1. Introduction

1.1. What are High-Performance Tall Buildings?

High-performance tall buildings represent the pinnacle of contemporary skyscraper design, integrating cutting-edge technologies, sustainable practices, and advanced materials to achieve superior functionality, environmental responsibility, and occupant well-being. These buildings go beyond traditional definitions of sustainability by harmonizing aesthetic appeal, structural resilience, indoor air quality, and operational efficiency to deliver a comprehensive standard of "total building performance" (Schodek, 2016).

At their core, high-performance tall buildings prioritize energy efficiency, utilizing passive and active design strategies such as: natural ventilation, indoor air quality, daylight harvesting, and intelligent building management systems to minimize energy consumption. Renewable energy technologies, including solar panels, wind turbines, and geothermal systems, further reduce dependence on non-renewable resources, while advanced façade systems like double-skin curtain walls and energy-generating glass enhance thermal performance and mitigate environmental impact (Al-Kodmany, 2018).

Functionality is a hallmark of high-performance skyscrapers. These buildings are designed to optimize resource use, adapt to climatic conditions, and ensure occupant safety and comfort. Innovations such as structural systems tailored to withstand wind and seismic forces, high-strength materials, and advanced HVAC systems allow these structures to perform reliably under diverse conditions. Additionally, they foster healthier environments by integrating features like green roofs, indoor landscaping, and superior indoor air quality management.

High-performance tall buildings also set benchmarks for economic and social impact. Through efficient energy use, reduced operational costs, and long-term durability, they offer financial sustainability while creating livable urban spaces that enhance community engagement and productivity. Ultimately, these buildings exemplify the future of urban architecture, addressing the pressing challenges of climate change, urbanization, and resource conservation while contributing to a more sustainable and resilient built environment.

1.2. Objectives

This paper aims to explore and define the concept of high-performance tall buildings, a typology that has evolved since approximately 2006 to incorporate not just sustainability but also enhanced functionality and holistic performance. Early examples such as the Commerzbank Tower in Frankfurt of 1997, 4 Times Square in New York of 1999, and the Swiss Re Tower (Gherkin) in London of 2003 showcased a growing focus on sustainability in tall building design (Ali and Moon, 2007). Similarly, Ken Yeang’s climate- and vegetation-based ecological tall buildings introduced a unique approach to integrating nature into vertical structures (Yeang, 1996; 2022). These pioneering buildings signaled the transition toward a new generation of tall buildings that prioritize energy efficiency, resource conservation, and occupant well-being.

The Hearst Tower in New York of 2006 marked a turning point, elevating sustainability to new heights. Since then, tall buildings have matured into complex systems that integrate sustainability with innovative technologies, addressing additional realms such as energy management, structural efficiency, and occupant comfort. Notable examples like the Burj Khalifa in Dubai of 2010, the world’s tallest building at 828 meters (2,717 feet), and the Pearl River Tower in Guangzhou of 2013 illustrate the practical application of these principles, balancing functionality, aesthetic appeal, and advanced building systems.

This study emphasizes the need for a collaborative approach among architects, engineers, and specialists to design high-performance tall buildings that integrate intelligent systems and advanced technologies. While the literature provides insights into specific aspects of sustainability and performance-driven principles, a comprehensive resource addressing the multi-dimensional nature of high-performance skyscrapers remains scarce (Elotefy et al., 2015; Ali et al., 2023). Recent publications focus on topics of limited scope, but do not exclusively address the unique narratives of high-performance skyscrapers in a comprehensive way (Day and Gunderson, 2015; Lewis et al., 2022; Al-Kodmany et al., 2022; Abdelwahab et al., 2023; Lawrence and Keen, 2024). Bridging this gap is the primary objective of this paper, which aims to provide a unified framework that synthesizes advanced technologies, performance metrics, and sustainable practices for the next generation of tall buildings.

1.3. Methodology

This exploratory study aims to understand the relationship between tall buildings and their overall performance, focusing on the role of advanced technologies in enhancing energy efficiency and other functional features. To accomplish this, the research investigates recent prevalence of high-performance tall building typology. The study relies heavily on dispersed knowledge gathered from available pre-existing publications and alternative sources. Notably, information from architectural magazines, conference proceedings, and industry reports have been utilized due to the scarcity of peer-reviewed academic journal articles on this subject.

The authors undertook considerable effort to synthesize and summarize available critical information. The collected information was meticulously analyzed to identify recurring patterns, emerging trends, and underlying themes that inform the design and performance of tall buildings. To contextualize these findings, illustrative case studies of selected projects are developed, highlighting best practices, innovative technologies, and their real-world implications. To achieve this, the research systematically explores the multi-dimensional aspects of tall buildings, encompassing data-driven design, operation, functionality, and sustainability. This approach facilitated the derivation of meaningful and insightful conclusions.

2. Influence of the “Green Movement” on High-Performance Tall Buildings

The “green movement” began from the notion of sustainability. Sustainability or sustainable development originated from an international political process emphasizing the environment around the human habitat and its future (Newman, 2001). Sustainability was brought up internationally at the 1972 UN Conference on the Human Environment. The Arab oil embargo of 1973 precipitated the energy shortage crisis and acted as a stimulus to do something about energy conservation. In 1989 the World Commission on Environment and Development(WCED) established by UN published “Our Common Future” (WCED, 1989). This movement thus became a global response to pressing environmental issues and has profoundly influenced how we design and construct tall buildings.

Early skyscrapers were often symbols of resource-intensive urbanization, but today’s tall buildings strive to balance environmental responsibility with architectural ambition. The push for sustainable architecture has catalyzed a transformation in high-rise design, making sustainability a cornerstone rather than an afterthought. Global warming caused by carbon emissions resulting in the threat of climate change has added urgency about how tall buildings should be designed to be as sustainable as possible. An influential book by Al Gore in 2006 spurred the green movement further underscoring the importance of considering the crisis of global warming (Gore, 2006). In a detailed paper Antony Wood discussed the pros and cons of sustainable tall buildings and emphasized the environmental challenges that we face in our time (Wood, 2008).

Green building certifications like LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) and BREEAM (Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method) are pivotal in this shift. These certification frameworks provide clear guidelines prioritizing energy conservation, water efficiency, waste reduction, and indoor environmental quality, thereby incentivizing architects, developers, and investors to adopt greener practices. A LEED-certified building, for instance, is recognized for meeting specific sustainability criteria, enhancing its appeal to tenants and investors who value environmental stewardship.

The green movement has redefined skyscrapers as platforms for environmental innovation, pushing architects to balance aesthetics and sustainability in high-rise design. These buildings integrate energy-efficient technologies, sustainable materials, and green design strategies, proving that skyscrapers can transcend traditional roles to become symbols of ecological responsibility (Ali et al., 2023; Oldfield, 2019; Al-Kodmany, 2018).

2.1. Paradigm Shift Toward Performance

Lately, skyscraper design has evolved from focusing solely on aesthetics and style to prioritizing sustainability and functional performance. To mitigate environmental challenges due to climate change, contemporary high-rises reflect a performance-driven approach that prioritizes reducing carbon footprints, enhancing energy efficiency, and integrating seamlessly with thermal comfort and indoor air quality in urban settings. These modern skyscrapers are designed with cutting-edge technology and sustainable materials, aiming to minimize their environmental impact throughout their life cycle--from construction and operation to eventual deconstruction. By incorporating energy-efficient systems, renewable energy sources, and eco-friendly materials, high-performance skyscrapers foster healthier, more cities in balance that provide enduring benefits to their communities. This shift supports urban sustainability and long-term economic stability, transforming skyscrapers into valuable contributors to urban environments rather than mere symbols of architectural aspiration (Tormenta, 1999).

3. Fundamentals of High-Performance Skyscrapers

The fundamental elements of high-performance tall buildings depend upon state-of-the-art technologies, sustainable materials, integrated building systems, indoor air quality, and energy-efficient strategies. High-performance skyscrapers strive to effectively balance environmental, social, and economic impacts by harnessing these advancements. Cutting-edge technologies, such as intelligent building management systems (BMS), renewable energy integration, sensors, and advanced façade materials, help reduce operational emissions and enhance occupant well-being. Sustainable materials and building strategies, like green roofs and vegetative facades, mitigate urban heat and improve city air quality. Together, these elements form a model for sustainable urban growth, allowing tall buildings to adapt to the needs of dense urban settings while promoting resilience, environmental stewardship, and economic vitality in cities.

