (DBDE) process.

Figure 10.

Schematic representation of the Dielectric Barrier Discharge Extraction (DBDE) process.

Table 1.

Details of methoxyl content (MeO) and Degree of esterification (DE) for pectin extracted from various sources using different methods.

Table 1.

Details of methoxyl content (MeO) and Degree of esterification (DE) for pectin extracted from various sources using different methods.

| Pectin Source |

Extraction method |

MeO (%) |

DE (%) |

Ref. |

| Pomelo peel |

Hot acid extraction |

7.43 |

55.67 |

[67] |

| Microwave-assisted extraction |

8.35 |

55.34 |

| Ultrasound-assisted extraction |

7.08 |

51.42 |

| Enzyme-assisted extraction |

6.62 |

47.71 |

| Apple pomace |

Hot acid extraction |

8.13 |

63.80 |

[69] |

| Extraction using citric acid |

9.69 |

63.42 |

| Organic acid mixture extraction |

10.85 |

64.55 |

| Microwave-assisted extraction |

9.30 |

64.80 |

| Ultrasound-assisted extraction |

8.79 |

64.18 |

| Citrus sinensis-Poncirus trifoliata |

Hot acid extraction |

10.20 |

62.50 |

[70] |

| Electromagnetic induction extraction |

09.9 |

61.00 |

| Orange Peel Waste |

Extraction using HCl |

- |

59.37 |

[71] |

| Sea buckthorn peel |

Extraction using citric acid |

- |

57.75 |

[72] |

| Fălticeni’ apple Pomace |

Extraction using citric acid |

3.04 |

84.4 |

[73] |

| Microwave-assisted extraction |

4.77 |

73.8 |

| Ultrasound extraction with and without heat treatment |

4.22 |

77 |

| Enzyme-assisted extraction-ultrasound treatment |

3.9 |

47.6 |

| Sweet lime |

Hydrothermal extraction |

8.8 |

71.2 |

[74] |

| Conventional solvent extraction |

6.8 |

61.1 |

| Lemon peels |

Extraction using HCl |

9.3 |

82.7 |

[75] |

| Feijoa (Acca sellowiana) fruit |

Microwave-enzyme-assisted extraction |

- |

68.43 |

[76] |

| Enzyme-assisted extraction |

- |

67.89 |

| Indonesian mangosteen |

Acid extraction using H2SO4

|

2.86 |

75.98 |

[77] |

| Citrus Reticulata peels |

Microwave-assisted extraction |

09.30 |

78.95 |

[78] |

| Citrus fruit wastes |

Microwave-assisted extraction |

4.91 |

31.36 |

[79] |

| Banana peel |

Extraction using HCl |

- |

27.63 |

[80] |

| Extraction using citric acid |

- |

50.27 |

| Maleic acid extraction |

- |

44.88 |

| Pumpkin peels |

Extraction using HNO3

|

6.20 |

66.53 |

[81] |

| Extraction using citric acid |

7.23 |

66.57 |

| Eggplant Peels |

Extraction using citric acid |

5.76 |

61.33 |

[82] |

| Orange peel |

Hot water extraction |

13.81 |

96.58 |

[83] |

| Breadfruit’s peel |

Acidic extraction using HCl |

15.78 |

96.70 |

[84] |

| Papaya’s peel |

5.5 |

33.67 |

Table 2.

Details Degree of esterification (DE) and Degree of acylation (DA) for pectin extracted from various sources using different methods.

Table 2.

Details Degree of esterification (DE) and Degree of acylation (DA) for pectin extracted from various sources using different methods.

