Submitted:

07 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Cultivation of Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVEC)

2.2. Cancer Cell Lines Cultivation

2.3. Isolation of Exosomes from Conditioned Medium

2.4. Ethics Statement

2.5. Exosome Isolation from Blood

2.6. Characterization of Exosomes

2.7. Mass Spectrometry Analysis

2.8. Bioinformatics Analysis

3. Results

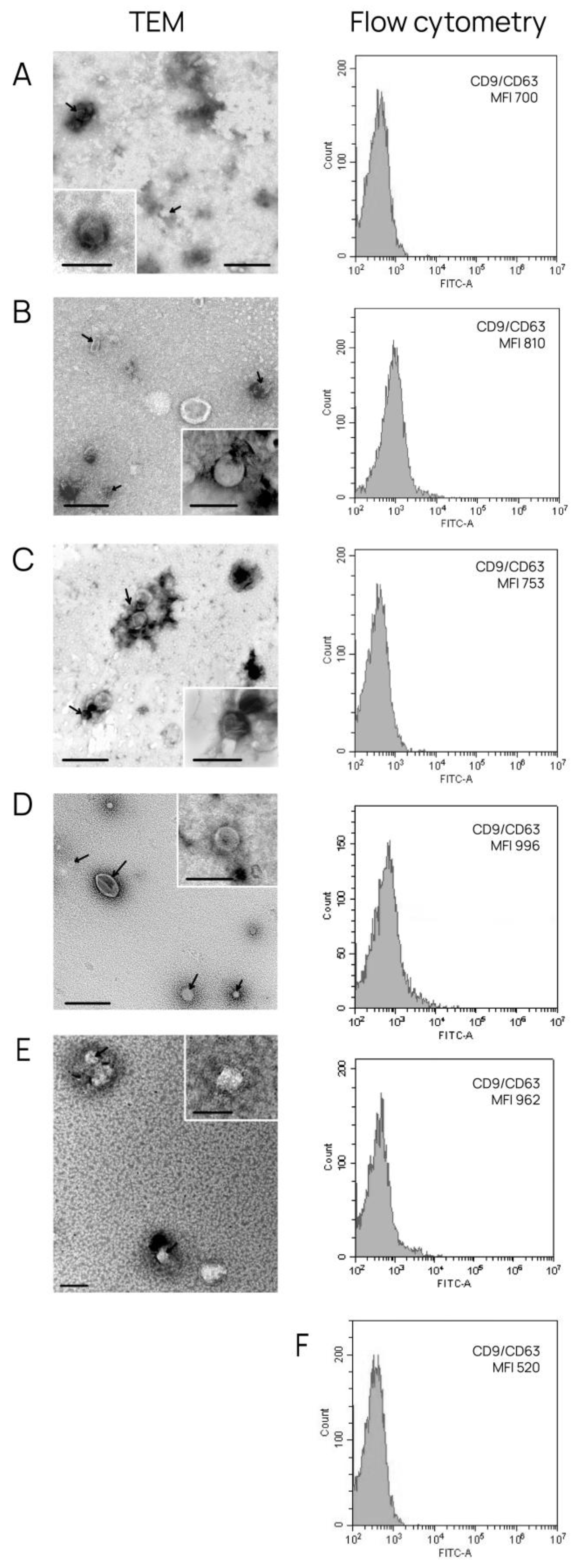

3.1. Characterization of Isolated Exosomes

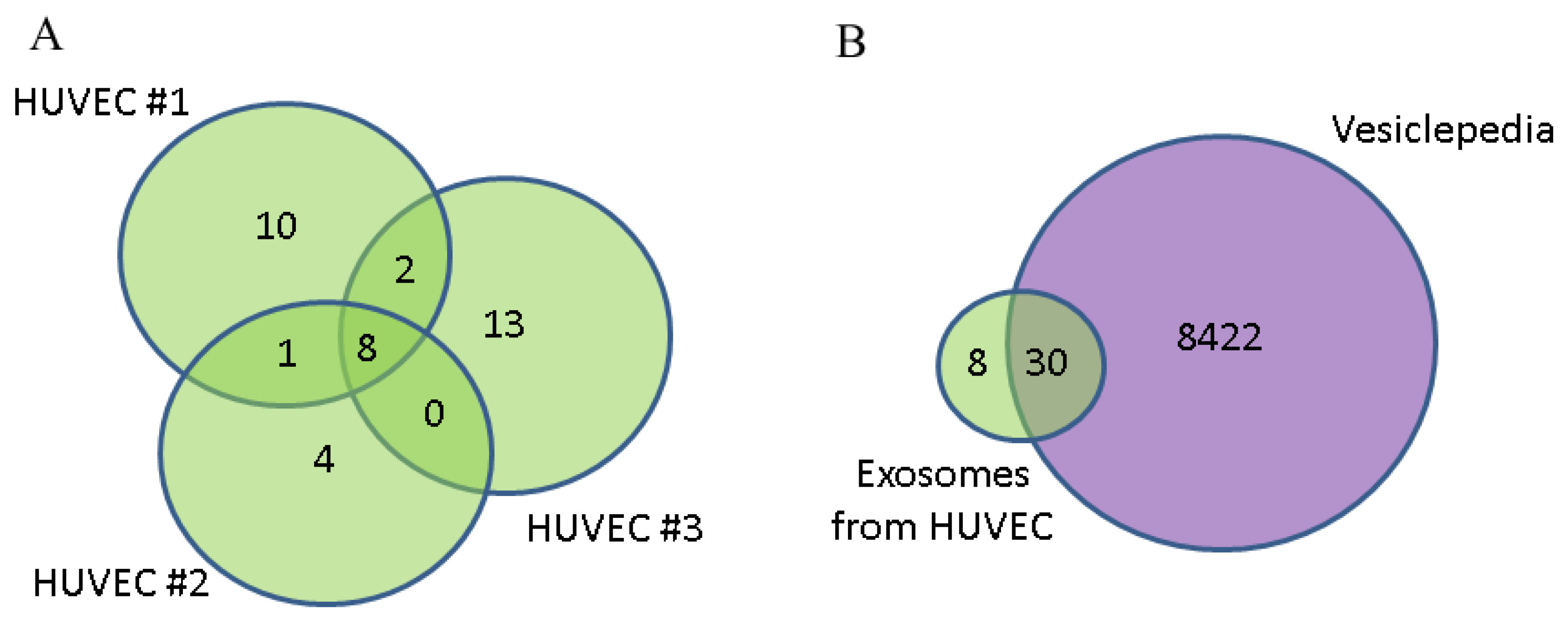

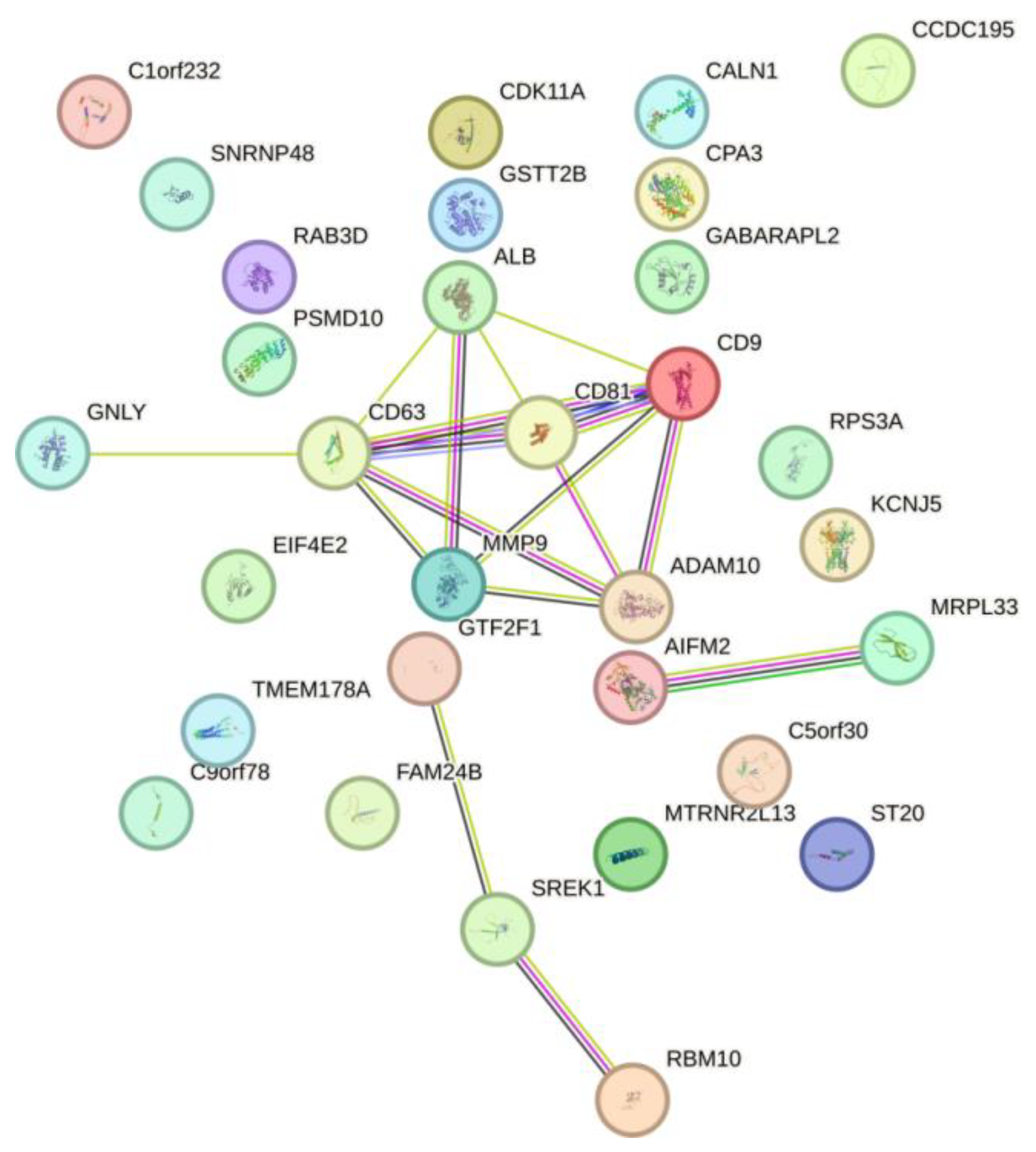

3.2. Annotation of Identified Proteins from HUVEC-Derived Exosomes