Advances in skyscraper technology and integration have progressed from stylistic benchmarks to performance-based criteria. With a focus on designing more energy-efficient, environmentally conscious and compliance with the needs of occupant comfort skyscrapers, designers have entered a new era of tall building design (Day and Gunderson, 2015). This requires more significant and more sophisticated methods of collaboration among professionals and integration of multifaceted and trendier building physical systems and technologies. Zero-energy buildings have been attempted that will theoretically decrease their carbon footprints to preferably almost zero by integrating renewable energy technologies, such as solar panels, wind turbines, and fuel cells, with innovative and “green” materials and environmentally efficient forms (Ali and Aksamija, 2007).

Architects and engineers had always envisaged articulated and non-traditional high-rise forms. Still, they were hindered by a lack of algorithms and analytical methods to calculate intricate variables imposed by natural forces of wind, earthquakes, and gravity. Finite Element Analysis (FEA) and Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), in conjunction with advances in parametric kits like Building Information Modeling (BIM), allow engineers to precisely compute externally applied loads and reactive internal forces and deformations across the building structure, shape towers into streamlined aerodynamic forms and create virtual models that simulate wind loads and environmental effects. These developments, together with advanced structural systems and composite materials, have opened up new and exciting design possibilities for well-fashioned skyscrapers, dynamic and rotating towers, as well as supertall and megatall buildings (Ali and Moon, 2018).

This paper identifies five key dimensions critical to the design and operation of high-performance high-rise buildings:

The subsequent sections provide an in-depth exploration of each dimension, highlighting their roles and interconnections in creating sustainable, efficient, and resilient tall buildings.

4. Structural Materials and Systems

Beyond ensuring the strength and stability of a structure, the choice of materials and construction techniques directly influences the building's environmental footprint and capacity to support innovative architectural forms. Sustainable structures prioritize both resilience and ecological responsibility, driving the modern design of high-performance tall buildings.

4.1. Structural Materials

The most widely used materials in high-rise construction have been steel and concrete. The high strength-to-weight ratio of steel allows for the creation of tall and slender forms, which minimizes the use of materials while maximizing the structure's efficiency. It is greatly recyclable, reducing waste and lowering the carbon footprint associated with material extraction and manufacturing. However, steel production is energy intensive. It has a high embodied energy. Recent advancements in manufacturing processes, such as electric arc furnaces and recycling practices, have helped mitigate some of these environmental concerns, making steel a more sustainable option for structural design.

Concrete is another dominant material in tall building construction, known for its versatility and durability. However, during the manufacture of cement, it releases carbon. Innovations such as high-performance concrete (HPC), which uses less cement, and the incorporation of supplementary cementitious materials like fly ash and slag help reduce the carbon intensity of concrete. Additionally, the development of carbon-sequestering concrete, which absorbs CO2 during its curing process, offers a potential solution to reduce the carbon footprint of tall buildings further.

Timber is emerging as a sustainable alternative in the design of tall buildings of moderate heights. Cross-laminated timber (CLT) and mass timber systems have been increasingly adopted in the construction of high-rise buildings in recent years due to their renewable nature and reduced embodied energy. Timber structures store carbon throughout their lifecycle, contributing to the overall reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in the built environment. Modern timber construction techniques have advanced significantly, offering strength and fire resistance and providing a warmer, more natural aesthetic (Cover, 2019).

Integrating composite (also called hybrid) structural systems, i.e., combining steel, concrete, and timber, offers further opportunities for sustainability. By leveraging the strengths of each material--such as the flexibility of steel, the mass, damping, and thermal properties of concrete, and the renewability of timber--designers can create more efficient and more environmentally responsible structures.

4.2. Structural Systems

Structural systems are fundamental in shaping the sustainability and performance of tall buildings. As tall buildings become taller, the material consumption increases exponentially, a concept known as “premium for height” that led to the development of height-based structural systems charts (Khan, 1969, 1972; Ali, 2001). This suggests that from a sustainability perspective, the structural system must be optimized to minimize material consumption. The choice of structural materials, organization, and member-sizing directly influence the outcome characteristics of high-performance tall buildings. In other words, tall buildings develop their strength and other structural and high-performance attributes by design.

Optimization of structural frame topology can be used to reduce material mass in building structures. Moreover, the choice of frame and floor slab materials can substantially impact the whole-life embodied carbon (WLEC) of structural frames and, therefore, the buildings themselves (Hart et al., 2021). While timber frames show much lower impacts in the product and construction stages, they can produce higher emissions at the end-of-life stage, which erodes their overall advantage without however coming close to eliminating it. However, there are still questions about how to compare the life cycle assessment of biogenic and non-biogenic materials. The difference in WLEC between the concrete and steel structures is insufficient to dictate the choice between them, and the focus should be on optimizing the design to meet relevant criteria (Hart et al., 2021).

4.2.1. Steel Structures:

Steel has long been the material of choice for tall buildings, primarily due to its exceptional strength-to-weight ratio and flexibility, making it ideal for the structural demands of high-rise buildings. Steel is also highly recyclable, making it an environmentally responsible choice for construction. According to industry estimates, about 85-90% of structural steel used in buildings is recycled, and the material itself can be continuously recycled without losing its strength or durability. This closed-loop recycling process significantly reduces the environmental impact associated with steel production. Furthermore, advances in steel manufacturing techniques, such as the use of electric arc furnaces (EAFs), have helped reduce the carbon footprint of steel. EAFs use electricity to melt scrap steel, lowering energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions compared to traditional blast furnace methods, which rely on fossil fuels like coal.

Despite its environmental benefits, steel production is still energy-intensive, contributing to high embodied carbon emissions associated with material extraction, manufacturing, and transportation. Lightweight structural systems designed to reduce the amount of steel and composite construction methods that combine steel with concrete with lower embodied carbon are increasingly being adopted. Also, steel’s flexibility plays a crucial role in the design of deformable high-rise buildings. It can bend without breaking, making it suitable for buildings in seismic zones.

4.2.2. Concrete Structures:

Reinforced concrete has become one of the most versatile and essential materials for constructing tall buildings due to its durability, fire resistance, damping properties, and moldability for complex architectural forms. A critical development in recent decades is the development of High-Performance Concrete (HPC), specifically designed to improve traditional concrete's structural performance while minimizing material consumption. This results in a more efficient design that enhances durability, lowers embodied carbon, and makes HPC cost-effective and environmentally friendly.

In addition, concrete's thermal mass property plays a crucial role in enhancing a building’s energy efficiency and improving thermal comfort (Ghoreishi and Ali, 2011). Concrete’s ability to absorb and store heat helps to moderate indoor temperatures, reducing the demand for heating and cooling systems. This results in improved energy performance, essential for high-performance tall buildings that meet sustainability targets such as LEED certification or other environmental benchmarks. In sum, reinforced concrete, especially in its high-performance forms, continues to be an indispensable and popular material in the construction of tall buildings. Its strength, adaptability, durability, fire resistance, and energy efficiency allow.

4.2.3. Timber Structures:

Timber, once confined to low-rise buildings due to concerns about fire safety and structural limitations, is now experiencing a renaissance in high-rise construction due to advancements in engineered wood products like cross-laminated timber (CLT) and glue-laminated timber (Glulam). These innovations have fundamentally transformed the role of wood in the construction of mid- and high-rise buildings. The increasing use of wood in tall structures responds to the growing demand for carbon-neutral construction and the need to mitigate the environmental impact of traditional building materials.

One of the primary advantages of timber is its status as a renewable resource, provided it is sourced from sustainably managed forests. Timber has a significantly lower embodied carbon than steel and concrete, which involve energy-intensive production processes. Manufacturing engineered timber products, particularly CLT, utilizes small, fast-growing trees, maximizing material use and sustainability efficiency. Also, timber sequesters carbon, storing it within the building’s structure throughout its lifecycle, further contributing to its environmental benefits.

