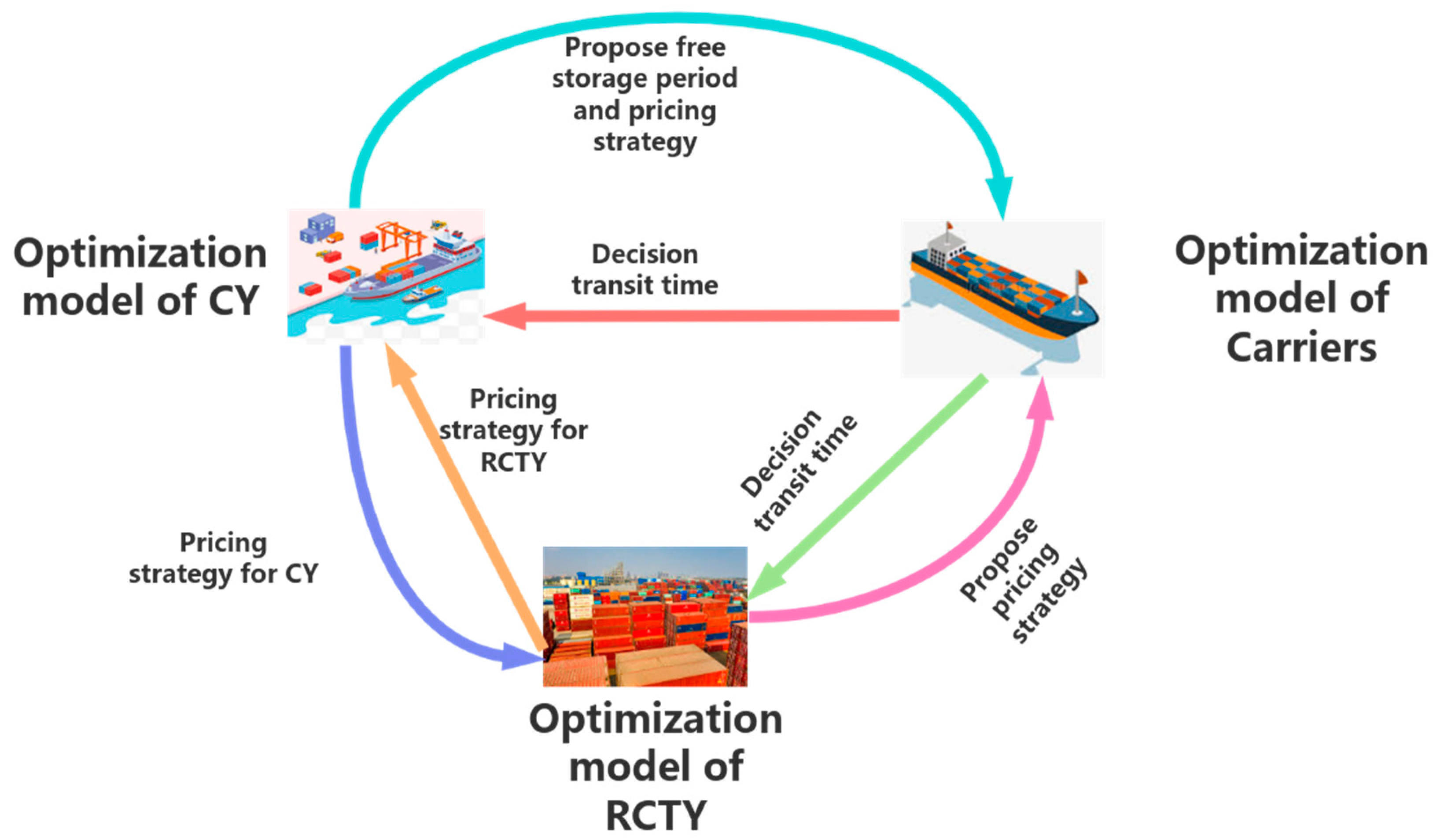

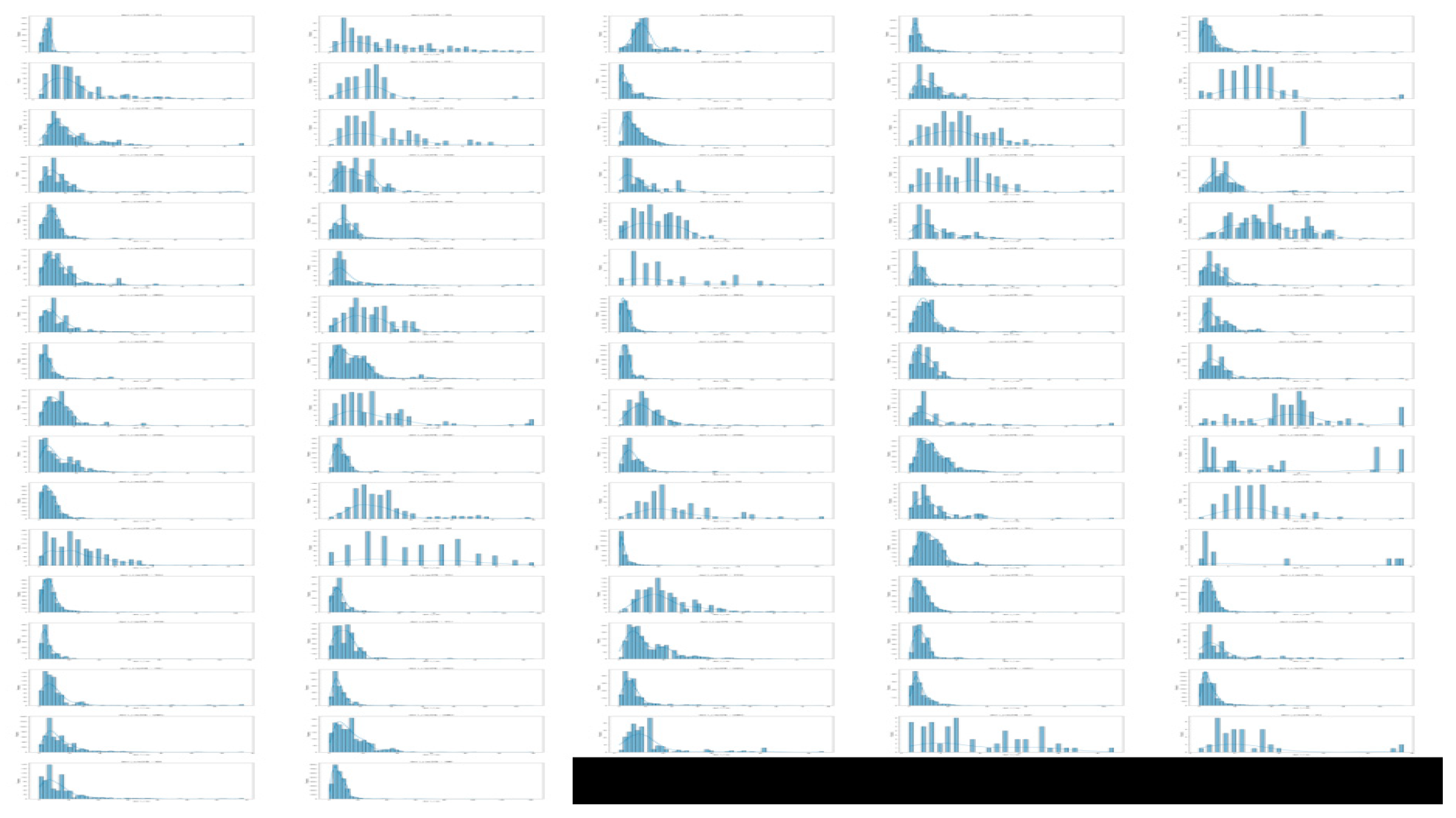

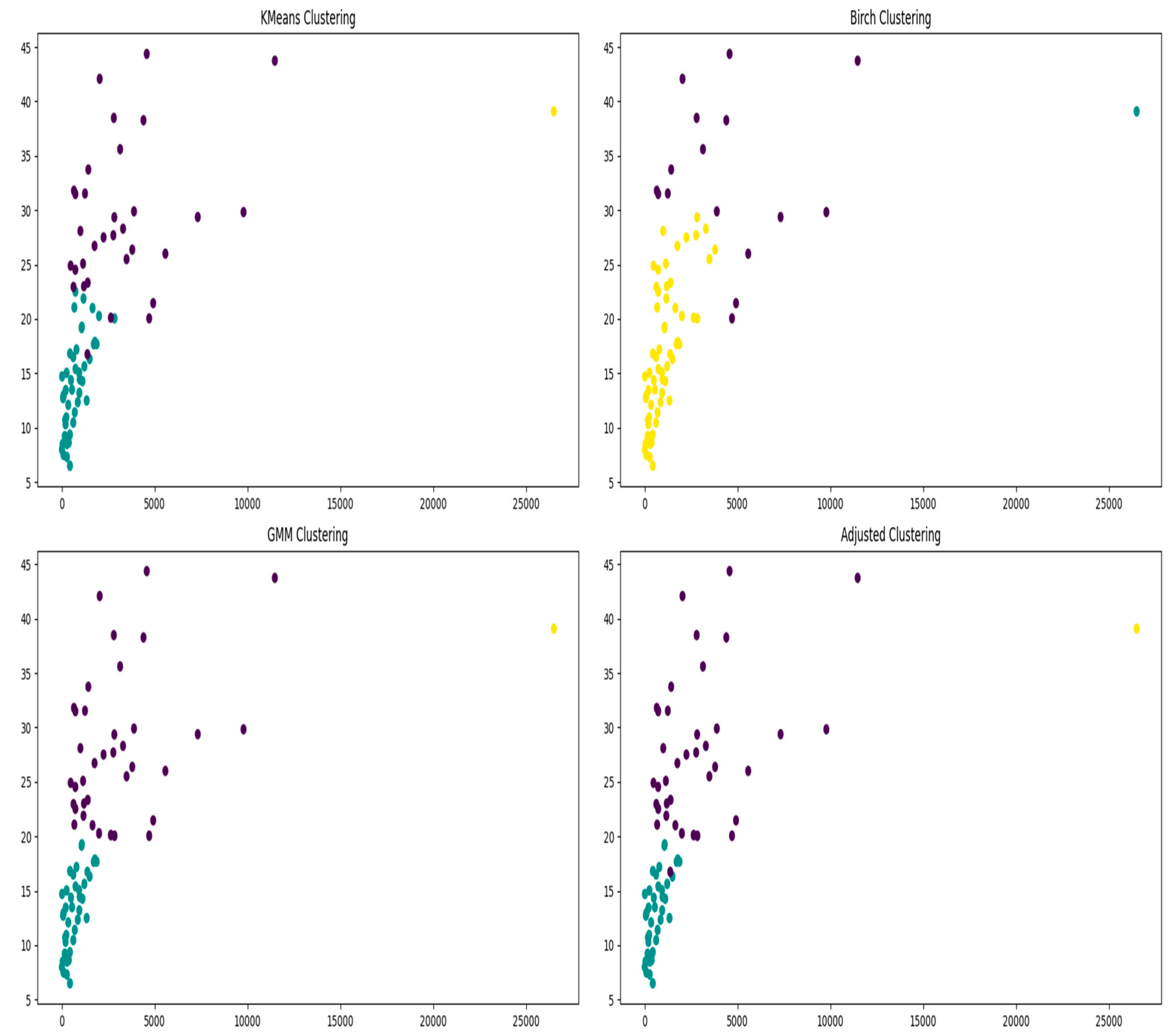

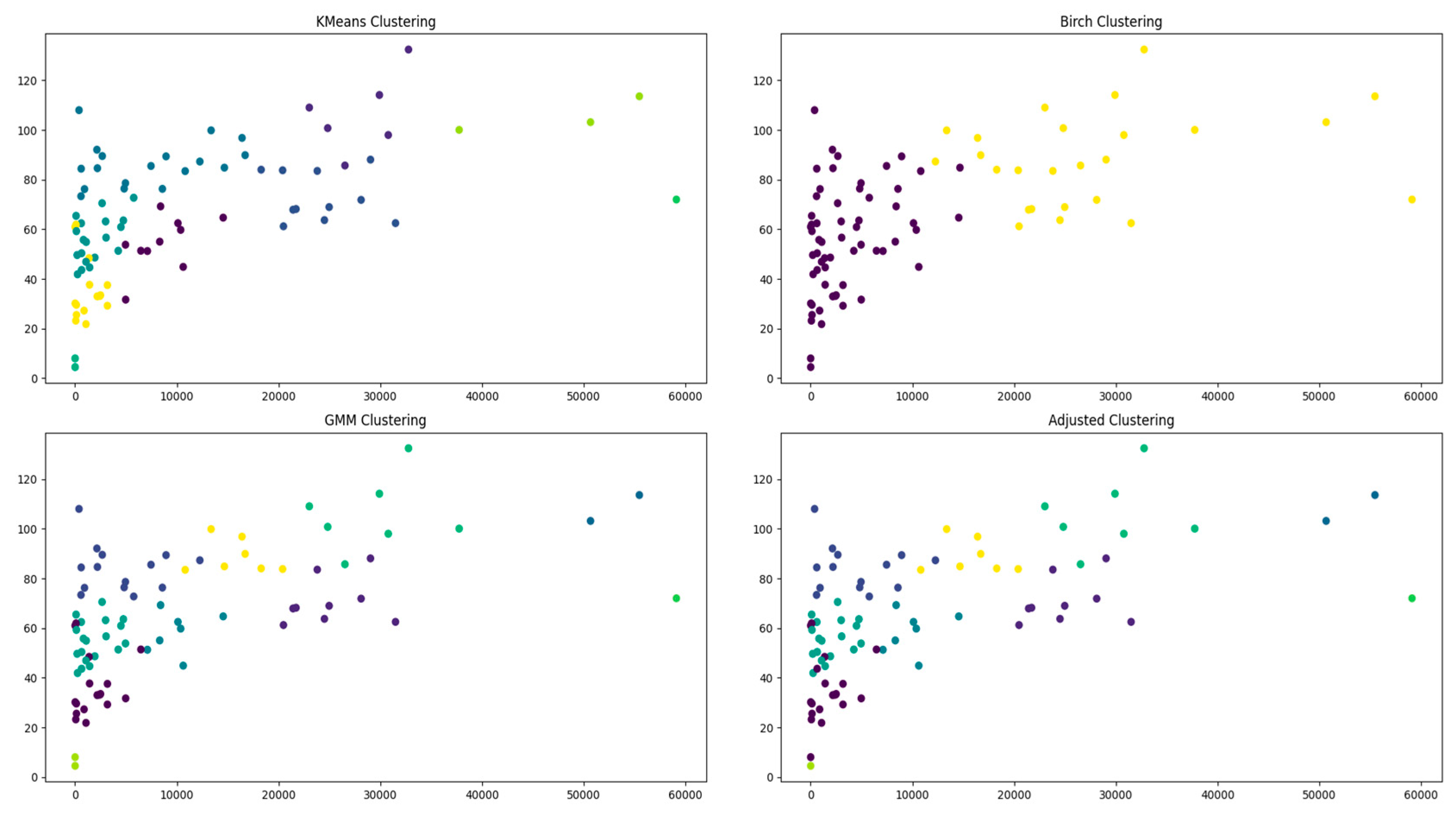

This section introduces the computational experiments conducted to evaluate the proposed game pricing. The experiments are divided into two main scenarios: the mathematical models before and after the after clustering is applied. The program was run on a computer equipped with a 12th Gen Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-12400F processor at 2.50 GHz and 16 GB RAM, running the Windows 11 operating system, version 23H2. The system is a 64-bit operating system based on an x64 processor. All carrier containers staying in the port data comes from real data of a port along the southeast coast of China.

5.2. Simulation of Parameters in the CY

Next, we will focus on the perspective of CY and conduct simulation based on the parameters of container free storage period and CY pricing strategy for before the clustering model. RCTY and carriers will optimize using genetic algorithms, adaptive genetic algorithms, etc. In this case, the crossover rate for genetic algorithms is set to 0.8, and the mutation rate is set to 0.2. The adaptive genetic algorithm will adjust the crossover rate and mutation rate based on the iterative process. In the initial stage of the algorithm, a higher crossover rate and mutation rate are used to explore the search space and introduce diversity to prevent the population from falling into local optimal solutions. In the later stages of the algorithm, a lower crossover rate and mutation rate are used to refine the search, ensuring convergence to the global optimal solution and avoiding excessive random disturbances.

5.2.1. Before the Clustering

This section presents the impact of pricing strategy scope and free stacking period on the objective functions of port yard revenue before hierarchical pricing, revenue from distant external yards, and carrier costs. It is expected to draw some conclusions on the pricing strategy setting for port yards in terms of port operation pricing strategy. There are nine main scenarios in which the sensitivity of pricing strategies changes.

Apart from the different value ranges, the logic of the values is the same as previously described.

