Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

08 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The exosomes are a class of multi-vesicular bodies structures that originated from the cytoplasmic nucleus endosome, which can be synthesized by different cells and released into the extracellular environment. Breast cancer-derived exosomes can promote breast cancer proliferation, metastasis, escape and angiogenesis, which plays a significant role in the occurrence and development of breast cancer. In this article, we mainly review the roles of breast cancer-derived exosomes in tumor progression and immune suppression from the following aspects. Firstly, the exosomes are mainly introduced, including structure, formation mechanism and analytics. Then it describes the effect of the breast cancer-derived exosomes in the tumor microenvironment, and the applications of exosomes in biomedicine. For example, the applications of the breast cancer-derived exosomes as a biomarker and the value of exosomes in breast cancer treatment and prognostic. Finally, the application potential of the breast cancer-derived exosomes in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment is summarized and prospected, which provides a new idea for the accurate treatment of breast cancer.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Structure and biological function of exosomes

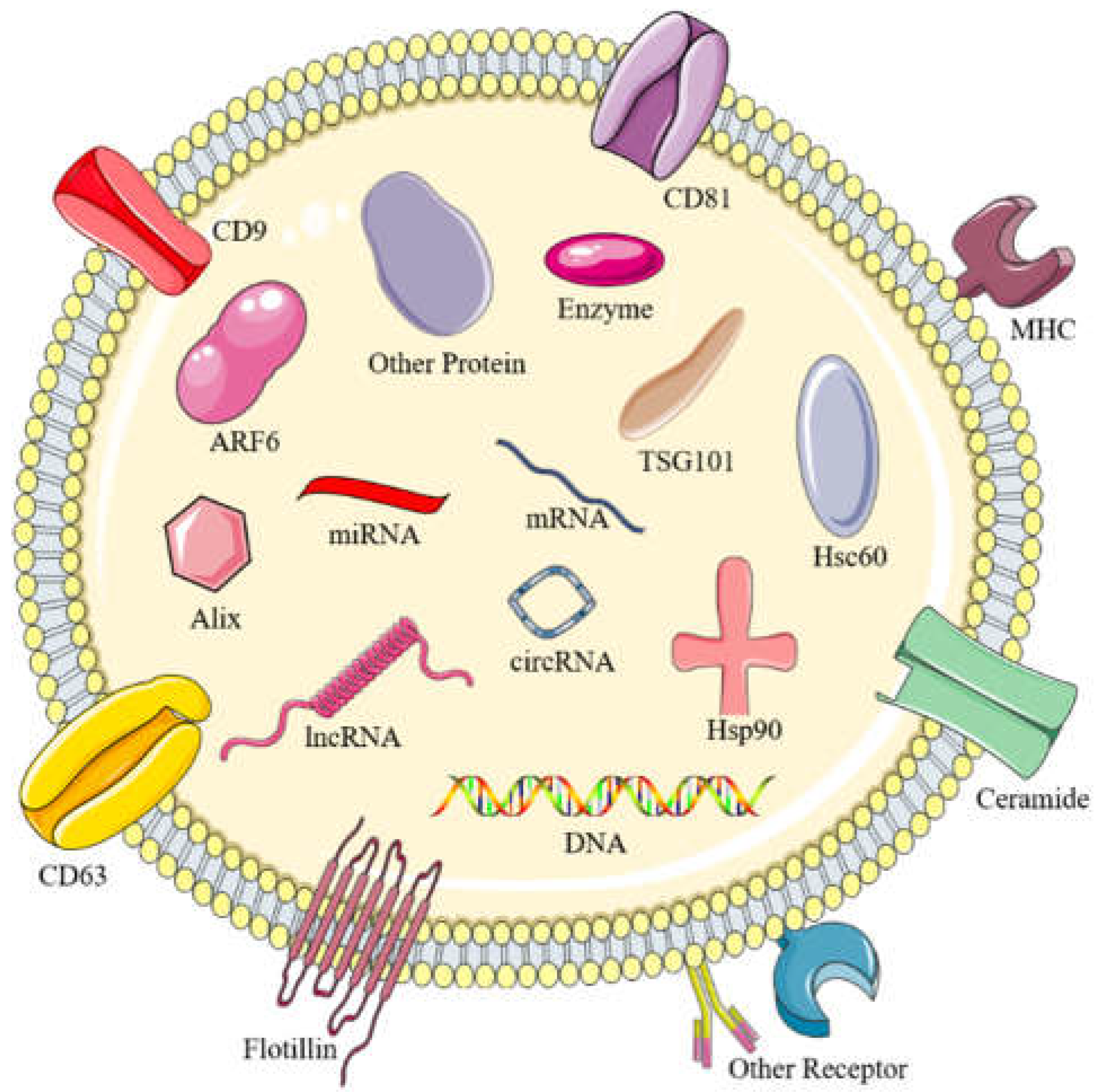

