1. Introduction

The Rutaceae family includes a wide range of citrus fruits, among which lemon (

Citrus limon) is one of the most widely consumed and economically significant species. Globally, lemons rank as the third most important citrus crop after oranges, with an annual production exceeding 4.4 million tons. Argentina is the world’s leading producer, contributing more than 1.2 million tons per year. Algeria also plays a crucial role in citrus cultivation, particularly of the Eureka lemon variety, due to its favorable climate and long-standing agricultural tradition [

1]. Lemons are rich in bioactive compounds such as ascorbic acid, citric acid, flavonoids, pectin, and essential oils. Notably, the peel contains a high concentration of phytochemicals, including sitosterol, glycosides, and volatile aromatic compounds. These constituents contribute to the antioxidant and antifungal properties of lemon, largely due to their polyphenolic and monoterpene content [2, 3].

Citrus essential oils (CEOs), especially those extracted from the peel, are dominated by monoterpenes like limonene and are typically present at 0.6% to 3.8% of the peel’s dry weight. CEOs exhibit well-documented antimicrobial, antifungal, and antioxidant activities, making them promising candidates for applications in the food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries [

3]. However, their practical use is limited by several factors including volatility, light and temperature sensitivity, and oxidative degradation, which significantly reduce their shelf life and effectiveness.

To address these limitations, encapsulation technologies have been increasingly employed to enhance the stability and controlled release of essential oils. Among natural biopolymers, pectin stands out due to its biocompatibility, gelling properties, and regulatory approval for use in food products. Pectin-based hydrogels are capable of encapsulating and protecting active compounds, and have shown potential in food preservation, agriculture, and drug delivery systems [4, 5].

Recent advancements suggest that ultrasound-assisted modification of biopolymers can improve their encapsulation performance. Ultrasound treatment induces partial depolymerization and structural rearrangement of pectin chains, potentially increasing their ability to form more uniform and stable gel matrices. This enhances both the mechanical integrity and encapsulation efficiency of the final product [

3].

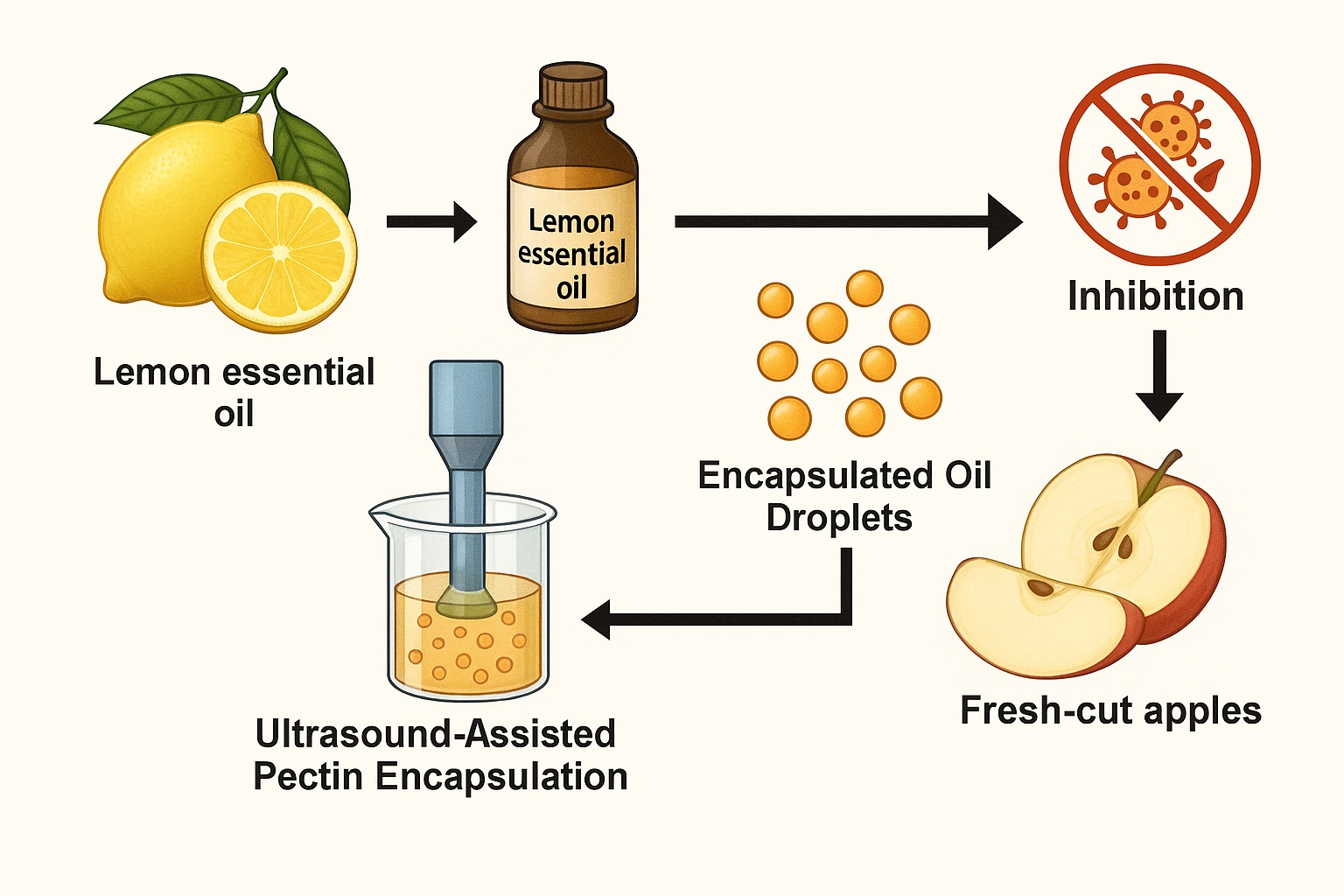

In addition to encapsulation performance, this study extends the application scope of pectin-encapsulated lemon essential oil to a real food model. Specifically, fresh-cut apples were selected as a representative example of IV gamma (minimally processed) products, which are highly susceptible to enzymatic browning and microbial spoilage. Incorporating the EO-loaded capsules into this food matrix enabled the practical evaluation of their antioxidant and antimicrobial functionalities under refrigerated storage.