| Pectin Source |

Extraction method |

DE (%) |

DA (%) |

Ref. |

| Jack fruit |

Extraction using citric acid |

75.82 |

0.478 |

[88] |

| Jack fruit |

Extraction using HNO3

|

74.82 |

0.418 |

[88] |

| Potato pulp |

Extraction using HCl |

|

11.92 |

[86] |

| Mosambi peels |

Extraction using HCl |

51.81 |

0.51 |

[87] |

| Sugar Beet Flakes |

Extraction using citric acid |

|

21.90 |

[85] |

| Kinnow peels |

Extraction using HCl |

51.86 |

0.47 |

[87] |

| Sugar Beet Flakes |

Microwave-assisted extraction |

|

21.90 |

[85] |

| Potato pulp |

Extraction using H2SO4

|

|

10.51 |

[86] |

| Orange peels |

Extraction using HCl |

53.55 |

0.48 |

[87] |

| Jack fruit |

Extraction using H2SO4

|

72.82 |

0.567 |

[88] |

| Sugar Beet Flakes |

Pulsed ultrasound-assisted extraction |

|

22.58 |

[85] |

| Chempedak |

Extraction using citric acid |

69.01 |

0.060 |

[88] |

| Potato pulp |

Extraction using HNO3

|

|

10.51 |

[86] |

| Chempedak |

Extraction using HNO3

|

69.1 |

0.328 |

[88] |

| Potato pulp |

Extraction using citric acid |

|

9.21 |

[86] |

| Potato pulp |

Extraction using acetic acid |

|

15.38 |

[86] |

| Chempedak |

Extraction using H2SO4

|

66.34 |

0.328 |

[88] |

| Coffee Arabica pulp |

Extraction using H2SO4

|

78.5 |

1.10 |

[89] |

Table 3.

Polydispersity index for pectin extracted from various sources using different methods.

Table 3.

Polydispersity index for pectin extracted from various sources using different methods.

| Source |

Extraction method |

PDI |

Ref. |

| Sweet lime |

Hydrothermal extraction |

2.71 |

[74] |

| Conventional solvent extraction |

3.42 |

| Fresh dragon fruit |

Cold-Water Extraction |

4.81 |

[95] |

| Hot-Water Extraction |

4.19 |

| Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction |

4.22 |

| Enzyme-Assisted Extraction |

13.04 |

| Pulp in Pods of Riang |

Extraction using citric acid |

4.31 |

[96] |

| Apple |

Hydrolysis-extraction |

8 |

[97] |

| Sunflower |

5 |

| Rhubard |

2.3 |

| Pumpkin Peels |

Microwave-Assisted Extraction |

2.67 |

[98] |

Table 4.

Summary of the WHC and OHC of pectin extracted from different sources.

Table 4.

Summary of the WHC and OHC of pectin extracted from different sources.

| Pectin Sources |

WHC (water/g powder) |

OHC (oil/g powder) |

Ref. |

| Citrus reticulata |

8.27 |

0.10 |

[78] |

| Pumpkin peels |

1.55 |

2.51 |

[99] |

| Sunflower stalk pith |

40.2 |

40.4 |

[100] |

| Tomato pomace |

3.57 |

2.65 |

[101] |

| Eggplant |

6.02 |

6.02 |

[102] |

| Walnut |

5.84 |

2.22 |

[103] |

| By-product from olive oil production |

1.87 |

6.17 |

[104] |

| Pistachio green hull |

4.11 |

2.02 |

[105] |

| Opuntia ficus indica |

4.84 |

1.01 |

[106] |

| Watermelon rind |

2 |

4 |

[107] |

| Dragon fruit peel pectin |

4.08 |

2.18 |

[108] |

| Watermelon peels |

3.65 |

1.12 |

[109] |

| Pumpkin peels |

2.65 |

1.15 |

| Pomelo peels |

4.57 |

1.49 |

| Pomegranate peels |

2.43 |

1.17 |

| Soy hull Passion fruit peel |

6.08 |

- |

[110] |

| Orange pomace |

7.57 |

- |

| Mango |

6.4 |

1.6 |

[111] |

| Pineapple |

14.6 |

0.7 |

| Royal Gala apple |

1.58 |

0.93 |

[112] |

| Cocoa Husk |

11.05 |

11.58 |

[113] |

| Red chilli peel |

4.19 |

2.02 |

[114] |

| Crab apple peel |

8.1 |

8.5 |

[115] |

Table 5.

Summary of the FTIR peaks of pectin.

Table 5.

Summary of the FTIR peaks of pectin.

| Wave number (cm-1) |

Group |

| 3200-3500 |

stretching of oxygen-hydrogen bond (–OH). |

| 2920 |

C–H bond (including CH, CH2, and CH3) vibration. |

| 1730 |

C=O stretching vibration of ester. |

| 1600-1400 |

C=O stretching vibration of carboxylate ion. |

| 1200-1000 |

C–O and C–C vibration bands of glycosidic bonds and pyranoid rings. |

| 1070 |

–COC– stretching of the galacturonic acid. |

Table 6.

Summary of FTIR results of pectin obtained from different sources.

Table 6.

