Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

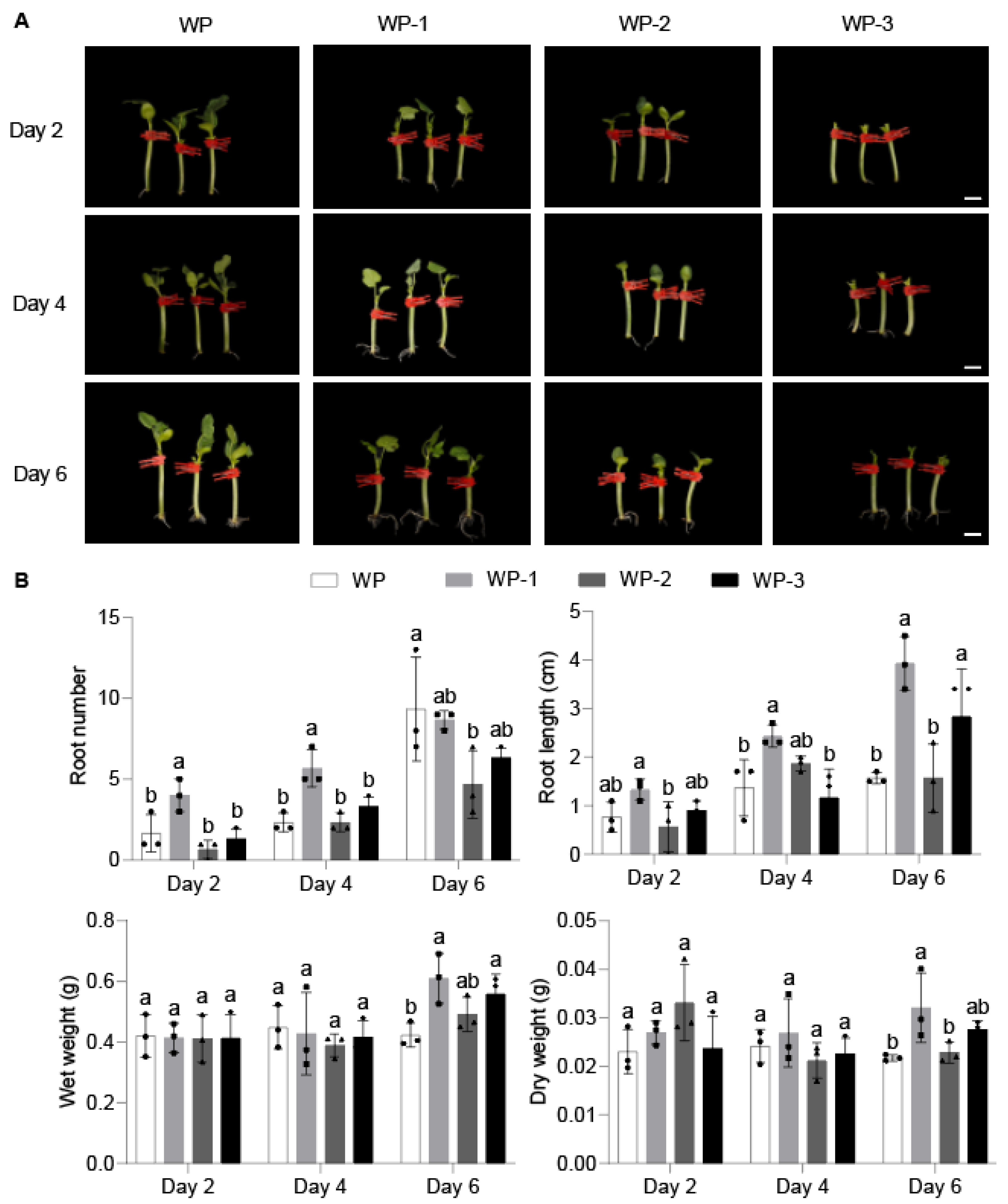

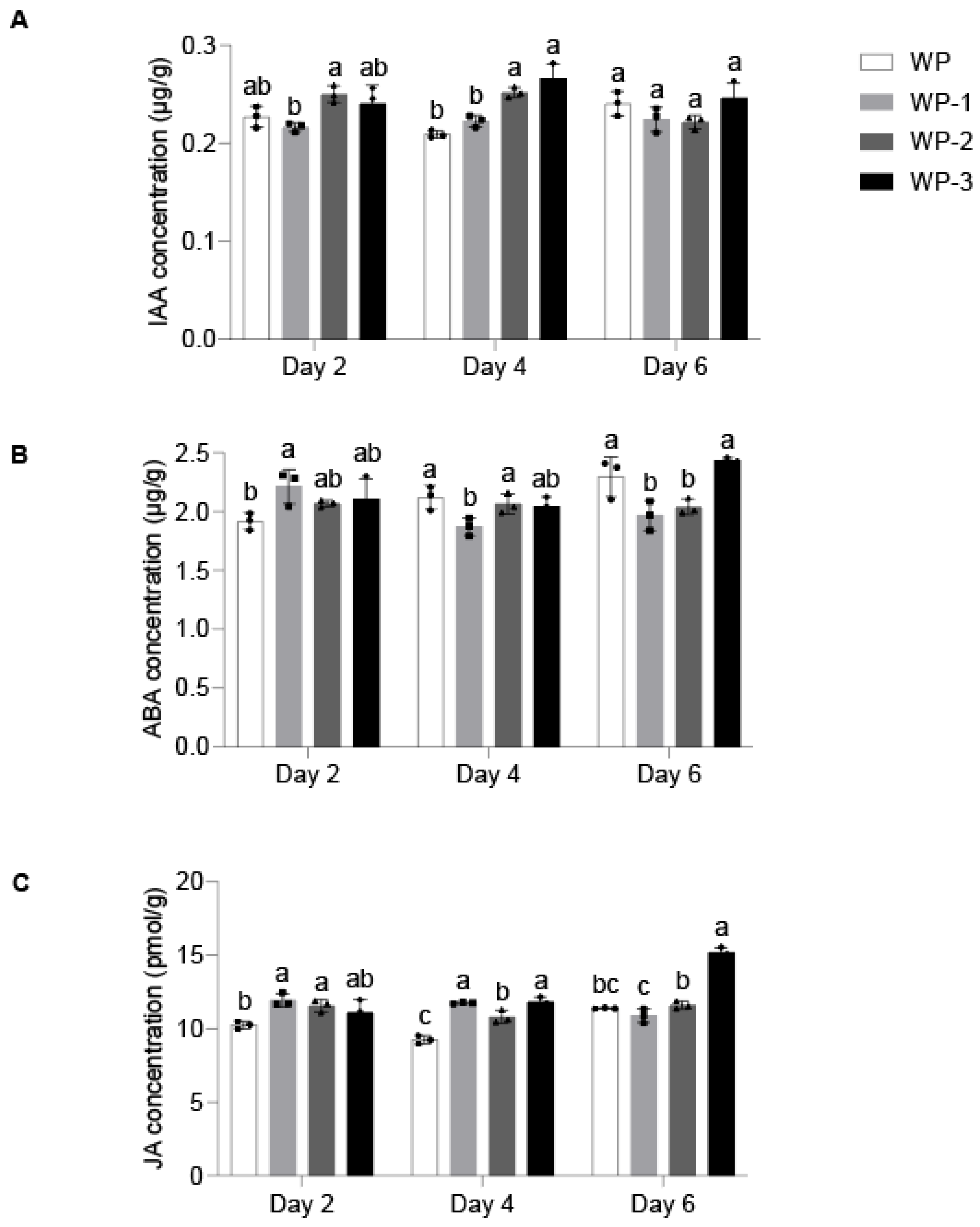

2.1. Morphological Changes and Endogenous Hormone Response During AR Formation

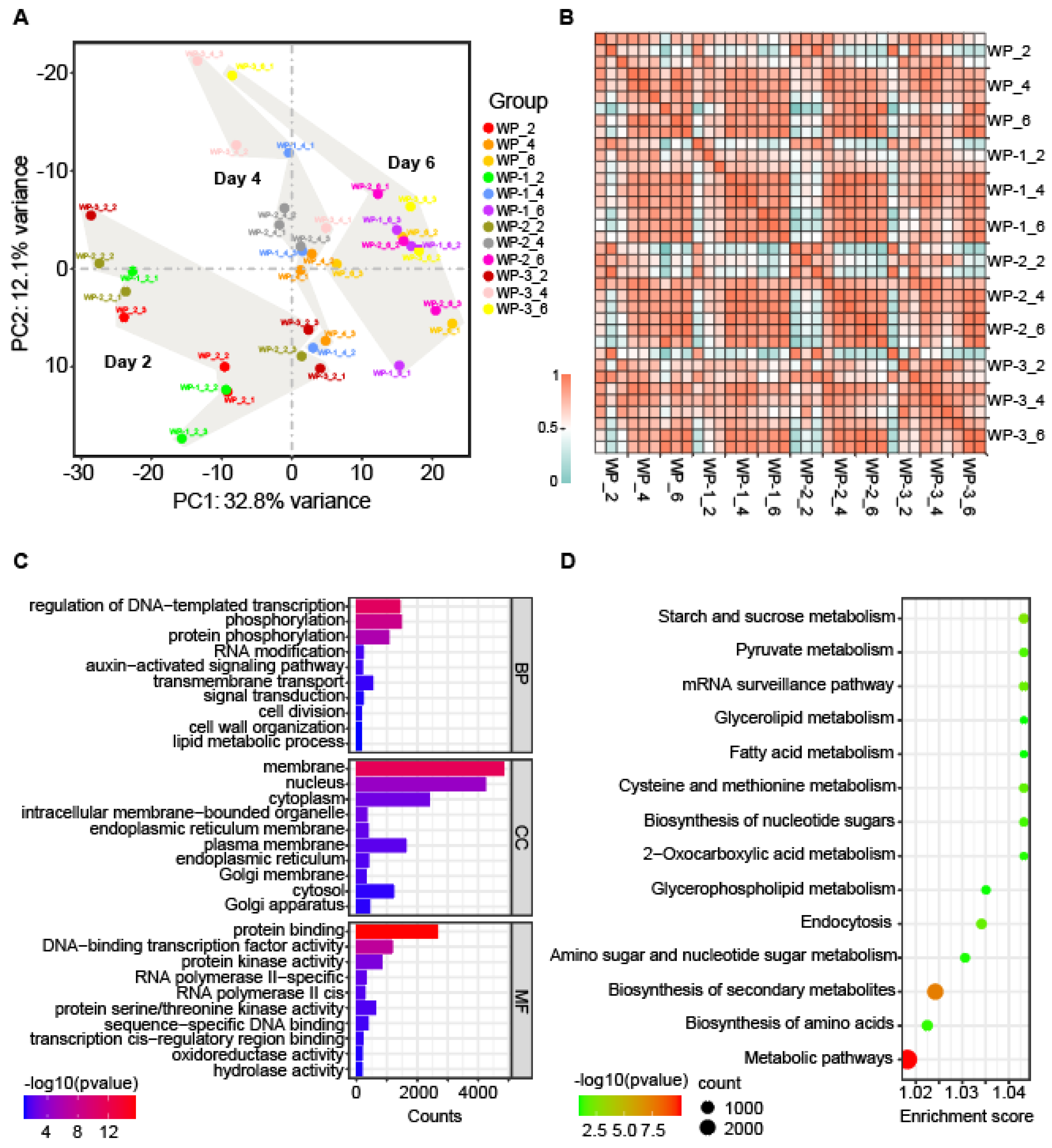

