Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

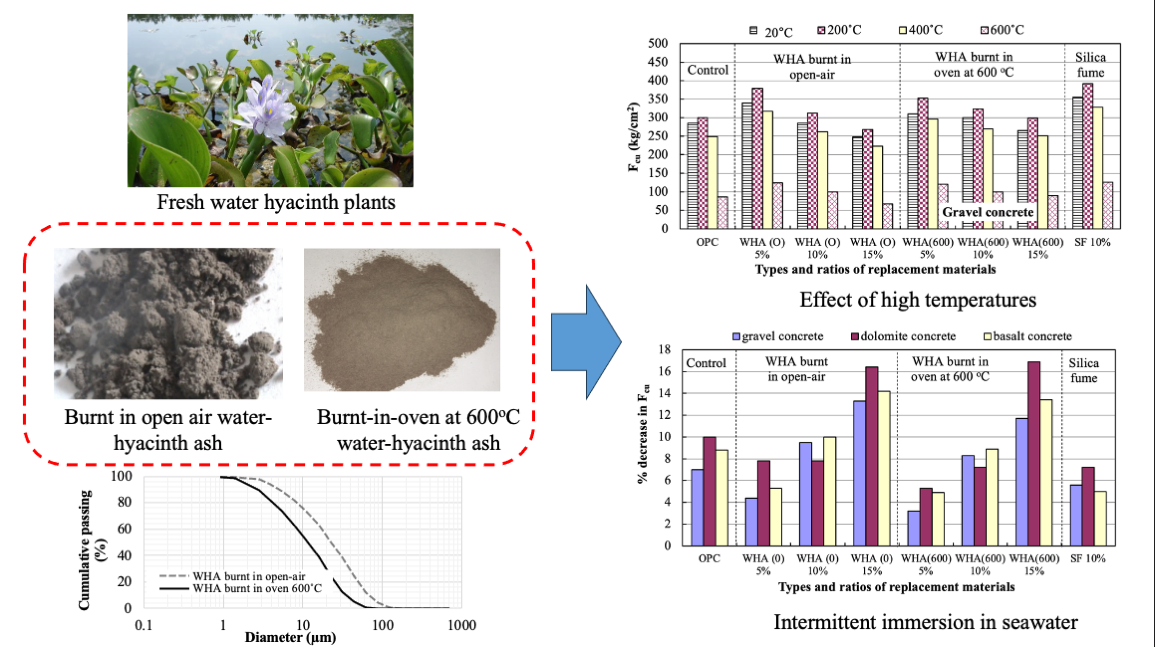

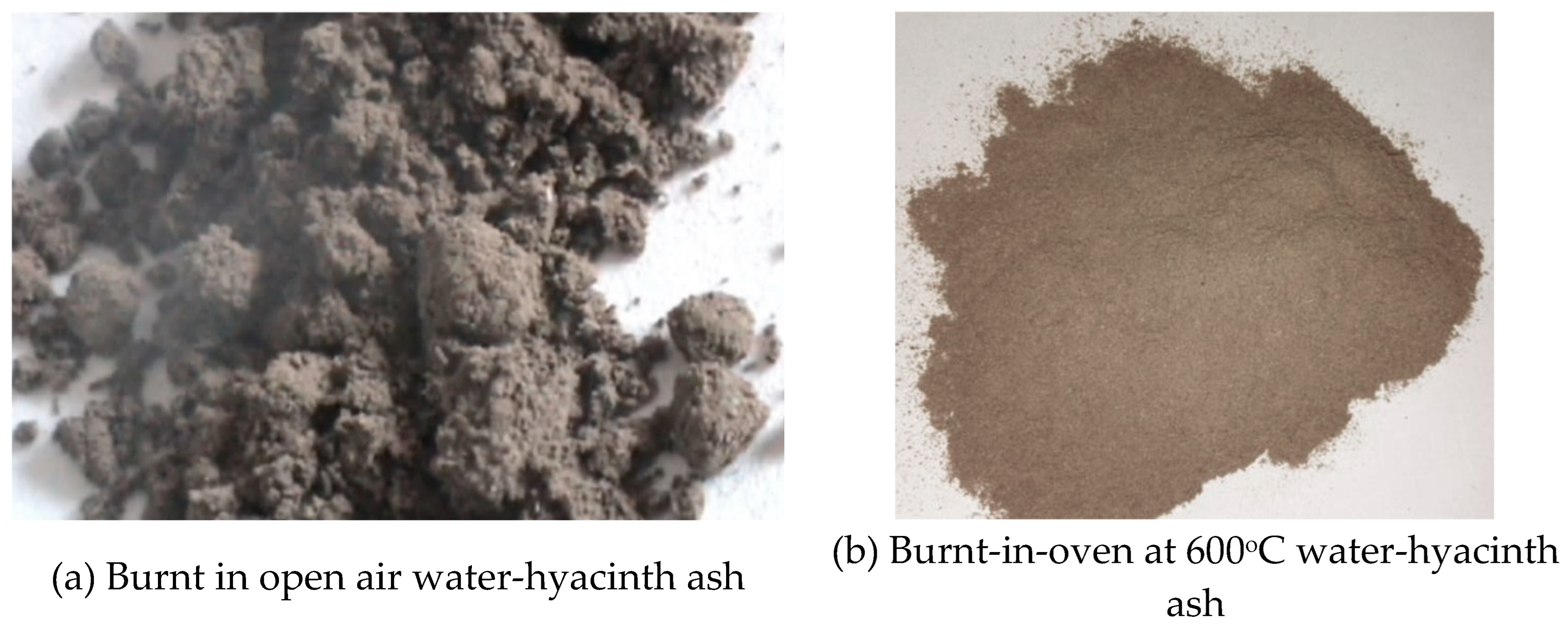

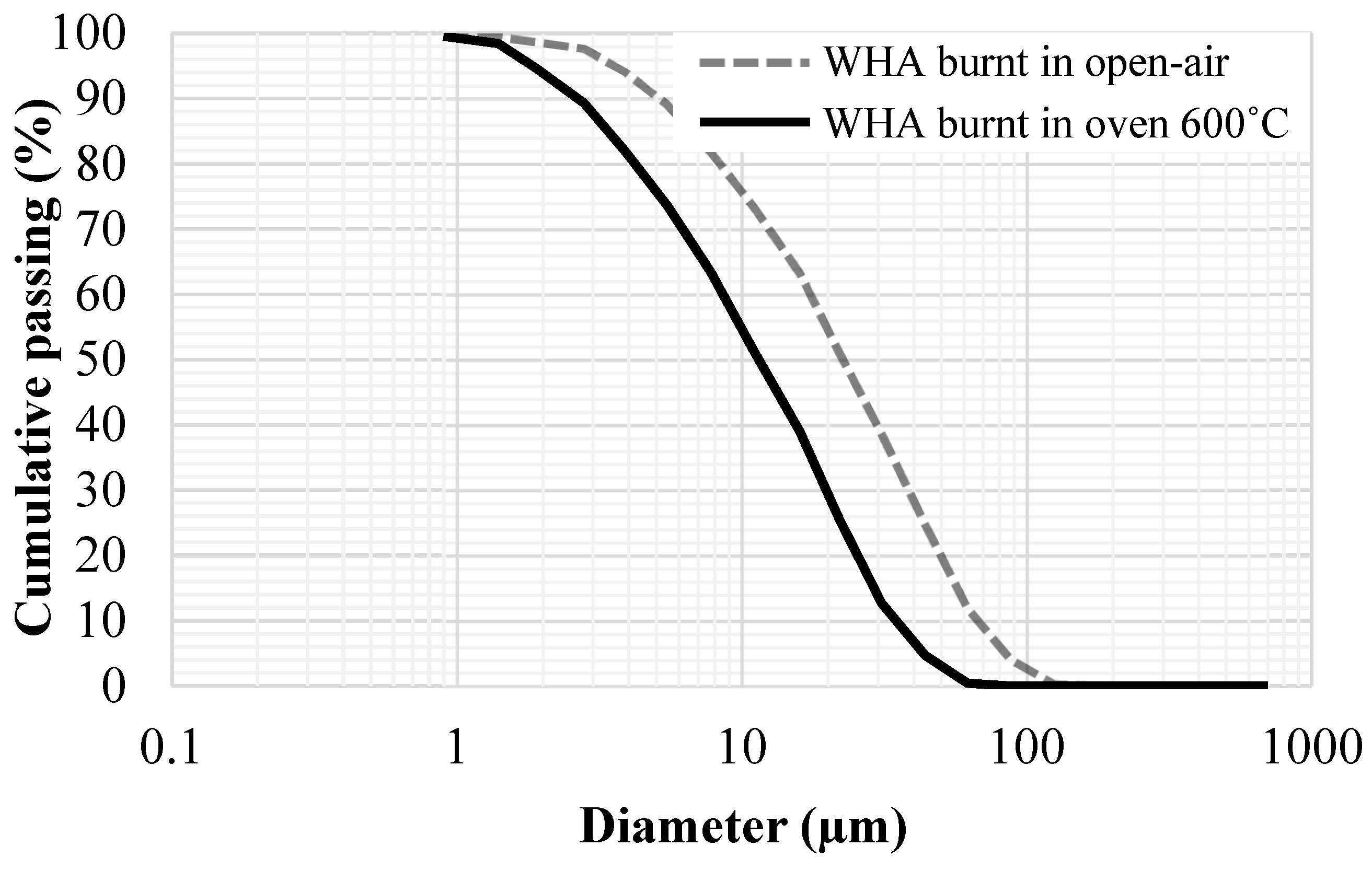

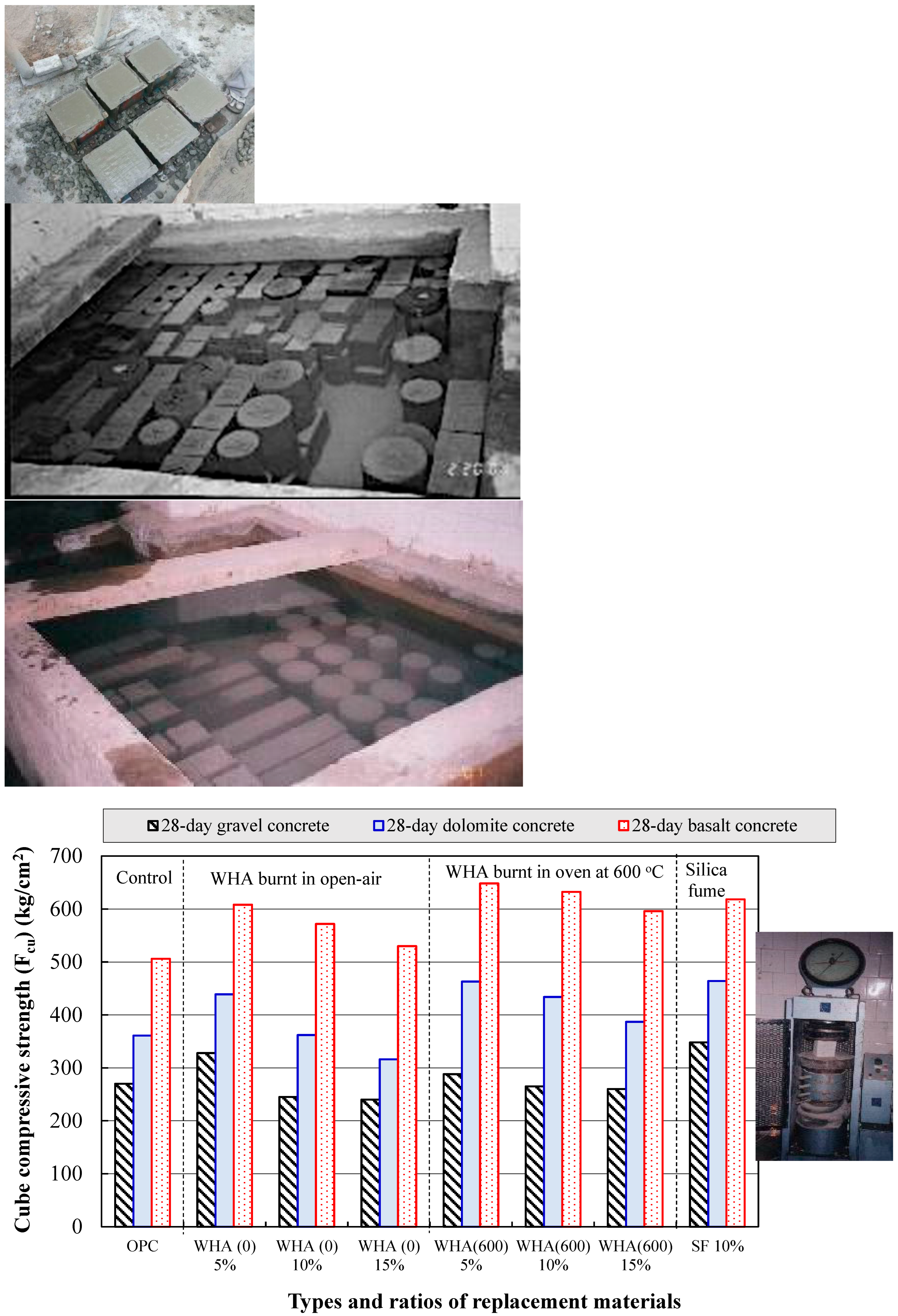

The current research aims at determining the resistance of concrete mixtures containing the ashes resulting from the water-hyacinth plants [1] as a cement replacement to elevated temperature and to seawater. Two types of water-hyacinth ashes (WHA); burnt in open air and burnt in a closed oven at 600°C for 30 minutes were used as partial replacement materials of ordinary portland cement in concrete mixtures with percentages of up to 15% (by weight of cement). The concrete mixtures were designed with three coarse aggregates types; gravel, dolomite, and basalt. To study the resistance to high temperatures, the specimens were exposed to different elevated temperatures of 200, 400, and 600°C and compared to 25°C as a reference. To investigate the resistance to seawater, three curing regimes were followed; curing in laboratory atmosphere (25°C and 50% relative humidity), immersing in seawater during the entire curing period of one month, and subjecting to drying-wet cycles composed of one-day at laboratory atmosphere and one-day in seawater for a total period of one month before testing. The concrete mixes containing WHA were compared with plain concretes and others proportioned with 10% silica fume. The results revealed significant effect of WHA percentages, coarse aggregates types, and curing methods on the concrete strength. With up to 10% cement replacement with WHA, there was no reduction in strength relative to the reference. The optimal replacement value was around 5%.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Testing Program