Concerns about fire safety have traditionally been a significant barrier to using timber in tall buildings. However, modern engineered timber products have been shown to perform well under fire conditions. This fire-resistant property of engineered wood has been rigorously tested and meets international safety standards for tall buildings.

In addition to its sustainability and fire-resistance benefits, timber offers aesthetic and biophilic advantages. Its natural appearance and warmth bring an organic, human-centered feel to modern architecture, which contributes to the well-being of occupants. The biophilic design philosophy--connecting people with nature--has been increasingly embraced in urban environments, and timber’s natural qualities align well with this trend.

Timber's growing popularity in high-rise construction is exemplified by several pioneering projects worldwide. Buildings like the Mjøstårnet in Norway are currently the world’s tallest timber building at 18 stories.

5. Energy-Efficient Design

As cities expand vertically and become increasingly dense, the vertical density increases, which reduces horizontal urban sprawl, and energy-efficient tall buildings become essential to sustainable urban development. High-rise structures typically require substantial energy for daily operations and are now embracing innovative strategies to minimize energy consumption, enhance comfort, and reduce environmental impact. High-performance buildings can significantly lower their carbon footprint and operational costs by blending passive and active design approaches, integrating renewable energy, and maximizing operational efficiency.

5.1. Passive Design Approaches

Passive design is a cornerstone of energy-efficient architecture, leveraging natural forces such as sunlight, wind, and thermal mass of concrete buildings to regulate building temperature with minimal energy input. Orienting a building to optimize solar gain during the winter while limiting it in the summer reduces demand for heating and cooling systems. High-performance glazing and advanced insulation further enhance energy efficiency by minimizing heat transfer. Integrating shading devices like louvers or vertical fins in warm climates reduces solar radiation on façades, lessening the need for air conditioning. These design strategies, which rely on natural environmental interaction rather than artificial intervention, can considerably lower a building's energy use (Castro-Alvarez et al., 2018).

5.2. Intelligent Systems to Save Energy

Innovative technology adds another dimension to energy-efficient design by using real-time data to manage a building’s energy consumption. Intelligent thermostats, sensors, and automated systems can detect occupancy, adjusting HVAC, lighting, and water systems accordingly. For instance, smart thermostats modulate temperatures based on occupancy patterns and weather conditions, while motion-sensor lights reduce electricity usage in unoccupied spaces. The transition to LED lighting has further optimized energy use, as LEDs are more energy-efficient, durable, and low-maintenance than traditional lighting, reducing overall operational costs (Kwok & Grondzik, 2018).

5.3. Renewable Energy Integration

On-site renewable energy generation has become a key feature of high-performance tall buildings, helping reduce reliance on non-renewable sources such as fossil fuels. Solar energy is a leading choice; PV panels or building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV) can be installed on rooftops or façades to harness sunlight and produce clean energy. These advanced PV systems blend with architectural design, turning façades into functional and aesthetic energy generators.

Additionally, some skyscrapers incorporate wind turbines, particularly in areas with consistent, high-altitude winds. For example, the Bahrain World Trade Center uses wind turbines between its twin towers to generate renewable energy, showcasing how even populated urban environments can support renewable energy production. Geothermal systems, which use the Earth’s stable underground temperature for heating and cooling, are also gaining traction in energy-efficient design. These systems are particularly effective in climates with extreme seasonal variations, providing a continuous and renewable energy source for climate control (Castr et al., 2018).

5.4. Energy Recovery Systems

Many high-performance buildings integrate energy recovery systems to maximize efficiency, capturing and reusing waste energy. For instance, heat recovery ventilation (HRV) systems transfer heat from exhaust air to incoming fresh air, reducing the load on heating and cooling systems. Heat exchangers, another energy recovery technology, can repurpose waste heat from HVAC and water systems, minimizing energy loss and enhancing overall building efficiency.

5.5. Green Roofs and Vertical Gardens

Green roofs and vertical gardens add aesthetic value and enhance energy efficiency by enhancing insulation. These features help maintain stable indoor temperatures by absorbing heat during the day and releasing it at night, reducing the need for mechanical heating and cooling. They also mitigate the urban heat island effect, improve stormwater management, and contribute to a building's energy performance by adding a natural, insulating layer to its structure (Yeang, 1999).

5.6. Balancing Non-renewable and Renewable Energy

High-performance buildings aim to reduce dependence on non-renewable energy sources while integrating renewable solutions for a sustainable future.

5.6.1. Reducing Non-renewable Energy Use:

Non-renewable energy sources, such as coal and natural gas, have historically powered tall buildings, but their use contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. Energy-efficient buildings mitigate this impact by combining advanced management systems with passive design strategies, which lower the demand for non-renewable energy by reducing the need for heating, cooling, and lighting.

5.6.2. Maximizing Renewable Energy:

Renewable energy systems, especially solar panels on façades and rooftops, have become common in modern tall buildings. BIPVs allow buildings to generate energy while maintaining architectural coherence. Though less common, wind turbines provide a viable energy source in specific environments, like the high-altitude wind corridors utilized by the Bahrain World Trade Center. Geothermal systems also offer a stable and renewable heating and cooling source, particularly valuable in regions with extreme climate shifts (Kwok & Grondzik, 2018).

6. High-Performance Facades

The façade of a tall building plays a fundamental role in shaping its energy efficiency, environmental impact, and occupant comfort. As the outermost layer, the façade serves as the first line of defense against weather conditions, thermal fluctuations, and external noise. A high-performance façade not only contributes to the aesthetic appeal of the building but also plays a pivotal role in optimizing thermal performance, maximizing natural daylight, improving ventilation, and integrating renewable energy technologies. Through innovations such as double-skin façade (DSF), dynamic shading systems, and energy-generating glass, modern façades have become vital to high-rise buildings' sustainability and operational efficiency (Castro-Alvarez et al., 2018).

6.1. Double-Skin Façades

One of the most prominent innovations in high-performance façades is the Double-Skin Façade (DSF). A DSF is an architectural and engineering system consisting of two layers of façades (an inner and an outer layer) separated by a ventilated cavity. This cavity can act as a buffer zone between the indoor environment and the outdoor weather, improving insulation and helping to regulate internal temperatures. In winter, the air trapped between the two skins can act as an insulating layer, reducing the need for heating. In summer, controlled ventilation within the cavity can help dissipate heat, reducing the cooling load. DSFs are often used in modern architecture to balance aesthetics, functionality, and sustainability.

DSFs are especially effective in temperate climates where external temperatures fluctuate significantly between day and night or across seasons. Their passive heating and cooling capabilities reduce the reliance on mechanical HVAC systems, improving energy efficiency. For example, One Angel Square in Manchester employs a double-skin façade that enhances its thermal performance and allows the building to achieve a high level of environmental sustainability, contributing to its BREEAM "Outstanding" rating.

Additionally, DSFs can improve acoustic insulation, making them an attractive choice for buildings in dense urban environments or near major transportation routes. By buffering external noise, these façades can create a more comfortable indoor environment for occupants. Also, human comfort is ensured by de-coupling the ventilation system with a raised access floor and a chilled radiant ceiling system.

The Pearl River Tower of 2013 in Guangzhou, China, designed by Adrian Smith and SOM, is an example of a high-performance tower with wind turbines and solar collectors, PV cells, raised floor ventilation, and radiant heating and cooling ceilings. It employs a computer-generated aerodynamic form to direct air into sizeable horizontal wind turbines located on mechanical floors to generate the building’s energy. Additional features include Low-E glass, a DSF that acts as a thermal envelope, and recyclable and green materials. Compliance with LEED standards allows designers and clients to target building performance to market forces. It also provides an empirical system of measurement to evaluate tall buildings' performance from concept to life-cycle stages.

6.2. Dynamic Shading Systems

High-performance façades often incorporate dynamic shading systems that adjust to changing environmental conditions in real time. These systems include automated louvers, blinds, or other movable elements that respond to sunlight, temperature, and wind conditions, optimizing daylight penetration and thermal regulation.