2.2. The Transcriptional Landscape During AR Formation

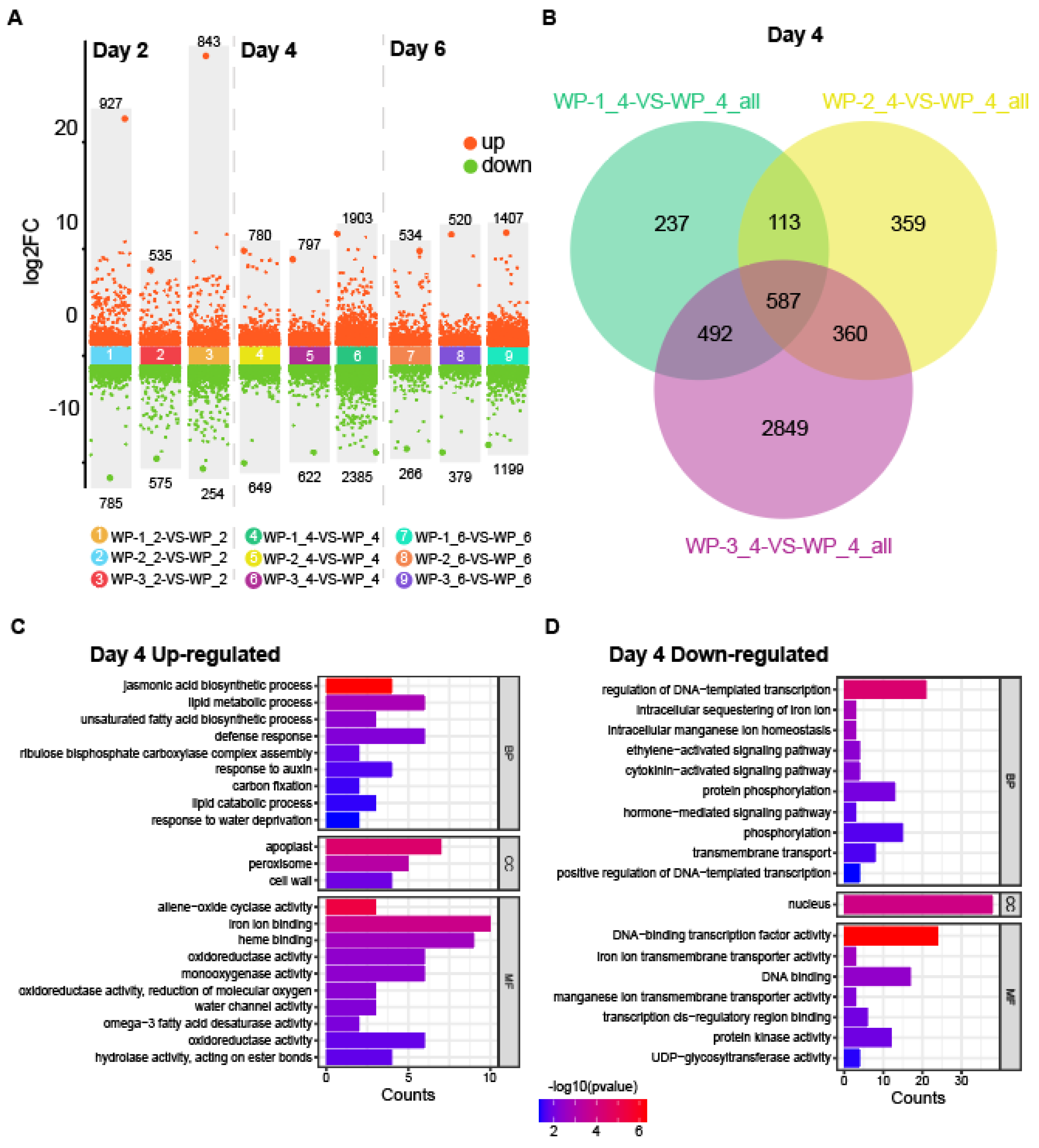

2.3. Common Transcriptome Regulation in the AR Development Process

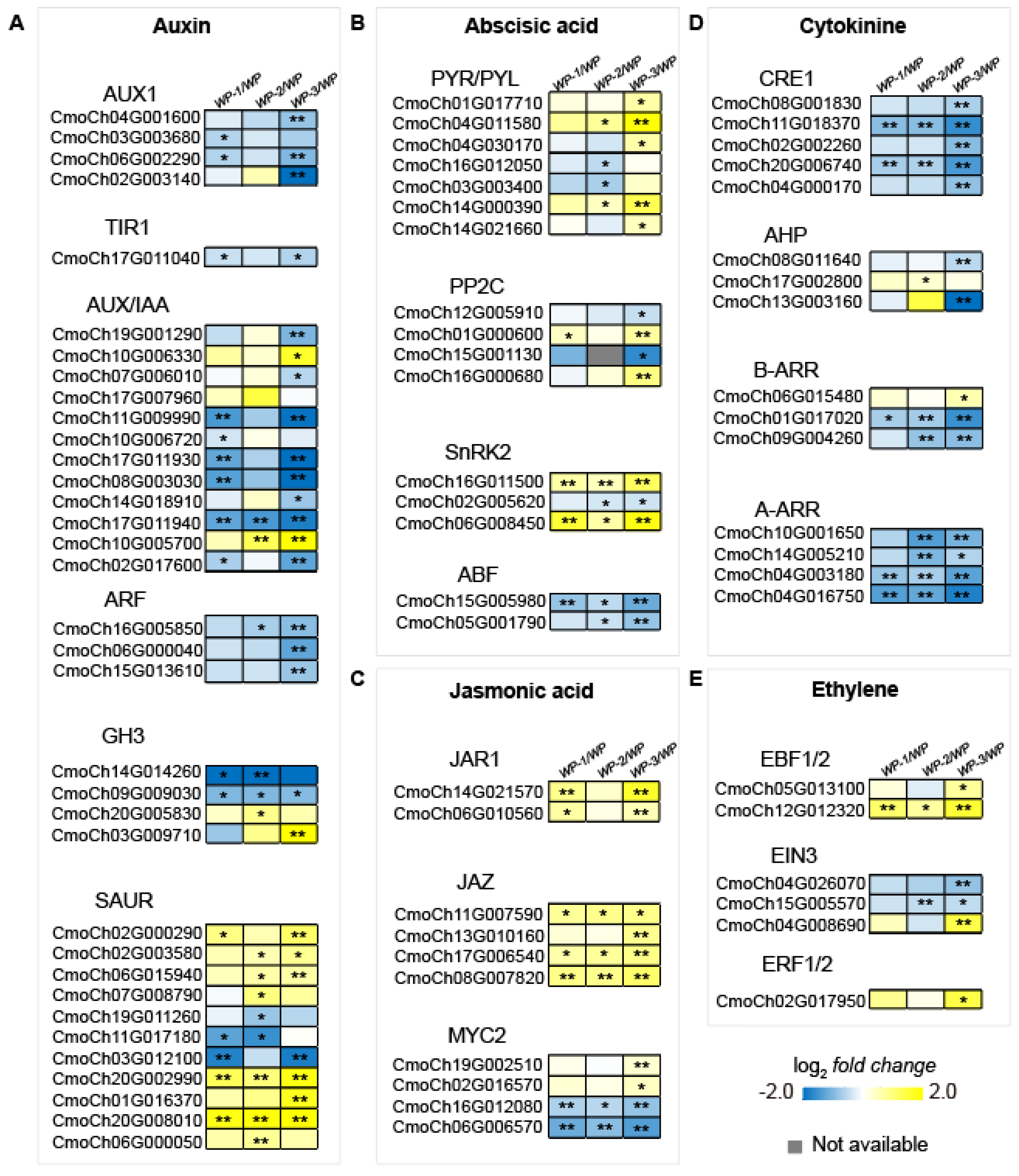

2.4. Activated Phytohormone Signaling Pathways During AR Formation