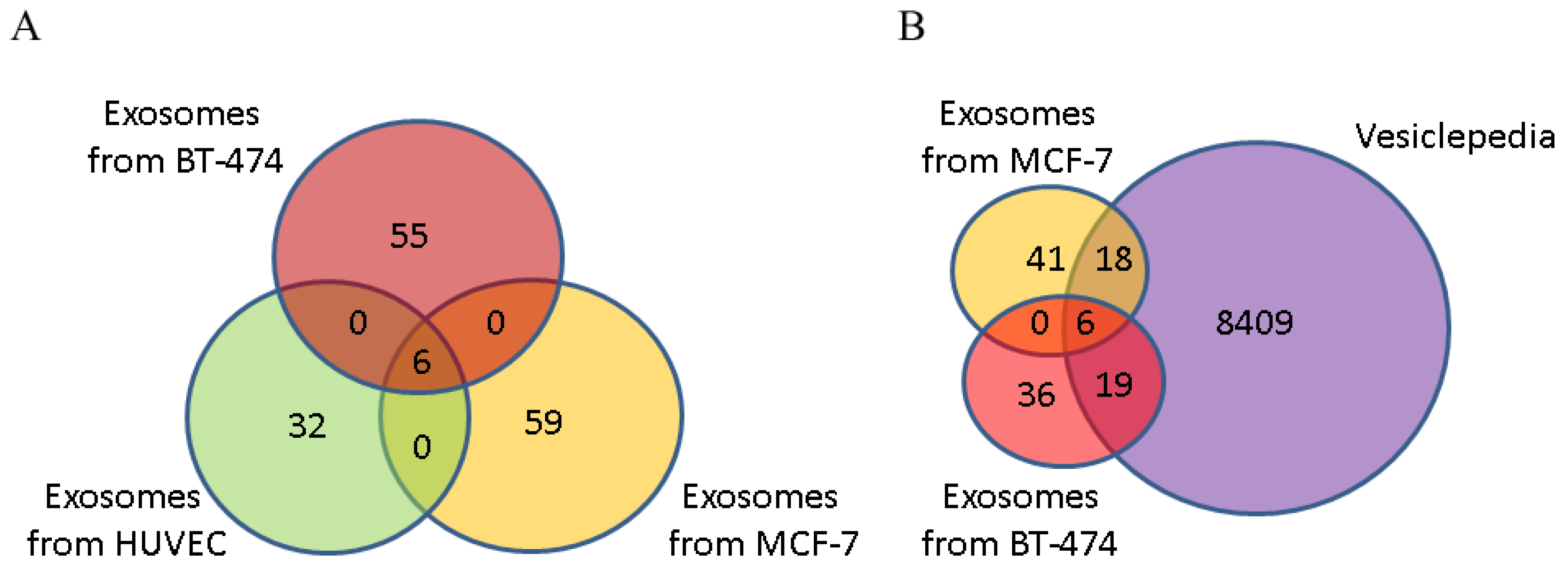

3.3. Annotation of Protein Cargo from BC-Derived Exosomes

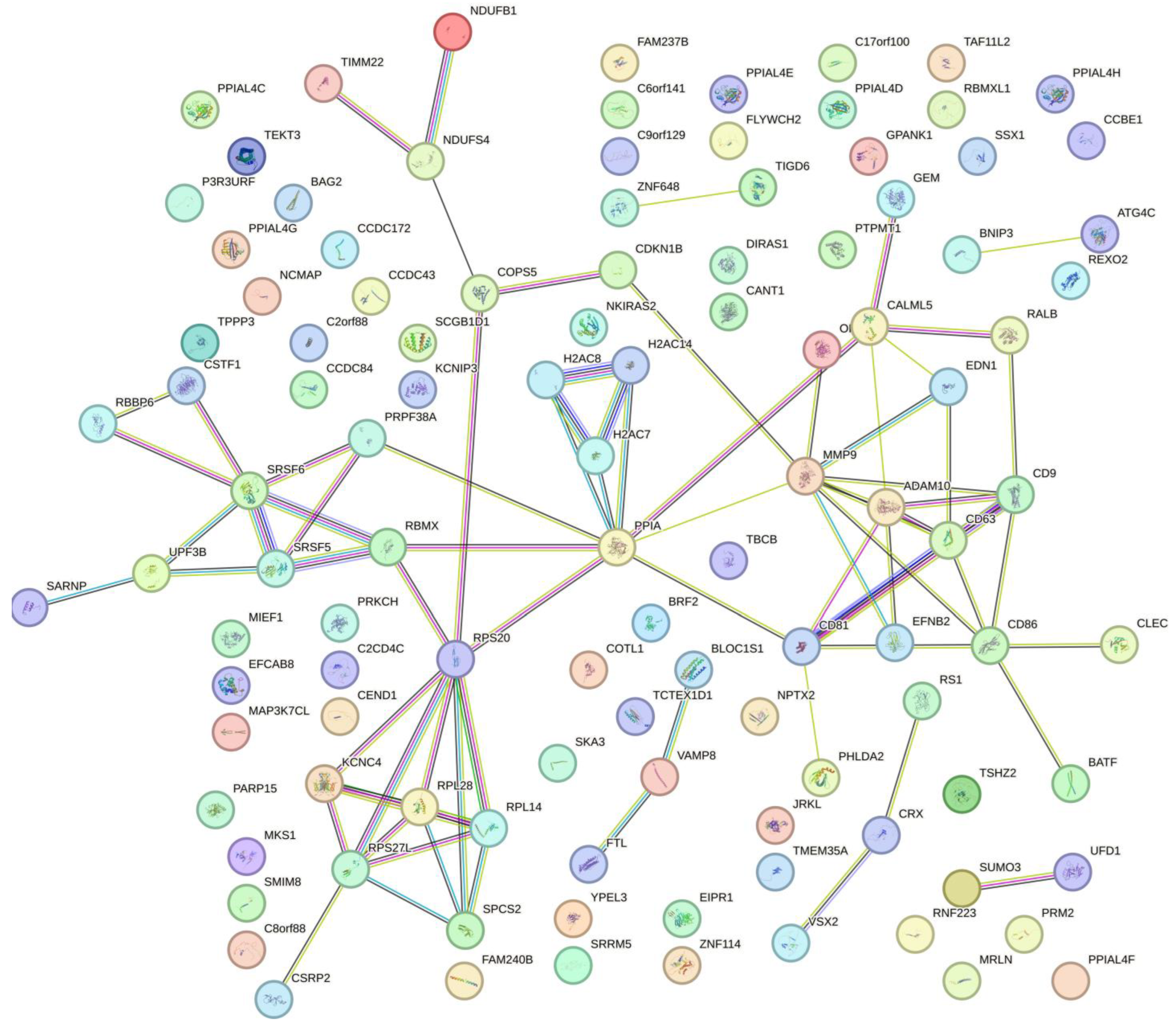

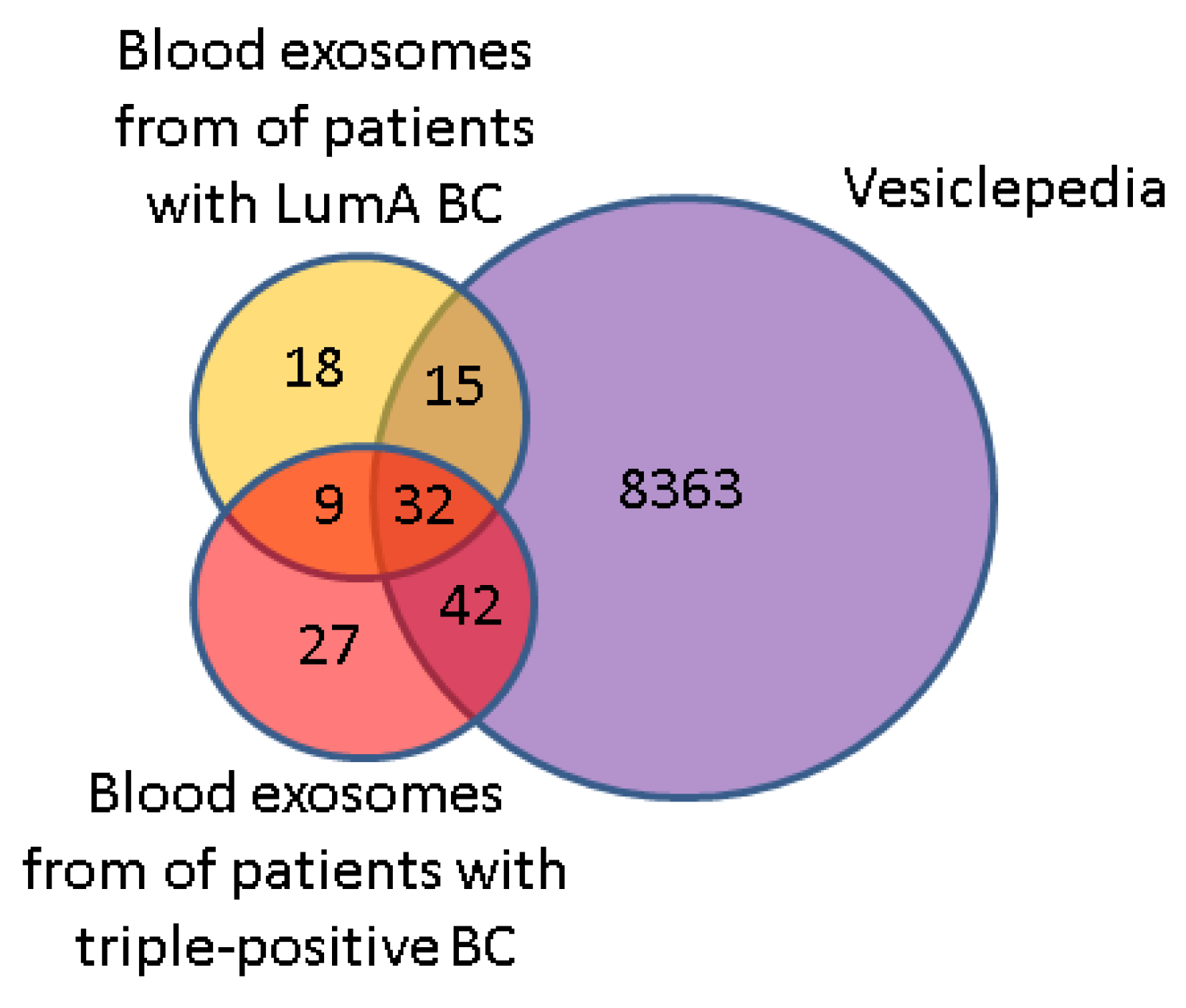