In this context, the present study aims to: (i) extract and chemically characterize lemon (Citrus limon) essential oil, (ii) evaluate its antioxidant and antifungal properties, (iii) optimize its encapsulation using ionotropic gelation of pectin, with and without ultrasound pretreatment, and (iv) assess its performance in preserving the quality of fresh-cut apple slices during cold storage. Particular emphasis is placed on morphological analysis of the resulting microcapsules using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), with the goal of developing a more effective and scalable encapsulation strategy for bioactive compound delivery in food and pharmaceutical applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

Lemon fruits (Citrus limon, Eureka variety) were harvested from the Constantine region of Algeria. The zest (flavedo) was manually separated from the albedo and used for essential oil extraction. The albedo was dried in a ventilated oven at 60 °C, ground using a Moulinex grinder, and used for pectin extraction [

6].

2.2. Essential Oil Extraction via Hydrodistillation

Essential oil was extracted from 100 g of fresh lemon zest using a Clevenger-type apparatus with a peel-to-water ratio of 1:3. The mixture was heated until oil condensation ceased. The recovered essential oil was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and stored in amber vials at 4 °C for further analysis. The essential oil yield was calculated using Equation (1) [

7]:

2.3. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Analysis

Chemical composition was determined using an Agilent 6890N GC system coupled with a flame ionization detector (FID) and an HP-5 capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm, 0.25 μm film). Helium was used as the carrier gas at 1.0 mL/min. The injector temperature was 250 °C. The oven program began at 45 °C (8 min hold), ramped to 250 °C at 8 °C/min, and held isothermally for 10 min. Mass spectrometry (MS) was performed at 70 eV with an interface temperature of 280 °C. Samples were injected in split mode (1:20), and 0.1 μL of pure oil was analyzed. Component identification was based on linear retention indices (LRIs) compared to literature and NIST/Wiley spectral libraries (Adams, 2007). LRIs were calculated using a standard mixture of n-alkanes (C8–C30). In some cases, identification was confirmed using reference standards or polarity comparison with a second GC column [

8].

2.4. Antibacterial Activity Assay

The antibacterial activity was assessed using the disk diffusion method. Sterile filter paper disks (4 cm diameter) were impregnated with 5 μL of essential oil and placed on Mueller-Hinton agar plates previously inoculated with 18-hour bacterial cultures. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Gentamicin and DMSO were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Inhibition zones were measured in millimeters. All assays were performed in triplicate [

9].

2.5. Antifungal Activity Assay

The antifungal activity was tested against Fusarium oxysporum, Aspergillus niger, Botrytis sp., and Penicillium sp. Essential oil was incorporated into Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium at final concentrations of 0.3%, 0.15%, and 0.075%. Control groups included PDA with DMSO (positive control) and plain PDA (negative control). A 5 mm fungal disk was placed in the center of each plate and incubated at 25 °C for 6 days. Fungal growth inhibition was calculated using Equation (2):

Where C is the radial growth in the control and T is the radial growth in the treatment [

10].

2.6. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay

The DPPH assay was conducted using a 0.1 mM ethanolic DPPH solution. A 160 μL aliquot of DPPH solution was mixed with 40 μL of essential oil at different concentrations. After 30 min of incubation at room temperature, absorbance was measured at 570 nm. Scavenging activity was calculated using Equation (3):

where C is the control absorbance and T is the test absorbance [

11].

2.7. ABTS Radical Scavenging Assay

ABTS solution was prepared by reacting ABTS with potassium persulfate and incubating in the dark for 12–16 h. The absorbance was adjusted to 0.700 ± 0.020 at 734 nm. A 40 μL essential oil sample was added to 160 μL of ABTS solution. Absorbance was recorded after 10 min [

12].

2.8. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

The reducing power was determined by mixing 10 μL of oil with 40 μL phosphate buffer (pH 6.6) and 50 μL potassium ferricyanide (1%). After incubation at 50 °C for 20 min, 50 μL trichloroacetic acid (10%) was added. Then, 40 μL water and 10 μL ferric chloride (0.1%) were added. Absorbance was measured at 700 nm [

13].

2.9. Phenanthroline Assay

In this assay, 10 μL essential oil was mixed with 50 μL FeCl₃ (0.2%), 30 μL phenanthroline (0.5%), and 110 μL methanol. After 20 min of dark incubation at 30 °C, absorbance was measured at 510 nm using BHT as the reference [

14].

2.10. Silver Nanoparticles (SNP) Assay

Silver nanoparticles were synthesized by boiling 50 mL of 1 mM AgNO₃ and adding 5 mL of 1% trisodium citrate until the solution turned pale yellow. For the assay, 20 μL of oil was mixed with 130 μL SNP solution and 50 μL water. Absorbance was measured at 423 nm after 30 min [

15].