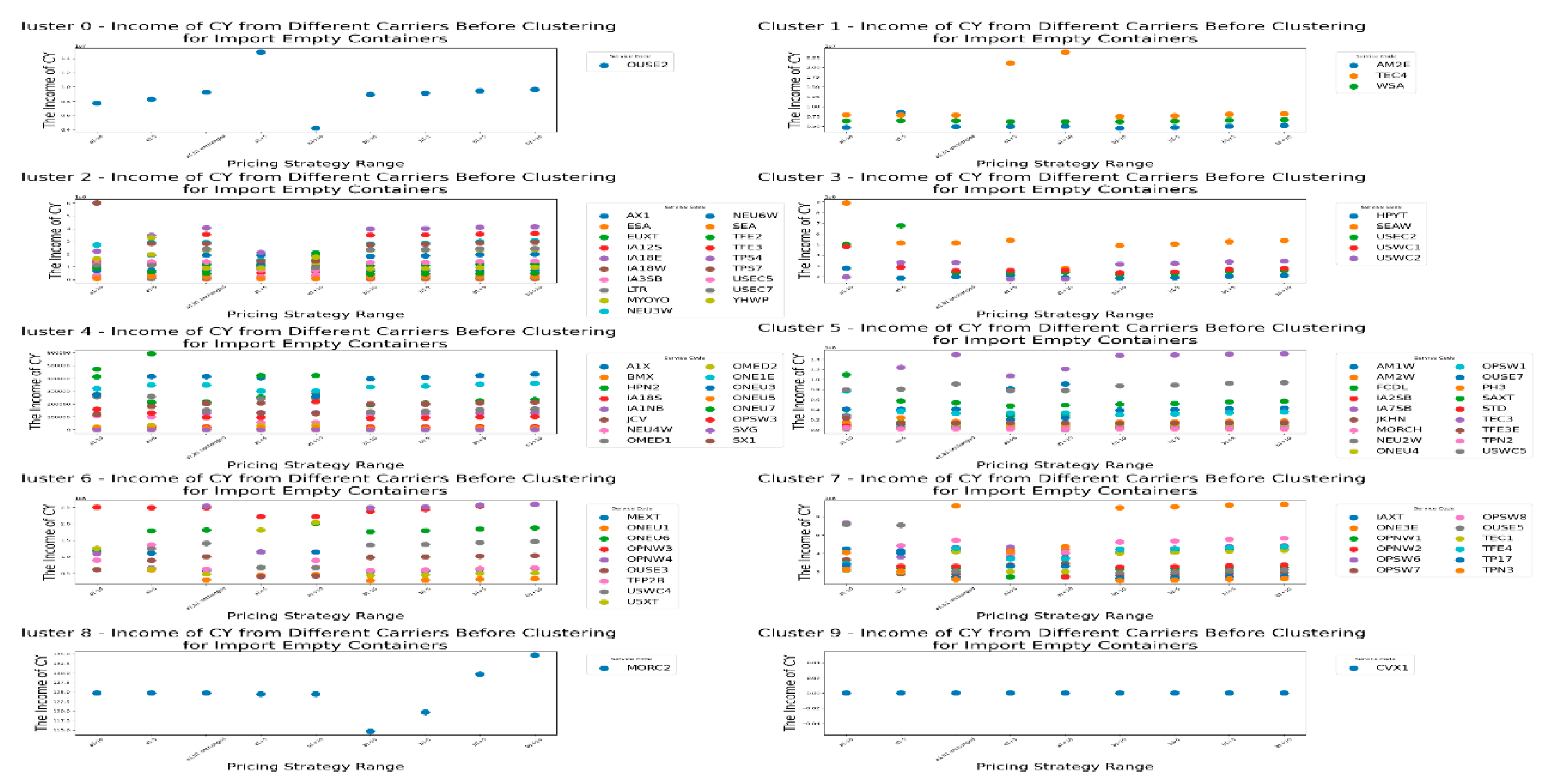

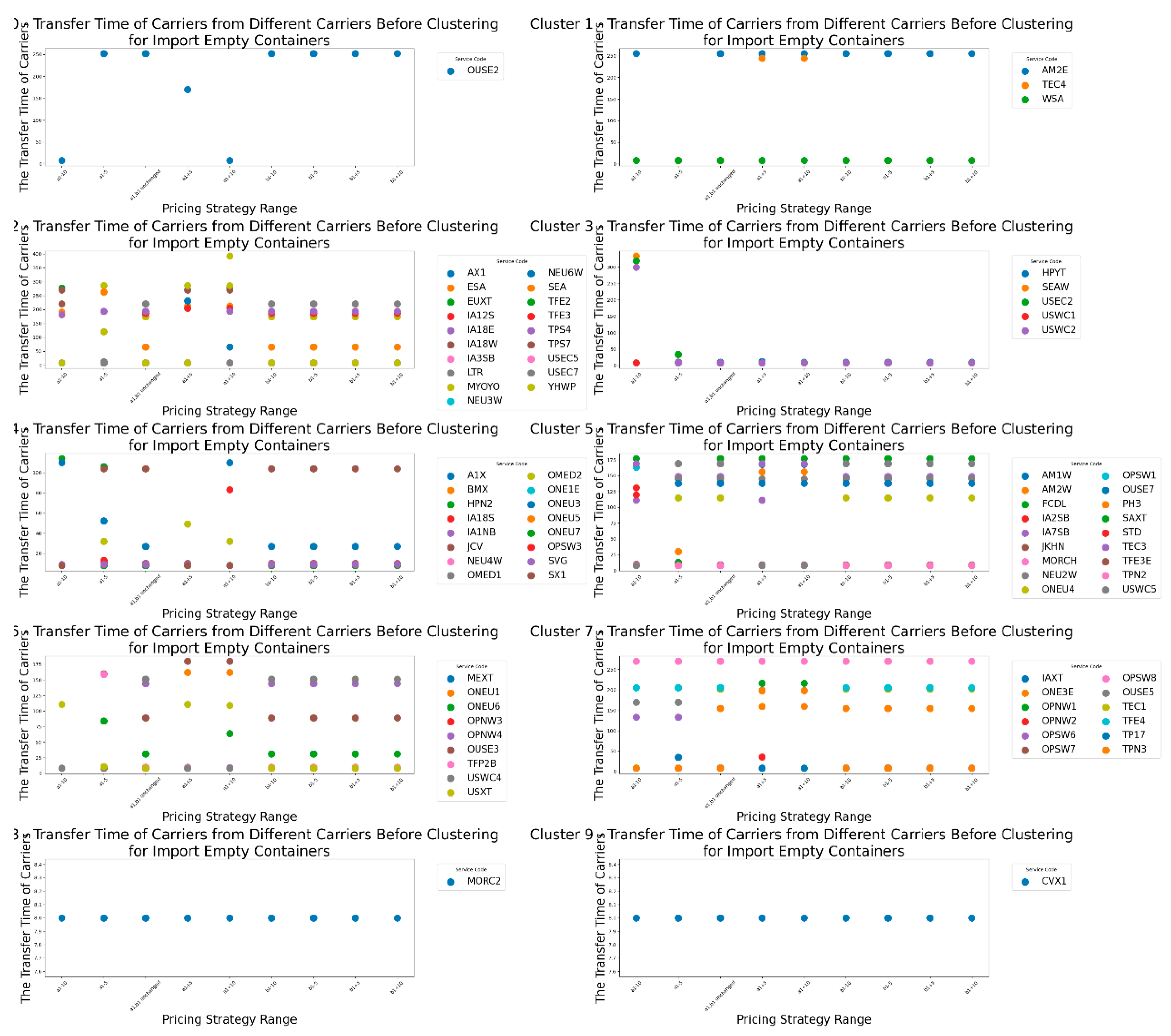

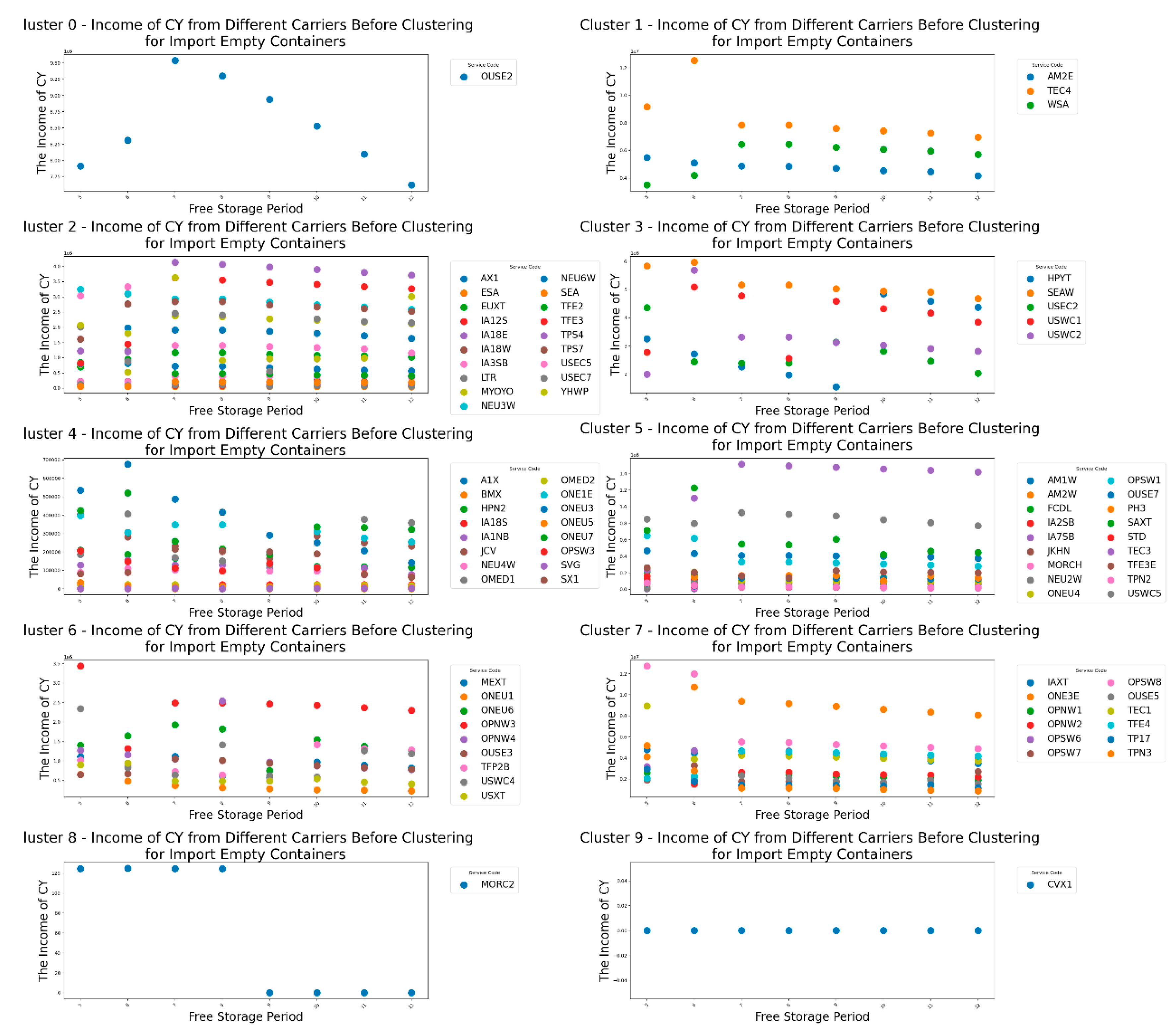

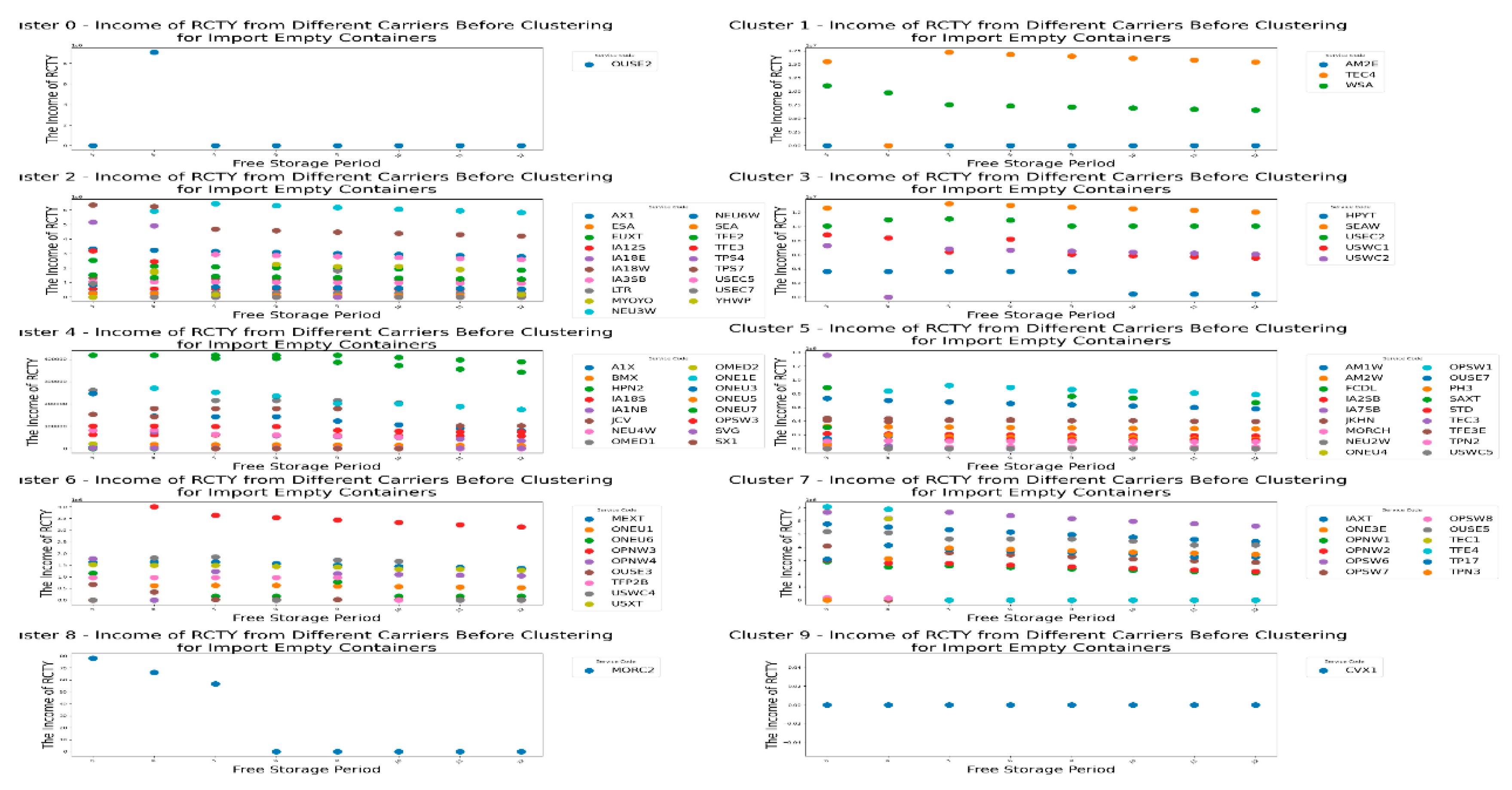

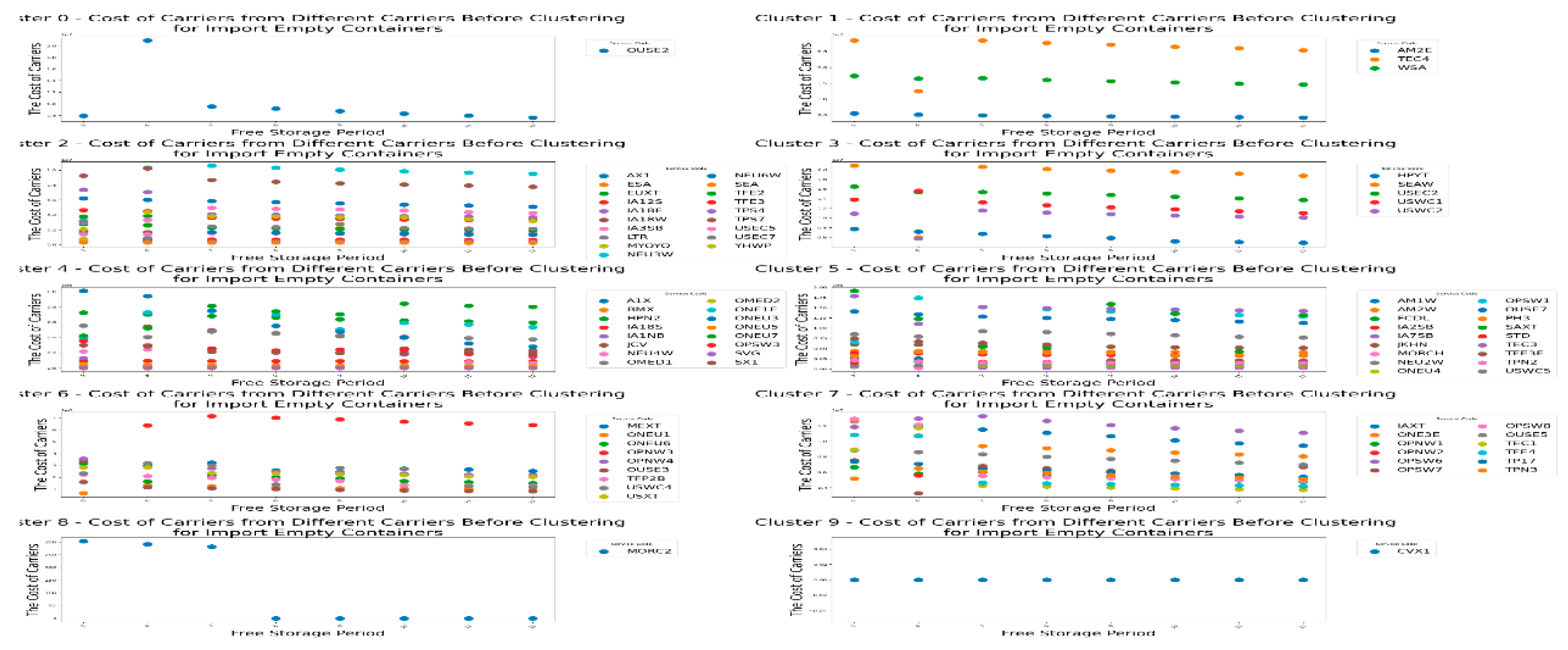

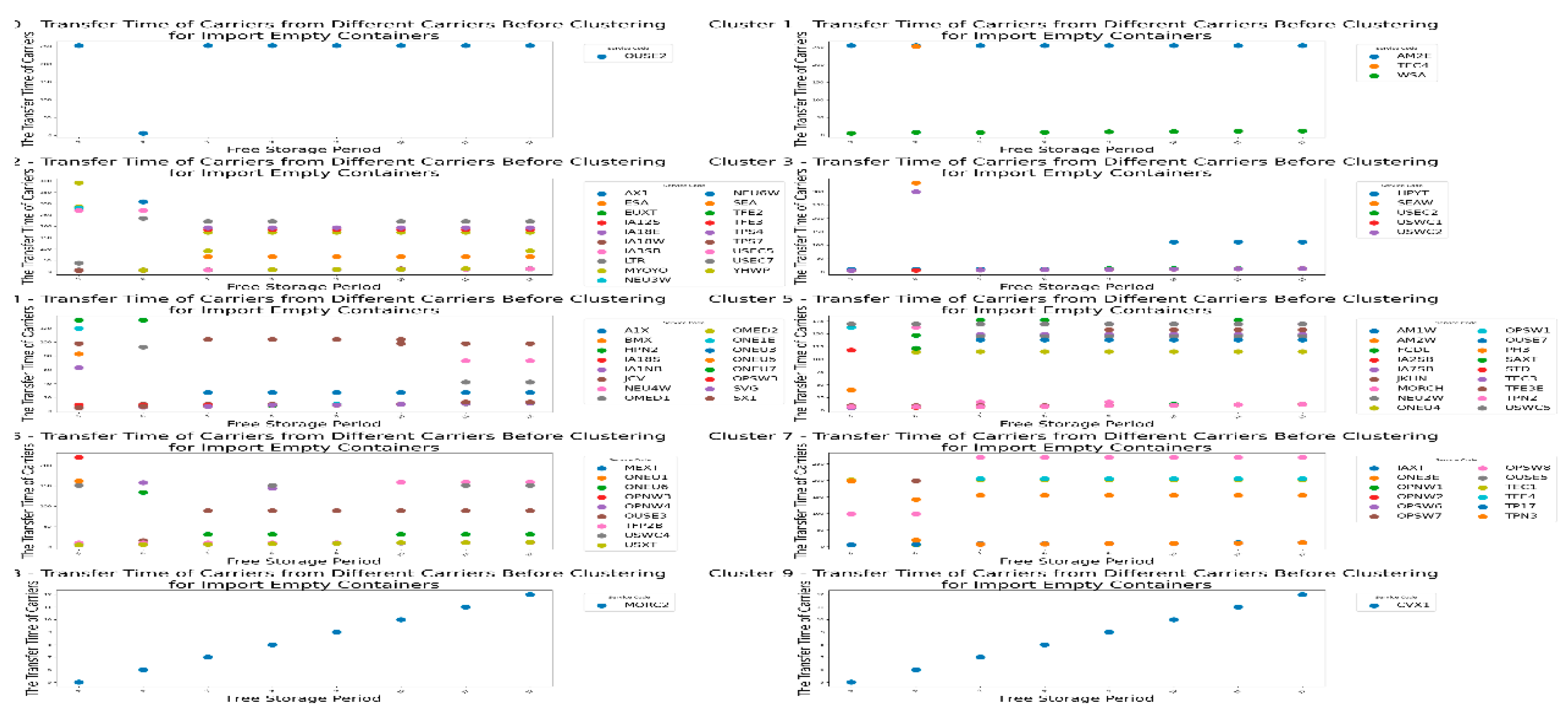

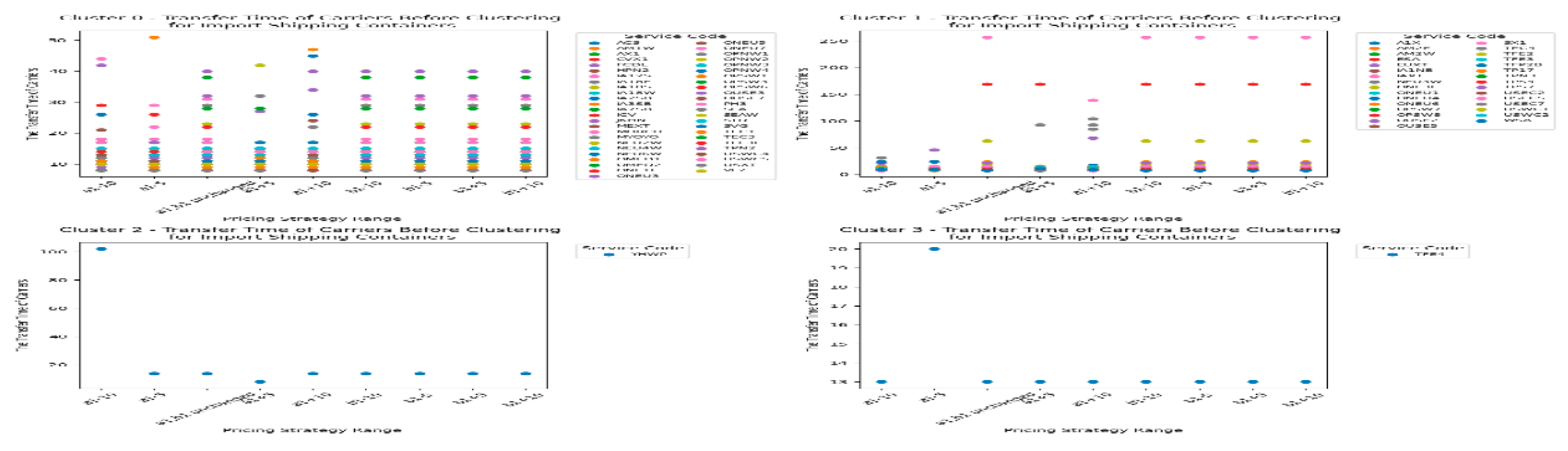

First, we start with the import empty containers before clustering and observe the changes in the income of the CY, the income of the RCTY , the carrier’s storage costs, and the transfer time of each carrier as the carrier pricing strategy range varies before clustering. The following images display the data for each cluster, showing the carriers included in each cluster, as shown in

Figure 7.

From

Figure 7, we can see that before clustering the carriers, the changes in CY’s income under different pricing strategy ranges vary for different carriers. For most carriers, adjusting the pricing strategy range shows that changes in the

pricing strategy range have a greater impact on CY’s income than changes in the

pricing strategy range, especially for carriers like OUSE2 and TEC4. This indicates that before clustering, CY should consider the impact of variable costs in storage fees on its own income when setting pricing for similar carriers.

However, there are also cases where changes in the a1 pricing strategy range have less impact on CY’s income than changes in the b1 pricing strategy range, such as with the carrier MORC2. This suggests that such carriers are more affected by changes in fixed costs. Therefore, when adjusting the pricing strategy range before clustering, CY can consider increasing fixed storage costs to boost its storage income to some extent.

Additionally, there are cases where CY’s income from carriers is not affected by the pricing strategy range, such as with carrier CVX1. This may be because all containers of this carrier fall within the free storage period set by CY. If CY wants to increase its income, it could consider shortening the free storage period.

From this, we can draw

Result 1: If CY wants to increase its storage income before clustering, it should optimize the pricing strategy range based on the characteristics of different carriers' pricing strategies to maximize income. It can also be observed that without pre-clustering the carriers, this process may be relatively complex.

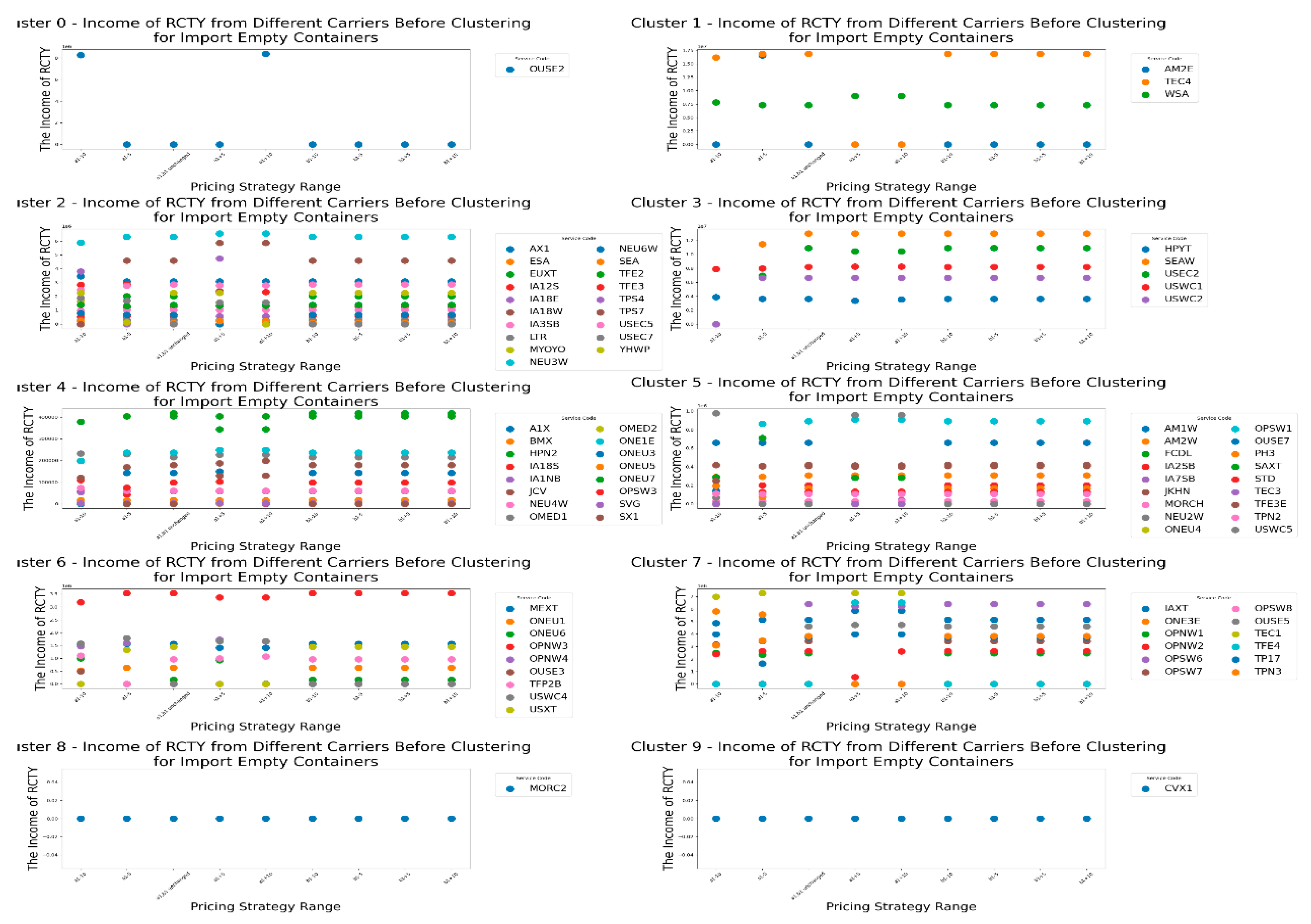

Let's first look at the changes in the RCTY’s income under different pricing strategies for import empty containers before clustering, as shown in

Figure 8.

From

Figure 8, we can see that due to the free storage period setting, most carriers choose to transfer containers from CY to RCTY, allowing RCTY to also gain storage income. For carriers like EUXT, when CY adjusts the pricing range for

, the impact on RCTY's income is actually smaller than the impact of adjusting the b

1 range. However, for most carriers, adjusting the a

1 range in CY has a greater impact on RCTY's income than adjusting the

range. There are also cases where no matter how CY adjusts the pricing strategy range, RCTY's income remains unaffected. This can be due to two reasons: one is that the carrier's container stays in port for a shorter time than CY's free storage period; the other is that the carrier's storage cost at CY is less than or equal to its transfer cost plus storage cost at RCTY. In summary, this means that the costs incurred by carriers for storing containers at CY are within their acceptable range. Based on this analysis, we can draw result 2 for CY.

Result 2: The impact of adjusting the pricing strategy range on RCTY's income should be considered in relation to specific carriers. This situation, which takes into account RCTY's income, is more complex and can be seen as an extension of result 1.

Specifically, for carriers like EUXT, CY operators can increase their income by adjusting the range of the pricing strategy without significantly affecting RCTY's income. This facilitates reaching more acceptable agreements with RCTY. On the other hand, when forming an alliance with RCTY, CY operators can use this strategy adjustment to strengthen their cooperation with RCTY, achieving a win-win situation for both parties. In forming an alliance with RCTY, focusing on adjusting thepricing strategy allows CY operators not only to increase their own income but also to minimize the negative impact on RCTY's income. This approach helps CY operators to establish a more stable and cooperative alliance with RCTY, creating more favorable conditions for long-term development. For carriers like MORC2, CY operators can adjust thepricing strategy range to increase its income, but attention should be paid to the critical point to avoid charging too high a fee, which could lead to early transfers by the carrier.