2.2. Materials

2.3. Mixture Proportions, Mixing Sequence, Samples Preparation, and Curing Conditions

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Fresh Concrete Properties

3.1.1. Workability

3.1.2. Unit Weight

3.2. Hardened Concrete Results

3.2.1. Cubes Compressive Strength (Fcu)

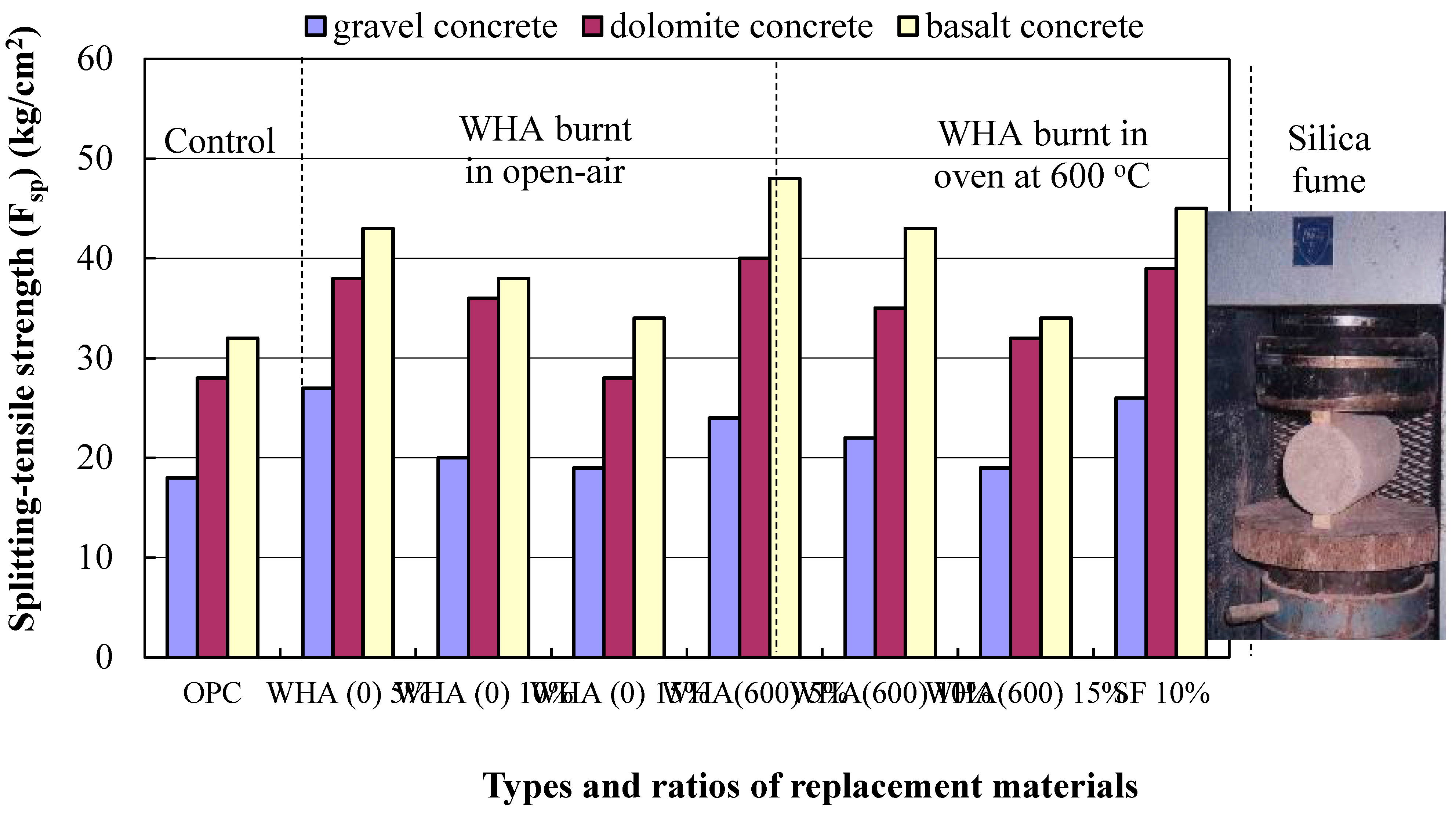

