1. Introduction

When producing cement-based materials, not only good mechanical and durability characteristics must be considered, but also environmental friendliness, ecological impact, and socioeconomic benefits must be considered [

1,

21]. Using alternative supplementary cementitious materials (ASCMs) for partial replacement of cement in concrete would reduce cement production, which is costly, consumes natural resources, and negatively affects environment through CO

2 emissions and increasing greenhouse effect [

2]. From economic, technological, and ecological points of view, cement replacement materials have undisputed roles in the future of the construction industry. Small amounts of inert fillers have always been acceptable as cement replacements, but if the fillers have pozzolanic properties, they impart not only technical advantages to the resulting concrete, but also enable larger quantities of cement replacement to be achieved. Many of these mineral admixtures are industrial by-products like silica fume, slag, and fly ash. Other manufactured pozzolans have a vegetable origin like rice-husk ash, rice-straw ash. Extensive research has been carried out in this respect [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

22,

23]. They dealt with the production and utilization of pozzolanic and cementitious by-products in many countries around the world.

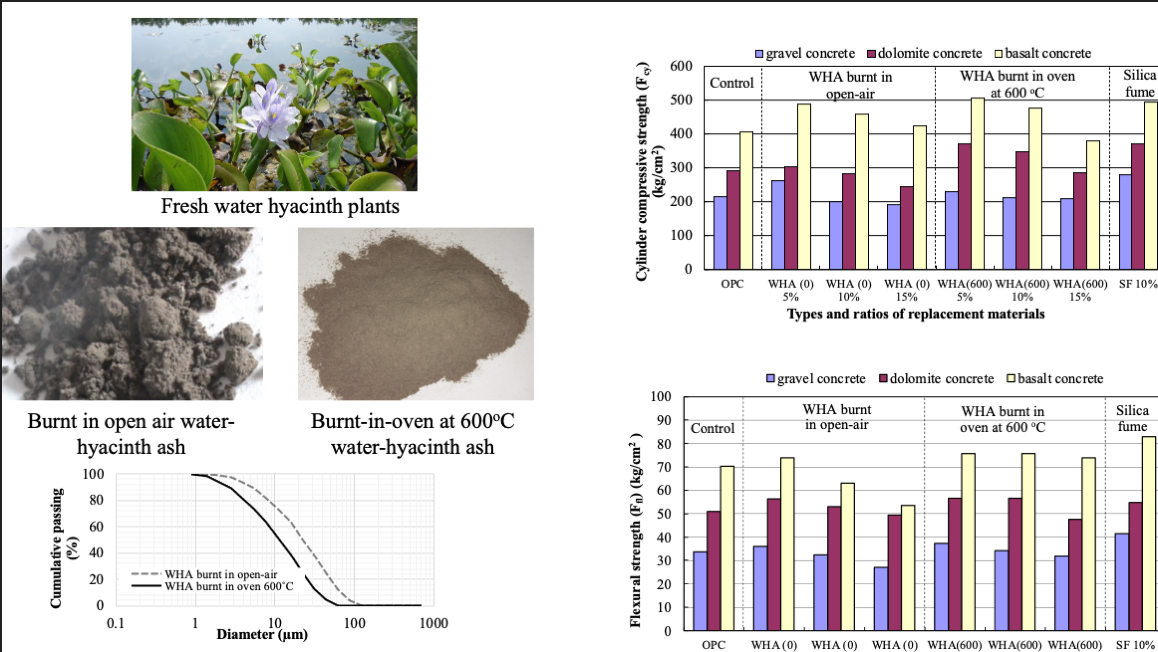

Water hyacinth plants (

Figure 1) are native to Latin America but they have been widely spread throughout the world. They were introduced to the USA in the 19

th century in the state of Louisiana. Shortly, thereafter, water hyacinth made their way to the central states of America and other warm parts of the world. Water hyacinth is exceptionally productive, and it multiplies rapidly, it can double its number in two weeks [

8]. Mass of freshwater hyacinth planted acre is 153 tones, among which, 27.7% is a dry material. Water hyacinth plants curtail river transports, damage canal walls, increase water evaporation losses, decrease amount of oxygen in water, causes organic pollution in slow moving stream and canals. In 1965, water hyacinth plants covered all watercourses of drains and canals in lower and middle Egypt, so that water level increased in main drainage and came back to branch drainage and to agriculture lands [

9]. In 1902, Zarnikhet sodium compound succeeded to destroy the water hyacinth but it was a very harmful compound to humans and animals and was prohibited since 1937. In 1988, carbolic and sulpheric acids were sprayed over the water hyacinth to fire it in USA with less success [

10]. In Egypt, the ministry of irrigation and water resources used to collect the plant by dredges and burn it on the adjacent berms of the water canals [

10]. This method participates significantly to air pollution. In recent years, the researches have been interested in the nutritional values of water-hyacinth plants for animal feeds. On the other hand, the nature of water hyacinth plants opens other applicable uses as reinforcing agents in paper industry [

11]. However, the utilization of water hyacinth plants as filler or reinforcing agents in cement mortar or concretes are still very limited [

12,

13]. The study carried out by [

14] indicated that the dry water hyacinth plants have many heavy metals with significant contents that are summarized in

Table 1. The values indicated in the table are average values obtained from the complete dried plants, meaning that the root, stem, and leaves. Under controlled burning and sufficiently ground, the water hyacinth plant can be transformed into ash (WHA) rich in the metals contents that can be used as cement replacement material in concrete. The current research reports on the feasibility of using the WHA as partial replacement of cement in paste, mortar, and concrete mixtures.

2. Research Significance

Currently, there is a critical need for new building materials for the new infrastructures construction and for repair and enhancing the performance of existing structures. The required materials should be highly energy efficient, environmentally friendly, sustainable, affordable, cost effective, and resilient. Using alternative supplementary cementitious materials (ASCMs) would reduce cement production, which consumes natural resources, and negatively affects environment through CO2 emission and increasing greenhouse effect. Water hyacinth plants curtail river transports, damage canal walls, increase water evaporation losses, decrease amount of oxygen in water, causes organic pollution in slow moving stream and canals. The most common method to overcome the water-hyacinth plants related problems is to mechanically collect the plants from the watercourses, then dry and burn it (turning the fresh plants to an ash), however this method participates significantly to air pollution. The current research provides an ecological solution to consume the waste-water-hyacinth ash (WHA) by using it as a partial cement replacement. The research shows experimentally the efficiency of using the WHA as a partial cement replacement in paste, mortar, and concrete mixtures.

3. Experimental Program

3.1. Testing program

To evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of using WHA as an ASCM in cementitious mixtures, eight paste, eight mortar, and 24 concrete mixtures were prepared and tested. The main investigated parameters and their ranges are given in

Table 2. Ordinary Portland cement (OPC), two types of WHA (burnt in open air and burnt in closed oven at 600˚C for 30 minutes), and silica fume (SF) were considered as binder materials. Three replacement ratios (5%, 10%, 15%) of each the two WHA types, and one replacement ratio by SF (10%) were considered in the investigation. The 10% SF was selected as a reference according to [

14]. This generated eight variables including, (1) pure OPC as control mix; (2), (3), (4) with 5%, 10%, 15% WHA burnt in open air which were symbolled by WHA

(0)5%, WHA

(0)10%, WHA

(0)15%, respectively; (5), (6), (7) with 5% , 10%, 15% WHA burnt in closed oven at 600˚C for 30 minutes, which were symbolled by WHA

(600)5%, WHA

(600)10%, WHA

(600)15%, respectively; (8) with 10% SF. In addition to those parameters, three coarse aggregate (CA) types (gravel, dolomite, and basalt) that are locally available in Egypt were also incorporated in the concrete mixtures.

The effect of WHA replacement on the setting time of paste mixtures was evaluated using Vicat apparatus. The pozzolanic activity of the WHA was assessed using a method depending on the variation of electrical conductivity of a solution containing the tested WHA [

15,

16]. The pozzolanic activity indices were measured also using mortar mixtures incorporating various replacement levels of the WHA at testing ages of 3, 7, and 28 days. The 24 concrete mixtures were tested at the fresh state (slump and unit weight) and at the hardened state by measuring the mechanical properties: cube compressive strength (F

cu), indirect tensile-splitting strength (F

sp), flexural strength (F

fl), modulus of elasticity (E

c), and the stress-strain development.

3.2. Materials

An OPC confronting the ASTM Type GU cement was used in all the mixtures. The SF obtained from the free silicon company in Cairo Egypt was used in some of the mixtures with 10% replacement level. It was delivered in a powder form with a light-gray color. The chemical composition and physical properties of cement and SF, as provided by the manufacturer, are given in

Table 3.

Three types of CA with maximum-nominal size of 25 mm were incorporated in the mixtures; (a) natural gravel, (b) crushed dolomite with irregular and angular shapes, (c) crushed particles of basalt with gray to black color. Natural siliceous sand was used as fine aggregate (FA). The physical and mechanical properties of the FA and CA are given in

Table 4. The grading curves of the combined aggregates were in good compliance with the limits of the British Standard code requirements.

The water hyacinth plants collected from the river Nile at Delta Barrages area in Egypt were used to obtain the WHA used in the present investigation. The effect of burning process (temperature and condition) on the properties of the resulting ash was investigated, because the increase in the burning temperature makes the ash more reactive via breaking the crystalline structure (if any). The process for producing the WHA can be summarized as follows:

The water hyacinth plants were harvested from water bodies (initially contains about 95% water) and laid to dry up in open air for 2-3 weeks at a temperature of about 35-40˚C and a humidity of less than 50% (

Figure 2a, b). The dry plants had less than 10% water and can be self-ignited and make a fire.

The dry plants were burnt (by making a fire) in different conditions either burning in open air for 60 minutes (referred to as WHA(0)) or in a closed oven at 600˚C for 30 min (referred to as WHA(600)).

The resultant ashes were cooled down, then stored in a dry condition.

The ashes were ground using Los–Angeles machine (with 1500 rpm), then the fine ashes passed the # 200 standard sieve were collected. The WHA

(0) is shown in

Figure 2c, where the WHA

(600) is presented in

Figure 2d.

The physical and chemical characterization of the two WHA types were measured and the results are described in

Table 3. The elements expressing the potential of pozzolanic activity (SiO

2, Al

2O

3, and Fe

2O

3) represent approximately 50% of the ash. This value corresponds to that found in some of fly ash types [

16]. The large loss on ignition (LOI) values indicate existing of high quantity of organic materials in the resultant WHA. The percentages of WHA mass to the original dry plants that can be obtained from the open-air burning was found slightly greater (27.65%) than that obtained from the oven burning condition (25.85%).

