Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

Plant Material and Sample Preparation

RNA Library Construction and High-Throughput Sequencing

RNA-Sequencing Data Analysis

Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Construction

3. Results

Root Phenotype Analysis

Overview of RNA-Seq Data

Screening and Analysis of DEGs

GO Enrichment and KEGG Pathway Analysis of DEGs

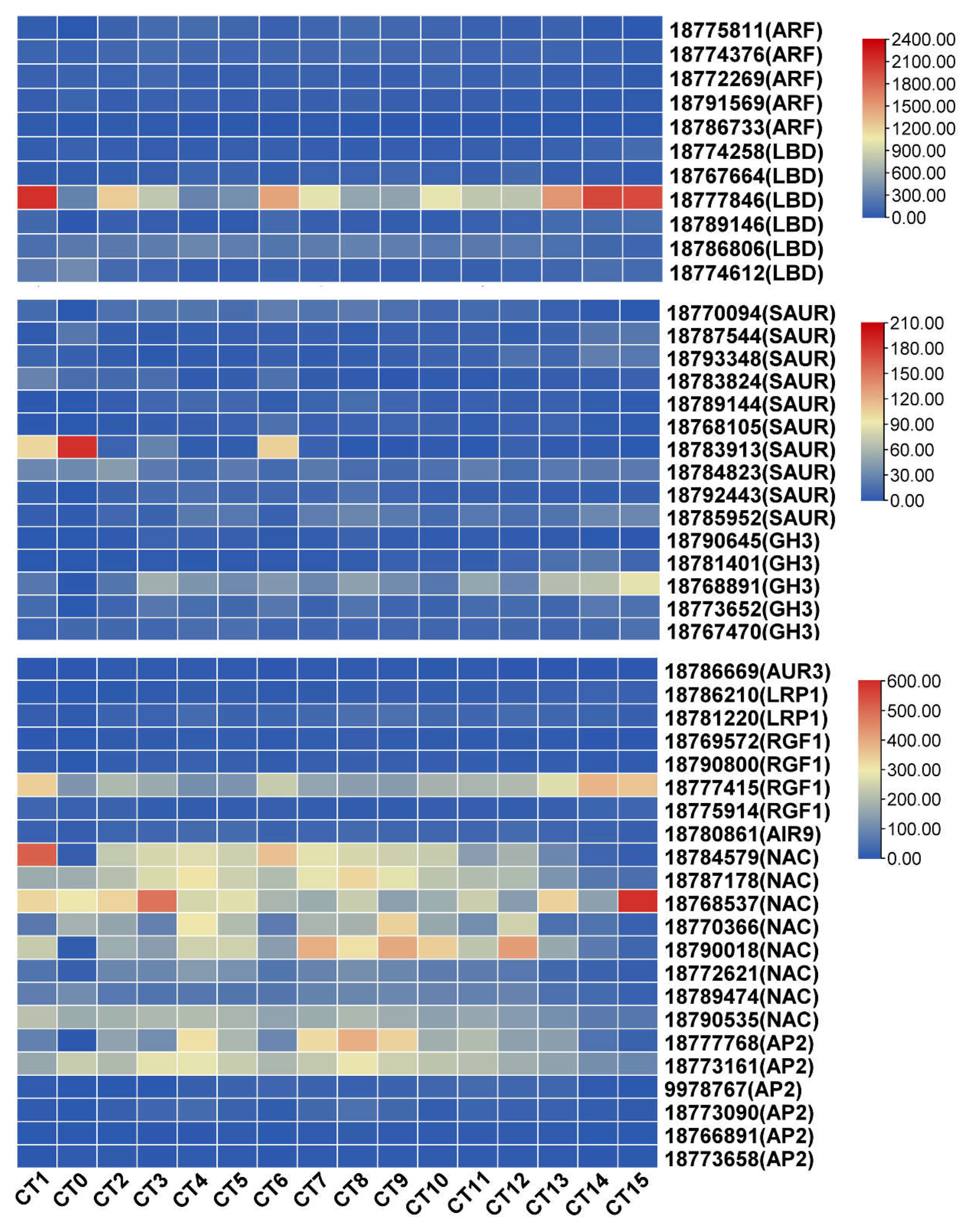

Identify DEGs Involved in the Formation of AR-Related Pathways

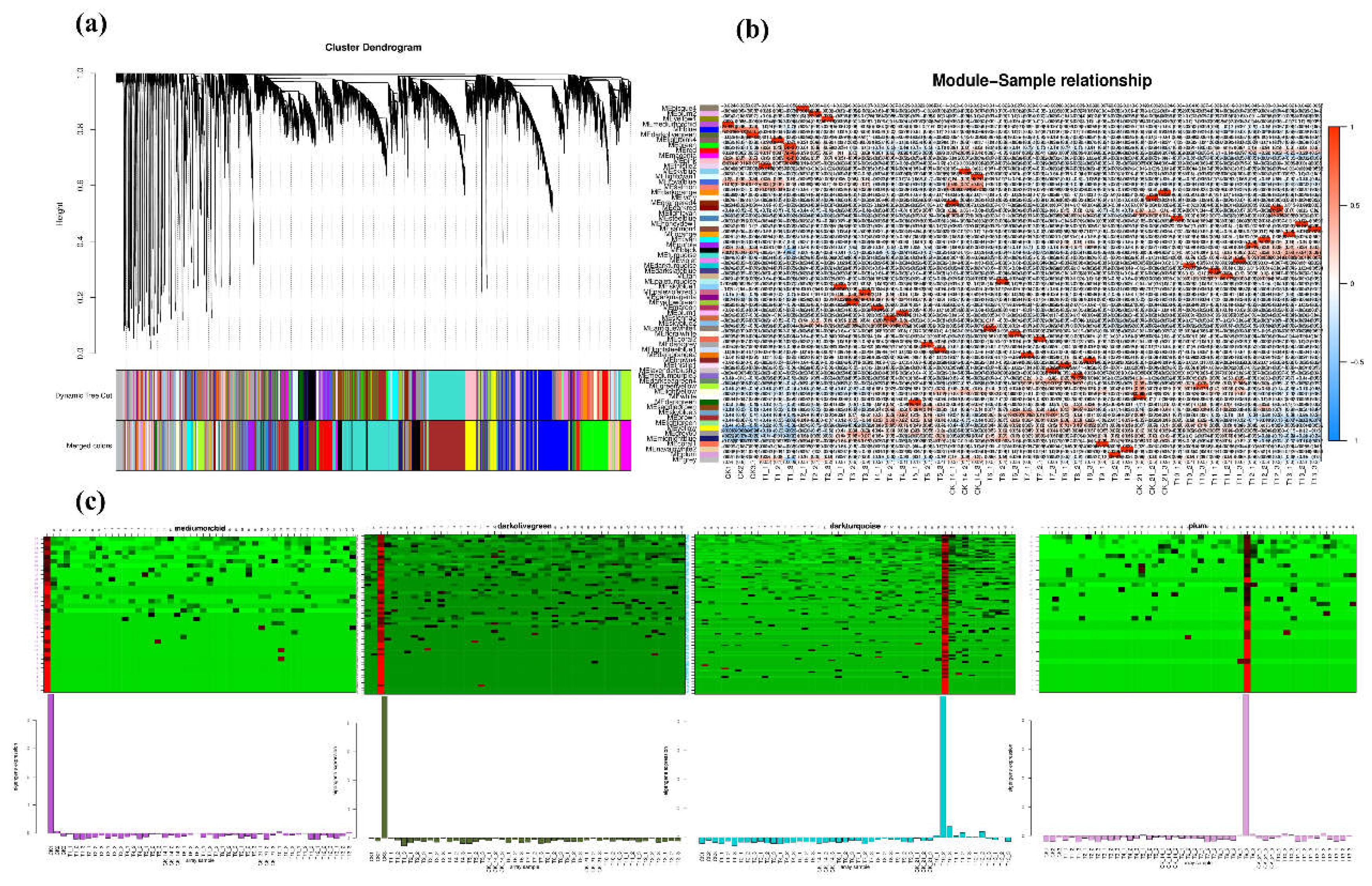

Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| (AR) | adventitious root |