3.2.2. Splitting-Tensile Strength (Fsp)

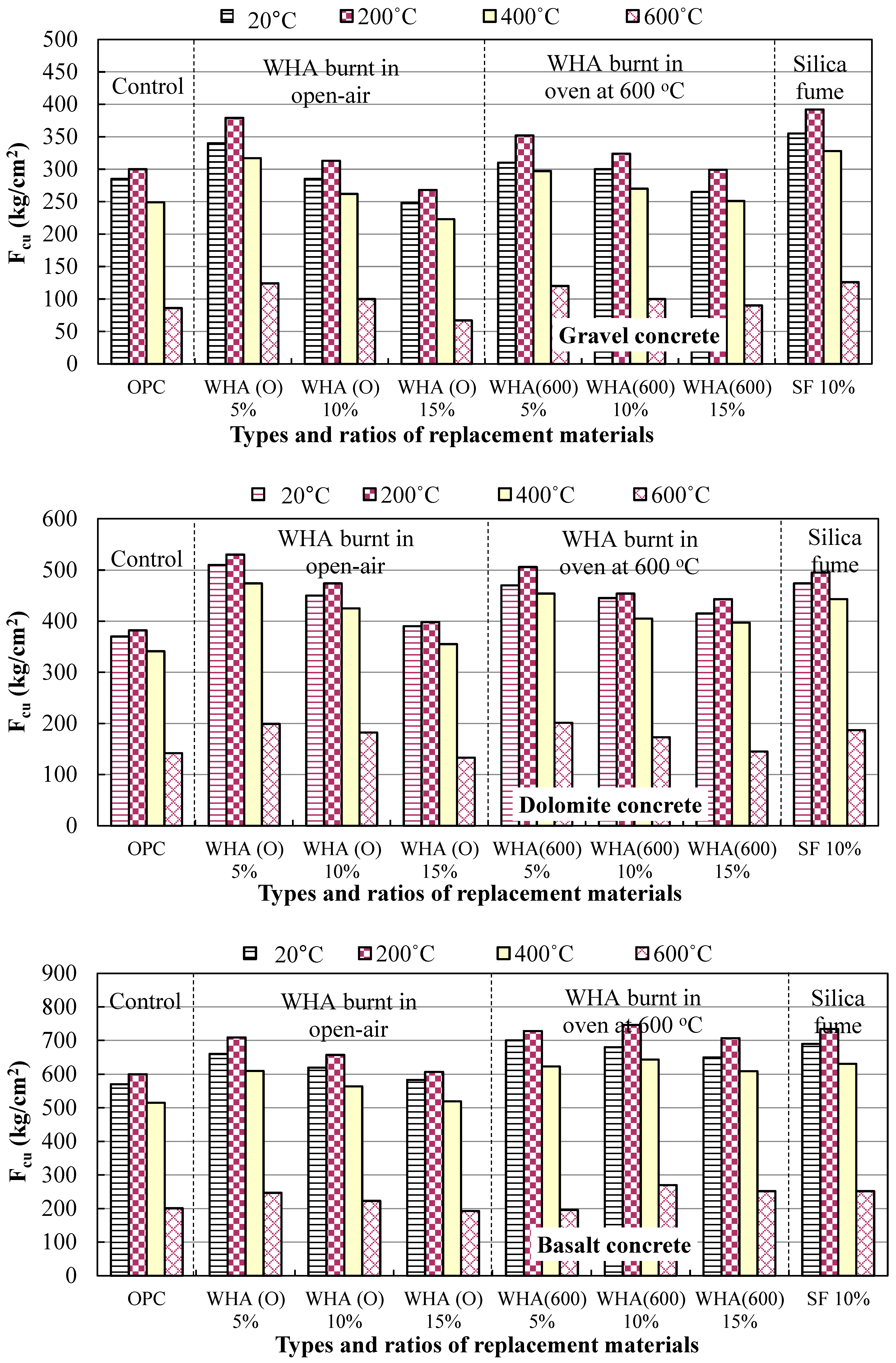

3.3. Resistance to High Temperatures

3.4. Resistance to Seawater

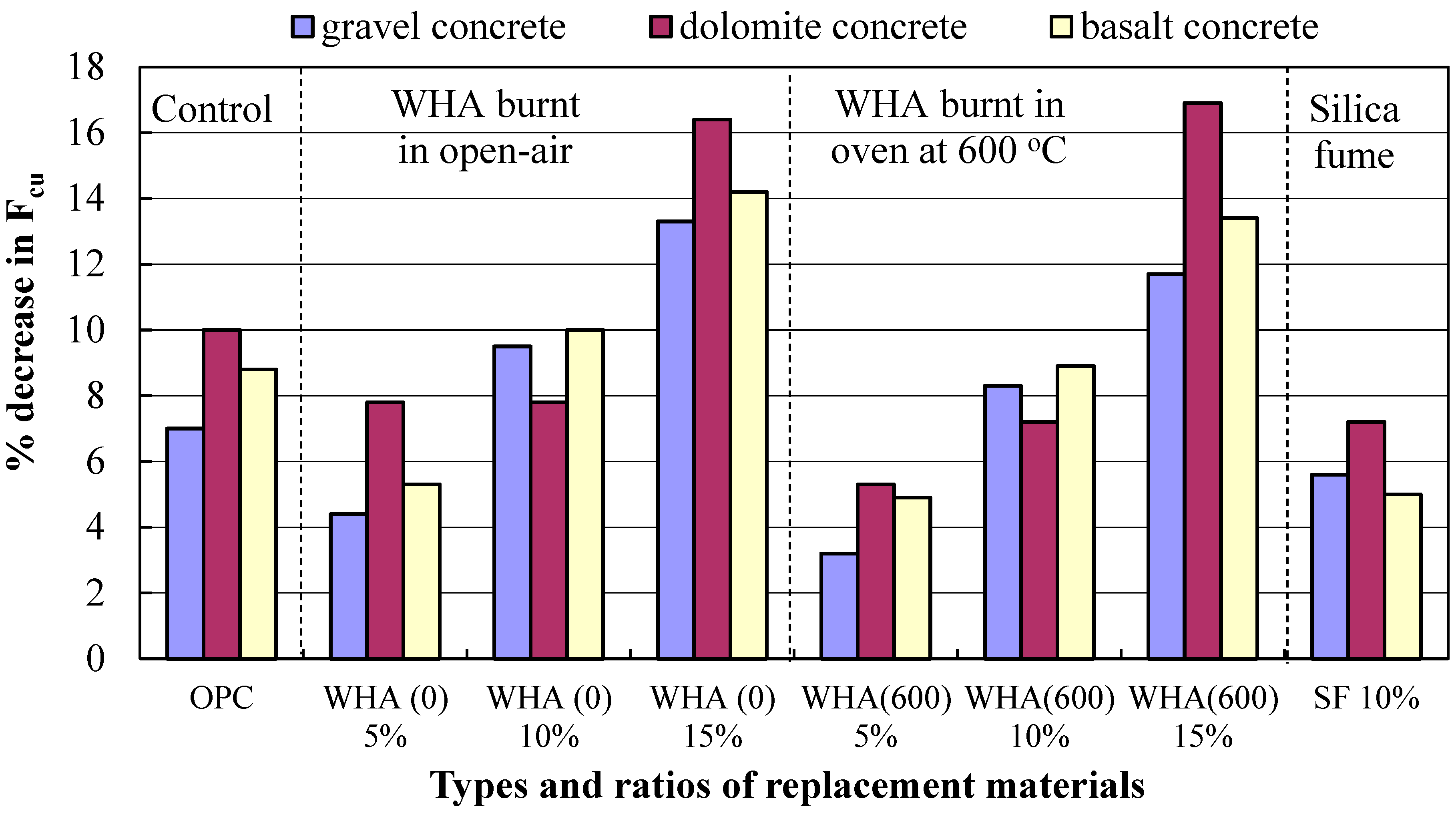

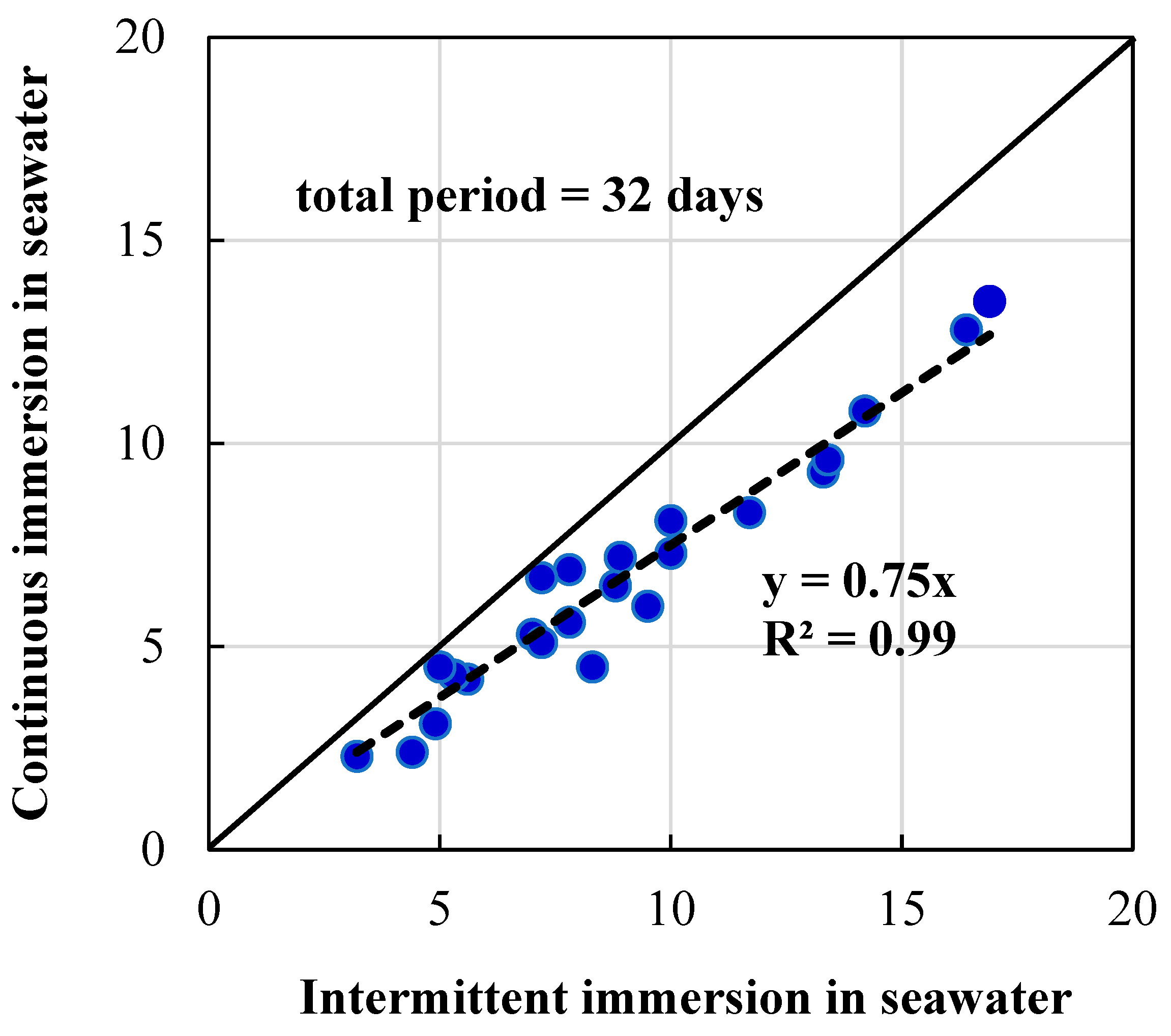

3.4.1. Effect of Continuous Immersion of Concrete in Seawater

