Submitted:

09 February 2025

Posted:

10 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

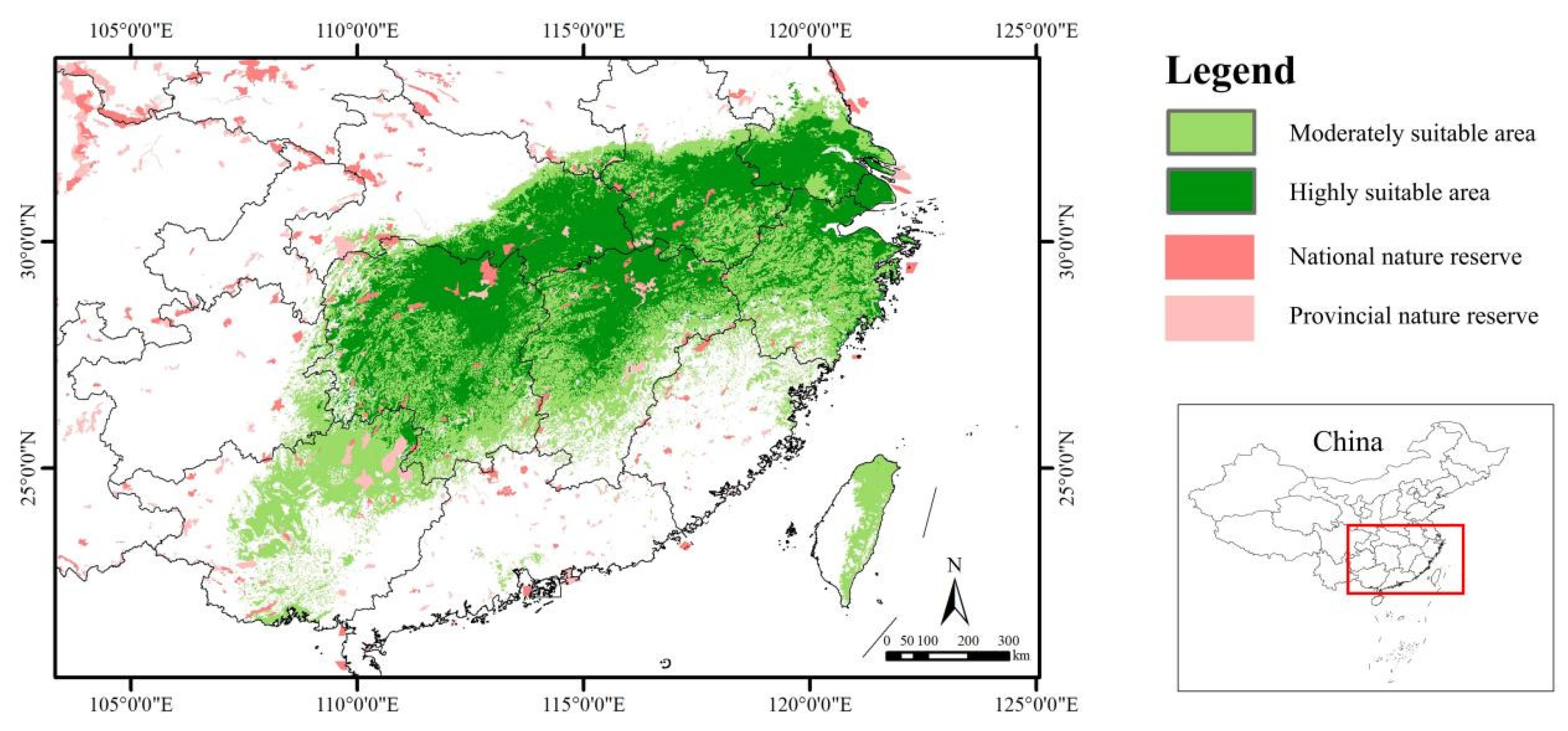

Sinojackia endemic to China, comprises five species, and each has restricted distribution but with high value in landscaping. However, how such species respond to climate change remains unclear. We selected S. xylocarpa as a representative, built an ensemble model in Biomod2 to forecast its potential distribution, identify its key influencing factors, and analyze its conservation gaps in China’s nature reserves. The four leading factors were precipitation of driest quarter, mean temperature of warmest quarter, precipitation of warmest quarter, and elevation. This species was mainly distributed in southeast China. Its suitable area was 69.72 × 104 km2, accounting for 6.26% of China’s total territory. Nevertheless, only 3.91% was located within national or provincial nature reserves. Under future climates, its suitable areas would averagely decrease by 10.97% compared to the current, with intensifying habitat fragmentation. Collectively, its centroid is expected to shift northeastward in the future. Therefore, our findings first demonstrate that future climate change may have an adverse effect on its distribution. We recommend conducting a supplementary investigation within the projected suitable range, and establishing new conservation sites for S. xylocarpa in China. Moreover, this study can provide valuable reference for conserving other endangered Sinojackia species under global warming.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

