1. Introduction

In the current global scenario, producing approximately 150 million tons of plastic annually poses a severe environmental threat. Most plastics are derived from oil, contributing significantly to widespread contamination. This environmental challenge arises from the excessive plastic production and the overexploitation of fossil resources. Efforts to mitigate this pollution have led to the exploration of strategies such as recycling and incineration. However, the latter often perpetuates the pollution cycle [

1].

There has been a noteworthy shift from petroleum-based materials to natural ones in response to the environmental crisis. Substances like starch, cellulose, and proteins have gained attention due to their high edible grade, availability, and biocompatibility [

2,

3,

4].

Moreover, these natural materials contribute positively to pollution reduction owing to their inherent biodegradability capacity [

5]. The permeability of these materials to oxygen makes them particularly useful in packaging edible products, maintaining characteristics such as odor, taste, and color [

6].

Numerous studies have explored using starch in creating membranes due to its widespread availability, cost-effectiveness, and gelatinization capability when exposed to high temperatures and water [

7]. Starch comprises of glucose units known as amylose and amylopectin, in varying amounts depending on the source. These molecules are responsible for the gelatinization process of starch. However, films derived from starch tend to be relatively rigid and exhibit a strong hydrophilic character compared to synthetic counterparts.

Plasticizers, mainly polyols, are employed to overcome this rigidity, with glycerol being the most commonly used due to its hydrophilic nature. With appropriate proportions, glycerol reduces intermolecular forces and enhances the mobility of polymer chains, thereby improving mechanical properties [

7,

8,

9]. Furthermore, edible films based on fruit purees have been explored, providing an alternative for producing films used in food product packaging.

Banana peel, stands out as a resource with high phytochemical components such as pigments, polyphenols with antioxidant capacity, anthocyanins, tocopherols, phytosterols, and ascorbic acid [

10]. These properties make banana peel a potential source for obtaining films for various applications, including packaging material for food or fruit [

11].

This project aims to research endeavors to obtain and characterize a biopolymeric film from banana peel waste, thus contributing to sustainable practices in packaging materials and waste utilization.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Film Formation

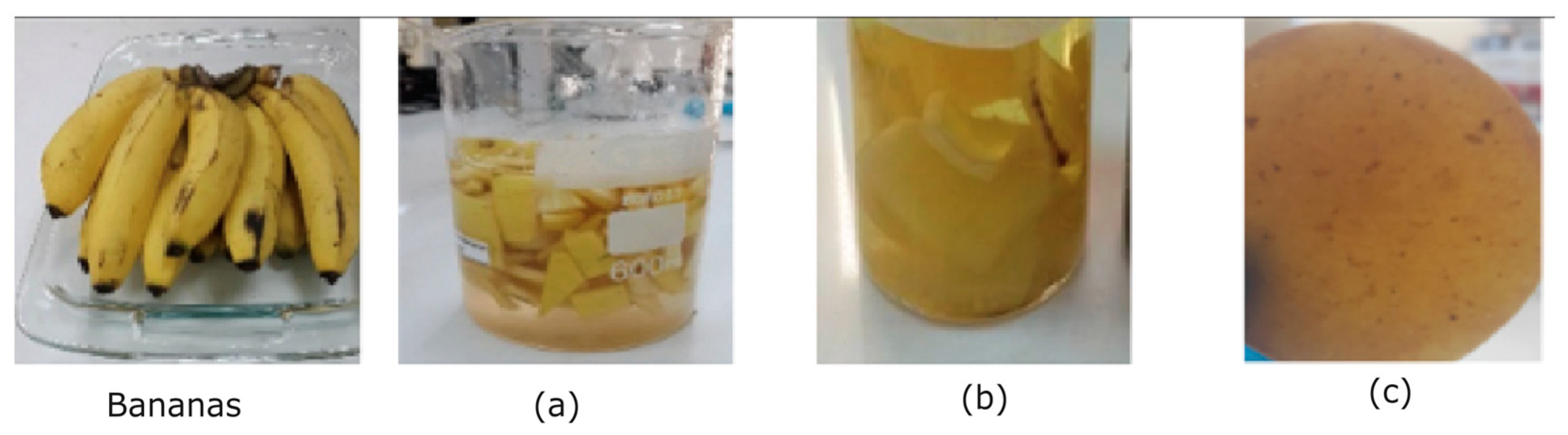

To enhance extraction, 50 grams of finely chopped mature banana peel fragments were immersed in a 50 ml sodium metabisulfite solution (see

Figure 1(a)). The solid component underwent a 10-minute boiling procedure in distilled water at 110°C, with intermittent stirring, and the liquid phase was subsequently discarded. The resulting mixture was meticulously crushed to achieve a homogeneous paste (see

Figure 1(b)).

The obtained paste was then subjected to a second stage, where it underwent a cooking process at 110°C for 25 minutes under continuous magnetic stirring. According to the methodology proposed by [

12], this stage involved the addition of 2 ml each of 0.5 N HCl, 0.5 N NaOH, and a plasticizer (Glycerin). These additions aimed to optimize the biopolymeric material's characteristics [

6].

Finally, the well-prepared mixture was carefully transferred into Petri dishes and subjected to a drying process in an oven set at 45°C for 48 hours. This meticulous procedure ensures the production of a high-quality biopolymeric membrane derived from the mature banana peel, ready for subsequent characterization studies (see

Figure 1(c)).

2.2. Film Solubility in Water and Moisture Uptake

The biopolymeric films' water absorption capacity and moisture uptake were evaluated following the ASTM [

13] standard method. This rigorous approach ensures reliable and comparable results in assessing film solubility in water.

To initiate the experiment, three biopolymer sheets were meticulously conditioned in an oven set at 50°C for 24 hours. Following this conditioning period, the sheets were promptly transferred to a desiccator for 15 minutes to achieve equilibrium and were then accurately weighed. Subsequently, these conditioned samples were immersed in beakers containing 100 ml of distilled water for two hours, ensuring complete submersion.