Dynamic shading systems offer multiple benefits, such as reducing solar heat gain during hot summer months while allowing natural light to permeate the building and reducing the need for artificial lighting. In winter, the shading systems can retract, enabling more sunlight to enter and reduce the need for heating. The Al Bahr Towers in Abu Dhabi is a notable example of a building utilizing dynamic shading. Its responsive façade system, inspired by traditional Islamic "mashrabiya" designs, automatically opens and closes depending on the intensity of sunlight, significantly reducing energy consumption for cooling.

Photochromic or electrochromic glass further enhances the adaptability of dynamic façades. These materials can automatically adjust their opacity based on light exposure, offering an advanced solution for controlling solar radiation. Electrochromic glass, for instance, can darken in response to bright sunlight, reducing glare and heat, and then return to a transparent state when sunlight levels are lower, maintaining indoor visual comfort and reducing cooling demands.

6.3. Energy-Generating Façades

The façade of a tall building is not only a passive element that shields the interior from external environmental interferences but also a platform for generating energy. PV panels integrated into façades can produce renewable energy directly from the sun, transforming vertical surfaces into energy-generating assets. These energy-generating façades are becoming increasingly common in high-performance buildings as part of the broader push toward net-zero energy consumption (Bachman, 2003).

BIPV involves the seamless integration of solar panels into the building’s skin, allowing the façade to generate clean energy while maintaining its aesthetic qualities. Light harvesting is a much better option, so developing interior light shelves is a way to move light in. Nanotechnology is used to create thin films that provide filters for energy transfer through glass. It is possible to explore if the same kinds of technology to redirect light can be used so that as sunlight comes through a window, it streams in and instantly goes to the floor, where it turns into heat.

The Edge in Amsterdam, considered one of the most sustainable office buildings in the world, features a façade outfitted with PV panels, allowing it to generate a significant portion of its energy needs on-site. This reduces the building’s reliance on external energy sources and lowers its carbon footprint.

Beyond traditional PV panels, transparent solar glass technology advancements have expanded the possibilities for energy-generating façades. This type of glass allows sunlight to pass through while converting a portion of it into electricity. Such innovation can enable entire building envelopes to serve as energy-generating surfaces without compromising natural light or transparency, further enhancing the sustainability profile of the building (Castr et al., 2018).

6.4. High-Performance Materials

At the heart of high-performance façades are the advanced materials used in their construction. These materials are engineered to deliver superior insulation, durability, and energy efficiency. High-performance glazing systems, for example, often feature low-emissivity (low-E) coatings, which reduce heat transfer through windows without reducing natural light. Low-E glass is particularly effective in maintaining indoor temperature stability, reflecting infrared radiation while allowing visible light to pass through.

Insulated glass units (IGUs), which consist of two or more layers of glass separated by air-filled spaces, are also critical to improving thermal performance. These units can significantly reduce windows' U-value (i.e., a measure of heat transfer), minimizing heat loss in winter and heat gain in summer. Argon-filled IGUs offer even greater thermal insulation, as the gas between the glass layers slows heat transfer more effectively than air.

Recycled and eco-friendly materials are increasingly used to construct high-performance façades, reducing embodied carbon and contributing to the building’s overall sustainability. Using materials such as recycled aluminum and low-carbon concrete in façade systems helps reduce the overall environmental impact of construction while maintaining high performance (El-Wassimy, 2011).

6.5. Natural Ventilation and Breathability

High-performance façades are designed to enhance occupant comfort by improving indoor air quality and allowing for natural ventilation. Breathable façades, which integrate operable windows or air-permeable materials, enable natural airflow through the building. This can significantly reduce the need for mechanical ventilation, especially in moderate climates.

By allowing fresh air to enter the building, breathable façades improve indoor air quality and reduce the concentration of pollutants, leading to better health outcomes for occupants. Moreover, natural ventilation can provide passive cooling during certain times of the year, reducing energy consumption for air conditioning. For instance, the Torre Reforma in Mexico City features a façade system allowing controlled natural ventilation, enhancing energy efficiency and occupant well-being.

Integrating natural ventilation systems is particularly effective when combined with atrium spaces or ventilation shafts, which can facilitate airflow through the building in a controlled manner. This design strategy, known as stack ventilation, relies on differences in air pressure to draw fresh air into the building and expel stale air, contributing to energy savings and improved indoor comfort (Iqbal, 2022).

6.6. Thermal Performance and Energy Savings

The primary function of high-performance façades is to enhance the building’s thermal performance, reducing the need for active heating and cooling systems. By incorporating advanced insulation materials and technologies, these façades minimize heat transfer between the interior and exterior environments, helping to maintain stable indoor temperatures year-round.

Thermally efficient façades can significantly reduce the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) loads of a building. In cold climates, a high-performance façade can minimize heat loss, reducing the need for space heating. It can prevent excessive heat gain in hot climates, lowering the demand for air conditioning. As a result, buildings with high-performance façades tend to have lower operational costs and reduced environmental impact.

Thermal bridging, which occurs when heat bypasses the insulation layer and passes through more conductive materials like metal, is a common issue in poorly designed façades. High-performance façades are designed to minimize thermal bridging by incorporating thermal breaks and non-conductive materials, such as fiber-reinforced polymers or thermally insulating spacers. These design elements prevent heat from leaking through the façade and contribute to the overall thermal efficiency of the building.

High-performance façades are a critical component of high-performance tall buildings, integrating advanced materials, innovative technologies, and intelligent design strategies to enhance energy efficiency, occupant comfort, and environmental performance. Using DSFs, dynamic shading systems, energy-generating glass, and natural ventilation systems, these façades help reduce energy consumption and lower the building’s carbon footprint. Additionally, using high-performance materials and design techniques, such as low-E glass and insulated glazing units, ensures optimal thermal performance, improving the building’s overall sustainability. As the demand for environmentally friendly and energy-efficient skyscrapers continues to grow, high-performance façades will play an increasingly important role in shaping the future of tall building design (Kwok & Grondzik, 2018).

7. Monitoring of Performance

Continuous monitoring is essential to ensure that high-performance tall buildings function at their peak efficiency and deliver on their sustainability promises. As these buildings are designed to minimize energy use, enhance occupant comfort, and ensure long-term structural integrity, the ability to track their performance in real time becomes increasingly critical. Monitoring enables building managers to verify that systems are working as intended and anticipate potential issues before they escalate. Modern technology offers powerful tools such as BIM, intelligent sensors, and automated control systems, which provide real-time data to optimize building performance. This section will explore the importance of performance monitoring, the technologies used, and how they contribute to high-rise buildings' operational efficiency and sustainability (Kwok & Grondzik, 2018).

7.1. Importance of Continuous Monitoring

High-performance buildings are complex ecosystems integrating various systems, including heating, ventilation, air conditioning (HVAC), lighting, water use, and renewable energy generation. These systems are designed to work harmoniously, minimizing resource consumption while maintaining a comfortable and productive environment for occupants. However, continuous performance monitoring is necessary to ensure these goals are met.

Monitoring enables building managers to track energy consumption, indoor air quality, temperature control, and structural health, among other factors. The insights from this data allow for real-time adjustments, ensuring that the building operates as efficiently as possible. Continuous monitoring can also identify underperforming systems or components, enabling proactive maintenance before issues escalate, which reduces downtime and extends the building's lifespan.

Moreover, monitoring systems can help ensure the building complies with local regulations and green building standards, such as LEED, BREEAM, or WELL certifications. These certifications often require regular performance assessments, making monitoring essential to maintaining a building’s certification status.

7.2. Use of BIM for Monitoring

BIM is a revolutionary tool in architecture and construction that integrates multiple aspects of a building's design and operation into a digital model. Traditionally, BIM has been used primarily during the design and construction phases. However, it is increasingly used in the operational phase to monitor building performance and maintain high-efficiency standards.

BIM allows for the creation of a 3D digital twin of the building, integrating structural, mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems into one comprehensive model. Once construction is complete, the digital twin becomes a dynamic tool that can be used to monitor real-time performance. Through BIM, building operators can track energy use, HVAC performance, lighting efficiency, and even the wear and tear on building components, allowing for predictive maintenance.