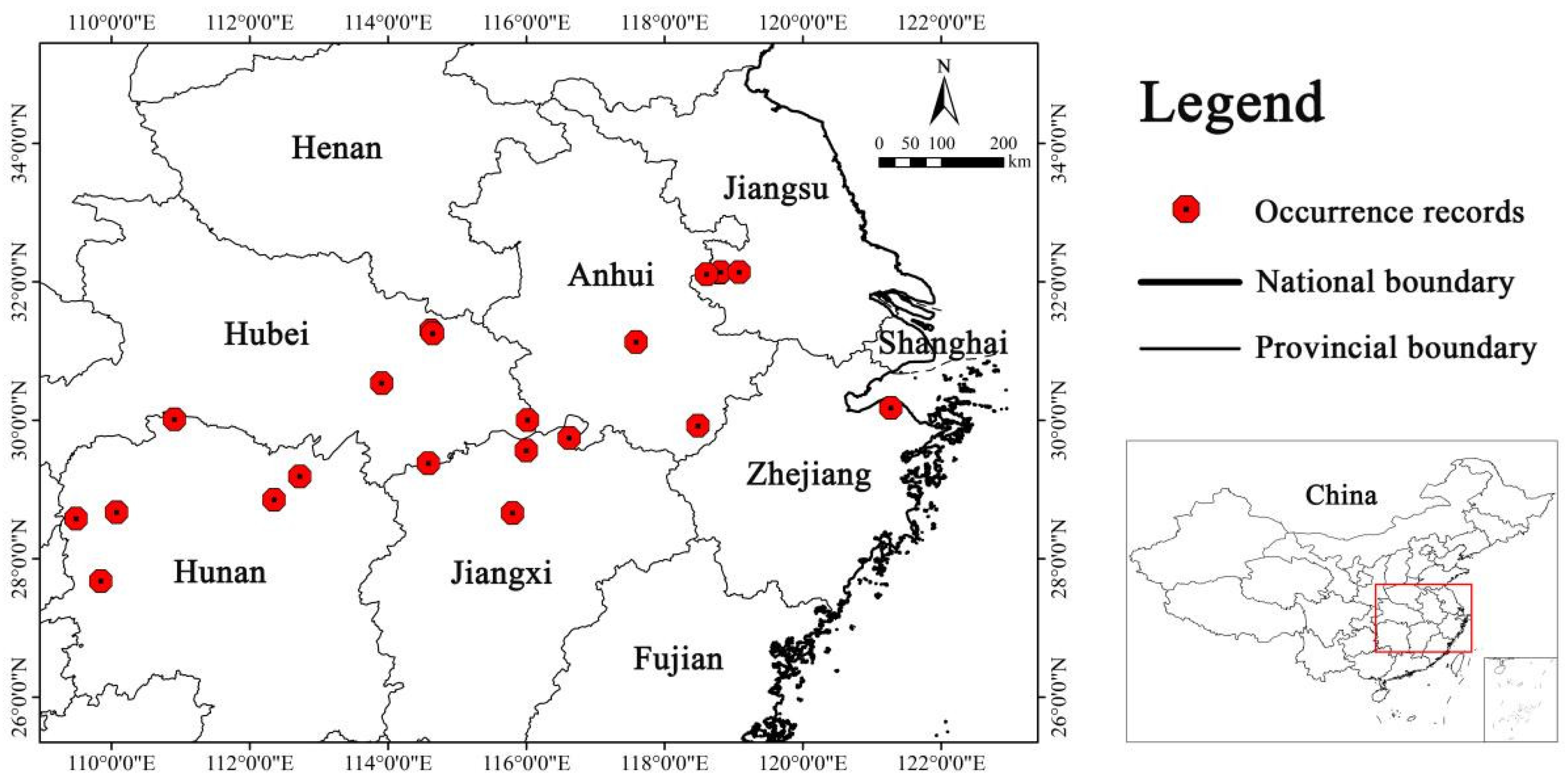

2.1. Species Occurrence Data

2.2. Environmental Variables

2.3. Modeling Process

2.4. Geospatial Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Model Performance

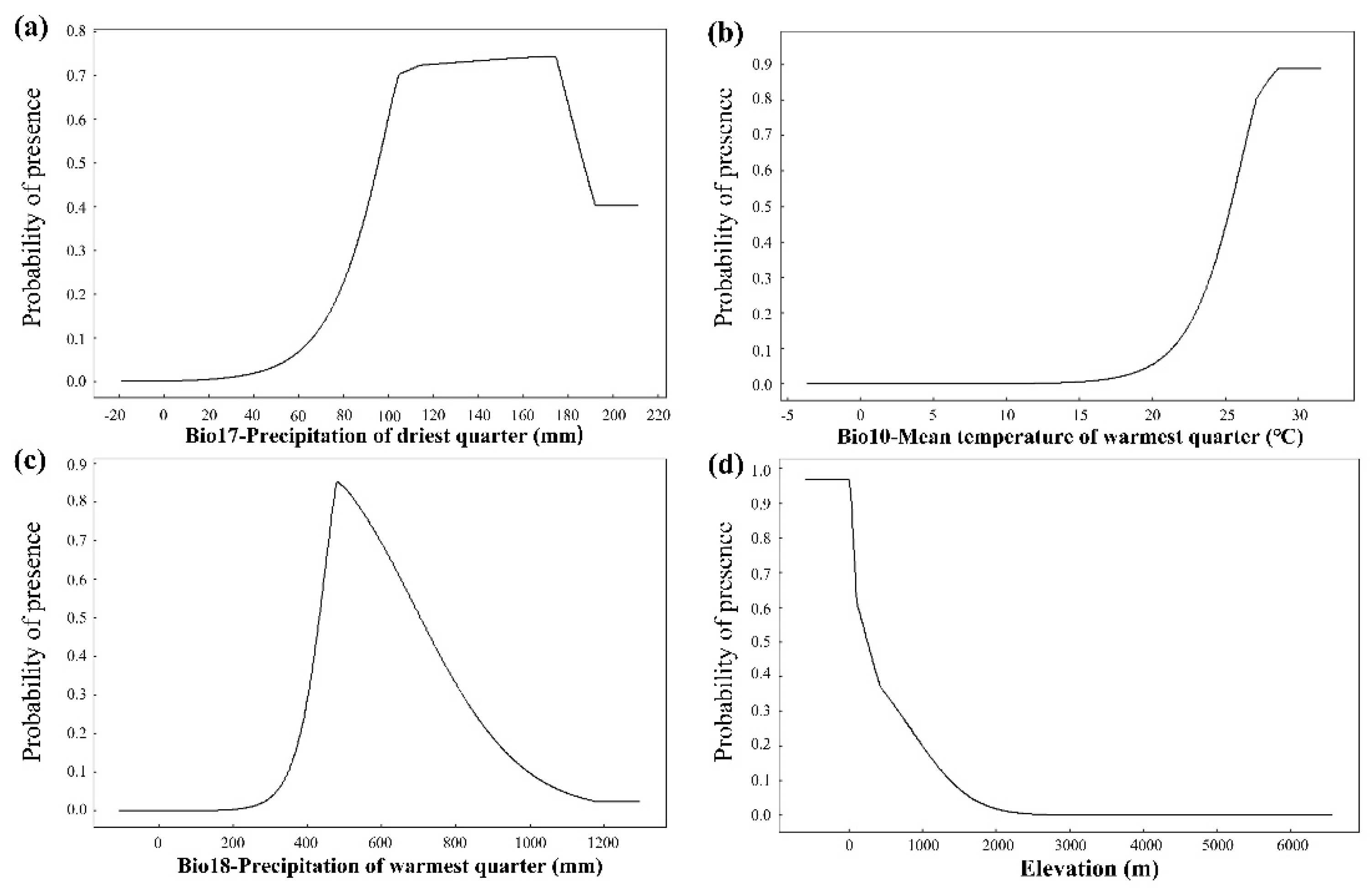

3.2. Main Environmental Factors

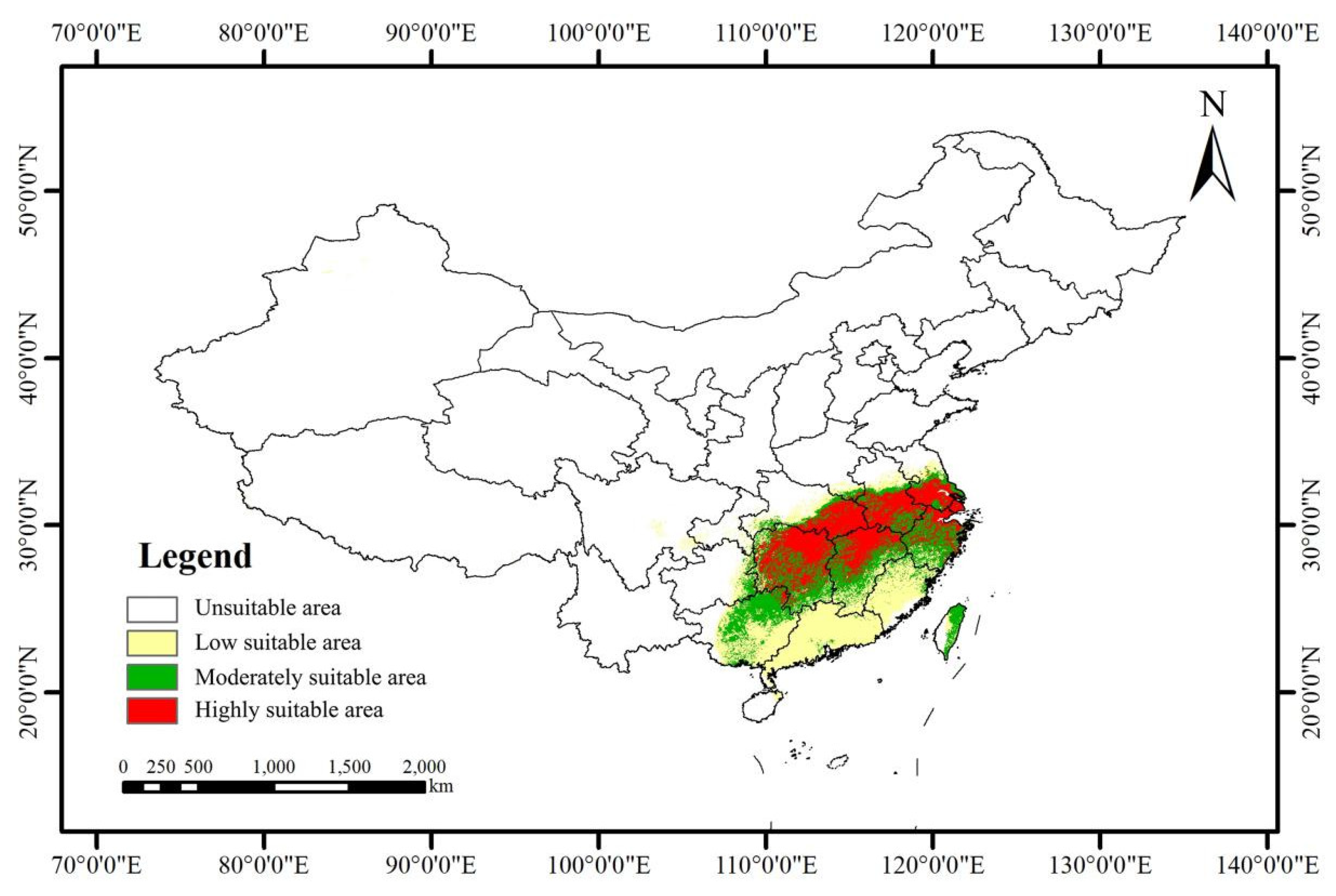

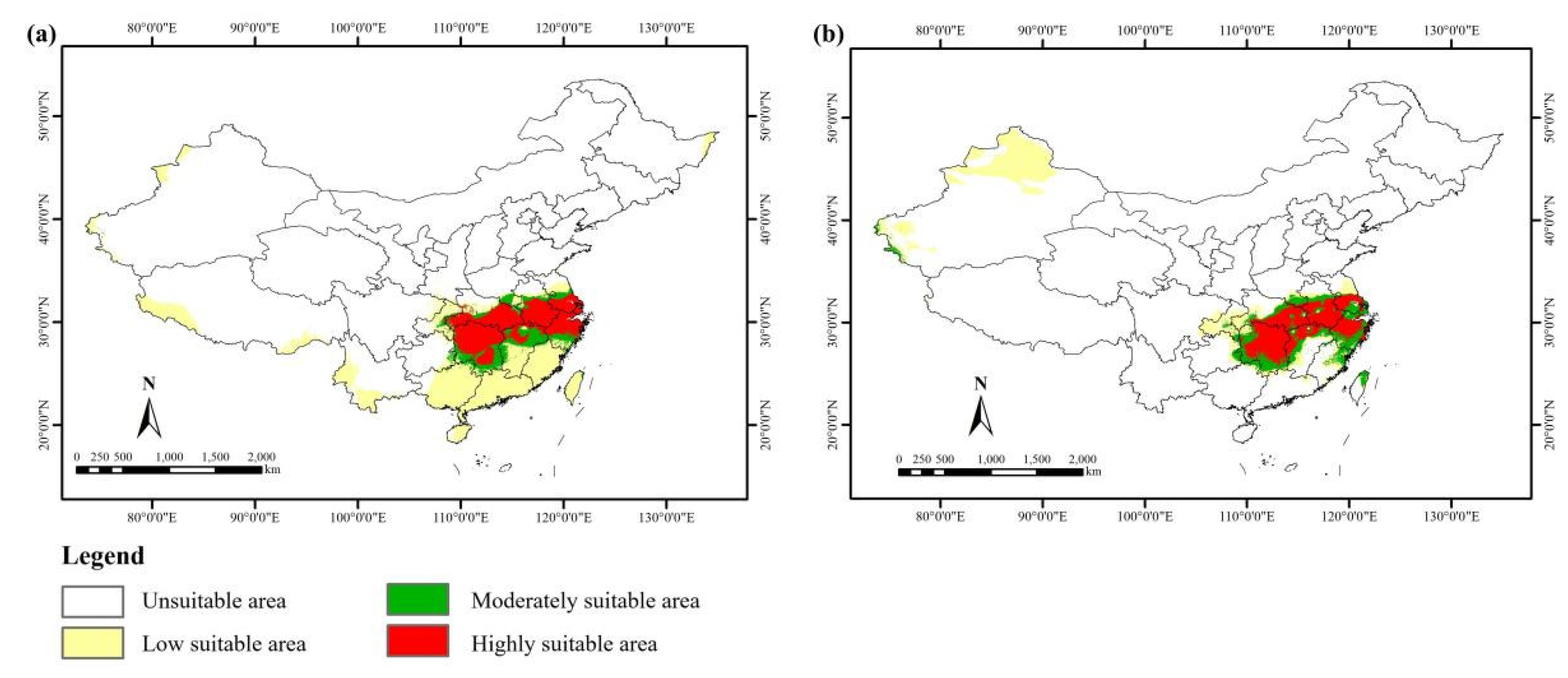

3.3. Current Potential Suitable Distribution

3.4. Potential Suitable Distribution in the Past

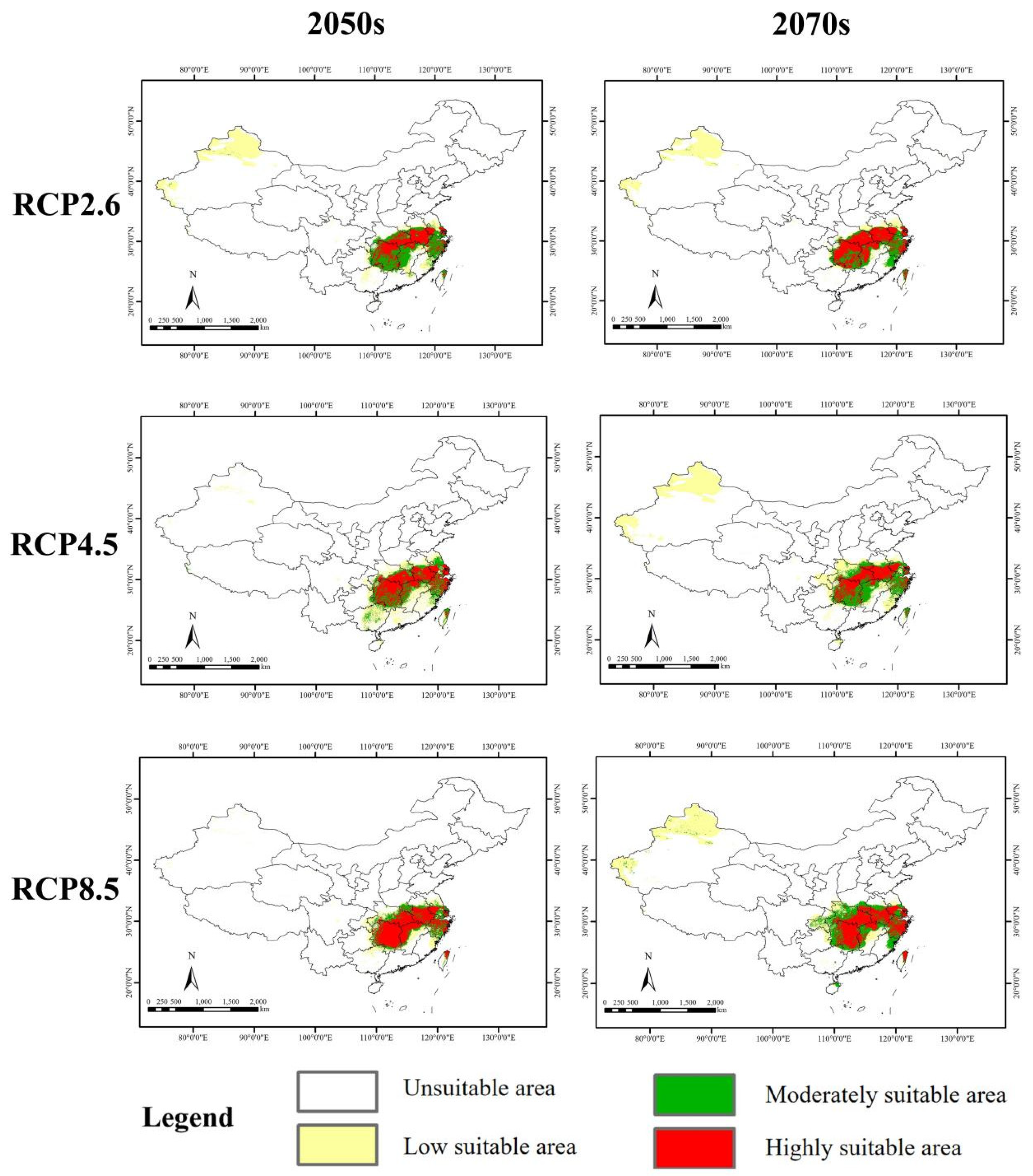

3.5. Potential Suitable Distribution in the Future

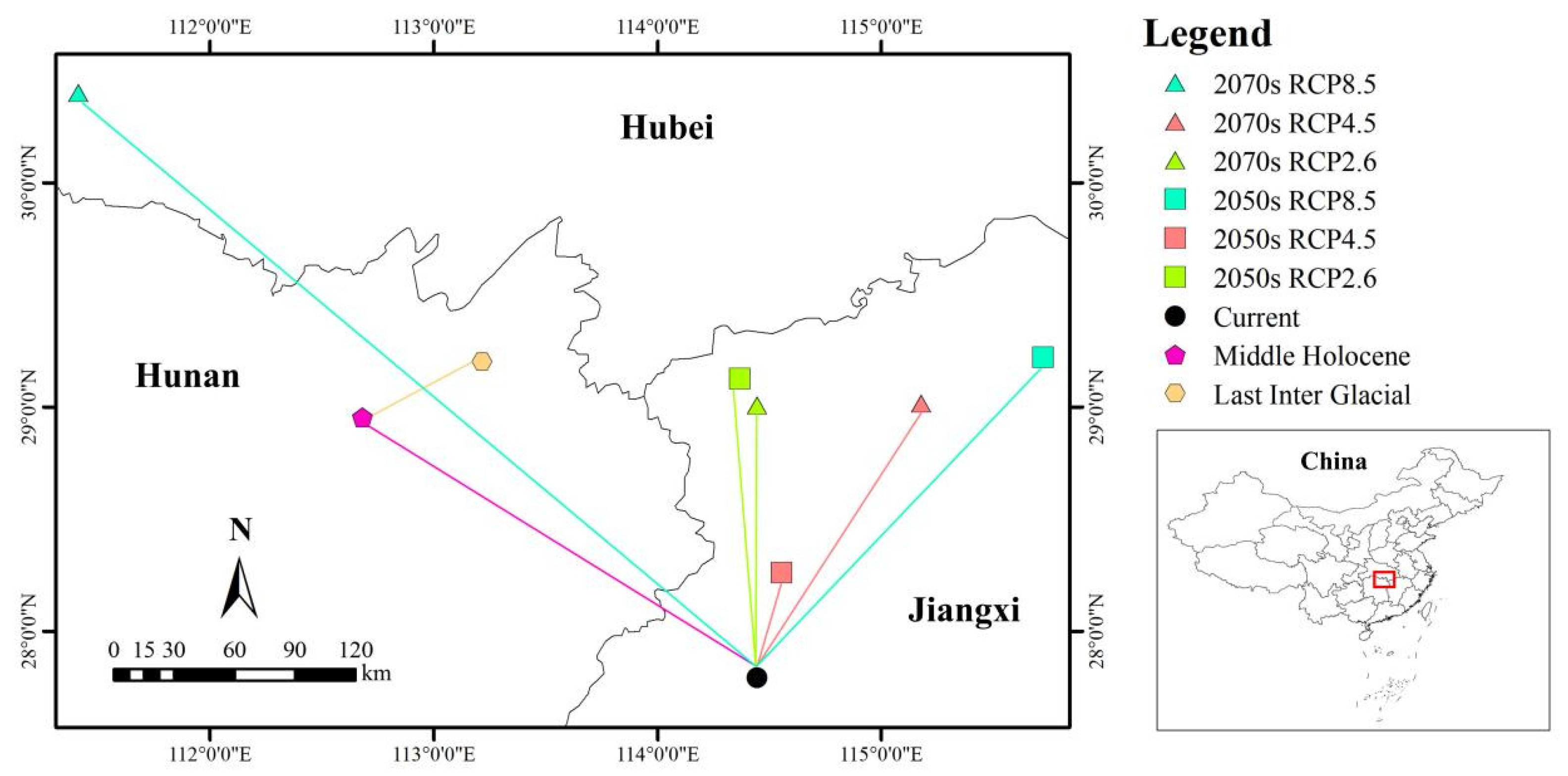

3.6. Centroid Shift under Different Scenarios

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Selection and Evaluation

4.2. Key Influencing Factors of S. xylocarpa

4.3. Current Suitable Area of S. xylocarpa

4.4. Suitable Area Change in the Past and Future

4.5. Conservation Implications for S. xylocarpa

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, J.L.; Bennett, J.R.; French, C.M. SDMtoolbox 2.0: the next generation Python-based GIS toolkit for landscape genetic, biogeographic and species distribution model analyses. PeerJ 2017, 5, e4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.W.; Zhang, G.F. Predicting the potential distribution of rare and endangered Emmenopterys henryi in China under climate change. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Chen, Z.Y. The Geographical distribution of Styracaceae. Bull. Bot. Res. 1995, 16, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Coban, H.O.; Örücü, Ö.K.; Arslan, E.S. MaxEnt modeling for predicting the current and future potential geographical distribution of Quercus libani Olivier. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.L.; Shi, Y.T.; Yang, S.H. Molecular regulation of plant responses to environmental temperatures. Mol. Plant. 2020, 13, 544–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Phillips, S.J.; Hastie, T.J.; Dudík, M.; Chee, Y.E.; Yates, C.J. A statistical explanation of MaxEnt for ecologists. Divers. Distrib. 2011, 17, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Zhang, J.S. Niche evolution and conservation of a Chinese endemic genus Sinojackia (Styracaceae). Biology 2024, 13, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.H.; Qin, Y.Y.; Liang, M.C.; Gao, X. Interpretation of the main conclusions and suggestions of IPCC AR6 Synthesis Report. Env. Prot. 2023, 51, 82–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, R.M.; Huang, Z.Y.; Liu, X.J.; Wang, Z.L.; Xu, H.Q.; Yao, Z.G. The natural distribution and characteristics of the rare and endangered plants in Jiangsu, China. Biodivers. Sci. 2000, (2), 153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.G. Preliminary survey report on Sinojackia microcarpa. Anhui For. Sci. Technol. 2018, 44, 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.H. Sinojackia, a new genus of Styracaceae from southeastern China. J. Arnold Arbor. 1928, 9, 130–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.Y.; An, Q.J.; Huang, S.P.; Tan, G.D.; Quan, H.G.; Chen, Y.N.; Zhou, J.Y.; Liao, H. Biomod2 modeling for predicting the potential ecological distribution of three Fritillaria species under climate change. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.M.; Grimes, J. Styracaceae. In Wu Z Y., Raven P.H. Flora of China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1996; Volume 15, pp. 253–271. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.Y.; Zhu, X.Y. The study on eco-geographical distribution, biology characteristics and propagation techniques of Sinojackia xylocarpa. J. Jiangsu For. Sci. Technol. 1998, 25, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, S.G.; Shen, Y.B. Research progress on Sinojackia xylocarpa Hu. J. Jiangsu For. Sci. Technol. 