Summary of FTIR results of pectin obtained from different sources.

| Pectin Source |

Extraction method |

Results |

Ref. |

| Apple pomace |

Hot acid extraction |

Results revealed that the pyranose was absent due to the extraction procedures. Ultrasound-assisted and Microwave-assisted extraction methods may partially disrupt the covalent bonds between pectin and non-pectic polysaccharides. |

[69] |

| Extraction using citric acid |

| Microwave-assisted extraction |

| Organic acid mixture |

| Ultrasound-assisted extraction |

| Citrus sinensis-Poncirus trifoliata |

Hot acid extraction |

Analysis of spectra shows that the heating type does not significantly affect the extracted pectin's structural properties. |

[70] |

| Electromagnetic induction |

| Orange peel waste |

Extraction using HCl |

Spectra of the extracted pectin exhibited consistent functional groups with the standard, although with varying intensities in some instances. |

[71] |

| Sea buckthorn peel |

Extraction using citric acid |

The peak at 1,745 cm-1 was stronger than 1,635 cm-1, indicating that sea buckthorn contains high methoxy pectin. |

[72] |

| Fălticeni’ apple Pomace |

Extraction using citric acid |

All pectin samples obtained by different extraction methods had a similar transmission pattern to those of commercial apple and citrus pectin samples. |

[73] |

| Microwave-assisted extraction |

| Ultrasound extraction with and without heat treatment |

| Enzyme-assisted extraction-ultrasound treatment. |

| Sweet lime |

Hydrothermal extraction |

The obtained results were compared with conventionally extracted pectin and commercial citrus pectin. |

[74] |

| Conventional solvent extraction |

| Lemon peels |

Extraction using HCl |

FTIR spectra of all samples were nearly identical. |

[75] |

| Sugar beet flakes |

Extraction using citric acid |

In CE pectin, the peak at 1718 cm-1 was higher when compared with the spectra of MAE and PUAE pectin samples, indicating a higher degree of esterification of the CE sample. |

[85] |

| Microwave-assisted extraction |

| Pulsed ultrasound-assisted extraction (PUAE) |

| Dragon fruit peel |

Ultrasound-assisted extraction |

Extracted pectin has functional groups similar to commercial-grade pectin and is rich in polygalacturonic acid. |

[91] |

| Saveh Pomegranate Peels |

Extraction using citric acid |

There is no significant difference between extracted pectin and standard pectin. |

[92] |

| Lemon Waste |

Extraction using Citric acid |

FTIR spectra were similar to the 55 – 70% degree of esterification of citrus pectin |

[93] |

| Passion Fruit Rinds |

Subcritical Water Extraction |

The type of solvent used in the different extraction methods affects the degree of methyl esterification. |

[117] |

| Pressurized Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents under different temperature |

| Pumpkin Peels |

Microwave Assisted Extraction |

The relative intensity of the ester band increased according to the DE of the pectin, while the intensity of the carboxylic stretching band decreased. |

[118] |

Table 7.

Summary of XRD results of pectin obtained from different sources.

Table 7.

Summary of XRD results of pectin obtained from different sources.

| Pectin Source |

Extraction method |

2θ values |

Ref. |

| Feijoa (Acca sellowiana) fruit |

Conventional Heating (CHE) |

Four characteristic peaks at 2θ = 13.14°, 21.05°, 43.41° and 50.39° were 11observed in pectin obtained by CHE method. CHE exhibited much broader and stronger diffraction peaks at 12° than MEAE and EAE samples. Besides, the peaks around about 2θ = 21.05°, 43.41°, and 50.39° in MEAE and EAE samples exhibited less sharp, and the peak at around 2θ = 13.14° was not detected. |

[76] |

| Microwave-enzyme-assisted extraction (MEAE) |

| Enzyme-assisted extraction (EAE) |

| Citrus Reticulata peels |

Microwave-assisted extraction |

Kinnow pectin is less crystalline compared to commercial pectin. Peak values were observed at 2θ = 14.31°, 37.93° and 43.16° while for commercial citrus pectin at 21.33°and 22. 57°. |

[78] |

| Coffee pulp pectin |

Acid extraction using sulfuric acid. |

Coffee pulp powder is more amorphous compared to the coffee pulp pectin. Coffee pulp pectin exhibited sharp peaks at 2θ = 15.72, 19.52, 20.90, 22.94, 25.02, 26.88, 28.44, 29.59, 31.59, 32.94, 35.88, 38.32, 44.5, 46.66, 48.2, and 51.44°. Coffee pulp pectin has a higher degree of crystallinity than coffee pulp powder. |

[89] |

| Sweet lemon peel pectin |

Microwave-assisted extraction |

Peaks observed at 2θ =12.36°, 13.96◦, 14.91◦, 19.61◦, 18.91◦, 21.36◦, 32.46◦, and 36.66◦ |

