Submitted:

08 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Experimental Equipment

2.3. Calculation Approach

- Melting at Tmelt = 5000 K (NVT, δt = 1 fs, t = 100 ps), Nose Thermostat, other calculation parameters were set default [41].

- Quenching to T = 300 K (NVT, δt = 1 fs, quenching rate = 40 K/ps).

- Equilibration at T = 300 K and P = 1 atm (NPT, δt = 1 fs, t = 100 ps). This step allows us to obtain the calculated densities of all modelled glass samples.

- Production at T = 300 K (NVT, δt = 1 fs, t = 100 ps). We obtained 10 different structures to provide sufficient statistical weight in the subsequent analysis of the properties of the studied systems. The use of about 10 such structures to average the calculated characteristics is usually considered sufficient to adequately describe the properties of glasses [43].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Part 1. Characterization of the Glasses and Glass-Ceramics

| Glass name | Eg, eV | Oxide content, mol % |

MoO3 / Bi2O3 ratio | Normalized PL intensity, r.u. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I(Tot) | I(Blue) | I(YR) | ||||||

| Bi2O3 | MoO3 | |||||||

| G1 | 3.62 | 1.00 | 11.17 | 11.17 | 1.00 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| G1.48 | 3.61 | 1.48 | 16.53 | 11.17 | 1.23 | 1.5 | 1.1 | |