2007, 34, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.H.; Zhou, Z.H.; Yuan, L.C. National Key Protected Wild Plants of China; Hubei Science and Technology Press: Wuhan, China, 2023; Volume 3, p. 362. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A.M.; Li, Q.; Saqib, Z.; Khan, N.; Habib, T.; Khalid, N.; Majeed, M.; Tariq, A. MaxEnt modelling and impact of climate change on habitat suitability variations of economically important Chilgoza Pine (Pinus gerardiana Wall.) in South Asia. Forests 2022, 13, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Characteristics and cultivation techniques of Sinojackia. Anhui Agric. Sci. Bull. 2014, 20, 120–121. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.R.; Newell, G.; White, M. On the selection of thresholds for predicting species occurrence with presence-only data. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.X. Flora of Jiangsu; Jiangsu Phoenix Science Press: Nanjing, China, 2015; Volume 4, p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Cai, H.W.; Zhang, G.F. Assessment of climate change impacts on the distribution of endangered and endemic Changnienia amoena (Orchidaceae) using ensemble modeling and gap analysis in China. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.H. Research progress of Sinojackia Hu. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 2017, 45, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, L.Q. A new synonym in the genus Sinojackia (Styracaceae). J. Syst. Evol. 2005, 43(6), 561–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.Q. Sinojackia xylocarpa var. leshanensis (Styracaceae), a new variety from Sichuan, China. Bull. Bot. Res. 2005, 25, 260–261. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, L.Q.; Luo, C. Taxonomic circumscription of Sinojackia xylocarpa (Styracaceae). J. Syst. Evol. 2011, 49, 163–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.C.; Shi, Q.Z.; Yang, J.J.; Guo, X.; Fang, Y.P. Study on natural population of Sinojackia huangmeiensis in Hubei Province. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2016, 44, 67–68. [Google Scholar]

- Martı’nez-Minaya, J.; Cameletti, M.; Conesa, D.; Pennino, M.G. Species distribution modeling: a statistical review with focus in spatio-temporal issues. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2018, 32, 3227–3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.N. Seed Plants of China: Checklist, Uses and Conservation Status; Hebei Science and Technology Press: Shijiazhuang, China, 2020; Volume 4, pp. 2277–2278. [Google Scholar]