[124] |

| Orange peels |

Extraction using HCl. |

Peaks observed at 2θ =13.222°, 15.37°, 21.78°, 25.28°, 27.87° and has crystallinity value, 68.97%. |

[125] |

| Watermelon rind |

Extraction using acetic acid. |

Shows a weak characteristic diffraction peak at 2θ = 12.1° 21.3°. |

[126] |

| Orange waste |

Extraction using H2SO4. |

Pectin shows crystalline peaks in its diffractogram at 2θ = 9.5, 11.5, 20.8 28.9, 30.9, and 31.5°, which indicates that it is crystalline. |

[127] |

| Apple pomace |

Extraction using HCl. |

Pectin extracted from the Royal (Malus pumila) apple was more crystalline than Golden (Spondias dulcis). |

[128] |

| Taiwan’s Citrus depressa Hayata Peels |

Ultrasonic method |

Peaks were observed at 2θ = 16.06, 18.92, and 21.19° XRD pattern was similar to commercial pectin, only that commercial pectin showed intense peaks at 20.84, 25.59 and 30.3°. |

[129] |

| Passion Fruit Peel |

Acid Extraction (AE) |

The crystal structures of pectin extracted by AE and SEA are similar but different from those of UA and USEA. The ultrasonic-assisted process changes the crystal structure of pectin. |

[130] |

| Ultrasonic-Assisted Acid Extraction (UA) |

| Steam Explosion Pretreatment Combined with Acid Extraction (SEA) |

| Ultrasonic-assisted steam Explosion Pretreatment Combined with Acid Extraction (USEA) |

| Orange peel pectin |

Alcohol precipitation method |

Peaks observed at 2θ = 12°, 16°, 18°, 27° and 29° while by enzymatic method was 16°, 26°, 29°, and 30°. |

[131] |

Table 8.

NMR information for the characterization of pectin.

Table 8.

NMR information for the characterization of pectin.

| Instrumentation |

Results |

Ref. |

| Bruker Avance III (400 MHz) was used and applied with 400.15 MHz for 1H and 100.63 MHz for 13C, equipped with a mass probe of 7 mm H/S to collect spectral information. The NaCl powder was mixed with the sample of about 170 ±1 mg into the cylindrical zirconium dioxide rotors with an outer diameter of about 7 mm with silicon rubber tubing. |

The reference, C1, C2, C3, C4, C5 and C6 intensities were very strong. The absorption peaks at 171 ppm as COOH (protonated), 174 ppm as COOCH3, and 176 ppm as COO- (ionized form) in galacturonic acid. The signals at 101 ppm were C1 and 79 ppm as C4 of glycosidic bonds. The signals between 67–72 ppm were the pyranoid ring's C2, C3, and C5 carbon. The peak at 53 ppm was methyl carbon of COOCH3 (methyl ester). The peak at 0 ppm represents -CH3 from the dimethyl silicone rubber tubing. The % recovery between 94.33–102.77% with %RSD < 2.32 % |

[132] |

| The 13C high-resolution NMR manufactured by Bruker (Avance AV 400), applied at 400 MHz and equipped with a 4 mm outer diameter, included 62.5 kHz rf-field strength and 15 kHz as spin rate. The carbonyl peak at 176.05 ppm of glycine was a reference for all spectral data. The software MestReNova 6.1.1 was used for the analysis & interpretation. |

Resonances assign galacturonic units of C6 carbon at 176–168 ppm. Glycosidic bonds C1 and C4 carbon were indicated at 101 and 79 ppm, respectively. The pyranoid ring's other carbons C2, C3 and C5 at 67-72 ppm. The peak at 175 ppm represents the ionized form (COO-) and methyl ester pectinate. At 53 ppm, it was assigned as methyl ester’s methyl carbons. The average % recovery was 92.5%, with % RSD within the 4.4–4.9% range. |

[133] |

| The Bruker (Germany) 400 Advance Ultra 9.4 T was controlled at 400 MHz with a broad band inverse probe at 303 K. D2O was used to prepare the pectin samples (0.5%, w/w) and reference as perdeuterated 3-(trimethylsilyl) propionate sodium salt. The acquisition time was 1.98 s with a pulse of 301 and a relaxation delay time of 8 s with scans of 128, including an 8278.15 Hz as sweep width. |

A large doublet at 1.14 ppm was assigned as isopropanol, used to separate pectin from aqueous solutions as a precipitate. At 4 ppm, it also contributed significantly. The methoxy group containing proton in the esterified pectin showed at 3.78 ppm, which enhanced the degree of esterification. The proton H–2 and H–3 were assigned at 3.7 and 3.96, respectively. The two signals at 4.9 and 3.96 ppm are H-5 protons near galacturonic acid. At 4.6 ppm for H-5, protons adjacent to ester groups shifted downhill to about 5.0 ppm. |

[134] |

Table 9.