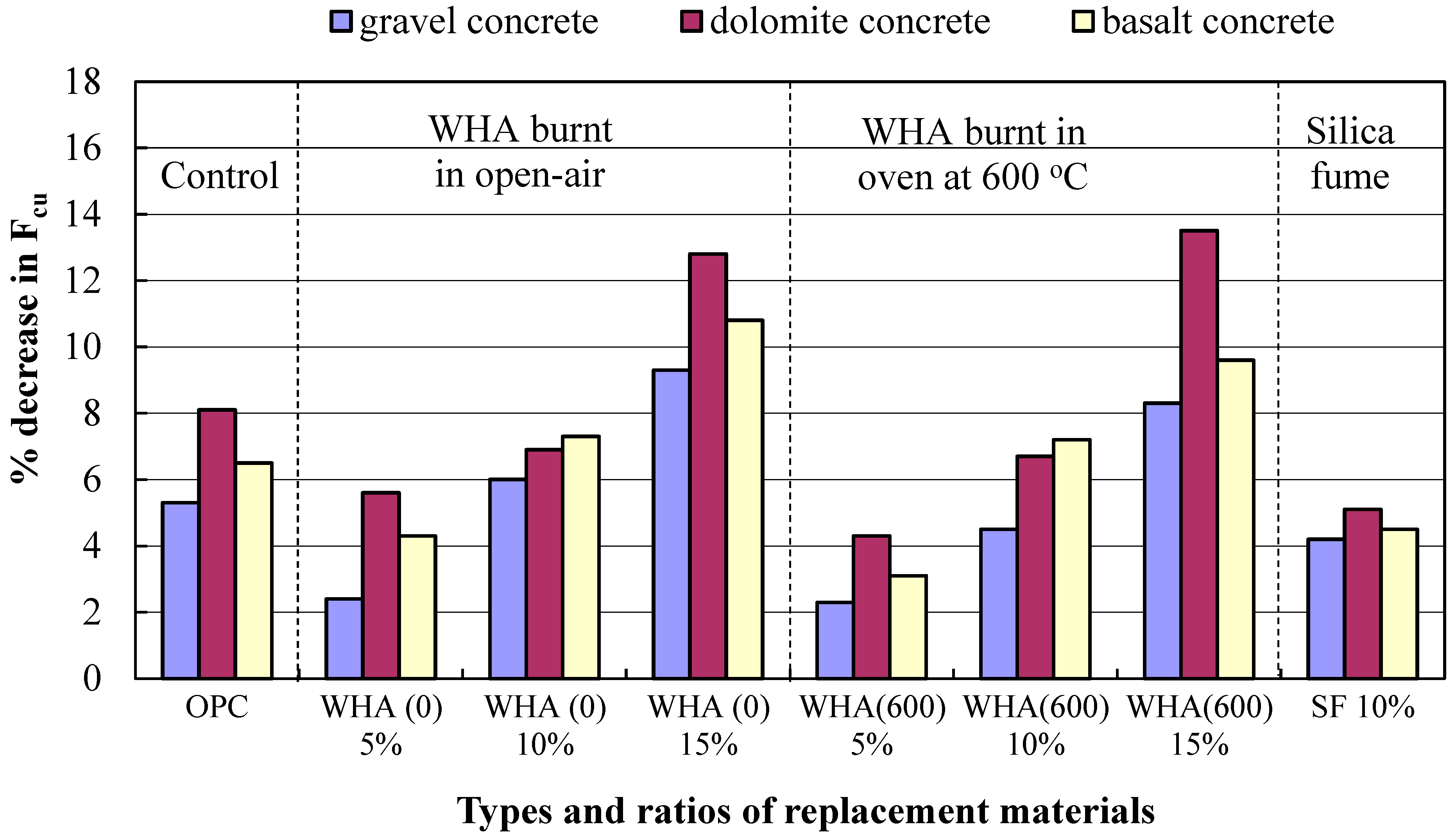

3.4.2. Effects of Intermittent Immersion of Concrete in Seawater

4. Conclusions

- During the manufacture of water-hyacinth ash (WHA), burning the dried water-hyacinth plants in closed ovens produces ash with no effect on environment and with high silica content than burning in open air.