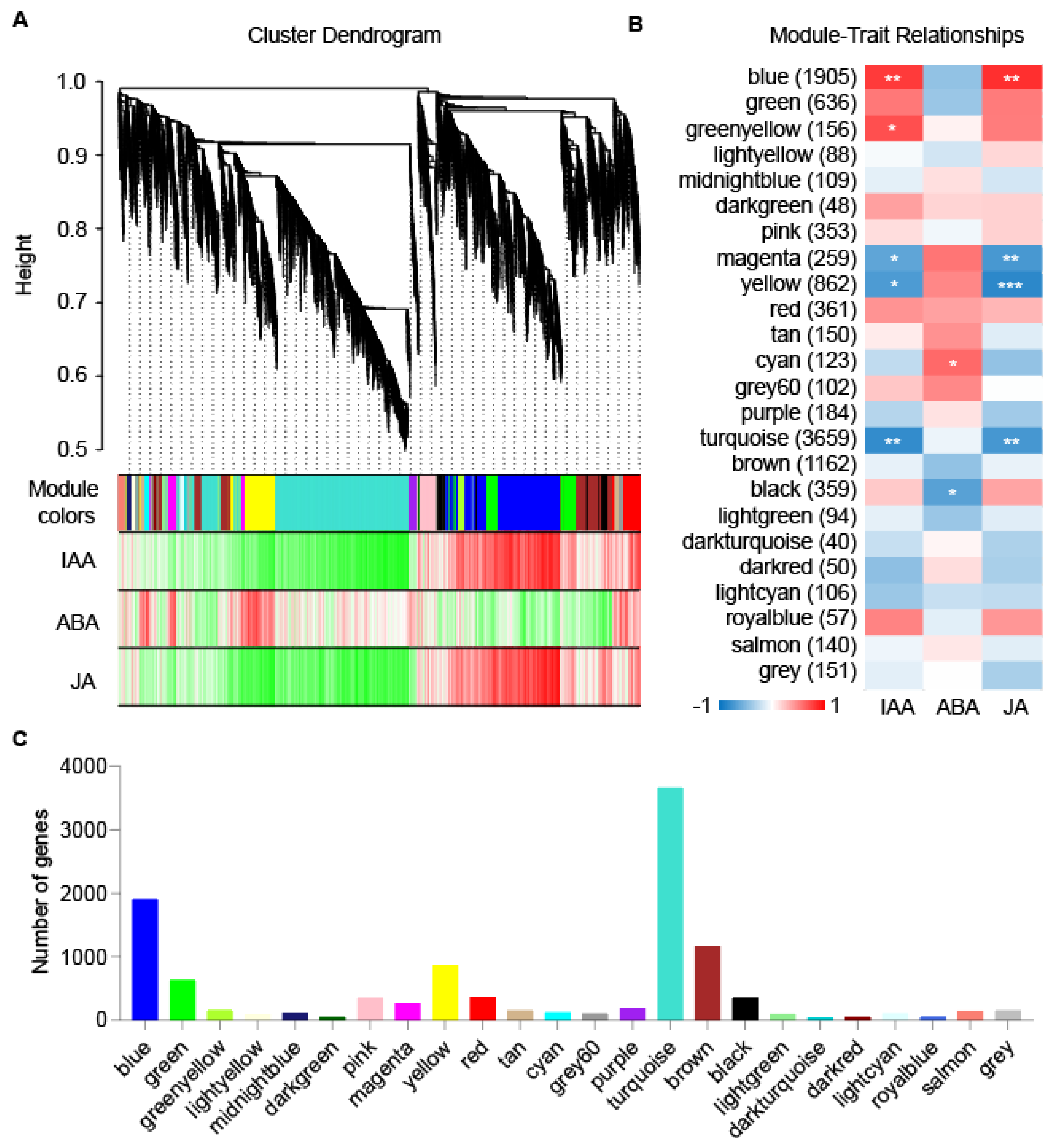

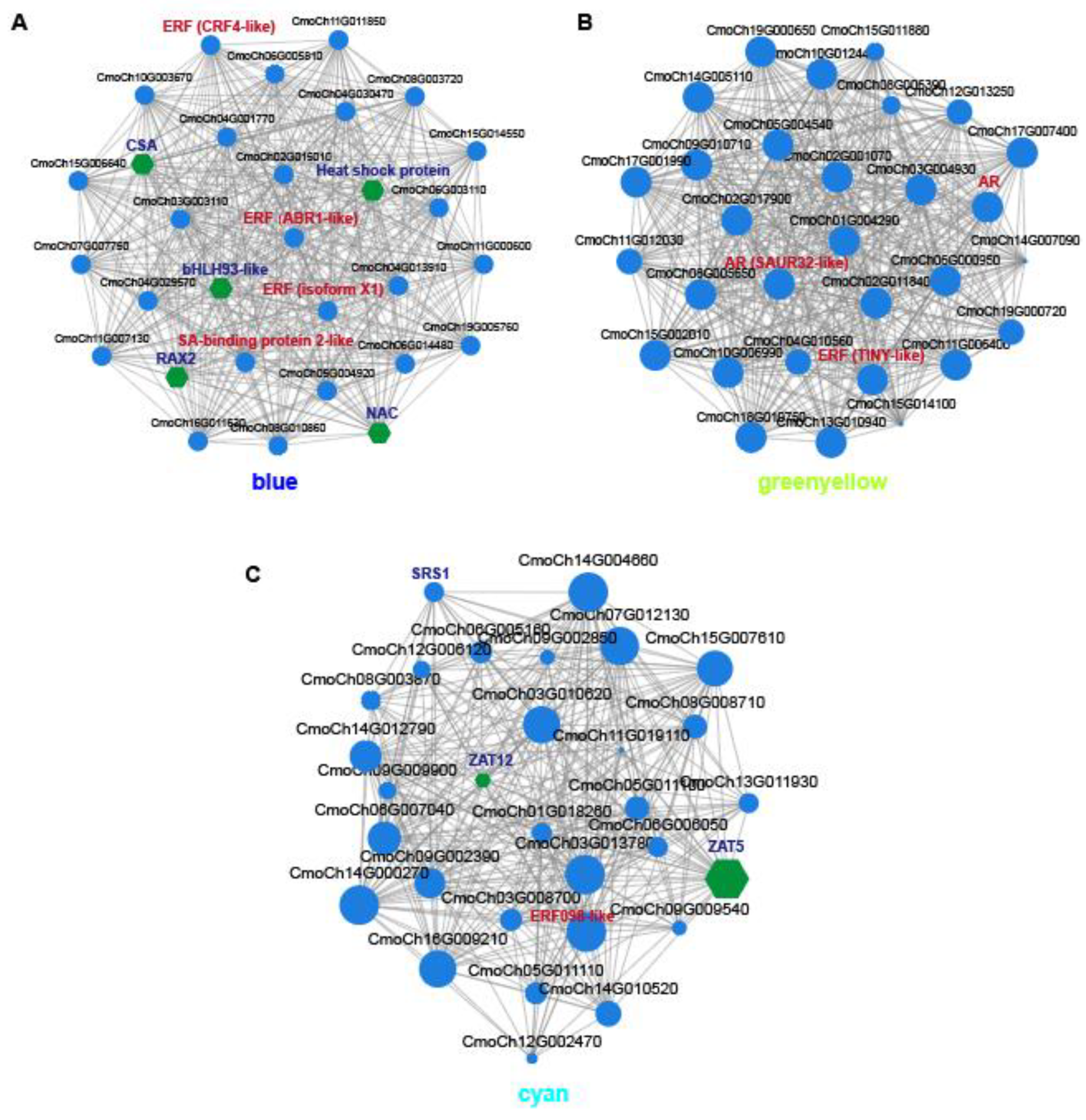

2.5. Key Modules and Candidate Genes Associated with AR Formation

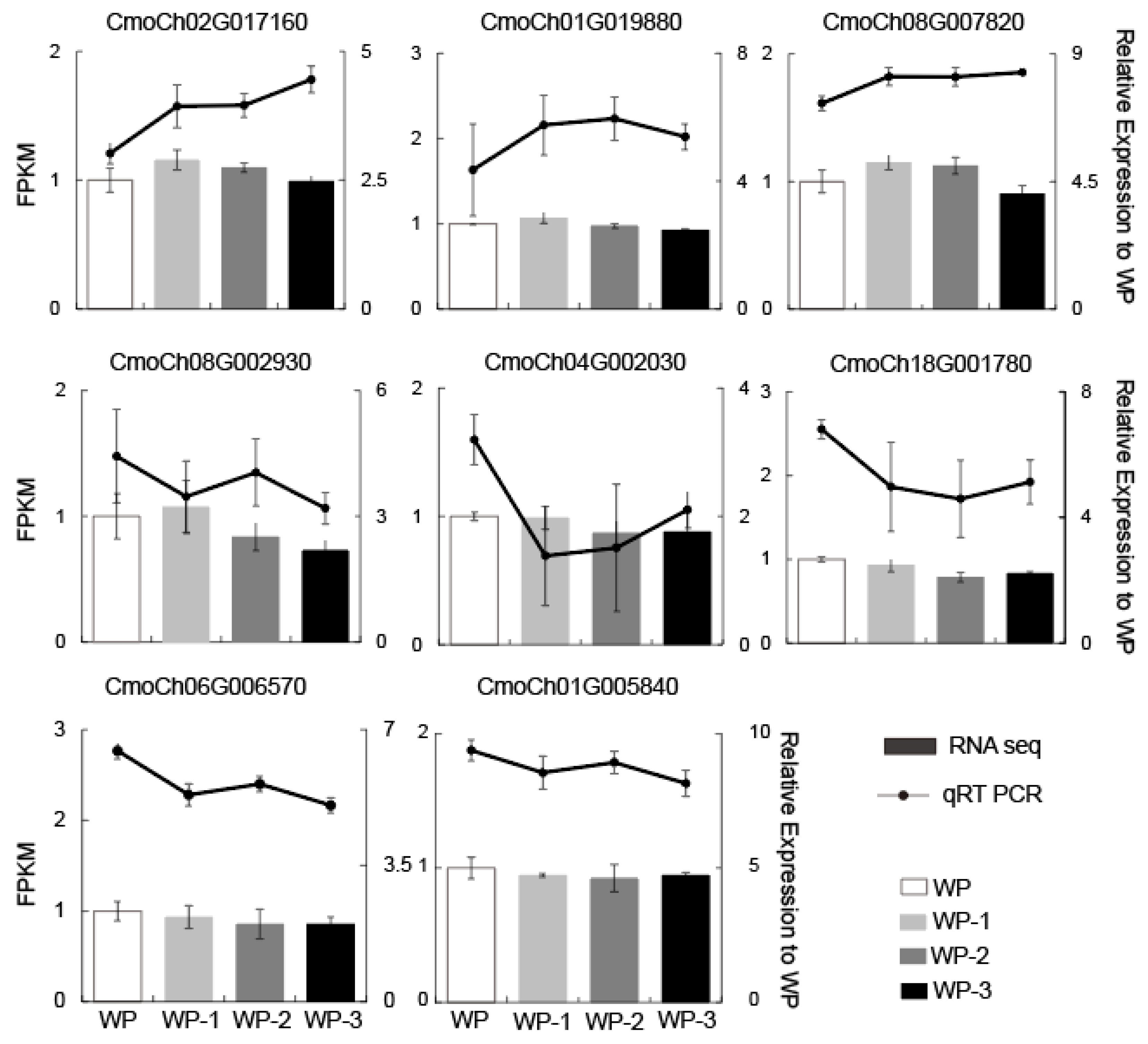

2.6. Confirmation of Transcriptome Data Through qRT-PCR

3. Discussion

3.1. Unveiling the Role of Scions in the Coordinated Regulation of AR Development by Phytohormones

3.2. The Effect of Transcription Factors on AR Development During Scion Rootstock Interaction

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

4.2. Determination of Endogenous Hormone Content

4.3. Total RNA Deep Sequencing

4.4. Differential Expression Analysis and Functional Enrichment

4.5. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis

4.6. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR Validation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARs | Adventitious Roots |

| IAA | Indole-3-Acetic Acid |

| ABA | Abscisic Acid |

| JA | Jasmonic Acid |

| DEGs | Differentially Expressed Genes |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| WGCNA | Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis |

References

- Colla, G.; Rouphael, Y.; Cardarelli, M.; Salerno, A.; Rea, E. The effectiveness of grafting to improve alkalinity tolerance in watermelon. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2010, 68, (3), 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadur, A.; Singh, P. M.; Rai, N.; Singh, A. K.; Singh, A. K.; Karkute, S. G.; Behera, T. K. Grafting in vegetables to improve abiotic stress tolerance, yield and quality. The Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Ma, S.; Gao, L.; Qu, M.; Tian, Y. Enhancing root regeneration and nutrient absorption in double-rootcutting grafted seedlings by regulating light intensity and photoperiod. Scientia Horticulturae 2020, 264, 109192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Bao, E.; Xia, L.; Bian, Z.; Cao, K. Additional far-red light promotes adventitious rooting of double-root-cutting grafted watermelon seedlings. Horticultural Plant Journal 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mhimdi, M.; Pérez-Pérez, J. M. Understanding of Adventitious Root Formation: What Can We Learn From Comparative Genetics? FRONTIERS IN PLANT SCIENCE 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonin, M.; Bergougnoux, V.; Nguyen, T. D.; Gantet, P.; Champion, A. What Makes Adventitious Roots? PLANTS-BASEL 2019, 8, (7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S. W. Molecular Bases for the Regulation of Adventitious Root Generation in Plants. FRONTIERS IN PLANT SCIENCE 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H. W.; Li, W. Q.; Burritt, D. J.; Tian, H. T.; Zhang, H.; Liang, X. H.; Miao, Y. C.; Mostofa, M. G.; Tran, L. S. P. Strigolactones interact with other phytohormones to modulate plant root growth and development. CROP JOURNAL 2022, 10, (6), 1517–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Singh, D.; Saksena, H. B.; Sharma, M.; Tiwari, A.; Awasthi, P.; Botta, H. K.; Shukla, B. N.; Laxmi, A. Understanding the intricate web of phytohormone signalling in modulating root system architecture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, (11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betti, C.; Della Rovere, F.; Piacentini, D.; Fattorini, L.; Falasca, G.; Altamura, M. M. Jasmonates, ethylene and brassinosteroids control adventitious and lateral rooting as stress avoidance responses to heavy metals and metalloids. Biomolecules 2021, 11, (1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kevei, Z.; Larriba, E.; Romero-Bosquet, M. D.; Nicolás-Albujer, M.; Kurowski, T. J.; Mohareb, F.; Rickett, D.; Pérez-Pérez, J. M.; Thompson, A. J. Genes involved in auxin biosynthesis, transport and signalling underlie the extreme adventitious root phenotype of the tomato aer mutant. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, (4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J. R.; Fan, M.; Zhang, Q. Q.; Lue, G. Y.; Wu, X. L.; Gong, B. B.; Wang, Y. B.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, H. B. Transcriptome analysis reveals that auxin promotes strigolactone-induced adventitious root growth in the hypocotyl of melon seedlings. FRONTIERS IN PLANT SCIENCE 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattorini, L.; Hause, B.; Gutierrez, L.; Veloccia, A.; Della Rovere, F.; Piacentini, D.; Falasca, G.; Altamura, M. M. Jasmonate promotes auxin-induced adventitious rooting in dark-grown Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings and stem thin cell layers by a cross-talk with ethylene signalling and a modulation of xylogenesis. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, (1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattorini, L.; Veloccia, A.; Della Rovere, F.; D'Angeli, S.; Falasca, G.; Altamura, M. M. Indole-3-butyric acid promotes adventitious rooting in Arabidopsis thaliana thin cell layers by conversion into indole-3-acetic acid and stimulation of anthranilate synthase activity. BMC Plant Biol. 2017, 17, (1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, M.; Wei, L.; Liao, W. Identification of Key Genes during Ethylene-Induced Adventitious Root Development in Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, (21). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, J.; Wu, Y.; Jin, X.; Tang, Z.; Liao, W.; Dawuda, M. M.; Hu, L.; Xie, J.; Yu, J.; Calderón-Urrea, A. Proteomic analysis reveals key proteins involved in ethylene-induced adventitious root development in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). PeerJ 2021, 9.

- Lu, X. Y.; Chen, X. T.; Liu, J. Y.; Zheng, M.; Liang, H. Y. Integrating histology and phytohormone/metabolite profiling to understand rooting in yellow camellia cuttings. Plant Sci. (Amsterdam, Neth.) 2024, 346.

- Bagautdinova, Z. Z.; Omelyanchuk, N.; Tyapkin, A. V.; Kovrizhnykh, V. V.; Lavrekha, V. V.; Zemlyanskaya, E. V. Salicylic Acid in Root Growth and Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, (4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabregas, N.; Fernie, A. R. The interface of central metabolism with hormone signaling in plants. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, (23), R1535–R1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shi, M.; Tang, F.; Su, N.; Jin, F.; Pan, Y.; Chu, L.; Lu, M.; Shu, W.; Li, J. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Hormone Signalling Coexpression Pathways Involved in Adventitious Root Formation in Populus. Forests 2023, 14, (7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. M.; Ba, G.; Uwamungu, J. Y.; Ma, W. J.; Yang, L. N. Transcription Factor MdPLT1 Involved Adventitious Root Initiation in Apple Rootstocks. HORTICULTURAE 2024, 10, (1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M. M.; Tong, L.; Xie, L.; Wu, T.; Ghani, M. I.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Gao, X.; Tariq, L.; Zhang, D.; Shao, Y. Identification of the HAK gene family reveals their critical response to potassium regulation during adventitious root formation in apple rootstock. Horticultural Plant Journal 2023, 9, (1), 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J. P.; Niu, C. D.; Li, K.; Fan, L.; Liu, Z. M.; Li, S. H.; Ma, D. D.; Tahir, M. M.; Xing, L. B.; Zhao, C. P.; Ma, J. J.; An, N.; Han, M. Y.; Ren, X. L.; Zhang, D. Cytokinin-responsive MdTCP17 interacts with MdWOX11 to repress adventitious root primordium formation in apple rootstocks. Plant Cell 2023, 35, (4), 1202–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Langfelder, P.; Fuller, T.; Dong, J.; Li, A.; Hovarth, S. Weighted gene coexpression network analysis: state of the art. J. Biopharm. Stat. 2010, 20, (2), 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, S. S.; Miao, D. P.; Cui, H. Y.; Li, S. H.; Gu, Y. N.; Jia, R. R.; Leng, Y. F. Physiology and transcriptomic analysis of endogenous hormones regulating in vitro adventitious root formation in tree peony. SCIENTIA HORTICULTURAE 2023, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Tan, M.; Liu, X.; Mao, J.; Song, C.; Li, K.; Ma, J.; Xing, L.; Zhang, D.; Shao, J. The nutrient, hormone, and antioxidant status of scion affects the rootstock activity in apple. Scientia Horticulturae 2022, 302, 111157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cong, L.; Pang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhai, R.; Yang, C.; Xu, L. Dwarfing rootstock ‘Yunnan’Quince promoted fruit sugar accumulation by influencing assimilate flow and PbSWEET6 in pear scion. Horticulturae 2022, 8, (7), 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adem, M.; Sharma, L.; Shekhawat, G. S.; Šafranek, M.; Jásik, J. Auxin Signaling Transportation and Regulation during Adventitious Root Formation. Current Plant Biology 2024, 100385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, F.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Sun, L.; Bao, N.; Zhang, T.; Cui, C.-X.; Qiu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Jasmonate-mediated wound signalling promotes plant regeneration. Nature plants 2019, 5, (5), 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Yang, Z.; Xu, L. Dual roles of jasmonate in adventitious rooting. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, (20), 6808–6810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H. A.; Fernie, A. R. Evolutionary History of Plant Metabolism. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2021, 72, (Volume 72, 2021), 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidler, J. F.; Sträßer, K. Understanding nuclear mRNA export: Survival under stress. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, (19), 3681–3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Peng, D.; Wu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, T.; Wang, P.; Chen, X.; Jiang, S.; Li, X.; Cao, Z. Maize splicing-mediated mRNA surveillance impeded by sugarcane mosaic virus-coded pathogenic protein NIa-Pro. Science advances 2024, 10, (34), eadn3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Shi, C.; Liu, L.; Han, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Fu, W.; Gao, H.; Huang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yu, K. Majorbio Cloud 2024: Update single-cell and multiomics workflows. iMeta 2024, 3, (4), e217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, N.; Barber-Perez, N.; Pennington, B.; Cascant-Lopez, E.; Gregory, P. In Root system architecture in reciprocal grafts of apple rootstock-scion combinations, XXIX International Horticultural Congress on Horticulture: Sustaining Lives, Livelihoods and Landscapes (IHC2014): 1130, 2014; 2014; pp 409-414.