| (IAA) | indole-3-acetic acid |

| (GH3) | Gretchen Hagen3 |

| (SAUR) | Small Auxin Up RNA |

| (ARFs) | auxin-responsive factors |

| (LBD) | Lateral Organ Boundaries Domain |

| (LRP1) | Lateral Root Primordium 1 |

| (RGF) | Root Meristem Growth Factor |

| (AIR12) | Auxin-Induced in Roots 12 |

| (WGCNA) | Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis |

| (DEGs) | differentially expressed genes |

| (FPKM) | Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads |

| (PCA) | Principal Component Analysis |

| (GO) | Gene Ontology |

| (KEGG) | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

References

- Sabbadini, S.; Pandolfini, T.; Girolomini, L.; Molesini, B.; Navacchi, O. Peach (Prunus persica L.). Methods Mol. Biol. 2015, 1224, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adaskaveg, J.E.; Schnabel, G.; Förster, H. The peach: botany, production and uses; The peach: botany, production and uses.: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lavania, U.C.; Srivastava, S.; Lavania, S. Ploidy-mediated reduced segregation facilitates fixation of heterozygosity in the aromatic grass, Cymbopogon martinii (Roxb.). J. Hered. 2010, 101, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, C.W. Plant grafting: insights into tissue regeneration. Regeneration 2017, 4, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, M.; Augstein, F.; Kareem, A.; Melnyk, C.W. Plant grafting: Molecular mechanisms and applications. Mol. Plant 2024, 17, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druege, U.; Hilo, A.; Pérez-Pérez, J.M.; Klopotek, Y.; Acosta, M.; Shahinnia, F.; Zerche, S.; Franken, P.; Hajirezaei, M.R. Molecular and physiological control of adventitious rooting in cuttings: phytohormone action meets resource allocation. Ann. Bot. 2019, 123, 929–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druege, U.; Franken, P.; Hajirezaei, M.R. Plant Hormone Homeostasis, Signaling, and Function during Adventitious Root Formation in Cuttings. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahkami, A.H. Systems biology of root development in Populus: Review and perspectives. Plant Sci. : Int. J. Exp. Plant Biol. 2023, 335, 111818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman; TG; Nyczepir; AP; Myers; SC. Performance of peach rootstocks propagated as seedlings vs. cuttings. Acta Hortic 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tsipouridis, C.; Thomidis, T.; Michailides, Z. Influence of some external factors on the rooting of GF677, peach and nectarine shoot hardwood cuttings. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 2005, 45, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsipouridis, G.; Thomidis, T.; Bladenopoulou, S. Seasonal variation in sprouting of GF677 peach × almond (Prunus persica × Prunus aygdalus) hybrid root cuttings. New Zealand J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2006, 34, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.; Mezzetti, B.; Sabbadini, O.N.B. In vitro regeneration, via organogenesis, from leaves of the peach rootstock GF677 (P. persica × P. amygdalus). Acta Hortic. 2023, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloccia, A.; Fattorini, L.; Della Rovere, F.; Sofo, A.; D'Angeli, S.; Betti, C.; Falasca, G.; Altamura, M.M. Ethylene and auxin interaction in the control of adventitious rooting in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 6445–6458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilmoth, J.C.; Wang, S.; Tiwari, S.B.; Joshi, A.D.; Hagen, G.; Guilfoyle, T.J.; Alonso, J.M.; Ecker, J.R.; Reed, J.W. NPH4/ARF7 and ARF19 promote leaf expansion and auxin-induced lateral root formation. Plant J. 2005, 43, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xu, M.; Xuan, L.; Jiang, X.; Huang, M. Identification and expression analysis of twenty ARF genes in Populus. Gene 2014, 544, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.W.; Cho, C.; Pandey, S.K.; Park, Y.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, J. LBD16 and LBD18 acting downstream of ARF7 and ARF19 are involved in adventitious root formation in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Zheng, C.; Liu, R.; Song, A.; Zhang, Z.; Xin, J.; Jiang, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, F.; Fang, W.; et al. Chrysanthemum transcription factor CmLBD1 direct lateral root formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Gao, X.R.; Dai, Z.R.; Peng, K.; Jia, L.C.; Wu, Y.K.; Liu, Q.C.; Zhai, H.; Gao, S.P.; et al. IbMYB73 targets abscisic acid-responsive IbGER5 to regulate root growth and stress tolerance in sweet potato. Plant Physiol. 2024, 194, 787–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Qiu, L.; Yang, D.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, Y.; Meng, R.