- The use of WHA as a cement replacement material can provide distinguished increase to concrete strength, and the resistance of elevated temperatures and seawater.

- The addition of WHA to ordinary concrete leads to the consumption of Ca(OH) obtained during cement hydration and forming more C-S-H of stronger binding forces and a sufficient thermal stability, resulting in a concrete with densified microstructure and of lower porosity and permeability. Concrete made with 5% to 10% WHA possess the higher compressive strength compared to reference, with more particular attention when exposed to thermal treatment at elevated temperatures.

- Deterioration of concrete exposed to seawater is mainly due to chemical action (change in composition of cement by chlorides and sulfates present in seawater). Selecting suitable cementitious materials with pozzolanic-based effects such as WHA can ensure densified and impermeable concrete product with higher resistance to seawater attack.

- WHA at a 5% replacement ratio to cement is the optimum, leading to a distinguished increase in concrete strength compared to the control due to the pozzolanic activity, filling capacity, and enhancing the transition zones between cement paste and aggregate. The 10% WHA replacement ratio can also result in concrete with performance better than the reference. However, the 15% cannot contribute to strength improvement compared to the control.

- Using water hyacinth as cement replacement material in concrete participates in keeping the environment clean, while reducing natural resources of cement manufacture.

References

- Water Canal Maintenance Research Institute “A guide to water weeds and ways to limit their spread”, December 1999.

- El-Enany AE, Mazen AMA “Isolation of Cd-binding protein of water hyacinth (E. Crassipes) grown in Nile river water”, Water, Air, and Soil pollution, 1996; 87(1-4):357-362. [CrossRef]

- Omran AF, Soliman NA, Kamal MM, Shaheen YB, Osman MAE “Feasibility of using water-hyacinth ash (WHA) as an alternative supplementary cementitious material” Magazine of concrete research, submitted and pending decision; 44 p.

- Krishnan S, MurugeshV “Experimental study on strength of water hyacinth ash as partial replacement of cement in concrete”, International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, March-2018;9(3):93-96. [CrossRef]

- Matte V, Moranville M, Adenot F, Riche C, Torrenti JM “Simulated microstructure and transport properties of ultra-high-performance cement-based materials” Journal of Cement and Concrete Research, 2000;30(12):1947-1954. [CrossRef]

- Malhotra VM “Fly ash, slag, silica fume, and rice husk ash in concrete a review”, Magazine of Concrete International, April 1993;23-28.

- Bouzoubaa N, Min-Hong Zhang VM, Malhotra VM, Golden DM “Blended fly ash cement – a review” ACI Materials Journal, 1999;641-650.

- Mehta PK, “Pozzolanic and cementitious by–products in concrete: another look”, ACI SP-114, 1989;1-43.

- Mehta PK “Pozzolanic and cementitious by-products as mineral admixtures for concrete – a critical review”, ACI SP-79, 1983;1-46.

- Cook DJ, Suwanvitaya P “Rice husk ash based cements - a state-of-the-art review”, Proceedings of the ESCAP/RCTT, 3rd Workshop on Rice – Husk Ash Cement, New Delhi, India, 1981.

- Saad M, Abo-El-Enein SA, Hanna GB, Kotkata MF “Effect of temperature on physical and mechanical properties of concrete containing silica fume,” Cement and Concrete Research, 1996; 26(5); 669-675. [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran V “Concrete science”, Heyden & Sons Ltd., London, 1981.

- Makhlouf AAAH, “Application of water hyacinth ash as a partial replacement for cement”, PhD thesis, Cairo University, Egypt, 2002.

- Abdel Hay AS, Fawzy YA“Impact of water hyacinth on properties of concrete made with various gravel to dolomite ratios,” Proc. of the 3rd Intl. Conf. Advances in Civil, Structural and Mechanical Engineering-CSM 2015, Institute of Research Engineers and Doctors, USA, ISBN: 978-1 -63248-062-0. 2015;76-80. [CrossRef]

- Piasta J, Sawicz Z, Rudzinski L “Changes in the structure of hardened cement paste due to high temperature,” Journal of Materials and Structure, 1984;100; 291. [CrossRef]

- Detwiler RJ., Mehta PK “Chemical and physical effect of silica fume on the mechanical behavior of concrete,” ACI Materials Journal, 86(6);609-614. [CrossRef]

- Mather B “Effects of sea water on concrete”, Miscellaneous paper, 1964; (No. 6-690).

- Locher FW, Pisters H "Beurteilung betonangreifender Wasser" Zement-Kalk-Gips, April 1964;(No. 4);129-136.

- Lea FM “The Chemistry of Cement and Concrete”, St. Martin's Press,New York, N.Y. 1956.

- ASTM C845 “Standard Specification for Expansive Hydraulic Cement”, Annual book of ASTM standards, West Conshohocken, PA: American Society for Testing Materials, 2012. 3 pp.

| Group | Mix no. | Mix proportions (kg/m³) | w/cm | CA/FA | Rep/C | ||||||

| C | W | FA | CA | Replacement (Rep) | |||||||

| WHA(0) | WHA(600) | SF | |||||||||

| Gravel concrete | OPC | 300 | 150 | 638 | 1276 | — | — | — | 0.5 | 2 | — |

| WHA(0)5% | 285 | 150 | 637 | 1274 | 15 | — | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.05 | |

| WHA(0)10% | 270 | 150 | 636 | 1272 | 30 | — | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.10 | |

| WHA(0)15% | 255 | 150 | 635 | 1270 | 45 | — | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.15 | |

| WHA(600)5% | 285 | 150 | 637 | 1274 | — | 15 | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.05 | |

| WHA(600)10% | 270 | 150 | 637 | 1273 | — | 30 | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.10 | |