Comparison considering different parameters: yield, color, moisture, protein content, galacturonic acid and methoxyl content.

Table 9.

Comparison considering different parameters: yield, color, moisture, protein content, galacturonic acid and methoxyl content.

| Extraction Method |

Yield |

Color |

Moisture |

Protein Content |

Galacturonic Acid |

Methylxyl Content |

| UAE |

M-to-H |

MR |

H |

V |

V |

M-to-H |

| PUAE |

H |

HR |

L |

H |

H |

H |

| REF |

M |

MR |

H |

V |

V |

V |

| MEF |

H |

MR |

M |

M |

H |

M |

| MAE |

H |

MR |

H |

H |

M |

H |

| SWE |

M-to-H |

MR |

H |

V |

H |

M |

| EAE |

H |

MR |

H |

H |

M |

H |

Table 10.

The comparison considers different parameters: degree of esterification, polydispersity index, equivalent weight, molecular weight, acetyl value, oil holding capacity, and water holding capacity.

Table 10.

The comparison considers different parameters: degree of esterification, polydispersity index, equivalent weight, molecular weight, acetyl value, oil holding capacity, and water holding capacity.

| Extraction Method |

Degree of Esterification |

Polydispersity Index |

Equivalent Weight |

Molecular Weight |

Acetyl Value |

Oil Holding Capacity |

Water Holding Capacity |

| UAE |

M |

L-to-M |

V |

V |

V |

M |

H |

| PUAE |

M |

L |

V |

H |

V |

H |

H |

| REF |

H |

H |

H |

H |

H |

M |

M |

| MEF |

M |

L-to-M |

H |

V |

V |

M-to-H |

M |

| MAE |

M |

L |

V |

L |

V |

H |

H |

| SWE |

V |

L |

V |

V |

L |

M |

H |

| EAE |

H |

L |

V |

H |

H |

H |

VH |

Table 11.

Non-conventional techniques are used for the extraction of pectin from different food sources.

Table 11.

Non-conventional techniques are used for the extraction of pectin from different food sources.

| Technique |

Pectin source |

Yield (%) |

GalA (%) |

Ref. |

| OHAE |

Pomegranate |

8.1 |

83 |

[166] |

| UAME |

Potato |

23 |

42 |

[170] |

| Tomato |

34 |

69 |

[171] |

| Watermelon |

19 |

68 |

[172] |

| UAOHE |

Grape |

27 |

|

[176] |

| HT |

Sugar beet pulp |

13.6 |

|

[177] |

| lime peels |

23.8 |

70.6 |

[74] |

| DBDE |

Watermelon rinds |

18.5 |

80 |

[182] |

Table 12.

Comparison between different non-conventional extraction techniques in terms of advantages and disadvantages.

Table 12.

Comparison between different non-conventional extraction techniques in terms of advantages and disadvantages.

| Techniques |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| UAE |

Processing times are reduced since UAE extraction methods are more efficient than traditional methods. The yields of extracting bioactive components can be increased by UAE's improved solvent penetration. UAE is more cost-effective and advantageous for the environment as it uses less solvent. The UAE approach preserves the purity of delicate chemicals by minimizing heat exposure. The UAE's efficacy could be preserved when scaled up for industrial use. |

Initially, purchasing ultrasonic equipment might be expensive, and adjusting parameters like frequency, power, and duration to achieve the required results could be challenging. Sensitive materials may degrade when exposed to high-intensity ultrasound. Despite its ability to speed up processing, the UAE may use significant energy when operating. It might not be compatible with all materials or substances. May result in the degradation of some phenolic acids. |

| PUAE |

When compared to traditional extraction techniques, PUAE usually delivers larger pectin yields because of its superior solubilization and release from cell walls. The method greatly cuts down on extraction time, increasing process efficiency. Because pulsed ultrasound is mild, pectin's quality and functional qualities are preserved, allowing it to continue gelling and thickening. It may be more energy-efficient because the pulsed technique permits regulated energy delivery instead of continuous exposure. |