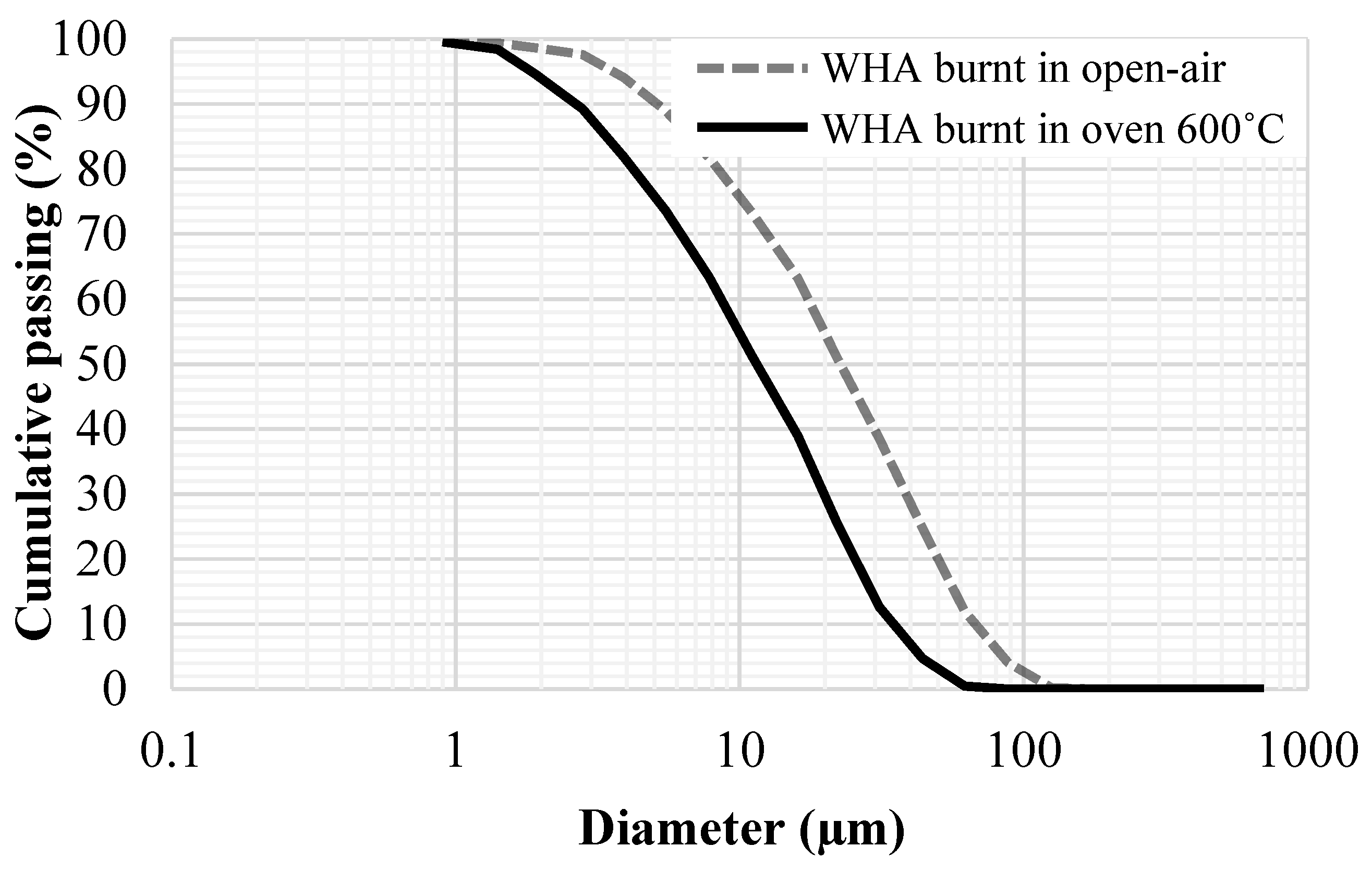

After grinding process, laser-diffraction analysis was carried out on the WHA to determine the particle-size distribution (PSD), and the resultant PSDs are presented in

Figure 3. The results indicate that the WHA

(0) is coarser than the WHA

(600). The respective particle size ranges from 1 to 125 μm for the WHA

(0) with mean-particle diameters (

d50) of 23 µm, and ranges from 1 to 62 μm for the WHA

(600) with a

d50 of 12 µm.

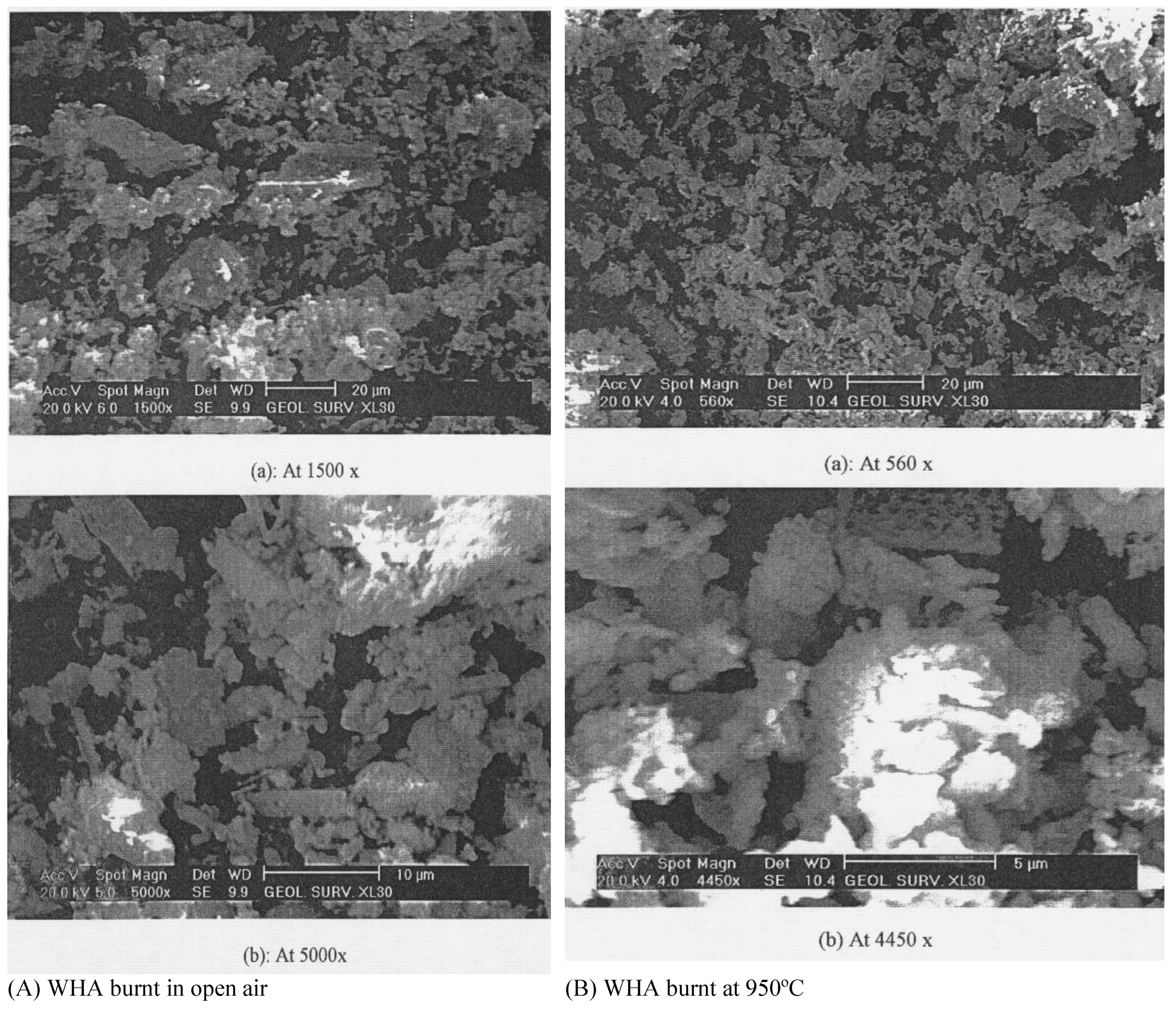

The scanning-electron microscope (SEM) photography using SEM model Philips XL30 attached with EDX unit was carried out on the WHA powders, and the results are shown in

Figure 4. The WHA is porous and mainly contained angular particles of irregular shape and rough textures, where there are few spherical particles with smooth surfaces similar to the OPC particles [

18], as illustrated in the micrograph

Figure 4.

3.3. Mixture proportions, mixing sequence, samples preparation, and curing conditions

All the materials used to make paste, mortar, or concrete mixtures were kept at 23 °C for 24 hours prior mixing.

Paste mixtures – The water content for making the paste mixtures was determined based on the necessary water content for obtaining the normal consistency level. We started with the water content for obtaining the normal consistency level of the paste mixture containing only OPC (based on the manufacture data sheet), and then kept the same water-to-cementitious materials ratio (w/cm) for the other paste mixtures containing blended cement and WHA or SF.

Mortar mixtures – The mixture proportions for the mortars were cement+replacement : sand : water of 1 : 3 : 0.4. The batching of mortar consisted of homogenizing cement and sand with a trowel for 1.0 minute, and then the water was added and mixed for additional 3.0 to 4.0 minutes. Immediately after mixing, the mortar is filled into a 7.06-cm cube molds of a 50-cm² surface area. The molds were compacted using vibrating table according to the Egyptian Standard Specification No. 2421. Mortar samples were moist cured at 23ºC until the day of testing at 3, 7, and 28 days.

Concrete mixtures – All concrete mixtures were designed based on the dry condition of aggregates using the absolute volume method. The cementitious materials were; 300 kg/m

3 of OPC, OPC blended with 5%, 10%, 15% WHA

(0) (by weight), OPC blended with 5%, 10%, 15% WHA

(600) (by weight), and OPC blended with 10% SF (by weight). The

w/cm was set at 0.50, without any superplasticizer addition. The ratio between the CA and FA was 2.0. The detailed concrete mix designs are given in

Table 5.

In order to obtain a uniform concrete mix, mixing was performed using an open pan mixer of 50-L capacity at 20-rpm speed. The CA and FA were first charged in a mixer and homogenized for 1.0 minute, then cement (mixed with replacement materials; WHA or SF) was added and mixed for another 1.0 minute. The mixing water was finally added followed by a final mixing period of 3.0 minutes. At the end of mixing, the slump and unit weight for each concrete were measured.

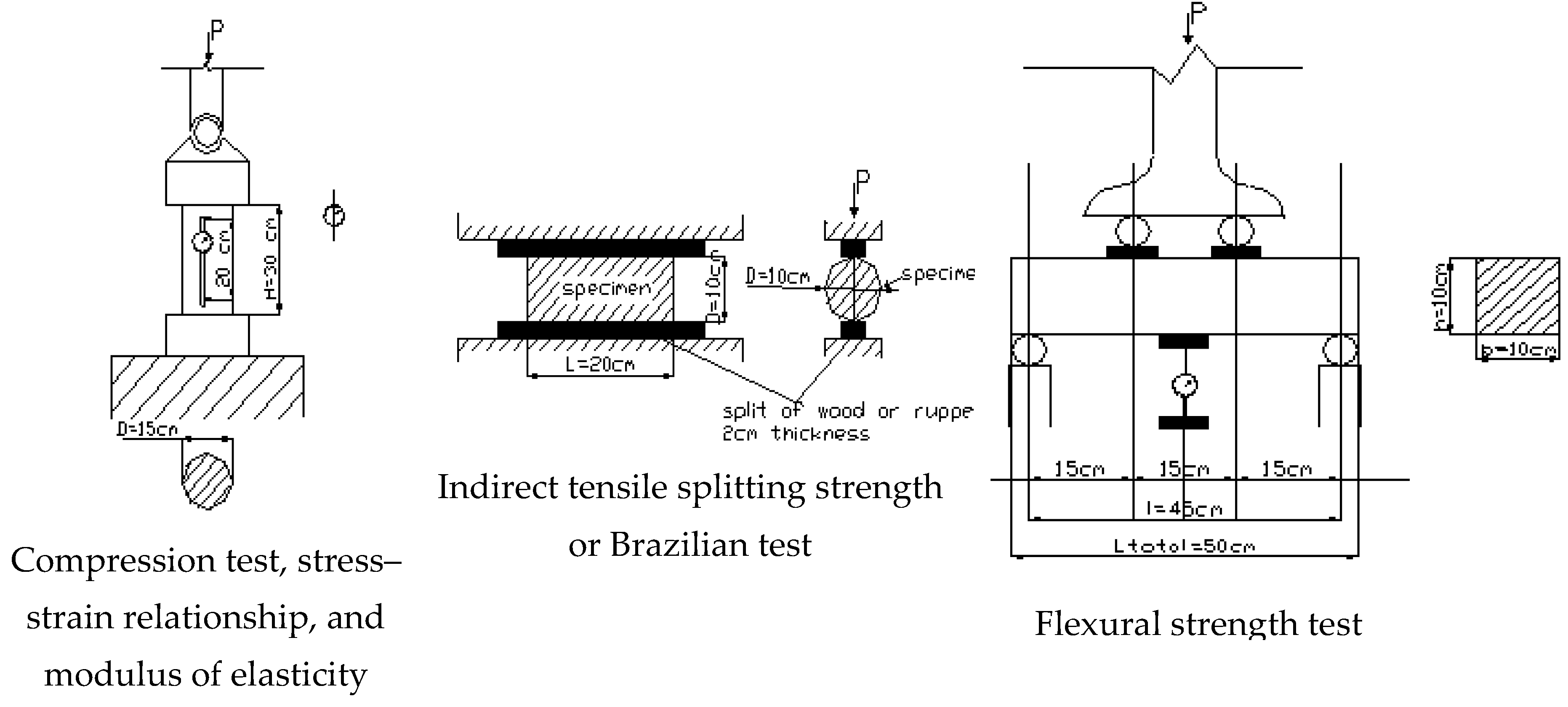

Cubes specimens measuring 100 x 100 x 100 mm were prepared for measuring the F

cu (ASTM C39/C39M-20). Cylindrical specimens measuring 100 x 200 mm were prepared for measuring the F