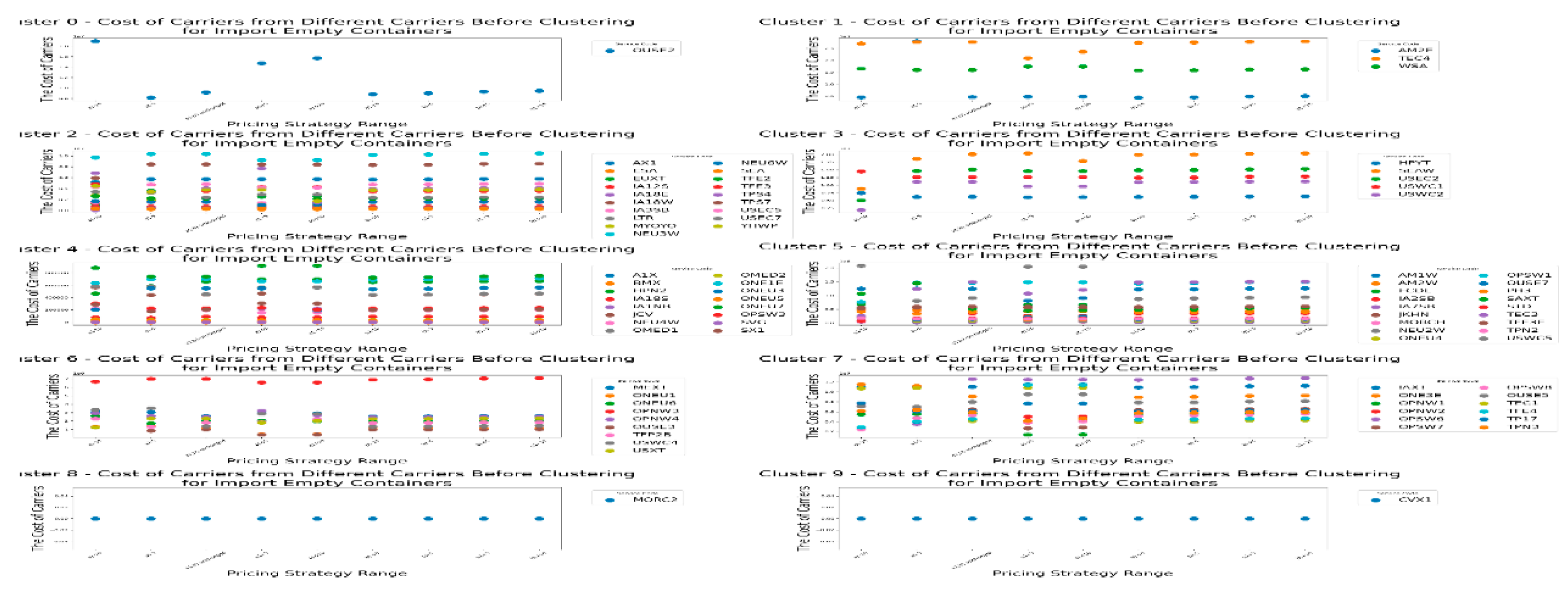

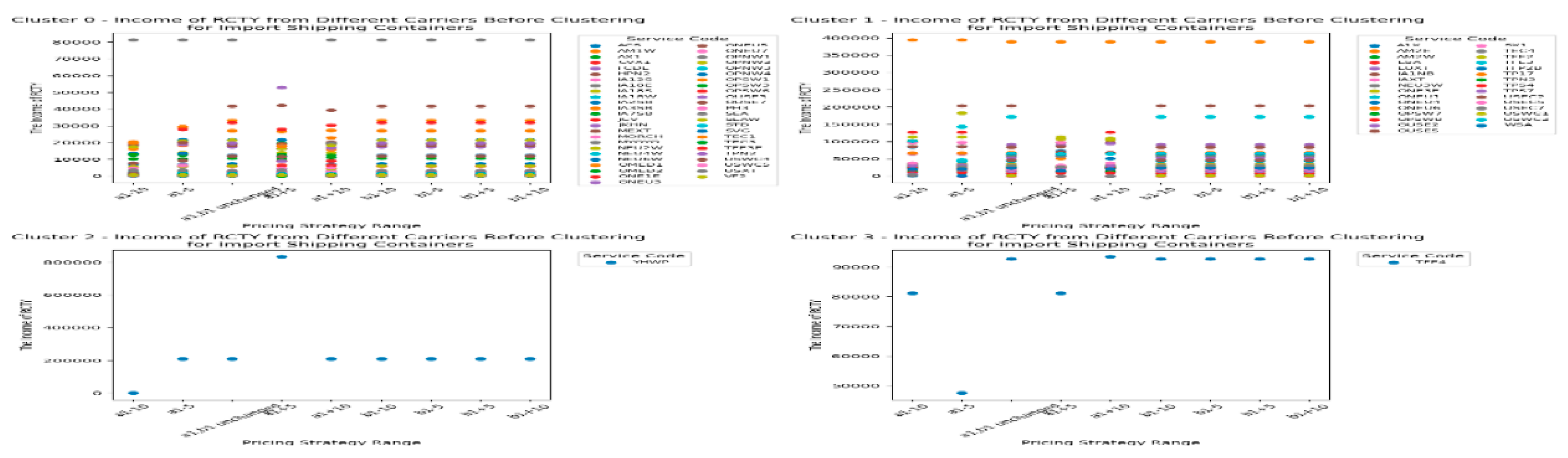

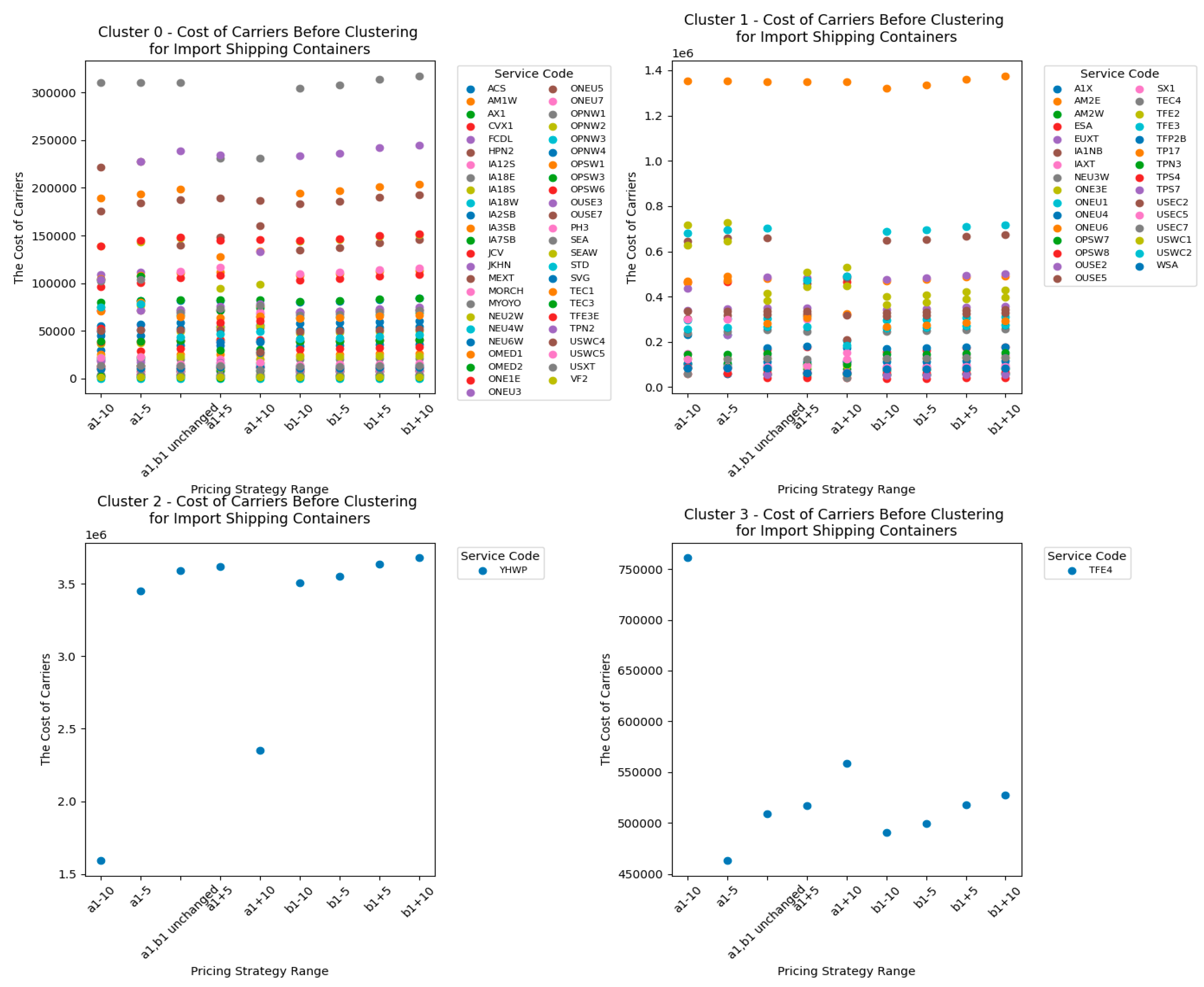

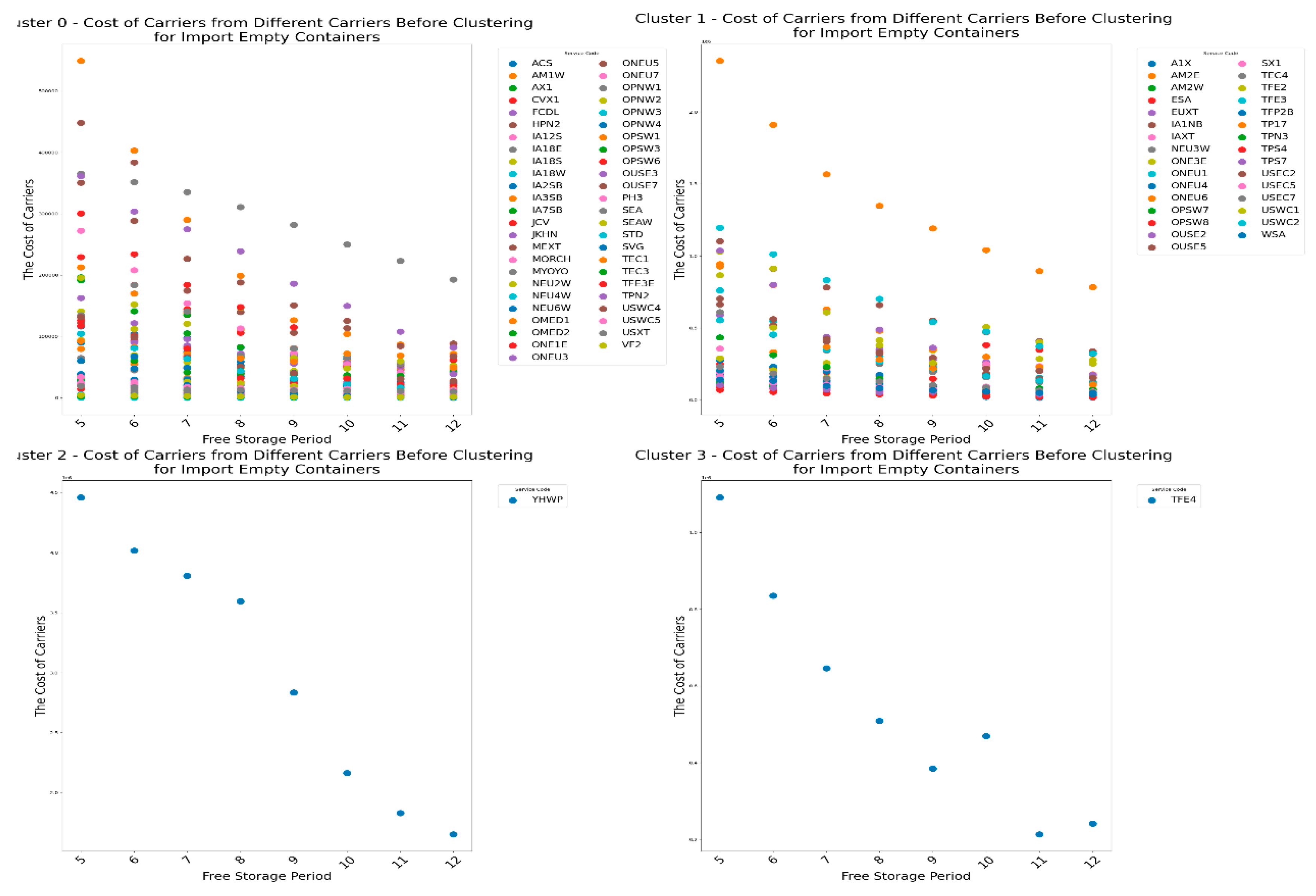

Next, let's first look at the changes in the carrier's costs under CY’s different pricing strategies for import empty containers before clustering, as shown in

Figure 9.

From the figure 9, We can observe that the carrier costs are significantly affected by the pricing strategy range set by the CY. This indicates that most carriers are highly sensitive to the variable costs of container dwell time at the port. This is likely because the variable cost is the per-unit-time storage cost for a container at the CY, which increases substantially with the number of containers and the length of time the containers stay at the CY. As a result, this variable cost plays a large proportion in the carrier's overall cost calculation. It can be concluded the result 3

Result 3: For most carriers, the impact of the pricing strategy range change ofon carrier costs is smaller than the impact of the pricing strategy range change offor imported empty containers.

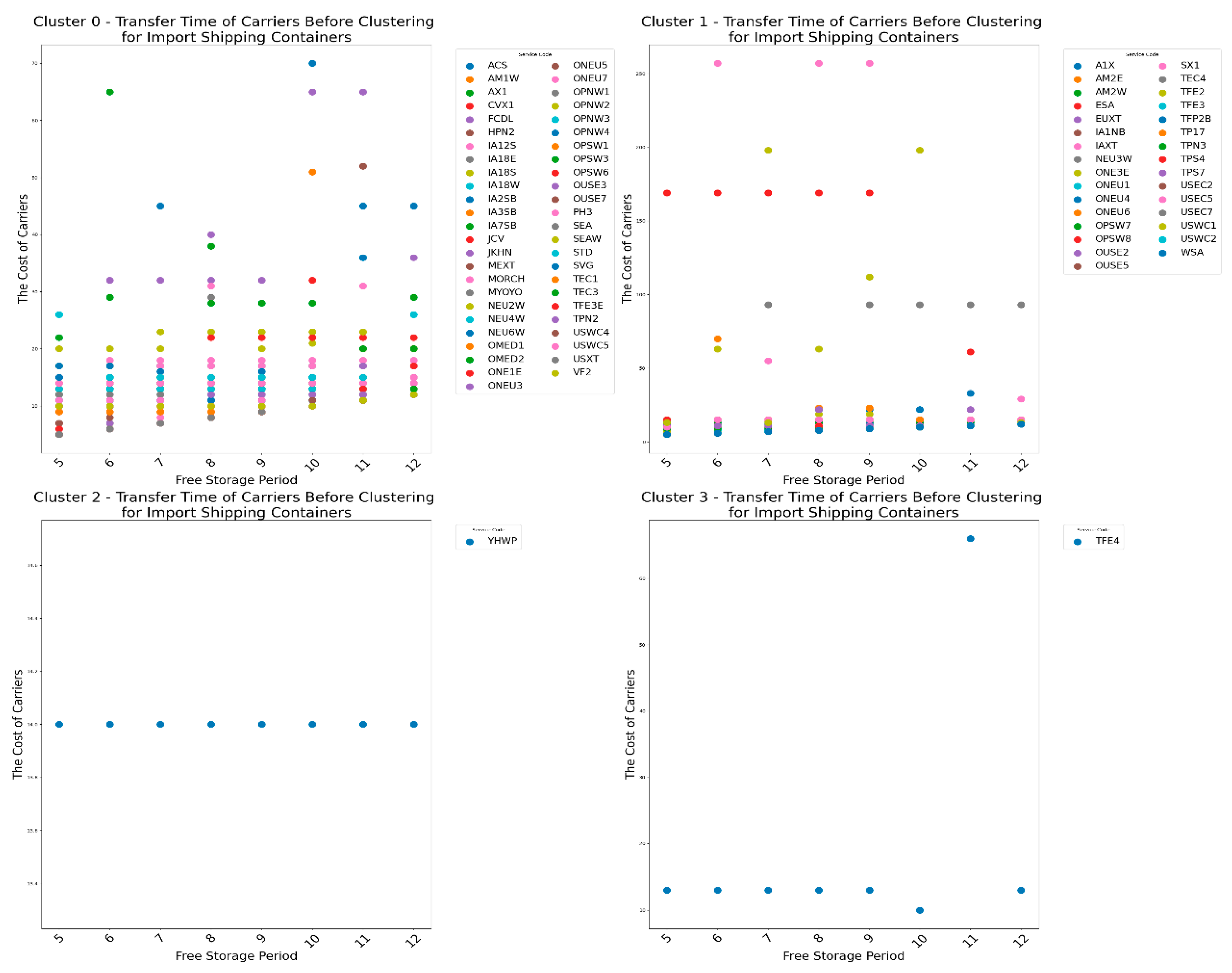

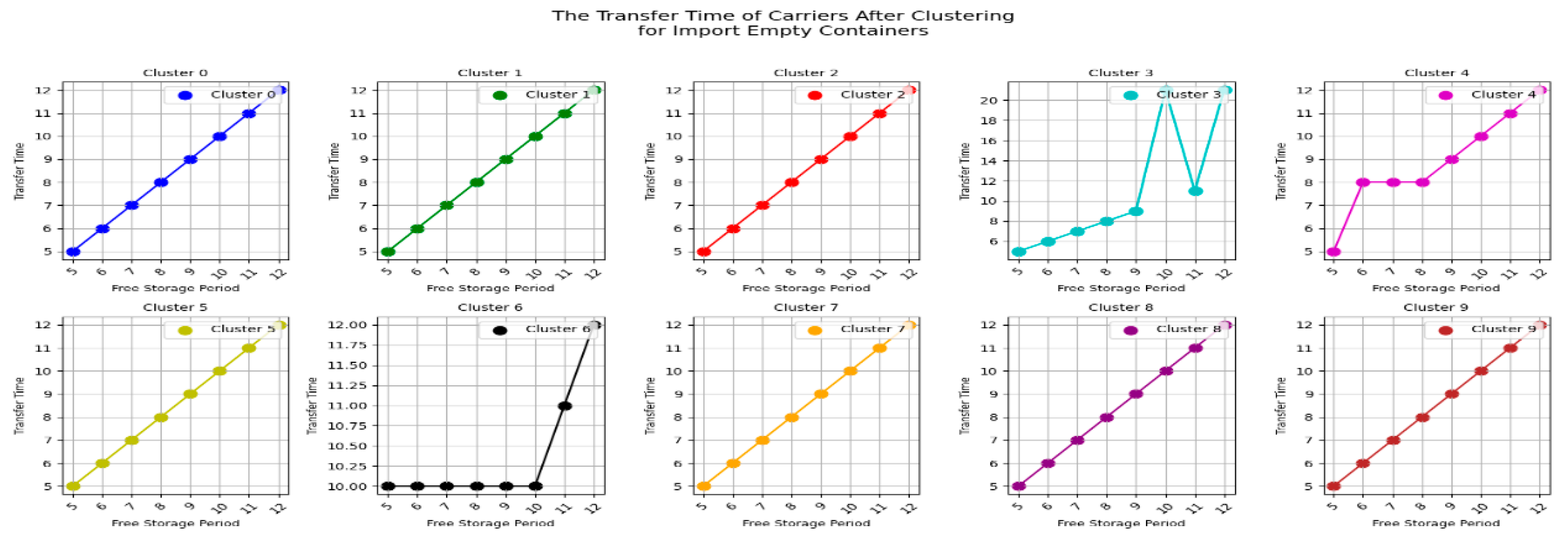

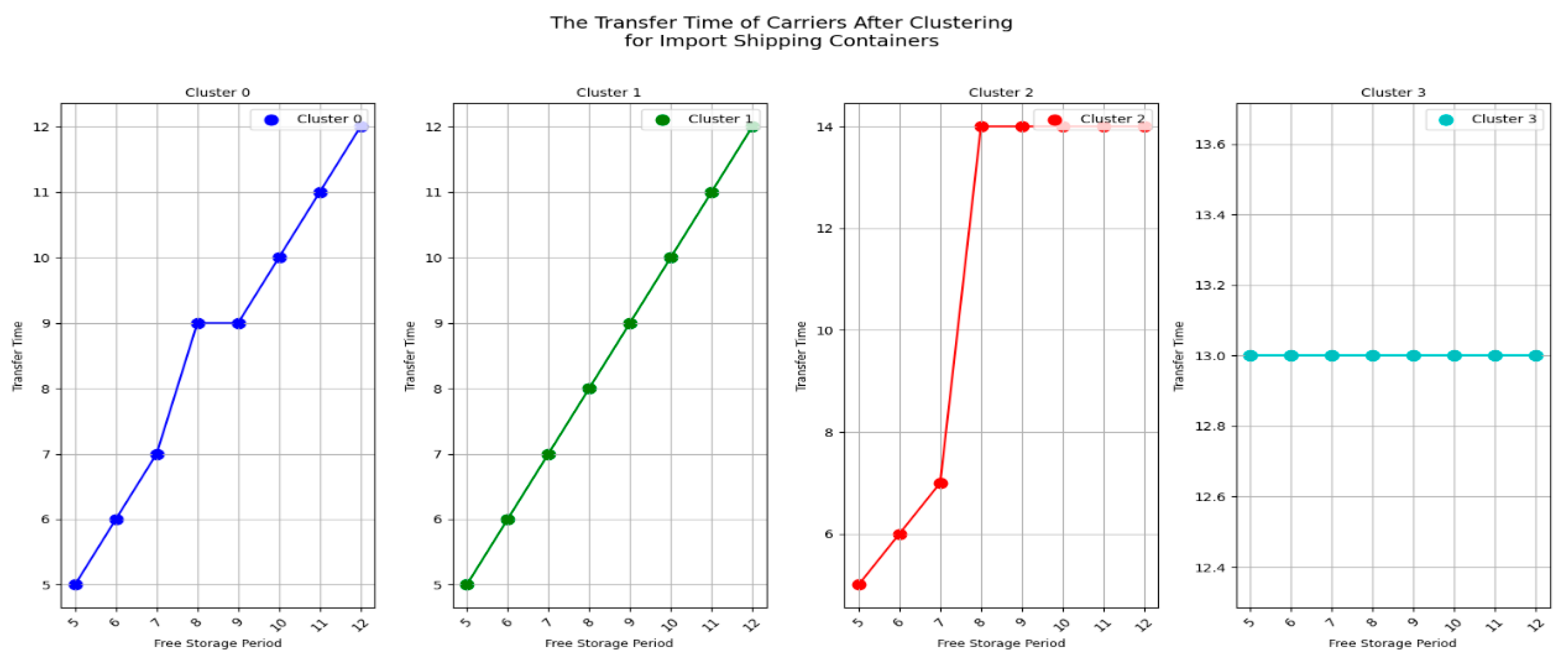

Next, let's first look at the changes of the carrier's transfer time under CY’s different pricing strategies for import empty containers before clustering, as shown in

Figure 10.

From

Figure 10, we can see that the transfer time of most carriers is not affected by the CY pricing strategy range. However, there are also carriers whose transfer time is significantly influenced by the

pricing strategy range. It can be concluded the result 4

Result 4: For most carriers, the pricing strategy range variation for importing empty containers does not affect the transfer time of carriers.

Therefore, CY operators should prioritize adjusting the a1 pricing strategy to increase their own revenue while reducing carrier costs. This adjustment not only helps enhance CY's profitability but also reduces the financial burden on carriers, thereby improving the cooperation with them. Simultaneously, pay attention to the impact of a1 pricing strategy on a portion of carrier transfer time, to consider the sensitivity of different carriers to pricing strategy changes, and to avoid excessive adjustments to the a1 pricing strategy that could lead to instability in carrier transfer times, thus impacting overall operational efficiency. When adjusting the a1 pricing strategy, CY operators need to balance reducing carrier costs with maintaining stable transfer time. Proper adjustment of the a1 strategy can increase income while ensuring stable transfer time for carriers, which helps in fostering long-term cooperation with them.