After immersion, the biopolymer samples were carefully extracted, excess water was removed using absorbent paper, and the samples were reweighed. To ascertain the extent of water absorption, the water in the beakers was replaced, and a subsequent weighing was conducted after an additional 24-hour period.

In the determination of soluble matter, the membranes underwent a reconditioning phase. This allowed them to dry for 24 hours at a controlled temperature of 45°C. Finally, the samples were cooled within a desiccator and subjected to a final weighing.

This systematic methodology provides a comprehensive understanding of the film's behavior in water, allowing for precise quantification of water absorption and soluble matter content. The meticulous conditioning, standardized immersion period, and subsequent reconditioning ensure the accuracy and reliability of the obtained results.

2.3. UV-Visible Spectrophotometry

The assessment of film transparency was conducted through UV-visible spectrophotometry, a crucial step in understanding the optical characteristics of the biopolymeric films, as outlined by [

2]. This technique provides valuable insights into how the films interact with light across a broad spectrum.

The UV-visible spectra were acquired using a Thorlabs CCS200 (Newton, NJ) spectrophotometer, covering the wavelength range from 200 to 1000 nm. This wide range allows for a detailed examination of the film's transparency and its behavior across various wavelengths of light. The obtained spectra offer information on factors such as light absorbance and transmittance, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the optical properties of the biopolymeric film.

2.4. Mechanical Properties

The evaluation of the mechanical properties of the biopolymeric films is critical in order to gauge their structural integrity and suitability for applications. The measurement of mechanical resistance was conducted following the protocol suggested by [

8] and adhering to the ASTM [

14] standard method. This meticulous approach ensures the reliability and precision of the mechanical characterization.

For this assessment, samples with dimensions of 80 mm in height and 25 mm in width were carefully prepared. These dimensions agree with the specified standards to maintain consistency and reliability in the results. The mechanical tests were performed using a Brookfield CT3 Texturometer, a state-of-the-art instrument designed to measure materials' textural properties precisely.

A firing load of 7 g was applied to the samples, and the testing procedure was executed at a constant speed of 0.5 mm/s. This controlled testing environment allowed for accurate measurement of key mechanical parameters, including tensile strength and elasticity. By adopting these standardized methods, we ensure that the mechanical properties are evaluated under consistent and reproducible conditions, facilitating meaningful comparisons and interpretations of the results.

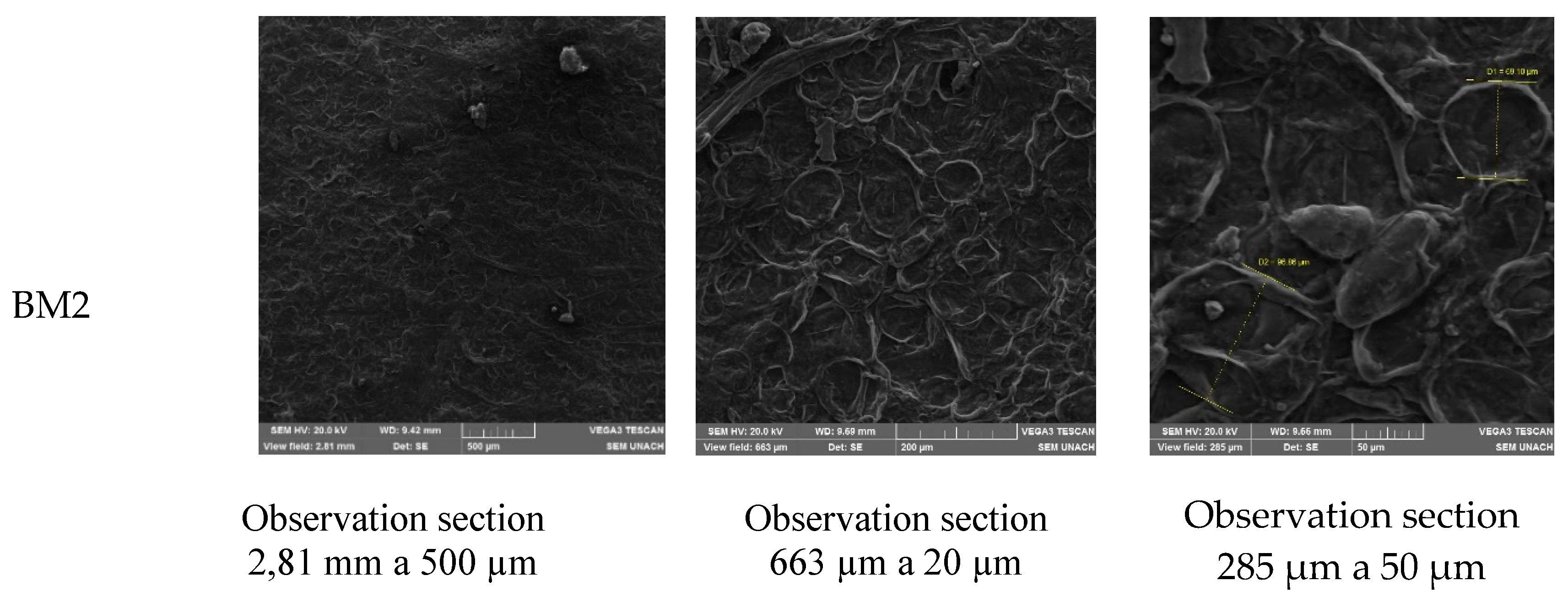

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

To delve into the intricate details of the biopolymeric film's surface morphology, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed, utilizing the advanced Bruker VEGA 3 TESCAN instrument with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS). The SEM analysis was conducted at the Universidad Nacional del Chimborazo (UNACH), employing an acceleration voltage of 20 kV.