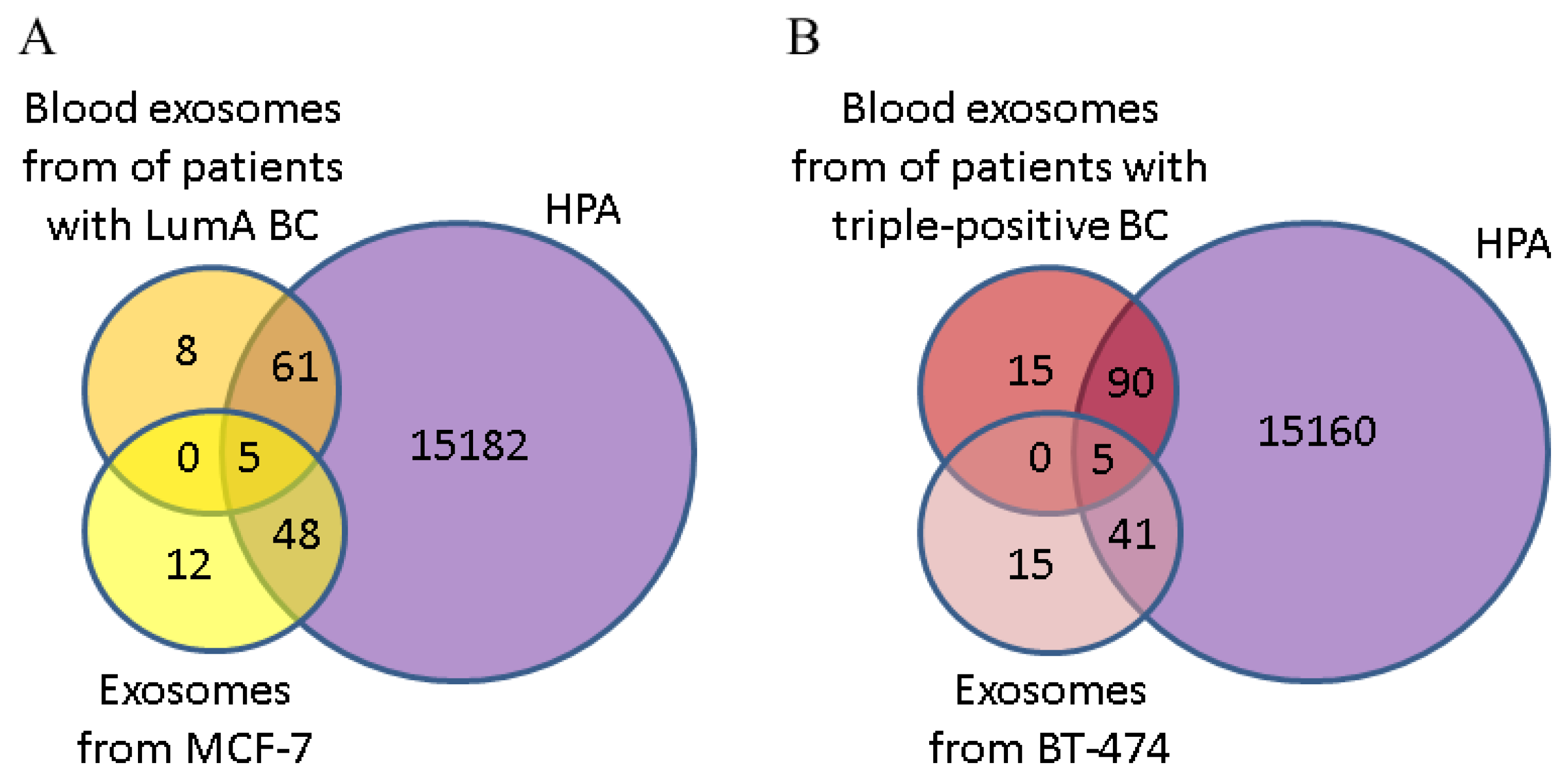

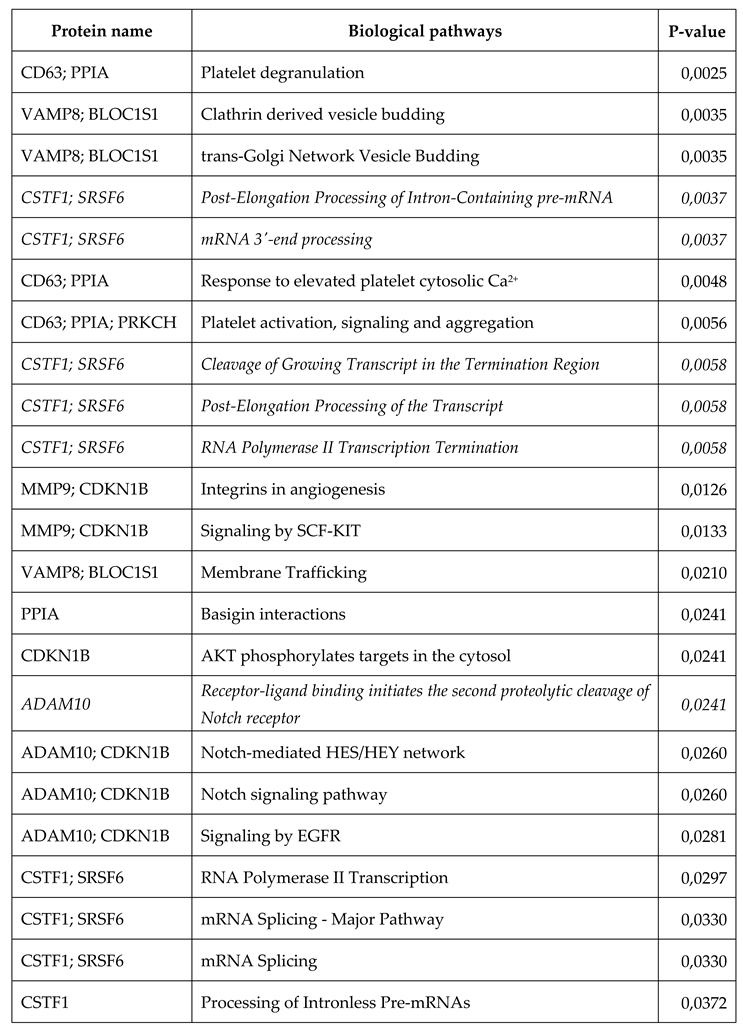

3.4. Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Exosomes in the Blood of BCPs with Luminal A and Triple-Positive Subtypes

