Submitted:

18 June 2024

Posted:

19 June 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

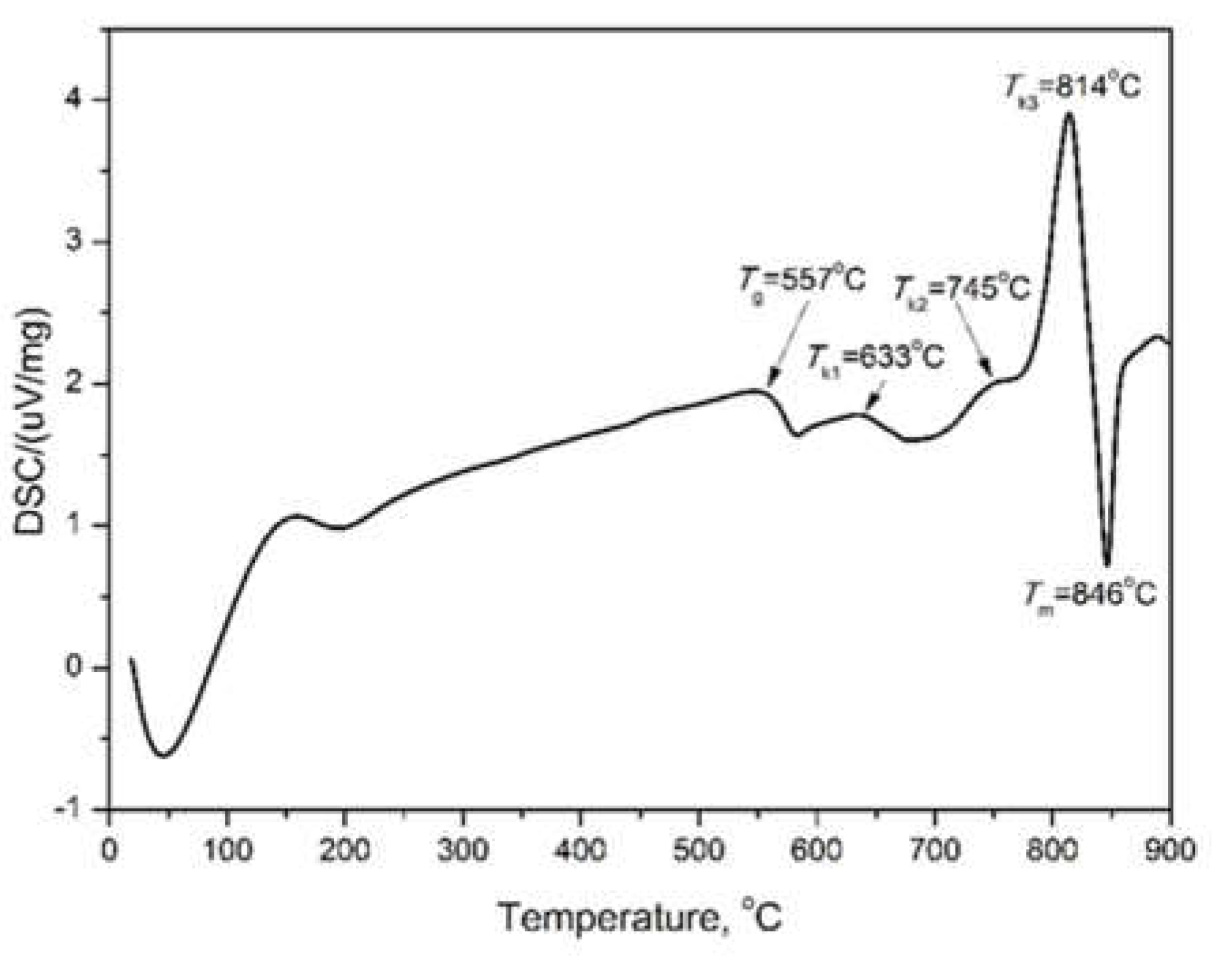

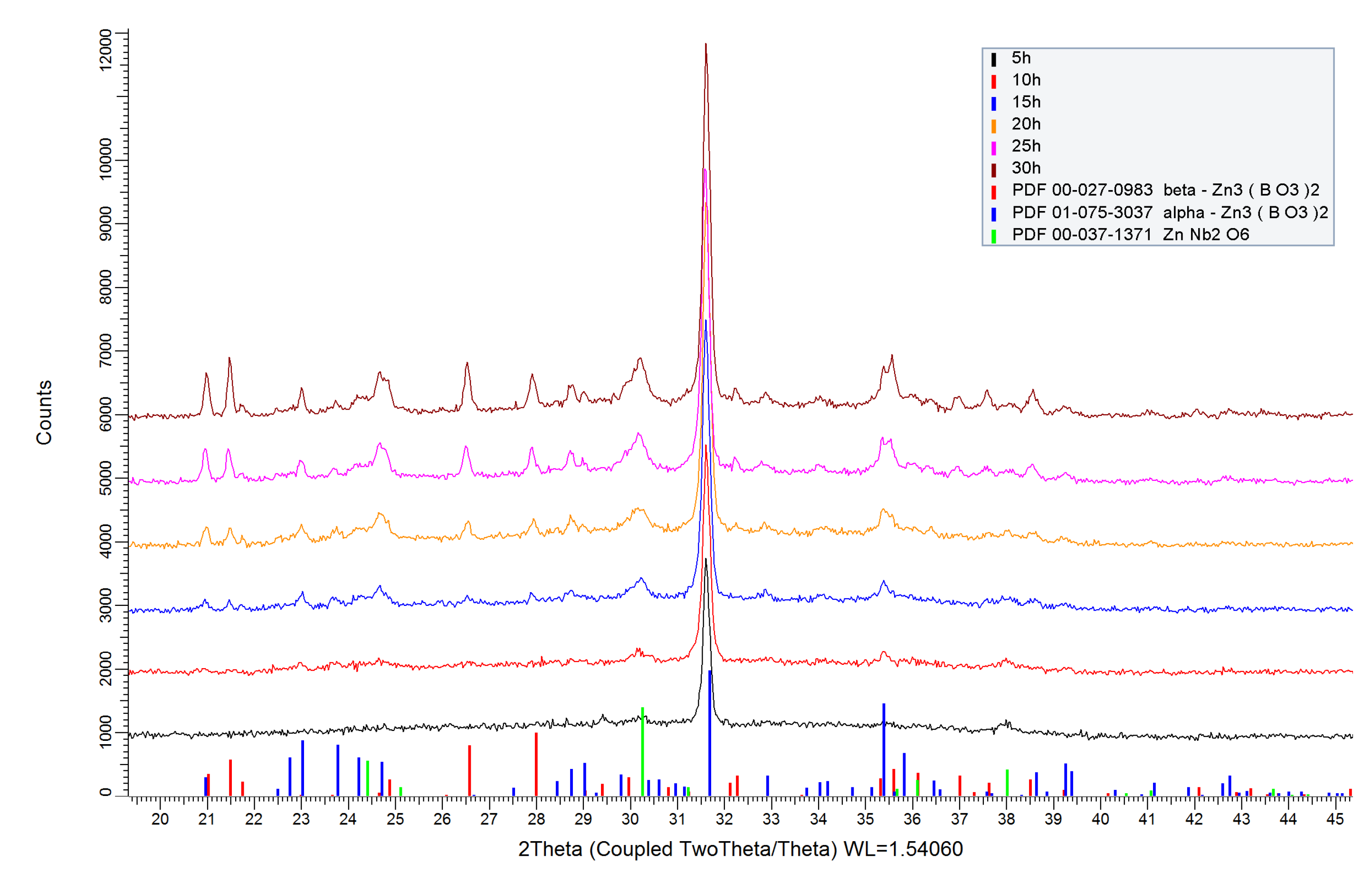

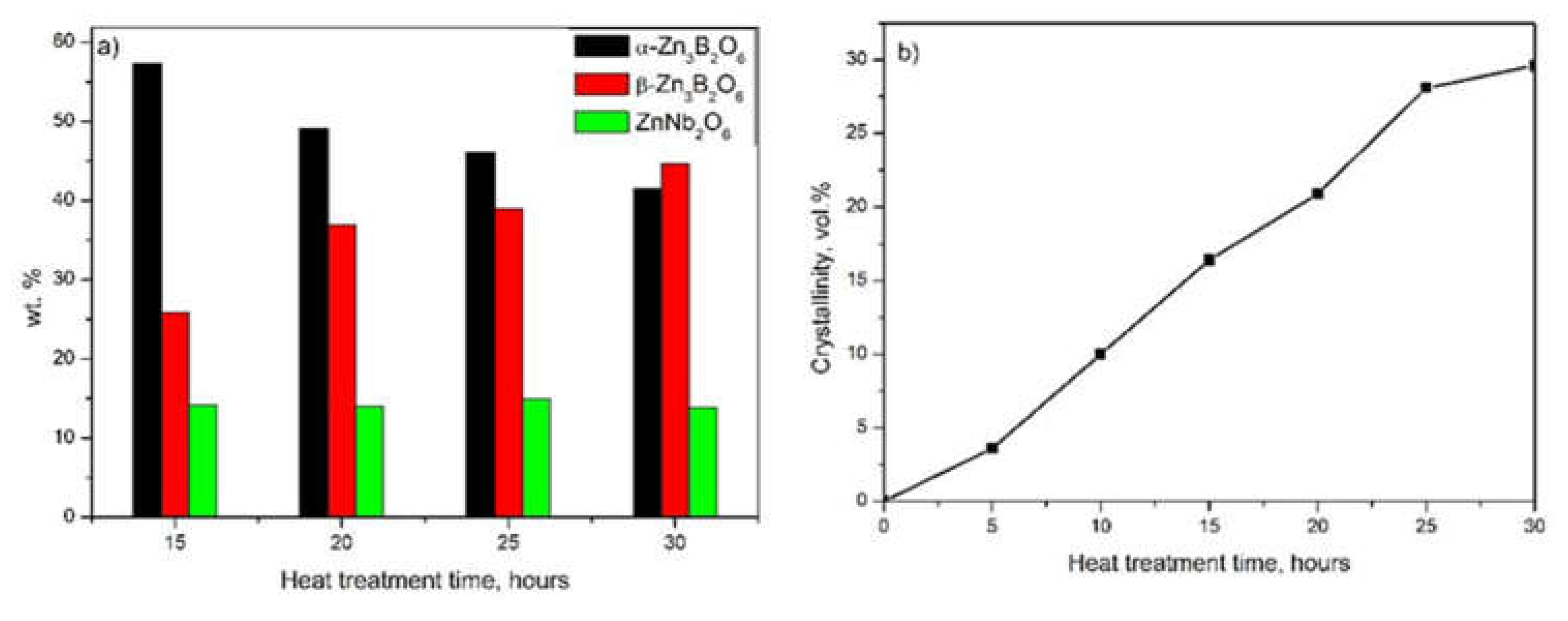

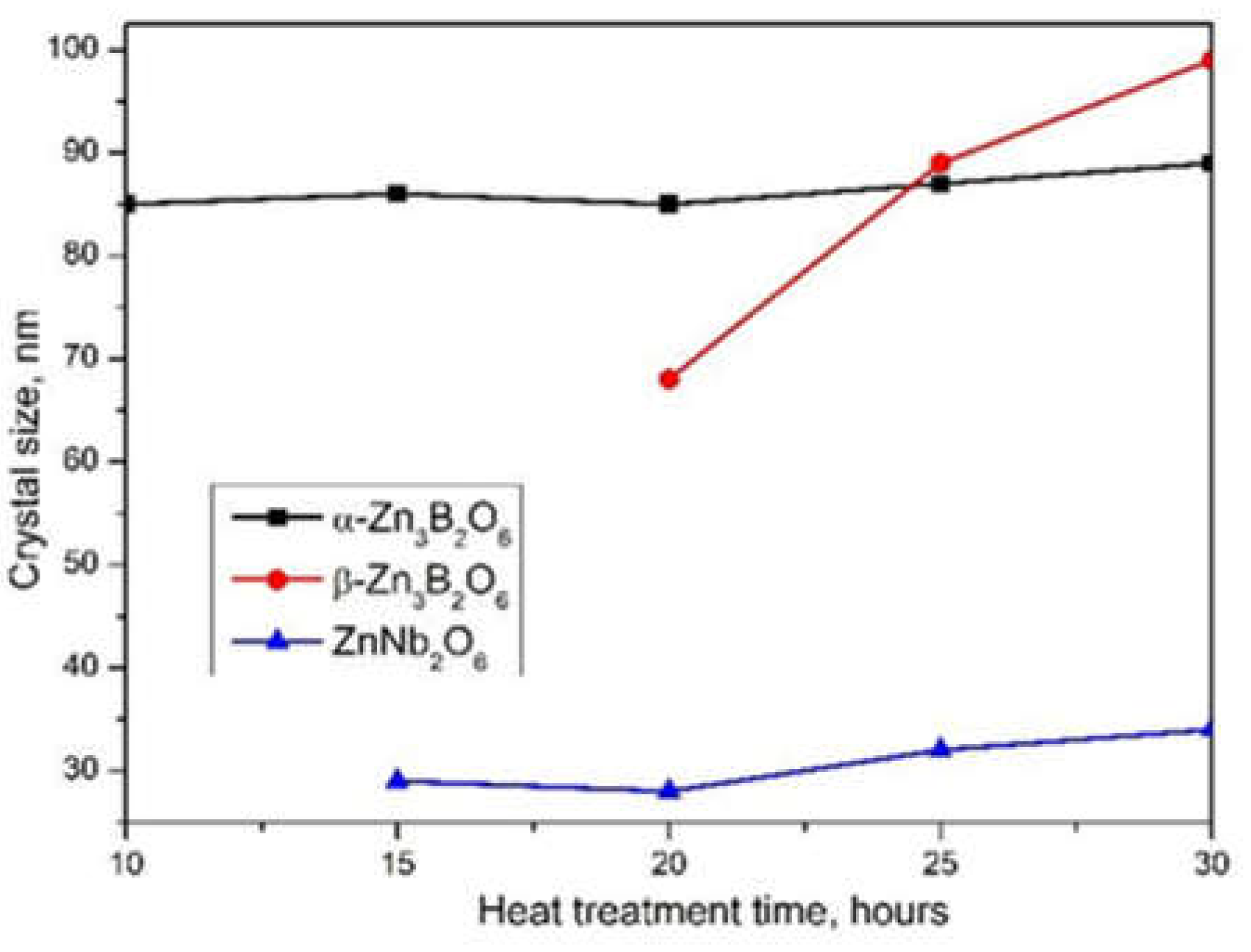

2.1. Thermal Analysis and XRD Data

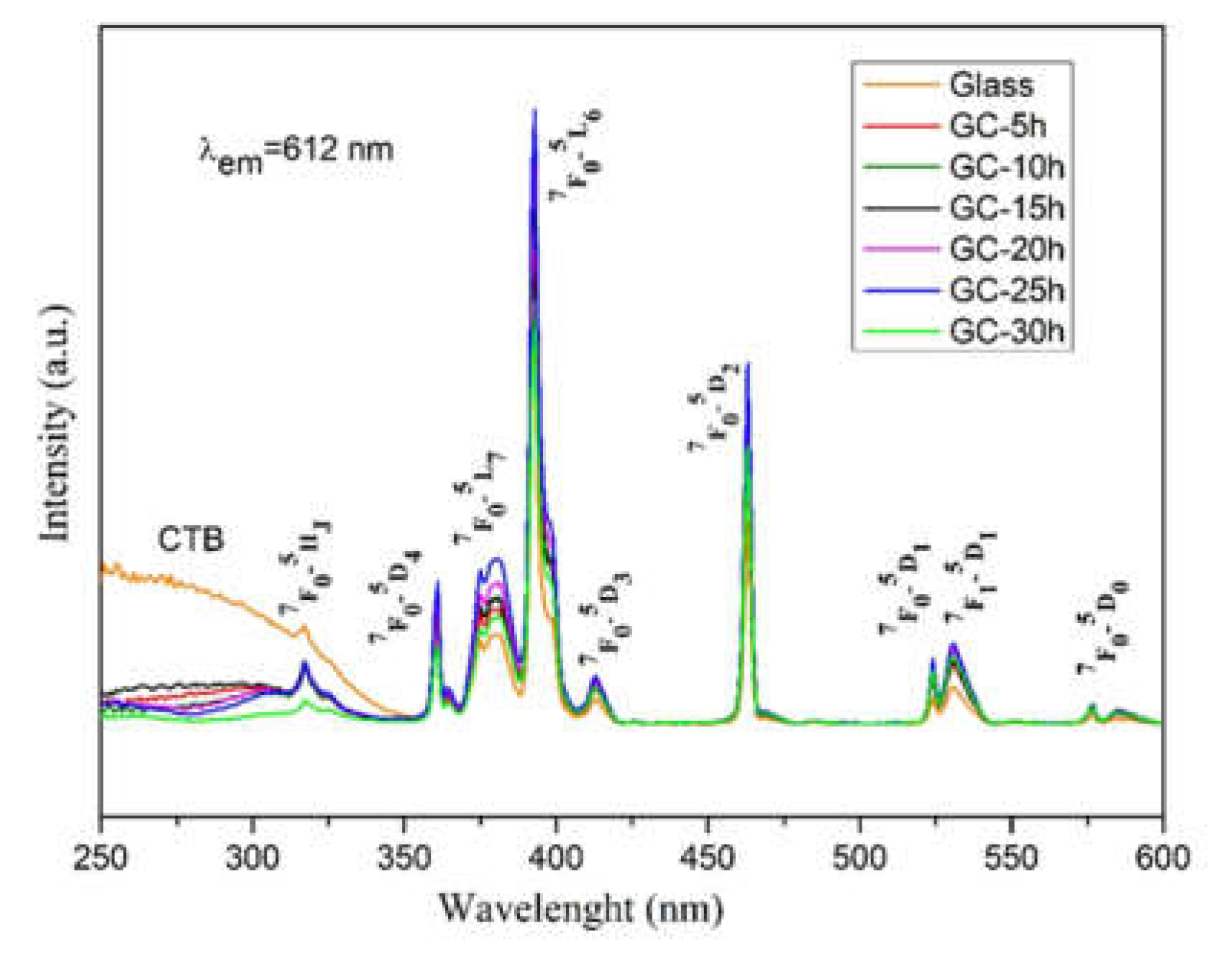