2.1. The structure of exosomes

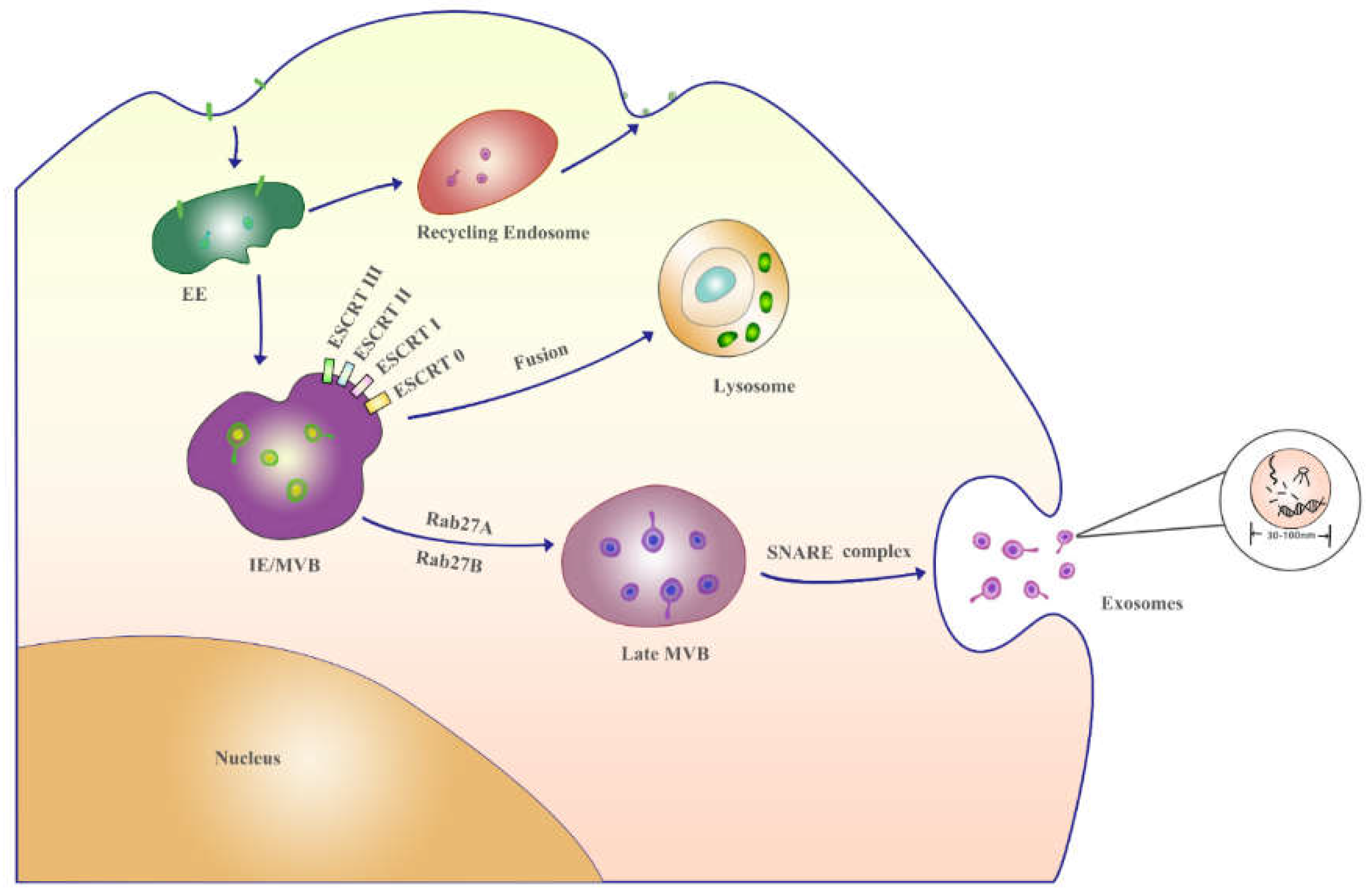

2.2. The formation mechanism and analytics of exosomes

3. Exosomes in cancer development

3.1. Growth and proliferation

3.2. Migration and invasion

3.3. Immune evasion

3.4. Drug resistance

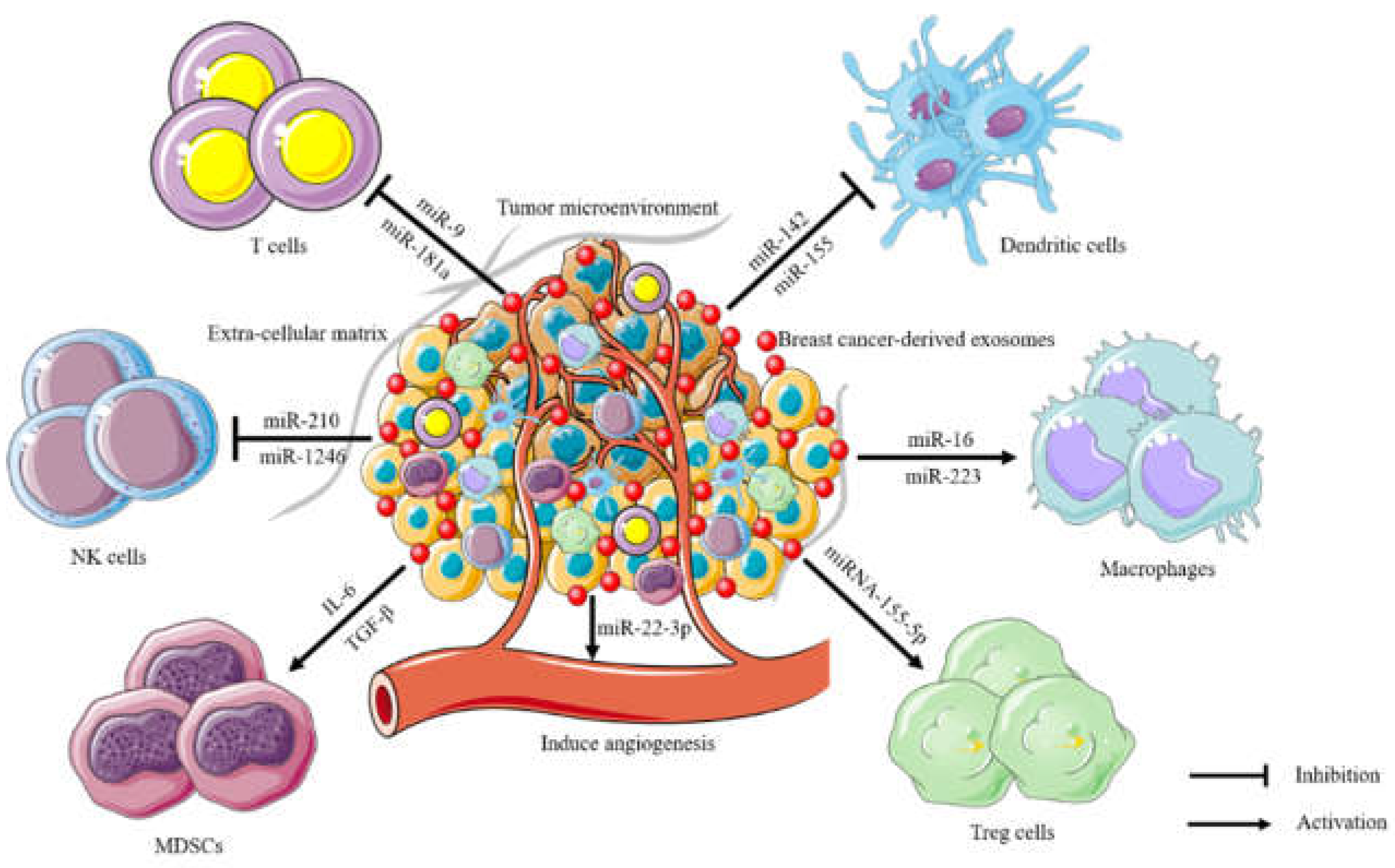

4. The immune suppression of breast cancer-derived exosomes in the tumor microenvironment

5. Applications of breast cancer-derived exosomes in biomedicine

5.1. Breast cancer-derived exosomes as a biomarker

5.2. The value of breast cancer-derived exosomes in cancer treatment and prognostic

6. Summary and prospect

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EVs | Extracellular vesicles |