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, Q.; Gao, H. The Role of the Tumor Microenvironment in Triple-Positive Breast Cancer Progression and Therapeutic Resistance. Cancers 2023, 15, 5493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shefer, A.; Yalovaya, A.; Tamkovich, S. Exosomes in breast cancer: Involvement in tumor dissemination and prospects for liquid biopsy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandini, E.; Rossi, T.; Scarpi, E.; Gallerani, G.; Vannini, I.; Salvi, S.; Azzali, I.; Melloni, M.; Salucci, S.; Battistelli, M.; Serra, P.; Maltoni, R.; Cho, W.C.; Fabbri, F. Early Detection and Investigation of Extracellular Vesicles Biomarkers in Breast Cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 732900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.S.; Conant, E.F.; Soo, M.S. Molecular Subtypes of Breast Cancer: A Review for Breast Radiologists. J. Breast Imaging 2021, 3, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilous, M. Breast core needle biopsy: Issues and controversies. Mod Pathol. 2010, 23 (Suppl. S2), S36–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Ni, J.; Wasinger, V.C.; Graham, P.; Li, Y. Comparison Study of Small Extracellular Vesicle Isolation Methods for Profiling Protein Biomarkers in Breast Cancer Liquid Biopsies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugeratski, F.G.; Hodge, K.; Lilla, S.; McAndrews, K.M.; Zhou, X.; Hwang, R.F.; Zanivan, S.; Kalluri, R. Quantitative proteomics identifies the core proteome of exosomes with syntenin-1 as the highest abundant protein and a putative universal biomarker. Nat. Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagu, A.-N.; Whitham, D.; Bruno, P.; Morrissiey, H.; Darie, C.A.; Darie, C.C. Omics-Based Investigations of Breast Cancer. Molecules 2023, 28, 4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risha, Y.; Minic, Z.; Ghobadloo, S.M.; Berezovski, M.V. The proteomic analysis of breast cell line exosomes reveals disease patterns and potential biomarkers. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangoda, L.; Liem, M.; Ang, C.S.; Keerthikumar, S.; Adda, C.G.; Parker, B.S.; Mathivanan, S. Proteomic Profiling of Exosomes Secreted by Breast Cancer Cells with Varying Metastatic Potential. Proteomics 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanova, A.O.; Laktionov, P.P.; Cherepanova, A.V.; Chernonosova, V.S.; Shevelev, G.Y.; Zaporozhchenko, I.A.; Karaskov, A.M.; Laktionov, P.P. General Study and Gene Expression Profiling of Endotheliocytes Cultivated on Electrospun Materials. Materials 2019, 12, 4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherepanova, A.V.; Bushuev, A.V.; Kharkova, M.V.; Vlassov, V.V.; Laktionov, P.P. DNA inhibits dsRNA-induced secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines by gingival fibroblasts. Immunobiology 2013, 218, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tutanov, O.; Orlova, E.; Proskura, K.; Grigor’eva, A.; Yunusova, N.; Tsentalovich, Y.; Alexandrova, A.; Tamkovich, S. Proteomic Analysis of Blood Exosomes from Healthy Females and Breast Cancer Patients Reveals an Association between Different Exosomal Bioactivity on Non-tumorigenic Epithelial Cell and Breast Cancer Cell Migration in Vitro. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamkovich, S.; Tutanov, O.; Efimenko, A.; Grigor'eva, A.; Ryabchikova, E.; Kirushina, N.; Vlassov, V.; Tkachuk, V.; Laktionov, P. Blood Circulating Exosomes Contain Distinguishable Fractions of Free and Cell-Surface-Associated Vesicles. Curr. Mol. Med. 2019, 19, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamkovich, S.N.; Yunusova, N.V.; Tugutova, E.; Somov, A.K.; Proskura, K.V.; Kolomiets, L.A.; Stakheeva, M.N.; Grigor’eva, A.E.; Laktionov, P.P.; Kondakova, I.V. Protease cargo in circulating exosomes of breast cancer and ovarian cancer patients. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019, 20, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebersold, R.; Mann, M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature 2003, 422, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domon, B.; Aebersold, R. Mass Spectrometry and Protein Analysis. Science 2006, 312, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suckau, D.; Resemann, A.; Schuerenberg, M.; Hufnagel, P.; Franzen, J.; Holle, A. A novel MALDI LIFT-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer for proteomics. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2003, 376, 952–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, I.A.; Machado, J.C.; Melo, S.A. Advances in exosomes utilization for clinical applications in cancer. Trends Cancer. 