For example, in a high-rise building equipped with a BIM system, sensors embedded throughout the structure can feed real-time data into the model. If an HVAC unit begins to underperform, BIM software can highlight the issue, alerting the building manager to take corrective action before the problem affects occupant comfort or leads to higher energy costs.

BIM can also facilitate scenario planning. If a building operator wants to implement an energy-saving measure, BIM can simulate the impact of the change on overall building performance before it is applied. This helps avoid costly mistakes and ensures adjustments positively affect the building's efficiency.

7.3. Smart Sensors and IoT Integration

The Internet of Things (IoT) has revolutionized monitoring and controlling buildings. Smart sensors are a vital component of IoT, enabling real-time monitoring of virtually every aspect of building performance. When integrated with a building's management system, these sensors can continuously measure temperature, humidity, lighting levels, air quality, and occupancy.

Intelligent HVAC systems, for example, rely on a network of sensors to monitor and adjust heating and cooling outputs in real-time based on occupancy levels and external weather conditions. If fewer people are in a given area, the system can automatically reduce energy consumption by lowering the cooling or heating intensity. This not only optimizes energy use but also improves indoor comfort for occupants. Sensors can also monitor indoor air quality, detect carbon dioxide (CO2), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and other pollutants and adjust ventilation rates accordingly.

Intelligent lighting systems, equipped with sensors, can adjust based on natural light availability, ensuring that artificial lighting is used efficiently. Additionally, these systems can detect occupancy in a room, turning off lights when spaces are unoccupied, further reducing energy waste. In tall buildings, elevators are also a significant energy consumer. Intelligent sensors can optimize elevator use by predicting traffic patterns and adjusting operations to reduce energy use while minimizing wait times for occupants.

Integrating intelligent technologies with predictive analytics allows building operators to foresee when a system will likely need maintenance or replacement. This predictive maintenance capability helps avoid unexpected system failures, ensuring smooth operations and prolonging the life of crucial building components.

7.4. Monitoring Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Systems

Energy efficiency is a hallmark of high-performance buildings, and continuous monitoring is essential for ensuring that energy-saving measures are functioning as intended. Buildings often use energy management systems (EMS) to track real-time energy consumption. EMS can provide detailed insights into where energy is consumed, which systems are underperforming, and where adjustments can be made to improve efficiency.

In tall buildings, the HVAC system is typically the largest consumer of energy, followed by lighting and water heating. An EMS allows building managers to fine-tune these systems to optimize performance. For example, if the EMS detects that particular floors consume more energy than others, adjustments can be made to equalize energy distribution or address specific inefficiencies.

Monitoring is essential for buildings incorporating on-site renewable energy, such as solar panels or wind turbines. Real-time tracking ensures that these systems operate at maximum efficiency and helps identify any issues, such as shading on solar panels or mechanical problems with turbines, that could reduce output. Monitoring renewable energy systems also provides valuable data for calculating the building’s overall carbon footprint and meeting sustainability goals.

Energy storage systems, such as battery arrays, can also be integrated into the building’s monitoring framework. These systems store excess energy generated by renewable sources for use during periods of high demand or low renewable energy generation. Monitoring ensures that energy storage systems are used effectively, reducing reliance on the grid and enhancing the building’s resilience to power outages.

7.5. Indoor Environmental Quality Monitoring

A key aspect of building performance monitoring is maintaining a high level of indoor environmental quality (IEQ), which includes factors such as air quality, temperature, humidity, and lighting. Poor IEQ can lead to occupant discomfort, reduced productivity, and even health problems, making it a crucial aspect of building performance.

Continuous air quality monitoring ensures that pollutants such as CO2, particulate matter (PM2.5), and VOCs are kept within safe levels. In high-performance buildings, sensors continuously measure these parameters and adjust ventilation systems to introduce fresh air as needed. Monitoring systems can also detect changes in temperature and humidity, adjusting the HVAC system to maintain optimal indoor conditions.

The growing emphasis on health and wellness in building design, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, has highlighted the importance of maintaining clean air and optimal environmental conditions. Some advanced monitoring systems also track pathogen levels and use ultraviolet (UV) or HEPA filtration systems to purify the air, ensuring the indoor environment remains healthy and safe for occupants.

In addition to improving air quality, monitoring systems can enhance thermal comfort by continuously adjusting temperatures based on real-time occupancy and external weather conditions. This is particularly important in high-rise buildings, where varying solar exposure on different sides of the building can lead to temperature imbalances.

7.6. Structural Health Monitoring

Monitoring is not limited to energy systems and indoor environmental quality; it also extends to the structural health of tall buildings. Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) systems track the condition of a building’s load-bearing components, such as beams, columns, and foundations, in real-time. These systems use a combination of strain gauges, accelerometers, and vibration sensors to detect potential issues such as cracking, settling, or deformation.

In the case of tall buildings, which are subjected to significant gravity, wind, and seismic loads, SHM systems are essential for ensuring the safety and longevity of the structure. For example, in regions prone to earthquakes, sensors can detect even minor shifts in the building’s foundation or frame, allowing engineers to address potential problems before they become disastrous.

Wind-induced vibrations are another concern in tall buildings. Monitoring systems can track the building’s response to wind loads, helping to determine if additional damping systems or other structural reinforcements are necessary. Continuous monitoring ensures the building remains stable and safe, even under extreme environmental conditions.

7.7. Data-Driven Decision-Making and Role of AI

The real-time data collected through monitoring systems is pivotal in making well-informed, data-driven decisions that enhance building operations. This data helps facility managers optimize various aspects of a building's performance, such as reducing energy consumption, maintaining occupant comfort, and ensuring the structural integrity of high-performance buildings. The ability to continuously monitor these factors allows immediate intervention when inefficiencies or risks arise, preventing minor issues from escalating into costly repairs or hazardous conditions (Pennetti and Porter, 2024).

As building systems become more integrated with cutting-edge technologies like artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), the future of building monitoring is heading toward a new era of automation. AI-powered algorithms can analyze massive amounts of historical and real-time data, identifying patterns that human operators might overlook. These advanced systems can predict potential equipment failures, recommend preventive maintenance schedules, and even optimize energy use in real time by learning from past performance.

For example, by analyzing data from previous seasons, AI could predict how HVAC systems should be tuned to various weather conditions to minimize energy consumption while maintaining occupant comfort. Furthermore, AI can automatically adjust to real-time sensor feedback without human intervention. This increases operational efficiency and reduces the risk of human error.

Another major trend envisioned in building management is the integration of buildings into larger innovative city ecosystems. In an intelligent city framework, buildings will no longer operate in isolation. Instead, they will share data with other infrastructure elements, such as transportation and utility systems, to optimize resource usage across a city. For example, an intelligent building could communicate with the local power grid to shift energy consumption to off-peak hours, reducing demand during high electricity usage. This data-sharing capability enhances building performance and contributes to sustainability and energy efficiency in urban environments (Simmonds and Zhu, 2013).

In addition, as mentioned earlier, the development of "digital twins"--virtual models of buildings continuously updated with real-time data from their physical counterparts--will allow architects, engineers, and facility managers to simulate various scenarios and make informed decisions before they are implemented in the real world. This could further assist decision-makers in assessing the long-term impact of building modifications or policy changes before committing to them.

Ultimately, data-driven decision-making, powered by AI and allied technologies, will lead to more efficient, high-performance buildings. These advancements will benefit individual buildings and play a crucial role in shaping the future cities.

8. Integration of Building Services Systems

A genuinely high-performance tall building depends on seamlessly integrating various building services systems. These systems, including mechanical, electrical, and plumbing (MEP) and renewable energy technologies, must work harmoniously to maximize the building’s overall performance. The challenge of integration in high-rise structures is magnified due to the complexity of their systems and the growing emphasis on sustainability and energy efficiency.

8.1. Role of Systems Integration

The integration of different building service systems is essential for achieving the goal of a high-performance tall building. All MEP systems must work together, ensuring optimal energy use and the efficient delivery of services to all parts of the building. Tall buildings often feature vast and intricate networks of systems distributed over many floors, which makes their coordination both a technical and logistical challenge. Integrating systems, especially with intelligent controls and automation, enhances the building’s functionality by providing precise control over environmental conditions and energy use. Modern-day tall buildings exploit many intelligent, refined, and state-of-the-art building systems and technologies, including high-performance facades that regulate daylight and ventilation and high-efficiency HVAC systems offering indoor thermal comfort in conjunction with renewable energy systems. All these systems form a web of building systems integration (Ali and Armstrong, 2012).