The preparatory steps involved cutting square segments of the film samples, measuring approximately 0.25 cm, which were then meticulously mounted on a sample holder using double-sided carbon tape. A thin layer of gold coating was applied using an SPI module Sputter Coater from the United States for 40 seconds to enhance the conductivity and visualization.

2.6. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

The evaluation of the thermal stability of the biopolymeric film is crucial to understanding its performance under varying temperature conditions. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted using the advanced DSC-TGA SDT Q600 V8.3 Build 101 equipment, employing the ramp method. This comprehensive analysis involved heating the sample from room temperature to an impressive 1,000°C with a heating rate of 20°C/min.

The use of an inert atmosphere, specifically nitrogen (N2), is paramount in preventing oxidation or combustion during the analysis, considering the organic nature of the material. To ensure the optimal conditions for the experiment, a constant nitrogen flow rate of 100 ml/min was maintained throughout the analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Water Absorption and Solubility

The biopolymeric film obtained from the banana peel (MB2) exhibited notable water absorption characteristics, registering a percentage of 115.23% with a corresponding soluble matter content of 61.75%. This level of water absorption surpassed that of soy films, which typically fall within the range of 63-75% water absorption [

15]. Understanding and comparing water absorption properties was pivotal in determining the film's suitability for various applications.

Like the biopolymeric film (BM2), Achira starch films showed solubility influenced by temperature and relative humidity during the drying process. The interaction between plasticizer, biopolymer chains, and water is enhanced under specific drying conditions, rendering the films hydrophilic [

16]. The soluble nature of BM2 dried at 45°C with 50% relative humidity can be attributed to such favorable conditions.

According to [

17], plasticizers contribute to increased solubility by reducing interactions between biopolymeric molecules, making them more hydrophilic. The low molecular weight of the plasticizer facilitates its insertion between biopolymer chains, further enhancing solubility [

17]. The solubility characteristics observed in BM2 underscore the importance of plasticizer selection and processing conditions in tailoring the film's properties.

Additionally, the affinity of biopolymer membranes, particularly those based on starches, for water can accelerate the degradation of certain hydrophobic biopolymers [

18]. Consequently, in some cases, blending starches with non-degradable polymers is recommended to balance the solubility and degradation characteristics. As exhibited by BM2, high solubility could make it well-suited for applications such as packaging wraps, where controlled solubility can offer specific advantages. The nuanced understanding of water absorption and solubility presented here is crucial for determining the potential applications and optimizing the performance of the biopolymeric film derived from banana peel.

3.2. UV-Visible Spectrophotometry

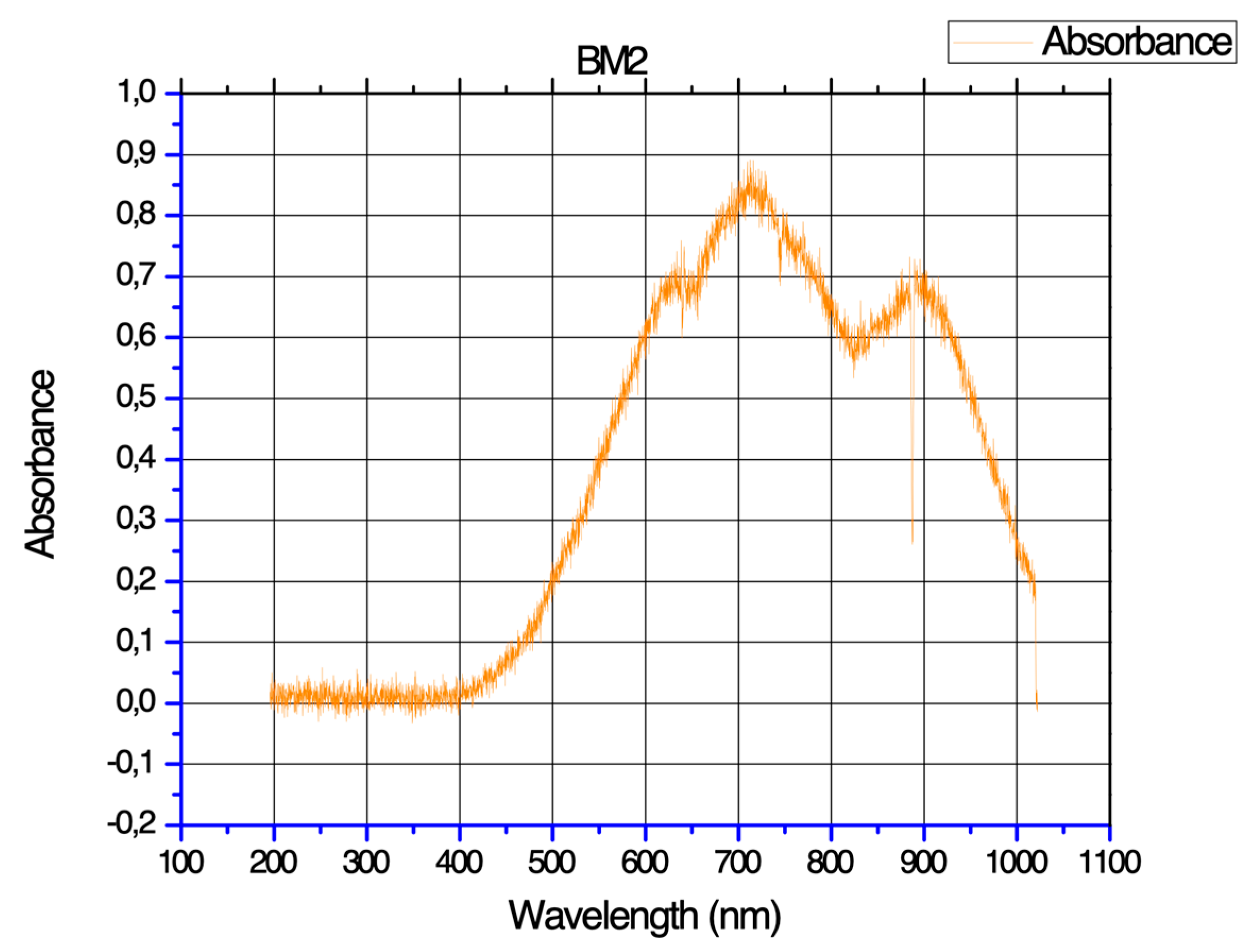

The absorption characteristics of the biopolymeric film is shown in

Figure 2. The white light used for the analysis covered a wavelength range from 200 to 1000 nm.