| MVBs | multi-vesicular bodies |

| ILVs | intraluminal vesicles |

| MPs | microparticles |

| MVs | microvesicles |

| exRNAs | extracellular RNAs |

| exo-ncRNAs | Exosomal non-coding RNAs |

| exo-miRNAs | exosomal microRNAs |

| lncRNAs | long noncoding RNAs |

| CDK6 | cyclin-dependent kinase 6 |

| 3'- UTR | 3'- untranslated region |

| MVB | multi-vesicular body |

| ILV | intraluminal vesicles |

| ESCRT | endosomal sorting complexes required for transport |

| UB | ubiquitin |

| SEM | scanning electron microscope |

| TEM | transmission electron microscope |

| AFM | atomic force microscope |

| ELISA | enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| DLS | dynamic light scattering |

| NTA | nanoparticle tracking analysis |

| AFMM | atomic force microscopy measurements |

| SPIR | single-particle interferometric reflectance |

| EE | early endosomes |

| MVB | multivesicular body |

| TME | tumor microenvironment |

| MBF | macrophage balance fraction |

| JAK | Janus Kinase |

| STAT | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| SOCS3 | suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 |

| PIAS3 | protein inhibitors of activated STAT3 |

| eMDSCs | early-stage myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| PD-L1 | programmed death-ligand 1 |

| MAGI2 | membrane-associated guanylate kinase inverted 2 |

| PTEN | phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| ATG5 | autophagy-related 5 |

| EMT | epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| CAF | cancer-associated fibroblast |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhong, F.; Wang, D.; Zhao, Y.; Peng, D.; Li, S.; Ning, Q.; Tang, S.; Yu, C.; Wei, H. Dual gatekeepers-modified mesoporous organic silica nanoparticles for synergistic photothermal-chemotherapy of breast cancer. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2023, 646, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, M. A.; Savas, P.; Virassamy, B.; O'Malley, M.; Kay, J.; Mueller, S. N.; Mackay, L. K.; Salgado, R.; Loi, S. Towards targeting the breast cancer immune microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2024, 24, 554–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Neill, R.S.; Stoita, A. Biomarkers in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer: Are we closer to finding the golden ticket? World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 4045–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.I.; Jiao, J.; Kwan, S.Y.; Veillon, L.; Warmoes, M.O.; Tan, L.; Odewole, M.; Rich, N.E.; Wei, P.; Lorenzi, P.L.; Singal, A.G.; Beretta, L. Lipidomic Profiles of Plasma Exosomes Identify Candidate Biomarkers for Early Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with Cirrhosis. Cancer Prev. Res. 2021, 14, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skotland, T.; Sandvig, K.; Llorente, A. Lipids in exosomes: Current knowledge and the way forward. Prog. Lipid Res. 2017, 66, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A.; Moradi Binabaj, M. Exosomes: Emerging modulators of signal transduction in colorectal cancer from molecular understanding to clinical application. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 141, 111882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, M.; Jafari, R.; Mahmoodi, M.; Rezaie, J. The tumorigenic and therapeutic functions of exosomes in colorectal cancer: Opportunity and challenges. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2021, 39, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, E.A.; Sajjad, N.; Thokar, F.M. Current advancement of exosomes as biomarkers for cancer diagnosis and forecasting. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2021, 28, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boriachek, K.; Islam, M.N.; Möller, A.; Salomon, C.; Nguyen, N.T.; Hossain, M.S.A.; Yamauchi, Y.; Shiddiky, M.J.A. Biological Functions and Current Advances in Isolation and Detection Strategies for Exosome Nanovesicles. Small 2018, 14, 02153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo-da-Silva, J.; Santiago, V.F.; Rosa-Fernandes, L.; Marinho, C.R.F.; Palmisano, G. Protein glycosylation in extracellular vesicles: Structural characterization and biological functions. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 135, 226–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, G.P.; Camara, H.; Fazolini, N.P.B.; Mori, M.A. Extracellular miRNAs in redox signaling: Health, disease and potential therapies. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 173, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebeyehu, A.; Kommineni, N.; Meckes, D.G.; Sachdeva, M.S. Role of Exosomes for Delivery of Chemotherapeutic Drugs. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 2021, 38, 53–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, V.; Kumar, H.; Anod, H.V.; Chand, P.; Gupta, N.V.; Dey, S.; Kesharwani, S.S. A review of nanotechnology-based approaches for breast cancer and triple-negative breast cancer. J. Control Release 2020, 326, 628–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huyan, T.; Li, H.; Peng, H.; Chen, J.; Yang, R.; Zhang, W.; Li, Q. Extracellular Vesicles - Advanced Nanocarriers in Cancer Therapy: Progress and Achievements. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 6485–6502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmi, A.S.; Bao, B.; Sarkar, F.H. Exosomes in cancer development, metastasis, and drug resistance: A comprehensive review. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2013, 32, 623–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, C.V.; Heuser, J.E.; Stahl, P.D. Exosomes: Looking back three decades and into the future. J Cell Biol 2013, 200, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- yorgy, B.; Szabo, T.G.; Pasztoi, M.; Pal, Z.; Misjak, P.; Aradi, B.; Laszlo, V.; Pallinger, E.; Pap, E.; Kittel, A.; Nagy, G.; Falus, A.; Buzas, E.I. Membrane vesicles, current state-of-the-art: Emerging role of extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2011, 68, 2667–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, S.; Hughes, T.A.; Priya, S. Exosomes and exosomal RNAs in breast cancer: A status update. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 144, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowal, J.; Tkach, M.; Thery, C. Biogenesis and secretion of exosomes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014, 29, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Chen, Y.; Li, A.; Tan, C.; Liu, X. Exosomes play roles in sequential processes of tumor metastasis. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 1486–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaro-Ibanez, E.; Faruqu, F.N.; Saleh, A.F.; Silva, A.M.; Tzu-WenWang, J.; Rak, J.; Al-Jamal, K.T.; Dekker, N. Selection of Fluorescent, Bioluminescent, and Radioactive Tracers to Accurately Reflect Extracellular Vesicle Biodistribution in Vivo. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 3212–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, X. The emerging roles and therapeutic potential of exosomes in epithelial ovarian cancer. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.T.; Kim, Y.J.; Bu, J.; Cho, Y.H.; Han, S.W.; Moon, B.I. High-purity capture and release of circulating exosomes using an exosome-specific dual-patterned immunofiltration (ExoDIF) device. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 13495–13505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, B.K.; Zhang, H.; Becker, A.; Matei, I.; Huang, Y.; Costa-Silva, B.; Zheng, Y.; Hoshino, A.; Brazier, H.; Xiang, J.; Williams, C.; Rodriguez-Barrueco, R.; Silva, J.M.; Zhang, W.; Hearn, S.; Elemento, O.; Paknejad, N.; Manova-Todorova, K.; Welte, K.; Bromberg, J.; Peinado, H.; Lyden, D. Double-stranded DNA in exosomes: A novel biomarker in cancer detection. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 766–769. [Google Scholar]