sp (ASTM C496/C496M-17), while other cylinders measuring 150 x 300 mm were prepared for determining the stress–strain relationship, cylindrical compressive strength (F

cy) (ASTM C39/C39M-20), and E

c (ASTM C469/C469M-14). Prisms measuring 100 x 100 x 500 mm were prepared for measuring the F

fl using four-point loading system (ASTM C78/C78M-18). Schematic diagrams for these tests are illustrated in

Figure 5. For each mixture and for each testing age, the average of three (3) samples that produce relative errors of less than 7% according to corresponding ASTM standards were only considered.

The concrete was placed in molds in layers of 50 mm in thickness and subjected to 30 blows using a standard compacting rod. The cast molds were then placed on a vibrating table for 30 seconds before surface finishing. The specimens were kept in the molds at a temperature of about 23°C and a relative humidity (RH) of 50% for 24 hours before demolding and storing in lime-water path at 23°C until the date of testing or 28 days at maximum. After 28 days, the specimens were removed from the water and kept in the laboratory atmosphere (a temperature of about 23°C and a RH of 50%). The results are the average of three samples.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Paste results

The evaluation of the pozzolanic activity of the WHA was made using the variation of electrical conductivity of a solution containing the tested WHA [

15,

17]. The electric conductivity of 5% Ca(OH)

2 solution (200 ml) at 40°C was measured, and then 5 gm of the WHA was added and stirred in the solution and the electrical conductivity was measured again after 2.0 minutes. The difference in the electrical conductivity measurements represents the potential of pozzolanic activity of the WHA. The variations in the electrical conductivity determined for the WHA

(0) (burnt in open air) and WHA

(600) (burnt in closed oven at 600

oC) according to [

15,

17] were 7.10 and 5.28 ms/cm, respectively. These values were significantly greater than the values set by the test as a limit for obtaining a material with a good pozzolanic activity characteristics (1.2 ms/cm).

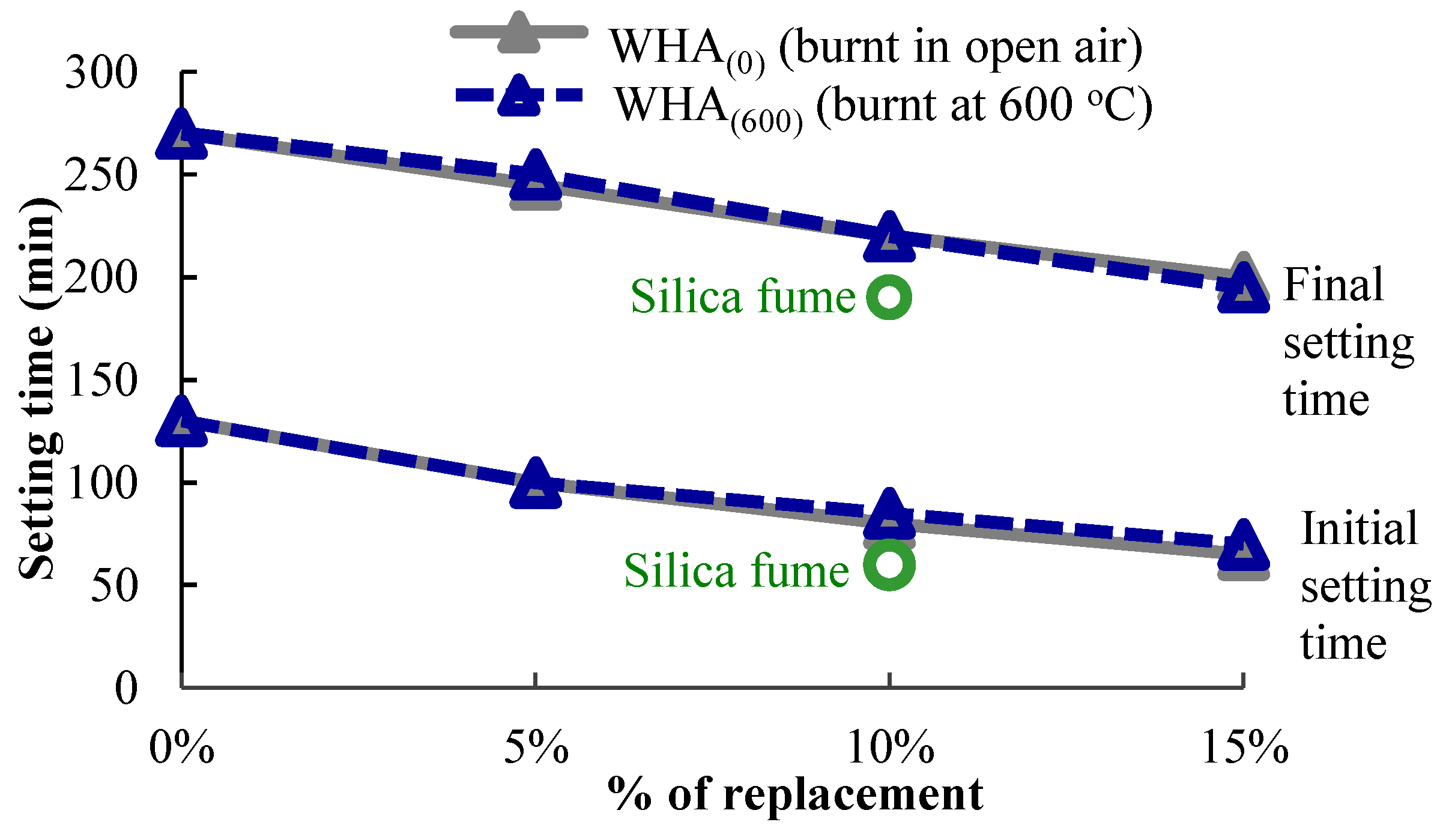

The chemical analysis of the WHA shows existence of a higher Al

2O

3 amount than the cement (6.77% for the WHA

(0) and 6.95% for the WHA

(600) versus 4.70% for the OPC), which has a potential effect on setting time. Therefore, the effect of the ash on the setting time was evaluated using paste mixtures incorporating all the WHA/cement and SF/cement combinations indicated in

Table 2 and made with the

w/cm that gives the normal consistency level. The Vicat apparatus was used to measure the initial and final setting times, and the results are presented in

Figure 6. shows the initial and final setting times determined using the Vicat needle test versus. The results of the different replacement ratios from the two types of WHA are compared to the 10% SF and the control mixture (with only OPC) in the figure. The results indicate that the setting times measured for the two WHA types obtained from the two different burning conditions are almost similar, this is due to the very close Al

2O

3 contents (6.77% vs. 6.95%). As expected, the mixtures incorporating WHA exhibited shorter setting times than the control, with more tendency to short setting times at the increased replacement ratios. This was due to the higher Al

2O

3 content in the WHA compared to the OPC. The 10% WHA (either under the different burning conditions) showed slight longer setting times than the mixture containing 10% SF due to the finer particles of the SF.

4.2. Mortar results

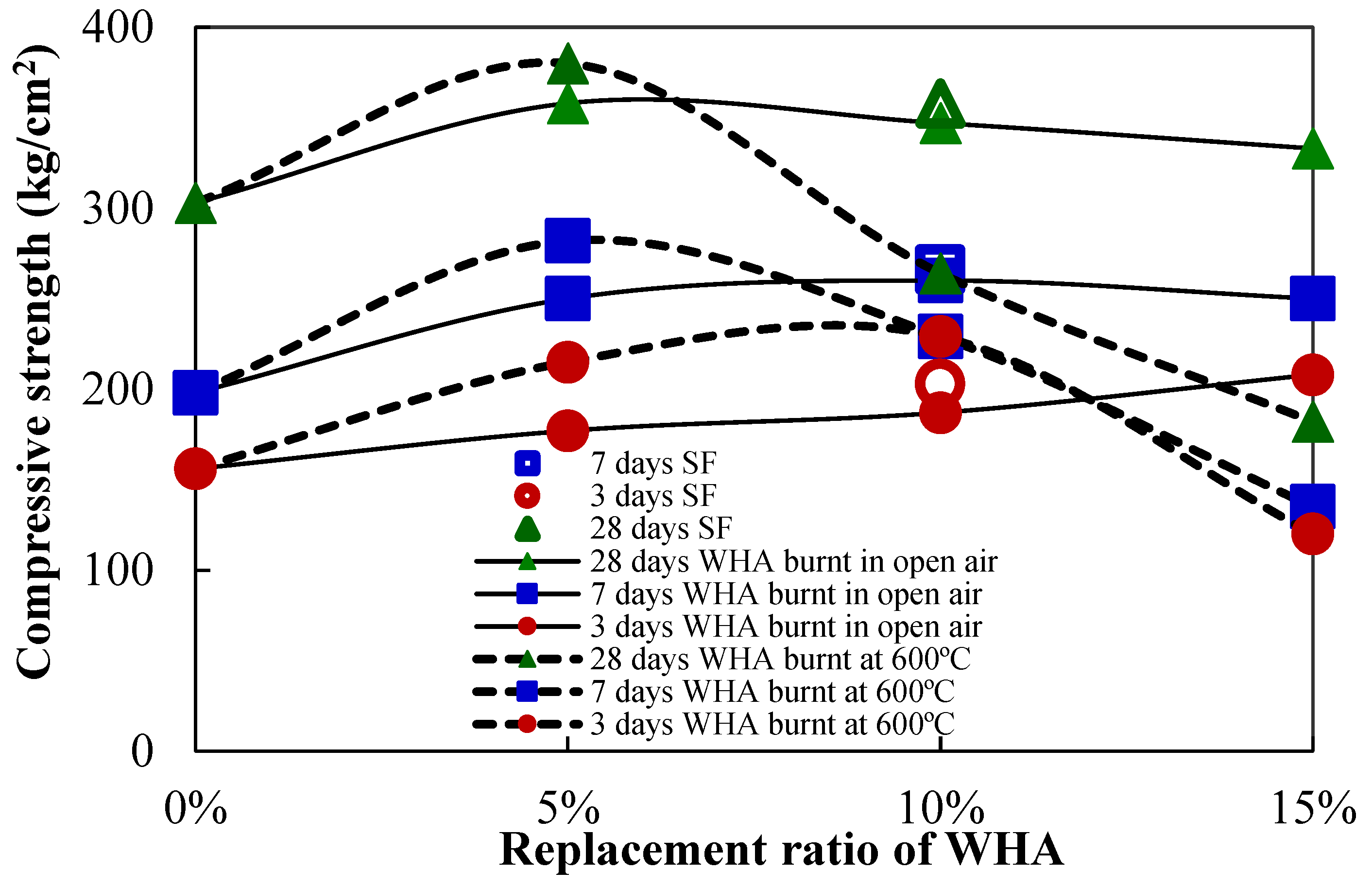

Figure 7 shows the effect of content and type of WHA on the mortar compressive strength at testing ages of 3, 7, and 28 days. For WHA

(600), the compressive strength increased with increase in the replacement ratio and reached a peak between 5% to 10% replacement ratio, then strength reduction was observed even below the control value at replacement beyond the 10% ratio. This trend was similar at all ages. For the WHA

(0), there was an increase in strength with the increase of replacement ratio. However, this increase was maximum at 7 days. The percentages of maximum increase in strength for 3, 7, and 28 days were 47%, 31%, and 18% for the WHA

(0), and were 61%, 42%, and 25% for WHA

(600), respectively.