The observed spectrum reveals insightful details about the film's optical properties. Notably, the maximum wavelength (λmáx) absorbed by the film molecules is recorded at 720 nm, with an absorbance value of 0.9. This absorption peak falls within the infrared spectral region. The first peak, with an absorbance of 0.75, is situated within the visible spectrum in the range of 625 nm. The second peak, exhibiting an absorbance of 0.72, occurs near the infrared region, specifically around 890 nm [

19]. This dual-peak pattern suggests the film's responsiveness to both visible and infrared light.

Understanding the absorbance peaks is vital for potential applications, as it provides insights into the film's transparency and how it interacts with different regions of the electromagnetic spectrum.

3.3. Mechanical Properties

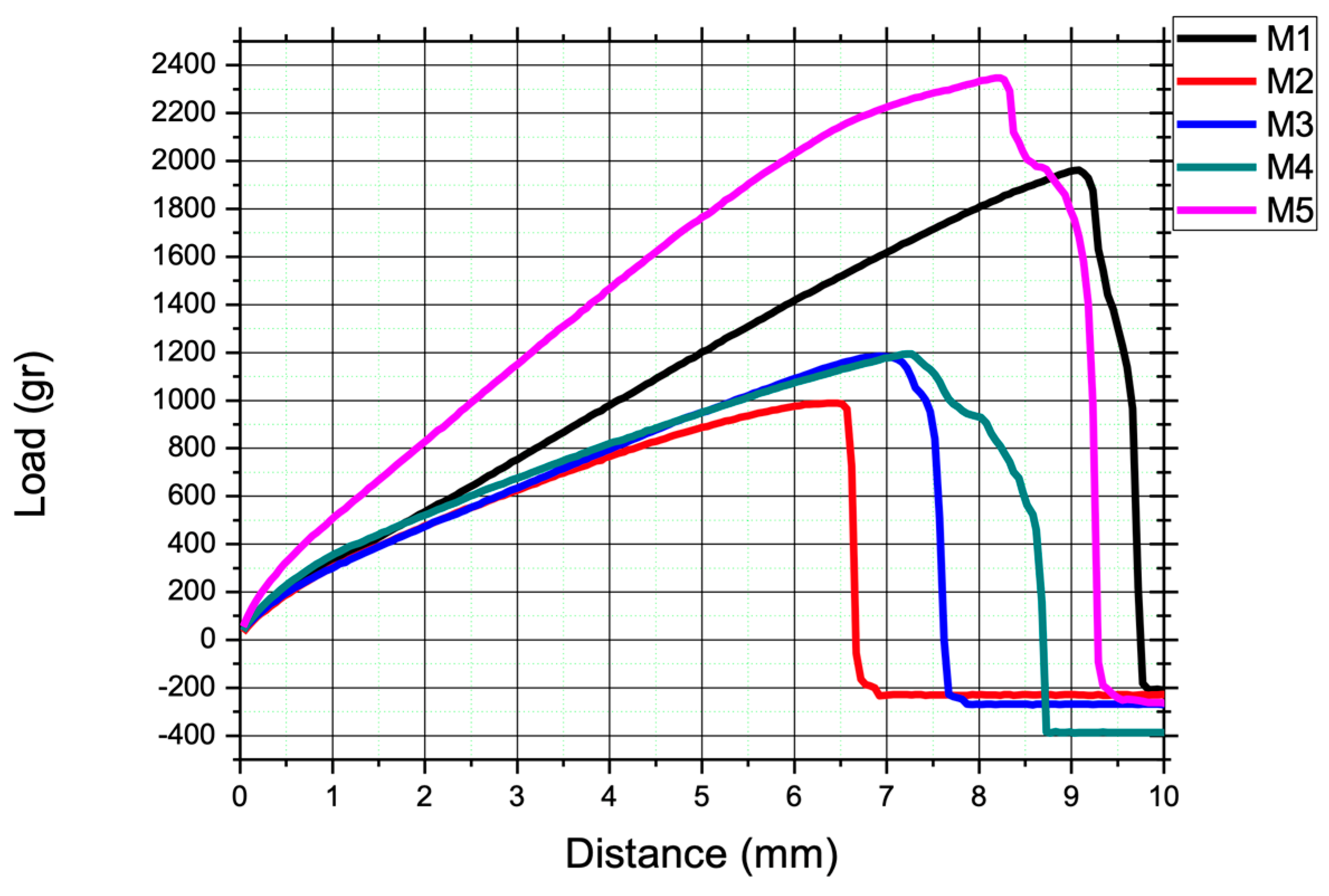

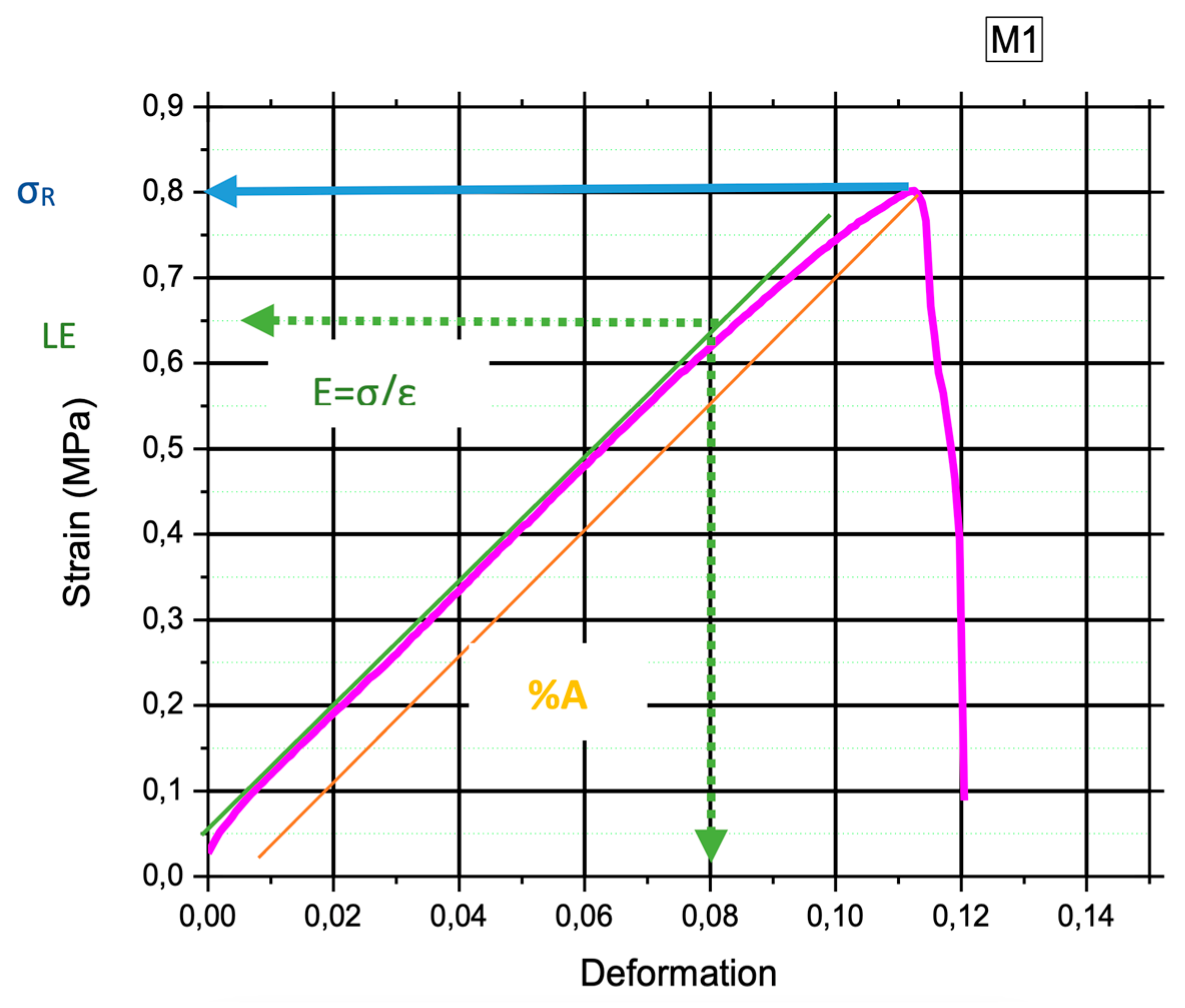

The examination of the mechanical properties of biopolymer membranes derived from banana peel residues (BM2), as depicted in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, offers valuable insights into the material's structural behavior and potential applications.

In

Figure 3, we observe the load-bearing capacity of the biopolymeric membrane as it responds to an applied load quantified in grams. This fundamental aspect of mechanical behavior is crucial for understanding the material's strength and its ability to withstand external forces. The data extracted from this graph allows us to evaluate the resilience and durability of the biopolymeric film, which is essential in applications where load-bearing capabilities play a significant role, such as packaging or structural components.

Table 1 summarizes the mechanical test results for the five specimens and indicates that the test sample labeled M5, which exhibited a maximum load capacity of 2.3 kg, was distinct from the others due to its thickness of 0.36 mm. From these values, it was determined that the maximal tensile stress sustained by the material before failure was 0.028 MPa.