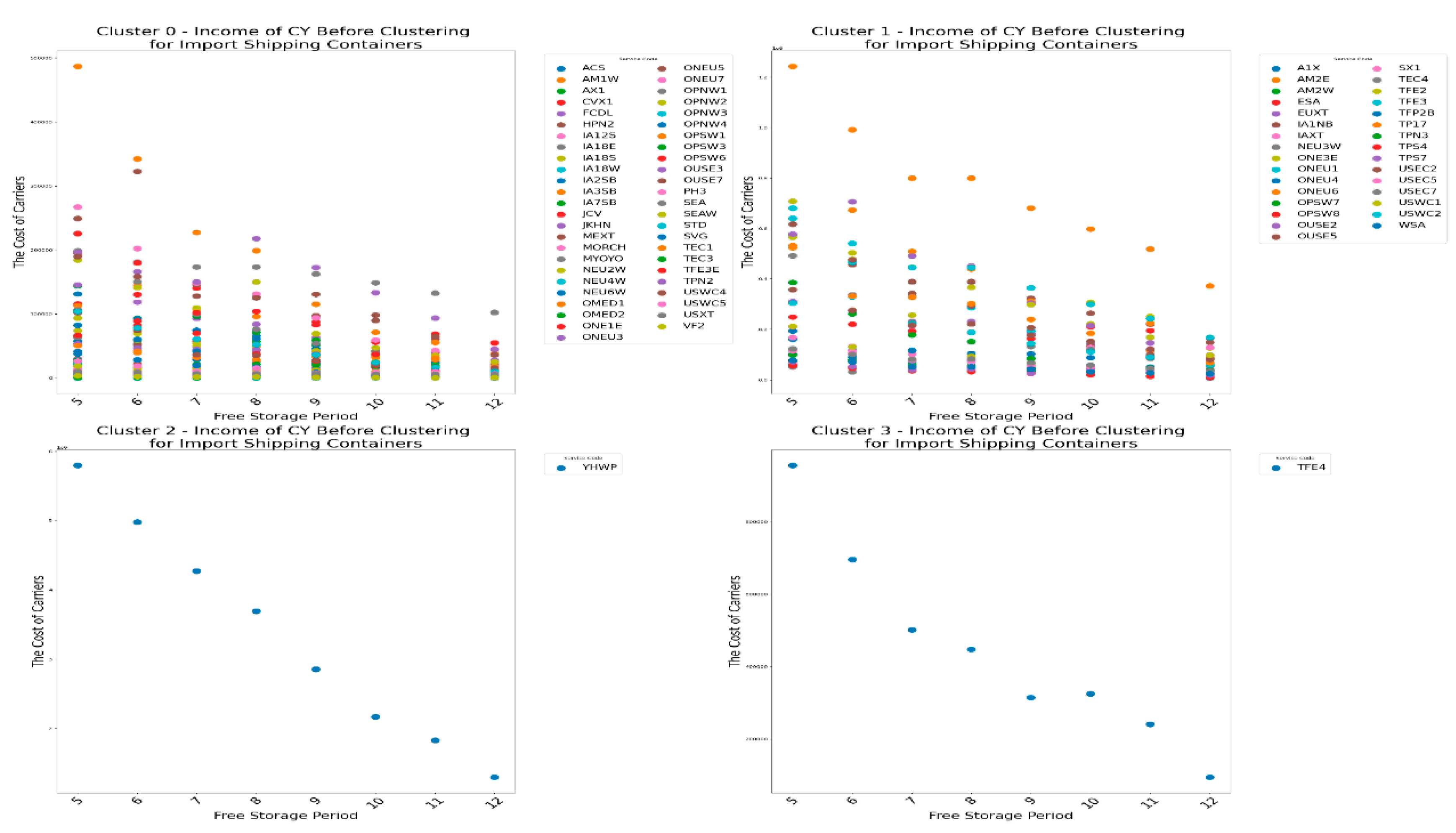

Next, let's take a look at the impact of changes in the free storage period on a range of participants for empty container. Firstly, take a look at the impact of the free storage period change on CY's income .

From

Figure 11, we can observe that for most carriers, the CY Income gradually decreases as the free storage period increases, such as in the case of AM2E. However, there are also carriers whose CY Income peaks at a certain free storage period and then declines, such as OUSE2. In addition, some carriers, such as CVX1, show no change in CY Income regardless of the free storage period.

Result 5: Overall, the CY Income exhibits different trends of change with the free storage period due to the specific characteristics of different carriers, necessitating a detailed analysis.

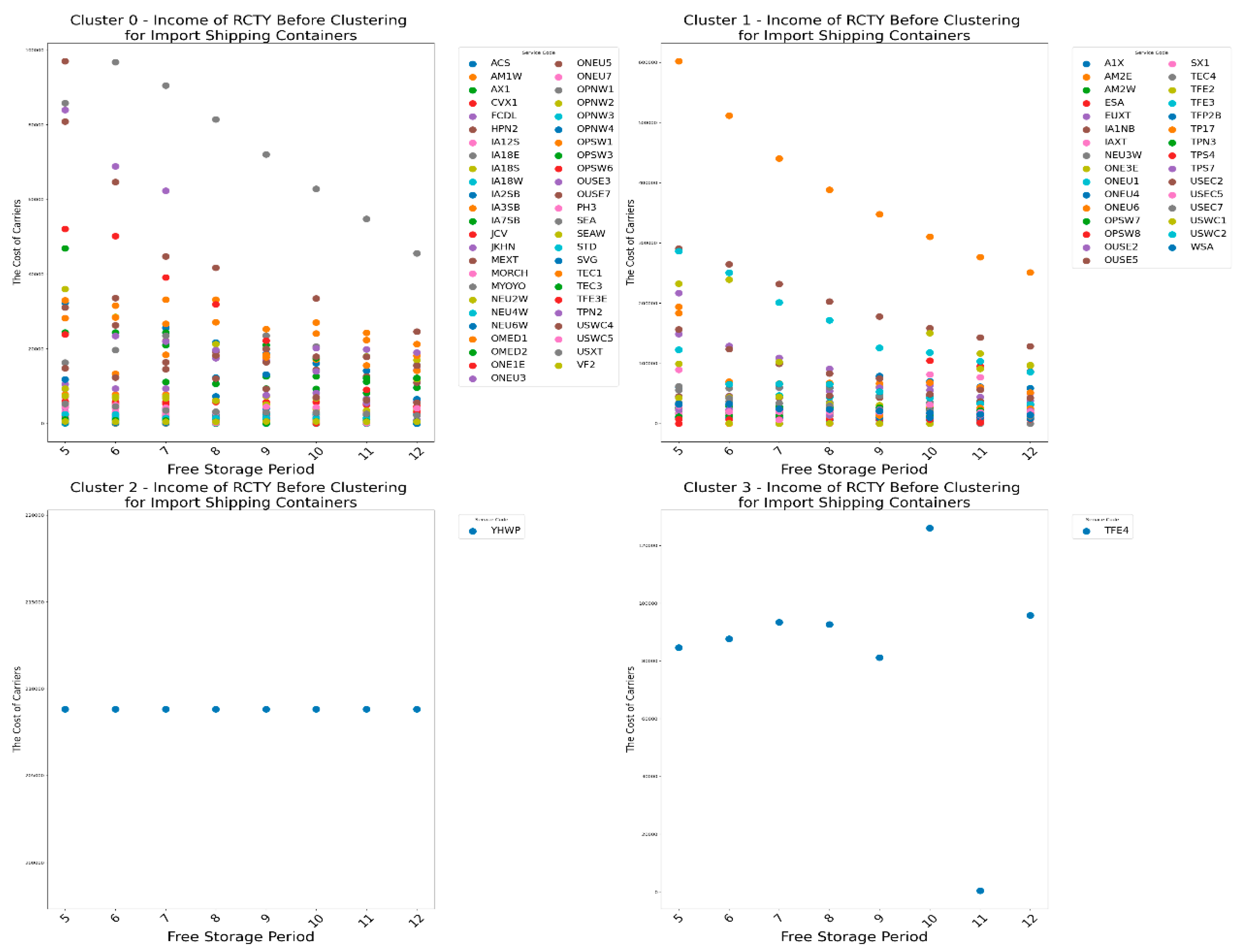

Let's take a look at the impact of the free storage period change on RCTY's income for import empty containers, as shown in

Figure 12.

From

Figure 12, we can see that most RCTY's income decreases with the increase in the free storage period set by CY. This is because, as CY extends the free storage period, more carriers opt to store containers in port storage yards, leading to a simultaneous decline in both CY’s income and RCTY’s income.

Result 6: For import empty containers, the RCTY’s income decrease with the increase of the free storage period set by CY.

Insights CY Operators when adjusting the free storage period, CY operators need to consider the acceptable range of income fluctuations and plan accordingly to avoid significant reductions in income due to these adjustments. In addition, if CY operators seek to form an alliance with RCTY and adjust the free storage period as part of the pricing strategy, they should consider compensating RCTY for any potential losses resulting from longer free storage periods. However, if the free storage period is relatively short, CY’s yards might still have sufficient space for other port operations, making it easier to manage available space effectively.

Next, let's take a look at the impact of free storage period on carrier’s costs and on carrier’s transfer time for import empty containers from

Figure 13 and

Figure 14.

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 are more intuitive compared to the previous ones, directly supporting Result 7:

Result 7: The costs for most carriers decrease as the free storage period set by CY increases, while their transfer times increase.

This aligns with intuition: when CY extends its free storage period, carriers are more inclined to store containers in port storage yards. This not only facilitates their operations but also reduces container storage costs. However, due to CY's storage space limitations, there may be situations where containers must be transferred, resulting in increased carrier costs despite the extended free storage period.

Insights for CY Operators ,extending the free storage period can reduce the carrier's costs, which is beneficial for improving the carrier's service experience, help carriers reduce costs, thereby enhancing their competitiveness and willingness to cooperate. However, extend the free storage period could lead to a decline in port operation efficiency, as longer storage time may occupy more yard space, affecting the overall port operations. CY operators need to find a balance between extending the free storage period and maintaining efficient port operations, ensuring that carrier service experience is improved without compromising overall port efficiency. Through refined management and strategic adjustments, CY operators can meet the needs of carriers while maintaining their own operational stability.