By using 10% SF, the results obtained were 43%, 34%, and 18% higher than the control mix at 3, 7, and 28 days, respectively. The 3-, 7-, and 28-day strength results obtained from using 10% WHA can be comparable to those obtained from using 10% SF, with a minor decrease. This was mainly due to the higher fineness of the SF compared to the WHA.

The normalization of the compressive strength of the mortar mixtures made with the WHA or SF relative to that made only with OPC give the strength activity index (SAI). The ASTM C618-19 standard recognizes that the material resulting in SAI value either at 7 or 28 days higher than 0.75 is a good pozzolanic material. The SAI results shown in

Table 6, indicate that the cement replacement by any of the two WHA types or SF at all replacement levels were greater than 0.75 except for the 15% WHA

(600), which exhibited 0.68 and 0.60 at 7 and 28 days, respectively. The SAI values for the evaluated mortars indicated in

Table 6 confirm also the accelerating effect of the WHA in the early age (7 days) compared to the 28-day results.

4.3. Fresh concrete results

4.3.1. Workability

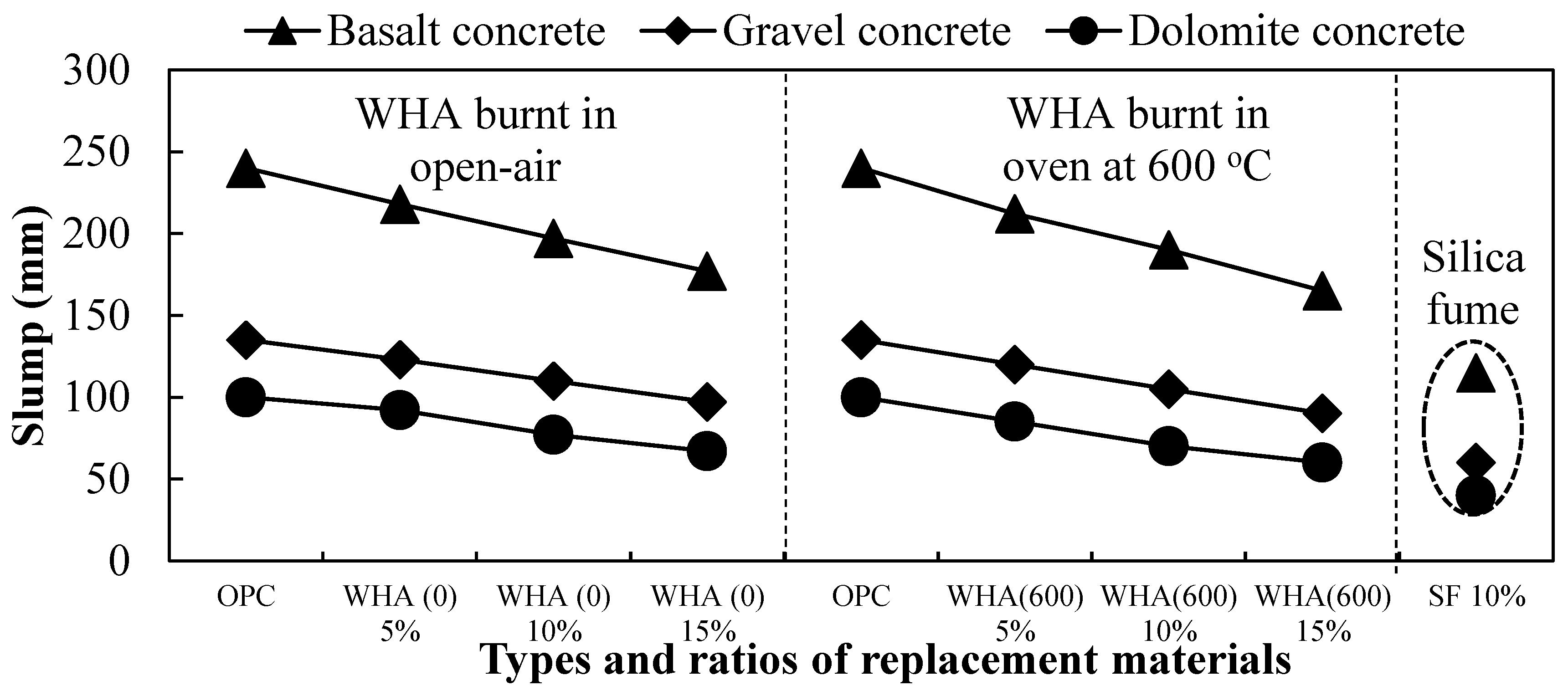

The workability of the concrete mixtures was measured directly using the Abraham cone at the end of mixing, and the results are shown in

Figure 8. When WHA or SF was introduced into the concrete, the workability decreased as part of cement was replaced with WHA or SF. The results showed also more slump loss with the increase in the replacement ratio by the WHA. The workability of concrete mixture is enhanced by decreasing the friction between aggregate particles, which can be achieved by increasing the paste content of the mixture. However, when the paste volume is constant, the characteristics of the particles of the cementitious materials play a significant role as in the current case. The WHA of the porous, angular, irregular shape, and rough textures particles required higher water content compared to the cement particles, given that the WHA and cement had approximately similar fineness. The higher percentage of the Al

2O

3 in the WHA compared to cement can also interpret the slump loss for the mixtures containing WHA. However, introducing the SF with large specific surface area compared to the cement particles required also higher water content to lubricate the surface area of the particle. While maintaining the same water contents for all concrete mixtures, this affected the final workability. There was a probability of workability increase with increasing WHA content due to the cement dilution, which tends to reduce the formation of cement hydration products in the first few minutes of mixing. Therefore, there were insufficient products to bridge various particles together. It is worth noting that the WHA replacement of cement was by weight. As the specific gravity of WHA was lower than that of cement, the solid particles-to-water ratio, by volume, was higher than in case of cement and WHA blends compared to only OPC. This increased the friction between the solids in the paste in the case of the WHA/OPC blend, thereby resulting in a slight improvement in workability. This positive effect of cement dilution on workability was less effective compared to the rough and porous WHA particles. The higher WHA content ended up with bad workability.

Relative to the control mixture, the slump losses for the concretes containing WHA(600) (burnt in controlled media at 600˚C) were slightly higher than those of the concretes containing WHA(0) (burnt in open air), due to the finer particles of the former compared to the latter ashes (d50 = 12 vs. 23 μm, respectively). In addition, the slump of gravel concretes was higher than that of basalt concretes, then the dolomite concretes, which ranked the third. This was related to the surface texture and shape of the aggregates. The natural gravel was rounded and solid surface texture, crushed dolomite had with irregular and angular shapes with more porosity, and the basalt was crushed with non-porous particles.

4.3.2. Unit weight

The unit weight results of the evaluated concrete mixtures are given in

Table 7. The control concrete mixtures gave the largest values: the gravel, dolomite, and basalt concretes resulted in 2364 2493, and 2527 kg/m

3 unit weight values, respectively, while the WHA concretes showed lower values than the control. The unit weight of concrete changes normally due to the change in the mix proportions or the properties of the ingredients used. In current results, the partial replacement of OPC by WHA of lower density of the WHA yielded lower unit weight values. In fact, the density values of the WHA

(600) concretes were lower than the control but higher than those containing the WHA

(0) or SF, because the densities of the OPC, WHA

(600), WHA

(0), and SF were 3.13, 2.65, 2.52, and 2.2, respectively.

4.4. Hardened concrete results

The results of the various mechanical properties of WHA concretes including compressive, tensile, and flexural strengths as well as the static Young’s modulus in compression are discussed in the following sections.

4.4.1. Cubes compressive strength (Fcu)

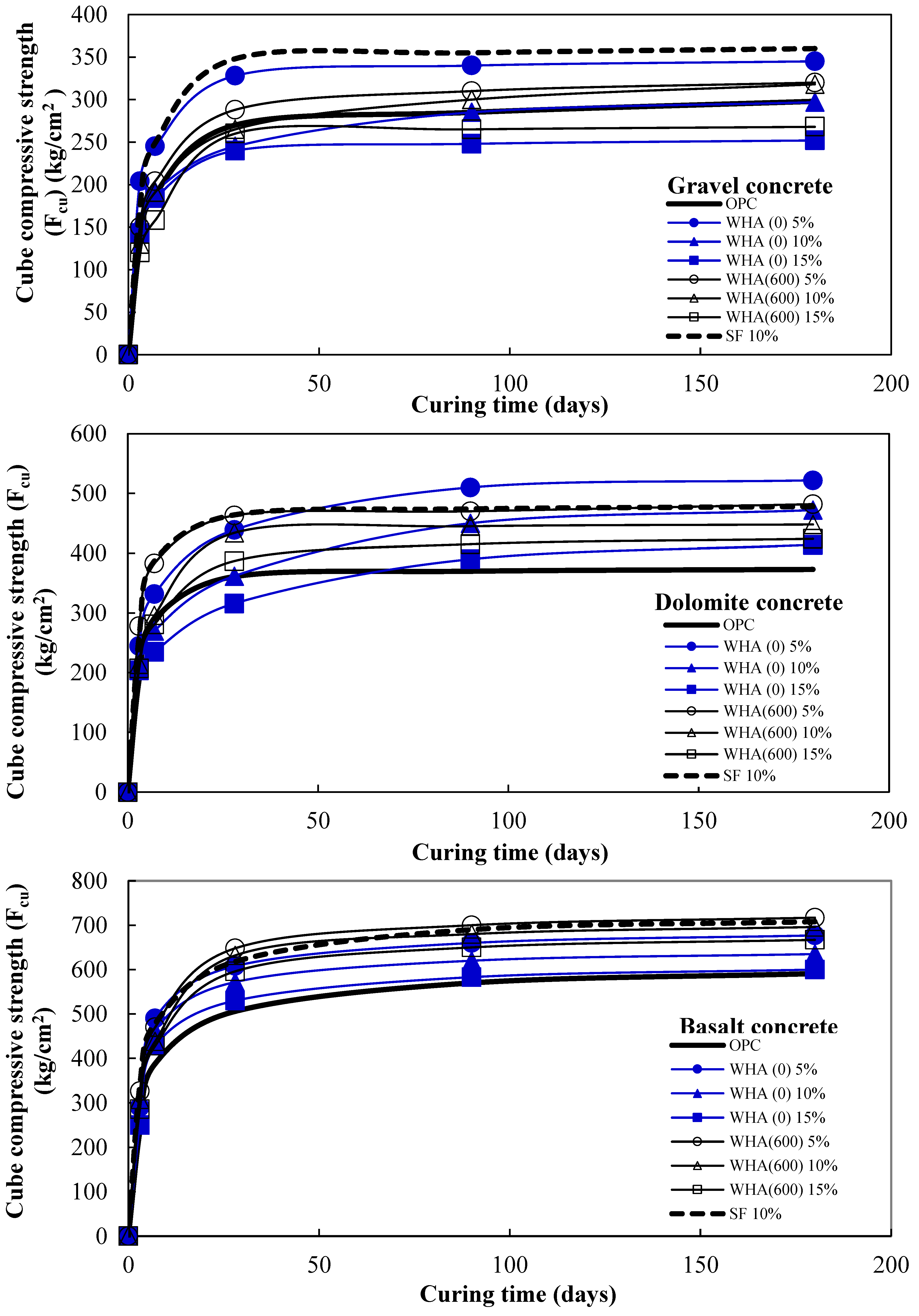

The results of the F

cu after curing periods of 3, 7, 28, 90, 180 days are shown in

Figure 9 for three types of coarse aggregates; gravel, dolomite, and basalt. Each reported result is an average of three specimens.