- Tandonnet, J. P.; Cookson, S.; Vivin, P.; Ollat, N. Scion genotype controls biomass allocation and root development in grafted grapevine. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2010, 16, (2), 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J. W. Cotyledon organogenesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, (11), 2917–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Verstraeten, I.; Trinh, H. K.; Lardon, R.; Schotte, S.; Olatunji, D.; Heugebaert, T.; Stevens, C.; Quareshy, M.; Napier, R. Chemical induction of hypocotyl rooting reveals extensive conservation of auxin signalling controlling lateral and adventitious root formation. New Phytol. 2023, 240, (5), 1883–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dob, A.; Lakehal, A.; Novak, O.; Bellini, C. Jasmonate inhibits adventitious root initiation through repression of CKX1 and activation of RAP2. 6L transcription factor in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, (20), 7107–7118. [Google Scholar]

- Lakehal, A.; Dob, A.; Rahneshan, Z.; Novák, O.; Escamez, S.; Alallaq, S.; Strnad, M.; Tuominen, H.; Bellini, C. ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR 115 integrates jasmonate and cytokinin signaling machineries to repress adventitious rooting in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2020, 228, (5), 1611–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Yan, B.; Sun, J.; Jia, P.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, X.; Chai, J.; Ren, Z.; Zheng, G.; Liu, H. Graft-union development: a delicate process that involves cell–cell communication between scion and stock for local auxin accumulation. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, (11), 4219–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Mitsuda, N.; Yoshizumi, T.; Horii, Y.; Oshima, Y.; Ohme-Takagi, M.; Matsui, M.; Kakimoto, T. Two types of bHLH transcription factor determine the competence of the pericycle for lateral root initiation. Nature Plants 2021, 7, (5), 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L.; Shiting, L.; Chen, Z.; Yuyan, H.; Minrong, Z.; Shuyan, L.; Libao, C. NnWOX1-1, NnWOX4-3, and NnWOX5-1 of lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn) promote root formation and enhance stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genomics 2023, 24, (1), 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vielba, J. M.; Rico, S.; Sevgin, N.; Castro-Camba, R.; Covelo, P.; Vidal, N.; Sánchez, C. Transcriptomics analysis reveals a putative role for hormone signaling and MADS-Box genes in mature chestnut shoots rooting recalcitrance. Plants 2022, 11, (24), 3486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tong, J.; Xiao, L.; Ruan, Y.; Liu, J.; Zeng, M.; Huang, H.; Wang, J.-W.; Xu, L. YUCCA-mediated auxin biogenesis is required for cell fate transition occurring during de novo root organogenesis in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, (14), 4273–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamhoff, D.; Marxen, A.; Acharya, B.; Grzelak, M.; Debener, T.; Winkelmann, T. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) analyses of early anatomical changes in rose adventitious root formation. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, (1), 25072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Cheng, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, G.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L. Auxin-independent NAC pathway acts in response to explant-specific wounding and promotes root tip emergence during de novo root organogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, (4), 2136–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Pak, S.; Yang, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, W.; Feng, H.; Yang, J.; Wei, H.; Li, C. Two high hierarchical regulators, PuMYB40 and PuWRKY75, control the low phosphorus driven adventitious root formation in Populus ussuriensis. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, (8), 1561–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nature methods 2015, 12, (4), 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertea, M.; Pertea, G. M.; Antonescu, C. M.; Chang, T.-C.; Mendell, J. T.; Salzberg, S. L. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, (3), 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Dewey, C. N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics 2011, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M. I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, C.; Mao, X.; Huang, J.; Ding, Y.; Wu, J.; Dong, S.; Kong, L.; Gao, G.; Li, C.-Y.; Wei, L. KOBAS 2.0: a web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, (suppl_2), W316–W322. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).