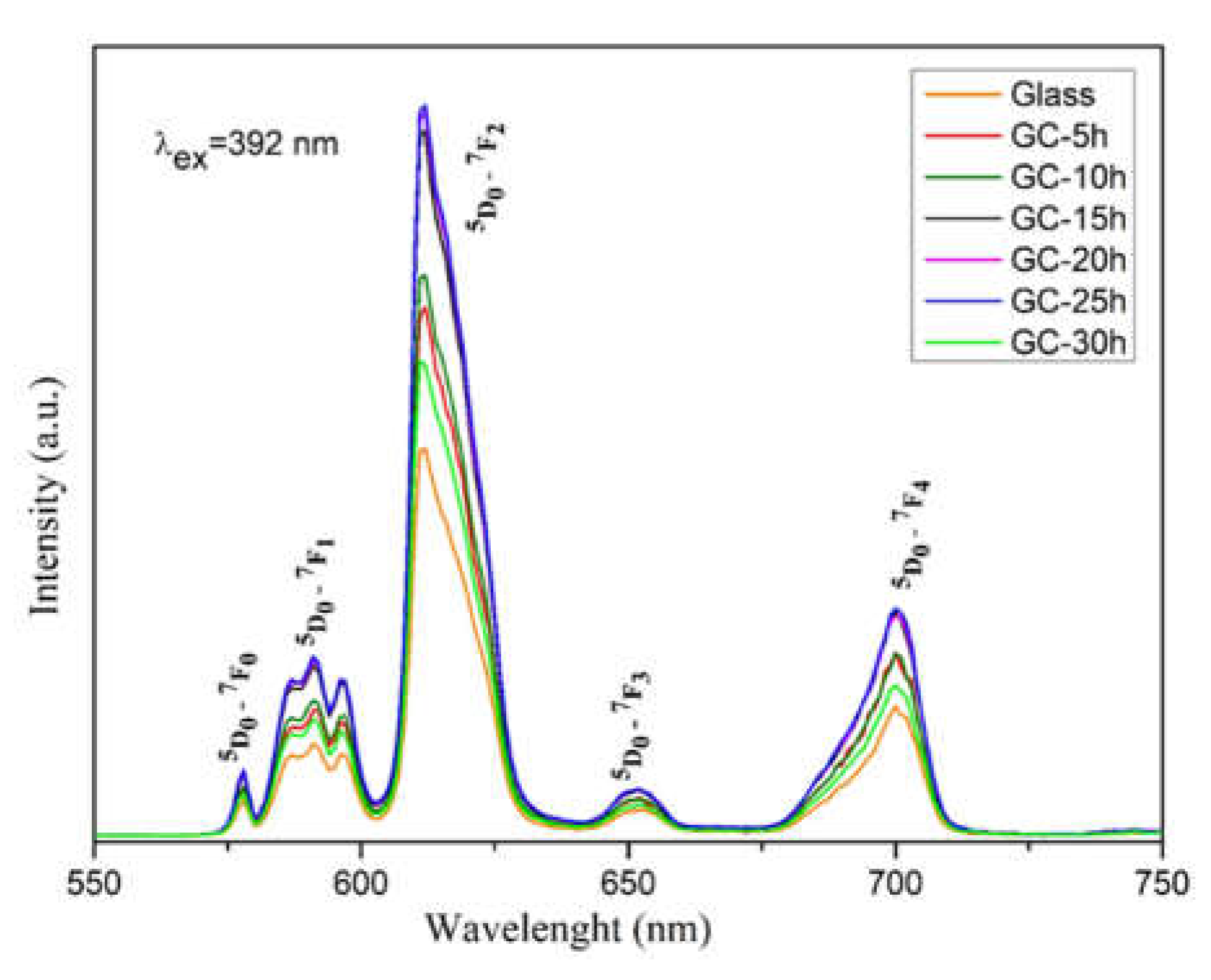

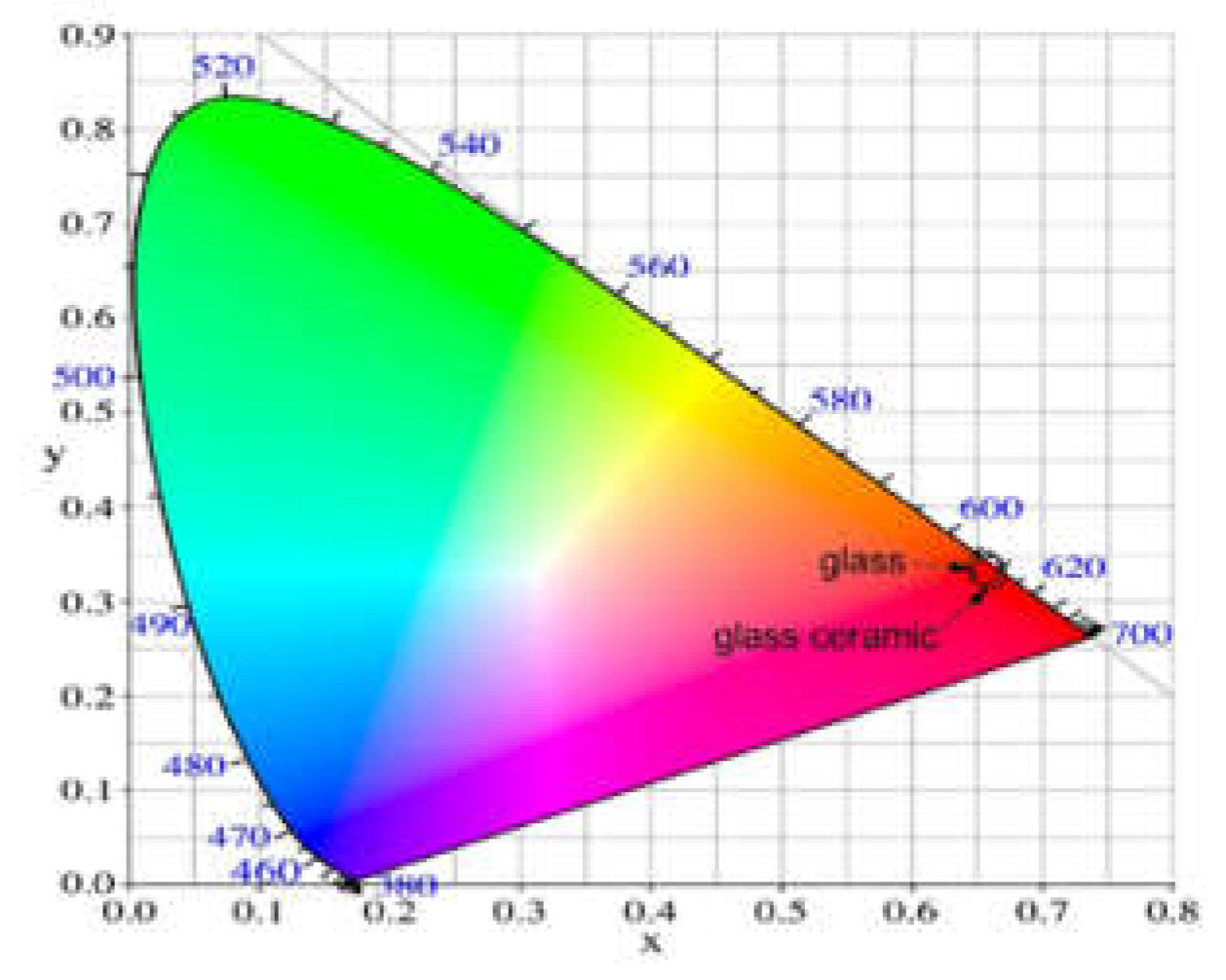

2.2. Luminescent Properties

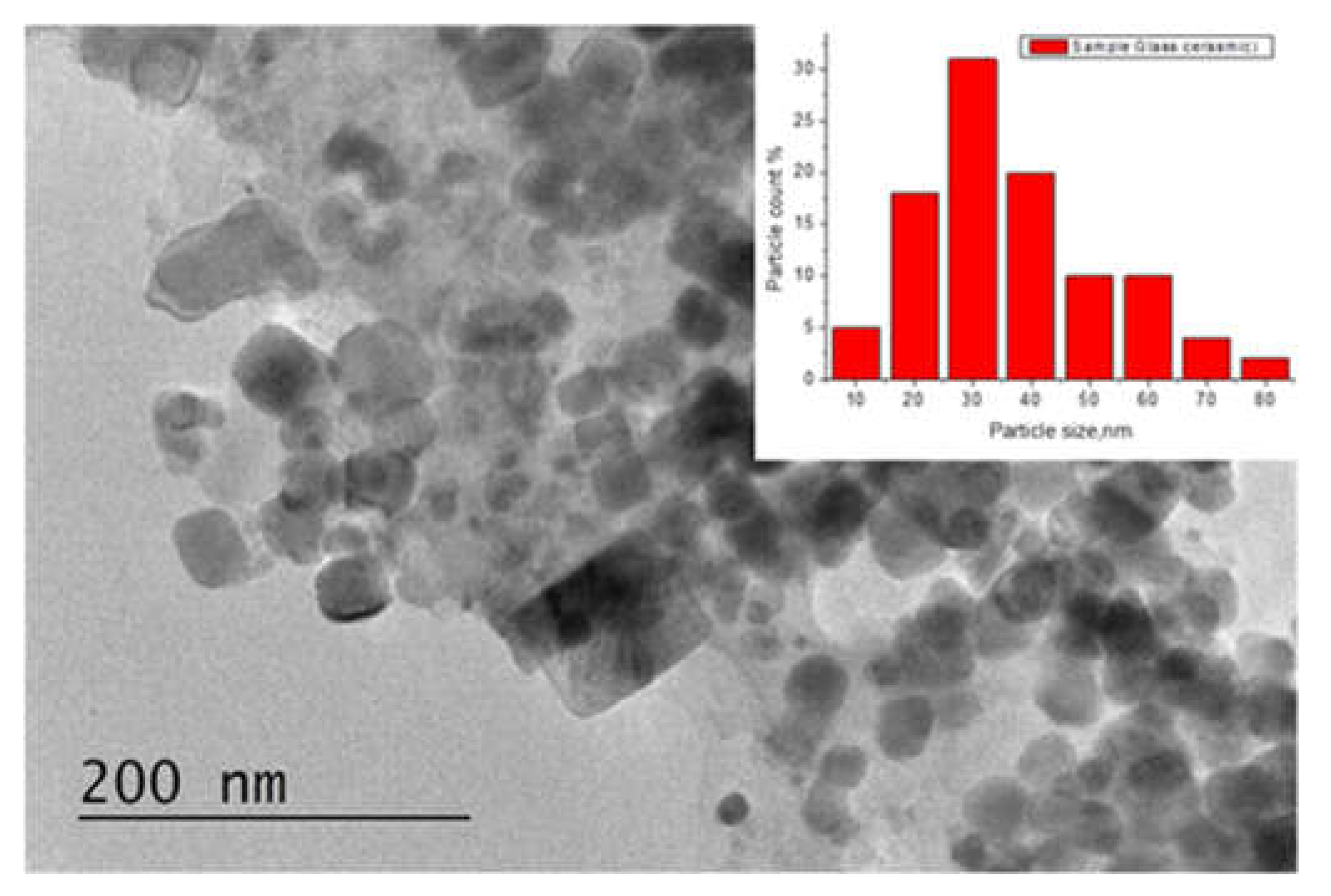

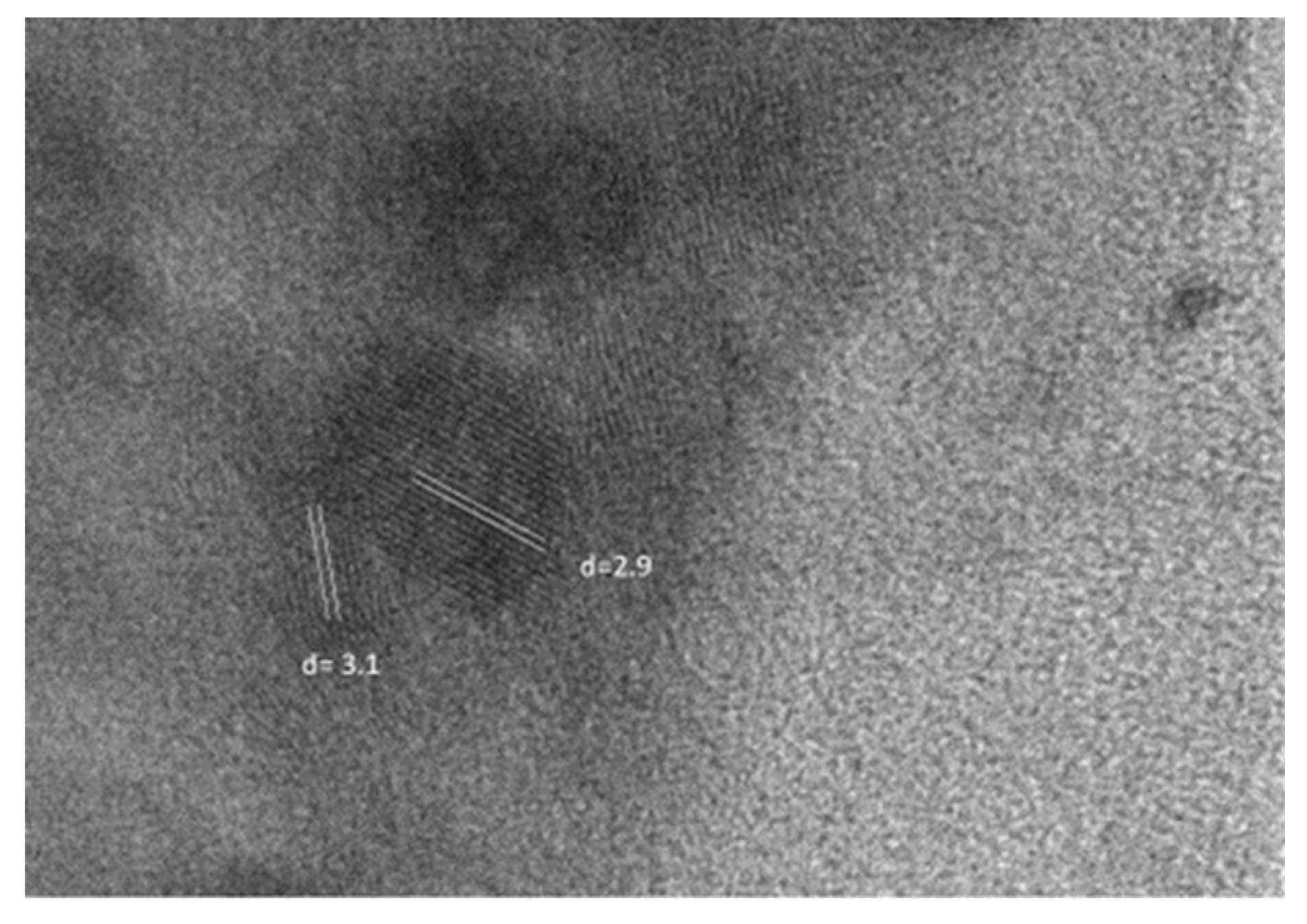

2.3. TEM Investigations and Density Measurment

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fedorov, P. P.; Luginina, A. A.; A. Popov, I. Transparent