- Sansone, P.; Savini, C.; Kurelac, I.; Chang, Q.; Amato, L.B.; Strillacci, A.; Stepanova, A.; Iommarini, L.; Mastroleo, C.; Daly, L.; Galkin, A.; Thakur, B.K.; Soplop, N.; Uryu, K.; Hoshino, A.; Norton, L.; Bonafe, M.; Cricca, M.; Gasparre, G.; Lyden, D.; Bromberg, J. Packaging and transfer of mitochondrial DNA via exosomes regulate escape from dormancy in hormonal therapy-resistant breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E9066–E9075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, V.C.; Yu, C.C. Cancer-Derived Exosomes: Their Role in Cancer Biology and Biomarker Development. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 8019–8036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegtel, D.M.; Gould, S.J. Exosomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019, 88, 487–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon-Riveros, A.; Lopez, L.; Villegas, E.V.; Antonia Rodriguez, J. Regulation of Antitumor Immune Responses by Exosomes Derived from Tumor and Immune Cells. Cancers 2021, 13, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Zhan, W.; Gao, Y.; Huang, L.; Gong, R.; Wang, W.; Zhang, R.; Wu, Y.; Gao, S.; Kang, T. RAB31 marks and controls an ESCRT-independent exosome pathway. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Niel, G.; Porto-Carreiro, I.; Simoes, S.; Raposo, G. Exosomes: A common pathway for a specialized function. J. Biochem. 2006, 140, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.C.; Zelarayan, L.C. The Mingle-Mangle of Wnt Signaling and Extracellular Vesicles: Functional Implications for Heart Research. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2018, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, M.; Sharifi, M. Exosomal miRNAs as novel cancer biomarkers: Challenges and opportunities. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 6370–6380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poliakov, A.; Spilman, M.; Dokland, T.; Amling, C.L.; Mobley, J.A. Structural heterogeneity and protein composition of exosome-like vesicles (prostasomes) in human semen. Prostate 2009, 69, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGough, I.J.; Vincent, J.P. Exosomes in developmental signalling. Development 2016, 143, 2482–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushati, N.; Cohen, S.M. microRNA functions. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2007, 23, 175–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobre, E.G.; Dinescu, S.; Costache, M. Connecting the Missing Dots: ncRNAs as Critical Regulators of Therapeutic Susceptibility in Breast Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemipour, M.; Boroumand, H.; Mollazadeh, S.; Tajiknia, V.; Nourollahzadeh, Z.; RohaniBorj, M.; Pourghadamyari, H.; Rahimian, N.; Hamblin, M.R.; Mirzaei, H. Exosomal microRNAs and exosomal long non-coding RNAs in gynecologic cancers. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 161, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Mu, J.; Yang, D.; Gu, X.; Zhang, J. Exosomal miR-21-5p contributes to ovarian cancer progression by regulating CDK6. Hum. Cell 2021, 34, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, J.; Du, L.; Gao, R.; Shen, L.; Wang, D.; Kang, L.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yue, S.; Feng, S.; Xiang, R.; Mi, X.; Tan, X. Cancer-derived exosomal miR-138-5p modulates polarization of tumor-associated macrophages through inhibition of KDM6B. Theranostics 2021, 11, 6847–6859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso-Quezada, J.; Ayala-Mar, S.; Gonzalez-Valdez, J. The role of lipids in exosome biology and intercellular communication: Function, analytics and applications. Traffic 2021, 22, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, J.; Su, Y.; Zhong, S.; Cong, L.; Liu, B.; Yang, J.; Tao, Y.; He, Z.; Chen, C.; Jiang, Y. Exosomes: Key players in cancer and potential therapeutic strategy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, A.; Gupta, S.; Mazumder, P.B. Exosomes: A new horizon in modern medicine. Life Sci. 2021, 264, 118623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashouri, L.; Yousefi, H.; Aref, A.R.; Ahadi, A.M.; Molaei, F. Alahari, S.K. Exosomes: Composition, biogenesis, and mechanisms in cancer metastasis and drug resistance. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowda, R.; Robertson, B.M.; Iyer, S.; Barry, J.; Dinavahi, S.S.; Robertson, G.P. The role of exosomes in metastasis and progression of melanoma. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2020, 85, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, K.; Chen, Y.; Wu, X.; Chen, Z.; Cao, K.; Tao, Y.; Chen, X.; Liao, J.; Zhou, J. Exosomes and Their Role in Cancer Progression. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 639159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.L.; Zhu, J.; Liu, J.X.; Jiang, F.; Ni, W.K.; Qu, L.S.; Ni, R.Z.; Lu, C.H.; Xiao, M.B. A Comparison of Traditional and Novel Methods for the Separation of Exosomes from Human Samples. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 3634563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandham, S.; Su, X.; Wood, J.; Nocera, A.L.; Alli, S.C.; Milane, L.; Zimmerman, A.; Amiji, M.; Ivanov, A.R. Technologies and Standardization in Research on Extracellular Vesicles. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1066–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschmann, D.; Mussack, V.; Byrd, J.B. Separation, characterization, and standardization of extracellular vesicles for drug delivery applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 174, 348–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Yu, Z.; Chen, D.; Wang, Z.; Miao, J.; Li, Q.; Zhang, D.; Song, J.; Cui, D. Progress in Microfluidics-Based Exosome Separation and Detection Technologies for Diagnostic Applications. Small 2020, 16, e1903916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Kang, B.; Son, H.Y.; Mun, B.; Huh, Y.M.; Rho, H.W.; Kang, T.; Moon, J.; Lee, J.J.; Seo, S.B.; Jang, S.; Son, S.U.; Jung, J.; Haam, S.; Lim, E.K. Microfluidic device for one-step detection of breast cancer-derived exosomal mRNA in blood using signal-amplifiable 3D nanostructure. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 197, 113753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Chopdat, R.; Li, D.; Al-Jamal, K.T. Development of a simple, sensitive and selective colorimetric aptasensor for the detection of cancer-derived exosomes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 169, 112576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.G.; Grizzle, W.E. Exosomes: A novel pathway of local and distant intercellular communication that facilitates the growth and metastasis of neoplastic lesions. Am. J. Pathol. 2014, 184, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanius, K.; Servage, K.; Orth, K. Exosomes in cancer development. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2021, 66, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liu, T.; Chen, J.; Ni, H.; Li, W. Survivin in breast cancer-derived exosomes activates fibroblasts by up-regulating SOD1, whose feedback promotes cancer proliferation and metastasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 13737–13752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Pang, B.; Li, J.; Gao, N.; Fan, T.; Li, Y. Emerging Role of Exosomes in Liquid Biopsy for Monitoring Prostate Cancer Invasion and Metastasis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 679527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakravan, K.; Babashah, S.; Sadeghizadeh, M.; Mowla, S.J.; Mossahebi-Mohammadi, M.; Ataei, F.; Dana, N.; Javan, M. MicroRNA-100 shuttled by mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes suppresses in vitro angiogenesis through modulating the mTOR/HIF-1alpha/VEGF signaling axis in breast cancer cells. Cell Oncol. 2017, 40, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cao, M.; Jiang, X.; Yao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Luo, D. Macrophage balance fraction determines the degree of immunosuppression and metastatic ability of breast cancer. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 97, 107682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Song, Y.; Zhao, B.; Xu, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Q. Cancer-derived exosomal miR-7641 promotes breast cancer progression and metastasis. Cell Commun. Signal 2021, 19, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.S.; Ma, S.; Dou, H.; Liu, F.; Zhang, S.Y.; Jiang, C.; Xiao, M.; Huang, Y.X. Breast cancer-derived exosomes regulate cell invasion and metastasis in breast cancer via miR-146a to activate cancer associated fibroblasts in tumor microenvironment. Exp. Cell Res. 2020, 391, 111983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, M.Y.; Zhou, W.; Liu, L.; Alontaga, A.Y.; Chandra, M.; Ashby, J.; Chow, A.; O'Connor, S.T.; Li, S.; Chin, A.R.; Somlo, G.; Palomares, M.; Li, Z.; Tremblay, J.R.; Tsuyada, A.; Sun, G.; Reid, M.A.; Wu, X.; Swiderski, P.; Ren, X.; Shi, Y.; Kong, M.; Zhong, W.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.E. Breast-cancer-secreted miR-122 reprograms glucose metabolism in premetastatic niche to promote metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, P.; Wang, X.P.; Luoreng, Z.M.; Yang, J.; Jia, L.; Ma, Y.; Wei, D.W. miR-223: An Effective Regulator of Immune Cell Differentiation and Inflammation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 2308–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, L.; Tao, X.; Shen, X. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes inhibit migration and invasion of breast cancer cells via miR-21-5p/ZNF367 pathway. Breast Cancer 2021, 28, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Sheng, L.; Stewart, T.; Zabetian, C.P.; Zhang, J. New windows into the brain: Central nervous system-derived extracellular vesicles in blood. Prog. Neurobiol. 2019, 175, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenbach, H.; Gahan, P.B. Exosomes in Immune Regulation. Noncoding RNA 2021, 1871, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugeratski, F.G.; Kalluri, R. Exosomes as mediators of immune regulation and immunotherapy in cancer. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 10–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, K. Roles of exosomes in cancer chemotherapy resistance, progression, metastasis and immunity, and their clinical applications (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2021, 59, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, R.; Liu, P.; Ye, Y.; Yu, W.; Guo, X.; Yu, J. Cancer exosome-derived miR-9 and miR-181a promote the development of early-stage MDSCs via interfering with SOCS3 and PIAS3 respectively in breast cancer. Oncogene 2020, 39, 4681–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Guo, J.; Yu, L.; Guo, T.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y. PD-L1(+) exosomes from bone marrow-derived cells of tumor-bearing mice inhibit antitumor immunity. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 2402–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Tu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yao, F.; Zhang, X. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced exosomal miR-27a-3p promotes immune escape in breast cancer via regulating PD-L1 expression in macrophages. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 9560–9573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansoori, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Davudian, S.; Shirjang, S.; Baradaran, B. The Different Mechanisms of Cancer Drug Resistance: A Brief Review. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 7, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jena, B.C.; Mandal, M. The emerging roles of exosomes in anti-cancer drug resistance and tumor progression: An insight towards tumor-microenvironment interaction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2021, 1875, 188488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Hu, J.; Lu, P.; Cao, H.; Yu, C.; Li, X.; Qian, X.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Han, N.; Dou, D.; Zhang, F.; Ye, M.; Yang, C.; Gu, Y.; Dong, H. Exosome-transmitted miR-567 reverses trastuzumab resistance by inhibiting ATG5 in breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Jia, G.; Ma, P.; Cang, S. Exosomal miR-4443 promotes cisplatin resistance in non-small cell lung carcinoma by regulating FSP1 m6A modification-mediated ferroptosis. Life Sci. 2021, 276, 119399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaks, V.; Kong, N.; Werb, Z. The cancer stem cell niche: How essential is the niche in regulating stemness of tumor cells? Cell Stem Cell 2015, 16, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewski, T.F.; Schreiber, H.; Fu, Y.X. Innate and adaptive immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, S.; Kim, U.; Muthukkaruppan, V.; Vanniarajan, A. Emerging role of tumor microenvironment derived exosomes in therapeutic resistance and metastasis through epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Life Sci. 2021, 280, 119750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.; Wang, X.; Gong, Z.; Yu, M.; Wu, H.; Zhang, D. Exosome-mediated metabolic reprogramming: The emerging role in tumor microenvironment remodeling and its influence on cancer progression. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhou, L.; Lv, D.; Zhu, X.; Tang, H. Exosome-mediated communication in the tumor microenvironment contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma development and progression. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Sang, Y.; Song, X.; Zhang, D.; Wang, L.; Zhao, W.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Yang, Q. Exosomal miR-500a-5p derived from cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes breast cancer cell proliferation and metastasis through targeting USP28. Theranostics 2021, 11, 3932–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Peng, C. Cancer-associated fibroblasts regulate the biological behavior of cancer cells and stroma in gastric cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, P.P.; Luo, L.J.; Chen, H.Z.; Chen, Q.T.; Bian, X.L.; Wu, S.F.; Zhou, J.X.; Zhao, W.X.; Liu, J.M.; Wang, X.M.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Yao, L.M.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, D.; Wu, Q. Ectosomal PKM2 Promotes HCC by Inducing Macrophage Differentiation and Remodeling the Tumor Microenvironment. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 1192–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi-Chaleshtori, M.; Bandehpour, M.; Soudi, S.; Mohammadi-Yeganeh, S.; Hashemi, S.M. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of anti-tumoral effect of M1 phenotype induction in macrophages by miR-130 and miR-33 containing exosomes. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2021, 70, 1323–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhong, W.; Bu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, R.; Nie, R.; Xiao, C.; Ma, K.; Huang, X.; Li, Y. Exosomal protein CD82 as a diagnostic biomarker for precision medicine for breast cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 2019, 58, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Mao, J.H.; Wang, B.Y.; Wang, L.X.; Wen, H.Y.; Xu, L.J.; Fu, J.X.; Yang, H. Exosomal miR-1910-3p promotes proliferation, metastasis, and autophagy of breast cancer cells by targeting MTMR3 and activating the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Cancer Lett. 2020, 489, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, J.; Ma, L.J.; Yang, H.B.; Jing, J.F.; Jia, M.M.; Zhang, X.J.; Guo, F.; Gao, J.N. Identification of serum exosomal miR-148a as a novel prognostic biomarker for breast cancer. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 7303–7309. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, K.; Chen, W.; Cao, R.; Xie, Y.; Wang, P.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Qin, J. Brain organoid-on-chip system to study the effects of breast cancer derived exosomes on the neurodevelopment of brain. Cell Regen. 2022, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Corbett, A.L.; Taatizadeh, E.; Tasnim, N.; Little, J.P.; Garnis, C.; Daugaard, M.; Guns, E.; Hoorfar, M.; Li, I.T.S. Challenges and opportunities in exosome research-Perspectives from biology, engineering, and cancer therapy. APL Bioeng. 2019, 3, 011503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zhuang, X.; Xiang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, C.; Barnes, S.; Grizzle, W.; Miller, D.; Zhang, H.G. A novel nanoparticle drug delivery system: The anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin is enhanced when encapsulated in exosomes. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 1606–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Li, S.; Song, J.; Ji, T.; Zhu, M.; Anderson, G.J.; Wei, J.; Nie, G. A doxorubicin delivery platform using engineered natural membrane vesicle exosomes for targeted tumor therapy. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 2383–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norouzi-Barough, L.; Shirian, S.; Gorji, A.; Sadeghi, M. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes as a cell-free therapy approach for the treatment of skin, bone, and cartilage defects. Connect. Tissue Res. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Wu, H.; Li, M.; Chen, X.; Xu, X.; Ni, W.; Lu, C.; Ni, R.; Bao, B.; Xiao, M. Progress in the application of exosomes as therapeutic vectors in tumor-targeted therapy. Cytotherapy 2019, 21, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).