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, S. Genome-wide identification of the SAUR gene family and screening for SmSAURs involved in root development in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Plant Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wen, S.S.; Sun, T.T.; Wang, R.; Zuo, W.T.; Yang, T.; Wang, C.; Hu, J.J.; Lu, M.Z.; Wang, L.Q. PagWOX11/12a positively regulates the PagSAUR36 gene that enhances adventitious root development in poplar. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 7298–7311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, J.; Xin, M.; Qin, Z. Genome-Wide Identification and Functional Analysis of the Roles of SAUR Gene Family Members in the Promotion of Cucumber Root Expansion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staswick, P.E.; Serban, B.; Rowe, M.; Tiryaki, I.; Maldonado, M.T.; Maldonado, M.C.; Suza, W. Characterization of an Arabidopsis enzyme family that conjugates amino acids to indole-3-acetic acid. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Yadav, S.; Singh, A.; Mahima, M.; Singh, A.; Gautam, V.; Sarkar, A.K. Auxin signaling modulates LATERAL ROOT PRIMORDIUM1 (LRP1) expression during lateral root development in Arabidopsis. Plant J. : Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 101, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, H. Root meristem growth factor RGF, a sulfated peptide hormone in plants. Peptides 2021, 142, 170556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, S.W.; Todd, C.D. Arabidopsis AIR12 influences root development. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2015, 21, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, Y.; Qian, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, T.; Chao, Y.; Zhao, Y. Uncovering early transcriptional regulation during adventitious root formation in Medicago sativa. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedländer, M.R.; Mackowiak, S.D.; Li, N.; Chen, W.; Rajewsky, N. miRDeep2 accurately identifies known and hundreds of novel microRNA genes in seven animal clades. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.A.; Pertea, G.; Mortazavi, A.; Kwan, G.; van Baren, M.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Wold, B.J.; Pachter, L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, G.Y.; Xie, Y.H.; Li, W.F.; Li, K.P.; Sun, C.; Wang, H.M.; Sun, X.M. LkARF7 and LkARF19 overexpression promote adventitious root formation in a heterologous poplar model by positively regulating LkBBM1. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirolinko, C.; Hobecker, K.; Cueva, M.; Botto, F.; Christ, A.; Niebel, A.; Ariel, F.; Blanco, F.A.; Crespi, M.; Zanetti, M.E. A lateral organ boundaries domain transcription factor acts downstream of the auxin response factor 2 to control nodulation and root architecture in Medicago truncatula. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 2746–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, A.; Du, T.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Hou, F. A Small Auxin-Up RNA Gene, IbSAUR36, Regulates Adventitious Root Development in Transgenic Sweet Potato. Genes 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, A.; Sánchez-García, A.B.; Albacete, A.; González-Bayón, R.; Justamante, M.S.; Ibáñez, S.; Acosta, M.; Pérez-Pérez, J.M. Enhanced Conjugation of Auxin by GH3 Enzymes Leads to Poor Adventitious Rooting in Carnation Stem Cuttings. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wang, N.; Ji, D.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Lyu, M.; You, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. A GmSIN1/GmNCED3s/GmRbohBs Feed-Forward Loop Acts as a Signal Amplifier That Regulates Root Growth in Soybean Exposed to Salt Stress. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 2107–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyomarc'h, S.; Boutté, Y.; Laplaze, L. AP2/ERF transcription factors orchestrate very long chain fatty acid biosynthesis during Arabidopsis lateral root development. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannoud, F.; Bellini, C. Adventitious Rooting in Populus Species: Update and Perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 668837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilo, A.; Shahinnia, F.; Druege, U.; Franken, P.; Melzer, M.; Rutten, T.; von Wirén, N.; Hajirezaei, M.R. A specific role of iron in promoting meristematic cell division during adventitious root formation. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 4233–4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overvoorde, P.; Fukaki, H.; Beeckman, T. Auxin control of root development. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, a001537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, K.; Ruan, L.; Wang, L.; Cheng, H. Auxin-Induced Adventitious Root Formation in Nodal Cuttings of Camellia sinensis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Tayengwa, R.; Cheng, Z.M.; Peer, W.A.; Murphy, A.S.; Zhao, M. Auxin regulates adventitious root formation in tomato cuttings. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Sauter, M. Polar Auxin Transport Determines Adventitious Root Emergence and Growth in Rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Dong, Z.; Zheng, X.; Song, S.; Jiao, J.; Wang, M.; Song, C. Auxin and Its Interaction With Ethylene Control Adventitious Root Formation and Development in Apple Rootstock. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 574881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Li, Y.H.; Wu, J.Y.; Chen, Q.Z.; Huang, X.; Chen, Y.F.; Huang, X.L. Over-expression of mango (Mangifera indica L.) MiARF2 inhibits root and hypocotyl growth of Arabidopsis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011, 38, 3189–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Yu, J.; Ge, Y.; Qin, P.; Xu, L. Pivotal role of LBD16 in root and root-like organ initiation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. : CMLS 2018, 75, 3329–3338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, L.; Mongelard, G.; Floková, K.; Pacurar, D.I.; Novák, O.; Staswick, P.; Kowalczyk, M.; Pacurar, M.; Demailly, H.; Geiss, G.; et al. Auxin controls Arabidopsis adventitious root initiation by regulating jasmonic acid homeostasis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2515–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuruzzaman, M.; Cao, H.; Xiu, H.; Luo, T.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Luo, J.; Luo, Z. Transcriptomics-based identification of WRKY genes and characterization of a salt and hormone-responsive PgWRKY1 gene in Panax ginseng. Acta Biochim. Et Biophys. Sin. 2016, 48, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Nvsvrot, T.; Huang, L.; Cai, G.; Ding, Y.; Ren, W.; Wang, N. The transcription factor WRKY75 regulates the development of adventitious roots, lateral buds and callus by modulating hydrogen peroxide content in poplar. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 1483–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neogy, A.; Garg, T.; Kumar, A.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Singh, H.; Singh, U.; Singh, Z.; Prasad, K.; Jain, M.; Yadav, S.R. Genome-Wide Transcript Profiling Reveals an Auxin-Responsive Transcription Factor, OsAP2/ERF-40, Promoting Rice Adventitious Root Development. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 2343–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trupiano, D.; Yordanov, Y.; Regan, S.; Meilan, R.; Tschaplinski, T.; Scippa, G.S.; Busov, V. Identification, characterization of an AP2/ERF transcription factor that promotes adventitious, lateral root formation in Populus. Planta 2013, 238, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Frugis, G.; Colgan, D.; Chua, N.H. Arabidopsis NAC1 transduces auxin signal downstream of TIR1 to promote lateral root development. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 3024–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cheng, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, G.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L. Auxin-Independent NAC Pathway Acts in Response to Explant-Specific Wounding and Promotes Root Tip Emergence during de Novo Root Organogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 2136–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Ge, X.; Wei, H.; Zhang, M.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hu, J. PsPRE1 is a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor that confers enhanced root growth and tolerance to salt stress in poplar. For. Res. 2023, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xie, Q.; Chen, G.; Chen, X.; Hu, Z. Overexpression of SlPRE3 alters the plant morphologies in Solanum lycopersicum. Plant Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 1907–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Cao, P.; Xiao, Z.; Zhan, C.; Liu, M.; Nvsvrot, T.; Wang, N. The bZIP53-IAA4 module inhibits adventitious root development in Populus. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 3485–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q. PagMYB180 regulates adventitious rooting via a ROS/PCD-dependent pathway in poplar. Plant Sci. 2024, 346, 112115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Sohail, H.; Sharif, R.; Hu, Q.; Song, J.; Qi, X.; Chen, X.; Xu, X. Cucumber JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN 6 interaction with transcription factor MYB6 impairs waterlogging-triggered adventitious rooting. Plant Physiol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| sample | Total raw reads | Total clean reads | Mapped to genome | Q20 (%) | Q30 (%) |