2.11. Encapsulation Process via Ionotropic Gelation

A 2% (w/v) pectin solution was prepared and stirred magnetically for 30 min. A portion of this solution was treated ultrasonically at 40 kHz and 100 W for 10 min using a VWR ultrasonic cleaner. The remaining solution served as a non-treated control. Lemon essential oil (10% v/v) was emulsified into both pectin solutions. The emulsion was dropped into a 2% (w/v) CaCl₂ solution using a syringe with a 0.5 mm needle. Capsules formed by ionic gelation were left to dry for 30 min, rinsed, and air-dried for 24 h. To determine encapsulation efficiency, 10 mg of capsules were mixed with 4 mL of 2 M HCl and heated at 95 °C for 30 min. After cooling, 2 mL ethanol was added and the sample was centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was analyzed at 275 nm using UV-visible spectrophotometry, and oil content was quantified against a standard curve [

16]. Encapsulation efficiency was calculated using Equation (4):

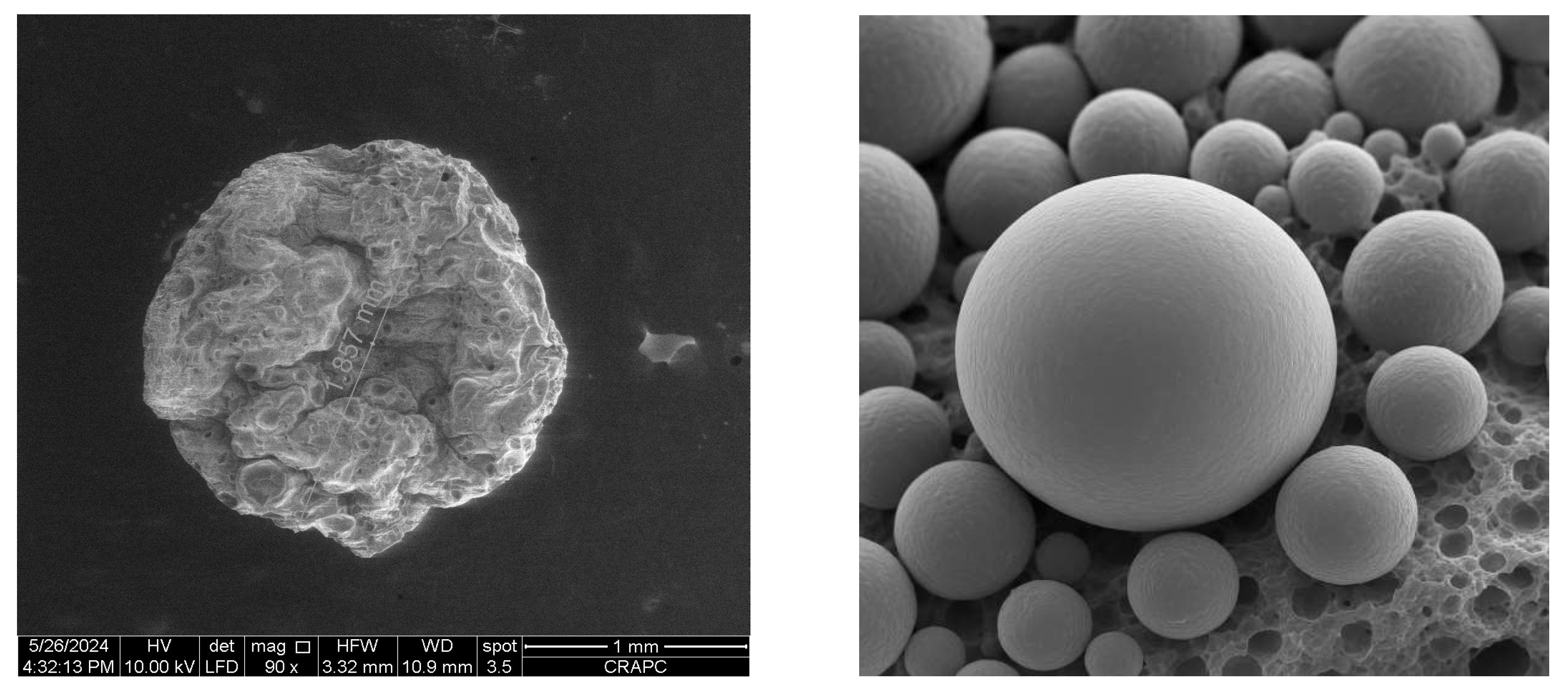

2.12. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Capsule morphology was analyzed using a Quanta 250 SEM (FEI) with a tungsten filament, operated at 10–15 kV in low-vacuum mode. Dried samples were mounted on aluminum stubs with carbon adhesive tape and observed without gold coating.