The Fcu increases with age but the rate of strength development was higher in the early age. Most of the strength development took place before the 90 days, with limited strength development beyond that. This indicates that the effect of the WHA on strength gain is approximately similar to the rapid hardening cement.

The F

cu for the concrete containing 5% and 10% WHA was higher than that of the reference. The pozzolanic reactivity and the filling effect of the WHA can explain this increase. On the other hand, the strength of the concrete containing 15% WHA was lower than that of the reference. This might be due to the fact that the quantity of WHA in the mix may be higher than the required to react with the liberated calcium hydroxide resulted from cement hydration, thus leading to excess silica leached out and causing a deficiency in strength as it replaces part of the cementitious material but does not contribute to strength. This was the case for both burning conditions; WHA

(0) and WHA

(600). This trend was same at all testing ages. The concrete made with 5% WHA in some cases were found similar or greater than the concrete containing 10% SF. The F

cu results for the WHA and SF concretes are matching the strength activity indices carried out on mortar (

Table 5). These findings are similar to the results obtained in [

19,

20].

The effect of burning method had no clear effect on the Fcu. The Fcu of the WHA(0) concretes were similar to those made with WHA(600) with little variations. This can be due to the temperature in the open-air burning of the WHA was around the 600oC used in the controlled oven-burning.

It can also be observed that the Fcu results for the basalt concretes were greater than dolomite concretes, which in their turn were greater than the gravel concretes. This is referred to the relative crushing strengths and the surface texture of different aggregates.

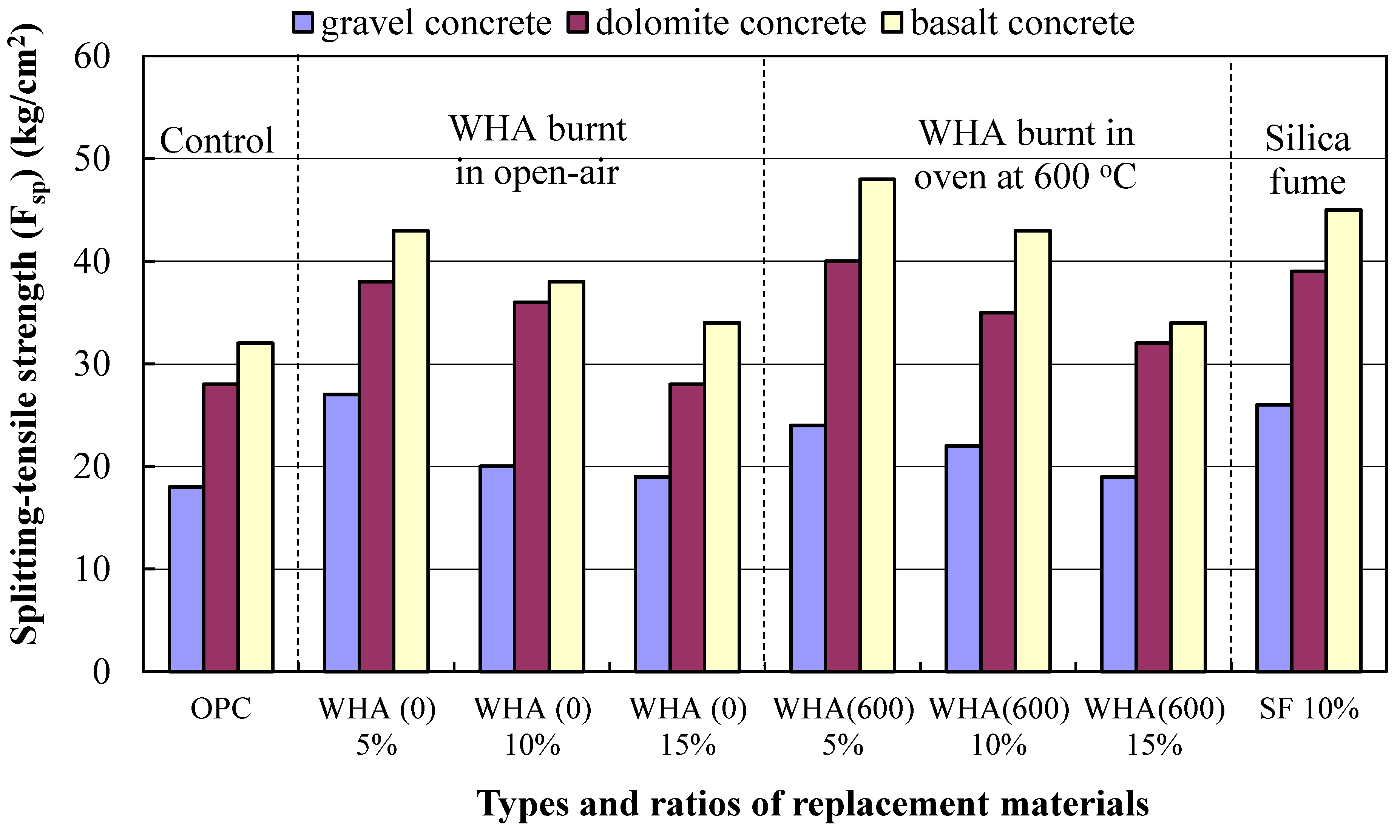

4.4.2. Splitting-tensile strength (Fsp)

Normally, plain concrete is not strong enough to resist tension loads, leading to cracking when subjected to shrinkage or any tensile stresses. So, improving the tensile strength of concrete by using alternative supplementary cementitious materials such as WHA is of importance for increasing the potential to crack resistance. The 28-day F

sp results for the 24 concrete mixtures listed in

Table 5, are illustrated in

Figure 10. Each reported F

sp result is an average of three specimens.

The F

sp for the concrete mixtures made with WHA at all replacement ratios were greater than the control concrete (with only cement). The maximum increase in the F

sp relative to the control were reported at 5% WHA and reached about 50%, such as in the case of gravel concrete with WHA

(0)5% and basalt concrete with WHA

(600)5%. These values were higher than those for the concrete mixtures containing 10% SF (the increase ranged between 39% and 44%). These findings are similar to the results obtained by other researchers [

19]. However, incorporating higher percentage of WHA than 5% resulted in reduction in the F

sp, but in all cases, it was greater than the reference. The increase in the F

sp with 15% WHA replacement was limited to less than 6% compared to the reference. As explained earlier in the compressive strength, this tensile strength gain can be due to the pozzolanic reactivity and the filling effect when incorporating WHA at 5% replacement, which becomes less effective at higher replacement ratios.

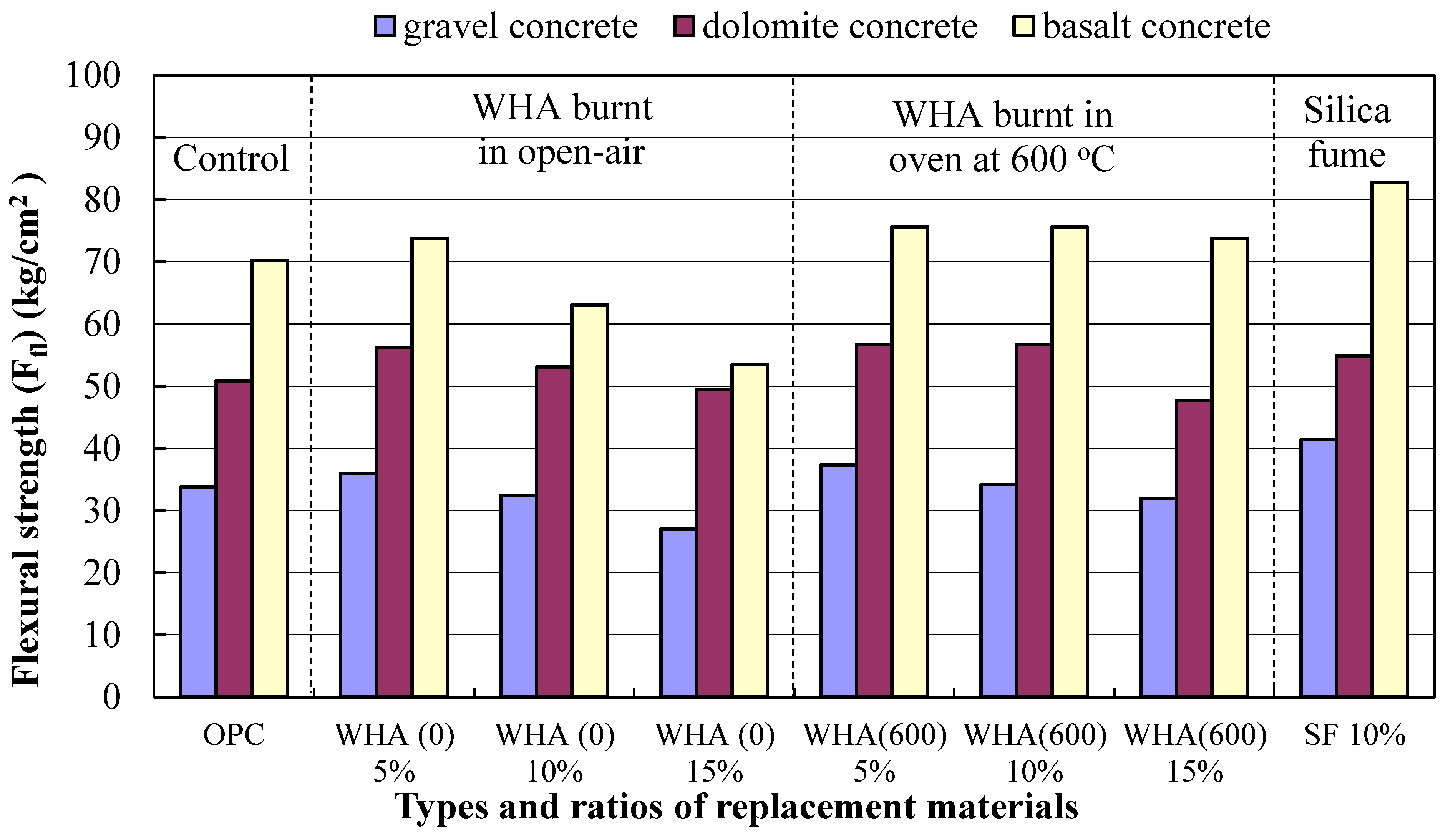

4.4.3. Flexural strength (Ffl)

The 28-day F

fl results carried out on the 24 concrete mixtures listed in

Table 5 are illustrated in

Figure 11. Each reported result is as an average of three prisms. Data from the F

fl tests showed approximately similar trend as that of the F

sp. In general, the F

fl results showed that all concrete mixtures (with different coarse aggregate types) made with 5% and 10% WHA replacement ratios were higher than control; however, the mixtures with 15% WHA were less. In addition, the F

fl when using WHA

(600) was higher compared to the WHA

(0). The results can confirm that the 5% WHA replacement ratio was the best resulting in the maximum F

fl, which in its turn was a bit less than the concretes made with 10%SF. In addition to the pozzolanic reactivity and the filling capacity, the enhancement in the F

fl when using the WHA can be referred to the enhancement in the transition zones between the cement paste and aggregates.