| WHA(600)15% | 255 | 150 | 635 | 1271 | — | 45 | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.15 | |

| SF 10% | 270 | 150 | 635 | 1269 | — | — | 30 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.10 | |

| Dolomite concrete | OPC | 300 | 150 | 681 | 1362 | — | — | — | 0.5 | 2 | — |

| WHA(0)5% | 285 | 150 | 680 | 1360 | 15 | — | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.05 | |

| WHA(0)10% | 270 | 150 | 679 | 1358 | 30 | — | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.10 | |

| WHA(0)15% | 255 | 150 | 678 | 1356 | 45 | — | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.15 | |

| WHA(600)5% | 285 | 150 | 680 | 1360 | — | 15 | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.05 | |

| WHA(600)10% | 270 | 150 | 679 | 1359 | — | 30 | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.10 | |

| WHA(600)15% | 255 | 150 | 679 | 1357 | — | 45 | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.15 | |

| SF 10% | 270 | 150 | 677 | 1355 | — | — | 30 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.10 | |

| Basalt concrete | OPC | 300 | 150 | 692 | 1385 | — | — | — | 0.5 | 2 | — |

| WHA(0)5% | 285 | 150 | 691 | 1382 | 15 | — | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.05 | |

| WHA(0)10% | 270 | 150 | 690 | 1380 | 30 | — | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.10 | |

| WHA(0)15% | 255 | 150 | 689 | 1378 | 45 | — | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.15 | |

| WHA(600)5% | 285 | 150 | 692 | 1383 | — | 15 | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.05 | |

| WHA(600)10% | 270 | 150 | 691 | 1381 | — | 30 | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.10 | |

| WHA(600)15% | 255 | 150 | 690 | 1380 | — | 45 | — | 0.5 | 2 | 0.15 | |

| SF 10% | 270 | 150 | 689 | 1377 | — | — | 30 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.10 | |

| CONSTITUENT | SYMBOL | PERCENTAGE % | CONCENTRATION (MG/L) |

| Sodium | Na++ | 30.61 | 124000 |

| Magnesium | Mg++ | 3.69 | 1500 |

| Calcium | Ca++ | 1.16 | 470 |

| Potassium | K+ | 1.10 | 445 |

| Strontium | Si ++ | 0.03 | 12 |

| Chloride | Cl - | 55.04 | 21270 |

| Sulphate | SO4 - - | 7.68 | 2596 |

| Bicarbonate | HCO3 - | 0.41 | 165 |

| Bromine | Br - | 0.19 | 77 |

| Constituent | Cement | Silica fume | Water-hyacinth ash (WHA) | ||

| Burnt in air | Burnt in 600°C | ||||

| Chemical composition | SiO2 | 19.49 | 93.00 | 33.9 | 34.5 |

| Ti2O3 | — | — | 0.75 | 0.78 | |

| Al2O3 | 4.70 | 0.5 | 6.77 | 6.95 | |

| Fe2O3 | 3.28 | 1.5 | 5.77 | 6.02 | |

| SO3 | 3.4 | 0.2 | — | — | |

| MgO | 2.40 | 0.5 | 5.40 | 5.93 | |

| CaO | 62.8 | 0.2 | 10.08 | 11.46 | |

| Na2O | 0.38 | 0.5 | 1.26 | 1.41 | |

| K2O | 0.95 | 0.5 | 9.83 | 10.98 | |

| H2O | — | 0.6 | — | — | |

| MnO | — | — | 0.66 | 0.73 | |

| P2O5 | — | — | 1.04 | 1.13 | |

| Cl‾ | — | — | 3.82 | 4.02 | |

| SO4‾ ‾ | — | — | 2.37 | 3.74 | |

| Loss On Ignition (LOI) | 2.4 | 1.5 | 17.93 | 11.91 | |

| total | 99.8 | 99.60 | 99.54 | ||

| Physical properties | Blaine surface area (m2/kg) | 300 | 17000 | — | — |

| Bulk density (kg/m3) | — | 280 | — | — | |

| Specific gravity | 3.13 | 2.20 | 2.52 | 2.65 | |

| Color | — | Light gray | Dark gray | Light brown | |

| Property | Fine aggregate (sand) (FA) | Coarse aggregates (CA) | ||

| Gravel | Dolomite | Basalt | ||

| Specific gravity (SSD) | 2.58 | 2.52 | 2.78 | 2.85 |

| Volume weight (t/m³) | 1.710 | 1.630 | 1.615 | 1.682 |

| Void ratio (%) | 33.72 | 35.2 | 41.9 | 41.0 |

| Aggregate crushing value (%) | — | 15 | 19 | 12 |

| Fineness modulus | 2.71 | 7.55 | 7.45 | 7.60 |

| Clay, silt, and fine dust (% by weight) | 2.13 | — | — | — |

| Chloride (% by weight) | 0.031 | 0.027 | 0.032 | 0.023 |

| Sulfate (% by weight) | — | 0.130 | 0.190 | 0.160 |

| Materials | Slump (mm) | Unit weight (kg/m³) | ||||

| Gravel | Dolomite | Basalt | Gravel | Dolomite | Basalt | |

| OPC | 105 | 100 | 135 | 2364 | 2493 | 2527 |

| WHA(0)5% | 95 | 92 | 123 | 2361 | 2490 | 2524 |

| WHA(0)10% | 87 | 77 | 110 | 2358 | 2487 | 2521 |

| WHA(0)15% | 80 | 67 | 97 | 2355 | 2483 | 2517 |

| WHA(600)5% | 92 | 85 | 120 | 2362 | 2490 | 2525 |

| WHA(600)10% | 85 | 70 | 105 | 2359 | 2488 | 2522 |

| WHA(600)15% | 75 | 60 | 90 | 2357 | 2486 | 2520 |

| SF 10% | 55 | 40 | 60 | 2354 | 2482 | 2516 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).