2.13. Preparation of Apple Slices and Treatments

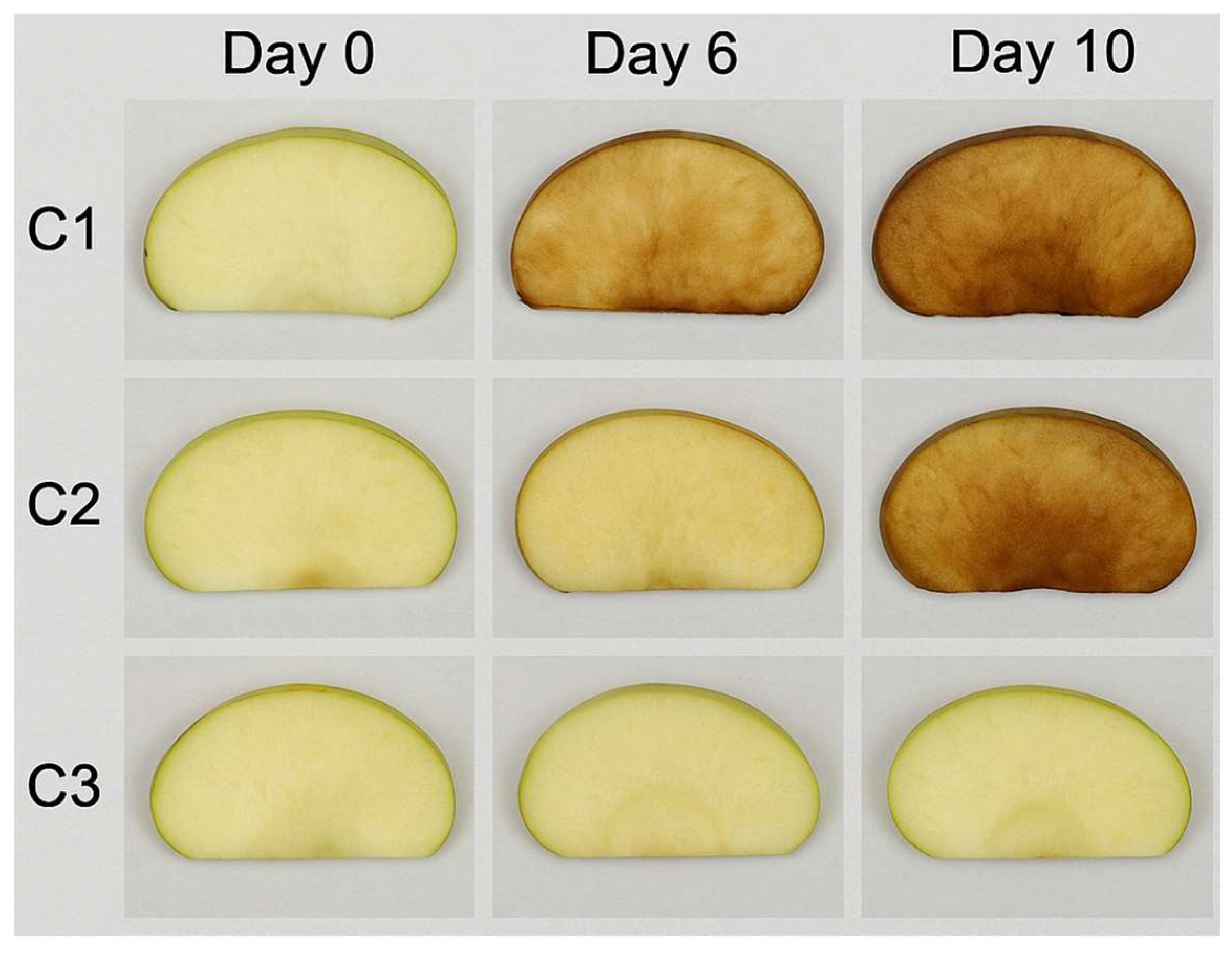

Fresh, uniformly sized Malus domestica apples were selected, washed under Fresh, uniformly sized Golden Delicious apples (Malus domestica Borkh.) were selected due to their widespread commercial use and high susceptibility to enzymatic browning, making them an ideal model for evaluating anti-browning strategies. Apples were washed under running tap water, peeled, and manually sliced into rectangular pieces approximately 4 × 1 × 1 cm using a sterile stainless-steel knife. The slices were randomly assigned to three treatment groups:

Control (C1): no treatment.

Blank capsule group (C2): immersion for 1 minute in a 2% (w/v) aqueous suspension of pectin-based capsules without essential oil.

EO-capsules (C3): immersion for 1 minute in a 2% (w/v) aqueous suspension of pectin-based capsules containing lemon essential oil.

The aqueous suspensions were prepared by dispersing the dried capsules in sterile distilled water under mild magnetic stirring for 10 minutes to ensure uniform distribution. After immersion, the slices were dried under sterile laminar airflow for 5 minutes and packed in sterile polyethylene food-grade containers (3 slices per container). All samples were stored at 4 ± 1 °C and 75% relative humidity for up to 10 days.

2.14. Color and Visual Browning Assessment

Color parameters (L*, a*, b*) were measured using a CR-5 Konica Minolta colorimeter (Minolta Co., Osaka, Japan). For each sample, three readings were taken from the cut surface, and the average was recorded.

Visual browning was assessed by two trained evaluators using a 5-point scale:

0 = no browning

1 = slight browning (<25%)

2 = moderate browning (25–50%)

3 = extensive browning (50–75%)

4 = severe browning (>75%)

Photographs were taken at each sampling point to document visual evolution.

2.15. Microbial Load Evaluation

Microbial analyses were conducted on days 0, 3, 6, and 10. For each treatment, 3 slices were aseptically transferred into sterile stomacher bags containing 90 mL of buffered peptone water and homogenized for 2 minutes. Serial dilutions were plated on:

PCA plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h, and PDA plates at 25 °C for 72 h. Results were expressed as log CFU/g.

2.16. Weight Loss and Firmness

Slices were weighed at T0 and at each sampling point (3, 6, 10 days) using a precision balance. Weight loss was calculated as a percentage relative to the initial weight: using Equation (5):

where W

0is the initial weight and W

t is the weight at time t.

Firmness was measured using a digital penetrometer (TR Snc., Forlì, Italy) with an 8 mm cylindrical probe, penetrating to a depth of 5 mm at a speed of 1 mm/s. Three measurements per slice were averaged.

2.17. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (version XX, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of data distribution was verified using the Shapiro–Wilk test. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to determine statistically significant differences between treatment groups across time points. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

For microbial counts, results were log-transformed before analysis to ensure homoscedasticity. Non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests were applied in cases where ANOVA assumptions were not met. Interventionary studies involving animals or humans, and other studies that require ethical approval, must list the authority that provided approval and the corresponding ethical approval code.

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Composition of Lemon Essential Oil

Hydrodistillation of Citrus limon (Eureka variety) peel yielded 3.85% essential oil (EO). GC-MS analysis identified 31 compounds, representing over 95% of the total oil composition. Limonene was the predominant component (56.18%), followed by β-pinene (9.89%), γ-terpinene (9.75%), β-bisabolene (3.01%), α-pinene (2.89%), and β-myrcene (2.54%) (

Table 1). The monoterpene-rich profile suggests high volatility and biological activity potential.

Area values are expressed as mean percentage ± standard deviation (SD), (n = 3).

3.2. Antibacterial Activity

The EO exhibited significant antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (

Table 2). Bacillus cereus and Staphylococcus aureus showed the highest sensitivity, with inhibition zones of 29.1 ± 1.15 mm and 26.6 ± 1.60 mm, respectively. Escherichia coli (16.5 ± 0.41 mm) and Salmonella spp. (9 ± 0.86 mm) were moderately inhibited.