oxyflouride glas ceramics. J. Fluor. Chem. 2015, 172, 22-50.

- Erth, D. Photoluminescenec in Glass and Glass Ceramics. IOP Conf. Series:Materials Science and Engineering 2009, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Marcondes, L. M.; Evangelista, R. O.; Gonçalves, R. R.; de Camargo, A. S.S.; Manzani, D.; Nalin, M.; Cassanjes, F. C.; Poirier, G. Y. Er3+-doped niobium alkali germanate glasses and glass-ceramics: NIR and visible luminescence properties. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2019, 521, 119492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M.; Righini, G. C. Glass-ceramic materials for guided-waste optics. Int. J. Appl. Sci. 2015, 6, 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Iordanova, R.; Milanova, M.; Yordanova, A.; Aleksandrov, L.; Nedyalkov, N.; Kukeva, R.; Petrova, P. Structure and Luminescent Properties of Niobium-Modified ZnO-B2O3:Eu3+ Glass. Mater. 2024, 17, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, E.M. Phase Equilibria in the System Niobium Pentoxide-Boric Acid. J Res. Nationa Bureau of Standards - A. Phys. Chem. 1966, 70A, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballman, A.A.; Brown, H. Czochralski growth in the zinc oxide-niobium pentoxide system. J. Cryst. Growth, 1977, 41, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phase equilibrium diagrams, AcerS-NIST, CD-ROM Database, Version 3.1.0.