Figure 4 provides a more detailed analysis by illustrating the relationship between tension and deformation of (MB2). A quasi-linear trend is observed in this graph, and the slope of this linear portion represents Young's modulus or modulus of elasticity (E). This modulus quantifies the material's stiffness and its ability to deform under applied stress. The observed quasi-linear behavior indicates the elastic nature of the material, suggesting that it returns to its original form after the removal of the applied force. In this context, a calibration was performed on the linear section of the model, resulting in the determination of a Young's modulus of 7.48 MPa.

Furthermore, the graph reveals a notable feature—the material's maximum tension, often denoted as the elastic limit (LE) or yield strength (σy), is reached at 0.65 MPa. Traditionally, beyond this point, one would expect a curved region indicating plastic deformation. However, in the case of BM2, this transition is almost imperceptible due to the material's tendency to break abruptly once the elastic limit is reached.

It's important to point out that the mechanical tests that were carried out provided valuable data on the strength, flexibility, and overall behavior of the biopolymeric films. It turns out that the quality of these films depends greatly on their physical appearance, that is, their morphology. For example, when these films exhibit lumps or remnants of material that do not dissolve well, their resistance tends to decrease [

5]. For these films to be strong and efficient, we need to focus on improving their structure from the beginning of their production, so they are more uniform and flawless. Thus, they will not only be more resistant but will also be able to better adapt to different uses.