| G4.12 | 3.44 | 4.12 | 46.02 | 11.17 | 4.24 | 8.4 | 2.9 | |

| G5.69 | 3.60 | 5.69 | 25.43 | 4.47 | 4.89 | 7.5 | 4.1 | |

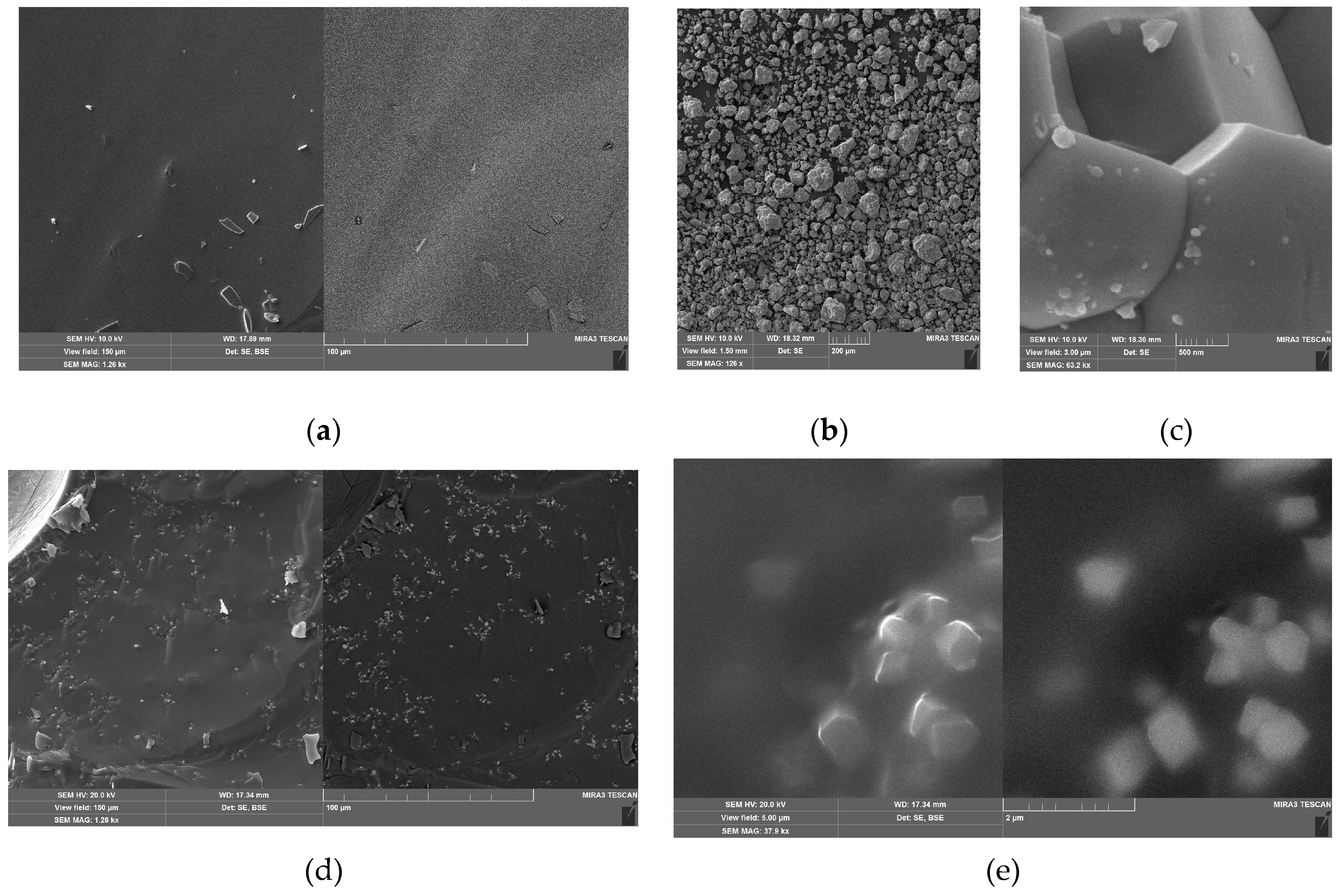

3.1.1. SEM Data

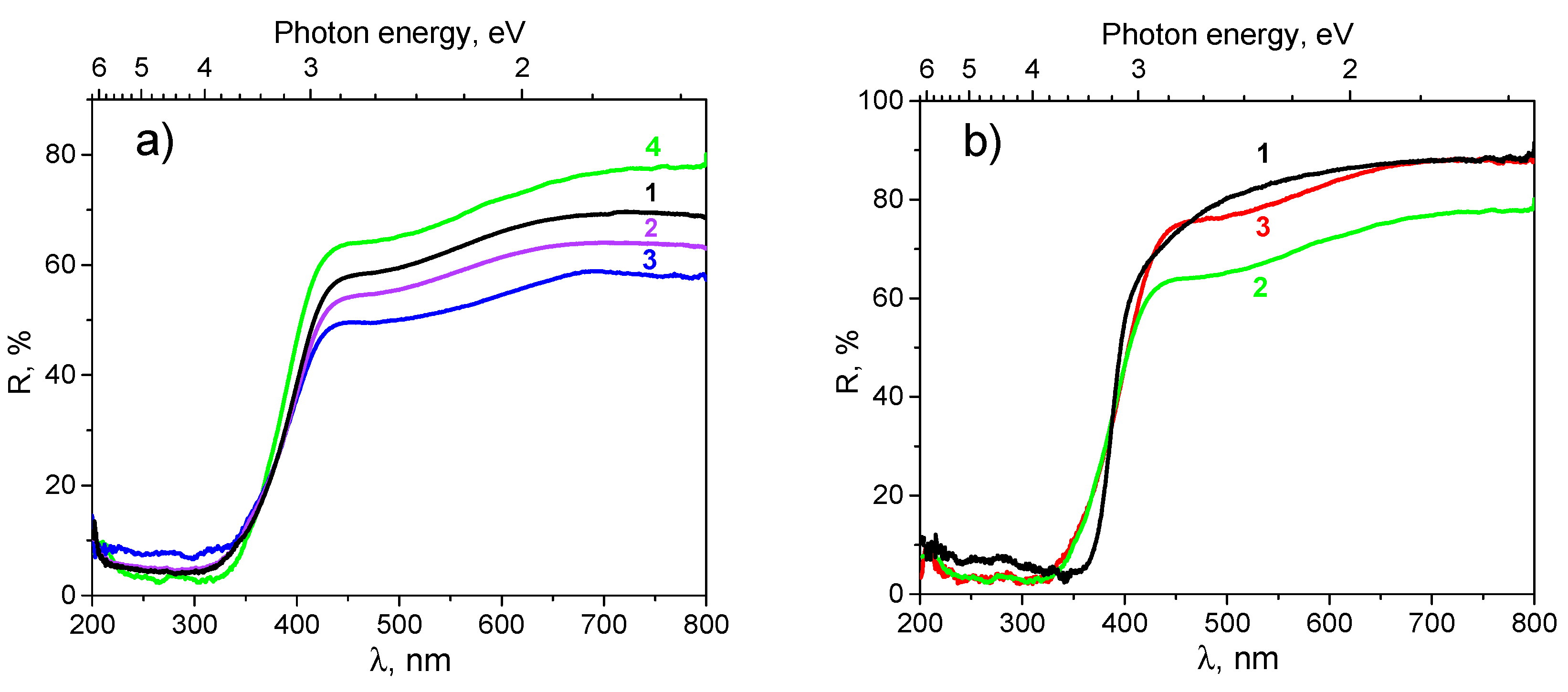

3.1.2. Diffuse Reflection Data

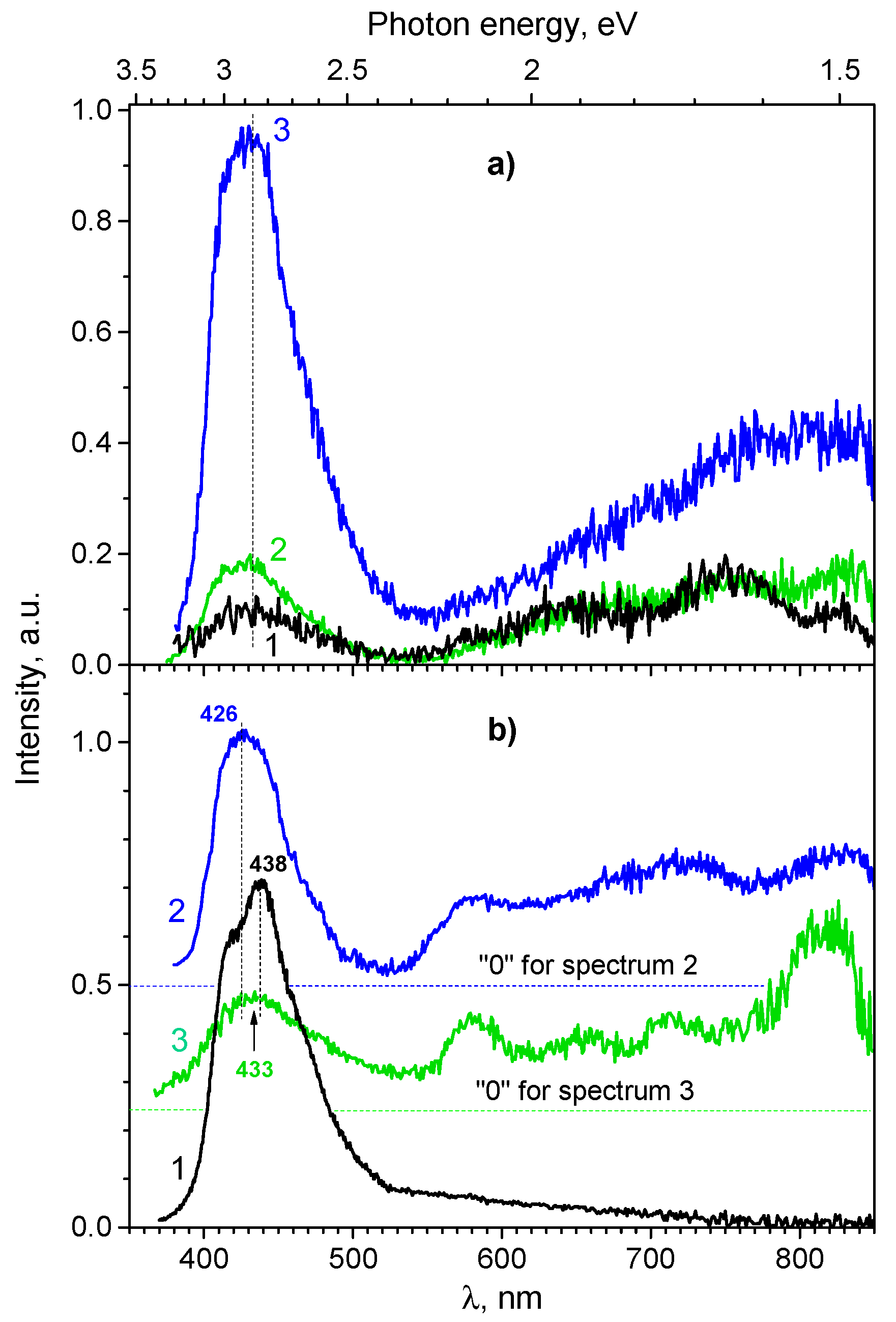

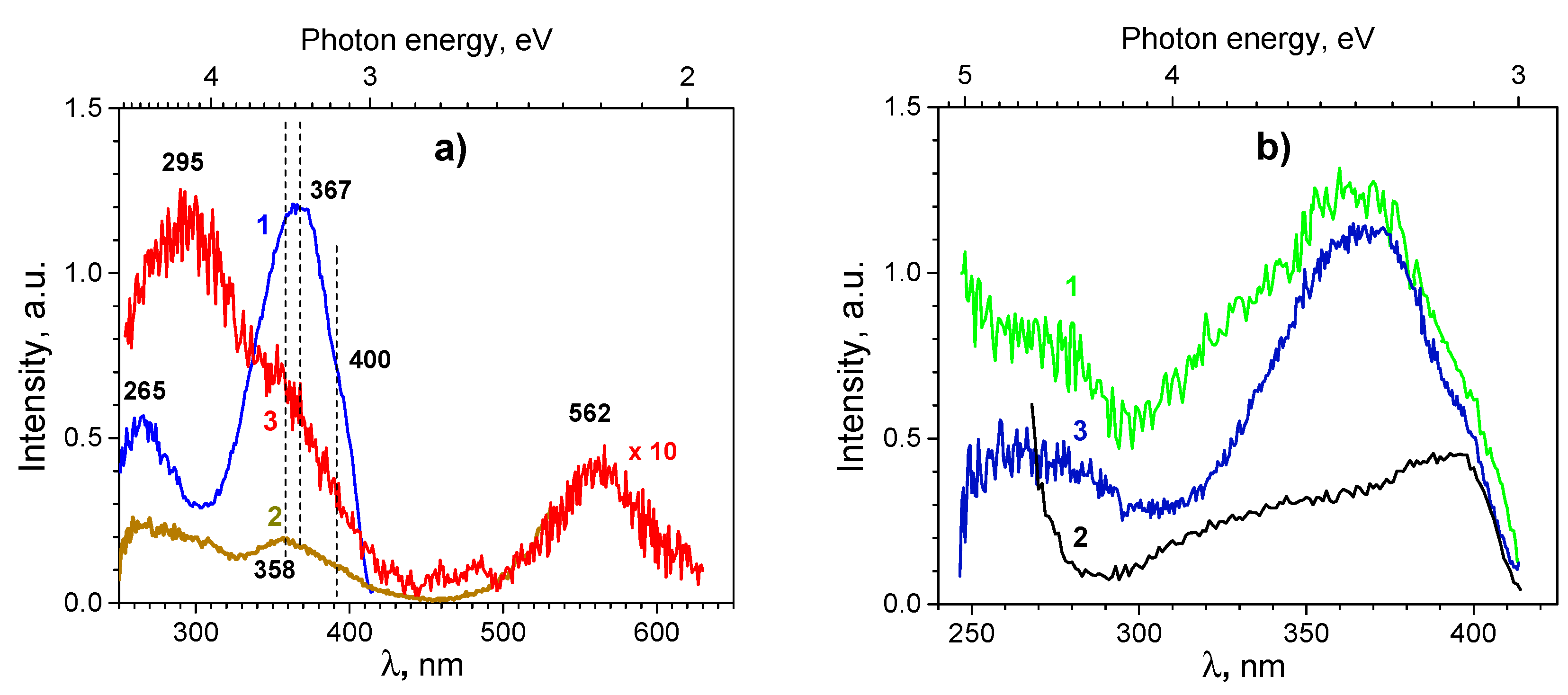

3.1.3. Photoluminescence Spectroscopy

| Glass composition | Band location: region (λmax), nm |

Band assignments and comments | Refs. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PL | PLE | |||