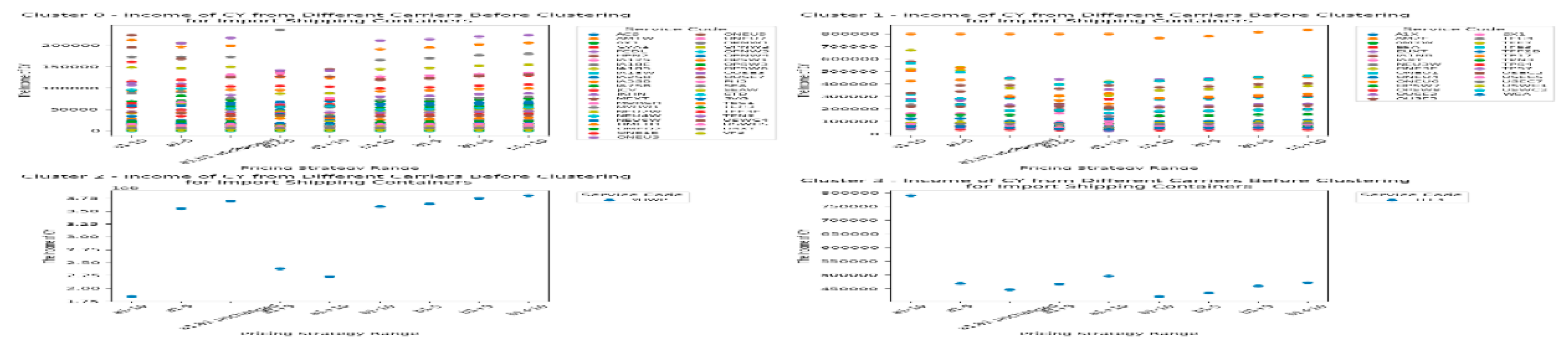

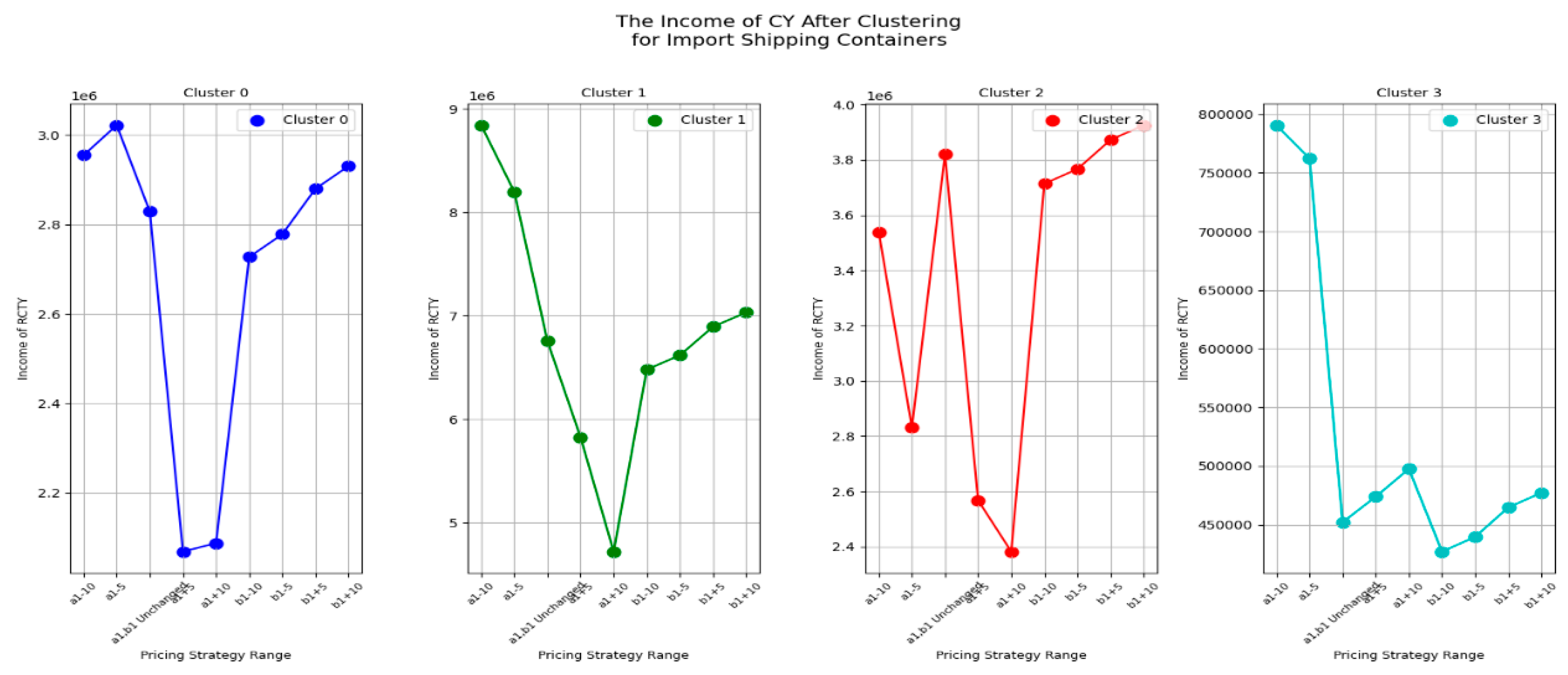

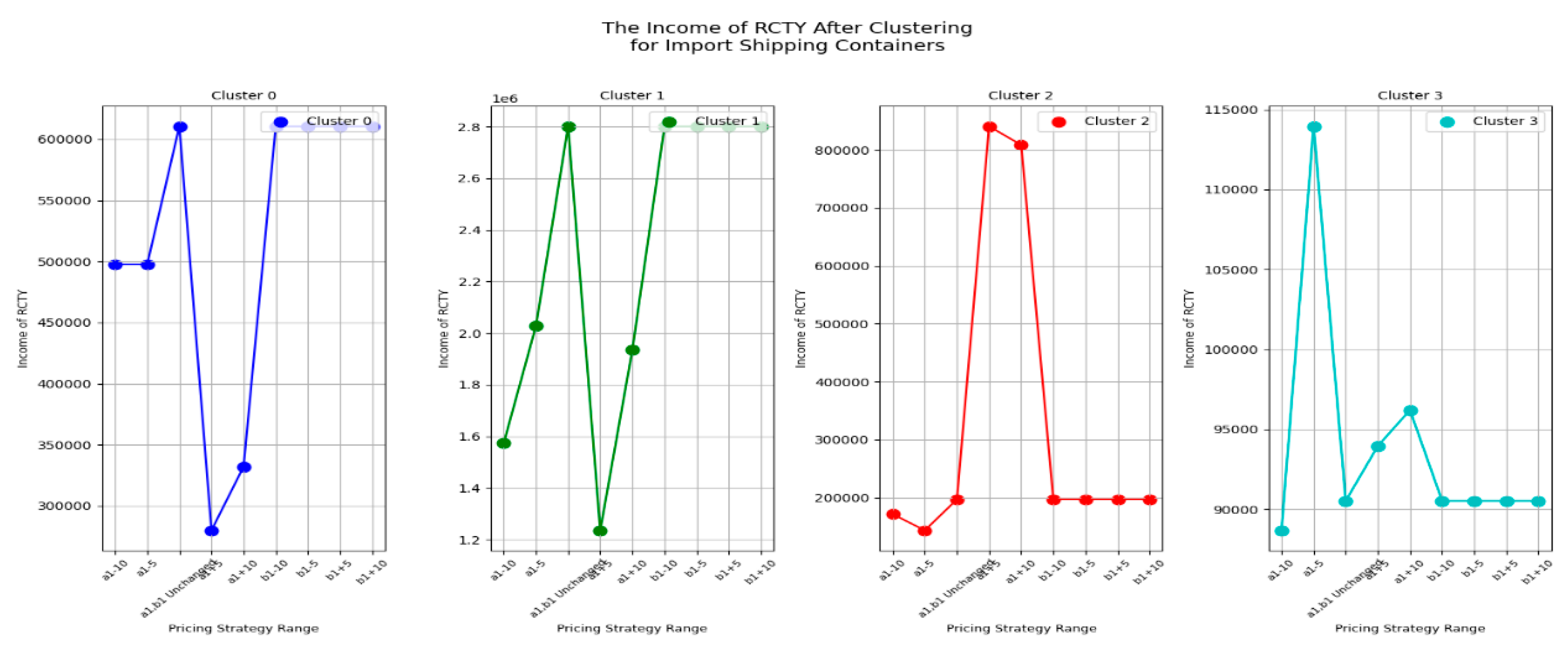

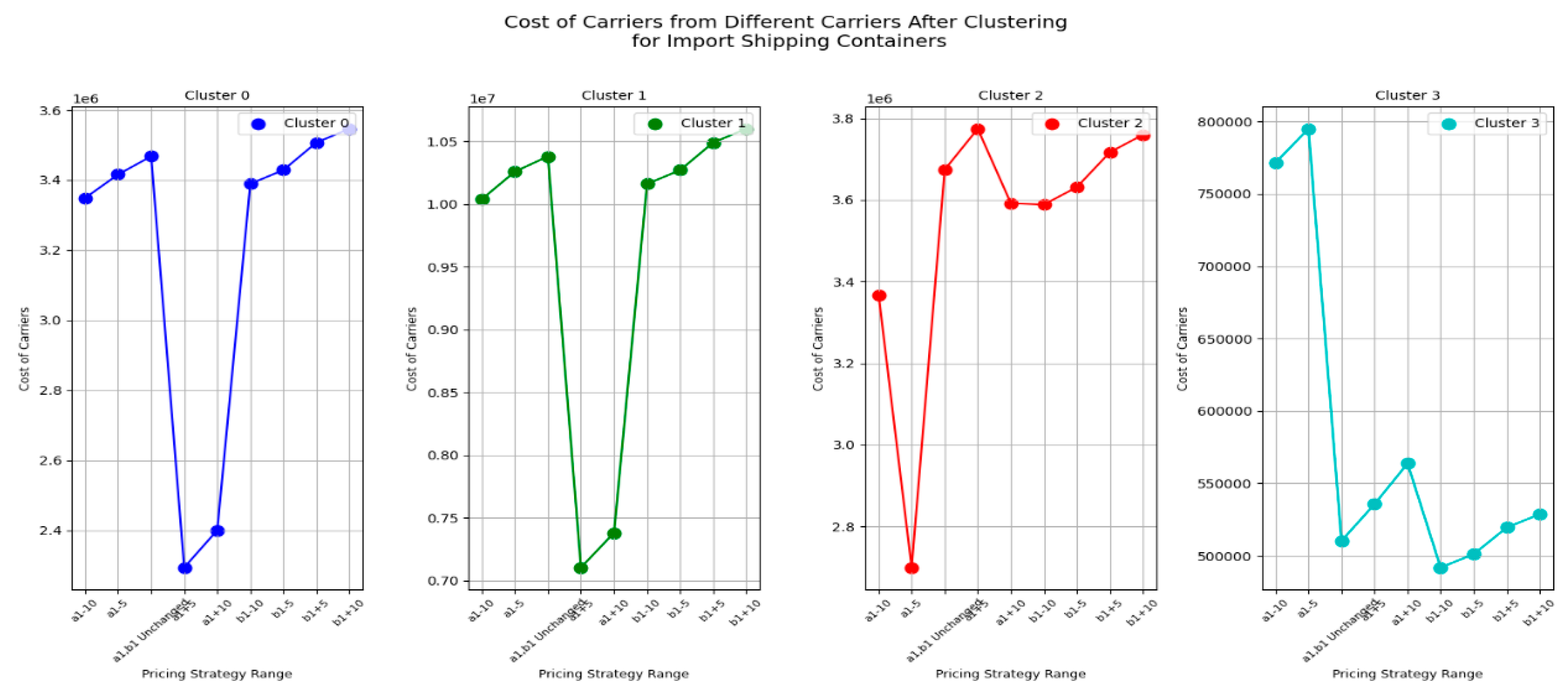

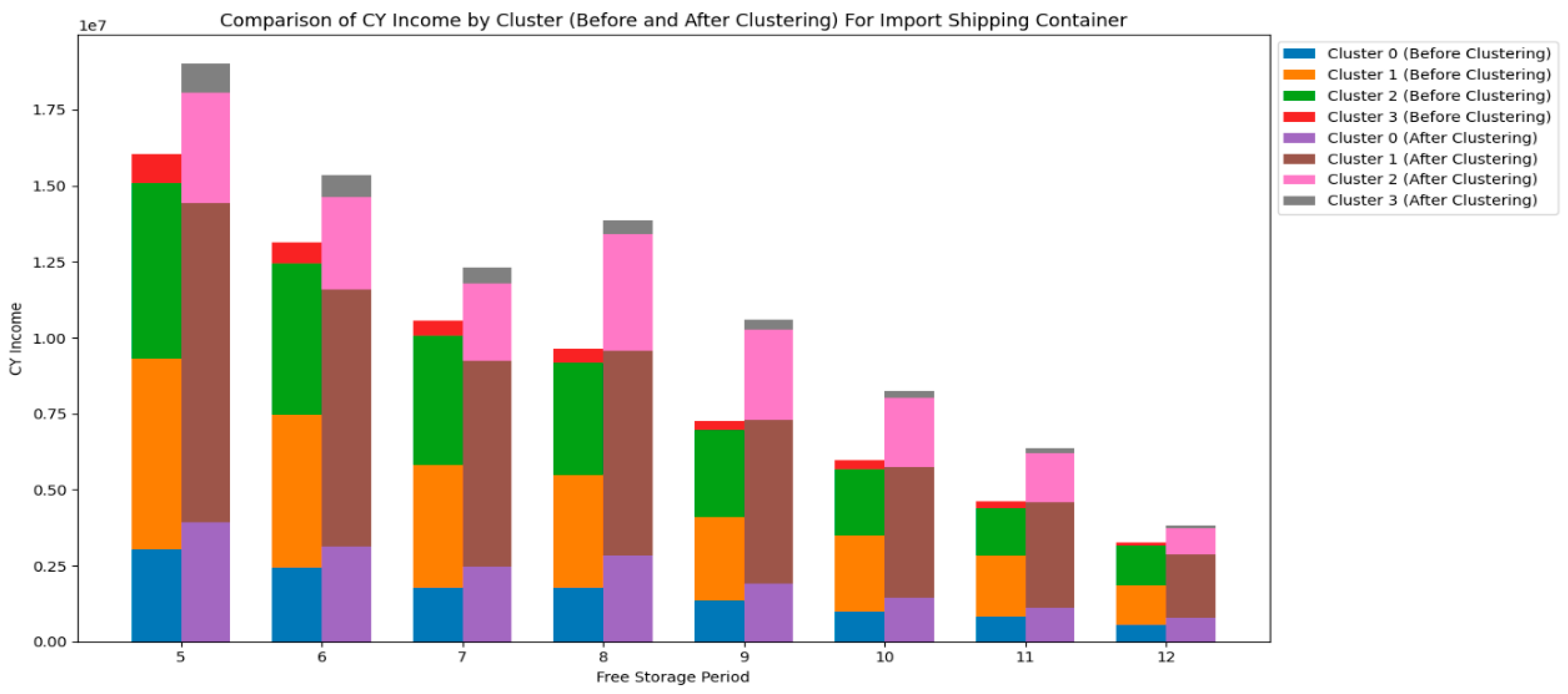

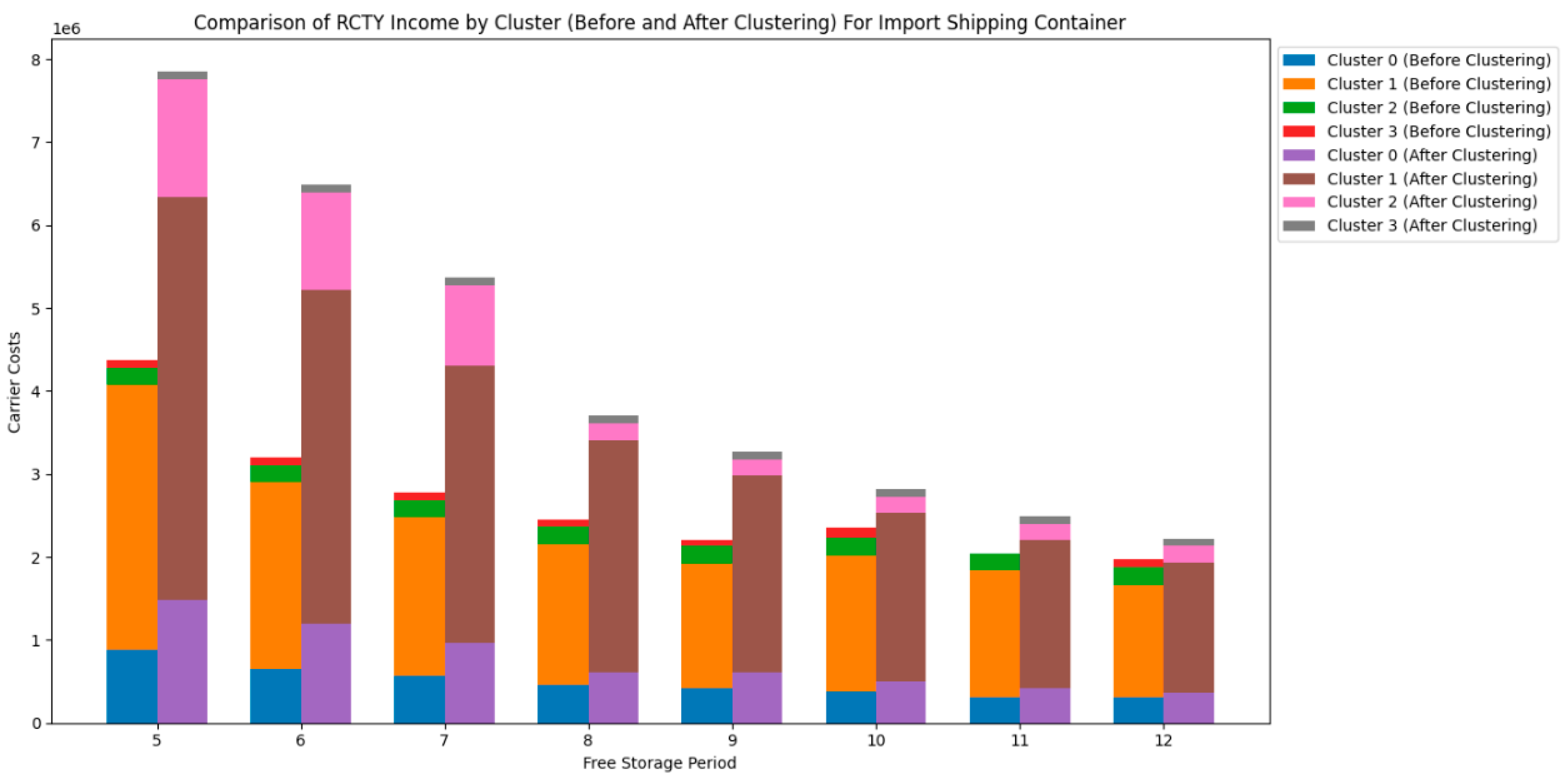

Next, let's take a look at the import shipping container.

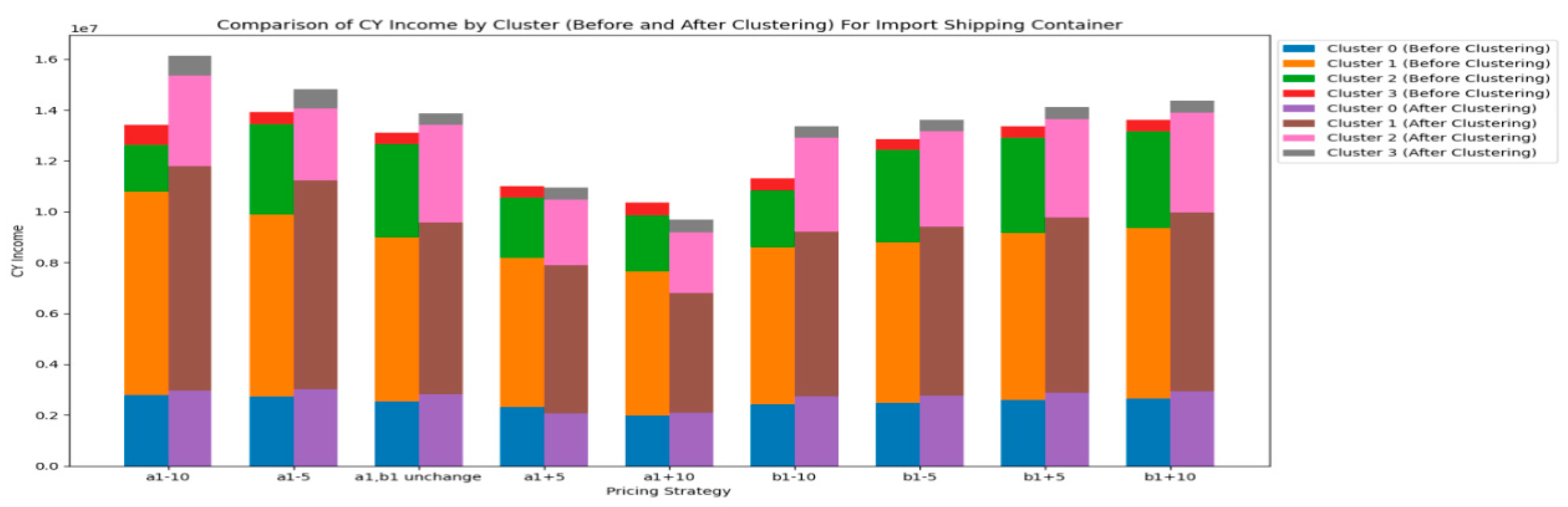

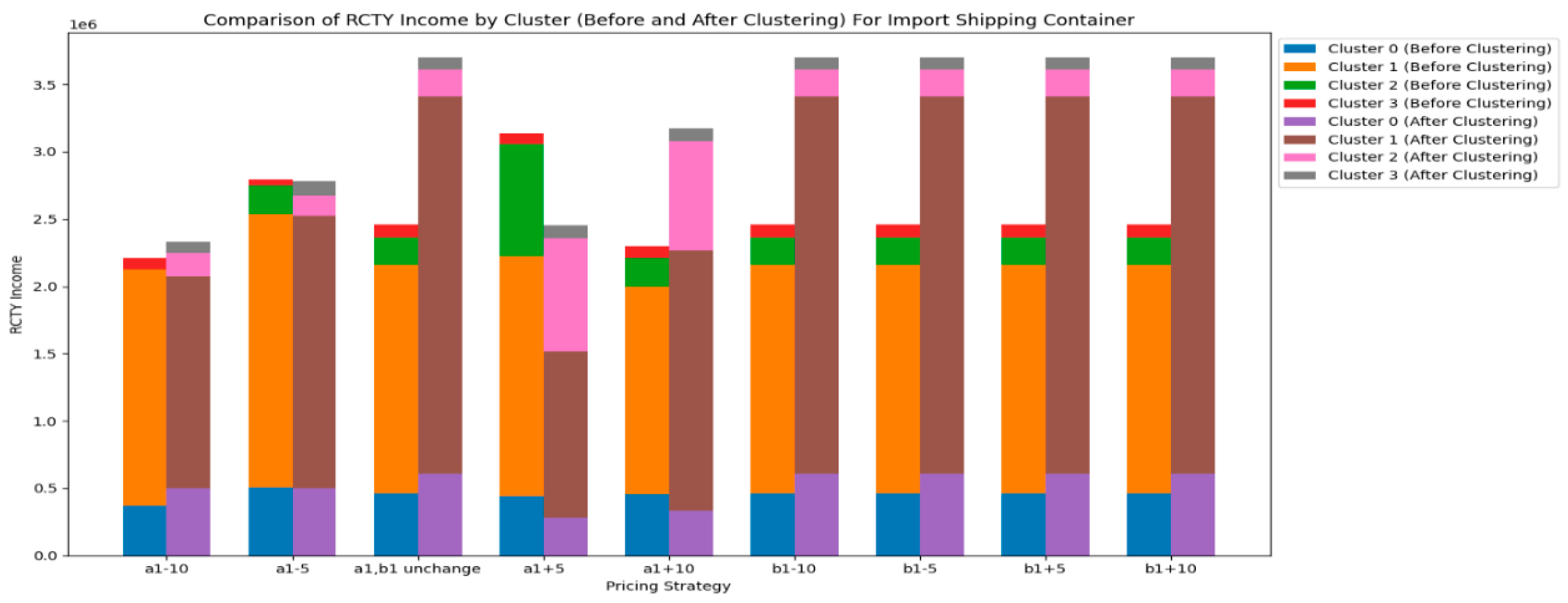

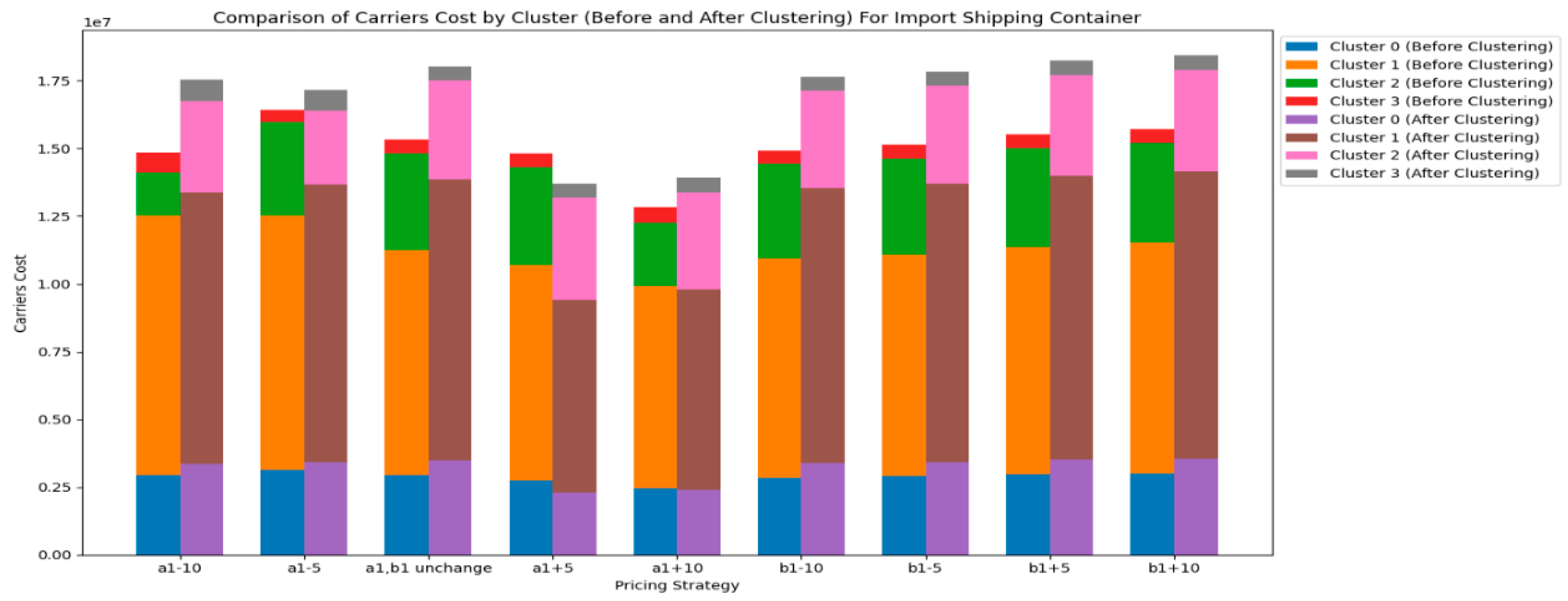

Figure 15Figure 16Figure 17 and

Figure 18 show the impact of changes in pricing strategy range on the income of CY, the income of RCTY, the costs of carriers, and the transfer time of carriers for import shipping containers.

From

Figure 15 and

Figure 16, we can observe that for import shipping containers, the impact of CY adjusting the pricing strategy range of

on its income and RCTY’s income are significantly greater than the impact of adjusting the pricing strategy range of

. Generally, the income CY obtains from most carriers increases as the range of

increases and decreases as the range of

decreases. In contrast, the trend of CY's income variation with changes in the pricing strategy range of

is less pronounced.

From

Figure 17 and

Figure 18, we can observe that carrier’s cost decrease as the range of

/

pricing strategy decreases, and increase as the range of

pricing strategy increases for most carriers. In comparison, CY's adjustment of pricing strategy ranges has a relatively smaller impact on carriers' transfer time. Thus, result 8 is derived.

Result 8:The impact of the pricing strategy range change ofon the income of CY and income of RCTY for the import shipping container is smaller than the impact of the pricing strategy range change ofon them. In addition, changes in the pricing strategy range of CY have no impact on the transfer time of carriers.

Insights for CY operators to focus on the critical impact of the pricing strategy, when adjusting pricing strategies, CY operators should prioritize adjusting because it has a more significant impact on the overall system. Particularly, changes in of range can notably affect CY's income and carrier costs, and a well-adjusted a1 strategy can lead to more effective revenue management. In addition, CY operators need to carefully balance these two aspects when adjusting the b1 strategy to ensure that while increasing revenue, carrier costs are not excessively increased, which could negatively affect relationships with carriers. If CY operators wish to influence RCTY's income through pricing strategies, adjusting the a1 pricing strategy may be a more effective approach.

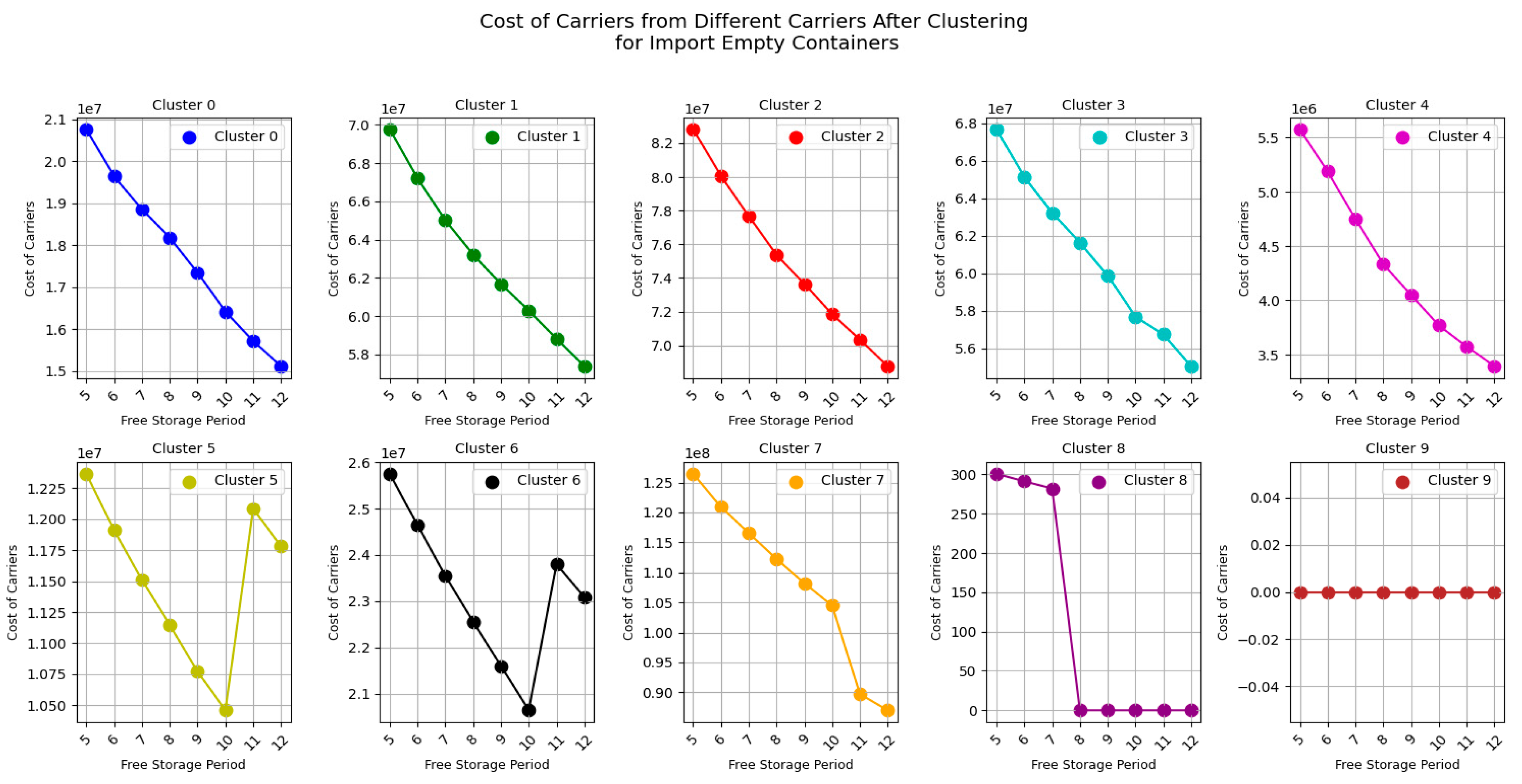

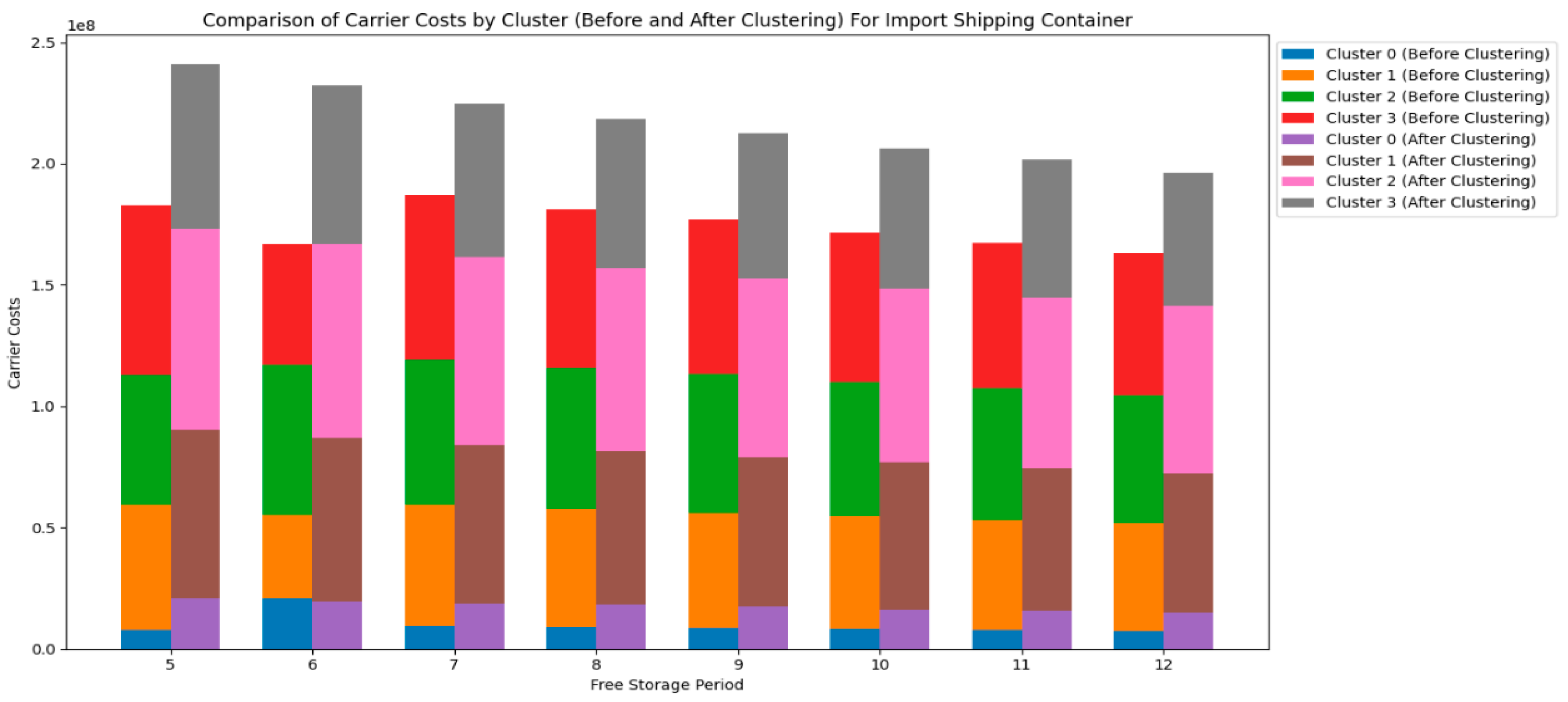

Next, let's look at the impact of sensitivity changes during the free storage period on the income of CY, the income of RCTY, the cost of the carrier, and the transfer time of the carrier for the import shipping container.

From

Figure 19 to

Figure 21, we can generally see that for almost all carriers, CY's income, RCTY's income, and the carrier's costs decrease as the free storage period set by CY increases. This is relatively simpler compared to the complex situation with import empty containers. However, in terms of RCTY's income, there are special cases for carriers like YHWP and THE4, which require separate discussion. There are two scenarios regarding the change in transfer time. In one scenario, the carrier's transfer time increases as the free storage period set by CY increases. In the other scenario, the carrier's transfer time remains unchanged regardless of the free storage period set by CY. The latter case may occur when the containers' dwell time at the port is relatively short, such that the dwell time for all containers of the carrier falls within the free storage period. Therefore, we can get result 10.

Result 10: CY's income, RCTY's income and carrier’s cost decrease as the free storage period increases.

This result provides the insights for CY operators that extending the free storage period may bring in less income, it can reduce carriers' costs to some extent, it may result in the port yard not being effectively utilized, potentially significantly reducing CY's operational efficiency. CY operators need to find a balance between the length of the free storage period, the availability of yard space, the carrier's costs and CY’s income.CY operators can consider closely collaborating with RCTY to jointly develop and adjust the free storage period strategy. This cooperation can not only help optimize overall income but also effectively manage yard space, avoiding issues of insufficient yard space caused by extended transfer time.

In general, in this section we explored the impact of the sensitivity of two different container types pricing strategy scope and free storage period sensitivity before the clustering to the income of CY, the income of RCTY, the carrier's cost, and the carrier's transfer time, providing CY’ managers with some insights into pricing strategies through relevant conclusions.

In the next section, we will explore the series of impacts and corresponding conclusions after the clustering to see if there are any differences between the two.