3.4. Morphology

The examination of the biopolymeric membrane's surface, as depicted in

Figure 5, revealed intriguing irregularities that warranted a more in-depth analysis. Notably, these irregularities corresponded to the presence of cellulose fibers that had not undergone complete solubilization during the hydrolysis process. This observation held significant implications for both mechanical and moisture absorption properties, influencing the overall performance of the biopolymeric film.

The irregularities on the surface of the membrane were attributed to the residual presence of cellulose fibers. Despite efforts during the hydrolysis process, some cellulose fibers remained undissolved. The incomplete solubilization of cellulose introduced variations in the film's texture and composition, creating agglomerations that were visibly apparent in the micrographs.

The presence of these cellulose fibers directly impacted the biopolymeric membrane's mechanical resistance. As elucidated by [

20], irregularities, particularly in the form of agglomerations, contributed to a reduction in mechanical strength. The fibers acted as points of weakness, disrupting the homogeneity of the film structure and leading to localized stress concentrations. Consequently, this compromised mechanical strength may have affected the film's performance in applications where robustness is critical.}

3.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

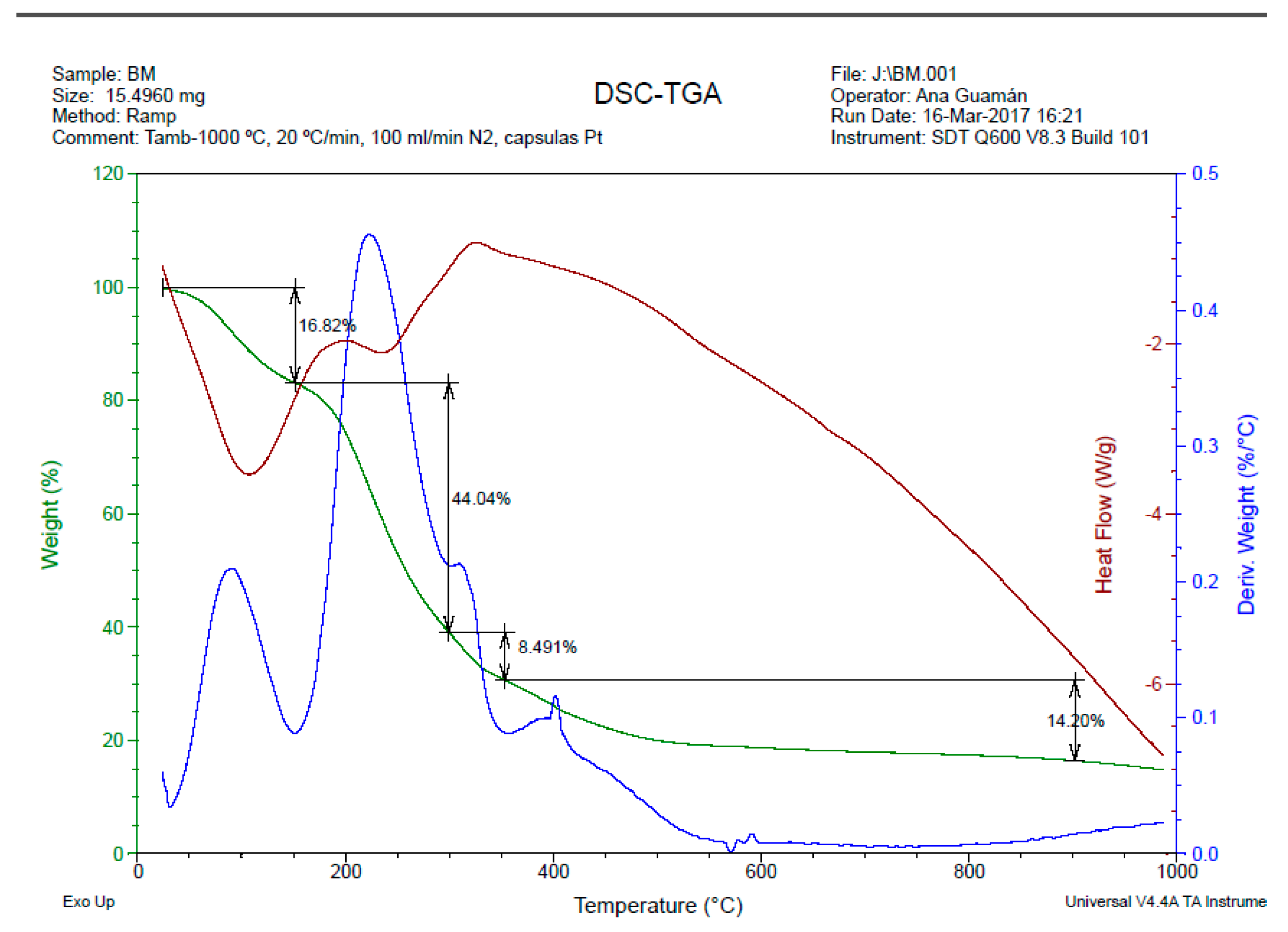

The thermogravimetric curve (TG) presented in

Figure 6, along with its derivative (DTG), offers a comprehensive insight into the thermal degradation behavior of the biopolymeric film derived from banana peel waste (BM2). The detailed analysis of these curves reveals distinct stages of mass loss, shedding light on the thermal stability and decomposition processes of the film.

The initial stage of the TG curve, observed at around 160 °C, indicates a mass loss of 16.82%. This initial loss is attributed to the evaporation of water present in the film. This phenomenon is commonplace and represents the removal of moisture content within the film structure.

The second stage, spanning the temperature range of 160 to 300 °C, shows a substantial mass loss of 44.04%. This stage corresponds to the decomposition of low molecular weight molecules, such as glycerin and residual water. The elimination of these components contributes to the overall reduction in mass during this temperature interval.

The most significant weight loss, observed at 300 °C, corresponds to the mass of the starch-glycerin mixture. This stage involves the elimination of hydrogen bonds and the decomposition of polymer chains within the starch component of the film. Studies by [

21,

22] support this interpretation, highlighting the thermal degradation of starch-based materials in a similar temperature range.