| 33SrO-67B2O3-1Bi2O3 | (560) | 200 – 230 (218) | 1) Transitions in Bi3+ ions: PLE bands at 218, 344, and 355 nm; 2) 2P3/2 ↔ 2P1/2 transitions in Bi2+ ions: PLE band at 480 nm and PL band at 690 nm. Relative contribution of these bands into overall PL or PLE spectra depends on the ratio between glass-forming B2O3 and network modifier SrO oxides. |

[59,60,61,62] |

| 300 – 400 (344) | ||||

| 400 – 550 (480) | ||||

| (690) |

(350) | |||

| (480) | ||||

| MO3-B2O3-CeO2-Bi2O3 (M= Mo or W) | (600) | (300) | PL and PLE bands ascribed to 2P3/2 ↔ 2P1/2 transitions in Bi2+ ions. |

[35] |

| (610) | ||||

| xMoO3–30B2O3–(70–x)Bi2O3 (x = 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5, and 10 in mol%) | (600) | (300) | [57] | |

| (620) | ||||

| (95−x) SiO2·xSrO·5Al2O3·2Bi2O3 (x = 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, in mol%) | (640) | (532) | [52] | |

| MO-B2O3-Bi2O3 (M=Ca, Sr, Ba) | (660) | (470) | 1) 2P3/2 ↔ 2P1/2 transitions in Bi2+ ions: PLE band at 470 nm and PL band at 660 nm; 2) The infrared emission peak possibly comes from Bi ions in low valence state. |

[59,62] |

| (1300) | (808) | |||

| 23B2O3–5ZnO–72Bi2O3–xCuO | (804) | (530) |

3P2 → 3P0 transitions in Bi+ ions: PL band; 3P0 → 1S0 transitions in Bi+ ions: PLE band |