High-performance tall buildings designed, among other things, to maximize energy efficiency depend on integrated systems that allow real-time responses to changing internal and external conditions. For example, HVAC systems defining the primary mechanical system in high-performance buildings are increasingly linked to advanced energy management systems (EMS). These EMS platforms utilize sensors and predictive algorithms to adjust heating, cooling, and ventilation based on occupancy levels, time of day, and weather conditions. Automated systems can respond to peak energy demands by reducing load during specific periods, thus contributing to the building’s overall sustainability and energy efficiency (Bachman, 2003).

8.1.1. HVAC Systems:

One of the most critical components of building services in tall buildings is the HVAC system, which ensures a comfortable indoor climate for occupants while consuming a significant portion of the building’s energy. In high-performance tall buildings, HVAC systems must be optimized to deliver comfort without wasting energy. This is typically achieved through advanced integration with other systems, such as BMS or EMS, allowing for intelligent control over temperature, humidity, and air quality.

Integration becomes even more critical in tall buildings, where HVAC systems must serve hundreds or thousands of occupants across dozens of floors. High-efficiency chillers, variable air volume (VAV) systems, and energy recovery ventilators (ERVs) are a few examples of HVAC technologies that reduce energy consumption when integrated adequately with automated controls while maintaining indoor comfort. The real-time monitoring of occupancy levels, CO2 concentrations, and temperature allows for more efficient operation by adjusting ventilation and cooling outputs based on actual demand.

District energy systems (DES) in dense urban areas are another innovative integration strategy for tall buildings. A DES connects multiple buildings to a centralized energy source, providing more efficient heating and cooling. By integrating with district energy networks, tall buildings can tap into shared energy resources, reducing their reliance on individual systems and benefiting from economies of scale.

8.1.2. Electrical Systems:

Integrating electrical systems in high-performance tall buildings is vital for optimizing energy use and managing the power needs of a large, complex structure. Electrical systems in tall buildings include lighting, power distribution, emergency systems, and renewable energy generation. As high-performance buildings aim to reduce their environmental footprint, integrating traditional electrical systems with renewable energy sources, such as solar panels, wind turbines, or geothermal systems, has become a key trend.

Advanced electrical systems integration also involves intelligent lighting controls, such as daylight sensors and occupancy-based lighting adjustments. Intelligent lighting systems adjust artificial lighting levels based on the availability of natural light, reducing energy consumption while ensuring that selected spaces remain well-lit. In some high-performance buildings, lights are programmed to dim or turn off automatically when rooms are unoccupied, further enhancing energy efficiency (Bachman, 2003).

A high-performance tall building’s electrical system often incorporates energy storage solutions such as batteries or flywheels, allowing the building to store excess energy generated during off-peak hours for later use. This helps balance energy consumption and mitigate peak demand charges from the utility grid. The increasing use of microgrids in tall buildings is also a growing trend. Microgrids provide localized energy generation and storage, enhancing the building’s resilience in the event of grid outages while offering better control over energy use.

8.1.3. Plumbing and Water Systems:

Plumbing systems in high-performance tall buildings must be designed to manage water usage efficiently, reduce waste, and promote sustainability. Integrating water systems often includes using graywater recycling systems, rainwater harvesting, and low-flow fixtures to minimize water consumption. For example, integrated plumbing systems may capture and treat graywater from sinks and showers for reuse in irrigation or toilet flushing, reducing the building's overall water demand.

Water-efficient systems are often connected to centralized BMS platforms, allowing facility managers to track and optimize water usage in real-time. This data-driven approach enables predictive maintenance, early leak detection, and better resource allocation, ensuring the building’s water systems operate efficiently.

Another aspect of water system integration in tall buildings is the implementation of smart meters and sensors. These devices allow for precise monitoring of water usage throughout the building and can detect leaks or inefficiencies early, reducing water waste and operational costs. In addition, some high-performance buildings are designed with on-site wastewater treatment systems, allowing for complete water cycle management within the building.

8.1.4. Renewable Energy Systems:

The drive for sustainability in high-performance tall buildings has increased focus on integrating renewable energy systems into the building design. As mentioned earlier, solar PV panels, wind turbines, and geothermal energy systems are becoming more common in tall buildings as part of the designer’s efforts to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and minimize carbon emissions. However, integrating renewable energy sources in a tall building presents unique challenges, particularly in urban settings where space is limited and shading from surrounding structures may reduce energy generation efficiency.

Integrating renewable energy systems often requires intelligent grid technology to manage the fluctuating energy supply from renewable sources and balance it with the building’s demand. These systems are connected to the building’s energy management platform, ensuring that the building can use renewable energy efficiently while storing excess energy for later use. Some buildings also incorporate energy-sharing systems, where excess energy generated by one building is shared with nearby structures through a localized energy network or microgrid.

8.1.5. Automation and Smart Building:

Automation is at the heart of systems integration in high-performance tall buildings. Automated control systems, enabled by the Internet of Things (IoT), intelligent sensors, and AI, allow continuous monitoring and optimization of all building systems. In an intelligent building, HVAC, lighting, water, and energy systems can communicate with each other to dynamically adjust their operations based on real-time data.

For example, an intelligent building management system can monitor occupancy levels, outdoor weather conditions, and energy prices to adjust HVAC settings, lighting levels, and energy use, optimizing for comfort and cost efficiency. This kind of automation reduces the need for manual intervention, improving overall operational efficiency and reducing energy waste.

Advanced BMS platforms integrate data from multiple systems into a centralized dashboard, providing building operators real-time insights into the building’s performance. AI algorithms can analyze this data to detect inefficiencies, predict maintenance needs, and adjust system settings for optimal performance. Generative AI is a powerful tool, but it will likely grow as it lacks emotion and cannot replace an engineer’s intuition, creativity, and critical and ethical thinking (Al-Kodmany et al, 2022).

Integrating building services systems is a cornerstone of achieving sustainability, energy efficiency, and occupant comfort in high-performance tall buildings. By seamlessly coordinating HVAC, electrical, plumbing, and renewable energy systems, these buildings can operate efficiently and adapt to changing conditions in real-time. The growing role of automation, AI, and intelligent technologies further enhances the ability of these buildings to optimize performance, minimize resource consumption, and ensure long-term resilience. Through intelligent systems integration, high-performance tall buildings are setting new standards for efficiency and sustainability in urban environments, driving the future of sustainable architecture.

An automated and integrated tall building development and operating system is within our reach. Problems of communication and coordination that in the past have beleaguered the manual process of designing tall buildings can be minimized in the future through automated systems that are integrated across the disciplines. The automated and integrated systems approach will improve design efficiency and reduce the cost of operating tall buildings.

9. Case Studies

The following section summarizes selected case studies of several high-performance tall buildings worldwide. It breaks down some of the varied features of cutting-edge technologies, advanced materials, and integrated systems addressing vertical architecture's unique challenges while promoting environmental stewardship and occupant well-being. Each example highlights the creative solutions and engineering breakthroughs that enable these skyscrapers to achieve optimal energy efficiency, structural safety, and other functionalities. Each case study is summarized by a table that captures all the key aspects for easy reference and placed in categories that align with the five dimensions detailed in the aforementioned sections. The case studies are organized chronologically to trace the evolution of high-performance tall buildings.

9.1. The Hearst Tower, New York City, 2006

The Hearst Tower in New York City, completed in 2006, exemplifies a harmonious blend of historic preservation, architectural innovation, and sustainability. Designed by renowned architect Norman Foster, the 46-story commercial skyscraper rises nearly 182 meters (600 feet) above a preserved six-story Art Deco base, originally designed by Joseph Urban in 1928 and recognized as a New York City Landmark. The tower’s distinctive diagrid structure enhances its modern aesthetic and reduces steel usage by 20%, providing a framework for unobstructed views and structural efficiency. As the first building in New York City to achieve Gold and Platinum LEED certifications, the Hearst Tower integrates cutting-edge eco-friendly features, including rainwater harvesting, energy-efficient lighting, and over 90% recycled steel in its construction. Beyond its environmental achievements, the tower is a cultural and functional hub, housing Hearst’s media and communication brands, public-facing art exhibitions, and state-of-the-art facilities. A model for adaptive reuse and sustainability, the Hearst Tower solidifies its legacy as a modern icon, seamlessly integrating a historic base with forward-thinking design and technology (Edwards, 2013). The following table highlights the prime features of the tower.