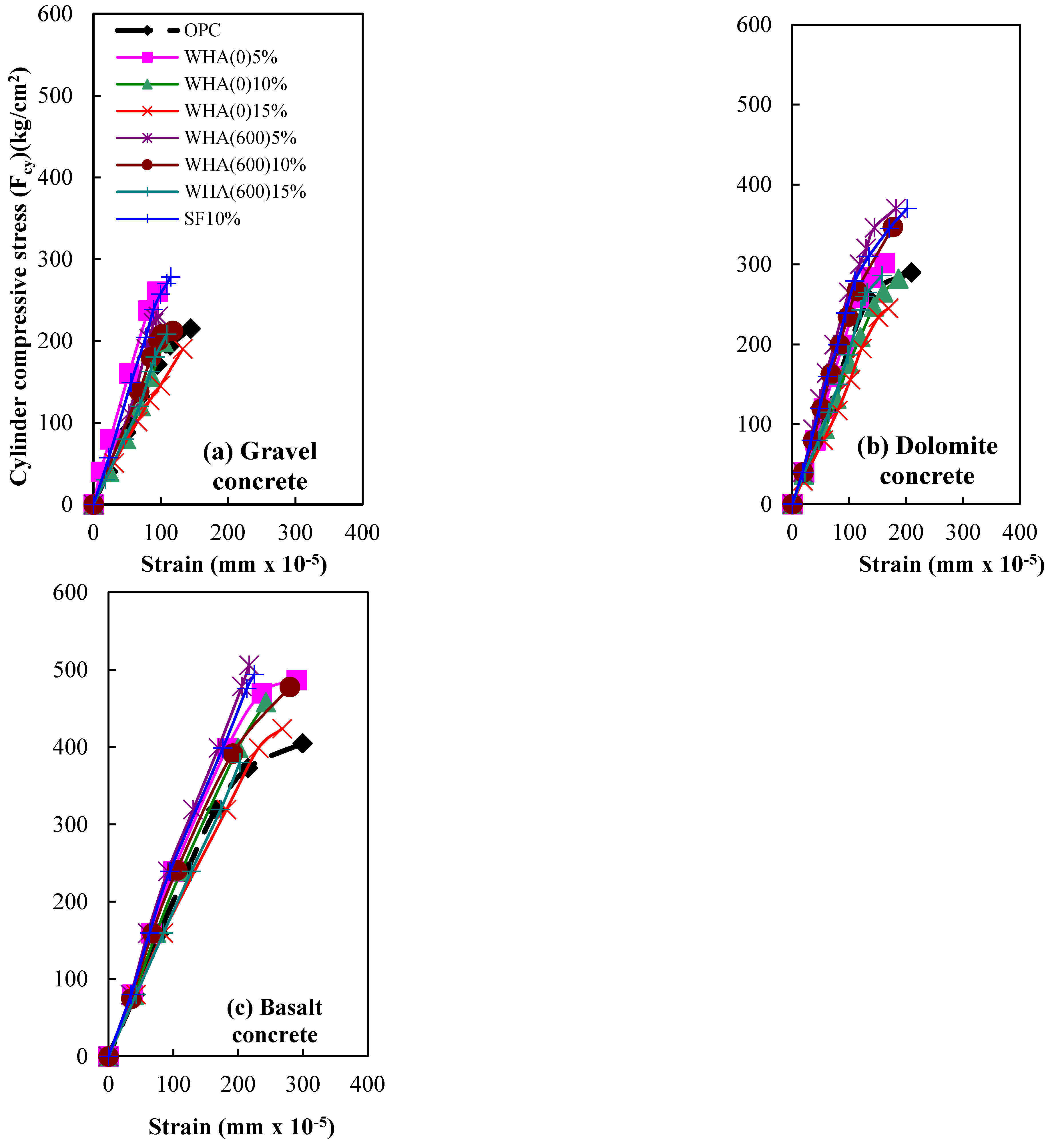

4.4.4. Stress–strain relationship and modulus of elasticity (Ec)

For each cylinder, the stress–strain in compression was measured using a 20-cm mechanical strain gauge until the maximum stress (strength) is reached.

Figure 12 shows comparisons between the stress–strain relationships for the gravel, dolomite, and basalt concretes using cylinders specimens. As expected, the concretes made with basalt showed the maximum load capacity, followed by those made with dolomite, then by the gravel aggregates, governed by the relative hardness of the various aggregate types.

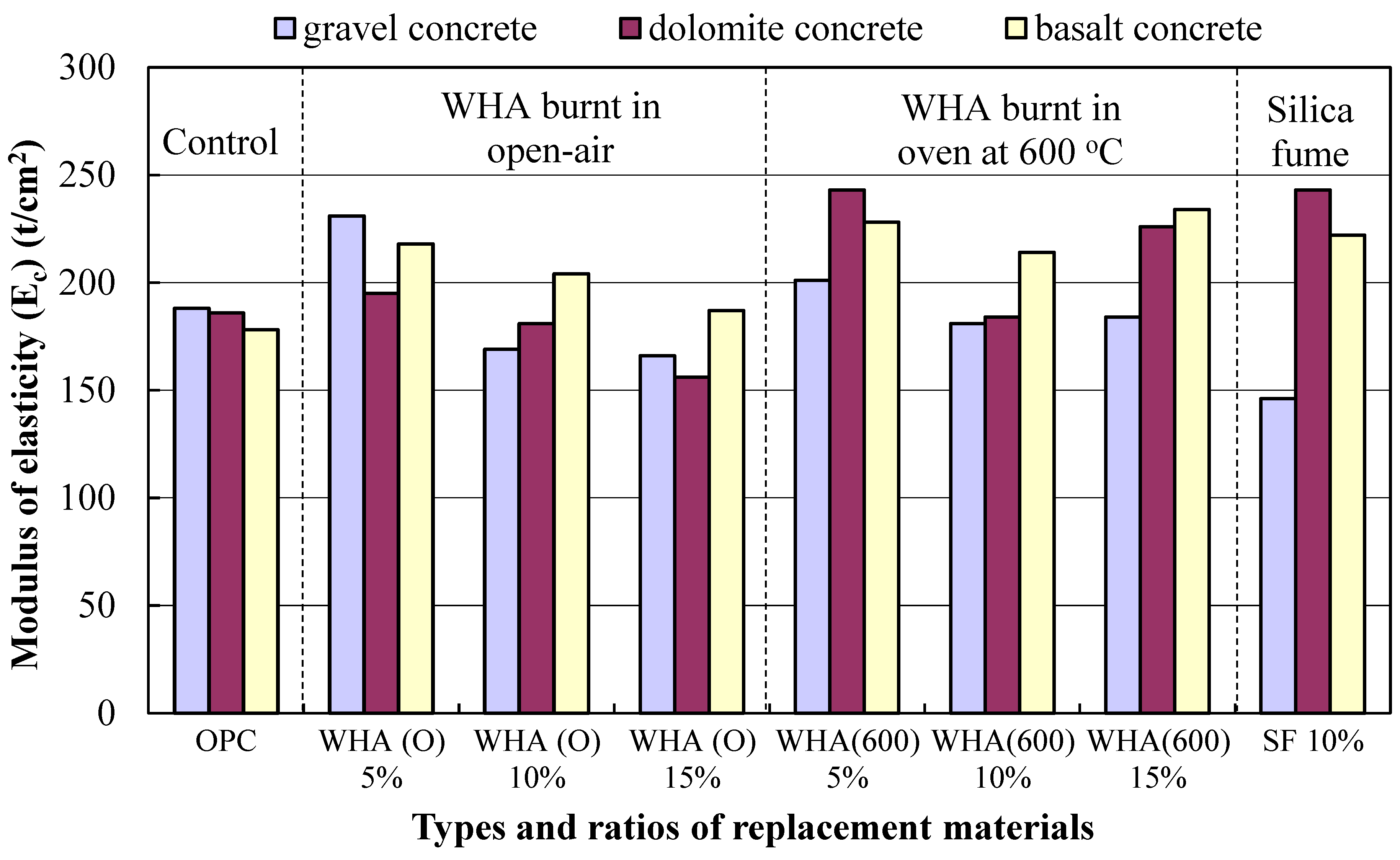

Concrete as a structural material is elastic to a certain extent. The E

c was calculated as the initial tangent of the stress-strain curve during this elastic region. The E

c values for the concretes under investigation are illustrated in

Figure 13. The dolomite concretes with all replacement materials and ratios were found to be greater than the reference, proofing the satisfactory adherence between the cement paste and dolomite. The 5% WHA replacement ratio was again proved to be the most effective replacement ratio in enhancing the E

c, as the case in enhancing the other strengths.

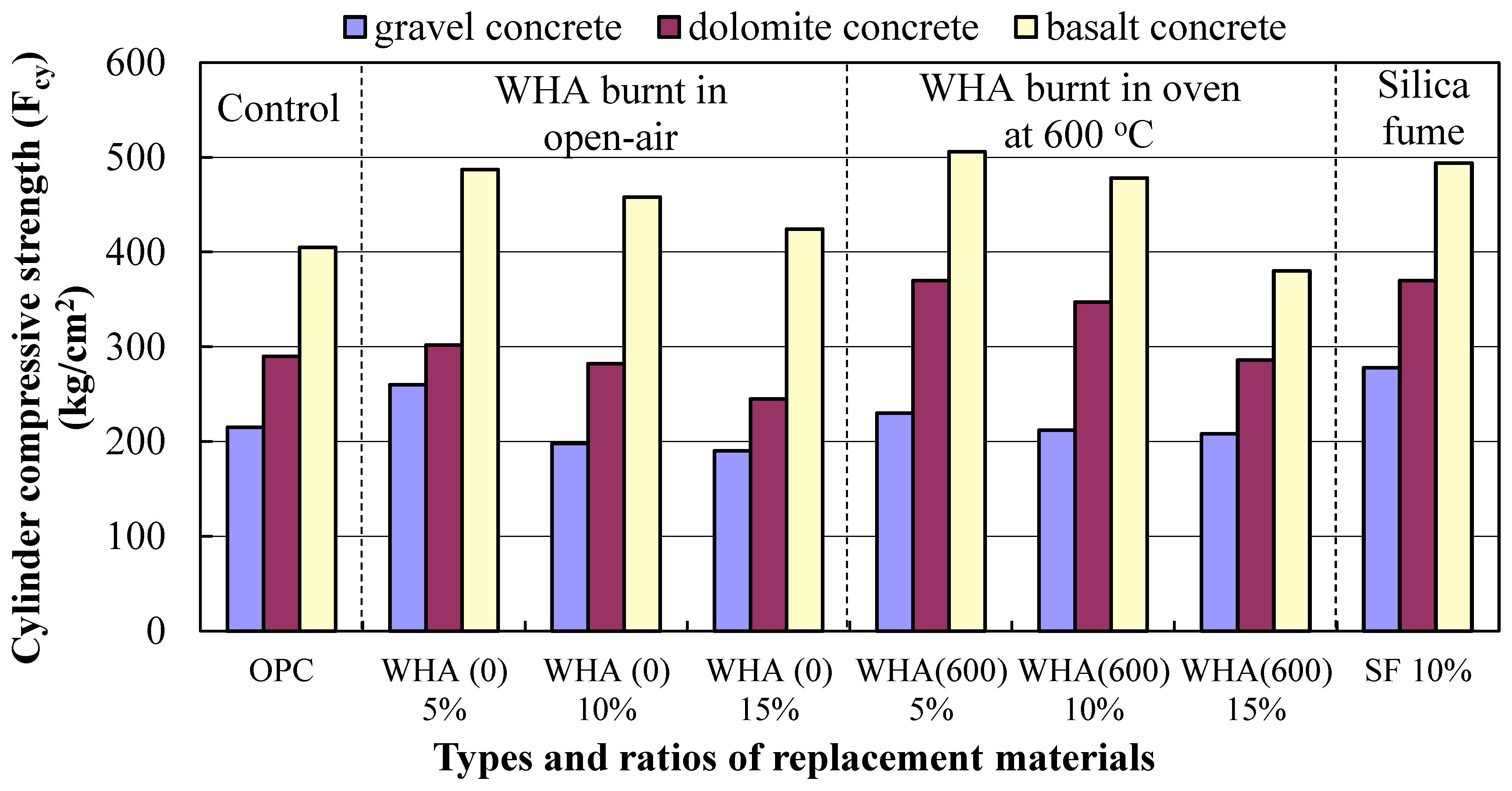

4.4.5. Relationship between cylindrical and cubic compressive strength

The maximum cylindrical compressive strength (F

cy), obtained when measuring the stress–strain curves, were measured and illustrated in

Figure 14. The F

cy was measured at the age of 28 days. These results are matching those reported in

Figure 9.