5.2.2. After the Clustering

Changes in sensitivity to price range and sensitivity to free storage period after the clustering has been shown in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

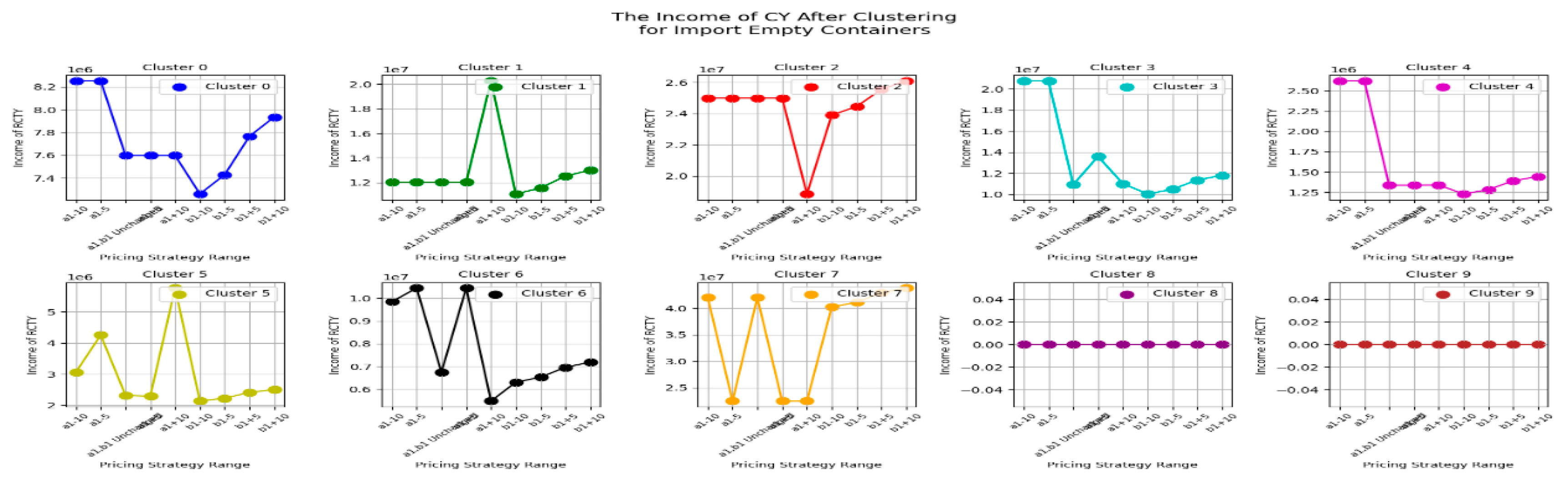

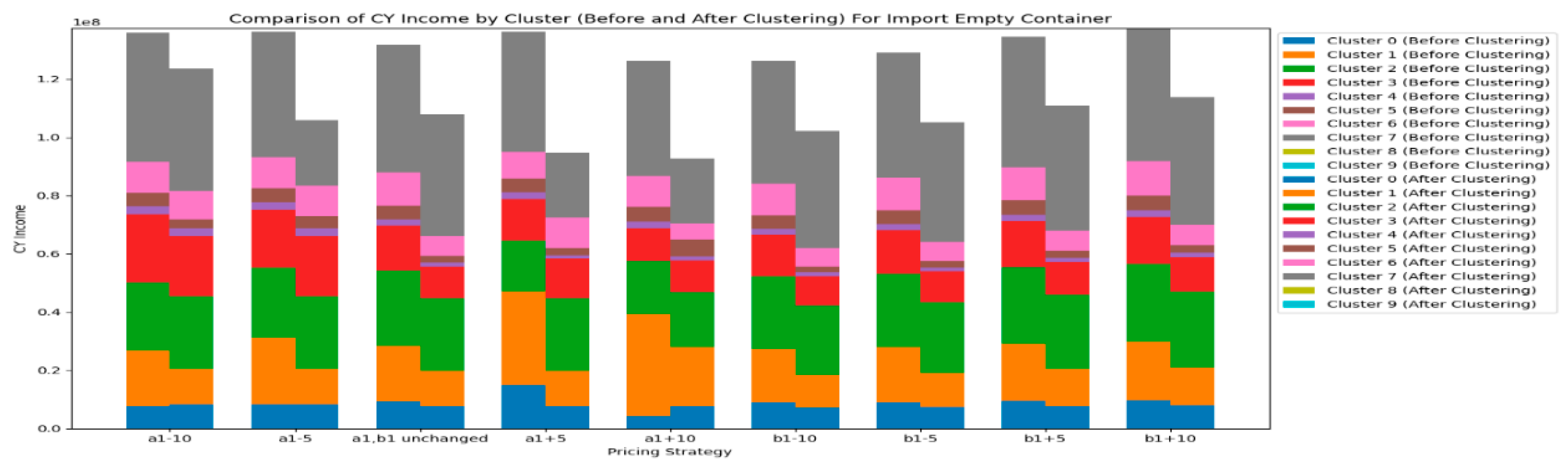

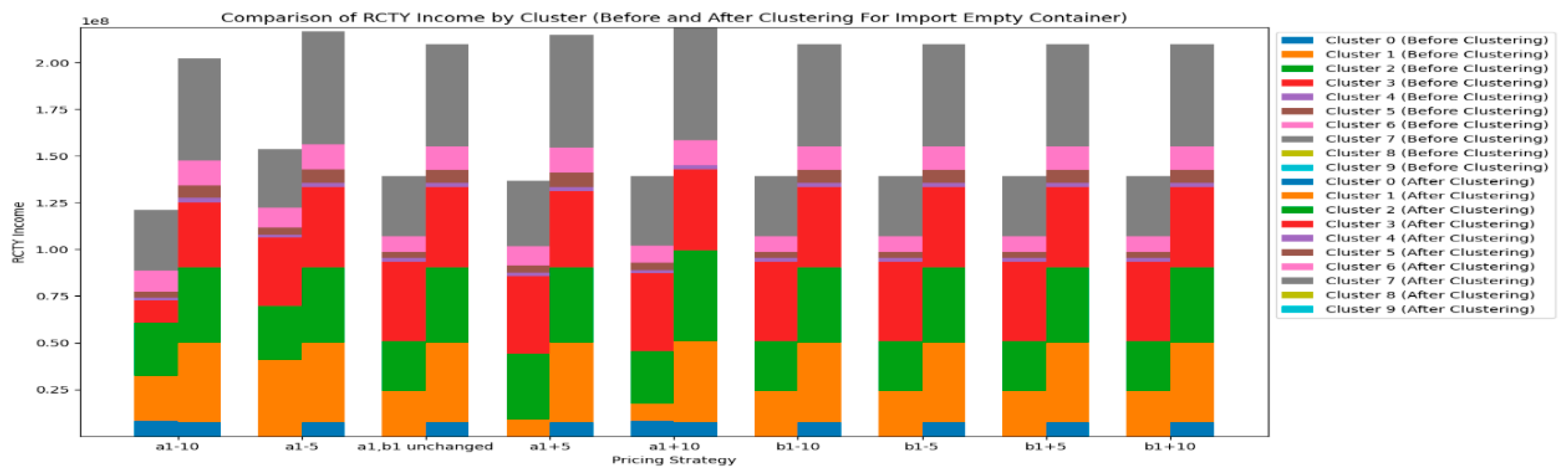

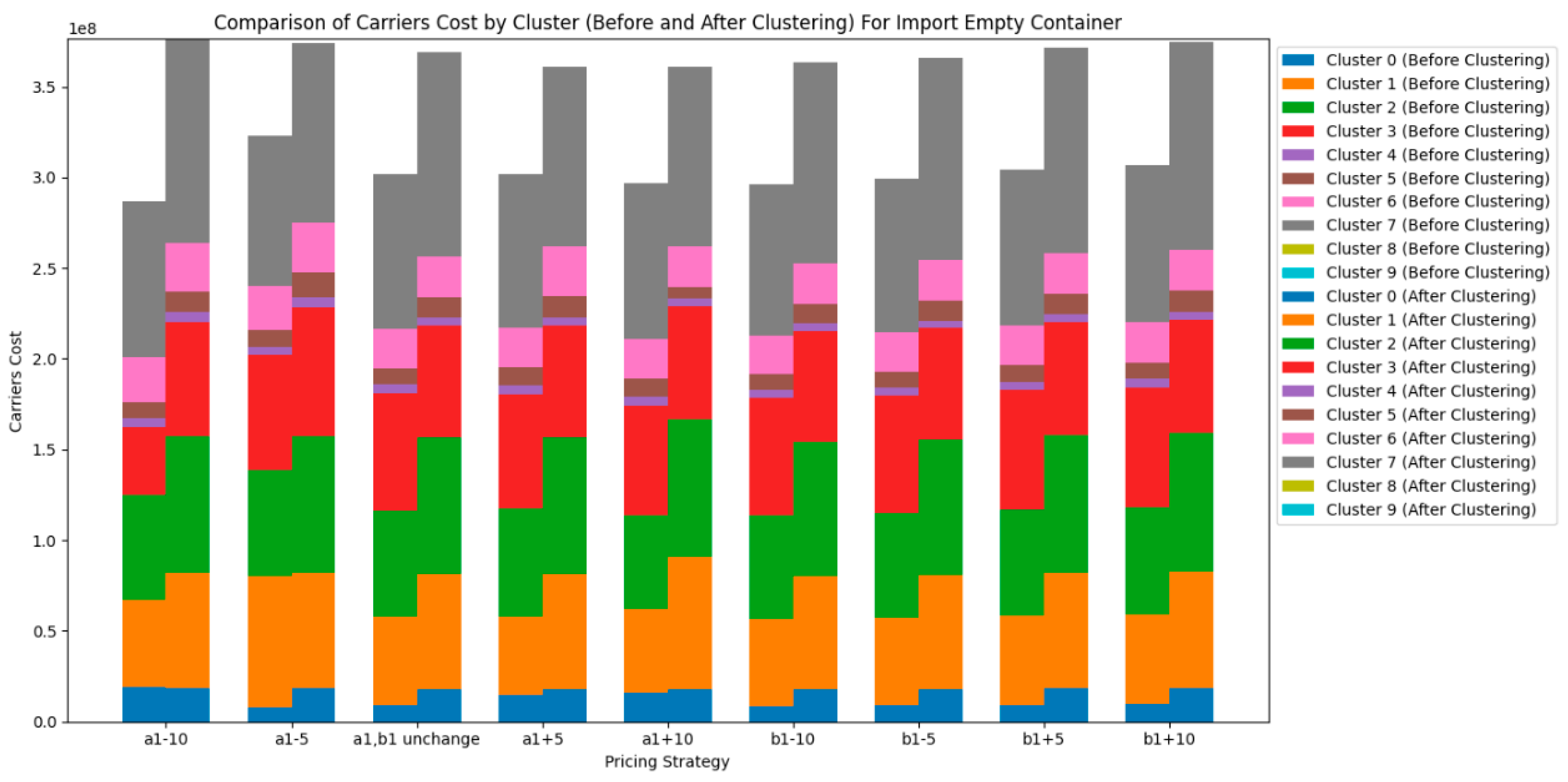

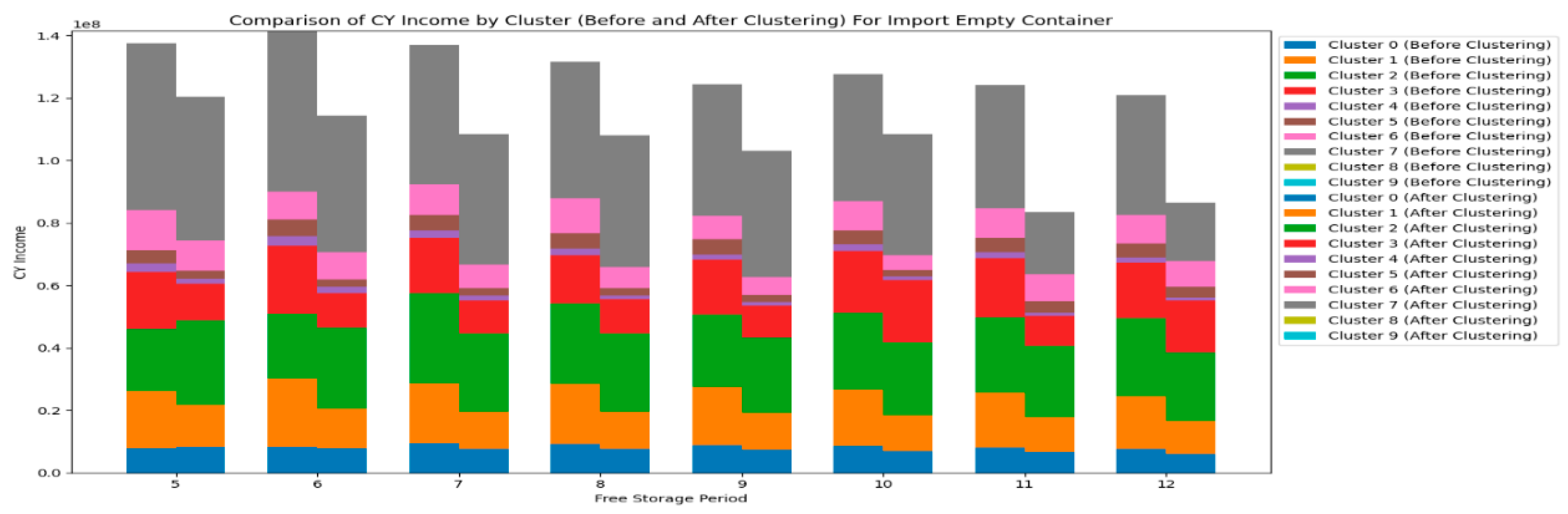

Next, let's look at the impact of sensitivity changes during the pricing strategy scope on the income of CY, the income of RCTY, the cost of the carrier, and the transfer time of the carrier for the import empty container after the clustering.

Figure 23.

The CY’s income under different pricing strategy scope for import empty containers after the clustering.

Figure 23.

The CY’s income under different pricing strategy scope for import empty containers after the clustering.

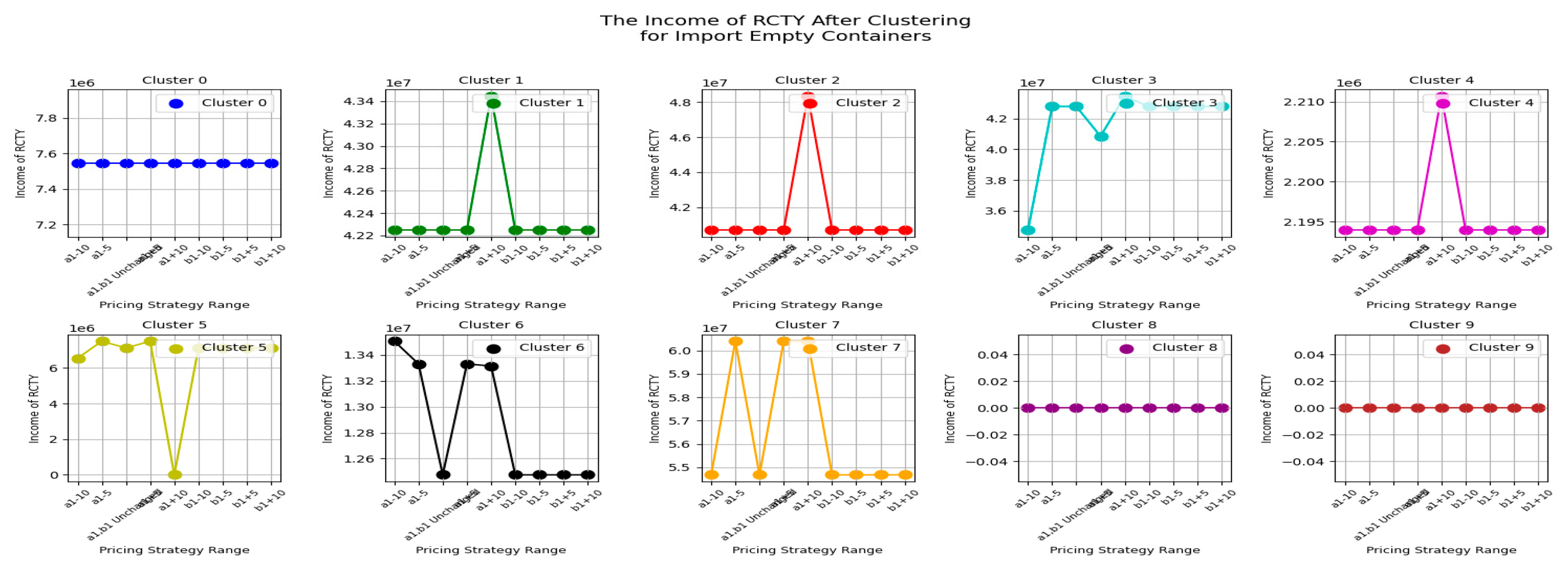

Figure 24.

The RCTY’s income under different pricing strategy scope for import empty containers after the clustering.

Figure 24.

The RCTY’s income under different pricing strategy scope for import empty containers after the clustering.

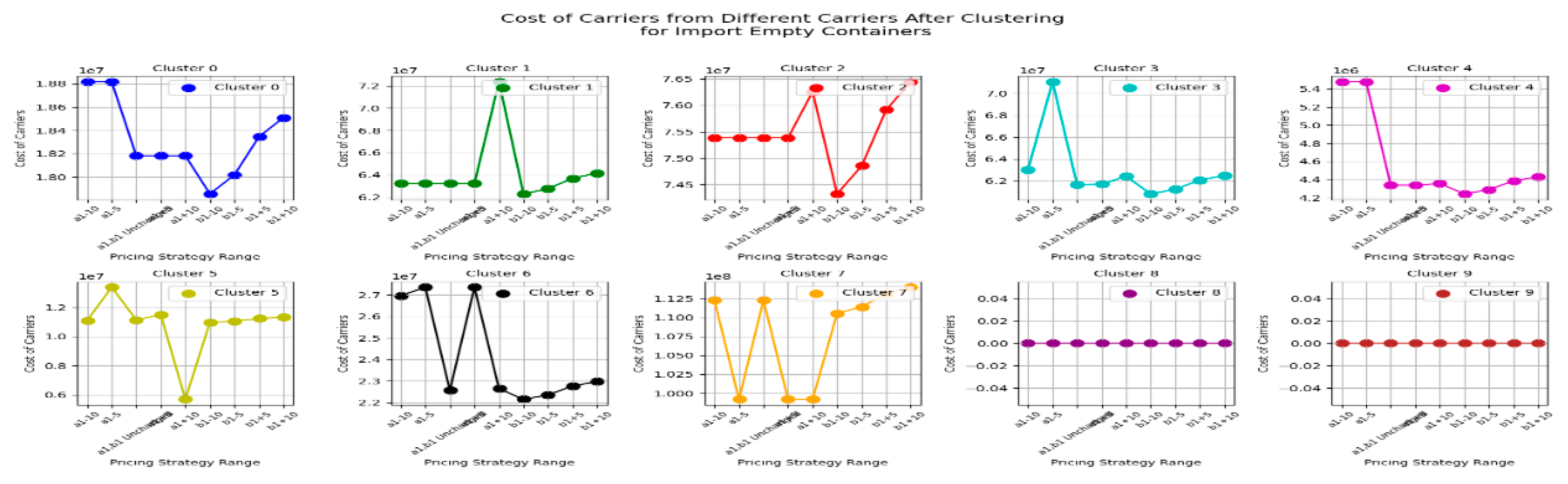

Figure 25.

The carrier’s cost under different pricing strategy scope for import empty containers after the clustering.

Figure 25.

The carrier’s cost under different pricing strategy scope for import empty containers after the clustering.

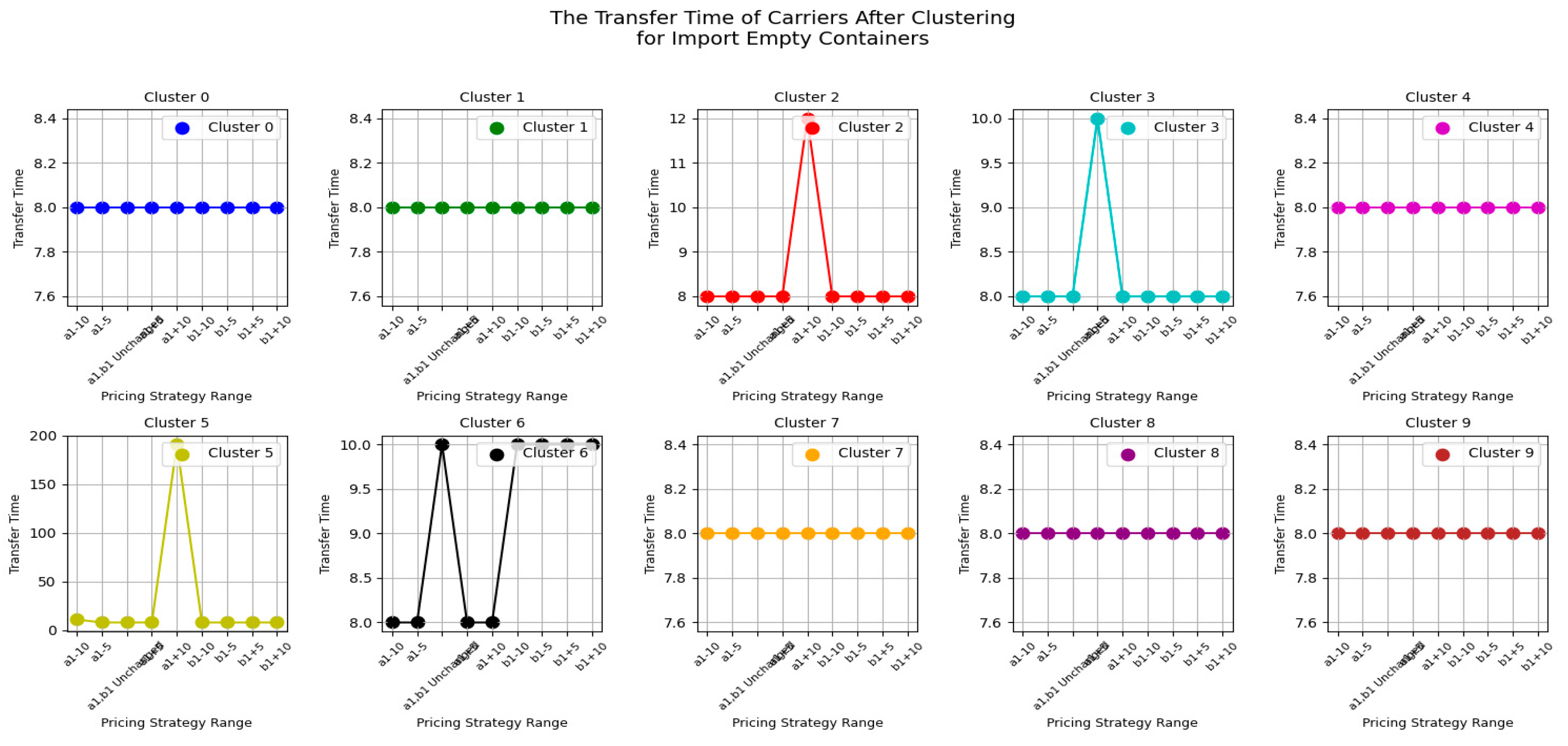

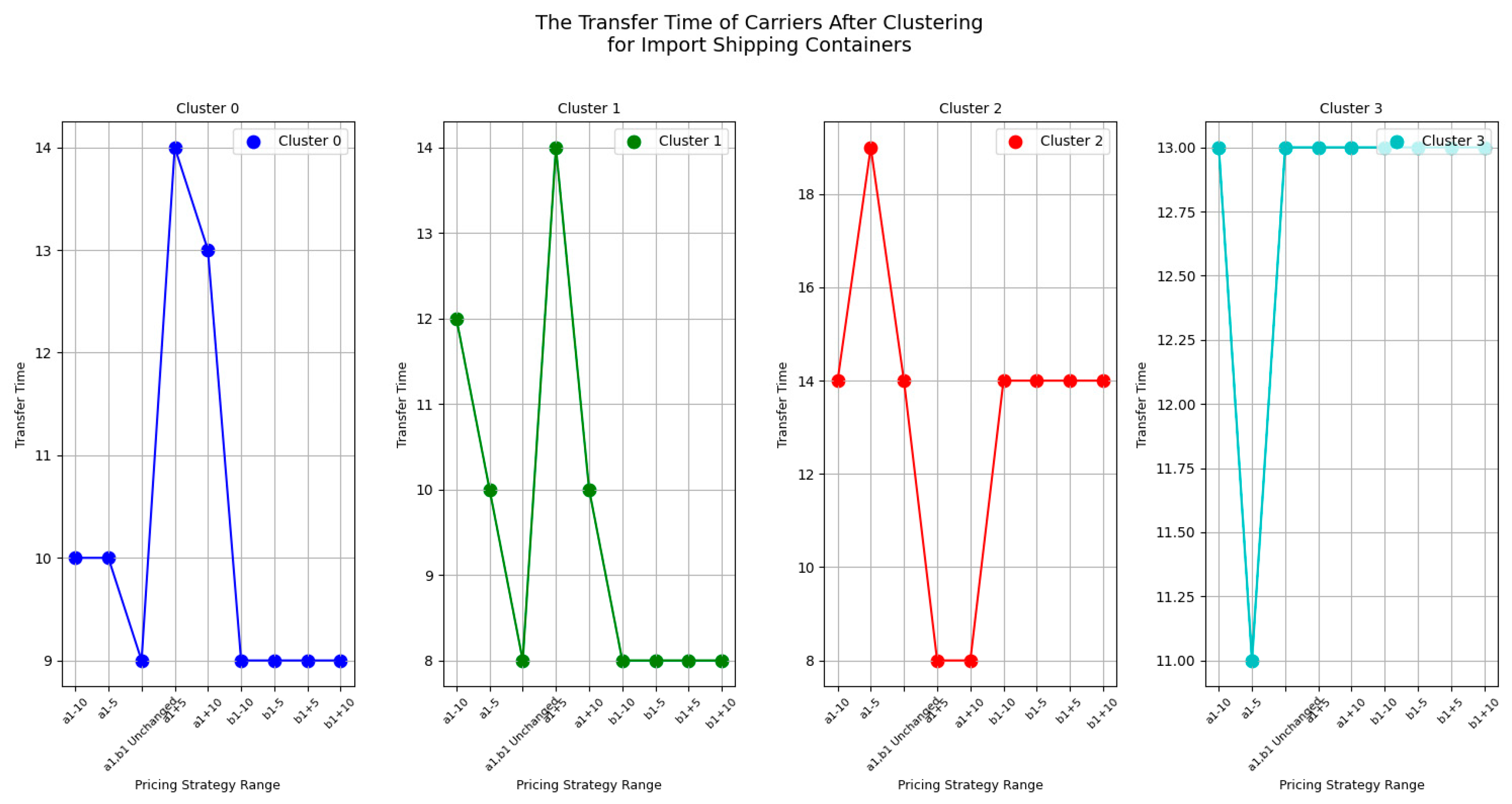

Figure 26.