Figure 1.

Hearts Tower, New York. (Source: Authors).

Figure 1.

Hearts Tower, New York. (Source: Authors).

Table 1.

Hearst Tower, New York, 2006.

Table 1.

Hearst Tower, New York, 2006.

| Dimension |

Features |

| Structural Materials and Systems |

- Diagrid Structure: Diamond-pattern steel framework reducing steel usage by 20%, providing unobstructed interior views. |

| |

- Historic Base: Preserves the six-story Art Deco base designed by Joseph Urban (1928), integrating it into the modern tower. |

| |

- Over 90% recycled steel used in construction. |

| Energy-Efficient Design |

- LEED Certification: First NYC building to achieve Gold and Platinum certifications for core, shell, and interiors. |

| |

- Eco-Friendly Features: |

| |

- Natural ventilation and rainwater harvesting systems. |

| |

- Energy-efficient lighting with daylight sensors. |

| |

- Double-skin façade (DSF) with low E-rating; inner pane twice as thick as typical curtain walls. |

| |

- Atrium and rainwater-recycling waterfall symbolizing sustainability. |

| High-Performance Facades |

- Double-Skin Façade: Enhances thermal performance with advanced glazing and low-E coating. |

| Monitoring of Performance |

- Not explicitly detailed but implied through LEED certifications and integration of daylight sensors. |

| Integration of Building Services Systems |

- Cultural and Functional Hub: Houses offices for Hearst’s media and communications brands, including a newsroom, photo studio, fitness center, and state-of-the-art theater. |

| |

- Public-facing features like art exhibitions and multimedia installations promote cultural engagement. |

| |

- Innovation and Adaptation: Preserves historic infrastructure while incorporating modern systems to meet safety and sustainability standards. |

| Impact and Legacy |

- Adaptive Reuse: Sets a precedent for sustainability and architectural excellence in blending historic and modern design. |

| |

- Integration: Demonstrates successful fusion of old and new, solidifying its status as a New York City icon. |

9.2. New York Times Headquarters, Manhattan, New York City, 2007

The New York Times Headquarters, completed in 2007 in Manhattan, New York City, stands as a beacon of corporate modernism, blending transparency, sustainability, and architectural innovation. Designed by Renzo Piano and FXFowle Architects, the 52-story tower rises to 228 meters (748 feet) to the roof, with its mast extending to 319 meters (1,046 feet). The building’s striking glass and steel façade features 175,000 horizontal ceramic rods acting as solar diffusers, blocking 50% of sunlight while dynamically responding to weather conditions. This transparency extends indoors, with floor-to-ceiling glass and open office layouts fostering a culture of openness and collaboration. Sustainability is at the core of the design, incorporating advanced energy-efficient systems such as cogeneration, underfloor air distribution (UFAD), and automatic shutters, which ensure exceptional thermal performance and energy savings. Ground-floor amenities, including a glass-enclosed garden, café, and a 378-seat auditorium, bridge the building with the urban fabric, promoting civic engagement. The New York Times Headquarters redefines the skyscraper for the digital age, serving as a high-performance model that seamlessly integrates environmental responsibility, functionality, and a commitment to connecting business and community (Lee & Selkowitz, 2006). The following table highlights the prime features of the tower.

Figure 2.

New York Times Headquarters, New York. (Source: Authors).

Figure 2.

New York Times Headquarters, New York. (Source: Authors).

Table 2.

New York Times Headquarters, Manhattan, New York City, 2007.

Table 2.

New York Times Headquarters, Manhattan, New York City, 2007.

| Dimension |

Features |

| Structural Materials and Systems |

- Diagrid Structure: Diamond-pattern steel framework reducing steel usage by 20%, providing unobstructed interior views. |

| |

- Historic Base: Preserves the six-story Art Deco base designed by Joseph Urban (1928), integrating it into the modern tower. |

| |

- Over 90% recycled steel used in construction. |

| Energy-Efficient Design |

- LEED Certification: First NYC building to achieve Gold and Platinum certifications for core, shell, and interiors. |

| |

- Eco-Friendly Features: |

| |

- Natural ventilation and rainwater harvesting systems. |

| |

- Energy-efficient lighting with daylight sensors. |

| |

- Double-skin façade (DSF) with low E-rating; inner pane twice as thick as typical curtain walls. |

| |

- Atrium and rainwater-recycling waterfall symbolizing sustainability. |

| High-Performance Facades |

- Double-Skin Façade: Enhances thermal performance with advanced glazing and low-E coating. |

| Monitoring of Performance |

- Not explicitly detailed but implied through LEED certifications and integration of daylight sensors. |

| Integration of Building Services Systems |

- Cultural and Functional Hub: Houses offices for Hearst’s media and communications brands, including a newsroom, photo studio, fitness center, and state-of-the-art theater. |

| |

- Public-facing features like art exhibitions and multimedia installations promote cultural engagement. |

| |

- Innovation and Adaptation: Preserves historic infrastructure while incorporating modern systems to meet safety and sustainability standards. |

| Impact and Legacy |

- Adaptive Reuse: Sets a precedent for sustainability and architectural excellence in blending historic and modern design. |

| |

- Integration: Demonstrates successful fusion of old and new, solidifying its status as a New York City icon. |

9.3. Burj Khalifa, Dubai, UAE, 2009

The Burj Khalifa in Dubai, completed in 2009, redefined the limits of engineering, architecture, and sustainability as the tallest building in the world. Rising 828 meters (2,717 feet) across 163 stories, this mixed-use marvel, designed by Adrian Smith and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), is a global icon of innovation and cultural significance. It is a new high point of high-performance, especially concrete, tall buildings. Its design draws inspiration from the Hymenocallis flower, with a Y-shaped footprint and a spiraling form that optimizes wind resistance and structural stability. The tower integrates cutting-edge sustainability features, including a condensate collection system that harvests 15 million gallons of water annually for irrigation and water features, high-performance façades that reduce solar heat gain, and a heat recovery system that reuses energy to preheat water. Advanced materials, including high-performance concrete and reflective glazing, enhance efficiency and resilience in Dubai’s extreme climate. Housing 57 elevators and connected seamlessly to Downtown Dubai’s vibrant commercial and entertainment hubs, the Burj Khalifa epitomizes architectural elegance and urban integration. As a testament to human ambition, it is a symbol of Dubai’s emergence as a global city and a benchmark for supertall skyscrapers worldwide (Abdelrazaq, 2010). The following table highlights the prime features of the tower.

Figure 3.

Burj Khalifa, Dubai, UAE. (Source: Authors).

Figure 3.

Burj Khalifa, Dubai, UAE. (Source: Authors).

Table 3.

Burj Khalifa, Dubai, UAE, 2009.

Table 3.