- Radosavljević, A.; Anderson, R.P. Making better Maxent models of species distributions: complexity, overfitting and evaluation. J. Biogeogr. 2014, 41, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rota, F.; Scherrer, D.; Bergamini, A.; Price, B.; Walthert, L.; Baltensweiler, A. Unravelling the impact of soil data quality on species distribution models of temperate forest woody plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 944, 173719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.D.; Yin, Q.; Sang, Z.Y.; Zhu, Z.L.; Jia, Z.K.; Ma, L.Y. Prediction of potentially suitable areas for the introduction of Magnolia wufengensis under climate change. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 127, 107762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillero, N.; Barbosa, A. Common mistakes in ecological niche models. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2020, 35, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, J.C.; Pearson, R.G.; Horning, N.; Ersts, P.; Reşit Akçakaya, H. Combining static and dynamic variables in species distribution models under climate change. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012, 3, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.T.; Du, Z.X.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, B.; Xiao, Y.A.; Zou, Z.R. MaxEnt modeling for predicting the potential geographical distribution of Hydrocera triflora since the Last Interglacial and under future climate scenarios. Biology 2024, 13, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thuiller, W. BIOMOD–optimizing predictions of species distributions and projecting potential future shifts under global change[J]. Global Change Biol. 2003, 9(10), 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.R.; Zhi, F.Y.; Zhang, G.F. Predicting impacts of climate change on suitable distribution of critically endangered tree species Yulania zenii (W. C. Cheng) D. L. Fu in China. Forests 2024, 15, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.F.; Huang, S.M. Styracaceae. In Flora of China; Wu, Z.Y., Ed.; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1987; Volume 60, p. 144. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.T.; Wang, M.Q.; Li, X.Y.; Yan, Y.D.; Dai, M.J.; Xie, W.Y.; Zhou, X.F.; Zhang, D.L.; Wen, Y.F. Response of distribution patterns of two closely related species in Taxus genus to climate change since Last Inter- Glacial. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e9302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, H.; Ma, W.X.; Zhao, T.T.; Ma, Q.H.; Liang, L.S.; Wang, G.X.; Yang, Z. Prediction of potential distribution of endangered species Corylus chinensis Franch in climate change context. For. Res. 2022, 35, 104–114. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.Q.; Ma, D.D.; Zhang, F.Y.; Xu, L.Y.; Li, X.P.; Chen, Z.H. A new record species of Styracaceae from Zhejiang Province. J. Zhejiang For. Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.J.; Su, X.; Ren, Z.M. Prediction of historical, current and future potential distribution of Rhus chinensis (Anacardiaceae) based on the optimized MaxEnt model in China. Plant Ecol 2024, 225, 1109–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G; Zhang, G.F. Predicting the potential distribution of endangered Parrotia subaequalis in China. Forests 2022, 13, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.F.; Cai, X.Z.; Chen, T. A study on the leaf venation of Changiostyrax C. T. Chen and Sinojackia Hu. Guihaia 1997, 17, 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Wang, S.T.; Wei, Z.X.; Jiang, M.X. Modeling potential distribution of an endangered genus (Sinojackia) endemic to China. Plant Sci. J. 2020, 38, 627–635. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.B.; Liao, J.K.; Tang, M.S. Seed Plants of Taiwan; Forestry Bureau of the Agriculture Commission of the Executive: Taiwan, China, 2008; p. 124. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, X.H.; Ye, Q.G.; Fritsch, P.; Cruz, B.; Huang, H.W. Phylogeny of Sinojackia (Styracaceae) based on DNA sequence and microsatellite data: implications for taxonomy and conservation. Ann. Bot. 2008, 101, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.H.; Ye, Q.G.; Kang, M.; Huang, H.W. Geographic distribution and current status of the endangered genera Sinoiackia and Changiostyrax. Biodiv. Sci. 2005, 13, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.Z.; Zhang, M.Z.; Yang, Q.Y.; Ye, L.Q.; Liu, Y.P.; Zhang, G.F.; Chen, S.P.; Lai, W.F.; Wen, G.W.; Zheng, S.Q.; Ruan, S.N.; Zhang, T.Y.; Liu, B. Prediction of suitable distribution of a critically endangered plant Glyptostrobus pensilis. Forests 2022, 13, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.F.; Xiong, T.S.; Sun, T.; Li, K.D.; Shao, L.Y. Diversity, distribution, and conservation of rare and endangered plant species in Jiangsu Province. Biodiv. Sci. 2022, 30, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Ye, Q.G.; Yao, X.H.; Huang, H.W. Spontaneous interspecific hybridization and patterns of pollen dispersal in ex situ populations of a tree species (Sinojackia xylocarpa) that is extinct in the wild. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.H.; Cui, X.Y.; Sun, J.J.; Li, T.T.; Wang, Q.; Ye, X.Z.; Fan, B.G. Analysis of the distribution pattern of Chinese Ziziphus jujuba under climate change based on optimized biomod2 and MaxEnt models. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 132, 108256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.R.; Lu, X.; Zhang, G.F. Potentially differential impacts on niche overlap between Chinese endangered Zelkova schneideriana and its associated tree species under climate change. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1218149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.M.; Zhu, M.; Liu, W.J. Jiangsu’s Key Protected Species Atlas; Nanjing Normal University Press: Nanjing, China, 2021; pp. 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.; Wei, X.F.; Lu, Y.X.; Zhang, D.W.; Wang, Z.F.; Ge, J.; Li, S.L.; Song, Y.F.; Yi, X.G.; Zhang, M.; Xue, J.Y.; Duan, Y.F. The jacktree genome and population genomics provides insights for the mechanisms of the germination obstacle and the conservation of endangered ornamental plants. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhae166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurell, D.; Franklin, J.; König, C.; Bouchet, P.; Dormann, C.; Elith, J.; Fandos, G.; Feng, X.; Guillera-Arroita, G.; Guisan, A. A standard protocol for reporting species distribution models. Ecography 2020, 43, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Variable | Description | Unit | Percent Contribution (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIG | MH | Current | ||||

| Bioclimate | Bio1 | Annual mean temperature | °C | |||

| Bio2 | Mean diurnal range (mean of monthly (max temp–min temp)) | °C | 5.1 | 0.5 | ||