- Chen, X.; Hue, H.; Chang, X.; Zhang, Li; Zhao, Y.; Zuo, J.; Zang, H.; Xiao, W. Syntheses and crystal structures of the α- and β-forms zinc orthoborate, Zn3B2O6. J. Alloys. Compd. 2006, 425, 96-100.

- Dimitriev, Y.; Yordanova, R.; Aleksandrov, L.; Kostov, K. Boromolybdate glasses containing rare earth oxides. Phys. Chem. Glasses: Eur. J. Glass Sci. Technol. B. 2009, 50, 212–218. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Blanco, S.; Fayos, J. The crystal structure of zinc orthoborate, Zn3(BO3)2. Z. Kristallogr. 1968, 127, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Baur, W.; Tillmanns, E. The space group and crystal structure of trizinc diorthoborate. Z. Kristallogr. 1970, 131, 213–221. [CrossRef]

- Binnemans, K. Interpretation of europium (III) spectra. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2015, 295, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Song, J.; Chen, D.; Yuan, S.; Jiang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, G. Three-photon-excited upconversion luminescence of niobium ions doped silicate glass by a femtosecond laser irradiation. Opt. Express 2008, 16, 6502–6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimpoeno, W.A.; Lintang, H.O.; Yuliati, L. Zinc oxide with visible light photocatalytic activity originated from oxygen vacancy defects. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 833, 012080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasse, G.; Grabmaier, B.C. Luminescent Materials, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelber, Germany, 1994; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Hoefdraad, H.E. The charge-transfer absorption band of Eu3+ in oxides. J. Solid State Chem. 1975, 15, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchur, A.K.; Ningthoujam, R.S. Behaviour of electric and magnetic dipole transitions of Eu3+,5D0-7F0 and Eu-O charge transfer band in Li+ co-doped YPO4:Eu3+. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 10859–10868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariselvam, K.; Liu, J. Synthesis and luminescence properties of Eu3+ doped potassium titano telluroborate (KTTB) glasses for red laser applications. J. Lumin. 2021, 230, 117735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrov, L.; Milanova, M.; Yordanova, A.; Iordanova, R.; Nedyalkov, N.; Petrova, P.; Tagiara, N.S.; Palles, D.; Kamitsos, E.I. Synthesis, structure and luminescence properties of Eu3+-doped 50ZnO.40B2O3.5WO3.5Nb2O5 glass. Phys. Chem. Glas. Eur. J. Glass Sci. Technol. B 2023, 64, 101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Yordanova, A., Aleksandrov, L., Milanova, M., Iordanova, R., Petrova, P., Nedyalkov, N. Effect of the addition of WO<sub>3</sub> on the structure and luminescent properties of ZnO-B2O3: Eu3+ glass. Molecules, 2024, 29, 2470.

- Sreena, T. S.; Raj, A. K.; Rao, P. P. Effects of charge transfer band position and intensity on the photoluminescence properties of Ca1.9M2O7: 0.1Eu3+ (M= Nb, Sb and Ta). Solid State Sci. 2022, 123, 106783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. Y.; Jiang, D. G.; Chen, S. W.; Zheng, G. T.; Huang, S. M.; Gu, M.; Zhao, J. T. Eu3+- activated borogermanate scintillating glass with a high Gd2O3 content. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2013, 96, 1483–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, M.; Liu, X.; Lin, J. Luminescence properties of R2MoO6: Eu3+ (R= Gd, Y, La) phosphors prepared by Pechini sol-gel process. J. Mater. Res. 2005, 20, 2676–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walas, M. , Lisowska, M., Lewandowski, T., Becerro, A.I., Łapiński, M., Synak, A., Sadowski, W. and Kościelska, B. From structure to luminescence investigation of oxyfluoride transparent glasses and glass-ceramics doped with Eu3+/Dy3+ ions. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 806, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Shigeo, M. William, Phosphor Handbook. CRC Press, Washington, DC, 1998.

- Dejneka, M.; Snitzer, E.; Riman, R. E. Blue, green and red fluorescence and energy transfer of Eu3+ in fluoride glasses. J. Lumin. 1995, 65, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanova, M.; Aleksandrov, L.; Yordanova, A.; Iordanova, R.; Tagiara, N.S.; Herrmann, A.; Gao, G.; Wondraczek, L.; Kamitsos, E.I. Structural and luminescence behavior of Eu3+ ions in ZnO-B2O3-WO3 glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2023, 600, 122006.

- Narro-García, R. , Desirena, H., López-Luke, T., Guerrero-Contreras, J., Jayasankar, C. K., Quintero-Torres, R., De la Rosa, E. Spectroscopic properties of Eu3+/Nd3+ co-doped phosphate glasses and opaque glass–ceramics. Opt. Mater. 2015, 46, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A., Joshi, C., Rai, S. B. Effect of heat treatment on structural, thermal and optical properties of Eu3+ doped tellurite glass: formation of glass-ceramic and ceramics. Opt. Mater. 2015, 45, 202-208.