Burj Khalifa, Dubai, UAE, 2009.

| Dimension |

Features |

| Structural Materials and Systems |

- Y-Shaped Footprint: Optimizes wind resistance and enhances structural stability. |

| |

- Buttressed Core System: Reinforced concrete and high-strength steel provide support for extreme height. |

| |

- Material Innovations: High-Performance Concrete (HPC) withstands regional pressures and temperatures. |

| |

- Vertical Transportation: 57 elevators and 8 escalators, including double-deck elevators traveling at speeds of 10 m/s (33 ft/s). |

| Energy-Efficient Design |

- Heat Recovery System: Reuses mechanical energy to preheat water. |

| |

- Green Building Materials: Incorporates eco-friendly, recycled, and locally sourced materials. |

| |

- Integration of Non-Renewable Energy Sources: PV cells on façades generate electricity. |

| |

- Air Quality: Uses low-VOC materials and ensures high indoor air quality. |

| |

- Natural Light Optimization: Maximizes daylighting and outdoor views. |

| High-Performance Facades |

- Reflective Glazing and Aluminum Cladding: Reduce solar heat gain and energy consumption. |

| Monitoring of Performance |

- Not explicitly detailed but implied through energy systems (heat recovery, condensate collection) and façade design. |

| Integration of Building Services Systems |

- Water Management: Harvests 15 million gallons annually from air-conditioning for irrigation and water features. Includes rainwater and greywater reuse. |

| |

- Custom Fountain System: Reuses water for landscaping and the iconic Dubai Fountain, contributing to global appeal. |

| Impact and Legacy |

- Uniqueness and Novelty: Extraordinary height and advanced systems make it a global icon. |

| |

- Connectivity: Integrated with Downtown Dubai, Dubai Mall, residential areas, and entertainment hubs. |

| |

- Aesthetics and Design: Islamic-inspired design evokes the Hymenocallis flower; the spire enhances aesthetics and houses communication equipment. |

9.4. Pearl River Tower, Guangzhou, China, 2012

The Pearl River Tower in Guangzhou, China, completed in 2012, is a groundbreaking example of sustainable skyscraper design that integrates renewable energy and advanced environmental systems. Standing at 309 meters (1,014 feet), this commercial office tower, designed by Adrian Smith and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), exemplifies the synergy between architectural innovation and ecological responsibility. Its aerodynamic form, featuring sculpted wind tunnels and façade inlets, optimizes wind flow to drive integrated turbines, generating renewable electricity. Solar panels on the roof and south façade further contribute to energy efficiency, while a double-skin curtain wall system enhances thermal performance and reduces glare. Chilled ceilings and underfloor ventilation systems provide energy-efficient climate control, improving indoor air quality and occupant comfort. The tower's advanced automation system monitors weather and occupancy, optimizing performance through features like motorized sunshades and daylight harvesting. By seamlessly combining cutting-edge technologies with elegant design, the Pearl River Tower sets a global benchmark for green skyscrapers, showcasing how architecture can harmonize with nature to create a more sustainable and comfortable built environment (Xu & Yeh, 2003). The following table highlights the prime features of the tower.

Figure 4.

Pearl River Tower, Guangzhou, China. (Source: Authors).

Figure 4.

Pearl River Tower, Guangzhou, China. (Source: Authors).

Table 4.

Pearl River Tower, Guangzhou, China, 2012.

Table 4.

Pearl River Tower, Guangzhou, China, 2012.

| Dimension |

Features |

| Structural Materials and Systems |

- Aerodynamic Form: Reduces wind effects and directs wind to mechanical floor openings. |

| |

- Wind Tunnels: Sculpted form with four wind tunnels optimizes wind pressure and turbine efficiency. |

| |

- Façade Inlets: Enhance wind velocity by a factor of 2.5 to maximize turbine performance. |

| |

- Reduced Floor Heights: Efficient HVAC system saved five floors of construction while maintaining functionality. |

| Energy-Efficient Design |

- Daylight Harvesting: Maximizes natural light, reducing reliance on artificial lighting. |

| |

- Building Automation System: Monitors weather and occupancy, optimizing performance with motorized sunshades. |

| |

- Innovative HVAC System: Combines raised floor ventilation with radiant chilled ceilings for efficiency. |

| High-Performance Facades |

- Double-Skin Curtain Walls: Enhance thermal performance by reducing heat gain and glare. |

| |

- Advanced Glazing Systems: Low-E insulated glazing and ventilated cavity walls improve energy efficiency. |

| Monitoring of Performance |

- Building Automation System: Tracks weather and occupancy to adjust systems dynamically, improving efficiency. |

| |

- Airflow Management: Regulates moisture and recirculates warm air for energy-efficient handling. |

| Integration of Building Services Systems |

- Wind Energy: Wind turbines in mechanical floor openings convert wind energy into electricity. |

| |

- Solar Energy: Solar panels on the roof and south façade generate renewable energy. |

| |

- Underfloor Ventilation: Delivers fresh air directly to occupants, improving indoor air quality. |

| |

- Renewable Energy Systems: Power lighting, ventilation, dehumidification, and cooling, reducing the carbon footprint. |

| |

- Chilled Ceiling System: Uses water for cooling, reducing dependence on traditional air systems. |

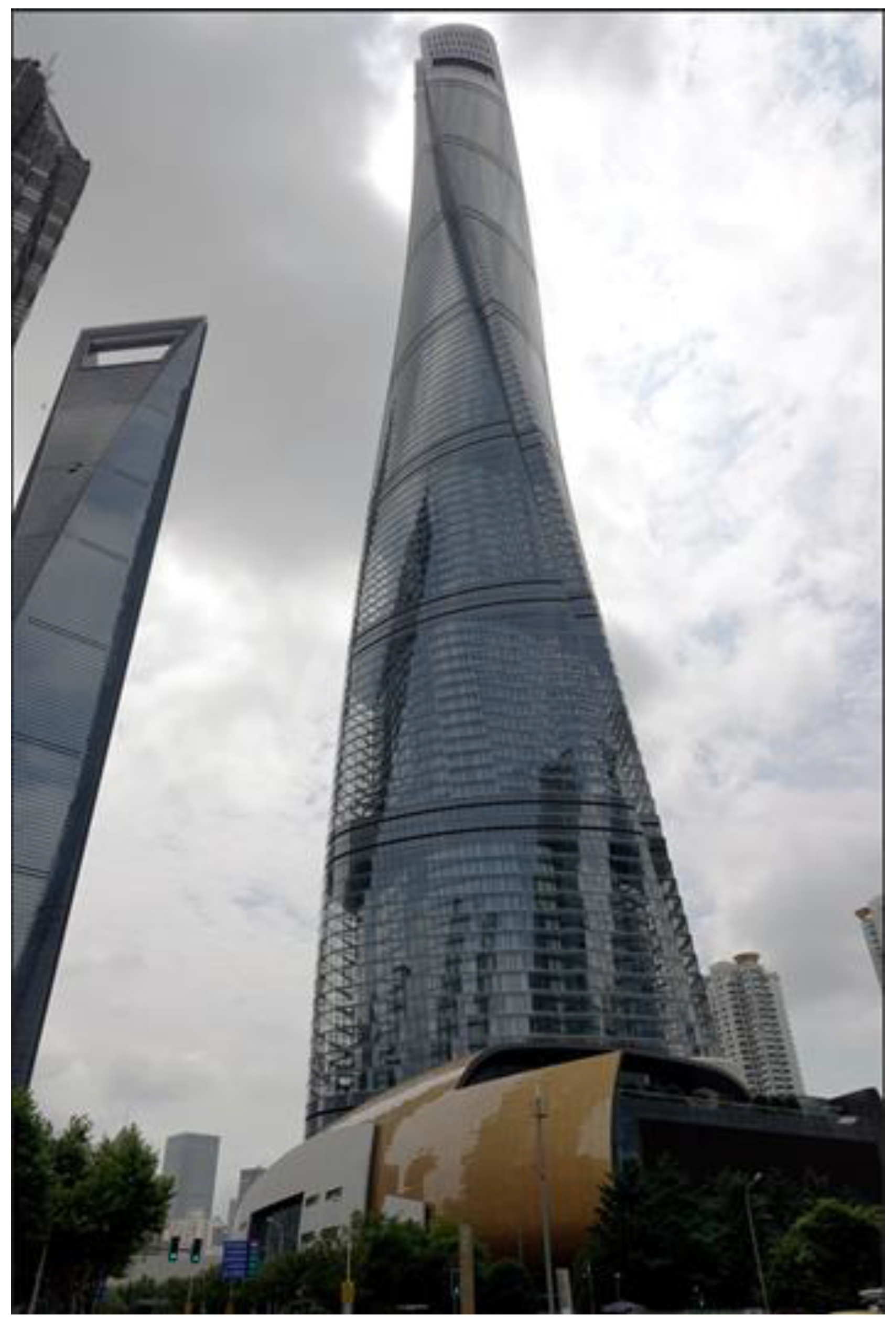

| Impact and Legacy |