Moving to the third stage, a mass loss of 8.49% occurs within the 300 to 350 °C temperature range. This stage signifies the thermal degradation of organic compounds present in the film. The breakdown of more complex molecular structures contributes to the ongoing decomposition process.

In the final stage, between 350 to 900 °C, a mass loss of 14.20% is observed. This stage marks the carbonization of hydrocarbon compounds present in the film, forming carbonaceous residues. The remaining material undergoes further transformation as the temperature rises.

Notably, the biopolymeric film's degradation temperature is substantially higher than that of high-density polyethylene (HDPE), a common synthetic polymer. While HDPE typically undergoes total degradation within the range of 120 to 130 °C, the biopolymeric film exhibits significantly higher thermal stability, with the most significant mass loss occurring at temperatures ranging from 160 to 300 °C.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Low Tensile Strength and High Solubility:

The observed low tensile strength in the biopolymeric membrane is a characteristic that merits consideration. This attribute can be strategically leveraged in applications where controlled flexibility is advantageous, such as in certain types of packaging like [

23] which uses essential oils, such as melaleuca and cinnamon, to reduce the elastic modulus of the film, which increases its flexibility, making them more suitable for food packaging. The high solubility in water further emphasizes the film's biodegradable nature, aligning with the global trend towards sustainable and environmentally friendly materials. To [

24] also consider the biodegradable nature, a characteristic that is consistent with the global trend towards sustainable and environmentally friendly materials.

4.2. High Water Absorption and Biodegradability:

The significant degree of water absorption underscores the film's high biodegradability. This property positions the biopolymeric membrane as a viable alternative in applications where materials with minimal environmental impact are sought. The film's ability to absorb water contributes to its overall eco-friendly profile, making it a promising solution for specific applications in disposable and environmentally sensitive contexts. The research conducted by [

25] they highlight the ecological profile and environmental benefits that this type of membrane provides in the environmental context.

4.3. Morphological Irregularities and Low Resistance:

To enhance the mechanical strength and functionality of biopolymeric films, it is fundamental to understand in detail their surface structure and composition. The use of techniques such as Scanning Electron Microscopy and Energy Dispersive X-ray Analysis allows for an in-depth examination of the film's surface topography, identifying irregularities and insoluble materials like cellulose fibers, which can weaken the structure and affect the film's mechanical strength and its ability to resist moisture absorption. This aspect is crucial in applications that require maintaining low moisture levels, such as the packaging of sensitive products. To overcome these challenges, optimizing the production process and adjusting the hydrolysis of cellulose improves cellulose solubility, resulting in a more uniform and defect-free film surface. These improvements not only increase the film's strength and durability but also optimize its moisture barrier properties, expanding its applicability in various situations, from packaging to structural applications where robustness and moisture resistance are key. In the study conducted by [

26] also recommends extending the shelf life and maintaining the quality of packaged products, especially moisture-sensitive foods, by optimizing biopolymeric films for use in packaging.

4.4. The Thermogravimetric Analysis

The study allows observation of how the biopolymeric film undergoes weight loss as a function of increasing temperature. This information is critical for understanding the material's thermal decomposition, degradation points, and the overall thermal stability of the film.

By subjecting the biopolymeric film to thermal analysis, deep insights into its behavior in extreme temperature environments can be obtained. These findings are particularly valuable for applications where exposure to temperature variations is anticipated, such as in packaging and transportation, or in any other scenario where thermal stability is a critical factor. In this context, [

27] highlight the importance of the weight loss of the biopolymeric film as a function of increasing temperature, and their thermal analysis is found in the section discussing the thermal degradation and thermal stability of biopolymers.

4.5. Future Optimization and Applications:

While the biopolymeric film exhibits certain limitations, such as low tensile strength and irregular morphology, these characteristics can be optimized for specific applications. Future research and development efforts could focus on refining the film's formulation, addressing morphological irregularities, and exploring novel applications where its unique combination of properties, including high biodegradability and UV-blocking capability, can be harnessed effectively, as demonstrated [

28] in their research.

The overall findings emphasize the sustainability implications of the biopolymeric membrane. Its low environmental impact, high biodegradability, and potential applications in UV protection align with the growing emphasis on sustainable materials in various industries, fact also supported by [

28] in their research. Future endeavors in this domain can contribute to the ongoing shift towards eco-conscious practices in material science and product development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.S. and A.G.; methodology, A.A.S. and G.R.; validation, D.C., J.C. and J.P.P.M.; formal analysis, A.G. and G.R., V.L.; investigation, G.R.; resources, A.A.S.; data curation, A.G. and J.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.; writing—review and editing, D.C., J.P.P.M., V.L.; supervision, A.A.S. and D.C., V.L.; project administration, A.A.S.; funding acquisition, A.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja and the authors.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support given by the technicians of every laboratory that help us to reach the objectives of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Parra, D. ., Tadini, C. ., Ponce, P., & Lugao, A. . (2004). Mechanical properties and water vapor transmission in some blends of cassava starch edible films. Carbohydrate Polymers, 58(4), 475–481. [CrossRef]

- Arfat, Y. A., Ejaz, M., Jacob, H., & Ahmed, J. (2017). Deciphering the potential of guar gum/Ag-Cu nanocomposite films as an active food packaging material. Carbohydrate Polymers, 157, 65–71. [CrossRef]

- Bertuzzi, M. A., Gottifredi, J. C., & Armada, M. (2012). Mechanical properties of a high amylose content corn starch based film, gelatinized at low temperature. Campinas, 15(3), 219–227. [CrossRef]

- Piyada, K., Waranyou, S., & Thawien, W. (2013). Mechanical , thermal and structural properties of rice starch films reinforced with rice starch nanocrystals. International Food Research Journal, 20(1), 439–449.