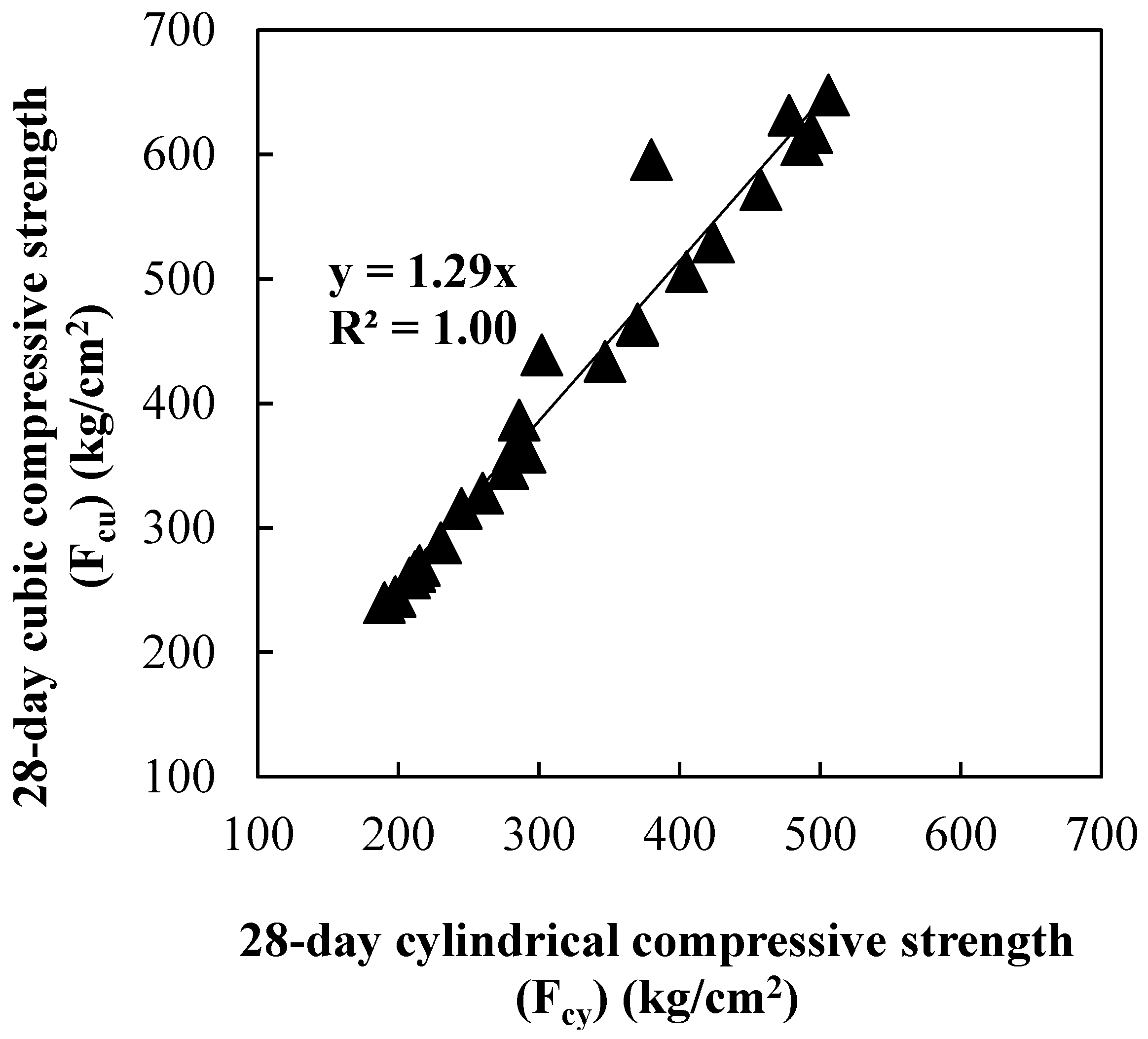

The 28-day F

cy were correlated to the 28-day F

cu from

Figure 9, as given in

Figure 15. This correlation reveals a linear relationship with 30% increase in the F

cu compared to the F

cy.

5. Conclusions

The research concerns using water hyacinth (W.H.), which obstructs navigation and absorbs huge quantities of water, as a partial replacement of cement. Based on the experimental program achieved, it can be concluded that:

Using water hyacinth plants after burning as a cement replacement material in concrete mixes participates in keeping the environment clean. Otherwise, these plants can hinder the watercourse navigation, absorb large quantiles of fresh water, and increase the amount of waste materials on rivers banks.

Considering the water hyacinth as a waste material, its valorization in concrete as cement replacement could be considered as cost saving of cement production.

In manufacturing the water hyacinth ash (WHA), burning in closed ovens produces ash with similar composition to that burnt in open air, but with less effect on the environment.

The electric conductivity on a 5% Ca(OH)2 solution carried out on WHA burned in the two conditions (air and in closed oven at 600oC) proved a good pozzolanic activity of these ashes.

The strength activity index (SAI) determined for mortar made with 5% and 10% WHA replacement ratio shows higher values than 0.75 stipulated by the ASTM C618-19 to consider the material as a pozzolanic.

The WHA is an accelerating additive that decreases the initial and final setting times by up to 50% due to the existence of higher Al2O3 content.

At the same w/cm ratio, more slump loss can be expected when incorporating higher WHA replacement ratios in concrete due to the porous, angular, irregular shape, and rough textures of the WHA particles that requires higher water content compared to the cement particle, given that the investigated WHA and cement have approximately similar fineness.

Using 5% WHA as cement replacement was found to be the best, leading to a distinguished increase in concrete strength compared to the control due to the pozzolanic activity, filling capacity, and enhancing the transition zones between cement paste and aggregate. The results obtained from using the 5% WHA are quite similar to those obtained from using 10% silica fume. The 10% WHA replacement ratio can also result in concrete with performance better than the reference. However, the 15% cannot contribute to strength improvement compared to the control.

Data Availability

No data, models, or code were generated or used during the study.

References

- Aïtcin P-C “Cements of yesterday and today – concrete of tomorrow” Journal of Cement and Concrete Research, 2000;30(9):1349-1359.

- Matte V, Moranville M, Adenot F, Riche C, Torrenti JM “Simulated microstructure and transport properties of ultra-high-performance cement-based materials” Journal of Cement and Concrete Research, 2000;30(12):1947-1954.

- Khan SU, Nuruddin MF, Ayub T, Shafiq N “Effects of Different Mineral Admixtures on the Properties of Fresh Concrete” Scientific World Journal, 2014; 986567. [CrossRef]

- Bouzoubaa N, Min-Hong Zhang VM, Malhotra VM, Golden DM “Blended fly ash cement – a review” ACI Materials Journal, 1999;641-650.

- Karim MR, Hossain MM, Khan MNN, Zain MFM, Jamil M, Lai FC “On the Utilization of Pozzolanic Wastes as an Alternative Resource of Cement”, Journal of Materials MDPI, 2014 (7); 7809-7827; [CrossRef]

- Kareem Q, AL-Jumaily IAS, Hilal N “An overview on the Influence of Pozzolanic Materials on Properties of Concrete”, International Journal of Enhanced Research in Science Technology & Engineering, March 2015, 4(3);81-92.

- Anwar M, Miyagawa T, Gaweesh M, “Using rice husk ash as a cement replacement material in concrete”, Journal of Waste Management Series, 2000 (1): 671-684, . [CrossRef]

- Sculthorpe CD “The Biology of aquatic vascular plants” Hardcover, Publisher: Lubrecht & Cramer Ltd; 2 Edition, June 1985, ISBN-10: 3874292576, ISBN-13: 978-3874292573.

- Bergier I, Salis SM, Miranda CHB, Ortega E, Luengo CA “Biofuel production from water hyacinth in the Pantanal wetland” Journal of Ecohydrology & Hydrobiology, 2012, 12(1):77-84. [CrossRef]

- Water Canal Maintenance Research Institute “A guide to water weeds and ways to limit their spread”, December 1999.

- El-Enany AE, Mazen AMA “Isolation of Cd-binding protein of water hyacinth (E. Crassipes) grown in nile river water” Water, Air, and Soil pollution, 1996;87(1-4):357-362.

- Omran AFM, “Feasibility of using water hyacinth as concrete admixtures”, Master thesis, Faculty of Engineering, Minoufiya University, in Egypt, 2003;250.

- Abdel-Hay AS, “Impact of water hyacinth on properties of concrete made with various gravel to dolomite ratios” Proc. of the 3rd Intl. Conf. “Advances in Civil, Structural and Mechanical Engineering- CSM 2015”, Publisher: Institute of Research Engineers and Doctors, USA. ISBN: 978-1-63248-062-0, May 2015;76-80. [CrossRef]

- Ghutke VS, Bhandari PS “Influence of silica fume on concrete”, International Conference on Advances in Engineering & Technology (ICAET-2014), IOSR Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering (IOSR-JMCE) e-ISSN: 2278-1684, p-ISSN: 2320-334X, 2014;44-47.

- Velázquez S, Monzó JM, Borrachero MV, Payá J “Assessment of Pozzolanic Activity Using Methods Based on the Measurement of Electrical Conductivity of Suspensions of Portland Cement and Pozzolan”, Journal of Materials MDPI, 2014 (7); 7533-7547; [CrossRef]

- Xu W, Lo TY, Wang W, Ouyang D, Wang P, Xing F “Pozzolanic Reactivity of Silica Fume and Ground Rice Husk Ash as Reactive Silica in a Cementitious System: A Comparative Study”, Journal of Materials MDPI, 2016;9(3):146, . [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran V “Concrete science”, Heyden & Sons Ltd., London, 1981.

- Makhlouf AAAH, “Application of water hyacinth ash as a partial replacement for cement”, PhD thesis, Cairo University, Egypt, 2002.

- Abdel Hay AS, Fawzy YA“Impact of water hyacinth on properties of concrete made with various gravel to dolomite ratios,” Proc. of the 3rd Intl. Conf. Advances in Civil, Structural and Mechanical Engineering-CSM 2015, Institute of Research Engineers and Doctors, USA, ISBN: 978-1 -63248-062-0; 76-80. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan S, MurugeshV “Experimental study on strength of water hyacinth ash as partial replacement of cement in concrete”, International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, March-2018;9(3);93-96.