Results are expressed as mean inhibition zone diameter ± standard deviation (mm); n = 3.

3.3. Antifungal Activity

The EO demonstrated dose-dependent antifungal activity against Fusarium oxysporum, Aspergillus niger, Botrytis sp., and Penicillium sp. (

Table 3). At 0.3% concentration, inhibition rates reached 59.3% for Botrytis sp. and 58.18% for A. niger. Lower concentrations showed proportionally reduced activity, with the least effect observed against F. oxysporum.

Results represent mean percentage growth inhibition after 6 days of incubation; n = 3.

3.4. Antioxidant Activity

The EO showed moderate to strong antioxidant activity across five assays (

Table 4). IC₅₀ values were 28.43 ± 0.14 µg/mL (DPPH) and 35.01 ± 0.11 µg/mL (ABTS), indicating radical scavenging ability. The reducing power (A₀.₅ = 66.59 ± 0.45 µg/mL), phenanthroline assay (A₀.₅ = 187.84 ± 0.34 µg/mL), and SNP assay (A₀.₅ = 29.67 ± 0.05 µg/mL) confirmed the presence of electron-donating compounds with redox potential.

Results are expressed as IC₅₀ or A₀.₅ (µg/mL). Lower values indicate higher antioxidant activity. ND: Not detected.

3.5. Encapsulation Efficiency

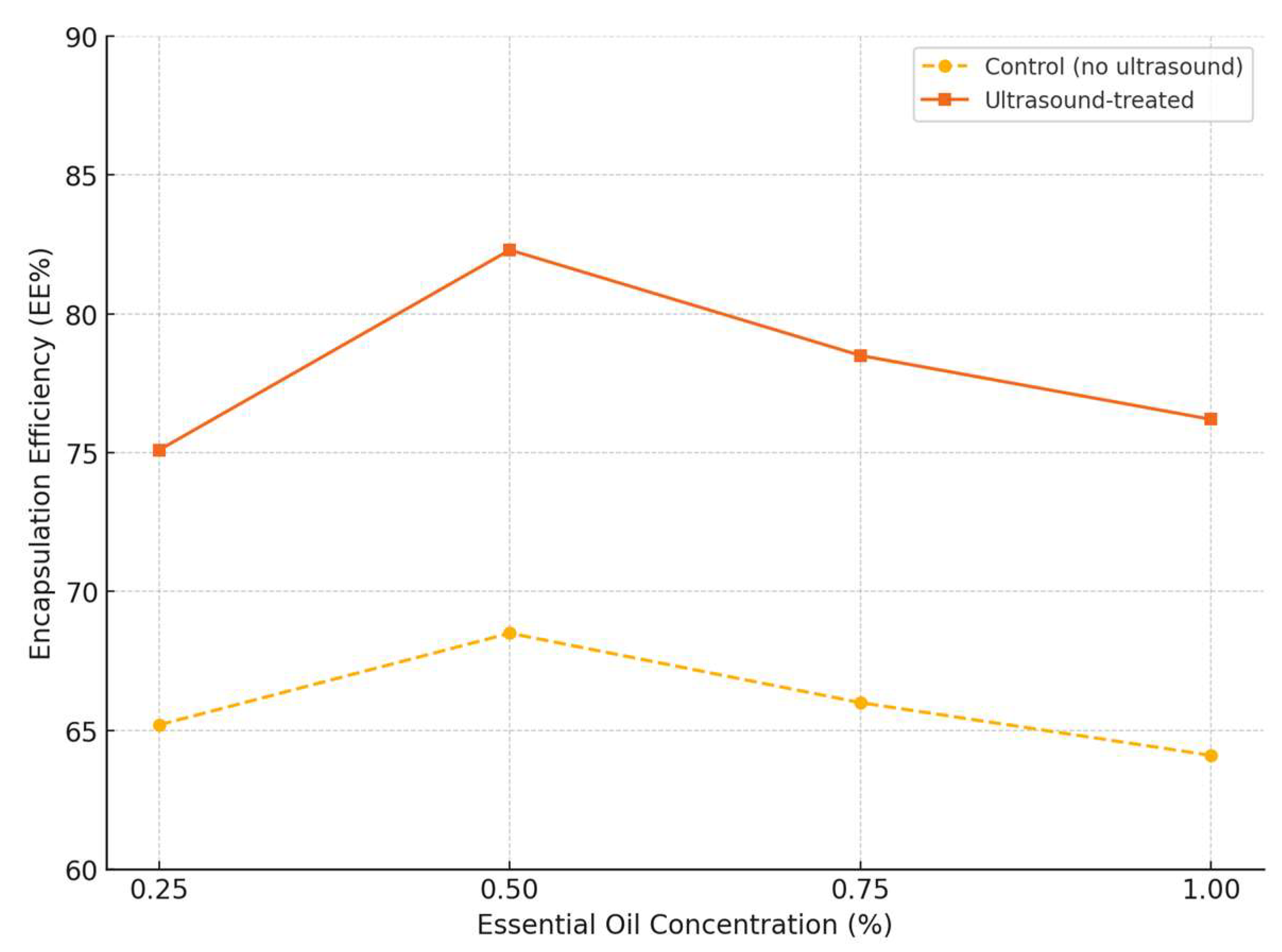

As shown in

Figure 1, ultrasound-assisted encapsulation yielded significantly higher encapsulation efficiency (EE%) values. The highest EE (82.3%) was recorded for the ultrasound-treated group at 0.5% essential oil concentration, compared to 68.5% for the control. A slight decrease in EE was observed at higher oil concentrations, likely due to matrix saturation or surface oil leakage.