The hefty initial cost of ultrasonic equipment may deter smaller labs and organizations. To achieve ideal results with PUAE, rigorous parameter adjusting (such as solvent type, frequency, and pulse duration) is required, which can take time. Not every material or contaminant may be eliminated with PUAE. Some people may respond negatively to ultrasonography. |

| PEF |

PEF may greatly enhance the yield of extracted chemicals and is quicker than traditional procedures, resulting in more efficient processing. PEF can help to protect the integrity and purity of delicate substances since it functions at lower temperatures. The dry solid content increased over the lengthier "OFF" time as compared to the control studies. |

Investing in specialized equipment might be costly for small businesses. The usefulness of PEF to some plant sources may be limited since not all substances respond well to it. Excessive exposure to electric fields may damage sensitive components, reducing the quality of the extract. |

| MEF |

|

When it comes to extracting chemicals, especially those that are difficult to remove, MEF may not be as effective as PEF. MEF still needs certain equipment, which not all facilities may have, even if it is less complex than PEF. The use of MEF may be restricted to particular plant matrices or substances since not all materials may react properly with it. |

| MAE |

MAE increases the release and solubility of bioactive compounds, resulting in increased yields. It maintains the integrity of fragile materials by shielding them from light and heat. Removes airborne contaminants. It needs very little training. Prevents the loss of volatile chemicals. Minimal costs for investments. |

Factors such as solvent type, time, and microwave power must be carefully controlled to achieve the optimum results. Certain compounds may degrade under microwave conditions, and not all materials may respond well to microwave extraction. Trained staff are required to correctly operate and utilize the equipment for the most demanding operations. |

| SWE |

It is an environmentally friendly and sustainable extraction technique because SWE employs water as its main solvent instead of hazardous organic solvents. The technique's improved solubility and diffusion often lead to better extraction yields than traditional approaches. SWE often extracts faster, increasing processing efficiency overall. Certain substances can be extracted selectively by adjusting the temperature and pressure according to their solubility properties. Because it reduces solvent waste, the method is economical and ecologically safe. |

Specialized high-pressure equipment might be costly initially. The temperature and pressure parameters must be carefully adjusted to get the best extraction results. This approach requires careful monitoring and is inappropriate for extracting thermo-labile chemicals since sensitive molecules may break down at higher temperatures. Not all compounds can be extracted using SWE; some may need a different solvent solution. |

| OHAE |

Uniform heating minimizes thermal degradation. Lower maintenance costs. Shorter overall processing time. Improved extraction yields. |

|

| UAME |

Reduced solvent requirement. Shorter extraction time. Higher extraction efficiency and improved yield. Cost-effective and environmentally friendly. |

Initial investment in specialized equipment is high. There is a need for carefully controlled heating to avoid degradation. Potential limitations in scaleup. |

| UAOHE |

|

|

| HT |

Environmentally friendly. Safer and more sustainable. Simple and overall cost-effective. ∙ |

Energy-intensive. Low extraction efficiency. Risk of thermal degradation of pectin. Sensitive to variations in temperature and pressure. |

| HPPE |

|

High operation and maintenance costs. Sensitive to variations in pressure. Scaling up is challenging. |

| DBDE |

Solvent-free and eco-friendly. Suitable for keeping the integrity of pectin. Improved yield and purity. ∙ |

|

Table 13.

Applications of various non-conventional extraction techniques.

Table 13.

Applications of various non-conventional extraction techniques.

| Industry Type |

Applications |

| Food Industry |

Extraction of flavours and aromas. Used widely in the food industry to extract biological components, tastes, and juices from fruits and vegetables. Eliminating fruits and vegetables' flavours, hues, and antioxidants. Extracting the nutritious ingredients, flavours, and aromas from fruits, vegetables, and grains. |

| Pharmaceuticals |

Isolation of active ingredients. Extracting bioactive compounds with potential health benefits. Vitamins, pigments, and other bioactive compounds in a range of industries, including food, medicine, and cosmetics. To create new medications, the active components in medicinal plants are separated. Extracting biological components, flavours, and antioxidants from herbs, fruits, and vegetables. Separating active components in medicinal plants to create new medications. Isolation of the bioactive ingredients of medicinal plants to make new medications. |

| Cosmetics and Personal Care |

Extraction of bioactive ingredients. Extracting bioactive compounds with potential health benefits. Extraction of the bioactive ingredients found in skincare and cosmetic products. Extraction of natural ingredients for skincare and cosmetics. Extraction of natural ingredients for use in skincare and cosmetics products. |

| Environmental Applications |

|

| Nutraceuticals |

|

| Biofuels |

|