- Rico, M., Rodríguez-Llamazares, S., Barral, L., Bouza, R., & Montero, B. (2016). Processing and characterization of polyols plasticized-starch reinforced with microcrystalline cellulose. Carbohydrate Polymers, 149(2016), 83–93. [CrossRef]

- Astuti, P., & Erprihana, A. A. (2014). Antimicrobial Edible Film from Banana Peels as Food Packaging. American Journal of Oil and Chemical Technologies, 2(2), 2365–6570.

- Torres, F. ., Troncoso, O. ., Torres, C., Díaz, D. ., & Amaya, E. (2011). Biodegradability and mechanical properties of starch films from Andean crops. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 48(4), 603–606. [CrossRef]

- Tajik, S., Maghsoudlou, Y., Khodaiyan, F., Mahdi, S., Ghasemlou, M., & Aalami, M. (2013). Soluble soybean polysaccharide : A new carbohydrate to make a biodegradable film for sustainable green packaging. Carbohydrate Polymers, 97(2), 817–824. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, A., Fabra, M. J., Talens, P., & Chiralt, A. (2012). Effect of re-crystallization on tensile, optical and water vapour barrier properties of corn starch films containing fatty acids. Food Hydrocolloids, 26(1), 302–310. [CrossRef]

- Otoni, C. G., Avena-Bustillos, R. J., Azeredo, H. M. C., Lorevice, M. V., Moura, M. R., Mattoso, L. H. C., & McHugh, T. H. (2017). Recent Advances on Edible Films Based on Fruits and Vegetables—A Review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 16(5), 1151–1169. [CrossRef]

- González-Montelongo, R., Gloria Lobo, M., & González, M. (2010). Antioxidant activity in banana peel extracts: Testing extraction conditions and related bioactive compounds. Food Chemistry, 119(3), 1030–1039. [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, A., Prasad, S., & Sharma, H. (2015). Bioplastics- utilization of waste banana peels for synthesis of polymeric films. UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI.

- D570. ASTM D 570 – 98 – Standard Test Method for Water Absorption of Plastics, 16ASTM Standards 1–4 (1985). [CrossRef]

- D882. (2014). ASTM D88 -2 Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Thin Plastic Sheeting. ASTM Standards, 14(C), 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Salarbashi, D., Tajik, S., Ghasemlou, M., Shojaee-Aliabadi, S., Noghabi, M. S., & Khaksar, R. (2013). Characterization of soluble soybean polysaccharide film incorporated essential oil intended for food packaging. Carbohydrate Polymers, 98(1), 1127–1136. [CrossRef]

- Pelissari, F., Andrade, M., Amaral, P., & Menegalli, F. (2012). Isolation and characterization of the flour and starch of plantain bananas (Musa paradisiaca). Starch/Stärke, 64, 382–391. [CrossRef]

- Ghasemlou, M., Khodaiyan, F., & Oromiehie, A. (2011). Physical, mechanical, barrier, and thermal properties of polyol-plasticized biodegradable edible film made from kefiran. Carbohydrate Polymers, 84(1), 477–483. [CrossRef]

- Lu, D. R., Xiao, C. M., & Xu, S. J. (2009). Starch-based completely biodegradable polymer materials. Express Polymer Letters, 3(6), 366–375. [CrossRef]

- Owen, T. (2000). Fundamentos de la espectroscopía UV-visible moderna Conceptos básicos (1st. ed). Berlin: Agillent technologies.

- Kuorwel, K. K., Cran, M. J., Sonneveld, K., Miltz, J., & Bigger, S. W. (2013). Water sorption and physicomechanical properties of corn starch-based films. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 128(1), 530–536. [CrossRef]

- Sanyang, M. L., Sapuan, S. M., Jawaid, M., Ishak, M. R., & Sahari, J. (2015). Effect of Plasticizer Type and Concentration on Tensile, Thermal and Barrier Properties of Biodegradable Films based on Sugar Palm (Arenga pinnata) starch. International Journal of Polymer Analysis and Characterization, 20(7), 627–636. [CrossRef]

- Vega, D., Villar, M. A., Failla, M. D., & Vallés, E. M. (1996). Thermogravimetric analysis of starch-based biodegradable blends. Polymer Bulletin, 37, 229–235. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M., Gabrielyan, G., Janani, M., Rachamim, M., & Gilbert, R. G. (2023). Biopolymeric Membranes: Properties, Performance, and Applications in Food Packaging. Foods, 12(12), 2422. [CrossRef]

- Vonnie, J. M., Rovina, K., Azhar, R. A., Huda, N., Erna, K. H., Felicia, W. X. L., Nur’Aqilah, M. N., & Halid, N. F. A. (2022). Development and Characterization of the Biodegradable Film Derived from Eggshell and Cornstarch. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 13(2), 67. [CrossRef]

- Mamba, F. B., Mbuli, B. S., & Ramontja, J. (2021). Recent advances in biopolymeric membranes towards the removal of emerging organic pollutants from water. Membranes, 11(11), 798. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, Cai, J., Hafeez, M. A., Wang, Q., Farooq, S., Huang, Q., Tian, W., & Xiao, J. (2022). Biopolymer-based functional films for packaging applications: A review. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9, 1000116. [CrossRef]

- Dirpan, A., Ainani, A. F., & Djalal, M. (2023). A review on biopolymer-based biodegradable film for food packaging: Trends over the last decade and future research. Polymers, 15(13), 2781. [CrossRef]

- Botalo, A., Inprasit, T., Ummartyotin, S., Chainok, K., Vatthanakul, S., & Pisitsak, P. (2024). Smart and UV-resistant edible coating and films based on alginate, whey protein, and curcumin. Polymers, 16(4), 447. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).