SEM images revealed clear morphological differences and confirmed the improved morphology and surface regularity of ultrasound-assisted microcapsules (

Figure 2). Non-ultrasound-treated capsules exhibited irregular, collapsed structures with porous and rough surfaces. In contrast, ultrasound-treated capsules were spherical, compact, and smoother, with minimal surface deformation. This morphological uniformity is consistent with enhanced gelation and structural integrity.

The findings of this study underscore the effectiveness of lemon essential oil (EO), particularly from the Eureka variety, as a bioactive agent with multiple functional properties, and further validate ultrasound-enhanced pectin encapsulation as a promising strategy for its stabilization and delivery.

3.6. Evaluation of EO-Loaded Pectin Microcapsules in a Food Model

To evaluate the effectiveness of pectin-based microcapsules containing lemon essential oil (EO) in a food application, fresh-cut apple slices were used as a model system for minimally processed (IV gamma) products. The objective was to assess the capacity of encapsulated EO to delay enzymatic browning, inhibit microbial growth, and preserve physical quality during refrigerated storage. Visual inspection revealed progressive browning across all samples over 10 days at 4 °C, with clear differences among treatments. On day 6, untreated control slices (C1) exhibited moderate to severe browning (score: 2.8 ± 0.2), whereas slices treated with EO-loaded pectin capsules (C3) maintained significantly better visual quality (score: 1.2 ± 0.3, p < 0.05). Slices treated with empty pectin capsules (C2) showed intermediate browning (score: 2.3 ± 0.2). Colorimetric analysis supported these findings. Although L* values (lightness) decreased in all groups over time, C3 retained significantly higher values. On day 10, C3 had an L* of 69.3 ± 1.1, compared to 59.4 ± 1.8 in C1 (p < 0.05), indicating delayed browning. The a* parameter (redness) increased more rapidly in C1, consistent with enzymatic oxidation. Microbial growth also differed markedly among groups. At day 10, total aerobic bacteria in C1 reached 6.5 ± 0.4 log CFU/g, significantly higher than in C2 (5.8 ± 0.3) and C3 (4.9 ± 0.2) (p < 0.05). Fungal counts followed a similar pattern, with the lowest levels observed in C3 (3.1 ± 0.3 log CFU/g), confirming the antifungal efficacy of encapsulated EO. Weight loss increased progressively during storage. By day 10, C1 experienced the highest moisture loss (6.4% ± 0.5), while C3 had the lowest (4.2% ± 0.3), demonstrating a moisture-retention effect of the EO-containing capsules (p < 0.05). Firmness declined in all samples over time, but was best preserved in the EO-treated group. On day 10, C3 maintained a firmness of 2.3 ± 0.1 N compared to 1.4 ± 0.2 N in C1 (p < 0.05). EO-loaded pectin microcapsules significantly improved the visual appearance, microbiological safety, and physical integrity of fresh-cut apples during refrigerated storage. The low variability among replicates underscores the reliability of these experimental findings (

Figure 3).

Values are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Different superscript letters within the same row indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) based on Tukey’s test.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study underscore the effectiveness of lemon essential oil (LEO), particularly from the Eureka variety, as a bioactive agent with multiple functional properties, and further validate ultrasound-enhanced pectin encapsulation as a promising strategy for its stabilization and delivery.

4.1. Chemical Profile and Bioactivity

The dominance of limonene (>56%) in the Citrus limon (Eureka) essential oil are in agree with previous compositional analyses reported for lemon peels from similar cultivars [

17,

18]. This terpene-rich chemotype—characterized by high levels of limonene, γ-terpinene, and β-pinene, has been consistently linked to strong antimicrobial and antioxidant potentials. Monoterpenes such as limonene, γ-terpinene, and β-pinene are recognized for their membrane-disruptive mechanisms, which explain the antibacterial and antifungal activities observed. High activity against B. cereus and S. aureus supports the hypothesis that EO hydrophobicity allows diffusion through Gram-positive cell walls, destabilizing cytoplasmic membranes and causing leakage of ions and ATP. [

19,

20]

4.2. Antifungal Specificity

The antifungal effect varied among strains, with A. niger and Botrytis sp. more susceptible than F. oxysporum, consistent with previous findings [

21,

22]. This selectivity likely arises from differences in cell wall structure, ergosterol content, and antioxidative defenses. The essential oil’s components may induce oxidative stress by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to membrane damage and cell death. Additionally, synergistic interactions between limonene and minor compounds such as myrcene and bisabolene may enhance membrane permeability, resembling the mechanism of combination antifungal therapies.

4.3. Antioxidant Mechanisms

Lemon EO exhibited promising antioxidant capacity compared to standard antioxidants such as BHT and Trolox, a finding in line with previous reports on citrus essential oils [

23]. The dominance of non-polar monoterpenes like limonene and γ-terpinene—while less effective in single-electron transfer mechanisms—still contributes to moderate DPPH and ABTS scavenging activities via hydrogen atom donation. Notably, the SNP assay, applied here for the first time in this context, revealed metal-chelating potential, which is particularly relevant in preventing lipid peroxidation in food matrices or biological systems. The relatively weaker responses observed in the FRAP and phenanthroline assays may stem from the limited electron-donating capacity of terpenoids compared to polyphenolic compounds, which are largely absent in EO compositions [

24]. This profile underscores the complex and multifaceted antioxidant behavior of lemon EO, where different mechanisms (radical scavenging vs. metal chelation) may dominate depending on the assay system.

4.4. Effect of Ultrasound-Assisted Encapsulation

Ultrasonic pretreatment significantly enhanced encapsulation efficiency and morphology. Ultrasound-induced cavitation and partial depolymerization of pectin likely increased chain mobility and solubility, improving crosslinking with Ca²⁺. This also promoted EO dispersion within the matrix, minimizing phase separation and surface oil loss. SEM imaging confirmed that ultrasound-treated capsules were more uniform and spherical—structural traits conducive to delayed release and stronger barrier properties.