2024, 10, 947–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesiclepedia database. www.microvesicles.org (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Bates, M.; Mohamed, B.M.; Lewis, F.; O'Toole, S.; O'Leary, J.J. Biomarkers in high grade serous ovarian cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer. 2024, 1879, 189224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, H.; Min, L.; Bu, F.; Wang, S.; Meng, J. Recent advances of liquid biopsy: Interdisciplinary strategies toward clinical decision-making. Interdisciplinary Medicine 2023, 1, e20230021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bi, J.; Huang, J.; Tang, Y.; Du, S.; Li, P. Exosome: A Review of Its Classification, Isolation Techniques, Storage, Diagnostic and Targeted Therapy Applications. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 6917–6934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos-Amador, P.; Royo, F.; Gonzalez, E.; Conde-Vancells, J.; Palomo-Diez, L.; Borras, F.E.; Falcon-Perez, J.M. Proteomic analysis of microvesicles from plasma of healthy donors reveals high individual variability. J. Proteomics 2012, 75, 3574–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rontogianni, S.; Synadaki, E.; Li, B.; Liefaard, M.C.; Lips, E.H.; Wesseling, J.; Wu, W.; Altelaar, M. Proteomic profiling of extracellular vesicles allows for human breast cancer subtyping. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A.; Kim, H.S.; Bojmar, L.; Gyan, K.E.; Cioffi, M.; Hernandez, J.; Zambirinis, C.P.; Rodrigues, G.; Molina, H.; Heissel, S.; Mark, M.T.; Steiner, L.; Benito-Martin, A.; Lucotti, S.; Di Giannatale, A.; Offer, K.; Nakajima, M.; Williams, C.; Nogués, L.; Pelissier Vatter, F.A.; Hashimoto, A.; Davies, A.E.; Freitas, D.; Kenific, C.M.; Ararso, Y.; Buehring, W.; Lauritzen, P.; Ogitani, Y.; Sugiura, K.; Takahashi, N.; Alečković, M.; Bailey, K.A.; Jolissant, J.S.; Wang, H.; Harris, A.; Schaeffer, L.M.; García-Santos, G.; Posner, Z.; Balachandran, V.P.; Khakoo, Y.; Raju, G.P.; Scherz, A.; Sagi, I.; Scherz-Shouval, R.; Yarden, Y.; Oren, M.; Malladi, M.; Petriccione, M.; De Braganca, K.C.; Donzelli, M.; Fischer, C.; Vitolano, S.; Wright, G.P.; Ganshaw, L.; Marrano, M.; Ahmed, A.; DeStefano, J.; Danzer, E.; Roehrl, M.H.A.; Lacayo, N.J.; Vincent, T.C.; Weiser, M.R.; Brady, M.S.; Meyers, P.A.; Wexler, L.H.; Ambati, S.R.; Chou, A.J.; Slotkin, E.K.; Modak, S.; Roberts, S.S.; Basu, E.M.; Diolaiti, D.; Krantz, B.A.; Cardoso, F.; Simpson, A.L.; Berger, M.; Rudin, C.M.; Simeone, D.M.; Jain, M.; Ghajar, C.M.; Batra, S.K.; Stanger, B.Z.; Bui, J.; Brown, K.A.; Rajasekhar, V.K.; Healey, J.H.; de Sousa, M.; Kramer, K.; Sheth, S.; Baisch, J.; Pascual, V.; Heaton, T.E.; La Quaglia, M.P.; Pisapia, D.J.; Schwartz, R.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Shukla, A.; Blavier, L.; DeClerck, Y.A.; LaBarge, M.; Bissell, M.J.; Caffrey, T.C.; Grandgenett, P.M.; Hollingsworth, M.A.; Bromberg, J.; Costa-Silva, B.; Peinado, H.; Kang, Y.; Garcia, B.A.; O'Reilly, E.M.; Kelsen, D.; Trippett, T.M.; Jones, D.R.; Matei, I.R.; Jarnagin, W.R.; Lyden, D. Extracellular Vesicle and Particle Biomarkers Define Multiple Human Cancers. Cell 2020, 182, 1044–1061.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerashchenko, T.S.; Zavyalova, M.V.; Denisov, E.V.; Krakhmal, N.V.; Pautova, D.N.; Litviakov, N.V.; Vtorushin, S.V.; Cherdyntseva, N.V.; Perelmuter, V.M. Intratumoral Morphological Heterogeneity of Breast Cancer as an Indicator of the Metastatic Potential and Tumor Chemosensitivity. Acta Naturae 2017, 9, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, T.; Sheta, M.; Fujii, M.; Calderwood, S.K. Cancer extracellular vesicles, tumoroid models, and tumor microenvironment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86 Pt 1, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugeratski, F.G.; Hodge, K.; Lilla, S.; McAndrews, K.M.; Zhou, X.; Hwang, R.F.; Zanivan, S.; Kalluri, R. Quantitative proteomics identifies the core proteome of exosomes with syntenin-1 as the highest abundant protein and a putative universal biomarker. Nat Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelsomino, L.; Barone, I.; Caruso, A.; Giordano, F.; Brindisi, M.; Morello, G.; Accattatis, F.M.; Panza, S.; Cappello, A.R.; Bonofiglio, D.; et al. Proteomic Profiling of Extracellular Vesicles Released by Leptin-Treated Breast Cancer Cells: A Potential Role in Cancer Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Subtype | Hormonal status | HER2/neo status | Age | T | N | M | Ki-67 | G | Infiltrative Ductal Carcinoma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luminal An = 5 | ER+PR+ | Negative | 61 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10-15% | 2 | Yes |