- Laia, A. S., Maciel, G. S., Rodrigues Jr, J. J., Dos Santos, M. A., Machado, R., Dantas, N. O., Silva, A.C.A, Rodrigues, R. B., Alencar, M.A. Lithium-boron-aluminum glasses and glass-ceramics doped with Eu3+: A potential optical thermometer for operation over a wide range of temperatures with uniform sensitivity. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 907, 164402. [CrossRef]

- Muniz, R. F., De Ligny, D., Sandrini, M., Zanuto, V. S., Medina, A. N., Rohling, J. H., Guyot, Y. Fluorescence line narrowing and Judd-Ofelt theory analyses of Eu3+-doped low-silica calcium aluminosilicate glass and glass-ceramic. J. Lumin. 2018, 201, 123–128.

- Binnemans, K.; Görller-Walrand, C. Application of the Eu3+ ion for site symmetry determination. J. Rare Earths 1996, 14, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.; Guild, J. The CIE colorimetric standards and their use. Trans. Opt. Soc. 1931, 33, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, T.B. SpectraChroma (Version 1.0.1) [Computer Software]. 2021. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/4906590 (accessed on 7 June 2021).

- Trond, S.S.; Martin, J.S.; Stanavage, J.P.; Smith, A.L. Properties of Some Selected Europium—Activated Red. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1969, 116, 1047–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCamy, C.S. Correlated color temperature as an explicit function of chromaticity coordinates. Color Res. Appl. 1992, 17, 142–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanotto, E. D. Glass Crystallization Research — A 36-Year Retrospective. Part I, Fundamental Studies. Int. J. Appl. Glass Sci., 2013, 4, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J; Kobayashi, M.; Sigimoto, S.; Parker, J. M. Scintillation from Eu2+ in Nanocrystallized Glass. J. Am. Ceram. Soc., 2009, 92, 2019-2021.

- Aleksandrov, L; Iordanova, R.; Dimitriev, Y.; Georgiev, N.; Komatsu, T. Eu3+ doped 1La2O3:2WO3:1B2O3 glass and glass ceramic. Opt. Mater. 2014, 36, 1366-1372.

- DIFFRAC.EVA V.4, User’s Manual, Bruker AXS, Karlsruhe, Germany, 2014.

- TOPAS V4.2: General Profile and Structure Analysis Software for Powder Diffraction Data. - User’s Manual, Bruker AXS, Karlsruhe, Germany, 2009.

| Time | α-Zn3B2O6, a/b/c [Å], volume [Å3] |

β-Zn3B2O6 a/b/c [Å], volume [Å3] |

ZnNb2O6 a/b/c [Å], volume [Å3] |

| 30h | 6.311/8.267/10.035 500.9(2) | 23.885/5.047/8.385 985.0(3) | 14.219/5.706/5.066 411.0(4) |

| 25h | 6.312/8.265/10.035 500.8(2) | 23.885/5.048/8.383 985.1(4) | 14.212/5.708/5.067 411.0(4) |

| 20h | 6.310/8.264/10.031 500.5(3) | 23.873/5.048/8.379 984.1(7) | 14.216/5.701/5.067 410.7(6) |

| 15h | 6.302/8.255/10.023 499.0(4) | 23.833/5.039/8.365 978.7(7) | 14.189/5.692/5.063 408.9(6) |

| 10h | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| 5h | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Glass composition | Relative Luminescent Intensity Ratio, R | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Glass 50ZnO:47B2O3:3Nb2O3:0.5Eu2O3 | 5.16 | Current work+ [5] |

| GC-5h | 5.28 | Current work |

| GC-10h | 5.39 | Current work |

| GC-15h | 5.42 | Current work |

| GC-20h | 5.47 | Current work |

| GC-25h | 5.49 | Current work |

| GC-30h | 5.21 | Current work |

| Glass 50ZnO:(50-x)B2O3: xNb2O5:0.5Eu2O3:, x= 0, 1, 3 and 5 mol% | 4.31-5.16 | [5] |

| Glass 50ZnO:40B2O3:10WO3:xEu2O3 (0≤x≤10) | 4.54÷5.77 | [28] |

| Glass 50ZnO:40B2O3:5WO3:5Nb2O5:xEu2O3 (0≤x≤10) | 5.09÷5.76 | [20] |

| Glass 66P2O5– 10.5Al2O3–3.05BaO–16.5K2CO3–0.7NaF–xEu2O3–0.5Nd2O3–(2.75-x) La2O3 (mol.%), where x = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.5 and 2 | 3.72 |

[29] |

| Glass ceramic 66P2O5– 10.5Al2O3–3.05BaO–16.5K2CO3–0.7NaF–xEu2O3–0.5Nd2O3–(2.75-x) La2O3 (mol.%), where x = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.5 and 2 | 4.72 | |

| Glass 74.0 TeO2+25.0 Li2CO3+1.0 Eu2O3 | 3.70 | [30] |

| Glass ceramic 74.0 TeO2+25.0 Li2CO3+1.0 Eu2O3 | 3.65 | |

| Glass 50Li2O·45B2O3·5Al2O3: 2Eu2O3 | 3.91 | [31] |

| Glass ceramic 50Li2O·45B2O3·5Al2O3: 2Eu2O3 | 4.047 | |

| Glass 7SiO2-47.4CaO-40.5Al2O3-4.1MgO-1Eu2O3 | 4.58 | [32] |

| Glass ceramic 7SiO2-47.4CaO-40.5Al2O3-4.1MgO-1Eu2O3 | 1.97 |

| Glass composition | Chromaticity coordinates (x,y) |

CCT(K) |

| Glass 50ZnO:47B2O3:3Nb2O3:0.5Eu2O3 | 0.656, 0.343 | 2505.78 [5] |

| GC-5h | 0.652, 0.347 | 2350.82 |

| GC-10h | 0.652,0.348 | 2333.75 |

| GC-15h | 0.652, 0.348 | 2333.75 |

| GC-20h | 0.652,0.348 | 2333.75 |

| GC-25h | 0.652,0.348 | 2333.75 |

| GC-30h | 0.651,0.348 | 2324.60 |

| NTSC standard for red light | 0.670,0.330 | |

| Y2O2S:Eu3+ | 0.658, 0.340 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).