4.5. Validation in Food Model

The use of EO-loaded microcapsules on fresh-cut apples confirmed their functionality in real food systems. The strong reduction in browning and microbial growth observed matches with findings by [

25], who reported that lemon essential oil significantly delayed browning in fresh-cut apples through suppression of polyphenol oxidase activity and oxidative stress mitigation. Similarly, authors [

26] found that lemon EO encapsulated in chitosan-based films reduced microbial load in minimally processed apples during storage, mirroring our reductions in both bacterial and fungal counts. The higher L* values and lower a* values in C3-treated slices support the visual preservation attributed to EO’s antioxidant action, particularly limonene, which has been reported to stabilize phenolic substrates [

27]. Our findings that pectin-only capsules (C2) had intermediate effects are consistent with [

28], who suggested that pectin matrices contribute to barrier properties and moisture regulation but lack intrinsic bioactivity without incorporated agents. The improvement in weight retention and firmness in the C3 group is also corroborated by studies using EO-based edible coatings to limit water loss and enzymatic softening in fruits [

29,

30]. These outcomes suggest that the encapsulated EO acts both as a biochemical agent and as a structural modulator at the fruit surface.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that essential oil extracted from Citrus limon (Eureka variety) possesses significant antioxidant and antifungal properties, largely attributed to its rich composition in monoterpenes, particularly limonene, β-pinene, and γ-terpinene. The essential oil effectively inhibited the growth of several pathogenic fungal strains and exhibited moderate to strong free radical scavenging and reducing activities across multiple assays. These results confirm its potential as a natural preservative and antimicrobial agent.

Encapsulation using pectin via ionotropic gelation proved to be an effective method for stabilizing the volatile oil. Notably, ultrasound-assisted pretreatment of the pectin solution led to a substantial improvement in encapsulation efficiency (up to 82.3%) and resulted in microcapsules with enhanced morphological uniformity and mechanical integrity, as evidenced by SEM analysis. These findings support the hypothesis that ultrasonic cavitation modifies pectin structure, enhancing polymer interactions and the overall performance of the delivery system.

Importantly, the application of these microcapsules in a food model—fresh-cut apple slices—confirmed their functionality under realistic storage conditions. EO-loaded capsules delayed enzymatic browning, reduced microbial growth, and preserved firmness and moisture content significantly better than both untreated samples and those treated with empty pectin capsules. These results demonstrate the dual advantage of EO’s bioactivity and pectin’s barrier properties in improving shelf life and sensory quality.

This work also contributes to the valorization of citrus processing by-products, demonstrating a sustainable approach to converting lemon peel waste into functional bioactive ingredients with potential applications in food preservation, nutraceuticals, and active packaging systems.

Future studies should explore the release kinetics of the encapsulated oil under simulated gastrointestinal and food storage conditions, its compatibility with various food matrices, and long-term stability in packaging applications. Further investigation into consumer acceptability and regulatory compliance will also be essential for industrial translation.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, D.R. , L.H. and L.R.; methodology, R.D, L.H. and L.R.; software, S.M. and M.D.E.; validation, R.D. , L.H. and L.R.; formal analysis, R.D., M.D.E., N.A., A.K., M.A.M.; investigation, R.D., M.D.E., N.A., A.K., M.A.M. and L.H.; resources, R.D., L.R. and L.H.; data curation, R.D., S.M., M.D.E and L.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.D., S.M., L.R., L.H; writing—review and editing, R.D., M.D.E., L.R. and L.H; visualization, R.D.; supervision, L.R and L.H.; project administration, L.R. and L.H..; funding acquisition, L.R. and L.H.

Funding

This project was funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.4—Call for tender No. 3138 of 16 December 2021, rectified by Decree n.3175 of 18 December 2021 of Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the Europe-an Union—NextGenerationEU; Award Number: Project code CN_00000033, Concession Decree No. 1034 of 17 June 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, CUP: D43C22001260001, Project title “National Biodiversity Future Center—NBFC”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of the doctoral thesis research of DjerriRofia at Brothers Mentourı 01 University, Department of Food Biotechnology, Institute of Nutrition, Food and Agro-Food Technologies (INATAA). The Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research of Algeria is gratefully acknowledged

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). FAOSTAT: Crops and livestock products. FAOSTAT 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Sania, R.; Mona, H.; Mughal, S.; Khurram, H.; Nageena, S.; Sumaira, P.; Maryam, M.; Farman, M. Biological attributes of lemon: A review. J. Addict. Med. Ther. Sci. 2020, 6, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Barzee, T.J.; Zhang, R.; Pan, Z. Citrus. In Integrated Processing Technologies for Food and Agricultural By-Products; Pan, Z., Zhang, R., Zicari, S., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 217–242. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, F.L.; Santos, M.; Rocha, S.M.; Trindade, T. Encapsulation of essential oils in SiO₂ microcapsules and release behaviour of volatile compounds. J. Microencapsul. 2014, 31, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, M. Pectin-Based Biodegradable Hydrogels with Potential Biomedical Applications as Drug Delivery Systems. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 2011, 2, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. , Sampers, I.; Raes, K. Isolation of Pectin from Clementine Peel: A New Approach Based on Green Extracting Agents of Citric Acid/Sodium Citrate Solutions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 833–843.