| 61 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 12-14% | 2 | Yes | |||

| 56 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5-10% | 2 | Yes | |||

| 59 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5-10% | 2 | Yes | |||

| 61 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5% | 2 | Yes | |||

| Triple-positiven = 8 | ER+PR+ | Positive | 52 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10% | 2 | Yes |

| 62 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10-15% | 2 | Yes | |||

| 66 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 15% | 2 | Yes | |||

| 68 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5-10% | 2 | Yes | |||

| 69 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5-10% | 2 | Yes | |||

| 44 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5% | 2 | Yes | |||

| 61 | 2 | x* | 0 | 15-17% | 2 | Yes | |||

| 67 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 20-25% | 2 | Yes |

| Protein name | Biological pathways | P-value |

| ALB | Transport of organic anions | 0,0127 |

| ALB | Recycling of bile acids and salts | 0,0139 |

| ALB | HDL-mediated lipid transport | 0,0189 |

| GTF2F1 | RNA Pol II CTD phosphorylation and interaction with CE | 0,0326 |

| RPS3A, PSMD10 | Metabolism of mRNA | 0,0333 |

| ALB | Bile acid and bile salt metabolism | 0,0338 |

| ALB | Lipoprotein metabolism | 0,0338 |

| CD81, PSMD10 | Adaptive Immune System | 0,0341 |

| GTF2F1 | mRNA Capping | 0,0351 |

| CD63 | Platelet degranulation | 0,0351 |

| MMP9 | Osteopontin-mediated events | 0,0363 |

| ALB | Transport of vitamins, nucleosides, and related molecules | 0,0375 |

| GTF2F1 | Pausing and recovery of elongation | 0,0388 |

| GTF2F1 | Elongation arrest and recovery | 0,0388 |

| GTF2F1 | Formation of the Early Elongation Complex | 0,0400 |

| CD81 | Alpha4 beta1 integrin signaling events | 0,0412 |

| CD9 | a6b1 and a6b4 Integrin signaling | 0,0437 |

| RPS3A, PSMD10 | Metabolism of RNA | 0,0466 |

| GTF2F1 | RNA Polymerase II Transcription Pre-Initiation And Promoter Opening | 0,0486 |

|

| Protein name | Biological pathways | P-value |

| RPS20; RPL28; UPF3B; RPL14 | Nonsense Mediated Decay Enhanced by the Exon Junction Complex | 0,0008 |

| RPS20; RPL28; SPCS2; RPL14 | Insulin Synthesis and Processing | 0,0019 |

| RBMX; SRSF5; RPS20; RPL28; UPF3B; RPL14 | Gene Expression | 0,0037 |

| RPS20; RPL28; RPL14 | Peptide chain elongation | 0,0045 |

| RPS20; RPL28; RPL14 | Eukaryotic Translation Termination | 0,0045 |

| RPS20; RPL28; RPL14 | Eukaryotic Translation Elongation | 0,0049 |

| RPS20; RPL28; RPL14 | Formation of a pool of free 40S subunits | 0,0062 |

| RPS20; RPL28; RPL14 | Regulation of gene expression in beta cells | 0,0074 |

| RPS20; RPL28; RPL14 | L13a-mediated translational silencing of Ceruloplasmin expression | 0,0082 |

| RPS20; RPL28; RPL14 | GTP hydrolysis and joining of the 60S ribosomal subunit | 0,0084 |

| SRSF5; UPF3B | mRNA 3'-end processing | 0,0085 |

| SRSF5; UPF3B | Post-Elongation Processing of Intron-Containing pre-mRNA | 0,0085 |

| RBMX; SRSF5; UPF3B | mRNA Splicing | 0,0094 |

| RPS20; RPL28; RPL14 | Regulation of beta-cell development | 0,0096 |

| RPS20; RPL28; RPL14 | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation | 0,0101 |

| RPS20; RPL28; RPL14 | Cap-dependent Translation Initiation | 0,0101 |

| RPS20; RPL28; RPL14 | Translation | 0,0119 |

| SRSF5; UPF3B | Post-Elongation Processing of the Transcript | 0,0134 |

| SRSF5; UPF3B | Cleavage of Growing Transcript in the Termination Region | 0,0134 |

| SRSF5; UPF3B | RNA Polymerase II Transcription Termination | 0,0134 |

| RPS20; RPL28; UPF3B; RPL14 | Metabolism of mRNA | 0,0147 |

| SRSF5; UPF3B | Transport of Mature mRNA derived from an Intron-Containing Transcript | 0,0185 |

| RBMX; SRSF5; UPF3B | Processing of Capped Intron-Containing Pre-mRNA | 0,0186 |

| TBCB; RPS20; RPL28; RPL14 | Metabolism of proteins | 0,0206 |

| RBMX; SRSF5; UPF3B | mRNA Processing | 0,0260 |

| RPS20; RPL28; UPF3B; RPL14 | Metabolism of RNA | 0,0268 |

| SRSF5; BRF2; UPF3B | Transcription | 0,0359 |

| ADAM10 | Receptor-ligand binding initiates the second proteolytic cleavage of Notch receptor | 0,0366 |

| NDUFS4; NDUFB1 | Respiratory electron transport | 0,0388 |

| RBMX; SRSF5; UPF3B | Formation and Maturation of mRNA Transcript | 0,0396 |

| MMP9; CD86; RALB | CXCR4-mediated signaling events | 0,0424 |

| BNIP3; EDN1 | Hypoxic and oxygen homeostasis regulation of HIF-1-alpha | 0,0426 |

| TBCB | Post-chaperonin tubulin folding pathway | 0,0485 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).