[60] |

3.2. Part 2. Insight from Interphase Layers

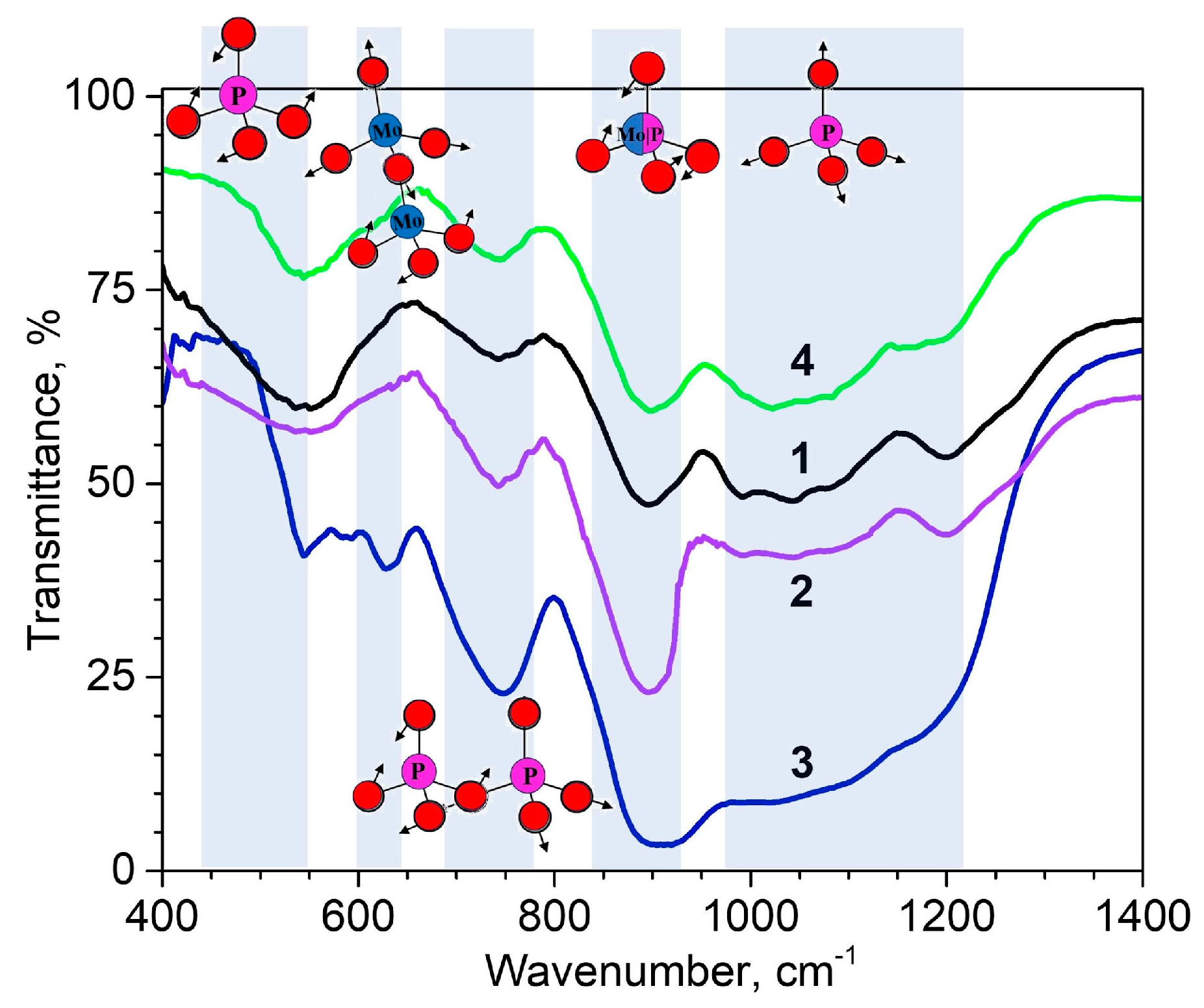

3.2.1. FTIR Spectroscopy Data

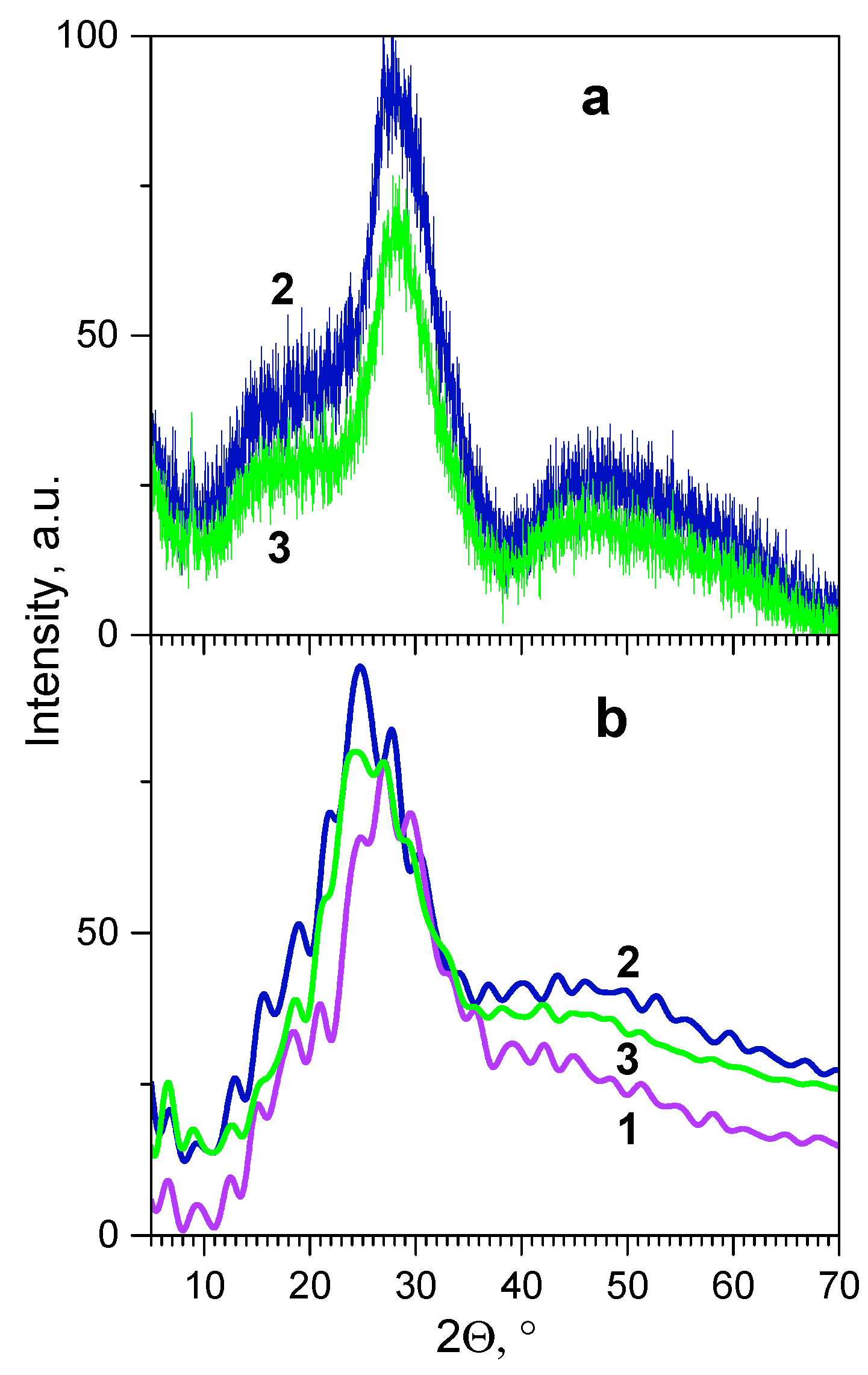

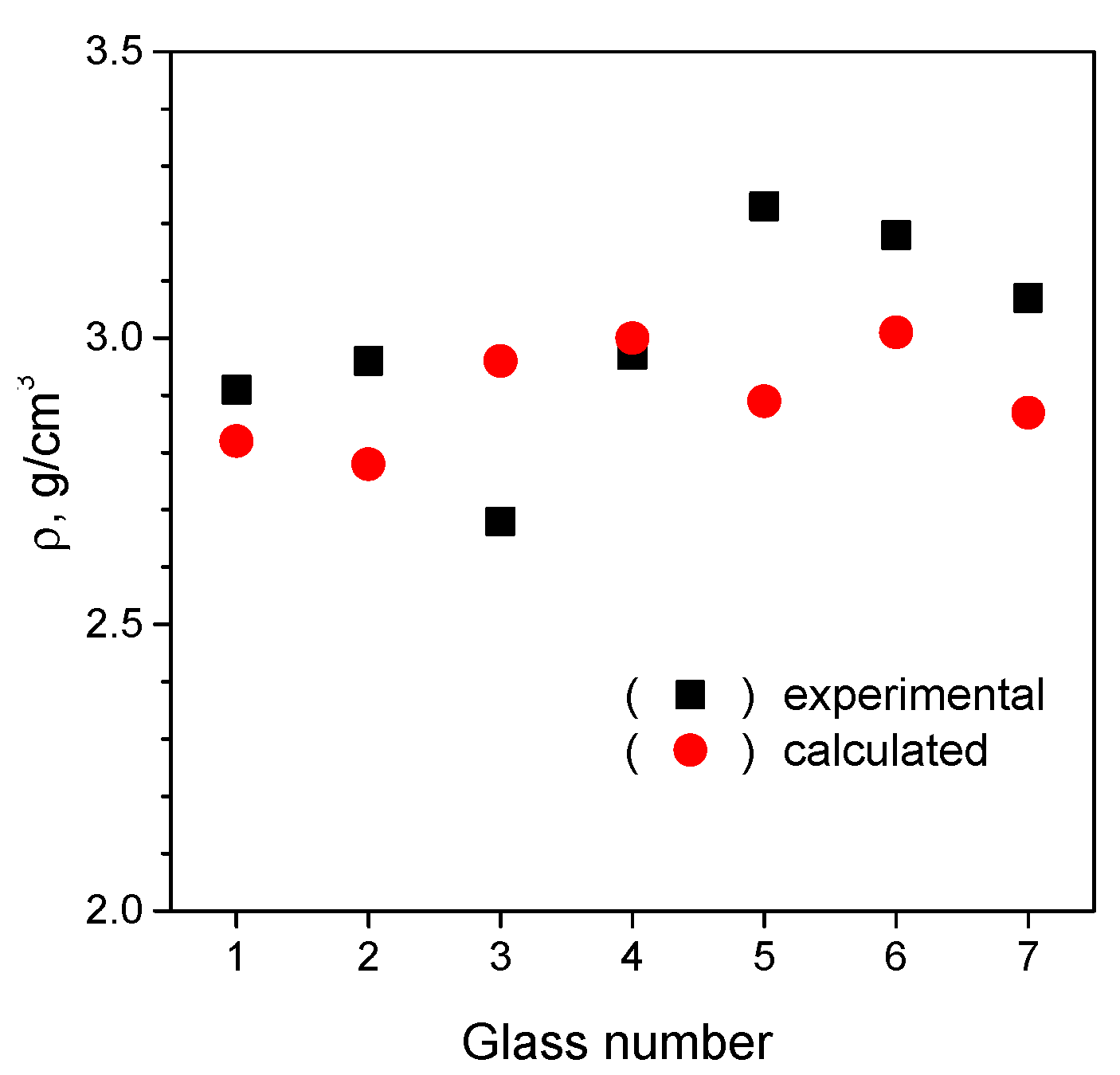

3.2.2. XRD and Density: Experimental and Calculated Data

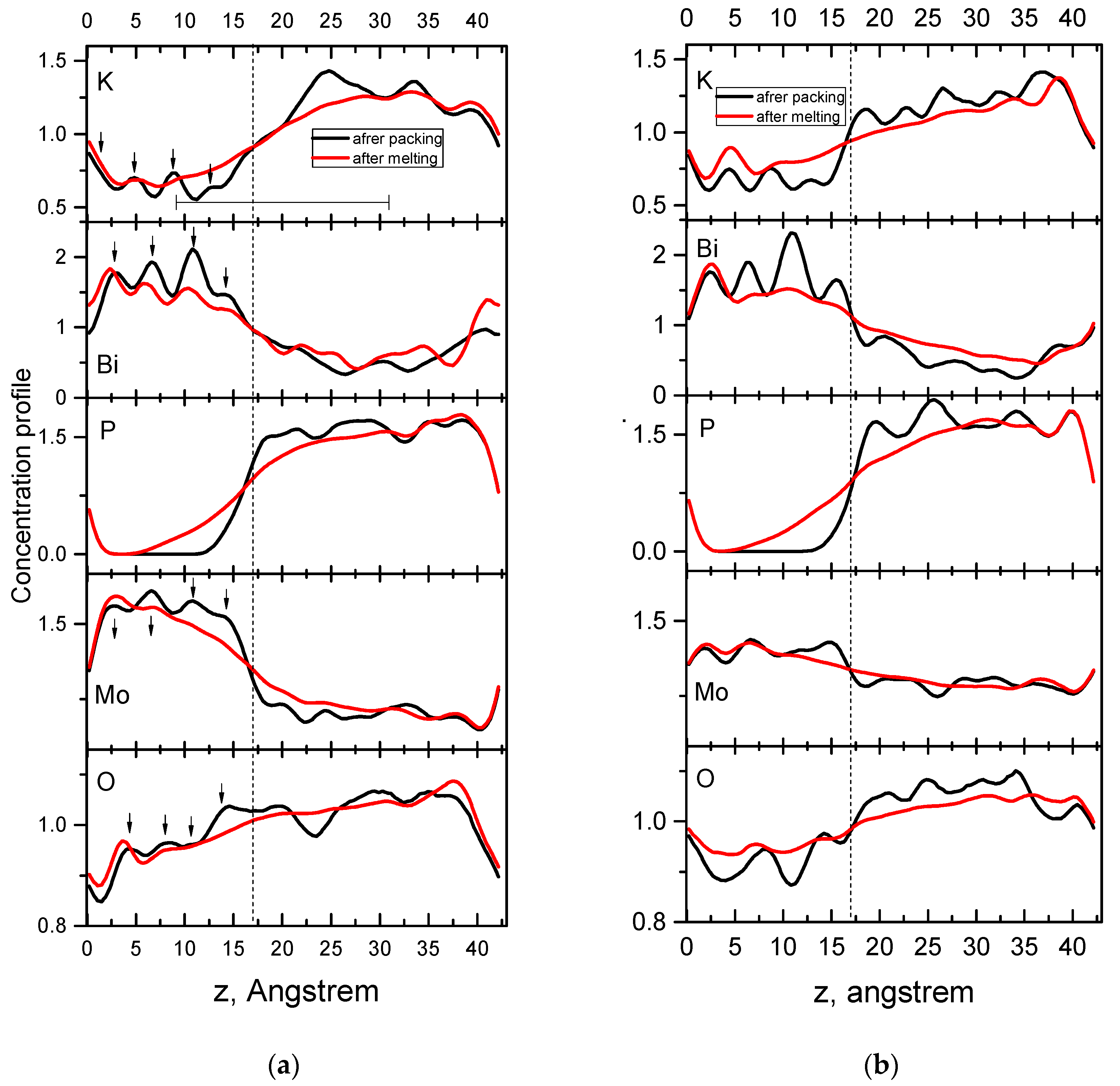

3.2.3. Determination of Thickness and Chemical Composition of Interphase Region

3.2.4. Analysis of Structure of the Nearest Surrounding of Bismuth Cations

| Types of polyhedra |

KBi(MoO4)2 crystal | Glass G5.69 | Interphase | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content, %. | ΔS 1 | Content, %. | ΔS | Content, %. | ΔS | |