- Tuan, N.T.; Dang, L.N.; Huong, B.T.C.; Danh, L.T. One Step Extraction of Essential Oils and Pectin from Pomelo (Citrus grandis) Peels. Chem. Eng. Process. Process Intensif. 2019, 142, 107550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensouici, C.; Boudiar, T.; Kashi, I.; Bouhedjar, K.; Boumechhour, A.; Khatabi, L.; Larguet, H. Chemical Characterization, Antioxidant, Anticholinesterase and Alpha-Glucosidase Potentials of Essential Oil of Rosmarinus tournefortii de Noé. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2020, 14, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.A.; Gergees, S.G.; AL-Hammadi, A.T.Y. The Inhibitory Effect of Some Plant Essential Oils on the Growth of Some Bacterial Species. Rev. Bionatura 2023, 8, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Sadaoui-Smadhi, N.; Debbi, A.; Bensouici, C.; Belhi, I.; Kadri, N.; Toubal, S.; Benhabyles, N.; Akmoussi-Toumi, S.; Khemili-Talbi, S. GC-MS analysis and in vitro study of antifungal, antiurease and anticholinesterase potentials of origanum compactum Benth. Essential oil. Nveo-Nat. Volat. Essent. Oils J. 2022, 9, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kerbab, K.; Sanah, I.; Djeghim, F.; Belattar, N.; Santoro, V.; D’Elia, M.; Rastrelli, L. Nutritional Composition, Physicochemical Properties, Antioxidant Activity, and Sensory Quality of Matricaria chamomilla-Enriched Wheat Bread. Foods 2025, 14, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical Cation Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laghezza Masci, V.; Mezzani, I.; Alicandri, E. ,, Tomassi, W.; Paolacci, A. R.; Covino, S.:... & Ovidi, E. The Role of Extracts of Edible Parts and Production Wastes of Globe Artichoke (Cynara cardunculus L. var. scolymus (L.)) in Counteracting Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Szydłowska-Czerniak, A.; Dianoczki, C.; Recseg, K.; Karlovits, G.; Szłyk, E. Determination of Antioxidant Capacities of Vegetable Oils by Ferric-Ion Spectrophotometric Methods. Talanta 2008, 76, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyürek, M.; Güngör, N.; Baki, S.; Güçlü, K.; Apak, R. Development of a Silver Nanoparticle-Based Method for the Antioxidant Capacity Measurement of Polyphenols. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 8052–8059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keawchaoon, L.; Yoksan, R. Preparation, Characterization and In Vitro Release Study of Carvacrol-Loaded Chitosan Nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2011, 84, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. , Xiao, H., Wu, Y., Zhou, F., Hua, C., Ba, L.,... & Zhang, W. Characterization of volatile compounds and microstructure in different tissues of ‘Eureka’ lemon (Citrus limon). International Journal of Food Properties 2022, 25, 404–421. [Google Scholar]

- Golmakani, M. T.; Moayyedi, M. Comparison of microwave-assisted hydrodistillation and solvent-less microwave extraction of essential oil from dry and fresh Citrus limon (Eureka variety) peel. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2016, 28, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petretto, G. L.; Vacca, G.; Addis, R.; Pintore, G.; Nieddu, M.; Piras, F. . & Rosa, A. Waste Citrus limon leaves as source of essential oil rich in limonene and citral: Chemical characterization, antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, and effects on cancer cell viability. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kačániová, M.; Čmiková, N.; Vukovic, N. L.; Verešová, A.; Bianchi, A.; Garzoli, S. . & Vukic, M. D. Citrus limon essential oil: chemical composition and Selected biological properties focusing on the antimicrobial (in vitro, in situ), Antibiofilm, Insecticidal activity and preservative effect against Salmonella enterica inoculated in carrot. Plants 2024, 13, 524. [Google Scholar]

- Viuda-Martos, M.; Ruiz-Navajas, Y.; Fernández-López, J.; & Pérez-Álvarez, J.; Pérez-Álvarez, J. Antifungal activity of lemon (Citrus lemon L.), mandarin (Citrus reticulata L.), grapefruit (Citrus paradisi L.) and orange (Citrus sinensis L.) essential oils. Food control 2008, 19, 1130–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kgang, I. E.; Klein, A. ,, Mohamed, G. G.,; Mathabe, P. M.; Belay, Z. A.; Caleb, O. J. Enzymatic and proteomic exploration into the inhibitory activities of lemongrass and lemon essential oils against Botrytis cinerea (causative pathogen of gray mold). Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 13, 1101539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Z.; Nie, D.; Tang, W. ; Li, YThe chemical composition and antibacterial and antioxidant activities of five citrus essential oils. Molecules 2022, 27, 7044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngo, T. C.; Dao, D. Q.; Thong, N. M.; & Nam, P. C.; Nam, P. C. Insight into the antioxidant properties of non-phenolic terpenoids contained in essential oils extracted from the buds of Cleistocalyx operculatus: a DFT study. RSC advances 2016, 6, 30824–30834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, R. F.; Balbinot Filho, C. A.; Borges, C. D. Essential oils as natural antimicrobials for application in edible coatings for minimally processed apple and melon: A review on antimicrobial activity and characteristics of food models. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2022, 31, 100781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, P. A. , Palade, L. M., Nicolae, I. C., Popa, E. E., Miteluț, A. C., Drăghici, M. C.,... & Popa, M. E. Chitosan-based edible coatings containing essential oils to preserve the shelf life and postharvest quality parameters of organic strawberries and apples during cold storage. Foods 2022, 11, 3317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ibáñez, M. D. , Sanchez-Ballester, N. M., Blázquez, M. A. Encapsulated limonene: A pleasant lemon-like aroma with promising application in the agri-food industry. A review. Molecules 2020, 25, 2598. [Google Scholar]

- Said, N. S. , Olawuyi, I. F., Lee, W. Y. Pectin hydrogels: Gel-forming behaviors, mechanisms, and food applications. Gels 2023, 9, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R. , Nath, P. C., Das, P., Rustagi, S., Sharma, M., Sridhar, N.,... & Sridhar, K. (). Essential oil-nanoemulsion based edible coating: Innovative sustainable preservation method for fresh/fresh-cut fruits and vegetables. Food Chemistry 2024, 460, 140545. [Google Scholar]

- Pradhan, B.K.; Dhal, S.; Pal, K. Essential oil-based antimicrobial food packaging systems. In Advances in Biopolymers for Food Science and Technology; Elsevier: 2024; pp. 391–417.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).