- Nancy A. Soliman, Tagnit-Hamou A. (2016) Development of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete using Glass Powder ─ Towards Ecofriendly Concrete. Journal of Construction and Building Materials, 125: 600–612. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Omran, Nancy A. Soliman, Ailing Xie, Tatyana Davidenko, Arezki Tagnit-Hamou (2018) Field trials with concrete incorporating biomass-fly ash. Journal of Construction and Building Materials, 186: 660-669.

- Ahmed Omran, Nancy A. Soliman, Ablam Zidol, Arezki Tagnit-Hamou (2018) Performance of ground glass pozzolan as a cementitious material – a review, ASTM Journal of Advances in Civil Engineering Materials; 7(1):237-270.

Figure 1.

Water-hyacinth plant and its spread in watercourses.

Figure 1.

Water-hyacinth plant and its spread in watercourses.

Figure 2.

Fresh and dried water hyacinth plants, and water-hyacinth ashes (WHA).

Figure 2.

Fresh and dried water hyacinth plants, and water-hyacinth ashes (WHA).

Figure 3.

Particle-size distribution of water-hyacinth ash (WHA) burnt in open air and closed oven at 600 oC.

Figure 3.

Particle-size distribution of water-hyacinth ash (WHA) burnt in open air and closed oven at 600 oC.

Figure 4.

SEM micrograph of WHA particles [

18].

Figure 4.

SEM micrograph of WHA particles [

18].

Figure 5.

Schematic diagrams for compressive, indirect-tensile, and flexural strength tests and modulus of elasticity.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagrams for compressive, indirect-tensile, and flexural strength tests and modulus of elasticity.

Figure 6.

Initial and final setting times for paste mixtures made with different types and contents of water-hyacinth ash (WHA) in comparison to control and 10% silica fume.

Figure 6.

Initial and final setting times for paste mixtures made with different types and contents of water-hyacinth ash (WHA) in comparison to control and 10% silica fume.

Figure 7.

Compressive strength (after 3, 7, and 28 days of curing) of mortar mixtures versus replacement ratio.

Figure 7.

Compressive strength (after 3, 7, and 28 days of curing) of mortar mixtures versus replacement ratio.

Figure 8.

Slump consistencies of investigated concrete mixtures.

Figure 8.

Slump consistencies of investigated concrete mixtures.

Figure 9.

Development of cube compressive strength (Fcu) for the investigated concrete mixtures.

Figure 9.

Development of cube compressive strength (Fcu) for the investigated concrete mixtures.

Figure 10.

Splitting-tensile strength (Fsp) (after 28 days of curing) for investigated concrete mixtures.

Figure 10.

Splitting-tensile strength (Fsp) (after 28 days of curing) for investigated concrete mixtures.

Figure 11.

Flexural strength (Ffl) (after 28 days of curing) for investigated concrete mixtures.

Figure 11.

Flexural strength (Ffl) (after 28 days of curing) for investigated concrete mixtures.

Figure 12.

Stress-strain curves after 28 days of curing for the investigated concrete mixtures.

Figure 12.

Stress-strain curves after 28 days of curing for the investigated concrete mixtures.

Figure 13.

Modulus of elasticity (Ec) (after 28 days of curing) for investigated concrete mixtures.

Figure 13.

Modulus of elasticity (Ec) (after 28 days of curing) for investigated concrete mixtures.

Figure 14.

Cylinder compressive strength (after 28 days of curing) for investigated concrete mixtures.

Figure 14.

Cylinder compressive strength (after 28 days of curing) for investigated concrete mixtures.

Figure 15.

Relationship between 28-day compressive strength carried out using cubes and cylinders for investigated concrete mixtures.

Figure 15.

Relationship between 28-day compressive strength carried out using cubes and cylinders for investigated concrete mixtures.

Table 1.

Heavy metal contents of WHA (ppm) (average analysis of root, stem, and leaves) [

14].

Table 1.

Heavy metal contents of WHA (ppm) (average analysis of root, stem, and leaves) [

14].

| HEAVY METALS |

PPM |

Iron

Magnesium

Copper

Cadmium

Zinc

Lead

Vanadium

Nickel

cobalt |

5200

2732

110

57

155

243

90

234

44 |

Table 2.

Tested parameters.

Table 2.

Tested parameters.

| TYPE OF REPLACEMENT |

REPLACEMENT % |

SYMBOL |

AGGREGATE |

| Only OPC, served as control |

0 |

Pure cement |

The concrete mixtures were designed with three aggregate types: gravel, dolomite, and basalt. |

| WHA burnt in open air (WHA(0)) |

5% |

WHA(0)5% |

| 10% |

WHA(0)10% |

| 15% |

WHA(0)15% |

| WHA burnt in oven at 600˚C (WHA(600)) |

5% |

WHA(600)5% |

| 10% |

WHA(600)10% |

| 15% |

WHA(600)15% |

| SF |

10% |

SF 10% |

Table 3.

Chemical composition and physical properties of cement, silica fume, and water-hyacinth ash (WHA).

Table 3.

Chemical composition and physical properties of cement, silica fume, and water-hyacinth ash (WHA).

| |

Constituent |

Cement |

Silica fume |

Water-hyacinth ash (WHA) |

| Burnt in air |

Burnt in 600°C |

| Chemical composition |

SiO2 |

19.49 |

93.00 |

33.9 |

34.5 |

| Ti2O3

|

— |

— |

0.75 |

0.78 |

| Al2O3

|

4.70 |

0.5 |

6.77 |

6.95 |

| Fe2O3

|

3.28 |

1.5 |

5.77 |

6.02 |

| SO3

|

3.4 |

0.2 |

— |

— |

| MgO |

2.40 |

0.5 |

5.40 |

5.93 |

| CaO |

62.8 |

0.2 |

10.08 |

11.46 |

| Na2O |

0.38 |

0.5 |

1.26 |

1.41 |

| K2O |

0.95 |

0.5 |

9.83 |

10.98 |

| H2O |

— |

0.6 |

— |

— |

| MnO |

— |

— |

0.66 |

0.73 |

| P2O5

|

— |

— |

1.04 |

1.13 |

| Cl‾ |

— |

— |

3.82 |

4.02 |

| SO4‾ ‾ |

— |

— |

2.37 |

3.74 |

| Loss On Ignition (LOI) |

2.4 |

1.5 |

17.93 |

11.91 |

| total |

99.8 |

|

99.60 |

99.54 |

| Physical properties |

Blaine surface area (m2/kg) |

300 |

17000 |

— |

— |

| Bulk density (kg/m3) |

— |

280 |

— |

— |

| Specific gravity |

3.13 |

2.20 |

2.52 |

2.65 |

| Color |

— |

Light gray |

Dark gray |

Light brown |

Table 4.

Physical and mechanical properties of sand and coarse aggregates.

Table 4.

Physical and mechanical properties of sand and coarse aggregates.

| Property |

Fine aggregate (sand) (FA) |

Coarse aggregates (CA) |

| Gravel |

Dolomite |

Basalt |

| Specific gravity (SSD) |

2.58 |

2.52 |

2.78 |

2.85 |

| Volume weight (t/m³) |

1.710 |

1.630 |

1.615 |

1.682 |

| Void ratio (%) |

33.72 |

35.2 |

41.9 |

41.0 |

| Aggregate crushing value (%) |

— |

15 |

19 |

12 |

| Fineness modulus |

2.71 |

7.55 |

7.45 |

7.60 |

| Clay, silt, and fine dust (% by weight) |

2.13 |

— |

— |

— |

| Chloride (% by weight) |

0.031 |

0.027 |

0.032 |

0.023 |

| Sulfate (% by weight) |

— |

0.130 |

0.190 |

0.160 |

Table 5.

Concrete mix design.

Table 5.

Concrete mix design.

| Group |

Mix no. |

Mix proportions (kg/m³) |

w/cm |

CA/FA |

Rep/C |

| C |

W |

FA |

CA |

Replacement (Rep) |

| WHA(0)

|

WHA(600)

|

SF |

| Gravel concrete |

OPC |

300 |

150 |

638 |

1276 |

— |

— |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

— |

| WHA(0)5% |

285 |

150 |

637 |

1274 |

15 |

— |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.05 |

| WHA(0)10% |

270 |

150 |

636 |

1272 |

30 |

— |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.10 |

| WHA(0)15% |

255 |

150 |

635 |

1270 |

45 |

— |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.15 |

| WHA(600)5% |

285 |

150 |

637 |

1274 |

— |

15 |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.05 |

| WHA(600)10% |

270 |

150 |

637 |

1273 |

— |

30 |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.10 |

| WHA(600)15% |

255 |

150 |

635 |

1271 |

— |

45 |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.15 |

| SF 10% |

270 |

150 |

635 |

1269 |

— |

— |

30 |

0.5 |

2 |

0.10 |

| Dolomite concrete |

OPC |

300 |

150 |

681 |

1362 |

— |

— |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

— |

| WHA(0)5% |

285 |

150 |

680 |

1360 |

15 |

— |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.05 |

| WHA(0)10% |

270 |

150 |

679 |

1358 |

30 |

— |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.10 |

| WHA(0)15% |

255 |

150 |

678 |

1356 |

45 |

— |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.15 |

| WHA(600)5% |

285 |

150 |

680 |

1360 |

— |

15 |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.05 |

| WHA(600)10% |

270 |

150 |

679 |

1359 |

— |

30 |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.10 |

| WHA(600)15% |

255 |

150 |

679 |

1357 |

— |

45 |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.15 |

| SF 10% |

270 |

150 |

677 |

1355 |

— |

— |

30 |

0.5 |

2 |

0.10 |

| Basalt concrete |

OPC |

300 |

150 |

692 |

1385 |

— |

— |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

— |

| WHA(0)5% |

285 |

150 |

691 |

1382 |

15 |

— |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.05 |

| WHA(0)10% |

270 |

150 |

690 |

1380 |

30 |

— |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.10 |

| WHA(0)15% |

255 |

150 |

689 |

1378 |

45 |

— |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.15 |

| WHA(600)5% |

285 |

150 |

692 |

1383 |

— |

15 |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.05 |

| WHA(600)10% |

270 |

150 |

691 |

1381 |

— |

30 |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.10 |

| WHA(600)15% |

255 |

150 |

690 |

1380 |

— |

45 |

— |

0.5 |

2 |

0.15 |

| SF 10% |

270 |

150 |

689 |

1377 |

— |

— |

30 |

0.5 |

2 |

0.10 |

Table 6.

Strength activity index (SAI) of tested mortars.

Table 6.

Strength activity index (SAI) of tested mortars.

| Materials |

Replacement ratio |

Pozzolanic activity index |

| 7 days |

28 days |

| Pure OPC |

0% |

1.00 |

1.00 |

| WHA burnt in open air, WHA(0) |

5% |

1.26 |

1.18 |

| 10% |

1.31 |

1.15 |

| 15% |

1.26 |

1.10 |

| WHA burnt in oven at 600ºC, WHA(600)

|

5% |

1.42 |

1.25 |

| 10% |

1.16 |

0.87 |

| 15% |

0.68 |

0.60 |

| S.F. |

10% |

1.34 |

1.18 |

Table 7.

Fresh concrete unit weight.

Table 7.

Fresh concrete unit weight.

Concrete

mixture |

Unit weight (kg/m³) |

| Gravel |

Dolomite |

Basalt |

| OPC |

2364 |

2493 |

2527 |

| WHA(0)5% |

2361 |

2490 |

2524 |

| WHA(0)10% |

2358 |

2487 |

2521 |

| WHA(0)15% |

2355 |

2483 |

2517 |

| WHA(600)5% |

2362 |

2490 |

2525 |

| WHA(600)10% |

2359 |

2488 |

2522 |

| WHA(600)15% |

2357 |

2486 |

2520 |

| SF 10% |

2354 |

2482 |

2516 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).