| CK2 | 47896372 | 47054904 | 43367878(92.24%) | 98.71 | 96.03 |

| CK3 | 49075334 | 47491586 | 43524528(92.5%) | 98.7 | 96.03 |

| T1_1 | 46112880 | 45301060 | 43579725(91.76%) | 98.87 | 96.52 |

| T1_2 | 46513084 | 45726832 | 41701330(92.05%) | 98.32 | 94.97 |

| T1_3 | 48004348 | 46895460 | 41989079(91.83%) | 98.65 | 96.02 |

| T2_1 | 46008382 | 44923344 | 40816357(87.04%) | 98.72 | 96.07 |

| T2_2 | 41222534 | 40417280 | 41368746(92.09%) | 98.29 | 94.89 |

| T2_3 | 47780536 | 46894280 | 37188481(92.01%) | 98.64 | 95.84 |

| T3_1 | 49306966 | 48448074 | 43239306(92.21%) | 98.75 | 96.15 |

| T3_2 | 43377072 | 42720960 | 44320546(91.48%) | 98.59 | 95.71 |

| T3_3 | 47114448 | 46115510 | 39675545(92.87%) | 98.73 | 96.07 |

| T4_1 | 47472882 | 46615394 | 42722806(92.64%) | 98.59 | 95.7 |

| T4_2 | 41419734 | 40721474 | 42620563(91.43%) | 98.63 | 95.82 |

| T4_3 | 46931744 | 46132170 | 37493665(92.07%) | 98.58 | 95.7 |

| T5_1 | 42571156 | 41766276 | 42280235(91.65%) | 98.68 | 95.94 |

| T5_2 | 40391866 | 39734218 | 38366128(91.86%) | 98.51 | 95.45 |

| T5_3 | 47855332 | 46983982 | 36152071(90.98%) | 98.62 | 95.77 |

| CK_14_1 | 45846246 | 44855450 | 42885665(91.28%) | 98.64 | 95.84 |

| CK_14_2 | 44378214 | 43377076 | 40900606(91.18%) | 98.33 | 94.99 |

| CK_14_3 | 49966392 | 48015634 | 39447161(90.94%) | 98.84 | 96.46 |

| T6_1 | 44398656 | 43761882 | 43531783(90.66%) | 98.66 | 95.9 |

| T6_2 | 47909356 | 46768074 | 39847771(91.06%) | 98.67 | 95.93 |

| T6_3 | 45331290 | 43896236 | 42655348(91.21%) | 98.66 | 95.91 |

| T7_1 | 40947492 | 40247198 | 40036895(91.21%) | 98.6 | 95.75 |

| T7_2 | 40677260 | 39979808 | 36715915(91.23%) | 98.68 | 95.97 |

| T7_3 | 40433808 | 39794474 | 36710211(91.82%) | 98.57 | 95.6 |

| T8_1 | 47231542 | 46321786 | 36550697(91.85%) | 98.62 | 95.79 |

| T8_2 | 41345866 | 40678696 | 42117224(90.92%) | 98.62 | 95.79 |

| T8_3 | 44547176 | 43796224 | 37076433(91.14%) | 98.63 | 95.83 |

| T9_1 | 44651492 | 43904988 | 39825654(90.93%) | 98.68 | 95.96 |

| T9_2 | 43849526 | 43155586 | 40171431(91.5%) | 98.66 | 95.9 |

| T9_3 | 39875306 | 39036404 | 39536447(91.61%) | 98.55 | 95.59 |

| CK_21_1 | 46027828 | 45074462 | 35861001(91.87%) | 98.64 | 95.85 |

| CK_21_2 | 47123826 | 46200950 | 40851282(90.63%) | 98.59 | 95.7 |

| CK_21_3 | 40978358 | 39970156 | 42096191(91.12%) | 98.31 | 94.95 |

| T10_1 | 48580358 | 47360950 | 36344705(90.93%) | 98.67 | 95.93 |

| T10_2 | 47158522 | 46329548 | 43021908(90.84%) | 98.61 | 95.8 |

| T10_3 | 49484862 | 48556220 | 42013549(90.68%) | 98.56 | 95.62 |

| T11_1 | 48290834 | 47349840 | 44159009(90.94%) | 98.67 | 95.93 |

| T11_2 | 48314980 | 47500624 | 43256047(91.35%) | 98.49 | 95.38 |

| T11_3 | 46036442 | 45205652 | 42973556(90.47%) | 98.65 | 95.87 |

| T12_1 | 42609072 | 41682398 | 41274112(91.3%) | 98.65 | 95.88 |

| T12_2 | 48868252 | 47932620 | 36962679(88.68%) | 98.59 | 95.74 |

| T12_3 | 41867310 | 41154606 | 40140961(83.74%) | 98.51 | 95.46 |

| T13_1 | 47484014 | 46618360 | 37344121(90.74%) | 98.71 | 96.03 |

| T13_2 | 48005162 | 46647020 | 41306853(88.61%) | 98.66 | 95.9 |

| T13_3 | 46150870 | 44995606 | 41825243(89.66%) | 98.7 | 96 |

| Total | 2185,245,500 | 2141129916 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).