| BiO2+ BiO3 | - | - | - | - | 5.3 | - |

| BiO4 | - | - | 4.2 | 0.697 | 15.8 | 0.674-7.591 |

| BiO5 | - | - | 50.0 | 0.433-14.867 | 50.0 | 0.339-12.064 |

| BiO6 | - | - | 41.6 | 1.263-11.995 | 28.9 | 1.503-24.535 |

| BiO7 | - | - | 4.2 | 2.974 | - | - |

| BiO8 | 100 | 0.481 | - | - | - | - |

4. Concluding Remarks

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benyounoussy, S.; Bih, L.; Muñoz, F.; Rubio-Marcos, F.; Bouari, A.E. Effect of the Na2O–Nb2O5–P2O5 glass additive on the structure, dielectric and energy storage performances of sodium niobate ceramics. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Jia, J.; Zhao, J.; Qiao, X.; Du, J.; Fan, X. Glass-ceramic phosphors for solid state lighting: a review. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 2963–2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xu, X.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, T.; Guo, Y.; Lv, J. The effect of Nd3+-doped phosphor-in-glass on WLED. Opt. Mater. 2024, 153, 115552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Shang, F.; Chen, G. NaLaMo2O8: Yb3+, Er3+ transparent glass ceramics: Up-conversion luminescence and temperature sensitivity property. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 16099–16107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Qin, L.; Tang, J.; Li, L.; Shang, F.; Chen, G. Enhanced upconversion luminescence and temperature sensing feature in NaBi(MoO4)2: Er3+, Yb3+ transparent glass ceramics. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2022, 576, 121267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubina, M. K.; Shailajha, S.; Sankaranarayanan, R.; Smily, S.T. Enriched biological and mechanical properties of boron doped SiO2-CaO-Na2O-P2O5 bioactive glass ceramics (BGC). J. Non-Cryst. Solids, 2021, 570, 121007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatti, E.; Miola, M.; Verné, E. Tailoring of bioactive glass and glass-ceramics properties for in vitro and in vivo response optimization: a review. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 4546–4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Engqvist, H.; Xia, W. Glass–ceramics in dentistry: A review. Materials, 2020, 13, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-López, S.; Pascual, M.J. Sintering/crystallization and viscosity of sealing glass-ceramics. Crystals, 2021, 11, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahium, M.M.; Abo-Mosallam, H.A.; Mahdy, E.A. Effect of K2WO4 on structure and properties of low melting glasses in K2O–Fe2O3–P2O5 system as sealing materials. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, R.E.; Reifsnider, K.L.; Jayaraman, K.; El-Zein, M. Interface/interphase concepts in composite material systems. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 1990, 3, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedilko, S.G. Interphases in luminescent oxide nanostructured glass-ceramics. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2023, 34, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, T.; Wu, M.; Pan, Q.; Deng, L.; Zhang, H.; Huang, X.; et al. Regulating interfacial diffusion of nanocrystal-in-glass composites: Insights from atomistic simulation. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 107, 5825–5840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocker, C.; Rüssel, C.; Avramov, I. Transparent nano crystalline glass-ceramics by interface controlled crystallization. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci. 2013, 4, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Acharya, A.; Das, A.S.; Bhattacharya, K.; Ghosh, C.K. Lithium ion conductivity in Li2O–P2O5–ZnO glass-ceramics. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 786, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabler, C.; Schliephake, D.; Heilmaier, M.; Rouxel, T.; Kleebe, H.J.; Narisawa, M.; et al. Influence of SiC/Silica and Carbon/Silica Interfaces on the high-temperature creep of silicon oxycarbide-based glass ceramics: A case study. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2019, 21, 1800596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, T.; Li, H.; Zhang, L. Correlation between dielectric breakdown strength and interface polarization in barium strontium titanate glass ceramics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 96, 042902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorni, G.; Balda, R.; Fernández, J.; Iparraguirre, I.; Velázquez, J.J.; Castro, Y.; et al. Oxyfluoride glass–ceramic fibers doped with Nd3+: Structural and optical characterization. CrystEngComm, 2017, 19, 6620–6629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyu, J.J.; Wu, C.H. Enhancement of photoluminescence intensity of sintered CaAlSiN3: Eu2+ red phosphor-bismuthate glass composites. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2023, 20, 3163–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Mi, J.; Yong, Y.; Mao, B.; Shi, W. First-principles study on the lattice plane and termination dependence of the electronic properties of the NiO/CH3NH3PbI3 interfaces. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2018, 6, 8226–8233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Caballero, P.; Ramallo-López, J.M.; Giovanetti, L.J.; Buceta, D.; Miret-Artés, S.; López-Quintela, M.A.; et al. Exploring the properties of Ag5–TiO2 interfaces: stable surface polaron formation, UV-Vis optical response, and CO2 photoactivation. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2020, 8, 6842–6853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulzendorf, M.; Hinaut, A.; Kisiel, M.; Jöhr, R.; Pawlak, R.; Restuccia, P.; et al. Altering the properties of graphene on Cu (111) by intercalation of potassium bromide. ACS Nano. 2019, 13, 5485–5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, W.J.; Nam, Y.H. A review on phosphor in glass as a high power LED color converter. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 016010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.; Akimov, A.V. Modeling nonadiabatic dynamics in condensed matter materials: some recent advances and applications. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2020, 32, 073001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottoboni, F.S.; Poirier, G.; Cassanjes, F.C.; Messaddeq, Y.; Ribeiro, S.J. Crystallization study of molybdate phosphate glasses by thermal analysis. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2009, 355, 2279–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Du, J.; Cao, X.; Zhang, C.; Xu, G.; Qiao, X.; et, l. A modified random network model for P2O5–Na2O–Al2O3–SiO2 glass studied by molecular dynamics simulations. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 7025–7036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, R. Composition engineering on the structure and transport properties of CaO–SiO2–P2O5 system: A computational insight. Metall. Material. Trans. B. 2024, 55, 1812–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.H. Fundamental condition of glass formation. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1947, 30, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, H.; Onodera, Y.; Tahara, S.; Kohara, S.; Yazawa, K.; Segawa, H.; et al. Structure of alumina glass. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brow, R.K.; Alam, T.M.; Tallant, D.R.; Kirkpatrick, R.J. Spectroscopic studies on the structures of phosphate sealing glasses. MRS Bull. 1998, 23, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, H.K.; Phan, A.L.; Ty, N.M.; Zhou, D.; Qiu, J. Optical bandgaps and visible/near-infrared emissions of Bin+-doped (n= 1, 2, and 3) fluoroaluminosilicate glasses via Ag+-K+ ions exchange process. Opt. Mater. 2021, 112, 110762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabit, H.A.; Sayyed, M.I. , Es-soufi, H.; Bafaqeer, A.; Ismail, A.K. Insights into the influence of Bi2O3 on the structural and optical characteristics of novel Bi2O3–B2O3–TeO2–MgO–PbO glasses. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2024, 56, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, Y.H.; Kim, N.J.; Im, S.H.; Cha, J.M.; Ryu, B.K. Effect of Bi2O3 on structure and properties of zinc bismuth phosphate glass. J. Ceram. Soc. Japan. 2009, 117, P–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, N.; Fukumi, K.; Nakamura, J.; Hidaka, T.; Hashima, H.; Mayumi, Y.; Nishii, J. Optical properties of zinc bismuth phosphate glass. Mater. Sci. Eng.: B. 2009, 161, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Naf, S.M.; Abdel-Hameed, S.A.M.; Fayad, A.M.; Marzouk, M.A.; Hamdy, Y.M. Photoluminescence behavior of MO3-B2O3-CeO2-Bi2O3 (M= Mo or W) glasses and their counterparts nano-glass-ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 21800–21809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Sun, X.Y.; Wen, Y.; Chen, R.; Yu, M.; Du, W.; Xiao, Z. Cyan luminescence from Bi ions-doped borosilicate glass induced by the gradual substitution of MO (M= Ca, Sr, Ba). Opt. Mater. 2023, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terebilenko, K.; Alekseev, O.; Lazarenko, M.; Nedilko, S.G.; Slobodyanik, M.; Boyko, V.; Chornii, V. Luminescent Bi-containing Phosphate-Molybdate Glass-Ceramics. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 10th International Conference Nanomaterials: Applications & Properties (NAP), Sumy, Ukraine, 9-13 November 2020. pp. 01–1. [CrossRef]

- Chornii, V.; Boyko, V.; Nedilko, S.G.; Terebilenko, K.; Slobodyanik, M. Synthesis, Morphology and Luminescence Properties of Pr3+- containing Phosphate-Molybdate Glass-Ceramics. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 11th International Conference Nanomaterials: Applications & Properties (NAP), Odesa, Ukraine, 5-11 September 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terebilenko, K.; Miroshnichenko, M.; Tokmenko, I.; Chornii, V.; Hizhnyi, Y.; Nedilko, S.; Slobodyanik, N. Synthesis and luminescence properties of KBi(MoO4)2:Eu3+. Solid State Phenom. 2015, 230, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hizhnyi, Y.; Nedilko, S.G.; Chornii, V.; Nikolaenko, T.; Zatovsky, I.V.; Terebilenko, K.V.; Boiko, R. Electronic structure and luminescence spectroscopy of M'Bi(MoO4)2 (M'= Li, Na, K), LiY(MoO4)2 and NaFe(MoO4)2 molybdates. Solid State Phenom. 2013, 200, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BIOVIA Materials Studio. An Integrated, Multi-scale Modeling Environment. Available online: https://www.3ds.com/products-services/biovia/products/molecular-modeling-simulation/biovia-materials-studio (accessed on: 22.01.2025).