| Bio3 | Isothermality((Bio2/Bio7) × 100) | % | 0.4 | 2.8 | 2.2 | |

| Bio4 | Temperature seasonality(standard deviation × 100) | - | 19.1 | 1.5 | ||

| Bio5 | Max temperature of warmest month | °C | 1.2 | |||

| Bio6 | Min temperature of coldest month | °C | 0.6 | |||

| Bio7 | Temperature annual range (Bio5–Bio6) | °C | 2.1 | |||

| Bio8 | Mean temperature of wettest quarter | °C | 3.1 | 7.3 | ||

| Bio9 | Mean temperature of driest quarter | °C | 1.9 | 2.7 | ||

| Bio10 | Mean temperature of warmest quarter | °C | 21.7 | 9.6 | ||

| Bio11 | Mean temperature of coldest quarter | °C | 16.6 | 15.5 | ||

| Bio12 | Annual precipitation | mm | 4.4 | |||

| Bio13 | Precipitation of wettest month | mm | 3.7 | 8.7 | ||

| Bio14 | Precipitation of driest month | mm | ||||

| Bio15 | Precipitation seasonality (coefficient of variation) | - | 6.5 | 27.5 | 0.9 | |

| Bio16 | Precipitation of wettest quarter | mm | ||||

| Bio17 | Precipitation of driest quarter | mm | 19.6 | 23.0 | 61.0 | |

| Bio18 | Precipitation of warmest quarter | mm | 4.2 | 9.5 | 8.9 | |

| Bio19 | Precipitation of coldest quarter | mm | ||||

| Topography | Elevation | - | m | 5.4 | ||

| Slope | - | ° | 0.2 | |||

| Soil | T-BS | Topsoil Base Saturation | % | 0.5 | ||

| T-CaCO3 | Topsoil Calcium Carbonate | % | 0.1 | |||

| T-CEC-CLAY | Topsoil CEC (clay) | - | 0.7 | |||

| T-CEC-SOIL | Topsoil CEC (soil) | - | 0.1 | |||

| T-CLAY | Topsoil Clay Fraction | % | ||||

| T-ECE | Topsoil Salinity (Elco) | S/m | ||||

| T-ESP | Topsoil Sodicity (ESP) | - | 0.1 | |||

| T-GRAVEL | Topsoil Gravel Content | % | 0.6 | |||

| T-OC | Topsoil Organic Carbon | % | 0.1 | |||

| T-PH-H2O | Topsoil pH (H2O) | - | ||||

| T-REF-BULK | Topsoil Reference Bulk Density | kg/m3 | 0.1 | |||

| T-SAND | Topsoil Sand Fraction | % | ||||

| T-SILT | Topsoil Silt Fraction | % | 0.1 | |||

| T-TEB | Topsoil TEB | - | ||||

| T-TEXTURE | Topsoil TEXTURE | - | ||||

| T-USDA-TEX | Topsoil USDA Texture Classification | - | 0.2 | |||

| Model name | Model code | AUC | TSS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial neural networks model | ANN | 0.8632 ± 0.1719 | 0.7324 ± 0.1882 |

| Classification tree analysis model | CTA | 0.8930 ± 0.0722 | 0.7864 ± 0.1436 |

| Flexible discriminant analysis model | FDA | 0.9274 ± 0.0429 | 0.7376 ± 0.0938 |

| Generalized additive model | GAM | 0.7692 ± 0.1709 | 0.6320 ± 0.2128 |

| Generalized boosting model | GBM | 0.9376 ± 0.0390 | 0.7089 ± 0.0548 |

| Generalized linear model | GLM | 0.8468 ± 0.0817 | 0.6936 ± 0.1635 |

| Maximum entropy model | MaxEnt | 0.9690 ± 0.0209 | 0.8918 ± 0.0398 |

| Multivariate adaptive regression splines model | MARS | 0.8342 ± 0.1135 | 0.6704 ± 0.2276 |

| Random forest model | RF | 0.9499 ± 0.0297 | 0.7130 ± 0.0867 |

| Surface range envelope model | SRE | 0.5352 ± 0.0498 | 0.1920 ± 0.0056 |

| Ensemble model | 0.9960 ±0.0641 | 0.9500 ±0.0610 |

| Scenarios | Low Suitable Area |

Moderately Suitable Area |

Highly Suitable Area |

Suitable Area (Moderately and Highly) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (×104 km2) |

Trend (%) | Area (×104 km2) |

Trend (%) | Area (×104 km2) |

Trend (%) | Area (×104 km2) |

Trend (%) | ||

| Last Interglacial | 97.56 | ↑97.81 | 20.38 | ↓42.70 | 43.46 | ↑27.26 | 63.84 | ↓8.43 | |

| Middle Holocene | 59.24 | ↑20.11 | 26.30 | ↓26.06 | 38.20 | ↑11.86 | 64.50 | ↓7.49 | |

| Current | 49.32 | - | 35.57 | - | 34.15 | - | 69.72 | - | |

| 2050s | RCP2.6 | 57.36 | ↑16.30 | 30.98 | ↓12.90 | 28.83 | ↓15.58 | 59.81 | ↓14.21 |

| RCP4.5 | 38.31 | ↓22.32 | 24.66 | ↓30.67 | 37.25 | ↑9.08 | 61.91 | ↓11.20 | |

| RCP8.5 | 22.59 | ↓54.20 | 16.24 | ↓54.34 | 42.10 | ↑23.28 | 58.34 | ↓16.32 | |

| 2070s | RCP2.6 | 47.90 | ↓2.88 | 21.48 | ↓39.61 | 38.86 | ↑13.79 | 60.34 | ↓13.45 |

| RCP4.5 | 75.56 | ↑53.20 | 30.06 | ↓15.49 | 29.16 | ↓14.61 | 59.22 | ↓15.06 | |

| RCP8.5 | 64.34 | ↑30.45 | 31.44 | ↓11.61 | 41.33 | ↑21.02 | 72.77 | ↑4.37 | |

| The mean value of six future climate scenarios | 51.01 | ↑3.43 | 25.81 | ↓27.44 | 36.26 | ↑6.18 | 62.07 | ↓10.97 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).