The carrier’s transfer time under different pricing strategy scope for import empty containers after the clustering.

Figure 26.

The carrier’s transfer time under different pricing strategy scope for import empty containers after the clustering.

After clustering the carriers, the income of CY and the carriers' costs decrease with the expansion of the reduction range and increase with the expansion of the increment range. This trend is consistent with that before clustering. However, the impact of changes in the pricing strategy range on CY's income and carriers' costs varies within each cluster.

Additionally, CY's adjustment of the b1 pricing strategy range does not affect RCTY's income. Similarly, when adjusting the pricing strategy range, the impact on RCTY's income varies due to the characteristics of the carriers within the cluster, resulting in uncertainty. Adjusting the pricing strategy range does not significantly impact carriers' transfer times. Except for a few clusters where an increase of 10 in the pricing strategy range caused significant changes in carriers' transfer time, no changes were observed in other cases.

Therefore, we can draw result 11

Result 11: After clustering import empty containers, adjusting thepricing strategy range consistently influences the income of the port yard and carriers' costs in a predictable manner, while changes in thepricing strategy range introduce variability depending on the characteristics of carriers within each cluster.

The conclusion provide the insight that CY operators, when adjusting the pricing strategy range for b1, should consider not only the changes in their own income but also the impact on the costs for carriers. If CY operators wish to establish a closer cooperative relationship with RCTY, they can simultaneously adjust the pricing strategies of and . By finely tuning , they can achieve a balance between their own revenue and the costs of the carriers; while CY may need to share some of its income with RCTY to strengthen their collaboration.

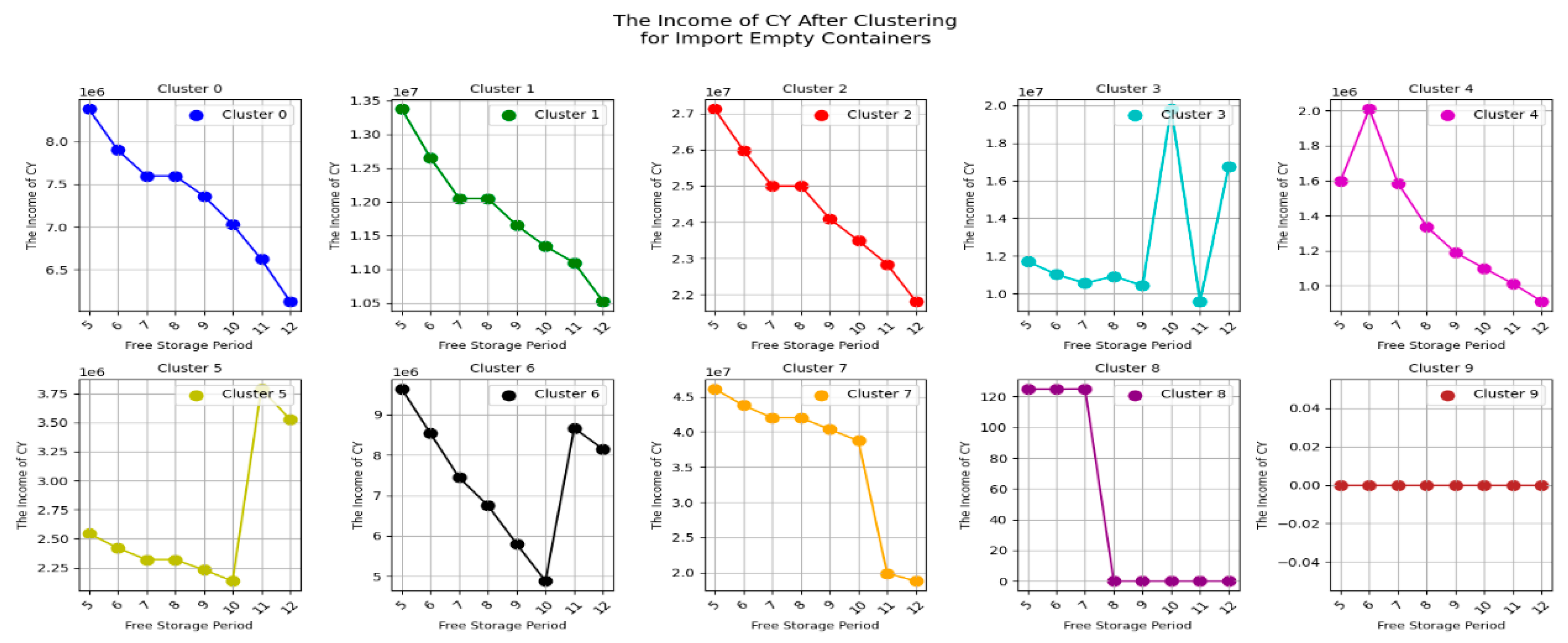

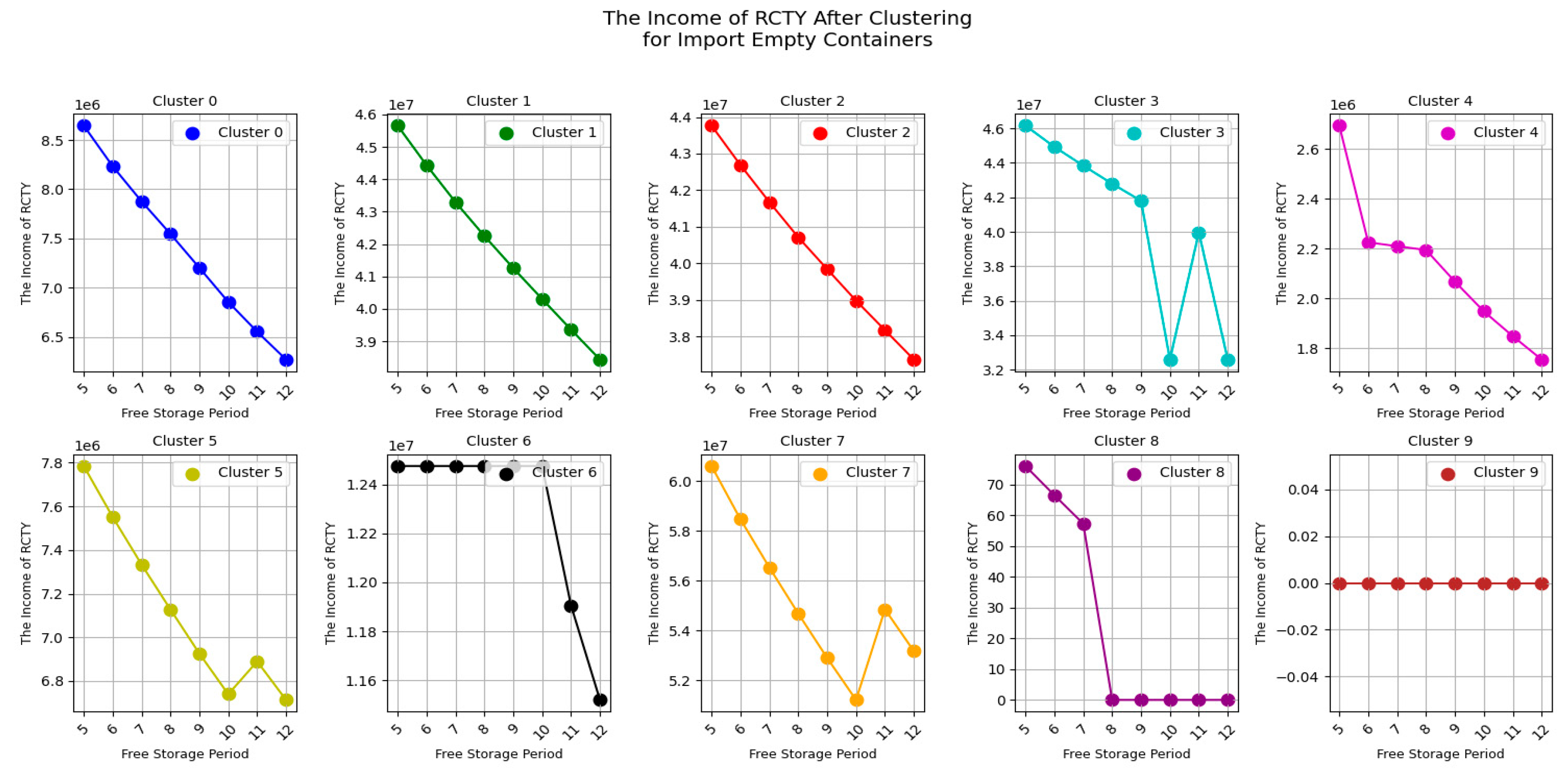

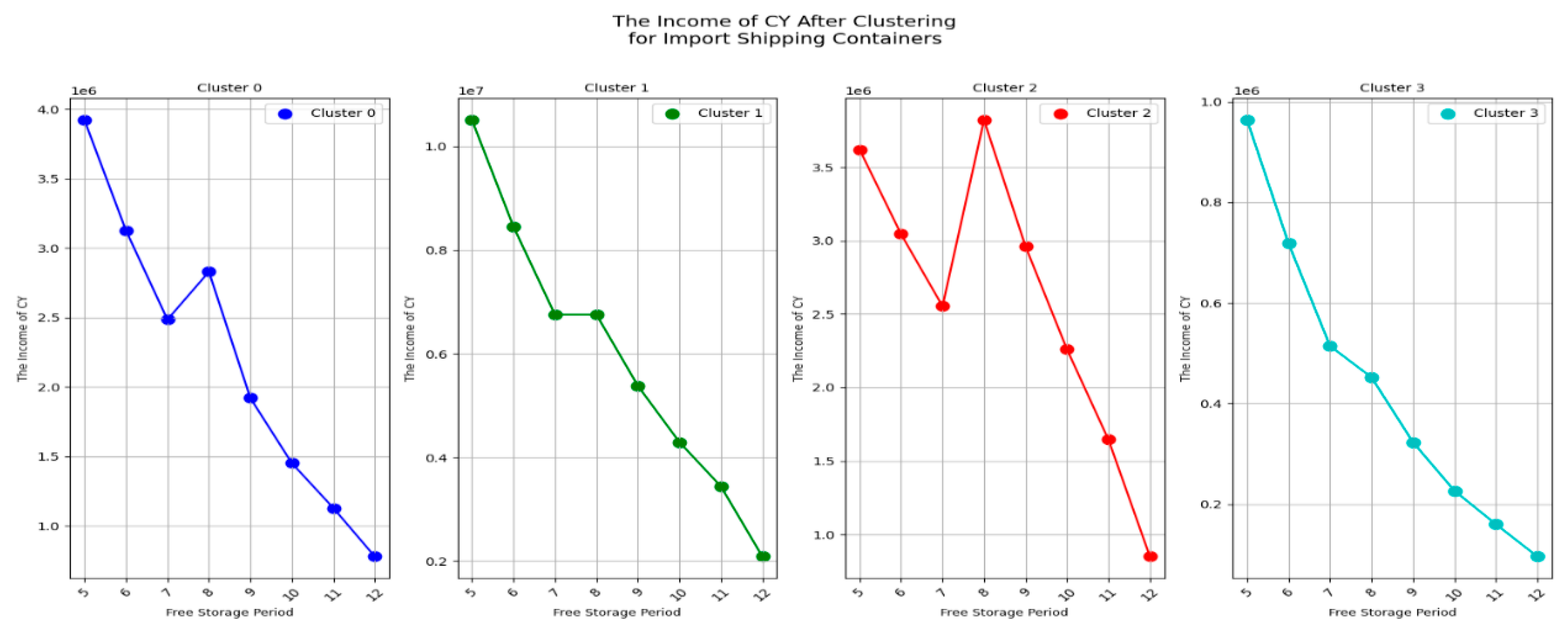

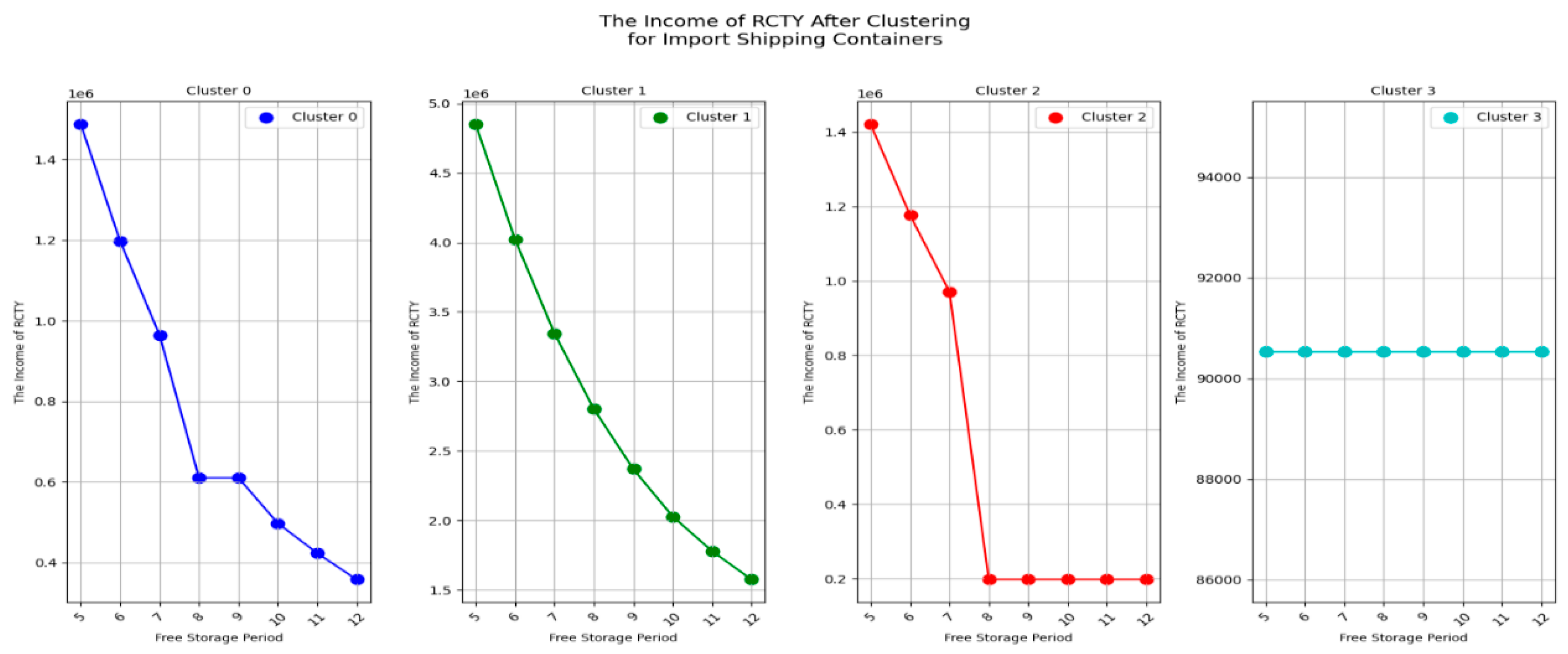

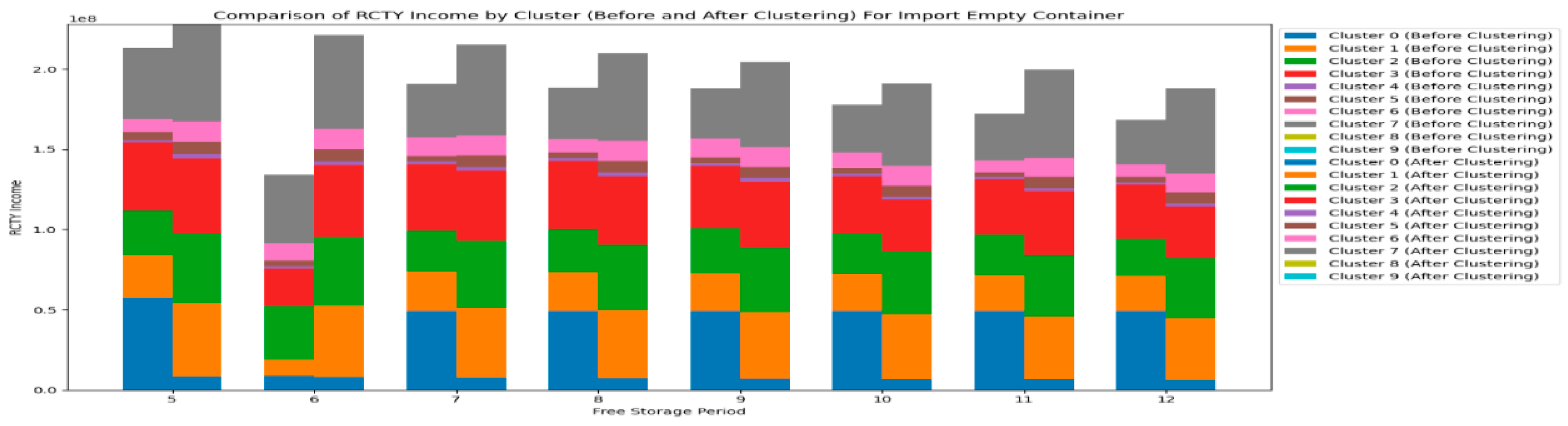

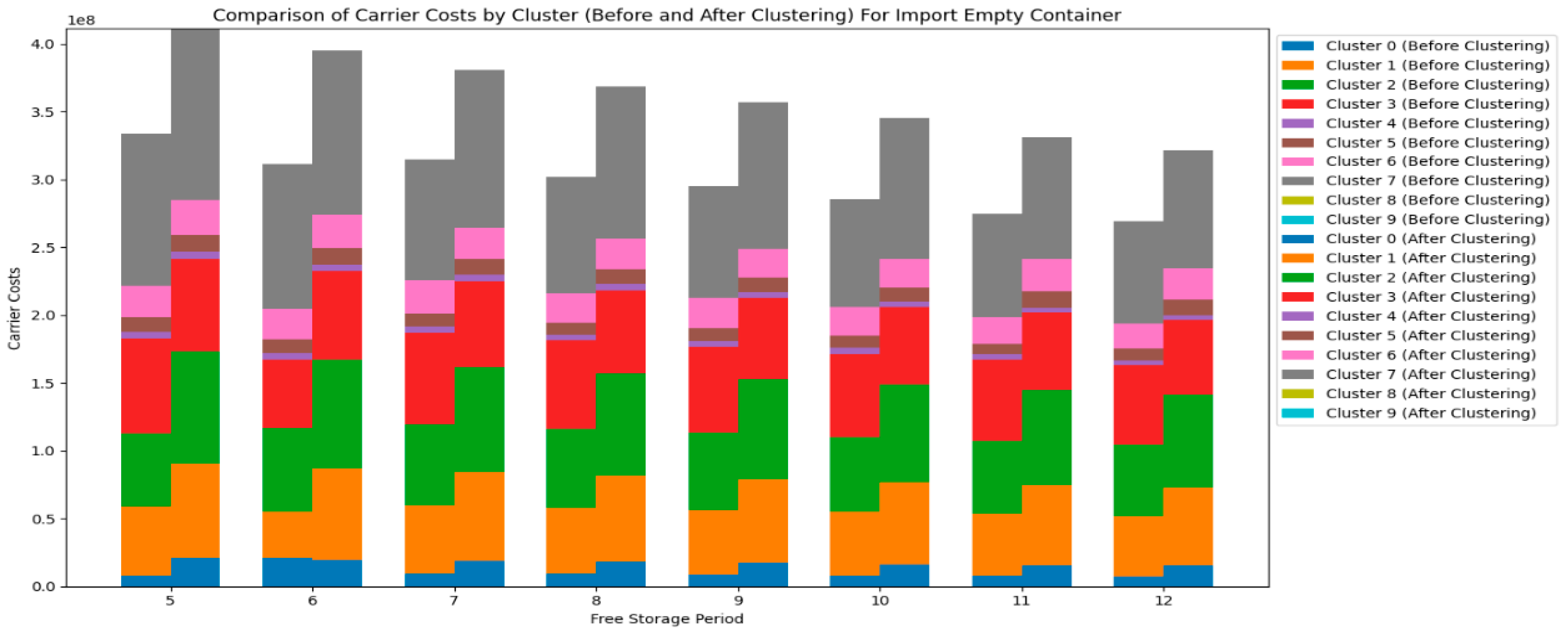

Next, let's look at the impact of sensitivity changes during the free storage period on the income of CY, the income of RCTY, the cost of the carrier, and the transfer time of the carrier for the import empty container.

From

Figure 27,

Figure 28,

Figure 29 and

Figure 30, we can see that for the import empty containers after the clustering, the income of the CY, the carrier's costs and the income of RCTY decrease as the free storage period increases. However, CY's income may fluctuate with the extension of the free storage period, but the overall trend is a decline. In contrast, the carrier's transit time increases with the extension of the free storage period.

Result 12: While longer periods reduce carrier costs and RCTY's income, the fluctuating CY income suggests potential inefficiencies, extending the free storage period also leads to increased carrier transit time.

The result provides the following insights for CY operators to consider potential income changes when setting the free storage period and optimize their free storage period strategy .In addition, CY operators need to weigh the impact of the free storage period on revenue and port operational efficiency, avoiding congestion or resource strain in the yard due to excessively long storage periods. Therefore, CY operators can consider partnering with RCTY to alleviate yard pressure caused by the extension of the free storage period by sharing storage space. This not only helps increase RCTY's income but also expands the available stacking space for CY, optimizing overall operational efficiency.