- Sahu, P.; Pente, A.A.; Singh, M.D.; Chowdhri, I.A.; Sharma, K.; Goswami, M.; et al. Molecular dynamics simulation of amorphous SiO2, B2O3, Na2O–SiO2, Na2O–B2O3, and Na2O–B2O3–SiO2 glasses with variable compositions and with Cs2O and SrO dopants. J. Phys. Chem. B, 2019, 123(29), 6290-6302. [CrossRef]

- Dicks, O.A.; Shluger, A.L. Theoretical modeling of charge trapping in crystalline and amorphous Al2O3. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter. 2017, 29, 314005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dag, S.; Wang, L.W. Atomic and electronic structures of nano-and amorphous CdS/Pt interfaces. Phys. Rev. B. 2010, 82, 241303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laasonen, K.; Car, R.; Lee, C.; Vanderbilt, D. Implementation of ultrasoft pseudopotentials in ab initio molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. B. 1991, 43, 6796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfrommer, B.G.; Côté, M.; Louie, S.G.; Cohen, M.L. Relaxation of crystals with the quasi-Newton method. J. Comput. Phys. 1997, 131, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubelka, P. New contributions to the optics of intensely light–scattering materials. Part I. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1948, 38, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tauc, J.; Grigorovici, R.; Vancu, A. Optical properties and electronic structure of amorphous germanium. Phys. Status Solidi (B). 1966, 15, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Cheng, B.M.; Tanner, P.A. Optical properties of selected 4d and 5d transition metal ion-doped glasses. RSC Adv., 2017, 7, 26411–26419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, F.; Liu, H. Spectroscopy of transition metal ions in inorganic glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Sol. 1986, 80, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunakumar, R.; Krushna, B.R.; Ramakrishna, G.; Mamatha, G.R.; Sharma, S.C.; Kumar, S.; et al. Development of highly thermal-stable blue emitting Y4Al2O9: Bi3+ phosphors for w-LEDs, fingerprint and data security applications. Mater. Sci. Eng.: B. 2025, 312, 117833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnikov, A.; Mihokova, E.; Nikl, M.; Zazubovich, S.; Zhydachevskyy, Y. Luminescence spectroscopy and origin of luminescence centers in Bi-doped materials. Crystals, 2020, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Luo, H.; Peng, M. Novel bismuth activated blue-emitting phosphor Ba2Y5B5O17: Bi3+ with strong NUV excitation for WLEDs. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2019, 7, 11227–11233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorenko, Y.; Gorbenko, V.; Voznyak, T.; Vistovsky, V.; Nedilko, S.; Nikl, M. Luminescence of Bi3+ ions in Y3Al5O12: Bi single crystalline films. Radiat. Meas. 2007, 42, 882–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Yang, L.; Qiu, J.; Chen, D.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, C. Effect of various alkaline-earth metal oxides on the broadband infrared luminescence from bismuth-doped silicate glasses. Solid State Commun. 2006, 140, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Naf, S.M.; Elwan, R.L.; ElBatal, H.A. Photoluminescence, optical properties, thermal behavior and nanocrystallization of molybdenum-doped borobismuthate glasses. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2018, 29, 4915–4925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, S.K.; Yadav, J.; Naidu, B.S. Upconversion properties of Er, Yb co-doped KBi(MoO4)2 nanomaterials for optical thermometry. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 20051–20060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.F. Luminescence properties of bismuth-doped SrO-B2O3 Glasses with multiple valences state, Optik. 2015, 126, 4115–4118. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Chakradhar, R.P.S.; Rao, J.L.; Karmakar, B. Electron paramagnetic resonance, optical absorption and photoluminescence properties of Cu2+ ions in ZnO–Bi2O3–B2O3 glasses. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2013, 346, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Jiang, N.; Zhu, B.; Yang, H.; Ye, S.; Lakshminarayana, G.; et al. Multifunctional bismuth-doped nanoporous silica glass: from blue-green, orange, red, and white light sources to ultra-broadband infrared amplifiers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, J.; Yu, H. Near infrared luminescence of bismuth-doped MO-B2O3 (M= Ca, Sr, Ba) glasses. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol.-Mater. Sci. Ed., 2015, 30, 715–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, H. K.; Trung, N.D.; Tam, N.M.; Ha, L.T.; Ha, C.V.; Zhou, D.; Qiu, J. Optical band gaps and spectroscopy properties of Bim+/Eun+/Yb3+ co-doped (m= 0, 2, 3; and n= 2, 3) zinc calcium silicate glasses. RSC Adv., 2023, 13, 6861–6871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.S.; Raja, V.S.; Veeraiah, N. Molybdenum ion as a structural probe in PbO-Sb2O3-B2O3 glass system by means of dielectric and spectroscopic investigations. Eur. Phys. J.-Appl. Phys. 2007, 37, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.; Mendioroz, A.; Balda, R.; Arriandiaga, M.A.; Weber, M.J. Site-selective laser spectroscopy of Mo3+ in phosphate glass. Phys. Rev. B. 1995, 52, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faqyr, F.; Boukili, A.E.; Boudad, L.; El Amraoui, M.; Taibi, M.; Guedira, T. Novel Li2− 2xK2xPbP2O7 glass system: Synthesis, thermal, structural and dielectric properties. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2024, 167, 112664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thipperudra, A.; Manjunatha, S.; Pushpalatha, H.L.; Kumar, M.P. DSC, FTIR studies of borophosphate glasses doped with SrO, Li2O. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2021, 1921, 012110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, M.; Rada, S.; Pascuta, P.; Culea, E. Structural properties of molybdenum-lead-borate glasses. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2010, 77, 832–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, A.; Majumdar, S.; Ghosh, A. Effect of network structure on dynamics of lithium ions in molybdenum phosphate mixed former glasses. Solid State Ionics 2020, 347, 115238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Llunell, D. Casanova, J. Cirera, P. Alemany, S. Alvarez, Shape: Program for the Stereochemical Analysis of Molecular Fragments by Means of Continuous Shape Measures and Associated Tools. Departament de Quhımica Fhısica, Departament de Quhımica Inorganica, and Institut de Quhımica Teorica i Computacional Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2013.

- Klevtsov, P.V.; Vinokurov, V.A.; Klevtsova, R.F. Double molybdates and tungstates of alkali metals with bismuth, M+Bi(TO4)2. Kristallografiya, 1973, 18, 1192–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky, M.; Avnir, D. Continuous symmetry measures. 5. The classical polyhedra. Inorg. Chem. 1998, 37, 5575–5582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).