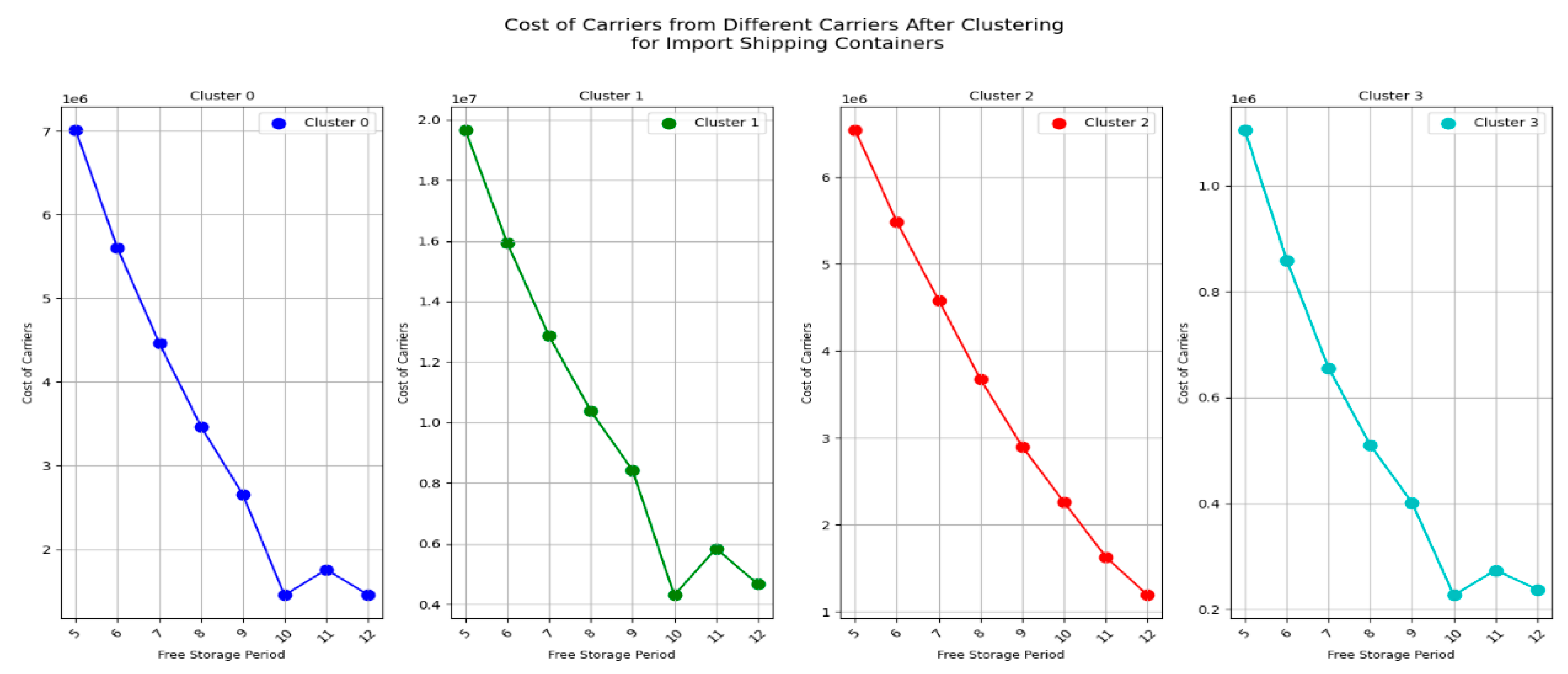

Similarly, let's take a look at the impact of changes in pricing strategy range and changes in the free storage period on the import shipping containers after the clustering.

From

Figure 31 and

Figure 33, we can see that for import shipping containers after the clustering, the income of CY and cost of carrier increase with the degree of increase in the

pricing strategy range set by CY and decrease with the degree of reduction in the

pricing strategy range. From

Figure 32 and

Figure 34, we can see that RCTY’s income and carrier’s transfer time are not affected by the

pricing strategy range set by CY. From this, we derive result 13.

s

So CY's operators may not need to worry too much about the direct effects on their own income when considering the pricing strategy range of . More resources and energy can be invested in other more influential operational strategies. At the same time, the impact of pricing strategy 's range fluctuations is uncertain, which suggests that CY's operators need to be more cautious when formulating or adjusting the range of pricing strategy, which may need to rely on more detailed data analysis and simulations to predict potential impacts under different scenarios. If CY's operators wish to reduce carrier’s costs, they might consider appropriately narrowing the range of the pricing strategy, but they also need to balance other operational metrics that may be affected.

Let's take a look at the impact of changes in the free storage period.

From

Figure 35,

Figure 36 and

Figure 37, we can see that similar to the impact of changes in the free storage period on the income or costs of the three parties after clustering for import empty containers, for import shipping containers after clustering, the income of CY, the income of RCTY, and the carrier's costs decrease as the free storage period increases. In contrast, the carrier's transit time increases as the free storage period extends, which is consistent with the trend observed for clustered import empty containers. From this, we derive result 14.

Result 14: After clustering, both import empty containers and import shipping containers show similar trends.

Result 14 suggests that CY operators should be cautious when setting the free storage period, as a longer free storage period could lead to a decline in income. The extension of the free storage period may also result in lower costs for carriers. This could be beneficial for carriers, but for CY, if it hopes to maintain or increase income, it needs to find a balance that attracts carriers without significantly reducing income.

In general, in this section we explored the impact of the sensitivity of two different container types pricing strategy scope and free storage period sensitivity after the clustering to the income of CY, the income of RCTY, the carrier's cost, and the carrier's transfer time, providing CY managers with some insights into pricing strategies through relevant conclusions.

So far, we have discussed the impact of changes in the range of pricing strategies and the free storage period before and after the clustering. Next, we would like to discuss the differences in solving speed, objective function, and conclusions before and after the clustering.

5.3. Comparison Before and After the Clustering

First, let's take a look at the solution times for each cluster before and after the clustering under different pricing strategy ranges and different free storage periods.

Note: The following abbreviations related to pricing strategy ranges—"-10", "-5", "+5", "+10", "-10", "-5", "+5", "+10"—represent a decrease of 10 in the pricing strategy range for , a decrease of 5 in the pricing strategy range for , an increase of 5 in the pricing strategy range for , an increase of 10 in the pricing strategy range for , a decrease of 10 in the pricing strategy range for , a decrease of 5 in the pricing strategy range for , an increase of 5 in the pricing strategy range for , and an increase of 10 in the pricing strategy range for , respectively.

Significant reduction in overall program running time.

Table 5 and

Table 6: For import empty containers, the overall running time significantly decreased after clustering.

Table 5 shows that the total running time before clustering ranged from 13,094.9 seconds to 14,716.4 seconds, while

Table 8 shows that after clustering, this range reduced to 2,054.6 seconds to 2,293.6 seconds. This indicates that the clustering strategy greatly optimized the program's computational efficiency, leading to a substantial reduction in running time. For import shipping containers, a similar reduction in time was observed after clustering. The total running time before clustering ranged from 3,737.01 seconds to 4,458.96 seconds, while after clustering, it decreased to a range of 167.9 seconds to 499.65 seconds.

In addition, equalization of running time across clusters. Import Empty Containers (

Table 5 and

Table 6): Before clustering, the running time across clusters varied significantly, especially with Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 being much higher than the others. After clustering, these differences significantly decreased. For example, in the a

1-10 strategy, the running time for Cluster 1 dropped from 936.83 seconds to 181.15 seconds, making it closer to the other clusters.

Import shipping container (

Table 7): Similarly, after clustering, the running time across clusters became more balanced. In

Table 7, the running time for Cluster 1 decreased from several thousand seconds to just a few hundred seconds, showing that the clustering strategy helps in more evenly distributing computational resources across different container types.

Next, reduced impact of pricing strategies on running time. Import empty containers (

Tables 5and 6): before clustering, different pricing strategy ranges had a significant impact on the running time across clusters, especially for Cluster 2. For example, in

Table 5, the running time for Cluster 2 varied by several hundred seconds between the

-10 and

+10 strategies. After clustering (

Table 6), this variation reduced significantly to within a few dozen seconds, indicating that the program's stability improved greatly after clustering. Import shipping containers (

Table 7): Similarly, after clustering, the impact of different pricing strategies on each cluster was reduced. For example, under the a

1-10 pricing strategy, the running time after clustering was 328.34 seconds, which is a significant reduction compared to before clustering, and it became more stable.

Whether dealing with import empty containers or import shipping containers, the clustering strategy significantly optimized the program's running time, made the running time across clusters more balanced, and reduced the impact of pricing strategies on the program's stability.

Considering Tables 5, 6, and 7, the clustering strategy has shown excellent performance in enhancing computational efficiency, balancing computational load, and reducing the impact of pricing strategies on running time. This is crucial for maintaining efficient and stable system operation in complex operational environments.

A comparative analysis of the data presented in

Table 8 and

Table 9 elucidates the substantial impact of clustering on program running times for import empty container. The comparison of import empty container clustering before and after clustering shows that the clustering scheme effectively reduces operating time in most cases, especially when the free storage period is shorter. The data after clustering indicates that the operating time of most clusters has significantly decreased, optimizing the overall system efficiency. For example, clusters such as Cluster 0, Cluster 1, and Cluster 2 show the most noticeable reduction in operating time when the free storage period is shorter, suggesting that the clustering scheme effectively improves the pricing efficiency of carriers within these clusters.

Table 9.

Operating Time of Different Free Storage Period for Each Cluster After Clustering of Import Empty Container.

Table 9.

Operating Time of Different Free Storage Period for Each Cluster After Clustering of Import Empty Container.

| After the Clustering |

|---|

| Free Storage Period |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

| Cluster 0 |

152.33 |

175.50 |

182.14 |

221.13 |

221.64 |

212.00 |

212.18 |

117.01 |

| Cluster 1 |

153.66 |

162.50 |

155.43 |

195.00 |

189.90 |

184.20 |

176.47 |

96.01 |

| Cluster 2 |

393.40 |

390.65 |

428.99 |

462.57 |

483.23 |

436.30 |

433.41 |

272.49 |

| Cluster 3 |

430.48 |

465.57 |

450.70 |

457.73 |

437.26 |

415.67 |

418.92 |

266.71 |

| Cluster 4 |

195.38 |

89.74 |

100.19 |

185.49 |

164.04 |

159.41 |

149.17 |

126.96 |

| Cluster 5 |

110.46 |

242.06 |

290.37 |

112.05 |

106.48 |

105.41 |

240.78 |

233.28 |

| Cluster 6 |

264.20 |

300.37 |

368.24 |

267.23 |

252.09 |

231.17 |

205.36 |

211.09 |

| Cluster 7 |

401.64 |

464.56 |

505.51 |

322.94 |

320.67 |

267.87 |

104.84 |

115.85 |

| Cluster 8 |

0.42 |

0.54 |

9.28 |

7.79 |

7.24 |

6.08 |

5.87 |

6.29 |

| Cluster 9 |

11.13 |

13.89 |

26.65 |

7.41 |

7.53 |

6.39 |

6.19 |

7.26 |

| Total |

2113.1 |

2305.4 |

2517.5 |

2239.4 |

2190.1 |

2024.5 |

1953.2 |

1453.0 |

Table 10.

Operating Time of Different Free Storage Period for Each Cluster Before Clustering of Import Shipping Container.

Table 10.

Operating Time of Different Free Storage Period for Each Cluster Before Clustering of Import Shipping Container.

| Before the Clustering |

|---|

| Free Storage Period |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

| Cluster 0 |

2271.23 |

1681.73 |

2164.47 |

1770.07 |

1741.59 |

1647.96 |

1614.07 |

1863.95 |

| Cluster 1 |

2856.62 |

2223.96 |

2784.71 |

2342.78 |

2318.17 |

2278.03 |

2231.8 |

2566.51 |

| Cluster 2 |

69.54 |

98.97 |

70.83 |

68.69 |

71.37 |

70.47 |

72.49 |

73.15 |

| Cluster 3 |

102.27 |

78.78 |

99.97 |

91.18 |

89.83 |

86.03 |

85.73 |

88.64 |

| Total |

5299.66 |

4083.44 |

5119.98 |

4272.72 |

4220.96 |

4082.49 |

4004.09 |

4592.25 |

Table 11.

Operating Time of Different Free Storage Period for Each Cluster After Clustering of Import Shipping Container.

Table 11.

Operating Time of Different Free Storage Period for Each Cluster After Clustering of Import Shipping Container.

| After the Clustering |

|---|

| Free Storage Period |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

| Cluster 0 |

68.87 |

87.83 |

96.93 |

122.45 |

103.74 |

100.73 |

99.36 |

60.77 |

| Cluster 1 |

163.94 |

182.10 |

180.10 |

221.91 |

211.06 |

207.62 |

198.55 |

128.03 |

| Cluster 2 |

96.35 |

98.17 |

99.07 |

133.62 |

132.65 |

126.50 |

124.42 |

83.09 |

| Cluster 3 |

18.76 |

18.45 |

18.11 |

21.66 |

20.39 |

20.33 |

20.05 |

12.57 |

| Total |

347.91 |

386.54 |

394.21 |

499.65 |

467.83 |

455.18 |

442.38 |

284.46 |

However, although most clusters benefit from clustering, a few clusters, such as Cluster 8 and Cluster 9, show an increase in operating time after clustering, particularly when the free storage period is longer. This phenomenon is more pronounced, but fortunately, the pricing running time for these two clusters does not show significant deviation, which is within an acceptable range.

A comparative analysis of the data presented in

Table 8 and

Table 9 for import shipping container. The clustering of import shipping containers has significantly reduced operating times across the board, with particularly strong improvements seen in clusters with initially higher operating times. This indicates that the clustering scheme effectively optimizes the management of import heavy containers, improving overall operational efficiency. Even clusters that showed less dramatic changes still benefited from reduced operating times, suggesting that the clustering process is broadly effective.

Overall, clustering has a noticeable optimization effect on operating time, especially when the free storage period is shorter. The operating time of most clusters has significantly decreased, leading to a marked improvement in the pricing efficiency of CY. For import empty containers, running times before clustering varied significantly across clusters, with some clusters, such as Cluster 1 and Cluster 2, exhibiting considerably higher time. Post-clustering, running times across clusters became more uniform, with a general reduction observed; for example, Cluster 1's time decreased from 881.91 seconds to 195.00 seconds. Likewise, for import shipping containers, there was a notable variation in running times across clusters before clustering, particularly in Cluster 0 and Cluster 1. After clustering, running times became more balanced, with substantial reductions across all clusters, such as Cluster 0's time dropping from 1,770.07 seconds to 122.45 seconds. This analysis indicates that clustering effectively reduces discrepancies in running times across clusters and optimizes performance stability, regardless of the container type or storage period.

Analyzing

Figure 39,

Figure 40 and

Figure 41 before and after clustering for different pricing strategy ranges of import empty containers, we can observe that for import empty containers, the clustering of carriers by CY (Container Yard) for pricing leads to a decrease in CY's overall income, while the income for RCTY (Regional Container Transfer Yard) increases, and the storage costs for carriers rise. Therefore, port operators may consider using the pricing strategy based on carrier clustering to negotiate with RCTY for cooperation. This approach could not only improve the pricing efficiency of CY towards carriers but also enhance the utilization of storage space within the yard by collaborating with RCTY, thereby improving the operational efficiency of the yard within the port.

From the perspective of different clusters, clustering has had varying impacts on pricing. Taking Cluster 1 as an example, the pricing after clustering significantly increased the terminal yard revenue, especially under the +10 strategy, where the revenue rose from 35,068,780.37 to 20,250,708.62, demonstrating that the post-clustering pricing strategy effectively enhanced the revenue generated from cluster carriers at the terminal yard. In contrast, the pricing strategies for Cluster 0 and Cluster 3 led to a decrease in terminal yard revenue, especially under the -10 and +10 strategies, where revenue dropped from 7,723,415.80 and 23,508,019.68 to 8,252,695.16 and 20,762,119.15, respectively. This suggests that the optimization effect of clustering on these clusters is not as significant as on others.

Overall, clustering, through different pricing strategies, has increased the CY’s income of most clusters. Although some clusters experienced a decrease in CY’s income under certain strategies, clustering generally enhances the overall pricing efficiency by refining pricing strategies. Moreover, the change in CY income is directly associated with the pricing strategy. An increase in the pricing strategy range typically leads to higher cluster CY’s income, especially under higher pricing strategies range, where CY's income grows more significantly. However, different clusters react differently, and the income growth of some clusters' CY may be limited. Therefore, more precise pricing strategies need to be developed based on the characteristics of each cluster.

From the perspective of RCTY Income, before clustering, there was a significant variation in RCTY Income across different pricing strategies. For example, the RCTY Income for Cluster 1 was 24,017,177.55 under the a1-10 strategy, but it dropped to 9,008,367.32 under the +10 strategy. This suggests that for some clusters (such as Cluster 1), RCTY Income remains relatively stable under certain pricing strategy ranges, but it can decrease significantly under other pricing strategy ranges. A similar trend can be observed in other clusters, particularly in Cluster 0, Cluster 2, and Cluster 3, where the Income fluctuates considerably under different pricing strategy ranges. After clustering, the adjustment of pricing strategy ranges significantly improved RCTY Income for most clusters, especially for Cluster 1 and Cluster 3. For instance, under the +10 strategy, Cluster 1’s income increased from 9,008,367.32 to 43,448,855.98, indicating that the post-clustering pricing strategy significantly enhanced the RCTY Income for this cluster.

From the perspective of carriers’ cost, the data before and after clustering indicates significant differences in the impact of CY's pricing strategy ranges on carrier costs. Before clustering, some clusters (such as Cluster 1 and Cluster 3) showed considerable cost fluctuations under different pricing strategies. For example, Cluster 1 had a carrier cost of 48,276,534.77 under the -10 strategy, which decreased to 46,125,203.99 under the +10 strategy, demonstrating sensitivity to the pricing strategy. After clustering, the cost volatility of many clusters decreased, particularly for Cluster 1 and Cluster 7, indicating that optimizing the pricing strategy can effectively stabilize carrier costs. Specifically, after clustering, the cost for Cluster 1 fluctuated between 62,288,807.97 and 72,354,924.14 under the -10, +5, and +10 strategies, reflecting improved stability in pricing strategies post-clustering. However, it is important to note that while stability increased, the overall costs for certain clusters (such as Cluster 1 and Cluster 7) increased, especially under the +10 strategy.

Therefore, the analysis before and after clustering indicates that CY needs to develop different pricing strategies for different clusters to reduce cost fluctuations and optimize carrier cost control. By refining and differentiating the pricing strategy, CY income can be maximized across different clusters, and the pricing range can be flexibly adjusted based on the characteristics and demand fluctuations of each cluster. High pricing strategies have significant potential to increase revenue in clusters with higher demand and stronger capacity, while clusters with lower demand should avoid excessively high pricing to maintain revenue stability. Ultimately, through continuous dynamic adjustments and regular optimization, CY can improve overall operational efficiency and income.

Next, let's look at the changes in the income/cost of the third party for import shipping containers before and after clustering, under different pricing strategy ranges set by CY.

Analyzing

Figure 42,

Figure 43 and

Figure 44 before and after clustering for different pricing strategy ranges of import shipping containers, CY income in Cluster 0 showed a decline with wider pricing strategy ranges, while Cluster 1 remained relatively stable but still saw a slight decrease when the pricing range increased. Cluster 2 exhibited substantial fluctuations, particularly with larger pricing strategy ranges, leading to a notable decrease in CY income. Cluster 3's income remained lower and stable. After clustering, Cluster 0's CY income improved, especially with reduced pricing ranges, while Cluster 1 showed reduced fluctuations and maintained higher income. Cluster 2 saw an increase in CY income, especially under narrower pricing ranges. Cluster 3 showed minimal changes.

For RCTY income, before clustering, Cluster 0 had stable income, especially with wider pricing ranges. Cluster 1 maintained a high and stable income but decreased slightly with reduced ranges. Cluster 2 showed greater fluctuations, especially with expanded pricing ranges. After clustering, Cluster 0's RCTY income increased with smaller pricing ranges, while Cluster 1 showed fluctuations but generally maintained a high level. Cluster 2’s income rose, particularly under -10 and , unchange strategies. Cluster 3's income remained stable.

Regarding carrier costs, before clustering, Cluster 0 showed a slight decrease as the pricing strategy range expanded, while Cluster 1 experienced consistently high costs. Cluster 2 showed volatility, and Cluster 3 had the lowest and most stable costs. After clustering, Cluster 0's carrier costs increased with narrower pricing ranges. Cluster 1 saw more variation, and Cluster 2's costs increased, particularly with certain strategies. Cluster 3’s costs remained stable.

The analysis suggests that clustering helps in identifying distinct cost and income patterns within clusters, allowing port operators to optimize pricing strategies. By using differentiated pricing strategies, especially for clusters with more volatility, operators can reduce income fluctuations and better manage carrier costs, leading to more stable and optimized revenue streams.

Analyzing

Figure 45,

Figure 46 and

Figure 47 before and after clustering for different free storage periods of import empty containers, the changes in CY Income under different free storage periods before and after clustering indicate that clustering optimized the income performance across clusters. Before clustering, different clusters showed significant differences in response to changes in the free storage period, especially Cluster 0 and Cluster 2, where income decreased as the free storage period increased, demonstrating sensitivity to the free storage period. After clustering, the income fluctuations across clusters were significantly reduced, particularly under shorter free storage periods, with improved income performance and greater stability. For example, Cluster 0 and Cluster 2 saw a notable increase in income under shorter free storage periods, while Cluster 1 showed higher income stability.

The changes in RCTY income before and after clustering under different free storage periods indicate that clustering optimized the RCTY income performance between clusters, particularly reducing the volatility of RCTY income when the free storage period was shorter. Before clustering, different clusters showed a strong sensitivity to changes in the free storage period, especially Cluster 0 and Cluster 2, where RCTY income exhibited a significant decline during longer free storage periods, showing greater volatility. After clustering, the volatility of RCTY income across clusters significantly decreased, particularly in shorter free storage periods, with improved performance across multiple clusters, demonstrating stronger stability. For instance, RCTY income for Cluster 0 and Cluster 2 increased noticeably during shorter free storage periods, while Cluster 1 exhibited higher stability. Overall, after clustering, the fluctuation of RCTY income was reduced, especially for longer free storage periods, with RCTY income becoming more stable within clusters. This suggests that clustering optimization helps improve the stability of RCTY income and reduces the negative impact of the free storage period on RCTY income.

The changes in carrier costs under different free storage periods before and after clustering indicate that clustering optimized the carrier cost performance across clusters, particularly reducing the volatility of carrier costs when the free storage period is shorter. Before clustering, the carrier costs across clusters exhibited greater fluctuations, especially in Cluster 0, Cluster 1, and Cluster 7, where there was a significant downward trend in carrier costs with longer free storage periods, showing considerable volatility. After clustering, the fluctuations in carrier costs across clusters were significantly reduced, with multiple clusters exhibiting more stable carrier costs, particularly when the free storage period was shorter. For instance, Cluster 0 and Cluster 2 showed an increase in carrier costs during shorter free storage periods, while Cluster 1 demonstrated higher stability, with much less volatility in carrier costs. Overall, clustering resulted in more stable carrier costs, especially when the free storage period was longer, with costs tending to stabilize across clusters.

Overall, clustering optimized CY income, particularly when the free storage period was shorter, with significant improvements in the performance of CY income across multiple clusters, showing higher stability. Compared to before clustering, the fluctuations in CY income were notably reduced, especially when the free storage period was longer, and after clustering, CY income tended to stabilize. This suggests that the clustering method effectively balances CY income across different clusters under varying free storage periods, reducing excessive fluctuations in CY income. This change may stem from optimized resource allocation within the clusters, enhancing the overall stability of CY income and strengthening the system's resilience to the impact of free storage period variations on CY income.

Analyzing

Figure 48,

Figure 49 and

Figure 50 before and after clustering for different free storage periods of import shipping containers, clustering optimized the CY income performance of each cluster, especially for shorter free storage periods, where the CY income of multiple clusters showed significant improvement. Before clustering, the CY income fluctuated greatly, particularly for longer free storage periods, where the CY income of multiple clusters showed a downward trend with high volatility. After clustering, the fluctuations in CY income were significantly reduced, especially for shorter free storage periods, where multiple clusters became more stable. For example, Cluster 0 and Cluster 1 showed a significant increase in CY income for shorter free storage periods, while Cluster 2 and Cluster 3 exhibited higher stability.

RCTY income saw significant improvement in multiple clusters, especially during shorter free storage periods. Before clustering, RCTY income fluctuated greatly, particularly during longer free storage periods, with a downward trend in several clusters. After clustering, the fluctuations in RCTY income were significantly reduced, especially during shorter free storage periods, where multiple clusters became more stable. For example, Cluster 0 and Cluster 1 saw a significant increase in RCTY income during shorter free storage periods, while Cluster 2 and Cluster 3 showed more stable income performance.

Additionally, before clustering, the carrier costs varied significantly across clusters, especially during longer free storage periods, where the carrier costs of multiple clusters showed different trends. After clustering, the carrier costs became smoother across clusters, with notable optimization, especially during shorter free storage periods. For example, the carrier costs of Cluster 0 and Cluster 1 increased during shorter free storage periods, while Cluster 2 and Cluster 3 maintained a more consistent downward trend.

These analyses provide important insights for port operators. First, shorter free storage periods significantly improved CY and RCTY income across multiple clusters, especially after clustering optimization, where income volatility was greatly reduced. Port operators can adjust free storage period strategies based on cluster characteristics to optimize storage management and improve income stability. Additionally, clustering optimized carrier costs, particularly during shorter free storage periods, where carrier costs across multiple clusters were effectively controlled. Based on these insights, port operators should consider differentiated pricing strategies, increasing charges for better-performing clusters, while optimizing free storage period settings for others. Furthermore, ports can achieve more efficient resource allocation through refined operational management, stabilizing income and enhancing overall operational efficiency and competitiveness.